AlphaFold2: Revolutionizing Protein Structure Prediction in Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of AlphaFold2 (AF2), the artificial intelligence system that has transformed computational biology by predicting protein structures from amino acid sequences with atomic-level accuracy.

AlphaFold2: Revolutionizing Protein Structure Prediction in Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of AlphaFold2 (AF2), the artificial intelligence system that has transformed computational biology by predicting protein structures from amino acid sequences with atomic-level accuracy. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles and architecture of AF2, its practical applications in structure-based drug discovery and target validation, and advanced methodologies for optimizing predictions. We further detail rigorous validation protocols and confidence metrics essential for reliable use, address common limitations, and discuss the integration of AF2-predicted models with experimental data. The article concludes by synthesizing AF2's profound impact on accelerating biomedical research and its future trajectory, including emerging resources that ensure the continued relevance of predicted structures.

The AlphaFold2 Revolution: Unraveling the Principles Behind Accurate Protein Structure Prediction

The Protein Folding Problem and the Historical Context of Computational Prediction

The "protein folding problem," a grand challenge in science for over 50 years, concerns the difficulty of predicting a protein's native three-dimensional (3D) structure solely from its one-dimensional amino acid sequence [1] [2]. The biological function of a protein is directly correlated with its 3D structure, and understanding this structure is critical for deciphering biological processes and addressing human health challenges, particularly in drug development [2] [3]. For decades, experimental methods such as X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) have been the primary means for determining protein structures. However, these techniques are often complex, time-consuming, and expensive, creating a significant gap between the number of known protein sequences and those with experimentally resolved structures [2].

This gap has driven the development of computational methods for protein structure prediction. The field witnessed a paradigm shift with the introduction of deep learning, culminating in DeepMind's AlphaFold2 (AF2), which demonstrated unprecedented accuracy in the 14th Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP14) in 2020 [4] [1]. This application note details the historical context of the protein folding problem, outlines the breakthrough represented by AF2, and provides detailed protocols for its application in research, with a special focus on its utility and limitations for drug development professionals.

Historical Context and the Pre-AlphaFold2 Landscape

Computational protein structure prediction methods were traditionally divided into distinct categories based on the information they utilized. Table 1 summarizes the primary methodological approaches that dominated the field before the advent of deep learning.

Table 1: Traditional Computational Methods for Protein Structure Prediction

| Method Category | Core Principle | Example Tools | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ab Initio/Free Modeling | Relies on physicochemical laws and thermodynamics to find the structure with the lowest free energy, often using fragment-based assembly [2] [5]. | QUARK [2] | Computationally intractable for long sequences; struggles to predict novel folds accurately [6] [2]. |

| Threading/Fold Recognition | Based on the concept that protein folds are more conserved than sequences; identifies the best-fitting known fold for a target sequence using a scoring function [2]. | GenTHREADER [2] | Limited by the repertoire of known folds in databases; cannot predict truly novel folds. |

| Homology Modeling | Assumes that highly similar sequences have similar structures; uses a known structure of a homologous protein as a template [2] [5]. | SWISS-MODEL [2], MODELLER [6] | Entirely dependent on the availability and quality of a homologous template structure. |

The performance of these methods was rigorously evaluated in the biennial Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) competition. Prior to 2018, the accuracy of predictions, especially for proteins without close homologs, was limited, with the best methods achieving a Global Distance Test (GDT) score of around 40-60 on a 0-100 scale where 100 represents a perfect match to the experimental structure [4] [2]. This highlighted that the protein folding problem was far from solved.

The AlphaFold2 Breakthrough

Algorithmic Innovation

AlphaFold2's success at CASP14, where it achieved a median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å (a level comparable to experimental error), represented a transformational leap [1]. Its architecture is an end-to-end deep learning model that departs significantly from its predecessor and other traditional methods.

The key innovation lies in its neural network architecture, which jointly embeds two primary inputs:

- Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs): A collection of evolutionarily related sequences.

- Pairwise Features: A representation of inferred relationships between residues [1].

These inputs are processed through a novel component called the Evoformer, a neural network block that exchanges information between the MSA and pair representations. This allows the network to reason simultaneously about evolutionary constraints and spatial relationships [1]. The output of the Evoformer is then passed to the Structure Module, which introduces an explicit 3D structure. This module uses an equivariant transformer to iteratively refine the atomic coordinates, starting from a trivial initial state and progressively building a highly accurate model with precise atomic details [1]. A critical feature is "recycling," where the output is recursively fed back into the network for several cycles of refinement, significantly enhancing accuracy [1].

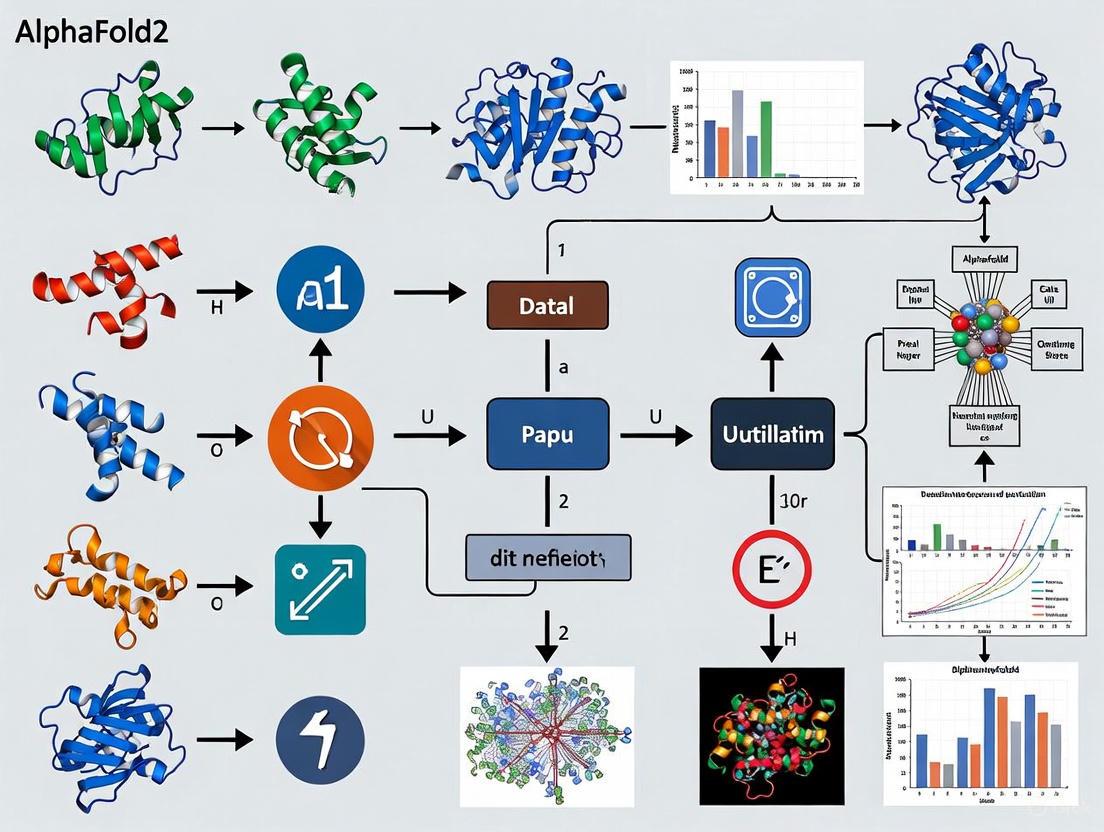

Diagram 1: AlphaFold2's core architecture and workflow for structure prediction.

Performance and Validation

In CASP14, AlphaFold2's predictions were vastly more accurate than any other method, achieving a median backbone accuracy (Cα root-mean-square deviation, RMSD) of 0.96 Å, compared to 2.8 Å for the next best method [1]. This level of accuracy is competitive with many experimentally determined structures. DeepMind subsequently applied AF2 at a massive scale, creating the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database, which expanded the structural coverage of the human proteome from about 17% to over 98%, providing an unprecedented resource for the scientific community [3].

