Comparative Genomics Methods: A Comprehensive Review for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of contemporary comparative genomics methodologies and their transformative applications in biomedical research.

Comparative Genomics Methods: A Comprehensive Review for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

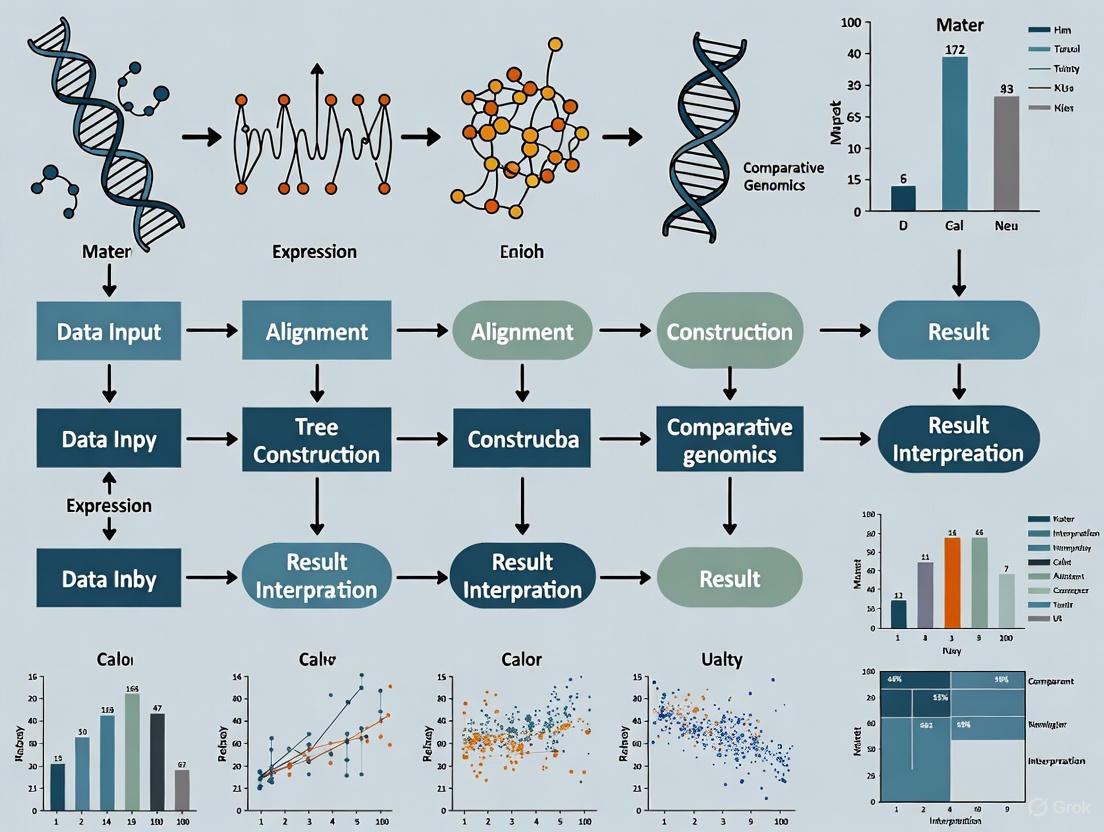

This review provides a comprehensive analysis of contemporary comparative genomics methodologies and their transformative applications in biomedical research. It explores the foundational principles of evolutionary sequence comparison, details current computational tools and pipelines for genome alignment, variant analysis, and pangenome construction, and addresses key challenges in data quality and interpretation. The article highlights validation frameworks and benchmark studies, with a specific focus on applications in drug target discovery, antimicrobial resistance, and understanding host-pathogen interactions. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes methodological advances with practical insights to guide study design and implementation, underscoring the critical role of comparative genomics in advancing human health.

The Evolutionary Foundation and Core Principles of Genomic Comparison

Comparative genomics serves as a cornerstone of modern biological research, enabling scientists to decipher evolutionary relationships, predict gene function, and identify genetic variations through computational analysis of genomic sequences. This field relies on a sophisticated pipeline that transforms raw sequence data into evolutionary insights, with multiple sequence alignment (MSA) and phylogenetic tree construction representing two fundamental computational pillars. The reliability of downstream biological conclusions—from species classification to drug target identification—depends entirely on the accuracy and appropriateness of these computational methods [1].

As genomic databases expand exponentially, the computational challenges in comparative genomics have intensified, driving innovation in algorithm development. Next-generation sequencing technologies now generate trillions of nucleotide bases per run, creating demand for methods that balance scalability, accuracy, and computational efficiency [2]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of current methodologies across the comparative genomics workflow, enabling researchers to select optimal strategies for their specific research contexts within drug development and evolutionary studies.

Multiple Sequence Alignment: Methods and Performance Comparison

Multiple sequence alignment establishes the foundational framework for comparative genomics by identifying homologous positions across biological sequences. The MSA process is inherently NP-hard, making heuristic approaches essential for practical applications [1]. Current MSA methods generally fall into three categories: traditional progressive methods, meta-aligners that integrate multiple approaches, and emerging artificial intelligence-based techniques.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Multiple Sequence Alignment Tools

| Method/Tool | Algorithm Type | Key Features | Accuracy & Performance | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BetaAlign | Deep Learning (Transformer) | Uses NLP techniques trained on simulated alignments; adaptable to specific evolutionary models [3] | Comparable or better than state-of-the-art tools; accuracy depends on training data quality [3] | Large datasets with known evolutionary parameters; phylogenomic studies requiring high precision |

| LexicMap | Hierarchical k-mer indexing | Probe-based seeding with prefix/suffix matching; efficient against million-genome databases [4] | High accuracy with greater speed and lower memory use vs. state-of-the-art methods [4] | Querying genes/plasmids against massive prokaryotic databases; epidemiological studies |

| M-Coffee | Meta-alignment | Consistency-based library from multiple aligners; weighted character pairs [1] | Generally approximates average quality of input alignments [1] | Integrating results from specialized aligners; protein families with challenging regions |

| MAFFT/MUSCLE | Progressive alignment | Heuristic-based; "once a gap, always a gap" principle [1] | Fast but prone to early error propagation [1] | Initial alignment generation; large-scale screening analyses |

Advanced Alignment Strategies: Post-Processing and Realignment

Even the most sophisticated initial alignments often benefit from post-processing refinement to correct errors introduced by heuristic algorithms. Meta-alignment strategies, such as those implemented in M-Coffee and TPMA, integrate multiple independent MSA results to produce consensus alignments that leverage the strengths of different alignment programs [1]. These approaches are particularly valuable when analyzing sequences with regions of high variability or when alignment uncertainty exists.

Realigner methods operate through iterative optimization of existing alignments using horizontal partitioning strategies. These include single-type partitioning (realigning one sequence against a profile), double-type partitioning (aligning two profile groups), and tree-dependent partitioning (dividing alignment based on guide tree topology) [1]. Tools like ReAligner implement these approaches to progressively improve alignment scores until convergence, effectively addressing the "once a gap, always a gap" limitation of progressive methods [1].

Phylogenetic Tree Construction: Methodological Approaches

Phylogenetic trees provide the evolutionary context for comparative genomics, visually representing hypothesized relationships between taxonomic units. The construction of these trees follows a systematic workflow from sequence collection to tree evaluation, with method selection profoundly impacting the resulting topological accuracy.

Phylogenetic Inference Methods: A Comparative Analysis

Table 2: Comparison of Phylogenetic Tree Construction Methods

| Method | Algorithm Principle | Advantages | Limitations | Computational Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighbor-Joining (NJ) | Distance-based clustering using pairwise evolutionary distances [5] | Fast computation; fewer assumptions; suitable for large datasets [5] | Information loss in distance matrix; sensitive to evolutionary rate variation [5] | Low to moderate; efficient for large taxon sets |

| Maximum Parsimony (MP) | Minimizes total number of evolutionary steps [5] | Straightforward principle; no explicit model assumptions [5] | Prone to long-branch attraction; multiple equally parsimonious trees [5] | High for large datasets due to tree space search |

| Maximum Likelihood (ML) | Probability-based; finds tree with highest likelihood under evolutionary model [5] | Explicit model assumptions reduce systematic errors; high accuracy [5] | Computationally intensive; model misspecification risk [5] | Very high; requires heuristic searches for large datasets |

| Bayesian Inference (BI) | Probability-based; estimates posterior probability of trees [5] | Provides natural probability measures; incorporates prior knowledge [5] | Computationally demanding; convergence assessment needed [5] | Extremely high; Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling |

The selection of phylogenetic inference methods depends on dataset size, evolutionary complexity, and computational resources. Distance-based methods like Neighbor-Joining transform sequence data into pairwise distance matrices before applying clustering algorithms, providing computationally efficient solutions for large datasets [5]. In contrast, character-based methods including Maximum Parsimony, Maximum Likelihood, and Bayesian Inference evaluate individual sequence characters during tree search, typically generating numerous hypothetical trees before identifying optimal topologies according to specific criteria [5].

