Computational Biology Careers in 2025: A Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigating careers in computational biology.

Computational Biology Careers in 2025: A Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigating careers in computational biology. It explores the foundational distinctions between key roles like Computational Biologist and Bioinformatics Analyst, details the in-demand technical and biological skills for 2025, and addresses real-world challenges from AI integration to data management. The guide also offers practical strategies for skill validation, career advancement, and leveraging computational biology to drive innovation in biomedical research and therapeutic development.

What is Computational Biology? Defining the Field and Its Core Careers

The modern computational biologist operates at the converging front of biological research, data science, and software engineering. This role has evolved from merely running standardized software to being an integral scientist who designs analytical strategies, interprets complex data, and derives biologically meaningful conclusions [1]. They are characterized by their ability to manage and interpret massive, complex datasets—from genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics—to unlock secrets of life and disease [2]. This transformation is driven by the surge in data scale and complexity, demanding sophisticated data science approaches to dissect cellular processes quantitatively [3]. The core of the role is the translation of data into biological understanding, a process that involves as much detective work and critical thinking as it does coding [1].

The Essential Skill Set: A Multidisciplinary Toolkit

The proficiency of a computational biologist rests on a foundation of interdisciplinary skills. The most in-demand professionals are those who can blend strong biological expertise with advanced computational techniques [4].

Table 1: Core Competencies for the Modern Computational Biologist

| Skill Category | Specific Skills & Tools | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Programming & Data Handling | Python, R, UNIX/Linux shell scripting [5] [3] [1] | Automating data analysis, creating plots, building reproducible pipelines, and handling large datasets. |

| NGS Data Analysis | Processing FASTQ files; using tools like GATK, STAR, HISAT2; interpreting RNA-seq, ChIP-seq, single-cell, and spatial transcriptomics data [5] [4] | Central to genomics, cancer research, and identifying genetic variations or gene expression patterns. |

| Data Science & Machine Learning | scikit-learn, TensorFlow, PyTorch; applying ML to genomics for biomarker and drug response prediction [5] [4] | Building models to predict protein structures, discover biomarkers, and summarize functional analysis beyond traditional methods. |

| Cloud Computing & Big Data | AWS, Google Cloud, Azure [5] [4] | Enabling scalable data storage, management, and analysis for large-scale projects and global collaborations. |

| Biological Domain Knowledge | Molecular biology, genetics, cancer biology, systems biology [5] [4] | Providing essential context to computational results, formulating biologically relevant questions, and sanity-checking outputs. |

| Scientific Communication | Communicating complex data to non-technical stakeholders, collaborating with clinicians and wet-lab researchers [5] [2] | Explaining results, collaborating effectively, contributing to publications, and ensuring research has real-world impact. |

A key theme is that while AI streamlines coding tasks, biological understanding is more critical than ever to guide analysis and interpretation. It is often more effective to train a biologist in computational methods than to instill deep biological expertise in someone from a purely computational background [4].

The Research Reagent Toolkit: Essential Materials and Solutions

In computational biology, the "research reagents" are the software tools, databases, and packages that enable the analysis of biological data.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Biology

| Item | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Bioconductor | An open-source software project providing tools for the analysis and comprehension of high-throughput genomic data [2]. | Used for building custom integrated analysis packages for transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics data [2]. |

| Genome Analysis Toolkits (e.g., GATK) | A structured software library for developing tools that analyze high-throughput sequencing data [5]. | The industry standard for variant discovery in sequencing data, such as identifying SNPs and indels. |

| Single-Cell RNA-Seq Packages (e.g., for R) | Specialized software packages designed to process and analyze gene expression data from individual cells [3]. | Uncovering cell heterogeneity, identifying rare cell types, and tracing developmental trajectories. |

| AI and Protein Language Models (PLMs) | AI models trained on protein sequences to understand the language of proteins and predict structures and functions [4]. | Predicting protein structures and their interactions with other molecules, upending small-molecule discovery pipelines [4]. |

| Version Control (Git) | A system for tracking changes in code and collaborative development [1]. | Essential for reproducibility, documenting the analytical journey, and collaborating on code. |

From Data to Insight: Core Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The computational biologist's work is governed by rigorous, reproducible protocols that transform raw data into reliable insights.

A Generalized High-Throughput Data Analysis Protocol

The following workflow, adaptable for various 'omics' data types like transcriptomics, provides a structured approach from raw data to biological insight [2].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Raw Data Acquisition and Management: Begin by collecting raw data files (e.g., FASTQ for sequencing) from core facilities or public repositories. Implement a consistent naming convention and directory structure. Track all associated metadata—including biological conditions, repeat numbers, and instrument settings—from the start, as this is crucial for understanding variability and ensuring reproducibility [3].

- Quality Control (QC) & Pre-processing: Use tools like FastQC for sequencing data to assess read quality, adapter contamination, and GC content. Perform trimming or filtering to remove low-quality sequences. This step ensures that subsequent analysis is not biased by technical artifacts.

- Alignment & Quantification: Map processed reads to a reference genome or transcriptome using appropriate aligners (e.g., STAR for RNA-seq, HISAT2 for alignment). The output is typically a count or expression matrix, where rows represent features (e.g., genes) and columns represent samples [2].

- Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA): This is a critical, flexible phase for understanding the data. Use programming languages like R or Python to generate visualizations such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plots and heatmaps. EDA helps uncover trends, identify outliers, assess biological variability between repeats, and refine hypotheses [3]. SuperPlots are particularly useful for visualizing data from biological repeats together to assess reproducibility [3].

- Statistical Analysis & Modeling: Apply statistical tests to answer specific biological questions. For transcriptomics, this involves testing for differential expression between conditions. Increasingly, this step incorporates machine learning models to classify samples or predict outcomes based on molecular features [5] [4].

- Functional Interpretation: Translate statistical results (e.g., lists of differentially expressed genes) into biological meaning using enrichment analysis for pathways (e.g., KEGG, Reactome) or Gene Ontology (GO) terms. The future points towards AI-based functional summaries superseding traditional hypergeometric tests [4].

- Biological Validation & Sanity Checking: The final, non-negotiable step is to ask, "Does this make biological sense?" [1]. Computational findings must be interpreted in the context of existing literature and biological ground truth. This may involve designing follow-up wet-lab experiments or cross-validating with different computational methods.

Data Exploration and Sanity Checking Workflow

A robust data exploration practice is what separates a scientist from a coder. The following logic flow should be applied throughout the analytical process.

Key Practices for the Workflow:

- Never Just Run Tools—Understand Them: "Would you run PCR without knowing primers? Same with bioinformatics—know the assumptions" [1]. Understand the algorithms, as the choice between a De Bruijn graph (for short reads) and Overlap-Layout-Consensus (for long reads) fundamentally shapes your results in genome assembly [1].

- Validate, Always: Test your pipelines on smaller datasets with known answers. Cross-check critical results with a different analytical method or tool. "Don't trust a single output blindly" [1].

- Embrace Sanity Checking: "Computers don't care about truth. They'll return output even if it's nonsense. Your job is to sanity-check" [1]. Skepticism is a superpower in a field where random noise can look like a signal [1].

Career Trajectory and Future Outlook

The career path for a computational biologist is built on continuous learning and adapting to new technological landscapes. A typical path often involves advanced degrees (Master's, PhD) and postdoctoral research, with roles spanning academia, government research institutes (e.g., ICMR), and the biopharmaceutical industry [2]. The future outlook for the field is tightly coupled with several key advancements:

- AI and Precision Medicine: AI is poised to upend discovery pipelines, with tools like AlphaFold 3 impacting small molecule discovery. The field will see more integration of large-scale population genomics with clinical data to match patients to treatments based on genetic alterations, as seen in precision medicine trials for cancer [4].

- The Shift in the Bioinformatician's Role: As AI automates more coding tasks, the computational biologist's role will evolve to become more focused on biological interpretation, experimental design, and asking the right questions, rather than on the mechanics of coding [4].

