Computational Biology: The Essential Guide to Methods, Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of computational biology, an interdisciplinary field that uses computational techniques to understand biological systems.

Computational Biology: The Essential Guide to Methods, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of computational biology, an interdisciplinary field that uses computational techniques to understand biological systems. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the field's foundations from its origins to modern applications in genomics, drug discovery, and systems biology. The content details essential algorithms and methodologies, offers best practices for troubleshooting and optimizing computational workflows, and discusses frameworks for validating models and comparing analytical tools. By synthesizing these core intents, the article serves as a critical resource for leveraging computational power to accelerate biomedical research and innovation.

From Turing to Today: Defining the Foundations of Computational Biology

What is Computational Biology? Core Definitions and Distinctions from Bioinformatics

Computational biology is an interdisciplinary field that develops and applies data-analytical and theoretical methods, mathematical modeling, and computational simulation techniques to the study of biological, behavioral, and social systems [1]. It represents a fusion of computer science, applied mathematics, statistics, and various biological disciplines to solve complex biological problems [2] [3].

Core Definitions and Key Distinctions

Computational Biology vs. Bioinformatics: A Comparative Analysis

While the terms are often used interchangeably, subtle distinctions exist in their primary focus and application. The table below summarizes the core differences.

Table 1: Core Distinctions Between Computational Biology and Bioinformatics

| Feature | Computational Biology | Bioinformatics |

|---|---|---|

| Core Focus | Developing theoretical models and computational solutions to biological problems; concerned with the "big picture" of biological meaning [4] [5]. | The process of interpreting and analyzing biological problems posed by the assessment of biodata; focuses on data organization and management [5]. |

| Primary Goal | To build highly detailed models of biological systems (e.g., the human brain, genome mapping) [5] and answer fundamental biological questions [4]. | To record, store, and analyze biological data, such as genetic sequences, and develop the necessary algorithms and databases [5]. |

| Characteristic Activities | - Computational simulations and mathematical modeling [4]- Theoretical model development [3]- Building models of protein folding and motion [5] | - Developing algorithms and databases for genomic data [5]- Analyzing and integrating genetic and genomic data sets [5]- Sequence alignment and homology analysis [3] |

| Typical Data Scale | Often deals with smaller, specific data sets to answer a defined biological question [4]. | Geared toward the management and analysis of large-scale data sets, such as full genome sequencing [4]. |

| Relationship | Often uses the data structures and tools built by bioinformatics to create models and find solutions [5]. | Provides the foundational data and often poses the biological problems that computational biology addresses [5]. |

In practice, the line between the two is frequently blurred. As one expert notes, "The computational biologist is more concerned with the big picture of what’s going on biologically," while bioinformatics involves the "programming and technical knowledge" to handle complex analyses, especially with large data [4]. Both fields are essential partners in modern biological research.

Major Research Domains in Computational Biology

The applications of computational biology are vast and span multiple levels of biological organization, from molecules to entire ecosystems.

Table 2: Key Research Domains in Computational Biology

| Research Domain | Description | Specific Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Anatomy | The study of anatomical shape and form at a visible or gross anatomical scale, using coordinate transformations and diffeomorphisms to model anatomical variations [3]. | Brain mapping; modeling organ shape and form [3]. |

| Systems Biology (Computational Biomodeling) | A computer-based simulation of a biological system used to understand and predict interactions within that system [6]. | Networking cell signaling and metabolic pathways; identifying emergent properties [3] [6]. |

| Computational Genomics | The study of the genomes of cells and organisms [3]. | The Human Genome Project; personalized medicine; comparing genomes via sequence homology and alignment [3]. |

| Evolutionary Biology | Using computational methods to understand evolutionary history and processes [3]. | Reconstructing the tree of life (phylogenetics); modeling population genetics and demographic history [2] [3]. |

| Computational Neuroscience | The study of brain function in terms of its information processing properties, using models that range from highly realistic to simplified [3]. | Creating realistic brain models; understanding neural circuits involved in mental disorders (computational neuropsychiatry) [3]. |

| Computational Pharmacology | Using genomic and chemical data to find links between genotypes and diseases, and to screen drug data [3]. | Drug discovery and development; overcoming data scale limitations ("Excel barricade") in pharmaceutical research [3]. |

| Computational Oncology | The application of computational biology to analyze tumor samples and understand cancer development [3]. | Analyzing high-throughput molecular data (DNA, RNA) to diagnose cancer and understand tumor causation [3]. |

Experimental Protocol: Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Analysis

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biology by allowing researchers to measure gene expression at the level of individual cells. The computational analysis of this data is a prime example of a modern computational biology workflow. The following protocol outlines a detailed methodology for a specific research project that developed "scRNA-seq Dynamics Analysis Tools" [7].

Detailed Computational Methodology

1. Problem Formulation & Experimental Design:

- Objective Definition: Clearly state the biological question. For example: "Identify novel cell types in a tissue," "Trace cell lineage development," or "Understand heterogeneous responses to a drug in a population of cancer cells."

- Experimental Setup: Plan the biological experiment, including cell isolation, library preparation, and sequencing. The number of cells to be sequenced must be determined based on the expected heterogeneity and statistical power requirements.

2. Data Generation & Acquisition:

- Wet-lab Protocol: Isolate single cells using microfluidics or droplet-based technologies (e.g., 10x Genomics). Convert RNA into cDNA and prepare sequencing libraries using standard kits.

- Sequencing: Sequence the libraries on a high-throughput platform (e.g., Illumina). The output is millions of short DNA sequences (reads) corresponding to transcripts from individual cells.

3. Primary Computational Analysis (Bioinformatics Phase):

- Demultiplexing: Assign sequenced reads to the correct sample based on barcodes.

- Quality Control (QC): Use tools like FastQC to assess read quality. Trim adapter sequences and low-quality bases with tools like Cutadapt or Trimmomatic.

- Alignment: Map the cleaned reads to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38 for human) using splice-aware aligners like STAR or HISAT2.

- Quantification: Count the number of reads mapped to each gene for each cell using tools like featureCounts or HTSeq. The output is a digital gene expression matrix (cells x genes).

4. Advanced Computational Analysis (Computational Biology Phase):

- Data Preprocessing:

- Quality Control (Cell-level): Filter out low-quality cells based on metrics like the number of genes detected per cell, total counts per cell, and the percentage of mitochondrial reads. This is typically performed using R (

Seuratpackage) or Python (Scanpypackage). - Normalization: Normalize gene expression counts to account for technical variations (e.g., sequencing depth) using methods like SCTransform in Seurat or

pp.normalize_totalin Scanpy. - Feature Selection: Identify highly variable genes that drive biological heterogeneity.

- Quality Control (Cell-level): Filter out low-quality cells based on metrics like the number of genes detected per cell, total counts per cell, and the percentage of mitochondrial reads. This is typically performed using R (

- Dimensionality Reduction: Project the high-dimensional data into 2 or 3 dimensions for visualization and further analysis using techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA), t-Distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE), or Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP).

- Clustering: Identify groups of cells with similar expression profiles using graph-based clustering (e.g., Louvain algorithm) or k-means. This step is crucial for hypothesizing the existence of distinct cell types or states.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Statistically identify genes that are significantly expressed between clusters or conditions using methods like Wilcoxon rank-sum test or MAST. This provides biological validation for the clusters and identifies marker genes.

- Biological Interpretation & Trajectory Inference: Use the clustering and differential expression results to annotate cell types based on known marker genes. For developmental processes, apply pseudotime analysis tools (e.g., Monocle, PAGA) to reconstruct the dynamic process of cell differentiation and transition.

