Comparative Analysis of Homology Modeling Tools: A Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of homology modeling tools, a critical computational technique for predicting protein three-dimensional structures.

Comparative Analysis of Homology Modeling Tools: A Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of homology modeling tools, a critical computational technique for predicting protein three-dimensional structures. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles, methodological workflows, and practical applications in drug discovery. The content explores common challenges and optimization strategies, delivers a rigorous validation framework, and presents a comparative analysis of popular software like MODELLER, SWISS-MODEL, I-TASSER, Rosetta, and Phyre2. By synthesizing current methodologies and performance metrics, this guide serves as a vital resource for selecting the right tool and generating reliable protein models to accelerate structural biology and therapeutic design.

Understanding Homology Modeling: Core Principles and Its Role in Modern Biology

What is Homology Modeling? Defining Comparative Modeling and Its Underlying Principle

Homology modeling, also known as comparative modeling, represents a cornerstone technique in structural bioinformatics for predicting the three-dimensional structure of proteins using experimentally determined structures of related homologs. This comprehensive review examines the fundamental principles, methodological workflows, accuracy determinants, and performance benchmarks of predominant homology modeling tools. Within the broader context of protein structure prediction research, we objectively evaluate contemporary software solutions including MODELLER, SWISS-MODEL, I-TASSER, Phyre2, and the emerging Prostruc platform, synthesizing experimental data from Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments and independent benchmarking studies. By integrating quantitative performance metrics with detailed methodological protocols, this analysis provides researchers and drug development professionals with evidence-based guidance for tool selection while highlighting evolving trends in machine learning integration and collective intelligence initiatives that are reshaping the homology modeling landscape.

Definition and Core Principles

Homology modeling, alternatively termed comparative modeling, refers to a computational method for constructing atomic-resolution models of target proteins based on their amino acid sequences and experimental three-dimensional structures of related homologous proteins (templates) [1]. This technique operates on two fundamental biological principles: (1) protein tertiary structure is evolutionarily more conserved than amino acid sequence, and (2) evolutionarily related proteins typically share similar three-dimensional architectures [1] [2]. The observation that protein structures are more conserved than DNA sequences underpins the approach, as detectable sequence similarity generally implies significant structural similarity [1].

The practical applicability of homology modeling stems from the widening gap between sequenced genes and experimentally determined structures. While genomic sequencing advances have produced over 85 million protein sequences in UniProtKB/TrEMBL, the Protein Data Bank (PDB) contained approximately 130,000 experimental structures as of 2017 [2]. This substantial disparity has established homology modeling as an indispensable tool for generating structural hypotheses when experimental determination through X-ray crystallography, NMR spectroscopy, or cryo-electron microscopy proves impractical due to technical or resource constraints [1] [3].

Theoretical Foundation and Evolutionary Basis

The theoretical foundation of homology modeling rests on established observations that three-dimensional protein structure exhibits greater evolutionary conservation than would be expected based solely on sequence conservation [1]. Seminal research has demonstrated that proteins sharing statistically significant sequence similarity typically maintain similar backbone folds even after extensive sequence divergence [4]. Exceptions exist where strategically placed mutations can induce complete fold changes, but such dramatic structural rearrangements rarely occur in natural evolution due to functional constraints and folding requirements [1].

The relationship between sequence identity and structural similarity follows predictable patterns that inform modeling reliability. Comparative modeling generally produces high-quality models when using templates with global sequence identity ≥30%, but model quality deteriorates rapidly below this "twilight zone" threshold [2] [5]. Studies specifically evaluating membrane proteins indicate that homology modeling remains equally applicable to this class, with acceptable models (Cα-RMSD ≤2Å in transmembrane regions) achievable at template sequence identities of 30% or higher when accurate alignments are employed [5].

The Homology Modeling Workflow

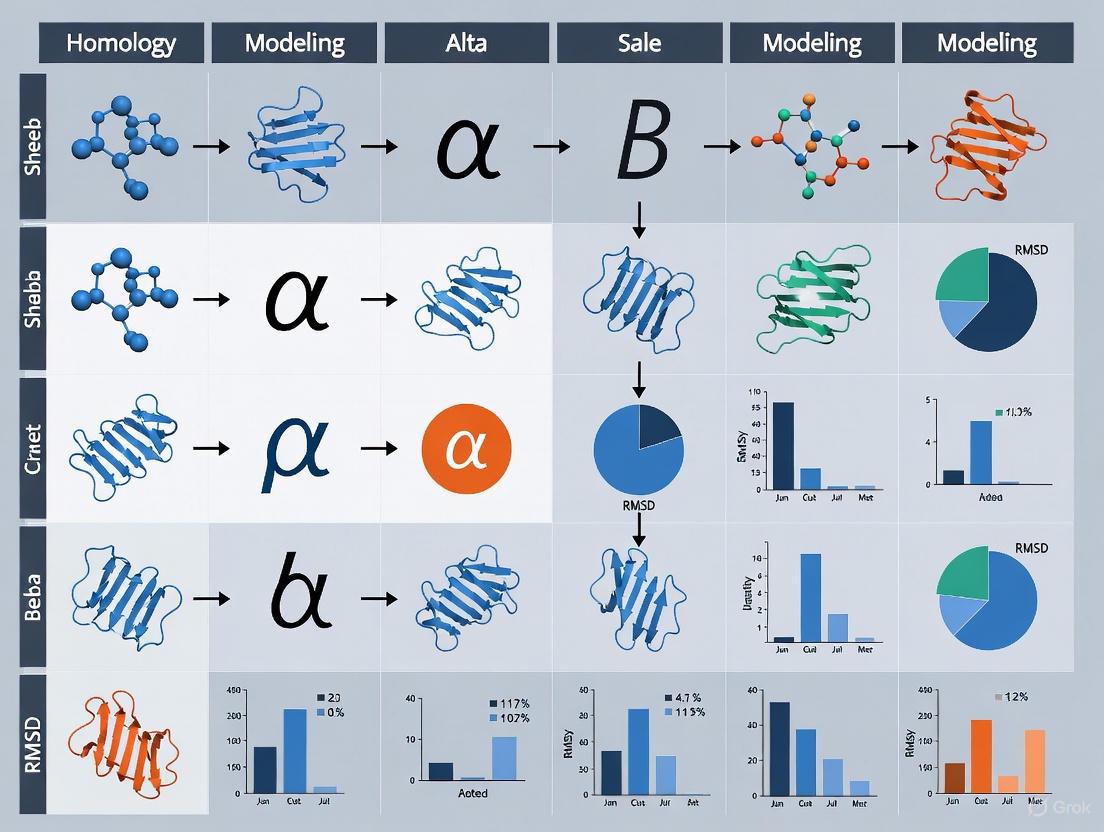

The homology modeling process comprises sequential steps that transform a target sequence into a refined three-dimensional model. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow and iterative refinement nature of this process:

Figure 1: Homology modeling workflow demonstrating sequential steps and iterative refinement potential.

Template Identification and Selection

The initial critical step involves identifying appropriate template structures through database searches against repositories like the Protein Data Bank [1] [6]. Template selection methods vary in sophistication:

Sequence-based methods: Tools like BLAST perform serial pairwise alignments, prioritizing speed but potentially sacrificing alignment quality [1]. Global sequence identity has traditionally served as the primary selection criterion, with E-values guiding reliability assessment [1] [2].

Profile-based methods: PSI-BLAST employs position-specific scoring matrices (PSSMs) to capture evolutionary information, demonstrating approximately three times greater sensitivity than standard BLAST [2]. These methods iteratively update scoring matrices to identify distant homologs.

Hidden Markov Models (HMMs): Advanced profile forms like HMMER and HHsearch incorporate insertion/deletion patterns and predicted secondary structure information, extending template identification into the twilight zone of low sequence identity [3] [2].

Protein threading: Also known as fold recognition, this technique aligns target sequences against fold templates from known structures, evaluating secondary structure matches, residue contacts, and profile-profile alignment scores [1] [2].

