AlphaFold2 vs RoseTTAFold: A Comprehensive Accuracy Comparison for Research and Drug Development

This article provides a definitive comparison of AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold, two revolutionary AI-powered protein structure prediction tools.

AlphaFold2 vs RoseTTAFold: A Comprehensive Accuracy Comparison for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a definitive comparison of AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold, two revolutionary AI-powered protein structure prediction tools. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores their fundamental architectures, confidence metrics, and performance across diverse protein classes, including globular proteins, complexes, and intrinsically disordered regions. We deliver practical guidance on model selection, troubleshooting low-confidence predictions, and integrating these tools with experimental data for robust structural biology workflows. The analysis synthesizes current capabilities and limitations, offering a forward-looking perspective on how these technologies are expanding the druggable proteome and shaping the future of biomedical research.

Core Architectures: Deconstructing AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold's AI Engines

The development of AlphaFold2 (AF2) by Google DeepMind marked a watershed moment in computational biology, essentially resolving the decades-old protein structure prediction problem by achieving accuracy competitive with experimental methods [1] [2]. At the core of this breakthrough lies the Evoformer, a novel neural network architecture that serves as the model's computational engine. The Evoformer's innovative design enables the synergistic processing of evolutionary and structural information, allowing it to predict the three-dimensional coordinates of all heavy atoms in a protein from its amino acid sequence alone [1]. This transformative technology has spurred a revolution across biological sciences, facilitating applications ranging from mechanistic studies of protein function to rational drug design by providing high-confidence structural models for millions of proteins [2] [3]. Understanding the Evoformer's operation—specifically how it handles multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and pair representations—is crucial for researchers leveraging these predictions and for developers seeking to build upon this architectural foundation. This analysis examines the inner workings of the Evoformer, contextualizing its performance against its contemporary competitor, RoseTTAFold, within the broader landscape of protein structure prediction research.

Architectural Breakdown: The Evoformer's Dual-Representation System

The Evoformer operates on a fundamental principle of joint representation learning, progressively refining two distinct but interconnected data structures throughout its 48-block architecture [1]. The following diagram illustrates the flow of information and the key components within this system:

Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Representation

The MSA representation is structured as an N~seq~ × N~res~ array, where N~seq~ represents the number of homologous sequences in the alignment, and N~res~ denotes the number of residues in the protein [1]. Each column in this matrix corresponds to an individual residue position in the input sequence, while each row represents a different homologous sequence. This arrangement allows the Evoformer to detect evolutionary patterns and co-evolutionary signals across related proteins. The model initializes this representation with the raw MSA data, which is subsequently processed through specialized attention mechanisms. Specifically, the Evoformer employs axial attention—a computationally efficient variant that applies attention either row-wise or column-wise across the MSA [1]. During row-wise attention, the network incorporates pairwise information as a bias, creating a crucial information bridge between the two representations. This design enables the model to identify evolutionarily correlated mutations, which often indicate spatial proximity in the folded structure, thereby transforming evolutionary statistics into geometric constraints.

Pair Representation

Simultaneously, the Evoformer maintains and refines a pair representation structured as an N~res~ × N~res~ array [1]. Each element in this matrix encodes the relationship between two residues, capturing potential spatial interactions regardless of their linear separation in the amino acid sequence. This representation is progressively enriched with information about the physical and evolutionary constraints acting on residue pairs. The most geometrically insightful components operating on this representation are the triangle multiplicative updates and triangle attention [1]. These operations are specifically designed to enforce consistency within triplets of residues, effectively reasoning about the triangle inequality constraints that must be satisfied in any physically plausible three-dimensional structure. For example, the triangle multiplicative update uses information from two edges of a residue triplet to infer properties of the third edge, directly embedding principles of structural geometry into the network's reasoning process. This explicit encoding of spatial relationships enables the model to maintain global structural consistency throughout the prediction process.

Information Exchange Between Representations

A defining innovation of the Evoformer is its continuous, bidirectional information exchange between the MSA and pair representations [1]. Unlike previous approaches that performed limited communication between these data types, the Evoformer facilitates rich interaction through two primary mechanisms:

- MSA to Pair: The model computes an element-wise outer product that is summed over the MSA sequence dimension, allowing evolutionary information to directly influence the evolving understanding of residue-pair relationships.

- Pair to MSA: During axial attention operations within the MSA representation, the network projects additional logits from the pair representation to bias the attention calculations [1]. This enables spatial constraints to refine the interpretation of evolutionary signals.

This tight integration creates a powerful feedback loop where evolutionary evidence strengthens geometric reasoning, and geometric constraints help interpret evolutionary patterns. Through repeated blocks of such processing, the Evoformer progressively refines its structural hypothesis, transforming initial sequence data into a detailed blueprint for atomic-level structure prediction.

Performance Comparison: AlphaFold2 vs. RoseTTAFold

The Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments serve as the gold-standard benchmark for evaluating prediction accuracy in a blind testing framework [3]. The performance metrics from CASP14, where AlphaFold2 made its debut, clearly demonstrate its revolutionary advancement.

Table 1: CASP14 Performance Comparison (Backbone Accuracy)

| Method | Median Backbone Accuracy (Cα RMSD₉₅) | 95% Confidence Interval | All-Atom Accuracy (RMSD₉₅) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | 0.96 Å | 0.85–1.16 Å | 1.5 Å |

| Next Best Method | 2.8 Å | 2.7–4.0 Å | 3.5 Å |

Data sourced from Jumper et al. (2021) Nature [1]

The dramatic performance gap—with AlphaFold2 achieving nearly three times greater accuracy than the next best method in CASP14—underscores the transformative impact of its architecture, particularly the Evoformer module [1]. To provide context, a carbon atom is approximately 1.4 Å in diameter, meaning AlphaFold2's predictions approach atomic-level precision. When compared specifically to RoseTTAFold, which was developed concurrently by the Baker lab, both systems represent substantial advances over previous methods, though important distinctions exist.

Table 2: Architectural and Performance Comparison

| Feature | AlphaFold2 | RoseTTAFold |

|---|---|---|

| Core Architecture | Evoformer with dual MSA/pair representations | Three-track network (1D, 2D, 3D) |

| Information Flow | Continuous, bidirectional between MSA and pair | Simultaneous reasoning across sequence, distance, 3D |

| Key Innovation | Triangle attention & multiplicative updates | Integrated 3D coordinate track |

| CASP14 Performance | Atomic accuracy (0.96 Å backbone) | Approaching AlphaFold2 accuracy |

| Strengths | Exceptional accuracy for single chains; precise atomic coordinates | Flexible architecture; good performance with less computational resources |

| Limitations | High computational demand; originally limited to monomers | Generally slightly lower accuracy than AF2 |

Data synthesized from Jumper et al. (2021) and Baek et al. (2021) as cited in [4] [5]

While both systems leverage deep learning and evolutionary information, AlphaFold2's specialized Evoformer architecture, particularly its triangle-based geometric reasoning, provides a distinct advantage in achieving experimental-level accuracy [1] [5]. The three-track design of RoseTTAFold allows it to simultaneously process sequence, distance, and coordinate information, enabling effective structure prediction while potentially offering implementation advantages in certain scenarios [5]. Subsequent developments have seen both systems expanded to predict complexes—AlphaFold2 through AlphaFold-Multimer and RoseTTAFold through its all-atom version, which can handle proteins, nucleic acids, and small molecules [4] [6].

Experimental Validation and Methodologies

The extraordinary performance of AlphaFold2 was rigorously validated through multiple experimental frameworks, with methodologies designed to ensure unbiased assessment of its predictive capabilities.

CASP14 Blind Assessment

The Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) provides the most authoritative evaluation of protein structure prediction methods [1] [3]. In CASP14, AlphaFold2 was tested on a set of recently solved protein structures that had not yet been deposited in the Protein Data Bank or publicly disclosed. This double-blind format prevents participants from tailoring their methods to specific targets. The assessment uses multiple metrics to evaluate accuracy:

- Cα RMSD₉₅: Measures the root-mean-square deviation of Cα atoms after superposition, calculated over 95% of residues to exclude unstructured terminal regions.