- Community and Continuous Learning: "Find your people" on platforms like BioStars and SEQanswers [1]. Building a toolbox of skills and engaging with the community are essential for growth and staying current in this rapidly evolving field [1] [2].

In the data-driven landscape of modern biological research, computational biology and bioinformatics represent two distinct but deeply interconnected disciplines. Both fields apply computational methods to biological questions but differ in their primary focus, methodological approaches, and output. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding this distinction is crucial for building effective research teams and advancing scientific discovery.

Computational Biology is fundamentally concerned with model-building and theoretical exploration of biological systems. It employs mathematical models, computational simulations, and statistical inference to understand complex biological systems and formulate testable hypotheses [6] [7]. The computational biologist is often focused on the "big picture" of what is happening biologically [6].

Bioinformatics, in contrast, is primarily focused on the development and application of computational tools to manage and interpret large, complex biological datasets [6] [7]. It is an engineering-oriented discipline that creates the pipelines and methods necessary to transform raw data into structured, analyzable information [8].

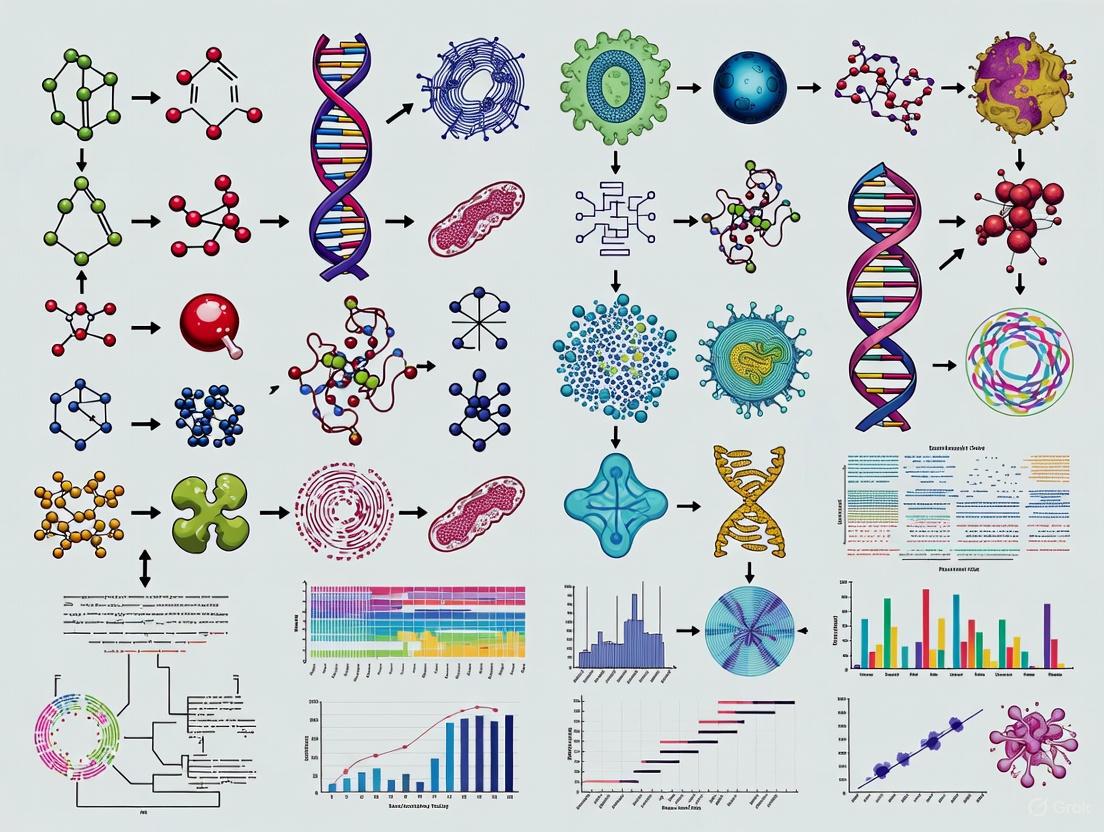

The following diagram illustrates the core workflows and primary outputs that distinguish these two fields.

Core Responsibilities: A Detailed Comparison

The day-to-day responsibilities of Computational Biologists and Bioinformatics Analysts reflect their different orientations toward data and biological theory.

Primary Responsibilities of a Bioinformatics Analyst

A Bioinformatics Analyst serves as the crucial bridge between raw data and initial biological interpretation [8]. Their work is characterized by the application and execution of established computational tools.

- Data Processing and Quality Control: They manage and process large, high-throughput biological datasets, such as those from next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms, ensuring data integrity and quality [9] [8]. This includes running quality control tools like FASTQC and processing raw sequence data through alignment tools (HISAT2, STAR) [9].

- Pipeline Implementation and Execution: A core duty is the implementation, maintenance, and execution of bioinformatics pipelines for standardized analyses like RNA-Seq, variant calling (using tools like GATK), and differential gene expression analysis (e.g., with DESeq2) [9] [8].

- Data Visualization and Reporting: They generate analytical reports and data visualizations to summarize findings for collaborators and research teams, often using plotting libraries like ggplot2 (R) or matplotlib/seaborn (Python) [9] [8].

Primary Responsibilities of a Computational Biologist

A Computational Biologist leverages processed data to explore deeper biological mechanisms and principles, often through the creation of new methods and models [10] [8].

- Algorithm and Model Development: They design and develop novel algorithms, statistical models, and computational simulations to understand biological systems, such as gene regulatory networks or protein interaction dynamics [10] [8] [7].

- Systems-Level Data Integration and Hypothesis Generation: They integrate diverse, large-scale data types (genomics, proteomics, imaging, clinical data) to form a systems-level understanding and generate new biological hypotheses [8].

- Theoretical Research and Discovery: Their work is often directed toward publishing new computational methods in peer-reviewed literature or making novel biological discoveries based on computational insights [8] [11]. They use tools like molecular dynamics simulations and agent-based modeling to simulate and predict system behavior [7].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Core Responsibilities

| Responsibility Area | Bioinformatics Analyst | Computational Biologist |

|---|---|---|

| Data Focus | Large-scale, raw data (e.g., NGS) [6] [8] | Processed data, integrated multi-omics sets [8] |

| Primary Output | Processed data, analysis reports, visualizations [8] | Novel algorithms, predictive models, scientific publications [10] [8] |

| Typical Tasks | Run NGS workflows, quality control, database management [9] [8] | Develop new algorithms, perform systems biology modeling, network analysis [10] [7] |

| Interaction with Lab Scientists | Collaborate to interpret results from specific datasets [8] | Work to design experiments and formulate new hypotheses [11] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Skills, Education, and Experimental Protocols

Success in these fields requires a unique blend of technical and scientific competencies. The required skill sets show significant overlap but are distinguished by their depth in specific areas.

Essential Skills and Technologies

Both roles require proficiency in programming and statistics, but their applications differ.

- Bioinformatics Analyst Skills: They require strong proficiency in Python and R for data wrangling and automation, along with expertise in specific bioinformatics tools and pipelines (e.g., GATK, DESeq2) [9]. As data scales, skills in workflow management (Nextflow, Snakemake), containerization (Docker), and cloud computing (AWS, Google Cloud) are essential for building reproducible and scalable analyses [9].

- Computational Biologist Skills: They need a deep understanding of machine learning and statistical modeling to build predictive models from biological data [12]. A strong foundation in algorithm design and the mathematical principles behind models is critical [7]. They also require a broader, more integrated knowledge of biological systems to contextualize their findings [11].

