AI in Biology: Revolutionizing Discovery from Proteins to Precision Medicine

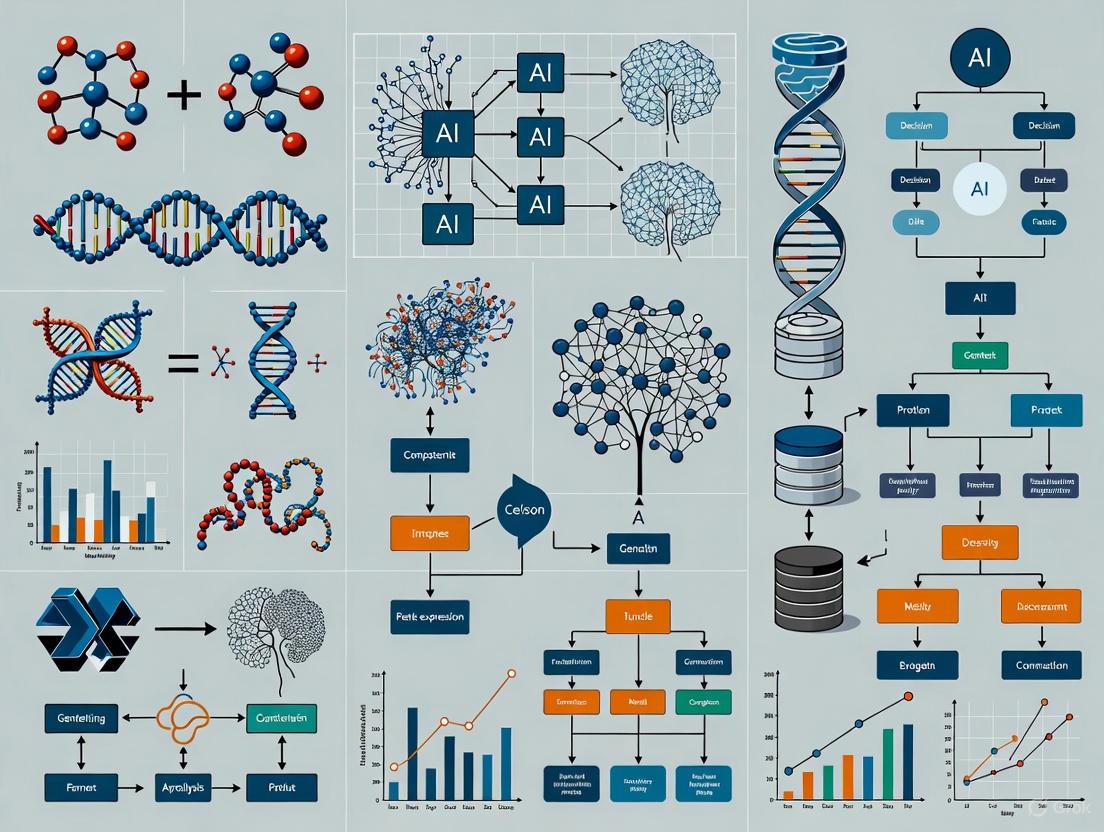

Artificial intelligence is fundamentally restructuring research paradigms across the biological sciences, enabling a shift from experience-driven to data-algorithm symbiosis.

AI in Biology: Revolutionizing Discovery from Proteins to Precision Medicine

Abstract

Artificial intelligence is fundamentally restructuring research paradigms across the biological sciences, enabling a shift from experience-driven to data-algorithm symbiosis. This article synthesizes the current state of AI applications in biology, from foundational models for protein design and genomic interpretation to practical advances in drug discovery and automated experimentation. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores core methodologies, tackles implementation challenges like data infrastructure and model transparency, and provides a comparative analysis of emerging tools and their validation. The review concludes by examining the trajectory towards self-driving labs and the critical ethical and governance frameworks needed to responsibly harness this triple exponential of data, compute, and models.

The New Language of Life: How AI Decodes Biological Complexity

The field of genomics has generated vast amounts of data through high-throughput sequencing technologies, creating an unprecedented challenge for analysis and interpretation [1]. Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly through foundation models, has emerged as a transformative solution to this challenge, enabling researchers to move from raw genetic sequences to functional understanding with remarkable speed and accuracy [2] [3]. This paradigm shift is revolutionizing biological research by providing tools that can decipher the complex relationships between genetic variation, cellular function, and disease phenotypes [4]. The integration of AI into genomics represents a fundamental change in research methodologies, moving beyond traditional reductionist approaches to a systems-level understanding of biology that can accelerate drug discovery and precision medicine [3].

Foundation models, trained on massive unlabeled datasets using self-supervised learning, have demonstrated exceptional capability in capturing the intricate patterns within biological sequences [4] [3]. These models leverage transformer architectures originally developed for natural language processing, treating DNA and protein sequences as biological "languages" to be deciphered [3]. The resulting AI systems can make predictions across diverse tasks—from variant effect prediction to protein structure determination—without task-specific training, making them uniquely powerful tools for modern biological research [4].

Foundation Models in Biology: Architectures and Capabilities

Core Architectures and Training Approaches

Foundation models in biology typically employ deep learning architectures, particularly transformers with self-attention mechanisms that can process sequential data in parallel [3]. These models are pre-trained on massive datasets through self-supervised learning objectives, such as masked language modeling, where portions of the input sequence are hidden and the model must predict them based on context [3]. This pre-training phase allows the model to develop a fundamental understanding of biological sequence syntax and semantics without requiring labeled data. After pre-training, models can be fine-tuned on specific downstream tasks with relatively small labeled datasets, leveraging transfer learning to achieve state-of-the-art performance across diverse applications [4].

The technological stack supporting these models includes specialized neural network architectures, transformer blocks with self-attention mechanisms, self-supervised learning methodologies, and substantial computational infrastructure often involving high-performance GPUs and distributed computing systems [3]. For example, training models like GPT-3 required 10,000 GPUs, highlighting the significant computational resources needed for developing foundation models [3].

Key Foundation Models for Genomic Analysis

Table 1: Foundation Models for Genomic Analysis and Their Applications

| Model Name | Domain | Training Data | Primary Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNABERT [4] | Genomics | DNA sequences | Predict regulatory regions, promoters, transcription factor binding sites | Adapted BERT architecture for DNA sequence context understanding |

| Geneformer [4] | Transcriptomics | 95M single-cell transcriptomes | Predict tissue-specific gene network dynamics | Context-aware model for settings with limited data |

| scGPT [4] | Transcriptomics | ~30M cells | Cell type annotation, gene network inference, multi-omic data integration | Generative AI for single-cell data analysis |

| Enformer [4] | Genomics | DNA sequences with epigenetic data | Predict effects of noncoding DNA on gene expression | Optimized for long-range interactions (up to 100kb) |

| AlphaFold [4] | Structural Biology | Amino acid sequences & known structures | Predict 3D protein structures from sequences | Near-experimental accuracy (Nobel Prize 2024) |

| DeepSEA [4] | Genomics | Noncoding genomic variants | Predict effects on chromatin and epigenetic regulation | Focus on functional noncoding regions |

These foundation models excel in capturing the contextual relationships within biological sequences. For instance, DNABERT leverages the bidirectional encoder representations from transformers architecture to understand DNA sequences contextually, enabling it to identify important regulatory regions like promoters and transcription factor binding sites with high accuracy [4]. Similarly, Enformer incorporates long-range genomic interactions—critical for understanding gene regulation—by considering genomic contexts up to 100 kilobases, significantly outperforming previous models that had limited receptive fields [4].