5. Validation: Correlate computational findings with orthogonal experimental data, such as fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or immunohistochemistry, to confirm the identity and function of computationally derived cell clusters.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Reagents for a scRNA-seq Workflow

| Item | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Single-Cell Isolation Kit (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium) | Partitions individual cells into nanoliter-scale droplets along with barcoded beads, ensuring transcriptome-specific barcoding. |

| Reverse Transcriptase Enzyme | Synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from the RNA template within each cell, creating a stable molecule for amplification and sequencing. |

| Next-Generation Sequencer (e.g., Illumina NovaSeq) | Performs high-throughput, parallel sequencing of the prepared cDNA libraries, generating millions to billions of reads. |

| Reference Genome (e.g., from UCSC Genome Browser) | Serves as the map for aligning short sequencing reads to their correct genomic locations and assigning them to genes. |

| Alignment Software (e.g., STAR) | A splice-aware aligner that accurately maps RNA-seq reads to the reference genome, accounting for introns. |

| Analysis Software Suite (e.g., Seurat in R) | An integrated toolkit for the entire computational biology phase, including QC, normalization, clustering, and differential expression. |

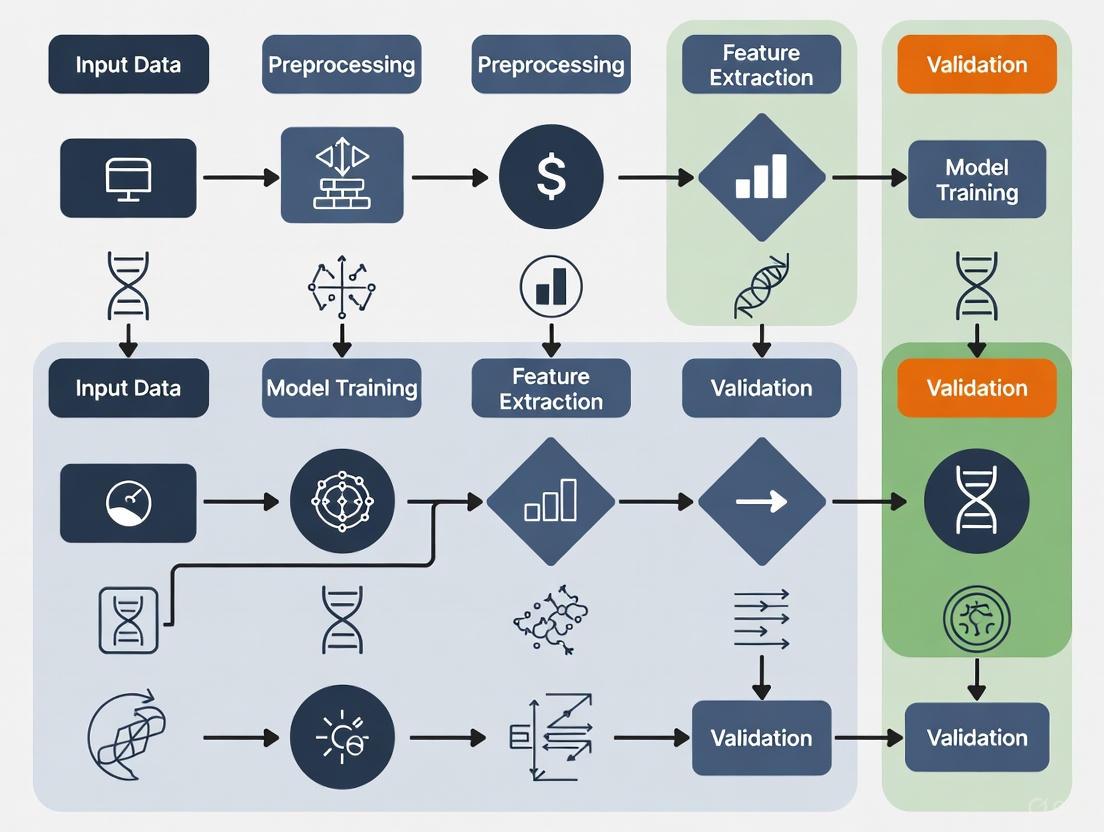

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow and dependencies of the key steps in the single-cell RNA sequencing analysis protocol.

Current Research and Educational Pathways

Current research in computational biology is heavily driven by artificial intelligence and machine learning. Recent studies focus on AI-driven de novo design of enzymes and inhibitors [8], using deep learning for live-cell imaging automation [7], and improving the prediction of protein-drug interactions [9] [10].

Educational programs reflect the field's interdisciplinary nature. Undergraduate and graduate degrees, such as those offered at Brown University [2] and the joint Pitt-CMU PhD program [1], provide rigorous training in both biological sciences and quantitative fields like computer science and applied mathematics, preparing the next generation of scientists to advance this rapidly evolving field.

The past quarter-century has witnessed a profound transformation in biological science, driven by the integration of computational power and algorithmic innovation. This period, bracketed by two landmark achievements—the Human Genome Project (HGP) and the development of AlphaFold—marks the maturation of computational biology from a supplementary tool to a central driver of discovery. These projects exemplify a broader thesis: that complex biological problems are increasingly amenable to computational solution, accelerating the pace of research and reshaping approaches to human health and disease.

The HGP established the foundational paradigm of big data biology, demonstrating that a comprehensive understanding of life's blueprint required not only large-scale experimental data generation but also sophisticated computational assembly and analysis [11] [12]. AlphaFold, emerging years later, represents a paradigm shift toward artificial intelligence (AI)-driven predictive modeling, solving a 50-year-old grand challenge in biology by accurately predicting protein structures from amino acid sequences [13] [14]. Together, these milestones bookend an era of unprecedented progress, creating a new field where computation no longer merely supports but actively leads biological discovery.

The Human Genome Project: The Foundational Data Revolution

Project Conception and Execution

The Human Genome Project was an international, publicly funded endeavor launched in October 1990 with the primary goal of determining the complete sequence of the human genome [11]. This ambitious project represented a fundamental shift toward large-scale, collaborative biology. The initial timeline projected a 15-year effort, but competition from the private sector, notably Craig Venter's Celera Genomics, intensified the race and accelerated the timeline [12] [15]. The project culminated in the first draft sequence announcement in June 2000, with a completed sequence published in April 2003, two years ahead of the original schedule [11] [12].

The computational challenges were immense. The process generated over 400,000 DNA fragments that required assembly into a coherent sequence [15]. The breakthrough came from Jim Kent, a graduate student at UC Santa Cruz, who developed a critical assembly algorithm in just one month, enabling the public project to compete effectively with private efforts [15]. This effort was underpinned by a commitment to open science and data sharing, with the first genome sequence posted freely online on July 7, 2000, ensuring unrestricted access for the global research community [15].

Technical Methodologies and Workflows

The experimental and computational workflow of the HGP involved multiple coordinated stages:

- Sample Preparation and Sequencing: DNA fragments were cloned into bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) and other vectors to create manageable segments for sequencing [12].

- Fragment Sequencing: The initial sequencing used Sanger sequencing methodology, a capillary-based technique that formed the gold standard at the time [12].

- Computational Assembly: Kent's GigAssembler algorithm stitched together the fragmented sequences by identifying overlapping regions, creating a contiguous genome sequence [15].

- Data Annotation and Release: The assembled sequence was annotated with predicted genes and other functional elements and made publicly available through platforms like the UCSC Genome Browser [15].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of the genome sequencing and assembly process:

Quantitative Impact and Legacy

The Human Genome Project established a transformative precedent for large-scale biological data generation. The table below summarizes its key quantitative achievements and the technological evolution it triggered.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of the Human Genome Project

| Metric | Initial Project (2003) | Current Standard (2025) | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time to Sequence | 13 years [12] | ~5 hours [15] | Enabled rapid diagnosis for rare diseases and cancers |

| Cost per Genome | ~$2.7 billion [12] | ~Few hundred dollars [12] | Made large-scale genomic studies feasible |

| Data Output | 1 human genome | 50 petabases of DNA sequenced [12] | Powered unprecedented insights into human health and disease |

| Genomic Coverage | 92% of genome [15] | 100% complete (Telomere-to-Telomere Consortium, 2022) [15] | Provided a complete, gap-free reference for variant discovery |

The project's legacy extends beyond these metrics. It catalyzed new fields like personalized medicine and genomic diagnostics, and demonstrated the power of international collaboration and open data sharing—principles that continue to underpin genomics research [12] [15]. The HGP provided the essential dataset that would later train a new generation of AI tools, including AlphaFold.

