Beyond the Black Box: A Researcher's Guide to Validating In Silico Predictions in Biomedicine

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of in silico predictions, a critical step for their adoption in biomedical research and drug development.

Beyond the Black Box: A Researcher's Guide to Validating In Silico Predictions in Biomedicine

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of in silico predictions, a critical step for their adoption in biomedical research and drug development. It explores the foundational principles establishing the need for rigorous validation and surveys the methodological landscape, from AI-driven variant effect predictors to genome-scale metabolic models. The content addresses common troubleshooting and optimization challenges, including data quality and model interpretability, and culminates in a detailed analysis of validation frameworks and comparative performance assessments. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current best practices and future directions to enhance the reliability and impact of computational predictions in preclinical and clinical research.

The Critical Imperative: Why Validating In Silico Models is Non-Negotiable

The Promise and Peril of AI in Biomedicine

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into biomedicine represents a paradigm shift, offering unprecedented capabilities in disease diagnosis, drug discovery, and personalized therapy design. However, the transition of these powerful in silico tools from research prototypes to validated clinical assets is fraught with challenges. The true promise of AI in biomedicine hinges not merely on algorithmic sophistication but on rigorous validation and a clear-eyed understanding of its limitations within specific biological contexts. This guide objectively compares the performance of various AI approaches and tools, framing their utility within the critical thesis that robust, context-aware validation is the cornerstone of reliable AI application in biomedicine.

Performance Comparison of AI Models in Biomedical Applications

Diagnostic Performance: AI vs. Physicians

A 2025 meta-analysis of 83 studies provides a comprehensive comparison of generative AI models against healthcare professionals, revealing a nuanced performance landscape [1].

Table 1: Diagnostic Performance of Generative AI Models Compared to Physicians [1]

| Comparison Group | Accuracy of Generative AI | Performance Difference | Statistical Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicians (Overall) | 52.1% (95% CI: 47.0–57.1%) | Physicians +9.9% (95% CI: -2.3 to 22.0%) | p = 0.10 (Not Significant) |

| Non-Expert Physicians | 52.1% | Non-Experts +0.6% (95% CI: -14.5 to 15.7%) | p = 0.93 (Not Significant) |

| Expert Physicians | 52.1% | Experts +15.8% (95% CI: 4.4–27.1%) | p = 0.007 (Significant) |

Key Findings: While generative AI has not yet achieved expert-level diagnostic reliability, several specific models—including GPT-4, GPT-4o, Llama 3 70B, Gemini 1.5 Pro, and Claude 3 Opus—demonstrated performance comparable to, or slightly higher than, non-expert physicians, though these differences were not statistically significant [1]. This highlights AI's potential as a diagnostic aid while underscoring the perils of over-reliance without appropriate human oversight.

Performance of In Silico Tools for Variant Effect Prediction

The validation of AI tools for predicting the functional impact of genetic variants is critical for precision medicine. A 2025 study assessed the performance of in silico prediction tools on a panel of cancer genes, revealing significant gene-specific variations in performance [2].

Table 2: Gene-Specific Performance of In Silico Prediction Tools for Missense Variants [2]

| Gene | Variant Type Assessed | Reported Sensitivity for Pathogenic Variants | Reported Sensitivity for Benign Variants | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TERT | Pathogenic | < 65% | Not Specified | Inferior sensitivity for pathogenic variants. |

| TP53 | Benign | Not Specified | ≤ 81% | Inferior sensitivity for benign variants. |

| BRCA1 | Pathogenic/Benign | Data Shown* | Data Shown* | Performance is dependent on the algorithm's training set. |

| BRCA2 | Pathogenic/Benign | Data Shown* | Data Shown* | Performance is dependent on the algorithm's training set. |

| ATM | Pathogenic/Benign | Data Shown* | Data Shown* | Performance is dependent on the algorithm's training set. |

Note: The study provided quantitative data for BRCA1, BRCA2, and ATM, demonstrating that performance varies significantly by gene and the specific "truth" dataset used for training [2]. This gene-specific performance underscores a major peril: applying in silico tools in a one-size-fits-all manner without gene-specific validation can lead to inaccurate predictions.

Experimental Protocols for Validating AI in Biomedicine

Validation of AI-Driven In Silico Oncology Models

The promise of AI in accelerating oncology research depends on rigorous validation against biological reality. The following workflow details a standard protocol for validating AI-driven predictive frameworks, as employed in cutting-edge research [3].

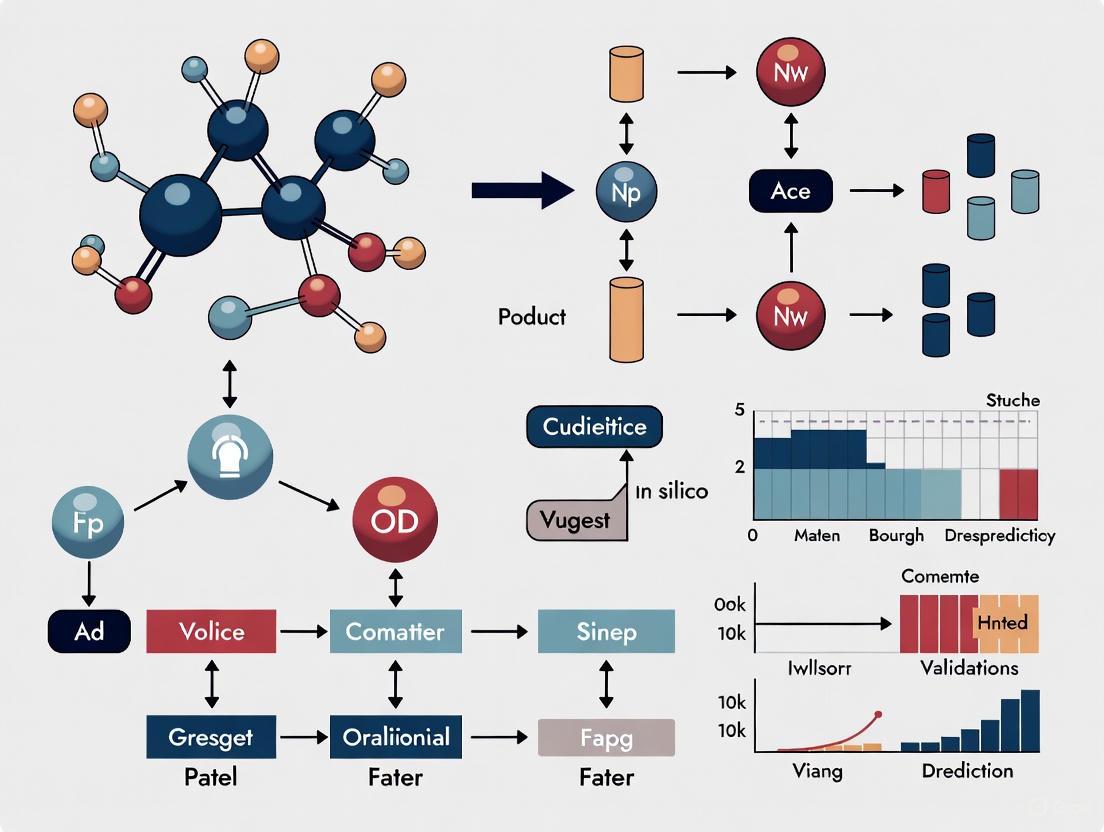

Diagram 1: AI Oncology Model Validation Workflow

Detailed Methodology:

- Input Multi-Omics Data: AI models are trained on large-scale biological datasets, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics [3].

- AI Model Prediction: Machine learning algorithms, particularly deep learning, are used to simulate tumor behavior, predict drug responses, and identify synergistic drug combinations [3].

- Generate In Silico Hypothesis: The model outputs a testable prediction (e.g., "Tumor with mutation X will respond to drug Y").

- Experimental Validation (Cross-Validation with Experimental Models): AI predictions are rigorously compared against results from biologically relevant systems [3]:

- Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDXs): Predictions of drug efficacy are validated against the observed response in a PDX model carrying the same genetic mutation.

- Organoids and Tumoroids: 3D cell cultures that mimic patient-specific tumor biology are used for high-throughput validation of drug sensitivity predictions.