For large-scale phylogenomic analyses, integrated pipelines like Phyling provide streamlined workflows from genomic data to species trees. Phyling utilizes profile Hidden Markov Models to identify orthologs from BUSCO databases, aligns sequences using tools like Muscle or hmmalign, and supports both consensus (ASTER) and concatenation (IQ-TREE, RAxML-NG) approaches for final tree inference [6]. Such pipelines significantly accelerate phylogenetic analysis while maintaining accuracy comparable to traditional methods.

Integrated Analysis: From Alignment to Tree Assessment

Experimental Protocols for Phylogenomic Workflows

Protocol 1: Standard Phylogenetic Analysis from Genomic Data

Sequence Acquisition and Orthology Determination: Collect protein or coding sequences from samples (minimum of four). For ortholog identification, search sequences against Hidden Markov Model profiles from BUSCO database using hmmsearch (PyHMMER v0.11.0). Exclude samples with multiple hits to the same HMM profile to ensure orthology [6].

Multiple Sequence Alignment: Extract sequences matching HMM profiles and align using hmmalign (default) or Muscle v5.3 for higher quality. Trim alignments with ClipKIT v2.1.1 to retain parsimony-informative sites while removing unreliable regions [6].

Marker Selection and Tree Inference: Construct trees for each marker using FastTree v2.1.1. Evaluate phylogenetic informativeness using treeness over relative composition variability (RCV) score calculated via PhyKIT v2.0.1. Retain top n markers ranked by treeness/RCV scores [6].

Species Tree Construction: Apply either consensus approach (building individual gene trees and inferring species tree using ASTER v1.19) or concatenation approach (combining alignments into supermatrix). For concatenation, determine best-fit substitution model using ModelFinder from IQ-TREE package [6].

Protocol 2: Alignment-Free Viral Classification

Feature Extraction: Transform viral genome sequences into numeric feature vectors using one of six established alignment-free techniques: k-mer counting, Frequency Chaos Game Representation (FCGR), Return Time Distribution (RTD), Spaced Word Frequencies (SWF), Genomic Signal Processing (GSP), or Mash [2].

Classifier Training: Use extracted feature vectors as input for Random Forest classifiers. Train separate models for specific viral pathogens (SARS-CoV-2, dengue, HIV) using known lineage information as classification targets [2].

Validation and Application: Evaluate classifier performance on holdout test sets using accuracy, Macro F1 score, and Matthew's Correlation Coefficient. Apply optimized models to classify new viral sequences without alignment steps [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Comparative Genomics

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| BUSCO Database | Marker gene set | Provides universal single-copy orthologs for orthology assessment [6] | Phylogenomic studies across diverse taxa |

| ClipKIT | Alignment trimming software | Trims multiple sequence alignments to retain parsimony-informative sites [6] | Pre-processing alignments for phylogenetic inference |

| IQ-TREE | Phylogenetic software package | Implements maximum likelihood inference with model selection [6] | Species tree construction from aligned sequences |

| TPMA | Meta-alignment tool | Integrates multiple nucleic acid MSAs using sum-of-pairs scores [1] | Improving alignment accuracy through consensus |

| TOPD/FMTS | Tree comparison software | Calculates Boot-Split Distance between phylogenetic trees [7] | Quantifying topological differences between gene trees |

| Chema | Chema | High-Purity Research Compound | Supplier | Chema: A high-purity research compound for biochemical and in vitro studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| Ethylenediaminetetra(methylenephosphonic acid) | EDTMP | High-purity EDTMP reagent for industrial and pharmaceutical research. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic or personal use. | Bench Chemicals |

The comparative genomics workflow represents an integrated system where choices at each stage influence downstream results. Method selection should be guided by research questions, dataset characteristics, and computational resources. For multiple sequence alignment, deep learning approaches like BetaAlign show promise for challenging alignment problems, while efficient tools like LexicMap excel in large-scale database searches. For phylogenetic inference, likelihood-based methods generally provide the highest accuracy when computational resources permit, while distance methods offer practical solutions for massive datasets.

Emerging trends including alignment-free classification and meta-alignment strategies are expanding the methodological toolkit, particularly for applications requiring rapid analysis of large datasets or integration of diverse analytical approaches. As comparative genomics continues to evolve, the optimal application of these methods will remain fundamental to advancing biological discovery and drug development.

Evolutionary distance provides a quantitative framework for measuring genetic divergence between species, serving as a foundational concept in comparative genomics. By quantifying the degree of molecular divergence—through single nucleotide substitutions, insertions, deletions, and structural variations—evolutionary distance enables researchers to select optimal model organisms for studying human biology, disease mechanisms, and evolutionary processes [8]. The strategic selection of species based on evolutionary distance is not merely an academic exercise; it directly impacts the translational potential of biomedical research, where overreliance on traditional "supermodel organisms" has contributed to a 95% failure rate for drug candidates during clinical development [8]. This comparison guide examines current methodologies for quantifying evolutionary distance, evaluates their performance characteristics, and provides a structured framework for selecting species pairs that maximize research insights while acknowledging the limitations of different distance metrics.

The fundamental challenge in evolutionary distance calculation lies in accurately modeling the relationship between observed genetic differences and actual evolutionary divergence time. As sequences diverge, multiple substitutions may occur at the same site, obscuring the true evolutionary history. More sophisticated models account for these hidden changes through various substitution models (Jukes-Cantor, K80, GTR), but each carries specific assumptions about evolutionary processes that may not hold across all lineages or genomic regions [9]. Recent advances in whole-genome sequencing have dramatically expanded the scope of evolutionary comparisons, enabling researchers to move beyond gene-centric analyses to whole-genome comparisons that capture the full complexity of genomic evolution, including structural variations and regulatory element conservation [10] [11].

Methodologies for Quantifying Evolutionary Distance

Alignment-Based Methods

Alignment-based methods constitute the traditional approach for calculating evolutionary distance by directly comparing nucleotide or amino acid sequences. Whole-genome alignment tools like lastZ identify homologous regions between genomes through a seed-and-extend algorithm, providing a foundation for precise nucleotide-level comparison [12]. The key advantage of lastZ lies in its exceptional sensitivity for aligning highly divergent sequences, maintaining alignment coverage even at divergence levels exceeding 40%, where other tools frequently fail [12]. This sensitivity comes at significant computational cost, with mammalian whole-genome alignments requiring approximately 2,700 CPU hours, creating substantial bottlenecks for large-scale analyses [12].

The Average Nucleotide Identity (ANI) approach provides a standardized metric for genomic similarity, traditionally calculated using alignment tools like BLAST or MUMmer [9]. ANI was originally developed as an in-silico replacement for DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) techniques, with a 95% ANI threshold corresponding to the 70% DDH value used for species delineation [9]. Modern implementations such as OrthoANI and ANIb (available through PyANI) differ in their specific methodologies, with ANIb demonstrating superior accuracy in capturing true evolutionary distances despite being computationally intensive [9]. A significant limitation of traditional ANI calculations is their dependence on "alignable regions," which can result in zero or near-zero estimates for highly divergent genomes where homologous regions represent only a small fraction of the total sequence [9].

Table: Comparison of Alignment-Based Evolutionary Distance Methods

| Method | Algorithm | Optimal Use Case | Sensitivity | Computational Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lastZ | Seed-filter-extend with gapped extension | Divergent genome pairs (>40% divergence) | Excellent | Extreme (≈2700 CPU hours for mammals) |

| ANIb | BLAST-based average nucleotide identity | Species delineation, closely related genomes | High | High |

| ANIm | MUMmer-based alignment | Rapid comparison of similar genomes | Moderate | Medium |

| KegAlign | GPU-accelerated diagonal partitioning | Large-scale analyses requiring speed | High (lastZ-level) | Moderate (6 hours for human-mouse on GPU) |

Alignment-Free Methods

Alignment-free methods have emerged as efficient alternatives for evolutionary distance estimation, particularly valuable for large-scale comparisons and database searches. These approaches typically employ k-mer-based sketching techniques, such as MinHash implemented in Mash and Dashing, which create compact representations of genomic sequences by storing subsets of their k-mers [9]. By comparing these sketches rather than full sequences, these tools can estimate evolutionary distances several orders of magnitude faster than alignment-based methods while maintaining strong correlation with traditional measures [9].

