Confronting Bias in Biological Machine Learning: A Framework for Fair and Robust Models in Biomedicine

As machine learning (ML) becomes integral to biological research and drug development, the pervasive risk of algorithmic bias threatens to undermine the validity and equity of scientific findings and clinical...

Confronting Bias in Biological Machine Learning: A Framework for Fair and Robust Models in Biomedicine

Abstract

As machine learning (ML) becomes integral to biological research and drug development, the pervasive risk of algorithmic bias threatens to undermine the validity and equity of scientific findings and clinical applications. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and professionals on identifying, mitigating, and validating bias in biological ML. Drawing on the latest research, we explore the foundational sources of bias—from skewed biological data to human and systemic origins—and present a structured, lifecycle approach to bias mitigation. We evaluate the real-world efficacy of debiasing techniques, troubleshoot common pitfalls where standard methods fall short, and outline robust validation and comparative analysis frameworks. The goal is to equip practitioners with the knowledge to build more reliable, fair, and generalizable ML models that can truly advance biomedical science and patient care.

Understanding the Roots: How and Where Bias Infiltrates Biological Machine Learning

Defining Algorithmic Bias in a Biological Context

Welcome to the Technical Support Center for Biological Machine Learning. This resource provides practical guidance for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals encountering algorithmic bias in their computational biology experiments. The following FAQs and troubleshooting guides address specific issues framed within our broader thesis on identifying and mitigating bias in biological ML research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary sources of algorithmic bias in biological datasets?

Algorithmic bias in biological contexts typically originates from three main sources [1]:

- Data Bias: Arises from unrepresentative or imbalanced training data. In biological research, this often manifests as the underrepresentation of certain demographic groups (e.g., in genomic datasets) or specific biological conditions (e.g., rare cell types) [2] [3].

- Development Bias: Introduced during model design, including feature selection, algorithm choice, and the modeling process itself, which may perpetuate existing imbalances in the data [4].

- Interaction Bias: Emerges from practice variability between institutions or changes in clinical practice, technology, or disease patterns over time (temporal bias) [1].

FAQ 2: Why does my model perform poorly on data from a new patient cohort or institution?

This is a classic symptom of a domain shift, where the patient cohort in clinical practice differs from the cohort in your training data [4]. It can also be caused by selection bias, where the data collected for model development does not adequately represent the population the model is intended for [3]. For example, if a model is trained predominantly on single-cell data from European donors, it may not generalize well to populations with different genetic backgrounds [2] [5].

FAQ 3: How can a model be accurate overall but still be considered biased?

A model can achieve high overall accuracy by learning excellent predictions for the majority or average population, while simultaneously performing poorly for subgroups that are underrepresented in the training data [6] [4]. This is why evaluating overall performance metrics alone is insufficient; disaggregated evaluation across relevant demographic and biological subgroups is essential [3].

FAQ 4: What is a "feedback loop" and how can it create bias post-deployment?

A feedback loop occurs when an algorithm's predictions influence clinical or experimental practice in a way that creates a new, reinforcing bias [4]. For instance, if a model predicts a lower disease risk for a certain demographic, that group might be tested less frequently. The subsequent lack of data from that group then reinforces the model's initial (and potentially incorrect) low-risk assessment.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Data Bias in Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Studies

Problem: A classification model for cell types, trained on single-cell data, fails to accurately identify rare immune cell populations in validation datasets.

Investigation & Solutions:

| Step | Investigation Action | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Audit Training Data Demographics: Check the genetic ancestry, sex, and age distribution of donor samples. | If certain ancestries are underrepresented, seek to augment data through collaborations or public repositories that serve underrepresented groups [2]. |

| 2 | Quantify Cell Population Balance: Calculate the prevalence of each target cell type in your training set. | For rare cell types, apply algorithmic techniques such as oversampling or cost-sensitive learning to mitigate the class imbalance during model training [4]. |

| 3 | Perform Stratified Evaluation: Evaluate model performance (e.g., F1-score) separately for each cell type, not just as a global average. | This reveals for which specific cell populations the model is failing and guides targeted data collection or re-training [3]. |

Guide 2: Addressing Bias in Drug Response Prediction Models

Problem: A model predicting patient response to a new oncology drug shows high accuracy for male patients but consistently underestimates efficacy in female patients.

Investigation & Solutions:

| Step | Investigation Action | Potential Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify Representation Gaps: Determine the male-to-female ratio in the training data, which may be derived from historically male-skewed clinical trials [7] [2]. | Apply de-biasing techniques during model development, such as adversarial de-biasing, to force the model to learn features that are invariant to the protected attribute (sex) [4]. |

| 2 | Check for Measurement Bias: Investigate if biomarker data or outcome definitions are calibrated differently by sex. | Incorporate Explainable AI (XAI) tools like SHAP to interpret the model. This can reveal if it is relying on spurious sex-correlated features instead of genuine biological signals of drug response [7] [4]. |

| 3 | Validate on External Datasets: Test the model on a balanced, independent dataset with adequate female representation. | Use techniques for continuous learning to safely update the model with new, more representative post-authorization data without forgetting previously learned knowledge [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Bias Mitigation

Protocol 1: Pre-Processing for Representative Data Collection

Aim: To assemble a biological dataset that minimizes sampling bias.

Methodology:

- Population Definition: Clearly define the target population for the model (e.g., "all adults with breast cancer in North America").

- Stratified Sampling Plan: Design a sampling strategy that intentionally includes sufficient representation from key subgroups based on genetic ancestry, sex, age, socioeconomic status, and disease subtypes [2].

