A Comprehensive Guide to Molecular Dynamics Simulation: From Foundational Protocols to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide to molecular dynamics (MD) simulation protocols, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development.

A Comprehensive Guide to Molecular Dynamics Simulation: From Foundational Protocols to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to molecular dynamics (MD) simulation protocols, tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational principles of MD, including system setup, force field selection, and integration algorithms. The guide then explores advanced methodological applications across biomedical fields, from studying protein-ligand interactions for virtual screening to modeling complex systems like lipid nanoparticles. It addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, offering solutions for sampling efficiency and force field accuracy. Finally, the article details rigorous validation techniques against experimental data and comparative analyses of different MD approaches, emphasizing the growing integration of machine learning to enhance simulation power and accuracy.

Understanding the Core Principles: A Beginner's Guide to MD Simulation Setup

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a computational technique that predicts the time-dependent behavior of every atom in a molecular system, such as a protein surrounded by water or a lipid bilayer [1]. The core of this method relies on a molecular mechanics force field—a mathematical model that describes the potential energy of a system as a function of its atomic coordinates. The force field is used to calculate the forces acting on each atom, which are then used to propagate the system forward in time according to Newton's laws of motion [2] [1]. The accuracy and reliability of an MD simulation are fundamentally dependent on the quality of the force field employed. This application note details the essential components of a classical force field, provides protocols for its application in biomolecular simulations, and presents a structured overview of current force field types and parameterization strategies.

Core Components of a Classical Force Field

A force field is a collection of parametric equations and corresponding parameter sets used to calculate the potential energy of a system of atoms [2] [3]. The total potential energy ((E{total})) in an additive force field is typically decomposed into bonded and non-bonded interactions: (E{total} = E{bonded} + E{non-bonded}) [2] [4].

Table 1: Core Energy Terms in a Biomolecular Force Field

| Energy Term | Mathematical Form | Physical Description | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | (E{bond} = \frac{k{ij}}{2}(l{ij}-l{0,ij})^2) [2] [4] | Energy change as a covalent bond stretches/compresses from its equilibrium length. | Force constant (k{ij}), equilibrium bond length (l{0,ij}). |

| Angle Bending | (E{angle} = k{\theta}(\theta{ijk}-\theta0)^2) [4] | Energy change as the angle between two adjacent bonds deviates from equilibrium. | Force constant (k{\theta}), equilibrium angle (\theta0). |

| Torsional Dihedral | (E{dihed} = k\phi(1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta))) [2] [4] | Energy barrier for rotation around a central bond, defined for four sequentially bonded atoms. | Force constant (k_\phi), periodicity (n), phase angle (\delta). |

| Improper Dihedral | (E{improper} = k\phi(\phi - \phi_0)^2) [4] | Harmonic potential used to enforce planarity (e.g., in aromatic rings or conjugated systems). | Force constant (k\phi), equilibrium angle (\phi0). |

| van der Waals (Non-bonded) | (V_{LJ}(r) = 4\epsilon \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{6} \right]) [2] [4] | Lennard-Jones potential describing short-range Pauli repulsion ((r^{-12})) and London dispersion attraction ((r^{-6})). | Well depth (\epsilon), van der Waals radius (\sigma). |

| Electrostatics (Non-bonded) | (E{Coulomb} = \frac{1}{4\pi\varepsilon0} \frac{qi qj}{r_{ij}}) [2] [4] | Coulombic interaction between fixed partial atomic charges. | Atomic partial charges (qi, qj). |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of how a force field calculates the total potential energy of a molecular system by summing these individual components.

Diagram 1: Hierarchy of potential energy terms in a classical force field. The total energy is a sum of bonded and non-bonded components, each comprising several specific interaction types.

Advanced Considerations: Force Field Types and Polarizability

Classical force fields can be systematically classified based on their level of detail and treatment of electronic effects, particularly polarization [5] [4] [3].

Table 2: Classification of Molecular Force Fields

| Classification | Description | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Class 1 (Additive) | Uses harmonic potentials for bonds/angles and fixed atomic charges. Computationally efficient but neglects polarization [4]. | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, OPLS-AA [5] [4] [3]. |

| Class 2 (Anharmonic) | Adds cubic/quartic terms and cross-coupling terms for more accurate vibrational spectra [4]. | MMFF94, UFF [4]. |

| Class 3 (Polarizable) | Explicitly includes electronic polarization, where the charge distribution responds to the local electric field, improving accuracy [5] [4]. | AMOEBA (induced dipoles), CHARMM-Drude (Drude oscillators) [5] [4]. |

| Coarse-Grained | Represents multiple heavy atoms as a single interaction center, sacrificing chemical detail for simulation speed and access to larger time/length scales [2] [3]. | Martini (4-to-1 mapping) [6]. |

Successful setup of an MD simulation requires several key "research reagents"—software tools, force fields, and parameter sets.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MD Simulations

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Biomolecular Force Fields | Pre-parameterized sets of equations and parameters for simulating proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and small molecules. | CHARMM36, Amber ff19SB, OPLS-AA/OPLS4 for modeling biomolecules and their interactions [5] [7] [3]. |

| Small Molecule Force Fields | Transferable force fields designed for drug-like molecules and organic compounds. | GAFF, OpenFF, ByteFF, CGenFF for parameterizing ligands, co-factors, and other small molecules [8] [3]. |

| Simulation Software Packages | Software engines that perform the numerical integration of the equations of motion. | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, OpenMM, CHARMM for running production MD simulations [5] [9] [1]. |

| Parameterization Tools | Tools that automatically assign force field parameters (atom types, charges, bonds, etc.) to novel molecules. | SwissParam, Antechamber, CGenFF program, MATCH, Force Field Builder [9] [8]. |

| Solvent Models | Pre-defined models for water and other solvents, which are critical for creating a physiological environment. | TIP3P, TIP4P, SPC (rigid); SWM4-NDP (polarizable) for solvating biomolecules [5] [9]. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Force Field in an MD Simulation

This protocol outlines the steps for setting up and running an MD simulation for a protein-ligand complex, a common scenario in drug development. The example uses the CHARMM force field and the GROMACS simulation package, a widely adopted combination in the research community [9].

System Preparation and Force Field Assignment

- Obtain Initial Coordinates: Acquire a PDB file for the protein and the small molecule ligand.

- Assign Force Field Parameters:

- Protein: Use the CHARMM36 force field for proteins [5].

- Ligand/Co-factor: Generate topology and coordinate files for the ligand (e.g., NADPH) and any other small molecules using a parameterization tool like SwissParam [9]. This tool automatically assigns atom types, charges, and bonded parameters compatible with the CHARMM force field.

- Assemble the System: Combine the protein and ligand topologies and coordinates into a single system file.

- Solvation: Solvate the system in a simulation box (e.g., an octahedral box) using an explicit solvent model such as TIP3P water [9].

- Neutralization: Add ions (e.g., Na⁺ or Cl⁻) to replace solvent molecules until the total system charge is neutralized [9].

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

- Energy Minimization: Run an energy minimization using an algorithm like steepest descent to relieve any bad contacts or steric clashes introduced during system setup. Minimize until the maximum force is below a chosen threshold (e.g., 10 kJ/mol) [9].

- System Equilibration - NVT Ensemble: Equilibrate the system with a fixed Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature (NVT) for a short time (e.g., 100-300 ps). Use a thermostat like V-rescale to maintain the target temperature (e.g., 300 K) [9].

- System Equilibration - NPT Ensemble: Further equilibrate the system with a fixed Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature (NPT) for a short time (e.g., 100-300 ps). Use a barostat to maintain the target pressure (e.g., 1 bar) [9]. This step ensures the system has the correct density.

Production MD and Analysis

- Production Simulation: Run a long, unconstrained production simulation, saving atomic coordinates at regular intervals (e.g., every 1-10 ps) for subsequent analysis.

- Trajectory Analysis: Analyze the saved trajectory using GROMACS tools or other software to calculate properties of interest, such as:

- Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the protein backbone.

- Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of residue positions.

- Ligand-protein interaction energies and hydrogen bonding patterns.

