A Practical Guide to Benchmarking Computational Biology Tools: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Impact

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the rigorous benchmarking of computational biology tools.

A Practical Guide to Benchmarking Computational Biology Tools: From Foundational Principles to Clinical Impact

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the rigorous benchmarking of computational biology tools. It covers foundational principles, including the critical role of neutral benchmarks and stakeholder needs. The guide details methodological best practices for study design, dataset selection, and workflow formalization, and offers troubleshooting strategies for common technical and optimization challenges. Furthermore, it explores advanced topics in performance validation, metric selection, and the interpretation of comparative results. By synthesizing current literature and emerging practices, this resource aims to empower scientists to conduct transparent, reproducible, and impactful benchmarking studies that accelerate method development and enhance the reliability of computational findings in biomedical research.

The Why and Who: Establishing the Bedrock of Robust Benchmarking

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, selecting the right computational tool is a critical decision that can directly impact research outcomes and resource allocation. Benchmarking provides the empirical evidence needed to make these choices confidently. In computational biology, two primary types of benchmarking studies have emerged: Methods-Development Papers (MDPs), where new methods are compared against existing ones, and Benchmark-Only Papers (BOPs), where existing methods are compared in a more neutral way [1] [2]. Understanding the distinction between these approaches and the fundamental requirement for neutrality forms the foundation for rigorous computational tool evaluation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between an MDP and a BOP?

An MDP (Methods-Development Paper) is conducted by method developers to demonstrate the merits of their new approach compared to existing state-of-the-art and baseline methods [3]. Its primary focus is showcasing the new method's advantages. In contrast, a BOP (Benchmark-Only Paper) is a neutral study performed to systematically compare a set of existing methods, typically by independent groups without a vested interest in any particular tool's performance [1] [3]. BOPs aim to provide an impartial comparison for the benefit of the end-user community.

Q2: Why is neutrality so critical in benchmarking studies?

Neutrality is essential because it minimizes perceived bias and ensures results accurately reflect real-world performance [3]. Non-neutral benchmarks risk unfairly advantaging or disadvantaging certain methods through choices in datasets, evaluation metrics, or parameter tuning. This can mislead the scientific community and impede progress. Well-executed neutral benchmarks build trust, enhance transparency, and provide reliable guidance for researchers choosing computational methods [1] [2].

Q3: What are common sources of bias in benchmarking studies?

Common sources of bias include:

- Dataset Selection: Using datasets that disproportionately favor one method [3].

- Parameter Tuning: Extensively tuning parameters for a preferred method while using defaults for others [3].

- Ground Truth Definition: Using an inappropriate or biased definition of correctness [1].

- Implementation Variations: The same model yielding different performance scores across laboratories due to implementation differences rather than scientific factors [4].

Q4: How can a benchmarking ecosystem address current challenges?

A continuous benchmarking ecosystem provides standardized, community-driven platforms for evaluation [1] [4]. Such systems can:

- Formalize benchmark definitions through configuration files [1] [2].

- Orchestrate standardized workflows across reproducible software environments [2].

- Provide interactive results dashboards for flexible filtering and aggregation of metrics [1].

- Reduce redundancy by making existing results accessible and extendable, saving valuable research time [4].

Troubleshooting Common Benchmarking Issues

Problem: Inconsistent results when replicating a benchmark study.

- Cause: Variations in software environments, dependency versions, or computing hardware.

- Solution: Use containerization technologies (Docker, Singularity) and workflow systems (Nextflow, Snakemake, Common Workflow Language) to capture complete computational environments [1] [2]. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative's benchmarking suite addresses this through standardized, modular packages that ensure consistent implementation [4].

Problem: Suspected bias in method comparison favoring a newly developed tool.

- Cause: The benchmark may be an MDP where parameters were extensively tuned for the new method while competing methods used default settings.

- Solution: Verify if the study follows neutral benchmarking guidelines [3]. Check if parameter tuning was performed equally for all methods or if the authors involved developers of competing methods to ensure optimal usage. For future studies, use blinded evaluation procedures where possible [3].

Problem: Benchmark results become stale quickly in a fast-moving field.

- Cause: New methods emerge rapidly after publication, making static comparisons outdated.

- Solution: Utilize or contribute to "living" benchmarking ecosystems designed for continuous integration of new methods and datasets [1] [4]. These systems allow benchmarks to evolve alongside the field, maintaining relevance through community contributions.

Problem: Difficulty determining which benchmarked method works best for your specific dataset.

- Cause: Method performance often depends on specific data characteristics, and published benchmarks may not include datasets similar to yours.

- Solution: Look for benchmarks that thoroughly characterize dataset properties and provide access to the code and software stack needed to apply methods to your data [1]. Flexible benchmarking systems allow filtering and aggregation of metrics based on data characteristics relevant to your research question.

Experimental Protocols for Rigorous Benchmarking

Protocol 1: Designing a Neutral Benchmarking Study

- Define Scope and Purpose: Clearly state whether the study is an MDP or BOP. For BOPs, aim for comprehensive method inclusion [3].

- Select Methods: Establish transparent inclusion criteria (e.g., software availability, installability) applied equally to all methods. For neutral benchmarks, include all available methods or a representative subset justified without favoritism [3].

- Collect Datasets: Include diverse datasets representing various conditions. Use both simulated data (with known ground truth) and real experimental data. Validate that simulated data accurately reflect properties of real data [3].

- Define Metrics: Select multiple complementary metrics to provide a thorough view of performance [4].

- Execute Workflow: Use standardized workflow systems to ensure consistent execution across methods [2].

- Analyze and Report: Contextualize results according to the benchmark's purpose. For BOPs, provide clear user guidelines and highlight method weaknesses for developers [3].

Protocol 2: Creating Experimental Datasets with Ground Truth

When suitable public datasets are unavailable, construct benchmarks with known ground truth:

- Spike-in Controls: Introduce synthetic RNA molecules at known concentrations in RNA-sequencing experiments [3].

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting: Sort cells into known subpopulations prior to single-cell RNA-sequencing [3].

- Cell Line Mixing: Create pseudo-cells by mixing different cell lines in known proportions [3].

- Sex Chromosome Genes: Use genes located on sex chromosomes as proxies for DNA methylation status [3].

Benchmarking Methodologies and Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Characteristics of MDPs vs. BOPs

| Characteristic | Methods-Development Papers (MDPs) | Benchmark-Only Papers (BOPs) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Demonstrate new method advantages | Neutral comparison of existing methods |

| Typical Conductors | Method developers | Independent researchers or consortia |

| Method Selection | Representative subset (state-of-the-art, baseline) | Comprehensive, all available methods |

| Neutrality | Potential for bias (requires careful design) | High (explicitly designed for neutrality) |

| Community Involvement | Limited | Often high (may include method authors) |

| Result Interpretation | Highlights new method contributions | Provides user guidelines and identifies field gaps |

Table 2: Benchmark Dataset Types and Applications

| Dataset Type | Key Features | Performance Evaluation | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulated Data | Known ground truth; customizable parameters | Direct comparison to known truth | Method validation; scalability testing |

| Real Experimental Data | Biological complexity; no perfect ground truth | Comparison to gold standard or consensus | Real-world performance assessment |

| Designed Experimental Data | Hybrid approach with introduced ground truth | Direct metrics against engineered truth | Controlled validation of specific capabilities |

