A Comprehensive Guide to Computational Model Validation: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating computational models, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

A Comprehensive Guide to Computational Model Validation: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating computational models, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It bridges the gap between theoretical principles and practical application, covering core concepts like generalizability and overfitting, a suite of validation methodologies from goodness-of-fit to cross-validation, advanced optimization techniques including pruning and quantization, and rigorous model comparison and benchmarking. The guide emphasizes the critical role of robust validation in enhancing the credibility, translatability, and decision-making power of computational models in biomedical and clinical settings, aligning with initiatives like the NIH's push for human-based research technologies.

Understanding the Core Principles: What Makes a Computational Model Valid?

Technical Support & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My computational model performs well on training data but poorly on new, unseen validation data. What is happening and how can I fix it? This indicates a case of overfitting. Your model has learned the noise and specific patterns of the training data rather than the underlying generalizable relationships [1].

- Solution: Implement k-fold cross-validation during model training. This technique involves partitioning your data into 'k' subsets, iteratively training the model on k-1 subsets, and validating on the remaining subset. This provides a more robust estimate of model performance and reduces the risk of overfitting [1].

Q2: What is the critical quantitative difference between a validated model and a non-validated one for a research publication? The difference is quantified through specific performance metrics evaluated on a held-out test dataset. The following table summarizes the minimum thresholds often expected for a validated model in a peer-reviewed context [1]:

| Metric | Minimum Threshold for Validation | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | >95% | Proportion of total correct predictions. |

| Precision | >95% | Proportion of positive identifications that are actually correct. |

| Recall | >90% | Proportion of actual positives that were correctly identified. |

| F1 Score | >92% | Harmonic mean of precision and recall. |

| Mean Average Precision (mAP) | >0.9 | Average precision across all recall levels (for object detection). |

Q3: During cross-validation, my model's performance metrics vary widely between folds. What does this signify? High variance between folds suggests that your model is highly sensitive to the specific data it is trained on. This is often a result of having too little data or data that is not representative of the broader population. To address this, ensure your dataset is large and diverse, and consider using stratified cross-validation, which preserves the percentage of samples for each class in each fold, leading to more stable estimates [1].

Q4: How do I know if my validation results are statistically significant and not due to random chance? Statistical significance in model validation is typically established through null hypothesis testing. The process involves:

- Stating the Null Hypothesis (H₀): "The model's performance is no better than a random or baseline model."

- Calculating a p-value: Using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., paired t-test on cross-validation results, McNemar's test) to compute the probability of observing your model's performance if the null hypothesis were true.

- Setting a Significance Level (α): A common threshold is α = 0.05. If the p-value is less than α, you can reject the null hypothesis and conclude that your model's performance is statistically significant [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: High False Positive Rate During Model Validation

Problem: Your model is incorrectly identifying negative cases as positive (e.g., identifying healthy tissue as diseased), which can undermine trust in your results.

Investigation & Resolution Protocol:

- Confirm the Issue: Check the Confusion Matrix and calculate the False Positive Rate (FPR).

- FPR = False Positives / (False Positives + True Negatives)

- Diagnose the Cause:

- Imbalanced Dataset: If your negative class is underrepresented, the model may be biased. Check the distribution of your classes [1].

- Insufficient Feature Discriminability: The features you are using may not be powerful enough to distinguish between the positive and negative classes.

- Apply Corrective Measures:

- For Imbalanced Data: Use techniques like SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique) or adjust class weights in the model's loss function [1].

- Adjust Decision Threshold: By default, the classification threshold is often 0.5. You can raise this threshold to make the model more "conservative" in making a positive prediction, thereby reducing false positives. This will be reflected in a new Precision-Recall curve.

- Feature Re-engineering: Explore new, more discriminative features or perform feature selection to remove noisy, uninformative ones.

Issue: Model Performance Degrades Over Time After Deployment (Model Drift)

Problem: A model that was validated and performed well initially begins to show a drop in accuracy when applied to new data in a live environment.

Investigation & Resolution Protocol:

- Monitor Performance: Continuously monitor the model's key metrics (e.g., accuracy, F1 score) on incoming data and compare them to the validation baseline [1].

- Identify Drift Type:

- Concept Drift: The underlying statistical properties of the target variable you are trying to predict have changed over time.

- Data Drift: The distribution of the input data has changed since the model was trained.

- Implement a Solution:

- Establish a retraining schedule (e.g., quarterly, annually) where the model is retrained on newer, more representative data [1].

- Implement a trigger-based retraining system that automatically initiates when performance metrics fall below a pre-defined threshold.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: k-Fold Cross-Validation for Robust Performance Estimation

Objective: To obtain an unbiased and reliable estimate of a predictive model's performance by minimizing the variance associated with a single train-test split.

Methodology:

- Data Preparation: Randomly shuffle your dataset and partition it into

kmutually exclusive subsets (folds) of approximately equal size. A typical value forkis 5 or 10 [1]. - Iterative Training & Validation: For each of the

kiterations:- Designate one fold as the validation set.

- Use the remaining

k-1folds as the training set. - Train the model on the training set.

- Evaluate the model on the validation set and record all relevant performance metrics (e.g., accuracy, precision).

- Performance Aggregation: After all

kiterations, calculate the average and standard deviation of each performance metric across all folds. The average is your model's estimated performance.

Visualization of k-Fold Cross-Validation Workflow:

Protocol 2: Holdout Validation for Large-Scale Datasets

Objective: To efficiently validate a model using a single, held-out portion of the data, which is most practical when the dataset is very large.

Methodology:

- Data Splitting: Randomly split the entire dataset into three distinct subsets:

- Training Set (70%): Used to train the model.

- Validation Set (15%): Used to tune hyperparameters and make decisions about the model during development.

- Test Set (15%): Used only once to provide a final, unbiased evaluation of the fully-trained model [1].

- Stratification: For classification problems, ensure that the class distribution is approximately the same in all three splits. This is known as stratified sampling [1].

- Single Final Evaluation: The model is trained on the combined training and validation data after hyperparameter tuning. Its performance is then reported based on a single evaluation on the untouched test set.

Visualization of Holdout Validation Strategy:

Table 1: Model Performance Metrics and Their Interpretation in a Validation Context [1]

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | (TP+TN)/(TP+TN+FP+FN) | Overall correctness of the model. | Best for balanced class distributions. |

| Precision | TP/(TP+FP) | The accuracy of positive predictions. | Critical when the cost of false positives is high (e.g., drug safety). |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | TP/(TP+FN) | The ability to find all positive instances. | Critical when the cost of false negatives is high (e.g., disease screening). |

| F1 Score | 2(PrecisionRecall)/(Precision+Recall) | Harmonic mean of precision and recall. | Single metric to compare models when balance between Precision and Recall is needed. |

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Σ|yᵢ - ŷᵢ| / n | Average magnitude of errors in a set of predictions. | Regression tasks; interpretable in the units of the target variable. |

Table 2: Cross-Validation Methods Comparison [1]

| Method | Description | Pros | Cons | Recommended Scenario |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| k-Fold | Data partitioned into k folds; each fold used once as validation. | Reduces variance, robust performance estimate. | Computationally intensive for large k or complex models. | Standard for medium-sized datasets. |

| Stratified k-Fold | k-Fold preserving the percentage of samples for each class. | Better for imbalanced datasets. | Slightly more complex implementation. | Classification with class imbalance. |

| Holdout | Single split into training and test sets. | Simple and fast. | High variance; estimate depends on a single data split. | Very large datasets (n > 1,000,000). |

| Leave-One-Out (LOO) | k = n; each sample used once as a single test point. | Virtually unbiased; uses all data for training. | Extremely high computational cost; high variance in estimate. | Very small datasets (n < 100). |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Computational Model Validation

| Item | Function in Validation | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Public Dataset | Serves as a benchmark for comparing your model's performance against established state-of-the-art methods. | ImageNet (for image classification), MoleculeNet (for molecular property prediction). |

| Statistical Analysis Software/Library | Used to calculate performance metrics, perform significance testing, and generate visualizations. | Python (with scikit-learn, SciPy), R, MATLAB. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the computational power needed for extensive hyperparameter tuning and repeated cross-validation runs. | Cloud-based (AWS, GCP) or on-premise clusters with multiple GPUs. |

| Version Control System | Tracks changes to both code and data, ensuring the reproducibility of every validation experiment. | Git (with GitHub or GitLab), DVC (Data Version Control). |

| Automated Experiment Tracking Platform | Logs parameters, metrics, and results for each model run, facilitating comparison and analysis. | Weights & Biases (W&B), MLflow, TensorBoard. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My model achieves a high R² on training data but performs poorly on new, unseen validation data. Is this overfitting, and what can I do? Yes, this is a classic sign of overfitting, where your model has become too complex and has learned the noise in the training data rather than the underlying pattern. To address this:

- Simplify the Model: Reduce the number of parameters or features.