When multiple candidate templates exist, selection prioritizes structures with highest sequence similarity to target, consistent biological function, similar predicted and observed secondary structures, and comprehensive coverage of the target sequence [1]. Additional considerations include experimental resolution (preferring higher resolution regardless of physiological conditions) and structural completeness, particularly in active sites or regions of interest [2] [7].

Target-Template Alignment

Sequence alignment represents the most critical determinant of final model quality, as errors introduced at this stage propagate through subsequent modeling steps [1] [4]. Alignment methods have evolved substantially:

Pairwise alignment: Initial alignments generated by database search tools prioritize speed over precision [1].

Profile-profile alignment: Systematically compares target and template sequence profiles, reducing noise from sequence drift in nonessential regions [1] [5]. These methods demonstrate particular value for distantly related proteins.

Structure-guided alignment: Incorporates structural information to improve alignment accuracy, especially in multiple template modeling and threading protocols [2].

Evaluation studies indicate that profile-based alignments consistently produce superior models compared to sequence-based approaches, with HMM-based alignments typically outperforming PSSM-based methods [2] [5]. For membrane proteins, profile-to-profile alignment methods achieve highest accuracy, particularly when incorporating weights derived from secondary structure predictions [5].

Model Construction Techniques

Model generation employs three principal methodologies to convert alignments into three-dimensional coordinates:

Fragment assembly: Original homology modeling approach assembling complete models from conserved structural fragments identified in closely related solved structures, with variable regions typically constructed using protein fragment libraries [1].

Segment matching: Divides target into short segments individually matched to fitted templates from structural databases, with selection based on sequence similarity, alpha carbon coordinate comparisons, and steric conflict predictions [1].

Spatial restraint satisfaction: Most prevalent contemporary method inspired by NMR structure calculation, employing geometrical criteria derived from target-template alignments converted to probability density functions for global optimization [1]. MODELLER represents a widely implemented example using this approach [2] [8].

Loop Modeling and Side-Chain Placement

Structurally variable regions, particularly loops, present special challenges in homology modeling. Loop modeling approaches include:

Knowledge-based methods: Search high-resolution fragment libraries (PDB-derived or from domain resources like CATH/SCOP) for segments fitting specific backbone regions [2]. Effectiveness decreases with loop length exceeding 7 residues due to exponential conformation increases [2].

Conformational sampling: Constructs loops by searching conformational space guided by energy functions incorporating stereochemical, distance, and steric constraints [2].

Hybrid methods: Combine knowledge-based and physics-based energy functions to maximize accuracy by simulating correct environmental conditions [2].

Side-chain modeling employs strategies including dead-end elimination, Monte Carlo sampling, and simulated annealing to predict the most probable rotamer conformations based on local backbone geometry using rotamer libraries like SCWRL [2].

Model Refinement and Validation

Final optimization stages enhance model quality through:

Energy minimization: Refines atomic positions to achieve near-native conformation using molecular mechanics force fields [8] [9].

Validation: Assesses model quality through geometric and energetic criteria:

- Ramachandran plots: Evaluate backbone dihedral angles against permitted regions [8] [7].

- QMEANDisCo: Estimates global model accuracy [6].

- PROCHECK: Analyzes torsion angles, surface area, bond angles, and atomic distances [8].

- ERRAT: Verifies atomic interaction patterns against high-resolution structures [8].

The experimental workflow for homology modeling relies on specialized computational tools and databases. The following table summarizes essential resources:

Table 1: Essential Research Resources for Homology Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [6], SCOP [10], CATH [2] | Repository of experimental protein structures | Template identification, fold recognition |

| Sequence Search Tools | BLAST [1], PSI-BLAST [2], HHblits [3], JackHMMER [3] | Identify homologous sequences/structures | Template selection, sequence profiling |

| Alignment Algorithms | ClustalW/O [3], MUSCLE [3], T-Coffee [5], ProbCons [5] | Generate sequence alignments | Target-template alignment optimization |

| Modeling Servers | MODELLER [1] [8], SWISS-MODEL [3] [6], I-TASSER [8], Phyre2 [6] | Generate 3D structural models | Automated model construction |

| Quality Assessment | PROCHECK [8], QMEANDisCo [6], ERRAT [8], MolProbity | Validate model geometry/stability | Model verification, refinement guidance |

| Specialized Tools | MODELLER Loop Refinement [1], SCWRL4 [2], Molsoft ICM | Handle challenging regions | Loop modeling, side-chain placement |

Performance Comparison of Homology Modeling Tools

Benchmarking Methodologies

Objective evaluation of homology modeling tools primarily occurs through the Critical Assessment of Protein Structure Prediction (CASP) experiments, biennial community-wide assessments that rigorously test prediction methods using unpublished structures [3] [4]. Additional benchmarking resources include:

- CAMEO: Continuous automated model evaluation with frequent updates [10].

- HMDM: Homology Models Dataset for Model Quality Assessment specifically designed to evaluate performance with high-quality homology models [10].

- 3DRobot and QUARK: Alternative decoy sets for assessing model quality assessment methods [10].

Standard evaluation metrics include:

- Global Distance Test (GDT_TS): Measures structural similarity at different distance thresholds [10].

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Quantifies atomic position deviations, particularly for backbone atoms [1].

- lDDT: Local Distance Difference Test assessing local quality without superposition [10].

- QMEAN: Composite quality estimation scoring function [6].

Quantitative Performance Analysis

The following table synthesizes performance data from CASP experiments and independent benchmarking studies:

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Homology Modeling Tools

| Modeling Tool | Methodology | Best Application Scope | Accuracy (Sequence Identity >30%) | Runtime Efficiency | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MODELLER [1] [8] | Satisfaction of spatial restraints | High-identity templates, single domains | ~1-2 Å Cα-RMSD (70% identity) [1] | Moderate | Declining accuracy with lower identity |

| SWISS-MODEL [3] [6] | Automated homology modeling | Routine modeling, non-expert users | Competitive with MODELLER for high-identity cases | Fast | Limited manual intervention |

| I-TASSER [8] | Hierarchical threading/assembly | Difficult targets, fold recognition | TM-score >0.7 in 70% of cases [8] | Slow | High computational demand |

| Phyre2 [6] [9] | Homology/threading hybrid | Remote homology detection | ~90% success rate for core prediction [9] | Moderate | Web server dependency |

| Prostruc [6] | Automated pipeline with ProMod3 | User-friendly automation, cloud-based | Comparable to SWISS-MODEL in benchmarking [6] | Fast | Limited customization |

| RaptorX [1] | Profile-profile alignment | Distantly related templates | Superior below 20% sequence identity [1] | Moderate | Specialized for difficult cases |

Performance analysis reveals that model quality exhibits strong dependence on target-template sequence identity. Studies demonstrate that models typically achieve ~1-2 Å Cα-RMSD at 70% sequence identity, deteriorating to 2-4 Å at 25% identity [1]. Error distribution is non-uniform, with significantly higher inaccuracies in loop regions where target and template sequences may differ completely [1]. Model assessment indicates that the most successful contemporary approaches employ consensus strategies, combining multiple templates and hybridizing fold recognition with de novo modeling components [4].

Practical Performance in Research Applications

In practical drug discovery contexts, homology modeling demonstrates substantial value when templates share minimum 35% sequence homology with target proteins [7]. Successful applications include:

- Antifungal drug development: Orotomide class inhibitors targeting dihydroorotate dehydrogenase [7].

- GPCR ligand discovery: Modeling flavors binding mechanisms for GPCRs with unresolved structures [7].

- Antimalarial inhibitor prediction: XED force field application to predict binding sites in homology models [7].

Performance benchmarking using the HMDM dataset indicates that modern model quality assessment methods incorporating deep learning outperform traditional selection based solely on template sequence identity, particularly for high-accuracy homology models [10].