Table 2: Skills and Educational Requirements

| Attribute | Bioinformatics Analyst | Computational Biologist |

|---|---|---|

| Core Programming Languages | Python, R, Perl, SQL [9] [13] | Python, R, C++ [12] |

| Defining Technical Skills | NGS analysis, workflow automation, cloud computing, database management [9] | Machine Learning (45.8%), Algorithms, Statistics, Computer Science (41.5%) [12] |

| Key Biological Knowledge | Molecular biology, genetics, genomics [9] | Systems biology, cancer biology, genetics, immunology [12] |

| Typical Education | Master's Degree common [8] | Doctoral Degree common (77.6%) [12] |

| Years of Experience (Typical Job Posting) | 0-5 years [8] [12] | 3-8 years [12] |

Key Research Reagent Solutions

While both roles are computational, their work is grounded in biological data generated from wet-lab experiments. The table below details key materials and their functions relevant to the experiments they analyze.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials in Omics Studies

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Library Prep Kits | Prepare genomic DNA or cDNA for sequencing by fragmenting, adding adapters, and amplifying [9]. |

| PCR Reagents (Primers, Polymerases, dNTPs) | Amplify specific DNA regions or entire transcripts for analysis and sequencing [11]. |

| Antibodies for Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) | Isolate specific DNA-protein complexes to study epigenetics and gene regulation [11]. |

| Restriction Enzymes and Modification Enzymes | Cut or modify DNA molecules for various assays, including cloning and epigenetics studies [11]. |

| Cell Culture Reagents & Stimuli | Maintain and treat cell lines under study to model biological states and disease conditions [11]. |

Detailed Methodologies for a Typical Multi-Omics Workflow

The collaboration between these roles is best exemplified in a complex multi-omics study. The following protocol outlines the steps from experiment to insight, highlighting the distinct contributions of each role.

A. Experimental Design and Data Generation

- Hypothesis: A research team investigates mechanisms of drug resistance in cancer.

- Wet-Lab Protocol: Researchers establish resistant and control cell lines. They extract DNA (for whole-genome sequencing), RNA (for RNA-Seq), and perform ChIP-Seq for a key histone modification. All sequencing is performed on an NGS platform, generating raw FASTQ files [11].

B. Bioinformatics Analyst Workflow The Bioinformatics Analyst takes the raw data through a series of processing and normalization steps.

Bioinformatics Analysis Pipeline: This standardized workflow transforms raw data into structured, analysis-ready formats.

- Quality Control (QC): Run FASTQC on raw FASTQ files to assess sequence quality. Trimming and filtering are performed based on QC results [9].

- Alignment: Align reads to a reference genome (e.g., hg38) using an aligner like STAR (for RNA-Seq) or BWA (for DNA-Seq) [9].

- Data Transformation: For RNA-Seq, use a tool like featureCounts or HTSeq to generate a count matrix of genes per sample. For DNA-Seq, use GATK for variant calling to produce a VCF file [9].

- Initial Analysis: Perform differential expression analysis (e.g., with DESeq2 in R) to generate a list of genes significantly altered in resistant vs. control cells [9]. The Analyst delivers this processed data and initial results to the Computational Biologist.

C. Computational Biologist Workflow The Computational Biologist uses the processed data to build an integrated model of resistance.

Computational Biology Modeling Workflow: This exploratory process integrates diverse data to generate biological insights and new hypotheses.

- Data Integration: Integrate the RNA-Seq differential expression results, DNA-Seq variant calls, and ChIP-Seq peaks. The Computational Biologist might use R/Bioconductor or custom Python scripts to overlay these data types onto genomic coordinates and gene networks [8] [7].

- Network and Machine Learning Modeling: Construct a gene co-expression network or a protein-protein interaction network centered on the differentially expressed genes. Apply machine learning (e.g., graph neural networks) to identify key regulatory modules driving the resistance phenotype [8] [12].

- Hypothesis Generation and Simulation: The model may predict that a specific, non-coding variant disrupts a transcription factor binding site, down-regulating a key gene. The Computational Biologist could then use this insight to formulate a new, testable hypothesis (e.g., "Re-introducing this gene product will re-sensitize cells to the drug") and propose a follow-up wet-lab experiment [11] [7].

Career Trajectories and Professional Outlook

Within the context of computational biology research, these roles offer distinct but complementary career paths. Bioinformatics Analysts are in high demand in pharmaceutical companies, genomics startups, and clinical research organizations, with a career path that can progress to roles like Senior Analyst, Genomics Data Scientist, or Pipeline Developer [8]. Computational Biologists often advance into more research-intensive positions such as Principal Scientist, Research Lead, or specialist roles in AI-driven drug discovery, frequently within academia or R&D divisions of large biotech firms [8] [11].

Salaries reflect the typical educational requirements and specializations, with Bioinformatics Analysts earning an average of \$70,000-\$100,000 and Computational Biologists, who often hold PhDs, earning upwards of \$110,000-\$150,000 [8]. Data from 2024 shows the average U.S. salary for Computational Biologists was \$117,447, with core skills like Computational Biology and Protein Structures being particularly valuable [12].

In summary, the distinction between a Bioinformatics Analyst and a Computational Biologist is foundational in modern life science research. The Bioinformatics Analyst is an expert in data engineering and the application of tools, ensuring that vast quantities of biological data are processed accurately and efficiently into a structured form. The Computational Biologist is an expert in model-building and theoretical exploration, using that structured data to uncover deeper biological principles and generate novel hypotheses.

For research teams in academia and drug development, this synergy is not merely operational but strategic. The combination of robust, reproducible data analysis and insightful, predictive modeling creates a powerful engine for scientific discovery. As biological data continues to grow in scale and complexity, the collaborative partnership between these two disciplines will remain a cornerstone of progress in the life sciences.

In the evolving landscape of computational biology research, distinct professional roles have emerged to tackle the challenges of big data, clinical translation, and software infrastructure. This guide provides a technical deep-dive into three pivotal careers: Genomics Data Scientist, Clinical Bioinformatician, and Research Software Engineer (RSE). Framed within the broader context of careers in computational biology, this document delineates their unique responsibilities, technical toolkits, and experimental methodologies to assist researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in navigating this complex ecosystem. The integration of these roles is fundamental to advancing genomic medicine, enabling the transition from raw sequencing data to clinically actionable insights and robust, scalable software solutions.

Role Comparison & Core Responsibilities

The following table summarizes the primary focus, key responsibilities, and typical employers for each role, highlighting their distinct contributions to computational biology research.

Table 1: Core Role Overview

| Role | Primary Focus | Key Responsibilities | Typical Employers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics Data Scientist | Developing and applying advanced statistical and machine learning models to extract biological insights from large genomic datasets. | - Analysis of large-scale genomic data (e.g., WGS, RNA-seq)- Statistical modeling and machine learning- Developing predictive models for disease or treatment outcomes- Data mining and integration of multi-omics data | Pharmaceutical companies, biotech startups, large academic research centers, contract research organizations (CROs) |

| Clinical Bioinformatician | Translating genomic data into clinically actionable information to support patient diagnosis and treatment. | - Developing, validating, and maintaining clinical bioinformatics pipelines for genomic data- Interpreting genomic variants in a clinical context- Ensuring data quality, process integrity, and compliance with clinical regulations (e.g., ISO, CAP/CLIA)- Collaborating with clinical scientists and oncologists to return results to patients [14] [15] | NHS Genomic Laboratory Hubs, hospital diagnostics laboratories, public health agencies (e.g., Public Health England), diagnostic companies [14] [15] |

| Research Software Engineer (RSE) | Designing, building, and maintaining the robust software infrastructure and tools that enable scientific research. | - Bridging the gap between research and software development, translating scientific problems into technical requirements [16] [17]- Applying software engineering best practices (version control, testing, CI/CD, documentation) [16]- Optimizing computational workflows for performance and scalability- Ensuring software sustainability, reproducibility, and FAIR principles [16] [17] | Universities, research institutes, government agencies, pharmaceutical R&D departments [16] [17] |

Technical Toolkit & Skill Sets

Each role requires a specialized blend of programming skills, software tools, and domain-specific knowledge. The table below details the essential technical competencies.