The KmerFinder tool exemplifies the specialized application of k-mer techniques for taxonomic classification, demonstrating how k-mer profiles can rapidly place unknown samples within evolutionary frameworks [9]. A significant advantage of k-mer-based approaches is their ability to handle incomplete or draft-quality genomes where alignment-based methods struggle with fragmentation and assembly artifacts. However, these methods rely on heuristics and may sacrifice some accuracy for speed, particularly at intermediate evolutionary distances where k-mer composition may not linearly correlate with true evolutionary divergence [9].

Synteny-Based Approaches

Synteny-based approaches represent a paradigm shift in identifying evolutionary relationships beyond sequence similarity. The Interspecies Point Projection (IPP) algorithm identifies orthologous genomic regions based on their relative position between conserved anchor points, independent of sequence conservation [11]. This method leverages syntenic relationships—the conservation of genomic colinearity—to identify functionally conserved regions even when sequences have diverged beyond the detection limits of alignment-based methods.

In comparative analyses between mouse and chicken hearts, IPP demonstrated remarkable utility, identifying five times more conserved regulatory elements than alignment-based approaches [11]. Whereas traditional LiftOver methods identified only 7.4% of enhancers as conserved between these species, IPP revealed that 42% of enhancers showed positional conservation despite sequence divergence [11]. This approach is particularly valuable for studying the evolution of regulatory elements, which often maintain function despite rapid sequence turnover. The method relies on high-quality genome assemblies and annotation of conserved anchor points, typically protein-coding genes with clear orthologous relationships, and benefits from including multiple bridging species to improve projection accuracy [11].

Experimental Protocols for Evolutionary Distance Analysis

Comparative Genomic Analysis Workflow

Diagram 1. Workflow for comprehensive evolutionary distance analysis integrating multiple methodological approaches.

Detailed Protocol: Whole-Genome Alignment with KegAlign

Objective: Perform sensitive pairwise whole-genome alignment for evolutionary distance calculation between mammalian species.

Sample Protocol (Human-Mouse Comparison):

- Data Preparation: Download reference genomes (hg38 human, mm39 mouse) from ENSEMBL or UCSC. Format sequences using

kegalign preprocessto ensure consistent formatting and remove ambiguous bases. - Anchor Point Identification: Identify syntenic anchor points using reciprocal BLAST with E-value threshold of 1e-10 and minimum alignment length of 100 bp. These anchors facilitate the diagonal partitioning strategy.

- GPU Configuration: Configure NVIDIA GPU with multi-instance GPU (MIG) and multi-process service (MPS) enabled to optimize hardware utilization. A minimum of 16GB GPU memory is recommended for mammalian genomes.

- Alignment Execution: Run KegAlign with species-appropriate parameters:

kegalign -t 32 --gpu-batch 8 -x human_mouse.xml hg38.fa mm39.fa -o output.maf. The tool employs diagonal partitioning to minimize tail latency issues common in highly similar genomes. - Post-processing: Filter alignments for minimum length (50 bp) and identity (30%) using

kegalign postprocess. Convert to phylogenetic format if needed for downstream analysis. - Distance Calculation: Calculate evolutionary distance using Jukes-Cantor correction:

d = -3/4 * ln(1 - 4/3 * p), where p is the observed proportion of differing sites in aligned regions [12].

This protocol reduces computational time from approximately 2,700 CPU hours with lastZ to under 6 hours on a single GPU-containing node while maintaining equivalent sensitivity [12].

Detailed Protocol: Synteny-Based Conservation Detection with IPP

Objective: Identify evolutionarily conserved regulatory elements between distantly related species despite sequence divergence.

Sample Protocol (Mouse-Chicken Heart Enhancer Conservation):

- Functional Genomic Data Collection: Generate or obtain chromatin profiling data (ATAC-seq, H3K27ac ChIP-seq) from equivalent developmental stages (mouse E10.5, chicken HH22) [11].

- CRE Identification: Predict cis-regulatory elements using CRUP from histone modifications, integrating with chromatin accessibility and gene expression data to minimize false positives.

- Bridge Species Selection: Curate 14 bridging species from reptilian and mammalian lineages with ancestral vertebrate genomes to serve as evolutionary intermediates.

- Anchor Point Definition: Identify alignable regions between all species pairs using lastZ with minimum match threshold of 0.1. These serve as reference points for interpolation.

- Interspecies Point Projection: Run IPP algorithm to project mouse CRE coordinates to chicken genome through bridged alignments:

ipp --bridges species_list.txt --min_anchors 3 --max_gap 2500 mouse_CREs.bed mouse_chicken.chain[11]. - Classification: Categorize projections as: (1) Directly Conserved (within 300 bp of direct alignment), (2) Indirectly Conserved (projected through bridged alignments with summed distance <2.5 kb), or (3) Non-conserved.

- Functional Validation: Select indirectly conserved enhancers for in vivo reporter assays in transgenic mouse models to confirm functional conservation [11].

This approach identified 42% of mouse heart enhancers as conserved in chicken (compared to 7.4% with alignment-based methods), dramatically expanding the detectable conserved regulome [11].

Research Reagent Solutions for Evolutionary Distance Studies

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Evolutionary Distance Analysis

| Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Alignment | lastZ, KegAlign, MUMmer | Generate base-level genome alignments | Pairwise whole-genome comparison, anchor identification |

| Sequence Similarity | OrthoANI, PyANI, FastANI | Calculate average nucleotide identity | Species delineation, phylogenetic framework construction |

| K-mer Analysis | Mash, Dashing, KmerFinder | Efficient genome sketching and comparison | Large-scale database searches, rapid phylogenetic placement |

| Synteny Analysis | IPP, Cactus, SynMap | Identify conserved genomic organization | Regulatory element evolution, deep evolutionary comparisons |

| Phylogenomics | OrthoFinder, NovelTree, IQ-TREE | Infer gene families and species trees | Evolutionary framework construction, orthology assignment |

| Functional Genomics | CRUP, MACS2, HOMER | Identify cis-regulatory elements | Functional element conservation analysis |

| Data Integration | Airbyte, Displayr, RStudio | Clean, transform, and analyze diverse datasets | Multi-omics data integration, reproducible analysis |

Data Presentation: Performance Comparison of Evolutionary Distance Methods

Table: Quantitative Performance Metrics for Evolutionary Distance Tools

| Method | Human-Mouse Runtime | Hardware Requirements | Sensitivity (Enhancer Detection) | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lastZ | ~2700 CPU hours | High-performance CPU cluster | 10% (alignment-based) | Excellent for highly divergent sequences | Extreme computational demands |

| KegAlign | <6 hours | Single GPU node | Equivalent to lastZ | GPU acceleration without sensitivity loss | Requires specialized hardware |

| Mash (k=21) | Minutes | Standard server | NA (alignment-free) | Extreme efficiency for large datasets | Indirect distance estimation |

| IPP Algorithm | Hours to days (including data generation) | CPU cluster with substantial memory | 42% (synteny-based) | Detects functional conservation beyond sequence similarity | Requires multiple bridging species |

The optimal choice of evolutionary distance methodology depends critically on research objectives, biological questions, and available computational resources. For maximum accuracy in closely related species or when precise nucleotide-level comparison is essential, alignment-based methods like ANIb provide the gold standard despite computational costs [9]. When studying deep evolutionary relationships or regulatory element conservation, synteny-based approaches like IPP reveal conserved elements invisible to sequence-based methods, expanding detectable conservation fivefold between mouse and chicken [11]. For large-scale comparative genomics or database screening, k-mer-based methods offer unparalleled efficiency with minimal sacrifice in accuracy [9].