Benchmarking Workflow and Stakeholder Relationships

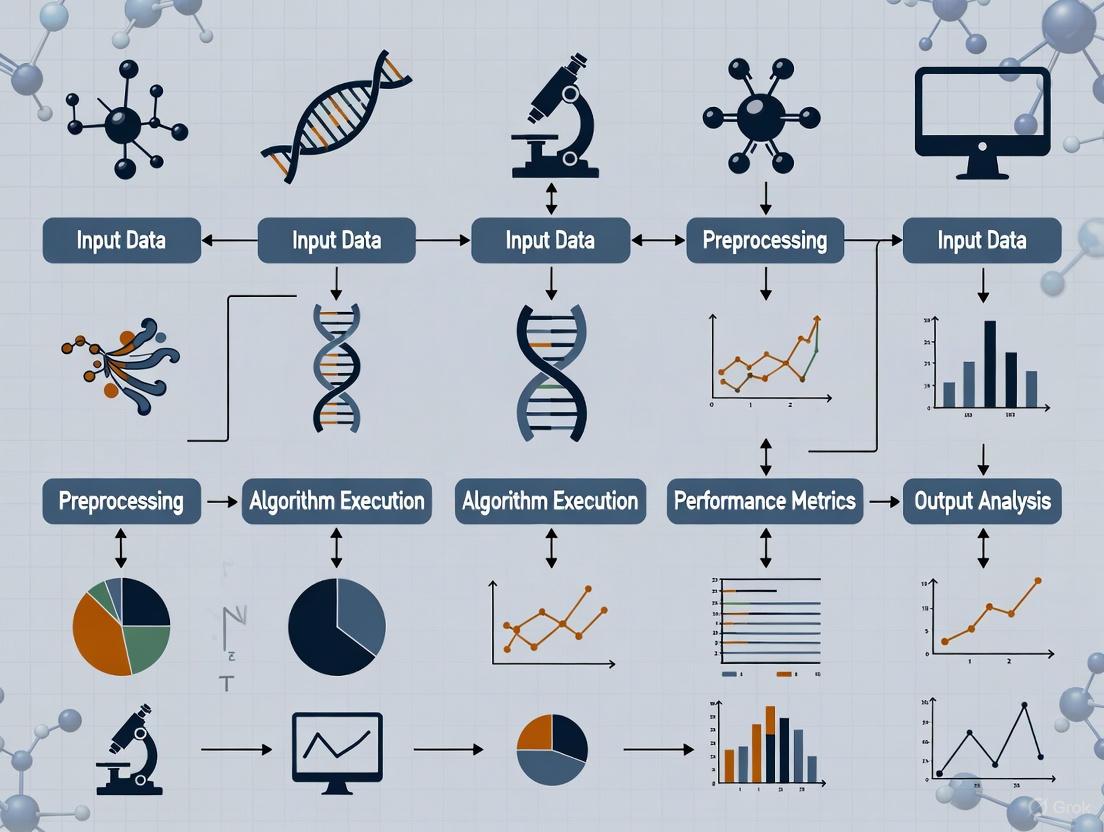

Diagram 1: Benchmarking ecosystem workflow and stakeholder relationships.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Components for Computational Benchmarking

| Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Workflow Systems | Orchestrate reproducible execution of methods | Common Workflow Language (CWL), Nextflow, Snakemake [2] |

| Containerization | Ensure consistent software environments | Docker, Singularity, Conda environments [1] |

| Benchmarking Suites | Provide standardized evaluation frameworks | CZI's cz-benchmarks Python package, community challenges [4] |

| Reference Datasets | Serve as ground truth for performance evaluation | Simulated data, spiked-in controls, sorted cell populations [3] |

| Performance Metrics | Quantify method performance across dimensions | Multiple complementary metrics per task [4] |

| Visualization Dashboards | Enable interactive exploration of results | Web-based interfaces for result filtering and comparison [1] [4] |

The field of computational biology is driven by a diverse ecosystem of stakeholders, each with unique needs, perspectives, and requirements. The ultimate goal of benchmarking computational biology tools is to evaluate and improve the performance, reliability, and applicability of software and algorithms used in biological research and clinical practice. This technical support center addresses the specific issues these stakeholders encounter, providing troubleshooting guidance and FAQs framed within the context of rigorous benchmarking research. The development of comprehensive benchmarks, such as BixBench—a dataset comprising over 50 real-world scenarios with nearly 300 questions designed to measure the ability of LLM-based agents to explore biological datasets—highlights the community's push toward more practical evaluation metrics beyond simple knowledge recall [5]. Effective implementation of these tools hinges on understanding and addressing the needs of all involved parties, from the developers creating algorithms to the clinicians applying them at the patient bedside [6] [7].

The computational biology landscape involves multiple stakeholder groups whose engagement is critical for successful tool implementation. A systematic review of stakeholder perspectives toward diagnostic artificial intelligence identified four primary groups: patients, clinicians, researchers, and healthcare leaders [6]. Each group possesses different priorities and concerns influencing their decision to adopt or not adopt computational technologies. The following table summarizes these key stakeholder groups and their primary needs within the computational biology tool ecosystem.

Table 1: Key Stakeholder Groups and Their Primary Needs

| Stakeholder Group | Primary Needs & Priorities | Key Concerns |

|---|---|---|

| Method Developers [5] [8] [9] | Robust benchmarking frameworks, standardized metrics, computational efficiency, algorithm scalability, reproducible research practices. | Tool performance, accuracy, robustness, interoperability, and adoption by the research community. |

| Bioinformatics Researchers [10] [8] [11] | User-friendly tools, comprehensive documentation, accessible data formats, clear troubleshooting guides, reproducible analytical workflows. | Data integration from disparate sources, tool usability, data quality, and normalization across different platforms [10]. |

| Clinicians [6] [7] | Seamless EHR integration, clinical decision support, interpretable results, workflow compatibility, evidence of clinical utility. | Trust in algorithm outputs, time efficiency, liability, and how the tool fits within existing clinical workflows and patient interactions [6] [7]. |

| Patients and the Public [6] [12] | Privacy and confidentiality, transparent data usage, understandable explanations of results, respect for autonomy. | Data security, potential for discrimination, and how their genetic or health information will be used and protected [6] [12]. |

| Healthcare Leaders [6] [7] | Cost-effectiveness, regulatory compliance, return on investment, operational efficiency, improved patient outcomes. | Financial sustainability, implementation costs, staff training requirements, and integration with existing health IT systems. |

Essential Tools and Research Reagents

Computational biology relies on a diverse toolkit of software and resources for analyzing biological data. The following table details key tools and their primary functions in standard computational biology workflows.

Table 2: Essential Computational Biology Tools and Resources

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLAST [11] | Sequence Alignment & Analysis | Compares nucleotide or protein sequences to databases to identify regions of similarity. | Gene identification, functional analysis, and evolutionary studies. |

| GATK [11] | Genomic Analysis | Provides tools for variant discovery and genotyping from high-throughput sequencing data. | Variant calling in cancer genomics, population genetics, and personalized medicine. |

| DESeq2/edgeR [11] | Transcriptomics Analysis | Identifies differentially expressed genes from RNA-Seq count data using statistical modeling. | Gene expression studies to understand disease mechanisms and gene regulation. |

| Bioconductor [11] | Genomic Data Analysis | An open-source platform providing extensive R packages for high-throughput genomic analysis. | Comprehensive analysis and comprehension of diverse genomic data types. |

| KEGG [11] | Pathway & Functional Analysis | Integrates genomic, chemical, and systemic functional information for pathway mapping. | Functional annotation of genes, understanding disease mechanisms, and drug development. |

| EquiRep [8] | Specialized Genomic Analysis | Identifies repeated patterns in error-prone sequencing data to reconstruct consensus units. | Studying genomic repeats linked to neurological and developmental disorders. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our clinical team is resistant to adopting a new genomic decision support tool. What implementation strategies are most effective?

- A: Successful implementation requires proactive stakeholder engagement across all phases. This includes involving clinical champions early in the decision process, conducting workflow analysis during pre-implementation, and establishing efficient feedback loops post-implementation to address usability concerns. Engaging organizational leadership is also crucial for allocating necessary resources and encouraging adoption [7].

Q2: We are getting inconsistent results when integrating data from different sequencing centers. What are the potential causes?

- A: Inconsistent results often stem from data normalization problems. Different instruments, laboratory protocols, or calibration methods can introduce systematic biases. Ensure that normalization procedures are applied to correct for these technical variations, and verify that all datasets are processed using compatible data standards and formats [10].