Methodological Protocols

Standard Homology Modeling Protocol

A robust experimental protocol for homology modeling incorporates these critical steps:

Target Preparation

- Obtain target amino acid sequence in FASTA format

- Define domain boundaries using tools like Pfam or InterPro

- For large proteins, consider modeling domains separately

Template Identification

- Perform BLASTP search against PDB database

- Set E-value threshold to 0.01 and minimum identity to 20-30% [6]

- For difficult targets, employ iterative PSI-BLAST or HMM-based searches (HHblits, JackHMMER) [3]

- Select templates based on sequence identity, coverage, resolution (<2.5Å preferred), and biological relevance

Sequence Alignment

- Generate multiple sequence alignment using Clustal Omega, MUSCLE, or T-Coffee

- Manually inspect and adjust alignments in functionally important regions

- Verify conserved motif alignment, particularly around active sites

Model Building

- Generate multiple models (typically 5-20) using selected software

- For MODELLER: Apply satisfaction of spatial restraints approach

- For multiple templates: Use composite approaches to integrate structural information

Loop Modeling

- Identify disordered regions or gaps in alignment

- Apply knowledge-based methods for short loops (<8 residues)

- Use conformational sampling with energy evaluation for longer loops

Side-Chain Optimization

- Employ rotamer libraries (SCWRL) to predict side-chain conformations

- Refine using molecular mechanics minimization

Model Validation

- Analyze Ramachandran plots using PROCHECK or MolProbity

- Verify steric clashes and bond geometry

- Assess energy profiles using QMEAN or ProSA-web

- Compare with experimental data if available (mutagenesis, spectroscopy)

Advanced Protocol for Membrane Proteins

Membrane proteins require specialized approaches due to environmental differences:

Template Selection

- Prioritize membrane protein templates with similar topology

- Consider orientation in membrane using PDB_TM or OPM databases

Alignment Optimization

- Implement profile-to-profile alignment methods

- Incorporate secondary structure predictions as weights in scoring

- Use membrane-specific substitution matrices in transmembrane regions

Model Refinement

- Apply membrane-specific energy functions during minimization

- Include implicit membrane models in molecular dynamics refinement

- Validate using membrane protein-specific geometric criteria

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The homology modeling landscape is rapidly evolving through several transformative developments:

Machine Learning and Artificial Intelligence

Deep learning approaches have revolutionized protein structure prediction, with unprecedented improvements in accuracy [3]. Key advancements include:

- Contact map prediction: Neural networks accurately predict residue-residue contacts, providing critical distance constraints for model construction [3].

- End-to-end structure prediction: AlphaFold represents a paradigm shift, achieving accuracy competitive with experimental methods in many cases [9].

- Quality assessment: Deep learning-based MQA methods consistently outperform traditional statistical potentials, particularly for selecting optimal models from high-accuracy candidates [10].

Collective Intelligence Initiatives

Large-scale collaborative efforts have accelerated methodology development:

- CASP experiments: Biennial assessments drive innovation and establish performance benchmarks [3] [4].

- RosettaCommons: Community-based code sharing facilitates algorithm development [3].

- Folding@home and Rosetta@home: Distributed computing projects leverage volunteered computational resources [3].

- Foldit: Game-based interface engages public in protein structure prediction [3].

Structural Genomics Integration

Structural genomics initiatives systematically determine representative structures for protein families, expanding template coverage [1] [4]. As these efforts progress, homology modeling is destined to become the predominant structure prediction approach, with evolutionarily related templates available for most naturally occurring proteins [4]. Current estimates suggest most modeling cases fall in the 20-30% sequence identity range, highlighting the importance of continued improvement in remote homology detection and alignment methods [4].

Homology modeling remains an indispensable methodology in structural bioinformatics, providing reliable three-dimensional protein models when experimental determination proves challenging. This comprehensive analysis demonstrates that contemporary tools like MODELLER, SWISS-MODEL, I-TASSER, and Phyre2 deliver robust performance across various application scenarios, with selection criteria dependent on target characteristics and modeling objectives. Performance benchmarking confirms that model quality strongly correlates with target-template sequence identity, with modern approaches successfully extending applicability to distant homologs through advanced profile-profile alignment and machine learning.

The integration of artificial intelligence, collective intelligence initiatives, and structural genomics resources continues to expand homology modeling capabilities, progressively narrowing the gap between computational prediction and experimental determination. For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolving landscape offers increasingly sophisticated tools for generating reliable structural hypotheses, with rigorous validation protocols ensuring appropriate application interpretation. As template coverage expands and algorithms refine, homology modeling will continue to serve as a cornerstone technique for translating genomic information into structural insights across diverse biological and therapeutic contexts.

The Critical Importance of Homology Modeling in Bridging the Sequence-Structure Gap

In the era of high-throughput sequencing, a profound gap exists between the number of known protein sequences and their experimentally determined three-dimensional structures. Homology modeling, also known as comparative modeling, stands as a crucial computational technique that bridges this ever-widening sequence-structure divide [11]. This methodology constructs atomic-resolution models of target proteins using their amino acid sequences and experimental structures of related homologous proteins (templates) [1]. The fundamental principle underpinning homology modeling is that protein structure is evolutionarily more conserved than amino acid sequence [1]. Even proteins with diverged sequences often share remarkably similar folds, enabling the prediction of structure for uncharacterized targets based on their relationship to solved templates [5] [1].

The significance of this approach is underscored by statistics: typically, less than 2% of sequences are represented in the Protein Data Bank (PDB), creating a massive knowledge gap that hampers functional understanding and drug discovery efforts [11]. This gap is further exacerbated by the under-representation of important protein categories, such as membrane proteins, which comprise approximately 25-30% of proteins encoded in genomes but only about 1% of PDB structures [5]. Homology modeling directly addresses this challenge by providing reliable 3D structural models for thousands of proteins that would otherwise lack structural characterization, thereby enabling researchers to formulate biochemical hypotheses, design experiments, and accelerate structure-based drug design [11] [1].

Key Homology Modeling Tools and Platforms

The field of homology modeling features a diverse ecosystem of software tools and servers, ranging from fully automated web services to customizable open-source packages. These platforms employ varied algorithms but share the common goal of producing accurate protein structure models from sequence information and evolutionary relationships.

Table 1: Key Homology Modeling Tools and Their Core Features

| Tool/Platform | Access Method | Key Features | Template Identification | Model Generation Engine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWISS-MODEL | Web server, Automated | Fully automated pipeline, Weekly updates for core species, AlphaFoldDB templates, QMEANDisCo quality estimation [12] | BLAST, HHblits | ProMod3 [12] |

| Prostruc | Web interface, Python package | Open-source, User-friendly, Two-stage validation (TM-align, QMEANDisCo), Maximum sequence length of 400 amino acids [6] | BLAST against PDB | ProMod3 [6] |

| Flare Homology Modeling | Commercial software | Integration with structure-based design suite, Builds single/multi-chain models, Supports apo- and liganded proteins [13] | Proprietary protocol | ProMod3 [13] |

| MODELLER | Standalone software | Satisfaction of spatial restraints, Loop modeling, Multiple template incorporation [14] | User-dependent | Spatial restraint satisfaction [14] |

| DeepSCFold | Specialized pipeline | Focus on protein complexes, Sequence-derived structure complementarity, Enhanced paired MSA construction [15] | Deep learning-predicted structural similarity | AlphaFold-Multimer [15] |

Automated Servers and Specialized Tools

SWISS-MODEL represents the gold standard for fully automated homology modeling, making protein structure prediction accessible to life science researchers worldwide without requiring computational expertise [12]. Its automated pipeline regularly models sequences for core species based on the latest UniProtKB proteome, ensuring currentness. Recent enhancements include the integration of AlphaFoldDB structures as templates, expanding the template repertoire available for model construction [12].

For researchers requiring more customization or working with protein complexes, specialized tools have emerged. DeepSCFold represents a cutting-edge approach specifically designed for modeling protein complex structures, a significant challenge in structural biology [15]. This method uses sequence-based deep learning models to predict protein-protein structural similarity and interaction probability, providing a foundation for constructing deep paired multiple-sequence alignments (MSAs) that significantly improve complex structure prediction accuracy compared to standard methods [15].