- lDDT-Cα: A local distance difference test that evaluates the agreement of inter-atomic distances without global superposition.

- TM-score: A template modeling score that measures global fold similarity.

Across these metrics, AlphaFold2 demonstrated accuracy competitive with experimental methods in a majority of cases, greatly outperforming all other participating methods [1].

Post-CASP Validation on PDB Structures

To ensure the CASP14 performance was not specific to the competition targets, the DeepMind team further validated AlphaFold2 on a large sample of protein structures released after the training data cutoff [1]. This analysis confirmed that the high accuracy generalized to novel structures, with the model's internal confidence measure (pLDDT) reliably predicting the actual accuracy of the predictions. This reliability metric is particularly valuable for researchers using AlphaFold2 models in practice, as it allows them to identify regions of uncertain structure that may require experimental validation.

Comparative Experimental Framework

The DPL3D platform provides an integrated framework for comparing multiple prediction tools, including AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, RoseTTAFold All-Atom, and trRosettaX-Single [4]. This platform enables systematic benchmarking through:

- Standardized Input Processing: All methods process identical input sequences under consistent computational environments.

- Comprehensive Database Integration: The platform includes extensive molecular structure databases (210,180 entries) for template-based comparisons.

- Unified Visualization: Predictions from different tools can be visualized and compared using the same rendering engine and settings.

Such standardized frameworks are crucial for objective performance comparison, as they eliminate variability in implementation details, input data quality, and evaluation metrics that can complicate cross-study comparisons.

Researchers leveraging AlphaFold2 and related technologies in their structural bioinformatics work rely on several key resources and tools:

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for Protein Structure Prediction

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Provides pre-computed AF2 predictions for ~200 million proteins | Public (EMBL-EBI) |

| DPL3D Platform | Web Server | Integrated platform for structure prediction & visualization | http://nsbio.tech:3000 |

| MMseqs2 | Software Tool | Rapid MSA construction for custom sequences | Open source |

| ColabFold | Web Service/Software | Streamlined AF2 implementation with MMseqs2 integration | Public Google Colab |

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Database | Repository of experimentally determined structures | Public (RCSB) |

| UniRef | Database | Clustered sets of protein sequences for MSA generation | Public |

Data synthesized from multiple sources [4] [3]

These resources dramatically lower the barrier to entry for researchers wishing to utilize state-of-the-art structure prediction in their work. The AlphaFold Database, in particular, has become an indispensable resource, with over 1.4 million users accessing predicted structures for various research applications [5]. For cases not covered by the database (such as novel mutations or designed proteins), tools like ColabFold and DPL3D provide user-friendly interfaces for generating custom predictions.

Emerging Frontiers and Future Directions

While AlphaFold2 represents a monumental achievement, ongoing research continues to address its limitations and expand its capabilities. Current frontiers include:

- Conformational Dynamics: AlphaFold2 typically predicts a single static structure, but proteins often exist as ensembles of conformations [7] [8]. New approaches like Distance-AF incorporate distance constraints to model alternative states, while MSA manipulation techniques can generate conformational diversity [7] [8].

- Complex Biomolecular Interactions: The recent release of AlphaFold3 extends the architectural principles beyond single proteins to complexes containing nucleic acids, ligands, and modified residues [6].

- Computational Efficiency: New architectures like Pairmixer aim to streamline the computationally expensive Evoformer while maintaining accuracy, potentially enabling larger-scale applications [9].

- Integration with Experimental Data: Methods like AlphaLink and RASP incorporate experimental distance restraints from cross-linking mass spectrometry or NMR into the prediction process [8].

These developments ensure that the core innovations of the AlphaFold2 Evoformer will continue to drive advances in structural biology, even as the technology evolves to address more complex biological questions.

The AlphaFold2 Evoformer represents a paradigm shift in protein structure prediction, achieving unprecedented accuracy through its sophisticated dual-pathway architecture that jointly reasons about evolutionary relationships and spatial constraints. The continuous, bidirectional information flow between MSA and pair representations, coupled with specialized geometric reasoning through triangle operations, enables the model to transform amino acid sequences into experimentally comparable structural models. While RoseTTAFold offers a compelling alternative with its three-track architecture, the Evoformer's design underpins AlphaFold2's exceptional performance as demonstrated in rigorous blind assessments. The availability of these tools through accessible platforms and databases has democratized structural biology, empowering researchers across biological and medical disciplines to leverage high-quality structural models in their work. As the field progresses beyond static monomer prediction toward dynamic complexes and functional states, the core architectural principles established by the Evoformer will undoubtedly continue to influence the next generation of biomolecular structure prediction tools.

In the field of computational biology, the accurate prediction of protein structures from amino acid sequences represents a monumental challenge. Within the context of ongoing AlphaFold2 versus RoseTTAFold accuracy research, a critical differentiator has emerged: RoseTTAFold's unique three-track neural network architecture. This system simultaneously processes one-dimensional sequence data, two-dimensional inter-residue distance maps, and three-dimensional coordinate spaces, enabling iterative information flow that collectively reasons about protein structure. While objective evaluations from CASP14 and Continuous Automated Model Evaluation (CAMEO) experiments consistently place RoseTTAFold's accuracy below AlphaFold2, its computational efficiency and particular strengths in modeling specific structural elements like antibody H3 loops present a compelling alternative for researchers. This review objectively compares RoseTTAFold's performance against AlphaFold2, SWISS-MODEL, and other alternatives, examining architectural innovations, benchmark results, and practical applications that define its position in the current protein structure prediction landscape.

Proteins perform essential biological functions through their three-dimensional structures, yet determining these structures experimentally remains time-consuming and resource-intensive. The bi-annual Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) meetings have demonstrated that deep learning methods like AlphaFold and RoseTTAFold significantly outperform traditional approaches that explicitly model the folding process [10]. These advancements have revolutionized structural biology, but key differences in architecture, accuracy, and accessibility distinguish the leading methods.

RoseTTAFold, developed by the Baker lab, represents a significant open-source achievement in protein structure prediction. As reported in Science, this deep learning approach can compute protein structures in as little as ten minutes on a single gaming computer [11]. The method's name derives from its three-track neural network that simultaneously considers patterns in protein sequences, amino acid interactions, and possible three-dimensional structures. This architectural innovation enables the network to collectively reason about the relationship between a protein's chemical parts and its folded structure through continuous information flow between representation levels.

Architectural Framework: The Three-Track Innovation

Core Architecture Components

RoseTTAFold's architecture organizes information processing along three parallel tracks:

1D Sequence Track: Processes multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) that capture evolutionary information from related proteins. MSAs are input as a matrix of dimensions N × L, where rows represent the number of sequences in the MSA and columns represent sequence positions. Each amino acid and gap is represented as one of 21 character-level tokens mapped to an embedding vector [12].

2D Distance Map Track: Analyzes pair features representing likely interactions between residues. This track processes information about residue co-evolution and spatial relationships, creating a foundation for understanding secondary and tertiary structure formation through hydrogen bonds that form alpha helices and beta sheets [12].

3D Coordinate Track: Operates directly on three-dimensional backbone coordinates, employing SE(3)-equivariant transformations to refine atomic coordinates. This track enables direct reasoning about spatial arrangements and structural constraints [10].

Information Integration Mechanism

The revolutionary aspect of RoseTTAFold lies not merely in having three processing tracks, but in how they interact. Information flows back and forth between the 1D amino acid sequence information, the 2D distance map, and the 3D coordinates, allowing the network to collectively reason about relationships within and between sequences, distances, and coordinates [10]. This integrated reasoning enables more effective extraction of sequence-structure relationships than architectures that process information sequentially.

The network begins by creating initial embeddings for both MSA and pair features. The MSA representation captures sequence variation, while pair features identify likely interactions between residues. These embeddings are refined through a series of processing steps that include axial attention (row-wise followed by column-wise attention) and pixel-wise attention, which selectively attends to informative context locations for each position in the feature matrix [12].