- Longitudinal Data Integration: Time-series data from experimental studies, such as tumor growth trajectories in PDX models, are fed back into the AI algorithms to refine and improve their predictive accuracy [3].

- Refined Predictive Model: The validated and refined model is deployed for improved preclinical research decisions.

Validation of Variant Effect Prediction Tools

For AI tools that predict the impact of genetic variants, validation requires a different, evidence-based approach, as outlined in the following protocol [2].

Diagram 2: Variant Prediction Tool Validation

Detailed Methodology:

- Curate Benchmark Dataset: Establish a gene-specific set of variants with clinically and functionally established pathogenicity or benignity. This serves as the "ground truth" [2].

- Apply In Silico Tools & Recommended Thresholds: Run the curated variant set through multiple in silico prediction tools, applying the score thresholds recommended by guidelines such as those from the ClinGen Sequence Variant Interpretation Working Group [2].

- Calculate Gene-Specific Sensitivity & Specificity: Quantitatively compare the tool's predictions against the benchmark dataset. The 2025 study highlighted that sensitivity for pathogenic variants in the TERT gene was below 65%, and sensitivity for benign TP53 variants was ≤81%, demonstrating that performance is not uniform across genes [2].

- Assess Structural Impact: For genes with insufficient validation data, where gene-agnostic score cutoffs must be used, the study suggests considering the structural impact of missense variants on the protein as an additional line of evidence [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The validation of AI predictions in biomedicine relies on a suite of sophisticated experimental models and computational resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions for Validating AI Predictions

| Tool / Material | Type | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDXs) | Biological Model | Provides an in vivo model that retains key characteristics of the original patient tumor for validating drug response predictions [3]. |

| Organoids & Tumoroids | Biological Model | 3D in vitro cultures that mimic patient-specific tumor architecture and drug response, enabling higher-throughput functional validation [3]. |

| Multi-Omics Datasets | Data Resource | Integrated genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data used to train AI models and provide a holistic view of tumor biology [3]. |

| CRISPR-Based Screens | Experimental Tool | Used to generate functional data on gene function and variant impact, which can be used to train or benchmark AI prediction models [3]. |

| In Silico Prediction Tools | Computational Tool | Algorithms (e.g., for variant effect) that require gene-specific validation against established clinical and functional benchmarks before reliable deployment [2]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Computational Resource | Provides the necessary computational power to run complex AI simulations and analyze large-scale biological datasets in real-time [3]. |

The integration of AI into biomedicine is a double-edged sword. Its promise is demonstrated by diagnostic capabilities rivaling non-expert physicians and sophisticated in silico models that can accelerate drug discovery and personalize therapies [1] [3]. However, the peril lies in the uncritical application of these tools. Key challenges include significant gene-specific performance variability in predictive tools, the "black box" nature of many models, and the critical need for rigorous, biologically-grounded validation against experimental and clinical data [2] [4] [3]. The path forward requires a disciplined focus on validation, ensuring that the powerful promise of AI is realized through a steadfast commitment to scientific rigor and contextual understanding.

The integration of in silico methodologies—computational simulations, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning—has revolutionized drug discovery and biomedical research. These approaches leverage predictive modeling and large-scale data analysis to identify potential drug candidates, therapeutic targets, and disease mechanisms with unprecedented speed and scale. However, the inherent gap between computational predictions and biological reality remains a significant challenge. Experimental validation serves as the critical bridge across this divide, transforming theoretical predictions into biologically relevant and clinically actionable knowledge. This guide objectively compares current validation methodologies and their performance across different research applications, providing researchers with a framework for robustly confirming their in silico findings.

The validation process ensures that computational models provide reliable evidence for regulatory evaluation and clinical decision-making. As noted in assessments of in silico trials, regulatory acceptance depends on comprehensive verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification [5]. This paradigm establishes a methodological triad where in silico experimentation formally complements traditional in vitro and in vivo approaches [6].

Comparative Analysis of Validation Frameworks and Performance

Table 1: Performance Metrics of In Silico Predictions Across Validation Studies

| Application Domain | In Silico Method | Key Validation Metrics | Performance Outcome | Experimental Validation Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast Cancer Drug Discovery | Network Pharmacology & Molecular Docking | Binding affinity (kcal/mol), Apoptosis induction, ROS generation | Strong binding (SRC: -9.2; PIK3CA: -8.7); Significant proliferation inhibition & apoptosis | MCF-7 cell assays: proliferation, apoptosis, migration, ROS [7] |

| Lipid-Lowering Drug Repurposing | Machine Learning (Multiple algorithms) | Predictive accuracy, Clinical data correlation, In vivo lipid parameter improvement | 29 FDA-approved drugs identified; 4 confirmed in clinical data; Significant blood lipid improvement in animal models | Retrospective clinical data analysis, standardized animal studies [8] |

| Cancer Variant Curation | In silico prediction tools (ClinGen) | Sensitivity for pathogenic variants, Specificity for benign variants | Gene-specific performance: TERT pathogenic sensitivity <65%; TP53 benign sensitivity ≤81% | Comparison against established pathogenic/benign variant databases [2] |

| Virtual Cohort Validation | Statistical web application (R/Shiny) | Demographic/clinical variable matching, Outcome simulation accuracy | Enables validation of virtual cohorts against real datasets for in silico trials | Comparison of virtual cohort outputs with real patient data [9] |

Table 2: Validation Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

| Validation Type | Core Protocol | Key Parameters Measured | Typical Duration | Regulatory Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In Vitro Cellular Assays | Cell culture, treatment with predicted compounds, functional assessment | Cell proliferation, Apoptosis markers, Migration/invasion, ROS generation, Protein expression | 24-72 hours (acute) to weeks (chronic) | Good Laboratory Practice (GLP); FDA/EMA guidelines for preclinical studies [7] |

| In Vivo Animal Studies | Administration to disease models, physiological monitoring | Blood parameters, Tissue histopathology, Survival, Organ function, Toxicity markers | 1-12 weeks | Animal welfare regulations; 3Rs principle (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) [8] |

| Clinical Data Correlation | Retrospective analysis of patient databases, EHR mining | Laboratory values, Treatment outcomes, Adverse events, Biomarker correlations | Variable (based on dataset timeframe) | HIPAA compliance; Institutional Review Board approval; Data anonymization [8] |

| Molecular Interaction Studies | Molecular docking, Dynamics simulations | Binding affinity, Bond formation, Complex stability, Energy calculations | Hours to days (computational time) | Credibility assessment per ASME V&V-40 standard [5] |

Experimental Design: Methodologies for Robust Validation

Integrated Computational-Experimental Workflows

The most successful validation strategies employ interconnected workflows that systematically bridge computational predictions and biological confirmation. The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive validation pipeline that integrates multiple experimental approaches:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Cellular Assay Protocols for Candidate Validation

Cell Viability and Proliferation Assay (MTT/XTT)

- Purpose: Quantify anti-proliferative effects of predicted compounds

- Procedure: Seed MCF-7 cells (5,000 cells/well) in 96-well plates. After 24h, treat with serially diluted compounds. Incubate for 48h. Add MTT reagent (0.5mg/mL) for 4h. Dissolve formazan crystals in DMSO. Measure absorbance at 570nm [7].

- Key Parameters: IC50 values calculated using nonlinear regression; statistical significance (p<0.05) via Student's t-test.

Apoptosis Detection (Annexin V/PI Staining)

- Purpose: Quantify programmed cell death induction

- Procedure: Harvest treated cells, wash with PBS, resuspend in binding buffer. Add Annexin V-FITC and propidium iodide. Incubate 15min in dark. Analyze by flow cytometry within 1h.

- Key Parameters: Early apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI-), late apoptotic (Annexin V+/PI+), necrotic (Annexin V-/PI+) populations.

Molecular Docking Validation Protocol

- Purpose: Confirm predicted binding interactions between compounds and targets

- Procedure: Retrieve protein structures from PDB. Prepare protein by removing water, adding hydrogens. Prepare ligand structures, generate 3D conformations. Define binding site. Perform flexible docking using AutoDock Vina or similar. Run molecular dynamics (100ns) to confirm stability [7].