Open-Source and Customizable Solutions

Prostruc exemplifies the trend toward open-source, accessible homology modeling tools. Developed as a Python-based package, it integrates Biopython for sequence alignment, BLAST for template identification, and ProMod3 for structure generation [6]. Its design philosophy prioritizes user-friendliness without sacrificing capability, offering both a cloud-based web interface for novices and a Python package for advanced users seeking to extend functionality or integrate the tool into automated pipelines [6].

MODELLER has long served as a foundational tool in the homology modeling landscape, implementing the comparative protein structure modeling by satisfaction of spatial restraints [14]. Unlike fully automated servers, MODELLER requires more user input but offers greater control over the modeling process, including the ability to model loops in protein structures, optimize models with respect to flexibly defined objective functions, and perform multiple alignment of sequences and structures [14].

Experimental Benchmarking and Performance Comparison

Rigorous benchmarking against experimental structures provides critical insights into the performance and limitations of homology modeling methods. Independent evaluations using standardized datasets enable objective comparison of tools across various difficulty scenarios.

Assessment Metrics and Methodologies

The accuracy of homology models is typically quantified using several key metrics. The Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) measures the average distance between corresponding atoms in predicted and experimental structures, with lower values indicating better accuracy. The Template Modeling Score (TM-score) provides a more holistic measure of global fold similarity, with scores above 0.5 indicating generally correct topology and scores above 0.8 indicating high accuracy [15]. QMEANDisCo is specifically designed for model quality estimation without knowledge of the native structure, combining distance constraints and structural features to evaluate model reliability [12] [6].

Benchmarking protocols generally involve testing methods on datasets of known structures that are withheld during model development. The CASP (Critical Assessment of Techniques for Protein Structure Prediction) experiments represent the most rigorous independent evaluations, where predictors blindly predict structures recently solved but not yet publicly available [16] [15]. Additionally, specialized benchmark sets like HOMEP for membrane proteins enable domain-specific performance assessments [5].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Homology Modeling Tools on Standard Benchmarks

| Tool/Method | Sequence Identity Range | Reported RMSD (Å) | TM-score | Key Application Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Homology Modeling | 30% | ~2.0 (TM regions) [5] | N/A | Membrane proteins, Single-chain soluble proteins |

| DeepSCFold | Variable (CASP15 targets) | N/A | 11.6% improvement over AlphaFold-Multimer [15] | Protein complexes, Antibody-antigen interfaces |

| Prostruc | >30% (benchmarking) | Competitive with SWISS-MODEL, I-TASSER, Phyre2 [6] | Competitive with established tools [6] | Single-chain proteins (<400 residues) |

| Profile-Profile Methods | 20-30% | Significant improvement over sequence-based [5] | N/A | Distant homology detection |

Performance Across Protein Categories

The accuracy of homology models varies significantly based on the relationship between target and template. Research indicates that acceptable models (with Cα-RMSD values ≤ 2.0 Å in transmembrane regions) can be obtained for template sequence identities of 30% or higher when accurate sequence alignments are used [5]. This relationship holds true even for challenging protein categories like membrane proteins, for which homology modeling appears at least as applicable as for water-soluble proteins [5].

For protein complexes, recent advances have demonstrated substantial improvements. DeepSCFold shows an 11.6% improvement in TM-score compared to AlphaFold-Multimer and 10.3% improvement over AlphaFold3 on CASP15 multimer targets [15]. Even more impressive are its gains on antibody-antigen complexes, where it enhances the prediction success rate for binding interfaces by 24.7% and 12.4% over AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively [15].

Experimental Protocols for Homology Modeling

A standardized homology modeling workflow consists of multiple stages, each requiring specific methodological considerations to maximize the accuracy and reliability of the resulting structural models.

Standard Homology Modeling Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core workflow implemented by most homology modeling tools:

Diagram 1: Standard homology modeling workflow with quality control loop.

Detailed Methodological Considerations

Template Selection and Alignment Strategies

The initial and most critical step in homology modeling involves identifying appropriate template structures and generating accurate target-template alignments. Template identification typically employs sequence database search tools like BLAST, PSI-BLAST, or HHblits to find structurally characterized proteins with significant sequence similarity to the target [6] [1]. For distantly related proteins, profile-profile alignment methods and protein threading (fold recognition) techniques can identify templates with minimal sequence similarity but structural homology [5] [1].

The selection of an optimal template involves multiple considerations beyond mere sequence identity. Researchers should evaluate the biological relevance of the template (e.g., similar function, same biological context), the experimental quality of the template structure (resolution, R-factors for crystal structures), and the completeness of coverage across the target sequence [1]. For membrane proteins, studies have demonstrated that high-accuracy alignments can be obtained using state-of-the-art profile-to-profile methods developed for water-soluble proteins, with improvements observed when weights derived from secondary structure predictions are incorporated [5].

Model Construction and Refinement

Once a target-template alignment is established, model construction proceeds through one of several computational approaches. The satisfaction of spatial restraints method, implemented in MODELLER, converts the alignment into spatial restraints for main-chain atoms, side-chain conformations, and steric boundaries, then optimizes the model to satisfy these restraints [14]. Fragment assembly approaches construct models by combining structurally conserved core regions with variable loops obtained from fragment libraries [1]. Modern implementations like ProMod3, used in SWISS-MODEL, Prostruc, and Flare, integrate multiple methods and leverage the growing diversity of available template structures [12] [6] [13].

Regions without template coverage, particularly loops, present special challenges in model construction. Loop modeling algorithms employ various strategies including conformation sampling from structural databases, ab initio construction using physical principles, or hybrid approaches [14] [1]. Similarly, side-chain placement often uses rotamer libraries derived from high-resolution structures, with selection based on steric compatibility and local environmental compatibility [1].

Successful homology modeling requires access to specialized computational resources, databases, and software tools that collectively form the essential "research reagent solutions" for structural bioinformatics.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Homology Modeling

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Sequence Databases | UniProtKB, NCBI nr | Source of target sequences and homologs | Comprehensive, annotated, regularly updated [15] |

| Structural Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB), AlphaFold DB | Source of template structures | Experimentally determined and predicted structures [12] [6] |

| Sequence Search Tools | BLAST, HHblits, PSI-BLAST | Identification of homologous sequences and potential templates | Detection of remote homologs via profile methods [5] [6] |

| Alignment Software | ClustalW, MUSCLE, T-Coffee, MAFFT | Generation of target-template alignments | Multiple sequence alignment, profile-profile alignment [5] |

| Quality Assessment Tools | QMEANDisCo, MolProbity, TM-align | Evaluation of model reliability | Geometric quality, statistical potential, comparison metrics [12] [6] |

| Visualization Platforms | PyMOL, ChimeraX | Model inspection and analysis | 3D visualization, structural analysis, figure generation |

Beyond the core modeling software, researchers require access to specialized databases and computational infrastructure. Multiple sequence alignment databases such as UniRef and metagenomic databases provide the evolutionary information essential for constructing accurate profiles, particularly for detecting distant homologies [15]. For modeling protein complexes, resources that capture protein-protein interaction data, such as paired multiple sequence alignments, become crucial for capturing inter-chain co-evolutionary signals [15].

Computational requirements vary significantly across tools. While web servers like SWISS-MODEL offer accessibility without local computational resources [12], local installation of tools like MODELLER or Prostruc requires appropriate computing infrastructure [6] [14]. For large-scale modeling projects or complex systems, access to high-performance computing clusters or GPU acceleration can dramatically reduce processing time, especially for deep learning-based approaches like DeepSCFold [15].

Emerging Trends and Methodological Convergence

The field of homology modeling is experiencing rapid evolution, largely driven by the integration of deep learning methodologies and the influence of AlphaFold-based technologies [16] [15]. The CASP16 experiments in 2024 reaffirmed the dominance of deep learning in biomolecular structure prediction, particularly for protein domain folding, which is now considered largely a solved problem [16]. However, significant challenges remain in modeling large, complex assemblies and capturing conformational dynamics [16].