- Apply Regularization: Use techniques like L1 (Lasso) or L2 (Ridge) regression that penalize overly complex models.

- Increase Training Data: More data can help the model learn more generalizable patterns.

- Use Cross-Validation: Employ k-fold cross-validation during training to get a better estimate of how the model will perform on unseen data.

Q2: How can I systematically determine if my model is underfit, overfit, or well-balanced? A combination of quantitative metrics and visual inspection can diagnose model fit:

- Review Learning Curves: Plot the model's performance (e.g., error) on both the training and validation sets against the training set size or model complexity. An overfit model will show a large gap between training and validation performance. An underfit model will show both training and validation performance plateauing at an unsatisfying level.

- Compare Performance Metrics: A significant disparity between training accuracy (very high) and testing/validation accuracy (low) indicates overfitting. Consistently low performance on both sets suggests underfitting.

- Validate with a Hold-Out Set: Always evaluate the final model on a completely unseen test set that was not used during the training or validation phases.

Q3: What are the best practices for validating computational models, particularly in a research context like drug development? Robust validation is critical for ensuring model reliability and is a core component of Verification, Validation, and Uncertainty Quantification (VVUQ) [2].

- Verification: Ask, "Have I built the model right?" This process ensures the computational model correctly implements its intended mathematical model and algorithms.

- Validation: Ask, "Have I built the right model?" This process assesses the model's accuracy in representing the real-world system by comparing model predictions with independent experimental data [2].

- Uncertainty Quantification (UQ): Characterize and quantify the uncertainty in model predictions, which can arise from input parameters, experimental data, and the model form itself. This provides a confidence interval for your predictions.

Q4: Can machine learning models be effectively validated for predicting complex properties like ionic liquid viscosity? Yes. Recent research demonstrates that ML models like Random Forest (RF), Gradient Boosting (GB), and XGBoost (XGB) can achieve high predictive accuracy for ionic liquid viscosity when properly validated [3]. Key steps include:

- Using a large, high-quality dataset.

- Optimizing hyper-parameters with techniques like Glowworm Swarm Optimization (GSO).

- Rigorously evaluating performance using metrics like R², RMSE, and MAPE on a held-out test set.

- Reporting all performance metrics transparently, as seen in studies where RF achieved an R² of 0.9971 [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Validation Error (Potential Overfitting)

This guide follows a structured troubleshooting methodology to diagnose and resolve overfitting [4].

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Next Steps |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify the Problem | Compare training and validation error metrics (e.g., RMSE, MAE). A large gap confirms overfitting. | Problem Confirmed: Training error is significantly lower than validation error. |

| 2. Establish a Theory of Probable Cause | Theory: Model complexity is too high relative to the data. | Potential causes: Too many features, insufficient regularization, insufficient training data, too many model parameters (e.g., tree depth). |

| 3. Test the Theory | Simplify the model. Remove a subset of non-essential features or increase regularization strength. | Theory Correct if validation error decreases and gap closes. Theory Incorrect if error worsens; return to Step 2 and consider if data is noisy or poorly processed. |

| 4. Establish a Plan of Action | Plan to apply a combination of regularization (e.g., L2 norm), feature selection, and if possible, gather more training data. | A documented plan outlining the specific techniques and the order in which they will be applied. |

| 5. Implement the Solution | Re-train the model with the new parameters and/or reduced feature set. | A new, simplified model is generated. |

| 6. Verify System Functionality | Evaluate the new model on a fresh test set. Check that the performance gap has closed and overall predictive power is maintained. | The model now performs consistently on both training and unseen test data. |

| 7. Document Findings | Record the original issue, the changes made, and the resulting performance metrics. | Creates a knowledge base for troubleshooting future models and ensures reproducibility [4]. |

Problem: Consistently High Training and Validation Error (Potential Underfitting)

| Step | Action | Expected Outcome & Next Steps |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Identify the Problem | Observe that both training and validation errors are high and often very similar. | Problem Confirmed: The model is not capturing the underlying data structure. |

| 2. Establish a Theory of Probable Cause | Theory: Model is too simple, or features are not informative enough. | Potential causes: Model is not complex enough (e.g., linear model for non-linear process), key predictive features are missing, model training was stopped too early. |

| 3. Test the Theory | Increase model complexity. Add polynomial features, decrease regularization, or use a more powerful model (e.g., switch to a non-linear ML model). | Theory Correct if training error decreases significantly. Theory Incorrect if error does not change; return to Step 2 and investigate feature engineering. |

| 4. Establish a Plan of Action | Plan to systematically increase model capacity and engineer more relevant features. | A documented plan for iterative model and feature improvement. |

| 5. Implement the Solution | Re-train the model with new features and/or increased complexity. | A new, more powerful model is generated. |

| 6. Verify System Functionality | Evaluate the new model. Training error should have decreased, and validation error should follow, improving overall accuracy. | The model now captures the data's trends more effectively. |

| 7. Document Findings | Document the changes in model complexity/features and the resulting impact on performance. | Guides future model development to avoid underfitting. |

Model Performance Data

The following table summarizes quantitative data from a study predicting ionic liquid viscosity, illustrating the performance of different optimized models [3].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Machine Learning Models for Viscosity Prediction

| Model | R² Score | RMSE | MAPE | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forest (RF) | 0.9971 | Very Low | Very Low | Ensemble method, robust to overfitting, high accuracy [3]. |

| Gradient Boosting (GB) | 0.9916 | Low | Low | Builds models sequentially to correct errors. |

| XGBoost (XGB) | 0.9911 | Low | Low | Optimized version of GB, fast and efficient. |

Experimental Protocol: Hyper-parameter Optimization with Glowworm Swarm Optimization (GSO)

Objective: To fine-tune the hyper-parameters of a machine learning model (e.g., RF, GB, XGB) to maximize predictive performance and mitigate overfitting.

Methodology:

- Define the Search Space: Identify the key hyper-parameters to optimize (e.g., number of trees, maximum depth, learning rate) and their plausible value ranges.

- Initialize the Swarm: Randomly initialize a population of "glowworms," where each glowworm represents a unique set of hyper-parameters.

- Evaluate Fitness: For each glowworm (hyper-parameter set), train the model and evaluate its performance using a metric like R² via 3-fold cross-validation [3]. This fitness score represents the glowworm's "bioluminescence."

- Update Positions: Glowworms move within the search space based on attraction to brighter neighbors (better solutions) and repulsion to avoid overcrowding, exploring new regions [3].

- Iterate: Repeat the fitness evaluation and position update steps for a set number of iterations or until convergence.