The integration of GPU acceleration in tools like KegAlign demonstrates how algorithmic innovations can dramatically reduce computational barriers without sacrificing sensitivity [12]. Meanwhile, the recognition that sequence divergence often exceeds functional divergence—particularly for regulatory elements—underscores the importance of complementing traditional alignment methods with synteny-based and functional genomic approaches [11]. By strategically selecting and combining these approaches, researchers can leverage evolutionary distance not merely as a descriptive metric but as a powerful tool for selecting optimal species comparisons that maximize biological insights across the tree of life.

Table of Contents

- Introduction to the Functional Genome

- Benchmarking Genomic Analysis Models

- Experimental Protocols for Model Evaluation

- Pathways in Genomic Element Identification

- The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The completion of the Human Genome Project revealed that protein-coding genes comprise a mere 2% of our DNA [13]. The remaining majority, once dismissed as 'junk' DNA, is now understood to be a complex regulatory landscape essential for controlling gene expression [13]. This non-coding genome contains critical functional elements, including promoters, enhancers, insulators, and non-coding RNAs, which orchestrate when and where genes are activated or silenced [13] [14]. Disruptions in these regions are a major contributor to disease; over 90% of genetic variants linked to common conditions lie within these non-coding 'switch' regions [15]. Consequently, accurately identifying these functional elements is a fundamental goal in genomics, driving advances in precision medicine and drug discovery [13] [16].

The field has moved from analyzing isolated segments to understanding the genome as an integrated, three-dimensional structure. DNA is folded intricately inside the nucleus, bringing distant regulatory elements, such as enhancers and promoters, into close physical contact to control gene expression [15]. Mapping these long-range interactions, which can span millions of base pairs, is crucial for a complete understanding of genetic regulation [17]. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning have created powerful new models capable of predicting these complex sequence-to-function relationships, necessitating rigorous benchmarking to guide researchers in selecting the right tool for their specific needs [17] [18].

Benchmarking Genomic Analysis Models

To objectively evaluate the performance of modern genomic analysis tools, researchers have developed standardized benchmarks like DNALONGBENCH [17]. This suite tests models on five biologically significant tasks that require understanding dependencies across long DNA sequences—up to 1 million base pairs. The performance of various model types, including specialized "expert" models and more general-purpose "foundation" models, is compared quantitatively.

Table 1: Performance Summary of Model Types on DNALONGBENCH Tasks

| Model Type | Example Models | Key Characteristics | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Expert Models | ABC, Enformer, Akita, Puffin [17] | Highly specialized, task-specific architecture. | State-of-the-art performance on their designated tasks; superior at capturing long-range dependencies for complex regression (e.g., contact maps) [17]. | Narrow focus; cannot be easily applied to new tasks without retraining. |

| DNA Foundation Models | HyenaDNA, Caduceus [17] | Pre-trained on vast genomic data, then fine-tuned for specific tasks. | Good generalization; reasonable performance on certain classification tasks [17]. | Struggle with complex, multi-channel regression; fine-tuning can be unstable [17]. |

| Lightweight CNNs | 3-layer CNN [17] | Simple convolutional neural networks. | Simplicity and fast training; robust baseline for shorter-range tasks. | Consistently outperformed by expert and foundation models on long-range tasks [17]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Model Performance on Specific Genomic Tasks

| Task | Description | Expert Model (Score) | DNA Foundation Models (Score) | CNN (Score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhancer-Target Gene Prediction [17] | Classifies whether an enhancer regulates a specific target gene. | ABC Model (AUROC: 0.892) [17] | Caduceus-PS (AUROC: 0.816) [17] | CNN (AUROC: 0.774) [17] |

| Contact Map Prediction [17] | Predicts 3D chromatin interactions from sequence. | Akita (SCC: 0.856) [17] | Caduceus-PS (SCC: 0.621) [17] | CNN (SCC: 0.521) [17] |

| Transcription Initiation Signal Prediction [17] | Regression task to predict the location and strength of transcription start sites. | Puffin (Avg. Score: 0.733) [17] | Caduceus-PS (Avg. Score: 0.108) [17] | CNN (Avg. Score: 0.042) [17] |

| Regulatory Element Segmentation [19] | Nucleotide-level annotation of elements like exons and promoters. | SegmentNT (Avg. MCC: 0.42 on 10kb sequences) [19] | Nucleotide Transformer (Baseline for SegmentNT) [19] | Not Reported |

Another foundation model, OmniReg-GPT, demonstrates the value of efficient long-sequence training. When benchmarked on shorter regulatory element identification tasks (e.g., promoters, enhancers), it achieved superior Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) scores in 9 out of 13 tasks compared to other foundational models like DNABERT2 and Nucleotide Transformer [14].

Experimental Protocols for Model Evaluation

A critical step in comparing genomic tools is the use of standardized, rigorous experimental protocols. Below is a detailed methodology for a typical benchmarking study, as used in the evaluation of DNALONGBENCH [17].

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Long-Range Genomic Dependencies with DNALONGBENCH

- 1. Objective: To comprehensively evaluate the ability of computational models to capture long-range dependencies in DNA sequence for five key biological tasks.

- 2. Data Curation and Pre-processing:

- Data Sources: Genomic data is collected from public repositories such as ENCODE [17] [19]. For DNALONGBENCH, this includes Hi-C data for 3D genome organization, ChIP-seq and ATAC-seq data for regulatory elements, and RNA-seq data for expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs) [17].

- Sequence Extraction: Input sequences and their corresponding labels (e.g., contact frequencies, expression levels, element classifications) are extracted in windows of up to 1 million base pairs from the reference genome based on coordinates in BED format files [17].

- Dataset Splitting: Chromosomes are strategically partitioned into training, validation, and test sets (e.g., train on chromosomes 1-16, validate on 17-18, test on 19-22) to ensure no data leakage and robust performance evaluation [17] [19].

- 3. Model Selection and Training:

- Models: Three classes of models are selected:

- Expert Models: State-of-the-art models specifically designed for a single task (e.g., Akita for contact maps, Enformer for eQTLs) [17].

- DNA Foundation Models: General-purpose models pre-trained on large genomic corpora and then fine-tuned on each task (e.g., HyenaDNA, Caduceus) [17].

- Baseline CNN: A lightweight convolutional neural network provides a performance baseline [17].

- Fine-tuning/Training: Expert models are used as published. Foundation models are fine-tuned on each task's training set. The CNN is trained from scratch. Training uses task-appropriate loss functions (e.g., cross-entropy for classification, mean squared error for regression) [17].

- Models: Three classes of models are selected:

- 4. Performance Evaluation:

- Metrics: Models are evaluated on the held-out test set using task-specific metrics.

- Classification (e.g., Enhancer-Target): Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (AUROC) and Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPR) [17].

- Regression (e.g., Contact Map): Stratum-Adjusted Correlation Coefficient (SCC) and Pearson Correlation [17].

- Nucleotide-Level Segmentation (e.g., Element Annotation): Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC), F1-score, and Segment Overlap Score (SOV) [19].

- Analysis: Performance scores are aggregated and compared across model types and tasks to identify strengths and weaknesses.

- Metrics: Models are evaluated on the held-out test set using task-specific metrics.

Protocol 2: Nucleotide-Resolution Genome Annotation with SegmentNT

- 1. Objective: To train a model for annotating multiple genomic elements at single-nucleotide resolution by framing the problem as multilabel semantic segmentation [19].

- 2. Data Preparation:

- 3. Model Architecture and Training:

- Backbone: A pre-trained DNA foundation model (Nucleotide Transformer) serves as the encoder to generate initial sequence representations [19].

- Segmentation Head: A 1D U-Net architecture is attached to the backbone. It downscales and then upscales the representations to make a separate prediction for each element at each nucleotide position [19].

- Loss Function: A focal loss objective is used during training to handle the high class imbalance, as functional elements are sparse in the genome [19].