- Key Parameters: Binding affinity (kcal/mol), root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions.

In Vivo Validation Protocol for Lipid-Lowering Compounds

Animal Model Validation

- Purpose: Confirm efficacy of predicted lipid-lowering compounds in physiological system

- Procedure: Use hyperlipidemic mouse model (e.g., ApoE-deficient). Randomize animals to control, standard treatment, and test compound groups (n=8-10/group). Administer compounds orally for 8 weeks. Collect blood at 0, 4, and 8 weeks for lipid profiling. Harvest liver tissue for histopathology and molecular analysis [8].

- Key Parameters: TC, LDL-C, HDL-C, TG levels; liver function markers; tissue histology; statistical analysis via ANOVA with post-hoc testing.

Signaling Pathways and Mechanistic Validation

Validating the mechanistic predictions of in silico models requires elucidating the signaling pathways through which identified compounds exert their effects. The following diagram illustrates key pathways implicated in naringenin's anti-breast cancer activity identified through integrated computational-experimental approaches:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Experimental Validation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Validation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | MCF-7 breast cancer cells, Patient-derived organoids/tumoroids | Provide physiologically relevant human cellular models for efficacy testing | In vitro validation of anti-cancer compounds; mechanism of action studies [7] [3] |

| Animal Disease Models | ApoE-deficient mice, Patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) | Enable efficacy assessment in complex physiological systems | In vivo validation of lipid-lowering compounds; pre-clinical cancer studies [8] [3] |

| Molecular Docking Tools | AutoDock Vina, SwissDock, Molecular Dynamics simulations | Predict and visualize compound binding to protein targets | Validation of predicted drug-target interactions; binding affinity quantification [7] [10] |

| Multi-Omics Analysis Platforms | RNA-Seq, Proteomics, TIMER 2.0, UALCAN, GEPIA2 | Provide comprehensive molecular profiling of drug responses | Mechanism validation; biomarker identification; pathway analysis [7] [3] |

| Validation-Specific Software | R-statistical environment (Shiny), SIMCor platform, Credibility assessment tools | Statistical analysis of virtual cohorts; model credibility assessment | Validation of in silico trial results; regulatory submission preparation [9] [5] |

Bridging the in silico-in vivo gap requires a systematic, multi-layered validation strategy that leverages complementary experimental approaches. The comparative data presented in this guide demonstrates that successful validation integrates computational predictions with increasingly complex biological systems—progressing from molecular and cellular assays to animal models and clinical correlation. The experimental protocols and research reagents detailed here provide researchers with a practical framework for designing rigorous validation studies. As the field evolves toward greater integration of AI and automated discovery platforms [6], the principles of robust experimental validation remain foundational to translating computational predictions into genuine therapeutic advances.

The validation of in silico prediction models is a critical pillar of modern computational biology and drug discovery. For researchers and developers relying on these tools, a rigorous and standardized approach to evaluating performance is non-negotiable. It ensures that computational predictions can be trusted to guide high-stakes decisions, from identifying pathogenic genetic variants to prioritizing novel therapeutic candidates. This guide moves beyond superficial accuracy checks to define a core triad of validation principles—Accuracy, Robustness, and Generalizability—and provides a structured framework for their quantitative assessment. By objectively comparing the application of these metrics across different computational platforms, we aim to establish a consistent benchmark for the field [11].

The Core Metrics of Model Validation

Accuracy: Beyond Simple Correlation

Accuracy assesses how closely a model's predictions match the experimentally observed ground truth. While simple correlation coefficients are commonly used, a truly accurate model for biological discovery must specifically excel at identifying the most biologically relevant changes [12].

- Traditional Metrics: Metrics like the coefficient of determination ((R^2)), Mean Squared Error (MSE), and Pearson correlation coefficient ((r)) measure the overall agreement between predicted and observed values across all data points. For example, a model predicting gene expression might achieve a high (R^2), indicating it captures global expression trends well [12].

- The AUPRC Advantage: For many tasks, the primary goal is not perfect overall prediction but the correct identification of a critical subset, such as differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in a perturbation experiment or pathogenic variants in a clinical dataset. In these class-imbalanced scenarios where "positive" hits are rare, the Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) is a more informative and biologically relevant metric than the more common Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC-ROC). A high AUPRC indicates the model can precisely identify true positives while minimizing false positives, which is essential for prioritizing expensive experimental validation [12].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Assessing Predictive Accuracy

| Metric | What It Measures | Interpretation | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| (R^2) (R-squared) | Proportion of variance in the outcome that is predictable from the inputs. | Closer to 1.0 indicates better overall fit. | General continuous outcome prediction (e.g., gene expression levels). |

| AUPRC | Precision and recall for identifying a specific class (e.g., DEGs, pathogenic variants). | Closer to 1.0 indicates high precision and recall for the positive class. | Class-imbalanced problems; identifying critical biological signals. |

| MSE (Mean Squared Error) | Average squared difference between predicted and actual values. | Closer to 0 indicates higher accuracy. | General model fitting, with emphasis on penalizing large errors. |

Robustness: Consistency Across Input Variations

Robustness evaluates a model's sensitivity to noise, small changes in input data, or variations in benchmarking protocols. A robust model delivers stable, consistent predictions and is not unduly influenced by the specific choice of training data or benchmark sources [11].

A key challenge in the field is the lack of standardized benchmarking practices. Different studies may use different "ground truth" datasets (e.g., CTD vs. TTD for drug-indication associations) or data splitting strategies (e.g., k-fold cross-validation vs. temporal splits), making direct comparisons difficult [11]. A robust model will maintain its performance ranking across these varying evaluation setups. Furthermore, performance should not be heavily correlated with dataset-specific characteristics, such as the number of known drugs per indication or intra-indication chemical similarity [11].

Generalizability: Performance on Unseen Data

Generalizability is the ultimate test of a model's practical utility—its ability to make accurate predictions for new, unseen data that was not represented in its training set. This is distinct from simple testing on a held-out portion of the same dataset [13] [14].

- Cross-Context Prediction: This tests a model's ability to predict outcomes in a completely new biological context. For example, can a model trained on perturbation data from cancer cell lines accurately predict the effects of a perturbation in a neuronal cell line or a primary tissue? [14]

- Cross-Perturbation Prediction: This tests whether a model can predict the effects of a perturbation type it was not explicitly trained on. A powerful example is the Large Perturbation Model (LPM), which can integrate genetic and chemical perturbation data into a unified latent space, allowing it to generalize insights across perturbation modalities [14].

- Extrapolation to Novel Variants: In genomics, generalizability is crucial for predicting the effect of rare or de novo genetic variants that are absent from all training populations, a common challenge in the diagnosis of rare diseases [13] [15].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure fair and informative comparisons, the following experimental protocols are recommended.

Protocol 1: Hold-One-Out Cross-Context Validation

This protocol stringently tests generalizability by systematically withholding all data related to a specific biological context during training.

- Data Partitioning: From a pooled dataset of perturbation experiments (e.g., the LINCS database), identify all unique experimental contexts (e.g., specific cell lines). For each unique context (Ci), create a training set that includes data from all contexts except (Ci).

- Model Training & Prediction: Train the model on the training set. Then, use the trained model to predict perturbation outcomes (e.g., transcriptomic changes) specifically for the held-out context (C_i).

- Performance Quantification: Compare the predictions against the ground truth data for (Ci) using the metrics in Table 1. Repeat this process for every unique context (Ci) to (C_n).

- Analysis: The average performance across all held-out contexts is a strong indicator of the model's ability to generalize to novel biological systems [14].

Protocol 2: Temporal Split for Drug Discovery

This protocol simulates a real-world discovery pipeline by training on past data and testing on newly discovered information.

- Data Sorting: Collect a dataset of known drug-indication associations with their approval or first publication dates.

- Split by Time: Set a cutoff date. All associations established before this date form the training set. Associations confirmed after this date form the testing set.

- Simulated Discovery: Train the model on the pre-cutoff data. Then, task the model with ranking the "new" drugs in the testing set for their respective indications.

- Analysis: Evaluate using metrics like the percentage of known drugs ranked in the top 10 candidates. This tests the model's predictive power in a realistic, forward-looking scenario [11].