The AlphaFold Revolution: AI-Driven Structural Prediction

Solving a 50-Year Grand Challenge

The "protein folding problem"—predicting a protein's precise 3D structure from its amino acid sequence—had been a fundamental challenge in biology for half a century [13] [14]. Proteins, the functional machinery of life, perform their roles based on their unique 3D shapes. While experimental methods like X-ray crystallography could determine these structures, they were often painstakingly slow, taking a year or more per structure and costing over $100,000 each [13] [14].

AlphaFold 2, developed by Google DeepMind, decisively solved this problem in 2020. At the Critical Assessment of protein Structure Prediction (CASP 14) competition, it demonstrated accuracy comparable to experimental methods [13] [14]. This breakthrough was built on a transformer-based neural network architecture, which allowed the model to efficiently establish spatial relationships between amino acids in a sequence [14]. The system was trained on known protein structures from the Protein Data Bank and integrated evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments [14].

Evolution of the AlphaFold Platform

The AlphaFold platform has evolved significantly since its initial release:

- AlphaFold 2 (2020): Achieved atomic-level accuracy in predicting single-protein structures [13] [14].

- AlphaFold Multimer: Extended capabilities to predict structures of multi-protein complexes [14].

- AlphaFold 3 (2024): Represented a major expansion, predicting the structures and interactions of a broad range of biomolecules beyond proteins, including DNA, RNA, ligands, and small molecules [13] [16]. AlphaFold 3 uses a diffusion-based architecture, similar to that in AI image generators, which progressively refines a random distribution of atoms into the most plausible structure [16].

Table 2: Evolution of the AlphaFold Platform and its Capabilities

| Version | Key Innovation | Primary Biological Scope | Performance Claim |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold 2 | Transformer-based attention mechanisms [14] | Single protein structures | Atomic-level accuracy (width of an atom) [14] |

| AlphaFold Multimer | Prediction of multi-chain complexes [14] | Protein-protein complexes | Enabled reliable study of protein interactions |

| AlphaFold 3 | Diffusion-based structure generation [16] | Proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands, etc. | 50%+ improvement on protein interactions; up to 200% in some categories [16] |

Technical Architecture and Workflow

The core innovation of AlphaFold 2 was its ability to model the spatial relationships and physical constraints within a protein sequence. The model employed an "Evoformer" module, a deep learning architecture that jointly processed information from the input sequence and multiple sequence alignments of related proteins, building a rich understanding of evolutionary constraints and residue-residue interactions.

The following diagram outlines the core inference workflow of AlphaFold 2 for structure prediction:

In 2021, DeepMind and EMBL-EBI launched the AlphaFold Protein Database, providing free access to over 200 million predicted protein structures [13]. This resource has been used by more than 3 million researchers in over 190 countries, dramatically lowering the barrier to structural biology [13].

Experimental Validation and Real-World Impact

Key Validation Experiments

The predictive power of AlphaFold has been rigorously validated in both computational benchmarks and real-world laboratory experiments, demonstrating its utility in accelerating biomedical research.

Table 3: Experimental Validations of AlphaFold-Generated Hypotheses

| Research Area | Experimental Protocol | Validation Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Repurposing for AML [17] | 1. AI co-scientist (utilizing AlphaFold) proposed drug repurposing candidates.2. Candidates tested in vitro on AML cell lines.3. Measured tumor viability at clinical concentrations. | Validated drugs showed significant inhibition of tumor viability, confirming therapeutic potential. |

| Target Discovery for Liver Fibrosis [17] | 1. System proposed and ranked novel epigenetic targets.2. Targets evaluated in human hepatic organoids (3D models).3. Assessed anti-fibrotic activity. | Identified targets demonstrated significant anti-fibrotic activity in organoid models. |

| Honeybee Immunity [13] [14] | 1. Used AlphaFold to model key immunity protein Vitellogenin (Vg).2. Structural insights guided analysis of disease resistance.3. Applied to AI-assisted breeding programs. | Structural insights are now used to support conservation of endangered bee populations. |

The Computational Biologist's Toolkit

The shift from the HGP to the AlphaFold era has been enabled by a suite of key reagents, datasets, and software tools that form the essential toolkit for modern computational biology.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools in Computational Biology

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| BAC Vectors [12] | Wet-lab reagent | Clone large DNA fragments (100-200 kb) for stable sequencing. |

| Sanger Sequencer [12] | Instrument | Generate high-quality DNA sequence reads ( foundational for HGP). |

| UCSC Genome Browser [15] | Software/Database | Visualize and annotate genomic sequences and variations. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Database | Repository of experimentally determined 3D structures of biological macromolecules (training data for AlphaFold). |

| AlphaFold Protein DB [13] | Software/Database | Open-access database of 200+ million predicted protein structures. |

| AlphaFold Server [13] | Software Tool | Free platform for researchers to run custom structure predictions. |

The Modern Frontier: AI as a Collaborative Scientist

The trajectory from HGP to AlphaFold has established a new frontier: the development of AI systems that act as active collaborators in the scientific process. Systems like Google's "AI co-scientist," built on the Gemini 2.0 model, represent this new paradigm [17]. This multi-agent AI system is designed to mirror the scientific method itself, generating novel research hypotheses, designing detailed experimental protocols, and iteratively refining ideas based on automated feedback and literature analysis [17].

Laboratory validations have demonstrated this system's ability to independently generate hypotheses that match real experimental findings. In one case, it successfully proposed the correct mechanism by which capsid-forming phage-inducible chromosomal islands (cf-PICIs) spread across bacterial species, a discovery previously made in the lab but not yet published [17]. This illustrates a future where AI does not just predict structures or analyze data, but actively participates in the creative core of scientific reasoning.

The journey from the Human Genome Project to AlphaFold chronicles the evolution of biology into a quantitative, information-driven science. The HGP provided the foundational data layer—the code of life—while AlphaFold and its successors built upon this to create a predictive knowledge layer, revealing how this code manifests in functional forms. This progression underscores a broader thesis: computational biology is no longer a subsidiary field but is now the central engine of biological discovery.

The convergence of massive datasets, advanced algorithms, and increased computational power is ushering in an era of "digital biology." This new era promises to accelerate the pace of discovery across fundamental research, drug development, and therapeutic design, ultimately fulfilling the promise of precision medicine that the Human Genome Project first envisioned a quarter-century ago.

Computational biology represents a fundamental shift in biological research, forged at the intersection of three core disciplines: biology, computer science, and data science. This interdisciplinary field leverages computational approaches to analyze vast biological datasets, generate biological insights, and solve complex problems in biomedicine. The symbiotic relationship between these domains has transformed biology into an information science, where computer scientists develop new analytical methods for biological data, leading to discoveries that in turn inspire new computational approaches [18]. This convergence has become essential in the postgenomic era, where our ability to generate biological data has far outpaced our capacity to process and interpret it using traditional methods [19]. Computational biology now stands as a distinct interdisciplinary field that combines research from diverse areas including physics, chemistry, computer science, mathematics, biology, and statistics, all unified by the theme of using computational tools to extract insight from biological data [18].

The field has experienced remarkable growth, driven by technological advancements and increasing recognition of its value in biological research and drug development. The global computational biology market, valued at $6.34 billion in 2024, is projected to reach $21.95 billion by 2034, expanding at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 13.22% [20]. This growth trajectory underscores the critical role computational approaches now play across the life sciences, from basic research to clinical applications.

Quantitative Landscape: Market Growth and Applications

The expanding influence of computational biology is reflected in robust market growth and diverse application areas. This growth is fueled by increasing demand for data-driven drug discovery, personalized medicine, and genomics research [21]. As biological data from next-generation sequencing becomes more readily available and predictive models are increasingly needed in therapy development and disease diagnosis, computational solutions are becoming the centerpiece of modern life sciences [21].