Q3: How can we assess the real-world performance of a computational biology tool beyond standard accuracy metrics?

- A: Frameworks like BixBench advocate for evaluation based on real-world biological scenarios that test a tool's ability to perform multi-step analytical trajectories and interpret nuanced results. Beyond accuracy, consider metrics for scalability, usability, interoperability, and robustness across diverse datasets [5] [9].

Q4: Our RNA-Seq analysis with DESeq2 is failing due to "missing values" errors. What should I check?

- A: This commonly occurs when the count matrix contains rows (genes) with zero counts across all samples. Filter out genes with minimal expression before analysis. You can use

rowSums(counts(matrix)) > 0to create a filtering index and subset your data to remove these genes, ensuring a valid statistical fit.

- A: This commonly occurs when the count matrix contains rows (genes) with zero counts across all samples. Filter out genes with minimal expression before analysis. You can use

Q5: A patient has expressed concern about how their genomic data will be stored and used in our research. How should we address this?

- A: Building trust through transparent communication is essential. Clearly explain how data will be anonymized, stored securely, and used only for the approved research purposes. Discuss the consent process in detail, including any options for future data use, and emphasize the measures in place to protect their confidentiality [12].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental and Workflow Issues

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Common Computational Biology Problems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions | Stakeholders Most Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| High participant dropout in a longitudinal genomics study. | Poor participant rapport, high burden, inadequate communication, privacy concerns [12]. | Implement rules for building rapport and instilling autonomy. Simplify protocols, provide regular updates, and ensure transparent confidentiality safeguards. | Researchers, Patients |

| Inability to integrate heterogeneous biological datasets. | Lack of scalable data integration systems, incompatible data standards, non-uniform data models [10]. | Employ robust data integration systems that can transform retrieved data into a common model. Advocate for and adopt community-wide data standards. | Researchers, Method Developers |

| A clinical decision support alert for a drug-gene interaction is frequently overridden by clinicians. | Alert fatigue, poor integration into clinical workflow, lack of clinician trust or understanding of the underlying evidence [6] [7]. | Engage clinicians in the tool selection and design phase. Optimize alert specificity and provide concise, evidence-based explanations within the clinical workflow. | Clinicians, Healthcare Leaders |

| Variant calling tool (e.g., GATK) performs poorly on long-read sequencing data. | Tool algorithms may be optimized for specific sequencing technologies (e.g., short-reads) and may not handle the different error profiles of long-read data. | Consult tool documentation for compatibility. Explore specialized tools designed for long-read data or adjust parameters (e.g., error rates, mapping quality thresholds) if possible. | Researchers, Method Developers |

| A newly published benchmark ranks our tool lower than expected. | Differences in evaluation metrics, benchmark dataset composition, or workflow parameters compared to internal validation. | Critically analyze the benchmark's methodology, including the metrics of success and the representativeness of the test data. Use the findings to guide targeted improvements. | Method Developers |

Workflow and Stakeholder Engagement Diagrams

Computational Biology Tool Benchmarking Workflow

Stakeholder Engagement Framework for Implementation

A guide to constructing and troubleshooting rigorous, reproducible evaluations for computational biology tools.

In the fast-paced field of computational biology, benchmarking is the cornerstone of rigorous research. It provides the evidence needed to validate new computational methods, compare them against the state of the art, and guide users in selecting the right tool for their scientific question. This guide breaks down the core components of a successful benchmark and addresses common challenges researchers face.

Why is a formal benchmarking system necessary?

Traditional, one-off benchmarking studies often suffer from reproducibility challenges, implementation biases, and quickly become outdated. A systematic approach is needed because benchmarking involves more than just running workflows; it includes tasks like managing contributions, provisioning hardware, handling software environments, and rendering results dashboards [13]. A well-defined benchmarking system ensures fairness, reproducibility, transparency, and trust, ultimately accelerating scientific progress [1] [13].

Core Components of a Benchmark

A robust benchmark is built on four foundational pillars, each playing a critical role in ensuring a fair and informative evaluation [1].

| Component | Description | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Task | The specific problem the methods are designed to solve. | Must be well-defined and reflect a real-world biological or computational challenge [1]. |

| Datasets | The reference data used to evaluate the methods. | Include diverse, realistic data (simulated and real) with ground truth where possible [14] [15]. |

| Methods | The computational tools or algorithms being evaluated. | Ensure correct implementation and use of appropriate parameters in a reproducible software environment [1]. |

| Metrics | The quantitative measures used to assess method performance. | Should be aligned with the task and relevant to end-users. Using multiple metrics provides a holistic view [1] [4]. |

The relationship between these components and the benchmarking process can be visualized as a structured workflow.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

How can I ensure my benchmark is fair and not biased toward my own method?

- A: To ensure neutrality, use datasets that were not used in the development or training of the methods being evaluated. Rely on realistic simulated data or independent, real-world validation sets. Furthermore, a neutral benchmark should compare a new method against the current state of the art, not just older or weaker approaches [1]. Involving the community through platforms like OpenProblems.bio or CZI's benchmarking suite can also provide external oversight and validation [4] [16].

I'm benchmarking 14 methods. How do I manage the different software environments?

- A: This is a common challenge, as different tools often require conflicting software dependencies (e.g., R vs. Python versions). The key is to use technologies that containerize each method. Platforms like OpenProblems use Viash to automatically wrap code from different languages into portable, versioned containers (e.g., Docker). These containers are then executed within scalable workflow systems like Nextflow on platforms such as Seqera [16]. This approach ensures that each method runs in its own reproducible environment, making large-scale benchmarking feasible.

How do I choose the right metrics?

- A: Select metrics that are most relevant to the end-user, typically a biologist or data analyst. A single metric is rarely sufficient; instead, use a suite of metrics to evaluate different aspects of performance. For example, a comprehensive benchmark of tools for identifying Spatially Variable Genes (SVGs) used six different metrics to evaluate aspects like gene ranking, statistical calibration, and computational scalability [15]. The table below from that study shows how metrics can provide a multi-faceted view.

| Performance Aspect | Example Metric |

|---|---|

| Gene Ranking | Area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC) |

| Statistical Calibration | P-value uniformity under null hypothesis |

| Scalability | Running time, Memory usage |

My benchmark results are inconsistent across datasets. What should I do?

- A: This is expected and actually highlights the importance of using multiple, diverse datasets. Method performance is often dependent on data characteristics, such as the technology used (e.g., sequencing- vs. imaging-based spatial transcriptomics) or the biological system [1] [15]. Your benchmark should characterize the datasets thoroughly and present results disaggregated by dataset. This helps users understand which method performs best under specific conditions relevant to their work.

How can I make my benchmark reproducible and extensible?

- A: Reproducibility starts with using a formal workflow system (e.g., Nextflow, Snakemake) and versioning all code and data. For extensibility, design your benchmark as a living, community-driven resource. This can be achieved by:

- Using a standardized configuration file to define all benchmark components [1].

- Creating a modular structure that allows others to easily contribute new methods, datasets, or metrics, as done in community platforms like OpenProblems.bio and CZI's benchmarking suite [4] [16].

- Publishing all components openly to adhere to FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Platforms & Reagents

Building a benchmark from scratch is complex. Leveraging existing community-driven platforms and tools can save immense time and effort.

| Tool / Platform | Function | URL |

|---|---|---|

| OpenProblems.bio | A living, community-run platform for benchmarking single-cell and spatial methods. Provides formalized tasks, curated datasets, and metrics. | https://openproblems.bio |

| CZI Benchmarking Suite | A standardized toolkit for benchmarking AI-driven virtual cell models, including tasks for cell type classification and perturbation prediction. | Chan Zuckerberg Initiative |

| Viash | A "code-to-pipeline" tool that wraps scripts (Python/R) into reproducible, containerized components, ready for workflow systems. | https://viash.io |

| Nextflow & Seqera | Workflow management system (Nextflow) and platform (Seqera) for orchestrating and scaling benchmarks elastically on cloud or HPC. | https://nextflow.io, https://seqera.io |

The Vision of a Continuous Benchmarking Ecosystem

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common technical and methodological issues encountered when setting up or participating in a continuous benchmarking ecosystem for computational biology tools.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the primary purpose of a continuous benchmarking ecosystem in computational biology? A1: The primary purpose is to provide a systematic, neutral framework for evaluating the performance of computational methods against defined tasks and datasets. It aims to automate benchmark studies, ensure reproducibility through standardized software environments and workflows, and provide a platform for ongoing, community-driven method comparison, moving beyond one-off, publication-specific evaluations [1] [4].