Comparative Performance of In Silico Platforms

The following table summarizes the performance of different model types across the key validation metrics, based on recent benchmarking studies.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of In Silico Model Architectures

| Model Type | Predictive Accuracy (e.g., AUPRC) | Robustness to Benchmarking Setup | Generalizability to Unseen Contexts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Association Models (e.g., GWAS) | Moderate (site-specific, confounded by linkage disequilibrium) [13] | High (simple, well-understood statistical framework) | Low (predictions restricted to variants observed in the study population) [13] |

| Encoder-Based Foundation Models (e.g., scGPT, Geneformer) | High (on data similar to training distribution) [14] | Moderate | Moderate (can be limited by signal-to-noise ratio in new contexts) [14] |

| Large Perturbation Model (LPM) | State-of-the-Art (outperformed baselines across diverse settings) [14] | High (seamlessly integrates heterogeneous data) | High (demonstrated accurate cross-context and cross-perturbation prediction) [14] |

| Ensemble Prediction Tools (e.g., REVEL) | Varies by gene/context (e.g., low sensitivity for TERT pathogenic variants) [15] | Moderate (performance depends on the underlying training set) [15] | Low (performance can drop significantly for genes not well-represented in training data) [15] |

Visualization of the Model Validation Workflow

The diagram below illustrates the integrated workflow for rigorously validating an in silico model, tying together the core metrics and experimental protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Databases

Successful validation requires access to high-quality, well-curated data and computational resources.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Databases for Validation Experiments

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| LINCS Database [14] | Perturbation Database | Provides large-scale, heterogeneous perturbation data (genetic, chemical) for training and benchmarking models like LPM. |

| ClinVar [15] | Clinical Variant Database | Serves as a source of "ground truth" pathogenic and benign genetic variants for validating variant effect predictors. |

| CTD & TTD [11] | Drug-Indication Database | Provides known drug-disease associations used as benchmarking ground truth for drug discovery platforms. |

| REVEL, MutPred2, CADD [15] | In Silico Prediction Tool | Established tools used as benchmarks for comparing the performance of new variant effect prediction algorithms. |

| Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDXs) & Organoids [3] | Experimental Model System | Used for cross-validation of AI predictions, providing biological ground truth to confirm computational insights. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster [3] | Computational Resource | Essential for training large models (e.g., LPM, scGPT) and running complex benchmarking simulations at scale. |

The journey toward reliable in silico predictions in biology and drug discovery hinges on a disciplined, multi-faceted approach to validation. As demonstrated by benchmarking studies, models that excel in one narrow area may fail to demonstrate the robustness and generalizability required for real-world application. The integration of biologically meaningful accuracy metrics like AUPRC, stringent cross-context validation protocols, and the use of diverse, high-quality benchmarking datasets is paramount. By adopting this comprehensive framework, researchers can critically evaluate computational tools, foster the development of more powerful and trustworthy models, and ultimately accelerate the translation of in silico predictions into tangible scientific breakthroughs and therapeutic innovations.

The Validation Toolbox: Methodologies and Real-World Applications Across Domains

AI and Machine Learning for Variant Effect Prediction

The challenge of accurately predicting the functional consequences of genetic variants is a central problem in human genetics and precision medicine. For years, this field was dominated by supervised methods trained on limited curated datasets, constraining their generalizability and creating inherent biases. The emergence of sophisticated artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) approaches, particularly deep learning models trained on massive sequence databases, has fundamentally transformed variant effect prediction (VEP). These models leverage the evolutionary information embedded in protein sequences to make highly accurate predictions about variant pathogenicity without relying exclusively on labeled clinical data. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of contemporary AI-driven VEP tools, focusing on their operational principles, benchmark performance across standardized datasets, and utility within rigorous validation frameworks for in silico predictions research.

Comparative Performance of Leading VEP Tools

Quantitative Performance Benchmarking

The accuracy of VEP tools is typically measured using clinical databases like ClinVar and Human Gene Mutation Database (HGMD) for pathogenicity classification, and experimental data from deep mutational scans (DMS) for functional assessment.

Table 1: Clinical Benchmark Performance on Missense Variants

| Tool | Underlying Model | ClinVar ROC-AUC | HGMD/gnomAD ROC-AUC | True Positive Rate (at 5% FPR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESM1b | Protein Language Model | 0.905 [16] | 0.897 [16] | 60% [16] |

| EVE | Variational Autoencoder (MSA-based) | 0.885 [16] | 0.882 [16] | 49% [16] |

| AlphaMissense | Combination of unsupervised (evolutionary, structural) and supervised learning | >90% sensitivity & specificity (overall) [17] | >90% sensitivity & specificity (overall) [17] | Not Reported |

Table 2: Performance on Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs)

| Tool | Sensitivity in Ordered Regions | Sensitivity in Disordered Regions | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaMissense | High [17] | Lower [17] | Reduced accuracy in low-complexity/disordered regions [17] |

| VARITY | High [17] | Lower [17] | Reduced accuracy in low-complexity/disordered regions [17] |

| ESM1b | High [16] | Information Missing | Performance in IDRs requires specific evaluation |

Table 3: Gene-Specific Performance Variations (In Silico Tool Predictions)

| Gene | Variant Type | Reported Sensitivity | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| TERT | Pathogenic | <65% [2] | Inferior sensitivity for pathogenic variants [2] |

| TP53 | Benign | ≤81% [2] | Inferior sensitivity for benign variants [2] |

| BRCA1, BRCA2, ATM | Mixed | Variable [2] | Performance is gene-specific and dependent on training data [2] |

Key Methodological Approaches

The leading VEP tools can be categorized by their underlying AI methodologies:

Protein Language Models (e.g., ESM1b): These models, inspired by natural language processing, are trained on millions of diverse protein sequences to learn the underlying "grammar" and "syntax" of proteins. They function unsupervised, calculating the log-likelihood ratio of a variant amino acid versus the wild-type, effectively measuring how much a mutation disrupts the natural protein sequence [16]. ESM1b, a 650-million-parameter model, can predict effects for all possible missense variants across the human genome, including those in regions with poor multiple sequence alignment coverage [16].

Generative Models with Evolutionary Focus (e.g., EVE): This class of unsupervised models uses deep generative variational autoencoders trained on multiple sequence alignments (MSA) of homologous proteins. They learn the evolutionary distribution of amino acids at each position and flag deviations from this distribution as potentially pathogenic [16].

Composite AI Models (e.g., AlphaMissense): This approach combines unsupervised learning on evolutionary information, population frequency data, and structural context from AlphaFold2 models, with supervised calibration on clinical data to output a probability of pathogenicity [17].

Experimental Protocols for VEP Validation

Standard Clinical Validation Workflow

The gold standard for validating VEP predictions involves benchmarking against expertly curated clinical variant databases.

Diagram 1: Clinical Validation Workflow

Protocol Details:

- Dataset Curation: High-confidence variants are extracted from ClinVar and HGMD. This typically involves excluding variants of uncertain significance (VUS) and those with conflicting interpretations, retaining only those annotated as pathogenic/likely pathogenic or benign/likely benign [16] [17].

- VEP Tool Execution: Scores are obtained for each variant using the tools under evaluation (e.g., via dbNSFP command-line application or direct model inference) [17].

- Performance Calculation: Predictions are compared against clinical annotations. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves are plotted, and the Area Under the Curve (ROC-AUC) is calculated. Sensitivity (true positive rate) at low false positive rates (e.g., 5%) is a critical metric for clinical utility [16].

Experimental Validation via Deep Mutational Scanning

Deep mutational scanning (DMS) provides high-throughput experimental data for functional validation of VEP tools.

Protocol Details:

- Library Construction: Generate a comprehensive library of variant genes for a target protein.

- Functional Selection: Perform experiments where the variant library undergoes functional selection (e.g., for protein stability, enzymatic activity, or binding).

- Sequencing and Enrichment Scoring: Use high-throughput sequencing to quantify the frequency of each variant before and after selection to derive a functional score [16].

- Correlation Analysis: Calculate the correlation between the experimentally derived DMS functional scores and the computationally predicted scores from VEP tools across tens of thousands of variants per gene [16].