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

Force field development is a rapidly advancing field. Key trends include the move towards polarizable force fields like Drude and AMOEBA to more accurately model electrostatic interactions [5], and the application of data-driven and machine learning (ML) approaches for parameterization. For instance, the ByteFF force field uses a graph neural network trained on a massive quantum mechanics dataset to predict force field parameters for drug-like molecules, enabling expansive chemical space coverage [8]. Concurrently, efforts are underway to develop standardized, machine-readable data schemes and formats (e.g., TUK-FFDat) for force fields to improve interoperability, reproducibility, and usability across different simulation platforms [3].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has evolved into a mature technique for understanding the structure-to-function relationships of biological macromolecules by providing insights into their dynamic properties and conformational changes [10]. This protocol details the comprehensive steps required to transition from an initial Protein Data Bank (PDB) file to a production MD run, framed within the broader context of MD simulation protocol research. The procedure addresses critical preparation stages that ensure simulation stability and meaningful results, which is particularly relevant for applications in drug design and the study of biological mechanisms [11] [10]. The workflow encompasses structure validation, system setup, and equilibration phases, each of which is crucial for generating biologically relevant simulation data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential software tools and their primary functions in MD simulation preparation.

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| check_structure [11] | Structure Validation | Command-line utility for exhaustive structure quality checking, including alternate conformations and clashes. |

| VMD [11] | Visualization & Selection | Visual molecular dynamics; structure visualization and atomic selection for PDB file manipulation. |

| GROMACS [10] | MD Engine | Molecular dynamics simulation package; performs energy minimization, equilibration, and production runs. |

| AMBER [10] | MD Engine | Suite of biomolecular simulation programs; used for simulation with specific force fields. |

| NAMD [10] | MD Engine | Parallel MD code designed for high-performance simulation of large biomolecular systems. |

| BioBB [11] | Library | Provides the check_structure utility within its software suite. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Stage 1: Initial Structure Checking and Preparation

Principle: The foundation of a successful MD simulation is an error-free initial structure. Small errors in the input PDB file can cause simulations to become unstable or yield unrealistic results [11]. This first stage involves a thorough inspection and cleaning of the initial coordinate file.

Methodology:

- Retrieve and Inspect the PDB File: Download your target structure from the Protein Data Bank. Initially, use simple command-line tools to get an overview. The

grepcommand can identify non-protein atoms:grep "^HETATM" your_structure.pdb | wc -lprovides a count of HETATM records, often indicating water, ions, or ligands [11]. - Comprehensive Structure Checking: Use the

check_structureutility from the BioBB library for an exhaustive check [11].- Installation and Execution:

- Analysis of Output: The tool will report on critical issues [11]:

- Presence and count of non-protein molecules (e.g., crystallographic waters, ligands).

- Alternate conformations for specific residues, showing occupancy levels (e.g.,

ASP A20 CG A (0.50) B (0.50)). - Missing side-chain atoms or fragments.

- Potential clashes between atoms.

- Possible disulfide bonds (CYS residues involved in cross-links).

- Remediation and Cleaning:

- Removing Non-Protein Molecules: To create a protein-only file, use

check_structureto remove all ligands [11]: Alternative with VMD: Load the structure in VMD, use the atom selection"protein"to select all protein atoms, and write the selection to a new PDB file [11]. - Handling Alternate Conformations: Residues with multiple conformations (e.g., A and B) must be resolved to a single conformation to prevent topology errors. Using

check_structure, you can select specific conformers for specific residues [11]: Alternative with VMD: In VMD, use a selection command to choose one conformer and the protein backbone [11]. - Renaming Disulfide-Bonded Cysteines: For simulation preparation with AMBER, cysteines involved in disulfide bonds must be renamed from "CYS" to "CYX" in the PDB file. The

check_structuretool can identify and mark these residues [11]:

- Removing Non-Protein Molecules: To create a protein-only file, use

Stage 2: System Construction and Energy Minimization

Principle: After obtaining a clean protein structure, it must be solvated in a realistic environment (water box, ions) and have its energy minimized. This process removes any residual steric clashes and relaxes the system to a low-energy state, preparing it for the equilibration phase [10].

Methodology:

- Force Field Selection: Choose an appropriate force field (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS-AA) for your biomolecule. Parameters are not always interchangeable, and not all force-fields can represent all molecule types [10].

- System Building:

- Solvation: Place the protein into a box of explicit solvent molecules (e.g., TIP3P water). The box size should provide sufficient margin (e.g., 1.0-1.2 nm) between the protein and the box edges.

- Neutralization and Ion Concentration: Add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's net charge and to bring the ionic concentration to a physiologically relevant level (e.g., 150 mM).

- Energy Minimization: Run a minimization algorithm (e.g., steepest descent) to relieve any atomic clashes introduced during the solvation and ionization process. This step uses the force-field equations to find a low-energy configuration [10].

- Force Field Calculation: The potential energy is calculated using molecular mechanics force-fields, which are complex but fast-to-calculate equations representing bonds, angles, dihedrals, and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals and electrostatic) [10].

Stage 3: Equilibration and Production MD

Principle: Before data collection (production run), the system must be gently heated and equilibrated at the target temperature and pressure. This ensures the system is stable and possesses correct thermodynamic properties.

Methodology:

- Equilibration Protocol:

- Perform a two-step equilibration in the NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) and NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) ensembles.

- NVT Equilibration: Heat the system to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K) using a weak temperature coupling algorithm over a short duration (e.g., 100 ps). Positional restraints are typically applied to the protein heavy atoms to allow the solvent to relax around the protein.

- NPT Equilibration: Adjust the system density by applying a pressure coupling algorithm (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman) to reach the target pressure (e.g., 1 bar), again with protein restraints.

- Production Run:

- Remove all positional restraints on the protein.

- Launch the final, unrestrained MD simulation. The length of this run depends on the biological process being studied, but modern GPU-assisted systems can routinely simulate systems of ~50,000–100,000 atoms for hundreds of nanoseconds to microseconds [10].

- Integration of Motion: The simulation progresses by numerically integrating Newton's laws of motion. A time step of 1-2 femtoseconds is typically used, which is shorter than the fastest atomic vibrations to ensure numerical stability [10].

Workflow Visualization and Key Parameters

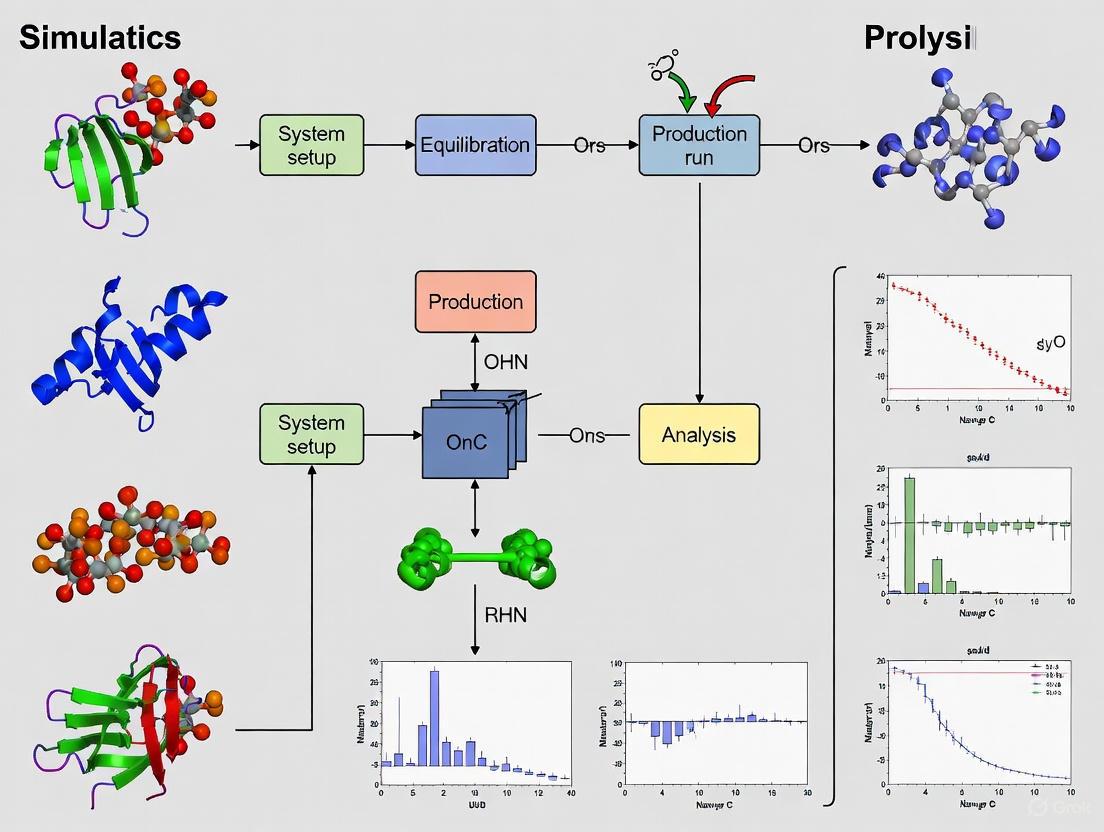

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and critical decision points of the complete MD setup protocol.

