A Practical Framework for Validating Computational Biology Models: From Benchmarks to Clinical Impact

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals tasked with validating computational biology models.

A Practical Framework for Validating Computational Biology Models: From Benchmarks to Clinical Impact

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals tasked with validating computational biology models. It explores the foundational principles of model validation, details current methodological applications across drug discovery and precision medicine, addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes a framework for rigorous comparative analysis through standardized benchmarking. By synthesizing the latest advancements and best practices, this guide aims to enhance the reliability, reproducibility, and clinical translatability of computational models in biomedical research.

Core Principles and the Critical Need for Validation in Computational Biology

Validation represents the cornerstone of reliable computational biology, serving as the critical bridge between theoretical models and real-world biological applications. In essence, validation encompasses the comprehensive process of assessing how well computational methods perform their intended tasks against established standards or experimental data. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, rigorous validation separates clinically actionable insights from mere computational artifacts.

The field faces significant challenges in establishing universal validation standards. As noted in chromatin structure modeling research, method validation is complicated by "different aspects of chromatin biophysics and scales," the "large diversity of experimental data," and the need for "expertise in biology, bioinformatics, and physics" to conduct comprehensive assessments [1]. These challenges are further compounded by the rapid emergence of artificial intelligence tools, which require novel validation frameworks distinct from traditional software.

This guide examines the current landscape of computational validation, with particular emphasis on objective performance comparisons between emerging AI tools and established methods. By defining standardized evaluation protocols and metrics, we aim to provide researchers with a structured approach to assessing computational tools for biological discovery and therapeutic development.

Comparative Performance Analysis of AI Tools in Biological Applications

The integration of large language models (LLMs) into computational biology workflows has created an urgent need for systematic performance validation. Recent studies have conducted head-to-head comparisons of leading AI models across biological domains, with revealing results about their respective strengths and limitations.

Performance in Medical Knowledge Applications

A rigorous 2025 study compared ChatGPT-3.5, Gemini 2.0, and DeepSeek V3 on pediatric pneumonia knowledge using a 27-question assessment framework evaluated by infectious disease specialists. The models were assessed on accuracy (6-point scale), completeness (3-point scale), and safety (binary score), yielding a maximum total score of 10 points per question [2].

Table 1: Medical Knowledge Assessment Results (Pediatric Pneumonia)

| Model | Mean Total Score | Accuracy Score | Completeness Score | Safety Score | Top-Scoring Questions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSeek V3 | 9.9/10 | 5.9/6 | 3/3 | 1/1 | 26/27 (96.3%) |

| ChatGPT-3.5 | 7.7/10 | 4.7/6 | 2.7/3 | 0.96/1 | 2/27 (7.4%)* |

| Gemini 2.0 | 7.5/10 | 4.7/6 | 2.7/3 | 1/1 | 1/27 (3.7%)* |

*Shared top positions with other models in some questions

DeepSeek V3 demonstrated particularly strong performance in higher-order reasoning domains, outperforming other models by up to 3.2 points in areas such as "Etiology and Age-Specific Pathogens" and "Diagnostics and Imaging" [2]. All models maintained strong safety profiles, with only one response from ChatGPT-3.5 flagged as potentially clinically unsafe.

Performance in Scientific Computing Tasks

In scientific computing applications, particularly for solving partial differential equations (PDEs), a February 2025 study revealed different performance patterns. Researchers evaluated reasoning-optimized versions (ChatGPT o3-mini-high and DeepSeek R1) alongside general-purpose models on traditional numerical methods and scientific machine learning tasks [3].

Table 2: Scientific Computing Performance Assessment

| Task Category | DeepSeek V3 | DeepSeek R1 | ChatGPT 4o | ChatGPT o3-mini-high |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stiff ODE Solving | Moderate | High | Moderate | Highest |

| Finite Difference Methods | Moderate | High | High | Highest |

| Finite Element Methods | Moderate | Moderate | High | Highest |

| Physics-Informed Neural Networks | Moderate | High | High | Highest |

| Neural Operator Learning | Moderate | High | Moderate | Highest |

The study found that ChatGPT o3-mini-high "usually delivers the most accurate results while also responding significantly faster than its reasoning counterpart, DeepSeek R1," making it particularly suitable for iterative computational tasks requiring both precision and efficiency [3].

Community-Driven Benchmarking Frameworks for Biological AI

Beyond individual model performance, the computational biology community has recognized the need for standardized benchmarking ecosystems to enable reproducible and comparable validation across methods and laboratories.

The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative Benchmarking Suite

In October 2025, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) released a community-driven benchmarking suite to address the "major technical and systemic bottleneck: the lack of trustworthy, reproducible benchmarks to evaluate biomodel performance" [4]. This initiative emerged from collaboration with machine learning and computational biology experts across 42 institutions who identified key shortcomings in current validation approaches, including irreproducible results, bespoke benchmarks for individual publications, and overfitting to static benchmarks.

The CZI platform provides multiple access points tailored to different expertise levels:

- Command-line tools for reproducible benchmarking

- Python packages (cz-benchmarks) for embedded evaluations during training

- No-code web interfaces for non-computational researchers

The initial release includes six standardized tasks for single-cell analysis: cell clustering, cell type classification, cross-species integration, perturbation expression prediction, sequential ordering assessment, and cross-species disease label transfer [4]. Each task incorporates multiple metrics to provide a comprehensive performance view, addressing the limitation of single-metric evaluations that can obscure important performance dimensions.

Specialized Benchmarking in Expression Forecasting

In gene expression forecasting, researchers have developed PEREGGRN (PErturbation Response Evaluation via a Grammar of Gene Regulatory Networks), a specialized benchmarking platform that combines 11 large-scale perturbation datasets with evaluation software [5]. This system addresses a critical gap in expression forecasting validation by implementing non-standard data splits where "no perturbation condition is allowed to occur in both the training and the test set," better simulating real-world prediction scenarios.

The platform employs multiple evaluation metrics categorized into:

- Standard performance metrics: Mean absolute error (MAE), mean squared error (MSE), Spearman correlation

- Differential expression focus: Performance on top 100 most differentially expressed genes

- Biological relevance: Accuracy in cell type classification following perturbations

This multi-metric approach acknowledges that "there is no consensus about what type of metric to use for evaluating and interpreting perturbation predictions" and provides a more nuanced validation framework [5].

Experimental Protocols for Computational Method Validation

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for meaningful comparison between computational methods. This section outlines key methodological considerations derived from recent benchmarking initiatives.