Validation for Specialized Protein Regions

Diagram 2: Disordered Region Analysis

Given the reduced accuracy of many tools in intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), specific benchmarking is essential [17].

Protocol Details:

- Region Definition: Use computational predictors (e.g., AIUPred, AlphaFold2 pLDDT scores, metapredict) to classify protein residues as ordered or disordered. Residues with disorder scores >0.5 are typically considered disordered [17].

- Stratified Analysis: Partition clinical benchmark variants (e.g., from ClinVar) based on whether they fall into ordered or disordered regions.

- Differential Performance Calculation: Calculate performance metrics (sensitivity, specificity) separately for the ordered and disordered variant sets. A significant performance drop in disordered regions indicates a limitation of the tool [17].

Table 4: Essential Resources for VEP Research and Validation

| Resource/Solution | Function in VEP Research | Example/Reference |

|---|---|---|

| ClinVar Database | Provides a public archive of clinically annotated variants used as a primary benchmark for pathogenicity prediction accuracy [16] [17]. | https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pub/clinvar/ [17] |

| dbNSFP Database | A comprehensive command-line tool and database that aggregates pre-computed predictions from dozens of VEP tools, facilitating large-scale comparisons [17]. | http://database.liulab.science/dbNSFP [17] |

| AlphaFold2 Models | Provides high-quality predicted protein structures; used as input features for structure-aware VEP tools like AlphaMissense and for analyzing variant impact in a structural context [17]. | https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/ |

| Deep Mutational Scan (DMS) Data | Serves as a source of high-throughput experimental validation data for assessing the functional impact of variants, complementary to clinical annotations [16]. | Individual datasets per gene from publications |

| Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMMs) | Used in specialized protocols to predict microbial interactions in defined environments, demonstrating the extension of in silico modeling to complex biological systems [18]. | Protocols for simulating growth in coculture [18] |

| Artificial Root Exudates (ARE) | A defined chemical medium used in microbial interaction studies to recapitulate a natural environment, enhancing the biological relevance of in silico predictions during experimental validation [18]. | Recipe containing sugars, amino acids, organic acids [18] |

Discussion and Research Implications

Performance Synthesis and Selection Criteria

The benchmarking data reveals that modern AI-driven tools like ESM1b and AlphaMissense achieve high overall accuracy, yet each has distinct strengths and limitations. Protein language models (ESM1b) excel in global benchmarks and can make predictions for residues without homology information [16]. Composite models like AlphaMissense leverage structural insights but show reduced sensitivity in intrinsically disordered regions, a weakness shared by several state-of-the-art tools [17]. This highlights a critical performance gap, as disordered regions constitute ~30% of the human proteome and harbor a significant fraction of disease-associated variants [17].

Furthermore, a 2025 study emphasizes that VEP tool performance can be highly gene-specific. For example, tools showed inferior sensitivity for pathogenic variants in TERT and for benign variants in TP53 [2]. This indicates that the common practice of applying gene-agnostic score thresholds may be suboptimal. Researchers are advised to validate tool performance for their gene(s) of interest where sufficient ground-truth data exists.

The Critical Role of Validation in In Silico Research

The integration of VEP predictions into clinical and research workflows hinges on robust validation. Relying solely on clinical database benchmarks can introduce biases inherent in these datasets. Therefore, a multi-faceted validation strategy is paramount:

- Experimental Corroboration: DMS data provides a valuable, high-throughput functional readout that is independent of clinical ascertainment biases.

- Context-Aware Benchmarking: As demonstrated, performance is not uniform across all genomic and protein contexts. Researchers must validate tools in the specific context of their application, be it for variants in disordered regions, specific genes, or particular protein isoforms [16] [17].

- Cross-referencing Predictions: Using multiple tools with different underlying algorithms can help build consensus and identify high-confidence predictions.

The evolution of VEP tools toward more sophisticated AI architectures promises continued improvements in accuracy. However, this guide underscores that rigorous, context-specific validation remains the cornerstone of reliable in silico prediction in biomedical research.

Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMMs) for Predicting Microbial Interactions

Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GSMMs) have emerged as powerful computational frameworks for predicting metabolic interactions in microbial communities. These models mathematically represent the complete set of metabolic reactions within an organism, enabling researchers to simulate metabolic fluxes and predict interaction outcomes through various computational approaches [19]. As the field progresses from single-strain models to complex community-level simulations, validation of in silico predictions has become a critical research focus. The fundamental challenge lies in the fact that different automated reconstruction tools, while starting from the same genomic data, can generate markedly different model structures and functional predictions [20]. This variability underscores the importance of rigorous comparison and experimental validation to establish confidence in GSMM-based predictions of microbial interactions.

Comparative Analysis of GSMM Reconstruction Tools

Structural and Functional Variations Across Platforms

Automated reconstruction tools employ distinct algorithms and biochemical databases, resulting in GSMMs with different structural characteristics and predictive capabilities. A comparative analysis of three widely used platforms—CarveMe, gapseq, and KBase—reveals significant variations in model properties when applied to the same metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs) from marine bacterial communities [20].

Table 1: Structural Characteristics of Community Metabolic Models from Different Reconstruction Tools

| Reconstruction Approach | Number of Genes | Number of Reactions | Number of Metabolites | Dead-End Metabolites |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CarveMe | Highest | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| gapseq | Lowest | Highest | Highest | Highest |

| KBase | Medium | Medium | Medium | Medium |

| Consensus | High | Highest | Highest | Lowest |

The structural differences between models generated by different tools are substantial. Analysis of Jaccard similarity for reaction sets between tools showed values of only 0.23-0.24, while metabolite similarity was slightly higher at 0.37 [20]. These differences directly impact the predicted metabolic capabilities and interaction profiles of microbial communities.

Consensus Modeling: A Path Toward Improved Prediction

Consensus approaches that integrate models from multiple reconstruction tools have shown promise in addressing the limitations of individual platforms. By combining outputs from CarveMe, gapseq, and KBase, consensus models demonstrate several advantages:

- Enhanced Metabolic Coverage: Consensus models encompass a larger number of reactions and metabolites while reducing dead-end metabolites [20]

- Improved Genomic Evidence: Consensus models incorporate more genes, indicating stronger genomic evidence support for reactions [20]

- Reduced Tool-Specific Bias: Integration of multiple approaches mitigates the database-specific biases inherent in individual tools [20]

Recent developments like GEMsembler further facilitate the construction of consensus models, enabling researchers to systematically compare cross-tool GEMs and build integrated models that outperform even manually curated gold-standard models in certain prediction tasks [21].

Experimental Validation of GSMM Predictions

Integrated Computational-Experimental Workflow

Validating GSMM predictions requires carefully designed experimental protocols that recapitulate key aspects of the microbial environment. A robust protocol for validating predicted interactions between fluorescent Pseudomonas and other bacterial strains illustrates this approach [18].

Diagram: Workflow for In Silico Prediction and In Vitro Validation

This workflow begins with GSMM reconstruction from genome sequences, proceeds through in silico simulation of mono- and co-culture growth, and culminates in experimental validation using defined media that mimics relevant environmental conditions [18].

Key Research Reagents and Experimental Components

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for GSMM Validation Experiments

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial Strains | Pseudomonas sp. 6A2, Paenibacillus sp. 8E4 | Serve as interaction partners in validation assays |

| Defined Growth Media | Artificial Root Exudates (ARE) + MS media | Recapitulates environmental chemical composition |

| Carbon Sources | Glucose, Fructose, Sucrose, Succinic acid | Provide energy and carbon skeletons for growth |

| Amino Acids | L-Alanine, L-Serine, Glycine | Serve as nitrogen sources and metabolic precursors |

| Vitamins & Cofactors | Nicotinic acid, Pyridoxine HCl, Thiamine HCl | Support growth of fastidious microorganisms |

| Detection Methods | Fluorescence scanning, Antibiotic resistance markers | Enable differentiation and quantification of strains |

The composition of artificial root exudates used in validation studies typically includes 16.4 g/L glucose, 16.4 g/L fructose, 8.4 g/L sucrose, 9.2 g/L succinic acid, 8 g/L alanine, 9.6 g/L serine, 3.2 g/L citric acid, and 6.4 g/L sodium lactate [18]. This carefully formulated medium provides the necessary nutrients while maintaining environmental relevance.