Table 1: Global Computational Biology Market Projections

| Market Size Period | Market Value | Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) |

|---|---|---|

| 2024 | $6.34 billion | - |

| 2025 | $7.18 billion | 13.22% (2025-2034) |

| 2034 | $21.95 billion | 13.22% (2025-2034) |

Source: Precedence Research [20]

The market exhibits distinct regional variations in adoption and growth potential. North America dominated the global market with a 49% share in 2024, while the Asia Pacific region is estimated to grow at the fastest CAGR of 15.81% during the forecast period between 2025 and 2034 [20]. This geographical distribution reflects differences in research infrastructure, investment patterns, and regulatory environments across global markets.

Table 2: Computational Biology Market by Application and End-use (2024)

| Category | Segment | Market Share | Growth Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Application | Clinical Trials | 28% | Largest application segment |

| Computational Genomics | - | Fastest growing (16.23% CAGR) | |

| End-use | Industrial | 64% | Highest market share |

| Academic & Research | - | Anticipated fastest growth |

Source: Precedence Research [20]

The service landscape is dominated by software platforms, which held a 42% market share in 2024 [20]. This segment's dominance highlights the critical importance of specialized analytical tools and platforms in extracting value from biological data. The ongoing advancements in software development technologies, including AI-powered tools covering areas such as code generation, source code management, software packaging, containerization technologies, and cloud computing platforms are further enhancing scientific discovery processes [20].

Core Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Genome Sequencing and Assembly

Computational biology relies on sophisticated methodologies for processing and interpreting biological data. Genome sequencing, particularly using shotgun approaches, remains a foundational protocol. This technique involves sequencing random small cloned fragments (reads) in both directions from the genome, with multiple iterations to provide sufficient coverage and overlap for assembly [19]. The process employs two main strategies: whole genome shotgun approach for smaller genomes and hierarchical shotgun approach for larger genomes, with the latter utilizing an added step to reduce computational requirements by first breaking the genome into larger fragments in known order [19].

The assembly process typically employs an "overlap-layout-consensus" methodology [19]. Initially, reads are compared to identify overlapping regions using hashing strategies to minimize computational time. When potentially overlapping reads are positioned, computationally intensive multiple sequence alignment produces a consensus sequence. This draft genome requires further computational and manual intervention to reach completion, with some pipelines incorporating additional steps using sequencing information from both directions of each fragment to reconstruct contigs into larger sections, creating scaffolds that minimize potential misassembly [19].

Specialized Computational Tools and Algorithms

Beyond foundational sequencing methods, computational biologists develop specialized algorithms to address specific biological questions. These include tools for analyzing repeats in genomes, such as EquiRep, which identifies repeated patterns in error-prone sequencing data by reconstructing a "consensus" unit from the pattern, demonstrating particular robustness against sequencing errors and effectiveness in detecting repeats of low copy numbers [18]. Such tools are crucial for understanding neurological and developmental disorders like Huntington's disease, Friedreich's ataxia, and Fragile X syndrome, where repeats constitute 8-10% of the human genome and have been closely linked to disease pathology [18].

Another advanced approach involves applying satisfiability solving—a fundamental problem in computer science—to biological questions. Researchers have successfully applied satisfiability to solve the double-cut-and-join distance, which measures large-scale genomic changes during evolution [18]. Such large-scale events, known as genome rearrangements, are associated with various diseases including cancers, congenital disorders, and neurodevelopmental conditions. Studying these rearrangements may identify specific genetic changes that contribute to diseases, potentially aiding diagnostics and targeted therapies [18].

For k-mer based analyses, where k-mers represent fixed-length subsequences of genetic material, structures like the Prokrustean graph enable practitioners to quickly iterate through all k-mer sizes to determine optimal parameters for applications ranging from determining microbial composition in environmental samples to reconstructing whole genomes from fragments [18]. This data structure addresses the computational challenge of selecting appropriate k-mer sizes, which significantly impacts analysis outcomes.

Visualization Principles for Biological Data

Effective data visualization represents a critical methodology in computational biology, requiring careful consideration of design principles. Successful visualizations exploit the natural tendency of the human visual system to recognize structure and patterns through preattentive attributes—visual properties including size, color, shape, and position that are processed at high speed by the visual system [22]. The precision of different visual encodings varies significantly, with length and position supporting highly precise quantitative judgments, while width, size, and intensity offer more imprecise encodings [22].

Color selection follows specific schemas based on data characteristics: qualitative palettes for categorical data without inherent ordering, sequential palettes for numeric data with natural ordering, and diverging palettes for numeric data that diverges from a center value [22]. Genomic data visualization presents unique challenges, requiring consideration of scalability across different resolutions—from chromosome-level structural rearrangements to nucleotide-level variations—and accommodation of diverse data types including Hi-C, epigenomic signatures, and transcription factor binding sites [23].

Visualization tools must balance technological innovation with usability, exploring emerging technologies like virtual and augmented reality while ensuring accessibility for diverse users, including accommodating visually impaired individuals who represent over 3% of the global population [23]. Effective tools make data complexity intelligible through derived measures, statistics, and dimension reduction techniques while retaining the ability to detect patterns that might be missed through computational means alone [23].

Computational biology research relies on a diverse toolkit of software, databases, and analytical resources. These tools form the essential infrastructure that enables researchers to transform raw data into biological insights.

Table 3: Essential Computational Biology Tools and Resources

| Tool Category | Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Analysis | Phred-PHRAP-CONSED [19] | Base calling, sequence assembly, and quality assessment |

| Visualization | JBrowse, IGV, Cytoscape [23] | Genomic data visualization and biological network analysis |

| Specialized Algorithms | EquiRep, Prokrustean graph [18] | Identify genomic repeats and optimize k-mer size selection |

| AI-Powered Platforms | PandaOmics, Chemistry42 [21] | AI-driven drug discovery and compound design |

| Data Resources | NCBI, Ensembl [19] [23] | Access to genomic databases and reference sequences |

The toolkit continues to evolve with emerging technologies, particularly artificial intelligence and machine learning. Different types of AI algorithms—including machine learning, deep learning, natural language processing, and data mining tools—are increasingly employed for analyzing vast biological datasets [20]. Implementation of generative AI models shows promise for predicting 3D molecular structures, generating genomic sequences, and simulating biological systems [20]. These tools are being applied across diverse areas including gene therapy vector design, personalized medicine strategy development, metagenomics and microbiome analysis, protein identification, automated biological image analysis, cancer outcome prediction, and enhancement of gene editing technologies such as CRISPR [20].

Future Directions and Emerging Trends

The future of computational biology is being shaped by several convergent technologies and methodologies. Artificial intelligence and machine learning continue to transform the field, with recent demonstrations including Insilico Medicine's AI-designed drug candidate ISM001-055, developed through proprietary platforms PandaOmics and Chemistry42, advancing to Phase IIa clinical trials for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis [21]. This milestone illustrates how computational modeling and AI-driven compound design can accelerate drug development, moving quickly from target discovery to mid-stage trials while reducing timelines, costs, and risks [21].

The integration of Internet of Things (IoT) technologies with computational biology, termed Bio-IoT, enables collecting, transmitting, and analyzing biological data using sensors, devices, and interconnected networks [20]. This approach finds application in real-time monitoring and data collection, automated experiments, precision healthcare, and translational bioinformatics. Concurrently, rising investments and collaborations among venture capitalists, industries, and governments are fueling development of innovative computational tools with advanced diagnostic and therapeutic capabilities [20].

Educational initiatives are evolving to address the growing need for computational biology expertise. Programs like the Experiential Data science for Undergraduate Cross-Disciplinary Education (EDUCE) initiative aim to progressively build data science competency across several years of integrated practice [24]. These programs focus on developing core competencies including recognizing and defining uses of data science, exploring and manipulating data, visualizing data in tables and figures, and applying and interpreting statistical tests [24]. Such educational innovations are essential for preparing the next generation of scientists to thrive at the intersection of biology, computer science, and data science.

As computational biology continues to evolve, the interdisciplinary pillars of biology, computer science, and data science will become increasingly integrated, driving innovations that transform our understanding of biological systems and accelerate the development of novel therapeutics for human diseases.