An important trend is the convergence of traditional homology modeling with deep learning approaches. While traditional methods continue to excel for close homologs, deep learning extends modeling capabilities to regions with minimal template support. This synergy is evident in tools like SWISS-MODEL's incorporation of AlphaFoldDB templates [12] and DeepSCFold's use of sequence-derived structural complementarity to enhance complex prediction [15]. Furthermore, the increasing focus on modeling multi-component systems - including proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules, and ions - represents a frontier where homology modeling principles integrate with other computational structural biology techniques [16] [15].

Homology modeling maintains its critical importance in structural biology despite the emergence of revolutionary deep learning methods. Its foundation in evolutionary relationships provides an interpretable framework for model generation, while ongoing methodological advances continue to expand its applicability to challenging targets like membrane proteins and multi-chain complexes [5] [15]. The diverse ecosystem of tools - from automated servers to customizable open-source packages - ensures accessibility for researchers across computational expertise levels [12] [6].

As the sequence-structure gap persists due to the accelerating pace of sequencing technologies, homology modeling's role in bridging this divide becomes increasingly vital. By providing reliable structural context for uncharacterized proteins, it enables hypothesis generation, experimental design, and structure-based drug discovery across the life sciences. Future advancements will likely focus on improving accuracy for distant homologs, modeling conformational flexibility, and enhancing accessibility for non-specialists, ensuring that homology modeling remains an indispensable component of the structural biology toolkit.

Homology modeling, also known as comparative modeling, is a computational technique that predicts the three-dimensional (3D) structure of a protein (the "target") from its amino acid sequence based on its similarity to one or more proteins with experimentally determined structures (the "templates") [17] [18]. This method relies on the fundamental observation that protein structure is more evolutionarily conserved than amino acid sequence, and that small changes in sequence typically result in only minor variations in 3D structure [17] [19]. With experimental structure determination techniques like X-ray crystallography and NMR spectroscopy being time-consuming and not universally successful, especially for membrane proteins, homology modeling serves as a vital tool for obtaining structural insights for the vast majority of proteins whose structures remain unknown [17]. The applicability of template-based modeling has expanded significantly, with approximately 70% of all known sequences now having at least one domain detectably related to a protein of known structure [18].

The quality of a homology model is directly influenced by the degree of sequence similarity between the target and the template. Table 1 outlines the general relationship between sequence identity and expected model quality, guiding researchers on the appropriate applications for models at different accuracy levels [17].

Table 1: Relationship Between Sequence Identity and Model Quality

| Sequence Identity | Expected Model Quality | Recommended Applications |

|---|---|---|

| > 50% | High | Structure-based drug design, detailed mechanistic studies |

| 30% - 50% | Medium | Guiding mutagenesis experiments, molecular docking |

| < 30% | Low (Twilight Zone) | Preliminary fold assignment, tentative functional insights |

The Homology Modeling Workflow

The process of homology modeling is a multi-step pipeline where the output of each stage feeds into the next. Accuracy at every step is critical for generating a reliable final model [17] [18] [19]. The workflow can be broken down into five key stages, as illustrated in the following diagram:

Step 1: Template Identification and Selection

The initial and arguably most critical step is identifying the most suitable template structure(s) from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [20] [18].

Methodology:

- Sequence Database Search: The target sequence is used as a query to search against databases of known protein structures using tools like BLAST or PSI-BLAST [17] [18]. For more distant relationships, more sensitive profile-based methods like HHsearch or HMMER are employed [17] [18].

- Selection Criteria: From the list of potential templates, the best candidate(s) are selected based on several factors [20]:

- Sequence Similarity: The template with the highest sequence identity to the target is generally preferred.

- Coverage: The template should cover as much of the target sequence as possible.

- Structure Quality: For experimental structures, higher resolution (for X-ray crystallography) and a lower R-factor are indicators of higher quality.

- Biological Relevance: The physiological context of the template is considered, including the presence of relevant ligands, similar quaternary structure, and environmental factors like pH.

Step 2: Sequence Alignment

This step establishes a residue-by-residue correspondence between the target and template sequences, determining which structural elements will be copied [19]. Alignment errors are a major source of significant errors in the final model [17].

Methodology:

- Alignment Algorithms: Both pairwise (target-to-template) and multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) can be used. MSAs, which incorporate information from related protein families, often improve accuracy for distantly related proteins [17] [19].

- Tools: Common programs include ClustalW, T-Coffee, MUSCLE, and PROBCONS [17]. For complex cases, methods that incorporate structural information from the template (e.g., 3D-Coffee) can be more reliable [17].

- Handling Gaps: Regions where the target sequence has insertions or deletions ("indels") relative to the template are identified. These often correspond to loop regions and require special attention during model building [19].

Step 3: Model Building

In this step, the 3D coordinates of the target protein are calculated based on the template structure and the sequence alignment [17].

Methodology:

- Backbone Construction: The coordinates of the backbone atoms (N, Cα, C, O) are copied from the template for all aligned residues [19].

- Loop Modeling: Regions corresponding to gaps in the alignment (insertions/deletions) are modeled separately. This can be done through:

- Side-Chain Placement: The side chains of amino acids are built using rotamer libraries, which are statistical representations of preferred side-chain conformations observed in high-resolution structures. Tools like SCWRL are specialized for this task [18] [19].

Step 4: Model Refinement

The initial model often contains steric clashes and unideal geometry. Refinement aims to correct these issues and improve the model's physical realism [17].

Methodology:

- Energy Minimization: The model is subjected to molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER) to relieve atomic clashes and reduce overall strain by adjusting atomic positions [17] [19].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation: More advanced refinement may use short MD simulations to sample conformational space around the initial model, allowing the structure to relax into a more stable, low-energy state [19].

Step 5: Model Validation

The final and essential step is to evaluate the quality and reliability of the refined model. This distinguishes trustworthy models from those that may be structurally unsound [17] [19].

Methodology:

- Stereochemical Quality Checks: Tools like PROCHECK and MolProbity assess fundamental geometric parameters, including bond lengths, bond angles, and Ramachandran plot outliers (which validate backbone torsion angles) [18] [19].

- Statistical Potential Functions: Scores like DOPE (Discrete Optimized Protein Energy) and QMEAN evaluate the model's "3D profile" by comparing the likelihood of its atomic interactions against those in a database of known, high-quality structures [19].

- Physicochemical Plausibility: The model is checked for a hydrophobic core, proper burial of charged residues, and realistic solvation energy.

Comparative Performance of Modeling Tools

Different software tools and servers automate the homology modeling process to varying degrees. Their performance can vary based on the target-template relationship and the specific steps involved. Table 2 summarizes key tools and their primary characteristics, while Table 3 presents quantitative performance data from recent studies.

Table 2: Key Homology Modeling Tools and Servers

| Tool/Server Name | Type | Key Features | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| MODELLER [18] [19] | Standalone Program | Integrates all modeling steps; highly flexible via Python scripting | Download |

| SWISS-MODEL [18] [19] | Web Server | Fully automated, user-friendly pipeline; high-quality models for clear homologs | Web interface |

| I-TASSER [18] [19] | Hybrid Server | Integrates threading, comparative, and ab initio modeling for difficult targets | Web interface |

| AlphaFold2/3 [15] | Advanced AI | Deep learning system that has revolutionized prediction accuracy; often outperforms traditional methods | Download/Web |

| Phyre2 [19] | Web Server | Intensive mode uses homology detection for hard targets; user-friendly | Web interface |

| DeepSCFold [15] | Advanced Pipeline | Specialized for protein complexes; uses deep learning for interface prediction | Download |

Table 3: Comparative Performance Data of Modeling Tools

| Tool / Method | Benchmark Set | Performance Metric | Result | Context / Comparison |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSCFold [15] | CASP15 Multimer Targets | TM-score Improvement | +11.6% and +10.3% | Outperformed AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3, respectively |

| DeepSCFold [15] | SAbDab Antibody-Antigen Complexes | Interface Prediction Success Rate | +24.7% and +12.4% | Higher success than AlphaFold-Multimer and AlphaFold3 |

| Homology Modeling (General) | Various [17] | Applicability to Genome Sequences | ~70% | Fraction of domains detectably related to a known structure |

| Models with >50% Identity [17] | Drug Discovery Applications | Accuracy | Sufficient for drug design | High-quality models suitable for structure-based design |

Experimental Protocols for Key Analyses

Protocol for Template Selection and Model Building

This protocol outlines a standard procedure for creating a homology model using a widely adopted tool like MODELLER [18].