Table 2: Technical Toolkit & Skill Sets

| Role | Programming & Scripting | Key Software & Tools | Domain Knowledge |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics Data Scientist | Python, R, SQL, possibly Scala/Java | Machine learning libraries (TensorFlow, PyTorch), statistical packages, Jupyter/RStudio, cloud computing platforms (AWS, GCP, Azure), workflow managers (Nextflow, Snakemake) | Human genetics, statistical genetics, molecular biology, drug discovery pathways |

| Clinical Bioinformatician | Python, R, SQL, shell scripting | Bioinformatics pipelines (Nextflow, Snakemake), genomic databases (Ensembl, ClinVar, COSMIC), HPC/cloud environments, variant annotation & visualization tools [14] | Human genetics and genomics, variant interpretation guidelines, clinical regulations (GDPR, GCP, ISO) [18], disease mechanisms [15] |

| Research Software Engineer (RSE) | Python, C++, Java, R, Julia, SQL | Version control (Git), continuous integration (CI/CD) tools, containerization (Docker, Singularity), workflow managers (Nextflow, Snakemake), parallel computing (MPI, OpenMP) [16] | Software engineering best practices, data structures and algorithms, high-performance computing (HPC), FAIR data principles, specific research domain (e.g., biology, physics) [16] [17] |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol: Development and Validation of a Clinical Bioinformatics Pipeline

This methodology outlines the process a Clinical Bioinformatician follows to create a robust pipeline for analyzing patient whole genome sequencing (WGS) data, as used in the NHS [14].

1. Define Requirements & Identify Test Data:

- Collaborate with clinical scientists and oncologists to define the biological and clinical requirements for the analysis (e.g., specific variant types, biomarkers).

- Outline the test strategy, including identification of edge cases and scenarios for testing [14].

- Source appropriate, validated test data, including samples with known truth sets, to benchmark the pipeline's performance.

2. Pipeline Construction & Component Integration:

- Tool Selection: Choose established, well-documented bioinformatics tools for alignment (e.g., BWA), variant calling (e.g., GATK), and annotation (e.g., Ensembl VEP).

- Workflow Orchestration: Implement the pipeline using a workflow manager like Nextflow or Snakemake to ensure reproducibility and scalability [16].

- Database Queries: Write and optimize database queries (e.g., SQL) to retrieve necessary genomic annotations and metadata [14].

3. Rigorous Validation & Risk Assessment:

- Execute the pipeline on the test data and compare outputs against the known truth set.

- Calculate key performance metrics: sensitivity, specificity, and precision for variant detection.

- Conduct a formal risk assessment to identify potential failure modes and their impact on clinical decision-making. Document all procedures and results for audit trails [14].

4. Implementation & User Support:

- Deploy the validated pipeline into the clinical production environment (e.g., a decision support system like the cancer DSS) [14].

- Update user documentation and provide training to clinical scientist end-users.

- Establish a process for ongoing monitoring, maintenance, and updates in response to new biological knowledge or software changes.

Protocol: Architecting a Scalable Research Software Solution

This methodology describes the systematic approach a Research Software Engineer takes to develop sustainable software for a scientific project.

1. Requirement Analysis & Translation:

- Collaborate closely with researchers to understand the scientific problem and translate it into detailed technical and user requirements [16] [17].

- Define functional needs (what the software should do) and non-functional needs (performance, scalability, usability).

2. Software Design & Planning:

- Create a software architecture diagram outlining key components, data flow, and interactions.

- Select appropriate technologies, frameworks, and data structures.

- Establish a project structure adhering to best practices for organization, version control (Git), and documentation from the outset [16].

3. Implementation with Quality Assurance:

- Develop code following engineering best practices: modular design, comprehensive testing (unit, integration), and clear documentation [16].

- Use continuous integration (CI) to automate testing and deployment processes.

- Integrate existing tools and libraries where possible to avoid "reinventing the wheel" [16].

4. Performance Optimization & Sustainability:

- Profile the code to identify performance bottlenecks.

- Apply optimizations such as parallelization (e.g., using MPI/OpenMP for HPC) or algorithm improvement [16].

- Package the software using containerization (e.g., Docker) to ensure portability and reproducibility.

- Plan for long-term maintenance, including licensing and defining a contribution model [16] [19].

Workflow Visualization & Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the collaborative interaction between the three roles in a typical genomics research project, from data generation to clinical application.

Diagram 1: Collaborative Workflow Between Key Roles

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

This section details critical "research reagents" – the key software tools, databases, and platforms that are essential for experimentation and analysis in these computational fields.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

| Item Name | Function & Application | Relevance to Roles |

|---|---|---|

| Nextflow/Snakemake | Workflow management systems that enable the creation of reproducible, scalable, and portable bioinformatics/data analysis pipelines. | Core for CB & RSE; used to build clinical and research pipelines. Used by GDS for large-scale analyses [16]. |

| Docker/Singularity | Containerization platforms that package software and all its dependencies into a standardized unit, ensuring consistency across different computing environments. | Core for RSE for deploying robust software. Critical for CB to ensure consistent clinical pipeline runs. Used by GDS for model deployment. |

| Git (e.g., GitHub, GitLab) | A version control system for tracking changes in source code during software development, enabling collaboration, and managing project history. | Core for all three roles for code management, collaboration, and implementing CI/CD [16]. |

| Ensembl/VEP | A comprehensive genome database and the Variant Effect Predictor (VEP) tool, which annotates genetic variants with their functional consequences (e.g., impact on genes, proteins). | Core for CB & GDS for the biological interpretation of genomic variants. Used by RSEs when building annotation services. |

| ClinVar | A public, freely accessible archive of reports detailing the relationships between human genetic variants and phenotypes, with supporting evidence. | Core for CB for clinical variant interpretation. Used by GDS for curating training data for models. |

| Jupyter/RStudio | Interactive development environments for data science, supporting code execution, visualization, and narrative text in notebooks or scripts. | Core for GDS for exploratory data analysis, prototyping models, and sharing results. Used by CB & RSE for prototyping and analysis. |

| HPC/Cloud Cluster | High-performance computing (HPC) systems or cloud computing platforms (AWS, GCP, Azure) that provide the massive computational power required for genomic analyses and complex simulations. | Core for all three roles for executing computationally intensive tasks. RSEs often manage access and optimization for these resources [16] [17]. |

The fields of computational biology and genomics thrive on the specialized, synergistic contributions of the Genomics Data Scientist, Clinical Bioinformatician, and Research Software Engineer. The Genomics Data Scientist extracts meaningful patterns from complex data, the Clinical Bioinformatician ensures these insights are reliably translated into clinical practice, and the Research Software Engineer builds the foundational tools that make everything possible. For professionals in drug development and scientific research, understanding the distinct responsibilities, toolkits, and methodologies of these roles is critical for building effective, multidisciplinary teams capable of advancing genomic medicine and delivering new therapeutics to patients.

The mainstream application of high-throughput assays in biomedical research has fundamentally transformed the biological sciences, creating sustained demand for scientists educated in Computational Biology and Bioinformatics (CBB) [20]. This interdisciplinary field, situated at the nexus of biology, computer science, and statistics, requires a unique blend of technical proficiency and biological wisdom [21]. Professionals with advanced degrees (PhDs) and medical training (MDs) are particularly well-positioned to navigate this complex landscape, facilitating the responsible translation of computational research into clinical tools [20]. The career paths for these individuals have diversified significantly, extending beyond traditional academic roles into various industry positions and hybrid careers that integrate multiple domains.

This evolution reflects broader trends in the scientific workforce. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics indicates robust job growth in life and physical sciences, with biomedical engineers and statisticians among the fastest-growing occupations [21]. Concurrently, career aspirations of graduate students have shifted, with several studies indicating a trend away from research-intensive academic faculty careers [21]. This has given rise to the concept of a branching network of career development pathways, where computational biologists can leverage their specialized training across diverse sectors including academia, industry, government, and entrepreneurship [21].

