A Comprehensive Guide to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Data Analysis: From Foundations to Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

A Comprehensive Guide to Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Data Analysis: From Foundations to Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data analysis, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of scRNA-seq workflows, including quality control, normalization, and clustering. The guide then explores advanced methodological applications, such as machine learning integration and analysis in drug discovery. It addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for technical noise and data integration challenges. Finally, it outlines robust validation and comparative analysis techniques to ensure biological relevance and reproducibility. This resource synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends to empower robust and insightful single-cell research.

Mastering the scRNA-seq Pipeline: Essential Steps from Raw Data to Cell Clustering

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the characterization of gene expression at the resolution of individual cells. This technology has progressed substantially since its inception, with two primary methodologies emerging as dominant: plate-based and droplet-based approaches [1]. The selection between these platforms is a critical initial step in experimental design, impacting everything from cost and throughput to data quality and biological insights [2]. Within the broader context of a thesis on single-cell RNA sequencing data analysis, understanding the foundational technologies that generate the data is paramount, as the choice of wet-lab methodology directly influences downstream analytical strategies and computational requirements [3].

This document provides a comprehensive comparison of plate-based and droplet-based scRNA-seq methods, offering detailed protocols and application notes to guide researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing the most appropriate technology for their research objectives.

Technology Comparison: Plate-Based vs. Droplet-Based Methods

The core distinction between plate-based and droplet-based scRNA-seq methods lies in their mechanism for isolating individual cells and barcoding their transcripts [1]. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of each approach, which are crucial for experimental planning.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of plate-based and droplet-based scRNA-seq technologies

| Feature | Plate-Based scRNA-seq | Droplet-Based scRNA-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Lower (although combinatorial indexing improves scalability) [1] | Highest [1] |

| Cost per Cell | Highest, due to greater reagent consumption [1] | Lowest, due to microfluidics miniaturization [1] |

| Sensitivity | Highest [1] | Lower than plate-based [1] |

| Workflow | Flexible but labor-intensive (involves manual cell sorting and pipetting) [1] | Highly automated, but requires expensive microfluidics equipment [1] |

| Cell Isolation | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) into multi-well plates or combinatorial indexing [1] | Microfluidic encapsulation of single cells in droplets [1] [4] |

| Best For | Smaller-scale, in-depth studies; full-length transcript analysis [1] [5] | Large-scale studies, such as cell atlas projects and complex tissue analysis [1] [4] |

| Multiplet Rate | Controlled during cell sorting | Typically <5% when following optimal loading concentrations [4] |

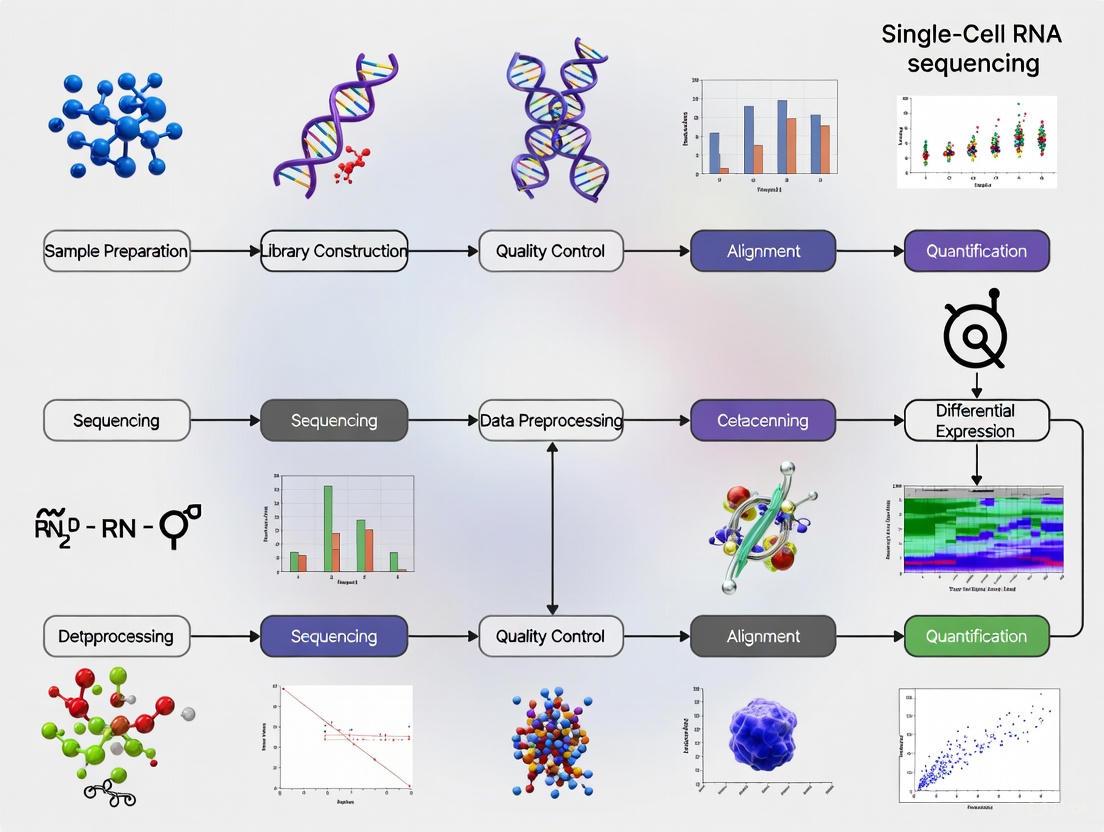

The following workflow diagram illustrates the fundamental procedural differences between these two core technologies.

Figure 1: Core Workflows for scRNA-seq Methods. This diagram contrasts the key steps in plate-based (green) and droplet-based (blue) scRNA-seq protocols, highlighting the initial cell isolation and barcoding strategies.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Core Protocol for Droplet-Based scRNA-seq (10x Genomics Chromium)

The droplet-based method is designed for high-throughput analysis, enabling the profiling of thousands to millions of cells in a single experiment [4].

Workflow Details:

- Single-Cell Suspension Preparation: Begin by preparing a high-quality single-cell suspension. Optimize cell concentration to 700–1,200 cells/μL and ensure viability exceeds 85% to minimize ambient RNA [4]. Maintain cells on ice to arrest metabolic activity and reduce stress-induced gene expression [2].

- Microfluidic Partitioning and Barcoding: Combine the cell suspension with barcoded gel beads and partition oil on a microfluidic chip. This generates monodisperse, nanoliter-scale Gel Bead-in-Emulsions (GEMs) [4]. Each GEM ideally contains a single cell and a single bead. The beads are coated with oligonucleotides containing unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), cell barcodes, and poly(dT) sequences for mRNA capture [1] [4].

- Within-Droplet Reactions: Inside each droplet, cells are lysed, releasing mRNA. The poly(A) tails of mRNA transcripts hybridize to the poly(dT) primers on the beads. Reverse transcription then occurs, producing barcoded cDNA molecules, with each molecule tagged with the same cell barcode and a unique UMI to correct for amplification biases [4].

- Post-Processing and Library Construction: The emulsion is broken, and the barcoded cDNA from all droplets is pooled. The cDNA is then amplified via PCR, and sequencing adapters are ligated to create the final library [1]. After quality control, the library is sequenced on a high-throughput platform.

Core Protocol for Plate-Based scRNA-seq (SMART-Seq2)

Plate-based methods, such as SMART-Seq2, prioritize sensitivity and full-length transcript coverage, making them ideal for focused studies [5].

Workflow Details:

- Cell Sorting and Lysis: Use fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate individual cells into the wells of a 96- or 384-well plate containing lysis buffer [1]. The plate is then centrifuged to ensure the cell is immersed in the buffer.

- Reverse Transcription and cDNA Amplification: Lyse the cells to release RNA. Reverse transcription is initiated using an oligo(dT) primer and a template-switching oligo (TSO), which allows for the synthesis of full-length cDNA with defined ends. The cDNA is then amplified via PCR to generate sufficient material for library construction [5].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: The amplified cDNA from each well is fragmented, and sequencing adapters are ligated. In modern protocols like SMART-seq3, cell-specific barcodes can be incorporated during library preparation, allowing for the pooling of multiple cells before sequencing. However, earlier protocols required separate library preparation for each cell [1]. The libraries are then sequenced.

