Benchmarking Genome Assemblers: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide to benchmarking genome assemblers, a critical step in genomics that directly impacts downstream applications in drug development and clinical research.

Benchmarking Genome Assemblers: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to benchmarking genome assemblers, a critical step in genomics that directly impacts downstream applications in drug development and clinical research. We explore the foundational principles of assembly evaluation, detail methodological approaches for long-read and hybrid sequencing data, and present strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. By synthesizing findings from recent large-scale benchmarks, we offer a validated framework for selecting assembly tools and pipelines, empowering scientists to generate high-quality genomic resources essential for uncovering disease mechanisms and advancing personalized medicine.

The Genome Assembly Landscape: Why Benchmarking is Crucial for Accurate Genomics

The reliability of genome assemblies is a foundational element in modern genomic research, acting as the primary scaffold upon which all subsequent biological interpretations are built. The quality of a genome assembly directly controls the fidelity of functional annotation and the accuracy of comparative genomics analyses, which in turn influences downstream applications in drug development and disease mechanism studies. Research has demonstrated that assemblies with different qualities can lead to markedly different biological conclusions, making rigorous quality assessment a non-negotiable step in genomic workflows [1] [2].

The principle of "Garbage In, Garbage Out" is particularly pertinent to genome assembly. Errors in the assembly—whether at the base level, such as single-nucleotide inaccuracies, or the structural level, including misjointed contigs or missing regions—cascade through all downstream analyses. These errors can manifest as missing exons, fragmented genes, incorrectly inferred evolutionary relationships, or entirely missed genetic variants of clinical importance [3]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this translates to potential misinterpretations of a gene's functional role, an organism's pathogenic mechanism, or the identification of flawed drug targets. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of how to assess assembly quality and its subsequent impact is crucial for ensuring the integrity of genomic research.

Assessing Genome Assembly Quality: The 3C Principles and Benchmarking Tools

The quality of a genome assembly is quantitatively assessed based on three core principles, often called the "3Cs": Contiguity, Completeness, and Correctness [3].

- Contiguity measures how much of the genome is reconstructed into long, uninterrupted stretches. Key metrics include the N50/L50, where a higher N50 value indicates a more contiguous assembly, and the total number of contigs or scaffolds, where a lower number is preferable.

- Completeness evaluates what proportion of the actual genome is present in the assembly. This is assessed by looking for a core set of universal single-copy orthologs using tools like BUSCO, where a score above 95% is considered good, or by analyzing k-mer spectra from raw reads to see what fraction is represented in the assembly [4] [3].

- Correctness gauges the accuracy of each base pair and the overall structure. Base-level correctness can be checked by mapping high-quality short reads to the assembly, while structural correctness often requires comparison to a known reference or the use of technologies like Hi-C or Bionano [3].

To streamline this multi-faceted evaluation, several integrated tools have been developed. QUAST provides a comprehensive report on assembly metrics with or without a reference genome. GenomeQC is an interactive web framework that integrates a suite of quantitative measures, including BUSCO for gene space completeness and the LTR Assembly Index (LAI) for assessing the completeness of repetitive regions, which is particularly valuable for plant genomes [4]. The Genome Assembly Evaluation Pipeline (GAEP) is another comprehensive tool that utilizes NGS data, long-read data, and transcriptome data to evaluate assemblies for continuity, accuracy, completeness, and redundancy [3].

Table 1: Key Tools for Genome Assembly Quality Assessment

| Tool | Primary Function | Key Metrics | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| QUAST | Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies | N50, misassemblies, mismatches per 100 kbp | Works with/without reference genome; user-friendly reports [3]. |

| GenomeQC | Integrated Quality Assessment | NG(X) plots, BUSCO, LAI, contamination check | Web framework; assesses both assembly and gene annotation [4]. |

| BUSCO | Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs | Complete, fragmented, missing orthologs (%) | Measures gene space completeness against conserved gene sets [4] [3]. |

| GAEP | Genome Assembly Evaluation Pipeline | Basic stats, BUSCO, k-mer analysis | Uses multiple data sources (NGS, long-read, transcriptome) for evaluation [3]. |

| Merqury | K-mer-based Evaluation | QV, k-mer completeness | Uses k-mer spectra to assess base-level accuracy and completeness [5]. |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Assemblers

To objectively compare the performance of different genome assemblers, a standardized benchmarking approach is essential. The following protocol, synthesized from recent large-scale studies, outlines a robust methodology.

Experimental Design and Data Preparation

The foundation of a reliable benchmark is the use of well-characterized reference samples and a variety of sequencing data. The Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) Consortium provides widely adopted reference materials, such as the human sample HG002 [5]. For a comprehensive benchmark, data from multiple sequencing technologies should be incorporated:

- Long-read data from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) or PacBio to resolve repetitive regions and improve contiguity.

- Short-read data from Illumina for high base-level accuracy and polishing.

- The data should be subsampled to various coverages (e.g., 30X, 50X) and read lengths to evaluate performance under different data constraints [1].

Assembly and Polishing Workflow

A typical benchmarking workflow involves multiple stages:

- Assembly: The selected assemblers are run on the designated sequencing datasets. As highlighted in a 2025 benchmark, both long-read-only assemblers (e.g., Flye, Canu) and hybrid assemblers (e.g., MaSuRCA) should be tested [5] [6].

- Polishing: The initial draft assemblies are refined through iterative polishing. The benchmark found that the best results were often achieved with a combination of long-read-based polishing (e.g., Racon) followed by short-read-based polishing (e.g., Pilon) [5].

- Scaffolding (optional): For chromosome-level assemblies, Hi-C data can be used with scaffolding tools like SALSA2 or ALLHIC [1].

Quality Assessment and Analysis

The final, polished assemblies are evaluated using the metrics and tools described in Section 2. A comprehensive analysis includes:

- QUAST for contiguity and misassembly statistics.

- BUSCO for gene completeness.

- Merqury for k-mer-based quality valuation (QV) and completeness [5].

- LAI for assessing repetitive region assembly in complex genomes [4]. The results are then compiled for cross-assembler comparison.

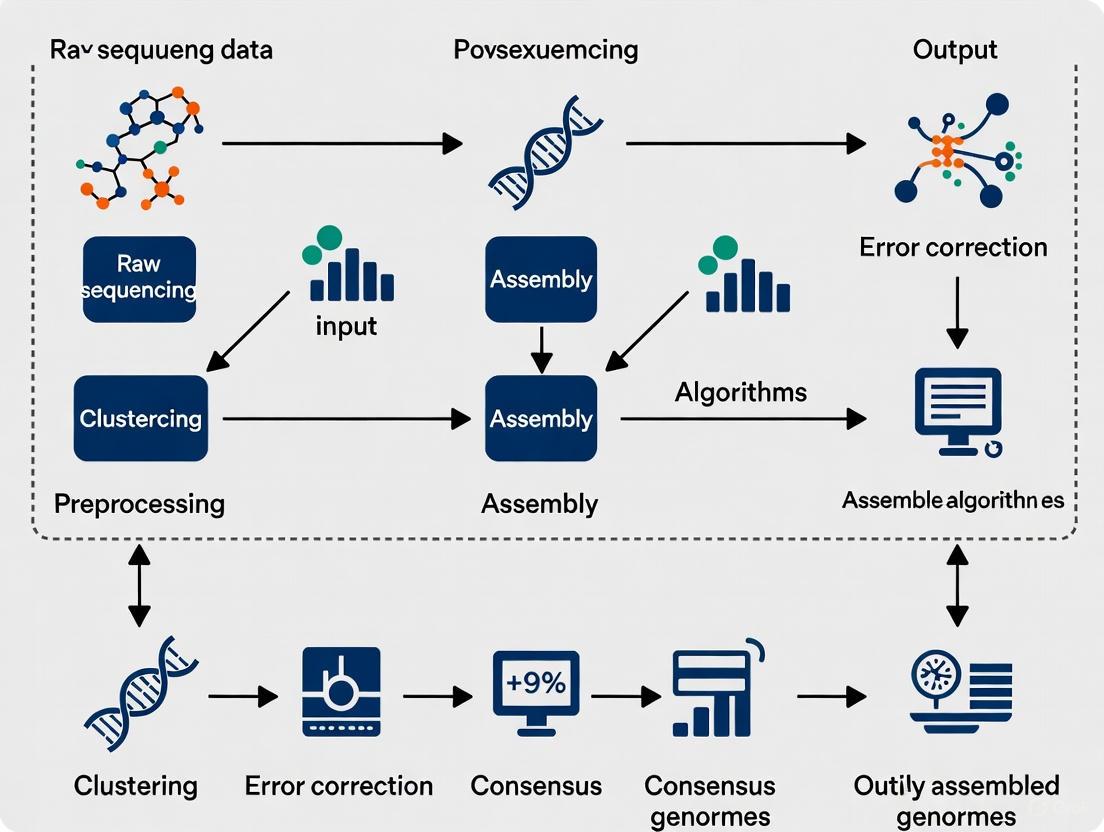

Diagram 1: Genome Assembler Benchmarking Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key experimental stages for objectively comparing genome assemblers, from data preparation to final analysis.