AI for Genomic Variant Interpretation and Functional Prediction

Variant Calling and Prioritization

AI systems have dramatically improved the accuracy and efficiency of identifying genetic variants from sequencing data. DeepVariant, a deep learning-based tool, exemplifies this advancement by using convolutional neural networks to identify true genetic variants from sequencing data with higher accuracy than traditional statistical methods [1]. The model treats variant calling as an image classification problem, transforming sequencing data into images that represent genomic evidence across multiple samples and then applying computer vision techniques to distinguish true variants from sequencing artifacts [1].

AlphaMissense represents another significant advancement, building upon the AlphaFold architecture to predict the pathogenicity of missense variants across the human genome [1]. This model leverages evolutionary information and structural constraints to classify variants as either benign or pathogenic, addressing a critical challenge in clinical genomics where the functional impact of most missense variants remains unknown [1]. By providing genome-wide pathogenicity predictions, AlphaMissense enables researchers to prioritize potentially disease-causing variants for further experimental validation.

Functional Interpretation of Non-Coding Variants

The interpretation of non-coding variants represents a particular challenge in genomics, as these variants often influence gene regulation through complex mechanisms that are difficult to predict. Foundation models like Enformer and DeepSEA address this challenge by learning the regulatory code of the genome from epigenomic data [4]. These models can predict how sequence alterations affect chromatin accessibility, transcription factor binding, and ultimately gene expression, enabling researchers to understand the functional consequences of non-coding variants associated with disease [4].

Table 2: AI Tools for Genomic Variant Interpretation

| Tool Name | Variant Type | Methodology | Key Performance Metrics | Applications in Research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepVariant [1] [2] | SNPs, Indels | Convolutional Neural Networks | Outperforms traditional tools on benchmark datasets | Germline and somatic variant detection |

| AlphaMissense [1] | Missense | Deep learning (AlphaFold-based) | 90% precision for pathogenic/benign classification | Rare disease gene discovery |

| DeepSEA [4] | Non-coding | Deep learning | Accurate EPI prediction from sequence alone | Regulatory variant interpretation |

| Enformer [4] | Non-coding | Deep learning with attention | Superior correlation with experimental measurements | Causal variant identification in GWAS |

Experimental Design and Validation Frameworks

AI-Guided Discovery Workflows

The integration of AI into genomic research has inspired new experimental frameworks that leverage computational predictions to guide laboratory validation. The AI co-scientist system developed by Google exemplifies this approach, using a multi-agent architecture built on Gemini 2.0 to generate novel research hypotheses and experimental protocols [5]. This system employs specialized agents for generation, reflection, ranking, evolution, proximity, and meta-review that work collaboratively to iteratively generate, evaluate, and refine hypotheses based on scientific literature and existing data [5].

Validation Case Studies

Drug Repurposing for Acute Myeloid Leukemia

In a validation study, the AI co-scientist was applied to identify drug repurposing opportunities for acute myeloid leukemia (AML) [5]. The system analyzed existing genomic and chemical data to propose novel therapeutic applications for approved drugs outside their original indications. Following computational prediction, researchers validated these proposals through in vitro experiments using multiple AML cell lines [5]. The experimental protocol involved treating cell lines with suggested drug candidates at clinically relevant concentrations and measuring tumor viability through standardized assays. Results confirmed that AI-proposed drugs effectively inhibited tumor viability, demonstrating the practical utility of AI-guided discovery approaches [5].

Target Discovery for Liver Fibrosis

In another case study, researchers employed the AI co-scientist to identify novel treatment targets for liver fibrosis [5]. The system generated and ranked hypotheses for potential targets, giving priority to those with supporting preclinical evidence and feasible experimental pathways. The validation process involved testing identified epigenetic targets in human hepatic organoids—3D multicellular tissue cultures designed to mimic human liver structure and function [5]. Researchers measured anti-fibrotic activity through specific biomarkers and functional assays, confirming significant activity for targets identified through the AI system. This approach demonstrated how AI can streamline the target discovery process, potentially reducing development time and costs [5].

Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for AI-Guided Genomic Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| AML Cell Lines [5] | In vitro models for testing therapeutic candidates | Validating drug repurposing predictions for leukemia |

| Human Hepatic Organoids [5] | 3D tissue models mimicking human liver physiology | Testing anti-fibrotic compounds in relevant human cellular context |

| Primary Cells from Patients [2] | Biologically relevant models with native genetic background | Assessing target engagement in disease-relevant systems |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Components [6] | Precise genome editing for functional validation | Establishing causal relationships between targets and phenotypes |

| Antibodies for Biomarkers [5] | Detection and quantification of protein targets | Measuring efficacy of interventions through established markers |

| Cell Viability Assays [5] | Quantitative measurement of therapeutic effects | Determining IC50 values for drug candidates |

Computational Infrastructure and Software

The implementation of AI in genomics requires substantial computational resources and specialized software tools. The market for AI in digital genomics is projected to grow from US$1.2 billion in 2024 to US$21.9 billion by 2034, reflecting increased adoption across research and clinical settings [7]. This growth is driven by pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies (key end-users) who are leveraging AI for drug discovery and development [7]. The machine learning segment dominates this market, as researchers utilize these algorithms to analyze massive genomic datasets efficiently [7].

Essential computational tools include deep learning frameworks like TensorFlow and PyTorch, specialized genomic analysis packages, and cloud computing platforms that provide scalable resources for training and deploying foundation models [3]. The computational demands are substantial—training foundation models may require thousands of GPUs and distributed computing approaches [3]. For applied research, platforms like Neptune.ai provide model visualization and tracking capabilities that are essential for interpreting complex AI systems and comparing model performance [8].

Future Directions and Ethical Considerations

The integration of AI and genomics continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping future research directions. Multi-omics integration represents a key frontier, as foundation models increasingly incorporate genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and epigenomic data to provide a more comprehensive understanding of biological systems [4] [2]. Models like Nicheformer and Novae are already bridging dissociated single-cell data with spatially resolved transcriptomics, enabling researchers to contextualize cellular data within tissue microenvironments [4].

Ethical considerations remain paramount in this field, particularly regarding data privacy, algorithmic bias, and equitable access [2]. Genomic data possesses inherent sensitivities and requires robust governance frameworks to protect individual privacy while enabling scientific progress [2]. Additionally, the underrepresentation of certain populations in genomic datasets can lead to biased AI models that perform poorly across diverse groups, potentially exacerbating health disparities [2]. Addressing these challenges requires collaborative efforts between researchers, clinicians, ethicists, and policymakers to develop responsible AI frameworks that maximize benefits while minimizing potential harms.

The convergence of CRISPR-based genome editing technologies with artificial intelligence represents another promising direction [6]. AI models are being used to optimize guide RNA design, predict off-target effects, and improve the efficiency of editing systems [6]. As these technologies mature, they will likely enable increasingly precise genetic interventions informed by comprehensive AI-driven genomic analysis, ultimately accelerating the development of novel therapeutics for genetic disorders [6] [2].

The prediction of a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence represents one of the most significant challenges in computational biology. For decades, this "protein folding problem" stood as a formidable barrier to understanding the molecular mechanisms of life. The advent of artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning, has catalyzed a revolutionary shift in this domain, culminating in the development of AlphaFold, an AI system that has fundamentally transformed structural biology. The 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded for the development of AlphaFold underscores the monumental importance of this breakthrough [9]. This whitepaper examines the core architectural principles of AlphaFold, assesses its transformative impact on biological research and drug development, and explores the next frontier: moving beyond static structures to capture the dynamic conformational landscapes that underlie protein function.

The Core Architecture of AlphaFold

AlphaFold's architecture represents a sophisticated integration of deep learning techniques with evolutionary and structural biological principles. The system operates on an end-to-end deep learning model that processes amino acid sequences and their evolutionary information to generate atomic-level structural coordinates [10].

Input Representation and Feature Engineering

The model begins by constructing a comprehensive set of input features derived from the target amino acid sequence:

- Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs): The input sequence is searched against large protein sequence databases (e.g., UniRef, BFD, MGnify) to identify homologous sequences. These MSAs capture evolutionary constraints that provide crucial information about residue-residue contacts [11].