Protocol for Single-Nucleus RNA-seq from Frozen Tissue

For tissues that are difficult to dissociate or uniquely valuable, such as archived clinical samples, single-nucleus RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) from frozen tissue is a robust alternative [6]. The following diagram outlines a simplified and optimized preparation method.

Figure 2: Single-Nucleus Isolation from Frozen Tissue. This protocol is optimized for long-term frozen brain tumor tissues but can be adapted for other challenging samples [6].

Key Considerations:

- This protocol is fast (under 30 minutes), low-cost, and yields intact nuclei with minimal debris [6].

- The resulting nuclei are compatible with both droplet-based (e.g., 10X Genomics Chromium, Drop-seq) and plate-based (e.g., Fluidigm C1) platforms [6].

- Two washes are recommended for low starting material to maximize yield, while three washes provide a debris-free supernatant for higher-quality input [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful scRNA-seq experiments rely on a suite of specialized reagents and instruments. The following table details key solutions and their functions in the experimental workflow.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Barcoded Gel Beads | Microbeads containing millions of oligonucleotides with cell barcodes, UMIs, and poly(dT) for mRNA capture and labeling within droplets [4]. | 10x Genomics Chromium systems; essential for droplet-based multiplexing. |

| Template-Switching Oligo (TSO) | An oligonucleotide that enables the synthesis of full-length cDNA with defined ends during reverse transcription, independent of poly(A) tails [4]. | Used in SMART-Seq2 and other plate-based protocols for superior transcript coverage. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotide sequences added to each transcript during reverse transcription; used to correct for PCR amplification bias and quantitatively count original mRNA molecules [4]. | Standard in droplet-based methods (e.g., 10x, Drop-seq) and present in modern plate-based methods (e.g., SMART-seq3). |

| Commercial Enzyme Cocktails | Pre-optimized mixtures of enzymes for rapid and reproducible tissue dissociation into single-cell suspensions. | Miltenyi Biotec kits and the gentleMACS Dissociator for standardized sample prep [2]. |

| Density Gradient Media | Solutions like Ficoll or Optiprep used to separate viable cells/nuclei from debris and dead cells via centrifugation [2] [6]. | Cleaning up peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) or nuclei isolated from brain tissue [2]. |

| Fixation Reagents | Chemicals (e.g., paraformaldehyde) that preserve cells or nuclei, allowing samples to be stored and batched for processing to minimize technical variability [2]. | Critical for large-scale projects, time-course experiments, and clinical samples with unpredictable arrival times. |

Critical Factors in Experimental Design

Sample Preparation and Quality Control

The foundation of a successful scRNA-seq experiment is a high-quality single-cell or single-nucleus suspension.

- Cells vs. Nuclei: The decision to sequence whole cells or nuclei depends on the sample type and research question. Nuclei are preferable for difficult-to-dissociate tissues (e.g., brain, fibrous tumors), frozen archived samples, or when working with very large cells that exceed the size limit of droplet-based systems [2] [6].

- Viability and Debris: Aim for sample viability between 70% and 90%. Minimize cell clumping and debris (<5% aggregation) by filtering the suspension and using calcium/magnesium-free media. Accurate cell counting is critical before loading onto any platform [2].

- Fresh vs. Fixed: While fresh processing is ideal, fixation allows for sample storage and batching, which is invaluable for clinical settings and large-scale projects. Fixed samples help control for batch effects and provide logistical flexibility [2].

Replication and Sample Size

Adequate replication is essential for robust and statistically sound conclusions.

- Biological vs. Technical Replicates: Biological replicates (e.g., cells from different donors) capture inherent biological variability and are necessary to verify reproducibility. Technical replicates (sub-samples from the same biological sample) measure noise from the protocol or equipment [2].

- Cell Number: The required number of cells depends on the biological question. Pilot studies or experimental planning tools like the Single Cell Experimental Planner can help determine the necessary scale. Technologies like combinatorial barcoding (e.g., Parse Biosciences' Evercode) allow for the processing of up to 1 million cells without the need for physical partitioning, offering great scalability [1] [2].

The choice between plate-based and droplet-based scRNA-seq methods is a fundamental strategic decision that shapes the entire research pipeline. Plate-based methods offer high sensitivity and are ideal for focused studies where detailed characterization of individual cells is paramount. In contrast, droplet-based platforms provide unparalleled scalability for large-scale profiling of complex tissues and discovery of rare cell types. The ongoing development of integrated multi-omics approaches, combined with improved bioinformatic tools, continues to expand the applications of scRNA-seq in fields like cancer research, reproductive medicine, and drug development [4]. By carefully considering the factors outlined in this document—throughput, cost, sensitivity, and sample requirements—researchers can select the most appropriate technology to generate high-quality data, thereby laying a solid foundation for meaningful biological insights and advancements in translational medicine.

In single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) research, the initial phase of raw data processing and quantification is a critical determinant of the validity of all subsequent biological interpretations. This foundational step transforms the billions of sequencing reads contained in FASTQ files into a structured gene expression count matrix, enabling the exploration of cellular heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution. The complexity of this process, involving meticulous quality control, genome alignment, and molecular counting, presents significant computational and methodological challenges. This application note delineates the established protocols and emerging best practices for this crucial conversion, framed within the rigorous context of academic research and drug development. A standardized approach ensures data integrity, minimizes technical artifacts, and provides a reliable foundation for uncovering novel biological insights and therapeutic targets, making proficiency in this initial stage indispensable for researchers and scientists in the field.

The journey from raw sequencing data to a quantitative gene expression matrix involves a series of computationally intensive and methodologically nuanced steps. The process begins with sequencing core facilities typically providing FASTQ files, which are text-based files storing nucleotide sequences and their corresponding quality scores for every read [7]. The primary objective of the initial processing pipeline is to generate a count matrix, where each row represents a gene, each column represents an individual cell, and each value contains the number of RNA molecules originating from a particular gene in a particular cell [7] [8].

Table 1: Key Components of a Processed Count Matrix

| Component | Format | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Sparse Matrix (MTX) | .mtx file |

A compact format storing the non-zero count data efficiently. |

| Cell Metadata | TSV/CSV file | Contains cellular barcode information identifying each cell. |

| Gene List | TSV/CSV file | Includes gene names, IDs, and other feature annotations. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points in a standard scRNA-seq raw data processing workflow, from the acquisition of FASTQ files to the final quality-checked count matrix.

Detailed Methodologies and Protocols

FASTQ File Processing and Alignment

The first computational stage involves processing the raw FASTQ files. An initial quality control (QC) check is performed using tools like FastQC or MultiQC to visualize sequencing quality and validate information [7]. This step identifies potential issues such as adapter contamination, low-quality bases, or overrepresented sequences, which could compromise downstream analysis.

Following QC, reads must be aligned to a reference genome. This essential step maps each sequenced read to its genomic location of origin. Common open-source alignment tools include STAR and kallisto | bustools [7]. The choice of alignment tool can depend on factors such as accuracy, speed, and computational resources. For UMI-based protocols, a critical subsequent step is deduplication, where PCR-amplified copies of the same original mRNA molecule are identified based on their shared UMI and counted only once, thus moving from read counts to molecule counts and mitigating amplification bias [8].

Table 2: Comparison of Selected scRNA-seq Data Processing Pipelines

| Pipeline/Tool | Best For / Key Feature | Input | Primary Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Ranger | 10x Genomics data integration; widely adopted standard [9]. | FASTQ | Filtered count matrix |

| Parse Biosciences' Trailmaker | Processing data from Parse's combinatorial barcoding method [7]. | FASTQ | Count matrix |

| zUMIs | Flexible pipeline for various UMI-based protocols [8]. | FASTQ | Count matrix |

| SEQC | Handles data from sequence-based single-cell methods [8]. | FASTQ | Count matrix |

| nf-core/scrnaseq | Community-built, portable Nextflow pipeline [7]. | FASTQ | Count matrix |

Post-Processing Quality Control and Filtering

Once a count matrix is generated, rigorous filtering is required to ensure that only high-quality data is retained. This involves distinguishing genuine cells from artifacts [7].