- Final Solution: Select the hyper-parameters of the brightest glowworm as the optimal configuration for the model.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Computational Modeling Research

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| High-Quality Dataset | The foundation of any model; used for training, validation, and testing. Must be accurate, complete, and representative. |

| Machine Learning Framework (e.g., Scikit-learn, TensorFlow) | Software libraries that provide the algorithms and tools to build, train, and evaluate computational models. |

| Computational Resources (CPU/GPU) | Hardware for performing the often intensive calculations required for model training and hyper-parameter optimization. |

| Optimization Algorithm (e.g., GSO, Grid Search) | Tools to automatically and efficiently find the best model hyper-parameters, improving performance and generalizability [3]. |

| Validation Dataset | An independent set of data not used during training, critical for assessing model generalizability and detecting overfitting. |

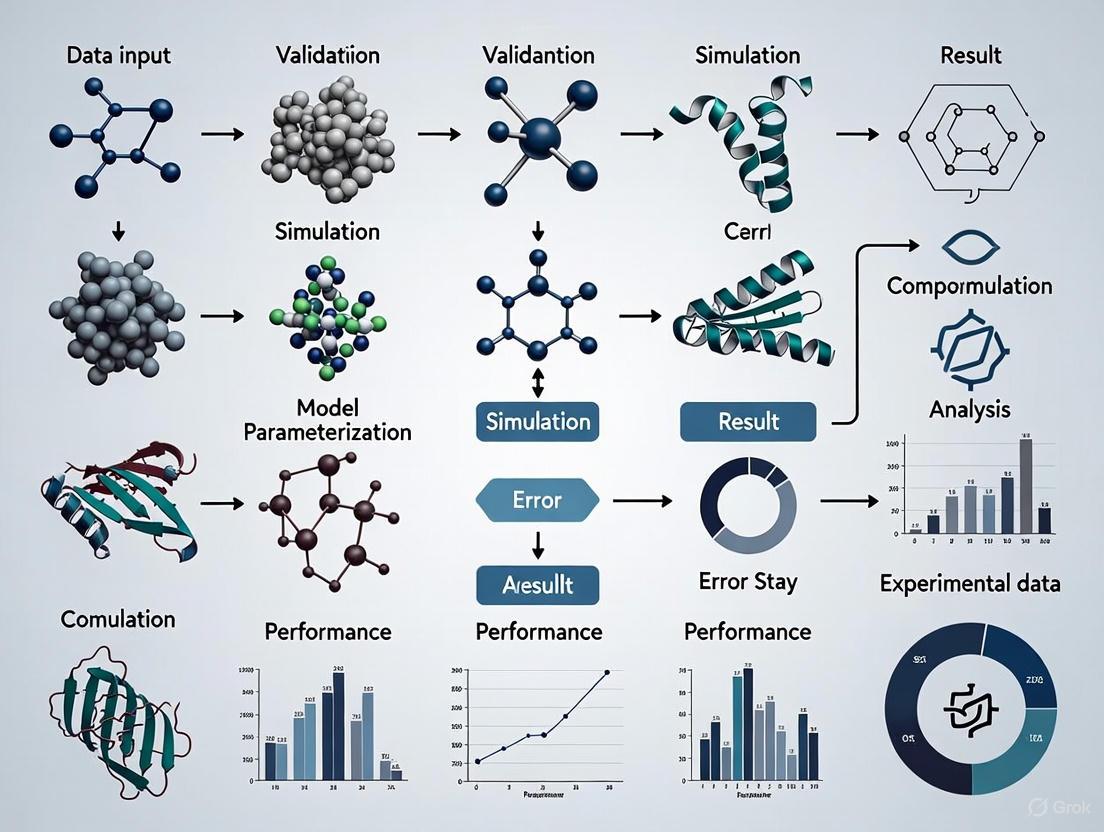

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Model Fit Diagnosis and Remediation

Model Validation and Optimization Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the core objective of model evaluation, and why are these three criteria—Goodness-of-Fit, Complexity, and Generalizability—important? The core objective is to select a model that not only describes your current data but also reliably predicts future, unseen data [5]. These three criteria are interconnected:

- Goodness-of-Fit (GOF) measures how well your model replicates the observed data [6] [5].

- Complexity quantifies the model's flexibility. Overly complex models can fit noise rather than the underlying pattern [5] [7].

- Generalizability is the ultimate goal: it assesses how well the model's predictions will hold for new data samples from the same process. A good model balances fit and complexity to achieve high generalizability [5].

2. My model has an excellent fit on the training data, but performs poorly on new data. What is happening and how can I fix it? This is a classic sign of overfitting, where your model has learned the noise in the training data instead of the underlying signal [7]. To address this:

- Reduce Model Complexity: Simplify your model by reducing the number of parameters or features [7].

- Use Regularization: Implement techniques like Lasso (L1) or Ridge (L2) regression, which add a penalty to the loss function based on model complexity to prevent overfitting [7].

- Apply Cross-Validation: Use methods like k-fold cross-validation to get a more robust estimate of your model's performance on unseen data [8].

3. How do I choose the right metric for my model? The choice of metric depends on your model's task (regression vs. classification) and the specific costs of different types of errors in your application [9] [10].

For Regression Models (predicting continuous values):

For Classification Models (predicting categories):

- Use Accuracy only for balanced datasets where the cost of different errors is similar [9] [10].

- Use Precision when the cost of false positives is high (e.g., in spam detection) [9] [10].

- Use Recall when the cost of false negatives is high (e.g., in disease screening) [9] [10].

- Use the F1-Score to balance Precision and Recall [11] [10].

- Use the AUC-ROC curve to evaluate the model's performance across all classification thresholds [9] [11].

4. What is the bias-variance tradeoff and how does it relate to model evaluation? The bias-variance tradeoff is a fundamental framework for understanding model performance [7].

- Bias is the error from erroneous assumptions in the model. High bias can cause underfitting (the model is too simple to capture patterns) [7].

- Variance is the error from sensitivity to small fluctuations in the training set. High variance can cause overfitting (the model is too complex and fits the noise) [7]. The goal is to find the optimal model complexity that minimizes total error by balancing bias and variance [7].

5. What are AIC and BIC, and how should I use them for model selection? Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) are metrics that balance goodness-of-fit with model complexity to help select the model that generalizes best [6] [5].

- AIC is defined as (2k - 2\ln(L)), where (k) is the number of parameters and (L) is the model's likelihood. It is best for predicting future data [6].

- BIC is defined as (k \ln(n) - 2\ln(L)), where (n) is the number of data points. It includes a stronger penalty for complexity and is better for identifying the true model [6]. In both cases, when comparing multiple models, the one with the lowest AIC or BIC is preferred [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model is Overfitting

- Symptoms: Excellent performance (e.g., high accuracy, low error) on training data, but poor performance on validation or test data [7].

- Diagnosis:

- Plot learning curves (training and validation error vs. model complexity or training iterations).

- Compare the model's performance on training vs. validation sets using metrics like AUC-ROC or F1-score [11].

- Solutions:

- Gather More Training Data: This helps the model learn the true data distribution rather than noise.

- Apply Regularization:

- Simplify the Model: Reduce the number of features (feature selection) or, for neural networks, reduce the number of layers or units [7].

- Use Early Stopping: Halt the training process when performance on a validation set starts to degrade.

- Implement Cross-Validation: Use k-fold cross-validation for a more reliable estimate of generalizability and to tune hyperparameters without overfitting the test set [8].

Problem: Model is Underfitting

- Symptoms: Poor performance on both training and validation data [7].

- Diagnosis:

- The model is too simple to capture the underlying trends (high bias).

- Learning curves show high training error.

- Solutions:

- Increase Model Complexity: Add more relevant features, or for neural networks, increase the number of layers or units [7].

- Reduce Regularization: Lower the strength of L1 or L2 regularization penalties [7].

- Train for Longer: For iterative models like gradient boosting or neural networks, increase the number of training epochs.

- Engineer More Informative Features: Create new features that better capture the patterns in the data.

Problem: Unclear Which Model is Best

- Symptoms: Multiple models have similar performance metrics, making it difficult to choose one for final deployment.