- Template Structures: When available, experimentally determined structures of related proteins from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) are incorporated as templates [10].

- Pairwise Representations: The system computes a pairwise distance matrix between residues, encoding potential spatial relationships [10].

This rich set of input features is transformed into a multidimensional representation that serves as the foundation for the structural prediction process.

Neural Network Architecture

At the heart of AlphaFold lies a novel transformer-like architecture called the Evoformer, which processes the input features through multiple layers of abstraction:

- Evoformer Stack: This module jointly embeds the MSA and pairwise representations, allowing the system to reason about evolutionary relationships and spatial constraints simultaneously. The Evoformer employs attention mechanisms to identify long-range dependencies between residues, which is critical for accurate folding prediction [9].

- Structural Module: The embedded representations are passed to a structural module that iteratively refines the predicted 3D coordinates. This module employs a rotationally equivariant architecture that ensures physical plausibility of the generated structures [9].

The entire system is trained end-to-end on experimentally determined structures from the PDB, learning to minimize the difference between predicted and experimental coordinates.

Table: Key Databases for Protein Structure Prediction

| Database Name | Content Type | Scale | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Experimentally determined structures | ~200,000 structures | Training data for AI models; experimental reference [10] |

| AlphaFold Database | AI-predicted structures | >200 million entries | Broad structural coverage of known protein sequences [12] |

| UniProt | Protein sequences | ~200 million sequences | Source for sequence data and homology searching [10] |

| ATLAS | Molecular dynamics trajectories | 1,938 proteins; 5,841 trajectories | Protein dynamics analysis [13] |

| GPCRmd | MD data for GPCRs | 705 simulations; 2,115 trajectories | GPCR functionality and drug discovery [13] |

AlphaFold's Transformative Impact

Quantifiable Advances in Prediction Accuracy

The performance leap achieved by AlphaFold was quantitatively demonstrated during the 14th Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP14), where it outperformed all other methods by a significant margin [12]. The system regularly achieves accuracy competitive with experimental methods, with predicted structures often falling within the margin of error of experimental techniques like X-ray crystallography [9].

This breakthrough has virtually closed the gap between the number of known protein sequences and available structures. While traditional experimental methods yielded approximately 200,000 structures over several decades, AlphaFold has generated over 200 million structure predictions, dramatically expanding the structural universe available to researchers [12] [9].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

The availability of high-accuracy protein structures has accelerated multiple stages of the drug development pipeline:

- Target Identification and Validation: Researchers can now rapidly obtain structural models of potential drug targets, even for proteins that have resisted experimental characterization [14].

- Molecular Modeling and Drug Design: AI-predicted structures enable virtual screening of compound libraries and rational drug design approaches, significantly reducing the time and cost associated with early-stage discovery [14]. For instance, Insilico Medicine utilized AI-driven platforms to design a novel drug candidate for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in just 18 months, dramatically accelerating the traditional discovery timeline [14].

- Drug Repurposing: AI models can predict the compatibility of existing drugs with new protein targets, identifying new therapeutic applications. BenevolentAI successfully repurposed Baricitinib, a rheumatoid arthritis treatment, as a COVID-19 therapy through such approaches [14].

The integration of AI in drug development has demonstrated substantial practical benefits, with the FDA reporting a significant increase in drug application submissions incorporating AI components over recent years [15].

Diagram: AlphaFold2's Core Architecture - This workflow illustrates the end-to-end deep learning process that transforms amino acid sequences into accurate 3D structural models.

Beyond Static Structures: The New Frontier

Limitations of Static Structure Prediction

Despite its groundbreaking achievements, AlphaFold primarily predicts static, ground-state structures, representing a significant limitation since protein function often depends on dynamic transitions between multiple conformational states [13]. Current AI approaches face inherent challenges in capturing the dynamic reality of proteins in their native biological environments [16].

Proteins exist as conformational ensembles, sampling multiple states under physiological conditions. These dynamics are particularly crucial for understanding:

- Allosteric Regulation: Many proteins transmit signals through conformational changes between functional states.

- Flexible Regions and Intrinsic Disorders: Approximately 30-50% of eukaryotic proteins contain intrinsically disordered regions that adopt multiple conformations [13].

- Ligand-Induced Conformational Changes: Binding partners often induce structural rearrangements essential for biological function.

The limitations of static prediction become especially apparent for complex biological assemblies. While AlphaFold has been extended to predict protein complexes (AlphaFold-Multimer), accurately modeling inter-chain interactions remains challenging [11]. For instance, in antibody-antigen complexes, traditional methods struggle to predict binding interfaces due to limited co-evolutionary signals between host and pathogen proteins [11].

Emerging Approaches for Dynamic Conformation Prediction

Several innovative computational strategies are emerging to address the challenge of protein dynamics:

- Enhanced Sampling with AlphaFold: Researchers are modifying AlphaFold's input parameters, including MSA masking, subsampling, and clustering, to generate diverse conformational states from the same sequence [13].

- Generative Models: Diffusion models and flow matching techniques are being applied to sample conformational landscapes, transforming structure prediction into a sequence-to-structure generation process through iterative denoising [13].

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Physics-based simulations provide insights into protein dynamics at atomic resolution, with specialized databases like ATLAS and GPCRmd collecting simulation trajectories for various protein families [13].

- Structure Complementarity Approaches: New methods like DeepSCFold leverage sequence-derived structural complementarity rather than relying solely on co-evolutionary signals, improving performance for complexes lacking clear evolutionary coupling [11].

Table: Performance Comparison of Protein Complex Prediction Methods

| Method | TM-Score Improvement | Key Innovation | Application Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSCFold | 11.6% over AlphaFold-Multimer; 10.3% over AlphaFold3 | Sequence-derived structure complementarity | Protein complexes; antibody-antigen interfaces [11] |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Baseline for comparison | Extension of AlphaFold2 for multimers | General protein complexes [11] |

| AlphaFold3 | Commercial implementation | Unified architecture for biomolecules | Multiple biomolecular systems [11] |

| DMFold-Multimer | Superior CASP15 performance | Extensive sampling strategies | Challenging multimer targets [11] |

Diagram: From Static to Dynamic Protein Modeling - This conceptual framework shows the evolution from static structure determination to dynamic ensemble prediction, enabling more sophisticated drug discovery applications.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Research Resources for AI-Driven Protein Structure Prediction

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction Servers | AlphaFold Server, ColabFold, RoseTTAFold | Web-based platforms for generating protein structure predictions from sequence [9] |

| Structure Databases | AlphaFold Database, PDB, SWISS-MODEL Repository | Access to predicted and experimentally determined structures for analysis and comparison [12] |

| Specialized Dynamics Databases | ATLAS, GPCRmd, SARS-CoV-2 MD Database | Molecular dynamics trajectories for studying protein conformational changes [13] |

| Sequence Databases | UniProt, UniRef, MGnify | Source sequences for homology searching and multiple sequence alignment construction [10] |

| Analysis & Visualization | ChimeraX, PyMOL, SWISS-PDBViewer | Software for structural analysis, quality assessment, and visualization [10] |

| Specialized Prediction Tools | DeepSCFold, MULTICOM, DMFold-Multimer | Advanced tools for predicting protein complexes and interaction interfaces [11] |

The AlphaFold revolution has fundamentally transformed structural biology, providing researchers with an unprecedented view of the protein structural universe. Its ability to accurately predict static protein structures has accelerated research across virtually all domains of biology and drug discovery. However, the frontier is already shifting from static structures to dynamic conformational ensembles that more accurately represent protein function in living systems. The next generation of AI tools, building upon AlphaFold's legacy, aims to capture the intrinsic dynamics of proteins, enabling researchers to model functional mechanisms, allosteric regulation, and complex biomolecular interactions with increasing fidelity. This transition from structural determination to functional prediction represents the next chapter in AI-driven biological discovery, promising to deepen our understanding of life's molecular machinery and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics.

The convergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and biology is inaugurating a transformative era in biomedical research, fundamentally altering our approach to understanding cellular mechanisms. AI-powered virtual cell models represent a pioneering frontier, enabling researchers to simulate the intricate, dynamic processes within human cells with unprecedented fidelity. These computational models function as predictive digital twins of biological systems, allowing scientists to run millions of in silico experiments—computer simulations that mimic real biological processes—before ever setting foot in a wet lab. This approach is particularly valuable in drug development, where it helps researchers select preclinical experiments more intelligently, simulate experimental perturbations, inform biomarker selection, and gain deeper insight into the molecular mechanisms that drive experimental results [17]. By virtualizing biological experiments, these platforms address a critical bottleneck in traditional research, offering a scalable, reproducible, and highly efficient method for exploring cellular behavior and its implications for health and disease.

The drive toward virtual cell modeling stems from the profound complexity of biological systems, where traditional experimental methods often struggle with throughput, cost, and human variability. Companies like Turbine have spent the last decade developing foundational cell model simulation platforms that can rapidly run vast numbers of virtual experiments [17]. Similarly, Lila Sciences combines generative AI with a network of autonomous labs, creating a self-reinforcing loop where AI systems design, test, and refine scientific hypotheses in real-time [18]. These efforts aim to overcome the limitations of the human-centric scientific method by leveraging AI's ability to process enormous datasets and identify patterns invisible to human researchers. The resulting virtual cells provide a dynamic window into cellular processes, offering the potential to accelerate discovery across therapeutic areas from oncology to metabolic disease.

Core AI Technologies and Methodologies

The development of realistic virtual cell models relies on several interconnected AI technologies and methodologies that enable accurate simulation of cellular systems and dynamics.

Multi-Scale Modeling Architectures

Virtual cell platforms employ sophisticated multi-scale modeling architectures that integrate disparate biological data types into a unified simulation environment. These architectures typically incorporate mechanistic models based on established biological principles alongside data-driven models derived from experimental measurements. The Turbine platform, for example, utilizes machine learning to create virtual disease models that the company describes as "second only to the patient in predicting drug response" [17]. These models simulate how cells and tissues behave under treatment, helping pharmaceutical researchers identify promising therapeutic candidates more efficiently. The platform's capability to make accurate predictions on never-before-seen cell lines demonstrates its generalization capacity—a critical requirement for practical application in drug discovery [17].

AI-Driven Simulation Approaches

Several specialized AI approaches enable the simulation of specific cellular processes and systems:

Protein Structure and Interaction Prediction: Accurate modeling of protein interactions is fundamental to virtual cell simulations. While AlphaFold2-Multimer and AlphaFold3 have improved quaternary structure modeling, their accuracy for complexes hasn't reached the level achieved for single proteins. The MULTICOM4 system addresses this limitation by wrapping AlphaFold's models in an additional layer of ML-driven components that significantly enhances their performance for protein complexes [19]. This advancement is particularly valuable for simulating signaling pathways and drug-target interactions within virtual cells.

Small Molecule Binding Affinity Prediction: Molecular design often relies on all-atom co-folding models that can predict 3D structures of molecular interactions, but these models traditionally struggle with small molecules prevalent in pharmaceuticals. Boltz-2, an improved version of Boltz-1, addresses this challenge by providing unified structure and affinity prediction with GPU optimizations and integration of synthetic and molecular dynamics training data [19]. This technology offers FEP-level (Free Energy Perturbation) accuracy with speeds up to 1000 times faster than existing methods, making early-stage in silico screening practical for drug discovery applications.

Autonomous Experimentation Systems: Fully autonomous systems represent the cutting edge of AI-driven biology. BioMARS is an intelligent agent that fully automates biological experiments by combining large language models (LLMs), multimodal perception, and robotic control [19]. The system's architecture consists of three AI agents: a Planner agent that breaks down experimental goals into executable steps, an Actor agent that writes and executes code for robotic control, and an Evaluator agent that analyzes results and provides feedback. While still requiring human supervision for unusual experiments, such systems point toward a future of highly automated, reproducible biological research.

Data Integration and Knowledge Representation

Virtual cell models integrate diverse data types through unified knowledge representation schemes that enable coherent simulation of cellular processes. These systems typically incorporate structured knowledge bases (such as protein-protein interaction networks, metabolic pathways, and gene regulatory networks), experimental data (including transcriptomics, proteomics, and imaging data), and scientific literature (processed through natural language understanding systems). The integration of these heterogeneous data sources enables comprehensive simulation of cellular behavior across multiple temporal and spatial scales, from rapid molecular interactions to slow phenotypic changes.

Table 1: Key AI Technologies Powering Virtual Cell Simulations

| Technology | Function | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| MULTICOM4 Protein Prediction | Enhances AlphaFold's performance for protein complexes | Improved accuracy for large assemblies; handles complexes with poor MSAs | Challenging for non-globular complexes like antibodies [19] |

| Boltz-2 Affinity Prediction | Predicts small molecule binding affinity & structure | 1000x faster than FEP simulations; FEP-level accuracy | Requires further validation across diverse target classes [19] |

| BioMARS Autonomous Lab | Automates biological experiments via multi-agent AI | Integrates LLMs with robotic control; reduces human variability | Limited ability to handle unexpected deviations; research system only [19] |

| Recursion's MAP Platform | Maps human biology via automated microscopy & AI | High-throughput compound screening; identifies novel drug targets | Requires massive computational resources and data storage [18] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

The development and validation of virtual cell models require rigorous experimental protocols to ensure biological relevance and predictive accuracy. This section outlines key methodological approaches and their real-world applications.

Model Training and Validation Protocol

Virtual cell models are typically developed and validated through a systematic protocol:

Data Curation and Integration: Collect and harmonize diverse datasets including transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolic, and imaging data from publicly available databases and proprietary sources. Turbine's platform, for example, has developed the capacity to "not only harmonize but generate purpose-built datasets for rapid cell model building and iteration" [17].

Model Architecture Selection: Choose appropriate neural network architectures (convolutional networks, graph neural networks, transformers) based on the specific cellular process being modeled. The three scaling laws identified by AI researchers guide this process: pre-training scaling (larger models with more data show predictable improvements), post-training scaling (specialization through fine-tuning), and test-time scaling (extended reasoning during inference) [18].

Cross-Validation: Implement rigorous cross-validation strategies using held-out experimental data to assess model performance. This includes temporal validation (testing on data from later time points than training data) and compositional validation (testing on different cell lines or conditions than those used in training).

Experimental Confirmation: Design wet-lab experiments to test key predictions generated by the virtual cell model. For instance, Turbine's model successfully predicted that SLFN11 gene knockout contributes to non-small cell lung cancer resistance to the payload SN38, which was subsequently validated experimentally [17].

Case Study: ADC Payload Selection

Antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) represent a promising cancer therapy approach but present immense complexity due to the intricate interplay of antibody, linker, and cytotoxic payload. The potential permutations for an ADC stretch into the billions, creating a needle-in-a-haystack problem for traditional discovery approaches [17]. Turbine's Virtual Lab addresses this challenge through a specialized workflow:

Virtual Sample Generation: Create in silico representations of diverse cancer cell types with varying genetic backgrounds and phenotypic states.

Payload Response Simulation: Expose virtual cells to different ADC payloads and combinations, simulating cellular responses including target engagement, pathway modulation, and cell fate decisions.

Resistance Prediction: Identify potential resistance mechanisms by analyzing simulated signaling pathway adaptations following payload exposure.

Candidate Ranking: Prioritize payload candidates based on simulated efficacy, toxicity profiles, and potential resistance mechanisms.