- Removing Background RNA: In droplet-based methods, droplets without cells can contain free-floating mRNA that is barcoded, creating background noise. Classifier filters or knee plots can distinguish barcodes corresponding to real cells from those associated with background. A common threshold is to set a minimum of 200-500 transcripts per cell, though this is adjustable based on biological context [7].

- Identifying Dead or Dying Cells: Cells with compromised membranes have a characteristically high fraction of reads mapping to mitochondrial genes. A common filtering threshold is 10-20% mitochondrial read fraction, though this varies by cell type. For example, nuclei should have virtually no mitochondrial reads [7] [8].

- Identifying and Removing Doublets: Doublets occur when two or more cells are tagged with the same barcode, potentially creating artifactual cell states. Bioinformatics tools like Scrublet (for Python) and DoubletFinder (for R) are designed to identify and remove doublets by comparing cell expression profiles to artificially generated doublets [7].

Tools like SoupX and CellBender can be applied to computationally estimate and remove ambient RNA contamination, a common issue in droplet-based datasets [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

The successful execution of a scRNA-seq study relies on a combination of wet-lab reagents and dry-lab computational resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent and Computational Solutions

| Category / Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Library Prep Kits | |

| 10x Chromium Single Cell 3' Kit | Integrated solution for droplet-based single-cell partitioning, barcoding, and library prep. |

| Parse Biosciences Single-Cell Kit | Uses combinatorial in-situ barcoding in a plate-based format [7]. |

| Critical Computational Tools | |

| Cell Ranger (10x Genomics) | End-to-end analysis pipeline for demultiplexing, alignment, and counting from FASTQ files [9]. |

| Seurat / Scanpy | Comprehensive R/Python environments for downstream analysis after count matrix generation [7] [8]. |

| Reference Genomes | |

| GENCODE Human (GRCh38) | High-quality, annotated reference genome for accurate read alignment. |

| Quality Control Tools | |

| FastQC / MultiQC | Provide initial assessment of sequencing run quality [7]. |

| CellBender | Removes technical artifacts and background RNA from count matrices [9]. |

Downstream Analysis and Advanced Computational Tools

Upon obtaining a high-quality count matrix, researchers embark on the biological discovery phase. This involves data normalization to account for differences in sequencing depth between cells, often followed by log-transformation to stabilize variance [7]. Dimensionality reduction techniques like PCA and UMAP are then applied to visualize cells in a low-dimensional space, facilitating the identification of clusters representing distinct cell types or states [7] [10].

Newer model-based dimensionality reduction methods, such as scGBM, are being developed to directly model count data and better capture biological variability while quantifying uncertainty in the low-dimensional representation [11]. For specialized applications like single-cell CRISPR screening (e.g., Perturb-seq), integrated analysis pipelines such as MUSIC are available to quantitatively estimate the effect of genetic perturbations on single-cell gene expression profiles [12].

A modern ecosystem of cloud-based platforms, including Nygen and BBrowserX, now offers user-friendly, no-code interfaces for performing these downstream analyses, making scRNA-seq data interpretation more accessible to non-bioinformaticians [10].

Quality control (QC) represents a critical first step in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data analysis, serving as the foundation for all subsequent biological interpretations. Within the broader thesis of scRNA-seq data analysis research, rigorous QC procedures are indispensable for distinguishing technical artifacts from genuine biological signals [13]. The primary goals of QC include generating metrics to assess sample quality and removing poor-quality data that could confound analysis and interpretation [14]. Without standardized QC practices, researchers risk deriving erroneous conclusions from clusters of stressed, dying, or multiple cells mistakenly identified as distinct cell populations [13]. This application note provides a comprehensive framework for implementing rigorous QC protocols, encompassing the filtering of cells, genes, and detection of doublets, specifically tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals working with scRNA-seq data.

Key Quality Control Metrics and Their Biological Significance

Standard QC Metrics for Cell Filtering

The evaluation of single-cell data quality relies on several key metrics that help identify and remove problematic barcodes. Table 1 summarizes the primary QC metrics, their biological or technical significance, and common filtering approaches.

Table 1: Essential QC Metrics for Single-Cell RNA-Seq Data

| QC Metric | Technical/Biological Significance | Common Filtering Approaches | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| UMI Counts | Represents absolute number of observed transcripts; low counts may indicate empty droplets or damaged cells; high counts may indicate multiplets [14]. | Data-driven thresholds (3-5 times standard deviation from median); arbitrary cutoffs; Cell Ranger caps at 500 UMIs [14]. | Heterogeneous samples may require cell type-specific thresholds; neutrophils naturally have low RNA content [15] [14]. |

| Genes Detected | Number of unique genes detected per cell; correlates with UMI counts; extreme values indicate multiplets or empty droplets [14]. | Similar approach to UMI filtering; often applied in conjunction [14]. | Varies by cell type; filtering thresholds should account for biological heterogeneity [14]. |

| Mitochondrial Gene Percentage | Increased levels associated with stressed, apoptotic, or low-quality cells where cytoplasmic RNA has leaked out [16] [14]. | Typical thresholds: 5-25% depending on cell type; data-driven thresholds (3-5 times SD/MAD from median) [14]. | Cardiomyocytes and other metabolically active cells naturally high mt content; filtering may introduce bias [14]. |

| Doublet Score | Computational prediction of droplets containing multiple cells; creates hybrid expression profiles [13] [14]. | Thresholds on doublet scores from specialized tools; subjective and data-dependent [14]. | Essential for preventing misinterpretation of multiplets as novel cell types or transitional states [13]. |

Platform-Specific QC Considerations

The performance of QC metrics can vary significantly across experimental platforms. A 2025 comparative analysis of technologies from 10× Genomics, PARSE Biosciences, and Honeycomb Biotechnologies revealed notable differences in baseline quality metrics when profiling challenging cell types like neutrophils [15]. For instance, mitochondrial gene expression levels were generally low (0-8%) across most technologies but reached up to 25% in Chromium Single-Cell 3′ Gene Expression v.3.1, highlighting the importance of platform-aware threshold setting [15].

Droplet-based technologies present unique QC challenges distinct from plate-based methods. Specifically, the majority of droplets (>90%) in microfluidic devices do not contain an actual cell, necessitating specialized algorithms to distinguish empty droplets containing only ambient RNA from cell-containing droplets [13]. Technologies like Parse Biosciences' Evercode, which employs combinatorial barcoding, may demonstrate different quality metric distributions compared to droplet-based platforms, sometimes showing less distinct bimodal distributions in gene expression for complex samples [15].

Comprehensive QC Workflow and Experimental Protocols

Integrated QC Pipeline

The QC process should follow a systematic workflow that incorporates multiple complementary approaches to ensure comprehensive quality assessment. The following diagram illustrates the integrated QC pipeline for scRNA-seq data:

Protocol: Step-by-Step QC Implementation

3.2.1 Data Preprocessing and Empty Droplet Detection

Step 1: Raw Data Processing - Process raw FASTQ files using Cell Ranger or equivalent alignment and UMI counting pipelines [16]. The output will include a feature-barcode matrix containing both cell-containing and empty droplets.

Step 2: Empty Droplet Identification - Apply algorithms such as

barcodeRanksandEmptyDropsfrom theDropletUtilspackage to distinguish true cells from empty droplets [13] [14]. These methods work by ranking barcodes based on UMI counts and identifying the "knee" point in the log-log plot of rank against total counts, where barcodes below this point represent empty droplets [13].

3.2.2 Comprehensive QC Metric Calculation

- Step 3: Metric Computation - Calculate standard QC metrics including:

3.2.3 Doublet Detection and Ambient RNA Correction

Step 4: Computational Doublet Identification - Run doublet detection algorithms such as DoubletFinder or Scrublet, which generate artificial doublets and compare gene expression profiles of barcodes against these in silico doublets to calculate a doublet score [14]. The threshold for doublet filtering is data-dependent and should be determined by examining the distribution of doublet scores.

Step 5: Ambient RNA Correction - Apply tools like SoupX, DecontX, or CellBender to estimate and remove contamination from ambient RNA [14]. These algorithms model the background RNA profile and subtract its contribution from each cell's expression counts [13].