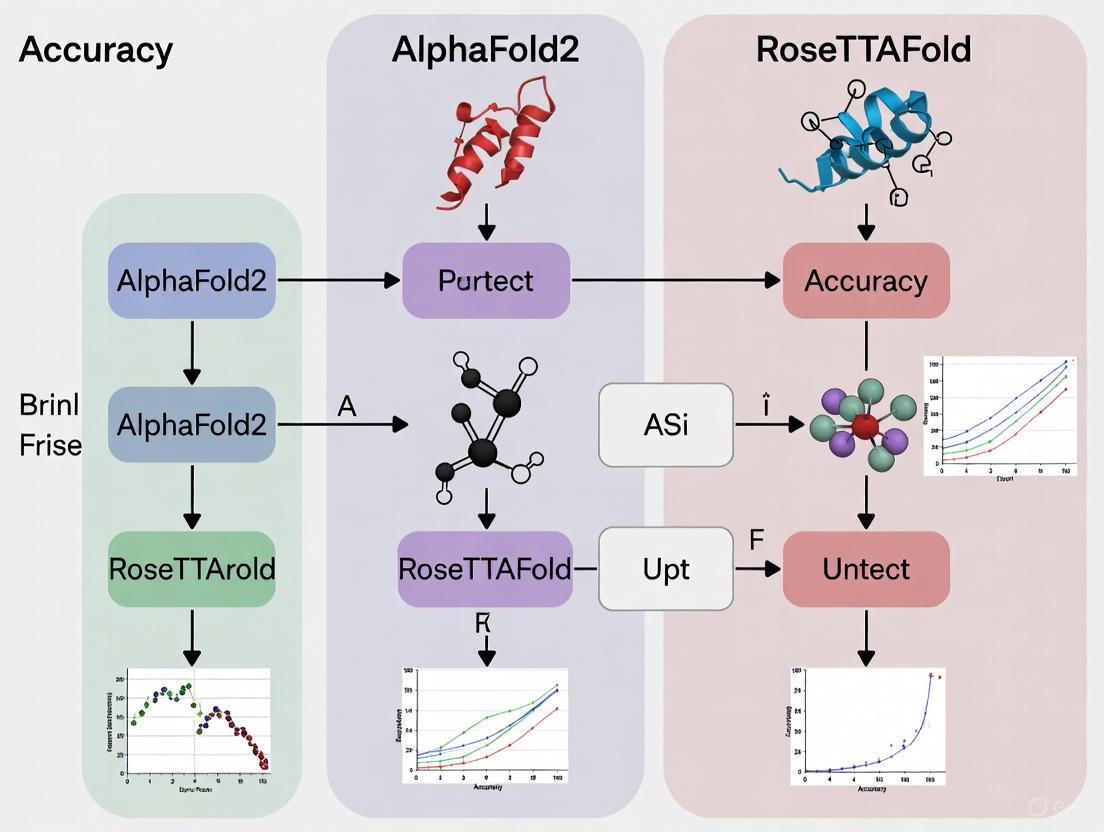

Figure 1: RoseTTAFold's three-track architecture with bidirectional information flow between 1D, 2D, and 3D processing tracks.

Performance Benchmarks: Objective Comparison with Alternatives

CASP14 Assessment Results

The Critical Assessment of Structure Prediction (CASP) provides blind tests for evaluating protein structure prediction methods. In CASP14, RoseTTAFold demonstrated significant accuracy, though it did not surpass AlphaFold2's performance. As shown in Table 1, RoseTTAFold's three-track model outperformed the next best methods after AlphaFold2, including trRosetta (BAKER-ROSETTASERVER and BAKER), but still trailed behind DeepMind's solution [10].

Table 1: CASP14 Performance Comparison of Protein Structure Prediction Methods

| Method | Global Distance Test (GDT) | Key Architectural Features | Hardware Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | Highest (Exact values not reported in sources) | Two-track network (1D + 2D) with final SE(3)-equivariant refinement | Several GPUs for days per prediction |

| RoseTTAFold | High (Below AlphaFold2) | Three-track network with simultaneous 1D, 2D, 3D processing | Single GPU (10 minutes for proteins <400 residues) |

| trRosetta | Moderate | Earlier deep learning approach using distance maps | Moderate requirements |

| SWISS-MODEL | Variable (Template-dependent) | Traditional homology modeling | Server-based, minimal local resources |

The relatively lower compute cost of RoseTTAFold makes it accessible for a broader research community. While DeepMind reported using several GPUs for days to make individual predictions, RoseTTAFold predictions are made in a single pass through the network. Following sequence and template search (~1.5 hours), the end-to-end version requires approximately 10 minutes on an RTX2080 GPU to generate backbone coordinates for proteins with less than 400 residues [10].

Continuous Automated Model Evaluation (CAMEO)

The CAMEO experiment provides ongoing blind assessment of structure prediction servers as new protein structures are submitted to the PDB. In evaluations conducted from May 15 to June 19, 2021, RoseTTAFold outperformed all other servers on 69 medium and hard targets, including Robetta, IntFold6-TS, BestSingleTemplate, and SWISS-MODEL [10]. This real-world performance demonstrates RoseTTAFold's practical utility for researchers needing accurate protein models.

Antibody-Specific Modeling Performance

Antibody structure prediction presents unique challenges, particularly for the highly variable H3 loop responsible for antigen recognition. A 2022 study specifically evaluated RoseTTAFold's performance in antibody modeling compared to SWISS-MODEL and ABodyBuilder [13].

Table 2: Antibody Modeling Performance Comparison

| Method | Overall Accuracy | H3 Loop Prediction | Approach | Dependencies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RoseTTAFold | Lower than specialized tools | Better than ABodyBuilder, comparable to SWISS-MODEL | End-to-end deep learning | Minimal template dependency |

| SWISS-MODEL | High (Template-dependent) | Accurate when templates available | Homology modeling | Requires homologous structures |

| ABodyBuilder | Higher than RoseTTAFold | Less accurate than RoseTTAFold | specialized antibody modeling | Combination of homology and ab initio |

The research found that while RoseTTAFold could accurately predict 3D structures of antibodies, its overall accuracy was not as good as SWISS-MODEL or ABodyBuilder. However, for the particularly challenging H3 loop, RoseTTAFold exhibited better accuracy than ABodyBuilder and was comparable to SWISS-MODEL, especially for templates with a Global Model Quality Estimate (GMQE) score under 0.8 [13]. This suggests RoseTTAFold's architecture provides particular advantages for modeling variable regions where template information may be limited.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard RoseTTAFold Implementation

The typical workflow for RoseTTAFold structure prediction involves several methodical steps as implemented in benchmark studies:

Input Preparation: Protein sequences are retrieved from databases like IMGT/3Dstructure-DB and IMGT/2Dstructure-DB, with chains renumbered to begin from '1' using tools like Chimera to ensure consistent residue numbering for structural comparisons [13].

Multiple Sequence Alignment: 'make_msa.sh' script executes HHblits to perform MSAs for both heavy and light chains, using the latest HH-suite-3.3.0 compiled from GitHub. HHfilter excludes paired sequences with sequence identity over 90% or sequence coverage less than 75% compared with the target sequence [13].

Paired MSA Generation: 'makejointMSA_bacterial.py' pairs MSAs, creating the joint representation essential for understanding inter-chain interactions in multi-chain proteins.

Structure Prediction: 'predict_complex.py' executes the core three-track network prediction. The network takes discontinuous crops of the input sequence consisting of two discontinuous sequence segments spanning 260 residues to manage memory constraints while maintaining contextual awareness.

Model Refinement: Rosetta FastRelax adds side chains and refines the model through energy minimization [13].

Figure 2: Standard RoseTTAFold workflow for protein structure prediction.

Antibody Modeling Experimental Design

The antibody-specific assessment followed a rigorous protocol to ensure unbiased evaluation:

Test Set Generation: Researchers retrieved antibody sequences from the international ImMunoGeneTics information system (IMGT) database, following IMGT definitions for CDR loops. From SAbDab, they generated a nonredundant set of 767 unbound antibodies with maximum sequence identity of 80%, resolution cut-off lower than 3.2 Å, and including both VH and VL chains [13].

