A Researcher's Guide to CRISPR gRNA Design Tools: Principles, Applications, and AI-Driven Advances

This article provides a comprehensive guide to CRISPR guide RNA (gRNA) design, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

A Researcher's Guide to CRISPR gRNA Design Tools: Principles, Applications, and AI-Driven Advances

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to CRISPR guide RNA (gRNA) design, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of gRNA design, including PAM requirements and key parameters like on-target efficiency and off-target risk. The guide explores methodological applications for diverse experiments such as gene knockout, knock-in, and gene modulation (CRISPRa/i), and offers troubleshooting and optimization strategies. Finally, it delivers a comparative analysis of current bioinformatics tools and validation techniques, highlighting the growing impact of artificial intelligence and machine learning in advancing precision genome editing for therapeutic development.

The Essential Guide to CRISPR gRNA Design: Core Principles and System Selection

The CRISPR-Cas system, a cornerstone of modern genome engineering, functions as a programmable complex capable of precise DNA manipulation. Its operational simplicity relies on the interplay between two fundamental components: the Cas protein, which acts as the molecular scissors, and the guide RNA (gRNA), which serves as a programmable homing device [1] [2]. The system's targeting specificity is further constrained by a short DNA sequence known as the protospacer adjacent motif (PAM), which is essential for the initiation of the editing process [2]. This application note details the structure and function of these core components, providing detailed protocols for their use within the context of advanced therapeutic development. The field is rapidly evolving, with recent advances including the use of large language models to design highly functional, AI-generated genome editors like OpenCRISPR-1, which exhibits comparable or improved activity and specificity relative to SpCas9 despite being 400 mutations away in sequence [3].

Guide RNA (gRNA) Structure and Design

The guide RNA is a synthetic fusion of two naturally occurring RNA molecules: the CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA) [2]. Its primary function is to direct the Cas nuclease to a specific genomic locus via Watson-Crick base pairing.

Architectural Components of a gRNA

A typical gRNA consists of two critical domains:

- Spacer Sequence: A 20-nucleotide custom-designed sequence located at the 5' end of the gRNA. It is complementary to the target DNA sequence and dictates the system's specificity [2].

- Scaffold (or Direct Repeat) Sequence: A conserved structural component that is responsible for binding the Cas nuclease protein. This scaffold is essential for the formation of the functional ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex [4] [2].

Table 1: Key Functional Regions within a gRNA Scaffold

| Region | Function | Importance for Cas9 Binding |

|---|---|---|

| Root Stem-loop | Forms a stable duplex | Critical for RNP complex formation and nuclease activation [4]. |

| Nexus Region | Links the root and the upper stem | Contributes to structural integrity. |

| Upper Stem-loop | Interacts with the PAM-interacting domain of Cas9 | Influences cleavage efficiency and specificity [4]. |

Advanced Design Considerations for Single-Nucleotide Fidelity

Achieving single-nucleotide specificity is paramount for diagnostic applications and for correcting point mutations in therapeutic contexts. Strategic gRNA design is critical to overcoming the inherent mismatch tolerance of Cas proteins.

- Seed Region: A 10-12 nucleotide segment proximal to the PAM sequence where mismatches are least tolerated. Designing gRNAs to place the single-nucleotide variant (SNV) of interest within this region enhances discrimination [4].

- Synthetic Mismatches: Intentionally introducing an additional mismatch in the spacer sequence, particularly near the SNV, can increase the penalty score for binding to the off-target sequence, thereby improving specificity. This strategy has been successfully applied in Cas13a-based diagnostics (SHERLOCK) [4].

- PAM (De)generation: For DNA-targeting Cas proteins, an SNV that creates or disrupts a PAM sequence can be leveraged for highly specific detection, as CRISPR function is entirely dependent on PAM presence [4].

Figure 1: Functional Anatomy of a Guide RNA and its Target. The gRNA is composed of a target-specific spacer and a structural scaffold. The seed region within the spacer and the PAM on the DNA are critical for specificity.

PAM Sequences: The Targeting Gatekeeper

The PAM is a short, specific DNA sequence (typically 2-6 base pairs) located immediately adjacent to the target DNA sequence. It serves as a recognition signal for the Cas protein, allowing it to distinguish between self (the bacterial CRISPR locus) and non-self (invading DNA) [4] [2].

PAM Diversity Across Cas Protein Variants

The PAM requirement is a primary differentiator among Cas proteins and dictates their targeting range. The sequence and strictness of the PAM vary significantly between orthologs and engineered variants.

Table 2: Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) Requirements for Selected Cas Proteins

| Cas Protein Variant | Origin / Type | PAM Sequence (5' → 3') | Implications for Targeting |

|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | Streptococcus pyogenes | NGG (where N is any nucleotide) | Restricts targeting to ~1/16th of the genome [2]. |

| ScCas9 | Streptococcus canis | NNG | Broader targeting range compared to SpCas9 [1]. |

| SaCas9 | Staphylococcus aureus | NNGRRT (or NNGRR) | More complex PAM, but small size is ideal for viral delivery [1]. |

| hfCas12Max | Engineered Cas12i (Type V) | TN | Very broad targeting range, enabling access to previously inaccessible genomic regions [1]. |

| eSpOT-ON (ePsCas9) | Engineered Parasutterella secunda Cas9 | NGAN or NGNG | Balanced PAM compatibility with high fidelity, suitable for therapeutics [1]. |

Cas Protein Variants: Expanding the Toolkit

While SpCas9 is the prototypical effector, its limitations—including size, PAM restriction, and off-target effects—have driven the discovery and engineering of a diverse array of alternatives [1].

Naturally Occurring and Engineered Variants

- SaCas9: Valued for its compact size (1053 amino acids), which facilitates packaging into adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors for in vivo gene therapy applications. It recognizes a NNGRRT PAM [1].

- hfCas12Max: An engineered high-fidelity variant derived from the Cas12 family. It creates staggered-end cuts, recognizes a simple TN PAM, and exhibits reduced off-target editing, making it a promising candidate for therapeutics [1].

- High-Fidelity eSpCas9(1.1) and Cas9-HF1: These engineered SpCas9 variants incorporate point mutations that reduce non-specific interactions with the DNA backbone, thereby increasing specificity without completely sacrificing on-target activity [2].

AI-Guided Discovery and Design

Traditional methods like directed evolution are being supplemented by artificial intelligence. Large language models (LMs) trained on massive datasets of CRISPR-Cas sequences can now generate novel, functional editors. For instance, models trained on the "CRISPR–Cas Atlas" (comprising over 1 million CRISPR operons) have generated Cas9-like proteins with an average of only 56.8% sequence identity to any known natural protein, yet these AI-designed editors (e.g., OpenCRISPR-1) show comparable or improved activity and specificity [3].

Integrated Experimental Protocol: gRNA Design and Validation for Knockout

This protocol outlines a robust workflow for designing and validating gRNAs for efficient gene knockout using the CRISPR-Cas9 system.

Stage 1:In SilicogRNA Design and Selection

Objective: To computationally identify high-efficiency, specific gRNAs for your gene of interest. Materials:

- Genomic sequence of the target gene (e.g., from UCSC Genome Browser).

- gRNA design tool (e.g., CRISPOR, CHOPCHOP, or CRISPRware [5] [6] [7]).

Procedure:

- Input Sequence: Obtain the cDNA or genomic DNA sequence of your target exon, preferably an early coding exon to maximize the chance of generating a frameshift mutation.

- Identify Candidate gRNAs: Use your chosen design tool to scan the input sequence for all possible gRNAs with the correct PAM (e.g., NGG for SpCas9).

- Rank by Efficiency Score: Filter candidates using algorithm-specific on-target efficiency scores (e.g., Doench '16 score, VBC score [8]). Select the top 3-5 candidates for further analysis.

- Evaluate Specificity: Use the tool's off-target analysis function to screen each candidate gRNA against the reference genome. Prioritize gRNAs with zero or minimal predicted off-target sites, especially those with few mismatches in the seed region.

- Final Selection: Choose at least 2-3 high-scoring gRNAs with the best predicted on-target efficiency and lowest off-target potential for experimental validation.

Stage 2: Experimental Validation of Editing Efficiency

Objective: To empirically test the selected gRNAs in your cell system. Materials:

- Cas9 expression vector (e.g., plasmid encoding SpCas9) or recombinant Cas9 protein.

- Synthesized gRNAs or gRNA expression vectors.

- Delivery reagent (e.g., lipofectamine, electroporation system).

- Target cells (cell line or primary cells).

- PCR reagents and genomic DNA extraction kit.

- T7 Endonuclease I or next-generation sequencing (NGS) assay kit [2].