Protocol: Threshold Determination and Cell Filtering

3.3.1 Data Visualization for Threshold Setting

- Step 6: Quality Metric Visualization - Generate violin plots, box plots, or density plots to visualize the distribution of QC metrics (UMI counts, genes detected, mitochondrial percentage) across all cells [14]. This visualization helps identify appropriate filtering thresholds before proceeding with actual filtering.

3.3.2 Iterative Filtering Approach

Step 7: Application of Filters - Implement filtering decisions based on the established thresholds. As emphasized in best practices, "begin with permissive filtering approaches, and then revisit the filtering parameters if the downstream analysis results cannot be interpreted" [14].

Step 8: Quality Assessment - Regenerate visualization plots post-filtering to confirm the removal of outliers while preserving biologically relevant cell populations.

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for setting appropriate filtering thresholds:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for scRNA-seq QC

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chromium Next GEM Single Cell 3ʹ | Wet-bench Reagent | Single-cell library preparation | 10x Genomics platform; optimized for cell suspensions [17] |

| Chromium Nuclei Isolation Kit | Wet-bench Reagent | Nuclei isolation for snRNA-seq | Frozen samples; difficult-to-dissociate tissues [17] |

| Cell Ranger | Computational Pipeline | Raw data processing, alignment, UMI counting | 10x Genomics data; generates feature-barcode matrices [16] |

| SingleCellTK (SCTK-QC) | R/Bioconductor Package | Comprehensive QC metric calculation and visualization | Integrates multiple QC tools; user-friendly interface [13] |

| EmptyDrops | Algorithm | Empty droplet detection | Distinguishes cells from empty droplets in droplet-based data [13] [14] |

| DoubletFinder | Algorithm | Doublet/multiplet detection | Identifies droplets containing multiple cells [14] |

| SoupX | Algorithm | Ambient RNA correction | Removes background RNA contamination [16] [14] |

Specialized Considerations for Challenging Cell Types

Certain cell types present unique challenges for QC filtering and require specialized approaches. Neutrophils, for instance, contain naturally low levels of RNA compared to other blood cell types, which can lead to their inadvertent removal during standard QC filtering [15] [14]. A 2025 study demonstrated that applying a minimum threshold of 50 genes and 50 UMIs was necessary to ensure neutrophil inclusion in downstream analyses [15]. Similarly, cardiomyocytes and other metabolically active cells may exhibit naturally high mitochondrial content, necessitating adjusted thresholds to prevent the loss of biologically intact cells [14].

The choice between single-cell and single-nuclei RNA sequencing also impacts QC procedures. snRNA-seq, while applicable to frozen biobanked samples, primarily captures nuclear transcripts, resulting in different gene detection profiles compared to scRNA-seq [17]. Research has shown that cell type proportion differences between annotation methods were larger for snRNA-seq than scRNA-seq, highlighting the need for tailored QC and annotation strategies for nuclear data [17].

Rigorous quality control represents a non-negotiable foundation for robust scRNA-seq data analysis. By implementing the comprehensive QC framework outlined in this application note—encompassing standardized metric calculation, platform-aware threshold setting, and specialized handling of challenging cell types—researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of their biological conclusions. The integrated approach combining multiple complementary QC methods provides a robust defense against technical artifacts that could otherwise compromise data interpretation. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve and find expanded applications in drug development and clinical biomarker discovery [15], establishing and maintaining rigorous QC protocols will remain essential for generating biologically meaningful and reproducible results.

Data Normalization and Feature Selection for Dimensionality Reduction

Within the broader context of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data analysis research, the steps of data normalization and feature selection are critical prerequisites for effective dimensionality reduction. The high-dimensional, sparse, and noisy nature of scRNA-seq data, characterized by an abundance of zero counts and technical variability from sources like sequencing depth and capture efficiency, necessitates robust preprocessing pipelines [18]. The curse of dimensionality further underscores that higher-dimensional data often contains more noise and redundancy, which does not necessarily benefit downstream analysis [19]. The choices made during normalization and feature selection have a profound and direct impact on the performance of subsequent dimensionality reduction techniques, such as PCA, UMAP, and t-SNE, which are essential for visualizing cellular heterogeneity, identifying novel cell types, and tracing developmental lineages [20] [21]. Consequently, this application note provides detailed protocols and a comparative analysis of current methods to guide researchers and drug development professionals in constructing reliable and interpretable analysis workflows.

Comparative Analysis of Methods

Data Normalization Methods

Normalization aims to remove technical variation while preserving biological variation, making gene counts comparable within and between cells [18] [22]. The table below summarizes commonly used normalization methods, their underlying models, and key features.

Table 1: Comparison of Single-Cell RNA-Seq Data Normalization Methods

| Method | Model/Approach | Key Features | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Log-Norm | Global scaling + log transformation | Divides counts by total per cell, scales (e.g., 10,000), adds pseudocount (e.g., 1), and log-transforms. Simple and widely used. | Seurat (NormalizeData), Scanpy (normalize_total, log1p) |

| SCTransform | Regularized Negative Binomial GLM | Models counts with sequencing depth as covariate; outputs Pearson residuals that are independent of sequencing depth. | R (Seurat) |

| Scran | Pooling and linear decomposition | Pools cells to sum counts, normalizes against a reference pseudo-cell, and solves linear system for cell-specific size factors. | R (scran) |

| BASiCS | Bayesian Hierarchical Model | Uses spike-in genes or technical replicates to jointly model technical and biological variation. | R (BASiCS) |

| SCnorm | Quantile Regression | Groups genes by dependence on sequencing depth; estimates and applies group-specific scale factors. | R (SCnorm) |

| Linnorm | Linear model and transformation | Optimizes a transformation parameter to achieve homoscedasticity and normality before linear model fitting. | R (Linnorm) |

| PsiNorm | Pareto Type I Distribution | Uses the shape parameter of a Pareto distribution as a multiplicative normalization factor; highly scalable. | R (PsiNorm) |

Feature Selection Methods

Feature selection reduces dimensionality by identifying a subset of informative genes, which is crucial for mitigating noise and enhancing the performance of downstream integration and clustering [23] [24]. The following table benchmarks different feature selection approaches.

Table 2: Comparison of Feature Selection Methods for scRNA-seq Data

| Method | Principle | Use Case | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Highly Variable Genes (HVG) | Selects genes with high variance-to-mean ratio. | Standard practice for reference atlas construction and integration [23]. | Sensitive to normalization and pseudocount choice [24]. |

| Deviance-based | Ranks genes by binomial deviance from a constant expression null model. | Effective for capturing biological heterogeneity; works on raw counts [24]. | Computed in closed form; implemented in the scry R package. |

| Highly Expressed Genes | Selects genes with the highest average expression. | A simple, traditional approach. | May select ubiquitously expressed housekeeping genes. |

| Stably Expressed Genes (e.g., scSEGIndex) | Selects genes with minimal biological variability. | Serves as a negative control in benchmarking [23]. | Not suitable for identifying biologically variable features. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol I: Data Normalization using SCTransform

SCTransform is a robust method that effectively normalizes data and stabilizes variance in a single step [22].

Detailed Methodology:

- Input Data: Begin with a raw UMI count matrix ((X_{\text{raw}})) where rows are genes and columns are cells.

- Model Fitting: For each gene, a regularized Negative Binomial generalized linear model is fitted: ( \text{UMI Count} \sim \log(\text{Total UMI per Cell}) ) This model accounts for the relationship between gene expression and sequencing depth.

- Parameter Regularization: Model parameters (intercept, slope, dispersion) are regularized based on their relationship with the gene's mean expression across cells. This step prevents overfitting, which is critical for noisy scRNA-seq data.

- Residual Calculation: The regularized parameters are used to compute Pearson residuals: ( \text{Residual} = \frac{\text{Observed Count} - \text{Expected Count}}{\sqrt{\text{Variance}}} ) These residuals are independent of sequencing depth and are used for downstream analysis.

Protocol II: Feature Selection using Deviance

This protocol uses a deviance-based method to select highly informative genes directly from raw counts, minimizing biases introduced by transformation [24].