A key feature of AF2 is its internal confidence measure, the predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT). This per-residue score, ranging from 0 to 100, allows users to assess the reliability of different regions of a predicted model. Generally, pLDDT scores above 90 indicate very high confidence, scores between 70 and 90 are confident, scores between 50 and 70 are low confidence, and scores below 50 should be considered very low confidence, potentially representing unstructured regions [1] [7]. AF2 also provides a Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) matrix, which estimates the confidence in the relative positional alignment of different parts of the model, which is crucial for understanding domain packing and orientations [7].

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol: Running AlphaFold2 for Single-Chain Protein Prediction

This protocol outlines the steps to predict the structure of a single protein chain using a standard AlphaFold2 implementation, such as the local installation or via ColabFold [7].

Step 1: Input Sequence Preparation

- Obtain the target protein's amino acid sequence in FASTA format. Sequences can be sourced from public databases like UniProt.

- The sequence length should ideally be between 10 and 3,000 amino acids. Very short sequences (<10) may not generate reliable MSAs, while very long sequences may encounter hardware memory limitations [7].

Step 2: Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Generation

- Input the FASTA sequence into the AF2 pipeline.

- The system will automatically query genetic databases (e.g., BFD, MGnify, Uniclust30) to construct an MSA and a pair representation of the target.

- This step identifies evolutionarily related sequences, which provide the co-evolutionary information critical for accurate folding [1] [7].

Step 3: Structure Prediction and Model Generation

- The Evoformer and Structure Module process the MSA and pair representations. No user intervention is required at this stage.

- The system typically generates five models. The iterative "recycling" process (usually 3 cycles by default) is embedded within this step and is key to achieving high accuracy [1].

Step 4: Model Analysis and Selection

- Analyze the generated models using the provided pLDDT and PAE metrics.

- The model with the highest average pLDDT is typically selected as the top-ranked model.

- Visually inspect the model, coloring it by pLDDT to identify low-confidence regions. Use the PAE plot to evaluate inter-domain confidence [7].

Protocol: Benchmarking AlphaFold2 on Peptide Structures

While AF2 excels with globular proteins, its performance on small peptides (10-40 amino acids) requires careful validation. The following protocol is based on the benchmark study by McDonald et al. [8].

Step 1: Dataset Curation

- Select a diverse set of peptides with experimentally determined NMR structures. The benchmark should include different structural classes: α-helical membrane-associated, α-helical soluble, mixed secondary structure membrane-associated, mixed secondary structure soluble, β-hairpin, and disulfide-rich peptides [8].

- A total of 588 peptides were used in the original study.

Step 2: Structure Prediction and RMSD Calculation

- Predict the structure of each peptide in the dataset using AlphaFold2 as described in Protocol 4.1.

- For each peptide, compute the Cα root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) between the AF2-predicted structure and the corresponding experimental NMR structure. The RMSD calculation should be normalized per residue and focused on the secondary structural region to prevent size bias [8].

Step 3: Analysis of Confidence Metrics versus Accuracy

- Compare the pLDDT-ranked order of the five generated models against their actual RMSD to the experimental structure.

- Note any discrepancies where the model with the lowest RMSD (highest accuracy) is not the one ranked highest by pLDDT. This is a known limitation in peptide modeling [8] [7].

- Analyze Φ/Ψ angle recovery and disulfide bond pattern prediction, as these are specific areas where AF2 can show shortcomings for peptides [8].

Table 2: Summary of AlphaFold2 Performance on Different Peptide Classes (based on [8])

| Peptide Class | Number of Peptides | Mean Normalized Cα RMSD (Å per residue) | Key Observations and Shortcomings |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Helical Membrane-Associated | 187 | 0.098 | Predicted with good accuracy; few outliers. Struggles with helix termini and turn motifs. |

| α-Helical Soluble | 41 | 0.119 | More outliers than membrane-associated; fails to predict helical structure in some cases (e.g., 1AMB). |

| Mixed Sec. Struct. Membrane-Assoc. | 14 | 0.202 | Largest variation and RMSD; correct secondary structure but poor overlap in unstructured regions. |

| β-Hairpin | 176 | Data Not Specified | High accuracy, similar to helical peptides. |

| Disulfide-Rich | 170 | Data Not Specified | High accuracy, but errors in disulfide bond patterns can occur. |

Application in Drug Discovery: Identifying a Kinase Inhibitor

A demonstrated application of AF2 in drug discovery is the rapid discovery of a novel cyclin-dependent kinase 20 (CDK20) inhibitor for hepatocellular carcinoma [3].

Workflow:

- Target Identification: Use a target identification platform (e.g., PandaOmics) to nominate CDK20 as a promising target.

- Structure Retrieval: Download the predicted structure of CDK20 from the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database.

- In Silico Screening & Molecule Generation: Use the AF2 structure with a generative chemistry platform (e.g., Chemistry42) to design and screen thousands of small molecule candidates.

- Compound Filtering: Apply developability filters to select the top 7 candidates for synthesis.

- Experimental Validation: Test the synthesized compounds in biochemical and cellular assays. One compound showed high binding affinity (Kd = 9.2 nM) and selectively inhibited cancer cell proliferation.

This end-to-end process, from target to validated hit, was completed in just 30 days, showcasing the potential of AF2 to dramatically accelerate early-stage drug discovery [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Resources for AlphaFold2-Based Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function and Description | Access Link/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Provides instant, free access to over 200 million pre-computed AF2 protein structure predictions, eliminating the need for local computation. | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ [3] |

| ColabFold | Software Suite | An open-access, streamlined implementation of AF2 that runs via Google Colab notebooks or locally. It uses the faster MMseqs2 for MSA generation, significantly speeding up predictions. | https://github.com/sokrypton/ColabFold [7] |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Software Module | A specialized version of AF2 trained to predict the structures of protein complexes (homo- and hetero-multimers), which is crucial for studying protein-protein interactions. | [4] [3] |

| AlphaPullown | Software Tool | A Python package designed for high-throughput screening of protein-protein interactions using AlphaFold-Multimer. | [3] |

| pLDDT & PAE | Analysis Metric | Integrated confidence scores that are essential for interpreting model reliability and guiding experimental design. | [1] [7] |

Critical Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its transformative impact, AlphaFold2 has several important limitations that researchers must consider:

- Static Snapshots: AF2 predicts a single, static structure. It does not model the conformational dynamics, flexibility, or multiple states that are often essential for protein function [7] [9].

- Limitations with Specific Classes: Performance is reduced for non-globular proteins, such as intrinsically disordered regions, and it can struggle with accurate prediction of disulfide bond patterns and membrane protein conformational states [8] [7] [9].

- Peptide Modeling Caveats: As highlighted in Protocol 4.2, the pLDDT score may not reliably rank the most accurate model for peptides, and Φ/Ψ angle recovery can be poor [8].

- Ligand and Cofactor Absence: Standard AF2 predicts apo structures. It does not include ligands, cofactors, post-translational modifications, or ions, which can be critical for function, though AlphaFold3 has begun to address this for some biomolecules [4] [7].

Future directions involve moving beyond static snapshots to predict conformational ensembles and integrating AF2 models with experimental data from techniques like cryo-EM, NMR, and molecular dynamics simulations to model dynamic processes and allosteric mechanisms more accurately [7] [9].

Diagram 2: A hybrid experimental-computational workflow to overcome AF2 limitations.

The prediction of a protein's three-dimensional structure from its amino acid sequence has stood as a monumental challenge in computational biology for over half a century. Often referred to as the "protein folding problem," its solution is crucial for understanding biological function, elucidating disease mechanisms, and accelerating drug discovery. For decades, experimental methods like X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) have been the primary means to determine protein structures. However, these techniques are often time-consuming and expensive, resulting in a vast gap between the number of known protein sequences and their experimentally solved structures—a challenge known as the "structural gap" [10] [11].

In November 2020, Google DeepMind's AlphaFold2 (AF2) achieved an unprecedented victory at the 14th Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP14), demonstrating accuracy competitive with experimental methods for many proteins [4] [10]. This breakthrough represented a transformative moment in structural biology. The subsequent release of the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database, providing over 200 million predicted structures, has since empowered researchers worldwide, offering unprecedented insights into the protein universe and accelerating scientific discovery across biology and medicine [12] [13].