Procedure:

- Delivery: Co-transfect your cells with the Cas9 nuclease and each of the candidate gRNAs. Include a non-targeting control gRNA.

- Harvest Genomic DNA: Extract genomic DNA 48-72 hours post-transfection.

- Amplify Target Locus: Design primers flanking the gRNA target site and perform PCR.

- Analyze Indel Frequency:

- T7 Endonuclease I Assay: Denature and reanneal the PCR products. The T7E1 enzyme cleaves heteroduplex DNA formed by wild-type and indel-containing strands. Analyze the cleavage products by gel electrophoresis to estimate editing efficiency [2].

- NGS-based Validation (Gold Standard): Sequence the PCR amplicons by NGS. Use computational tools (e.g., CRISPResso2) to precisely quantify the percentage of reads containing indels at the target site.

- Select the Most Effective gRNA: Proceed with the gRNA that demonstrates the highest on-target editing efficiency and minimal off-target activity in your validation assays.

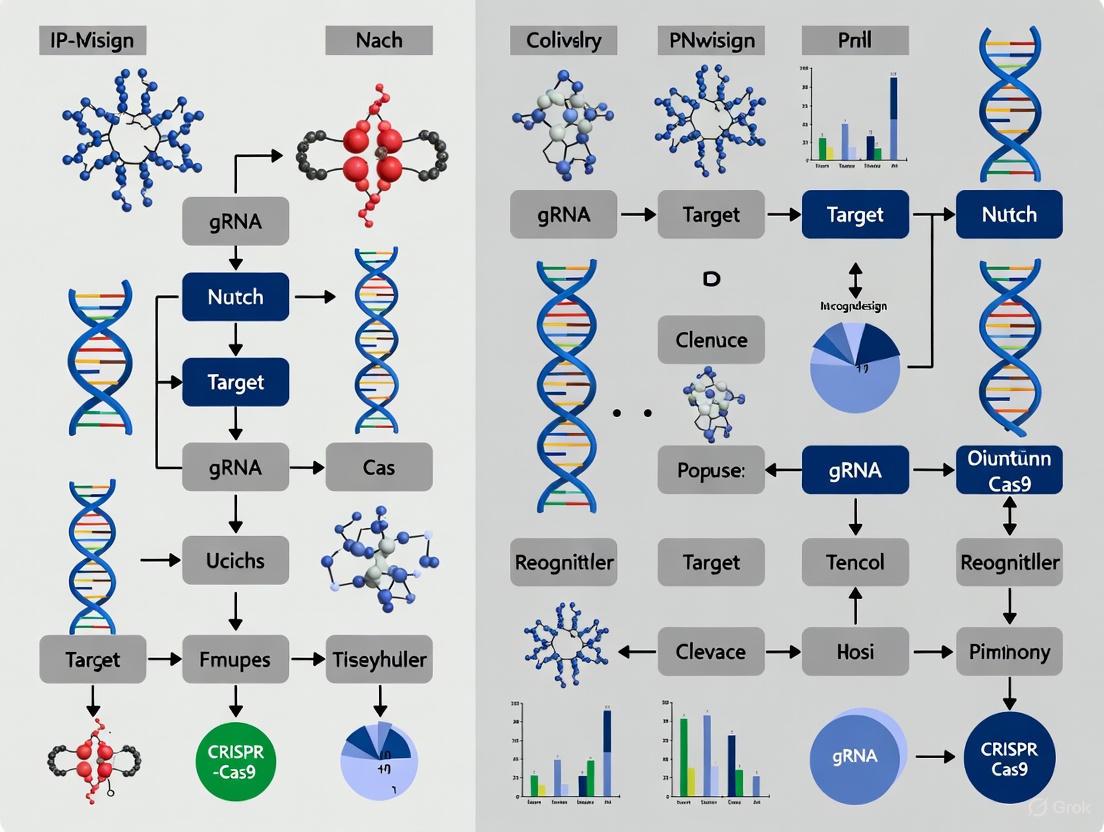

Figure 2: gRNA Design and Validation Workflow. A two-stage protocol from computational design to experimental validation ensures the selection of highly efficient and specific gRNAs.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

| Category | Item / Tool | Specific Function / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cas Nuclease Variants | hfCas12Max | High-fidelity, broad PAM (TN) targeting; small size for AAV delivery [1]. |

| eSpOT-ON (ePsCas9) | Engineered high-fidelity nuclease with robust on-target activity for clinical applications [1]. | |

| SaCas9 | Compact nuclease for in vivo delivery via AAVs; PAM: NNGRRT [1]. | |

| Computational Tools | CRISPRware | Designs gRNAs for any genomic region, integrated into the UCSC Genome Browser for accessibility [6]. |

| CRISPOR / CHOPCHOP | Versatile platforms for gRNA design with integrated off-target scoring and visualization [5] [7]. | |

| VBC Scoring Algorithm | Predicts gRNA efficacy; guides in top-VBC scores show strong depletion in lethality screens [8]. | |

| Screening Libraries | Vienna-single library | A minimal genome-wide human CRISPR library (3 guides/gene) with performance matching larger libraries, reducing cost and complexity [8]. |

| Vienna-dual library | A dual-targeting library that can enhance knockout efficiency, though may trigger a heightened DNA damage response [8]. | |

| Validation Assays | T7 Endonuclease I Assay | Fast, cost-effective method to detect indel mutations at the target locus [2]. |

| NGS-based Analysis | Gold-standard method for precise quantification of on-target editing and genome-wide off-target profiling. |

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated (Cas) system has emerged as the predominant technology for genome editing, enabling precise manipulation of specific target genes within an organism's genome [9] [10] [11]. The heart of this revolutionary technology lies in the guide RNA (gRNA), a short nucleic acid sequence that directs the Cas nuclease to a complementary genomic target. The design of this gRNA fundamentally determines the success of any CRISPR experiment, balancing two critical and often competing parameters: on-target efficiency (the ability to effectively edit the intended genomic locus) and off-target risk (the potential for unintended edits at similar sites throughout the genome) [11].

For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, optimizing this balance is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity. Off-target effects occur when the CRISPR system tolerates mismatches between the gRNA and DNA, leading to cleavage at unintended sites [9] [12]. These unintended edits can confound experimental results and, critically, pose significant safety risks in therapeutic contexts, including the potential activation of oncogenes [9] [12]. This Application Note details the key design parameters that govern this balance and provides validated protocols to aid in the design and testing of highly specific and efficient gRNAs.

Key Design Parameters and Computational Prediction

The performance of a gRNA is influenced by a constellation of interdependent factors. Understanding and optimizing these factors is the first step in achieving specific genome editing.

Sequence-Specific Determinants

The nucleotide sequence of the gRNA and its target site is a primary determinant of both activity and specificity.

- Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) Specificity: The Cas nuclease requires a specific short PAM sequence adjacent to the target site for recognition. The most common Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) recognizes a 5'-NGG-3' PAM [9] [10]. The stringency of PAM recognition influences off-target potential; nucleases with longer or more complex PAM sequences, such as SaCas9 (“NNGRRT”) or NmCas9 (“NNNNGATT”), generally have a reduced off-target risk simply because their PAM sites occur less frequently in the genome [9].

- Seed Region and Mismatch Tolerance: The "seed region," typically the 10-12 nucleotides proximal to the PAM, is crucial for specific recognition and cleavage [9]. Mismatches in this region are less tolerated and often prevent cleavage, whereas mismatches in the distal region (further from the PAM) are more tolerated and are a major contributor to off-target effects [9]. In fact, wild-type SpCas9 can tolerate between three and five base pair mismatches, leading to potential cleavage at dozens of off-target sites [12].

- gRNA Sequence Composition: Empirical data from large-scale screens has revealed nucleotide preferences that influence on-target efficiency. For example, guanines are preferred in the first two positions preceding the PAM, while thymines are disfavored within ±4 nucleotides surrounding the PAM [11]. The GC content of the gRNA is also critical; very low GC content can reduce binding stability, while very high GC content may promote off-target binding. A GC content between 40-60% is often recommended [12].

Computational Prediction Tools and Scores

To navigate these complex sequence rules, numerous computational tools have been developed that leverage machine learning to score gRNAs based on large experimental datasets [11] [13].