Table 2: Key parameters and their quantitative values for MD simulation stages.

| Simulation Stage | Key Parameter | Typical Value / Range | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| System Building | Solvent Box Margin | 1.0 - 1.2 nm | Prevents artificial interactions with periodic images. |

| Ionic Strength | 150 mM | Mimics physiological conditions. | |

| Energy Minimization | Force Tolerance | 100 - 1000 kJ/mol/nm | Convergence criterion for stopping minimization. |

| Equilibration (NVT/NPT) | Temperature | 310 K | Simulates biological body temperature. |

| Pressure | 1 bar | Simulates standard atmospheric pressure. | |

| Duration (per step) | 50 - 500 ps | Allows system relaxation with restraints. | |

| Production MD | Integration Time Step | 1 - 2 fs | Ensures numerical stability of the simulation. |

| Simulation Length | ns to μs | Captures the biologically relevant process of interest. |

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become indispensable in computational chemistry, biophysics, and materials science, enabling researchers to study the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. These simulations provide critical insights into dynamical behaviors and molecular interactions at an atomic level, playing a pivotal role in various stages of computational drug discovery. The accuracy and efficiency of MD simulations depend heavily on two fundamental components: the software engine used to perform the calculations and the force field that describes the potential energy surface of the molecular system. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of current MD software tools and force fields, framed within the context of establishing robust molecular dynamics simulation protocols for scientific research and drug development.

MD software packages provide the computational framework for simulating the Newtonian equations of motion for systems ranging from hundreds to millions of particles. While numerous packages exist, they share common algorithmic foundations while differing significantly in their implementation, optimization, and target applications.

Fundamental MD Algorithm

The core molecular dynamics algorithm follows a consistent global workflow across most software implementations, as exemplified by GROMACS [12]:

- Input initial conditions: The simulation requires potential interactions (V) as a function of atom positions, initial positions (r) of all atoms, and initial velocities (v) of all atoms

- Compute forces: Forces on each atom are calculated as F~i~ = -∂V/∂r~i~, summing non-bonded pair forces, bonded interactions, and restraining/external forces

- Update configuration: The movement of atoms is simulated by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion: d²r~i~/dt² = F~i~/m~i~

- Output step: Positions, velocities, energies, temperature, pressure, and other properties are written to output files

This process repeats for the required number of simulation steps, with modern implementations leveraging parallel processing and hardware acceleration to maximize performance.

Figure 1: Core Molecular Dynamics Algorithm Workflow. This fundamental workflow is common across most MD software packages, involving initialization, force calculation, configuration updating, and output generation in a cyclic manner.

Major MD Software Platforms

Several MD software packages have emerged as leaders in the field, each with distinct strengths, optimization strategies, and target applications. The table below provides a comparative overview of key MD software platforms:

Table 1: Comparison of Major Molecular Dynamics Software Platforms

| Software | Primary Focus | GPU Support | Parallelization | License | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Biomolecules (proteins, lipids, nucleic acids) | CUDA, OpenCL, SYCL | MPI, Thread-MPI | LGPL (≥4.6) | Extremely high performance, optimized kernels, user-friendly [13] [14] |

| AMBER | Biomolecular systems | Yes | MPI | Proprietary, free open source | Specialized for biomolecules, PMEMD engine, advanced sampling [15] |

| NAMD | Biomolecular systems | CUDA | MPI | Proprietary, free academic use | Excellent parallel scaling, integrated with VMD visualization [15] |

| AMS | General materials, catalysis | Yes | MPI, OpenMP | Proprietary | Multi-scale modeling, GUI, workflow tools [16] [17] |

| LAMMPS | Soft/solid-state materials, coarse-grain | Yes | MPI | GPL | Potentials for diverse materials systems [15] |

| OpenMM | Custom simulation methods | Yes | Python API | MIT | High flexibility, scriptable, excellent GPU performance [15] |

| CHARMM | Biomolecular systems | Yes | MPI | Proprietary | Commercial version with GUI (BIOVIA) [15] |

| Desmond | Drug discovery applications | Yes | MPI | Proprietary, commercial or gratis | High performance, comprehensive GUI [15] |

Performance Considerations and Hardware Selection

The computational demands of MD simulations necessitate careful hardware selection to maximize performance and efficiency. Different MD software packages have varying optimization characteristics:

CPU Selection: For molecular dynamics workloads, processor clock speeds often take precedence over core count. While sufficient cores are necessary, the speed at which a CPU can deliver instructions to other system components is crucial. A mid-tier workstation CPU with balanced higher base and boost clock speeds, like the AMD Threadripper PRO 5995WX, often provides better performance than extreme core-count processors for many MD workloads. Dual CPU setups with data center processors like AMD EPYC and Intel Xeon Scalable can be considered for workloads requiring more cores [18].

GPU Acceleration: Graphics Processing Units have become pivotal in accelerating molecular dynamics simulations by offloading computationally intensive tasks from CPUs. NVIDIA's latest offerings provide exceptional performance for MD applications [18]:

- NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada: 48 GB GDDR6 VRAM, 18,176 CUDA cores - ideal for memory-intensive simulations

- NVIDIA RTX 4090: 24 GB GDDR6X VRAM, 16,384 CUDA cores - excellent price/performance balance

- NVIDIA RTX 5000 Ada: 24 GB GDDR6 VRAM, ~10,752 CUDA cores - capable for standard simulations

Software-Specific GPU Recommendations:

- AMBER: Optimized for NVIDIA GPUs, with RTX 6000 Ada ideal for large-scale simulations and RTX 4090 excellent for smaller systems [18]

- GROMACS: Benefits significantly from high GPU throughput, with RTX 4090 providing excellent performance due to high CUDA core count [18]

- NAMD: Recognized for performance optimization with NVIDIA GPUs, significantly enhancing simulation times [18]

Multi-GPU Configurations: Utilizing multi-GPU systems can dramatically enhance computational efficiency and decrease simulation times for AMBER, GROMACS, and NAMD. Benefits include increased throughput, enhanced scalability, and improved resource utilization [18].

Force Fields for Molecular Dynamics

Force fields are mathematical models that describe the potential energy surface of a molecular system as a function of atomic positions. They represent a critical component in MD simulations, determining the accuracy and reliability of the resulting trajectories and properties.

Force Field Fundamentals

Conventional molecular mechanics force fields describe the molecular potential energy surface by decomposing it into various degrees of freedom [8]:

E~MM~ = E~MM~^bonded^ + E~MM~^non-bonded^

The bonded terms include:

- Bond stretching: E~bond~ = ∑~bonds~ k~r~ (r - r~0~)²

- Angle bending: E~angle~ = ∑~angles~ k~θ~ (θ - θ~0~)²

- Torsional rotations: E~torsion~ = ∑~torsions~ ∑~n~ k~ϕ~ [1 + cos(nϕ - ϕ~0~)]

The non-bonded terms include:

- Van der Waals interactions (typically Lennard-Jones potential)

- Electrostatic interactions (Coulomb's law)

Force field parameters include bonded parameters (equilibrium values r~0~, θ~0~, and ϕ~0~, and force constants k~r~, k~θ~, k~ϕ~) and non-bonded parameters (van der Waals parameters σ and ε, and partial charges q) [8].

Major Force Field Families

Table 2: Comparison of Major Molecular Mechanics Force Fields

| Force Field | Class | Coverage | Parameterization Approach | Compatible Software | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Traditional MM | Biomolecules | Empirical fitting, manual curation | AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD | Proteins, DNA, RNA, lipids [15] |

| CHARMM | Traditional MM | Biomolecules | Empirical fitting, QM/MM | CHARMM, NAMD, GROMACS | Biomolecular systems [15] |

| GAFF | Traditional MM | Drug-like molecules | Automated parameterization | AMBER, GROMACS | Small organic molecules [8] |

| OPLS | Traditional MM | Organic molecules | Liquid-state properties | GROMACS, LAMMPS | Condensed-phase systems [15] |

| GROMOS | Traditional MM | Biomolecules | Condensed-phase properties | GROMACS | Biomolecular simulations [15] |

| OpenFF | Modern MM | Drug-like molecules | SMIRKS-based patterns | OpenMM, other packages | Small molecule drug discovery [8] |

| ByteFF | Data-driven MM | Expansive chemical space | GNN-predicted parameters | AMBER-compatible | Drug discovery applications [8] |

| Espaloma | ML-based MM | Small molecules | Graph neural networks | OpenMM | Transferable parameters [8] |

Recent Advances in Force Field Development

Traditional look-up table approaches for force field parameterization face significant challenges with the rapid expansion of synthetically accessible chemical space. Recent efforts have leveraged machine learning techniques to address these limitations:

Data-Driven Force Fields: Modern approaches like ByteFF utilize large-scale, high-diversity quantum mechanics datasets with sophisticated machine learning techniques. ByteFF employs an edge-augmented, symmetry-preserving molecular graph neural network trained on 2.4 million optimized molecular fragment geometries with analytical Hessian matrices and 3.2 million torsion profiles [8].