- Diagnosis: Relying on a single metric or not properly accounting for model complexity.

- Solutions:

- Use Information Criteria: Calculate AIC or BIC for each model and select the one with the lowest value [6] [5].

- Employ Cross-Validation: Compare models based on their cross-validated performance (e.g., mean cross-validation score) rather than a single train-test split [8].

- Prioritize Generalizability: Designate a hold-out test set that is only used once for a final, unbiased evaluation of the selected model's performance [8].

- Consider Business Context: Choose the model based on the metric that matters most for your specific application (e.g., maximize recall for a medical test) [10].

Table 1: Common Goodness-of-Fit and Performance Metrics

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| R-squared (R²) | (1 - \frac{RSS}{TSS}) | Proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is predictable from the independent variables. Closer to 1 is better [6] [9]. | Regression models, assessing explanatory power. |

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | (\frac{1}{N}\sum|y-\hat{y}|) | Average magnitude of errors. Easy to interpret [9]. | Regression, when error magnitude is important. |

| Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | (\sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum(y-\hat{y})^2}) | Average magnitude of errors, but penalizes larger errors more than MAE [9]. | Regression, when large errors are particularly undesirable. |

| Accuracy | (\frac{TP+TN}{TP+TN+FP+FN}) | Proportion of total correct predictions [9] [10]. | Classification, when classes are balanced. |

| Precision | (\frac{TP}{TP+FP}) | Proportion of positive predictions that are actually correct [9] [10]. | When the cost of false positives is high. |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | (\frac{TP}{TP+FN}) | Proportion of actual positives that are correctly identified [9] [10]. | When the cost of false negatives is high (e.g., disease detection). |

| F1-Score | (2 \times \frac{Precision \times Recall}{Precision + Recall}) | Harmonic mean of precision and recall. Balances the two [11] [10]. | Imbalanced datasets, or when a single score balancing FP and FN is needed. |

| Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | (2k - 2\ln(L)) | Balances model fit and complexity. Lower values indicate a better trade-off [6] [5]. | Model selection with a focus on predictive accuracy. |

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | (k \ln(n) - 2\ln(L)) | Balances model fit and complexity with a stronger penalty for parameters than AIC. Lower is better [6] [5]. | Model selection with a focus on identifying the true model. |

Table 2: Model Selection Checklist Based on Model Performance

| Symptom | High Training Error, High Validation Error | Low Training Error, High Validation Error | Low Training Error, Low Validation Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Underfitting (High Bias) [7] | Overfitting (High Variance) [7] | Good Fit |

| Next Actions | • Increase model complexity• Add more features• Reduce regularization | • Gather more training data• Increase regularization• Reduce model complexity• Apply feature selection | • Proceed to final evaluation on a hold-out test set |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Protocol 1: k-Fold Cross-Validation for Robust Performance Estimation This protocol provides a robust estimate of model generalizability by repeatedly splitting the data [8].

- Data Preparation: Randomly shuffle the dataset and partition it into k equally sized folds (common choices are k=5 or k=10).

- Iterative Training and Validation: For each unique fold:

- Designate the current fold as the validation set.

- Designate the remaining k-1 folds as the training set.

- Train the model on the training set.

- Evaluate the model on the validation set and record the chosen performance metric (e.g., accuracy, F1-score).

- Result Aggregation: Calculate the mean and standard deviation of the k recorded performance metrics. The mean represents the expected model performance.

Protocol 2: Train-Validation-Test Split for Model Development and Assessment This protocol uses separate data splits for tuning model parameters and for a final, unbiased assessment [8].

- Initial Split: Split the available data into a temporary set (e.g., 80%) and a hold-out test set (e.g., 20%).

- Secondary Split: Split the temporary set into a training set (e.g., 70-80% of temporary set) and a validation set (e.g., 20-30% of temporary set).

- Model Tuning: Train multiple model configurations (e.g., with different hyperparameters) on the training set and evaluate their performance on the validation set.

- Final Assessment: Select the best-performing model configuration based on the validation set results. Retrain this model on the entire temporary set (training + validation) and perform a single, final evaluation on the hold-out test set to estimate its real-world performance.

Conceptual Diagrams

Diagram 1: Relationship between core evaluation criteria and model selection. AIC/BIC formalizes the trade-off between Goodness-of-Fit and Complexity to achieve the goal of Generalizability.

Diagram 2: A diagnostic and refinement workflow for addressing overfitting and underfitting during model development.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Model Evaluation

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Evaluation | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-Validation Engine | Provides robust estimates of model generalizability by systematically partitioning data into training and validation sets [8]. | Using 10-fold cross-validation to reliably compare the mean AUC of three different classifier algorithms. |

| Regularization Methods (L1/L2) | Prevents overfitting by adding a complexity penalty to the model's loss function, discouraging over-reliance on any single feature [7]. | Applying L1 (Lasso) regularization to a logistic regression model to perform feature selection and reduce variance. |

| Information Criteria (AIC/BIC) | Provides a quantitative measure for model selection that balances goodness-of-fit against model complexity [6] [5]. | Selecting the best-performing protein folding model from two candidates by choosing the one with the lower AIC value [5]. |

| Performance Metrics (Precision, Recall, F1, etc.) | Quantifies different aspects of model performance based on the confusion matrix and error types [9] [11] [10]. | Optimizing a medical diagnostic model for high Recall to ensure most true cases of a disease are captured, even at the cost of more false positives. |

| Hold-Out Test Set | Serves as a final, unbiased dataset to assess the model's real-world performance after all model development and tuning is complete [8]. | Reporting the final accuracy of a validated model on a completely unseen test set that was locked away during all previous development stages. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Overfitting

This guide helps researchers and scientists in computational modeling and drug development diagnose and correct overfitting in their machine learning models.

FAQ: How can I tell if my model is overfitting?

Answer: Your model is likely overfitting if you observe a significant performance gap between training and validation data. Key indicators include:

- High accuracy on training data but poor accuracy on test or validation data [12].

- The model learns the noise and random fluctuations in the training data instead of the underlying pattern [12].

FAQ: What is the simplest method to detect overfitting?

Answer: The most straightforward method is Hold-Out Validation [13] [12].

- Methodology: Split your dataset into two parts: a training set (e.g., 80%) and a testing set (e.g., 20%) [13].

- Detection: Train your model on the training set and evaluate its performance on the unseen test set. A high error rate on the test set indicates overfitting [12].

FAQ: My dataset is small. How can I reliably test for overfitting?

Answer: For limited data, use K-Fold Cross-Validation [12].

- Methodology: Split your dataset into K equally sized folds (e.g., K=5 or 10). In each iteration, use K-1 folds for training and the remaining fold for validation. Repeat this process K times, using each fold as the validation set once [12].

- Output: The final model performance is the average of the performance across all K iterations, providing a more robust estimate of how the model generalizes [12].

Key Experiments and Validation Protocols

Experiment: Detecting Overfitting via Performance Discrepancy

This experiment aims to identify overfitting by comparing model performance on training versus validation data.

- Objective: To quantify the generalization error of a computational model.

- Protocol:

- Randomly split the dataset into training (80%) and testing (20%) sets [13].

- Train the model on the training set.

- Calculate key performance metrics (e.g., Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-Score) on both the training set and the test set [11].

- A significant drop in performance on the test set is a clear indicator of overfitting [12].

The logical workflow for this validation method is outlined below.

Experiment: Implementing K-Fold Cross-Validation

This protocol provides a robust validation technique for smaller datasets, reducing the variance of a single train-test split.

- Objective: To obtain a reliable estimate of model performance and generalization error.

- Protocol:

- Randomly shuffle the dataset and split it into K consecutive folds of roughly equal size [12].

- For each fold

i(whereiranges from 1 to K):- Use fold

ias the validation set. - Use the remaining K-1 folds as the training set.

- Train the model and evaluate it on the validation set.