The CASP14 Victory: A Paradigm Shift

The CASP Competition and AlphaFold2's Achievement

The Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) is a biennial, double-blind competition that serves as the gold standard for evaluating protein structure prediction methods. In CASP14, AlphaFold2 outperformed all other methods by a significant margin, achieving a median Global Distance Test (GDT) score above 90 for approximately two-thirds of the proteins predicted. The GDT score measures the structural similarity between a prediction and the experimental reference, with a score of 100 representing a perfect match. This level of accuracy was previously attainable only through experimental determination and marked a historic milestone in computational biology [4] [10].

Quantitative Performance at CASP14

Table 1: AlphaFold2 Performance Metrics at CASP14

| Performance Metric | Result | Context and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Median GDT Score | >90 (for ~2/3 of proteins) | Accuracy considered competitive with experimental methods [4] |

| Overall Performance | Top-ranked by a large margin | Far exceeded all other methods in the competition [12] [4] |

| Key Advancement | Accuracy for "difficult" targets | Dramatically improved predictions for proteins with no known structural templates [10] |

Underlying Architecture and Algorithmic Breakthroughs

AlphaFold2's success stems from a novel, end-to-end deep learning architecture that represents a significant departure from its predecessor, AlphaFold1, and other contemporary methods.

Core Algorithmic Innovations

The system employs an interconnected neural network model that co-evolves representations through two key modules operating on a pair representation (residue-residue relationships) and a single representation (residue-sequence relationships) [4]. A critical innovation is the use of an attention-based mechanism, which allows the network to dynamically focus on the most relevant information when processing sequences and constructing the 3D model. This process iteratively refines the structural prediction, starting from a rough initial topology and progressively improving it while minimizing unphysical bond angles and lengths until a highly accurate structure is produced [4].

Diagram: AlphaFold2's Simplified High-Level Workflow

The AlphaFold Database: Scaling to 200 Million Structures

Following its CASP14 triumph, DeepMind partnered with EMBL's European Bioinformatics Institute (EMBL-EBI) to create the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database. This resource was initially launched with structures for the human proteome and 47 other key organisms, and has since been expanded to contain over 200 million predicted structures, providing broad coverage of the UniProt knowledgebase [12] [13]. This effectively covers nearly the entire catalogued protein universe, a scale that would have been unimaginable using traditional experimental methods. The database is freely and openly available to the global scientific community under a Creative Commons license (CC-BY 4.0) [12].

Database Usage and Impact Metrics

The database has been widely adopted, with over 2 million researchers across 190 countries utilizing it to support their work [13]. It is estimated that the database has potentially saved millions of research years, drastically accelerating the pace of biological inquiry [13].

Experimental Validation and Confidence Metrics

The pLDDT Score: A Measure of Prediction Confidence

AlphaFold2 provides a per-residue confidence score called the predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT). This metric ranges from 0 to 100 and is a crucial tool for researchers to assess the local reliability of a predicted model [11]. While pLDDT is an internal confidence measure, it has been shown to correlate with model accuracy. It is also increasingly used as an indicator of protein flexibility, with lower scores often corresponding to regions of higher intrinsic disorder or dynamics [14].

Table 2: Interpreting AlphaFold2 pLDDT Confidence Scores

| pLDDT Score Range | Confidence Level | Interpretation and Recommended Use |

|---|---|---|

| > 90 | Very high | High backbone accuracy; suitable for detailed atomic-level analysis [11] |

| 70 - 90 | Confident | Good backbone prediction; reliable for analyzing structural features [11] |

| 50 - 70 | Low | Low confidence; use with caution, potential errors in geometry [11] |

| < 50 | Very low | Very low confidence; likely unstructured or disordered regions [11] |

Practical Protocols for Researchers

This section provides detailed methodologies for accessing and utilizing AlphaFold2 predictions in research workflows.

Protocol 1: Accessing and Analyzing Structures from the AlphaFold Database

The primary method for most researchers is to retrieve pre-computed structures from the AlphaFold Database.

Procedure:

- Access the Database: Navigate to the AlphaFold Protein Structure Database at https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/.

- Search for a Protein: Use a UniProt identifier, gene name, or organism name to search for your protein of interest.

- Retrieve the Entry: Select the correct protein entry from the search results.

- Download Data: Download the predicted structure in PDB or mmCIF format. The associated data files, containing per-residue pLDDT scores and predicted aligned error, can also be downloaded.

- Visualization and Analysis:

- Open the PDB file in a molecular visualization tool like PyMOL, UCSF Chimera, or ChimeraX.

- Color the structure by the pLDDT score to visually assess the confidence of different regions. This is critical for interpreting functional domains or active sites.

- Analyze the structure for known functional motifs, binding pockets, or oligomerization interfaces in the context of biological knowledge.

Protocol 2: Running AlphaFold2 for Novel Sequences

For sequences not available in the database (e.g., novel mutants or designed proteins), researchers can run the AlphaFold2 model.

Computational Requirements: Running AlphaFold2 is computationally intensive. The following are general system guidelines, though requirements can vary based on sequence length [15].

Table 3: Recommended System Requirements for AlphaFold2

| Resource Type | Recommended (Best) | Minimum (Poor Experience) |

|---|---|---|

| GPU | NVIDIA A100 | NVIDIA CUDA GPU with >=32GB VRAM |

| CPU Cores | >= 64 | >= 12 |

| RAM | >= 180 GB | >= 64 GB |

| SSD Storage | >= 1.3 TB (NVMe, >3,500 MB/s) | Varies, but fast SSD recommended |

Procedure:

- Software Setup: Install AlphaFold2 from its open-source repository on GitHub, ensuring all dependencies and required genetic databases are installed and configured.

- Input Preparation: Prepare a FASTA file containing the amino acid sequence(s) to be predicted.

- Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA): Execute the

run_alphafold.pyscript. The system will first generate MSAs using tools like JackHMMER and HHblits against genomic databases. This is the most time-consuming step and performance is highly dependent on CPU cores and disk speed [15]. - Structure Inference: The neural network will process the MSA and template information (if used) to generate the 3D model. This step is heavily dependent on GPU capability. Note that structure prediction time grows exponentially with sequence length [15].

- Output Analysis: The run will produce several PDB files representing top-ranked models, along with JSON files containing pLDDT scores and other confidence metrics. Analyze these outputs as described in Protocol 1.

Protocol 3: Integrating Experimental Data to Guide Predictions (DEERFold)

Advanced protocols are being developed to integrate sparse experimental data to guide AlphaFold2 and model conformational ensembles, addressing a key limitation of predicting single, static structures.

Principle: Methods like DEERFold fine-tune AlphaFold2 to incorporate experimental distance distributions, such as those from Double Electron-Electron Resonance (DEER) spectroscopy, to predict alternative protein conformations [16].

Procedure:

- Experimental Data Collection: Collect DEER data to obtain distance distributions between spin labels site-specifically introduced into the protein.

- Data Representation: Convert the experimental distance distributions into a format compatible with the neural network architecture (e.g., a "distogram").

- Model Guidance: Input the distance constraints into the modified AlphaFold2 model (DEERFold) alongside the protein sequence.

- Ensemble Generation: Run predictions. The incorporation of distance constraints drives the model to fold into conformations consistent with the experimental data, often resulting in a heterogeneous ensemble of structures.

- Validation: Compare the resulting model ensemble with the experimental data and other known structural information to validate the predictions.

Diagram: DEERFold Experimental Workflow

Table 4: Key Resources for AlphaFold2-Based Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Primary repository for accessing over 200 million pre-computed protein structure predictions [12] |

| UniProt | Database | Standard repository of protein sequences and annotations; serves as the foundation for the AlphaFold DB [12] |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Repository for experimentally determined structures; used for validation and comparison with AF2 models [11] |

| AlphaFold2 Open Source Code | Software | Allows researchers to run structure predictions on custom sequences not in the database [12] |

| pLDDT Score | Analytical Metric | Per-residue confidence score essential for interpreting the local reliability of AF2 predictions [11] |

| DEER/EPR Spectroscopy | Experimental Method | Provides distance restraints to guide and validate AF2 models for modeling conformational ensembles [16] |

| Cryo-EM / X-ray Crystallography | Experimental Method | Gold-standard methods for high-resolution structure determination; used to validate AF2 predictions [10] [11] |

Applications in Biology and Medicine

The availability of highly accurate protein structures is revolutionizing numerous fields.