Hybrid Approaches: Methods like Espaloma introduce end-to-end workflows where MM force field parameters are predicted by graph neural networks, showing promise for improving transferability and accuracy across diverse chemical spaces [8].

Systematic Validation: Recent benchmarks of twelve popular and emerging fixed-charge force fields across curated peptide sets reveal that while some force fields exhibit strong structural bias and others allow reversible fluctuations, no single model performs optimally across all systems. This highlights limitations in current force fields' ability to balance disorder and secondary structure, particularly when modeling conformational selection [19].

Figure 2: Modern Data-Driven Force Field Development Workflow. Contemporary force field development involves generating diverse molecular datasets, performing quantum mechanical calculations, training machine learning models for parameter prediction, and rigorous validation through iterative refinement cycles.

Integrated Protocols for Molecular Dynamics Simulations

This section provides detailed methodologies for setting up and running molecular dynamics simulations using different software platforms, with a focus on reproducibility and performance optimization.

GROMACS Simulation Protocol

GROMACS is renowned for its exceptional performance and comprehensive toolset for biomolecular simulations [13] [14]. The following protocol outlines a standard production MD workflow:

System Preparation:

- Obtain protein structure from PDB database and process with pdb2gmx to generate topology:

gmx pdb2gmx -f protein.pdb -o processed.gro -p topol.top - Solvate the system in a water box using solvate:

gmx solvate -cp protein.gro -cs spc216.gro -o solvated.gro -p topol.top - Add ions to neutralize charge using genion:

gmx genion -s em.tpr -o neutralized.gro -p topol.top -pname NA -nname CL -neutral

Energy Minimization:

- Run steepest descent energy minimization:

gmx mdrun -deffnm em -ntomp ${SLURM_CPUS_PER_TASK:-1} -nb gpu -pme gpu

Equilibration:

- NVT equilibration for 100ps with position restraints on protein:

gmx mdrun -deffnm nvt -ntomp ${SLURM_CPUS_PER_TASK:-1} -nb gpu -pme gpu - NPT equilibration for 100ps with position restraints:

gmx mdrun -deffnm npt -ntomp ${SLURM_CPUS_PER_TASK:-1} -nb gpu -pme gpu

Production MD: Execute production run with appropriate hardware resources:

Table 3: GROMACS Hardware Configuration Examples

| Resource Level | CPU Cores | GPU Configuration | Memory | Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard CPU | 8 (2 tasks × 4 cpus-per-task) | None | 4 GB per core | Medium-sized systems [20] |

| Single GPU | 12 CPU cores | 1 GPU (e.g., RTX 4090) | 2 GB per core | Typical biomolecular systems [20] |

| Multi-GPU | 24 (2 tasks × 12 cpus-per-task) | 2 GPUs (e.g., A100) | 2 GB per core | Large complexes, membrane systems [20] |

Example submission script for single GPU simulation on HPC cluster:

AMBER Simulation Protocol

AMBER provides specialized tools for biomolecular simulations, with excellent performance on NVIDIA GPUs [18] [20]:

System Preparation:

- Use tleap to prepare topology and coordinate files:

tleap -f system.in - Solvate system with explicit water model:

solvateOct system TIP3PBOX 10.0 - Add ions to neutralize system charge:

addIons system Na+ 0oraddIons system Cl- 0

Energy Minimization:

- Run minimization in two stages: first with restraints on solute, then without restraints

Equilibration:

- Heat system gradually from 0K to target temperature over 50-100ps with weak restraints

- Density equilibration at constant pressure for 100-500ps

Production MD: Execute production run with PMEMD CUDA implementation:

Performance Optimization Strategies

Enhanced Sampling: Implement hydrogen mass repartitioning to enable 4fs time steps:

Multi-GPU Scaling: For appropriate workloads, multi-GPU configurations can significantly accelerate simulations. GROMACS shows good strong scaling across multiple GPUs for sufficiently large systems [18] [20].

CPU-GPU Workload Balance: Optimize distribution of different force calculation components between CPU and GPU. In GROMACS, using -nb gpu -pme gpu -update gpu -bonded cpu typically provides optimal performance [20].

Successful molecular dynamics simulations require both software tools and appropriate hardware resources. The following table details key components of the MD research toolkit:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Dynamics

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Components | Function/Purpose | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Software | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, AMS | Core simulation engines | All-atom MD simulations [13] [15] [17] |

| Visualization & Analysis | VMD, PyMol, Chimera | Trajectory analysis, visualization | Result interpretation, publication figures [15] |

| Force Fields | AMBER, CHARMM, GAFF, OpenFF | Molecular mechanics potential functions | Defining interatomic interactions [15] [8] |

| Quantum Chemistry | Gaussian, ORCA, Quantum ESPRESSO | Reference calculations, parameterization | Force field development [17] [8] |

| System Preparation | PDB2GMX, tleap, packmol | Initial structure setup | Simulation initialization [13] [20] |

| HPC Resources | CPU clusters, GPU accelerators | Computational infrastructure | Production simulations [18] [20] |

| Specialized Hardware | NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada, A100 | GPU acceleration | Large-scale biomolecular simulations [18] |

| Workflow Tools | PLAMS, Jupyter notebooks | Automation, reproducibility | Protocol standardization, analysis [17] |

The selection of appropriate molecular dynamics software and force fields represents a critical decision point in establishing reliable simulation protocols for scientific research and drug development. GROMACS stands out for its exceptional performance and active development cycle, while AMBER provides specialized tools for biomolecular systems. AMS offers comprehensive multi-scale modeling capabilities with strong graphical interfaces. For force fields, traditional options like AMBER and CHARMM remain well-validated for biomolecular applications, while data-driven approaches like ByteFF show promise for expansive chemical space coverage. As the field evolves, the integration of machine learning methods into both simulation algorithms and force field development is likely to further enhance the accuracy and scope of molecular dynamics investigations, particularly for drug discovery applications where understanding molecular interactions at atomic resolution provides critical insights. Researchers should select tools based on their specific system characteristics, accuracy requirements, and available computational resources, while remaining attentive to emerging methodologies that may offer advantages for particular applications.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, creating a realistic simulation environment is paramount for obtaining biologically relevant results. The core of this environment is defined by three interconnected components: the application of periodic boundary conditions (PBC) to eliminate edge artifacts, the solvation of the molecular system to mimic its physiological context, and ion neutralization to achieve charge neutrality and physiological ionic strength. Together, these components form a periodic unit cell that serves as a minimal representation of a much larger, potentially infinite, system. This protocol details the theoretical underpinnings and practical procedures for establishing this environment, framed within the context of a broader thesis on MD simulation protocol research. It is tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals who require robust and reproducible simulation methodologies.

Theoretical Background

Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC)

The classical method to minimize edge effects in a finite system is to apply periodic boundary conditions [21]. In this approach, the atoms of the system are placed in a primary simulation box, which is surrounded in all directions by translated copies of itself. These copies are termed periodic images. This construction effectively removes physical boundaries, meaning an atom leaving the box on one side simultaneously re-enters from the opposite side [21] [22].

Simulations operate under the minimum image convention, which stipulates that each atom interacts only with the closest image of any other atom in the system [21]. This convention is crucial for the correct calculation of short-range non-bonded interactions. For long-range electrostatic interactions, more sophisticated methods like the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) algorithm are required [21] [23].

A critical consideration when using PBC is the cut-off radius ((R_c)) for short-range interactions. To satisfy the minimum image convention, the cut-off must not exceed half the length of the shortest box vector:

Furthermore, for efficiency in grid-based searching algorithms, an even stricter limitation may apply, such as (Rc < \min(ax, by, cz)) [21]. Violating these conditions can lead to unphysical interactions where an atom interacts with multiple images of the same atom.