Computational biology is an interdisciplinary field that develops and applies data-analytical and theoretical methods, mathematical modeling, and computational simulation techniques to the study of biological systems. The field encompasses a wide range of subdisciplines, each addressing different biological questions using computational approaches. This guide provides an in-depth technical overview of four core subfields—Genomics, Proteomics, Systems Biology, and Computational Neuroscience—framed within the context of contemporary research and drug development. The integration of these domains is accelerating biomarker discovery, clarifying disease mechanisms, and uncovering potential therapeutic targets, ultimately supporting the advancement of precision medicine [25].

Genomics

Genomics involves the comprehensive study of genomes, the complete set of DNA within an organism. Computational genomics focuses on developing and applying analytical methods to extract meaningful biological information from DNA sequences and their variations. This subfield has evolved from initial sequencing efforts to now include functional genomics, which aims to understand the relationship between genotype and phenotype, and structural genomics, which focuses on the three-dimensional structure of every protein encoded by a given genome. The scale of genomic data has grown exponentially, with large-scale projects like the U.K. Biobank Pharma Proteomics Project now analyzing hundreds of thousands of samples, generating unprecedented data volumes that require sophisticated computational tools for interpretation [25].

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: NanoVar for Structural Variant Detection Structural variants (SVs) are large-scale genomic alterations that can have significant functional consequences. NanoVar is a specialized structural variant caller designed for low-depth long-read sequencing data [26].

- Sample Preparation and Sequencing: Extract high-molecular-weight genomic DNA. Prepare a sequencing library according to the long-read sequencing platform's specifications (e.g., Oxford Nanopore or PacBio). Sequence the library to achieve the desired low-depth coverage.

- Quality Assessment and Preprocessing: Assess raw data quality using tools like NanoPlot. Filter and trim reads based on quality scores and length.

- Alignment and SV Calling: Align the processed reads to a reference genome using a compatible aligner. Run NanoVar on the aligned BAM file to detect non-reference insertion variants and other SVs. A key feature of NanoVar is its ability to perform repeat element annotation on inserted sequences.

- Downstream Analysis: Annotate the called SVs with gene information, functional impact predictions, and population frequency data. Visually validate high-confidence SVs using tools like Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV).

Protocol: Single-Cell and Spatial Transcriptomics Analysis This protocol involves the generation and computational analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data to profile gene expression at the level of individual cells [27] [28].

- Single-Cell Isolation and Library Preparation: Dissociate fresh tissue into a single-cell suspension. Viable cells are captured, and libraries are prepared using microfluidic platforms (e.g., 10x Genomics) or plate-based methods. The libraries are then sequenced on a high-throughput platform.

- Primary Data Processing: Demultiplex the raw sequencing data. Align reads to a reference genome and generate a gene expression count matrix, where rows represent genes and columns represent individual cells.

- Quality Control and Normalization: Filter out low-quality cells based on metrics like the number of genes detected per cell and the percentage of mitochondrial reads. Normalize the data to account for technical variation (e.g., sequencing depth).

- Dimensionality Reduction and Clustering: Reduce the high-dimensional data using principal component analysis (PCA). Cluster the cells using graph-based or k-means algorithms to identify putative cell types or states.

- Differential Expression and Biomarker Identification: Identify genes that are differentially expressed between clusters, which serve as potential marker genes for each cell type.

- Spatial Mapping (if applicable): For spatial transcriptomics datasets, the single-cell expression data is mapped back to its original spatial location within the tissue, allowing for the analysis of cellular organization and cell-cell communication [28].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

- Olink Explore HT Platform: An affinity-based proteomics platform used in large-scale genomics-proteomics integration studies to quantify protein targets in blood serum samples. It uses DNA-barcoded antibodies for highly multiplexed protein measurement [25].

- Ultima UG 100 Sequencing Platform: A novel short-read sequencing system that utilizes a large open surface area supported by a silicon wafer instead of conventional flow cells. It is designed for high-throughput, cost-efficient sequencing, making it suitable for population-scale studies [25].

- 10x Genomics Single Cell Reagents: A suite of products for preparing single-cell RNA-seq libraries, enabling the partitioning of individual cells and barcoding of their transcripts for high-throughput profiling.

- NanoVar Software: A specialized computational tool for calling structural variants from low-depth long-read sequencing data, with particular strength in annotating repeat elements in inserted sequences [26].

Genomics Data Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the standard computational workflow for analyzing single-cell RNA sequencing data, from raw data to biological interpretation.

Proteomics

Proteomics is the large-scale study of the complete set of proteins expressed in a cell, tissue, or organism. In contrast to genomics, proteomics captures dynamic events such as protein degradation, post-translational modifications (PTMs), and changes in subcellular localization, providing a more direct view of cellular function [25]. Computational proteomics involves the development of algorithms for protein identification, quantification, and the analysis of complex proteomic datasets. Recent breakthroughs include the development of benchtop protein sequencers, advances in spatial proteomics, and the feasibility of running proteomics at a population scale to uncover associations between protein levels, genetics, and disease phenotypes [25].

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: SNOTRAP for S-Nitrosoproteome Profiling This protocol provides a robust, proteome-wide approach for exploring S-nitrosylated proteins (a key PTM) in human and mouse tissues using the SNOTRAP probe and mass spectrometry [26].

- Sample Preparation and Labeling: Homogenize tissue samples in labeling buffer. Incubate the lysate with the SNOTRAP probe, which selectively reacts with S-nitrosylated cysteine residues.

- Enrichment and Digestion: Capture the labeled proteins using click chemistry-based enrichment on beads. Wash the beads to remove non-specifically bound proteins. On-bead, digest the captured proteins into peptides using trypsin.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Analyze the resulting peptides using nano-liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry (nano-LC-MS/MS). The mass spectrometer records the mass-to-charge ratios and intensities of peptides.

- Data Processing and Protein Identification: Compare the experimental MS/MS spectra to established theoretical spectra in protein databases to identify the peptides and proteins. Quantify the relative abundance of S-nitrosylated proteins across different samples.

Protocol: Mass Photometry for Biomolecular Quantification Mass photometry is a label-free method that measures the mass of individual molecules by detecting the optical contrast they generate when landing on a glass-water interface [26].

- Sample and Microscope Preparation: Clean the glass coverslip thoroughly. Calibrate the mass photometer using proteins of known molecular weight.

- Data Acquisition: Apply a dilute solution of the biomolecular sample (e.g., a protein mixture) to the coverslip. Focus the microscope on the glass-water interface and record a short video of the molecules diffusing into the field of view.

- Image Analysis and Mass Calculation: Software identifies and analyzes the contrast signal generated by each individual molecule. The contrast is proportional to the molecule's mass, allowing the construction of a mass histogram for the entire population.

- Validation: The protocol emphasizes the need to optimize and validate the method for each specific biological system to ensure accurate mass measurement.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

- SomaScan Platform (Standard BioTools): An affinity-based proteomic platform that uses modified nucleotides (SOMAmers) to bind and quantify thousands of proteins simultaneously. It is commonly used in large-scale clinical studies [25].

- Quantum-Si Platinum Pro Benchtop Sequencer: A single-molecule protein sequencer that operates on a laboratory benchtop. It determines the identity and order of amino acids in peptides, providing a different type of data from mass spectrometry or affinity assays [25].

- Phenocycler Fusion Platform (Akoya Biosciences): An imaging-based platform for multiplexed spatial proteomics that uses antibodies with fluorescent readouts to map protein expression in intact tissues [25].

- ANPELA Software: A software package for comparing and assessing the performance of different computational workflows for processing single-cell proteomic data, ensuring the selection of the most appropriate pipeline [26].