Quantitative Comparison of Genome Assemblers

Recent benchmarking studies provide critical quantitative data on the performance of modern assemblers. A 2025 study evaluating 11 pipelines for hybrid de novo assembly of human genomes using ONT and Illumina data found that Flye outperformed other assemblers, especially when ONT reads were pre-corrected with tools like Ratatosk [5]. The study further demonstrated that polishing is a non-negotiable step, with the best results coming from two rounds of Racon followed by Pilon, which significantly improved both assembly accuracy and continuity [5].

Table 2: Benchmarking Results of Assembly and Polishing Pipelines (Adapted from [5])

| Assembly Strategy | Best-Performing Tool | Key Quality Metrics (Post-Polishing) | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-Read (ONT) Assembly | Flye | High continuity (N50), superior BUSCO completeness | Moderate |

| Hybrid Assembly | MaSuRCA | Good balance of continuity and base accuracy | High |

| Pre-Assembly Correction | Ratatosk + Flye | Improved assembly continuity and accuracy | Very High |

| Polishing Strategy | Racon (2x) + Pilon (1x) | Optimal baseline and structural variant accuracy | Moderate |

The impact of input data quality and assembly strategy was further explored in a 2021 study on a non-model plant genome. It revealed that data subsampled for longer read lengths, even at lower coverage, produced more contiguous and complete assemblies than data with shorter reads but higher coverage [1]. This finding underscores the critical importance of read length for resolving complex genomic regions. The study also highlighted that the success of downstream scaffolding with Hi-C data is heavily dependent on the underlying contig assembly being accurate; problems in the initial assembly cannot be resolved by Hi-C and may even be exacerbated [1].

Impact of Assembly Quality on Functional Annotation

Functional annotation is the process of attaching biological information—such as gene predictions, functional domains, and Gene Ontology (GO) terms—to a genome sequence. The quality of the underlying assembly is the primary determinant of annotation accuracy and completeness. A fragmented or erroneous assembly directly leads to fragmented or missing gene models, mis-identified exon-intron boundaries, and ultimately, an incomplete or misleading functional catalog of the organism [6] [3].

A case study on the pathogenic protozoan Balamuthia mandrillaris vividly illustrates this dependency. Researchers performed a hybrid assembly using both Illumina short reads and ONT long reads, resulting in a genome with superior assembly metrics compared to previously available drafts. This high-quality assembly enabled a comprehensive functional annotation, which successfully identified 11 out of 15 genes that had previously been described as potential therapeutic targets. This was only possible because the improved assembly provided a more complete and accurate genomic context [6]. In contrast, an assembly littered with gaps and misassemblies will cause gene prediction algorithms to fail, leaving researchers with an incomplete picture of the organism's biology and potentially missing critical virulence factors or drug targets.

Impact of Assembly Quality on Comparative Genomics

Comparative genomics relies on the accurate comparison of genomic features across different species or strains to infer evolutionary relationships, identify conserved regions, and discover genes underlying specific traits. The foundation of these analyses is a set of high-quality, colinear genome sequences. Errors in individual assemblies propagate through comparative analyses, leading to incorrect inferences of gene gain and loss, flawed phylogenetic trees, and misidentification of genomic rearrangements [7].

For example, a core analysis in comparative genomics is the definition of the pangenome, which comprises the core genome (genes shared by all strains) and the accessory genome (genes present in some strains). If one assembly in a multi-species comparison is highly fragmented, genes may be split across multiple contigs or missed entirely. This would artificially inflate the number of "unique" genes in the accessory genome for that species while simultaneously shrinking the core genome, leading to a distorted view of evolutionary relationships and functional conservation [8] [7]. The PATRIC database, as a bacterial bioinformatics resource center, exemplifies the need for "virtual integration" of high-quality, uniformly annotated genomes to enable reliable comparative studies [8]. Consistent, high-quality assemblies are therefore prerequisite for meaningful comparative genomics that can accurately trace the evolution of pathogenicity or antibiotic resistance across bacterial lineages.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genome Assembly and Annotation

| Resource / Tool | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| GIAB Reference Materials | Biological Standard | Provides benchmark genomes (e.g., HG002) for validating assembly and variant calling accuracy [5]. |

| PATRIC | Bioinformatics Database | An all-bacterial bioinformatics resource center for comparative genomic analysis with integrated tools [8]. |

| Flye | Software | A long-read assembler that has demonstrated top performance in benchmarks for continuity and completeness [5]. |

| Racon & Pilon | Software | A combination of polishers used to correct base-level errors in a draft assembly using long and short reads, respectively [5]. |

| BUSCO Dataset | Software/Database | A set of universal single-copy orthologs used to quantitatively assess the completeness of a genome assembly [4] [3]. |

| Funannotate | Software | A pipeline for functional annotation of a genome, integrating gene prediction, functional assignment, and non-coding RNA identification [6]. |

| Restauro-G | Software | A rapid, automated genome re-annotation system for bacterial genomes, ensuring consistent annotation across datasets [9]. |

The body of evidence from systematic benchmarks and case studies leads to an unequivocal conclusion: the quality of a genome assembly is not a mere technical detail but a fundamental variable that dictates the success of all downstream genomic analyses. Investments in superior sequencing data (particularly long reads), robust assembly algorithms like Flye, and rigorous polishing protocols yield dividends in the form of more complete and accurate functional annotations and more reliable comparative genomic insights. For researchers and drug developers, prioritizing genome quality is a critical step toward ensuring that biological discoveries and therapeutic target identification are built upon a solid and trustworthy foundation.

The quality of a genome assembly is fundamental, as it directly impacts all subsequent biological interpretations and analyses [10]. The assessment of this quality is universally structured around three core dimensions: contiguity, completeness, and correctness—collectively known as the "3 Cs" [10] [3] [11]. Relying on a single metric, particularly those related only to contiguity like the popular N50, is a common but misleading practice. High contiguity does not guarantee an accurate assembly; in fact, the most contiguous assembly may also be the most incorrect if misjoins have artificially inflated contig sizes [12] [11]. A holistic evaluation is therefore indispensable. This guide provides a structured overview of the core metrics and methodologies for evaluating genome assemblies, framing them within the context of benchmarking genome assemblers. It is designed to help researchers and developers objectively compare assembler performance by synthesizing current evaluation protocols and experimental data.

Defining the Core Metrics: The "3 Cs" Framework

An ideal genome assembly is highly contiguous, complete, and correct. These three principles serve as the pillars for a robust assessment, though they can often be contradictory, as optimizing for one can sometimes come at the expense of another [3]. The following sections define and detail the metrics associated with each "C."

Contiguity

Contiguity measures how well an assembly reconstructs long, uninterrupted DNA sequences, reflecting the effectiveness of the assembly process in extending sequences without breaks [3] [11]. It is primarily concerned with the size and number of the assembled fragments.

- N50 / L50: The N50 is defined as the length of the shortest contig or scaffold such that contigs of this length or longer contain 50% of the total assembly length [10] [3]. The L50 is the corresponding number of contigs. In the era of long-read sequencing, a contig N50 over 1 Mb is often considered good for many eukaryotic genomes [10]. A major critique of N50 is that it can be artificially inflated by misassemblies, making it an unreliable standalone metric [11].

- NG50 / LG50: These metrics are analogous to N50 and L50 but are calculated with respect to the estimated genome size rather than the assembly size. This prevents a larger but incomplete assembly from appearing more contiguous than a smaller, more complete one.

- Number of contigs/scaffolds and gaps: The total count of contigs and scaffolds, along with the number and length of gaps between scaffolds, are direct indicators of assembly fragmentation [3].

- Contig-to-Chromosome (CC) Ratio: A recently proposed metric that compensates for the flaws of N50. It is calculated as the number of contigs divided by the number of chromosome pairs. A lower ratio indicates a more contiguous assembly [13].

Completeness

Completeness assesses how much of the entire original genome sequence is present in the final assembly [11]. The goal is to minimize missing regions, whether they are genes or intergenic sequences.

- BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs): BUSCO assesses completeness by searching for a set of highly conserved, single-copy orthologous genes that are expected to be present in a specific lineage. It reports the percentage of these genes found as "complete," "fragmented," "duplicated," or "missing." A BUSCO complete score above 95% is generally considered good [10] [3]. An elevated "duplicated" score can signal a problem with haplotig duplication or assembly errors [11].

- K-mer-based Completeness: This approach compares the k-mers (subsequences of length k) present in the raw sequencing reads to those found in the assembly. The proportion of read k-mers that are also present in the assembly is a direct measure of sequence completeness [13] [3]. Tools like Merqury are commonly used for this purpose [10].

- Mapping Rate: The percentage of original sequencing reads that successfully map back to the assembly can also indicate completeness, with a high mapping rate being desirable [3].

- Flow Cytometry Comparison: A pre-assembly method where the total length of the assembled genome is compared to an independent estimate of genome size obtained via flow cytometry [3].

Correctness

Correctness evaluates the accuracy of each base pair and the larger-scale structural integrity of the assembly [10] [3]. It is often considered the most challenging dimension to measure comprehensively.

- Base-Level Accuracy: This refers to the correctness of individual nucleotides.

- QV (Quality Value): A Phred-scaled score (e.g., QV 40 = 99.99% accuracy) that estimates the probability of an incorrect base call. It can be derived from k-mer comparisons using tools like Merqury [13].

- SNV/Indel Count: The number of single-nucleotide variants and insertions/deletions identified by mapping high-accuracy short reads or by comparing to a gold-standard reference [10] [14].

- Structural-Level Accuracy: This assesses whether the order, orientation, and copy number of sequences are correct.

- Misassembly Detection: Tools like QUAST can identify large-scale errors such as relocations, translocations, and inversions by aligning the assembly to a reference genome [15] [3].

- LTR Assembly Index (LAI): This metric evaluates the assembly quality of repetitive regions, specifically long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons. A higher LAI (e.g., >10 for reference-quality) indicates that complex repetitive regions have been properly resolved [13] [3].

- Frameshift Analysis: The number of frameshifting indels within coding genes can be used as a proxy for assembly errors, as true frameshifts in conserved genes are rare [10].

The table below summarizes these key metrics for a quick reference.

Table 1: Summary of Core Genome Assembly Quality Metrics

| Dimension | Metric | Description | Target Value/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contiguity | N50 / NG50 | Shortest contig length covering 50% of assembly/genome. | >1 Mb is often "good" [10]. |

| Number of Contigs | Total count of contiguous sequences. | Lower is better. | |

| CC Ratio | # Contigs / # Chromosome Pairs. | Compensates for N50 flaws; lower is better [13]. | |

| Completeness | BUSCO | % of conserved single-copy orthologs found. | >95% complete is "good" [10]. |

| K-mer Completeness | % of read k-mers found in the assembly. | Closer to 100% is better [3]. | |

| Mapping Rate | % of reads that map back to the assembly. | Closer to 100% is better [3]. | |

| Correctness | QV (Quality Value) | Phred-scaled base-level accuracy. | QV40 = 99.99% accuracy; higher is better [13]. |

| LAI (LTR Assembly Index) | Completeness of LTR retrotransposon assembly. | >10 for reference-quality [13]. | |

| # of Misassemblies | Large-scale errors (inversions, translocations). | Identified by QUAST; lower is better [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Correctness

While contiguity and completeness can be assessed directly from the assembly and gene sets, evaluating correctness often requires more complex, orthogonal data and methodologies [10]. The following are established protocols for this purpose.

K-mer Spectrum Analysis with Merqury

Objective: To assess base-level accuracy (QV) and completeness without a reference genome. Data Required: Short-read Illumina data from the same individual. Workflow:

- K-mer Counting: Use a k-mer counter (e.g., Meryl) to build a database of all unique k-mers from the short-read data. This represents the "truth" set.

- Assembly K-mer Extraction: Extract all k-mers from the genome assembly.

- Comparison with Merqury: Run Merqury with the short-read k-mer database and the assembly.

- Analysis: Merqury outputs:

- QV Score: A consensus quality value for the entire assembly.

- K-mer Spectra Plot: A visualization showing k-mer multiplicity, which helps identify haplotypic duplications, collapsed repeats, and overall completeness.

- Error Tracks: Files that can be loaded into a genome browser (e.g., IGV) to visually inspect potential errors [10] [13].

Assessing Frameshifts with Transcriptome Data

Objective: To identify frameshifting indels in coding genes, which are often assembly errors. Data Required: High-quality transcript annotations or full-length RNA sequencing data (e.g., from PacBio Iso-Seq) from the same or a closely related sample [10]. Workflow:

- Alignment: Map the transcript sequences to the genome assembly.

- ORF Prediction: Identify open reading frames (ORFs) in the aligned transcripts.

- Frameshift Detection: Scan the alignments for indels that are not multiples of three, which disrupt the reading frame.

- Validation: Manually inspect frameshifts in a genomic context, as some may represent real biological variation. A high frequency of frameshifts in conserved genes strongly indicates assembly errors.

Validation in High-Confidence Regions

Objective: To measure assembly accuracy against a defined "gold standard" set of genomic regions. Data Required: A high-quality reference genome for the same species (but a different individual) and short-read data for the assembled sample [10]. Workflow:

- Define High-Confidence Regions: Map the short-read data from the assembled sample to the reference genome. Exclude regions with abnormal coverage, high variant density, or low mapping quality. The remaining regions are considered high-confidence.

- Align Assembly to Reference: Align the new assembly to the reference genome.

- Calculate Concordance: Measure the concordance (e.g., identity percentage, number of discrepancies) only within the high-confidence regions. This provides a realistic measure of accuracy in regions where the reference is reliable for the sample [10].

Polishing for Near-Perfect Accuracy

Objective: To correct residual errors in a long-read assembly, achieving accuracy suitable for outbreak investigation or high-resolution genomics. Data Required: A long-read (e.g., ONT) assembly and the original long reads, plus high-accuracy short reads (e.g., Illumina) from the same isolate. Experimental Insight: A 2024 benchmarking study on Salmonella outbreak isolates found that near-perfect accuracy (99.9999%) was only achieved by pipelines combining both long- and short-read polishing [14]. Recommended Workflow:

- Initial Assembly: Assemble with Flye.

- Long-Read Polishing: Polish the assembly with Medaka, which was found to be more accurate and efficient than Racon [14].

- Short-Read Polishing: Perform a subsequent round of polishing with a short-read polisher like NextPolish, Pilon, or POLCA. The study showed that Medaka followed by NextPolish was a top-performing combination [14]. Critical Note: The order of operations is crucial. Using a less accurate tool after a more accurate one can re-introduce errors [14].

The logical flow of a comprehensive assembly evaluation, integrating the "3 Cs" and various data types, can be visualized as follows:

Figure 1: A holistic workflow for genome assembly evaluation, integrating the three core dimensions (the "3 Cs") and their associated data requirements.

A Toolkit for the Assembly Scientist

Successful genome assembly and evaluation rely on a suite of bioinformatics tools and reagents. The following table details key solutions and their functions in the evaluation process.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Genome Assembly Evaluation

| Category | Tool / Reagent | Primary Function in Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Assessment Suites | QUAST [15] [3] | Comprehensive quality assessment with/without a reference; reports contiguity metrics and misassemblies. |

| GenomeQC [3] | Interactive web framework for comparing assemblies and benchmarking against gold standards. | |

| GAEP [3] | Comprehensive pipeline using NGS, long-read, and transcriptome data to assess all 3 Cs. | |

| Completeness Tools | BUSCO [3] [11] | Assesses gene space completeness using universal single-copy orthologs. |

| Merqury [10] [13] | Reference-free evaluation of quality (QV) and completeness using k-mers. | |

| Correctness & Polishing | Merqury / Yak [10] | K-mer-based base-level accuracy assessment. |

| Medaka [1] [14] | Long-read polisher that uses raw signal data to correct assembly errors. | |

| Racon [1] | A general long-read polisher. | |

| Pilon [1] | A general short-read polisher. | |

| NextPolish [14] | Short-read polisher identified as highly accurate in benchmarking. | |

| Structural Evaluation | QUAST [15] | Identifies large-scale misassemblies via reference alignment. |

| LAI Calculator [13] | Evaluates assembly quality in repetitive regions via LTR retrotransposon completeness. | |

| Orthogonal Data | PacBio Iso-Seq Data [10] | Full-length transcript sequences for validating gene models and detecting frameshifts. |

| Hi-C / Chicago Data [1] | Proximity-ligation data for scaffolding to chromosome scale and validating structural accuracy. | |

| Illumina Short Reads [10] [14] | High-accuracy reads for k-mer completeness analysis, polishing, and variant detection. |