Box Shapes

While a cubic box is the most intuitive, other space-filling shapes can be more efficient for simulating approximately spherical molecules, as they require fewer solvent molecules to fill the volume [21]. The most general space-filling shape is the triclinic box, which encompasses all other shapes. Table 1 compares common box types used in MD simulations.

Table 1: Characteristics of Common Periodic Box Types

| Box Type | Image Distance | Box Volume (relative to cube) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cubic | (d) | (d^3) (100%) | A rectangular box with all sides equal and angles of 90°. Simple but least efficient for spherical solutes. |

| Rhombic Dodecahedron | (d) | (0.707d^3) (~71%) | The smallest and most regular space-filling unit cell. Saves ~29% solvent compared to a cube with the same image distance [21]. |

| Truncated Octahedron | (d) | (0.770d^3) (~77%) | Closer to a sphere than a cube, offering savings in the number of required solvent molecules [21]. |

Solvation and Ion Neutralization

To mimic a physiological environment, the solvated system must be placed in an aqueous solution. This is achieved by explicitly filling the periodic box with water molecules. The choice of water model (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P) is force-field dependent [23] [24].

Most biomolecules carry a net charge in solution. Simulating a charged periodic system is problematic because the PBC would sum the net charge of the unit cell with its images to infinity, leading to unrealistic electrostatic energies. Therefore, ion neutralization is essential. This involves adding sufficient counter-ions (e.g., Na⁺ for a negatively charged solute, Cl⁻ for a positively charged one) to bring the total net charge of the system to zero [24]. Beyond neutralization, additional salt ions can be added to mimic a specific physiological ionic strength (e.g., 150 mM NaCl) [23].

Protocol: Setting Up the Simulation Environment with GROMACS

This protocol provides a detailed workflow for setting up a simulation environment for a protein using the GROMACS MD suite [24]. The process is broadly applicable to other biomolecules like nucleic acids.

Preparation and System Setup

Step 1: Obtain and Prepare Protein Coordinates

- Download the protein structure of interest from the RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org).

- Visually inspect the structure using a molecular viewer (e.g., RasMol, VMD).

- Pre-process the structure: remove crystallographic water molecules and any non-standard ligands. If ligands are required, their topology must be generated separately.

- Use the

pdb2gmxcommand to generate the molecule topology and coordinate file in GROMACS format. This step adds missing hydrogen atoms and allows you to select an appropriate force field (e.g.,ffG53A7for proteins with explicit solvent).

Step 2: Define the Periodic Box

- Use the

editconfcommand to place the protein in the center of a periodic box. A cubic box with a minimum distance of 1.0 nm (10 Å) between the protein and the box edge is a common starting point. For a more spherical solute, a rhombic dodecahedron is more efficient [21] [24].

Solvation and Ion Neutralization

Step 3: Solvate the System

- Use the

solvatecommand (also calledgmx solvatein newer versions) to fill the box with water molecules. The topology file is automatically updated to include the water molecules.

Step 4: Add Ions

- First, generate a pre-processed input file (

.tpr) using a parameter file (em.mdp) containing energy minimization settings.

- Use the

genioncommand to replace water molecules with ions. The system is neutralized first, then additional ions are added to achieve the desired ionic concentration.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MD Setup

| Reagent / Material | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Protein Structure File (.pdb) | The initial atomic coordinates of the biomolecule, obtained from the PDB or homology modeling. |

| Force Field (e.g., ffG53A7, AMBER-OL3) | A set of mathematical functions and parameters describing the potential energy of the system. Dictates the physical behavior of atoms [25] [24]. |

| Water Model (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P) | Explicit water molecules used to solvate the system, mimicking an aqueous biological environment [23] [24]. |

| Ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻, K⁺) | Counter-ions for system neutralization and salt ions to mimic physiological ionic strength. |

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps in setting up a simulation environment.

Application Example: RNA Stem-Loop in Explicit Solvent

A study on RNA stem-loop folding employed a protocol mirroring the one described above [23]. The initial A-form RNA structures were built for various sequences. Each system was first neutralized with a single Na⁺ ion, then solvated with 2000 TIP3P water molecules in a truncated octahedral box under PBC. This box shape was chosen for its computational efficiency relative to a cube. Finally, the system was brought to physiological conditions by adding five Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions, resulting in a final Na⁺ concentration of 0.162 M. The structures were subsequently minimized and equilibrated before production MD runs, which used an 8.0 Å cut-off for non-bonded interactions and the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method for long-range electrostatics [23].

Analysis and Visualization

Understanding "Wrapping"

During an MD simulation, molecules can diffuse freely across the boundaries of the primary simulation box. Consequently, in the raw trajectory, a molecule of interest may appear to have left the box. This is normal and does not mean it is no longer interacting with the system; it has simply moved into a neighboring periodic image [22].

For visual clarity, it is common practice to "wrap" the trajectory, meaning all atoms are translated back into the primary box. This requires defining a center for the box, which is typically the center of mass of the solute (e.g., the protein). Wrapping around an arbitrary solvent molecule instead would cause the solute to be split across the box boundaries, creating a visually fragmented structure [22]. Tools like trjconv in GROMACS or the moleculekit Python library can perform this operation.

Advanced Protocols and Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedicine

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a crucial computational tool for studying the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time, providing invaluable insights into biomolecular structure, dynamics, and function at an atomic level. For researchers investigating proteins, peptides, and protein-ligand complexes, MD simulations bridge the gap between static structural data from X-ray crystallography or NMR and dynamic biological mechanisms [26] [27]. The efficacy of these simulations depends critically on appropriate protocol selection, careful system setup, and proper analysis techniques. Within the broader context of molecular dynamics simulation protocol research, this application note provides detailed methodologies for simulating biomolecular systems, focusing on practical implementation, hardware considerations, and emerging trends that enhance simulation accuracy and efficiency. The protocols outlined here emphasize reproducibility and statistical rigor, acknowledging that uncertainty in derived parameters depends not only on simulation data but also on analysis protocols and data processing decisions [28].

Essential Hardware and Software Infrastructure

Hardware Selection for Biomolecular Simulations

Selecting appropriate hardware is fundamental for efficient MD simulations. The computational intensity of these simulations requires careful balancing of CPU, GPU, and memory resources to achieve optimal performance without unnecessary expenditure.

Table 1: Recommended Hardware Configurations for Biomolecular MD Simulations

| Component | Recommendation | Key Considerations | Example Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPU | Workstation-grade with high clock speeds | Prioritize clock speed over extreme core counts; sufficient PCIe lanes for multi-GPU setups | AMD Threadripper PRO 5995WX; Intel Xeon Scalable [29] |

| GPU | High-performance with substantial VRAM | CUDA core count; memory bandwidth; mixed-precision performance | NVIDIA RTX 6000 Ada (48 GB VRAM); NVIDIA RTX 4090 (24 GB GDDR6X) [29] |

| RAM | Capacity-matched to system size | Minimum 16 GB for setup; 128+ GB for production runs on large systems | DDR4/DDR5 with high bandwidth [26] |

| Storage | High-speed NVMe SSDs | Fast read/write for trajectory files (often terabytes) | PCIe 4.0/5.0 NVMe drives [30] |

For molecular dynamics workloads, processors with higher base and boost clock speeds often outperform those with exceptionally high core counts, as many simulation codes rely on the speed at which a CPU can deliver instructions to other components [29]. Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) are particularly valuable for accelerating computationally intensive tasks in MD simulations. NVIDIA's Ada Lovelace architecture GPUs, such as the RTX 6000 Ada and RTX 4090, provide massive parallel processing power through thousands of CUDA cores, significantly reducing simulation time for popular MD software including AMBER, GROMACS, and NAMD [29]. The choice between these GPUs often depends on simulation size, with the RTX 6000 Ada's 48 GB of VRAM being particularly advantageous for large, complex biomolecular systems that require extensive memory resources [29].

Multi-GPU setups can dramatically enhance computational efficiency for appropriate workloads, allowing researchers to simulate larger systems or achieve faster turnaround times [29]. Additionally, cloud-based GPU solutions offer a flexible alternative to local hardware investments, particularly for projects with variable computational needs or limited infrastructure budgets [30].

Software Ecosystem

The MD software landscape includes both open-source and commercial packages, each with particular strengths for biomolecular simulations:

- GROMACS: A free, high-performance MD software suite known for its excellent parallelization and efficiency on both CPUs and GPUs, particularly for biomolecular systems [31].

- AMBER: A leading MD package specifically optimized for biomolecular simulations, with excellent NVIDIA GPU integration and specialized tools for MM-PBSA/GBSA calculations [27].

- NAMD: Recognized for its parallel scaling capabilities on large systems and efficient utilization of NVIDIA GPUs [29].