Pathways in Genomic Element Identification

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points for a researcher choosing a computational strategy to identify functional genomic elements, based on the benchmark data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The experiments and models discussed rely on a foundation of wet-lab techniques and computational resources. The following table details key reagents and tools essential for this field.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Genomic Studies

| Category | Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Assays | ATAC-seq [20] | Identifies regions of open chromatin, indicative of regulatory activity. | Used to validate that conserved non-coding sequences (CNS) are enriched in functionally accessible chromatin [20]. |

| ChIP-seq [20] | Maps the binding sites of specific proteins (e.g., transcription factors, histones) across the genome. | Profiling histone modifications (e.g., H3K9ac, H3K4me3) to characterize the epigenetic state of regulatory elements [20]. | |

| Hi-C [17] | Captures the 3D architecture of the genome by quantifying chromatin interactions. | Generating ground truth data for training and benchmarking models that predict 3D genome organization [17]. | |

| MCC ultra [15] | A high-resolution technique that maps chromatin structure down to a single base pair inside living cells. | Revealing the physical arrangement of gene control switches and how they form "islands" of activity [15]. | |

| Computational Tools & Data | Foundation Models (e.g., Nucleotide Transformer, OmniReg-GPT) [19] [14] | Provide pre-trained, general-purpose representations of DNA sequence that can be fine-tuned for diverse downstream tasks. | Serving as the backbone for SegmentNT for genome annotation or benchmarking for long-range task performance [19] [17]. |

| Benchmark Suites (e.g., DNALONGBENCH) [17] | Standardized datasets and tasks for the objective comparison of different genomic deep learning models. | Enabling rigorous evaluation of model performance on tasks like enhancer-target prediction and contact map modeling [17]. | |

| ENCODE / GENCODE Annotations [19] | Comprehensive, publicly available catalogs of functional elements in the human genome. | Providing the labeled data required to train supervised models like SegmentNT for genome annotation [19]. | |

| NCDC | NCDC | SMI | JNK Inhibitor | | NCDC is a cell-permeable JNK inhibitor for research into cancer, neurodegeneration & apoptosis. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

| E5,4 | E5,4 | Research Chemical | Supplier [Your Brand] | High-purity E5,4 for research applications. Explore its potential in biochemical studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. | Bench Chemicals |

Comparative genomics is the comparison of genetic information within and across species to understand the evolution, structure, and function of genes, proteins, and non-coding regions [21]. This scientific discipline provides powerful tools for systematically exploring biological relationships between species, aiding in understanding gene structure and function, and gaining crucial insights into human disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets [21]. The field has accelerated dramatically with advances in DNA sequencing technology, which have generated a flood of genomic data from diverse eukaryotic organisms [22]. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Comparative Genomics Resource (CGR) is a multi-year project implemented by the National Library of Medicine (NLM) to maximize the impact of eukaryotic research organisms and their genomic data resources to biomedical research [23] [22]. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of CGR against other essential model organism databases, offering performance data and experimental protocols to guide researchers in selecting appropriate resources for their comparative genomics studies.

The NIH CGR is designed as a comprehensive toolkit to facilitate reliable comparative genomics analyses for all eukaryotic organisms through community collaboration and interconnected data resources [23] [24]. CGR aims to maximize the biomedical impact of eukaryotic research organisms by providing high-quality genomic data, improved comparative genomics tools, and scalable analyses that support emerging big data approaches [23]. A key objective is the application of FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) principles to make genomic data more easily usable with standard bioinformatics platforms and tools [23]. The project is guided by two advisory boards: the NLM Board of Regents CGR working group comprising external biological leaders, and the CGR Executive Steering Committee providing NIH oversight [23].

CGR addresses several critical challenges in contemporary genomics research, including ensuring data quality, enhancing annotation consistency, and improving interoperability between resources [21]. The resource emphasizes connecting NCBI-held genomic content with community-supplied resources such as sample metadata and gene functional information, thereby amplifying the potential for new scientific discoveries [23] [21]. CGR's organism-agnostic approach provides equal access to datasets across the eukaryotic tree of life, enabling researchers to explore biological patterns and generate new hypotheses beyond traditional model organisms [23].

Established Model Organism Databases

Model organism databases (MODs) provide curated, species-specific biological data essential for biomedical research. These resources typically offer comprehensive genetic, genomic, phenotypic, and functional information focused on particular research organisms that serve as models for understanding biological processes relevant to human health. The National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) supports several key model organism databases that represent well-established species with extensive research histories [25].

Table 1: Key Model Organism Databases and Their Research Applications

| Database Name | Research Organism | Primary Research Applications | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| FlyBase [25] | Drosophila melanogaster (Fruit fly) | Genetics, developmental biology, neurobiology | Genetic and genomic data, gene expression patterns, phenotypic data |

| MGI [25] | Mus musculus (House mouse) | Human disease models, mammalian biology | Mouse genome database, gene function, phenotypic alleles |

| RGD [25] | Rattus norvegicus (Brown rat) | Cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders | Rat genome data, disease portals, quantitative trait loci (QTL) |

| WormBase [25] | Caenorhabditis elegans (Nematode) | Developmental biology, neurobiology, aging | Genome sequence, gene models, genetic maps, functional genomics |

| ZFIN [25] | Danio rerio (Zebrafish) | Developmental biology, toxicology, regeneration | Genetic and genomic data, gene expression, mutant phenotypes |

| SGD [25] | Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Baker's yeast) | Cell biology, genetics, functional genomics | Gene function, metabolic pathways, protein interactions |

These traditional model organisms were selected for biomedical research because they are typically easy to maintain and breed in laboratory settings and possess biological characteristics similar to human systems [22]. However, with advances in comparative genomics, emerging model organisms are increasingly being recognized for their potential to provide unique insights into specific biological processes and human diseases [22].

Performance Comparison: CGR vs. Specialized Model Organism Databases

Table 2: Performance Metrics and Capabilities Comparison Across Genomic Resources

| Feature | NCBI CGR | Specialized MODs | CGR Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Taxonomic Scope | All eukaryotic organisms [23] | Single species or related species [25] | Broader phylogenetic range for discovery |

| Data Integration | Integrates across multiple organisms and connects with community resources [23] [21] | Deep curation within single organism [25] | Enables cross-species comparisons and meta-analyses |

| Tool Availability | Eukaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline, Foreign Contamination Screen, Comparative Genome Viewer [22] | Organism-specific analysis tools and visualization [25] | Standardized tools applicable across diverse species |

| Data Quality Framework | Contamination screening, consistent annotation [23] [22] | Community-curated gene models and annotations [25] | Systematic quality control across all data |

| Computational Scalability | Support for big data approaches, AI-ready datasets, cloud-ready tools [23] | Varies by resource, typically single-organism focus | Designed for large-scale comparative analyses |

Quantitative assessments of genomic resource utility demonstrate that CGR's primary advantage lies in its cross-species interoperability and scalable infrastructure. For example, CGR facilitates the creation of AI-ready datasets and provides tools that maintain consistent annotation across diverse eukaryotic species, addressing a critical challenge in comparative genomics [23] [22]. While specialized model organism databases typically offer greater depth of curated information for specific organisms, CGR provides superior capabilities for researchers requiring cross-species comparisons or working with non-traditional research organisms.

Experimental Applications and Benchmarking

Key Research Applications of Comparative Genomics

Comparative genomics approaches have enabled significant advances across multiple biomedical research domains. The CGR project has identified several emerging model organisms with particular promise for illuminating specific biological processes relevant to human health [22]:

Pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus) for Xenotransplantation Research: Comparative genomic analyses have identified pigs as optimal donors for organ transplantation due to physiological and genomic similarities to humans. CGR resources facilitate the identification of genetic barriers to transplantation and potential engineering strategies [22].

Bats (Order Chiroptera) for Infectious Disease Studies: Various bat species exhibit unique immune adaptations that allow them to harbor viruses without developing disease. CGR enables comparative analysis of bat immune genes and pathways relevant to understanding viral transmission and host response [21].

Killifish (Nothobranchius furzeri) for Aging Research: These short-lived vertebrates exhibit rapid aging processes. Comparative genomics through CGR helps identify conserved genetic factors influencing longevity and age-related diseases [22].

Thirteen-Lined Ground Squirrels (Ictidomys tridecemlineatus) for Hibernation Studies: These mammals undergo profound metabolic changes during hibernation. CGR tools enable identification of genetic regulators of metabolic depression with potential applications for human metabolic disorders [22].

The CGR platform supports these research applications by providing integrated data and tools for comparing genomic features across species, identifying conserved elements, and analyzing lineage-specific adaptations [23] [21].

Benchmarking Methodologies for Genomic Tools

Rigorous benchmarking is essential for evaluating the performance of computational methods in genomics. Based on comprehensive assessments of benchmarking practices, several key methodological principles have been established [26] [27]:

Purpose and Scope Definition: Clearly define the benchmarking objectives, whether for method development, neutral comparison, or community challenge [27].

Comprehensive Method Selection: Include all relevant methods using predetermined inclusion criteria to avoid selection bias [27].