- Template Search: Perform a BLASTP search of the target sequence against the PDB. Use an E-value cutoff of 0.001 to identify statistically significant hits.

- Template Analysis: From the BLAST results, compile a list of potential templates. Compare them based on sequence identity, query coverage, and the resolution of the experimental structure. Select the single best template or a set of templates that cover different domains of the target.

- Sequence Alignment: Generate a multiple sequence alignment between the target and the selected template(s) using a robust algorithm like MUSCLE or T-Coffee. Manually inspect and adjust the alignment, paying close attention to the placement of functionally important residues (e.g., active site residues).

- Model Generation: Use MODELLER to generate an initial 3D model. A common practice is to generate multiple models (e.g., 100) to sample different conformational possibilities.

- Model Selection: Evaluate all generated models using the DOPE (Discrete Optimized Protein Energy) score or other statistical potentials. Select the model with the most favorable score for subsequent refinement.

Protocol for Model Validation

This protocol describes how to rigorously assess the quality of a generated homology model [21] [19].

- Stereochemical Check: Run the model through PROCHECK or MolProbity. A high-quality model should have over 90% of its residues in the most favored regions of the Ramachandran plot, with less than 1% in disallowed regions.

- 3D Profile Assessment: Calculate the model's 3D-1D score using VERIFY3D. This analysis determines the compatibility of the amino acid sequence with its structural environment. A good model will have a high proportion of residues scoring above 0.2.

- Internal Packing and Energy Evaluation: Use the Prosa-web server to obtain a Z-score for the model. The Z-score should be within the range typically observed for native proteins of similar size.

- Comparative Analysis (if possible): If the true structure is subsequently solved experimentally, quantify the model's accuracy by calculating the Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) of the Cα atoms between the model and the experimental structure after superposition.

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Resources for Homology Modeling

| Resource Name | Category | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Primary repository for experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids. |

| BLAST / PSI-BLAST | Software | Identifies homologous sequences and potential template structures from sequence databases. |

| ClustalW / MUSCLE | Software | Generates multiple sequence alignments between the target and template sequences. |

| MODELLER | Software | A computational tool that builds a 3D model of the target protein from its sequence and an alignment with a template structure. |

| PyMOL / UCSF Chimera | Software | Visualizes and analyzes protein structures, models, and their molecular properties. |

| PROCHECK / MolProbity | Software | Validates the stereochemical quality of the generated protein model. |

| DOPE / QMEAN | Scoring Function | Knowledge-based potentials for assessing the quality of a protein model and selecting the best among many. |

Homology modeling, also known as comparative modeling, remains an indispensable technique in structural biology for predicting the three-dimensional structure of a protein from its amino acid sequence. Its continued relevance persists even alongside revolutionary deep learning approaches like AlphaFold, particularly for modeling specific conformational states or protein complexes. The accuracy of any homology model is not deterministic but is governed by three interdependent factors: the sequence identity between the target and template, the quality of the template structure itself, and the accuracy of the sequence alignment. This guide objectively examines these governing factors by synthesizing data from experimental benchmarks and comparing the performance of modern modeling tools, providing researchers with a framework for maximizing predictive accuracy.

The Foundation: How Key Factors Influence Model Accuracy

Sequence Identity and Structural Similarity

Sequence identity is the most significant predictor of potential model accuracy. Experimental studies using benchmark sets like HOMEP have quantified the relationship between sequence identity and structural deviation, measured by Cα Root Mean Square Deviation (Cα-RMSD).

Table 1: Sequence Identity vs. Model Accuracy in Transmembrane Regions

| Sequence Identity | Expected Cα-RMSD | Model Quality Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 30% | ≤ 2.0 Å | Acceptable accuracy |

| 25% | 2–4 Å | Moderate accuracy |

| < 20% | Often >4 Å | "Twilight zone"; low reliability |

Data from membrane protein benchmarks indicates that homology modeling is at least as applicable to membrane proteins as it is to water-soluble proteins, with acceptable models obtained at template sequence identities of 30% or higher when using an accurate alignment [5]. For soluble proteins, the relationship is similar, with models typically having ~1–2 Å RMSD at 70% sequence identity but only 2–4 Å agreement at 25% sequence identity [1].

Template Quality Assessment

The quality of the experimental template structure directly propagates into the model. Key template assessment criteria include:

- Experimental Resolution: For X-ray crystallography structures, lower resolution (e.g., <2.0 Å) generally indicates higher reliability.

- Coverage: The fraction of the target sequence that can be mapped to the template structure.

- Biochemical Relevance: The physiological relevance of the template's experimental conditions (e.g., ligand-bound vs. unbound, pH) [19].

Modern template libraries, such as the one in Phyre2.2, now include representatives for both apo and holo forms of proteins when available, allowing researchers to select the most functionally relevant template [22].

Alignment Accuracy

The sequence alignment that maps target residues to template residues is arguably the most critical step in model generation. Profile-to-profile alignment methods have been shown to produce significantly more accurate alignments than simple sequence-to-sequence methods, especially at lower sequence identities [5]. Improvements are particularly observed when weights derived from the secondary structure of the query and template are incorporated into the alignment scoring [5].

Comparative Performance of Homology Modeling Tools

The practical application of these principles is embodied in various homology modeling software packages and servers. The table below compares the performance, methodologies, and optimal use cases of leading tools based on published benchmarks and technical descriptions.

Table 2: Homology Modeling Tool Comparison

| Tool | Primary Method | Template Identification | Multiple Template Support | Key Strength | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MODELER | Satisfaction of spatial restraints | User-defined or automated | Yes [23] | Produces models better than any single-template model [23] | General-purpose modeling; multi-template projects |

| Phyre2.2 | Hybrid (Template-based + Fragment assembly) | HMM-HMM (HHblits) or AlphaFold model selection | Yes [22] | Ease of use; integrated pipeline; identifies domain-specific templates [22] | Non-experts; high-throughput modeling |

| Rosetta | Fragment assembly & hybridization | Various (including custom) | Yes (Simultaneous template swapping) [24] | Excellent for low-identity templates (down to ~20%) [24] | Challenging targets (e.g., GPCRs, low-identity templates) |

| SWISS-MODEL | Similar to MODELLER | Automated BLAST/HHblits | Yes | User-friendly web interface; high automation [19] | Quick, automated model generation |

| Prostruc | Integration of ProMod3 | BLAST against PDB | Information missing | Open-source; Python package availability [25] | Customizable pipelines; educational use |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking Modeling Accuracy

To objectively compare tool performance, researchers employ standardized benchmarking protocols. The following methodology, derived from published studies, outlines a robust framework for evaluating homology modeling pipelines.

Workflow for Homology Modeling Benchmarking

The following diagram illustrates the key stages in a standardized benchmarking protocol for homology modeling tools.

Protocol Details

Benchmark Dataset Creation: A non-redundant set of high-resolution experimental structures is selected to serve as known "targets." For a rigorous test, templates with sequence identities below 40% are often used to simulate real-world challenging scenarios [24]. Specialized sets like HOMEP exist for membrane proteins [5].

Template Identification: For each target, templates are identified using various methods:

- Sequence-based search (BLAST): Provides a baseline performance measure [25].

- Profile-based search (PSI-BLAST, HHblits): More sensitive for detecting distant homologs. HHblits using HMM-HMM comparison is a state-of-the-art approach implemented in Phyre2 and others [5] [22].

- Fold recognition (Threading): Used when no clear sequence homologs are available.

Model Generation: Identified templates and their alignments are fed into different homology modeling programs (e.g., MODELLER, Rosetta, Phyre2.2) to generate 3D models for the target sequence.