- LAMMPS: A versatile MD code with capabilities extending beyond biomolecules to materials modeling, with recent extensions for AI-driven simulations through interfaces like ML-IAP-Kokkos [32] [33].

Detailed Simulation Protocols

System Setup and Equilibration

Proper system setup is crucial for generating physically meaningful simulation results. The following protocol outlines key steps for preparing biomolecular systems, with specific examples for protein simulations using GROMACS.

Initial Structure Preparation

The simulation process begins with obtaining high-quality structural data. Protein structures can be sourced from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) or generated through homology modeling when experimental structures are unavailable [26]. The initial structure must be carefully prepared by:

- Removing extraneous molecules: Eliminate crystallographic water molecules and non-essential ligands that might interfere with the simulation setup [26].

- Adding hydrogen atoms: Most MD packages automatically add hydrogens, which are often missing from PDB structures [26].

- Handling specialized residues: For non-standard residues or ligands, separate topology files must be created and integrated into the main molecular description [26].

The following GROMACS command converts a PDB file to GROMACS format while generating topology and adding hydrogens:

This command prompts users to select an appropriate force field, with "ffG53A7" being recommended for protein simulations with explicit solvent in GROMACS v5.1 [26].

Solvation and Ion Placement

Biomolecular simulations require solvation to mimic physiological conditions. After defining the simulation box with periodic boundary conditions to minimize edge effects, the system is solvated with water molecules [26]. The following command adds water molecules to the simulation box:

The topology file is automatically updated to include water molecules [26]. After solvation, the system must be neutralized by adding counterions based on the total charge calculation:

This command adds ions to neutralize the system—in this example, three anions to counter a +3.00 net charge [26].

Energy Minimization and Equilibration

Before production simulations, the system must undergo energy minimization to remove steric clashes and unfavorable interactions, followed by careful equilibration to stabilize temperature and pressure. The GROMACS grompp command collects parameters, topology, and coordinates into a single input file:

The resulting file (.tpr) contains the complete molecular description for simulation steps [26]. After minimization, systems typically undergo equilibration in stages—first with position restraints on the biomolecule while solvent relaxes (NVT ensemble for temperature stabilization), followed by full system equilibration without restraints (NPT ensemble for pressure stabilization).

Production Simulation and Analysis

Production simulations generate the trajectory data used for analysis, often running for nanoseconds to microseconds depending on the biological process being studied. For most biomolecular systems, the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) is used to mimic physiological conditions.

Analysis Methods

After production simulations, various analysis techniques extract biologically relevant information:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures structural stability by calculating the average distance between atoms of superimposed structures.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Quantifies flexibility of specific residues or regions over the simulation trajectory.

- Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Identifies collective motions and essential dynamics by reducing trajectory dimensionality [27].

- MM-PBSA/GBSA: Calculates binding free energies for protein-ligand complexes using Molecular Mechanics/Poisson-Boltzmann (Generalized Born) Surface Area approaches [27].

Table 2: Key Analysis Methods for Biomolecular Trajectories

| Analysis Method | Application | Software Tools | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD | Structural stability | GROMACS, AMBER, VMD | Convergence; structural drift |

| RMSF | Residual flexibility | GROMACS, CPPTRAJ | Flexible regions; binding sites |

| H-bond analysis | Interaction networks | GROMACS, VMD | Persistent interactions |

| PCA | Collective motions | GROMACS, Bio3D | Essential dynamics; conformational sampling |

| MM-PBSA/GBSA | Binding affinities | AMBER, GROMACS | Estimated binding free energies [27] |

Uncertainty Quantification

When deriving quantitative parameters such as diffusion coefficients from mean-squared displacement (MSD) data, researchers must recognize that uncertainty depends not only on simulation data but also on the choice of statistical estimator (OLS, WLS, GLS) and data processing decisions including fitting window selection and time-averaging approaches [28]. Proper uncertainty estimation requires careful attention to these analysis protocol details rather than treating uncertainty as inherent solely to the simulation data.

Advanced Applications and Emerging Methodologies

Multiscale Simulation Approaches

Advanced simulation strategies combine multiple computational techniques to address complex biological questions while managing computational costs. Recent methodologies integrate Brownian dynamics (BD) with all-atom MD simulations to compute protein-ligand association rates, leveraging the strengths of each approach [34]. BD efficiently simulates long-range diffusion and encounter complex formation, while MD captures short-range interactions and molecular flexibility with atomic detail [34]. This multiscale approach generates accurate association rate constants (kon) that align well with experimental data while remaining computationally feasible compared to pure MD approaches [34].

Multiscale simulation workflow combining Brownian dynamics and molecular dynamics.

AI-Enhanced Molecular Dynamics

Machine learning approaches are revolutionizing biomolecular simulations by dramatically increasing speed while maintaining accuracy. Neural network potentials like Egret-1 and AIMNet2 match or exceed quantum-mechanics-based simulation accuracy while running orders-of-magnitude faster [35]. These AI-driven approaches enable simulations that were previously computationally prohibitive, allowing researchers to explore longer timescales and larger systems.

The integration of PyTorch-based machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) with traditional MD packages like LAMMPS through interfaces such as ML-IAP-Kokkos represents a significant advancement [33]. This interface uses Cython to bridge Python and C++/Kokkos LAMMPS, ensuring end-to-end GPU acceleration while maintaining the flexibility of Python-based model development [33]. For researchers, this means the ability to incorporate sophisticated machine learning potentials into production simulations without sacrificing performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Biomolecular MD Simulations

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Coordinates | Starting structures for simulations | RCSB Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/) [26] |

| Force Fields | Molecular mechanics parameters for energy calculations | ffG53A7 (GROMACS); AMBER force fields; CHARMM [26] [27] |

| Molecular Topology Files | Molecular description including bonding, angles, charges | Generated by pdb2gmx; manually edited for ligands [26] |

| Parameter Files (.mdp) | Simulation parameters including integrator, temperature, pressure | GROMACS website; customized for specific protocols [26] |

| Visualization Software | Trajectory analysis and rendering | Rasmol; VMD; PyMOL [26] |

| Quantum Chemistry Data | Parameterization of novel molecules or validation | DFT calculations; reference quantum chemical calculations [27] |

This application note has detailed comprehensive protocols for simulating biomolecular systems, emphasizing the integrated nature of hardware selection, system setup, production simulation, and analysis. The field of molecular dynamics continues to evolve rapidly, with emerging trends including AI-enhanced simulations, multiscale approaches, and improved uncertainty quantification shaping future methodologies. By adhering to rigorous protocols and maintaining thorough documentation of each simulation step—including software versions, parameters, and analysis methods—researchers can ensure reproducible, scientifically valid results that advance our understanding of biomolecular systems and facilitate drug development efforts.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have emerged as indispensable tools in the rational design of complex drug delivery systems, particularly lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) and polymeric nanoparticles. The multi-scale and multi-parameter complexity of these nanocarriers makes computational approaches essential for bridging the gap between fundamental molecular properties and therapeutic efficacy [36]. LNPs represent extremely complex systems with nearly infinite design variables, making traditional experimental approaches alone insufficient for fully understanding and optimizing their performance [36]. MD simulations provide a powerful complementary tool that allows researchers to explore vast chemical and physical spaces efficiently, systematically modeling key interactions and predicting functional outcomes that would be impractical or impossible to achieve solely through experiments [36].

The hierarchical nature of LNP performance spans multiple scales—from molecular lipid chemistry and self-assembly mechanisms to particle morphology and in vivo pharmacokinetics—each requiring different computational approaches to extract meaningful insights [36]. Physics-based modeling, including computational quantum chemistry, all-atom and coarse-grained MD simulations, and computational fluid dynamics, offers unparalleled molecular and submolecular insights into LNP behavior, enabling investigators to study structural dynamics, lipid-RNA interactions, and endosomal escape mechanisms at a level of detail inaccessible to experimental methods [36]. This application note details specific MD methodologies, protocols, and applications for advancing LNP and polymer-based drug delivery system design within the broader context of molecular dynamics simulation protocol research.

MD Methodologies for Nanoparticle Characterization

All-Atom Molecular Dynamics (AA-MD)

All-atom MD simulations provide the highest resolution approach for investigating LNP structure and dynamics by explicitly modeling every atom in the system. AA-MD is particularly valuable for studying lipid membranes and membrane-protein interactions, with numerous applications aimed at enhancing understanding of membrane dynamics, membrane remodeling processes, and membrane proteins [36]. Recent applications of AA-MD models to examine LNP structure and dynamics have revealed crucial insights, though accurately modeling the protonation states of ionizable lipids in various membrane environments remains challenging [36].