Proteomics Technology Comparison

Table 1: Comparison of Major Proteomics Technologies

| Technology | Principle | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Spectrometry [25] | Measures mass-to-charge ratio of ionized peptides. | Discovery proteomics, PTM analysis, quantification. | High accuracy, comprehensive, untargeted. | Expensive instrumentation, requires expertise. |

| Affinity-Based Assays (Olink, SomaScan) [25] | Uses antibodies or nucleotides to bind specific proteins. | High-throughput targeted quantification, biomarker validation. | High multiplexing, good sensitivity, high throughput. | Targeted (pre-defined protein panel). |

| Benchtop Protein Sequencing (Quantum-Si) [25] | Optical detection of amino acid binding to peptides. | Protein identification, variant detection, low-throughput applications. | Single-molecule resolution, no special expertise needed. | Lower throughput compared to other methods. |

| Spatial Proteomics (Phenocycler) [25] | Multiplexed antibody-based imaging on tissue sections. | Spatial mapping of protein expression in intact tissues. | Preserves spatial context, single-cell resolution. | Limited multiplexing compared to sequencing. |

Spatial Proteomics Workflow

The following diagram outlines the key steps in an imaging-based spatial proteomics workflow, which preserves the spatial context of protein expression within a tissue sample.

Systems Biology

Systems biology is an interdisciplinary field that focuses on the complex interactions within biological systems, with the goal of understanding and predicting emergent behaviors that arise from these interactions. It integrates computational modeling, high-throughput omics data, and experimental biology to study biological systems as a whole, rather than as isolated components [29] [30]. A key application is in bioenergy and environmental research, where systems biology aims to understand, predict, manipulate, and design plant and microbial systems for innovations in renewable energy and environmental sustainability [29]. The field relies heavily on mathematical models to represent networks and to simulate system dynamics under various conditions.

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Multiscale Modeling of Brain Activity This computational framework is used to study how molecular changes impact large-scale brain activity, bridging scales from synapses to the whole brain [31].

- Define the Biological Question: Formulate a specific question, such as how an anesthetic drug acting on synaptic receptors leads to changes in brain-wide activity observed in fMRI.

- Model Synaptic Dynamics: Develop biophysically grounded mean-field models that simulate the microscopic action of the drug on specific synaptic receptors (e.g., GABA-A receptors). These models calculate the resulting changes in synaptic currents and neuronal firing rates.

- Upscale to Macroscale Activity: Integrate the local synaptic dynamics into a large-scale brain network model. This model typically consists of multiple interconnected brain regions, with connectivity based on empirical tractography data.

- Simulate and Validate: Run simulations to generate predictions of macroscale brain activity (e.g., fMRI BOLD signals). Compare these simulated signals with empirical data collected under the same conditions (e.g., during anesthesia) to validate the model.

- Model Analysis: Use the validated model to run in silico experiments, such as predicting the effects of different drug doses or mutations in the receptors.

Protocol: MMIDAS for Single-Cell Data Analysis Mixture Model Inference with Discrete-coupled Autoencoders (MMIDAS) is an unsupervised computational framework that jointly learns discrete cell types and continuous, cell-type-specific variability from single-cell omics data [31].

- Data Input: Input a high-dimensional single-cell dataset (e.g., scRNA-seq or multi-omics data) into the MMIDAS framework.

- Joint Learning: The model's variational autoencoder architecture simultaneously performs two tasks: it learns discrete clusters (representing cell types) and continuous latent factors that capture within-cell-type variability (e.g., differentiation gradients or metabolic activity).

- Interpretation: Analyze the learned discrete clusters to define robust cell types. Interrogate the continuous latent factors to understand the biological sources of variability within each cell type, which may relate to processes like cell cycle, stress, or activation.

- Validation: Validate the identified cell types and continuous variations using known marker genes or through comparison with independent datasets.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

- Digital Brain Platform: A computational platform capable of simulating spiking neuronal networks at the scale of the human brain. It can be used to reproduce brain activity signals like BOLD fMRI for both resting state and action conditions [31].

- BAAIWorm: An integrative, data-driven model of C. elegans that simulates closed-loop interactions between the brain, body, and environment. It uses a biophysically detailed neuronal model to replicate locomotive behaviors [31].

- SNOPS (Spiking Network Optimization System): An automatic framework for configuring a spiking network model to reproduce neuronal recordings, used to discover limitations of existing models and guide their development [31].

- T-PHATE Software: A multi-view manifold learning algorithm for high-dimensional time-series data. It is used to embed functional brain imaging data into low dimensions, revealing trajectories through brain states that predict cognitive processing [31].

Multiscale Systems Biology Modeling

The following diagram illustrates the integrative, multiscale approach of systems biology, connecting molecular-level interactions to macroscopic, system-level phenotypes.

Computational Neuroscience

Computational neuroscience employs mathematical models, theoretical analysis, and simulations to understand the principles governing the structure and function of the nervous system. The field spans multiple scales, from the dynamics of single ion channels and neurons to the complexities of whole-brain networks and cognitive processes [31]. Recent research has focused on creating virtual brain twins for personalized medicine in epilepsy, aligning large language models with brain activity during language processing, and using manifold learning to map trajectories of brain states underlying cognitive tasks [31]. These approaches provide a causal bridge between biological mechanisms and observable neural phenomena.

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Creating a Virtual Brain Twin for Epilepsy This protocol involves creating a high-resolution virtual brain twin to estimate the epileptogenic network, offering a step toward non-invasive diagnosis and treatment of drug-resistant focal epilepsy [31].

- Data Acquisition: Acquire multi-modal neuroimaging data from the patient, including structural MRI (sMRI), diffusion-weighted MRI (dMRI) for connectivity, and resting-state functional MRI (fMRI).

- Personalized Brain Network Model: Reconstruct the patient's brain anatomy from the sMRI. Use dMRI tractography to map the structural connectivity between brain regions. Create a large-scale brain network model where each node represents a population of neurons, with its dynamics governed by mean-field models.

- Model Fitting and Seizure Induction: Fit the model parameters to the patient's empirical fMRI data. Then, simulate stimulation across different network nodes to identify which stimulations can induce seizure-like activity in silico. The set of nodes that can induce seizures defines the estimated epileptogenic network.

- Clinical Application: The identified network can inform treatment strategies, such as planning surgical interventions or targeted neuromodulation to disrupt the seizure-generating circuitry.

Protocol: Brain Rhythm-Based Inference (BRyBI) for Speech Processing BRyBI is a computational model that elucidates how gamma, theta, and delta neural oscillations guide the process of speech recognition by providing temporal windows for integrating bottom-up input with top-down information [31].

- Model Architecture: Design a hierarchical neural network model where different levels of speech representation (e.g., features, syllables, words) are processed at different temporal scales, corresponding to brain rhythms (gamma, theta, delta).

- Simulate Rhythmic Activity: Implement oscillatory dynamics in the model to create rhythmic sampling and integration windows. Gamma oscillations may sample acoustic features, theta may chunk syllables, and delta may track prosodic information.

- Input Processing and Prediction: Feed natural speech signals into the model. The model uses the rhythmic activity to dynamically predict context and parse the continuous speech stream into recognizable units.

- Validation: Compare the model's internal activity and its output (e.g., word recognition performance) with empirical data from electrophysiological recordings (e.g., EEG or MEG) during the same speech tasks.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

- Virtual Brain Twin Platform: A personalized modeling platform that uses a patient's own MRI data to create a simulation of their brain, used to map epileptogenic networks and plan treatments [31].

- BRyBI Model: A computational model of speech processing in the auditory cortex that incorporates gamma, theta, and delta neural oscillations to explain how the brain robustly parses continuous speech [31].

- Neural Code Conversion Tools: Deep learning-based methods that align brain activity data across different individuals without the need for shared stimuli, enabling inter-individual brain decoding and visual image reconstruction [31].

- SNOPS (Spiking Network Optimization System): An automatic framework for configuring a spiking network model to reproduce neuronal recordings, used to discover limitations of existing models and guide their development [31].

Virtual Brain Twin Workflow

The following diagram outlines the process of creating and using a personalized virtual brain twin for clinical applications such as epilepsy treatment planning.

Core Algorithms and Transformative Applications in Biomedicine

Computational biology research leverages sophisticated algorithms to extract meaningful patterns from vast biological datasets. Among these, sequence alignment tools, BLAST, and Hidden Markov Models (HMMs) constitute a foundational toolkit, enabling researchers to decipher evolutionary relationships, predict molecular functions, and annotate genomic elements. These methods transform raw sequence data into biological insights, powering applications from drug target identification to understanding disease mechanisms. HMMs, in particular, provide a powerful statistical framework for modeling sequence families and identifying distant homologies that simpler methods miss [32] [33]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these core algorithms, their methodologies, and their practical applications in biomedical research and drug development.