Q2: We want to contribute a new dataset to an existing benchmark. What is the required metadata? A2: While specific requirements may vary, a comprehensive dataset for a benchmarking ecosystem should be accompanied by metadata that includes a detailed description of the experimental design, the biological system studied, data-generating technology, processing steps, and a clear definition of the ground truth or positive controls. This ensures the dataset is Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable (FAIR) for the community [1].

Q3: What are the most common tools for managing benchmarking workflows?

A3: Workflow management systems are indispensable for creating reproducible and automated benchmarking pipelines. Common tools mentioned in the context of bioinformatics include Nextflow, Snakemake, and Galaxy [17]. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative's benchmarking suite also offers command-line tools and Python packages (e.g., cz-benchmarks) for integration into development cycles [4].

Q4: How can we prevent overfitting to a static benchmark? A4: To prevent overfitting, a benchmarking ecosystem should be a "living, evolving" resource. This involves regularly incorporating new and held-out evaluation datasets, refining metrics based on community input, and developing tasks for emerging biological questions. This approach discourages optimization for a small, fixed set of tasks and promotes model generalization [4].

Q5: How do I ensure the results of my benchmark are reproducible? A5: Key practices include using version control for all code, explicitly documenting software versions and dependencies, using containerized environments, and thoroughly documenting all parameters and preprocessing steps. Workflow management systems can automate much of this, capturing the exact computational environment used [1] [17].

Troubleshooting Common Technical Issues

Table: Common Benchmarking Issues and Solutions

| Issue | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pipeline Failure at Alignment Stage | Outdated reference genome index; Incorrect file formats; Insufficient memory [17]. | Check tool log files for error messages; Validate input file formats with tools like FastQC; Monitor system resources [17]. |

Rebuild reference index with updated tool version; Convert files to correct format; Allocate more computational resources or optimize parameters [17]. |

| Inconsistent Results Between Runs | Software version drift; Undocumented parameter changes; Random seed not fixed [1]. | Use version control to audit changes; Re-run in a containerized environment; Check for hard-coded paths. | Use container technology; Implement a formal benchmark definition file to snapshot all components; Set and document all random seeds [1]. |

| Poor Performance of New Method | Method is not suited for the dataset type; Incorrect implementation; Data quality issues [1]. | Compare method performance on different dataset classes; Validate implementation against a known simple case; Run data quality control (e.g., FastQC, MultiQC) [17]. |

Contribute to the benchmark by adding datasets where your method excels; Re-examine the method's core assumptions [1]. |

| Tool Dependency Conflicts | Incompatible versions of programming languages or libraries [17]. | Use dependency conflict error messages to identify problematic packages. | Use containerized environments or package managers to create isolated, reproducible software stacks [1] [17]. |

| High Computational Resource Use | Inefficient algorithm; Pipeline not optimized for scale; Data structures too large [17]. | Use profiling tools to identify bottlenecks; Check if data can be downsampled for testing. | Optimize code; Migrate to a cloud platform with scalable resources; Use more efficient data formats [17]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Benchmarking Tasks

This section provides detailed methodologies for core experiments in a computational benchmarking study.

Protocol 1: Benchmarking a New Cell Clustering Method for Single-Cell RNA-Seq Data

Objective: To evaluate the performance of a new cell clustering algorithm against existing methods using a standardized benchmarking task.

Materials:

- Reference Dataset: A well-annotated single-cell RNA-seq dataset with known ground truth cell labels (e.g., from a cell line mixture or a highly characterized tissue).

- Computing Environment: A containerized environment with all necessary software dependencies.

- Workflow Management: A

SnakemakeorNextflowpipeline to orchestrate the analysis.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Run standard quality control and normalization on the reference dataset using the steps defined in the benchmark. This ensures all methods are evaluated on the same preprocessed data.

- Method Execution: Run the new clustering method and established baseline methods within the same computational environment. Key parameters for all methods should be documented.

- Metric Calculation: Compute a set of predefined metrics to evaluate the clustering results. Common metrics include:

- Adjusted Rand Index (ARI): Measures the similarity between the predicted clusters and the ground truth labels.

- Normalized Mutual Information (NMI): Another information-theoretic measure of cluster similarity.

- Cluster Purity: Measures the extent to which each cluster contains cells from a single class.

- Results Aggregation: Compile the results from all methods into a comparative report. The CZI benchmarking suite, for example, allows for easy comparison of one model’s performance against others on tasks like cell clustering [4].

Protocol 2: Evaluating a Variant Calling Pipeline

Objective: To assess the accuracy and efficiency of a genomic variant calling workflow.

Materials:

- Reference Data: A reference genome and a sequencing dataset (e.g., whole-genome sequencing) for a sample with a known set of true variants (e.g., from the Genome in a Bottle consortium).

- Tools: Alignment tools (

BWA,Bowtie2), variant callers (GATK,SAMtools), and benchmarking tools (hap.py).

Procedure:

- Data Alignment: Align the sequencing reads to the reference genome.

- Variant Calling: Execute the variant calling pipeline to identify single nucleotide polymorphisms and insertions/deletions.

- Performance Comparison: Compare the called variants against the known truth set to calculate performance metrics.

- Analysis: Analyze the results to identify strengths and weaknesses.

Table: Key Performance Metrics for Variant Calling Evaluation

| Metric | Formula | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Precision | True Positives / (True Positives + False Positives) | Proportion of identified variants that are real. Higher is better. |

| Recall (Sensitivity) | True Positives / (True Positives + False Negatives) | Proportion of real variants that were identified. Higher is better. |

| F1-Score | 2 * (Precision * Recall) / (Precision + Recall) | Harmonic mean of precision and recall. Provides a single balanced score. |

System Diagrams and Workflows

Continuous Benchmarking Ecosystem Architecture

Benchmarking Workflow Execution Logic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table: Key Components of a Continuous Benchmarking Ecosystem

| Category | Item | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Infrastructure | Workflow Management Systems (Nextflow, Snakemake) | Orchestrates complex analysis pipelines, ensuring reproducibility and portability across different computing environments [17]. |

| Container Technologies (Docker, Singularity) | Packages software and its dependencies into isolated, reproducible units, eliminating "it works on my machine" problems [1]. | |

| Cloud Computing Platforms (AWS, Google Cloud) | Provides scalable, on-demand resources for running large-scale benchmarks and storing massive datasets [17]. | |

| Data & Method Standards | Curated Reference Datasets | Provides the ground truth for evaluating method performance. These must be well-characterized and have clear definitions of correctness [1] [4]. |

| Community-Defined Tasks & Metrics | Formalizes the scientific question being evaluated (the task) and provides standardized, multi-faceted measures for assessing performance (the metrics) [4]. | |

| Benchmark Definition File | A single configuration file (e.g., YAML) that formally specifies all components of a benchmark: code versions, software environments, parameters, and datasets for a release [1]. | |

| Community & Governance | Version Control (Git) | Tracks changes to code, methods, and benchmark definitions, which is fundamental for reproducibility and collaboration [17]. |

| Interactive Reporting Dashboards | Allows users to explore and filter benchmarking results interactively, facilitating understanding and adoption by a broader audience, including non-experts [18] [4]. |

Blueprint for Success: Designing and Executing Your Benchmarking Study

Benchmarking is a critical, multi-faceted process in computational biology that serves distinct purposes for different stakeholders. At its core, a benchmark is a conceptual framework to evaluate the performance of computational methods for a given task, requiring a well-defined task and a definition of correctness or ground-truth [1]. These evaluations generally fall into two categories: Method-Development Papers (MDPs), where new methods are compared against existing ones, and Benchmark-Only Papers (BOPs), which provide a more neutral comparison of existing methods [1]. A robust benchmarking ecosystem must orchestrate workflow management, community engagement, and the generation of benchmark 'artifacts' like code snapshots and performance outputs systematically, adhering to standards of fairness, reproducibility, and transparency [1]. This technical support center is designed to help researchers navigate this complex landscape and troubleshoot common experimental issues.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Benchmarking

1. What is the fundamental difference between a neutral comparison and a method introduction?

A method introduction (typically an MDP) is driven by method developers aiming to demonstrate their new tool's competitive advantage against existing state-of-the-art methods [1]. In contrast, a neutral comparison (BOP) is structured to impartially evaluate a set of existing methods, often using neutral datasets and metrics to avoid intrinsic bias, and is highly utilized and influential for guiding methodological developments [1].