Workflow for Benchmarking Computational Methods

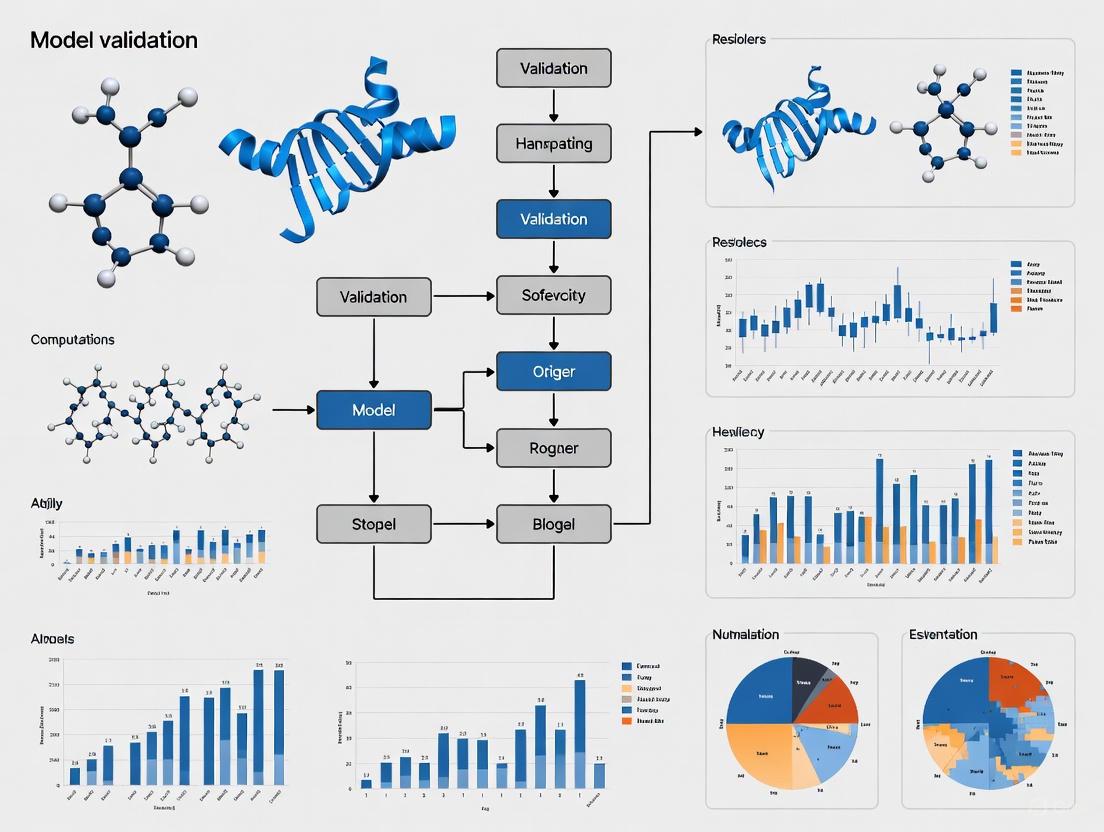

The following diagram illustrates the generalized validation workflow adopted by community benchmarking efforts:

Key Methodological Considerations

Data Splitting Strategies

For perturbation prediction tasks, PEREGGRN implements a critical validation protocol where "no perturbation condition is allowed to occur in both the training and the test set" [5]. This approach ensures models are evaluated on truly novel interventions rather than minor variations of training examples. Randomly selected perturbation conditions and controls are allocated to training data, while distinct perturbation conditions are reserved for testing.

Ground Truth Establishment

In chromatin modeling, researchers have utilized distance matrices derived from experimental techniques like Hi-C, ChIA-PET, and Micro-C XL to represent ground truth structures [1]. Spearman correlation coefficients between model outputs and experimental data provide quantitative validation metrics, though challenges remain due to the "population and cell cycle averaging inherent in many of these datasets" [1].

Metric Selection and Interpretation

Multi-metric assessment is essential for comprehensive validation. As demonstrated in expression forecasting, different metrics can "give substantially different conclusions empirically" [5]. Validation protocols should therefore incorporate metrics spanning:

- Accuracy measures: MSE, MAE, correlation coefficients

- Rank-based measures: Top-k accuracy, Spearman correlation

- Biological relevance: Functional enrichment, phenotype prediction accuracy

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The following table details key resources and their functions in computational method validation:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Validation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmarking Platforms | CZI Benchmarking Suite, PEREGGRN | Standardized evaluation ecosystems | Community-driven, multiple metrics, reproducible environments |

| Experimental Data | Hi-C, Micro-C XL, Perturb-seq datasets | Ground truth establishment | Population/single-cell resolution, protein-specific interactions |

| Workflow Systems | Common Workflow Language (CWL) | Method execution standardization | Portable across computing environments, provenance tracking |

| Performance Metrics | Spearman correlation, MSE, classification accuracy | Quantitative performance assessment | Multiple complementary measures, biological interpretation |

| AI Models | DeepSeek V3/R1, ChatGPT variants | Method comparison benchmarks | Specialized capabilities (reasoning, coding, biological knowledge) |

The validation of computational biology methods has evolved from simple accuracy assessments to sophisticated, multi-dimensional evaluations incorporating diverse metrics, experimental data types, and real-world performance measures. Community-driven initiatives like the CZI benchmarking suite and PEREGGRN represent significant advances toward standardized validation ecosystems that can keep pace with rapidly evolving computational methods.

For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting appropriate validation strategies requires careful consideration of task-specific requirements, available experimental data, and relevant performance metrics. The comparative performance data presented in this guide provides initial guidance for tool selection, but optimal choices will depend on specific application contexts.

As the field progresses, the integration of more sophisticated validation frameworks—including continuous benchmarking, real-world performance monitoring, and community-wide standardization efforts—will be essential for translating computational advances into biological insights and therapeutic breakthroughs.

The paradigm of drug development is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the integration of computational biology models and artificial intelligence approaches. These technologies represent a fundamental shift from traditional, resource-intensive methods toward data-driven, in silico methodologies that promise to accelerate timelines, reduce costs, and enhance patient safety [6] [7]. The stakes for their rigorous validation are exceptionally high, as these models are increasingly deployed for critical decisions in target identification, lead optimization, and clinical trial design, directly impacting therapeutic efficacy and safety outcomes [8] [9]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of leading computational tools and methodologies, evaluating their performance, validation frameworks, and applicability across the drug development pipeline. By objectively assessing these alternatives against experimental data and established validation protocols, we aim to equip researchers with the evidence needed to navigate this rapidly evolving landscape and implement computational strategies that uphold the highest standards of scientific rigor and patient safety.

Comparative Analysis of Computational Approaches

Performance Benchmarking of Key Technologies

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Computational Drug Discovery Tools

| Technology Category | Representative Tools | Primary Applications | Reported Performance Metrics | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Docking | AutoDock Vina, GOLD, GLIDE, DOCK [10] | Virtual screening, binding pose prediction, lead optimization | Varies by tool/target; Success rates in pose prediction (60-80% for high-resolution structures) [10] | High throughput, well-established, user-friendly | Limited by rigid receptor assumption, scoring function inaccuracies |

| AI-Enhanced Screening | Alpha-Pharm3D [11] | Bioactivity prediction, virtual screening, scaffold hopping | AUROC ~90% on diverse datasets; >25% mean recall rate in screening [11] | High accuracy, interpretable PH4 fingerprints, handles data scarcity | Complex training pipeline, requires 3D structural information |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD [7] | Mechanism studies, binding/unbinding kinetics, conformational changes | Provides atomic-level insights; Computationally expensive (ns-μs timescales) [7] | High-resolution temporal data, captures flexibility | Extreme computational cost, limited timescales |

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) | DFT, ab initio methods [7] | Electronic interactions, reaction mechanisms, accurate binding energy calculation | High accuracy for small systems; Prohibitive cost for large biomolecules [7] | High accuracy for electronic properties | Extremely computationally expensive, limited system size |

| Machine Learning (ML) | Various classifiers, regression models [12] [9] | Risk prediction, disease diagnosis, bioactivity modeling | SWSELM for sepsis: AUC 0.9387 [12]; Diagnostic AI: variable vs. human experts [9] | Handles complex, high-dimensional data, continuous learning | "Black box" opacity, performance bias on rare variants [9] |

Validation Frameworks and Regulatory Alignment

The credibility of computational models hinges on robust validation frameworks and their alignment with evolving regulatory standards. The computational model lifecycle conceptualizes the journey from academic research to clinical application, emphasizing that different validation standards apply at each stage [8]. For models intended to support regulatory decisions, the FDA's Predictive Toxicology Roadmap and ISTAND program provide pathways for qualifying novel methodologies, demonstrating a shift toward accepting well-validated non-animal approaches [6]. The European Health Data Space and Virtual Human Twins Initiative represent parallel efforts in the EU to foster development and application of computational medicine [8].

Key validation challenges include:

- Technical Validation: Assessing a model's predictive accuracy against independent test sets and experimental data [6] [11].

- Credibility Assessment: Establishing model reliability through verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification [8].