- Record the performance score for fold

i.

- Use fold

- Calculate the final performance metric by averaging the scores from the K folds.

The following diagram illustrates the process for 5-fold cross-validation.

Model Evaluation Metrics for Validation

The following table summarizes key quantitative metrics used to evaluate model performance and detect overfitting during validation experiments [11].

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | (TP + TN) / (TP + TN + FP + FN) | Overall correctness of the model. | General performance assessment. |

| Precision | TP / (TP + FP) | Proportion of correct positive predictions. | When the cost of false positives is high (e.g., drug safety). |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | TP / (TP + FN) | Proportion of actual positives correctly identified. | When missing a positive is dangerous (e.g., disease diagnosis). |

| F1 Score | 2 * (Precision * Recall) / (Precision + Recall) | Harmonic mean of precision and recall. | Balanced view when class distribution is uneven. |

| AUC-ROC | Area under the ROC curve | Measures the model's ability to distinguish between classes. | Overall performance across all classification thresholds. |

Abbreviations: TP = True Positive, TN = True Negative, FP = False Positive, FN = False Negative [11].

Solutions and Preventative Measures

The table below details common techniques to prevent and mitigate overfitting, aligning with the experimental protocols.

| Technique | Methodology | Primary Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Data Augmentation [13] [12] | Artificially increase training data size using transformations (e.g., image flipping, rotation). | Increases data diversity, teaches the model to ignore noise. |

| L1 / L2 Regularization [13] | Add a penalty term to the cost function to constrain model complexity. | Shrinks coefficient values, prevents the model from over-reacting to noise. |

| Dropout [13] | Randomly ignore a subset of network units during training. | Reduces interdependent learning among neurons. |

| Early Stopping [13] [12] | Monitor validation loss and stop training when it begins to degrade. | Prevents the model from learning noise in the training data. |

| Simplify Model [13] [12] | Reduce the number of layers or neurons in the network. | Decreases model capacity, forcing it to learn dominant patterns. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential computational "reagents" and tools for robust model validation.

| Item | Function | Relevance to Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Training/Test Splits | Provides a held-out dataset to simulate unseen data and test generalization [13] [12]. | Fundamental for detecting overfitting. |

| K-Fold Cross-Validation | A resampling procedure used to evaluate a model on limited data [12]. | Reduces variability in performance estimation. |

| Confusion Matrix | A table used to describe the performance of a classification model [11]. | Allows calculation of precision, recall, F1-score. |

| ROC Curve | A plot that illustrates the diagnostic ability of a binary classifier system [11]. | Visualizes the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. |

| SHAP/LIME (XAI) | Tools for Explainable AI that help interpret model predictions [14]. | Audits model logic for spurious correlations and bias. |

For researchers in computational science and drug development, a model's performance metrics are only part of the story. Explanatory adequacy and interpretability are critical components of model validation, ensuring that a model's decision-making process is transparent, understandable, and scientifically plausible. Moving beyond a "black box" approach builds trust in your model's outputs, facilitates peer review, and is increasingly required by health technology assessment agencies and regulatory bodies for artificial intelligence-based medical devices [15]. This technical support center provides practical guidance for integrating these principles into your research workflow.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the practical difference between interpretability and explainability in model validation?

- Interpretability is the ability to understand the model's mechanics and the cause-and-effect relationships within it. It refers to how well a human can predict what a model will do [15]. Explainability is the ability to explain the reasons for a specific model decision or prediction in human-understandable terms [15]. In practice, you should aim for interpretability to understand your model's overall logic and use explainability techniques to justify individual predictions in your research papers.

2. Our deep learning model has high accuracy, but reviewers demand an explanation for its predictions. What can we do?

- This is a common challenge. High performance does not equate to understanding. To address this, employ post-hoc explanation techniques (methods applied after the model has made a prediction). These can include:

- Feature Importance: Identifying which input variables most influenced a specific prediction.

- Saliency Maps: For image-based models, generating heatmaps that highlight the pixels most critical to the classification.

- Surrogate Models: Training a simple, interpretable model (like a decision tree) to approximate the predictions of your complex model and explain its behavior.

3. How can we assess the utility of an interpretable model for a specific clinical or research task?

- Model utility goes beyond standard performance metrics. Before development, establish a framework to answer key questions [16]:

- What actionable insight will the model provide?

- Is there a feasible intervention or follow-up action based on the prediction?

- What are the costs and constraints of that action? A model predicting a high risk of a condition is only useful if you have the capacity and means to act on that prediction [16].

4. We are concerned about model generalizability. How does interpretability help?

- Interpretable models can reveal model instability and data bias. If a model relies on a spurious correlation in your training data (e.g., associating a specific hospital's watermark with a disease in X-rays), explanation techniques can surface this flaw. This allows you to fix the dataset and build a more robust model that generalizes to data from new hospitals or populations [16].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Unexplained Model Failure After Deployment

Your model validated perfectly on internal test data but is producing erratic and incorrect predictions in a new clinical setting.

| Troubleshooting Step | Description & Action |

|---|---|

| 1. Understand the Problem | Gather information and context. What does the new data look like? How does the new environment differ from the development one? Reproduce the issue with a small sample of the new data [17]. |

| 2. Isolate the Issue | Simplify the problem. Compare the input data distributions (feature means, variances) between your original validation set and the new data. This helps isolate the issue as a data drift or concept drift problem [17]. |

| 3. Find a Fix or Workaround | Short-term: Use interpretability tools to see if the model is using nonsensical features in the new environment. This can provide an immediate explanation to stakeholders [15].Long-term: Implement continuous monitoring for data drift and plan for model retraining with data from the new environment [16]. |

Problem: Stakeholder Resistance to Adopting a "Black Box" Model

Clinicians or regulatory bodies are hesitant to trust your model's predictions because they cannot understand its logic.

| Troubleshooting Step | Description & Action |

|---|---|

| 1. Understand the Problem | Empathize with the stakeholder. Their resistance is often rooted in a valid need for accountability and safety, especially in drug development [17]. Identify their specific concerns (e.g., "What if it's wrong?"). |

| 2. Isolate the Issue | Determine the core of their hesitation. Is it a lack of trust in the model's accuracy, or a need to reconcile the output with their own expertise? |

| 3. Find a Fix or Workaround | Advocate for the model: Position yourself alongside the stakeholder [17]. Use explanation techniques like Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME) to generate case-specific reasons for predictions, making the model a "consultant" rather than an oracle.Document and educate: Create clear documentation on the model's intended use, limitations, and how its explanations should be interpreted [18]. |

Quantitative Data on Model Assessment Criteria

The following table summarizes the three main assessment criteria for AI-based models, particularly in a healthcare context, as highlighted by health technology assessment guidelines [15].

Table 1: Key Assessment Criteria for Computational Models

| Criterion | Description | Role in Validation & Explanatory Adequacy |

|---|---|---|

| Performance | Quantitative measures of the model's predictive accuracy (e.g., AUC, F1-score, sensitivity, specificity). | The foundational asset. It answers "Does the model work?" but not "How does it work?" Must be evaluated based on model structure and data availability [15]. |

| Interpretability | The degree to which a human can understand the model's internal mechanics and predict its outcome. | Reinforces confidence. It allows researchers to validate that the model's decision logic aligns with established scientific knowledge and is not based on artifactual correlations [15]. |

| Explainability | The ability to provide understandable reasons for a model's specific decisions or predictions to a human. | Enables accountability. It helps hold stakeholders accountable for decisions made by the model and allows for debugging and improvement of the model itself [15]. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Model Explanations

This protocol provides a methodology for testing whether your model's explanations are faithful to its actual reasoning process.

Objective: To empirically validate that the features highlighted by a post-hoc explanation method are genuinely important to the model's prediction.

Background: Simply trusting an explanation method's output is insufficient. This protocol tests for explanation faithfulness by systematically perturbing the model's inputs and observing the effect on its output [16].