2. Why is a formal 'benchmark definition' important?

A formal benchmark definition, which can be expressed as a configuration file, specifies the entire scope and topology of components to be included [1]. This includes details of code repositories with versions, instructions for creating reproducible software environments, parameters used, and which components to snapshot for a release. This formalization is key for ensuring reproducibility, transparency, and long-term maintainability [1].

3. Who are the primary stakeholders in a benchmarking ecosystem, and what are their needs?

- Data Analysts use benchmarks to select suitable methods for their specific datasets and analysis tasks. They benefit from benchmarks that include diverse, well-characterized datasets and flexible filtering of metrics [1].

- Method Developers require benchmarking to compare their new methods against the current state of the art in a neutral setting. A accessible ecosystem reduces redundancy and lowers the entry barrier for development [1].

- Journals & Funding Agencies rely on well-executed benchmarks to ensure published or funded methods meet high standards. They have a vested interest in results being FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable) to maximize community benefit [1].

Troubleshooting Common Benchmarking Workflow Errors

Issue 1: FASTA File Parsing Errors in Phylogenetic Tools

Error Message:

"Fasta parsing error, RAxML expects an alignment. the last sequence in the alignment seems to have a different length" [19]

Diagnosis and Solution: This error indicates that the sequences in your FASTA file are not properly aligned, meaning they do not have identical lengths. Even a single extra character in one sequence will cause the failure.

- Step 1: Validate Sequence Lengths. Manually check the length of each sequence in your file. Most sequence editors and command-line tools (like

awk) can report sequence lengths. - Step 2: Check for Non-Sequence Characters. Ensure the sequence data contains only valid IUPAC characters (A, T, G, C, N, etc.) and no spaces or other special characters within the sequence lines. The description header should be on a single line starting with ">", and the sequence itself should consist of only line breaks and valid nucleotides [20] [21].

- Step 3: Re-align Sequences. If sequences are unaligned, use a multiple sequence alignment tool (e.g., MUSCLE, MAFFT, Clustal Omega) before running the phylogenetic analysis.

Best Practice: Always use the NCBI-approved FASTA format: a definition line starting with ">" followed by a unique SeqID without spaces, and the sequence data using IUPAC symbols, with lines typically no longer than 80 characters [21].

Issue 2: BLAST Database Creation or Runtime Failures

Error Message:

"BLAST Database error: No alias or index file found for protein database [C:\Program] in search path..." [22]

Diagnosis and Solution: This error on Windows systems is commonly caused by spaces in the file path to your BLAST database or input files [22].

- Solution 1: Use Simple Directory Paths. Move your database and input files to a directory with a path that contains no spaces, for example,

C:\BLAST_DB\[22]. - Solution 2: Use Quotation Marks. When specifying paths in your BLAST command, enclose the entire path in double quotation marks.

- Solution 3: Check for Consistent Success. For intermittent BLAST failures, always check the exit status of the BLAST run. A non-zero exit code indicates an error. Capture standard error (STDERR) to a log file for detailed diagnostics [23].

Best Practice: Structure your BLAST projects in a simple, space-free directory hierarchy and implement error checking in your scripts.

Issue 3: Memory and Algorithm Errors in Multiple Sequence Alignment

Error Message:

"Fatal error, exception caught" or "Out of memory" during alignment with tools like MUSCLE or Clustal Omega, especially with long or highly divergent sequences [24].

Diagnosis and Solution: These errors occur when the alignment algorithm exhausts available system memory due to computational complexity.

- Solution 1: Use a Memory-Efficient Algorithm. Switch to an alignment method designed for larger datasets, such as the Mauve algorithm, or enable Brenner's alignment method, which uses less memory at the cost of some accuracy [24].

- Solution 2: Fragment Long Sequences. Break very long sequences into shorter, more manageable segments using tools like DNASTAR SeqNinja before attempting alignment [24].

- Solution 3: Allocate More Resources. If possible, run the alignment on a machine with more RAM.

Experimental Protocols for Key Benchmarking Tasks

Protocol 1: Designing a Neutral Benchmarking Study

Objective: To impartially compare the performance of a set of existing computational methods on a defined biological task.

Methodology:

- Task and Ground Truth Definition: Precisely define the biological task (e.g., gene expression quantification, variant calling, phylogenetic inference) and establish a trusted ground-truth dataset. This could be simulated data or a well-curated experimental dataset with known answers [1].

- Component Selection: Assemble the benchmark components [1]:

- Datasets: Select a diverse set of input datasets that reflect real-world variability.

- Methods: Choose a representative set of existing methods to be compared.

- Metrics: Define a set of performance metrics (e.g., sensitivity, precision, F1-score, runtime, memory usage).

- Workflow Orchestration: Execute all methods on all datasets using a workflow management system (e.g., Nextflow, Snakemake) within containerized software environments (e.g., Docker, Singularity) to ensure reproducibility [1].

- Result Aggregation and Analysis: Collect all performance metrics. Use flexible ranking and aggregation approaches to allow different stakeholders to assess methods based on metrics relevant to their needs [1].

Protocol 2: Incorporating a New Method into an Existing Benchmark

Objective: To integrate a newly developed method into a continuous benchmarking ecosystem for comparison with the state of the art.

Methodology:

- Benchmark Definition Access: Obtain the configuration file or specification of the existing benchmark, which defines the software environments, datasets, parameters, and metrics [1].

- Method Packaging: Package the new method such that it adheres to the input/output specifications and can be executed within the defined software environment of the benchmark.

- Integration and Execution: Integrate the new method's code into the benchmark's workflow. The system will then automatically run the new method on all specified datasets.

- Result Inclusion and Snapshotting: The results for the new method are incorporated into the benchmarking system's results. A snapshot of the entire benchmark, including the new method, can be generated for publication, ensuring reproducibility at that point in time [1].

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Benchmarking Ecosystem Logical Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points in a continuous benchmarking ecosystem.

Research Reagent Solutions for Benchmarking

The following table details key computational "reagents" and materials essential for conducting robust benchmarking studies in computational biology.

| Item | Function in Benchmarking | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Datasets | Provides the input data and ground truth for evaluating method performance. | Include both simulated and curated experimental datasets. Must be well-characterized and representative of real-world data [1]. |

| Software Containers | Ensures reproducible software environments across different computing architectures. | Use Docker or Singularity images with pinned versions of all software dependencies [1]. |

| Workflow Management System | Automates the execution of methods on datasets, ensuring consistency and scalability. | Examples: Nextflow, Snakemake, or CWL. Manages complex, multi-step analyses [1]. |

| Benchmark Definition File | Formally specifies the entire set of components and topology of the benchmark. | A single configuration file (e.g., YAML, JSON) that defines code versions, parameters, and snapshot rules [1]. |

| Performance Metrics | Quantifies the performance of methods, allowing for neutral comparison. | Should include a diverse set (e.g., accuracy, speed, memory usage) to allow for flexible, stakeholder-specific ranking [1] [19]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

How do I define the scope of my benchmark to guide method selection? The purpose of your benchmark is the most important factor determining which methods to include. Generally, benchmarks fall into one of two categories, each with different inclusion strategies [3]:

- Neutral Benchmarks: The goal is to provide a systematic, unbiased comparison for the community. You should strive to be as comprehensive as possible, including all available methods for a given type of analysis.