- Regulatory Validation: Demonstrating that a model is fit-for-purpose for specific regulatory contexts [6] [8].

- Clinical Validation: Proving that model predictions translate to improved patient outcomes in real-world settings [12] [9].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Standardized Workflows for Benchmarking Studies

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols for Computational Model Validation

| Protocol Category | Core Methodology | Key Metrics Measured | Data Requirements | Reference Standards |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virtual Screening Validation | Retrospective screening against known actives/decoys; Comparison of enrichment early in recovery curve [11] | AUC-ROC, EF (Enrichment Factor), recall rate | Known active compounds, chemically matched decoys, target structure | DUD-E database, ChEMBL bioactivity data [11] |

| Binding Pose Prediction | Computational docking against crystal structures; Comparison with experimental poses [10] | RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) of heavy atoms, success rate within 2Å | High-resolution protein-ligand crystal structures | Protein Data Bank (PDB) complexes [10] |

| Bioactivity Prediction | Train/test split on bioactivity data; External validation on unseen compounds [11] | AUC-ROC, AUC-PR, Pearson R² for continuous values | Curated bioactivity data (Ki, IC50, EC50) | ChEMBL database, functional assay data [11] |

| Clinical Outcome Prediction | Retrospective cohort analysis; Temporal validation (training on earlier data) [12] | AUC, sensitivity, specificity, calibration metrics | Electronic health records, standardized clinical endpoints | Sepsis mortality data [12], rare disease registries [9] |

Case Study: Alpha-Pharm3D Validation Protocol

The validation of Alpha-Pharm3D exemplifies a comprehensive approach to benchmarking computational tools [11]. The protocol involves:

Data Curation and Cleaning:

- Collection of target-specific compound activity data from ChEMBL database (version CHEMBL34)

- Acquisition of high-resolution receptor-ligand complexes from DUD-E database and RCSB PDB

- Filtering out ions, cofactors, and solvent molecules, retaining only orthogonal-binding ligands and receptors

- Application to eight diverse targets including kinases (ABL1, CDK2), GPCRs (ADRB2, CCR5, CXCR4, NK1R), and proteases (BACE1)

Model Training and Evaluation:

- Generation of multiple 3D conformers using RDKit with MMFF94 force field optimization

- Explicit incorporation of geometric constraints from receptor binding pockets

- Rigorous benchmarking against state-of-the-art scoring methods

- Assessment of performance under data scarcity conditions

Experimental Validation:

- Prioritization of compounds for NK1R (neurokinin-1 receptor)

- Chemical optimization of lead compounds

- Functional testing yielding compounds with EC50 values of approximately 20 nM

This multi-faceted validation approach demonstrates how computational predictions can be bridged with experimental confirmation, establishing a framework for assessing real-world performance [11].

Visualization of Workflows and Methodologies

Computational Model Lifecycle

Diagram 1: Computational model lifecycle from conception to clinical application. This framework illustrates the stages of development and translation of in silico models, highlighting critical transition points requiring validation and regulatory alignment [8].

Integrated Drug Discovery Workflow

Diagram 2: Integrated drug discovery workflow showing the synergy between computational approaches and experimental validation across development stages [7] [10] [11].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Drug Discovery

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [10], RCSB [11] | Provides experimental protein structures for docking targets and validation | Source of high-resolution complexes for benchmarking pose prediction |

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL [11], PubChem [13] [10], BindingDB | Curated bioactivity data (IC50, Ki, EC50) for model training and testing | Gold standard data for validating bioactivity prediction models |

| Chemical Databases | ZINC [13] [10], DrugBank [10] | Libraries of purchasable compounds for virtual screening | Source of compound libraries for prospective validation studies |

| Software Tools | RDKit [11], AutoDock Suite [10], GROMACS [7] | Open-source toolkits for cheminformatics, docking, and simulation | Enable reproducible computational protocols and method benchmarking |

| Validation Platforms | DUD-E [11], DEKOIS | Benchmark sets for virtual screening (known actives + decoys) | Standardized datasets for calculating enrichment factors and AUC metrics |

| Clinical Data Repositories | EHR systems, rare disease registries [9] | Real-world patient data for clinical model development and validation | Enable temporal validation of clinical prediction models |

Implications for Patient Safety and Therapeutic Efficacy

The rigorous validation of computational models has direct implications for patient safety and therapeutic efficacy. Validated in silico approaches can identify toxicity and ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) issues earlier in the development process, potentially reducing late-stage failures attributed to safety concerns [13] [7]. For rare diseases, where traditional clinical trials are challenging, validated computational models enable the creation of virtual cohorts and synthetic control arms, potentially accelerating access to therapies while maintaining safety standards [9].

The integration of AI/ML in clinical prediction models, such as the SWSELM for sepsis mortality, demonstrates how validated computational approaches can directly impact patient care by enabling earlier intervention and personalized risk assessment [12]. However, these applications necessitate particularly rigorous validation due to their direct influence on clinical decision-making. The translation of computational models into clinical settings requires not only technical validation but also careful assessment of clinical utility and implementation feasibility within healthcare workflows [8] [12].

The validation of computational biology models represents a critical frontier in drug development, with profound implications for both efficiency and patient safety. As this comparison demonstrates, no single computational approach dominates across all applications; rather, the optimal methodology depends on the specific context of use, available data, and required level of precision. The increasing integration of AI and machine learning with physics-based simulations creates powerful hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both paradigms [8] [11].

The future of computational model validation lies in developing standardized benchmarking protocols, transparent reporting standards, and regulatory pathways that maintain scientific rigor while encouraging innovation. As these technologies continue to evolve, their validated integration into drug development pipelines promises to enhance predictive accuracy, reduce attrition rates, and ultimately deliver safer, more effective therapies to patients in need. The high stakes of this endeavor demand nothing less than the most rigorous, comprehensive, and critical approach to validation.

In computational biology, the concept of "hallucinations" manifests uniquely across different modeling paradigms, presenting significant challenges for research validation and drug development. In artificial intelligence systems, hallucinations refer to large language models (LLMs) generating "content that is nonsensical or unfaithful to the provided source content" or making fluent but arbitrary and incorrect claims [14]. Similarly, in biological modeling, we encounter analogous phenomena where experimental models—particularly animal models—produce misleading results that fail to accurately predict human biological responses [15] [16]. These parallel limitations across computational and biological domains represent critical bottlenecks in biomedical research, especially in complex fields like neuroscience and psychiatry where mechanisms of disease are often poorly understood [17] [16].

The validation of computational biology models requires careful navigation of these dual challenges: managing the reliability of AI-driven analysis while ensuring the biological models generating underlying data possess translational relevance. This comparison guide examines the fundamental limitations and detection methodologies across both domains, providing researchers with frameworks for critical evaluation of model outputs in their investigative workflows. By understanding these shared pitfalls, computational biologists can develop more robust validation strategies that account for limitations in both digital and biological modeling systems.