Table 1: Key Features of Advanced gRNA Design and Analysis Tools

| Tool / Algorithm | Primary Function | Key Features and Capabilities | Basis of Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rule Set 2 (Azimuth) [11] | On-target efficiency prediction | Uses a regression model to score guides; integrated into Broad Institute's GPP sgRNA Designer. | Sequence composition, position of target site within the gene. |

| CRISPRon [13] | On-target efficiency prediction | Deep learning framework that integrates gRNA sequence with epigenomic information (e.g., chromatin accessibility). | Sequence features and cellular context. |

| VBC Score [8] | On-target efficiency prediction | Used to design minimal, high-performance genome-wide libraries; top-scoring guides show strong depletion in essentiality screens. | Empirical data from lethality screens in cell lines. |

| Exorcise [14] | Guide re-annotation & validation | Re-annotates CRISPR libraries against a user-defined genome, correcting for mis-annotations and variant cell lines (e.g., cancer genomes). | BLAT alignment to a specified genome and exome. |

| Multitask Models [13] | Joint on/off-target prediction | Deep learning models that predict on-target efficacy and off-target cleavage simultaneously, revealing trade-offs. | Combined datasets for both activity and specificity. |

These tools have evolved from simple rule-based systems to sophisticated deep learning models. For instance, CRISPRon integrates sequence features with epigenomic information like chromatin accessibility to achieve more accurate efficiency rankings [13]. Furthermore, modern approaches are increasingly using multitask models that jointly predict on-target and off-target activity, allowing for a more holistic optimization of gRNA designs [13].

Experimental Protocols for Off-Target Assessment

Computational prediction must be coupled with experimental validation. The following protocols describe robust methods for identifying and quantifying off-target effects.

Protocol 1: Genome-Wide Off-Target Detection Using GUIDE-seq

GUIDE-seq (Genome-wide, Unbiased Identification of DSBs Enabled by sequencing) is a highly sensitive method for detecting off-target cleavage sites in living cells [9].

Principle: A short, double-stranded oligonucleotide tag is integrated into CRISPR-induced double-strand breaks (DSBs) in vivo. These tagged breaks are then enriched and sequenced, providing a genome-wide map of nuclease activity [9].

Materials:

- Cultured cells (e.g., HEK293T)

- CRISPR components (Cas9 expression plasmid, sgRNA expression plasmid)

- GUIDE-seq oligonucleotide duplex

- Transfection reagent

- Lysis buffer and DNA extraction kit

- PCR reagents and primers

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) library preparation kit

- NGS platform

Procedure:

- Co-transfection: Co-transfect cells with the Cas9 expression plasmid, sgRNA expression plasmid, and the GUIDE-seq oligonucleotide duplex using a standard transfection protocol.

- Genomic DNA Extraction: Allow editing to proceed for 48-72 hours. Harvest cells and extract genomic DNA using a commercial kit.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Shear the genomic DNA. Perform PCR to enrich for fragments containing the integrated tag and prepare an NGS library.

- Data Analysis: Map the sequencing reads to the reference genome and identify genomic locations with significant enrichment of the GUIDE-seq tag, which correspond to DSB sites.

Protocol 2: In Vitro Off-Target Analysis Using Digenome-seq

Digenome-seq (in vitro digestion of genomic DNA with Cas9 followed by sequencing) is a cell-free, genome-wide method for identifying off-target sites with high sensitivity [9].

Principle: Purified genomic DNA is digested in vitro with Cas9 nuclease complexed with a specific sgRNA. The resulting cleavage sites, which have identical 5' ends, are then identified by whole-genome sequencing and computational analysis [9].

Materials:

- Purified genomic DNA from target cells/organism

- Recombinant Cas9 nuclease

- In vitro-transcribed or synthetic sgRNA

- NGS library preparation kit

- NGS platform

- Computational pipeline for Digenome-seq analysis (e.g., as described in [9])

Procedure:

- In Vitro Cleavage: Incubate purified genomic DNA with the pre-complexed Cas9/sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) in an appropriate reaction buffer.

- Sequencing Library Preparation: Purify the digested DNA and construct a whole-genome sequencing library. A parallel library from untreated genomic DNA serves as a control.

- Sequencing and Analysis: Sequence both libraries and align reads to the reference genome. Use a Digenome-seq-specific algorithm to detect cleavage sites by identifying genomic positions with a sharp increase in sequencing read starts, indicating Cas9 cleavage.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the strategic process of gRNA design, from initial selection to experimental validation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Successful CRISPR experimentation relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The table below details key solutions for enhancing specificity and efficiency.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Optimized CRISPR Experiments

| Category | Item | Function and Rationale | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleases | High-Fidelity Cas9 (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) [9] | Engineered variants with reduced off-target activity by destabilizing non-specific interactions with DNA. | May trade some on-target efficiency for improved specificity. |

| Cas12a (Cpf1) [11] | Alternative nuclease with different PAM requirement (TTTV), offering an alternative targeting landscape and potentially different off-target profiles. | Useful for targeting AT-rich regions. | |

| Base Editors [10] [15] | Fusion proteins that chemically convert one base to another without creating a DSB, dramatically reducing indel-forming off-targets. | Can still cause off-target single-nucleotide changes in DNA or RNA. | |

| gRNA Format | Chemically Modified Synthetic sgRNA [12] | Incorporation of 2'-O-methyl and phosphorothioate analogs increases stability and can reduce off-target effects. | Ideal for RNP delivery; enhances editing efficiency in primary cells. |

| Truncated sgRNA (tru-gRNA) [9] | Shortening the guide sequence by 2-3 nucleotides at the 5' end increases specificity by reducing tolerance for mismatches. | Can lower on-target activity for some guides; requires testing. | |

| Dual gRNA Nickase [9] | Uses a Cas9 nickase (cuts one strand) with two adjacent gRNAs. A DSB is only formed when both single-strand nicks occur, improving specificity. | Requires design and delivery of two guides per locus. | |

| Delivery | Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complexes [12] | Direct delivery of pre-assembled Cas9 protein and gRNA. Limits exposure time, reducing off-target effects, and enables highly efficient editing. | The gold standard for many ex vivo applications, including clinical therapies. |

| Software | CRISPOR, Benchling, Synthego Design Tool [16] [12] [17] | Online platforms that integrate multiple scoring algorithms (e.g., Doench, CFD) for predicting on-target efficiency and off-target risk. | Essential for initial guide selection and prioritization. |

The strategic balance between on-target efficiency and off-target risk is a cornerstone of robust and reliable CRISPR experimental design. Achieving this balance requires a multi-faceted approach: leveraging advanced computational tools powered by machine learning for intelligent gRNA selection [11] [13], adopting high-fidelity editing systems like engineered Cas9 variants or base editors [9] [10], and employing rigorous experimental methods such as GUIDE-seq or Digenome-seq for comprehensive off-target profiling [9]. For researchers in drug development, this rigorous framework is not optional but imperative, forming the foundation for translating CRISPR technology from a powerful research tool into safe and effective human therapeutics. As the field progresses, the integration of artificial intelligence and deep learning will continue to refine our predictive capabilities, further enhancing the precision and safety of genome editing [15] [13].

The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated (Cas) system functions as an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes, protecting against invading bacteriophages through targeted cleavage of foreign DNA [18]. This natural defense mechanism has been repurposed as a revolutionary genome engineering tool that enables precise modifications across diverse species, including plants, animals, and human cells [18] [19]. The CRISPR system comprises two fundamental components: a Cas nuclease that creates double-strand breaks in DNA, and a guide RNA (gRNA) that directs the nuclease to a specific target sequence via complementary base pairing [1].

The simplicity and programmability of CRISPR systems have transformed genetic research and therapeutic development, offering significant advantages over previous gene-editing technologies [19]. Among the various CRISPR systems available, Cas9 and Cas12a represent two major nuclease families with distinct molecular mechanisms and applications [18]. Recent advances have further yielded high-fidelity variants engineered to enhance editing precision and reduce off-target effects [1]. This article provides a comprehensive comparison of these systems and outlines detailed experimental protocols for their implementation in research and drug discovery contexts.

Comparative Analysis of Cas Nucleases

Cas9: The Foundational Genome Editor

CRISPR-Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) serves as the foundational nuclease in genome editing applications. SpCas9 recognizes a 5'-NGG-3' protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence and creates blunt-ended double-strand breaks approximately 3-4 nucleotides upstream of the PAM site [18] [1]. The system requires two RNA components—CRISPR RNA (crRNA) and trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA)—which can be synthetically fused into a single guide RNA (sgRNA) for simplified experimental use [1]. While highly efficient, wild-type SpCas9 exhibits significant off-target activity due to toleration of non-canonical PAM sequences (e.g., NAG and NGA) and mismatches between the gRNA and target DNA [1].