Defining the Disciplines: Computational Biology and Bioinformatics

While often used interchangeably, computational biology and bioinformatics represent distinct yet complementary disciplines within the broader field of computational biomedical research. Understanding their differences in focus, methodology, and application is essential for navigating career opportunities.

Table 1: Key Differences Between Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

| Aspect | Bioinformatics | Computational Biology |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Application of computational tools to manage, analyze, and interpret biological data [22] | Development and use of mathematical and computational models to understand biological systems [22] |

| Primary Focus | Data-driven, emphasizing management, storage, and analysis of biological data [22] | Hypothesis-driven, focusing on understanding biological systems and phenomena [22] |

| Core Areas | Genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics, database management [22] | Systems biology, evolutionary biology, quantitative modeling, molecular dynamics [22] |

| Key Tools & Techniques | Sequence alignment (BLAST, FASTA), data mining, network analysis [22] | Mathematical modeling, simulation algorithms, agent-based modeling [22] |

| Typical Outputs | Sequence alignments, functional annotations, structural predictions [22] | Mechanistic insights, dynamic models, predictions of system behavior [22] |

| Interdisciplinary Basis | Biology, information technology, data science [22] | Biology, mathematics, physics, computational science [22] |

In practice, these fields increasingly converge in modern research environments. Software-as-a-service (SaaS) platforms frequently combine tools from both data analysis and modeling, enabling researchers to transition seamlessly between analyzing large datasets and building biological models [22]. This integration accelerates discovery across biological domains by providing comprehensive solutions for investigating complex systems.

Academic Career Pathways

Academic careers offer a traditional, structured path for computational biologists drawn to research-driven, grant-funded work with significant emphasis on mentorship and publication.

Traditional Academic Trajectory

The academic pathway typically follows a defined sequence: postdoctoral training, junior faculty appointment, and progression through senior faculty ranks.

Postdoctoral Fellowship: Following doctoral training, most academic-bound scientists complete one or more postdoctoral positions, typically lasting 2-4 years each. These positions provide specialized research training, opportunities to establish publication records, and time to develop independent research ideas. Current openings highlight foci in cancer bioinformatics, multi-omics, and AI-driven modeling [23].

Faculty Appointments: The transition to independence typically begins with a tenure-track Assistant Professor position. Success in these roles depends heavily on securing extramural funding, establishing a productive research program, and contributing to teaching and service. Tenure-track faculty develop research programs, mentor graduate students, and teach. Example positions include Tenure-Track Assistant Professor in Gene Regulation or Molecular Biology [23]. Advancement to Associate Professor (typically with tenure) and eventually Full Professor signifies peer recognition for scholarly impact and sustained funding success. Leadership roles such as Lab PI involve overall direction of research, personnel, and finances [24].

Academic Research and Funding Landscape

Academic computational biologists compete for research funding from federal agencies (NIH, NSF, DOE), private foundations, and increasingly, industry partnerships. Research in academic settings often explores fundamental biological questions, though translational applications are increasingly common. The partnership between the University of Tennessee and Oak Ridge National Laboratory exemplifies how academic institutions collaborate with government laboratories to provide unique training environments and research opportunities [21].

Industry Career Pathways

Industry careers offer diverse opportunities for computational biologists in sectors including biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and technology, typically featuring higher compensation and applied research focus compared to academia.

Industry Roles and Organizational Structures

Industry roles for computational biologists vary considerably based on company stage, therapeutic focus, and technical orientation.

Table 2: Industry Career Pathways and Positions

| Career Track | Entry-Level Position | Mid-Career Position | Senior/Leadership Position |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Contributor (Technical Track) | Junior Bioinformatician [24] | Senior/Staff Bioinformatician [24] | Principal Bioinformatician [24] |

| Management Track | Junior Bioinformatician/Team Lead [24] | Manager/Head of Bioinformatics [24] | Director/CTO [24] |

| Research & Development | Bioinformatics Analyst [25] | Research Scientist | Senior Scientist/VP of Research |

Industry computational biologists typically work in one of two organizational models: digital-first companies where computational technology is the primary asset, and biology-first companies where computational platforms support wet-lab product development [26]. Another key distinction lies between tool builders who develop new algorithms and methods, and tool users who implement and parameterize existing tools to solve biological problems – with the latter being more common in industry settings [26].

Company stage significantly influences work environment. Early-stage startups prioritize speed and may tolerate technical debt, while established companies implement robust software engineering practices with extensive infrastructure [26]. Compensation in industry generally exceeds academic scales, with bioinformatics scientists in major hubs like Boston commanding base salaries beginning at approximately $115,000 [26].

Key Industry Sectors

- Biotechnology/Pharmaceuticals: Companies like AstraZeneca employ computational biologists for target discovery, biomarker development, and clinical trial optimization [23]. Roles focus on therapeutic development across oncology, immunology, and rare diseases.

- Bioinformatics Software & Services: Companies developing analytical platforms, SaaS solutions, or consultancy services offer roles in software engineering, application development, and technical support [26].

- Medical Technology & Diagnostics: Firms integrating computational approaches into diagnostic devices, medical instruments, or digital health solutions require expertise in clinical informatics and regulatory affairs.

Hybrid and Emerging Career Paths

Beyond traditional academia and industry roles, computational biologists increasingly pursue hybrid careers that integrate multiple domains or emerge at interdisciplinary frontiers.

- Entrepreneurship: Founding startups to commercialize research innovations or computational platforms represents a high-risk, high-reward pathway. Resources like Nucleate and venture capital groups support this transition [26].

- Science Policy & Regulatory Affairs: Positions at government agencies (FDA, NIH), non-profit organizations, or within corporate governance bridge scientific expertise with public policy and regulatory science.

- Scientific Publishing & Communications: Roles as editors, scientific writers, or communications specialists at journals, publishers, or research institutions leverage analytical and communication skills.

- Consulting: Management, technical, or strategic consulting firms serving life sciences clients value computational biologists for analytical rigor and domain knowledge.

MD/PhD trained computational biologists occupy a particularly strategic niche, facilitating collaboration between CBB researchers and clinical counterparts [20]. Their dual training enables them to lead translational initiatives, oversee responsible implementation of computational tools in clinical settings, and drive clinically-informed research agendas.

Essential Skills and Competencies

Success in computational biology requires a blend of technical skills, biological knowledge, and professional abilities that evolve throughout one's career.

The Computational Biology Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Skills for Computational Biologists

| Skill Category | Specific Competencies | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Skills | Programming (Python, R, Perl) [11] [25], Statistical computing, Database management (SQL) [25], Unix command line | Data analysis pipeline development, algorithm implementation, reproducible research |

| Biological Knowledge | Molecular biology, Genetics [25], Biochemistry [25], Domain specialization (e.g., immunology, neuroscience) | Experimental design interpretation, biological context application, mechanistic insight generation |

| Statistical & Analytical Methods | Probability theory, Hypothesis testing, Multiple testing correction, Machine learning foundations [11], Data normalization | Rigorous experimental analysis, appropriate method selection, valid biological conclusion drawing |

| Professional Skills | Scientific communication [25], Collaboration [25], Problem-solving [25], Time management [25] | Cross-functional teamwork, result presentation, project management, mentorship |

The core toolkit for computational biologists includes expertise in a scripting language (Python, Perl), facility with a statistical environment (R, MATLAB), database management skills, and strong foundations in biostatistics [20]. Beyond these technical competencies, biological knowledge remains essential – computational biologists must understand experimental design principles and biological context to generate meaningful insights [11]. The ability to communicate effectively with bench scientists and clinicians represents a critical, often overlooked skill [20].

Methodology: Tracking Career Outcomes

Systematic tracking of graduate career trajectories provides valuable data for program evaluation and student mentoring. The University of Tennessee's School of Genome Science and Technology (GST) exemplifies this approach through longitudinal monitoring of PhD alumni.