Quantitative Comparison of Hallucination Detection Methods

Performance Metrics Across Detection Approaches

Table 1: Comparative performance of hallucination detection methods for AI systems

| Detection Method | AUROC | Key Datasets Validated | Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semantic Entropy [14] | 0.71-0.90 | TriviaQA, SQuAD, BioASQ, NQ-Open | Computationally intensive; requires multiple samples | Short-form question answering |

| Semantic Entropy Probes (SEPs) [18] | ~0.71 | LongFact++ | Lower performance than sampling variant | Real-time applications |

| Linear Probes [18] | 0.87-0.90 | LongFact++ | Requires training data | Long-form generation |

| LoRA-Enhanced Probes [18] | 0.90 | LongFact++ | Modifies model behavior | High-stakes long-form tasks |

| External Verification (SAFE, FactScore) [18] | High (qualitative) | Various | High latency and cost | Post-hoc verification |

Comparative Limitations of Biological Model Systems

Table 2: Limitations of animal models in drug development and translational research

| Model System | Predictive Accuracy for Human Efficacy | Key Failure Points | Notable Examples | Alternative Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse Models (Neuropsychiatric) [16] | Low | Cannot recapitulate entire disorders; artificial conditions | Failed anti-β-amyloid trials for Alzheimer's | Human stem cell models |

| Mouse Models (Inflammatory) [16] | Low | Genetic/physiological differences | Human inflammatory conditions [16] | Human cell-based assays |

| Rat Models [15] | Moderate-low | Metabolic differences; species-specific sensitivities | High attrition in clinical phases | Organs-on-chips |

| Non-Human Primates [15] | Moderate-high | Costly; ethical concerns; still not perfect predictors | Limited use due to practicality | Advanced computer models |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Semantic Entropy Measurement in LLMs

The detection of confabulations—a subset of hallucinations where models generate arbitrary and incorrect content—can be achieved through semantic entropy measurement [14]. This method quantifies uncertainty at the level of meaning rather than specific word sequences:

Query Sampling: For each input query, generate multiple possible answers (typically 5-10 samples) using different random seeds to capture the distribution of possible model responses.

Semantic Clustering: Algorithmically cluster answers based on semantic equivalence using bidirectional entailment. Two sentences are considered semantically equivalent if each entails the other, determined using natural language inference tools or LLMs themselves [14].

Probability Calculation: Compute the probability of each semantic cluster by summing the probabilities of all answer variants within that cluster. The probability of individual sequences is calculated using the model's native token probabilities.

Entropy Computation: Calculate the semantic entropy using the standard entropy formula H = -ΣP(c)logP(c), where P(c) is the probability of semantic cluster c.

This method has demonstrated significant improvement over naive lexical entropy, particularly for free-form generation tasks where the same meaning can be expressed with different wording [14]. The approach works across various domains including biological question-answering (BioASQ) without requiring previous domain knowledge.

Protocol for Cross-Species Validation of Computational Psychiatry Findings

Research investigating neural circuit mechanisms of psychiatric symptoms requires careful cross-species validation [17]:

Task Design: Develop behavioral tasks with analogous components across species. For example, a perceptual detection task with confidence reporting can be implemented with humans providing verbal confidence reports and mice expressing confidence through time investment for rewards [17].

Computational Modeling: Apply identical computational algorithms to explain behavior across species. For hallucination-like perceptions, this might involve modeling how expectations influence perceptual decisions.

Correlational Validation in Humans: Establish correlations between task-based measures (e.g., hallucination-like percepts) and clinical symptoms (e.g., self-reported hallucination tendency) in human subjects.

Pharmacological Manipulation in Animals: Test whether task measures in animals are modulated by pharmacological interventions known to induce similar states in humans (e.g., ketamine for psychosis-like experiences).

Circuit Manipulation: Use advanced neuroscientific tools in animals (optogenetics, fiber photometry) to identify neural circuits underlying task performance and verify their relevance through causal manipulations.

This approach enables researchers to bridge the gap between subjective human experiences and measurable neural circuit functions in animal models, potentially overcoming historical limitations in psychiatric drug development [17].

Visualization of Key Methodologies

Semantic Entropy Measurement Workflow

Cross-Species Computational Psychiatry Approach

Table 3: Essential research reagents and resources for studying model limitations

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Relevance to Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hallucination Detection Datasets | TriviaQA [14], SQuAD [14], BioASQ [14], LongFact++ [18] | Benchmarking hallucination detection methods | Provide standardized evaluation across domains including biology |

| Biological Model Validation Tools | Organs-on-chips [19], Human stem cell-derived models [16] | Human-relevant physiological modeling | Address species-specific limitations of animal models |

| Computational Psychiatry Tasks | Perceptual decision tasks with confidence reporting [17] | Cross-species measurement of subjective experiences | Bridge human symptoms and animal circuit mechanisms |

| Uncertainty Quantification Methods | Semantic entropy [14], Linear probes [18] | Measure model confidence and detect unreliable outputs | Critical for assessing trustworthiness of computational predictions |

| Circuit Manipulation Tools | Optogenetics, Fiber photometry [17] | Causal testing of neural circuit hypotheses in animals | Validate computational model predictions about biological mechanisms |

Fundamental Limitations and Theoretical Constraints

The Impossibility of Perfect Hallucination Control

Recent theoretical work has established fundamental limitations in eliminating hallucinations from large language models. An impossibility theorem demonstrates that no LLM inference mechanism can simultaneously satisfy four essential properties: (1) truthful (non-hallucinatory) generation, (2) semantic information conservation, (3) relevant knowledge revelation, and (4) knowledge-constrained optimality [20]. This mathematical framework, modeled using auction theory where neural components compete to contribute knowledge, proves that hallucinations are not merely engineering challenges but inherent limitations of the inference process itself.

The implications for computational biology are significant: rather than seeking to completely eliminate hallucinations from AI systems used in research, we should develop frameworks that optimally manage the trade-offs based on application requirements. In safety-critical applications, truthfulness might be prioritized, while in creative hypothesis generation, more complete information utilization might be valued despite higher hallucination risks [20].

Fundamental Constraints in Biological Model Translation

Similarly, biological model systems face inherent limitations in predicting human outcomes. The "reproducibility crisis" in science partially stems from overreliance on animal models that cannot fully recapitulate human disease due to biological differences, artificial experimental conditions, and species-specific sensitivities [15] [19]. These limitations manifest in startling statistics: approximately 95% of drug candidates fail in clinical development stages, with 20-40% failing due to unexpected toxicity or lack of efficacy despite promising animal model results [15].

The parallel between AI hallucinations and biological model limitations is striking: both represent systematic failures where models generate plausible but inaccurate outputs—whether textual predictions or biological responses—that fail to align with ground truth human reality. Understanding these shared constraints enables researchers to appropriately weight evidence from different model systems and implement necessary validation checkpoints throughout the research pipeline.

The comparison of hallucinations and limitations across AI and biological modeling systems reveals shared challenges in model validation for computational biology. Effective research strategies must acknowledge both the theoretical constraints and practical limitations of each approach, implementing layered validation frameworks that compensate for individual system weaknesses. By integrating cross-species computational approaches [17] with robust hallucination detection [14] [18] and human-relevant validation systems [19], researchers can develop more reliable pipelines for drug development and biological discovery. The fundamental impossibilities in both domains [15] [20] suggest that future progress will come not from eliminating limitations entirely, but from developing sophisticated approaches to manage and work within these constraints while maintaining scientific rigor.

The Fit-for-Purpose (FFP) validation framework represents a paradigm shift in how computational models and biomarker assays are developed and evaluated for biomedical research and drug development. This approach emphasizes that validation criteria should be closely aligned with the specific Context of Use (COU)—the precise role a model or assay will play in decision-making processes [21]. In computational biology, FFP principles ensure that models provide sufficient evidence and performance to answer specific biological or clinical questions, avoiding both insufficient validation for high-stakes applications and unnecessarily stringent requirements for exploratory research.

The foundation of FFP validation rests on a clear definition established by the International Organisation for Standardisation: "the confirmation by examination and the provision of objective evidence that the particular requirements for a specific intended use are fulfilled" [22] [23]. This definition underscores that validation is not an absolute state but rather a continuum of evidence gathering tailored to the model's intended application. The position of a computational model along the spectrum between basic research tool and clinical decision support system directly dictates the stringency of validation required [22].

For computational models in biology, the FFP approach has been formalized through frameworks such as the CURE principles, which complement the well-known FAIR guidelines for data management. CURE emphasizes that models should be Credible, Understandable, Reproducible, and Extensible [24]. These principles provide a structured approach to ensure models are not only scientifically sound but also practically useful within their specified COU, balancing methodological rigor with practical utility in research and development settings.