Detailed Methodology:

- Input Data: Use the raw count matrix without prior normalization.

- Deviance Calculation: For each gene, calculate the binomial deviance. This metric quantifies how poorly the gene's expression profile fits a constant (null) model across all cells. Genes with high deviance are highly variable and informative.

- Gene Ranking: Rank all genes in descending order of their binomial deviance value.

- Feature Selection: Select the top (n) genes (e.g., 2,000-4,000) from the ranked list for all subsequent dimensionality reduction and analysis.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical sequence of preprocessing steps, from raw data to a matrix ready for dimensionality reduction.

Workflow for scRNA-seq Preprocessing

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Item | Function | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Transcriptome | A pre-assembled collection of genomic sequences and annotations for a species. | Used during primary analysis (e.g., by Cell Ranger) to align sequencing reads and identify transcripts [21]. |

| Spike-in RNA Controls | Exogenous RNA molecules added in known quantities to the cell lysate. | Serves as a standard baseline for technical variation estimation and normalization, e.g., in BASiCS [18] [22]. |

| UMIs (Unique Molecular Identifiers) | Short random nucleotide sequences that label individual mRNA molecules. | Corrects for PCR amplification biases during library preparation, enabling accurate digital counting of transcripts [18] [21]. |

| Cell Barcodes | Short nucleotide sequences that uniquely label each cell. | Allows sequencing reads from a single cell to be pooled and later computationally demultiplexed [21]. |

| Scanpy / Seurat | Comprehensive software toolkits for single-cell data analysis. | Provide integrated functions for the entire analysis workflow, including normalization, feature selection, dimensionality reduction, and clustering [19] [24] [22]. |

Implementation and Downstream Integration

The choice of normalization and feature selection methods directly influences the quality of the low-dimensional embedding. For instance, it has been shown that Highly Variable Gene selection is effective for producing high-quality data integrations and query mappings [23]. Furthermore, novel model-based dimensionality reduction techniques like scGBM, which directly models raw counts using a Poisson bilinear model, are emerging as powerful alternatives to the standard workflow of transformation followed by PCA, as they can better capture biological signal and avoid artifacts [11].

The following diagram summarizes the integration of these preprocessing steps into the broader scRNA-seq analysis pipeline, leading to biological insights.

Full scRNA-seq Analysis Pipeline

There is no single best-performing method for all datasets and biological questions. Therefore, it is considered good practice to test different normalization and feature selection strategies, using metrics from downstream analyses—such as cluster separation, conservation of biological variation, and batch effect removal—to guide the selection of the most appropriate method for a given study [23] [18] [22].

Unsupervised Clustering and Cell Type Annotation Strategies

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized the study of cellular heterogeneity by enabling the transcriptomic profiling of individual cells [25]. A foundational application of this technology is the identification of distinct cell types and states through unsupervised clustering, a process that groups cells based on transcriptional similarity without prior biological knowledge [26]. Following clustering, the critical step of annotation assigns biological identity to these computationally derived groups, bridging the gap between statistical patterns and cellular function [8] [26].

This protocol details a standardized workflow for unsupervised clustering and cell type annotation, framed within the broader context of scRNA-seq data analysis research. It is designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to delineate cellular populations in complex tissues, such as those found in tumor microenvironments, stem cell niches, and developing organs [27]. The guidance integrates established best practices with emerging methodologies, including the novel Average Overlap metric for refining cluster annotation [26].

Experimental Design and Prerequisites

Key Considerations Before Starting

Successful single-cell analysis requires careful pre-planning. Two principal requirements must be met prior to embarking on a project:

- Genomic Resource Availability: The sequencing data can only be interpreted if sequences can be assigned to gene models. Mapping reads to a genome with complete gene annotations is ideal. If unavailable, a high-quality transcriptome assembly must be generated [28].

- Cell Suspension Protocol: Generating quality single-cell or single-nuclei suspensions from the tissue of interest is a non-trivial hurdle and may require months of wet-lab optimization. The decision to sequence single cells or single nuclei depends on the biological question. Single cells generally capture more mRNA, providing a broader view of the transcriptome, while single nuclei are better for difficult-to-dissociate tissues (e.g., neurons) and allow for multiome studies combining transcriptomics with ATAC-seq [28].

Experimental Design for Valid Batch Effect Correction

Batch effects are a major challenge in scRNA-seq. To ensure biological variability can be separated from technical artifacts, the experimental design must allow for batch effect correction. The BUSseq method mathematically proves that true biological variance can be separated under three valid experimental designs [29]:

- Completely Randomized Design: Each batch measures all cell types. This is the most robust design but can be costly or impractical.

- Reference Panel Design: A reference batch contains all cell types, while other batches may contain subsets.

- Chain-Type Design: Batches are linked by shared cell types in a chain-like manner, without requiring a single universal reference.

A completely confounded design, where batch and cell type are perfectly correlated, is non-identifiable, and batch effects cannot be corrected through any computational method [29].

Wet-Lab Protocols and Reagent Solutions

The primary steps in scRNA-seq encompass single-cell isolation, cell lysis, reverse transcription, cDNA amplification, and library preparation [27]. Commercial kits and reagents now exist for all wet-lab steps, making this technology accessible to non-specialists [25].

Sample Preparation and Cell Isolation

The initial stage involves extracting viable, individual cells from the tissue of interest. For tissues where dissociation is challenging, or when working with frozen samples, single-nuclei RNA-seq (snRNA-seq) is a viable alternative. "Split-pooling" techniques using combinatorial indexing can process up to millions of cells without expensive microfluidic devices [27] [25].

Molecular Barcoding and Amplification

After RNA is converted to cDNA, the molecules are amplified by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or in vitro transcription (IVT). To mitigate amplification biases, Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) are used to label each individual mRNA molecule during reverse transcription, improving the quantitative accuracy of the data [27]. Protocols like CEL-Seq, MARS-Seq, Drop-Seq, inDrop-Seq, and 10x Genomics have incorporated UMIs [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Commercially Available Single-Cell Solutions

| Commercial Solution | Capture Platform | Throughput (Cells/Run) | Key Features and Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Microfluidic oil partitioning | 500 – 20,000 [28] | High capture efficiency (70-95%); supports cells, nuclei, and fixed material [28]. |

| BD Rhapsody | Microwell partitioning | 100 – 20,000 [28] | Allows for larger cell sizes (<100 µm); enables targeted transcript detection [28]. |

| Parse Evercode | Multiwell-plate | 1,000 – 1M [28] | Very low cost per cell; ideal for large-scale projects; requires high cell input [28]. |

| Fluent/PIPseq (Illumina) | Vortex-based oil partitioning | 1,000 – 1M [28] | No microfluidics hardware needed; no restrictions related to cell size [28]. |

Computational Analysis Workflow

The computational analysis of scRNA-seq data begins with a count matrix (cells x genes) and proceeds through a series of steps to identify and annotate cell types.

Diagram 1: scRNA-seq Analysis Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key computational steps from raw data to biological interpretation, highlighting critical transitions between major stages.

Pre-Processing and Quality Control

Before analysis, the count matrix must be examined to remove poor-quality cells, which add technical noise and obscure biological signals [30]. QC is typically performed based on three key metrics, visualized in the diagram below.

Diagram 2: Quality Control Metrics. This diagram illustrates the three primary QC covariates used to filter low-quality cells and the biological or technical phenomena they indicate.

- QC Metrics and Thresholding: The distributions of these QC covariates are examined for outliers, which are filtered out by thresholding [8]. As detailed in Diagram 2, cells with low counts/genes and high mitochondrial content often indicate dead or dying cells, while cells with very high counts/genes may be doublets (multiple cells captured as one) [8]. These metrics must be considered jointly, as interpreting any one in isolation can lead to misinterpretation [8]. Thresholds should be as permissive as possible to avoid filtering out viable cell populations unintentionally.

Data Normalization, Feature Selection, and Dimensionality Reduction

Following QC, the data is normalized to remove technical variations (e.g., in sequencing depth) and make expression levels comparable across cells [8]. This is often achieved by scaling counts to a constant total per cell (e.g., 10,000) and log-transforming the result.