This approach enables researchers to explore "payload-payload and payload-drug combinations across a wide variety of virtual samples," opening "a yet untouched search space" for ADC development [17]. The platform's Payload Selector module, released in 2025, represents one of the first commercial applications of virtual cell technology for ADC development.

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of AI in Drug Discovery and Development

| Parameter | Traditional Approach | AI-Accelerated Approach | Improvement | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Preclinical Candidate | 4-5 years | 12-18 months | 40-70% reduction | [19] [20] |

| Cost to Preclinical Candidate | High (context-dependent) | ~30% reduction | ~30% reduction | [19] [20] |

| Clinical Trial Phase II Failure Rate | ~90% | Potential improvement | Under investigation | [17] [20] |

| Target Identification & Compound Design | Multiple years | 18 months (Rentosertib example) | Significant acceleration | [19] |

Statistical Validation Methods

Rigorous statistical validation is essential for establishing the predictive power of virtual cell models. The following methods are commonly employed:

T-test for Mean Comparison: Used to determine if differences between simulated and experimental results are statistically significant. The t-test formula:

t = (x̄₁ - x̄₂) / (s_p √(1/n₁ + 1/n₂))

where x̄₁ and x̄₂ are sample means, s_p is the pooled standard deviation, and n₁ and n₂ are sample sizes. A prerequisite for the t-test is checking homogeneity of variances using an F-test [21].

F-test for Variance Comparison: Determines whether the variances of two populations are equal before conducting a t-test. The F-test formula:

F = s₁² / s₂² (where s₁² ≥ s₂²)

This test helps ensure the appropriate version of the t-test is used (equal or unequal variances) [21].

Performance Metrics: Virtual cell models are evaluated using standard metrics including Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUC-ROC), precision-recall curves, and mean squared error for continuous predictions. These metrics provide quantitative assessment of model performance against experimental data.

The experimental validation of Turbine's platform demonstrated its ability to make accurate predictions on never-before-seen cell lines, a crucial test of generalizability. In one example, "without training on SN38 combination datasets, Turbine's model accurately identified that SLFN11 gene knockout contributes to non-small cell lung cancer resistance to the payload SN38" [17]. This finding was particularly significant as SLFN11 is already recognized as a biomarker for drug resistance, underscoring the platform's capability to recapitulate known biology while generating novel insights.

Implementation and Workflow

Implementing virtual cell technology requires careful consideration of computational infrastructure, data requirements, and integration with existing research workflows. This section outlines the practical aspects of deploying these systems in biomedical research environments.

System Architecture and Computational Requirements

Virtual cell platforms typically employ distributed computing architectures to handle the substantial computational demands of cellular simulations. The core components generally include:

- Data Integration Layer: Harmonizes diverse biological data from public repositories, proprietary databases, and experimental results.

- Simulation Engine: Executes virtual experiments using specialized algorithms for molecular interactions, pathway dynamics, and cellular processes.

- AI/ML Modeling Layer: Applies machine learning models to predict cellular behavior and analyze simulation results.

- Visualization and Interpretation Interface: Enables researchers to explore simulation results through interactive visualizations and analytical tools.

The computational infrastructure for virtual cell simulations often requires high-performance computing (HPC) resources or cloud-based computing platforms. The emergence of test-time scaling (also called "long thinking") allows AI systems to reason through complex biological problems during inference, a process that "might take minutes or even hours, requiring over 100 times the compute of traditional AI inference" but yields "a much more thorough exploration of potential solutions" [18].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Virtual cell modeling relies on both computational tools and physical research reagents for model training and validation. The table below outlines key components of the research environment for AI-driven cellular simulation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Virtual Cell Modeling

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose | Validation Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Lines | Immortalized cell lines (HEK293, HeLa), Primary cells, Patient-derived cells | Provide experimental data for model training and validation | Essential for confirming in silico predictions in biological systems [17] |

| Assay Kits | Cell viability assays, Apoptosis detection kits, Pathway-specific reporter assays | Generate quantitative data on cellular responses to perturbations | Used to measure actual cellular responses compared to simulated predictions [17] |

| Molecular Biology Reagents | CRISPR-Cas9 components, siRNA libraries, Antibodies for protein detection | Enable experimental manipulation and measurement of specific cellular components | Critical for testing model predictions through targeted interventions [19] |

| Computational Tools | TensorFlow, PyTorch, AlphaFold, MULTICOM4, Boltz-2 | Provide infrastructure for building and running AI models and simulations | Open-source and commercial software enable implementation of virtual cell platforms [19] |

Integration with Drug Development Workflows

Virtual cell models are increasingly integrated into standardized drug development workflows, particularly in the following applications:

Target Identification and Validation: AI platforms like Insilico Medicine's have demonstrated the ability to nominate both disease-associated targets and therapeutic compounds, reducing the traditional target identification timeline significantly. Their TNIK inhibitor, Rentosertib, completed a Phase 2a trial, representing "the first reported case where an AI platform enabled the discovery of both a disease-associated target and a compound for its treatment" [19].

Lead Optimization: Virtual cell models simulate the effects of chemical modifications on compound efficacy, selectivity, and toxicity, enabling more efficient lead optimization cycles. Recursion Pharmaceuticals employs an AI-powered platform that integrates "automated biology, chemistry, and cloud-based computing to test thousands of compounds in parallel," aiming to overcome "Eroom's Law—the paradox that despite advances in technology, the cost and time required to bring new drugs to market have continued to rise" [18].

Clinical Trial Design: By simulating drug responses across virtual patient populations, these models can inform patient stratification strategies and biomarker selection. Turbine's Clinical Positioning Suite helps with "patient stratification and life cycle management" through simulations that predict how different patient subgroups may respond to treatments [17].

The following diagram illustrates a representative workflow for integrating virtual cell technology into drug discovery pipelines:

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant progress, virtual cell technology faces several substantial challenges that must be addressed to realize its full potential in biological research and drug development.

Technical and Validation Challenges

Current limitations of virtual cell technology include:

Model Generalizability: While platforms like Turbine's have demonstrated predictions on unseen cell lines, ensuring robust performance across diverse tissue types, disease states, and experimental conditions remains challenging. Models trained on limited cellular contexts may not extrapolate reliably to novel situations [17].

Multi-Scale Integration: Accurately connecting molecular-level events (e.g., protein-ligand interactions) to cellular phenotypes (e.g., proliferation, apoptosis) represents a significant modeling challenge. Current approaches often struggle to seamlessly bridge these spatial and temporal scales [22].

Data Quality and Availability: The performance of virtual cell models is heavily dependent on the quality, quantity, and diversity of training data. Gaps in biological knowledge and noisy experimental measurements can limit model accuracy and reliability [19].

Computational Complexity: High-fidelity simulations of cellular processes demand substantial computational resources, creating barriers to widespread adoption, particularly for academic laboratories and smaller biotech companies [18].

Black Box Limitations: Many AI models operate as "black boxes," creating challenges for regulatory approval of AI-designed drugs and devices. The lack of interpretability in model predictions can hinder biological insight and erode researcher trust [19].

Emerging Solutions and Future Developments

Several promising approaches are emerging to address these challenges:

Enhanced Explainability: New methods for model interpretation, including attention mechanisms and feature importance analysis, are being developed to make AI predictions more transparent and biologically interpretable.

Federated Learning: This approach enables model training across multiple institutions without sharing proprietary data, addressing data privacy concerns while expanding the diversity of training datasets.

Automated Experimental Validation: Systems like BioMARS point toward a future of highly automated, reproducible biological validation, where AI-generated hypotheses can be rapidly tested in the wet lab with minimal human intervention [19].

Integration with Emerging Technologies: The combination of virtual cell models with new modalities, including CRISPR-based screening and single-cell multi-omics, promises to enhance model accuracy and biological relevance.