Methodological Framework for Fit-for-Purpose Validation

Core Principles and Implementation Strategy

Implementing a fit-for-purpose approach requires systematic alignment between the validation strategy and the model's Context of Use. The FFP framework operates through five key stages that guide researchers from initial planning through ongoing validation maintenance [22] [23]:

- Stage 1: Purpose Definition and Assay Selection - Researchers define the explicit COU and select appropriate candidate models or assays, establishing predefined acceptance criteria based on the specific research questions.

- Stage 2: Method Development - All necessary reagents and components are assembled, a detailed validation plan is created, and the final classification of the model or assay is determined.

- Stage 3: Performance Verification - The experimental phase where performance is rigorously tested against predefined criteria, leading to the critical determination of fitness-for-purpose.

- Stage 4: In-Study Validation - Additional assessment of fitness-for-purpose within the actual research context, identifying real-world factors such as sample handling variability and analytical robustness.

- Stage 5: Routine Application - The model or assay enters regular use, with ongoing quality control monitoring, proficiency testing, and continuous improvement.

This staged approach emphasizes that FFP validation is an iterative process rather than a one-time event. At each stage, the "fitness" of the model is evaluated against its specific COU, allowing for refinement and adjustment as new data emerges or research questions evolve [22].

Classification of Models and Assays by Context of Use

The FFP approach categorizes computational models and biomarker assays into distinct classes based on their measurement characteristics and intended applications. Understanding these categories is essential for applying appropriate validation standards [22] [23]:

Table 1: Classification of Models and Assays in Fit-for-Purpose Validation

| Class | Description | Key Characteristics | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definitive Quantitative | Uses calibrators and regression to calculate absolute quantitative values | Fully characterized reference standard representing the biomarker; highest accuracy requirements | Mass spectrometric analysis; well-characterized ligand-binding assays |

| Relative Quantitative | Uses response-concentration calibration with non-representative standards | Reference standards not fully representative of the biomarker; more flexible accuracy standards | Ligand-binding assays (ELISA, multiplex platforms); many computational model predictions |

| Quasi-Quantitative | No calibration standard, but continuous response expressed as sample characteristics | Numerical values reported without absolute quantification; focuses on detection limits and dynamic range | Quantitative RT-PCR; some machine learning classifiers |

| Qualitative (Categorical) | Discrete scoring scales or binary classifications | Ordinal (discrete scores) or nominal (yes/no) outputs; precision and accuracy not applicable | Immunohistochemistry scoring; fluorescence in situ hybridization; binary classifiers |

Each category demands distinct validation approaches. For example, definitive quantitative assays require rigorous accuracy assessment using total error principles (combining systematic and random error components), while quasi-quantitative assays focus more on precision, sensitivity, and dynamic range [22]. This classification system helps researchers avoid the common pitfall of applying validation standards designed for one category to models or assays belonging to another.

Comparative Analysis of Validation Approaches

Performance Metrics Across Model Types

Different computational approaches require tailored validation metrics based on their specific Context of Use. The table below summarizes key performance parameters and their relevance across major model categories in computational biology:

Table 2: Performance Parameters for Different Model Categories in Fit-for-Purpose Validation

| Performance Characteristic | Definitive Quantitative | Relative Quantitative | Quasi-Quantitative | Qualitative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | ✓ | |||

| Trueness (Bias) | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Precision | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Reproducibility | ✓ | |||

| Sensitivity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Specificity | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Lower Limit of Quantitation | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Dilution Linearity | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Parallelism | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Assay Range | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

For definitive quantitative methods, performance standards have been well-established in bioanalysis, where precision (% coefficient of variation) and accuracy (mean % deviation from nominal) are expected to be <15% for most measurements and <20% at the lower limit of quantification [22]. However, the FFP approach allows for more flexibility in biomarker method validation, with 25-30% often being acceptable depending on the biological context and clinical application [22].

In computational model validation, alternative approaches like accuracy profiles have been developed, which account for total error (bias and intermediate precision) and pre-set acceptance limits defined by the user [22]. These profiles create β-expectation tolerance intervals that display confidence intervals (e.g., 95%) for future measurements, allowing researchers to visually determine what percentage of future values will likely fall within predefined acceptance limits [22].

Benchmarking Platforms for Expression Forecasting Models

The emergence of standardized benchmarking platforms has significantly advanced FFP validation for computational models in biology. One such platform, PEREGGRN (PErturbation Response Evaluation via a Grammar of Gene Regulatory Networks), provides a comprehensive framework for evaluating expression forecasting methods [5].

PEREGGRN includes a collection of 11 quality-controlled and uniformly formatted perturbation transcriptomics datasets, along with configurable benchmarking software that enables researchers to evaluate models using different data splitting strategies, performance metrics, and evaluation criteria [5]. A key aspect of its design is the nonstandard data split where "no perturbation condition is allowed to occur in both the training and the test set," ensuring rigorous evaluation of a model's ability to generalize to novel interventions [5].

The platform employs multiple evaluation metrics that fall into three broad categories: (1) standard performance metrics (mean absolute error, mean squared error, Spearman correlation), (2) metrics focused on the top 100 most differentially expressed genes to emphasize signal over noise, and (3) accuracy in classifying cell types, which is particularly relevant for reprogramming or cell fate studies [5]. This multi-metric approach acknowledges that no single metric can fully capture model performance across diverse biological contexts.

Recent benchmarking efforts have revealed important insights about expression forecasting methods. Studies have found that "it is uncommon for expression forecasting methods to outperform simple baselines" across diverse biological contexts [5]. This highlights the importance of rigorous, FFP benchmarking rather than relying on cherry-picked results that may overstate model capabilities.

Practical Applications and Case Studies

Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD)

The Fit-for-Purpose approach has been formally incorporated into Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) through regulatory pathways featuring "reusable" or "dynamic" models [21]. Successful applications include dose-finding and patient drop-out modeling across multiple disease areas, demonstrating how FFP principles accelerate drug development while maintaining scientific rigor.

In MIDD, FFP implementation requires that models be closely aligned with key Questions of Interest (QOI) and Context of Use (COU) across all stages of drug development [21]. This alignment is achieved through a strategic roadmap that matches appropriate modeling methodologies to specific development milestones:

- Early Discovery: Quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models and target identification

- Preclinical Development: Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling and first-in-human dose prediction

- Clinical Development: Population pharmacokinetics, exposure-response modeling, and clinical trial simulation

- Regulatory Submission & Post-Market: Model-based meta-analysis and label updates

A model is considered "not FFP" when it fails to define the COU, lacks adequate data quality, or has insufficient model verification, calibration, and validation [21]. Additionally, oversimplification, insufficient data quality or quantity, or unjustified incorporation of complexities can render a model unsuitable for its intended purpose [21].

Automated Model Refinement with Boolmore

The boolmore tool exemplifies FFP principles in practice through its automated approach to Boolean model refinement [25]. This genetic algorithm-based workflow streamlines the process of adjusting Boolean functions to enhance agreement with curated perturbation-observation pairs while leveraging existing mechanistic knowledge to limit the search space to biologically plausible models.

The boolmore workflow follows a systematic process:

- Mutation: Creates new model variants while preserving biological constraints and interaction graphs

- Prediction: Generates model predictions by calculating minimal trap spaces under different conditions

- Scoring: Computes fitness scores based on agreement with experimental data

- Selection: Retains top-performing models while favoring simplicity

In benchmark studies using 40 published Boolean models, boolmore demonstrated significant improvements in model accuracy, increasing from 49% to 99% on training sets and from 47% to 95% on validation sets [25]. This demonstrates that FFP-guided refinement does not merely overfit training data but produces models with genuine predictive power for novel situations.

Diagram 1: Boolmore automated model refinement workflow. The genetic algorithm iteratively mutates model functions while respecting biological constraints, evaluates fitness against experimental data, and selects improved models.