- Feature Selection: To reduce noise and computational complexity, analysis focuses on Highly Variable Genes (HVGs) that drive cell-to-cell heterogeneity. These genes are more likely to contain biologically meaningful information for distinguishing cell types [8].

- Dimensionality Reduction: Principal Component Analysis (PCA) is applied to the HVGs to create a lower-dimensional representation that captures the major axes of variation in the data. These principal components are then used for unsupervised clustering and for further non-linear dimensionality reduction with methods like UMAP or t-SNE, which provide 2D or 3D visualizations of cell relationships [8].

Protocol for Unsupervised Clustering

Clustering groups cells based on their transcriptional similarity in the reduced dimensional space (e.g., the top principal components). A common and effective method is the graph-based approach.

Materials (Computational): A normalized and scaled single-cell object in R (Seurat) or Python (Scanpy).

Procedure:

- Construct a k-Nearest Neighbor (k-NN) Graph: Model the cellular data as a graph, where each cell is a node. Connect each cell to its

kmost similar cells (default k=20 is often a good starting point) based on Euclidean distance in PCA space. - Refine Edge Weights: Apply the Jaccard similarity or a similar method to refine the edge weights between cells, reflecting the shared overlap of their neighborhoods.

- Community Detection: Use a community detection algorithm, such as the Louvain or Leiden algorithm, to partition the k-NN graph into groups of highly interconnected cells. These groups are the resulting clusters.

- Resolution Parameter: The

resolutionparameter controls the granularity of the clustering. A lower resolution (e.g., 0.2-0.8) yields fewer, broader clusters, while a higher resolution (e.g., 0.8-1.5) yields more, finer clusters. This should be tuned based on the biology of the system.

Cluster Annotation and the Average Overlap Metric

After clustering, the final and most critical step is to assign biological identities to the clusters. This is typically done by identifying marker genes for each cluster—genes that are statistically over-expressed in one cluster compared to all others.

Table 2: Marker Gene Identification and Annotation Methods

| Method | Principle | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Expression Testing | Statistical tests (e.g., Wilcoxon rank-sum test) to find genes enriched in each cluster. | Standard, first-pass annotation; works well for broad cell types. |

| Reference-Based Annotation | Compare cluster gene expression profiles to curated reference datasets (e.g., Celldex, SingleR). | Rapid, automated annotation; useful for well-characterized systems (e.g., human, mouse). |

| Average Overlap Metric (AOM) | Compares ranked lists of marker genes in a top-weighted manner to define distances between clusters [26]. | Refining annotation for highly similar populations; resolving subtle heterogeneity. |

Annotation Protocol:

- Find Marker Genes: For each cluster, perform differential expression analysis against all other cells to generate a ranked list of marker genes.

- Initial Annotation: Use the top marker genes to query cell type-specific databases (e.g., PanglaoDB, CellMarker) and published literature for known cell types.

- Refine with Average Overlap (AOM): A single clustering resolution may not perfectly capture all biological populations. The AOM provides a quantitative measure of cluster similarity based on their marker gene rankings [26]. Calculate the AOM between neighboring clusters. A high AOM suggests the clusters are highly similar and might represent a single, coherent cell type or a subtle substate. This can guide decisions on whether to merge clusters or re-cluster at a different resolution. This approach has been shown to enable "robust, reproducible characterization... in highly homogeneous populations," such as T-cell development stages [26].

The following diagram illustrates this iterative annotation process.

Diagram 3: Cluster Annotation and Refinement. This workflow outlines the process of annotating clusters based on marker genes and using the Average Overlap Metric (AOM) to decide whether to merge similar clusters for a final, biologically meaningful annotation.

Downstream Analysis and Advanced Applications

With annotated cell types, researchers can proceed to high-level biological interpretation. Key downstream analyses include:

- Differential Expression Analysis: Comparing gene expression between specific cell types across conditions (e.g., healthy vs. diseased).

- Trajectory Inference: Modeling dynamic processes like differentiation by ordering cells along a pseudotemporal path.

- Cell-Cell Communication: Predicting interactions between different cell types based on ligand-receptor expression.

These analyses, built upon a robust foundation of clustering and annotation, can uncover novel biology, identify therapeutic targets, and characterize disease mechanisms, ultimately advancing drug discovery and personalized medicine [27].

Advanced Analytical Techniques: Machine Learning and Applications in Drug Discovery

Leveraging Machine Learning for Dimensionality Reduction and Trajectory Inference

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the decoding of gene expression profiles at the level of individual cells, thereby revealing cellular heterogeneity and complex biological processes that are masked in bulk sequencing approaches [31] [32]. However, the high-dimensionality and inherent sparsity of scRNA-seq data—where each cell is represented by expressions of thousands of genes—present significant computational challenges for analysis and interpretation [33]. Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a core computational framework to address these challenges, providing powerful tools for extracting biologically meaningful insights from complex single-cell transcriptomics data [31].

Two of the most critical applications of ML in scRNA-seq analysis are dimensionality reduction and trajectory inference. Dimensionality reduction techniques transform high-dimensional gene expression data into lower-dimensional spaces, preserving essential biological information while facilitating visualization and downstream analysis [33]. Trajectory inference methods order cells along pseudotemporal trajectories to reconstruct dynamic biological processes such as development, differentiation, and disease progression from snapshot data [34]. The integration of these ML-driven approaches has become fundamental to unlocking the potential of scRNA-seq across diverse research domains, from fundamental biology to precision medicine and drug discovery [31] [35].

This application note provides a comprehensive overview of current ML methodologies for dimensionality reduction and trajectory inference in scRNA-seq analysis. We present structured comparisons of algorithmic performance, detailed experimental protocols for implementation, visualization of key analytical workflows, and a curated toolkit of research reagents and computational solutions. The content is framed within the broader context of advancing single-cell data analysis research, with particular emphasis on practical implementation for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Machine Learning for Dimensionality Reduction in scRNA-seq Data

Dimensionality reduction serves as an essential preprocessing step in scRNA-seq analysis pipelines, condensing thousands of gene dimensions into a manageable set of latent features that capture the primary sources of biological variation [33]. Both classical linear methods and advanced non-linear ML approaches have been adapted or developed specifically to address the statistical characteristics of single-cell data, including high dimensionality, sparsity, over-dispersion, and excessive zero counts (dropout events) [11].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) represents the most widely used linear dimensionality reduction technique. PCA performs an orthogonal linear transformation of the original gene expression space to create new uncorrelated variables (principal components) that capture decreasing proportions of the total variance [33]. However, standard PCA applied to transformed count data can induce spurious heterogeneity and mask true biological variability [11]. Model-based alternatives such as GLM-PCA and scGBM (single-cell Poisson bilinear model) directly model count distributions to avoid transformation artifacts and better capture biological signal [11].

Non-linear dimensionality reduction methods have gained prominence for their ability to capture complex manifolds and biological relationships. t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) minimizes the Kullback-Leibler divergence between probability distributions in high and low dimensions, emphasizing the preservation of local neighborhood structures [31] [36]. Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP) applies cross-entropy loss to balance both local and global structure preservation, offering improved computational efficiency and global coherence compared to t-SNE [31] [36]. More recently, Pairwise Controlled Manifold Approximation (PaCMAP) and TRIMAP have incorporated additional distance-based constraints to enhance preservation of both local detail and long-range relationships [36].