Cas12a: Expanding Targeting Range and Creating Staggered Ends

CRISPR-Cas12a (formerly known as Cpf1) represents a distinct Class II Type V CRISPR system with several characteristics that differentiate it from Cas9. Unlike Cas9, Cas12a recognizes T-rich PAM sequences (5'-TTTV-3') and creates staggered DNA breaks with 4-5 nucleotide overhangs distal to the PAM recognition site [18]. Cas12a requires only a single crRNA molecule rather than the dual RNA system of Cas9, and its DNase activity cleaves both target DNA and non-specific single-stranded DNA following activation [20]. In comparative studies targeting the rice phytoene desaturase (OsPDS) gene, Lachnospiraceae bacterium ND2006 Cas12a (LbCas12a) demonstrated higher editing efficiency than wild-type SpCas9, producing deletions ranging from 2-20 bp without PAM loss [18].

High-Fidelity Variants: Enhancing Precision for Therapeutic Applications

To address limitations in precision and targeting flexibility, researchers have developed both naturally occurring and engineered high-fidelity nuclease variants:

- HiFi Cas9: A high-fidelity SpCas9 variant with reduced off-target cleavage while maintaining robust on-target activity [18].

- eSpOT-ON: An engineered Cas9 variant from Parasutterella secunda that achieves exceptionally low off-target editing while retaining high on-target efficiency through mutations in RuvC, WED, and PAM-interacting domains [1].

- hfCas12Max: An engineered Cas12i-based nuclease with enhanced editing efficiency, reduced off-target effects, and a broadened PAM recognition (5'-TN-3') that enables targeting of previously inaccessible genomic regions [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Key CRISPR Nuclease Characteristics

| Nuclease | PAM Sequence | Cleavage Pattern | Size (aa) | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 | 5'-NGG-3' | Blunt ends upstream of PAM | 1368 | High efficiency, widely validated | Basic research, knockout screens |

| SaCas9 | 5'-NNGRRT-3' | Blunt ends | 1053 | Compact size, AAV delivery | In vivo studies, gene therapy |

| LbCas12a | 5'-TTTV-3' | Staggered cuts downstream of PAM | ~1200 | Single crRNA, high efficiency | AT-rich targeting, multiplexing |

| HiFi Cas9 | 5'-NGG-3' | Blunt ends | 1368 | Reduced off-targets | Sensitive therapeutic applications |

| hfCas12Max | 5'-TN-3' | Staggered cuts | 1080 | Broad PAM, high fidelity | Therapeutic development, expanded targeting |

| eSpOT-ON | 5'-NGG-3' | Blunt ends | ~1300 | Low off-targets, maintained efficiency | Clinical applications, precision editing |

Experimental Protocols for CRISPR Screening

Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex Delivery for Plant Genome Editing

Application Note: RNP delivery enables transient editing without genomic integration of CRISPR components, minimizing off-target effects and bypassing cloning steps [18]. This protocol is optimized for rice embryo editing but can be adapted for other plant species.

Materials:

- Purified Cas nuclease (WT Cas9, HiFi Cas9, or LbCas12a)

- Chemically synthesized crRNAs with 20-21 nt targeting sequences

- Plasmid pCAMBIA1301 for selection

- 5-day-old mature seed-derived rice embryos

- Biolistic transformation equipment

Methodology:

- Design crRNAs targeting regions proximal to the start codon of your gene of interest with appropriate PAM sequences (NGG for Cas9, TTTV for Cas12a).

- Complex purified Cas protein with crRNAs at 3:1 molar ratio in nuclease-free buffer and incubate at room temperature for 15 minutes to form RNP complexes.

- Co-deliver RNP complexes with plasmid pCAMBIA1301 into rice embryos via biolistic transformation.

- Transfer embryos to selection media containing hygromycin and incubate for 2-3 weeks.

- Isolate genomic DNA from transformed calli and analyze editing efficiency by sequencing the target locus.

- For phenotyping, regenerate plants from edited calli and observe mutant phenotypes (e.g., albino for PDS knockout).

Validation: In the OsPDS model system, LbCas12a RNP complexes achieved higher mutagenesis frequency than Cas9 variants, with characteristic deletion patterns of 2-20 bp without PAM loss [18].

Pooled CRISPR Screening for Functional Genomics

Application Note: Pooled CRISPR screens enable genome-wide interrogation of gene function through negative or positive selection approaches, providing robust datasets for target identification and validation [21] [22].

Materials:

- Lentiviral sgRNA library (e.g., Brunello, GeCKO)

- Cas9-expressing cell line

- Selection agent (e.g., puromycin)

- Cytotoxic agent (for resistance screens)

- Next-generation sequencing platform

- Bioinformatics analysis tools (MAGeCK, CERES)

Methodology:

- Transduce Cas9-expressing cells with lentiviral sgRNA library at low MOI (0.3-0.5) to ensure single integration events.

- Select transduced cells with puromycin (1-5 μg/mL) for 3-7 days.

- Split cells into experimental and control arms (e.g., drug treatment vs. DMSO control).

- Culture cells for 14-21 population doublings to allow phenotypic manifestation.

- Harvest genomic DNA at multiple timepoints and amplify sgRNA barcodes with indexing primers.

- Sequence amplified products via NGS and quantify sgRNA abundance.

- Analyze data using specialized algorithms to identify significantly enriched or depleted sgRNAs.

Experimental Design Considerations:

- For negative selection screens (identifying essential genes), monitor sgRNA depletion over time in proliferating cells.

- For positive selection screens (identifying resistance genes), apply selective pressure and identify enriched sgRNAs.

- Include appropriate controls: non-targeting sgRNAs, essential gene targets, and replication (minimum n=3).

- For in vivo screens, transplant edited cells into immunodeficient mice and analyze tumor composition after development.

CRISPR-Based Diagnostic Application (SEEKER)

Application Note: The Search Enabled by Enzymatic Keyword Recognition (SEEKER) system leverages Cas12a's trans-cleavage activity to enable quantitative keyword searching in DNA data storage, demonstrating the expanding applications of CRISPR beyond genome editing [20].

Materials:

- LbCas12a or AsCas12a nuclease

- Custom crRNAs matching target keywords

- Single-stranded DNA fluorophore-quencher (ssDNA-FQ) reporters

- Target DNA sequences (e.g., encoded research abstracts)

- Microfluidic chip or 96-well plate

- Fluorescence plate reader

Methodology:

- Encode text data into DNA sequences using non-collision grouping coding to compress dictionary size.

- Design crRNAs complementary to keyword sequences of interest.

- Assemble reaction mixtures containing:

- Cas12a nuclease (50 nM)

- crRNA (60 nM)

- Target DNA (variable concentration)

- ssDNA-FQ reporter (500 nM)

- NEBuffer 2.1 (1X)

- Incubate reactions at 37°C and monitor fluorescence intensity in real-time (5-60 minutes).

- Calculate fluorescence growth rates, which are proportional to keyword frequency in the DNA sample.

- For parallel searching, array multiple crRNAs on a microfluidic chip with pre-stored CRISPR reactions.

Validation: SEEKER correctly identified keywords in 40 files with a background of approximately 8000 irrelevant terms, demonstrating high specificity and quantitative performance [20].

Bioinformatics Tools for Guide RNA Design and Analysis

Effective CRISPR experimentation depends on appropriate bioinformatics tools for guide design, off-target prediction, and data analysis. Key resources include:

- CHOPCHOP & CRISPOR: Versatile platforms for gRNA design that provide robust guide selection for multiple species, integrated off-target scoring, and genomic visualization [5] [23].

- BE-Designer & BE-Hive: Specialized tools for base editing guide design, supporting both ABE and CBE systems [23].

- CRISPResso & EditR: Analysis tools for evaluating editing efficiency from Sanger or next-generation sequencing data [23].

- MAGeCK: Computational workflow for analyzing CRISPR screening data to identify essential genes or drug resistance mechanisms [19] [22].