Diverse Dataset Selection: Utilize both simulated and experimental datasets that represent realistic biological scenarios and varying levels of complexity [27].

Appropriate Evaluation Metrics: Employ multiple performance metrics including accuracy, computational efficiency, scalability, and usability [26] [27].

A recent systematic review of single-cell benchmarking studies analyzed 282 papers and identified critical aspects of benchmarking methodology, including the importance of dataset diversity, method robustness assessment, and downstream evaluation [26]. These principles directly apply to evaluating genomic resources like CGR and model organism databases, where performance can be assessed based on data quality, annotation accuracy, tool interoperability, and user experience.

Diagram 1: Benchmarking workflow for genomic resources following established methodologies [26] [27].

Experimental Protocol for Comparative Genomics Analysis

A standardized protocol for conducting comparative genomics analyses using CGR and model organism databases ensures reproducible and biologically meaningful results:

Research Question Formulation: Clearly define the biological question and select appropriate comparator species based on evolutionary relationships or phenotypic traits.

Data Acquisition and Quality Control:

- Retrieve genome assemblies and annotations from CGR or relevant model organism databases

- Apply quality assessment metrics including completeness, contamination screening, and annotation consistency [22]

- Utilize CGR's Foreign Contamination Screen (FCS) tool to remove contaminated sequences prior to analysis [22]

Comparative Analysis Execution:

- Identify orthologous gene sets using reciprocal best hits or phylogenetic approaches

- Perform multiple sequence alignments of conserved genomic regions

- Utilize CGR's Comparative Genome Viewer (CGV) to visualize structural variations across species [22]

- Conduct evolutionary rate analyses (dN/dS) to identify signatures of selection

Functional Interpretation:

Validation and Follow-up:

- Design experimental validation based on computational predictions

- Utilize model organisms for functional testing of conserved genetic elements

- Iterate between computational and experimental approaches to refine biological models

This protocol leverages the complementary strengths of CGR's cross-species capabilities and the deep curation provided by specialized model organism databases to generate biologically insightful results.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Comparative Genomics

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Integrated Genomic Platforms | NIH CGR [23] | Provides eukaryotic genome data, annotation tools, and comparative analysis capabilities |

| Model Organism Databases | MGI, FlyBase, WormBase, ZFIN, RGD, SGD [25] | Species-specific genetic and genomic data with community curation |

| Reference Databases | UniProt KnowledgeBase [25] | Curated protein sequence and functional information |

| Pathway Resources | Reactome [25] | Curated resource of core pathways and reactions in human biology |

| Annotation Tools | Eukaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline [22] | Consistent genome annotation across eukaryotic species |

| Quality Control Tools | Foreign Contamination Screen (FCS) [22] | Detection and removal of contaminated sequences in genome assemblies |

| Visualization Tools | Comparative Genome Viewer (CGV) [22] | Visualization of genomic features and structural variations across species |

| Data Retrieval Systems | NCBI Datasets [22] | Programmatic access to genome-associated data and metadata |

These essential resources provide the foundation for rigorous comparative genomics studies. The CGR project enhances interoperability between these tools, creating a more connected ecosystem for genomic research [23] [21]. For example, CGR facilitates connections between NCBI resources and community databases, enabling researchers to move seamlessly between cross-species comparisons and deep dives into organism-specific biology.

Diagram 2: CGR integration in the biomedical research workflow, showing inputs from various genomic data sources and outputs to key research applications [23] [21].

The NIH Comparative Genomics Resource represents a significant advancement in genomic data integration and analysis capabilities, complementing existing model organism databases by enabling cross-species comparisons and discovery across the eukaryotic tree of life. While specialized model organism databases continue to provide essential depth for particular research organisms, CGR offers unique strengths in taxonomic breadth, tool interoperability, and support for large-scale comparative analyses.

Future developments in comparative genomics will likely focus on enhancing data integration across resources, improving scalability for increasingly large datasets, and developing more sophisticated analytical methods for extracting biological insights from cross-species comparisons [23] [21]. The CGR project is positioned to address these challenges through its ongoing development of improved tools, community engagement initiatives, and commitment to FAIR data principles [23]. As comparative genomics continues to evolve, resources like CGR and specialized model organism databases will play complementary roles in enabling biomedical researchers to translate genomic information into improved understanding of human health and disease.

For researchers embarking on comparative genomics studies, the selection of resources should be guided by specific research questions: specialized model organism databases for depth within established models, and CGR for breadth across diverse eukaryotes and integrated analysis capabilities. Engaging with both types of resources through CGR's connectivity framework provides the most comprehensive approach to addressing complex biological questions through comparative genomics.

Methodological Workflows and Their Transformative Applications in Biomedicine

Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Annotation Pipelines

Genome analysis pipelines have evolved into sophisticated workflows that integrate diverse sequencing technologies, computational assembly tools, and annotation algorithms. The choice of pipeline components significantly impacts the final output quality, with long-read technologies now enabling telomere-to-telomere assemblies and pangenome references that capture global genetic diversity. This guide objectively compares the performance of leading tools and technologies based on recent experimental benchmarks, providing researchers with evidence-based selection criteria for their genomic investigations.

Sequencing Technologies: Landscape and Performance

Technology Comparison and Selection Criteria

Table 1: Comparison of Modern DNA Sequencing Technologies (2025)

| Technology | Read Length | Accuracy | Key Strengths | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PacBio HiFi | >15 kb | >99.9% [28] | Ultra-high accuracy, haplotype phasing | Structural variant detection, genome finishing [28] |

| Oxford Nanopore (UL) | >100 kb | ~99% [29] | Ultra-long reads, real-time analysis | Complex SV resolution, base modification detection [30] |

| Illumina NovaSeq X | 200-300 bp | >99.9% [28] | High throughput, low cost | Variant discovery, population sequencing |

| Element AVITI | 300 bp | Q40 [28] | Benchtop flexibility, high accuracy | Targeted sequencing, clinical applications |

| Roche SBX* | N/A | High (CMOS) | Rapid turnaround, Xpandomer chemistry | High-throughput genomics [28] |

| MGI DNBSEQ | Varies | High | Cost-effective, AI-enhanced | Population screening, point-of-care [28] |

*Scheduled for 2026 release [28]

Experimental Evidence and Performance Metrics

Recent large-scale studies demonstrate that technology selection directly impacts assembly quality. Research sequencing 65 diverse human genomes achieved 130 haplotype-resolved assemblies with a median continuity of 130 Mb by combining PacBio HiFi (~47x coverage) with Oxford Nanopore ultra-long reads (~36x coverage) [29]. This hybrid approach enabled:

- Telomere-to-telomere (T2T) status for 39% of chromosomes [29]

- 92% gap closure compared to previous assemblies [29]

- Resolution of 1,852 complex structural variants and 1,246 centromeres [29]

Genome Assembly Tools: Benchmarking and Protocols

Assembly Algorithm Performance Comparison

Table 2: Benchmarking of Genome Assembly Tools (2025 Data)

| Assembler | Contiguity (N50) | Completeness (BUSCO) | Runtime Efficiency | Misassembly Rate | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NextDenovo | High | Near-complete [31] | Stable | Low [31] | Large eukaryotic genomes |

| NECAT | High | Near-complete [31] | Efficient | Low [31] | Prokaryotic & eukaryotic |

| Flye | High [32] | Complete | Moderate | Sensitive to input [31] | Balanced accuracy/contiguity |

| Unicycler | Lower than Flye [31] | Complete | Moderate | Low | Hybrid assembly [32] |

| Canu | Moderate (3-5 contigs) [31] | High | Longest runtime [31] | Low | Accuracy-critical projects |

| Verkko | 130 Mb (median) [29] | 99% complete [29] | N/A | Low | Haplotype-resolved diploid |

| hifiasm (ultra-long) | Comparable to Verkko [29] | High [29] | N/A | Low | Complex SV resolution |

Experimental Protocols for Assembly Benchmarking

Methodology from Recent Assembly Studies:

- Data Input Standardization: Assemblers were tested using standardized computational resources with identical preprocessing [31]

- Evaluation Metrics: Contiguity (N50, total length, contig count), GC content, and completeness using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) [31]

- Quality Control: Integration of Flagger, NucFreq, Merqury, and Inspector for robust error estimates [29]

- Phasing Validation: For diploid assemblies, parental support verification via assembly-to-assembly alignments (median 99.9% support achieved) [29]

Key Finding: Preprocessing strategy significantly impacts output quality. Filtering improved genome fraction and BUSCO completeness, while correction benefited overlap-layout-consensus (OLC) assemblers but occasionally increased misassemblies in graph-based tools [31].