- Method Development Benchmarks: The goal is to demonstrate the relative merits of a new method. It is acceptable to include a representative subset of existing methods, such as current best-performing methods, widely used tools, and simple baseline methods.

What are the minimum criteria a method should meet to be included? To ensure fairness and practicality, you should define clear, justified inclusion criteria that do not favor any specific method. Common criteria include [3]:

- The software implementation is freely available.

- It can be successfully installed and executed without errors after a reasonable amount of troubleshooting.

- It is accessible for commonly used operating systems.

What should I do if a method is difficult to install or run? Document these efforts thoroughly in a log file. This transparency saves other researchers time and provides valuable context if a widely used method must be excluded. Involving the method's authors can sometimes help resolve technical issues [3] [25].

How can I avoid bias when selecting a representative subset of methods? When you cannot include all methods, avoid selecting tools based solely on personal preference. Instead, use objective measures to guide your selection [25]:

- Popularity: Consider the number of citations or widespread community adoption.

- Performance Claims: Include methods that have claimed to be state-of-the-art in their publications.

- Representativeness: Ensure the selected set covers different algorithmic approaches (e.g., deep learning, random forests, statistical models) and data types.

What is the "self-assessment trap" and how can I avoid it? The "self-assessment trap" refers to the inherent bias introduced when developers benchmark their own new method, as they are almost guaranteed to show it performs well. To ensure neutrality [26] [27]:

- If you are benchmarking a method you developed, this must be stated prominently as a caveat.

- The ideal neutral benchmark is conducted by researchers who are equally familiar with all included methods or, alternatively, in collaboration with the original method authors to ensure each tool is evaluated under optimal conditions [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key resources and their functions for conducting a robust benchmarking study.

| Item | Function in Benchmarking |

|---|---|

| Literature Search Tools (e.g., PubMed) | To compile a comprehensive list of existing methods and their publications for inclusion [25]. |

| Software Repository (e.g., GitHub, Bioconda) | To access the software implementations of the methods to be benchmarked. |

| Log File | To document the process of installing, running, and excluding methods, ensuring transparency and reproducibility [25]. |

| Containerization Tools (e.g., Docker, Singularity) | To package software with all its dependencies, ensuring a reproducible and portable computational environment across different systems [1] [25]. |

| Spreadsheet for Metadata | To summarize key information about the benchmarked algorithms, including underlying methodology, software dependencies, and publication citations [25]. |

| Compute Cluster/Cloud Environment | To provide the necessary computational power and scalability for running multiple methods on various benchmark datasets. |

Experimental Protocol for Method Selection

Objective: To establish a systematic, transparent, and reproducible protocol for selecting computational methods to include in a benchmarking study.

Procedure:

- Define Benchmark Purpose: Clearly document whether the study is a neutral comparison or for method development, as this dictates the scope of inclusion [3].

- Conduct Literature Review: Perform a systematic search on platforms like PubMed to identify all potentially relevant methods. Review the references of identified publications to find additional tools [25].

- Establish Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria: Pre-define objective criteria for method inclusion, such as public availability and installability. Justify any exclusion of widely used methods [3].

- Document the Selection Process: Maintain a log file that records every method considered, the outcome of the inclusion criteria check, and notes on any installation or runtime failures [25].

- Create a Benchmarking Spreadsheet: Populate a spreadsheet with key metadata for each included method, such as the underlying algorithm, required dependencies, and parameters [25].

- Engage the Community (Optional but Recommended): For neutral benchmarks, widely announce the study to invite participation from method authors. This can help ensure optimal tool execution and comprehensive inclusion [3].

Workflow for Unbiased Method Selection

The diagram below outlines the logical workflow for selecting methods in a benchmarking study.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is "ground truth" and why is it critical for benchmarking? Ground truth refers to data that is known to be factual and represents the expected, correct outcome for the system being evaluated. It serves as the "gold standard" or "correct answer" against which the performance of computational methods is measured [28] [29] [25]. In machine learning, it is essential for training, validating, and testing AI models to ensure their predictions reflect reality [28]. In bioinformatics benchmarking, it allows for the calculation of quantitative performance metrics to determine how well a method recovers a known signal [3] [25].

I have a new computational method. Should I benchmark it with simulated or real data? The most rigorous benchmarks typically use a combination of both. Each type has distinct advantages and limitations, and together they provide a more complete picture of a method's performance [3] [25]. Simulated data allows for precise, quantitative evaluation because the true signal is known, while real data tests the method's performance under realistic biological complexity [3].

How can I generate ground truth when it's not experimentally available? For some analyses, you can design experimental datasets that contain a built-in ground truth. Common strategies include:

- Spiking-in synthetic molecules at known concentrations in sequencing experiments [3].

- Using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to sort cells into known subpopulations before single-cell RNA-sequencing [3].

- Leveraging biological knowledge, such as genes on sex chromosomes as a proxy for DNA methylation status [3].

- Employing Large Language Models (LLMs) to automate ground truth generation from source documents, followed by human review by subject matter experts to ensure accuracy (a human-in-the-loop process) [29].

A benchmark I want to use seems out of date. How can I contribute? The field is moving towards continuous benchmarking ecosystems. These are platforms designed to be public, open, and allow for community contributions. You can propose corrections to existing benchmarks, add new methods for comparison, or introduce new datasets. This approach helps keep benchmarks current and valuable for the entire community [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: My method performs well on simulated data but poorly on real data.

This is a common problem that often points to a poor simulation model or a flaw in the benchmarking design.

- Potential Cause 1: The simulation is overly simplistic. The simulated data fails to capture key properties of real biological data [3] [25].

- Solution: Before relying on simulation results, validate that your simulated datasets accurately reflect relevant properties of real data. Use empirical summaries (e.g., dropout profiles for single-cell RNA-seq, dispersion-mean relationships) to compare your simulated data against real experimental data [3].

- Potential Cause 2: Discrepancy between simulated and real-world dynamics. The assumptions used to generate the simulated data do not hold in a real-world setting [30].

Issue 2: I cannot find a pre-existing dataset with a reliable ground truth for my specific problem.

- Potential Cause: Gold standard experimental data can be prohibitively expensive or complex to generate for some applications [25].

- Solution: Consider a human-in-the-loop (HITL) pipeline for ground truth generation. This involves using a combination of automation and expert curation [29].

- Use a prompt-based strategy with an LLM to generate initial question-answer-fact triplets from your source data [29].

- Implement a scalable, automated pipeline to process large amounts of data [29].

- Have subject matter experts review a sample of the generated ground truth to verify that critical business or biological logic is correctly represented. The required level of review is determined by the risk of having incorrect ground truth [29].

- Solution: Consider a human-in-the-loop (HITL) pipeline for ground truth generation. This involves using a combination of automation and expert curation [29].

Issue 3: The benchmarking results are inconsistent and hard to reproduce.

- Potential Cause: Lack of standardized software environments and computational workflows.

- Solution: Adopt modern benchmarking systems that use containerization (e.g., Docker). This packages software with all its dependencies, ensuring the tool runs identically across different platforms and operating systems. This practice increases the transparency and computational reproducibility of benchmarking studies [1] [25].