- Drug Discovery: AF2 models are used to understand drug targets, identify binding pockets, and perform structure-based virtual screening, particularly for targets with no or limited experimental structural data [10] [17]. For example, AF2 has been applied to study nuclear receptors, important drug targets, providing models where experimental structures are scarce [11].

- Protein Design: AF2's understanding of structure is inverted to design novel proteins with desired functions, such as therapeutic mini-binders and enzymes [17].

- Understanding Disease Mechanisms: AF2 models help elucidate the structural impact of disease-related mutations, providing insights into conditions like cancer, Parkinson's, and antibiotic resistance [13] [10].

- Membrane Transporters and Enzymes: AF2 has provided structural insights into challenging protein classes like membrane transporters and has been used to engineer plastic-degrading enzymes to address environmental pollution [13] [16].

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its transformative impact, AlphaFold2 has limitations. It primarily predicts a single, static conformation and may not capture the full spectrum of native conformational dynamics and flexibility that are critical for the function of many proteins [16] [11]. While it can predict some multimeric structures, accurately modeling large protein complexes remains challenging. Furthermore, its performance can be lower for proteins with limited evolutionary information in the multiple sequence alignments [16], and it does not explicitly predict the effects of ligands, ions, or post-translational modifications, though tools like AlphaFold3 are now addressing this [4] [17].

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with new methods like DEERFold demonstrating the integration of experimental data to guide predictions [16], and the recent release of AlphaFold3 expanding capabilities to predict protein interactions with DNA, RNA, and small molecules [4]. The continued development and application of these tools promise to further deepen our understanding of biological systems and accelerate therapeutic development.

AlphaFold2 (AF2) represents a paradigm shift in computational biology, providing a solution to the 50-year-old protein folding problem by predicting three-dimensional (3D) protein structures from amino acid sequences with atomic-level accuracy [1] [10]. Its unprecedented success in the CASP14 assessment demonstrated capabilities competitive with experimental methods, fundamentally transforming structural biology research and therapeutic development [1]. The architectural brilliance of AF2 resides primarily in two interconnected components: the Evoformer, a novel neural network block that processes evolutionary and pairwise relationships, and the Structure Module, which translates these refined representations into accurate atomic coordinates [1] [18]. This application note provides a detailed technical deconstruction of these core components, offering researchers comprehensive insights into their operational mechanisms and implementation protocols.

The Evoformer: A Graph Inference Engine for Evolutionary and Spatial Relationships

The Evoformer serves as the computational trunk of AF2, formulating and continuously refining a structural hypothesis through iterative processing of input data [1]. It operates on two primary representations that are updated in parallel:

- MSA Representation: An Nseq × Nres array (where Nseq is the number of sequences and Nres is the number of residues) that encapsulates evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments. Each column represents individual residues of the input sequence, while rows represent homologous sequences [1] [19].

- Pair Representation: An Nres × Nres array that models the relationships between every pair of residues in the target protein, encoding information about their spatial and evolutionary constraints [1] [18].

Table 1: Evoformer Input Features and Embedding Process

| Input Type | Representation | Processing Method | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) | Nseq × Nres array | Clustering by similarity with representative selection | Embedding raw sequences rather than only MSA statistics [18] |

| Template Structures | Nres × Nres distance matrices | Discretization into distogram bins | Integration of known structural homologs when available [1] |

| Primary Sequence | Amino acid residues | Direct embedding with residue features | Preservation of original sequence information [19] |

Core Computational Operations and Information Exchange

The Evoformer's revolutionary design enables sophisticated information exchange through several specialized operations implemented across its 48 blocks [18]:

MSA-Pair Communication Channels:

- Outer Product Mean: The MSA representation updates the pair representation through an element-wise outer product summed over the MSA sequence dimension. Unlike previous approaches, this operation occurs within every Evoformer block, enabling continuous information flow [1].

- Pair Bias Injection: During row-wise attention in the MSA representation, additional logits projected from the pair stack bias the attention mechanism, creating a reciprocal information flow from pairwise to evolutionary data [18].

Triangular Geometric Reasoning: The pair representation undergoes updates inspired by geometric constraints necessary for 3D structural consistency:

- Triangle Multiplicative Update: A symmetric operation that uses two edges of a residue triplet to update the "missing" third edge, enforcing geometric consistency [1].

- Triangular Self-Attention: An attention mechanism augmented with a logit bias to include the third edge of residue triangles, ensuring the pairwise distances satisfy the triangle inequality [1].

Axial Attention Mechanisms:

- Row-wise Attention: Operates across sequences in the MSA to identify which amino acids are evolutionarily related.

- Column-wise Attention: Functions within alignment columns to determine which sequences provide the most relevant structural information [18].

Experimental Protocol: Evoformer Representation Analysis

Purpose: To extract and interpret the intermediate representations generated by the Evoformer for hypothesis generation about protein structure-function relationships.

Materials:

- Protein sequence of interest

- High-performance computing environment with AlphaFold2 implementation

- Multiple sequence alignment tools (Jackhmmer/HHblits)

- Protein structure databases (PDB, UniRef)

Procedure:

- Input Preparation:

- Generate MSAs by querying the target sequence against protein databases using Jackhmmer with default parameters [19].

- Extract template structures if available from the PDB using homology search tools.

Evoformer Activation Extraction:

- Modify the AF2 inference code to save the MSA and pair representations after each Evoformer block.

- Run inference on the target sequence with recycling disabled initially to analyze progressive refinement.

Representation Analysis:

- Apply dimensionality reduction (UMAP/t-SNE) to track the evolution of residue-residue relationships across blocks.

- Compute attention maps from row-wise and column-wise attention heads to identify co-evolutionary patterns.

- Calculate mutual information between MSA and pair representations to quantify their interdependence.

Structural Hypothesis Generation:

- Correlate high-attention residue pairs with known structural motifs or functional sites.

- Identify conserved interaction patterns across Evoformer blocks that may indicate stable structural contacts.

Interpretation: Early Evoformer blocks typically establish coarse-grained residue contacts, while later blocks refine these into precise spatial relationships. Consistent high-attention regions across multiple blocks often correspond to structurally critical elements like active sites or folding nuclei [1].

Diagram 1: Evoformer Information Flow (62 characters)

The Structure Module: From Representations to Atomic Coordinates

Architectural Principles and Invariant Transformations

The Structure Module translates the refined representations from the Evoformer into precise 3D atomic coordinates through a series of equivariant operations [1]. Its design incorporates several key innovations:

- Explicit 3D Structure: Introduces a rotation and translation (rigid body frame) for each residue, initialized trivially with identity rotations and origin positions [1].

- Chain Breakage: Temporarily breaks the chain connectivity to allow simultaneous local refinement of all structure parts, preventing propagation of errors [1].

- Invariant Point Attention (IPA): A novel attention mechanism specifically designed for 3D molecular structures that respects rotational and translational equivariance, meaning predictions are independent of the global orientation [18].

Iterative Refinement through Recycling

A critical aspect of AF2's performance is the iterative refinement process known as "recycling" [1] [19]:

- Initial Prediction: The Structure Module generates an initial 3D structure from the Evoformer outputs.

- Feedback Integration: The predicted structure, along with MSA and pair representations, is fed back into the beginning of the network.

- Progressive Refinement: This recycling process typically repeats three times, with each iteration refining the structural details and improving accuracy [19].

- Confidence Estimation: The model provides per-residue confidence estimates (pLDDT) that reliably predict the local accuracy of the prediction [1].