Table 2: Bioinformatics Tools for CRISPR Experimental Workflows

| Tool Category | Representative Tools | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Guide RNA Design | CHOPCHOP, CRISPOR, Benchling | gRNA selection and optimization | Off-target scoring, efficiency prediction, multi-species support |

| Base Editing Design | BE-Designer, BE-Hive, SpliceR | Design guides for ABE/CBE systems | Precision editing optimization, splice site targeting |

| Data Analysis | CRISPResso, EditR, MAGeCK | Analyze editing efficiency and screen hits | NGS data processing, statistical analysis, visualization |

| CRISPR Array Detection | CRISPRDetect, CRISPRidentify | Identify native CRISPR systems | Machine learning classification, array annotation |

| Off-target Prediction | Cas-OFFinder, CRISPOR | Predict potential off-target sites | Genome-wide scanning, mismatch tolerance evaluation |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Genome Editing

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes | Key Providers |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity Nucleases | Precision DNA cleavage with reduced off-target effects | hfCas12Max, eSpOT-ON, HiFi Cas9 offer improved specificity | Synthego, AstraZeneca |

| Synthetic Guide RNAs | Target-specific nuclease recruitment | Chemically modified gRNAs enhance stability and efficiency | Synthego, IDT |

| RNP Complexes | Transient editing without DNA integration | Ideal for reducing off-target effects in therapeutic applications | Prepared in-house from purified components |

| Lentiviral Libraries | Delivery of sgRNA pools for functional screens | Genome-wide and sub-library formats available | Addgene, Cellecta |

| Detection Reporters | Signal generation in diagnostic applications | ssDNA-FQ reporters for Cas12a trans-cleavage assays | Custom synthesis |

| Cell Line Engineering Tools | Create isogenic Cas9-expressing lines | Stable integration enables reproducible screening | CRISPR knockin mice, transgenic cell lines |

The expanding CRISPR toolkit, encompassing Cas9, Cas12a, and high-fidelity variants, provides researchers with versatile options for diverse genome editing applications. Selection of the appropriate nuclease depends on multiple factors, including PAM availability, desired editing pattern, delivery constraints, and precision requirements. The experimental protocols outlined herein—from RNP delivery in plants to pooled screening in mammalian cells and diagnostic applications—demonstrate the breadth of implementation possibilities. As CRISPR technology continues to evolve, integration of advanced bioinformatics tools and high-fidelity reagents will further enhance the precision and scope of genome engineering in both basic research and therapeutic development contexts.

How Experimental Goal Dictates gRNA Design Strategy

In CRISPR-based genome editing, the guide RNA (gRNA) serves as the molecular Global Positioning System that directs Cas nucleases to specific genomic locations. However, there is no universal "best" gRNA design—the optimal strategy is profoundly influenced by the experimental objective [24]. Whether the goal is complete gene knockout, precise nucleotide editing, or transcriptional modulation, each application demands distinct design considerations for gRNA location, sequence optimization, and off-target mitigation. This application note examines how different experimental goals in genome engineering dictate specific gRNA design strategies, providing researchers with structured frameworks for selecting appropriate design parameters based on their specific scientific objectives.

gRNA Design Fundamentals

The CRISPR-Cas9 system functions through a two-component complex where the gRNA confers sequence specificity by binding to complementary DNA regions, while the Cas nuclease executes DNA cleavage at sites adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence [17]. For Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), the most commonly used nuclease, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3' located immediately 3' of the target sequence [25]. Effective gRNA design must balance two primary considerations: on-target efficiency (achieving the intended modification) and specificity (minimizing off-target effects at similar genomic sites) [26].

The gRNA itself is typically a 20-nucleotide sequence complementary to the target DNA, though this can vary when using Cas9 orthologs or engineered variants [27] [24]. Beyond basic sequence complementarity, successful gRNA design must account for additional factors including genomic context, chromatin accessibility, epigenetic modifications, and the specific Cas nuclease being employed [15].

Application-Specific gRNA Design Strategies

Gene Knockout via NHEJ

Gene knockout strategies utilizing non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) represent the most straightforward CRISPR application, where the primary goal is to disrupt gene function by introducing frameshift mutations through small insertions or deletions (indels) [24].

Design Priorities: For knockout experiments, gRNA sequence optimization takes precedence over precise targeting location, provided the gRNA targets within the appropriate region of the gene [24]. The key objective is selecting highly active gRNAs while minimizing potential off-target effects.

Optimal Targeting Parameters:

- Target exonic regions essential for protein function, typically between 5-65% of the protein-coding sequence from the start codon

- Avoid regions near the N-terminus where alternative start codons might bypass the disruption

- Avoid C-terminal regions that might tolerate truncations without functional consequences

- Consider targeting conserved functional domains critical for protein activity

Implementation Protocol:

- Identify Target Region: Select a region 5-65% into the protein-coding sequence

- gRNA Selection: Use design tools (CHOPCHOP, E-CRISP, Benchling) to identify potential gRNAs with high predicted efficiency

- Specificity Screening: Filter candidates against off-target sites, prioritizing gRNAs with minimal similar sequences elsewhere in the genome

- Multi-guide Approach: Design 2-3 gRNAs targeting different regions of the gene to confirm phenotype consistency

Table 1: gRNA Design Parameters for NHEJ-Mediated Gene Knockout

| Parameter | Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Target Region | 5-65% of protein-coding sequence | Avoids alternative start sites and C-terminal truncations |

| PAM Requirement | NGG for SpCas9 | Cas9 nuclease specificity requirement |

| gRNA Length | 20 nucleotides | Standard complementarity region |

| Specificity Check | ≤3 mismatch sites in genome | Minimizes off-target activity |

| Validation | Multiple gRNAs per gene | Confirms on-target effects |

Precise Genome Editing via HDR

Precise editing using homology-directed repair (HDR) enables specific nucleotide changes or insertion of defined sequences, but presents greater design challenges due to efficiency constraints and locational constraints [24].

Design Priorities: For HDR experiments, targeting location is paramount—the Cas9 cleavage site must be within approximately 30 nucleotides of the intended edit [24]. This severe locational constraint often limits options for sequence-optimized gRNAs.

Critical Design Considerations:

- The cut site must be proximal to the edit (within ~30 bp) for effective HDR

- Consider alternative Cas enzymes with varied PAM requirements (SaCas9, NmeCas9, Cas12a) to expand targeting options

- For base editing, the target base must fall within the defined activity window (typically 5-10 nucleotides from the PAM)

- Design donor templates with homology arms (800 bp for plasmid donors, 100-400 nt for synthetic single-stranded templates) [25]

Implementation Protocol:

- Define Edit Location: Identify precise genomic coordinates for the desired modification

- PAM Identification: Locate available PAM sites within 30 nt of the edit site

- gRNA Selection: Identify all possible gRNAs near the edit, prioritizing those with minimal off-target sites

- Donor Design: Construct repair template with appropriate homology arms and modifications to disrupt PAM recognition after editing

- Validation Strategy: Plan for single-cell cloning and extensive genotyping, including potential reversion to confirm phenotype

Table 2: gRNA Design Parameters for HDR-Mediated Precise Editing

| Parameter | HDR Editing | Base Editing |

|---|---|---|

| Window from PAM | ≤30 nucleotides | 5-10 nucleotides |

| Edit Specificity | Defined by donor template | Defined by activity window |

| Bystander Edits | None | Possible with multiple target bases in window |

| Template Design | 800 bp homology arms (plasmid) | Not applicable |

| PAM Disruption | Critical to prevent re-cutting | Recommended |

Transcriptional Modulation (CRISPRa/i)

CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) and interference (CRISPRi) employ catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) fused to transcriptional effectors to modulate gene expression without altering DNA sequence [17] [24].

Design Priorities: For transcriptional modulation, gRNA location relative to the transcription start site (TSS) is equally important as sequence optimization [24]. Accurate TSS annotation is essential for success.

Position-Specific Requirements:

- CRISPRa: Target regions from -500 to -50 bp upstream of the TSS, with optimal activity around -100 bp upstream [17] [24]

- CRISPRi: Target regions from -50 to +300 bp relative to the TSS [17]

- For CRISPRi, avoid nucleosome-bound regions and target the template or non-template strand with similar efficacy in eukaryotic systems [17]

Implementation Protocol:

- TSS Annotation: Use FANTOM CAGE-seq data for precise TSS mapping [24]

- Target Window Identification: Define the appropriate targeting window based on application (activation vs. interference)

- gRNA Selection: Identify all possible gRNAs within the target window

- Efficiency Screening: Filter gRNAs using predictive algorithms, though these are less established for CRISPRa compared to cutting applications [17]

- Multi-guide Approach: Implement 2-3 gRNAs per gene to enhance efficacy

Table 3: gRNA Design Parameters for Transcriptional Modulation

| Parameter | CRISPRa | CRISPRi |

|---|---|---|

| Target Window | -500 to -50 bp from TSS | -50 to +300 bp from TSS |

| Optimal Position | ~100 bp upstream of TSS | Near TSS |

| Strand Preference | Either strand | Either strand (eukaryotes) |

| Chromatin Effects | Moderate impact | High impact (avoid nucleosomes) |

| Baseline Expression | More effective on low-expression genes | Works across expression levels |

Specialized Design Considerations

Addressing Off-Target Effects

Off-target activity remains a significant concern in CRISPR applications, particularly for therapeutic development. Multiple strategies have been developed to mitigate this risk:

Computational Prediction: Tools like Cas-OFFinder and E-CRISP identify potential off-target sites based on sequence similarity, focusing on sites with minimal mismatches, particularly in the PAM-distal region [26] [28].