Community-Driven Benchmarking Initiatives

The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) has developed a community-driven benchmarking suite that operationalizes FFP principles for AI models in biology [4]. This resource addresses the critical bottleneck in biological AI development: the lack of trustworthy, reproducible benchmarks to evaluate model performance.

The CZI benchmarking suite includes several key features that embody FFP concepts:

- Multiple Evaluation Metrics: Each benchmarking task is paired with multiple metrics rather than relying on single scores, providing a more comprehensive view of performance

- Modular Design: Researchers can choose from command-line tools, Python packages, or no-code web interfaces based on their technical background and specific needs

- Community Contribution: The platform functions as a "living, evolving product" where researchers can propose new tasks, contribute evaluation data, and share models

- Biological Relevance: Benchmarks are designed to emphasize biological utility rather than mere technical performance

This approach directly addresses the FFP concern that models optimized for standard benchmarks may fail when applied to real-world biological questions [4]. By providing diverse, biologically relevant evaluation contexts, the platform helps ensure that models are fit for their specific intended purposes rather than simply achieving high scores on potentially misleading metrics.

Essential Research Toolkit for Fit-for-Purpose Validation

Implementing robust FFP validation requires a comprehensive toolkit of methodologies, software resources, and experimental approaches. The table below summarizes key resources referenced in this guide:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Fit-for-Purpose Validation

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boolmore | Software Tool | Automated Boolean model refinement using genetic algorithms | Signaling network modeling; perturbation prediction [25] |

| PEREGGRN | Benchmarking Platform | Evaluation of expression forecasting methods | GRN modeling; perturbation response prediction [5] |

| CZI Benchmarking Suite | Community Platform | Standardized evaluation of AI biology models | Virtual cell modeling; single-cell analysis [4] |

| GGRN Framework | Software Framework | Grammar of Gene Regulatory Networks for expression forecasting | Perturbation transcriptomics; drug target discovery [5] |

| CURE Principles | Guidelines | Credible, Understandable, Reproducible, Extensible model standards | Mechanistic model development; model sharing [24] |

| Accuracy Profiles | Statistical Method | β-expectation tolerance intervals for total error assessment | Definitive quantitative assay validation [22] |

This toolkit, combined with the methodological framework presented in this guide, provides researchers with essential resources for implementing FFP validation across diverse computational biology applications. The selection of specific tools should be guided by the intended Context of Use, with consideration for the specific biological questions, available data resources, and decision-making contexts that define each research initiative.

The Fit-for-Purpose framework represents a fundamental shift in how computational models are validated in biology and drug development. By emphasizing alignment between validation rigor and Context of Use, FFP approaches enable more efficient resource allocation, more relevant model evaluation, and ultimately more trustworthy computational tools for scientific discovery. As computational methods continue to expand their role in biomedical research, the principles outlined in this guide will remain essential for ensuring that models not only achieve technical excellence but also fulfill their intended scientific purposes.

Implementing Robust Validation Strategies Across the Biomedical Pipeline

Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) represents a transformative framework in pharmaceutical research that applies quantitative models to optimize drug development decisions and regulatory strategies [21]. A validation-first approach ensures these computational and statistical models are scientifically rigorous, fit-for-purpose, and reliable for informing critical development milestones. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has institutionalized this approach through programs like the MIDD Paired Meeting Program, which provides a formal pathway for sponsors to discuss and validate MIDD approaches for specific drug development programs [26]. This structured validation paradigm is crucial for balancing the risks and benefits of drug products throughout development, ultimately improving clinical trial efficiency and increasing regulatory success probabilities [26].

The fundamental premise of a validation-first approach centers on establishing model credibility through rigorous evaluation of context of use (COU), data quality, and model verification [21]. As MIDD methodologies evolve from "nice-to-have" to "regulatory essentials" [27], the validation process becomes increasingly critical for ensuring models can reliably inform decisions from early discovery through post-market surveillance.

Quantitative Impact of MIDD: Portfolio-Level Validation

The validation of MIDD approaches extends beyond scientific acceptance to demonstrable business impact. Recent portfolio-level analyses provide quantitative validation of MIDD's value proposition through standardized metrics including development cycle time reduction and cost savings.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of MIDD Across Drug Development Portfolio

| Metric | Impact | Scope | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Cycle Time | ~10 months reduction per program [28] | Annualized average across portfolio | Algorithm based on MIDD-related activities (e.g., trial waivers, sample size reduction) [28] |

| Cost Savings | ~$5 million per program [28] [29] | Annualized average across portfolio | Per Subject Approximation (PSA) values multiplied by subject counts for waived/reduced trials [28] |

| Clinical Trial Budget | $100 million reduction applied to annual budget [28] | Large pharmaceutical company | Historical comparison of model-informed vs. traditional study designs [28] |

These quantitative impacts are realized through specific MIDD-mediated efficiencies including clinical trial waivers, sample size reductions, and informed "No-Go" decisions that prevent costly late-stage failures [28]. The validation of these savings employs standardized algorithms that calculate time and cost avoidance based on MIDD-related activities across early and late-stage development programs [28].

Comparative Analysis of MIDD Approaches

Methodological Spectrum and Applications

MIDD encompasses a diverse spectrum of quantitative approaches, each with distinct validation requirements and applications across the drug development continuum.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of MIDD Approaches and Validation Protocols

| MIDD Approach | Primary Applications | Key Validation Protocols | Regulatory Acceptance Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) | Drug-drug interactions, special populations, FIH dosing [27] | Verification of physiological parameters, predictive performance testing [21] | High for specific contexts (e.g., DDI, pediatric extrapolation) [27] |

| Quantitative Systems Pharmacology (QSP) | Novel modalities, combination therapy, target selection [27] | Modular validation, virtual population qualification, sensitivity analysis [21] | Emerging, case-by-case assessment [21] |

| Population PK (PopPK) | Subject variability, dose regimen optimization [27] | Covariate model evaluation, visual predictive checks, bootstrap validation [27] | Well-established, expected in submissions [27] |

| Exposure-Response (ER) | Dose-response relationship, safety characterization [27] | Model diagnostics, predictive performance for efficacy/safety endpoints [27] | Well-established for dose justification [27] |

| Model-Based Meta-Analysis (MBMA) | Comparator analysis, trial design optimization [27] | Data curation standards, model stability assessment, external validation [27] | Growing acceptance for comparative effectiveness [27] |

Validation Workflow for MIDD Approaches

The validation process for MIDD methodologies follows a structured pathway that aligns with regulatory expectations and scientific best practices.

MIDD Validation Workflow

This validation workflow emphasizes the foundational importance of defining the Context of Use (COU) as the initial step, which determines the appropriate validation stringency throughout the process [21]. The FDA's "fit-for-purpose" initiative emphasizes that models should be "reusable" or "dynamic," with validation requirements proportional to their intended impact on development and regulatory decisions [21].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: PBPK Model Validation for Drug-Drug Interactions

Objective: To develop and validate a PBPK model capable of predicting cytochrome P450-mediated drug-drug interactions for regulatory submission.

Experimental Methodology:

- Model Building: Develop a base PBPK model using in vitro absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) data including:

- Metabolic stability data from human liver microsomes

- Transporter kinetics from transfected cell systems

- Plasma protein binding data [21]

- Model Verification: Verify the model using clinical pharmacokinetic data from single and multiple ascending dose studies in healthy volunteers [27]

- DDI Prediction: Apply the verified model to simulate DDI risk with common co-medications using the Perpetrator Indexing Approach

- Validation: Compare model-predicted DDI magnitudes (AUC and Cmax ratios) against observed clinical DDI study results [27]

- Sensitivity Analysis: Perform global sensitivity analysis to identify critical parameters driving DDI predictions

Validation Criteria: Successful model validation requires prediction of AUC and Cmax ratios within 1.25-fold of observed clinical data for strong index inhibitors/inducers [27].