Table 2: Structure Module Output Metrics and Their Interpretation

| Metric | Calculation | Interpretation | Threshold Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| pLDDT (predicted local distance difference test) | Percentage of atom pairs within distance thresholds of reference [14] | Per-residue confidence estimate | <50: Low confidence, 50-70: Medium, 70-90: High, >90: Very high [1] |

| pTM (predicted TM-score) | Estimated template modeling score for global structure quality [20] | Global fold accuracy assessment | >0.5: Correct fold, >0.8: High accuracy [21] |

| ipTM (interface pTM) | Interface-specific version of pTM for complexes [20] | Protein-protein interface quality | Primary metric for complex assessment [20] |

| PAE (predicted aligned error) | Expected positional error after alignment [20] | Domain orientation confidence | Lower values indicate higher confidence in relative positioning |

Experimental Protocol: Structure Module Ablation Studies

Purpose: To systematically evaluate the contribution of different Structure Module components to prediction accuracy.

Materials:

- Benchmark set of proteins with experimentally determined structures

- Modified AF2 codebase with selective component disabling capability

- Structural comparison tools (TM-score, RMSD calculators)

Procedure:

- Baseline Establishment:

- Select a diverse set of protein targets (different folds, sizes, MSA depths).

- Run standard AF2 prediction with full Structure Module and record accuracy metrics (pLDDT, TM-score, RMSD to experimental structure).

Component Ablation:

- Disable the recycling mechanism by setting recycle count to 1.

- Replace Invariant Point Attention with standard attention mechanisms.

- Modify the residue representation to maintain chain connectivity throughout.

- Remove side chain atoms from the representation, focusing only on backbone.

Controlled Comparison:

- For each ablation condition, run predictions on the same benchmark set.

- Ensure identical initial conditions (MSA, templates, random seeds).

- Quantify accuracy metrics for each condition.

Intermediate Structure Analysis:

- Extract and save intermediate structures during the recycling process.

- Calculate quality metrics for structures after each recycling step.

- Analyze the trajectory of structural refinement.

Interpretation: The recycling process typically contributes significantly to accuracy with minimal extra computational cost. Invariant Point Attention is particularly crucial for proper stereochemistry, while chain breakage enables more effective local refinement [1].

Diagram 2: Structure Module Workflow (46 characters)

Integrated Workflow: From Sequence to Structure

End-to-End Prediction Protocol

Purpose: To provide a comprehensive methodology for utilizing AF2's complete architecture for protein structure prediction.

Materials:

- Protein sequence(s) of interest in FASTA format

- High-performance computing cluster with GPU acceleration

- AlphaFold2 software installation with required databases

- Structural visualization and analysis software (ChimeraX, PyMOL)

Procedure:

- Input Preparation and Feature Extraction:

- Generate MSAs using Jackhmmer against multiple sequence databases (UniRef90, MGnify).

- Search for template structures using HHsearch against the PDB.

- Extract and embed evolutionary and template features.

Evoformer Processing:

- Process inputs through the 48 Evoformer blocks with information exchange between MSA and pair representations.

- Monitor convergence of representations through attention pattern stabilization.

Structure Generation:

- Initialize the structure with trivial frames (identity rotations, origin positions).

- Process through the Structure Module with Invariant Point Attention.

- Perform iterative refinement through three recycling steps.

- Place side chain atoms and refine their positions.

Output and Validation:

- Generate final atomic coordinates in PDB format.

- Compute confidence metrics (pLDDT, pTM, PAE).

- Validate structures using geometric checks (Ramachandran plots, steric clashes).

Troubleshooting:

- Low confidence predictions (pLDDT < 50) often result from shallow MSAs; consider adding homologous sequences.

- Domain misorientation may be addressed by examining the PAE matrix for high inter-domain errors.

- Steric clashes can be relieved using energy minimization tools while preserving the overall fold.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for AlphaFold2 Architecture Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ColabFold | Optimized AF2 implementation with MMseqs2 | Rapid prototyping and predictions without extensive computational resources [20] |

| AlphaFold DB | Repository of precomputed AF2 structures | Benchmarking and comparison of architectural variants [10] |

| ChimeraX with PICKLUSTER | Molecular visualization and analysis | Interpretation of protein complexes and interface scoring [20] |

| ESM-1b | Protein language model | Comparison with evolution-aware representations [22] |

| ATLAS MD Dataset | Molecular dynamics trajectories | Correlation of pLDDT with protein flexibility [14] |

| VoroMQA and VoroIF-GNN | Model quality assessment | Independent validation of interface predictions [20] |

The deconstruction of AF2's core components reveals a sophisticated integration of evolutionary information with physical and geometric constraints. The Evoformer's ability to reason about spatial relationships through triangular updates and the Structure Module's equivariant transformations represent fundamental advances in computational structure prediction. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these architectural details enables more informed interpretation of AF2 predictions, appropriate application to biological questions, and targeted modifications for specific use cases. While AF2 has limitations in predicting multiple conformational states and protein-ligand interactions, its core architectural principles provide a robust foundation for future methodological developments in structural bioinformatics.

Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) serve as a fundamental input for accurate protein structure prediction, providing the evolutionary constraints necessary to infer three-dimensional folds. Advanced artificial intelligence systems, most notably AlphaFold2, leverage the co-evolutionary information embedded within MSAs to achieve atomic-level accuracy [1] [23]. By analyzing patterns of correlated mutations across homologous sequences, these systems can identify residue pairs that are spatially close in the native structure, even if they are distant in the primary sequence. This application of evolutionary data addresses the immense complexity of the protein folding problem, acting as a bridge between the amino acid sequence and the final, functional protein architecture. The integration of MSAs has been the cornerstone upon which modern, highly accurate prediction pipelines have been built [24] [2].

The Role of MSAs in AlphaFold2 and Related Systems

Core Architectural Integration

In AlphaFold2, MSAs are processed at the very beginning of the neural network pipeline. The system's Evoformer module, a novel neural network block, is specifically designed to reason about the relationships within the MSA and between residue pairs [1]. The Evoformer treats the prediction as a graph inference problem, where the MSA representation (encoding information across homologous sequences) and the pair representation (encoding relationships between residues in the target sequence) continuously exchange information [1]. This is achieved through several innovative operations:

- MSA-to-Pair Information Transfer: An outer product operation sums over the MSA sequence dimension to update the pair representation in every Evoformer block [1].

- Triangle-shaped Updates within the Pair Representation: These operations enforce geometric consistency, using principles like the triangle inequality to reason about distances between three different residues, thereby making the pair representation more physically plausible [1].

This deep, iterative refinement of co-evolutionary signals allows AlphaFold2 to form a concrete structural hypothesis that is progressively refined throughout the network [1].

MSA-Free Prediction: The Emergence of Protein Language Models

While MSA-based methods set the standard for accuracy, the process of searching and constructing MSAs is computationally expensive, often taking tens of minutes to hours and becoming a bottleneck for high-throughput applications like large-scale virtual screening [24]. This limitation has spurred the development of MSA-free methods that use Protein Language Models (PLMs) [24].

These models, such as the one powering HelixFold-Single, are pre-trained on tens of millions of primary protein sequences using self-supervised learning [24]. During this pre-training, the PLM learns the statistical properties and evolutionary constraints of proteins, effectively embedding co-evolutionary knowledge directly into its parameters [24]. At inference time, the PLM can generate representations for a single sequence that serve as a substitute for the explicit co-evolutionary information found in an MSA. These representations are then fed into a structure module (often adapted from AlphaFold2) to predict 3D coordinates [24]. While their accuracy is particularly strong for proteins with large homologous families, they offer a substantial reduction in prediction time [24].

Table 1: Comparison of MSA-Based and MSA-Free Prediction Approaches

| Feature | MSA-Based (e.g., AlphaFold2) | MSA-Free (e.g., HelixFold-Single) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Input | Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) | Single amino acid sequence |

| Source of Co-evolution Data | Explicit retrieval from protein databases | Implicit, learned by a pre-trained Protein Language Model |

| Computational Bottleneck | MSA search and construction | Model inference (forward pass) |

| Typical Prediction Time | Minutes to hours | Seconds to minutes |

| Key Advantage | High accuracy, especially with deep MSAs | Speed, efficiency for high-throughput tasks |

Quantitative Performance and Benchmarking

Accuracy Assessment on Standardized Datasets

The performance of structure prediction methods is rigorously evaluated on blind test datasets like CASP14 and CAMEO. On these benchmarks, MSA-based AlphaFold2 demonstrates exceptional accuracy, producing predictions with a median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å (Cα root-mean-square deviation at 95% residue coverage), a level competitive with experimental structures [1]. MSA-free methods like HelixFold-Single have shown remarkable progress, achieving competitive accuracy with MSA-based methods on targets that have large homologous families (e.g., those with MSA depths >1,000 sequences) [24]. However, the performance of these MSA-free methods is correlated with the richness of homologous sequences available in nature for the target, underscoring that the underlying source of information remains evolutionary in origin [24].