Correlation Between Prediction and Validation

Experimental validation of GSMM-predicted interactions has demonstrated moderate but significant correlation with in vitro results. In studies using synthetic bacterial communities (SynComs) under conditions mimicking the rhizosphere environment, GSMM-predicted interaction scores showed statistically significant correlation with experimentally measured outcomes [18]. This correlation, while not perfect, indicates that GSMMs capture fundamental aspects of microbial metabolic interactions while highlighting areas where model refinement is needed.

Advanced Applications and Methodological Developments

Dynamic and Contextualized Modeling Approaches

Static GSMM approaches are increasingly being supplemented by dynamic methods that better capture the temporal dimension of microbial interactions. Tools like MetConSIN (Metabolically Contextualized Species Interaction Networks) infer microbe-metabolite interactions within microbial communities by reformulating dynamic flux balance analysis as a sequence of ordinary differential equations [22]. This approach generates time-dependent interaction networks that evolve as metabolite availability changes, providing more nuanced insights into community dynamics.

Diagram: Dynamic Microbial Community Modeling with MetConSIN

Quantifying Metabolic Interactions in Complex Communities

Advanced analytical frameworks have been developed to quantify the strength and nature of metabolic interactions in microbial communities. Research on the fungus-farming termite gut microbiome introduced several novel parameters for assessing inter-microbial metabolic interactions:

- Pairwise Metabolic Assistance (PMA): Quantifies metabolic benefits between two microbial species

- Community Metabolic Assistance (CMA): Measures metabolic benefits across the entire community

- Pairwise Growth Support Index (PGSI): Assesses mutualistic interactions between community members [23]

Application of these metrics to termite gut communities revealed that microbial species gain up to 15% higher metabolic benefits in multispecies communities compared to pairwise growth, with increased mutualistic interactions in the termite gut environment compared to the fungal comb [23].

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advances, several challenges remain in GSMM-based prediction of microbial interactions. The database dependency of reconstruction tools introduces substantial variation in predicted metabolic capabilities and exchange metabolites [20]. Furthermore, the context-specificity of microbial interactions necessitates careful consideration of environmental parameters when designing validation experiments [18] [22].

Future methodological developments will likely focus on better integration of multi-omics data to create context-specific models, incorporation of machine learning approaches to enhance prediction accuracy, and development of standardized validation frameworks to enable cross-study comparisons [19] [24]. The emerging paradigm of consensus modeling represents a promising approach to overcoming tool-specific biases and generating more robust predictions of microbial interactions [20] [21].

As GSMM methodologies continue to evolve and validation protocols become more standardized, these computational approaches will play an increasingly important role in deciphering the complex metabolic interactions that govern microbial community dynamics across diverse environments from the human gut to agricultural ecosystems.

Ligand-Centric and Target-Centric Approaches in Drug-Target Prediction

The reliable prediction of drug-target interactions (DTIs) is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, crucial for understanding polypharmacology, drug repurposing, and deconvoluting the mechanism of action of phenotypic screening hits [25] [26] [27]. Computational methods for this task are broadly categorized into two paradigms: ligand-centric and target-centric approaches. Ligand-centric methods predict targets based on the similarity of a query molecule to a database of compounds with known target annotations. In contrast, target-centric methods build individual predictive models for each specific protein target [26]. The selection between these strategies involves a critical trade-off between the breadth of target space coverage and the potential for model accuracy on well-characterized targets. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform researchers and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Framework

Core Definitions and Underlying Hypotheses

The two approaches are founded on distinct principles and offer different capabilities:

- Ligand-Centric Approaches operate on the "similarity principle," which posits that structurally similar molecules are likely to bind to similar protein targets [28] [29]. These methods screen a query molecule against a large reference library of target-annotated molecules. The targets of the top K most similar reference compounds are then assigned as predictions for the query. A key advantage is their extensive coverage of the target space, as they can in principle predict any target that has at least one known ligand [25] [26].

- Target-Centric Approaches involve building a dedicated predictive model for each individual protein target. These models are trained using machine learning (e.g., Naïve Bayes, Random Forest), unsupervised learning (e.g., Similarity Ensemble Approach - SEA), or structure-based techniques (e.g., molecular docking) to discriminate between active and inactive compounds for that specific target [26] [30]. Their predictive power is often high for targets with sufficient training data, but they are inherently limited to the much smaller set of targets for which a robust model can be built [26].

Visualizing the Methodological Workflows

The fundamental difference in strategy is illustrated in the workflows below.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The following table summarizes key performance metrics from validation studies for both approaches.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Ligand-Centric and Target-Centric Methods

| Performance Metric | Ligand-Centric Approach | Target-Centric Approach | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Space Coverage | 4,167+ targets (any target with ≥1 known ligand) [25] | Limited to targets with sufficient data for model building (e.g., ≥5 ligands for SEA) [26] | Knowledge-base derived from ChEMBL [25] [26]. |

| Average Precision | 0.348 (on clinical drugs) [25] | F1-score > 0.80 achievable on curated target sets [30] | Validation on 745 approved drugs [25] vs. 253 human targets [30]. |

| Average Recall | 0.423 (on clinical drugs) [25] | Varies significantly by target and algorithm [30] | Validation on 745 approved drugs [25]. |

| Typical Use Case | Phenotypic screening hit deconvolution, maximum target exploration [25] [26] | Focused screening on a predefined set of well-characterized targets [26] [30] | |

| Reliability Scoring | Similarity to reference ligands can serve as a confidence score [25] [29] | Model-derived probabilities or scores (e.g., p-values, E-values) [26] |

Analysis of Performance Trade-offs

The data reveals a clear trade-off. Ligand-centric methods provide superior coverage, which is vital for discovering interactions with novel or poorly characterized targets. However, this comes at the cost of moderate precision, which is influenced by factors like the choice of molecular fingerprint and similarity threshold [29]. In contrast, target-centric methods can achieve high accuracy and provide robust statistical confidence measures, but only for a fraction of the proteome [26] [30]. It is also noteworthy that predicting targets for clinical drugs is particularly challenging, leading to significant performance variability across different query molecules for both approaches [25] [26].

Experimental Protocols for Validation

To ensure the reliability of predictions, rigorous validation protocols are essential. The following workflows detail standard methodologies for benchmarking each approach.

Ligand-Centric Validation Protocol

The typical protocol for validating a ligand-centric prediction method involves a leave-one-out cross-validation on a large bioactivity database.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Ligand-Centric Validation

| Research Reagent | Function in Validation | Example Source |

|---|---|---|

| Bioactivity Database | Serves as the reference library and source of ground truth. | ChEMBL [25] [29], BindingDB [29] |

| Molecular Fingerprints | Encode chemical structure for similarity calculation. | ECFP4, FCFP4, AtomPair, MACCS [29] [30] |

| Similarity Metric | Quantifies structural relationship between molecules. | Tanimoto Coefficient [29] |

| Performance Metrics | Measure prediction accuracy. | Precision, Recall, Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) [25] |

Target-Centric Validation Protocol

Validating target-centric models involves a more traditional machine learning setup, often with a hold-out test set.