Data Selection Guide: Simulated vs. Real Data

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of simulated and real datasets to guide your selection.

| Feature | Simulated Data | Real Data |

|---|---|---|

| Ground Truth | Known by design [3] | Often unknown or imperfect; must be established [3] |

| Core Advantage | Enables precise, quantitative performance evaluation [3] | Tests performance under realistic, biological complexity [3] [25] |

| Data Complexity | Can be overly simplistic and fail to capture true experimental variability [25] | Inherently complex, containing technical noise and biological variation [25] |

| Control & Scalability | Full control; can generate unlimited data to study variability [3] | Limited by cost and ethics of experiments; fixed in size [25] |

| Primary Risk | Models used for simulation can introduce bias, making results irrelevant to real-world use [25] | Lack of known ground truth can make quantitative evaluation difficult or impossible [3] |

| Best Uses | Testing scalability, stability, and performance under idealized conditions; method development [3] | Final validation of methods; evaluating biological plausibility of results [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Ground Truth Generation

Protocol 1: Generating Ground Truth from Source Documents using LLMs

This protocol is adapted from best practices for evaluating generative AI question-answering systems and can be adapted for biological knowledge bases [29].

- Define Objective and Requirements: Clearly define the model's goals and the types of data and labels required.

- Develop a Labeling Strategy: Create standardized guidelines for how to annotate various data formats to ensure consistency.

- Automated Generation with an LLM:

- Input: Chunks of source data (e.g., scientific literature, database entries).

- Process: Use a base LLM prompt template that instructs the model to take a fact-based approach. The LLM is assigned a persona to identify facts (entities) from the source and assemble them into question-answer-fact triplets.

- Output: The generation output is formatted as fact-wise JSONLines records.

- Human-in-the-Loop (HITL) Review: Subject matter experts (SMEs) review a sample of the generated ground truth. They verify that the questions are fundamental and that the answers align with biological knowledge and business value. The level of review is based on the risk of incorrect ground truth.

- Address Bias: Use multiple, diverse annotators for each data point and employ data augmentation strategies for underrepresented groups to minimize bias in the ground truth dataset.

Protocol 2: Establishing Ground Truth in Bioimage Analysis

The Broad Bioimage Benchmark Collection (BBBC) provides standardized methodologies for different types of ground truth [31].

- For Object Counts:

- Method: Have one or more humans count the number of cells/objects in each image.

- Ground Truth: The mean of the human counts is used.

- Benchmarking Metric: Calculate the mean error (in percent) of the algorithm's count compared to the ground truth across all images.

- For Foreground and Background Segmentation:

- Method: A human produces a binary (black and white) image where foreground pixels (objects) are white and background pixels are black.

- Benchmarking Metric: Report precision, recall, and the F-factor (harmonic mean of precision and recall). Tools like CellProfiler's

CalculateImageOverlapmodule can be used.

- For Biological Labels (e.g., in a dose-response assay):

- Method: Use control samples with known expected biological results.

- Benchmarking Metric: Calculate the Z'-factor (if multiple positive and negative controls are available) or the V-factor (for dose-response curves). These statistics measure how well an algorithm separates controls given the biological variation.

The workflow for selecting and validating a dataset for benchmarking is summarized in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Containerization Software (e.g., Docker) | Creates reproducible software environments by packaging a tool with all its dependencies, ensuring consistent execution across different computers [1] [25]. |

| Workflow Management Systems | Orchestrates and automates the execution of complex benchmarking workflows, connecting datasets, methods, and computing infrastructure [1]. |

| Ground Truth Generation Pipeline | A serverless batch architecture (e.g., using AWS Step Functions, Lambda, Amazon S3) that automates the ingestion, chunking, and prompting of LLMs to generate ground truth data at scale [29]. |

| CellProfiler Software | An open-source bioimage analysis package that provides modules for calculating benchmarking metrics like image overlap, Z'-factor, and V-factor against manual ground truth [31]. |

| FMEval | A comprehensive evaluation suite that provides standardized implementations of metrics to assess the quality and responsibility of AI models, such as Factual Knowledge and QA Accuracy [29]. |

| Continuous Benchmarking Platform | A computational platform designed to orchestrate benchmark studies, allowing components to be public, open, and accepting of community contributions to keep benchmarks current [1]. |

Technical Comparison at a Glance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of CWL, Snakemake, and Nextflow to aid in selection and troubleshooting.

| Feature | Common Workflow Language (CWL) | Snakemake | Nextflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Language | YAML/JSON (Declarative) [32] | Python-based DSL [33] | Apache Groovy-based DSL [34] |

| Execution Model | Command-line tool & workflow wrappers [32] | Rule-based, file-directed dependency graph [35] | Dataflow (Reactive) model via processes & channels [34] |

| Key Strength | Vendor-neutral, platform-agnostic standard [32] | Human-readable syntax and direct Python integration [33] [35] | Unified parallelism and implicit scalability [36] [34] |

| Software Management | Supports Docker & SoftwareRequirement (in specs) [37] | Integrated Conda & container support [33] [35] | Native support for Docker, Singularity, Conda [36] [34] |

| Portability | High (Specification-based, multiple implementations possible) [32] | High (Profiles for cluster/cloud execution) [33] | High (Abstraction layer for many platforms) [36] [34] |

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

This section addresses common specific issues users might encounter during their experiments.

Q1: My CWL workflow fails with a "Not a valid CWL document" error. What should I check?

This is often a syntax or structure issue. First, verify that your document's header includes the mandatory cwlVersion and class fields (e.g., class: CommandLineTool or class: Workflow) [32] [37]. Second, ensure your YAML is correctly formatted; misplaced colons or incorrect indentation are common culprits. Use a YAML linter or the --validate flag in cwltool to check for errors.

Q2: How can I force Snakemake to re-run a specific rule even if the output files exist?

You can use the --force command-line flag to force the re-execution of all rules. To target a single rule and all rules that depend on its output, use the --forceall flag and specify the rule name or one of its output files (e.g., snakemake --forceall my_rule).

Q3: My Nextflow process is not running in parallel as expected. What is the most common cause?

This is typically due to how input channels are defined. Nextflow's parallelism is driven by its channels. If you use a value channel (created by default when you provide a simple value or a single file), the process is executed only once. To enable parallelism, ensure your inputs are provided via queue or channel declarations, which create a value channel for each item, triggering multiple process executions [34]. For example, use Channel.fromPath("*.fastq") instead of a direct file path.

Q4: How do I manage different software versions for different steps in my workflow? All three tools integrate with containerization to solve this:

- CWL: Use the

DockerRequirementin therequirementssection of aCommandLineToolto specify a unique Docker image for that step [37]. - Snakemake: Use the

container:directive within a rule to define a container image specifically for that rule's execution [33] [35]. - Nextflow: Use the

containerdirective within a process definition. Each process can have its own container, isolating its software environment [36] [34].

Q5: The cluster job scheduler kills my Snakemake/Nextflow jobs without an error. How can I debug this? This often relates to insufficient requested resources. Both tools allow you to dynamically request resources.

- In Snakemake, you can define resource requirements (e.g., memory, runtime) within rules and use a

--cluster-configfile or a profile to map these to your scheduler's commands [33]. - In Nextflow, you can define computational resources (

cpus,memory,time) for each process in the process definition itself, and Nextflow will translate these into directives for the underlying executor (SLURM, PBS, etc.) [34]. Check your executor's logs for the exact submission command that failed.

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

For a robust thesis benchmarking these tools, the following methodological approach is recommended.

1. Workflow Selection and Design Select a representative, multi-step computational biology workflow, such as a DNA-seq alignment and analysis pipeline (e.g., from FASTQ to sorted BAM and variant calling) [37]. Implement the exact same workflow logic in CWL, Snakemake, and Nextflow. Key steps should include file decompression, read alignment, file format conversion, sorting, and indexing to test a variety of operations [37].

2. Performance Metrics Quantify the following metrics across multiple runs:

- Total Wall-Time: From workflow launch to final output.

- CPU/Memory Efficiency: Ratio of actual resource use to allocated resources.

- Overhead: Time spent by the workflow engine itself on scheduling and management, distinct from the tool execution time.

- Scaling Efficiency: How performance changes when moving from a local machine to a cluster, measured by speedup and parallel efficiency.

- Resume Efficiency: Time taken to successfully recover and continue from a simulated failure.

3. Usability and Reproducibility Assessment

- Code Complexity: Measure lines of code and cyclomatic complexity for each implementation.