Comparative Modeling: 30 antibodies were selected as test cases, with structures predicted using RoseTTAFold, SWISS-MODEL, and ABodyBuilder using identical input sequences.

Quality Assessment: Models were evaluated using Global Model Quality Estimate (GMQE) scores stratified into three ranges, with particular attention to CDR loop accuracy, especially the challenging H3 loop [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for RoseTTAFold Implementation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| HH-suite | Multiple sequence alignment generation | Constructing MSAs from input sequences |

| Rosetta FastRelax | Side chain addition and model refinement | Final stage of structure prediction |

| SAbDab Database | Source of antibody structural information | Benchmarking and test set generation |

| IMGT Database | Immunogenetic information resource | Antibody sequence retrieval and CDR definition |

| PyRosetta | Python interface to Rosetta molecular modeling | All-atom structure generation from network outputs |

| Chimera | Molecular visualization and analysis | Structure comparison and residue renumbering |

Extensions and Specialized Applications

ProteinComplex Modeling with DeepSCFold

Recent advancements have built upon RoseTTAFold's foundation to address the challenge of protein complex prediction. DeepSCFold, reported in Nature Communications in 2025, uses sequence-based deep learning models to predict protein-protein structural similarity and interaction probability [14]. This approach leverages RoseTTAFold's core principles but extends them to specifically capture inter-chain interactions, demonstrating improvements of 11.6% and 10.3% in TM-score compared to AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 respectively on CASP15 multimer targets [14].

For antibody-antigen complexes from the SAbDab database, DeepSCFold enhanced prediction success rates for binding interfaces by 24.7% and 12.4% over AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 respectively [14]. These results demonstrate how RoseTTAFold's architectural concepts can be effectively specialized for particular biological challenges.

Protein Design with ProteinGenerator

RoseTTAFold has also been adapted for protein design through ProteinGenerator (PG), a sequence space diffusion model described in Nature Biotechnology [15]. This approach begins from a noised sequence representation and generates sequence-structure pairs by iterative denoising, guided by desired sequence and structural attributes.

The system has been successfully used to design thermostable proteins with varying amino acid compositions, internal sequence repeats, and cage bioactive peptides like melittin [15]. Experimental characterization of 42 unconditionally generated 70-80 residue proteins showed that 32 were soluble and monomeric by size-exclusion chromatography, with circular dichroism confirming designed secondary structure and stability up to 95°C [15]. This demonstrates RoseTTAFold's utility not just for prediction, but for the de novo creation of functional proteins.

Therapeutic Peptide Design

RFdiffusion, a variation of RoseTTAFold for protein design, has been applied to create short therapeutic peptides targeting specific protein interactions. In a proof-of-concept study focusing on Keap1, a key regulator in the Keap1/Nrf2 antioxidant pathway, researchers combined RFdiffusion with ProteinMPNN to design peptide sequences that interact with specific binding subpockets [16]. This integrated computational approach identified eight top candidates with strong binding affinity and favorable biophysical characteristics, validated through molecular dynamics simulations [16].

Within the broader context of AlphaFold2 versus RoseTTAFold accuracy research, the evidence reveals a nuanced landscape where architectural choices create distinct performance profiles. RoseTTAFold's three-track network with integrated 1D, 2D, and 3D information flow represents a significant innovation that enables competitive prediction accuracy with substantially lower computational requirements.

While objective benchmarks consistently show AlphaFold2 maintains superior overall accuracy, RoseTTAFold excels in specific domains including antibody H3 loop prediction, rapid modeling on accessible hardware, and adaptability for protein design applications. These strengths make it particularly valuable for researchers without access to extensive computational resources and for specialized applications requiring specific structural insights.

The extensions of RoseTTAFold's core architecture in tools like DeepSCFold for complex prediction and ProteinGenerator for protein design demonstrate the framework's versatility and ongoing relevance. As protein structure prediction continues to evolve, RoseTTAFold's three-track architecture remains a foundational approach that balances accuracy, accessibility, and adaptability for diverse research needs in structural biology and therapeutic development.

The revolution in protein structure prediction, led by deep learning tools like AlphaFold2 (AF2) and RoseTTAFold, has provided researchers with an unprecedented number of 3D protein models. However, the true utility of these predictions for downstream applications in research and drug development depends critically on understanding their associated confidence metrics. These metrics are not merely abstract quality scores but convey specific biological information about protein dynamics, flexibility, and inter-domain interactions. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of how AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold implement and interpret these crucial confidence measures, enabling scientists to make informed decisions about their structural models.

At the core of modern structure prediction tools are two primary confidence metrics: the predicted local distance difference test (pLDDT) and the predicted aligned error (PAE). pLDDT provides a per-residue estimate of local structure reliability, while PAE offers a pairwise assessment of relative positional confidence between residues. Proper interpretation of these metrics allows researchers to identify well-defined structural elements, flexible regions, and confidently positioned domains within protein complexes. Benchmarking studies consistently show that AlphaFold2 generally produces more reliable models than RoseTTAFold, as evidenced by objective evaluations in CASP competitions and widespread adoption in the research community [17]. Nevertheless, both systems have distinct strengths and limitations that researchers must consider when interpreting their predictions.

Understanding Key Confidence Metrics

pLDDT (Predicted Local Distance Difference Test)

The pLDDT score is a per-residue local confidence metric that estimates the reliability of the local atomic structure around each amino acid position. This metric is reported on a scale from 0 to 100, with higher values indicating higher prediction confidence. The pLDDT score is calculated by comparing the predicted structure to what would be expected from the "ground truth" structure, though developers note that truly "real" structures don't exist due to protein dynamics [18].

From a biological perspective, pLDDT scores convey important information about residue flexibility and structural disorder. Scores above 90 typically indicate high-confidence models with likely rigid residues, scores between 70 and 90 suggest reasonable confidence, scores between 50 and 70 indicate low confidence and potentially flexible regions, and scores below 50 often correspond to intrinsically disordered regions [18] [19]. Research has demonstrated that pLDDT scores show strong correlation with root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) values derived from molecular dynamics simulations, indicating they capture genuine protein flexibility information [18]. This relationship holds for most structured proteins but may break down for intrinsically disordered proteins or randomized sequences with limited evolutionary information [18].

PAE (Predicted Aligned Error)

The PAE matrix represents a global confidence metric that estimates the expected positional error in Angstroms (Å) between residue pairs when the predicted and actual structures are aligned on a specific residue [19]. Unlike pLDDT, which provides local confidence, PAE assesses the relative positional confidence between different parts of the structure. The PAE is typically visualized as a 2D plot with protein residues along both axes, where each square's color indicates the expected distance error for a residue pair [19].

Low PAE values (darker green in visualizations) indicate high confidence in the relative positioning of two residues, while high PAE values (lighter green) suggest low confidence in their spatial relationship. The PAE plot always features a dark green diagonal representing residues aligned with themselves, which is uninformative and can be ignored [19]. The biologically relevant information resides in the off-diagonal regions, which reveal how confidently different domains or structural elements are positioned relative to each other. This is particularly important for understanding domain packing in multi-domain proteins and assessing the reliability of protein complex interfaces [19].

Relationship Between pLDDT and PAE

While pLDDT and PAE measure different aspects of prediction confidence, they often correlate in biologically meaningful ways. Disordered protein segments predicted with low pLDDT will typically also exhibit large PAE values relative to other protein regions, indicating their positions are not well-defined within the overall structure [19]. However, this relationship is not absolute—pLDDT does not reveal whether protein domains are positioned confidently relative to each other, whereas PAE specifically addresses this question [19]. Therefore, both metrics should be interpreted together for a comprehensive understanding of model quality and limitations.