Model Quality Assessment: Generated models are compared against the experimental reference structure using:

- Global Metrics: RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation), TM-score (Template Modeling Score), and GDT_TS (Global Distance Test Total Score) measure overall structural similarity. TM-score is particularly valuable as it is less sensitive to terminal regions and correlates well with human assessment [23].

- Local Geometry Checks: Tools like MolProbity assess stereochemical quality, including Ramachandran plot outliers and clash scores [19].

- Knowledge-Based Scores: Methods like QMEAN and DOPE (Discrete Optimized Protein Energy) evaluate model quality based on statistical potentials derived from known structures [25] [19].

Data Analysis and Comparison: Results are aggregated to determine which tool, protocol, or alignment method consistently produces the most accurate models across the benchmark set.

Successful homology modeling relies on a suite of computational tools and databases. The table below details key resources that constitute the essential toolkit for researchers.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Homology Modeling

| Item Name | Type | Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB (Protein Data Bank) | Database | Repository of experimentally determined protein structures [5] | Primary source for template structures |

| BLAST/PSI-BLAST | Software Suite | Identifies homologous sequences and structures from databases [1] | Fast sequence similarity search; sensitive profile-based search |

| HHsuite (HHblits, HHsearch) | Software Suite | Sensitive homology detection and alignment via HMM-HMM comparison [22] | Greatly improved remote homology detection |

| Clustal Omega | Software | Generates multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) [5] | Scalable for large datasets |

| MODELLER | Software | Builds 3D models from target-template alignments [23] [1] | Implements spatial restraint method |

| Rosetta | Software Suite | Comprehensive modeling suite for structure prediction and design [24] | Powerful fragment-based and multi-template hybridization |

| PyMOL | Software | Molecular visualization system [26] | High-quality 3D visualization and figure generation |

| MolProbity | Web Service | Validates stereochemical quality of protein structures [19] | Identifies geometric outliers and clashes |

| UniRef50/90 | Database | Clustered sets of protein sequences from UniProt [22] | Non-redundant sequences for building high-quality MSAs |

The accuracy of homology models is governed by a triad of factors: sufficient sequence identity (>30% for reliable models), high-quality template structures, and optimal sequence alignments generated by profile-based methods. Experimental data shows that while modern tools like MODELLER and Rosetta can produce improved models using multiple templates, the average quality does not always improve significantly, and careful selection is required [23]. For the most challenging targets, such as membrane proteins or those in the "twilight zone" of sequence identity, integrated strategies that combine advanced alignment techniques, multiple templates, and robust refinement protocols are essential. By understanding these governing factors and leveraging the comparative performance data of available tools, researchers can make informed decisions to maximize the accuracy and reliability of their homology models for downstream applications in drug discovery and functional analysis.

A Practical Workflow: From Sequence to Model and Application in Drug Discovery

Homology modeling, also termed comparative modeling, is a foundational computational technique for predicting the three-dimensional structure of a target protein by leveraging its sequence similarity to experimentally determined templates [25]. The accuracy of a homology model is critically dependent on the initial and crucial step of identifying a suitable template, a process for which the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) is frequently the tool of first resort [27]. BLAST finds regions of local similarity between biological sequences and calculates the statistical significance of these matches, allowing researchers to infer functional and evolutionary relationships [28]. In the context of a structural bioinformatics project, initiating a modeling effort requires a clear understanding of the input requirements for BLAST and a framework for evaluating its performance against modern, alternative methods for template identification and remote homology detection. This guide provides a comparative analysis of BLAST against next-generation profile-based and deep-learning tools, offering structured experimental data and protocols to inform researchers' and drug development professionals' strategic choices.

Input Requirements and Operational Protocols for BLAST

Fundamental Input Requirements

To initiate a BLAST search for template identification, the following inputs are required:

- Query Sequence: The amino acid sequence of the target protein for which a structure is desired. The sequence should be in a standard format (e.g., FASTA).

- Database: The protein sequence database to search against. For template identification, the Protein Data Bank (PDB) is the primary database, as it contains sequences of proteins with known structures [25].

- BLAST Program: The specific BLAST algorithm must be selected. For protein template searches, BLASTP (protein-protein BLAST) is the standard and correct program to use [29].

Detailed BLASTP Protocol for Template Identification

The following protocol outlines a standard BLASTP search for identifying homologous template structures.

Step 1: Sequence Retrieval and Validation Retrieve the target protein sequence from a database like UniProt and ensure it is in FASTA format. Validate the sequence for correctness and completeness. Some automated pipelines, like that of the Prostruc tool, enforce a maximum sequence length (e.g., 400 amino acids) for computational efficiency [25].

Step 2: Database Selection Configure BLASTP to search against the PDB database. This ensures the results are restricted to proteins with experimentally solved structures that can serve as modeling templates.

Step 3: Parameter Configuration While BLAST can be run with default parameters, template identification often uses more stringent criteria to select reliable templates [25]. Key parameters include:

- E-value Threshold: A lower E-value cutoff (e.g., 0.01) increases stringency, filtering out statistically insignificant matches.

- Identity Threshold: A minimum percentage identity (e.g., 30%) helps ensure selected templates have sufficient sequence similarity to the target.

Step 4: Execution and Result Analysis Execute the BLASTP search. Analyze the results by examining the list of significant hits, prioritizing templates based on a combination of low E-value, high percentage identity, and high query coverage.

Figure 1: A standard workflow for identifying a structural template using BLASTP, from sequence input to template selection.

Performance Comparison: BLAST vs. Modern Homology Detection Tools

While BLAST is a robust and accessible tool, its performance must be compared to modern alternatives, especially for detecting remote homologies where sequence similarity is low. The following tables summarize key benchmarking data.

Table 1: Overview of homology detection tools and their core methodologies.

| Tool | Type | Core Methodology | Key Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| BLAST (BLASTP) | Sequence-based | Heuristic local alignment with substitution matrices [30] | Speed, ease of use, reliability for close homologs [30] |

| CS-BLAST | Profile-based | Constructs a position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM) from the query [30] | Higher accuracy for remote homology detection [30] |

| PHMMER | Profile-based | Searches a query profile HMM against a sequence database [30] | One of the highest accuracy methods; sensitive [30] |

| HHSEARCH | Profile-based | HMM-HMM comparison against a database of profile HMMs [30] [27] | Powerful for very remote homology detection [27] |

| TM-Vec | Deep Learning | Twin neural network predicts TM-score (structural similarity) from sequence [31] | Scalable structure-aware search without 3D coordinates [31] |

Table 2: Comparative performance data from benchmark studies. Accuracy is often measured by the ability to correctly classify homologous vs. non-homologous protein pairs.

| Tool | Reported Accuracy | Remote Homology Performance | Computational Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCBI-BLAST | Baseline | Declines significantly below ~25% sequence identity [31] | Very Fast [30] |

| CS-BLAST | High | Superior to BLAST [30] | Moderate (faster than other profile methods) [30] |

| PHMMER | High | Superior to BLAST [30] | Moderate [30] |

| FASTA/USEARCH/UBLAST | Lower than profile methods | Large trade-offs of accuracy for speed [30] | Very Fast [30] |

| TM-Vec | High (r=0.97 with TM-align) | Accurately detects structural similarity even at <0.1% sequence identity [31] | Fast (sublinear search time) [31] |

The data reveals a clear hierarchy. Standard sequence-based tools like BLAST are fast and reliable for close homologs but are outperformed by profile-based methods like CS-BLAST and PHMMER for detecting remote homologs, with the latter two showing the highest overall accuracy in benchmarks [30]. Furthermore, emerging deep learning tools like TM-Vec represent a paradigm shift by directly predicting structural similarity from sequence, enabling the detection of homologs with extremely low sequence identity that elude even profile-based methods [31].

Advanced Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To objectively compare the performance of BLAST with alternative tools, researchers can implement the following benchmarking protocols.

Benchmarking Protocol 1: Remote Homology Detection

This protocol is based on benchmarks used to evaluate "next-generation" search tools [30].