- Portability: Test the workflow on at least two different execution environments (e.g., local and a cloud batch service like AWS Batch) [36] [34].

- Reproducibility: Verify that identical results are produced across all three implementations and execution platforms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below details key "reagents" or components essential for building and running formalized workflows.

| Item / Solution | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

cwltool |

The reference implementation of the CWL specification, used to execute CWL-described tools and workflows [32]. |

| Conda / Bioconda | A package manager and a repository of bioinformatics software. Used by Snakemake and Nextflow to manage software dependencies in an isolated manner [33] [38]. |

| Docker / Singularity | Containerization technologies that encapsulate the entire software environment, ensuring absolute portability and reproducibility across different compute infrastructures [36] [34] [37]. |

| Inputs Object File (JSON/YAML) | In CWL, a file that provides the specific input values (e.g., file paths, parameters) for a workflow run, separate from the workflow logic itself [32]. |

| Profile (Snakemake) | A configuration file that persists settings (like executor options or resource defaults) for a specific execution environment (e.g., SLURM cluster), avoiding the need for long command-line invocations [33]. |

| Executor (Nextflow) | The component that determines where and how the workflow processes are run (e.g., local, slurm, awsbatch). It abstracts the underlying platform, making the workflow definition portable [34]. |

| Process & Channel (Nextflow) | The core building blocks. A process defines a single computational task, while a channel connects processes, enabling the reactive dataflow model and implicit parallelism [34]. |

| Rule (Snakemake) | The core building block of a Snakemake workflow. A rule defines how to create output files from input files using shell commands, scripts, or wrappers [35]. |

Workflow System Logical Flow

The following diagram visualizes the high-level logical flow and decision points within each workflow system, helping to conceptualize their operational models.

Diagram: Conceptual Execution Models of CWL, Snakemake, and Nextflow. CWL uses a runner to interpret declarative steps. Snakemake builds a file-based execution graph from a target. Nextflow processes are triggered reactively by data flowing through channels.

Implementing FAIR Principles for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable Results

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for FAIR Benchmarking

Findability Issues

Problem: My benchmarked results and workflow cannot be found by colleagues or automated systems.

| Solution Component | Implementation Example | Tools & Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Persistent Identifiers (PIDs) | Assign a DOI to your entire benchmarking workflow, including datasets, code, and results. | DOI, WorkflowHub [39] |

| Rich Metadata | Describe the benchmark using domain-specific ontologies (e.g., EDAM for bioinformatics) in a machine-readable format. | Bioschemas, RO-Crate [39] |

| Indexing in Repositories | Register the workflow in a specialized registry like WorkflowHub instead of a general-purpose repository like GitHub. | WorkflowHub, Zenodo [39] |

Q: What is the most common mistake that makes a benchmark unfindable? A: The most common mistake is depositing the workflow and results in a general-purpose repository without a persistent identifier or rich, structured metadata. A GitHub repository alone is insufficient for findability. The workflow and its components must be deposited in a recognized registry with a DOI and descriptive metadata that allows both people and machines to understand its purpose and content [40] [39].

Q: My benchmark uses multiple tools; what exactly needs a Persistent Identifier (PID)? A: For a composite object like a benchmark, PIDs should be assigned at multiple levels for optimal findability and credit:

- The overall workflow specification [40].

- The input and reference datasets used [39].

- The individual software components and tools that are part of the workflow [40].

- The final output and performance results [41].

Accessibility Issues

Problem: Users can find my benchmark's metadata but cannot access the data or code to run it themselves.

| Solution Component | Implementation Example | Tools & Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Protocols | Ensure data and code are retrievable via standard, open protocols like HTTPS. | HTTPS, APIs |

| Authentication & Authorization | Implement controlled access for sensitive data, with clear instructions for obtaining permissions. | OAuth, Data Use Agreements |

| Long-Term Preservation | Use trusted repositories that guarantee metadata accessibility even if the data itself becomes unavailable. | WorkflowHub, Zenodo, ELIXIR Repositories [39] |

Q: My benchmark data is sensitive. Can it still be FAIR? A: Yes. FAIR does not necessarily mean "open." The "Accessible" principle requires that data and metadata are retrievable through a standardized protocol, which can include authentication and authorization layers. The metadata should remain openly findable, with clear instructions on how authorized users can request access to the underlying data [42] [43].

Q: I've shared my code on GitHub. Is my benchmark now accessible? A: Not fully. While GitHub uses standard protocols, it is not a preservation repository. For true, long-term accessibility, you should deposit a specific, citable version of your code in a trusted repository that provides a Persistent Identifier (like a DOI) and has a commitment to long-term archiving, such as WorkflowHub or Zenodo [39].

Interoperability Issues

Problem: My benchmark workflow produces results that cannot be integrated with other tools or datasets, limiting its utility.

| Solution Component | Implementation Example | Tools & Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Workflow Language | Define the workflow using a common, portable language like CWL. | Common Workflow Language (CWL), Snakemake, Nextflow [39] |

| Standardized Vocabularies | Annotate inputs, outputs, and parameters using community-accepted ontologies. | EDAM Ontology, OBO Foundry Ontologies |

| Containerization | Package software dependencies in containers to ensure consistent execution across platforms. | Docker, Singularity [39] |

Q: What is the single most effective step to improve my benchmark's interoperability? A: Using a standard workflow language like the Common Workflow Language (CWL) is highly recommended. This abstracts the workflow logic from the underlying execution engine, allowing the same benchmark to be run seamlessly across different computing platforms and by other researchers, thereby dramatically increasing interoperability [39].

Q: How can I make my benchmark's results interoperable for future meta-analyses? A: Provide the performance results (e.g., accuracy, runtime) in a structured, machine-readable format like JSON or CSV, rather than only within a PDF publication. Use standard column names and data types. This makes it easy for others to automatically extract and combine your results with those from other benchmarks [41].

Reusability Issues

Problem: Others can access my benchmark but cannot successfully reproduce or reuse it for their own research questions.

| Solution Component | Implementation Example | Tools & Standards |

|---|---|---|

| Clear Licensing | Attach an explicit software license (e.g., MIT, Apache 2.0) and data license to the workflow and its components. | Creative Commons, Open Source Licenses |

| Provenance Capture | Use a workflow system that automatically records the data lineage, including all parameters and software versions used. | RO-Crate, CWL Prov, WMS Provenance Features [40] |

| Comprehensive Documentation | Include a "README" with exact commands, example input data, and expected output. | Markdown, Jupyter Notebooks |

Q: I've provided my code and data. Why are users still reporting they can't reuse my benchmark? A: This is often due to missing computational context. You likely provided the "what" (code and data) but not the precise "how" (exact software environment). To enable reuse, you must document the complete software environment, ideally by using container images (e.g., Docker) and a workflow management system that captures the full provenance of each execution run [40] [41].

Q: What critical reusability information is most often overlooked? A: Licensing. Without a clear license, potential users have no legal permission to reuse and modify your workflow. Always include a license file specifying the terms of use for both the code (e.g., an open-source license) and the data (e.g., CCO, CC-BY). This is a foundational requirement for reusability [40].

Experimental Protocol: FAIRifying a Computational Benchmark

The following methodology outlines the steps to implement the FAIR principles for a computational biology tool benchmark, using a metabolomics workflow as a case study [39].

Workflow Definition and Containerization

- Define the Workflow: Implement the benchmark workflow using a standard workflow language such as the Common Workflow Language (CWL). This ensures the workflow is abstracted from a specific execution engine [39].

- Package Components: For each analytical step (e.g., a tool for differential expression analysis), create a Docker or Singularity container that encapsulates all necessary software dependencies, ensuring consistent execution across platforms [39].

Metadata Generation and Registration

- Create Structured Metadata: Generate a machine-readable metadata file describing the benchmark. Use the Workflow RO-Crate profile, which uses Bioschemas to structure information like name, creator, description, and input/output data types in JSON-LD format [39].