Table: Interpretation Guidelines for Confidence Metrics

| Metric | Score Range | Interpretation | Biological Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| pLDDT | 90-100 | Very high | High confidence, likely rigid structure |

| 70-90 | Confident | Reliable backbone structure | |

| 50-70 | Low | Flexible regions, use with caution | |

| 0-50 | Very low | Likely disordered, unreliable | |

| PAE | <5 Å | Very high | Confident relative positioning |

| 5-10 Å | Medium | Moderate confidence | |

| 10-15 Å | Low | Uncertain relative positioning | |

| >15 Å | Very low | Essentially random placement |

AlphaFold2 vs. RoseTTAFold: Performance and Metric Comparison

Direct comparisons between AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold reveal important differences in overall performance. Independent evaluations indicate that AlphaFold2 generally creates more reliable models than RoseTTAFold, a conclusion supported by both objective CASP competition results and widespread adoption in the research community [17]. In CASP14, AlphaFold2 demonstrated remarkable accuracy with a median backbone accuracy of 0.96 Å RMSD at 95% residue coverage, vastly outperforming other methods [1]. This performance advantage extends to protein complex prediction, where AlphaFold-multimer (AFm) has shown substantial capability, though with limitations in certain cases [20].

The confidence scores themselves provide evidence of this performance difference. In one case study, the same protein received an average pLDDT of 60 from AlphaFold2 but only a confidence score of 0.39 from RoseTTAFold [17]. While these scores use different scales and cannot be directly compared numerically, the pattern aligns with broader performance trends. However, it's important to note that both scores indicate relatively low confidence in this particular prediction, highlighting that neither tool produces high-quality models for all proteins [17].

Architectural Differences and Metric Interpretation

AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold employ different neural network architectures that influence how they generate both structures and confidence metrics. AlphaFold2 utilizes a sophisticated architecture comprising Evoformer blocks that process evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments (MSAs), followed by a structure module that explicitly reasons about 3D atomic coordinates [1]. This end-to-end approach jointly embeds MSAs and pairwise features while using novel equivariant attention architectures to maintain geometric consistency.

RoseTTAFold implements a three-track architecture that simultaneously processes sequence, distance, and coordinate information, allowing it to integrate information across different scales. While detailed architectural information for RoseTTAFold is limited in the provided search results, one user noted that it relies more heavily on physical energy functions compared to AlphaFold2's deep learning approach [17]. This architectural difference may influence how confidence metrics should be interpreted between the two systems.

Despite these architectural differences, both systems provide confidence metrics that follow similar interpretation principles. The correlation between pLDDT and protein flexibility appears robust across implementations, as demonstrated by studies showing pLDDT scores from AlphaFold2 correlate strongly with RMSF from molecular dynamics simulations [18]. Similarly, PAE plots from both systems should be interpreted using the same fundamental principles regarding relative domain positioning confidence.

Confidence Metric Generation Pipeline: This diagram illustrates the common workflow through which protein sequence information is processed to generate both 3D structures and associated confidence metrics in AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold.

Performance Benchmarking Data

Table: Experimental Benchmarking of Prediction Tools on Heterodimeric Complexes

| Prediction Method | High Quality Models(DockQ >0.8) | Medium Quality Models(DockQ 0.23-0.8) | Incorrect Models(DockQ <0.23) | All Models Incorrect(per target) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold3 | 39.8% | 41.0% | 19.2% | 91.1% |

| ColabFold (with templates) | 35.2% | 34.7% | 30.1% | 79.1% |

| ColabFold (template-free) | 28.9% | 38.8% | 32.3% | 81.9% |

| RoseTTAFold | Limited comparative data available |

Note: Data adapted from a benchmark study of 223 heterodimeric high-resolution protein structures [21]. AlphaFold3 is included for reference, though the primary comparison focuses on AlphaFold2/ColabFold and RoseTTAFold.

Recent benchmarking studies provide quantitative performance comparisons between prediction methods. In an evaluation of 223 heterodimeric complexes, ColabFold (an optimized implementation of AlphaFold2) with templates achieved high-quality predictions in 35.2% of cases, compared to 28.9% for template-free ColabFold [21]. AlphaFold3, included here for reference, achieved 39.8% high-quality predictions. The study also analyzed cases where all five models for a target were incorrect, finding that template-based ColabFold had the lowest percentage of such complete failures (79.1%) compared to template-free ColabFold (81.9%) and AlphaFold3 (91.1%) [21].

For protein-protein interactions, AlphaFold-multimer has demonstrated particular limitations on antibody-antigen targets, achieving only a 20% success rate in one study [20]. This performance gap highlights the importance of domain-specific benchmarking when selecting prediction tools for particular research applications.

Experimental Validation of Confidence Metrics

Correlation with Molecular Dynamics

The biological relevance of confidence metrics, particularly pLDDT, has been experimentally validated through comparisons with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Research has demonstrated that pLDDT scores from AlphaFold2 show strong negative correlation with root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) values derived from MD simulations [18]. This relationship indicates that regions with low pLDDT scores correspond to flexible, dynamic regions in proteins, while high pLDDT scores represent rigid, well-structured elements.

In one comprehensive study, researchers calculated AF2-scores derived from pLDDT values and compared them with RMSF from MD simulations across various protein systems including globular proteins, multi-domain proteins, and protein complexes [18]. The results showed high correlation for most protein types, with Pearson correlation coefficients ranging from -0.84 to -0.97 for well-structured proteins [18]. However, this relationship broke down for intrinsically disordered proteins and randomized sequences, particularly for regions with very low pLDDT scores [18]. This validation confirms that pLDDT scores provide genuine insight into protein dynamics beyond simple prediction confidence.

Similarly, PAE maps from AlphaFold2 show strong correlation with distance variation matrices from molecular dynamics simulations [18]. This relationship demonstrates that PAE captures meaningful information about the relative flexibility between different protein regions, with high PAE values corresponding to pairs of residues that exhibit substantial distance variation during dynamics simulations.

Experimental Protocols for Metric Validation

Researchers can validate confidence metrics using several experimental approaches:

Molecular Dynamics Correlation Protocol:

- Generate protein structure predictions using AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold

- Extract pLDDT scores and PAE matrices from predictions

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations (≥100ns recommended) using packages like GROMACS or AMBER

- Calculate RMSF values for each residue from trajectory data

- Compute correlation coefficients between pLDDT and RMSF values

- Compare PAE matrices with distance variation matrices from MD trajectories

Interface Validation Protocol for Protein Complexes:

- Predict structures of protein complexes using AlphaFold-multimer or RoseTTAFold

- Record interface pLDDT (ipLDDT) and interface PAE (iPAE) values

- Compare with experimental structures (if available) using DockQ scores

- Assess correlation between confidence metrics and interface quality metrics

These protocols allow researchers to establish the reliability of confidence metrics for their specific proteins of interest, which is particularly important when working with novel protein folds or specialized protein families.

Practical Guide for Researchers

Interpretation Guidelines

Effective use of confidence metrics requires careful interpretation within biological context:

Assess Global vs. Local Quality: Check both the average pLDDT and its distribution across the protein. A low average may be misleading if only specific regions (e.g., flexible loops) have low scores while core domains are high confidence [17].

Identify Domain Boundaries with PAE: Use PAE plots to identify autonomous folding units. Low PAE within regions and high PAE between regions suggests independently folding domains with flexible linkers.

Evaluate Complex Interfaces: For protein complexes, focus on interface-specific metrics like ipLDDT and iPAE rather than global scores. These provide more accurate assessment of interaction reliability [21].

Consider Biological Context: Remember that low confidence regions may represent genuine biological flexibility rather than prediction failure. Cross-reference with disorder prediction tools like IUPred2 for validation [18].

Compare Multiple Models: Generate and compare multiple predictions (both within and between tools) to identify consistent structural features versus variable regions.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Tools for Structure Prediction Analysis

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ColabFold | Software | Optimized AF2/RF implementation | Rapid structure prediction with MMSeqs2 integration |

| ChimeraX | Software | Molecular visualization | Structure analysis and confidence metric visualization |

| PICKLUSTER | Software Plugin | Interface quality assessment | Protein complex validation and scoring |

| VoroIF-GNN | Algorithm | Interface-specific quality assessment | Complementary validation of interface predictions |

| pDockQ2 | Metric | Protein complex quality estimation | Evaluation of multimeric assemblies |

| Foldseck | Database | Rapid structural similarity search | Identifying structural homologs for validation |

Limitations and Caveats

While confidence metrics provide invaluable guidance, researchers should be aware of several important limitations:

Training Bias: Both AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold may show biased confidence toward structural motifs well-represented in training data, potentially overestimating confidence for novel folds [22].