Figure 1: Genome Analysis Pipeline Workflow showing technology and tool integration points

Genome Annotation: Precision and Accuracy Assessment

Annotation Tool Performance Metrics

Evidence from Recent Comparative Studies:

- Error Rates: Automated annotation tools exhibit measurable error rates, with RAST (2.1%) and PROKKA (0.9%) wrongly annotating coding gene sequences [32]

- Error Patterns: Misannotations frequently associate with shorter coding sequences (<150 nt) involving transposases, mobile genetic elements, and hypothetical proteins [32]

- Completeness: Modern eukaryotic genome annotations achieve >99% completeness for known single-copy genes when using integrated approaches [29]

Annotation Methodologies and Protocols

Braker3 Protocol (Evidence-Based):

- Input Requirements: Genome sequence, RNA-seq alignments (BAM format), and curated protein sequences (e.g., UniProt/SwissProt) [33]

- Methodology: Integrates GeneMark-ETP and AUGUSTUS using transcriptomic and protein evidence [33]

- Critical Parameter: RNA-seq alignment must include

--outSAMstrandField intronMotiffor proper intron information [33]

Helixer Protocol (Deep Learning-Based):

- Input Requirements: Only genome sequence required [33]

- Methodology: Cross-species deep learning model predicting gene structures without external evidence [33]

- Lineage Selection: Four predefined models (invertebrate, vertebrate, land plant, fungi) optimized for each lineage [33]

Table 3: Annotation Tool Comparison and Error Analysis

| Annotation Tool | Approach | Evidence Requirements | Error Rate | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Braker3 | Evidence-based | RNA-seq, protein sequences [33] | Not quantified | High precision with extrinsic support [33] | Dependent on quality of input evidence |

| Helixer | Deep learning | None (ab initio) [33] | Not quantified | Rapid execution, no evidence needed [33] | Limited to four predefined lineages |

| RAST | Automated | None | 2.1% [32] | Comprehensive pipeline | Higher error rate for short CDS |

| PROKKA | Automated | None | 0.9% [32] | Prokaryote-optimized | Higher error rate for short CDS |

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Genome Analysis Pipelines

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| PacBio SMRT cells | HiFi read generation | Long-read sequencing | >15 kb reads, >99.9% accuracy [28] |

| Oxford Nanopore flow cells | Ultra-long read generation | Structural variant resolution | PromethION (200 Gb/output) [28] |

| Strand-seq libraries | Global phasing information | Haplotype resolution [29] | Chromosome-specific phasing |

| Hi-C sequencing kits | Chromatin interaction data | Scaffolding, phase separation [29] | Proximity ligation-based |

| Bionano optics chips | Optical mapping | Scaffold validation [29] | Large molecule imaging |

| RNA STAR aligner | Transcriptome alignment | Evidence-based annotation [33] | Requires specific strand parameters |

| UniProt/SwissProt | Curated protein sequences | Protein evidence for annotation [33] | Manually reviewed sequences |

| BUSCO datasets | Completeness assessment | Assembly/annotation QC [31] | Universal single-copy orthologs |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of genome analysis is rapidly evolving with several significant developments:

Pangenome References: The construction of diverse reference sets from 65 individuals enables capturing essential variation explaining differential disease risk across populations [30]. This approach has increased structural variant detection to 26,115 per individual, dramatically expanding variants available for disease association studies [29].

Complex Variant Resolution: Recent studies have completely resolved previously intractable regions including:

- Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) linked to cancer and autoimmune diseases [30]

- SMN1/SMN2 region target for spinal muscular atrophy therapies [30]

- Centromeres with up to 30-fold variation in α-satellite arrays [29]

Methodological Innovations: Current research focuses on overcoming persistent challenges in assembling ultra-long tandem repeats, resolving complex polyploid genomes, and complete metagenome assembly through improved alignment algorithms, AI-driven assembly graph analysis, and enhanced metagenomic binning techniques [34].

Figure 2: Current Challenges and Emerging Solutions in Genome Assembly

Based on current experimental evidence, pipeline selection should be guided by research objectives:

For Complete Eukaryotic Genomes: Hybrid assembly with PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore ultra-long reads using Verkko or hifiasm, followed by evidence-based annotation with Braker3 provides the most comprehensive results [29].

For Prokaryotic Genomes: Long-read assemblers like NextDenovo or Flye offer optimal balance of accuracy and contiguity, with PROKKA providing efficient annotation despite measurable error rates in shorter CDS [32] [31].

For Population Studies: Pangenome graphs incorporating diverse assemblies now enable structural variant association studies at unprecedented scale, significantly advancing equity in genomic medicine applications [30] [29].

The continuous innovation in sequencing technologies and computational methods promises further improvements in resolution, accuracy, and inclusivity of genome analysis pipelines, with emerging capabilities to fully resolve remaining difficult genomic regions including centromeres and highly identical segmental duplications.

Comparative genomics provides fundamental insights into evolutionary biology, functional genetics, and disease mechanisms by analyzing genomic sequences across different species and strains. As sequencing technologies advance, generating unprecedented volumes of genomic data, the computational methods for comparing these genomes have become increasingly sophisticated. This review objectively compares three cornerstone methodologies in modern comparative genomics: whole-genome alignment, ortholog identification, and pangenome analysis. Each approach addresses distinct biological questions while facing unique computational challenges related to scalability, accuracy, and interpretability. We examine recent algorithmic advances that enhance processing efficiency without sacrificing precision, focusing on performance benchmarks from experimental evaluations. The integration of these methodologies enables researchers to trace evolutionary trajectories, infer gene function, and understand the genetic basis of adaptation across the tree of life.

Whole-Genome Alignment Methods

Whole-genome alignment (WGA) establishes base-to-base correspondence between entire genomes, enabling the detection of large-scale structural variations and evolutionary conservation patterns. WGA algorithms can be broadly classified into four categories: suffix tree-based, hash-based, anchor-based, and graph-based methods, each with distinct computational strategies for handling genomic scale and complexity [35].

Suffix tree-based methods, exemplified by the MUMmer suite, utilize data structures that represent all suffixes of a given string to identify maximal unique matches (MUMs) between genomes [35]. MUMmer's algorithm first performs a MUM decomposition to identify subsequences that occur exactly once in both genomes, then filters spurious matches, organizes remaining MUMs by their conserved order, fills gaps between MUMs with local alignment, and finally produces a comprehensive genome alignment [35]. This approach provides exceptional accuracy for identifying conserved regions but faces memory constraints with larger genomes due to suffix tree construction requirements.

Anchor-based methods identify conserved regions ("anchors") between genomes and build alignments around these regions, while hash-based methods use precomputed k-mer tables to efficiently locate potential alignment seeds. Graph-based methods represent genome relationships as graphs, offering flexibility for capturing complex evolutionary events including rearrangements, but requiring substantial computational resources [35].

The choice between WGA algorithms depends heavily on read type applications. Short reads (100-600 bp) benefit from tools like BOWTIE2 and BWA that optimize for high precision in mapping, whereas long reads (extending to thousands of bp) require specialized tools like Minimap2 that can handle higher error rates while resolving complex genomic architectures [35].

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Major WGA Algorithm Categories

| Algorithm Type | Representative Tools | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Suffix Tree-Based | MUMmer | High accuracy for conserved regions; Efficient MUM identification | Memory-intensive for large genomes |

| Hash-Based | BWA, BOWTIE2 | Optimized for short reads; High precision for small variants | Struggles with complex genomic regions |

| Anchor-Based | Minimap2 | Effective for long reads; Handles structural variants | Higher error rate tolerance needed |

| Graph-Based | SibeliaZ, BubbZ | Captures complex evolutionary events | Computationally demanding |

Figure 1: Classification of whole-genome alignment methodologies showing four computational approaches for comparing complete genomes.

Ortholog Identification Approaches

Orthologs are genes diverging after a speciation event, making their accurate identification crucial for functional annotation transfer and evolutionary studies. Orthology inference methods face substantial computational challenges with the expanding repertoire of sequenced genomes, necessitating scalable solutions that maintain precision.