Deep learning architectures, particularly autoencoders (AEs) and variational autoencoders (VAEs), provide highly flexible frameworks for non-linear dimensionality reduction. These neural network models learn to compress data through an encoder network to a low-dimensional latent space, then reconstruct the input through a decoder network [37] [35]. The boosting autoencoder (BAE) represents a recent innovation that combines the advantages of unsupervised deep learning with boosting for formalizing structural assumptions, enabling the identification of small gene sets that explain latent dimensions [37].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Dimensionality Reduction Methods for scRNA-seq Data

| Method | Category | Key Algorithmic Features | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCA | Linear | Orthogonal linear transformation, variance maximization | Computationally efficient, interpretable components | May miss non-linear relationships, sensitive to data transformation |

| scGBM | Model-based | Poisson bilinear model, iteratively reweighted SVD | Directly models counts, quantifies uncertainty, scales to millions of cells | Complex implementation, longer runtime than PCA [11] |

| t-SNE | Non-linear | Kullback-Leibler divergence minimization, focus on local structure | Excellent visualization of local clusters, captures fine-grained patterns | Computational intensity, loss of global structure, stochastic results [36] |

| UMAP | Non-linear | Cross-entropy optimization, Riemannian geometry | Preservation of global structure, faster than t-SNE | Parameter sensitivity, potential artifactual connections [36] |

| PaCMAP | Non-linear | Pairwise distance preservation with three neighborhood types | Balanced local/global preservation, robust performance | Less established in biological domains [36] |

| Autoencoder | Deep Learning | Neural network encoder-decoder architecture, reconstruction loss | Flexibility to capture complex patterns, customizable architectures | Black box nature, computational demands, requires large data [37] |

| BAE | Deep Learning | Componentwise boosting encoder, structural constraints | Identifies sparse gene sets, incorporates biological assumptions | Complex implementation, specialized use cases [37] |

Recent benchmarking studies evaluating dimensionality reduction methods on drug-induced transcriptomic data from the Connectivity Map (CMap) dataset have provided empirical performance comparisons across multiple experimental conditions [36]. The study evaluated 30 different DR methods using internal cluster validation metrics (Davies-Bouldin Index, Silhouette score, Variance Ratio Criterion) and external validation metrics (Normalized Mutual Information, Adjusted Rand Index) to assess their ability to preserve biological structures.

Table 2: Benchmarking Performance of Top Dimensionality Reduction Methods on Drug Response Data [36]

| Method | Internal Validation (DBI) | Internal Validation (Silhouette) | External Validation (NMI) | Dose-Response Sensitivity | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t-SNE | High | High | High | Strong | Moderate |

| UMAP | High | High | High | Moderate | High |

| PaCMAP | High | High | High | Moderate | High |

| TRIMAP | High | High | High | Low | High |

| PHATE | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Low |

| Spectral | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Strong | Low |

| PCA | Low | Low | Low | Low | High |

The benchmarking results demonstrated that PaCMAP, TRIMAP, t-SNE, and UMAP consistently ranked among the top performers across multiple datasets and evaluation metrics, particularly excelling in separating distinct cell types and grouping drugs with similar molecular targets [36]. However, most methods struggled with detecting subtle dose-dependent transcriptomic changes, where Spectral, PHATE, and t-SNE showed relatively stronger performance [36]. These findings highlight the importance of method selection based on specific analytical goals and data characteristics.

Experimental Protocol: Dimensionality Reduction with scGBM

Principle: The scGBM (single-cell generalized bilinear model) approach performs dimensionality reduction by directly modeling UMI count data using a Poisson bilinear model, avoiding transformation-induced artifacts and providing uncertainty quantification for downstream analyses [11].

Materials and Reagents:

- Computational Environment: R (version 4.1.0 or higher) or Python (version 3.8 or higher)

- Required Packages: scGBM R package (https://github.com/phillipnicol/scGBM) or equivalent implementation

- Hardware Recommendations: Minimum 8GB RAM for datasets <10,000 cells; 16GB+ RAM for larger datasets

- Input Data: Raw UMI count matrix (cells × genes) in sparse matrix format

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Load the UMI count matrix, ensuring genes are in rows and cells in columns

- Filter low-quality cells based on mitochondrial percentage, total UMI counts, and detected gene counts

- Remove genes expressed in fewer than 10 cells to reduce noise

Model Initialization:

Parameter Estimation:

- Execute the iteratively reweighted singular value decomposition algorithm

- Monitor convergence via the Poisson deviance (typically requires 20-50 iterations)

- Extract the low-dimensional embedding (factor scores) and factor loadings

Uncertainty Quantification:

- Compute posterior uncertainties for each cell's latent position

- Calculate Cluster Cohesion Index (CCI) to assess confidence in cluster assignments

Downstream Analysis:

- Use the latent factors as input for clustering algorithms or visualization methods

- Identify genes associated with each factor through the loading matrix

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For convergence issues, reduce learning rate or increase number of iterations

- For memory limitations with large datasets, utilize the projection-based approximation

- Interpret factors by examining high-weight genes in the loading matrix

Experimental Protocol: Boosting Autoencoder for Interpretable Dimensionality Reduction

Principle: The Boosting Autoencoder (BAE) combines deep learning-based dimensionality reduction with componentwise boosting to incorporate structural assumptions and identify sparse sets of genes that characterize each latent dimension [37].

Materials and Reagents:

- Computational Environment: Python 3.7+ with PyTorch or TensorFlow

- Implementation: BAE code (https://github.com/NiklasBrunn/BoostingAutoencoder)

- Input Data: Normalized gene expression matrix (cells × genes)

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Normalize gene expression counts using standard scRNA-seq preprocessing

- Select highly variable genes (typically 2,000-5,000 genes) to reduce computational burden

Model Configuration:

- Define encoder architecture as a linear transformation with boosting constraints

- Design decoder as a neural network with multiple hidden layers

- Specify structural constraints (disentanglement or temporal coupling) based on experimental design

Model Training:

Interpretation and Analysis:

- Extract sparse weight matrix from the boosting encoder

- Identify genes associated with each latent dimension through non-zero weights

- Project cells into latent space for visualization and clustering

Validation:

- Compare clustering results with known cell type markers

- Assess biological relevance of identified gene sets through enrichment analysis

Applications:

- Disentanglement Constraint: Identification of distinct cell types and corresponding marker genes

- Temporal Coupling: Analysis of developmental processes with time-series data

Machine Learning for Trajectory Inference in scRNA-seq Data

Trajectory inference (TI) methods aim to reconstruct dynamic biological processes by ordering cells along pseudotemporal trajectories based on gene expression similarity, enabling the study of cellular differentiation, development, and disease progression from snapshot scRNA-seq data [34]. While early TI methods treated pseudotime as a descriptive concept based on expression distance metrics, recent advances have focused on developing more principled model-based approaches with biophysical interpretations [34].

The evolution of TI methodologies has progressed from graph-based approaches that construct minimum spanning trees or principal graphs through expression space, to RNA velocity-based methods that leverage unspliced/spliced mRNA ratios to predict future cell states, and more recently to process time models that infer latent variables corresponding to the timing of cells subject to specific biophysical processes [34].

The Chronocell model represents a significant advancement in this evolution by formulating trajectories through a biophysical framework of cell state transitions [34]. Unlike descriptive pseudotime, Chronocell infers "process time" as a latent variable with intrinsic physical meaning relative to a specific cellular process. The model is identifiable, making parameter inference meaningful, and can interpolate between trajectory inference (for continuous cell states) and clustering (for discrete states) based on data characteristics [34].

Key innovations in modern TI methods include:

- Biophysical Meaning: Parameters such as degradation rates and transition probabilities have direct biological interpretations

- Model Identifiability: Ensuring that inferred parameters correspond to unique solutions

- Model Assessment: Quantitative frameworks for determining whether data support continuous trajectory or discrete cluster models

- Integration with RNA Velocity: Combining snapshot data with kinetic models of RNA splicing

Table 3: Comparison of Trajectory Inference Methodologies

| Method Category | Representative Algorithms | Underlying Principle | Interpretation of Time | Key Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graph-Based | Monocle, Slingshot | Minimum spanning trees through expression space | Descriptive pseudotime based on expression distance | Continuous biological process exists in data |

| RNA Velocity | scVelo, Velocyto | Kinetic modeling of unspliced/spliced mRNA ratios | Directional flow based on RNA metabolism | Splicing kinetics are consistent across cells |

| Process Models | Chronocell, VeloCycle | Biophysical models of cell state transitions | Process time with physical interpretation | Cells share common dynamic process |

Experimental Protocol: Trajectory Inference with Chronocell

Principle: Chronocell implements a process time model that formulates trajectories through biophysical modeling of cell state transitions, inferring latent variables corresponding to the timing of cells subject to a specific cellular process [34].