Conformational Flexibility: Static predictions cannot capture multiple biological conformations. Low confidence might indicate conformational heterogeneity rather than poor prediction [20].

Complex Limitations: Protein complex prediction, especially for antibody-antigen pairs, remains challenging with higher failure rates despite reasonable confidence scores [20].

Physical Realism: Recent studies question whether co-folding models truly learn physical principles or primarily recognize patterns from training data, particularly for protein-ligand interactions [22].

Context Dependence: Confidence metrics are most reliable for monomeric globular proteins with deep multiple sequence alignments. Performance varies for complexes, disordered proteins, and membrane proteins [18].

Confidence metrics pLDDT and PAE provide essential information for interpreting protein structure predictions from AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold. While both systems produce useful models and confidence estimates, AlphaFold2 generally demonstrates higher accuracy across diverse protein types. The biological interpretation of these metrics—linking pLDDT to residue flexibility and PAE to domain packing confidence—has been validated through molecular dynamics simulations and experimental structures.

For researchers applying these tools in drug development and basic research, proper interpretation requires integrating both local (pLDDT) and global (PAE) confidence metrics while considering biological context. Interface-specific metrics are particularly important for complex evaluation. As the field advances, combining deep learning predictions with physics-based validation approaches will continue to enhance reliability and biological relevance of computational structural models.

Biological Interpretation of Confidence Metrics: This diagram illustrates how to translate raw confidence scores into biologically meaningful interpretations of protein structural properties.

Training Data and Evolutionary Principles Underpinning Each Algorithm

Core Architectural Principles and Training Data

The accuracy of AI-driven protein structure prediction tools is fundamentally determined by their underlying architectural principles and the training data they utilize. AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold, while sharing a common goal, employ distinct approaches to learning from evolutionary information.

AlphaFold2 relies on an Evoformer module—a deep learning architecture that processes patterns found in multiple sequence alignments (MSAs). The model was trained on protein sequences and structures from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The Evoformer uses row-wise, column-wise, and triangle self-attention to iteratively infer relationships between residues, deriving information about residue distances and evolutionary couplings from the MSAs. This iterative refinement allows the network to generate highly accurate distance maps and torsion angle distributions, which are subsequently optimized via gradient descent to produce a final 3D structure with atomic-level accuracy [5]. A key to its performance was the massive scale of its training data, which was later expanded by 30% in the AlphaFold2.3 update and includes millions of protein structures [5].

RoseTTAFold implements a unique three-track neural network that simultaneously reasons about protein sequence (1D), distance relationships between amino acids (2D), and 3D atomic coordinates. This design allows information to flow seamlessly between different levels of protein representation. During training, it was also trained on PDB structures and uses MSA information. However, its three-track system enables it to integrate these different data types more directly, allowing the network to collectively reason about relationships within and between sequences, distances, and coordinates [5]. This architecture was inspired by, and represents an alternative approach to, the deep learning principles demonstrated by AlphaFold2.

The table below summarizes the core differences in their approaches to handling evolutionary information.

Table 1: Core Architectural and Training Data Principles

| Feature | AlphaFold2 | RoseTTAFold |

|---|---|---|

| Core Architectural Module | Evoformer [5] | Three-track network (1D, 2D, 3D) [5] |

| Primary Evolutionary Input | Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) [5] | Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) [5] |

| Training Data Source | Protein Data Bank (PDB) structures [5] | Protein Data Bank (PDB) structures [5] |

| Key Innovation | Iterative refinement of MSA and pair representations via attention mechanisms [5] | Simultaneous, integrated processing of sequence, distance, and coordinate information [5] |

Performance Evaluation and Experimental Benchmarking

Rigorous independent benchmarking on standardized datasets is crucial for objectively comparing the predictive accuracy of AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold. Performance is typically measured using metrics like Template Modeling Score (TM-score) and Global Distance Test (GDT_TS), which assess the topological and atomic-level similarity between predicted and experimental structures.

Evaluations on the CASP14 (Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction) dataset show that both models achieve state-of-the-art accuracy, with AlphaFold2 often holding a slight edge [5]. However, performance is not uniform across all protein types. For instance, a systematic analysis of nuclear receptor structures revealed that while AlphaFold2 produces models with high stereochemical quality, it systematically underestimates ligand-binding pocket volumes by an average of 8.4% and struggles to capture the full spectrum of biologically relevant conformational states [23]. This indicates a limitation in predicting flexible regions and functional dynamics.

Furthermore, in modeling protein complexes, AlphaFold2 (via its AlphaFold-Multimer variant) has demonstrated a remarkable capability to predict many transient heterodimeric interactions, significantly outperforming traditional protein-docking algorithms. A benchmark of 152 heterodimeric complexes showed AlphaFold-Multimer produced near-native models as top predictions for 43% of cases, compared to just 9% for a leading docking method [24]. Nevertheless, its performance on antibody-antigen complexes was notably poor, with a subsequent study confirming a low success rate of only 11% for this critical class of interactions [24] [21].

The table below summarizes quantitative performance data from key experimental benchmarks.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Benchmarking

| Benchmark / Metric | AlphaFold2 / Multimer | RoseTTAFold |

|---|---|---|

| CASP14 Performance | Atomic-level accuracy, often competitive with experimental structures [5] | Similar high accuracy to AlphaFold2 [5] |

| Ligand-Binding Pocket Volume | Systematically underestimated by 8.4% on average [23] | Information not specified in search results |

| Heterodimeric Complex Prediction (Success Rate) | 43% near-native as top model [24] | Information not specified in search results |

| Antibody-Antigen Complex Prediction (Success Rate) | ~11% success rate [24] [21] | Information not specified in search results |

| MSA Dependency | High dependency; performance can drop with few homologs [25] | High dependency, though LightRoseTTA variant addresses this [25] |

Methodologies for Experimental Validation

To ensure the reliability of predictions, researchers employ standardized experimental protocols for benchmarking. The methodology typically involves blind prediction tests and systematic comparisons against gold-standard experimental data.

A core resource for evaluation is the Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiment, a community-wide blind test where predictors are given amino acid sequences of proteins with unsolved structures and their predictions are later compared to newly determined experimental structures [5]. The Critical Assessment of Predicted Interactions (CAPRI) provides a similar framework for evaluating protein complexes [24] [21].

A typical benchmarking workflow involves:

- Input Sequence Preparation: Using the canonical amino acid sequence of the target protein.

- Structure Prediction: Running the sequence through the AI models (e.g., AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold) to generate 3D coordinate files.

- Experimental Structure Alignment: Comparing the predicted model to the high-resolution experimental structure (e.g., from X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM) using structural alignment algorithms.

- Quantitative Scoring: Calculating metrics like TM-score, GDT_TS, and Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) to quantify global fold accuracy, and interface-RMSD (I-RMSD) for complexes [24] [21].

- Qualitative Analysis: Inspecting specific functional sites, such as ligand-binding pockets and protein-protein interfaces, for structural accuracy and conformational diversity [23].

For protein complex modeling, the DockQ score is a widely used metric that combines information on interface contacts, ligand RMSD, and interface RMSD into a single quality measure, with classifications ranging from 'incorrect' to 'high quality' [21]. The predicted Local Distance Difference Test (pLDDT) and predicted Template Modeling (pTM) scores are internally produced by the models to estimate their own confidence, with interface-specific versions (ipLDDT, ipTM) being particularly valuable for assessing complex predictions [21].

Advanced Derivatives and Ensemble Approaches

The core architectures of AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold have spurred the development of advanced derivatives that address specific limitations, such as computational efficiency and MSA dependency.

LightRoseTTA is a lightweight, graph neural network-based variant of RoseTTAFold that achieves competitive accuracy with a fraction of the computational cost. It contains only 1.4 million parameters (compared to RoseTTAFold's 130 million) and can be trained in about one week on a single GPU, demonstrating that high performance is possible with a more efficient architecture [25]. Crucially, LightRoseTTA shows reduced dependency on MSAs, achieving superior performance on "orphan" proteins with few homologous sequences [25].