Table 2: Performance Comparison on CASP14 and CAMEO Benchmarks

| Method | Input Type | Key Metric (CASP14) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | MSA | Backbone accuracy: 0.96 Å r.m.s.d.₉₅ [1] | Accuracy competitive with experimental structures [1]. |

| HelixFold-Single | Single Sequence | TM-score (CASP14 & CAMEO) [24] | Competitive with MSA-based methods on targets with large homologous families [24]. |

| AlphaFold2 (Single Sequence Input) | Single Sequence | TM-score [24] | Unsatisfactory accuracy without MSA or PLM assistance [24]. |

| RoseTTAFold | MSA | TM-score (CASP14 & CAMEO) [24] | Outperformed by HelixFold-Single on CAMEO [24]. |

Benchmarking MSA Quality Itself

The quality of an MSA directly impacts the accuracy of the downstream structure prediction. Benchmarks like QuanTest have been developed to objectively evaluate MSA quality by measuring Secondary Structure Prediction Accuracy (SSPA) [25]. The underlying assumption is that a better MSA will lead to more accurate secondary structure predictions. QuanTest can be scaled to test alignments of hundreds or thousands of sequences, providing a flexible framework for evaluating different MSA generation methods [25]. This approach correlates well with traditional benchmarks based on structural alignment, validating its use for assessing this critical input [25].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating an MSA for AlphaFold2 Prediction

This protocol details the steps for constructing a deep MSA to be used as input for AlphaFold2.

Sequence Retrieval: Using the target amino acid sequence, search against large protein sequence databases (e.g., UniRef90, BFD, MGnify) with a sensitive homology search tool like HHblits or JackHMMER.

- Objective: To collect a deep set of homologous sequences.

- Critical Parameters: Use multiple iterations to maximize sensitivity. The depth of the MSA (number of sequences) is a key factor for prediction accuracy.

MSA Construction: Process the search results into a single MSA file.

- Objective: To create a formatted alignment for AlphaFold2.

- Tools: The alignment is typically generated by the search tool itself (e.g., HHblits outputs an A3M format file).

Input to AlphaFold2: The resulting MSA file is fed into the AlphaFold2 neural network.

- Process: Within AlphaFold2, the Evoformer module processes the MSA to extract co-evolutionary signals and generate refined pair and sequence representations, which the Structure module then folds into a 3D atomic model [1].

Protocol 2: MSA-Free Prediction Using a Protein Language Model

This protocol outlines the workflow for high-speed structure prediction using a single sequence and a pre-trained PLM.

Model Pre-training (Typically Pre-computed): A large-scale Protein Language Model (e.g., with billions of parameters) is pre-trained on tens of millions of unlabelled protein sequences using masked language modeling [24].

- Objective: To embed evolutionary and biochemical knowledge into the model's parameters.

- Output: A pre-trained model that can convert a single sequence into informative representations.

Structure Prediction: The target amino acid sequence is input into the prediction pipeline (e.g., HelixFold-Single).

- Step 1: The pre-trained PLM encodes the single sequence into initial single and pair representations [24].

- Step 2: An adapter module may be used to project the PLM's outputs into the format required by the folding module [24].

- Step 3: The EvoformerS (a modified Evoformer) and Structure modules from AlphaFold2 refine these representations and predict the 3D coordinates of all atoms [24].

Protocol 3: Visualizing and Analyzing an MSA with NCBI's MSA Viewer

This protocol describes how to visualize an existing MSA to assess its quality and inspect conservation.

- Upload Alignment: Navigate to the NCBI MSA Viewer. Upload your alignment file (in FASTA or ASN format) via the "Upload Data" dialog [26].

- Navigate and Inspect:

- Use the Panorama view at the top to get an overview of alignment quality and coverage. Red areas indicate regions with a high proportion of mismatches [26].

- Zoom into specific regions by clicking and dragging on the ruler or in the Panorama view [26].

- Hover the mouse over any sequence to see a tooltip with detailed information about the aligned position and sequence ID [26].

- Set a Reference:

- Set a specific sequence (e.g., the target sequence) as the anchor row via the right-click context menu. This re-roots the alignment, and the "% Identity" column will show percent identity of every other sequence to this anchor [26].

- Alternatively, display a consensus sequence as the top row (for nucleotide alignments) to see the most common residue at each position [26].

Table 3: Key Resources for MSA-Based Protein Structure Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| UniRef90/BFD/MGnify | Database | Large protein sequence databases used for homologous sequence searches to build deep MSAs. |

| HHblits/JackHMMER | Software Tool | Sensitive homology search tools used for iterative MSA construction from sequence databases. |

| AlphaFold2 Open Source | Software | The open-source code for AlphaFold2, allowing researchers to run predictions with custom MSAs. |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Repository of over 200 million pre-computed AlphaFold2 structures; allows retrieval of models without local prediction [27]. |

| NCBI MSA Viewer | Web Tool | Visualizes alignments to assess quality, coverage, and conservation; supports custom anchor rows and coloring [26]. |

| Protein Language Models (e.g., ESM-2) | Software/Model | Pre-trained deep learning models that generate evolutionary representations from a single sequence for MSA-free prediction. |

Workflow and Data Visualization

Advanced Applications and Considerations

Special Cases: Predicting Structures of Chimeric Proteins

Predicting the structures of engineered chimeric proteins, such as those created by fusing a structured peptide to a scaffold protein, presents a unique challenge. Standard MSA construction for the entire chimera can lead to significantly reduced prediction accuracy [28]. An effective strategy to restore accuracy is a "windowed MSA" approach, where separate MSAs are generated for the individual components (e.g., the scaffold and the peptide tag) and these alignments are then appended together to form a composite MSA for the full chimeric protein [28]. This technique ensures that the co-evolutionary information specific to each domain is properly represented during the structure prediction process.

Visualization: Creating Optimal Color Schemes for MSAs

Effective visualization of MSAs is crucial for human interpretation. Traditional color schemes are based on manual assignments according to chemical properties. A more quantitative and reproducible approach leverages substitution matrices (e.g., BLOSUM62) to automatically generate color schemes [29]. This method uses an optimization algorithm (e.g., simulated annealing) to assign colors in a perceptually uniform color space (CIE Lab*), so that the perceptual difference between two amino acids' colors corresponds to their evolutionary distance as defined by the substitution matrix [29]. This ensures that visually similar colors are assigned to biochemically similar amino acids, directly aligning the visualization with the principles used to create the alignment itself.

AlphaFold2 represents a transformative advance in protein structure prediction, providing not only atomic coordinates but also essential confidence metrics that estimate the reliability of its predictions. Two scores are paramount for interpreting model quality: the pLDDT (predicted Local Distance Difference Test) and the PAE (Predicted Aligned Error). These metrics provide complementary information, with pLDDT quantifying local per-residue confidence and PAE assessing the relative positional accuracy between different parts of the structure. For researchers in structural biology and drug development, understanding these metrics is crucial for determining which parts of a predicted model can be trusted for further analysis and which require cautious interpretation. Proper utilization of pLDDT and PAE enables informed decision-making regarding model suitability for specific applications such as molecular docking, functional site analysis, and hypothesis generation.