Protocol: Exposure-Response Analysis for Dose Optimization

Objective: To characterize the exposure-response relationship for efficacy and safety endpoints to support dose selection for Phase 3.

Experimental Methodology:

- Data Assembly: Integrate population PK output (individual drug exposures) with efficacy endpoints and safety events from Phase 2 trials [27]

- Model Selection: Evaluate multiple mathematical models (Emax, logistic, linear) to describe exposure-response relationships

- Model Diagnostics: Apply comprehensive diagnostic plots including:

- Individual predictions vs. observations

- Conditional weighted residuals vs. predictions or time

- Visual predictive checks [27]

- Covariate Analysis: Identify patient factors (intrinsic/extrinsic) that significantly impact exposure-response relationships

- Clinical Trial Simulation: Simulate Phase 3 trial outcomes under different dosing regimens to optimize benefit-risk profile

Validation Criteria: Model acceptance requires successful visual predictive checks, absence of systematic bias in residuals, and physiological plausibility of parameter estimates [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Implementing a validation-first MIDD approach requires specialized computational tools and platforms that facilitate model development, qualification, and regulatory submission.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for MIDD Validation

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation Process |

|---|---|---|

| PBPK Platforms | Certara's Simcyp Simulator, GastroPlus | Provide validated physiological frameworks for predicting drug disposition and interactions [29] |

| Population PK/PD Software | NONMEM, Monolix, Phoenix NLME | Enable development of nonlinear mixed-effects models with comprehensive diagnostic capabilities [27] |

| QSP Platforms | Certara's QSP Platform, DILIsym, GI-Sym | Facilitate development of mechanistic disease models with modular validation capabilities [27] |

| Clinical Trial Simulators | Trial Simulator, East | Enable virtual patient generation and trial simulation to assess model performance [21] |

| Data Curation Tools | Codex Data Repository, CDISC standards | Provide standardized, curated historical data for model development and validation [27] |

| AI/ML Integration | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Scikit-learn | Enhance model development through pattern recognition in large datasets [29] |

Regulatory Integration and Future Directions

The Evolving Regulatory Landscape for MIDD Validation

The validation of MIDD approaches occurs within an increasingly structured regulatory framework. The FDA's MIDD Paired Meeting Program represents a formalized pathway for sponsors to discuss and validate MIDD approaches for specific development programs [26]. This program focuses on key validation areas including dose selection, clinical trial simulation, and predictive safety evaluation [26]. Globally, the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) is developing the M15 guideline to standardize MIDD practices across regions, promoting consistency in validation requirements [21].

Regulatory expectations for MIDD validation continue to evolve, with agencies increasingly expecting model-informed approaches to support development decisions. For oncology drugs, MIDD has become integral for characterizing PK/PD relationships, optimizing combination therapies, and supporting dose selection [27]. The FDA's growing acceptance of MIDD to support waivers for certain clinical studies (e.g., dedicated cardiac safety trials) further underscores the importance of robust validation [27].

Emerging Technologies and Validation Challenges

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning presents both opportunities and validation challenges for MIDD. AI technologies show promise for accelerating model development through automated model definition and validation [29]. However, these "black box" approaches require novel validation methodologies to establish reliability and interpretability for regulatory decision-making [21].

The movement toward an animal testing-free future also highlights the growing importance of validated MIDD approaches. The FDA Modernization Act 2.0 has opened pathways for using alternatives to animal testing, with MIDD playing a central role in this transition through approaches like Certara's Non-Animal Navigator solution [29]. This application demands particularly rigorous validation to ensure human safety predictions without traditional animal data.

The democratization of MIDD represents another frontier, where improved user interfaces and AI integration aim to make sophisticated modeling accessible beyond expert modelers [29]. This expansion necessitates robust, standardized validation frameworks that can be applied consistently across diverse user groups and organizations.

A validation-first approach to Model-Informed Drug Development represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical development, emphasizing scientific rigor, regulatory alignment, and demonstrable impact throughout the drug development lifecycle. As quantitative models become increasingly embedded in development decision-making and regulatory submissions, robust validation methodologies serve as the critical foundation ensuring these approaches deliver on their promise of more efficient, cost-effective drug development. The continued evolution of MIDD validation—fueled by emerging technologies, regulatory standardization, and portfolio-level value demonstration—positions this approach as an indispensable component of modern pharmaceutical development that benefits developers, regulators, and, most importantly, patients awaiting novel therapies.

In computational biology and drug development, machine learning (ML) models are powerful tools for accelerating discovery, from predicting protein structures to screening candidate molecules. The choice between physics-informed and data-driven ML paradigms significantly influences not just model performance but the entire validation strategy required to ensure reliable, biologically plausible results. Data-driven models excel at finding complex patterns in large datasets but can struggle with generalization when data is scarce or noisy. Physics-informed models integrate established biological and physical laws into the learning process, offering enhanced plausibility and data efficiency—a critical advantage in fields where acquiring large labeled datasets is costly or ethically challenging [30] [31]. This guide objectively compares these paradigms through the lens of validation, providing researchers with experimental data, protocols, and tools to guide their model selection and evaluation.

Paradigm Comparison: Core Characteristics and Experimental Performance

The fundamental difference between these paradigms lies in their use of prior knowledge. Data-driven models are purely inference-based, while physics-informed machine learning (PIML) explicitly incorporates domain knowledge, such as physical laws or biological constraints, into the model itself [30].

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

The following tables summarize experimental findings from various studies, highlighting the trade-offs in performance, computational cost, and adherence to physical laws.

Table 1: Comparative Model Performance on Specific Tasks

| Domain / Task | Model Type | Specific Model | Key Performance Metrics | Adherence to Physical/Biological Laws |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physics Data Analysis [32] | Data-Driven | XGBoost | Preferred for speed/effectiveness with limited data; High computational efficiency. | Not explicitly enforced; reliant on data patterns. |

| Physics-Informed | Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN) | Superior final accuracy; higher computational time. | High; explicitly enforced via loss function and architecture. | |

| Compound Flood Simulation [33] | Data-Driven | CNN-LSTM Hybrid | Balanced accuracy and efficiency; robust generalization. | Not explicitly enforced. |

| Physics-Informed | Finite-Difference-PINN (FD-PINN) | Stable, accurate predictions; ~6.5x faster than vanilla PINN. | High; hard-coded physical constraints. | |

| Metallic Additive Manufacturing [34] | Data-Driven | Traditional ML/LSTM | Suffers from error accumulation in long-horizon prediction. | Poor; lacks physical constraints. |

| Physics-Informed | Physics-Informed Geometric RNN | Max error reduced by ~4% compared to data-driven; handles long-horizon prediction. | High; enforces PDEs and boundary conditions. | |

| Electrode Material Design [35] | Data-Driven | ANN Regression | R² = 0.92 for specific capacitance; prediction within 0.3% of experimental value. | Implicitly learned from high-quality experimental data. |

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Paradigm Strengths and Weaknesses

| Aspect | Data-Driven ML | Physics-Informed ML (PIML) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Learns patterns and relationships exclusively from data [30]. | Integrates prior physics/domain knowledge with data-driven learning [30]. |

| Data Requirements | Requires large volumes of high-quality, labeled data. | Mitigates data scarcity by incorporating physical laws; more data-efficient [30]. |

| Output Plausibility | Risk of physiologically or physically implausible results [30]. | Ensures outputs are consistent with known physical/biological principles [30] [32]. |

| Generalizability | May fail when extrapolating beyond training data distribution. | Generally more robust and better at extrapolation due to physical constraints [30]. |

| Interpretability | Often operates as a "black box"; limited insight into causal mechanisms. | More interpretable; model structure and loss are tied to domain knowledge [34]. |

| Implementation Complexity | Relatively standard implementation and training. | Increased complexity in designing architecture and loss functions to encode knowledge [30] [32]. |

| Primary Validation Focus | Statistical performance on held-out test data. | Statistical performance + mechanistic plausibility + adherence to governing laws. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

A robust validation framework is essential for trusting model predictions, especially in high-stakes fields like drug development. The following protocols, drawn from active research, provide a blueprint for rigorous evaluation.