OpenFold is a fully trainable, open-source implementation of AlphaFold2, created to fill the gap left by its proprietary training code. It matches AlphaFold2's accuracy while providing the scientific community with the ability to deeply understand, modify, and extend the model for new applications, such as predicting protein-ligand complexes [5].

Beyond single-model predictions, ensemble methods like FiveFold represent a paradigm shift. This approach combines predictions from five different algorithms—AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, OmegaFold, ESMFold, and EMBER3D—to generate a ensemble of plausible conformations. It uses a Protein Folding Shape Code (PFSC) to represent secondary structure elements and a Protein Folding Variation Matrix (PFVM) to capture conformational diversity. This method is particularly valuable for modeling intrinsically disordered proteins and the flexible regions that are often missed by single-state predictions from any one algorithm [26].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a comprehensive protein structure prediction and validation experiment, integrating both single-model and ensemble approaches.

Table 3: Key Resources for Protein Structure Prediction Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database [5] | Database | Provides instant access to over 200 million pre-computed AlphaFold2 predictions for known catalogued proteins, enabling rapid hypothesis generation. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [5] | Database | The single worldwide repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins, used as the gold standard for validation and for training AI models. |

| ColabFold [24] [21] | Software Suite | A fast and user-friendly implementation of AlphaFold2 and other tools that runs via Google Colab notebooks, greatly increasing accessibility. |

| OpenFold [5] | Software | A trainable, open-source implementation of AlphaFold2, enabling custom model training and exploration of new architectural variants. |

| FiveFold Framework [26] | Methodology | An ensemble approach that combines five different prediction algorithms to model conformational diversity, especially useful for flexible proteins. |

| DockQ & pDockQ [21] | Scoring Metric | Standardized metrics for quantitatively assessing the quality of predicted protein-protein interfaces against experimental structures. |

| CASP/CAPRI Datasets [5] [24] | Benchmarking Data | Curated sets of protein sequences and structures used for blind testing and fair comparison of prediction algorithm performance. |

Performance Benchmarking: Accuracy Across Protein Classes and Complexes

The 14th Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP14) marked a historic turning point for computational biology, representing the first time a method achieved accuracy competitive with experimental structure determination for single-chain proteins. This breakthrough, primarily driven by DeepMind's AlphaFold2, has fundamentally reshaped the field of structural bioinformatics and opened new avenues for biological research and drug development. The CASP14 competition served as a rigorous blind test, where predictors were challenged to model protein structures that had been experimentally determined but not yet publicly released. The results demonstrated that computational methods could now reliably generate accurate 3D models of globular proteins from their amino acid sequences, a problem that had remained unsolved for over 50 years [1] [27].

This comparison guide provides an objective analysis of the performance between the two leading methods showcased at CASP14: AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold. We examine their architectural foundations, quantitative accuracy metrics on standardized benchmarks, and practical implications for research applications. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the capabilities and limitations of these tools is essential for their effective implementation in structural biology pipelines and therapeutic discovery programs.

CASP14 Assessment Framework and Key Metrics

Experimental Protocol and Evaluation Methodology

The CASP14 assessment employed rigorous, standardized protocols to ensure fair comparison between methods. The experiment was conducted as a blind test where predictors generated models for protein sequences whose experimental structures were known only to assessors. A total of 72 protein sequences were used in the assessment, with predictors submitting up to five models per target [28].

The primary metrics for evaluating global structure accuracy were:

- GDTTS (Global Distance Test Total Score): Measures the percentage of Cα atoms in a model within specified distance thresholds (1, 2, 4, and 8 Å) from their correct positions after optimal superposition, with scores ranging from 0-100. A higher GDTTS indicates better overall fold capture [28] [29].

- LDDT (Local Distance Difference Test): Evaluates local structural accuracy by comparing distances between atoms in the model versus the reference structure, without requiring global superposition. This metric is particularly valuable for assessing regions like loop structures [28] [1].

For local accuracy assessment, methods were evaluated using:

- ASE (Average S-score Error): Quantifies the average error in residue-wise accuracy predictions [28].

- AUC (Area Under the Curve): Measures the ability to distinguish accurately from inaccurately modeled residues [28].

- ULR (Unreliable Local Regions): Assesses the detection of stretches of sequentially inaccurate residues [28].

The assessment categorized targets by difficulty, with Free Modeling (FM) targets representing the most challenging cases with no structural templates available [30].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key Experimental Resources and Computational Tools

| Resource/Tool | Function in CASP14 Assessment | Relevance to Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| CASP14 Dataset | 72 protein targets with undisclosed experimental structures | Provides standardized benchmark for method validation |

| GDT_TS | Primary metric for global fold accuracy | Enables quantitative comparison of model quality |

| pLDDT | Per-residue confidence estimate output by AlphaFold2 | Guides interpretation of model reliability for downstream applications |

| DAVIS-EMAconsensus | Baseline method for multi-model accuracy estimation | Serves as reference for evaluating new quality assessment methods |

| TM-score | Metric for structural similarity, used for template clustering | Useful for comparing structural models and detecting conformational diversity |

Architectural Comparison: AlphaFold2 vs. RoseTTAFold

AlphaFold2: End-to-End Deep Learning

AlphaFold2 introduced a completely novel architecture that represented a paradigm shift from earlier protein structure prediction methods. The system employs an end-to-end deep neural network that directly processes multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and template information to produce atomic-level coordinates [1] [29]. Its key innovation lies in the Evoformer block - a novel neural network module that jointly embeds MSA and pairwise representation through attention mechanisms, enabling the model to reason about evolutionary constraints and physical interactions simultaneously [1].

The structure module of AlphaFold2 uses a rotationally and translationally equivariant architecture to directly generate atomic coordinates, employing an iterative "recycling" process to refine predictions. The network is trained end-to-end, with all parameters optimized through backpropagation from the final atomic coordinates back to the input sequence [1] [29]. During CASP14, AlphaFold2 generated up to five predictions per target using different model parameters, with final ranking based on predicted LDDT (pLDDT) scores [29].

RoseTTAFold: Three-Track Neural Network

RoseTTAFold, developed by the Baker laboratory at the University of Washington, implements a three-track neural network that simultaneously processes information at three different levels: one-dimensional sequence patterns, two-dimensional distance maps, and three-dimensional atomic coordinates [10] [31]. In this architecture, information flows back and forth between the different representations, allowing the network to collectively reason about relationships within and between sequences, distances, and coordinates.

Unlike AlphaFold2's fully end-to-end approach, RoseTTAFold was implemented in two versions: one that uses the network to predict distance and orientation distributions followed by pyRosetta for all-atom model generation, and an end-to-end version that directly outputs backbone coordinates [10]. The three-track design enables RoseTTAFold to effectively leverage information at different scales of structural organization, though hardware limitations initially restricted the size of models that could be trained [10].

Diagram 1: Architectural comparison of AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold, highlighting fundamental differences in information processing. AlphaFold2 uses sequential processing with recycling, while RoseTTAFold employs simultaneous three-track reasoning. (Short Title: Architecture Comparison)

Quantitative Performance Analysis at CASP14

Global Accuracy Metrics

The CASP14 results demonstrated unprecedented accuracy for both top-performing methods, with AlphaFold2 achieving a landmark median domain GDT_TS of 92.4 across all targets [29] [30]. This performance level marked the first time computational methods regularly produced structures competitive with experimental determination in the majority of cases. RoseTTAFold, while not matching AlphaFold2's peak performance, substantially outperformed all other non-DeepMind methods and demonstrated capabilities far beyond previous state-of-the-art systems [10].