Benchmarking genome assemblers requires a multi-faceted approach that moves beyond simplistic contiguity statistics. A rigorous evaluation must simultaneously consider contiguity, completeness, and correctness to paint a true picture of assembly quality. As demonstrated, this involves leveraging a suite of tools like QUAST, BUSCO, and Merqury, and employing orthogonal data through defined experimental protocols, such as k-mer analysis and hybrid polishing. The field is moving towards more holistic and biologically informed metrics, such as the LAI and CC ratio, to better capture the nuances of assembly quality. By adopting the comprehensive framework and metrics outlined in this guide, researchers can make informed decisions when selecting assemblers, confidently compare algorithmic performance, and ultimately generate genome assemblies that are not only well-assembled but also biologically accurate and truly useful for downstream scientific discovery.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics research, expanding our knowledge of genome structure, function, and dynamics [16]. The evolution from short-read sequencing to long-read sequencing technologies represents a paradigm shift in our ability to decipher genetic information with unprecedented completeness and accuracy. Short-read technologies, dominated by Illumina sequencing-by-synthesis approaches, have been the workhorse of genomics for over a decade, providing highly accurate (>99.9%) reads typically ranging from 50-300 base pairs [17] [18]. These technologies excel at identifying single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and small insertions/deletions efficiently and cost-effectively, making them ideal for applications like whole genome sequencing (WGS), whole exome sequencing (WES), and gene panel testing [17].

However, the limited read length of these platforms presents significant challenges for resolving complex genomic regions, including structural variations, large repetitive elements, and extreme GC-content regions [18]. Approximately 15% of the human genome remains inaccessible to short-read technologies, including centromeres, telomeres, and large segmental duplications—ironically, some of the most mutable regions of our genome [18]. These limitations have driven the development and refinement of long-read sequencing technologies from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), which can generate reads tens to thousands of kilobases in length, enabling the complete assembly of genomes from telomere to telomere (T2T) [19] [18].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Sequencing Technologies

| Technology | Read Length | Accuracy | Primary Applications | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | 50-300 bp | >99.9% | WGS, WES, gene panels, SNP discovery | Limited resolution of repetitive regions, structural variants |

| PacBio HiFi | 10-25 kb | >99% | De novo assembly, structural variant detection, haplotype phasing | Higher cost per base, requires more DNA input |

| ONT | 10-60 kb (standard); up to >1 Mb (ultra-long) | 87-98% | Real-time sequencing, large structural variants, base modification detection | Higher raw error rate requires correction |

Technical Foundations of Short-Read and Long-Read Sequencing

Short-Read Sequencing Methodologies

Short read sequencing encompasses several technological approaches that determine nucleotide sequences in fragments typically ranging from 50-300 base pairs [17]. Sequencing by synthesis (SBS) platforms utilize polymerase enzymes to replicate single-stranded DNA fragments, employing either fluorescently-labeled nucleotides with reversible blockers that halt the reaction after each incorporation, or unmodified nucleotides that are introduced sequentially while detecting incorporation through released hydrogen ions and pyrophosphate [17]. The sequencing by binding (SBB) approach splits nucleotide incorporation into distinct steps: fluorescently-labeled nucleotides bind to the template without incorporation for signal detection, followed by washing and subsequent extension with unlabeled nucleotides [17]. Alternatively, sequencing by ligation (SBL) employs ligase enzymes instead of polymerase to join fluorescently-labeled nucleotide sequences to the template strand [17].

The exceptional accuracy of short-read technologies (>99.9%) makes them particularly suitable for variant calling applications where base-level precision is critical [18]. This high accuracy, combined with massive throughput capabilities (up to 3000 Gb per flow cell on Illumina NovaSeq 6000) and lower per-base cost, has cemented their position as the first choice for large-scale genomic studies requiring SNP identification and small indel detection [18] [16]. However, their fundamental limitation remains the inability to span repetitive regions or resolve complex structural variations that exceed their read length [18].

Long-Read Sequencing Platforms

Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) Technology

PacBio's single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing utilizes a unique circular template design called a SMRTbell, comprised of a double-stranded DNA insert with single-stranded hairpin adapters on both ends [18]. This structure allows DNA polymerase to repeatedly traverse the circular template, enabling circular consensus sequencing (CCS) that generates highly accurate HiFi (High Fidelity) reads through multiple observations of each base [18]. The technology operates on a SMRT Cell containing millions of zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs)—nanophotonic structures that confine observation volumes to the single-molecule level, allowing real-time detection of nucleotide incorporation events [18] [16].

PacBio systems typically produce reads tens of kilobases in length, with recent advancements enabling read N50 lengths of 30-60 kb and maximum reads exceeding 200 kb [18]. The platform's unique capability to monitor the kinetics of nucleotide incorporation provides inherent access to epigenetic information, allowing direct detection of base modifications such as methylation without specialized sample preparation [17].

Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT)

ONT sequencing employs a fundamentally different approach based on the changes in electrical current as DNA molecules pass through protein nanopores embedded in a membrane [17] [18]. A constant voltage is applied across the membrane, and as negatively-charged single-stranded DNA molecules translocate through the nanopores, each nucleotide base causes characteristic disruptions in the ionic current that can be decoded to determine the DNA sequence [17]. This unique mechanism enables truly real-time sequencing and allows for the longest read lengths currently available, with standard protocols producing reads of 10-60 kb and ultra-long protocols generating reads exceeding 100 kb, with some reaching megabase lengths [18].

A distinctive advantage of the ONT platform is its capacity for direct RNA sequencing without reverse transcription, preserving native nucleotide modification information [17]. The technology's portability (particularly the MinION device) and rapidly improving throughput (up to 180 Gb per PromethION flow cell) have expanded sequencing applications to field-based and point-of-care scenarios [18].

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Long-Read Sequencing Platforms

| Parameter | PacBio (Sequel II) | ONT (PromethION) |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length N50 | 30-60 kb | 10-60 kb (standard); 100-200 kb (ultra-long) |

| Maximum Read Length | >200 kb | >1 Mb |

| Raw Read Accuracy | 87-92% (CLR); >99% (HiFi) | 87-98% |

| Throughput per Flow Cell | 50-100 Gb (CLR); 15-30 Gb (HiFi) | 50-100 Gb |

| Epigenetic Detection | Native detection of base modifications | Native detection of base modifications |

| RNA Sequencing | Requires cDNA synthesis | Direct RNA sequencing |

Benchmarking Genome Assemblers: From Short Reads to Complete Genomes

Performance Evaluation of Short-Read Simulators

Comprehensive benchmarking of computational tools is essential for reliable genomic analysis. A 2023 study evaluated six popular short-read simulators—ART, DWGSIM, InSilicoSeq, Mason, NEAT, and wgsim—assessing their ability to emulate characteristic features of empirical Illumina sequencing data, including genomic coverage, fragment length distributions, quality scores, systematic errors, and GC-coverage bias [20]. The research highlighted that these tools employ either pre-defined "basic" models or "advanced" parameterized custom models designed to mimic genomic characteristics of specific organisms, with significant variability in their ability to faithfully reproduce platform-specific artifacts and biological features [20].

Performance comparisons revealed substantial differences in how accurately these simulators replicated quality score distributions and GC-coverage biases present in real datasets [20]. Tools like InSilicoSeq offered extensive ranges of built-in platform-specific error models for common Illumina sequencers (HiSeq, NovaSeq, MiSeq), while others provided more flexibility for custom parameterization [20]. The study emphasized that careful simulator selection is crucial for generating meaningful synthetic datasets for pipeline benchmarking, particularly for non-model organisms lacking gold-standard reference datasets [20].

Long-Read Assembly Tool Benchmarking

As long-read technologies have matured, numerous assemblers have been developed to leverage their advantages. A comprehensive benchmarking of eleven long-read assemblers—Canu, Flye, HINGE, Miniasm, NECAT, NextDenovo, Raven, Shasta, SmartDenovo, wtdbg2 (Redbean), and Unicycler—using standardized computational resources revealed significant differences in performance [21]. Assemblers employing progressive error correction with consensus refinement, notably NextDenovo and NECAT, consistently generated near-complete, single-contig assemblies with low misassemblies and stable performance across preprocessing types [21]. Flye offered a strong balance of accuracy and contiguity, while Canu achieved high accuracy but produced more fragmented assemblies (3-5 contigs) with substantially longer runtimes [21].