Protocol 1: Validating Randomization in Experimental Data

This methodology uses ML not for prediction, but as a diagnostic tool to validate the fundamental assumption of randomization in experimental data, which is crucial for downstream analysis [36].

- Objective: To detect potential assignment bias or flaws in participant/experiment randomization before proceeding with primary analysis [36].

- Dataset Preparation: Compile data encompassing initial participant/sample characteristics (e.g., demographics, baseline measurements) and their subsequent group assignments.

- Model Training & Evaluation:

- Task Formulation: Frame the problem as a binary classification task where models predict group assignment based on initial characteristics.

- Model Selection: Implement both supervised (e.g., Logistic Regression, Decision Trees, SVM) and unsupervised (e.g., k-means, k-NN) models [36].

- Synthetic Data Augmentation: If sample size is small, generate synthetic data to enlarge the training set and improve model stability [36].

- Performance Analysis: Train models and evaluate classification accuracy. In a perfectly randomized experiment, no model should reliably predict group assignment. Classification accuracy significantly above a chance level (e.g., >60%) suggests detectable patterns and potential randomization flaws [36].

- Feature Importance Analysis: Use the trained models to identify which initial characteristics are most predictive of group assignment, pinpointing the source of bias [36].

Protocol 2: Benchmarking PIML vs. Data-Driven ML

This protocol outlines a head-to-head comparison for a predictive task, evaluating both statistical performance and adherence to domain knowledge.

- Objective: To compare the accuracy, efficiency, and physical/biological plausibility of physics-informed and data-driven models on a specific task (e.g., predicting molecular behavior or cellular response).

- Dataset & Preprocessing:

- Data Compilation: Curate a dataset containing input parameters (e.g., compound features, environmental conditions) and corresponding target outputs (e.g., binding affinity, reaction yield) [32] [37].

- Stratified Splitting: Split the dataset into training, validation, and test sets using a stratified k-fold approach (e.g., 5 folds) to maintain class distribution, especially for imbalanced data [32].

- Standard Scaling: Normalize the feature space to ensure models sensitive to feature magnitude are not biased [32].

- Model Implementation:

- Data-Driven Models: Train a suite of standard models for baseline comparison (e.g., Random Forest, XGBoost, standard Neural Networks) [32].

- Physics-Informed Model: Implement a Physics-Informed Neural Network (PINN). A PINN typically features a dual-output architecture where the network simultaneously predicts the primary target (e.g., viability) and intermediate physical observables (e.g., decay modes, energy states). The loss function is crafted to include a term for the prediction error and a term that penalizes the violation of known physical laws governing the observables [32].

- Validation & Metrics:

- Statistical Metrics: Calculate standard metrics (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, ROC AUC, R²) on the test set [32].

- Physical Consistency: Quantify how much the model outputs violate known physical constraints (e.g., conservation laws). This is inherent in the PINN's physics-loss term [32] [34].

- Computational Cost: Record the training and inference time for each model [32].

- Generalization Test: Evaluate models on a newly collected, previously unseen experimental validation set to assess real-world robustness [35].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following tools and conceptual "reagents" are fundamental for conducting rigorous ML validation in computational biology.

Table 3: Essential Toolkit for Validating Computational Biology ML Models

| Category / Item | Function & Role in Validation |

|---|---|

| High-Quality Experimental Datasets | Serves as the ground truth for training and the ultimate benchmark for validating model predictions. Data should be curated from controlled experiments or high-fidelity simulations [35] [37]. |

| Stratified K-Fold Cross-Validation | A statistical technique to reliably estimate model performance and mitigate overfitting, especially crucial with limited or imbalanced biological data [32]. |

| Synthetic Data Generation Algorithms | Used to augment small experimental datasets, improving model stability and providing a means to test model behavior in edge cases or scenarios with scarce data [36]. |

| Physics-Informed Loss Function | The core "reagent" of PIML. It encodes domain knowledge (e.g., differential equations, conservation laws) as a soft constraint, penalizing model outputs that are physically or biologically implausible during training [32] [34]. |

| Feature Importance Analyzers (e.g., SHAP) | Tools for model interpretation that identify which input features most influence the output. This is vital for validating that a model's decision-making aligns with biological intuition and established science [35]. |

| Independent Experimental Validation Set | A set of newly generated, previously unseen data points used for the final model assessment. This is the gold standard for proving a model's robustness and predictive power in real-world applications [35]. |

The choice between data-driven and physics-informed ML is not about declaring one universally superior. Instead, it is about matching the paradigm to the problem's constraints and the validation resources available. Data-driven models, like XGBoost, offer a powerful, fast starting point, especially with limited data and computational resources [32]. However, for applications demanding high plausibility, the ability to extrapolate, and resilience in the face of data scarcity, the additional complexity of physics-informed models like PINNs is a worthwhile investment [30] [34]. A hybrid future, where robust statistical performance and mechanistic understanding are validated in tandem, promises to accelerate the development of more reliable and transformative computational tools in biology and drug discovery.

Validating computational models that integrate genomics, proteomics, and clinical data represents a critical frontier in computational biology. As high-throughput technologies generate massive volumes of biological data, researchers face the fundamental challenge of determining whether their multi-modal integration approaches genuinely capture meaningful biological signals rather than computational artifacts. The complexity of biological systems, combined with the high-dimensional nature of omics data, creates a validation landscape requiring sophisticated methodologies and rigorous benchmarking standards. Multi-omics integration is essential for unraveling the complexity of cellular processes and disease mechanisms, particularly in complex diseases like cancer where understanding the interplay between genetic mutations, gene expression changes, protein modifications, and metabolic shifts is critical for developing effective treatments [38] [39].

This guide examines the current landscape of multi-modal model validation, objectively comparing the performance of different integration approaches and providing experimental protocols for assessing model efficacy. Within the broader thesis of computational biology validation research, we focus specifically on methodologies for verifying that integrated models of genomics, proteomics, and clinical data produce biologically plausible and clinically actionable insights. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, proper validation is not merely an academic exercise but a necessary step toward translating computational predictions into tangible biomedical advances.

Comparative Methodologies for Multi-Modal Integration

Data Integration Approaches and Their Applications

Multi-modal data integration strategies can be broadly categorized into three main approaches, each with distinct validation requirements and performance characteristics. The table below summarizes the key methodologies currently employed in computational biology research:

Table 1: Multi-Modal Data Integration Approaches and Applications

| Integration Type | Key Methodologies | Strengths | Validation Challenges | Representative Tools |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statistical & Correlation-Based | Pearson's/Spearman's correlation, WGCNA, xMWAS, Correlation networks | Identifies linear relationships, Handles pairwise associations, Simple implementation | Limited to linear relationships, Sensitive to data normalization, Multiple testing burden | xMWAS [40], WGCNA [40] |

| Multivariate Methods | PCA, MOFA, CCA, PLS | Dimensionality reduction, Identifies latent factors, Handles missing data | Interpretability of latent factors, Computational intensity with high dimensions | MOFA [38], CCA [38] |

| Machine Learning/Deep Learning | Autoencoders, CNNs, Random Forests, Logistic Regression | Captures non-linear relationships, Handles high-dimensional data, End-to-end learning | "Black box" interpretability, Extensive data requirements, Overfitting risk | Deep learning models [39], Ensemble methods [40] |

Deep Learning Integration Workflows