Data Collection Protocol

- Data Sources: Compile information from LinkedIn profiles, institutional websites, alumni publications, and personal communications [21]. Multiple sources are typically required as each alone is incomplete.

- Classification Framework: Categorize positions as research (postdoc, research staff, product development), research-related science (teaching, intellectual property, publishing), science-related (consulting), or non-science [21].

- Timeline Considerations: Track first positions after PhD (typically postdoctoral research) and subsequent positions. Brief employment in advisor's group (<6 months) may be excluded from analysis [21].

- Demographic Data: Collect gender, international status, and race/ethnicity information to evaluate program accessibility and diversity [21].

Outcome Analysis

Analysis of the GST program revealed that among 77 PhD graduates between 2003-2016, most entered with traditional biological science backgrounds, yet two-thirds transitioned into computational or hybrid (computational-experimental) positions [21]. This demonstrates the program's effectiveness in graduating computationally-enabled biologists for diverse careers.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the career tracking methodology:

Navigating Career Transitions

Strategic planning facilitates successful transitions between career sectors and progression within chosen paths.

Transitioning from Academia to Industry

- Skill Alignment: Industry computational biologists emphasize that "our product is biological insights we extract from data" rather than elegant code [11]. Focus on practical problem-solving abilities rather than theoretical computer science knowledge.

- Mindset Adjustment: Academic success often correlates with group size, while industry technical teams may be led by younger colleagues who prefer management, with senior individual contributors valued for technical expertise [26].

- Networking Strategy: Leverage professional connections, attend industry-focused conferences, and conduct informational interviews to understand sector-specific requirements and opportunities.

Path Switching and Career Progression

Early-stage professionals (PhD, postdoc, junior roles) can pivot relatively easily between academia, individual contributor, and management tracks [24]. As careers advance, skillsets become more specialized – transitioning between principal bioinformatician and head of bioinformatics roles requires significant additional training in technical leadership or people management, respectively [24].

The career landscape for computational biologists with advanced training continues to diversify, offering pathways in academia, industry, and hybrid roles. Success in this evolving ecosystem requires both technical excellence and strategic career management – including deliberate skill development, professional networking, and adaptability to changing opportunities. As the field matures, computational biologists are positioned to make increasingly significant contributions to biological knowledge, therapeutic development, and clinical medicine across multiple sectors.

Computational biology has undergone a remarkable transformation, evolving from a supportive function to an independent scientific domain that is now an integral part of modern biomedical research [27]. This evolution is primarily driven by the explosive growth of large-scale biological data and decreasing sequencing costs, creating a landscape where biological expertise and computational prowess have become mutually dependent. The field represents an intersection of computer science, biology, and data science, with additional foundations in applied mathematics, molecular biology, chemistry, and genetics [28]. As the discipline advances, researchers who can seamlessly integrate deep biological understanding with sophisticated computational techniques are increasingly leading innovation in areas ranging from drug discovery to clinical diagnostics and therapeutic development [27] [6].

The cultural shift towards data-centric research has not diminished the need for biological knowledge; rather, it has elevated its importance. Computational researchers—encompassing computer scientists, data scientists, bioinformaticians, and statisticians—now require interdisciplinary skills to navigate complex biological questions [27]. This whitepaper examines why biological domain knowledge remains as crucial as technical computational skills, exploring the theoretical frameworks, practical applications, and career implications of this symbiotic relationship within pharmaceutical and biotechnology research environments.

The Evolving Role of the Computational Biologist: From Support Service to Scientific Leader

The perception of computational research has shifted significantly over the past decade. Traditionally, computational researchers played supportive roles within research programs led by other scientists who determined the feasibility and significance of scientific inquiries [27]. Today, these researchers are emerging as leading innovators in scientific advancement, with the availability of vast and diverse public datasets enabling them to analyze complex datasets that demand truly interdisciplinary skills [27].

This transition is reflected in the distinction between computational biology and bioinformatics. While these disciplines are often used interchangeably, they represent different approaches:

Table: Computational Biology vs. Bioinformatics

| Aspect | Computational Biology | Bioinformatics |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | Uses computer science, statistics, and mathematics to solve biological problems [6] | Combines biological knowledge with computer programming and big data, particularly for large datasets like genome sequencing [6] |

| Data Scope | Concerns parts of biology not necessarily wrapped up in big data; works with smaller, specific datasets [6] | Particularly useful for large amounts of data, such as genome sequencing; requires programming and technical knowledge [6] |

| Typical Applications | Population genetics, protein analysis, understanding specific pathways within larger genomes [6] | Leveraging machine learning, AI, and other technologies to handle previously overwhelming amounts of data [6] |

| Biological Perspective | More concerned with the big picture of what's going on biologically [6] | Focused on efficiently leveraging different technologies to accurately answer biological questions [6] |

The computational biologist's role has expanded to include early involvement in experimental design, which is essential for effectively addressing complex scientific questions [27]. This integration facilitates the selection of optimal analysis strategies for intricate biological datasets and represents a fundamental shift from service provider to scientific leader.

The Criticality of Biological Domain Knowledge: From Data Interpretation to Therapeutic Innovation

Understanding Biological Context and Experimental Design

Biological expertise enables computational researchers to distinguish between computational artifacts and biologically meaningful signals. This distinction is particularly crucial when dealing with the complexities of large-scale biological data, which may contain errors, inconsistencies, or biases that can significantly impact analytical results [27]. Researchers with biological domain knowledge can design computational approaches that account for technical variations, batch effects, and platform-specific artifacts that might otherwise compromise data interpretation.

The importance of biological understanding extends to experimental design, where computational researchers must comprehend the technological platforms generating the data—including their limitations, sensitivities, and specificities—to develop appropriate analytical frameworks. This includes recognizing that "raw data" refers to the original, unprocessed, and unaltered form of data collected directly from its source, such as raw measurements from experiments or images from microscope-associated software [29]. The process of converting this raw data into processed data through cleaning, organization, calculations, and transformations requires biological insight to ensure that meaningful information is not lost or distorted during these procedures [29].

Biological Knowledge in Data Modeling and Hypothesis Generation

Computational biology employs various modeling approaches, including the use of Petri nets and tools like esyN for computational biomodeling [28]. These techniques allow researchers to build computer models and visual simulations of biological systems to predict how such systems will react to different environments [28]. However, creating biologically relevant models requires deep understanding of the underlying systems being modeled.

Similarly, systems biology depends on computing interactions between various biological systems from the cellular level to entire populations to discover emergent properties [28]. This process usually involves networking cell signaling and metabolic pathways using computational techniques from biological modeling and graph theory [28]. Without substantive biological knowledge, these models may be mathematically elegant but biologically meaningless.

Table: Applications of Computational Biology Across Biological Domains

| Biological Domain | Computational Applications | Impact on Drug Development |

|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Sequence alignment, homology studies, intergenic region analysis [28] | Enables personalized medicine through analysis of individual patient genomes [28] |

| Pharmacology | Analysis of genomic data to find links between genotypes and diseases, drug screening [28] | Facilitates development of more accurate drugs and addresses patent expirations [28] |

| Oncology | Analysis of tumor samples, characterization of tumors, understanding cellular properties [28] | Aids in early cancer diagnosis and understanding factors contributing to cancer development [28] |

| Neuroscience | Modeling brain function through realistic or simplified brain models [28] | Contributes to understanding neurological systems and mental disorders [6] [29] [30] |

| Toxicology | Predicting safety and potential toxicity of compounds in early drug discovery [28] | Reduces late-stage failures in drug development by early identification of toxicity issues |

Practical Integration: Methodologies for Combining Biological and Computational Expertise

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The integration of biological and computational expertise begins at the earliest stages of research design. The following workflow illustrates a standardized approach for designing studies that effectively combine experimental and computational methods:

Diagram 1: Integrated Research Workflow illustrates the synergistic relationship between biological and computational domains throughout the research process.