Ultrafast tools like Miniasm and Shasta provided rapid draft assemblies but were highly dependent on preprocessing and required polishing to achieve completeness [21]. The study also demonstrated that preprocessing decisions significantly impact assembly quality, with filtering improving genome fraction and BUSCO completeness, trimming reducing low-quality artifacts, and correction benefiting overlap-layout-consensus (OLC)-based assemblers while occasionally increasing misassemblies in graph-based tools [21].

A separate 2025 benchmarking study of hybrid de novo assembly pipelines combining ONT long-reads with Illumina short-reads found that Flye outperformed all assemblers, particularly when using Ratatosk error-corrected long-reads [5]. Post-assembly polishing significantly improved accuracy and continuity, with two rounds of Racon (long-read-based polishing) followed by Pilon (short-read-based polishing) yielding optimal results [5]. This comprehensive evaluation highlighted that hybrid approaches effectively integrate the long-range continuity of ONT data with the base-level accuracy of Illumina reads, providing a balanced solution for high-quality genome assembly [5].

Telomere-to-Telomere Assembly: Case Studies and Breakthroughs

The Telomere-to-Telomere Assembly Paradigm

Telomere-to-telomere (T2T) assembly represents the ultimate goal of genome sequencing—complete, gap-free chromosome assemblies that include traditionally challenging regions such as centromeres, telomeres, and ribosomal DNA (rDNA) arrays [19] [22]. Long-read technologies have been instrumental in achieving this milestone, with T2T assemblies now completed for multiple species including human, banana, and hexaploid wheat [19] [22]. These complete assemblies reveal unprecedented insights into genome biology, enabling comprehensive characterization of previously inaccessible genomic features and their role in evolution, disease, and fundamental biological processes [19].

The power of T2T assemblies lies in their ability to resolve complex regions that have historically plagued genome projects. Centromeres, characterized by megabase-scale tandem repeats, are essential for chromosome segregation but were previously largely unassembled [19]. Telomeres, composed of repetitive sequences at chromosome ends, protect genomic integrity but vary substantially between species and even within individuals [23]. Ribosomal DNA clusters, comprised of highly similar tandemly repeated genes, challenge assembly algorithms due to their extensive homogeneity [22]. T2T assemblies now enable systematic study of these regions, revealing their architecture, variation, and functional significance.

Plant Genome T2T Assemblies

Banana Genome Assembly

A landmark 2021 study demonstrated the power of ONT long-read sequencing for plant genome assembly, generating a chromosome-scale assembly of banana (Musa acuminata) with five of eleven chromosomes entirely reconstructed in single contigs from telomere to telomere [22]. Using a single PromethION flowcell generating 93 Gb of sequence (177X coverage) with read N50 of 31.6 kb, the assembly achieved remarkable contiguity with the NECAT assembler, producing an assembly comprised of just 124 contigs with a cumulative size of 485 Mbp [22]. Validation using two independent Bionano optical maps (DLE-1 and BspQI enzymes) confirmed assembly accuracy, with only one small contig (380 kbp) flagged as conflictual [22].

This T2T assembly revealed, for the first time, the complete architecture of complex regions including centromeres and clusters of paralogous genes [22]. All eleven chromosome sequences harbored plant-specific telomeric repeats (T3AG3) at both ends, confirming complete assembly of chromosome termini [22]. The remaining gaps were primarily located in rDNA clusters (5S for chromosomes 1, 3, and 8; 45S for chromosome 10) and other tandem and inverted repeats, highlighting that even with long-read technologies, these extremely homogeneous repetitive regions remain challenging to resolve completely [22].

Hexaploid Wheat Genome Assembly

The recent CS-IAAS assembly of hexaploid bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) represents a monumental achievement in plant genomics, producing a complete T2T gap-free genome encompassing 14.51 billion base pairs with all 21 centromeres and 42 telomeres [19] [24]. This assembly utilized a sophisticated hybrid approach combining PacBio HiFi reads (3.8 Tb, ~250× coverage) with ONT ultra-long reads (>100 kbp, 1.8 Tb, ~120× coverage), supplemented with Hi-C, Illumina, and Bionano data [19]. The development of a semi-automated pipeline for assembling reference sequence of T2T (SPART) enabled the integration of these complementary technologies, leveraging the precision of HiFi sequencing and the exceptional contiguity of ONT ultra-long reads [19].

The resulting assembly demonstrated dramatic improvements over previous versions, with contig N50 increasing from 0.35 Mbp in CS RefSeq v2.1 to 723.78 Mbp in CS-IAAS—a 206,694% improvement—while completely eliminating all 183,603 gaps present in the previous assembly [19] [24]. This comprehensive genome enabled the identification of 565.66 Mbp of new sequences, including centromeric satellites (16.05%), transposable elements (68.66%), rDNA arrays (0.75%), and other previously inaccessible regions [19]. The complete assembly facilitated unprecedented analysis of genome-wide rearrangements, centromeric elements, transposable element expansion, and segmental duplications during tetraploidization and hexaploidization, providing comprehensive understanding of wheat subgenome evolution [19].

Computational Methods for Telomere Analysis

The expansion of long-read sequencing has driven development of specialized computational methods for analyzing telomeres. Traditional experimental methods for telomere length measurement, such as terminal restriction fragment (TRF) assay and quantitative fluorescence in situ hybridization (Q-FISH), face limitations including high DNA requirements, labor intensity, and challenges in scaling for high-throughput studies [23]. Computational methods like TelSeq, Computel, and TelomereHunter have been developed to estimate telomere length from short-read sequencing data by quantifying telomere repeat abundance, but these methods show only moderate correlation with experimental techniques (Spearman's ρ = 0.55 between K-seek and TRF in A. thaliana) and remain susceptible to biases from library preparation and PCR amplification [23].

The Topsicle method, introduced in 2025, represents a significant advance by estimating telomere length from whole-genome long-read sequencing data using k-mer and change-point detection analysis [23]. This approach leverages the ability of long reads to span entire telomere-subtelomere junctions, enabling precise determination of the boundary position and subsequent length calculation [23]. Simulations demonstrate robustness to sequencing errors and coverage variations, with application to plant and human cancer cells showing high accuracy comparable to direct telomere length measurements [23]. This tool is particularly valuable because it accommodates the diverse telomere repeat motifs found across different species, unlike previous methods optimized primarily for the human TTAGGG motif [23].

Experimental Design and Methodologies for Genome Assembly

Recommended Workflows for T2T Assembly

Based on benchmarking studies and successful T2T assemblies, optimal genome assembly workflows integrate multiple technologies and analysis steps. For long-read-only assembly, the recommended workflow includes: (1) high-molecular-weight DNA extraction using protocols optimized for long fragments; (2) sequencing with either PacBio HiFi or ONT ultra-long protocols to achieve sufficient coverage (>50X); (3) assembly with assemblers like Flye, NECAT, or NextDenovo that have demonstrated strong performance in benchmarks; (4) iterative polishing with long-read data using tools like Racon or Medaka; and (5) optional short-read polishing with tools like Pilon for maximum base-level accuracy [21] [22] [5].

For hybrid assembly approaches that combine long-read and short-read technologies: (1) sequence with both ONT (for contiguity) and Illumina (for accuracy) platforms; (2) perform pre-assembly error correction of long reads using tools like Ratatosk with short-read data; (3) assemble with hybrid-aware assemblers; (4) conduct multiple rounds of polishing with both long-read and short-read polishers; and (5) validate assembly quality using multiple metrics including BUSCO completeness, Merqury QV scores, and optical mapping [5]. Chromosome-scale scaffolding can be achieved through additional Hi-C or optical mapping data, with the Dovetail Omni-C and Bionano systems providing complementary approaches for validating and improving scaffold arrangements [19] [22].

Diagram 1: Complete T2T Genome Assembly Workflow. This workflow integrates laboratory and computational phases, highlighting the multi-stage process required for successful telomere-to-telomere assembly.

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Genome Assembly

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | Circulomics SRE XL kit | Removal of short DNA fragments | HMW DNA preparation for long-read sequencing |

| Sequencing Kits | PacBio SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0 | Library preparation for PacBio sequencing | HiFi read generation |

| ONT Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSK109) | Library preparation for Nanopore sequencing | Standard long-read generation | |

| Assembly Software | Flye, NECAT, NextDenovo | De novo genome assembly from long reads | Production of contiguous assemblies |

| Polishing Tools | Racon, Medaka | Long-read-based consensus polishing | Error correction after assembly |

| Pilon | Short-read-based polishing | Final base-level accuracy improvement | |

| Validation Tools | BUSCO, Merqury | Assembly completeness and quality assessment | Benchmarking assembly quality |

| Bionano Solve | Optical mapping analysis | Scaffold validation and conflict resolution |

The evolution from short-read to long-read sequencing technologies has fundamentally transformed genomics, enabling complete telomere-to-telomere assemblies that reveal previously inaccessible regions of genomes [19] [18]. Benchmarking studies have demonstrated that both PacBio HiFi and ONT ultra-long reads can produce exceptionally contiguous assemblies, with assembler selection significantly impacting outcomes [21] [5]. The development of specialized computational methods like Topsicle for telomere analysis further enhances the utility of long-read data for investigating fundamental biological questions [23].