Workflow Diagram

Materials and Reagents:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Explanation Validation

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Trained Model | The computational model (e.g., a neural network) whose explanations are being validated. |

| Validation Dataset | A held-out set of data, not used in training, for unbiased testing of the model and its explanations. |

| Explanation Framework | Software library (e.g., SHAP, Captum, LIME) used to generate post-hoc explanations for the model's predictions. |

| Perturbation Method | A defined algorithm for modifying input data (e.g., masking image regions, shuffling feature values) to test feature importance. |

Methodology:

- Sample Selection: Select a representative input sample from your validation dataset.

- Baseline Prediction: Run the sample through your model and record both the output prediction and its confidence score.

- Generate Explanation: Use your chosen explanation framework (e.g., LIME) to generate a feature attribution list for this specific prediction. Identify the top K most important features.

- Perturbation: Systematically perturb or remove the top K features identified in the explanation. For an image, this could mean blurring the highlighted region; for tabular data, it could mean replacing the feature values with the mean.

- Secondary Prediction: Pass the perturbed sample through the model and record the new prediction and confidence score.

- Analysis: Compare the new confidence score with the baseline. A significant drop in confidence indicates that the perturbed features were truly important, providing evidence that the explanation is faithful. A minimal change suggests the explanation may not be capturing the model's true reasoning.

A Framework for Developing Interpretable Models

The following diagram outlines a decision process for incorporating explanatory adequacy from the outset of a modeling project, helping to choose the right model type based on data availability and existing knowledge [16].

Model Development Decision Framework

A Practical Toolkit: Essential Validation Methods and Techniques

For researchers developing computational models, a rigorous data splitting strategy is not merely a preliminary step but the foundation of a statistically sound and reproducible experiment. Properly partitioning your data into training, validation, and test sets is crucial for obtaining an unbiased estimate of your model's generalization performance—its ability to make accurate predictions on new, unseen data [19] [20]. This practice directly prevents overfitting, a common pitfall where a model performs well on its training data but fails to generalize [21]. This guide provides troubleshooting advice and detailed protocols to help you correctly implement these strategies within your research workflow.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: My model performs well during training but poorly on new data. What is the cause?

This is a classic sign of overfitting [21] [22]. Your model has likely memorized noise and specific patterns in the training data instead of learning generalizable rules.

Solution:

- Reassess Your Data Split: Ensure you have a dedicated validation set for hyperparameter tuning and a completely untouched test set for final evaluation [20]. Never use your test set for model tuning, as this leads to information leakage and an overly optimistic performance estimate [21].

- Implement Cross-Validation: For small to medium-sized datasets, use k-fold cross-validation instead of a single validation set. This provides a more robust performance estimate by training and validating the model on different data subsets [23] [24].

- Apply Regularization: Techniques like L1 (Lasso) or L2 (Ridge) regularization can penalize overly complex models and help prevent overfitting.

FAQ 2: How should I split my data if my dataset is very small?

With limited data, a single train-test split can be unreliable due to high variance in the performance estimate [25].

Solution:

- Use k-Fold Cross-Validation: This strategy makes efficient use of limited data. A common choice is 10-fold cross-validation [23]. For very small datasets (e.g., less than 100 samples), you might consider Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation (LOOCV), though it is computationally expensive [23].

- Consider Monte Carlo Cross-Validation: This involves repeatedly performing random splits of the data into training and validation sets, which can provide a more stable estimate [24].

FAQ 3: I am working with time-series data. Can I split my data randomly?

No. Random splitting destroys the temporal order of time-series data, leading to data leakage and grossly inflated performance metrics [26] [25]. For instance, if data from the future is used to predict the past, the model will appear accurate but fail in production.

Solution:

- Use a Chronological Split: Always train your model on earlier data and validate/test on later data [25].

- Training Set: The earliest period of your data.

- Validation Set: The subsequent period (for tuning).

- Test Set: The most recent period (for final evaluation).

- Employ Time Series Split Cross-Validation: Techniques like

TimeSeriesSplitin scikit-learn create multiple folds by expanding the training window while keeping the test set strictly chronologically ahead of the training data [25].

FAQ 4: What should I do if my dataset has a severe class imbalance?

Random splitting on an imbalanced dataset can result in training or validation splits that have very few or even zero examples of the minority class, making it impossible for the model to learn them [22].

Solution:

- Use Stratified Splitting: Ensure that the relative proportion of each class is preserved in the training, validation, and test splits [23] [22]. Most machine learning libraries, like scikit-learn, offer

StratifiedKFoldfor this purpose.

The table below summarizes the core data splitting methods, their ideal use cases, and key considerations for researchers.

| Strategy | Description | Best For | Key Advantages | Key Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hold-Out | Single split into training and test sets (e.g., 70-30%) [23]. | Very large datasets, quick preliminary model evaluation [23] [27]. | Simple and fast to compute [23]. | Performance estimate can have high variance; only a portion of data is used for training [23]. |

| Train-Validation-Test | Two splits create three sets: training, validation (for tuning), and a final test set (for evaluation) [19] [22]. | Model hyperparameter tuning and selection while providing a final unbiased test [19] [20]. | Prevents overfitting to the test set by using a separate validation set for tuning [19]. | Results can be sensitive to a particular random split; reduces data available for training [21]. |

| k-Fold Cross-Validation | Data is divided into k folds. Model is trained on k-1 folds and validated on the remaining fold, repeated k times [23] [21]. | Small to medium-sized datasets for obtaining a robust performance estimate [23] [25]. | Lower bias; more reliable performance estimate; all data is used for both training and validation [23]. | Computationally expensive as the model is trained k times [23]. |

| Stratified k-Fold | A variation of k-fold that preserves the class distribution in each fold [23]. | Imbalanced datasets for classification tasks [23] [22]. | Ensures each fold is representative of the overall class balance, leading to more reliable metrics. | Slightly more complex than standard k-fold. |

| Leave-One-Out (LOOCV) | A special case of k-fold where k equals the number of data points. Each sample is used once as a test set [23]. | Very small datasets where maximizing training data is critical [23]. | Very low bias; uses almost all data for training. | Extremely computationally expensive; high variance in the estimate [23]. |

Experimental Protocols for Data Splitting

Protocol 1: Standard Train-Validation-Test Split

This is a foundational protocol for model development.

- Partition the Data: Randomly shuffle the dataset and split it into three parts:

- Train Model: Train your model on the training set.

- Tune and Validate: Evaluate the model on the validation set and adjust hyperparameters iteratively. The best-performing model on the validation set is selected.

- Final Evaluation: Train the final model on the combined training and validation data to maximize learning. Then, evaluate it once on the untouched test set to report the final performance [20].

Python Implementation:

Protocol 2: k-Fold Cross-Validation for Model Evaluation

Use this protocol for a more robust assessment of your model's performance.

- Hold Out Test Set: First, set aside a test set (e.g., 20%) for final evaluation. Do not use this for any tuning [20].

- Configure k-Fold: Choose a value for k (typically 5 or 10) [23]. Split the remaining data (training + validation portion) into k equal-sized folds.

- Iterative Training: For each of the k iterations:

- Use k-1 folds as the training set.

- Use the remaining 1 fold as the validation set.

- Train the model and evaluate its performance.

- Calculate Performance: Average the performance metrics from the k iterations to get a robust estimate of the model's performance [23] [21].

- Final Model: After identifying the best model and hyperparameters through cross-validation, retrain the model on the entire dataset (excluding the held-out test set) and perform a final evaluation on the test set [20].