Experimental Detection: Methods including GUIDE-seq, BLESS, and Digenome-seq provide genome-wide identification of off-target sites through different mechanistic approaches [26].

Nuclease Engineering: Enhanced specificity Cas9 variants (e.g., eSpCas9, SpCas9-HF1) with reduced off-target activity while maintaining on-target efficiency [26].

Species-Specific and Context-Specific Design

gRNA design rules are not universally applicable across biological contexts. Polyploid organisms like wheat (hexaploid) present additional challenges due to the presence of homeologs with high sequence similarity [27]. In such cases, designers must either:

- Target conserved regions across all homeologs

- Design specific gRNAs to selectively edit individual homeologs

- Conduct comprehensive off-target analysis against all sub-genomes

Chromatin accessibility and epigenetic modifications also significantly impact gRNA efficiency, particularly for CRISPRa/i applications where binding (without cleavage) is sufficient for activity [17].

Experimental Validation and Analysis

Following gRNA design and implementation, comprehensive validation of editing outcomes is essential across all application types.

Next-Generation Sequencing: The gold standard for validation, NGS provides comprehensive characterization of editing efficiency and specificity, but requires substantial resources and bioinformatic support [29].

Sanger Sequencing with Computational Analysis: Tools like Synthego's ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) use Sanger sequencing data to quantify editing efficiency and identify specific indel patterns, offering a accessible alternative to NGS with high accuracy (R² = 0.96 compared to NGS) [29].

Rapid Screening Methods: The T7 Endonuclease 1 (T7E1) assay detects the presence of mutations through mismatch cleavage but provides limited quantitative data and no sequence-level information [29].

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is rapidly advancing gRNA design capabilities. AI models like DeepXE now demonstrate >90% sensitivity in predicting editing efficiency for novel editors [30]. Structural prediction tools including AlphaFold 3 enable protein-based gRNA design by modeling biomolecular interactions [15]. These computational advances are complemented by the discovery of novel editing systems such as prime editing, base editing, and CRISPR-associated integrases that expand the targeting scope and editing capabilities beyond standard Cas9 systems [15] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for CRISPR gRNA Design and Implementation

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SpCas9 Nuclease | DNA cleavage at target sites | Most widely characterized; NGG PAM |

| dCas9 Effector Fusions | Transcriptional modulation | CRISPRa/i applications |

| CHOPCHOP | gRNA design tool | Multi-species support; efficiency scoring |

| CRISPR-ERA | gRNA design for repression/activation | Specialized for CRISPRa/i |

| ICE Analysis | Editing efficiency quantification | From Sanger sequencing; NGS-comparable |

| Bxb1 Serine Integrase | Large DNA integration | Protein-guided; no target sequence needed |

| Prime Editor Components | Search-and-replace editing | No double-strand breaks; versatile editing |

Visual Guide: gRNA Design Strategy Selection

gRNA Design Strategy Selection

This workflow illustrates the decision process for selecting appropriate gRNA design parameters based on experimental goals, highlighting the different priorities and tools for each major application type.

The strategic design of gRNAs is fundamentally guided by experimental objectives, with distinct optimization parameters for gene knockout, precise editing, and transcriptional modulation applications. Successful implementation requires careful consideration of both targeting location and sequence efficiency, balanced with appropriate off-target mitigation strategies. As CRISPR technologies continue to evolve toward therapeutic applications, the integration of AI-driven design tools and novel editing systems will further enhance our ability to precisely control genomic outcomes through optimized gRNA design. Researchers should adopt a flexible framework that aligns gRNA selection with specific experimental goals while implementing appropriate validation methodologies to confirm intended editing outcomes.

From Theory to Bench: A Practical Workflow for gRNA Design in Key Applications

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has revolutionized genetic engineering by providing researchers with an efficient and programmable method for targeted gene knockout. This technology leverages a two-component system consisting of the Cas9 nuclease and a guide RNA (gRNA) that directs the nuclease to specific genomic loci [31]. When designing gRNAs for gene knockout applications, the primary goal is to introduce frameshift mutations that disrupt the coding sequence of the target gene, ultimately leading to loss of protein function. The process relies on the cell's endogenous DNA repair mechanisms, particularly the error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway, which frequently results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the site of Cas9-mediated double-strand breaks [31] [32]. These indels, when occurring within exons, can disrupt the reading frame and introduce premature stop codons, effectively knocking out the target gene.

The design of the gRNA plays a crucial role in determining the success of knockout experiments, as both the location within the gene and the sequence characteristics of the gRNA directly impact editing efficiency and specificity [17] [16]. This protocol focuses specifically on the strategic design of gRNAs to maximize knockout efficiency through targeted frameshift mutations in critical exonic regions, framed within the broader context of CRISPR guide RNA design tool research for therapeutic development and basic biological investigation.

Critical Design Parameters for Knockout gRNAs

Target Site Location Within Gene Structure

The positioning of gRNA target sites within the gene architecture is a fundamental consideration for effective knockout generation. Not all regions of a protein-coding gene are equally suitable for generating complete loss-of-function alleles. The following strategic placement guidelines should be observed:

Target common exons: Prioritize exons that are shared across all or most transcript variants of the target gene to ensure comprehensive knockout across different isoforms [17]. This approach is particularly important for genes with complex alternative splicing patterns, as targeting unique exons might only affect specific variants while leaving others functional.

Avoid terminal protein regions: Target sites should be located sufficiently distant from both the start and stop codons to prevent the potential use of alternative start sites or the production of partially functional truncated proteins [16]. When cuts are made too close to the N-terminus, cells may potentially find another start codon (ATG) downstream, while targets near the C-terminus might code for non-essential protein regions that could retain functionality even after editing.

Focus on essential protein domains: When structural or functional information about the target protein is available, prioritize gRNAs that target exons encoding critical functional domains. This strategy provides an additional safeguard to ensure complete loss of function, even if in-frame indels occur that might otherwise preserve partial activity.

The optimal target region generally falls within the 5' portion of the coding sequence, typically in early exons, but sufficiently downstream of the start codon to avoid alternative translation initiation events.

gRNA Sequence Considerations

Beyond genomic positioning, the nucleotide composition of the gRNA itself significantly influences both on-target efficiency and off-target potential. The following sequence parameters should be optimized during design:

GC content: Maintain GC content between 40-80% for optimal gRNA stability and activity [33]. gRNAs with extremely low GC content may exhibit poor binding stability, while those with very high GC content might have increased off-target potential due to enhanced stability at partially matched sites.

Seed sequence integrity: The 8-12 nucleotides immediately adjacent to the Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence, known as the "seed" region, are critical for target recognition and cleavage [31]. Mismatches in this region significantly reduce or eliminate cleavage activity, making it essential to ensure perfect complementarity in the seed region for the intended target.

Avoid polymorphic regions: Verify that target sequences do not contain single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the population or model system being studied, as these can drastically reduce editing efficiency for some individuals or cell lines.

Promoter compatibility: When expressing gRNAs from U6 promoters, which typically require a G as the first transcription nucleotide, ensure compatibility between the target sequence and promoter requirements [34]. Recent evidence suggests that both human and mouse U6 promoters can initiate transcription with A or G, expanding design flexibility [34].

Table 1: Key Parameters for Optimal gRNA Design

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Rationale | Design Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Location | Central coding exons | Avoids alternative start sites and non-essential terminal domains | Increases likelihood of complete loss-of-function |

| GC Content | 40-80% | Balanced stability and specificity | Preforms gRNA structure without excessive binding energy |

| Seed Region | No mismatches | Critical for recognition and cleavage initiation | Essential for on-target activity |

| Distance from PAM | ~3-4 nucleotides upstream | Determines cleavage position | Consistent spacing for predictable indel patterns |

Frameshift Optimization Strategies

The ultimate goal in knockout experiments is to introduce frameshift mutations that disrupt the protein coding sequence. Several strategies can enhance the probability of achieving this outcome:

Multiple gRNA approach: Designing two or more gRNAs targeting the same gene can dramatically increase knockout efficiency by increasing the probability that at least one target site will be successfully edited, and by potentially generating larger deletions when dual cuts occur [16]. This approach is particularly valuable for genes where individual gRNAs show variable efficiency.

In-frame mutation consideration: Although NHEJ typically produces indels of varying lengths, approximately two-thirds of 3n+1 or 3n+2 indels will produce frameshifts. Some computational tools, such as Lindel, can predict the likelihood of frameshift-inducing mutations based on sequence context, allowing for more informed gRNA selection [35].

Exon size considerations: For particularly small exons, consider designing gRNAs that target nearby splice sites or adjacent exons to ensure disruption of the coding sequence, as small in-frame deletions within a single exon might not always disrupt protein function.