The protonation states of ionizable lipids in LNPs are environment-dependent when the pKa values of ionizable sites are near the solution pH, significantly influencing overall LNP charge and interactions with biological systems [36]. To address this challenge, constant pH molecular dynamics (CpHMD) models have been developed, with scalable CpHMD implementations now performing at speeds comparable to standard MD models [36]. These methods implement λ-dynamics based on the linear interpolation of partial charges between protonated and deprotonated states of appropriately parameterized ionizable sites, enabling hundreds of ionizable sites to be modeled simultaneously [36]. Recent applications have demonstrated that CpHMD models can accurately reproduce apparent pKa values for different LNP formulations with mean average errors of 0.5 pKa units [36].

A key strength of atomistic adaptive membrane models is their accuracy in capturing complex supramolecular interactions, such as the hydrophobic effect that dictates membrane self-assembly [36]. However, the explicit treatment of all atoms, particularly solvent molecules that often constitute more than 70% of total atoms, incurs high computational costs [36]. These challenges can be partially addressed by establishing reduced model systems, such as bilayer or multilamellar membrane models combined with periodic boundary conditions to approximate larger LNP structures [36]. Enhanced sampling techniques—including umbrella sampling, metadynamics, replica exchange MD, steered MD, and biased MD—can be employed to model events occurring on timescales exceeding current AA-MD capabilities, enabling simulation of rare events crucial for LNP function such as membrane reorganization during manufacturing or endosomal release of LNP-encapsulated RNA [36].

Coarse-Grained Molecular Dynamics (CG-MD)

Coarse-grained MD simulations represent groups of atoms by simplified interaction sites, enabling modeling of larger systems and longer timescales compared to AA-MD simulations [36]. CG-MD helps researchers understand detailed molecular structures and LNP mechanisms that are often difficult to characterize experimentally [36]. The level of coarse-graining varies significantly across models, ranging from highly simplified representations (1-3 CG sites per lipid) to relatively fine-grained approaches (over 6 sites per lipid) such as the popular Martini force field [36].

Table 1: Comparison of MD Simulation Approaches for LNP Research

| Parameter | All-Atom MD | Coarse-Grained MD | Enhanced Sampling MD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Atomic-level (0.1-1 nm) | Molecular group level (1-5 nm) | Varies (atomic to molecular) |

| Timescale Coverage | Nanoseconds to microseconds | Microseconds to milliseconds | Microseconds to seconds |

| System Size Limit | ~100,000-1,000,000 atoms | ~1,000,000-10,000,000 atoms | Similar to AA-MD or CG-MD |

| Key Applications | Lipid protonation states, atomic interactions | Self-assembly, large-scale morphology | Rare events, energy barriers |

| Computational Cost | High | Moderate | High (per simulation) |

| Enhanced Sampling | Limited without specialized methods | Limited without specialized methods | Specialized for rare events |

Multiscale and Enhanced Sampling Approaches

Multiscale modeling frameworks represent the cutting edge of computational LNP research, hierarchically combining models at different resolutions to explore systems over larger time and spatial scales without sacrificing atomic-level accuracy [36]. Machine learning and artificial intelligence play increasingly crucial roles in these efforts, facilitating effective feature representation and linking various models for coarse-graining and back-mapping tasks [36].

Enhanced sampling techniques are specifically designed to improve sampling of rare events during MD simulations that would otherwise be extremely difficult to observe within limited classical MD timeframes [36]. However, each collective variable sampled using enhanced sampling methods incurs significant additional computational costs, restricting the number of CVs that can be efficiently sampled [36]. Furthermore, defining reasonable CVs for enhanced sampling often requires hypotheses about molecular mechanisms, making simulation outcomes dependent on initial assumptions and potentially hindering exploration of potential energy surfaces for CVs not well-represented in the selected set [36].

Quantitative MD Applications in LNP Optimization

LNP Self-Assembly and mRNA Encapsulation

MD simulations have provided crucial insights into LNP self-assembly mechanisms and mRNA encapsulation processes. Recent studies employing AA-MD simulations based on the lipid components and ratios of mRNA-1273 vaccines have demonstrated that lipid components self-assemble into nanoparticles under neutral conditions, with ionizable lipid SM-102 predominantly concentrating in the particle core [37]. Upon mixing with nucleic acids in acidic conditions, LNPs undergo disassembly, during which protonated SM-102 encapsulates mRNA through electrostatic interactions, forming stable hydrogen bonds [37].

Cluster structure analysis has revealed that the four lipid components in clinical LNPs distribute sequentially from outside to inside as DMG-PEG 2000, DSPC, cholesterol, and protonated SM-102 [37]. Furthermore, studies investigating different N/P ratios and acid types in nucleic acid solutions have demonstrated that LNPs constructed under low pH or low N/P ratios using citric acid exhibit larger volumes and more uniform distribution [37]. These findings provide scientific basis for optimizing LNP components to enhance mRNA vaccine encapsulation efficacy.

Table 2: Key Structural and Performance Parameters from LNP MD Simulations

| Parameter | Simulation Findings | Experimental Correlation | Impact on LNP Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipid Localization | SM-102 concentrates in particle core [37] | Enhanced encapsulation efficiency | Improves mRNA protection and endosomal escape |

| Component Distribution | Sequential distribution from outside: DMG-PEG 2000, DSPC, cholesterol, protonated SM-102 [37] | Affects LNP stability and cellular uptake | Optimizes structural integrity and drug release |

| Particle Size | 100-190 nm diameter range [38] | Narrow size distribution (PdI <0.2) | Influences biodistribution and cellular targeting |

| Protonation State | Environment-dependent pKa values [36] | Affects LNP surface charge | Crucial for endosomal escape and mRNA release |

| mRNA Encapsulation | Electrostatic interactions with protonated lipids [37] | >85% encapsulation efficiency [38] | Determines therapeutic payload protection |

Enhancing Endosomal Escape Mechanisms

Endosomal escape represents a critical bottleneck in LNP-mediated nucleic acid delivery, with only a small percentage of internalized nucleic acids successfully reaching the cytoplasm [38]. Recent MD investigations have explored innovative strategies to enhance this process, including the incorporation of cyclic disulfide-containing lipids (CDLs) into LNP formulations [38]. Studies demonstrate that CDL-incorporated LNPs achieve more than 2-fold higher transfection efficiency compared to LNPs with MC3 or SM102 alone, with intracellular analysis revealing that CDL additions significantly promote endosomal escape [38].

The mechanism behind enhanced endosomal escape involves cyclic disulfides with high ring tension (such as those derived from α-lipoic acid) that exhibit enhanced thiol-mediated membrane permeability compared to linear disulfides [38]. This approach differs fundamentally from conventional strategies that introduce disulfide bonds into fatty acid chains to facilitate intracellular degradation and payload release [38]. In vivo demonstrations have confirmed that CDL-incorporated LNPs administered subcutaneously in mice show significantly higher luciferase gene expression compared to LNPs without CDL, and LNPs encapsulating OVA antigen-encoding mRNA induce potent antitumor responses against lymphoma models [38].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: AA-MD Simulation of LNP Self-Assembly

Objective: To simulate and analyze the self-assembly process of LNPs and their interaction with mRNA using all-atom molecular dynamics.

Materials and Software:

- Simulation Software: GROMACS, NAMD, or AMBER

- Force Field: CHARMM36, Lipid21, or GAFFlipid

- Visualization Tools: VMD, PyMOL

- Lipid Components: Ionizable lipids (SM-102, MC3), phospholipids (DSPC), cholesterol, PEG-lipids (DMG-PEG 2000)

- mRNA Sequence: Polyadenylated mRNA or specific antigen-encoding sequences

Methodology:

- System Construction:

- Create initial coordinates for lipid molecules using molecular building tools (Packmol, CHARMM-GUI)

- Set up simulation boxes with lipid:ethanol solution ratios reflecting experimental conditions (e.g., 30:50 ionizable lipid content) [37]

- Implement periodic boundary conditions to approximate larger LNP structures [36]

Parameterization:

- Apply constant pH molecular dynamics (CpHMD) parameters for ionizable lipids to model environment-dependent protonation states [36]

- Implement λ-dynamics for linear interpolation of partial charges between protonated and deprotonated states [36]

- Set up electrostatic interactions using Particle Mesh Ewald method

Simulation Protocol:

- Energy minimization using steepest descent algorithm (5,000-10,000 steps)

- Equilibration in NVT ensemble (100 ps, 300 K) with position restraints on lipid atoms

- Equilibration in NPT ensemble (100 ps, 1 atm) with semi-isotropic pressure coupling

- Production run (100 ns-1 μs) with 2 fs time step

- Maintain temperature using Nosé-Hoover thermostat and pressure using Parrinello-Rahman barostat

Analysis:

- Calculate density distributions of lipid components relative to LNP center

- Determine radial distribution functions between lipid headgroups and mRNA phosphate groups

- Analyze solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) of mRNA throughout simulation

- Perform cluster analysis to identify predominant structural arrangements

Protocol 2: CDL-LNP Formulation and Evaluation

Objective: To design, formulate, and evaluate cyclic disulfide-containing lipid nanoparticles for enhanced mRNA delivery and endosomal escape.