Biomarker Discovery Case Study

Computational biology plays a pivotal role in identifying biomarkers for diseases such as cardiovascular conditions [28]. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for biomarker discovery that integrates biological and computational expertise:

Protocol: Integrated Computational-Experimental Biomarker Discovery

Objective: Identify and validate novel biomarkers for coronary artery disease using integrated multi-omics approaches.

Experimental Components:

- Sample Collection: Obtain human plasma samples from three cohorts: confirmed coronary artery disease patients, myocardial infarction patients, and healthy controls (n≥100 per group).

- Multi-Omics Data Generation:

- Genomics: Whole exome sequencing using Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform

- Proteomics: Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) with tandem mass tag (TMT) labeling

- Metabolomics: Targeted LC-MS for known metabolites and untargeted approach for novel metabolite discovery

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize data using quantile normalization, log2 transformation for proteomics data, and probabilistic quotient normalization for metabolomics data.

Computational Components:

- Feature Selection: Employ least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression to identify most discriminative features across omics layers.

- Integration Methods: Apply multiple integration approaches including:

- Similarity Network Fusion (SNF) to combine multi-omics data

- Multi-Omics Factor Analysis (MOFA) for dimensionality reduction

- Regularized Generalized Canonical Correlation Analysis (RGCCA)

- Machine Learning Classification: Implement random forest, support vector machines, and XGBoost with nested cross-validation to build predictive models and assess biomarker performance.

Validation Framework:

- Technical Validation: Assess analytical precision using coefficient of variation (<15%) and perform spike-in experiments for recovery assessment.

- Biological Validation: Use pathway enrichment analysis (KEGG, Reactome) to establish biological plausibility of identified biomarkers.

- Clinical Validation: Evaluate biomarkers against established clinical endpoints using Cox proportional hazards models and assess reclassification improvement using net reclassification index (NRI).

This methodology exemplifies how biological knowledge (understanding disease pathophysiology, sample requirements, analytical validation) must be integrated with computational expertise (advanced algorithms, machine learning, statistical analysis) to generate clinically meaningful results.

Research Reagent Solutions for Integrated Studies

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Integrated Studies

| Category | Specific Items/Platforms | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Human plasma/serum samples, LC-MS grade solvents, TMT labeling kits, Illumina sequencing reagents | Generation of high-quality multi-omics data from biological samples [28] |

| Commercial Assays | Targeted metabolomics panels, proteomic sample preparation kits, DNA extraction kits | Standardization of sample processing to reduce technical variability [29] |

| Computational Tools | LASSO implementation (glmnet), SNF package, MOFA+, XGBoost, RGCCA | Statistical analysis and integration of multi-omics data for biomarker discovery [28] |

| Data Resources | KEGG pathway database, Reactome knowledgebase, clinical cohort data | Contextualization of findings within established biological knowledge [28] |

| Bioinformatics Platforms | Galaxy, GenePattern, Bioconductor | Accessible analysis frameworks for researchers with varying computational expertise [27] |

Developing Dual Competencies: Educational and Skill-Building Frameworks

Core Competency Matrix

For researchers pursuing careers in computational biology, developing both biological and computational competencies is essential. The following matrix outlines key skill domains:

Table: Essential Skill Domains for Computational Biology Researchers

| Biological Domain Skills | Computational Domain Skills | Integrated Application Skills |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular biology techniques and principles [31] | Programming (Python, R, SQL) and software development [6] | Experimental design that incorporates computational requirements [27] |

| Pathway analysis and systems biology [28] | Statistics, machine learning, and algorithm development [6] [28] | Multi-omics data integration and interpretation [28] |

| Disease mechanisms and pathophysiology [28] | Data visualization and communication [6] | Biological network construction and analysis [28] |

| Laboratory techniques and limitations [31] [29] | Cloud computing and high-performance computing [27] | Clinical translation of computational findings [28] |

| Ethical considerations in biological research [27] | Data management and reproducibility practices [29] | Development of clinically actionable biomarkers [28] |

Strategies for Skill Development

Researchers can develop these dual competencies through several approaches:

Formal Cross-Training: Pursuing degrees or certificates that combine biological and computational sciences, such as bioinformatics programs that emphasize both programming skills and biological knowledge [6].

Experimental Lab Immersion: Computational researchers should establish links with experimental groups and spend time in their labs—not just observing but participating in experiments [31]. This immersion provides crucial understanding of what can go wrong during experiments and the particular pitfalls and challenges of laboratory work [31].

Interdisciplinary Collaboration: Actively pursuing bidirectional collaborations between domain experts and experimental biologists facilitates knowledge exchange and skill development [27]. These collaborations should begin early in experimental design to effectively address complex scientific questions [27].

Continuing Education: Keeping current with both experimental techniques through conferences and academic societies, and computational methods through workshops and technical training [31].

Career Implications and Professional Advancement

Diverse Career Pathways

The integration of biological and computational expertise opens diverse career pathways with limited repetition and extensive variety:

Bioinformatics Scientist: Develop algorithms, tools, and systems to interpret biological data like DNA sequences, protein samples, or cell populations [32]. Work ranges from crafting software for gene sequencing to building models that decipher complex biological processes [32].

Scientific Consulting: Apply computational biology expertise to solve diverse challenges across pharmaceutical companies, biotech startups, or research institutions, providing insights on drug development, personalized medicine, or data analysis [32].

Pharmacogenomics Researcher: Investigate how genes influence individual responses to drugs using computational tools to analyze genetic data and forecast drug responses, contributing to personalized medicine [32].

Biotechnology Product Management: Combine technical understanding of computational biology with business acumen to guide development of bioinformatics software or platforms [32].

Computational Biomedicine Researcher: Focus on applications in specific therapeutic areas like oncology, where computational biology aids in complex analysis of tumor samples to characterize tumors and understand cellular properties [28].

Leadership Opportunities in the Pharmaceutical Industry

The pharmaceutical industry requires a shift in methods to analyze drug data, moving beyond traditional spreadsheet-based approaches to sophisticated computational analyses [28]. This transition creates leadership opportunities for computational biologists with strong biological foundations. As the industry faces potential patent expirations on major medications, computational biology becomes increasingly necessary to develop replacement therapies [28]. Professionals who can bridge the gap between biological discovery and computational analysis are positioned for roles as:

- Drug Discovery Team Leaders: Direct interdisciplinary teams applying computational approaches to identify novel therapeutic targets

- Clinical Development Strategists: Inform clinical trial design through computational analysis of patient stratification biomarkers

- Translational Science Directors: Facilitate the movement between basic research discoveries and clinical applications

Emerging Trends and Technologies

The future of computational biology will be shaped by several converging trends:

Artificial Intelligence and Deep Learning: Advanced neural networks are increasingly being applied to biological problems such as protein structure prediction (as demonstrated by AlphaFold), drug discovery, and clinical diagnostics.

Single-Cell Multi-Omics: Technologies enabling simultaneous measurement of genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and epigenomic features at single-cell resolution are creating unprecedented data complexity that demands sophisticated computational approaches grounded in cellular biology.

Digital Pathology and Medical Imaging: Computational analysis of histopathology images and medical scans using computer vision techniques requires integration of medical knowledge with deep learning expertise.

Real-World Evidence and Digital Health Technologies: The growth of wearable sensors and electronic health records creates opportunities for computational biologists to derive insights from real-world data streams, requiring understanding of clinical medicine and physiology.

In conclusion, biological expertise remains as critical as computational prowess in computational biology. The most successful researchers and drug development professionals will be those who achieve depth in both domains, creating a synergistic understanding that transcends what either perspective could accomplish independently. As computational biology continues to evolve, the integration of biological knowledge with computational methods will drive innovations in personalized medicine, drug discovery, and therapeutic development [27] [28].