Computational Design and Scoring Algorithms

On-Target Efficiency Prediction

Several sophisticated algorithms have been developed to predict gRNA on-target efficiency based on large-scale experimental datasets. These scoring systems evaluate sequence features correlated with high editing activity:

Rule Set 2: Developed by Doench et al. in 2016, this algorithm uses gradient-boosted regression trees trained on data from over 43,000 gRNAs to predict cleavage efficiency [35]. It considers sequence features including nucleotide composition, position-specific parameters, and structural accessibility.

Rule Set 3: An updated version published in 2022 that incorporates the tracrRNA sequence into the model and was trained on approximately 47,000 gRNAs across seven existing datasets [35]. This model offers improved accuracy, particularly for non-standard gRNA scaffolds.

CRISPRscan: This predictive model was developed based on activity data of 1,280 gRNAs validated in vivo in zebrafish, capturing species-specific and context-dependent factors that influence editing efficiency [35].

DeepHF: A deep learning-based approach that combines recurrent neural networks with important biological features to predict gRNA activity for wild-type SpCas9 and high-fidelity variants eSpCas9(1.1) and SpCas9-HF1 [34].

These algorithms typically analyze a 30-nucleotide sequence encompassing the 20-nucleotide gRNA binding region, the PAM sequence, and immediate flanking genomic sequence to generate efficiency scores that help prioritize gRNAs with the highest predicted activity.

Off-Target Risk Assessment

Minimizing off-target effects is crucial for specific genome editing, particularly in therapeutic applications. Several computational methods have been developed to assess and quantify off-target potential:

Cutting Frequency Determination (CFD) score: Developed in Doench's 2016 study, this scoring method uses a position-weighted matrix based on the activity of 28,000 gRNAs with single nucleotide variations [35]. The CFD score multiplies individual mismatch weights, with lower scores indicating reduced off-target risk. A threshold of 0.05 or lower is typically considered low risk.

MIT specificity score: Also known as the Hsu score, this method was developed based on data from over 700 gRNA variants with 1-3 mismatches [35]. It provides a comprehensive off-target assessment by considering all potential off-target sites with up to a specified number of mismatches throughout the genome.

Homology analysis: Basic off-target assessment involves genome-wide searches for sequences similar to the gRNA that also contain appropriate PAM sequences [35]. Sequences with fewer than three mismatches, particularly in the seed region, should be carefully evaluated, with priority given to gRNAs that have minimal near-identical matches elsewhere in the genome.

Table 2: Comparison of gRNA Design Tools and Their Features

| Tool | On-Target Scoring | Off-Target Scoring | Special Features | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPick | Rule Set 2/3 | CFD score | Integrated with Broad Institute pipelines | High-throughput screening designs |

| CHOPCHOP | Multiple algorithms | Homology analysis | Supports multiple Cas nucleases and organisms | Versatile experimental designs |

| CRISPOR | Rule Set 2, CRISPRscan | MIT, CFD scores | Detailed off-target analysis with enzyme sites | Precision editing with validation support |

| Synthego Tool | Proprietary algorithm | Proprietary algorithm | Integrated ordering and validation | Rapid knockout design and implementation |

| DeepHF | Deep learning | Not specified | Optimized for high-fidelity Cas9 variants | Applications requiring maximal specificity |

Experimental Protocol for gRNA Design and Validation

gRNA Design Workflow

The following step-by-step protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for designing and validating gRNAs for gene knockout experiments:

Detailed Methodology

Target Gene Analysis

- Retrieve all known transcript variants of the target gene from databases such as Ensembl or NCBI RefSeq.

- Identify exons common to all or the majority of transcript variants using sequence alignment tools.

- Note the coding sequence coordinates and protein domain structure to prioritize functionally critical regions.

gRNA Candidate Generation

- Scan the selected exonic regions for canonical PAM sequences (5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9) using computational tools.

- Extract the 20 nucleotides immediately upstream of each PAM site as potential gRNA spacer sequences.

- Exclude gRNAs with TTTT sequences (potential polymerase III termination signals) and those spanning known SNPs.

Computational Screening and Prioritization

- Input candidate gRNA sequences into multiple design tools (e.g., CRISPick, CHOPCHOP, CRISPOR) to obtain consensus efficiency predictions.

- Prioritize gRNAs with high on-target scores (typically >0.6 using Rule Set 2 or similar metrics).

- Conduct comprehensive off-target analysis, paying particular attention to sites with ≤3 mismatches, especially those with mismatches in the PAM-distal region.

- Cross-reference off-target sites with gene annotations to avoid unintended disruption of coding regions, particularly for genes with similar biological functions to your target.

Experimental Validation

- Synthesize or clone the top 3-5 ranked gRNAs based on the combined on-target and off-target assessments.

- Deliver gRNAs with Cas9 to target cells using appropriate methods (lipofection, electroporation, or viral delivery).

- Harvest genomic DNA 72-96 hours post-transfection and amplify the target region by PCR.

- Assess editing efficiency using T7 endonuclease I assay or Tracking of Indels by Decomposition (TIDE) analysis, or by next-generation sequencing for more quantitative measurement.

- Validate knockout at the protein level by Western blot or flow cytometry when suitable antibodies are available.

Advanced Strategies and Troubleshooting

High-Fidelity Cas9 Variants

For applications requiring exceptional specificity, such as therapeutic development, consider using high-fidelity Cas9 variants that have been engineered to reduce off-target effects:

eSpCas9(1.1): Engineered to weaken non-specific interactions between Cas9 and the DNA substrate, reducing off-target cleavage while maintaining robust on-target activity [34].

SpCas9-HF1: Contains alterations that disrupt Cas9's interactions with the DNA phosphate backbone, enhancing discrimination against mismatched targets [34].

HypaCas9: Designed to increase Cas9 proofreading and discrimination capabilities through structure-guided engineering [31].

evoCas9 and Sniper-Cas9: Developed through directed evolution approaches to decrease off-target effects while maintaining high on-target activity [31].

These high-fidelity variants are particularly valuable when working with gRNAs that have moderate off-target risks or in sensitive applications where complete specificity is paramount.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR Knockout Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Expression Systems | SpCas9 expression plasmids, mRNA, or protein | Provides the nuclease component | Delivery method impacts kinetics and persistence |

| gRNA Format Options | Plasmid vectors, synthetic sgRNA, IVT RNA | Directs Cas9 to target sequence | Synthetic sgRNAs offer rapid deployment and reduced off-target persistence |

| Delivery Methods | Lipofection reagents, electroporation systems, viral vectors | Introduces CRISPR components into cells | Method affects efficiency, toxicity, and editing window |

| Validation Tools | T7E1 enzyme, ICE analysis tool, NGS platforms | Assesses editing efficiency and specificity | Sensitivity varies between methods |

| Control gRNAs | Validated positive control gRNAs, non-targeting controls | Experimental quality assessment | Essential for protocol optimization and troubleshooting |

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Low editing efficiency: Consider alternative gRNAs with higher predicted scores, optimize delivery methods, increase reagent concentrations, or try different Cas9 formats (e.g., ribonucleoprotein complexes).

Incomplete knockout: Implement multiple gRNAs targeting the same gene, use hybrid approaches combining CRISPR with RNA interference, or employ selective pressure to enrich for edited cells.

Unexpected phenotypic outcomes: Conduct comprehensive off-target assessment using GUIDE-seq or similar unbiased methods, and validate phenotype with multiple independent gRNAs to confirm on-target effects.

Cell toxicity: Reduce CRISPR component concentrations, switch to high-fidelity Cas9 variants, or use transient delivery methods rather than stable expression.

Effective design of gRNAs for gene knockouts requires integrated consideration of target location within critical exons, optimization of gRNA sequence parameters, and thorough computational assessment of both on-target efficiency and off-target risks. By following the systematic approach outlined in this protocol—prioritizing common exons away from terminal regions, leveraging established scoring algorithms, and implementing appropriate validation strategies—researchers can significantly enhance their success in generating complete gene knockouts. The continued development of more sophisticated design tools and high-fidelity CRISPR systems will further improve the precision and reliability of gene knockout approaches for both basic research and therapeutic applications.

Within the broader context of CRISPR guide RNA design tools research, achieving precise genetic modifications via knock-in is a paramount objective in advanced genome engineering. Precise knock-ins facilitate the creation of sophisticated disease models, the development of cell therapies, and the functional analysis of genes, playing a critical role in both basic research and therapeutic drug development [36] [37]. Unlike knockout strategies that disrupt gene function through non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), knock-in mutations require the more sophisticated homology-directed repair (HDR) pathway to incorporate an exogenous DNA template at a specific genomic location [16] [36]. The efficiency of this process is heavily influenced by two interdependent factors: the strategic design of the HDR donor template and the proximity of the CRISPR-induced double-strand break (DSB) to the intended integration site. This application note details validated protocols and design strategies to optimize these critical parameters for successful precise genome editing.