As these technologies continue to mature, several trends are shaping the future of genome sequencing and assembly. Continuous improvements in read length and accuracy are making T2T assemblies more routine and accessible [18] [16]. The integration of multiple complementary technologies—PacBio for accuracy, ONT for length, Hi-C for scaffolding, and optical mapping for validation—represents the current state-of-the-art for complex genomes [19] [22]. Computational methods are advancing rapidly to leverage these data, with specialized assemblers and polishers improving both contiguity and accuracy [21] [5].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances translate to more comprehensive understanding of genetic variation and its functional consequences. Complete genome assemblies enable systematic study of previously neglected repetitive regions, revealing their roles in disease, evolution, and genomic stability [23] [19]. As T2T assemblies become more commonplace, we anticipate discoveries linking variation in complex genomic regions to phenotypic outcomes, potentially unlocking new therapeutic targets and diagnostic approaches [18]. The ongoing evolution of sequencing technologies and computational methods promises to further democratize access to complete genome sequencing, ultimately advancing personalized medicine and fundamental biological discovery.

Assembly in Action: Strategies, Tools, and Pipelines for Robust Genome Reconstruction

Genome assembly is a foundational step in genomics, critically influencing downstream applications such as functional annotation, comparative genomics, and variant discovery [21]. The overarching goal of any genome assembler is to reconstruct the complete genome in the fewest possible contiguous pieces (contigs/scaffolds) with the highest base accuracy, while minimizing computational resource consumption [25]. Achieving these "1-2-3 goals" is challenging due to pervasive repetitive sequences and sequencing errors. The human genome, for instance, is estimated to be 66–69% repetitive, making the resolution of these regions paramount for a successful assembly [26]. Over the years, distinct algorithmic paradigms have been developed to tackle these challenges, primarily falling into three categories: Overlap-Layout-Consensus (OLC), graph-based (primarily de Bruijn graphs), and hybrid approaches. This guide provides an objective comparison of these paradigms, drawing on recent benchmarking studies to evaluate their performance, optimal use cases, and computational requirements.

Assembly Paradigms and Core Algorithms

Overlap-Layout-Consensus (OLC)

The OLC paradigm, a classical approach adapted for long reads, involves three main steps. First, the Overlap step performs an all-versus-all pairwise comparison of reads to find overlaps. Second, the Layout step uses these overlaps to construct a graph and determine the order and orientation of reads. Finally, the Consensus step derives the final sequence by determining the most likely nucleotide at each position from the multiple alignments [25] [26]. This paradigm is naturally suited for long, error-prone reads because it can tolerate a higher error rate during the initial overlap detection. Modern OLC assemblers have introduced significant optimizations to handle the computational burden of all-versus-all read comparison. For example, Flye clusters long reads from the same genomic locus to reduce comparisons [26], Redbean segments reads to speed up alignment [26], and Shasta uses run-length encoding to compress homopolymers, mitigating a common error type in Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) data [26].

Graph-Based (de Bruijn Graph)

In contrast to OLC, the de Bruijn graph approach breaks all reads into short, fixed-length subsequences called k-mers. The assembly is then reconstructed by finding a path that traverses every k-mer exactly once (an Eulerian path) [25]. This method is highly efficient for large volumes of accurate, short-read data because it avoids the computationally expensive all-versus-all read comparison. However, the process of splitting reads into k-mers can cause a loss of long-range information, making it less ideal for resolving long repeats when using only short reads. While traditionally used for short reads, innovations like the one in GoldRush demonstrate how de Bruijn graph principles can be adapted for long-read assembly by using a dynamic, probabilistic multi-index Bloom filter data structure to achieve linear time complexity and a dramatically reduced memory footprint [26].

Hybrid Assembly

Hybrid assemblers integrate data from both long-read (e.g., ONT, PacBio) and short-read (e.g., Illumina) technologies to leverage their complementary strengths. The long reads provide the contiguity, while the highly accurate short reads correct base-level errors. Strategies vary; some tools follow a "long-read-first" approach where the assembly is primarily built from long reads and then polished with short reads [27] [14]. Others, like WENGAN, implement a "short-read-first" strategy. WENGAN starts by building a de Bruijn graph from short reads, then uses synthetic paired reads derived from long reads to build a "synthetic scaffolding graph" (SSG), which is used to order contigs and fill gaps with long-read consensus sequences [25]. This approach avoids the all-versus-all long-read comparison and efficiently integrates data types from the start.

Table 1: Overview of Genome Assembly Paradigms and Representative Tools

| Assembly Paradigm | Core Principle | Representative Tools | Ideal Sequencing Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overlap-Layout-Consensus (OLC) | Finds overlaps between long reads to build a layout and consensus sequence. | Flye, Canu, Shasta, Redbean, NECAT, NextDenovo [21] [26] | Long-reads only (ONT, PacBio CLR) |

| de Bruijn Graph | Splits reads into k-mers and reconstructs the genome via Eulerian paths. | MEGAHIT, GoldRush (adapted) [25] [26] | Short-reads only (Illumina) |

| Hybrid | Combines long and short reads for scaffolding and error correction. | Unicycler, MaSuRCA, SPAdes, WENGAN [27] [25] [28] | Long-reads + Short-reads |

Benchmarking Performance and Computational Efficiency

Recent large-scale benchmarks provide critical insights into the performance of these paradigms. A 2024 study evaluating polishing tools highlighted that near-perfect accuracy for bacterial genomes (99.9999%) is only achievable with pipelines that combine both long-read assembly and short-read polishing [14].

A comprehensive benchmark of eleven long-read assemblers on microbial genomes found that assemblers employing progressive error correction, notably NextDenovo and NECAT, consistently generated near-complete, single-contig assemblies with low misassemblies. Flye offered a strong balance of accuracy and contiguity, while Canu achieved high accuracy at the cost of more fragmented assemblies (3–5 contigs) and the longest runtimes. Ultrafast tools like Miniasm and Shasta provided rapid drafts but were highly dependent on pre-processing and required polishing for completeness [21].

For the demanding task of human genome assembly, a 2025 benchmarking study found that Flye outperformed all other assemblers, particularly when long reads were error-corrected with Ratatosk prior to assembly [27] [5]. The study also confirmed that polishing, especially two rounds of Racon (long-read) followed by Pilon (short-read), consistently improved both assembly accuracy and continuity [27].

In terms of computational resource usage, a notable departure from the OLC paradigm is GoldRush. When assembling human genomes, GoldRush achieved contiguity (NG50 25.3–32.6 Mbp) comparable to Shasta and Flye, but did so using at most 54.5 GB of RAM. This is a fraction of the resources required by Flye (329.3–502.4 GB) and Shasta (884.8–1009.2 GB), demonstrating the potential for new algorithms to drastically improve scalability [26].

Table 2: Performance and Resource Usage of Select Assemblers from Benchmarking Studies

| Assembler | Paradigm | Contiguity (Human NG50) | Key Strengths | Computational Cost | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flye [27] [26] | OLC | 26.6 - 38.8 Mbp | High accuracy & contiguity balance; top performer in human assembly [27]. | High RAM (329-502 GB), long runtime (>33.7h) [26]. | Standard for large, complex genomes. |

| NextDenovo [21] | OLC | N/A (Microbial) | Near-complete microbial assemblies; low misassemblies; stable performance [21]. | N/A | Prokaryotic genomics; high-contiguity microbial assemblies. |

| Shasta [21] [26] | OLC | 29.7 - 39.6 Mbp | Ultrafast assembly; suitable for haploid assembly [26]. | Very High RAM (885-1009 GB) [26]. | Rapid draft assembly of large genomes. |

| GoldRush [26] | Graph-based | 25.3 - 32.6 Mbp | Linear time complexity; low RAM (<54.5 GB); correct assemblies [26]. | Low RAM, fast (<20.8h for human) [26]. | Resource-constrained environments; large-scale projects. |

| Unicycler [28] | Hybrid | N/A (Bacterial) | Superior for bacterial genomes; produces contiguous, circular assemblies [28]. | N/A | Bacterial pathogen genomics; complete circular genomes. |

| WENGAN [25] | Hybrid | 17.24 - 80.64 Mbp | High contiguity & quality; efficient; effective at low long-read coverage [25]. | Low computational cost (187-1200 CPU hours) [25]. | Human and large eukaryotic genomes. |

Experimental Protocols in Benchmarking Studies

To ensure the reproducibility of assembly benchmarks, studies follow rigorous, standardized protocols. Below is a detailed methodology common to recent comprehensive evaluations.