NCBI Orthologs Methodology

The NCBI Orthologs resource implements a high-precision pipeline integrating multiple evidence types to identify one-to-one orthologous relationships across eukaryotic genomes. This approach combines protein sequence similarity, nucleotide alignment conservation, and microsynteny information to resolve complex evolutionary relationships [36]. The pipeline processes genomes individually, ensuring scalability across the expanding RefSeq database.

The method begins with all-against-all protein comparisons using DIAMOND (BLASTP-like alignment scores), selecting the best protein isoform pairs based on a modified Jaccard index that normalizes alignment scores against potential maximum similarity [36]. For candidate pairs, the pipeline evaluates nucleotide-level conservation by aligning concatenated exonic sequences with flanking regions using discontiguous-megablast, again applying a modified Jaccard index. Finally, microsynteny conservation is assessed by counting homologous gene pairs within a 20-locus window surrounding the candidate genes [36]. The integration of these metrics enables the algorithm to identify true orthologs amidst complex gene families, particularly when microsynteny evidence is present.

FastOMA Algorithm

FastOMA addresses critical scalability limitations in orthology inference through a complete algorithmic redesign of the established Orthologous Matrix (OMA) approach. It achieves linear time complexity through k-mer-based homology clustering, taxonomy-guided subsampling, and parallel computing architecture [37]. This enables processing of 2,086 eukaryotic proteomes in under 24 hours using 300 CPU cores - a dramatic improvement over original OMA (50 genomes in same timeframe) and outperforming other contemporary tools like OrthoFinder and SonicParanoid that exhibit quadratic scaling [37].

The algorithm employs a two-stage process: first, identifying root hierarchical orthologous groups (HOGs) via OMAmer placement and Linclust clustering; second, inferring nested HOG structures through leaf-to-root species tree traversal [37]. Benchmarking on Quest for Orthologs references demonstrates FastOMA maintains high precision (0.955 on SwissTree) with moderate recall, positioning it on the Pareto frontier of orthology inference methods [37]. The method also incorporates handling of alternative splicing isoforms and fragmented gene models, further enhancing its practical applicability to diverse genomic datasets.

Table 2: Orthology Inference Tool Performance Benchmarks

| Method | Precision (SwissTree) | Recall (SwissTree) | Time Complexity | Scalability (Genomes in 24h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastOMA | 0.955 | 0.69 | Linear | 2,086 |

| OMA | 0.945 | 0.65 | Quadratic | 50 |

| OrthoFinder | 0.925 | 0.75 | Quadratic | ~500 |

| SonicParanoid | 0.910 | 0.72 | Quadratic | ~600 |

| NCBI Orthologs | Not reported | Not reported | Near-linear | Not reported |

Figure 2: Ortholog identification workflows comparing the scalable FastOMA approach with the evidence-integration strategy of NCBI Orthologs.

Pangenome Analysis Frameworks

Pangenome analysis characterizes the total gene repertoire within a taxonomic group, distinguishing core genes (shared by all individuals) from accessory genes (variable presence). This approach reveals evolutionary dynamics, adaptation mechanisms, and genetic diversity patterns across populations.

PGAP2 Toolkit

PGAP2 represents a significant advancement in prokaryotic pangenome analysis, integrating quality control, ortholog identification, and visualization in a unified toolkit. Designed to process thousands of genomes, it employs a dual-level regional restriction strategy for precise ortholog inference [38]. The workflow begins with format-flexible input processing (GFF3, GBFF, FASTA), followed by automated quality control that identifies outlier strains based on average nucleotide identity (ANI < 95%) or unique gene content [38].

Ortholog identification in PGAP2 utilizes fine-grained feature analysis within constrained genomic regions. The system constructs two network representations: a gene identity network (edges represent similarity) and a gene synteny network (edges represent gene adjacency) [38]. Through iterative regional refinement, PGAP2 evaluates clusters using gene diversity, connectivity, and bidirectional best hit criteria while employing conserved gene neighborhoods to ensure acyclic graph structures. This approach specifically addresses challenges in clustering mobile genetic elements and paralogs that complicate simpler methods.

Validation on simulated datasets demonstrates PGAP2's superior accuracy in ortholog/paralog distinction compared to existing tools, particularly under conditions of high genomic diversity [38]. The toolkit additionally introduces four quantitative parameters derived from inter- and intra-cluster distances, enabling statistical characterization of homology clusters beyond qualitative descriptions. Application to 2,794 Streptococcus suis strains illustrates PGAP2's practical utility in revealing population-specific genetic adaptations in a zoonotic pathogen [38].

Table 3: Pangenome Analysis Method Categories and Capabilities

| Method Category | Representative Tools | Typical Application Scale | Ortholog Determination Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference-Based | eggNOG, COG | Dozens of genomes | Database homology searching |

| Graph-Based | PGAP2 | Thousands of genomes | Identity/synteny network clustering |

| Phylogeny-Based | OrthoFinder, OMA | Hundreds of genomes | Phylogenetic tree reconciliation |

| kn-92 | KN-92|CaMKII Inactive Control | KN-92 is an inactive analog of KN-93, used as a negative control in CaMKII research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or diagnostic use. | Bench Chemicals |

| CTOP TFA | CTOP TFA, CAS:103429-31-8, MF:C50H67N11O11S2, MW:1062.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

Orthology Benchmarking Standards

Orthology inference tools are typically evaluated using the Quest for Orthologs (QfO) benchmark suite, which includes reference datasets like SwissTree containing curated gene phylogenies with validated orthologous relationships [37]. Performance is measured by precision (fraction of predicted orthologs that are true orthologs) and recall (fraction of true orthologs successfully detected). FastOMA achieved a precision of 0.955 and recall of 0.69 on this benchmark, outperforming most state-of-the-art methods on precision while maintaining moderate recall [37].

The generalized species tree benchmark evaluates how well inferred gene trees match expected species phylogenies using normalized Robinson-Foulds distances. FastOMA achieved a distance of 0.225 at the Eukaryota level, indicating high topological concordance with reference evolutionary histories [37].

Pangenome Validation Methods

PGAP2 validation employs both simulated datasets with known orthology/paralogy relationships and gold-standard curated genomes. Performance metrics include clustering accuracy, robustness to evolutionary distance variation, and scalability with increasing genome numbers [38]. On simulated data, PGAP2 maintained stable performance across different ortholog/paralog thresholds, demonstrating particular strength in distinguishing recent gene duplications - a challenging scenario for many alternative methods [38].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Comparative Genomics

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| DIAMOND | Protein sequence similarity search | NCBI Orthologs pipeline for initial homology detection |

| OMAmer | k-mer-based protein placement | FastOMA root HOG identification |

| Linclust | Highly scalable sequence clustering | FastOMA clustering of unplaced sequences |

| Discontiguous Megablast | Nucleotide alignment of divergent sequences | NCBI Orthologs exon-based conservation analysis |

| PGAP2 | Pangenome analysis and visualization | Prokaryotic pangenome construction and quantification |

| MUMmer | Whole-genome alignment using suffix trees | Global genome comparison and alignment |

| Minimap2 | Long-read alignment and comparison | WGA of Oxford Nanopore/PacBio data |

Integrated Workflow and Future Directions

The integration of whole-genome alignment, ortholog identification, and pangenome analysis creates a powerful framework for comparative genomics. WGA provides the structural context for understanding genome evolution, orthology inference enables functional comparisons across taxa, and pangenome analysis reveals population-level diversity patterns. Together, these approaches facilitate comprehensive studies of gene family evolution, adaptive mechanisms, and phylogenetic relationships.

Future methodological development will likely focus on enhanced scalability to accommodate exponentially growing genomic datasets, with approaches like FastOMA's linear-time algorithms setting new standards. Integration of additional data types, particularly structural protein information and three-dimensional chromatin architecture, promises to improve orthology resolution at deeper evolutionary levels [37]. For pangenome analysis, quantitative characterization of gene clusters - as implemented in PGAP2 - represents a shift from qualitative to statistical frameworks for understanding gene evolutionary dynamics [38].

As these methodologies continue to mature, their convergence will enable increasingly comprehensive reconstructions of evolutionary history, functional constraint, and adaptive mechanisms across the tree of life. The development of standardized benchmarks, such as those provided by the Quest for Orthologs initiative, ensures objective performance assessment and method refinement, ultimately advancing the field of comparative genomics.