Table 1: Interpretation guide for pLDDT scores

| pLDDT Score Range | Confidence Level | Structural Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 90 | Very high | High backbone and side chain accuracy; reliable for atomic-level analysis [30] |

| 70 - 90 | Confident | Generally correct backbone with potential side chain misplacement [30] |

| 50 - 70 | Low | Low confidence; potentially unstructured or poorly predicted [30] |

| < 50 | Very low | Very low confidence; likely intrinsically disordered or unstructured [30] |

Table 2: Interpretation guide for PAE values

| PAE Value (Å) | Confidence Level | Structural Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| < 5 | Low error | Confident relative positioning; domains are well-packed [31] [7] |

| 5 - 10 | Moderate error | Some uncertainty in relative positioning [31] |

| > 10 | High error | Low confidence in relative position/orientation; interpret with caution [31] |

Table 3: Key resources for working with AlphaFold2 confidence metrics

| Resource Type | Specific Tool/Resource | Function and Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Database Access | AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Access pre-computed models with interactive pLDDT and PAE visualizations [31] [32] |

| Software & Libraries | ColabFold | Open-source, accessible platform for running predictions with MMseqs2 for faster homology search [7] [33] |

| Programming Tools | Python Matplotlib library | Custom plotting of confidence metrics from raw AlphaFold2 output files [34] |

| Analysis Tools | AMBER force field | Energy minimization and relaxation of predicted models [34] |

Understanding pLDDT: Local Confidence Metric

Definition and Theoretical Basis

The predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT) is a per-residue measure of local confidence on a scale from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating greater confidence and typically more accurate prediction [30]. This metric is AlphaFold2's estimate of how well the prediction would agree with an experimental structure based on the local distance difference test Cα (lDDT-Cα), which assesses the correctness of local distances without requiring structural superposition [30]. The pLDDT score is stored in the B-factor column of output PDB files, replacing the experimental B-factor typically derived from X-ray crystallography [34].

Biological Interpretation of pLDDT Scores

pLDDT scores vary significantly along a protein chain, indicating regions of differential reliability [30]. As summarized in Table 1, scores above 90 indicate very high confidence with both backbone and side chains typically predicted accurately. Scores between 70 and 90 generally correspond to correct backbone predictions with potential side chain placement errors. Regions with scores below 50 indicate very low confidence, which typically arise for two reasons: naturally occurring intrinsic disorder or insufficient information for AlphaFold2 to make a confident prediction [30].

A critical application of pLDDT is identifying intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), which lack fixed structure under physiological conditions [30]. However, an important caveat exists: some IDRs undergo binding-induced folding upon interaction with molecular partners, and AlphaFold2 may predict these folded states with high pLDDT scores because they were present in the training data [30]. For example, eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein 2 (4E-BP2) is predicted with high confidence in a helical conformation that it only adopts in its bound state [30].

Important Limitations and Caveats

Despite its utility, pLDDT has important limitations. It does not measure confidence in the relative positions or orientations of different protein domains [30]. Additionally, recent research indicates that pLDDT values show no correlation with B-factors from experimental structures, suggesting they do not provide information about local conformational flexibility in globular proteins [33]. Therefore, while low pLDDT may indicate disorder, high pLDDT does not necessarily imply rigidity.

Understanding PAE: Global Confidence Metric

Definition and Theoretical Basis

The Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) is a quantitative measure representing the expected positional error in Ångströms for residue X if the predicted and true structures were aligned on residue Y [31] [35]. This pairwise error metric is visualized as a 2D heatmap where both axes represent residue numbers, and the color at each position (x,y) indicates the predicted error in residue x's position when the structures are aligned on residue y [31]. PAE fundamentally assesses AlphaFold2's confidence in the relative positioning of different structural regions, particularly between domains [31].

Interpretation of PAE Plots

PAE plots provide immediate visual insight into domain architecture and positional confidence. The plot always features a dark diagonal where residues are aligned against themselves, resulting in near-zero error by definition [31]. The biologically relevant information resides in the off-diagonal regions [31]. Well-defined blocks along the diagonal typically represent individual domains with high internal confidence, while the coloring between these blocks indicates confidence in their relative arrangement.

As shown in Table 2, low PAE values (typically <5 Å) between residues from different domains indicate confident relative positioning, while high values (>10 Å) suggest uncertainty in their spatial relationship [31] [7]. For example, the mediator of DNA damage checkpoint protein 1 (AF-Q14676-F1) exhibits two domains that appear close in the 3D model but have high PAE between them, indicating their relative positioning is essentially random and should not be interpreted biologically [31].

Important Limitations and Caveats

PAE has several important limitations. The metric is asymmetric, meaning the PAE value for (x,y) may differ from that for (y,x), particularly between loop regions with uncertain orientations [35]. Additionally, PAE should always be interpreted alongside pLDDT, as the two metrics are sometimes correlated—for instance, disordered regions with low pLDDT typically also exhibit large PAE relative to other protein regions [31].

Integrated Workflow for Metric Interpretation

Diagram 1: Confidence assessment workflow

Protocol for Confidence Assessment

- Retrieve confidence metrics: Access pLDDT scores from the B-factor column of PDB files or directly from resultdict.pkl files, and PAE data from resultdict.pkl files [34].

- Visualize pLDDT: Plot pLDDT scores along the protein sequence and map onto the 3D structure using a color scale (blue: high confidence, red: low confidence) [34].

- Analyze PAE plot: Generate and interpret the PAE heatmap, noting distinct domains along the diagonal and inter-domain confidence levels [31] [34].

- Integrate findings: Combine pLDDT and PAE information to form a comprehensive reliability assessment of different structural regions [31].

- Make informed decisions: Determine model suitability for intended applications based on integrated confidence assessment [7].

Experimental Protocol: Plotting Confidence Metrics

For researchers running local AlphaFold2 predictions, the following Python protocol enables visualization of confidence metrics from output files:

Advanced Applications and Caveats

Special Considerations for Drug Development

For researchers in pharmaceutical applications, several subtle aspects of confidence metrics warrant attention. While high pLDDT (>90) generally indicates reliable atomic positions, certain structural elements may show high confidence but still deviate from experimental structures. These include: enzyme active sites that require co-factors absent in predictions, flexible binding pockets that adopt different conformations upon ligand binding, and post-translationally modified residues that may be predicted in their modified or unmodified state [7].

Additionally, PAE plots are particularly valuable for assessing domain-domain interfaces in multi-domain proteins and protein complexes, which are often important drug targets. Low inter-domain PAE provides confidence in the relative orientation of domains, which is essential for understanding allosteric mechanisms and designing interface inhibitors [31] [7].

Protocol for Experimental Integration

When combining AlphaFold2 predictions with experimental data:

- Use pLDDT to guide model refinement: Focus experimental validation efforts on low pLDDT regions (<70) using techniques such as cryo-EM, SAXS, or NMR [7].

- Utilize PAE for multi-domain proteins: For proteins with multiple domains and high inter-domain PAE, consider solving domain structures individually or using hybrid modeling approaches [31] [7].

- Integrate with experimental data: Use NMR chemical shifts, cryo-EM density maps, or X-ray diffraction data to refine regions with moderate pLDDT (50-70) [7].

- Validate high-confidence predictions: Even regions with pLDDT >90 should be validated when used for critical applications like drug design [7].

pLDDT and PAE provide complementary dimensions of confidence assessment for AlphaFold2 protein structure predictions. pLDDT offers local, per-residue reliability estimates while PAE quantifies the confidence in relative positioning between different structural regions. Through systematic application of the protocols outlined in this document, researchers can make informed decisions about model reliability, identify regions requiring experimental validation, and avoid overinterpretation of low-confidence predictions. As AlphaFold2 continues to transform structural biology, appropriate use of these confidence metrics remains essential for responsible application in research and drug development.

From Sequence to Therapy: Practical Applications of AlphaFold2 in Drug Discovery and Biology

Enhancing Target Identification and Validation for Novel Diseases and Pathogens

The emergence of novel diseases and pathogens presents a significant challenge to global health, with the initial phase of target identification and validation being a critical bottleneck in the drug discovery pipeline. This process involves identifying biomolecules, typically proteins, that play a key role in the disease pathophysiology and confirming that modulating their activity can produce a therapeutic effect. For novel pathogens, the scarcity of experimental structural information has historically hindered rapid therapeutic development. The integration of artificial intelligence (AI)-driven protein structure prediction tools, particularly AlphaFold2 (AF2), is transforming this paradigm by providing immediate, high-accuracy structural models for previously uncharacterized proteins. This Application Note details protocols for leveraging AF2 to accelerate and enhance target identification and validation for novel diseases, providing researchers with a structured framework to prioritize therapeutic targets efficiently [36] [37].