Data Acquisition and Pre-processing

Benchmarks typically use well-characterized reference samples, such as the HG002 (NA24385) human sample from the Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) consortium [27] [5]. Data includes both long reads (e.g., ~47x coverage from ONT PromethION) and short reads (e.g., ~35x coverage from Illumina NovaSeq 6000) [5]. Pre-processing is a critical step that can markedly affect assembly quality. Common procedures include:

- Filtering: Removes low-quality reads to improve genome fraction and BUSCO completeness [21].

- Trimming: Trims adapters and low-quality bases to reduce artifacts [21].

- Error Correction: Correcting long reads before assembly (e.g., with Ratatosk) can benefit OLC-based assemblers, though it may occasionally increase misassemblies in graph-based tools [21] [27].

Assembly Execution and Polishing

The selected assemblers are run on the pre-processed reads using standardized computational resources. A key finding across studies is that polishing is essential for achieving high accuracy with long-read assemblies [27] [14]. The optimal polishing strategy identified in multiple benchmarks is:

- Long-read polishing: First, perform one or more rounds of polishing using long reads themselves, with tools like Medaka or Racon. Medaka has been shown to be more accurate and efficient than Racon [14].

- Short-read polishing: Follow with one or more rounds of polishing using high-accuracy short reads. Tools like NextPolish, Pilon, Polypolish, and POLCA perform similarly, with NextPolish showing the highest accuracy in some studies [14]. The order matters—using less accurate tools after more accurate ones can introduce errors [14].

Quality Assessment and Metrics

Assemblies are evaluated using a suite of complementary metrics to assess different aspects of quality:

- Contiguity: Assessed via N50/NG50 (the contig length at which 50% of the genome is assembled) and contig count [21] [26].

- Completeness: Measured with BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs), which quantifies the presence of expected evolutionarily conserved genes [21] [27].

- Base-level Accuracy: Evaluated using Merqury (which computes consensus quality values, QV) and variant calling [27] [26].

- Structural Accuracy: Tools like QUAST report misassemblies and the NGA50, which is the NG50 after breaking contigs at misassembly sites [27] [26].

- Gene-Level Accuracy: The

asmgeneutility in minimap2 can be used to assess the accuracy of gene regions [26].

Diagram Title: Standard Workflow for Benchmarking Genome Assemblers

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Bioinformatics Tools and Resources for Genome Assembly and Evaluation

| Tool / Resource | Category | Primary Function | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flye | Assembler | OLC-based long-read assembly for large genomes. | [21] [27] [26] |

| Unicycler | Assembler | Hybrid assembler optimized for bacterial genomes. | [28] |

| Medaka | Polishing | Long-read polisher for ONT data; accurate and efficient. | [14] |

| Racon | Polishing | Consensus-based polisher for long reads. | [27] [14] |

| NextPolish | Polishing | Short-read polisher; high accuracy. | [14] |

| Pilon | Polishing | Short-read polisher for improving draft assemblies. | [27] |

| QUAST | Evaluation | Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies. | [27] [26] |

| BUSCO | Evaluation | Assesses assembly completeness based on conserved genes. | [21] [27] |

| Merqury | Evaluation | Evaluates consensus quality (QV) and assembly accuracy. | [27] [26] |

| HG002/NA24385 | Reference | GIAB reference material for benchmarking human assemblies. | [27] [5] |

The evidence from recent benchmarking studies indicates that there is no single "universally optimal" assembler; the choice depends on the organism, data type, and computational resources [21].

- For large, complex eukaryotic genomes (e.g., human): Flye is a robust, high-performing choice, especially when combined with Ratatosk pre-correction and a Racon-Medaka-Pilon polishing strategy [27]. For projects with limited computational resources, GoldRush offers a compelling alternative with linear time complexity and minimal RAM usage without sacrificing contiguity [26].

- For bacterial genomes: Unicycler is the superior approach, reliably producing contiguous and often circularized genomes from hybrid data [28].

- To achieve the highest possible accuracy: A hybrid approach that combines long-read assembly with both long- and short-read polishing is essential. This is particularly critical for applications like outbreak source tracking, where near-perfect accuracy is required [14].

Ultimately, assembler choice and pre-processing methods jointly determine the accuracy, contiguity, and computational efficiency of the final genome assembly, and should be carefully considered in the context of the specific research goals [21].

Long-read sequencing technologies have revolutionized genomics by enabling the assembly of complex genomic regions that were previously intractable. The choice of de novo assembler is a critical decision that directly impacts the contiguity, accuracy, and completeness of the resulting genome. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of four prominent long-read assemblers—Flye, NextDenovo, Canu, and Shasta—within the established context of genome assembler benchmarking research. We synthesize findings from recent, rigorous studies to provide researchers and bioinformaticians with a data-driven foundation for selecting appropriate tools for their projects.

Performance Benchmarks and Comparative Analysis

Comprehensive benchmarking studies provide critical insights into the strengths and weaknesses of each assembler. Performance varies based on the genome being assembled, read characteristics, and computational resources.

Table 1: Summary of Assembler Performance Based on Recent Benchmarking Studies

| Assembler | Assembly Strategy | Contiguity (N50) | Completeness (BUSCO) | Base Accuracy | Computational Speed | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flye | Assembly Then Correction (ATC) | Consistently High [27] | High [27] | High (especially with polishing) [27] | Moderate to Fast [21] | Excellent balance of accuracy and contiguity; robust performance [27] [21] |

| NextDenovo | Correction Then Assembly (CTA) | Very High [29] [21] | Near-Complete [21] | Very High (>99%) [29] | Very Fast [29] [21] | High speed and accuracy; efficient for noisy reads and large genomes [29] |

| Canu | Correction Then Assembly (CTA) | High (can be fragmented) [21] | High [21] | High [21] | Slow [29] [21] | High accuracy; thorough error correction [21] |

| Shasta | Assembly Then Correction (ATC) | Variable [21] | Requires Polishing [21] | Requires Polishing [21] | Ultrafast [21] | Extremely rapid assembly; good for initial drafts [21] |

Table 2: Performance on Human and Microbial Genomes

| Assembler | Human Genome (HG002) Performance [27] | Microbial Genome Performance [21] |

|---|---|---|

| Flye | Top performer, especially with error-corrected reads and polishing [27]. | Strong balance of accuracy and contiguity; sensitive to input read quality [21]. |

| NextDenovo | Validated for population-scale human assembly; accurate segmental duplication resolution [29]. | Consistently generates near-complete, single-contig assemblies with low misassemblies [21]. |

| Canu | Not the top performer in recent human benchmarks [27]. | High accuracy but often produces 3–5 contigs; longest runtimes [21]. |

| Shasta | Performance not specifically highlighted in the human benchmark [27]. | Provides rapid drafts but is highly dependent on pre-processing; requires polishing for completeness [21]. |

Detailed Methodologies of Key Experiments

The performance data presented above is derived from standardized benchmarking protocols. Understanding these methodologies is crucial for interpreting the results and designing your own experiments.

Benchmarking of Hybrid De Novo Assembly for Human Genomes

A 2025 study provided a comprehensive evaluation of assemblers using the HG002 human reference material [27].

- Sequencing Data: The benchmark utilized whole-genome sequencing data from Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) for long reads and Illumina for short-read data [27].

- Assemblers & Polishing Tested: The study evaluated 11 pipelines, including Flye, NextDenovo, Canu, and Shasta. These were combined with four different polishing schemes (e.g., Racon, Pilon). The best-performing pipeline was further validated on non-reference human and non-human samples [27].

- Evaluation Metrics: Assembly quality was assessed using QUAST (for contiguity and misassembly metrics), BUSCO (for completeness based on universal single-copy orthologs), and Merqury (for base-level accuracy). Computational costs were also analyzed [27].

- Key Workflow: The optimal pipeline identified involved error correction of long reads with Ratatosk, assembly with Flye, and polishing with two rounds of Racon followed by Pilon [27].

Evaluation of Error Correction and Assembly for Noisy Long Reads

The development and assessment of NextDenovo involved rigorous benchmarking against other CTA assemblers [29].

- Data Sets: Both simulated data and real ONT "ultra-long" read data from the CHM13 human genome were used. The real data had an average read length of 91.21 kb [29].