Foundational Sequence Alignment Algorithms

Sequence alignment forms the bedrock of comparative genomics, enabling the identification of similarities between DNA, RNA, or protein sequences. These similarities reveal functional, structural, and evolutionary relationships.

Algorithmic Methodologies and Protocols

Needleman-Wunsch Algorithm: This dynamic programming algorithm performs global sequence alignment, optimal for sequences of similar length where the entire sequence is assumed to be related. It considers all possible alignments to find the optimal one based on a predefined scoring matrix for matches, mismatches, and gaps [34]. The algorithm initializes a scoring matrix, fills it based on maximizing the alignment score, and traces back to construct the optimal alignment.

Smith-Waterman Algorithm: Designed for local sequence alignment, this method identifies regions of local similarity between two sequences without requiring the entire sequences to align. It uses dynamic programming with a similar scoring approach but resets scores to zero for negative values, allowing it to focus on high-scoring local segments. While optimal, it is computationally intensive compared to heuristic methods [34].

Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) Tools: Aligning more than two sequences is an NP-hard problem, leading to heuristic-based tools:

- CLUSTAL: Uses a progressive alignment approach, constructing a guide tree from pairwise distances to determine the alignment order [34].

- MUSCLE: Employs iterative refinement and log-expectation scoring, offering improved speed and accuracy for large datasets [34].

- MAFFT: Utilizes Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to rapidly identify homologous regions, supporting various strategies including iterative refinement [34].

Table 1: Key Sequence Alignment Algorithms and Tools

| Algorithm/Tool | Alignment Type | Core Methodology | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Needleman-Wunsch | Global | Dynamic Programming | Aligning sequences of similar length |

| Smith-Waterman | Local | Dynamic Programming | Finding local regions of similarity |

| CLUSTAL | Multiple | Progressive Alignment | Phylogenetic analysis |

| MUSCLE | Multiple | Iterative Refinement | Large dataset alignment |

| MAFFT | Multiple | Fast Fourier Transform | Sequences with large gaps |

Advanced MSA Post-Processing Methods

Given that MSA is inherently NP-hard and initial alignments may contain errors, post-processing methods have been developed to enhance accuracy. These are categorized into two main strategies [35]:

- Meta-alignment: Integrates multiple independent MSA results to produce a consensus alignment. Tools like M-Coffee build a consistency library from input alignments, weighting character pairs by their consistency, then generate a final MSA that best reflects the consensus [35].

- Realigner: Directly refines a single existing alignment by locally adjusting regions with potential errors. Strategies include:

- Single-type partitioning: One sequence is extracted and realigned against a profile of the remaining sequences.

- Double-type partitioning: The alignment is split into two profiles which are then realigned.

- Tree-dependent partitioning: The alignment is divided based on a guide tree, and the subtrees are realigned [35].

BLAST: Basic Local Alignment Search Tool

BLAST is a cornerstone heuristic algorithm for comparing a query sequence against a database to identify local similarities. Its speed and sensitivity make it indispensable for functional annotation and homology detection.

Experimental Protocol for Protein BLAST (BLASTP)

A standard BLASTP analysis involves the following steps [36]:

- Query Submission: Input a protein sequence (e.g., in FASTA format) into the BLASTP interface.

- Database Selection: Select the target protein database (e.g.,

nr,Swiss-Prot, orClusteredNR). - Parameter Configuration: Adjust parameters (e.g., scoring matrix, expectation threshold) if needed, though defaults are often sufficient.

- Result Analysis: Interpret the output, which includes:

- Score: The bit score, which assesses alignment quality.

- E-value: The probability that the alignment occurred by chance; lower values indicate greater significance.

- Identities: The percentage of identical residues in the alignment.

Advances in BLAST Databases

A significant recent development is the upcoming default shift to the ClusteredNR database for protein BLAST searches. This database groups sequences from the standard nr database into clusters based on similarity, representing each cluster with a single, well-annotated sequence. This offers [37]:

- Faster search times due to reduced database size.

- Decreased redundancy in results, presenting a cleaner output.

- Broader taxonomic coverage per query, increasing the chance of detecting distant homologs.

Hidden Markov Models: Theory and Applications

HMMs are powerful statistical models for representing probability distributions over sequences of observations. In bioinformatics, they excel at capturing dependencies between adjacent symbols in biological sequences, making them ideal for modeling domains, genes, and other sequence features.

Core Concepts and Model Parameters

An HMM is a doubly-embedded stochastic process with an underlying Markov chain of hidden states that is not directly observable, but can be inferred through a sequence of emitted symbols [32] [38]. An HMM is characterized by the parameter set λ = (A, B, π) [32]:

- State Space (Q): The set of all possible hidden states, e.g.,

{q1, q2, ..., qN}. - Observation Space (V): The set of all possible observable symbols, e.g.,

{v1, v2, ..., vM}. - Transition Probability Matrix (A): Defines the probability

aijof transitioning from stateito statej. - Emission Probability Matrix (B): Defines the probability

bj(k)of emitting symbolkwhile in statej. - Initial State Distribution (π): The probability

πiof starting in stateiat timet=1.

The model operates under two key assumptions: the Markov property (the next state depends only on the current state) and observation independence (each observation depends only on the current state) [32].

The Three Canonical Problems of HMMs

HMM applications revolve around solving three fundamental problems [32]:

- Evaluation Problem: Given a model

λand an observation sequenceO, compute the probabilityP(O|λ)that the model generated the sequence. Solved efficiently by the Forward-Backward Algorithm. - Decoding Problem: Given

λandO, find the most probable sequence of hidden statesX. Solved optimally using the Viterbi Algorithm, which employs dynamic programming to find the best path. - Learning Problem: Given

O, adjust the model parametersλto maximizeP(O|λ). This is typically addressed by the Baum-Welch Algorithm, an Expectation-Maximization (EM) algorithm that iteratively refines parameter estimates.

Table 2: HMM Algorithms and Their Applications in Bioinformatics

| HMM Algorithm | Problem Solved | Key Bioinformatics Application |

|---|---|---|

| Forward-Backward | Evaluation | Assessing how well a sequence fits a gene model |

| Viterbi | Decoding | Predicting the most likely exon-intron structure |

| Baum-Welch | Learning | Training a model from unannotated sequences |

HMM Variants and Specialized Applications

Several HMM topologies and variants have been developed to address specific biological problems [33]:

- Profile HMMs: Linear, left-right models with match (M), insert (I), and delete (D) states. They are the foundation of tools like HMMER and databases like Pfam for sensitive homology detection and protein family classification [34] [33].

- Pair HMMs (PHMMs): Generate a pair of sequences and are used for probabilistic pairwise sequence alignment, calculating the probability that two sequences are related [33].

- Generalized HMMs (GHMMs): Also known as hidden semi-Markov models, they allow states to emit segments of symbols of variable length from a non-geometric distribution. This is critical for gene prediction in tools like GENSCAN, as exon lengths are not geometrically distributed [33].

Table 3: Essential Bioinformatics Resources for Algorithmic Analysis

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| NCBI BLAST | Web Tool / Algorithm | Identifies regions of local similarity between sequences; primary tool for homology searching. |

| HMMER | Software Suite | Performs sequence homology searches using profile HMMs; more sensitive than BLAST for remote homologs. |

| Pfam | Database | Collection of protein families, each represented by multiple sequence alignments and profile HMMs. |

| ClusteredNR | Database | Non-redundant protein database of sequence clusters; provides faster BLAST searches with broader taxonomic coverage. |

| SCOPe | Database | Structural Classification of Proteins database; used for benchmarking homology detection methods. |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of bioinformatics algorithms is rapidly evolving. Key trends include:

- Integration of Deep Learning: New methods like the Dense Homolog Retriever (DHR) use protein language models and dense retrieval techniques to detect remote homologs. DHR is alignment-free, making it up to 28,700 times faster than HMMER while achieving superior sensitivity, particularly at the superfamily level [39].