The following diagram illustrates the future vision of an integrated, AI-driven research ecosystem:

As virtual cell technology matures, it is poised to become an increasingly central component of biological research and drug development. The ongoing development of more sophisticated AI algorithms, coupled with growing biological datasets and computational resources, suggests that these models will continue to improve in accuracy, scope, and practical utility. While significant challenges remain, the potential impact of virtual cell technology on our understanding of biology and our ability to develop effective therapies represents a compelling frontier at the intersection of AI and life sciences.

The burgeoning field of multi-omics represents a paradigm shift in biological research, moving from a siloed examination of molecular layers to a holistic, systems-level understanding. This approach integrates diverse data types—including genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—to construct a comprehensive molecular portrait of health and disease [23] [24]. The primary challenge, however, lies in the sheer volume, complexity, and high-dimensional nature of these datasets. This is where Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) become transformative. AI provides the computational framework necessary to detect subtle, non-linear patterns and interactions within and between these omics layers, patterns that are often imperceptible to traditional analytical methods [23] [25]. The integration of multi-omics data, supercharged by AI, is accelerating the transition from descriptive biology to a predictive and ultimately engineering science, with profound implications for precision medicine, drug discovery, and functional biology [26].

Within the broader thesis of AI's role in biology, multi-omics integration stands as a cornerstone application. Biological research is becoming increasingly 'multi-omic,' and AI is the essential tool for deciphering the connections between these data types, revealing previously hidden patterns and causal relationships [25] [26]. This synergy is not merely additive but multiplicative, enabling researchers to move from correlation to causation, to simulate biological systems in silico, and to design novel biological components [27]. As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health. Learn more: PMC Disclaimer | PMC Copyright Notice. This technical guide will delve into the core AI methodologies, experimental protocols, and practical tools that are defining this new frontier.

Core AI Methodologies for Multi-Omics Data

The successful integration of multi-omics data requires a diverse arsenal of AI and ML techniques, each suited to particular data structures and research objectives. These methods can be broadly categorized, and their selection is critical for generating robust, biologically interpretable results.

Table 1: Core AI and Machine Learning Methodologies in Multi-Omics Research

| Method Category | Key Examples | Primary Applications in Multi-Omics | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Learning | Random Forest (RF), Support Vector Machines (SVM) [23] | Disease diagnosis, prognosis risk prediction, drug response prediction [23] [28] | Requires high-quality labeled data; risk of overfitting; feature selection is critical [23] |

| Unsupervised Learning | k-means clustering, autoencoders [23] | Patient subtyping, novel biomarker discovery, identifying hidden structures in data [23] [28] | Output is unknown; ideal for exploratory analysis; avoids labelling bias [23] |

| Deep Learning (DL) | Deep Neural Networks, Transformers, Graph Neural Networks [23] [29] [25] | Predicting long-range interactions, single-cell analysis, perturbation prediction, filling gaps in incomplete datasets [29] [25] | Data-hungry; complex "black box" models; challenges in interpretability [23] [25] |

| Transfer Learning | Instance-based, parameter-based, and feature-based algorithms [23] | Mapping models across platforms or species, adapting models to new tasks with limited data [23] | Risk of "negative transfer" if source and target domains are too dissimilar [23] |

Traditional and Deep Learning Approaches

Supervised learning methods are employed when the outcome variable is known, such as disease status or treatment response. For instance, a researcher might use a Random Forest classifier trained on proteomic data from patients with myocardial infarction to predict the risk of poor prognosis [23]. This process involves feature labeling, classifier calibration, and rigorous performance validation to ensure reliability and robustness against overfitting [23]. In contrast, unsupervised learning methods like k-means clustering are used for discovery-oriented tasks, such as identifying novel disease subtypes or cellular subpopulations without pre-defined labels [23] [28].

Deep Learning (DL), a subset of ML, has recently shown remarkable success. DL models, such as transformers, leverage large-scale neural networks to learn representations from raw data in an end-to-end manner [23]. Their application in single-cell biology is particularly notable, where models like scGPT and scFoundation act as foundation models for diverse downstream tasks including cell-type annotation and perturbation prediction [25]. Furthermore, graph neural networks are powerful for integrating relational data, such as protein-protein interaction networks, with other omics layers to reveal dysregulated pathways [29].

Data Integration Strategies and Challenges

The strategy for integrating multiple omics datasets is as important as the choice of AI model. The main approaches are early integration (concatenating raw datasets), intermediate integration (learning joint representations), and late integration (combining results from separate analyses) [28]. Intermediate integration is often favored for its ability to learn a unified representation of the separate datasets, which can then be used for tasks like subtype identification [28].

Key computational challenges persist, including the "curse of dimensionality"—where the number of features vastly exceeds the number of samples—and data harmonization across different technological platforms [23] [29]. Additionally, the black-box nature of many complex AI models remains a significant hurdle for clinical adoption. This has spurred growth in the field of interpretable ML (IML), which aims to make model decisions transparent and provide biological insights, such as identifying which genomic variants and protein expressions were most influential in a prediction [25].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Implementing a robust AI-driven multi-omics study requires a meticulous workflow, from sample collection to model validation. The following protocol outlines the key stages for a typical study aiming to identify biomarkers for patient stratification.

The diagram below outlines the key stages in a typical AI-driven multi-omics analysis workflow.

Detailed Methodology

Sample Collection and Multi-Omics Profiling:

- Collect patient samples (e.g., tissue, blood) with appropriate ethical approval and informed consent. The cohort should be designed to reflect population diversity to mitigate bias and health disparities [24].

- Subject samples to high-throughput assays for each omics layer:

- Genomics/Epigenomics: Use next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) for whole genome sequencing, exome sequencing, or ATAC-sequencing for chromatin accessibility [24].

- Transcriptomics: Perform RNA sequencing (bulk or single-cell) to quantify gene expression levels [23] [25].

- Proteomics: Utilize advanced platforms from companies like Olink or Somalogic, which can identify up to 5,000 analytes, to profile protein expression and modifications [23].

- Metabolomics: Employ mass spectrometry to quantify a wide range of cellular metabolites, including amino acids and fatty acids [23].

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control:

- Process raw data using platform-specific pipelines. For NGS data, this includes alignment (e.g., to a reference genome), variant calling, and generation of count matrices for expression data [24].

- Perform rigorous quality control (QC) for each dataset. This involves removing low-quality samples, normalizing for technical variation (e.g., sequencing depth), and batch effect correction. Tools like GATK and DeepVariant are often used for genomic variant calling [24].

Feature Selection and Dimensionality Reduction:

- Apply feature selection methods to reduce noise and computational load. This can include filtering low-variance features or using model-based importance scores (e.g., from Random Forest) [23].

- Use dimensionality reduction techniques like PCA or autoencoders to project high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space while preserving key biological signals, facilitating both visualization and downstream analysis [23].

AI/ML Model Integration and Analysis:

- Select an integration strategy and AI model based on the research objective (see Table 1).

- For patient subtyping, an unsupervised method like a clustering algorithm (e.g., k-means) or a deep learning autoencoder can be applied to the integrated data to identify distinct molecular subgroups [28].

- For outcome prediction, a supervised model like Random Forest or a deep neural network can be trained on the integrated features to predict a labeled endpoint, such as survival or drug response [23] [29].

- Split data into training and validation sets. Train the model on the training set and tune hyperparameters using cross-validation to avoid overfitting.

- Select an integration strategy and AI model based on the research objective (see Table 1).

Validation and Biological Interpretation:

- Validate model performance on a held-out test set or an independent cohort. Metrics depend on the task (e.g., accuracy, silhouette score, area under the ROC curve).

- Employ interpretable AI (IML) techniques to extract biological insight. This can involve calculating feature importance scores, using model-agnostic methods like SHAP, or performing enrichment analysis on model-derived features to identify dysregulated pathways (e.g., oxidative phosphorylation, synaptic transmission) [25] [30].