Table 3: Key Reagents for Target-Centric Validation

| Research Reagent | Function in Validation | Example Source |

|---|---|---|

| Curated Target Set | Defines the proteins for which models are built. | Human proteins from ChEMBL [30] |

| Active/Inactive Compounds | Provides labeled data for model training and testing. | ChEMBL (e.g., IC50 ≤ 10 µM = Active) [30] |

| Machine Learning Algorithm | The core engine for building the predictive model. | Random Forest, Naïve Bayes, Neural Networks [31] [30] |

| Molecular Descriptors | Numeric representation of chemical structures. | ECFP, MACCS, Graph Representations [31] [30] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation and validation of drug-target prediction methods rely on several key resources.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Drug-Target Prediction

| Category | Item | Specific Function |

|---|---|---|

| Bioactivity Databases | ChEMBL | Manually curated database of bioactive molecules and their targets, essential for building reference libraries and training sets [25] [30]. |

| BindingDB | Public database of measured binding affinities, useful for supplementing interaction data [29]. | |

| Software & Tools | RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit for computing fingerprints (ECFP, AtomPair), similarity searches, and general molecular informatics [29]. |

| SwissTargetPrediction | Popular web server for ligand-centric target prediction [28] [29]. | |

| Molecular Descriptors | ECFP4 / FCFP4 | Circular fingerprints that capture molecular topology and features; widely used and high-performing [29]. |

| MACCS Keys | A set of 166 predefined structural fragments used as a binary fingerprint [29] [30]. | |

| Validation Metrics | Precision & Recall | Metrics to balance the trade-off between false positives and false negatives in prediction lists [25] [30]. |

| Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) | A robust metric for binary classification that is informative even on imbalanced datasets [25]. |

Ligand-centric and target-centric approaches offer complementary strengths for predicting drug-target interactions. The choice between them should be guided by the specific research objective: ligand-centric methods are superior for exploratory research, such as target deconvolution from phenotypic screens, where maximizing the coverage of potential targets is critical. Conversely, target-centric methods are more suitable for focused investigations on a predefined set of well-characterized targets, where higher predictive accuracy for those specific proteins is required. Emerging strategies, including consensus methods that combine multiple models [30] and advanced multitask deep learning frameworks like DeepDTAGen [31], are pushing the boundaries by integrating the strengths of both paradigms. Ultimately, a pragmatic approach that understands the context of use, the limitations of each method, and the critical importance of rigorous validation will be most effective in leveraging these powerful in silico tools for drug discovery.

The integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and bioinformatics into oncology has revolutionized drug discovery and personalized therapy design [3]. In silico models, which rely on computational simulations to predict tumor behavior and therapeutic outcomes, have become central to preclinical research [3]. However, the predictive accuracy of these computational frameworks hinges entirely on their validation against robust biological systems. Advanced experimental models including patient-derived xenografts (PDXs), patient-derived organoids (PDOs), and tumoroids serve as essential platforms for this cross-validation, creating a critical bridge between digital predictions and clinical application.

Each model system offers distinct advantages and limitations in recapitulating human tumor biology. PDX models, which involve implanting human tumor tissue into immunocompromised mice, retain much of the original histological architecture and cellular heterogeneity [32]. Organoid and tumoroid models—three-dimensional (3D) in vitro cultures derived from patient tumors or PDX tissue—preserve key architectural and molecular features of the original tumor while offering greater scalability [33] [34]. Understanding the relative strengths, validation methodologies, and appropriate applications of each platform is fundamental to establishing a reliable framework for validating in silico predictions in oncology research.

Comparative Performance of PDX and Organoid/Tumoroid Models

Predictive Accuracy and Clinical Concordance

A 2025 systematic review and meta-analysis directly compared the predictive performance of PDX and PDO models for anti-cancer therapy response, providing the most comprehensive quantitative comparison to date [32]. The analysis encompassed 411 patient-model pairs (267 PDX, 144 PDO) from solid tumors treated with identical anti-cancer agents as the matched patient [32].

Table 1: Overall Predictive Performance of PDX vs. PDO Models

| Performance Metric | PDX Models | PDO Models | Overall Combined |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Concordance | Comparable to PDO | Comparable to PDX | 70% |

| Sensitivity | Comparable | Comparable | Not Specified |

| Specificity | Comparable | Comparable | Not Specified |

| Positive Predictive Value | Comparable | Comparable | Not Specified |

| Negative Predictive Value | Comparable | Comparable | Not Specified |

| Association with Patient Survival | Only in low-bias pairs | Prolonged PFS when models responded | Consistent when bias controlled |

The analysis revealed no significant differences in predictive accuracy between PDX and PDO models across all measured parameters [32]. This remarkable equivalence suggests that both platforms perform similarly in predicting matched-patient responses, though each carries distinct practical and ethical considerations.

Technical and Practical Considerations

Beyond predictive accuracy, selection of an appropriate model system requires careful consideration of technical feasibility, scalability, and specific research requirements.

Table 2: Practical and Technical Comparison of Oncology Model Systems

| Characteristic | PDX Models | PDO/Tumoroid Models | PDX-Derived Tumoroids (PDXTs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| In vivo/In vitro | In vivo (mice) | In vitro | In vitro |

| Tumor Microenvironment | Retains human stroma interacting with mouse host [32] | Limited TME; requires co-culture for immune components [33] | Varies based on derivation method |

| Throughput | Low to moderate | High [33] | High [35] |

| Timeline | Months | Weeks [36] | Weeks [35] |

| Cost | High [32] | Cost-effective [32] | Moderate to high |

| Ethical Considerations | Significant animal use [32] | Reduced animal use [32] | Reduced animal use (after initial PDX) |

| Success Rates | Established technology | 77% for metastatic CRC PDXTs [35] | Varies by cancer type |

| Immune System | Lacks adaptive human immunity [32] | Can be co-cultured with immune cells [34] | Can be co-cultured with immune cells |

| Stromal Components | Retained, though mouse-specific evolution occurs [32] | Limited; requires engineering [33] | Limited without engineering |

The emergence of PDX-derived tumoroids (PDXTs) represents a synergistic approach, leveraging the established biological fidelity of PDX models with the scalability of in vitro systems. The XENTURION resource, a large-scale collection of 128 matched PDX-PDXT pairs from metastatic colorectal cancer patients, demonstrates how these platforms can be complementary [35].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Establishing and Validating Matched Model Systems

The XENTURION project provides a robust methodological framework for establishing and validating matched PDX and tumoroid models, with specific application to metastatic colorectal cancer (CRC) [35]. This protocol ensures molecular fidelity between models and enables rigorous cross-validation.

Tumoroid Derivation Protocol:

- Source Material: Use freshly explanted PDX tumors as the primary source, which demonstrates higher success rates (80%) compared to frozen PDX material (50%) or direct patient specimens (38%) [35].

- Culture Conditions: Standardize culture conditions using a minimal medium containing EGF (20 ng/mL) as the sole exogenous growth factor to minimize alterations in tumor biology and growth dependencies [35].

- Expansion and Validation: Define "early-stage" tumoroids as cultures expanded to a minimum of 200,000 viable cells for cryopreservation, typically after three rounds of cell splitting. Validate models through a minimum of three freeze-thaw cycles with DNA fingerprinting and microbiological testing after each cycle [35].

Molecular Fidelity Assessment:

- Perform systematic comparison between paired PDXs and PDXTs using:

- Mutational profiling to verify retention of driver mutations

- Gene copy number analysis to assess genomic stability

- Transcriptomic profiling to evaluate conservation of gene expression patterns

- In the XENTURION resource, tumoroids retained extensive molecular fidelity with parental PDXs across all these dimensions [35].

Model Establishment Workflow: This diagram illustrates the optimized pathway for establishing validated PDX-tumoroid model pairs, highlighting critical success factors and validation checkpoints.

Drug Response Validation Protocols

Validating model predictive capacity through drug response testing represents a critical step in establishing clinical relevance.

Standardized Drug Screening in Tumoroids:

- Model Selection: Utilize a panel of well-characterized models representing relevant molecular subtypes and clinical backgrounds [35].

- Treatment Conditions: Expose tumoroids to clinically relevant dose ranges of standard-of-care agents (e.g., 5-fluorouracil, irinotecan, oxaliplatin for CRC) or targeted therapies (e.g., cetuximab for EGFR-wild type CRC) [34] [35].

- Response Assessment: Quantify response using cell viability assays (e.g., ATP-based luminescence) and calculate IC₅₀ values or similar metrics after 5-7 days of drug exposure [35].

- Clinical Correlation: Compare model response to actual patient clinical outcomes, including progression-free survival and overall treatment response [32] [34].

In Vivo Cross-Validation:

- Translate Hits: Advance compounds showing efficacy in tumoroid screens to PDX models for in vivo validation [35].

- Treatment Regimen: Administer therapeutics to PDX-bearing mice using human-equivalent dosing schedules [35].

- Endpoint Analysis: Monitor tumor growth dynamics and perform endpoint analyses including histopathology and molecular profiling of treated versus control tumors [35].