Materials and Reagents:

- Computational Environment: MATLAB or Python with specialized Chronocell implementation

- Software Availability: https://github.com/pachterlab/FGP_2024

- Input Data: Processed scRNA-seq count matrix with preliminary cell type annotations

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Perform standard scRNA-seq preprocessing (normalization, highly variable gene selection)

- Compute preliminary dimensionality reduction (PCA) and clustering

- Annotate broad cell states based on marker genes

Model Initialization:

- Specify the number of cell states and possible transitions

- Initialize process time parameters based on prior knowledge or heuristic ordering

Parameter Estimation:

Model Selection and Assessment:

- Compare trajectory model against cluster models using likelihood ratio tests

- Assess model fit through residual analysis and posterior predictive checks

- Validate process time ordering using known marker gene dynamics

Interpretation and Visualization:

- Extract process time estimates for each cell

- Plot gene expression dynamics along process time

- Identify transition points between cell states

Validation and Troubleshooting:

- Ground Truth Validation: Compare with time-series data where available

- Sensitivity Analysis: Assess robustness to parameter initialization

- Model Adequacy Checking: Verify that continuous trajectory model is more appropriate than discrete clusters for the data

- Circularity Avoidance: Ensure that the same data is not used for both trajectory inference and differential expression testing without proper cross-validation

Specialized Protocol: Trajectory Inference with Compositional Data Analysis

Principle: Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) provides an alternative statistical framework for trajectory inference by treating scRNA-seq data as compositions of log-ratios between components, which can improve robustness to dropout events and other technical artifacts [38].

Materials and Reagents:

- R Package: CoDAhd (https://github.com/GO3295/CoDAhd)

- Input Data: Raw UMI count matrix

Procedure:

- Count Addition:

- Apply specific count addition schemes (e.g., SGM) to handle zero values

- Convert raw counts to compositions

Log-Ratio Transformation:

- Compute centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation

- Alternative: Use other log-ratio transformations (ALR, ILR) based on data characteristics

Trajectory Analysis:

- Apply trajectory inference algorithms (e.g., Slingshot) to CLR-transformed data

- Compare results with conventional normalization approaches

Applications: Particularly valuable for datasets with high dropout rates or when conventional methods produce biologically implausible trajectories.

Integrated Workflow and Visualization

The analytical workflow for scRNA-seq analysis typically follows a sequential pipeline where dimensionality reduction precedes trajectory inference, with each step informing subsequent analyses. The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow and the key decision points:

Diagram 1: Integrated Workflow for Dimensionality Reduction and Trajectory Inference. The diagram illustrates the sequential analytical steps in scRNA-seq analysis, with key decision points for method selection based on data characteristics and research objectives.

The relationship between different dimensionality reduction methods and their performance characteristics can be visualized through the following comparative framework:

Diagram 2: Method Characteristics Across Dimensionality Reduction Approaches. The diagram compares key performance characteristics across major categories of dimensionality reduction methods, highlighting trade-offs and complementary strengths.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Dimensionality Reduction and Trajectory Inference

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function | Implementation | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scGBM | Dimensionality Reduction | Model-based dimensionality reduction | R package | Direct count modeling, uncertainty quantification, scalability to millions of cells [11] |

| Boosting Autoencoder (BAE) | Dimensionality Reduction | Interpretable deep learning dimensionality reduction | Python/PyTorch | Sparse gene sets, structural constraints, disentangled dimensions [37] |

| Chronocell | Trajectory Inference | Process time modeling | MATLAB/Python | Biophysical interpretation, model identifiability, trajectory/clustering interpolation [34] |

| CoDAhd | Data Transformation | Compositional data analysis for scRNA-seq | R package | Centered log-ratio transformation, dropout robustness, improved trajectory inference [38] |

| scVelo | Trajectory Inference | RNA velocity analysis | Python | Kinetic modeling, dynamical inference, gene-shared time [34] |

| Slingshot | Trajectory Inference | Graph-based trajectory inference | R package | Minimum spanning trees, simultaneous lineage identification [38] |

Table 5: Experimental Design Considerations for Method Selection

| Research Scenario | Recommended Dimensionality Reduction | Recommended Trajectory Inference | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard cell type identification | PCA or scGBM | Graph-based (Slingshot) | Computational efficiency, established benchmarks |

| Rare cell population detection | scGBM or BAE | Process time (Chronocell) | Enhanced sensitivity to small cell groups, uncertainty quantification |

| High dropout rate datasets | scGBM or CoDA-transformed PCA | CoDA-enhanced trajectory inference | Robustness to technical zeros, compositionally aware |

| Biophysical parameter estimation | Model-based (scGBM) | Process time (Chronocell) | Parameter interpretability, kinetic modeling |

| Developmental time series | BAE with temporal constraints | RNA velocity or process time | Temporal structure incorporation, directional information |

| Large-scale datasets (>1M cells) | scGBM or UMAP | Graph-based methods | Computational scalability, efficient neighbor detection |

Machine learning approaches for dimensionality reduction and trajectory inference have fundamentally transformed the analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data, enabling researchers to extract profound biological insights from increasingly complex and large-scale datasets. The field has evolved from purely descriptive visualizations and orderings to principled model-based approaches that incorporate biophysical meaning and uncertainty quantification.

The current landscape offers a diverse toolkit of methods, each with distinct strengths and optimal application domains. For dimensionality reduction, researchers can select from computationally efficient linear methods (PCA), count-aware model-based approaches (scGBM), visualization-optimized non-linear techniques (UMAP, t-SNE), or interpretable deep learning architectures (BAE) based on their specific analytical needs. Similarly, trajectory inference has progressed from graph-based pseudotime orderings to biophysically grounded process time models (Chronocell) that provide meaningful parameter estimates and rigorous model assessment.

Future directions in this rapidly advancing field will likely focus on several key areas: (1) enhanced integration of multi-omics data types within unified dimensionality reduction frameworks; (2) development of increasingly interpretable and biologically constrained models; (3) improved scalability to accommodate the growing size of single-cell datasets; and (4) tighter coupling between experimental design and computational analysis to ensure biological validity. As these methodologies continue to mature, they will further empower researchers to unravel the complexities of cellular systems, accelerating discoveries in basic biology, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic development.

By providing structured comparisons, detailed protocols, and practical implementation guidelines, this application note serves as a comprehensive resource for researchers navigating the evolving landscape of machine learning approaches for single-cell RNA sequencing analysis. The integration of these computational methodologies with experimental single-cell technologies will continue to drive innovations in precision medicine and therapeutic development.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biomedical research by enabling the investigation of transcriptional profiles at the individual cell level, moving beyond the limitations of bulk RNA sequencing which masks cellular heterogeneity [39]. Since its inception in 2009, scRNA-seq has evolved into a powerful tool that captures the diversity within tissues, organs, and individuals, generating millions to billions of datapoints per experiment [40] [39]. In the high-stakes field of drug discovery, where development takes approximately 10-15 years and costs between $900 million to over $2 billion per drug, scRNA-seq offers unprecedented resolution to dissect cellular mechanisms and streamline development [40]. This technology provides nuanced insights into drug targets, biomarkers, and patient responses, potentially reducing the staggering attrition rates in clinical trials by identifying pharmacokinetic and toxicity issues earlier in the process [40]. This Application Note details standardized protocols and applications for integrating scRNA-seq throughout the drug discovery pipeline, from initial target identification to clinical biomarker development, providing researchers with practical methodologies to leverage this transformative technology.

scRNA-seq in Target Identification and Validation

Target identification and validation represent the foundational stage of drug discovery, and scRNA-seq significantly enhances this process by revealing cell-type-specific gene expression patterns in disease-relevant tissues. A 2024 retrospective analysis from the Wellcome Institute demonstrated that drug targets with cell-type-specific expression in disease-relevant tissues are robust predictors of clinical trial progression from Phase I to Phase II [40]. By analyzing 30 diseases and 13 tissues, researchers established scRNA-seq as a predictive tool for prioritizing targets with higher success potential.

Experimental Protocol: Target Discovery Using scRNA-seq

Sample Preparation and Single-Cell Isolation

- Tissue Dissociation: Mechanically and enzymatically dissociate fresh tissue samples (e.g., tumor biopsies) to create single-cell suspensions. For challenging samples or frozen tissues, single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) provides a viable alternative [39].