- Compared Tools: NextDenovo was benchmarked against Consent, Canu, and Necat for its error correction module, and against a wider range of assemblers for the final assembly [29].

- Evaluation Metrics: For error correction, the study measured correction speed, the proportion of data successfully corrected, the final error rate of corrected reads, and the chimeric read rate. For the final assembly, standard metrics like contiguity and completeness were used [29].

Benchmarking Long-Read Assemblers for Prokaryotic Genomics

A study focused on microbial genomics benchmarked eleven long-read assemblers using standardized computational resources [21].

- Data and Pre-processing: Assemblies were evaluated across different pre-processing methods (raw, filtered, trimmed, and corrected reads) to assess the impact of data quality [21].

- Standardized Resources: All assemblers were run using the same computational environment to ensure a fair comparison of runtime and resource consumption [21].

- Evaluation Metrics: Assemblies were judged on runtime, standard contiguity metrics (N50, total length, contig count), GC content deviation, and completeness assessed via Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) [21].

Workflow Visualization of Assembly Strategies

Long-read assemblers primarily employ one of two core strategies. The diagram below illustrates the steps and logical relationships involved in the "Correction Then Assembly" (CTA) and "Assembly Then Correction" (ATC) approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key bioinformatics tools and resources essential for conducting a robust assembly benchmark or performing genome assembly, as cited in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genome Assembly and Benchmarking

| Tool / Resource | Function | Relevance in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| QUAST | Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies | Used to evaluate contiguity statistics (N50, contig count) and identify potential misassemblies [27]. |

| BUSCO | Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs | Assesses assembly completeness by searching for a set of evolutionarily conserved genes expected to be present in single copy [27] [21]. |

| Merqury | Reference-free assembly evaluation suite | Evaluates base-level accuracy and quality value (QV) scores of an assembly using k-mer spectra [27]. |

| Racon | Ultrafast consensus module for genome assembly | Used as a polishing tool to correct errors in draft assemblies, often applied multiple times for best results [27]. |

| Pilon | Integrated tool for variant calling and assembly improvement | Used after Racon for final polishing, often leveraging Illumina short-read data for higher base accuracy [27]. |

| Ratatosk | Long-read error correction tool | Used to pre-correct ONT long reads before assembly with Flye, leading to superior performance [27]. |

| Oxford Nanopore (ONT) Data | Source of long-read sequencing data | Provides long reads (often >100 kb) crucial for spanning repeats; characterized by higher noise than other technologies [27] [29]. |

| Illumina Data | Source of short-read sequencing data | Used for polishing assemblies to achieve high base accuracy and for hybrid assembly approaches [27]. |

De novo genome assembly is a foundational process in genomics, enabling the decoding of genetic information for non-model organisms and providing critical insights into genome structure, evolution, and function [30]. The complete workflow, from raw sequencing reads to chromosome-scale assemblies, has been revolutionized by long-read sequencing technologies and proximity-ligation methods like Hi-C. However, constructing an optimal genome assembly requires careful selection of tools and strategies at each step, as the synergistic combination of sequencing technologies and specific software programs critically impacts the final output quality [31]. This guide provides an objective comparison of performance across assembly, polishing, and scaffolding tools, supported by experimental data from recent benchmarking studies, to inform researchers designing genome assembly pipelines.

Sequencing Platforms and Data Considerations

The choice of sequencing technology fundamentally influences assembly quality by determining the initial read characteristics. Second-generation sequencing (SGS) platforms like Illumina NovaSeq 6000 and MGI DNBSEQ-T7 provide highly accurate short reads (up to 99.5% accuracy) but struggle with repetitive regions and heterozygosity, often resulting in fragmented assemblies [31]. Third-generation sequencing (TGS) platforms, including Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), address these limitations by producing long reads spanning repetitive regions, despite having higher error rates (5-20%) [31].

Research indicates that input data with longer read lengths generally produce more contiguous and complete assemblies than shorter read length data with higher coverage [1]. A comprehensive study assembling yeast genomes found that ONT reads with R7.3 flow cells generated more continuous assemblies than those from PacBio Sequel, despite homopolymer-based errors and chimeric contigs [31]. For optimal results, more than 30× nanopore data is recommended, with quality highly dependent on subsequent polishing using complementary data [30].

Table 1: Sequencing Platform Characteristics

| Platform | Read Length | Error Rate | Error Profile | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Short (150-300 bp) | <0.1% [1] | Substitution errors [31] | Polishing, variant calling |

| PacBio SMRT | Long (10-20 kb) | <1% [1] | Random errors | De novo assembly, repetitive regions |

| ONT | Long (up to hundreds of kb) | <5% [1] | Indel errors [31] | Structural variants, base modification |

Genome Assemblers Performance Comparison

Assembly Algorithms and Strategic Selection

De novo assemblers employ different algorithms with distinct advantages. Canu performs extensive error correction and trimming using overlap-consensus methods based on string graph theory, making it suitable for highly accurate assemblies despite substantial computational requirements [1] [31]. Flye identifies "disjointigs" and resolves repeat graphs using a generalized Bruijn graph approach, balancing contiguity and computational efficiency [1] [31]. WTDBG2 (now RedBean) uses a fuzzy DeBruijn algorithm optimized for speed with minimal computational resources [1] [31]. NECAT employs a progressive two-step error correction specifically designed for Nanopore raw reads [30].

The performance of these tools varies significantly based on coverage depth, with studies showing coverage depth has a substantial effect on final genome quality [30]. For low coverages (<16×), SPAdes has demonstrated superior N50 values compared to other assemblers in benchmarking studies [32].

Comparative Performance Metrics

A systematic evaluation of nine de novo assemblers for ONT data across different coverage depths revealed dramatic variations in contiguity among tools [30]. Another study benchmarking seven popular assemblers found they could be grouped into two classes based on N50 values, with SPAdes, Velvet, Discovar, MaSuRCA, and Newbler producing higher average N50 values than SOAP2 and ABySS across different coverage values [32].

Hybrid assemblers like MaSuRCA extend accurate SGS reads to their maximum unique length, connecting these "super-reads" using long TGS reads, which can mitigate the high error rates of TGS platforms [31]. For human genome assembly, a comprehensive benchmark of 11 pipelines found Flye outperformed all assemblers, particularly when using Ratatosk error-corrected long reads [33].

Table 2: Genome Assembler Performance Comparison

| Assembler | Algorithm Type | Key Characteristics | Optimal Coverage | Computational Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canu | Overlap-Layout-Consensus | Multiple error correction rounds; high accuracy [31] | High (>50×) | High [30] [31] |

| Flye | Generalized Bruijn Graph | Efficient repeat resolution; good contiguity [31] | Moderate (30-50×) | Moderate [33] |

| WTDBG2 | Fuzzy DeBruijn Graph | Fast assembly with minimal resources [1] | Moderate (30-50×) | Low [31] |

| NECAT | Progressive correction | Optimized for Nanopore reads [30] | Moderate (30-50×) | Moderate |

| MaSuRCA | Hybrid | "Super-reads" from SGS with TGS links [31] | Varies by data type | Moderate |

Polishing Strategies for Accuracy Improvement

Polishing strategies are essential for correcting errors in initial assemblies. Polishers fall into two categories: "sequencer-bound" tools like Nanopolish and Medaka that utilize raw signal information, and "general" polishers like Racon and Pilon applicable to any sequencing platform [1]. Research indicates that iterative polishing progressively improves assembly accuracy, making previously unmappable reads available for subsequent rounds [1].

The most effective approach often combines multiple polishers. In benchmarking studies, the optimal polishing strategy involved two rounds of Racon followed by Pilon polishing [33]. Another study found that a combined Racon/Medaka/Pilon approach produced the most accurate final genome assembly [1]. For ONT data specifically, more than 30× coverage is recommended, with quality highly dependent on polishing using next-generation sequencing data [30].

Hi-C Scaffolding Tools Comparison

Scaffolding Algorithms and Approaches

Hi-C technology leverages proximity-based ligation and massively parallel sequencing to identify chromatin interactions across the entire genome, enabling contig grouping, ordering, and orientation into chromosome-scale assemblies [34]. The underlying principle is that Hi-C signal strength is stronger within chromosomes than between them, and within chromosomal regions, signals are more robust between physically proximate contigs [35].

Multiple Hi-C scaffolding tools have been developed with different computational strategies:

- YaHS creates a contact matrix by cutting contigs at essential breakpoints, builds a graph, and produces scaffolded outcomes after refinements [35].

- SALSA2 builds a hybrid graph combining information from ambiguous edges derived from the GFA (Graphical Fragment Assembly) and edges from Hi-C reads [35].