For colorectal cancer specifically, multiple studies have demonstrated significant correlations between PDO sensitivity to standard chemotherapies (5-fluorouracil, irinotecan, oxaliplatin) and actual patient treatment responses, with correlation coefficients ranging from 0.58-0.61 [34]. Patients whose matched PDOs responded to therapy showed significantly prolonged progression-free survival, reinforcing the clinical predictive value of these platforms [32] [34].

Integration with In Silico Prediction Platforms

Validation Frameworks for AI-Driven Predictions

The convergence of experimental models and computational approaches creates a powerful paradigm for accelerating oncology drug development. Crown Bioscience exemplifies this integration by validating AI-driven in silico models through rigorous cross-comparison with experimental data from PDXs, organoids, and tumoroids [3].

Key Validation Strategies:

- Cross-validation with Experimental Models: AI predictions of drug efficacy are directly tested against responses observed in PDX models carrying identical genetic mutations [3].

- Longitudinal Data Integration: Time-series data from experimental studies (e.g., tumor growth trajectories in PDX models) are incorporated to refine and train AI algorithms for improved accuracy [3].

- Multi-omics Data Fusion: Genomic, proteomic, and transcriptomic data from model systems are integrated to enhance the predictive power of in silico frameworks [3].

This integrated validation approach ensures that computational predictions reflect real-world biological complexity, addressing a significant challenge in AI-driven drug discovery.

Advanced Applications: From Predictive Modeling to Digital Twins

The combination of high-quality experimental data from advanced models with computational approaches enables several transformative applications:

- Drug Combination Optimization: AI models analyze PDX and organoid response data to predict synergistic interactions between therapeutic agents, prioritizing the most promising combinations for experimental testing [3].

- Patient Stratification: Machine learning algorithms cluster patients based on genetic and molecular profiles validated against preclinical models, enabling precision medicine approaches [3].

- Digital Twin Development: The future direction involves creating digital twins of patients using AI and bioinformatics, enabled by high-fidelity experimental data from PDX and organoid platforms [3].

Integrated Validation Framework: This diagram shows the continuous feedback loop between experimental models and computational platforms that enables refinement of predictive algorithms.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful implementation of cross-validation studies requires specific reagents, platforms, and technical capabilities. The following table details essential components for working with advanced cancer models.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Advanced Cancer Model Research

| Category | Specific Product/Platform | Key Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Culture Systems | Defined biomaterials/engineered scaffolds [33] | Provide tunable 3D microenvironment for organoid growth | Enable spatial guidance and reduce growth factor dependence |

| Matrigel-free culture systems [36] | Support 3D growth without drug diffusion issues | Eliminate imaging artifacts and improve consistency | |

| Minimal EGF media [35] | Sustain tumoroid proliferation with minimal exogenous factors | Prevents alteration of native biology; 20 ng/mL concentration used in XENTURION | |

| Characterization Tools | DNA fingerprinting [35] | Verify model identity and parentage | Critical for quality control throughout model establishment |

| Multi-omics integration (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) [3] | Assess molecular fidelity to original tumors | Enables comprehensive comparison between models and patient tumors | |

| Advanced imaging (confocal/multiphoton microscopy) [3] | Visualize tumor microenvironment and drug penetration | AI-augmented analysis extracts critical features from imaging data | |

| Specialized Platforms | Microfluidic/Organ-on-a-chip systems [33] | Provide fine control of culture microenvironment | Reduces growth factor requirements; enables precise gradient control |

| High-throughput screening systems [36] | Enable rapid drug testing across multiple models | Assay-ready formats allow study initiation within ~10 days | |

| 3D bioprinting technology [33] | Fabricate customized hydrogel devices for organoid growth | Mitigates organoid necrosis and supports stable growth |

The cross-validation of advanced experimental models—PDXs, organoids, and tumoroids—represents a cornerstone of robust preclinical oncology research, particularly within the context of validating in silico predictions. The quantitative evidence demonstrates equivalent predictive accuracy between PDX and PDO platforms, with organoids offering practical advantages in throughput and scalability while PDX models provide important in vivo context.

The emerging paradigm of using matched model systems, such as the PDX-tumoroid pairs in the XENTURION resource, creates a powerful framework for sequential validation—from in silico prediction to in vitro screening to in vivo confirmation. This integrated approach maximizes the strengths of each platform while mitigating their individual limitations. Furthermore, the continuous feedback loop between experimental models and computational algorithms creates an iterative refinement process that enhances the predictive power of both methodologies.

As these technologies continue to evolve—through standardization of protocols, enhancement of tumor microenvironment complexity, and integration with multi-omics data—their role in validating in silico predictions and accelerating therapeutic development will only expand. This synergistic relationship between computational and experimental approaches promises to enhance the efficiency and success rate of oncology drug development, ultimately advancing more effective therapies to patients.

Multi-Omics Data Fusion for Enhanced Predictive Power

The profound complexity of cancer biology, driven by diverse genetic, environmental, and molecular factors, necessitates a move beyond single-modality analysis to achieve meaningful predictive insights for clinical applications. Multi-omics data fusion represents a transformative approach in precision medicine, enabling a holistic understanding of tumor heterogeneity by integrating complementary data types spanning genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, and metabolomics [37] [38] [39]. While technological advances have made the generation of such high-dimensional, high-throughput multi-scale biomedical data increasingly feasible, the biomedical research community faces significant challenges in effectively integrating these disparate modalities to unravel the biological processes involved in multifactorial diseases [37]. The central thesis of this guide is that robust validation of in silico predictions through rigorous experimental frameworks is the critical linchpin for translating computational multi-omics models into clinically actionable knowledge, ultimately enhancing diagnostic accuracy, prognostic stratification, and therapeutic decision-making [3].

Relying on a single data modality provides only a partial and often fragmented view of the intricate mechanisms of cancer, potentially missing critical biomarkers and therapeutic opportunities [38]. The heterogeneity of cancer, reflected in its diverse subtypes and molecular profiles, requires an integrated approach. Multimodal data fusion enhances our understanding of cancer and paves the way for precision medicine by capturing synergistic signals that identify both intra- and inter-patient heterogeneity, which is critical for clinical predictions [37]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the computational frameworks, experimental protocols, and reagent toolkits essential for validating in silico multi-omics predictions, addressing the pressing need for clinical feasibility and analytical robustness in the age of AI-driven oncology.

Comparative Analysis of Multi-Omics Data Fusion Platforms and Methodologies

The landscape of tools for multi-omics data fusion is diverse, ranging from specialized bioinformatics software to extensive AI-driven platforms and privacy-preserving computational infrastructures. The following analysis objectively compares the performance, capabilities, and optimal use cases of leading solutions.

Bioinformatics Tools for Multi-Omics Analysis

Table 1: Key Bioinformatics Tools for Multi-Omics Data Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Strengths | Limitations | Integration Capabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bioconductor | Omics data analysis using R packages | Highly flexible with extensive package ecosystem; Strong statistical and visualization support [40] | Steep learning curve requires R programming expertise [40] [41] | Excellent with statistical workflows and genomic data sources |

| Galaxy | Web-based workflow management | User-friendly, drag-and-drop interface; No programming skills needed; Excellent reproducibility [40] [41] | Limited advanced customization; Performance depends on server load [40] | Broad tool integration with cloud-based collaboration |

| Cytoscape | Biological network visualization and analysis | Excellent visualization for complex molecular interaction networks; Highly extensible with plugins [40] [41] | Steep learning curve; Resource-intensive with large datasets [40] [41] | Strong integration with external databases (BioGRID, STRING) |

| BLAST | Sequence similarity search | Widely accepted gold standard; Extensive database support; Free and accessible [40] [41] | Limited to sequence analysis; Not optimized for large-scale integrative omics [41] | Foundation for genomic and transcriptomic component analysis |

Specialized Frameworks for Multi-Omics Integration and Validation

Beyond general-purpose bioinformatics tools, specialized computational frameworks have emerged specifically designed to address the challenges of multi-omics data fusion and validation.

Table 2: Specialized Multi-Omics Fusion and Validation Frameworks

| Framework/Platform | Core Methodology | Validation Approach | Key Performance Metrics | Data Modalities Supported |

|---|---|---|---|---|