The field's future depends on cultivating researchers who can not only develop sophisticated algorithms but also understand the biological meaning and clinical implications of their results. This balanced approach ensures that computational biology continues to make meaningful contributions to understanding biological systems and improving human health. For organizations investing in computational biology capabilities, prioritizing the development of dual competencies will yield the greatest returns in research productivity and therapeutic innovation.

Building Your Toolkit: In-Demand Skills and Real-World Applications in 2025

The future of life sciences is unequivocally computational. In the era of big data, mastering core programming languages has become a fundamental requirement for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals aiming to extract biological insight from complex datasets. The fields of lipidomics, metabolomics, genomics, and transcriptomics now routinely generate petabytes of data annually, necessitating robust computational skills for meaningful analysis [33] [34]. Within this landscape, Python and R have emerged as the dominant programming languages, forming the essential toolkit for modern computational biology research.

The choice between Python and R is not merely a technical decision but a strategic one that influences research workflows, collaborative potential, and career trajectories. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of both languages within the context of computational biology research, offering a structured framework for researchers to develop proficiency in both ecosystems. We present quantitative comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and specialized toolkits to facilitate effective implementation across diverse biological research scenarios, from exploratory data analysis to large-scale machine learning applications.

Language Comparison: Python versus R in Biological Context

Technical Specifications and Ecosystem Analysis

Table 1: Core Language Characteristics in Computational Biology

| Feature | Python | R |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Strength | General-purpose programming, machine learning, AI integration [34] | Statistical analysis, data visualization, specialized analytical work [35] |

| Learning Curve | Gentler, intuitive syntax similar to English [35] | Steeper, especially for non-programmers; non-standardized code [35] |

| Visualization Capabilities | Matplotlib, Seaborn, Plotly (requires more code for complex graphics) [35] | ggplot2 (creates sophisticated plots with less code) [36] [35] |

| Performance Characteristics | High-level language suitable for building critical applications quickly [35] | Can exhibit lower performance but with optimized packages available [35] |

| Statistical Capabilities | Solid statistical tools but less specialized than R [35] | Extensive statistical packages; many statistical functions built-in [35] |

| Deployment & Production | Excellent for production systems, APIs, and scalable applications [36] [35] | Shiny for rapid app deployment; generally less suited for production systems [35] |

Table 2: Specialized Biological Analysis Packages

| Analysis Type | Python Packages | R Packages |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk Transcriptomics | InMoose (limma, edgeR, DESeq2 equivalents) [34] | limma, edgeR, DESeq2 [34] |

| Single-Cell Analysis | Scanpy, scverse ecosystem [34] | Bioconductor single-cell packages |

| Genomics | Biopython, PyRanges [36] | GenomicRanges (Bioconductor) [36] |

| Lipidomics/Metabolomics | Custom pipelines with pandas, NumPy [33] | Specialized packages for statistical processing [33] |

| Machine Learning | TensorFlow, scikit-learn, PyTorch [37] | caret, randomForest [35] |

| Data Manipulation | pandas, NumPy [38] [37] | tidyverse (dplyr, tidyr) [36] [35] |

Comparative Workflow for Differential Expression Analysis

Differential Expression Analysis Workflow: This diagram illustrates the parallel workflows for conducting differential expression analysis in R versus Python, highlighting ecosystem-specific packages while achieving similar analytical endpoints.

Integrated Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-cohort Transcriptomic Meta-Analysis

Objective: Identify consistently differentially expressed genes across multiple transcriptomic datasets using batch effect correction and meta-analysis techniques.

Materials and Reagents:

- Datasets: RNA-Seq count matrices from multiple studies or batches

- Computational Environment: Python 3.8+ with InMoose package or R 4.0+ with DESeq2/limma

- Hardware: Standard laptop (2022 MacBook Pro or equivalent sufficient for demonstration) [34]

Methodology:

Data Simulation & Cohort Generation (if working with synthetic data)

- Utilize splatter (R) or InMoose (Python) to simulate RNA-Seq data with known batch and group effects [34]

- Define parameters including number of genes, batches, and biological groups

- Generate count matrices and corresponding clinical metadata

Batch Effect Correction

- Apply ComBat-seq (R) or pycombat (InMoose) to adjust for technical variation [34]

- Validate correction efficiency through PCA visualization pre- and post-correction

Differential Expression Analysis

- Implement two complementary approaches:

- Individual Sample Data (ISD): Aggregate batches into single cohort after batch correction, then perform differential expression analysis

- Aggregate Data (AD): Perform differential expression analysis on each batch separately, then aggregate results using random-effects model [34]

- Implement two complementary approaches:

Result Integration & Visualization

- Compare log-fold-changes between approaches via correlation analysis

- Generate consensus list of significantly differentially expressed genes

- Create publication-quality visualizations (PCA plots, volcano plots, heatmaps)

Expected Outcomes: The protocol should yield a robust set of differentially expressed genes validated across multiple cohorts, with batch effects adequately controlled. Execution time for a standard analysis (6 samples, 3 batches) is approximately 3 minutes on standard hardware [34].

Protocol 2: Lipidomics Data Processing and Visualization

Objective: Process raw mass spectrometry-based lipidomics data to identify and visualize statistically significant lipid alterations between experimental conditions.

Materials and Reagents:

- Input Data: Lipid concentration tables with potential missing values, batch effects, and heteroscedastic variance [33]

- Quality Controls: Pooled quality control (QC) samples or NIST standard reference materials [33]

- Computational Environment: R with specialized lipidomics packages or Python with pandas/NumPy/Matplotlib

Methodology:

Missing Value Imputation

Data Normalization

Statistical Analysis & Hypothesis Testing

- Perform descriptive statistics with appropriate transformations for skewed distributions

- Conduct hypothesis testing accounting for multiple comparisons (FDR correction)

- Execute multivariate analyses (PCA, PLS-DA) to identify patterns

Specialized Lipid Visualizations

- Generate annotated box plots for individual lipid species

- Create volcano plots to visualize magnitude versus statistical significance

- Produce lipid subclass distributions and fatty acyl chain plots [33]

Expected Outcomes: A comprehensive analysis identifying biologically relevant lipid differences between experimental groups, with appropriate handling of analytical challenges specific to lipidomics data.

The Scientist's Computational Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Biology

| Tool/Category | Function | Language |

|---|---|---|

| InMoose | Unified environment for bulk transcriptomic analysis (differential expression, batch correction, meta-analysis) [34] | Python |

| Bioconductor | Comprehensive suite for genomic data analysis (differential expression, sequencing, variant analysis) [36] | R |

| Scanpy/scverse | Single-cell RNA-Seq data analysis (clustering, trajectory inference, visualization) [34] | Python |

| ggplot2 | Grammar of graphics implementation for publication-quality visualizations [36] | R |

| pandas/NumPy | Foundational data manipulation and numerical computing [38] | Python |

| tidyverse | Coherent collection of packages for data manipulation and visualization [36] | R |

| DESeq2/edgeR | Differential expression analysis for RNA-Seq data [36] [34] | R |

| Jupyter Notebook | Interactive computational environment for exploratory analysis [35] | Both |

| Nextflow/nf-core | Workflow management for reproducible, scalable pipelines [37] | Both |

Career Integration and Strategic Skill Application

Industry Application and Professional Expectations

The integration of Python and R skills directly correlates with career advancement in computational biology research. Current industry job postings consistently require proficiency in both languages, with positions at leading pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies emphasizing their application to therapeutic development.

Industry Implementation Context:

- Amgen Senior Scientist Position: Requires "strong programming skills (Python, R, Linux/Unix)" and experience with "single cell omics data" analysis [39]

- Stanford Computational Biologist Role: Seeks candidates with "fluency in Unix and standard programming and data analysis languages (Python, R, or equivalent)" for genomic analysis [40]

- National Laboratory Internships: Provide structured training in "Python, R, and biology" through intensive bootcamps, recognizing their fundamental importance [41]