- Experimental validation of key findings (e.g., identified biomarkers) in cellular or animal models is crucial for translational impact [30].

The advancement of AI-driven multi-omics relies on access to large, high-quality datasets and specialized software tools.

Table 2: Key Public Data Resources for Multi-Omics Research

| Resource Name | Omics Content | Species | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) [28] | Genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, proteomics | Human | Cancer research, biomarker discovery, patient subtyping |

| Answer ALS [28] | Whole-genome sequencing, RNA transcriptomics, ATAC-sequencing, proteomics | Human | Neurodegenerative disease research, deep clinical data integration |

| jMorp [28] | Genomics, methylomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics | Human | Population-level variation across multiple omics layers |

| Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD) [24] | Genomic sequencing data from large populations | Human | Reference for putatively benign genetic variants |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

A successful multi-omics experiment depends on a suite of wet-lab and computational reagents.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq | High-throughput sequencing platform | Generates genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic data; capable of 20-52 billion reads per run [24]. |

| Olink & Somalogic Platforms | High-plex proteomics analysis | Identify and quantify up to 5,000 proteins, addressing the curse of dimensionality in proteomics [23]. |

| Mass Spectrometer | Metabolite identification and quantification | Profiles a wide range of cellular small molecules for metabolomics [23]. |

| AlphaFold / RoseTTAFold | AI-based protein structure prediction | Predicts 3D protein geometry and biomolecular interactions, crucial for understanding function [25]. |

| Random Forest (scikit-learn) | Supervised learning classifier | Robust for classification and regression tasks on multi-omics data; provides feature importance scores [23]. |

| Transformers (e.g., scGPT) | Deep learning architecture for sequences | Foundation models for single-cell biology; excel at tasks like cell-type annotation and perturbation prediction [25]. |

| GATK / DeepVariant | Genomic variant calling pipelines | Essential bioinformatics tools for processing raw sequencing data into analyzable genetic variants [24]. |

The integration of genomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data through advanced AI is fundamentally reshaping biological inquiry and therapeutic development. This synergy provides an unparalleled, systems-level view of physiology and disease pathogenesis, moving beyond correlation to uncover causal mechanisms and generate predictive models [27]. While challenges in data standardization, model interpretability, and equitable representation persist [25] [24], the trajectory is clear. The fusion of multi-omics and AI is pushing biology into a new era of prediction and engineering, paving the way for highly personalized diagnostics and therapeutics, and ultimately fulfilling the promise of precision medicine.

From Code to Cure: AI-Driven Applications Redesigning Biology

The exploration of biological design space has been fundamentally transformed by artificial intelligence (AI). Traditional methods in protein engineering, antibody discovery, and nanomaterial development have long been constrained by their reliance on existing biological templates and labor-intensive experimental processes. The integration of generative AI marks a paradigm shift from this incremental, template-dependent approach to a pioneering methodology capable of creating entirely novel biomolecules and nanostructures from first principles. This computational revolution is accelerating the discovery of functional proteins, epitope-specific antibodies, and optimized nanomaterials, thereby expanding the accessible frontiers of biotechnology and medicine beyond the constraints of natural evolution [31].

The core challenge in de novo design lies in the astronomical scale of the possible sequence-structure space. For a modest 100-residue protein, the number of possible amino acid arrangements (20^100) exceeds the number of atoms in the observable universe. Within this vastness, the subset of sequences that fold into stable, functional structures is vanishingly small [31]. Generative AI addresses this challenge by learning the complex mappings between sequence, structure, and function from vast biological datasets, enabling the computational design of biomolecules with customized properties that nature has never explored.

AI-Driven Protein Design

From Physics-Based to AI-Augmented Design

Historically, de novo protein design relied on physics-based modeling. Tools like Rosetta operated on the principle that a protein's amino acid sequence dictates its thermodynamically most stable three-dimensional structure. These methods used fragment assembly and force-field energy minimization to design novel proteins, such as the Top7 protein in 2003, which featured a fold not observed in nature [31]. However, these approaches faced significant limitations. The underlying force fields were approximations, and the computational expense of exhaustive conformational sampling was prohibitive, particularly for large or complex proteins.

Modern AI-augmented strategies complement and extend these physics-based methods. Machine learning (ML) models are trained on large-scale biological datasets to establish high-dimensional mappings learned directly from sequence-structure relationships [31]. This AI-driven paradigm leverages powerful generative architectures, including diffusion models and protein language models, to explore the protein functional universe systematically.

Key Methodologies and Experimental Workflows

The AI protein design pipeline typically involves a cycle of computational generation and experimental validation. Key methodologies include:

- Generative Models: Frameworks like RFdiffusion employ a diffusion process that iteratively denoises random protein structures to generate novel scaffolds targeting specific functional sites or epitopes [32].

- Sequence Design: Following structural generation, tools like ProteinMPNN design sequences that are predicted to fold into the generated structures [32].

- In Silico Validation: Fine-tuned structure prediction networks, such as a specialized RoseTTAFold2 (RF2), are used to validate designs by predicting the structure of the designed sequence and assessing its similarity to the intended design (self-consistency) and the quality of the intended interface [32].

The diagram below illustrates a typical workflow for the de novo design of a binding protein, from target specification to experimental characterization.

AI-Driven Protein Design Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Design

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for AI-Driven Protein Design and Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|

| Yeast Display Libraries | High-throughput screening of thousands of designed protein variants for binding to a fluorescently labeled target antigen [32]. |

| OrthoRep System | A platform for in vivo continuous evolution and affinity maturation of proteins, enabling the development of high-affinity binders without the need for iterative library construction [32]. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | High-resolution structural validation of designed protein-antigen complexes to confirm the atomic accuracy of the design [32]. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Label-free quantification of binding affinity (equilibrium dissociation constant, Kd) between designed proteins and their targets [32]. |

De Novo Antibody Design

The Challenge of Specific Binding

Antibodies are a dominant class of therapeutics, but their discovery has traditionally relied on animal immunization or screening of random libraries, processes that are laborious, time-consuming, and can fail to identify antibodies that interact with therapeutically relevant epitopes [32]. Computational de novo design of antibodies, particularly the hypervariable complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) that drive binding, has been a long-standing challenge. Unlike mini-binders that often use regular secondary structures, antibody CDRs are long, flexible loops that do not benefit directly from evolutionary information in the same way [33].

State-of-the-Art Architectures and Tools

Significant progress has been made by fine-tuning general protein design networks on antibody-specific data. A landmark demonstration used a fine-tuned RFdiffusion network to design antibody variable heavy chains (VHHs), single-chain variable fragments (scFvs), and full antibodies that bind user-specified epitopes [32]. The key innovation was conditioning the network on a fixed antibody framework structure while allowing it to design the CDR loops and the overall rigid-body orientation relative to the target. This enables the generation of novel antibodies that are specific to a chosen epitope. Experimental success was confirmed by cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures that verified the atomic-level accuracy of the designed CDR loops [32].

The field is rapidly advancing, with several specialized tools emerging in 2024-2025:

Table 2: AI Models for De Novo Antibody Design in 2025

| AI Model | Core Architecture | Key Capabilities | Reported Experimental Success |

|---|---|---|---|

| RFantibody [32] [33] | Fine-tuned RFdiffusion | De novo design of VHHs, scFvs, and full antibodies to specified epitopes. | Cryo-EM validation of designed VHHs and scFvs; initial affinities in nanomolar range. |

| IgGM [33] | Comprehensive suite | De novo design, affinity maturation. | Third place in AIntibody competition; requires empirical testing. |

| Chai-2 [33] | Not specified | High-success-rate binder generation. | Claimed 50% success rate for creating binding antibodies, some with sub-nanomolar affinity. |

| Germinal [33] | Integrates IgLM, AF3 | Binder design with built-in filters. | Code recently released; performance still being evaluated. |

Experimental Protocol: Designing a VHH Binder

The following detailed protocol is adapted from recent successful campaigns for the de novo design of single-domain antibodies (VHHs) [32]:

Target and Framework Preparation:

- Obtain the high-resolution structure of the target antigen (e.g., from Protein Data Bank, PDB).