- Hybrid Approaches: Combining the strengths of different algorithms, such as using fast, deep learning-based methods like DHR for initial retrieval followed by rigorous profile-based tools like JackHMMER for multiple sequence alignment construction, creates powerful and efficient pipelines [39].

- Advanced Post-Processing: Continued development of meta-alignment and realigner methods for multiple sequence alignment refines initial results, improving the quality of downstream phylogenetic and structural analyses [35].

Sequence alignment, BLAST, and Hidden Markov Models represent a core algorithmic triad that continues to underpin computational biology research. From their foundational mathematical principles to their sophisticated implementations in tools like HMMER and advanced BLAST databases, these algorithms empower researchers to navigate the complexity of biological data. The ongoing integration with machine learning and the refinement of post-processing techniques ensure that these methods will remain indispensable for driving discovery in genomics, proteomics, and drug development, transforming raw data into profound biological understanding.

Computational biology leverages computational techniques to analyze biological data, fundamentally advancing our understanding of complex biological systems. This field sits at the intersection of biology, computer science, and statistics, enabling researchers to manage and interpret the vast datasets generated by modern high-throughput technologies. The core workflow of genomics research—encompassing genome assembly, variant calling, and gene prediction—serves as a foundational pipeline in this discipline. Genome assembly reconstructs complete genome sequences from short sequencing reads, variant calling identifies differences between the assembled genome and a reference, and gene prediction annotates functional elements within the genomic sequence. Framed within the broader context of computational biology research, this pipeline transforms raw sequencing data into biologically meaningful insights, driving discoveries in personalized medicine, rare disease diagnosis, and evolutionary studies [40]. The integration of long-read sequencing technologies and advanced algorithms has recently propelled these methods to new levels of accuracy and completeness, allowing scientists to investigate previously inaccessible genomic regions and complex variations [41] [42].

Genome Assembly: Reconstructing the Genomic Puzzle

Genome assembly is the process of reconstructing the original DNA sequence from numerous short or long sequencing fragments. This computational challenge is akin to assembling a complex jigsaw puzzle from millions of pieces. Recent advances, particularly in long-read sequencing (LRS) technologies, have dramatically improved the continuity and accuracy of genome assemblies, enabling the construction of near-complete, haplotype-resolved genomes [41].

Technologies and Data Types

The choice of sequencing technology critically influences assembly quality. A multi-platform approach often yields the best results:

- Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) HiFi Sequencing: Generates highly accurate reads (~99.9% accuracy) of 15-20 kilobases (kb) in length. These reads are ideal for resolving complex regions with high base-level precision [41] [42].

- Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) Sequencing: Produces very long reads (10-100 kb, with ultra-long reads exceeding 100 kb). While base-level accuracy is lower than HiFi, the exceptional length is invaluable for spanning long repetitive elements and resolving large structural variations [41] [42].

- Supplementary Data: Assembly is often strengthened by incorporating additional data types:

- Hi-C Sequencing: Captures chromatin interactions to scaffold contigs into chromosomes and resolve haplotypes [41].

- Strand-seq: Provides global phasing information, enabling the separation of maternal and paternal chromosomes [41].

- Bionano Genomics Optical Mapping: Generates long-range restriction maps to validate assembly structure and correct mis-assemblies [42].

Assembly Algorithms and Workflow

Modern assemblers like Verkko and hifiasm automate the process of generating haplotype-resolved assemblies from a combination of LRS data and phasing information [41]. The process can be broken down into several key stages, as shown in the workflow below.

Diagram 1: Workflow for generating a haplotype-resolved genome assembly.

The following table summarizes the experimental outcomes from a recent large-scale study that employed this workflow on 65 diverse human genomes, highlighting the power of contemporary assembly methods [41].

Table 1: Assembly Metrics from a Recent Study of 65 Human Genomes [41]

| Metric | Result (Median) | Description and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Haplotype Assemblies | 130 | Two (maternal and paternal) for each of the 65 individuals. |

| Assembly Continuity (auN) | 137 Mb | Area under the Nx curve; a measure of contiguity (higher is better). |

| Base-Level Accuracy (Quality Value) | 54-57 | A QV of 55 indicates an error rate of about 1 in 3 million bases. |

| Gaps Closed from Previous Assemblies | 92% | Dramatically improves completeness, especially in repetitive regions. |

| Telomere-to-Telomere (T2T) Chromosomes | 39% | Chromosomes assembled from one telomere to the other with no gaps. |

| Completely Resolved Complex Structural Variants | 1,852 | Highlights the ability to resolve structurally complex genomic regions. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Genome Assembly Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for long-read genome assembly.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Circulomics Nanobind CBB Big DNA Kit | Extracts high-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA, critical for long-read sequencing [42]. |

| Diagenode Megaruptor 3 | Shears DNA to an optimal fragment size (e.g., ~50 kb peak) for library preparation [42]. |

| PacBio SRE (Short Read Eliminator) Kit | Removes short DNA fragments to enrich for long fragments, improving assembly continuity [42]. |

| ONT Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSK114) | Prepares sheared HMW DNA for sequencing on Nanopore platforms [42]. |

| ONT R10.4.1 Flow Cell | Nanopore flow cell with updated chemistry for improved base-calling accuracy, especially in homopolymers [42]. |

Variant Calling: Identifying Genomic Variations

Variant calling is the bioinformatic process of identifying differences (variants) between a newly sequenced genome and a reference genome. These variants range from single nucleotide changes to large, complex structural rearrangements. LRS has significantly increased the sensitivity and accuracy of variant detection, particularly for structural variants (SVs) which are often implicated in rare diseases [42].

Variant Types and Detection Methods

The spectrum of genomic variation is broad, and different computational methods are required to detect each type accurately.

- Single Nucleotide Variants (SNVs) and Small Indels: Traditionally detected from short-read data, tools like DeepVariant use deep learning to achieve high accuracy by recognizing patterns in sequencing data [40]. LRS data can also be used, with careful modeling of its distinct error profile.

- Structural Variants (SVs): Defined as variants ≥50 base pairs (bp), SVs include deletions, duplications, insertions, inversions, and translocations. LRS technologies are the gold standard for SV detection because their long reads can span repetitive regions where SVs often occur, enabling precise breakpoint resolution [41] [42].

- Tandem Repeats and Repeat Expansions: These are short DNA sequences repeated head-to-tail. Changes in their number can cause diseases (e.g., Huntington's). LRS reads are long enough to capture entire expanded repeats, making them ideal for detection [42].

A Typical Variant Calling Workflow

A robust variant calling pipeline integrates data from multiple sources and employs multiple callers for comprehensive variant discovery. The following workflow is adapted from studies that successfully used LRS for rare disease diagnosis [42].

Diagram 2: An integrated workflow for comprehensive variant calling using long-read data.

Key Experimental Outcomes

The application of this LRS-based variant calling pipeline in a rare disease cohort of 41 families demonstrated a significant increase in diagnostic yield [42]. Key quantitative results are summarized below.

Table 3: Variant Calling and Diagnostic Outcomes from a Rare Disease Study [42]

| Metric | Result | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Average Coverage | ~36x | Achieved from a single ONT flow cell, demonstrating cost-effectiveness. |

| Completely Phased Protein-Coding Genes | 87% | Enables determination of compound heterozygosity for recessive diseases. |

| Diagnostic Variants Established | 11 probands | Included SVs, SNVs, and epigenetic modifications missed by short-read sequencing. |

| Previously Undiagnosed Individuals | 3 | Showcases the direct clinical impact of LRS-based variant calling. |

| Additional Rare, Annotated Variants | Significant increase vs. SRS | Includes SVs and tandem repeats in regions inaccessible to short reads. |

Gene Prediction and Genome Annotation

Gene prediction, or gene finding, is the process of identifying the functional elements within a genome sequence, particularly protein-coding genes. Accurate annotation is the final step that transforms a raw genome sequence into a biologically useful resource, enabling hypotheses about gene function and regulation.

Methodological Approaches