Core Mechanism: HDR in CRISPR-Mediated Knock-In

The fundamental mechanism for CRISPR knock-in involves directing the cell's native HDR machinery to repair a programmed double-strand break using a supplied donor DNA template. The Cas9 nuclease, guided by a single-guide RNA (sgRNA), creates a DSB at a predefined genomic locus [38] [36]. When a donor template with homologous ends (homology arms) is present, the cell can use this template for repair, thereby copying the desired genetic alteration—such as a gene insertion, a point mutation, or a fluorescent tag—into the genome [36] [37]. A significant challenge is that the HDR pathway competes with the more error-prone and efficient NHEJ pathway, which is active throughout the cell cycle and often results in indel mutations without template integration [37]. Therefore, experimental design must prioritize strategies that favor HDR over NHEJ.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key molecular components involved in a successful HDR-mediated knock-in.

HDR Donor Template Design Parameters

The donor template is a critical component for HDR, and its design must be carefully considered. Key variables include the template type, the length of the homology arms, and the specific sequence modifications.

Template Type Selection and Applications

The choice between single-stranded oligodeoxynucleotides (ssODNs) and double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) templates is primarily determined by the size of the intended insertion, with each format offering distinct advantages and limitations [38] [37] [39].

Table 1: HDR Donor Template Types and Their Applications

| Template Type | Ideal Insert Size | Homology Arm Length | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Stranded DNA (ssODN) | 1 bp - 100 bp [40] [39] | 50 - 100 nt [37] | High precision; lower cytotoxicity [37] | SNP introduction [36], small tags, short sequence insertions [38] |

| Double-Stranded DNA (dsDNA) | Up to 20 kb [40] | Several hundred bp [37] | Large cargo capacity; suitable for large inserts [37] | Insertion of fluorescent reporters (e.g., EGFP, mKate2) [38], coding sequences like CARs [39] |

Homology Arm Design

Homology arms are sequences flanking the insert that are identical to the genomic regions surrounding the cut site. They are essential for guiding the HDR machinery. While ssODNs typically use shorter arms (50-100 nucleotides), dsDNA templates require longer arms (several hundred base pairs) to support efficient recombination [38] [37]. Tools like the Alt-R CRISPR HDR Design Tool and GenCRISPR HDR Template Design Tool can automatically optimize homology arm design based on the chosen template and target site [40] [41].

The Critical Link: gRNA Cutting Site Proximity

For HDR to occur efficiently, the Cas9-induced double-strand break must be located very close to the site where the new sequence is to be inserted. As noted in the search results, "studies have shown a dramatic drop in efficiency of knock-in experiment when the cut site was not close to ends of the repair template" [16]. This locational constraint is a primary limiting factor in gRNA design for knock-ins, sometimes requiring researchers to prioritize proximity over perfect on-target activity scores [16]. The gRNA must be selected to create a DSB immediately adjacent to the genomic location intended for the modification encoded in the donor template's homology arms.

Integrated Experimental Protocol for HDR Knock-In

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for executing a CRISPR knock-in experiment, integrating design, delivery, and validation.

Protocol Workflow

The entire process, from initial design to final validation, is visualized in the following experimental workflow.

Detailed Methodology

Step 1: Design gRNA and HDR Donor Template

- gRNA Design: Use a specialized CRISPR design tool (e.g., Benchling, IDT's Alt-R HDR Design Tool, GenCRISPR) [40] [41]. Input the target gene and species. From the list of potential gRNAs, select one where the predicted cut site (typically 3 bp upstream of the PAM sequence for SpCas9) is within 10 base pairs of the intended edit site to maximize HDR efficiency [16]. Analyze the candidate for high on-target and low off-target scores [42].

- HDR Template Design: Using the same platform, input the desired edit sequence (e.g., SNP, GFP tag). Select the template type (ssODN or dsDNA) based on the size of the insertion (refer to Table 1). The design tool will automatically generate the final template sequence with optimized homology arms [40] [41]. For dsDNA plasmids, consider designs that self-cleave to release the insert from the bacterial backbone, which can improve HDR efficiency [37].

Step 2: Synthesize and Prepare Components

- CRISPR Components: Synthesize the selected sgRNA and procure or produce high-quality Cas9 protein (for RNP formation) or mRNA [37].

- HDR Donor Template: Order the designed template from a reputable supplier. For ssODNs, scales of 50-100 nmol are typical for initial experiments. For dsDNA, use high-purity kits or services to produce linearized fragments or specialty products like GenCircle dsDNA, which lacks a bacterial backbone for reduced cytotoxicity and higher knock-in efficiency [39].

Step 3: Co-Deliver Components into Target Cells

- Delivery Method: Choose an efficient delivery method suitable for your cell type.

- Electroporation: Highly effective for hard-to-transfect cells like primary T cells. Co-deliver CRISPR RNP complexes with the HDR donor template [39].

- Lipofection: Use lipid nanoparticles for standard cell lines.

- Viral Delivery: Consider AAV vectors for their high transduction efficiency, but be mindful of potential prolonged Cas9 expression [37].

- HDR Enhancement: To increase the fraction of HDR-mediated repair, add an HDR enhancer molecule like IDT's HDR Enhancer v2 or SCR7 during transfection. These compounds can inhibit the NHEJ pathway, thereby favoring HDR and potentially yielding a 2-5 fold increase in knock-in efficiency [37].

Step 4: Enrich and Culture Edited Cells

- After delivery, culture the cells under optimal conditions. If the HDR template contains a selectable marker (e.g., an antibiotic resistance gene or a fluorescent reporter), begin the appropriate selection 48-72 hours post-transfection.

Step 5: Validate Precise Editing

- Genotypic Validation: Extract genomic DNA from the enriched cell population. Perform PCR amplification across the modified genomic locus and subject the product to Sanger sequencing to confirm the precise integration of the desired sequence and the absence of random indels [23] [37].

- Advanced Analysis: For a quantitative assessment of editing efficiency in a mixed population, or to detect low-frequency off-target effects, use next-generation sequencing (NGS) and analysis tools like CRISPResso2 [23].

Optimization Strategies for Enhanced HDR Efficiency

- Cell Cycle Synchronization: HDR is most active in the S and G2 phases of the cell cycle [36]. Synchronizing cells to these phases prior to editing can improve knock-in rates.

- CRISPR Component Formulation: Delivery of pre-assembled CRISPR Ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) is superior to plasmid DNA for reducing off-target effects and enabling rapid, high-efficiency editing with minimal cytotoxicity [37].

- Template Engineering: Covalently tethering the donor DNA template to the Cas9 RNP complex has been shown in studies to significantly increase HDR efficiency by ensuring the template is physically present at the DSB site [37].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A successful knock-in experiment relies on a suite of specialized reagents and design tools. The following table catalogs key solutions and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for CRISPR Knock-In

| Reagent / Tool Category | Example Products | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| HDR Donor Templates | GenExact ssDNA [39], GenWand dsDNA [39], Alt-R HDR Donor Oligos [41] | High-quality, sequence-verified donor templates in various formats (ssDNA, linear dsDNA) for maximizing HDR efficiency. |

| CRISPR Design Platforms | Benchling [16] [42], IDT Alt-R HDR Design Tool [41], GenCRISPR [40], CHOPCHOP [42] | Integrated bioinformatics tools for designing and scoring gRNAs with optimized on-target activity and minimal off-target effects, often with integrated HDR template design. |

| HDR Enhancement Reagents | IDT HDR Enhancer v2 [36], SCR7 [37] | Small molecule inhibitors of the NHEJ pathway that shift the cellular repair balance towards HDR, increasing knock-in rates. |

| Delivery & Validation Tools | Electroporation Systems, Lipofection Kits, ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) Analysis Tool [23], CRISPResso2 [23] | Physical delivery methods for CRISPR components and software for analyzing Sanger or NGS data to quantify editing efficiency and precision. |

CRISPR-Cas9 has evolved from a simple genome-editing tool into a versatile platform for precise transcriptional regulation. Technologies known as CRISPR activation (CRISPRa) and CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) enable researchers to manipulate gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence. Both systems utilize a catalytically dead Cas9 (dCas9) that lacks endonuclease activity but retains its ability to bind specific DNA sequences guided by a single guide RNA (sgRNA). In CRISPRa, dCas9 is fused to transcriptional activators, leading to gene upregulation, while in CRISPRi, dCas9 is fused to repressors, resulting in gene downregulation [43] [44].