Materials:

- Lipid Components: CDL library with varying alkyl chain lengths (C16-C20), ionizable lipids (MC3, SM102), DOPE, cholesterol, DMG-PEG2k [38]

- mRNA: Luciferase-encoding mRNA or antigen-encoding mRNA (e.g., OVA)

- Formulation Equipment: Microfluidic mixer, dialysis membranes

- Analytical Instruments: DLS for size measurement, TEM for morphology, fluorescence spectroscopy for encapsulation efficiency

Methodology:

- CDL Synthesis:

- Start with triethanolamine as base structure

- Condense with fatty acids of varying chain lengths (C16, C18, C20), unsaturation (0, 1, or 2 bonds), and branching using DCC and DMAP

- React intermediate with α-lipoic acid using DCC and DMAP to yield cyclic disulfide-containing lipids [38]

LNP Formulation:

- Prepare lipid mixtures with molar ratios: ionizable lipid (30 mol%), CDL (20 mol%), DOPE (10 mol%), cholesterol (38.5 mol%), DMG-PEG2k (1.5 mol%) [38]

- Dissolve lipids in ethanol and mRNA in acidic buffer (pH 4.0)

- Mix using microfluidic device with total flow rate 12 mL/min and flow rate ratio 3:1 (aqueous:organic)

- Dialyze against PBS (pH 7.4) to remove ethanol and concentrate LNPs

Characterization:

- Measure particle size, polydispersity index, and zeta potential using dynamic light scattering

- Determine mRNA encapsulation efficiency using Ribogreen assay

- Evaluate in vitro transfection efficiency in relevant cell lines

- Assess intracellular trafficking and endosomal escape using confocal microscopy

In Vivo Evaluation:

- Administer CDL-LNPs subcutaneously in mouse models

- Measure luciferase expression using IVIS imaging

- Evaluate antitumor efficacy in lymphoma models using OVA-encoding mRNA

Visualization of MD Workflows and LNP Mechanisms

Multiscale Modeling Framework for LNP Design

LNP Self-Assembly and mRNA Encapsulation Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for LNP MD Simulations and Experimental Validation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Simulation Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionizable Lipids | SM-102, MC3, DLin-MC3-DMA | Primary cationic component for mRNA complexation; enables endosomal escape through pH-dependent protonation [37] [38] | pKa 6.2-6.8; CpHMD parameters; λ-dynamics for protonation states [36] |

| Structural Lipids | DSPC, DOPE, Cholesterol | Enhance structural integrity, modify membrane fluidity, and improve stability [37] [39] | CHARMM36/Lipid21 parameters; bilayer formation properties; optimized mixing ratios [36] |

| PEGylated Lipids | DMG-PEG2000, DSG-PEG2000 | Reduce immune recognition, prevent aggregation, control particle size [37] [38] | 1.5-3.0 mol% in formulations; surface coverage parameters; steric stabilization models [36] |

| Specialty Lipids | Cyclic Disulfide Lipids (CDLs) | Enhance endosomal escape through thiol-mediated permeability; improve transfection efficiency [38] | Branching alkyl chains (C16-C20); cyclic disulfide moieties; 20 mol% incorporation [38] |

| Nucleic Acid Payloads | mRNA, siRNA, pDNA | Therapeutic cargo; chemical modifications enhance stability and reduce immunogenicity [40] [41] | Coarse-grained nucleotide models; electrostatic interaction parameters; encapsulation efficiency >85% [37] |

| Buffer Components | Citric Acid, Acetic Acid, Sucrose | Control pH during formulation; cryoprotection for lyophilization; affect LNP size and distribution [37] | pH 4.0 for encapsulation; ionic strength parameters; cryoprotectant interaction models [37] |

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide invaluable atomistic insights into chemical and biological processes but are fundamentally constrained by their accessible timescales. Many processes of biological and pharmaceutical interest, such as protein folding and conformational changes, occur on timescales much longer than what can be simulated with conventional MD. Enhanced sampling techniques have emerged as essential computational tools that overcome these limitations by accelerating the exploration of configuration space and facilitating the calculation of free energies. These methods can be broadly categorized into two families: collective variable (CV)-based methods such as metadynamics, which bias the simulation along preselected degrees of freedom, and generalized ensemble methods such as replica exchange, which expand the sampling space through non-physical pathways by modifying temperatures or Hamiltonians [42] [43]. The selection between these approaches represents a critical strategic decision in simulation protocol design, balancing the need for prior system knowledge against computational efficiency. This application note provides a comprehensive technical framework for implementing these powerful techniques, complete with structured quantitative comparisons and detailed experimental protocols tailored for research scientists and drug development professionals.

Theoretical Foundations

Replica Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD)

Replica exchange molecular dynamics (REMD) operates by simulating multiple non-interacting replicas of a system at different temperatures or with modified Hamiltonians [44]. At regular intervals, exchanges between neighboring replicas are attempted with an acceptance probability that preserves the correct Boltzmann distribution. For temperature REMD (T-REMD), this probability is calculated as:

[P(1 \leftrightarrow 2)=\min\left(1,\exp\left[ \left(\frac{1}{kB T1} - \frac{1}{kB T2}\right)(U1 - U2) \right] \right)]

where (T1) and (T2) are the reference temperatures and (U1) and (U2) are the instantaneous potential energies of replicas 1 and 2, respectively [44]. For simulations employing pressure coupling, an extension to the isobaric-isothermal ensemble incorporates volume changes:

[P(1 \leftrightarrow 2)=\min\left(1,\exp\left[ \left(\frac{1}{kB T1} - \frac{1}{kB T2}\right)(U1 - U2) + \left(\frac{P1}{kB T1} - \frac{P2}{kB T2}\right)\left(V1-V2\right) \right] \right)]

where (P1) and (P2) are reference pressures and (V1) and (V2) are instantaneous volumes [44].

Hamiltonian replica exchange (HREX) modifies the approach by creating replicas with different Hamiltonians, typically defined along an alchemical pathway. The exchange probability becomes:

[P(1 \leftrightarrow 2)=\min\left(1,\exp\left[ \frac{1}{kB T} (U1(x1) - U1(x2) + U2(x2) - U2(x_1)) \right]\right)]

where (U1) and (U2) represent different potential energy functions [44]. This approach is particularly valuable in free energy calculations and for systems where temperature changes would adversely affect the potential energy landscape.

Table 1: Replica Exchange Variants and Their Applications

| Method Variant | Key Equation Parameters | Primary Applications | Computational Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature REMD | T₁, T₂, U₁, U₂ | Protein folding, conformational transitions | Requires careful temperature spacing; number of replicas scales with system size |

| Hamiltonian REMD | U₁(x), U₂(x) | Alchemical free energy calculations, solvation free energies | Fewer replicas needed than T-REMD for large systems; requires λ-state definition |

| Gibbs Sampling REMD | All possible pairs exchange | Complex landscapes with multiple minima | No extra energy calculations; increased communication cost |

| Replica Exchange of Expanded Ensembles (REXEE) | Overlapping alchemical state sets | Multi-topology transformations, binding free energies | Decouples replica count from state count; enhanced parallelization |

Metadynamics

Metadynamics accelerates sampling by adding a history-dependent bias potential to the system's Hamiltonian along selected collective variables (CVs). This bias, typically composed of Gaussian deposits, discourages the system from revisiting previously sampled configurations [45]. The free energy surface is recovered from the negative of the accumulated bias, providing crucial thermodynamic information. The efficiency of metadynamics hinges critically on the selection of appropriate CVs that capture the slow modes of the system. Suboptimal CV choice can lead to hysteresis and inaccurate free energy estimates [46].

The fundamental relationship between the probability distribution along a CV and the free energy is:

[A(\xi)=-{k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T\ln(p(\xi))+C]