Table 2: CASP14 Performance Comparison for Single-Chain Proteins

| Metric | AlphaFold2 | RoseTTAFold | Next Best Method | Performance Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median GDT_TS | 92.4 [29] | ~80-85 (estimated) [10] | ~70-75 (estimated) [30] | ~15-20 points [30] |

| Summed Z-score | 244.0 [29] | Not available (public server post-CASP) | 90.8 (next best group) [29] | 2.7x higher than next best |

| Targets with GDT_TS > 70 | 87/92 domains [29] | Not explicitly reported | Significantly fewer | Dominant performance |

| Targets with GDT_TS > 90 | 58 domains [29] | Not explicitly reported | Very few | Experimental accuracy achieved |

| Backbone Accuracy (Cα RMSD₉₅) | 0.96 Å median [1] | Not explicitly reported | 2.8 Å median [1] | ~3x more accurate |

| All-Atom Accuracy (RMSD₉₅) | 1.5 Å [1] | Not explicitly reported | 3.5 Å [1] | ~2.3x more accurate |

Local Accuracy and Confidence Estimation

Both AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold generate per-residue confidence estimates that reliably predict local accuracy. AlphaFold2's pLDDT scores show strong correlation with actual LDDT values calculated against experimental structures [1]. This capability is crucial for practical applications, as it allows researchers to identify which regions of a predicted model can be trusted for downstream analysis.

In CASP14 assessment of local accuracy, methods were evaluated on their ability to identify unreliable local regions (ULRs) - stretches of three or more sequential residues deviating by more than 3.8Å from corresponding target residues. The best-performing methods used advanced deep learning approaches to accurately flag these problematic regions [28].

Practical Implementation and Research Applications

Computational Requirements and Accessibility

A significant practical difference between the two systems lies in their computational requirements and accessibility. During CASP14, DeepMind employed substantial computational resources for each prediction, reportedly using several GPUs for days to generate models for some targets [10]. In contrast, RoseTTAFold was designed to be more computationally efficient, capable of generating models in as little as 10 minutes on a single gaming computer for typical proteins [31].

Following CASP14, both systems have been made accessible to the research community through different models. AlphaFold2 is available via a public database of precomputed structures for multiple organisms and as open-source code for local installation [32]. RoseTTAFold is accessible through a public server where researchers can submit sequences, with the code also available for local deployment [31]. This accessibility has enabled widespread adoption, with RoseTTAFold being downloaded by over 140 independent research teams shortly after its release [31].

Performance on Challenging Targets

Both systems were tested on particularly difficult CASP14 targets that highlighted their respective strengths. For target T1024, an active transporter with multiple conformational states, AlphaFold2 initially produced high-quality models but lacked diversity across its five predictions [29]. This prompted manual intervention where template clustering was used to generate structurally diverse models representing different conformations [29].

For the SARS-CoV-2 ORF8 protein (T1064), AlphaFold2 produced remarkably accurate predictions that correctly captured even flexible loop regions that had challenged other methods [27]. In some cases, AlphaFold2's predictions were so accurate that they helped resolve ambiguities in experimental structure determination, with one group correcting their cis-proline assignment based on the model, and another solving a crystal structure in hours that had previously taken years using AlphaFold2's prediction for molecular replacement [27].

Diagram 2: CASP14 evaluation workflow showing how targets were processed and assessed. Both methods used MSAs and templates, generating multiple models for blind assessment. (Short Title: CASP14 Evaluation Workflow)

Limitations and Future Directions

Current Methodological Constraints

Despite their remarkable performance on single-chain globular proteins, both AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold face limitations in specific domains. The accuracy of both methods remains dependent on the depth and quality of multiple sequence alignments, though this dependence is reduced compared to earlier methods [10] [32]. For proteins with few homologous sequences, accuracy may be compromised, though still often superior to traditional approaches.

Neither system natively predicts multi-chain protein complexes during CASP14, focusing exclusively on single-chain structures [28] [33]. This represents a significant limitation since many proteins function as complexes in biological systems. Subsequent to CASP14, both teams have expanded their methods to address protein-protein interactions, but accurate quaternary structure prediction remains challenging [33].

Both methods primarily predict static structures and struggle with conformational flexibility and dynamics, as evidenced by the T1024 case where manual intervention was needed to sample alternate conformations [29]. Intrinsically disordered regions also present challenges, as these lack stable structure and may be poorly modeled or assigned low confidence scores [29].

Emerging Research Directions

The success of AlphaFold2 and RoseTTAFold at CASP14 has catalyzed several new research directions. There is growing interest in developing faster, single-sequence methods that reduce or eliminate the need for MSAs, such as ESMFold and OmegaFold, though these currently trade off some accuracy for speed [32]. Integrating structural predictions with functional annotation represents another active area, leveraging the sudden availability of accurate models for previously uncharacterized proteins.

For drug discovery professionals, the availability of high-accuracy structures enables more reliable structure-based drug design, though caution remains necessary when using models for regions with low confidence scores [27] [32]. The demonstrated ability of these models to solve challenging molecular replacement cases in crystallography also opens new possibilities for experimental structural biology [27].

The CASP14 assessment marked a watershed moment for protein structure prediction, with AlphaFold2 establishing a new benchmark for accuracy that dramatically surpassed all previous methods. RoseTTAFold, while not matching AlphaFold2's peak performance, demonstrated that academic laboratories could achieve competitive results and provided a more accessible alternative for the research community. Both methods leverage deep learning and evolutionary information but differ fundamentally in their architectural approaches and computational requirements.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these tools have transformed the landscape of structural biology, making high-accuracy models accessible for virtually any protein sequence. While challenges remain in modeling complexes, conformational dynamics, and orphan proteins with few homologs, the core problem of single-chain protein structure prediction for globular proteins has been effectively solved. The legacy of CASP14 extends beyond the competition itself, having launched a new era where computational models serve as foundational tools for biological discovery and therapeutic development.

The accurate prediction of protein-protein interaction (PPI) structures is crucial for understanding cellular mechanisms and advancing therapeutic development [14]. While AlphaFold2 (AF2) revolutionized single-chain protein structure prediction, modeling multi-chain complexes presents a more formidable challenge, requiring accurate capture of inter-chain interactions [14]. Two leading deep-learning frameworks have been developed to address this: AlphaFold-Multimer (AFm), a specialized extension of AF2 for complexes, and RoseTTAFold, a three-track architecture designed for joint reasoning about sequence, distance, and structure. This guide objectively compares their performance, experimental methodologies, and optimal use cases to inform researcher selection.

AlphaFold-Multimer Architecture

AlphaFold-Multimer builds upon the core AF2 architecture, which uses an Evoformer module to process multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) and a Structure Module to generate atomic coordinates [24]. AFm was specifically trained on protein complex data to model quaternary structures [24] [20]. Its training incorporated specific stereochemical violation penalties and losses designed to enforce plausible interface geometries [6]. AFm takes the sequences of multiple chains as input and generates a complete complex structure, outputting confidence metrics like predicted TM-score (pTM) and interface predicted aligned error (pAE) to assess model quality [24] [20].

RoseTTAFold Architecture

RoseTTAFold employs a distinctive three-track neural network that simultaneously processes information at the 1D sequence level, 2D residue-pair distance level, and 3D coordinate level [10]. Information flows iteratively between these tracks, allowing the network to collectively reason about relationships within and between sequences, distances, and coordinates. This architecture is end-to-end trainable and can be adapted for various modeling tasks, including protein-protein complexes and protein-nucleic acid interactions (as seen in RoseTTAFoldNA) [34] [10]. For complex prediction, it can generate models from sequence alone or utilize additional information from paired MSAs.

Architectural paradigms of AFm and RoseTTAFold. AFm uses a sequential pipeline, while RoseTTAFold features iterative information flow between its three tracks.

Performance Benchmarking and Comparative Analysis

Independent benchmarking reveals distinct performance profiles for each system. The following table summarizes key quantitative comparisons from recent studies and benchmarks.

Table 1: Performance comparison on standard protein complex benchmarks

| Benchmark / Metric | AlphaFold-Multimer | RoseTTAFold | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CASP15 Multimer Targets (TM-score) | Baseline | +11.6% improvement (DeepSCFold) [14] | DeepSCFold uses RoseTTAFold concepts |

| Antibody-Antigen Success Rate (SAbDab) | 20% [20] | +24.7% improvement (DeepSCFold) [14] | Challenging due to limited co-evolution |