Python Implementation:

Data Splitting Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow for selecting and applying the appropriate data splitting strategy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below details key computational tools and concepts essential for implementing robust data splitting strategies.

| Tool / Concept | Function / Purpose | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

train_test_split |

A function in scikit-learn to randomly split datasets into training and testing subsets [21]. | Found in sklearn.model_selection. Critical for implementing the hold-out method. |

cross_val_score |

A function that automates the process of performing k-fold cross-validation and returns scores for each fold [21]. | Found in sklearn.model_selection. Simplifies robust model evaluation. |

KFold & StratifiedKFold |

Classes used to split data into k consecutive folds. StratifiedKFold preserves the percentage of samples for each class [23] [21]. |

Essential for implementing cross-validation protocols, especially with imbalanced data. |

TimeSeriesSplit |

A cross-validation iterator that preserves the temporal order of data, ensuring the test set is always after the training set [25]. | Found in sklearn.model_selection. Mandatory for time-series forecasting tasks. |

| Pipeline | A scikit-learn object used to chain together data preprocessing steps and a final estimator [21]. | Prevents data leakage by ensuring preprocessing (like scaling) is fit only on the training fold during cross-validation. |

| Random State / Seed | An integer parameter used to control the randomness of the shuffling and splitting process. | Using a fixed seed (e.g., random_state=42) ensures that your experiments are reproducible [25]. |

For researchers in computational models and drug development, validating a model's performance is a critical step in ensuring its reliability and predictive power. This guide focuses on three fundamental goodness-of-fit measures: Sum of Squared Errors (SSE), Percent Variance Accounted For (often expressed as R-squared), and the Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) method. These metrics help quantify how well your model captures the underlying patterns in your data, which is essential for making credible scientific claims and decisions [28] [29].

This resource provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to address specific issues you might encounter when applying these measures in your research.

Conceptual Foundations and Formulas

Before troubleshooting, it is crucial to understand what each measure represents and how it is calculated.

Sum of Squared Errors (SSE): Also known as the Residual Sum of Squares (RSS), the SSE measures the total deviation of the observed values from the values predicted by your model. It represents the unexplained variability by the model. A smaller SSE indicates a closer fit to the data [30] [31].

- Formula:

SSE = Σ(y_i - ŷ_i)²Wherey_iis the observed value andŷ_iis the predicted value [30].

- Formula:

Total Sum of Squares (SST): This measures the total variability in your observed data relative to its mean. It is the baseline against which the model's performance is judged [30] [32].

- Formula:

SST = Σ(y_i - ȳ)²Whereȳis the mean of the observed data [30].

- Formula:

Percent Variance Accounted For (R-squared): This statistic, also known as the coefficient of determination, measures the proportion of the total variance in the dependent variable that is explained by your model. It is derived from the SSE and SST [28] [31].

Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE): MLE is a method for estimating the parameters of a statistical model. It works by finding the parameter values that maximize the likelihood function, which is the probability of observing the data given the parameters. The point where this probability is highest is called the maximum likelihood estimate [33] [34].

The relationship between these components is foundational: SST = SSR + SSE, where SSR (Sum of Squares due to Regression) is the explained variability [30]. This relationship is visually summarized in the diagram below.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. My SSE value is very large. What does this mean, and how can I improve my model? A large SSE indicates that the overall difference between your observed data and your model's predictions is substantial. This is a sign of poor model fit. To address this:

- Check for Outliers: Investigate your data for anomalies or errors that could be skewing the results.

- Review Model Specification: Ensure you are using the correct model type (e.g., linear vs. nonlinear) for your data's underlying relationship. Your model may be overly simplistic.

- Consider Additional Variables: Your model might be missing key predictor variables that explain the variance in your data.

2. My R-squared value is high (close to 1), but the model's predictions seem inaccurate. Why? A high R-squared indicates that your model explains a large portion of the variance in the training data. However, this can be misleading, especially with small sample sizes or overly complex models [35]. This situation often points to overfitting, where your model has learned the noise in the training data rather than the generalizable pattern.

- Troubleshooting Step: Always validate your model using a holdout external test set that was not used in parameter optimization. Calculate the R-squared or other predictivity measures on this external set to ensure your model generalizes well [35].

3. When should I use Adjusted R-squared instead of R-squared? You should use Adjusted R-squared when comparing models with a different number of predictors (coefficients). The standard R-squared will always increase or stay the same when you add more predictors, even if they are non-informative [31]. The Adjusted R-squared accounts for the number of predictors and will penalize the addition of irrelevant variables, providing a better indicator of true fit quality for nested models [31].

4. What is a key advantage of using Maximum Likelihood Estimation? MLE has a very intuitive and flexible logic—it finds the parameter values that make your observed data "most probable" [33]. It is a dominant method for statistical inference because it provides estimators with desirable properties, such as consistency, meaning that as your sample size increases, the estimate converges to the true parameter value [33].

5. Can I get a negative R-squared, and what does it mean? Yes. While R-squared is typically between 0 and 1, it is possible to get a negative value for equations that do not contain a constant term (intercept). A negative R-squared means that the fit is worse than simply using a horizontal line at the mean of the data. In this case, it cannot be interpreted as the square of a correlation and indicates that a constant term should be added to the model [31].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

| Issue Encountered | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deceptively High R² | Overfitting on a small sample size [35]. | Check sample size (n) vs. number of parameters (m). Perform y-scrambling to test for chance correlation [35]. | Use a larger training set. Use Adjusted R-squared for model comparison [31]. Validate with an external test set [35]. |

| SSE Fails to Decrease | Model is stuck in a local optimum or has converged to a poor solution. | Check the optimization algorithm's convergence criteria. Plot residuals to identify patterns. | For MLE, try different starting values for parameters. For complex models like ANNs, adjust learning rates or network architecture [35]. |

| MLE Does Not Converge | Model misspecification or poorly identified parameters (e.g., too many for the data) [33]. | Verify the likelihood function is correctly specified. Check for collinearity among predictors. | Simplify the model. Increase the sample size. Use parameter constraints within the restricted parameter space [33]. |

| Poor Generalization to New Data | Model has high variance and has been overfitted to the training data. | Compare internal (e.g., cross-validation Q²) and external (e.g., Q²F2) validation parameters [35]. | Apply regularization techniques (e.g., Ridge, Lasso). Re-calibrate the model's hyperparameters. Re-define the model's applicability domain [35]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key methodological components and their functions for implementing these goodness-of-fit measures in computational research.

| Item | Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Training Set | The internal dataset used for optimizing the model's parameters. Used to calculate goodness-of-fit (R²) and robustness (via cross-validation) [35]. |

| External Test Set | A holdout dataset not used during model optimization. It is the gold standard for quantifying the true predictivity of the final model [35]. |

| Cross-Validation Script (LOO/LMO) | A computational procedure (e.g., Leave-One-Out or Leave-Many-Out) that assesses model robustness by iteratively fitting the model to subsets of the training data [35]. |

| Likelihood Function | The core mathematical function in MLE, defining the probability of the observed data as a function of the model's parameters. Its maximization yields the parameter estimates [33] [34]. |

| Optimization Algorithm | A numerical method (e.g., gradient descent) used to find the parameter values that minimize the SSE or maximize the likelihood function [33]. |

Standard Experimental Protocol for Model Validation

To ensure your model is both accurate and predictive, follow this general workflow, which aligns with OECD QSAR validation principles [35]:

- Data Splitting: Randomly split your complete dataset into a training set (typically 70-80%) and an external test set (20-30%). The test set must be set aside and not used in any model building steps.

- Model Training & Goodness-of-Fit Check: Optimize your model's parameters on the training set. Calculate the goodness-of-fit measures (SSE and R-squared) on this same training data.

- Internal Validation (Robustness): Perform cross-validation (e.g., Leave-One-Out or k-fold) on the training set. This involves creating multiple models with reduced training data and predicting the omitted points to obtain a cross-validated R² (Q²).

- External Validation (Predictivity): Use the finalized model, with all parameters fixed, to predict the held-out external test set. Calculate the predictive R² (Q²F2) and error metrics on these external predictions. This is the most critical step for assessing real-world utility [35].