- Define the target epitope by selecting specific residue indices on the antigen surface.

- Select a stable, humanized VHH framework (e.g., h-NbBcII10FGLA) to serve as the structural scaffold for the designed CDR loops.

Computational Generation and Filtering:

- Structure Generation: Run the fine-tuned RFdiffusion network, providing the target structure, epitope residues as "hotspots," and the framework structure as a conditioning template. Generate thousands of candidate antibody structures with novel CDR conformations.

- Sequence Design: Use ProteinMPNN to design sequences for the generated CDR loops.

- In Silico Filtering: Use a fine-tuned RoseTTAFold2 network to re-predict the structure of each designed antibody-antigen complex. Filter for designs where the predicted structure closely matches the designed structure (high self-consistency) and exhibits low predicted binding energy (ddG). This step significantly enriches for experimental binders.

Experimental Screening and Validation:

- Library Construction: Synthesize DNA encoding the top hundreds to thousands of filtered designs and clone them into a yeast surface display vector.

- Selection: Perform fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to isolate yeast cells displaying designs that bind to the labeled target antigen.

- Affinity Maturation: For initial binders with modest affinity (e.g., tens to hundreds of nanomolar), use a continuous evolution system like OrthoRep to generate and screen mutant libraries in vivo, rapidly evolving single-digit nanomolar binders.

- Biophysical Characterization: Express and purify lead candidates. Measure binding affinity using surface plasmon resonance (SPR).

- Structural Validation: Determine the high-resolution structure of the designed antibody-antigen complex using cryo-EM or X-ray crystallography to confirm the binding pose and atomic-level accuracy of the design.

Generative AI for Nanostructures

Integrating AI with Nanomanufacturing

Generative AI is revolutionizing nanotechnology by predicting and optimizing material behavior at the nanoscale, drastically reducing the time and cost associated with traditional trial-and-error methods [34]. AI algorithms can design nanomaterials with specific properties, simulate their performance, and optimize synthesis parameters. This convergence is enabling breakthroughs across medicine, energy, and electronics.

The application of AI in nanotechnology spans two fundamental manufacturing approaches, as outlined in the diagram below.

AI in Top-Down and Bottom-Up Nanomanufacturing

Key Applications and Quantitative Impact

Table 3: AI-Driven Innovations in Nanotechnology Across Industries

| Field | Application | AI Impact & Quantitative Results |

|---|---|---|

| Healthcare | AI-designed lipid nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery in cancer therapy. | Increased targeted delivery efficiency by 95% in a University of Tokyo case study [34]. |

| Energy | AI-optimized nanostructures for lithium-ion battery electrodes. | Reduced trial-and-error experiments by 80%, identifying materials that significantly improved energy density and lifespan (Stanford University) [34]. |

| Electronics | AI-simulated nanostructures for microchips. | Reduced manufacturing defects by 50% and cut development cycles in half (IBM) [34]. |

| Environment | AI-designed nanoscale catalysts for water purification. | Created filters that remove heavy metals and microplastics more efficiently than conventional systems [34]. |

The integration of generative AI into biological and materials design represents a foundational shift in research methodology. The ability to computationally generate, validate, and optimize designs before synthesis is dramatically accelerating the pace of discovery. Key future directions include the development of multimodal generative AI that can fuse natural language with raw biological data to create more powerful and less biased predictive systems [35], and the continued expansion of context windows in genomic models like Evo 2, which can process up to one million nucleotides to understand long-range genetic interactions [36].

As these tools mature, they will transition from specialized research use to indispensable components of the scientific toolkit. However, this progress must be accompanied by rigorous experimental validation, responsible development to mitigate risks such as the generation of misinformation [35], and a commitment to open science to reduce friction in the adoption and improvement of these technologies [33]. The convergence of generative AI with biology and nanotechnology is not merely an incremental improvement but a fundamental transformation, opening a new era of engineering biology with atomic-level precision.

The Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is the fundamental engine of biological research and metabolic engineering, enabling the iterative development of microbial strains for therapeutic and industrial applications. Traditional DBTL workflows are often hampered by combinatorial explosions of possible genetic designs and the immense time and cost required for experimental validation. The integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) is fundamentally reshaping this paradigm, transitioning the process from sequential, human-led experimentation to a semi-automated, computationally driven workflow. This transformation is accelerating the pace of discovery and enhancing the ability to identify optimal biological solutions in a vast design space. Framed within the broader thesis of AI's role in biology, this whitepaper details how AI injects intelligence and predictive power into each stage of the DBTL cycle, creating a more efficient and insightful engineering loop [37] [38].

The AI-Augmented DBTL Cycle: A Phase-by-Phase Technical Analysis

AI in the Design Phase

The Design phase involves planning which genetic modifications to make. AI's role here is to intelligently navigate the vast combinatorial space of potential designs, such as promoters, ribosomal binding sites (RBS), and coding sequences, to propose optimal genetic configurations.

- Generative AI for de novo Design: Tools like Evo 2, a generative AI model trained on the genomes of all known living species, can autocomplete gene sequences. Researchers can prompt it with the beginning of a gene sequence, and the model will generate novel completions, sometimes improving upon natural sequences or writing genes in entirely new ways. This capability allows scientists to steer mutations toward useful functions deliberately [36].

- Predicting Form and Function: Beyond sequence generation, models can predict the 3D structure and functional implications of these novel sequences, forecasting how they will behave in a living cell [36].

- Navigating Complex Interactions: AI excels at modeling non-intuitive, long-distance interactions between genes. For instance, a kinetic model-based framework demonstrated that perturbing one enzyme could have unexpected, non-linear effects on the flux of a downstream product. AI can learn these complex relationships from data to recommend synergistic genetic combinations that would be difficult to identify through rational design alone [37].

AI in the Build and Test Phases

The Build phase involves the physical construction of the designed genetic variants, while the Test phase involves characterizing these strains to measure key performance indicators (e.g., titer, yield, rate).

- Automation and Robotics: The Build phase is being accelerated by automation in biofoundries, where robotic systems perform high-throughput DNA synthesis and assembly. While not exclusively AI, these systems are often integrated with AI platforms for sample tracking and workflow optimization [38].

- High-Throughput Screening and Data Generation: In the Test phase, advanced analytical techniques like high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) and flow-injection analysis (FIA) generate massive datasets on strain performance [38]. This data serves as the critical fuel for the AI models in the Learn phase.

- Virtual Cell and In Silico Models: AI is enabling the creation of "Virtual Cell" frameworks that simulate living cells across multiple scales. This allows researchers to run dozens of standard experiments with a virtual query in minutes or hours instead of years, drastically reducing the number of physical experiments needed. These simulations can model everything from fundamental cell division to complex batch bioreactor processes [37] [39].

AI in the Learn Phase

The Learn phase is where AI has the most profound impact. Here, data from the Test phase is analyzed to extract insights and generate new hypotheses for the next Design cycle.

- Machine Learning for Predictive Modeling: Supervised learning algorithms, such as gradient boosting and random forests, have been shown to be particularly effective in the low-data regime typical of early DBTL cycles. These models learn the complex relationships between genetic designs (inputs) and performance metrics (outputs) to predict the performance of untested designs [37].

- Recommendation Algorithms: Specialized algorithms use the predictions from ML models to recommend a new set of promising strains for the next DBTL cycle. These algorithms balance exploration (testing novel designs to improve the model) and exploitation (testing designs predicted to be high-performing) [37].