AF2 has demonstrated an accuracy comparable to high-resolution experimental methods for many proteins, providing reliable three-dimensional structural data [10]. This capability is paramount for novel pathogens, where experimental structures are often absent. The AlphaFold database, hosted at EMBL-EBI, provides free access to over 200 million protein structure predictions, dramatically expanding the structural landscape available to researchers [36] [10]. By applying the methodologies outlined herein, scientists can rapidly assess the druggability of potential targets—evaluating their accessibility to small molecules or biologicals—based on predicted structure, thereby de-risking and accelerating the early stages of drug discovery.

AlphaFold2 in the Drug Discovery Workflow

The drug discovery process for a novel pathogen begins with genomic and proteomic data, from which candidate protein targets are selected. The following workflow illustrates the integrated role of AlphaFold2 in the subsequent target identification and validation stages.

Quantitative Assessment of AF2 Models for Target Prioritization

The confidence in an AF2-predicted structure is quantitatively assessed by the predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT) score, which should be the primary filter for model utility. The following table summarizes the interpretation of pLDDT scores and their implications for different applications in target identification [36].

Table 1: Interpreting AlphaFold2 pLDDT Scores for Target Assessment

| pLDDT Range | Confidence Level | Suitability for SBDD | Recommended Use in Target ID |

|---|---|---|---|

| 90 - 100 | Very High | High | Confident identification of binding pockets; Virtual Screening |

| 70 - 80 | Confident | Moderate | Binding site analysis possible; useful for construct design |

| 50 - 70 | Low | Low | Low confidence for binding sites; identifies domain boundaries |

| 0 - 50 | Very Low | Not Suitable | Poorly modeled regions; indicative of intrinsic disorder |

As a rule-of-thumb, structures with pLDDT > 80 are considered comparable to experimental data and are suitable for in silico modeling and virtual screening purposes. Regions with low pLDDT scores often correspond to flexible loops or linker regions, which can provide vital information for designing protein constructs for subsequent experimental expression and functional studies [36].

Application Example: The Hepatitis E Virus (HEV-3) Replicase

A practical application involved modeling the large replicase polyprotein of the Hepatitis E virus. AF2 generated models for five non-structural proteins with varying confidence levels. These models were then systematically ranked for their potential as drug targets based on: (a) the AF2 confidence (pLDDT) of the predicted structure, (b) the size and accessibility of binding pockets, (c) the existence of ligand-binding data on structurally similar proteins in public databases, and (d) the uniqueness of the predicted protein fold to inform drug selectivity [36]. This structured approach demonstrates how to triage multiple potential targets from a single pathogen.

Experimental Protocols for Target Validation

Once a potential target is identified and a high-confidence AF2 model is obtained, the following experimental protocols can be employed for validation.

Protocol: Binding Pocket Identification and Analysis

This protocol details the steps for identifying and characterizing potential binding pockets on an AF2-predicted structure [36].

I. Objectives

- To identify cavities on the protein surface that could bind small molecules.

- To characterize the physicochemical properties of the pocket (e.g., size, hydrophobicity, charge).

II. Materials and Reagents

- Hardware: A standard desktop computer or high-performance computing (HPC) node.

- Software:

- Molecular Visualization System: UCSF ChimeraX or PyMOL.

- Pocket Detection Tool: FPOCKET, CASTp, or the built-in cavity detection in visualization software.

- Input Data: The AF2-predicted structure file in PDB format and the corresponding pLDDT data file.

III. Procedure

- Model Preparation:

- Load the predicted structure (.pdb file) into your molecular visualization software.

- Analyze the pLDDT scores by coloring the structure according to the per-residue confidence. Disregard regions with very low confidence (pLDDT < 50) during initial analysis.

- Pocket Detection:

- Run a pocket detection algorithm (e.g., FPOCKET) on the prepared structure.

- The software will output a list of predicted pockets, often ranked by a score or volume.

- Pocket Characterization:

- Visually inspect the top-ranked pockets. A promising binding pocket is typically a large, concave cavity with diverse amino acids that can form multiple interactions with a ligand.

- Analyze the residue composition of the pocket (hydrophobic, polar, charged).

- Check public databases (e.g., PDBe, UniProt) for known functional sites or homologous structures with bound ligands that might map to the predicted pocket.

- Output:

- A prioritized list of binding pockets for further investigation.

Protocol: Using AF2 Models for Experimental Structure Determination

High-confidence AF2 models can be used as initial models for molecular replacement in X-ray crystallography or for fitting into cryo-EM density maps, significantly accelerating experimental structure determination [36].

I. Objectives

- To solve the experimental phase problem in X-ray crystallography using an AF2 model.

- To aid in the interpretation and building of a structural model from a cryo-EM density map.

II. Materials and Reagents

- Experimental Data: X-ray diffraction data set or a cryo-EM density map.

- Software:

- Molecular Replacement: Phaser (within Phenix suite), MOLREP.

- Cryo-EM Fitting: COOT, UCSF ChimeraX.

- Input Data: The AF2-predicted structure file (.pdb).

III. Procedure for Molecular Replacement (X-ray Crystallography)

- Prepare the AF2 Model:

- Remove low-confidence regions (e.g., pLDDT < 70) from the AF2 model, as these can hinder successful molecular replacement. These regions can be deleted or converted to poly-alanine.

- Run Molecular Replacement:

- Use the trimmed AF2 model as a search model in a molecular replacement program like Phaser.

- The program will attempt to orient and position your AF2 model within the crystallographic unit cell.

- Refinement and Validation:

- If molecular replacement is successful, proceed with iterative cycles of model building (in COOT) and refinement (in Phenix.refine or REFMAC).

- Validate the final model using standard geometric and statistical criteria.

Protocol: Functional Validation via Assay Development

AF2 models can guide the design of experiments for functional validation, such as the design of expression constructs for stable, active proteins [36].

I. Objectives

- To design protein constructs that are stable and functionally active for biochemical assays.

- To identify potential functional domains and flexible linkers from the predicted structure.

II. Materials and Reagents

- Wet-lab reagents for molecular biology (PCR, cloning), protein expression (e.g., E. coli, insect cell systems), and purification (chromatography systems).

- Assay reagents specific to the hypothesized protein function (e.g., substrates for an enzyme).

III. Procedure

- Domain Identification:

- Visually inspect the AF2 model and its pLDDT plot. Sharp drops in pLDDT between two high-confidence regions often indicate domain boundaries or flexible linkers.

- Construct Design:

- Design DNA constructs that express individual, high-confidence domains (pLDDT > 80) as well as the full-length protein.

- Avoid including long, low-confidence regions (pLDDT < 50) if they are not essential for function, as they may hinder expression and folding.

- Expression and Purification:

- Clone, express, and purify the designed constructs using standard methodologies.

- Functional Assay:

- Develop an activity assay based on the predicted function of the target (e.g., enzymatic assay, binding assay).

- Test the activity of the purified full-length protein and individual domains. Successfully expressing an active domain confirms its functional independence and validates the structural prediction.

The Scientist's Toolkit

The following table lists key reagents and computational tools essential for implementing the protocols described in this document.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for AF2-Driven Target Identification

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Access Link/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold DB | Database | Access to pre-computed AF2 structures for a vast number of proteins. | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ |

| ColabFold | Software Suite | Rapidly run AF2 predictions using MMSeqs2 and Google Colab. | https://github.com/sokrypton/ColabFold |

| ChimeraX | Software | Visualize AF2 structures, analyze pLDDT, and perform basic structural analysis. | https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimerax/ |

| FPOCKET | Software | Open-source tool for detection of protein binding pockets. | https://github.com/DisorderedDev/FPocket |

| Phenix Suite | Software | Software for macromolecular structure determination (e.g., Molecular Replacement). | https://phenix-online.org/ |

| SKEMPI 2.0 | Database | Database of binding free energy changes upon mutation; useful for validation. | [38] |