- Final Reporting: Report all three aspects: goodness-of-fit (on training), robustness (internal cross-validation), and predictivity (on external test set) to provide a complete picture of your model's validity.

The following diagram illustrates this validation workflow and the key measures calculated at each stage.

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference in the goal of AIC versus BIC?

AIC and BIC are derived from different philosophical foundations and are designed to answer different questions. AIC (Akaike Information Criterion) is designed to select the model that best approximates the underlying reality, with the goal of achieving optimal predictive accuracy, without assuming that the true model is among the candidates [36]. In contrast, BIC (Bayesian Information Criterion) is designed to identify the "true" model, assuming that it is present within the set of candidate models being evaluated [36] [37].

2. When should I prefer AIC over BIC, and vice versa?

The choice depends on your research objective and sample size [38] [36] [37].

- Prefer AIC when your goal is prediction accuracy, you have a small sample size, or you believe the true model is overly complex and not among your candidates. AIC is asymptotically efficient, meaning it seeks to minimize prediction error [37].

- Prefer BIC when your goal is explanatory modeling and identifying the data-generating process, you have a large sample size, and you believe the true model might be among your candidates. BIC is consistent, meaning that as the sample size grows, it will select the true model with probability approaching 1 (if the true model is in the candidate set) [36] [37].

3. How do I interpret the numerical differences in AIC or BIC values when comparing models?

The model with the lowest AIC or BIC value is preferred. The relative magnitude of the difference between models is also informative, particularly for AIC. The following table provides common rules of thumb [37]:

| AIC Difference | Strength of Evidence for Lower AIC Model |

|---|---|

| 0 - 2 | Substantial/Weak |

| 2 - 6 | Positive/Moderate |

| 6 - 10 | Strong |

| > 10 | Very Strong |

For BIC, a difference of more than 10 is often considered very strong evidence against the model with the higher value [39].

4. Can AIC and BIC be used for non-nested models?

Yes. A significant advantage of both AIC and BIC over traditional likelihood-ratio tests is that they can be used to compare non-nested models [39] [40]. There is no requirement for one model to be a special case of the other.

5. My AIC and BIC values select different models. What should I do?

This is a common occurrence and reflects their different penalty structures. You should report both results and use your domain knowledge and the context of your research to make a decision [36]. Consider whether your primary goal is prediction (leaning towards AIC's choice) or explanation (leaning towards BIC's choice). It is also good practice to perform further validation, such as cross-validation, on both selected models.

6. Are AIC and BIC suitable for modern, over-parameterized models like large neural networks?

Generally, no. AIC and BIC are built on statistical theories that assume the number of data points (N) is larger than the number of parameters (k) [41]. In over-parameterized models (where k > N), such as many deep learning models, these criteria can fail. Newer metrics, like the Interpolating Information Criterion (IIC), are being developed to address this specific context [41].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Inconsistent model selection during a stepwise procedure.

- Potential Cause: Stepwise algorithms can be sensitive to the order in which variables are added or removed, potentially finding a local optimum rather than the global best model.

- Solution:

- Consider using an exhaustive search if the number of predictors is small [42].

- For a larger number of predictors, use a stochastic search method (e.g., based on Markov Chain Monte Carlo) which is less likely to get stuck in a local optimum and, when combined with BIC, has been shown to have a high correct identification rate [42].

Problem: AIC consistently selects a model that I believe is overly complex.

- Potential Cause: This is expected behavior. AIC's penalty for model complexity (2k) is less strict than BIC's penalty (k * log(n)), especially as sample size (n) increases [38] [36] [40].

- Solution:

Problem: The calculated AIC/BIC value is positive when the formulas seem to have a negative term.

- Potential Cause: This is a common point of confusion. The standard formulas are

AIC = 2k - 2ln(L)andBIC = k*ln(n) - 2ln(L), where L is the likelihood. However, for models with Gaussian errors, the log-likelihood is often expressed in terms of the residual sum of squares (RSS), which can result in a negative log-likelihood. The absolute value of AIC/BIC is not interpretable; only the differences between models matter [38] [39]. - Solution: Focus exclusively on the relative differences in AIC/BIC values between models fitted to the same dataset. The sign of the individual values is not important.

The following tables summarize the core quantitative aspects of AIC and BIC for easy comparison.

Table 1: Core Formulas and Components

| Criterion | Formula | Components |

|---|---|---|

| Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | AIC = 2k - 2ln(L) [39] [37] |

k: Number of estimated parametersL: Maximized value of the likelihood functionn: Sample size (not in formula) |

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | BIC = k * ln(n) - 2ln(L) [38] [37] |

k: Number of estimated parametersL: Maximized value of the likelihood functionn: Sample size |

Table 2: Comparative Properties and Performance

| Property | Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Find the best approximating model for prediction [36] | Find the "true" data-generating model [36] |

| Penalty Strength | Weaker, fixed penalty of 2k [40] |

Stronger, penalty of k * ln(n) grows with sample size [38] [40] |

| Asymptotic Behavior | Asymptotically efficient (good for prediction) [37] | Consistent (selects true model if present) [37] |

| Typical Use Case | Predictive modeling, forecasting | Explanatory modeling, theory testing |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Model Selection Workflow for Linear and Generalized Linear Models (GLMs)

This protocol outlines a standard methodology for using AIC and BIC in variable selection and model comparison for LMs and GLMs, as used in comprehensive simulation studies [42].

- Define the Model Space: Identify the set of potential predictor variables and the model family (e.g., linear regression, logistic regression).

- Specify Search Strategy: Choose a method to explore candidate models.

- Exhaustive Search: Evaluate all possible variable combinations. Feasible only for a small number of predictors (e.g., <15) [42].

- Stochastic Search: Use an algorithm (e.g., Metropolis-Hastings, Genetic Algorithm) to probabilistically explore the model space, which is efficient for high-dimensional spaces [42].

- Fit Candidate Models: For each candidate model defined by the search strategy, compute the maximum likelihood estimates for all parameters.

- Calculate Information Criteria: For each fitted model, compute the log-likelihood and then the AIC and BIC values using the formulas in Table 1.

- Rank and Select Models: Rank all candidate models from lowest to highest AIC (or BIC). The model with the minimum value is preferred.

- Validate Final Model: Perform diagnostic checks on the selected model (e.g., residual analysis, check for multicollinearity) and, if possible, validate its performance on a hold-out test set or via cross-validation.

Protocol 2: Simulating Model Recovery to Understand Criterion Behavior

This methodology is used in research to evaluate the performance of AIC and BIC under controlled conditions [36].

- Data Generation: Specify a "true" model with a fixed set of parameters. Generate multiple synthetic datasets from this model. The true model can be simple or complex.

- Model Fitting: On each generated dataset, fit a set of candidate models. This set should include the true model and several competing models (both simpler and more complex).

- Criterion Calculation: For each candidate model and each dataset, calculate the AIC and BIC.

- Recovery Rate Calculation: For each simulation run, determine which model was selected by AIC and which by BIC. Over many simulation runs, calculate the percentage of times each criterion correctly selects the true model (Correct Identification Rate) or a high-quality approximating model.

- Performance Analysis: Analyze how recovery rates change with factors like sample size, effect size, and correlation among predictors. Studies using this protocol often find that BIC has a higher correct identification rate, especially with larger sample sizes [42].

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key computational tools and concepts essential for applying information-theoretic criteria in model validation research.

| Tool / Concept | Function / Explanation | Relevance to AIC/BIC |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) | A method for estimating the parameters of a statistical model by finding the parameter values that maximize the likelihood function [40]. | Provides the foundational estimates for parameters (k) and the log-likelihood (L) required to compute AIC and BIC. |

| Log-Likelihood (ln(L)) | The natural logarithm of the likelihood function. It measures how well the model explains the observed data [40]. | The core measure of model fit (-2ln(L)) in both AIC and BIC formulas. A higher log-likelihood indicates a better fit. |