1. Dataset Generation:

- Construct a benchmark dataset from curated resources like Pfam, SCOP/SUPERFAMILY, or CATH/Gene3D, which classify protein domains into families and superfamilies based on homology [30].

- Define positive gold standard pairs as multi-domain proteins where all corresponding domains belong to the same family/clan/superfamily. Define negative gold standard pairs as proteins where no domains are in the same family/clan/superfamily [30].

- Sample protein pairs from these sets to avoid bias toward highly populated families.

2. Tool Execution:

- Run each tool (e.g., BLAST, CS-BLAST, PHMMER, HHSEARCH, TM-Vec) on all protein pairs in the benchmark dataset. Use default parameters for each tool unless specified by the experimental design.

- Record the output score (e.g., E-value, bit score) for each protein pair from each tool.

3. Performance Evaluation:

- Calculate standard performance metrics such as precision and recall by comparing tool predictions against the gold standard labels.

- Generate Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves and calculate the Area Under the Curve (AUC) to provide a comprehensive view of each tool's accuracy.

Benchmarking Protocol 2: Structural Classification Accuracy

This protocol assesses how well template identification translates into correct structural classification, leveraging structural databases like ECOD [27].

1. Dataset Preparation:

- Obtain a set of protein domains with experimental structures and their verified homology classifications from ECOD.

- Download the corresponding AlphaFold2-predicted models for these domains from AlphaFoldDB.

2. Query and Library Setup:

- Design a blind test by splitting the dataset into a query set (simulating unclassified proteins) and a library set (known classified proteins) based on PDB release date to ensure a fair assessment [27].

- For the library, use either experimental structures or high-confidence predicted models (pLDDT > 60).

3. Search and Alignment:

- Use BLAST to search each query sequence against the library of sequences.

- In parallel, use structural comparison tools (e.g., Dali, Foldseek) to search each query structure (experimental or predicted) against the library of structures.

- For each query, retrieve the top hit from each method.

4. Accuracy Assessment:

- Determine if the top hit from each method belongs to the same homologous group in the ECOD classification.

- Calculate the top-1 accuracy for BLAST and the structural methods. Studies have shown that structural comparisons can outperform sequence-based methods like HHsearch (a profile-based tool) when considering remote homology, with no significant performance drop when using high-confidence AlphaFold2 models versus experimental structures [27].

Figure 2: A generalized workflow for benchmarking the performance of different homology detection tools.

Table 3: Key resources and computational tools for homology detection and template identification.

| Resource / Tool | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| NCBI BLAST+ Suite | Software Suite | Command-line tools for executing various BLAST searches and formatting databases [29]. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Primary repository of experimentally determined 3D structures of proteins; the target database for template searches [25]. |

| Pfam / SCOP / CATH / ECOD | Curated Database | Databases providing hierarchical classifications of protein domains into families and superfamilies; essential for creating benchmark datasets [30] [27]. |

| AlphaFold Database (AFDB) | Database | Repository of predicted protein structures generated by AlphaFold2; an expanding resource for structural comparisons and template identification [27]. |

| HH-suite | Software Suite | A package containing HHsearch and other tools for sensitive protein homology detection based on HMM-HMM comparisons [30] [27]. |

| Dali / Foldseek | Software Tool | Algorithms for comparing protein structures in 3D; used to validate homology and benchmark sequence-based methods [31] [27]. |

| TM-align | Software Tool | Algorithm for measuring structural similarity using TM-scores; used as a gold standard in training tools like TM-Vec [31]. |

Sequence homology detection forms the foundational pillar of modern genomics, structural biology, and drug discovery. The ability to accurately infer evolutionary relationships between protein sequences enables researchers to predict molecular functions, elucidate tertiary structures, and identify potential therapeutic targets. Among the diverse computational strategies developed for this purpose, profile-based methods have demonstrated superior performance in detecting remote homologies compared to simple pairwise sequence comparison tools. Specifically, PSI-BLAST (Position-Specific Iterated BLAST) and Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) represent two sophisticated approaches that leverage multiple sequence information to build position-specific scoring systems, enabling them to identify distant evolutionary relationships that escape detection by simpler methods [32].

The strategic selection and application of these tools directly impacts research outcomes across biological domains. In structural genomics, accurate homology detection facilitates reliable template identification for protein structure modeling. In drug discovery, understanding the evolutionary landscape of target protein families helps identify conserved functional domains and potential off-target interactions. This guide provides a comprehensive, evidence-based comparison of PSI-BLAST and HMM-based tools, drawing on experimental benchmarks to equip researchers with the data necessary to select optimal alignment strategies for their specific research contexts.

PSI-BLAST (Position-Specific Iterated BLAST)

PSI-BLAST enhances the sensitivity of traditional BLAST searches through an iterative profile-building process. The algorithm begins with a standard BLASTp search against a protein database using a single query sequence. Significantly aligned sequences from this initial search are then incorporated to construct a position-specific scoring matrix (PSSM), which captures position-specific conservation patterns within the protein family. This PSSM becomes the query for subsequent database searches, with the process repeating through multiple iterations. At each cycle, the profile incorporates new sequence matches, progressively refining its sensitivity to detect increasingly distant homologs [33] [34].

This iterative approach allows PSI-BLAST to detect remote homologies that would be undetectable through single-sequence queries. The algorithm's efficiency stems from its foundation in the well-optimized BLAST architecture, making it substantially faster than many HMM-based methods for profile construction and database searching. Benchmarking studies have demonstrated that PSI-BLAST achieves approximately 40% coverage in recognizing remote homologs (<20% sequence identity) in genome annotation tasks when employing the critical "one-to-many" assessment framework that reflects real-world annotation scenarios [35] [33].

HMM-based Tools (HMMER & SAM)

Profile Hidden Markov Models represent protein families using probabilistic models that explicitly account for evolutionary events including substitutions, insertions, and deletions. HMMs implement position-specific scores for emissions (probability of observing a particular amino acid at a position) and state transitions (probabilities for moving between match, insert, and delete states). This formal probabilistic framework provides a more principled approach to handling indels compared to the heuristic gap penalties employed by PSI-BLAST [32].

Two primary software packages have dominated the HMM landscape: HMMER and SAM. The HMMER package, developed by Sean Eddy, provides comprehensive tools for building, calibrating, and searching with profile HMMs. The SAM package from UC Santa Cruz includes similar functionality along with the T99 (target99) script for automated multiple sequence alignment generation through iterative database searches. While HMMER generally demonstrates faster execution times—typically 1-3 times faster than SAM on databases exceeding 2000 sequences—studies have found that SAM's T99 procedure produces higher quality alignments and better-performing models when using default parameters, particularly for inexpert users [32].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Profile-Based Homology Detection Tools

| Tool | Primary Method | Key Strengths | Implementation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSI-BLAST | Iterative PSSM | Fast profile construction, widely accessible | NCBI BLAST suite | [33] [34] |

| HMMER | Profile HMM | Statistical rigor, efficient calibration | Standalone package | [32] [34] |

| SAM | Profile HMM | Automated alignment generation (T99) | Standalone package | [32] |

Performance Benchmarking: Experimental Comparisons

Remote Homology Detection

Rigorous benchmarking studies have evaluated the performance of PSI-BLAST and HMM-based methods using structured databases like SCOP (Structural Classification of Proteins), where evolutionary relationships are definitively established through structural evidence. One comprehensive assessment compared HMMER, SAM, and PSI-BLAST using identical starting alignments and evaluation criteria, measuring performance through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and detection rates at fixed error thresholds [32].

The findings revealed that when using high-quality multiple sequence alignments as input, SAM consistently produced better models than HMMER under default parameter settings. Importantly, the quality of the input multiple sequence alignment emerged as the most critical factor influencing overall performance for both HMM packages. The study also demonstrated that SAM's T99 iterative database search procedure outperformed PSI-BLAST in remote homology detection, though PSI-BLAST profile scoring remained dramatically faster—more than 30 times faster than SAM model scoring [32].