- Data Provenance Documentation: For each data sample, record metadata on donor demographics, experimental batch effects, and sample processing protocols [5].

- Synthetic Data Augmentation: For critically underrepresented subgroups, consider generating high-quality synthetic data to improve balance, ensuring the synthetic data accurately reflects the underlying biology of the minority class [7].

Protocol 2: Model Evaluation for Fairness

Aim: To rigorously assess a trained model for performance disparities across subgroups.

Methodology:

- Define Subgroups: Identify relevant protected attributes and subgroups for analysis (e.g., sex, self-reported race, genetic ancestry principal components).

- Disaggregated Evaluation: Calculate performance metrics (e.g., AUC, sensitivity, specificity) separately for each subgroup [3].

- Apply Fairness Metrics: Quantify disparities using metrics such as:

- Equalized Odds: Check if true positive and false positive rates are similar across groups.

- Demographic Parity: Check if the prediction outcome is independent of the protected attribute.

- Statistical Testing: Perform hypothesis tests to determine if observed performance differences between subgroups are statistically significant.

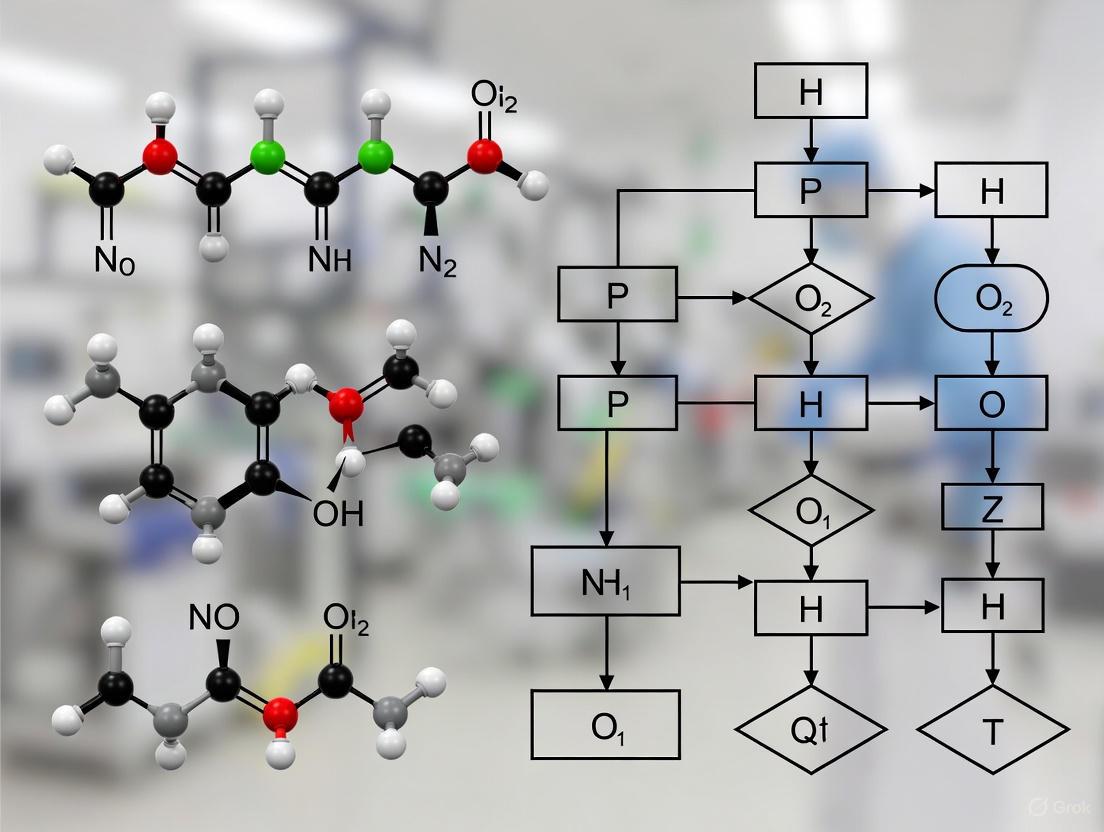

Visualizing the Bias Mitigation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a comprehensive workflow for addressing algorithmic bias throughout the machine learning lifecycle in biological research.

Bias Mitigation in Biological ML Lifecycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational tools and frameworks essential for conducting rigorous bias analysis in biological machine learning.

| Tool / Framework | Function in Bias Mitigation | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|

| PROBAST / PROBAST-ML [4] [3] | A structured checklist and tool for assessing the Risk Of Bias (ROB) in prediction model studies. | Critical for the systematic evaluation of your own models or published models you intend to use. Helps identify potential biases in data sources, sample size, and analysis. |

| SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) / LIME [4] | Explainable AI (XAI) tools that explain the output of any ML model. They show which features (e.g., genes, variants) most influenced a specific prediction. | Used to audit model logic, verify it uses biologically plausible features, and detect reliance on spurious correlations with protected attributes like sex or ancestry. |

| Adversarial De-biasing [4] | A technique during model training where a secondary "adversary" network attempts to predict a protected attribute (e.g., sex) from the main model's predictions. The main model is trained to maximize prediction accuracy while "fooling" the adversary. | Directly used in model development to reduce the model's ability to encode information about a protected attribute, promoting fairness. |

| Synthetic Data Generators (e.g., GANs, VAEs) [7] | Algorithms that generate artificial data instances that mimic the statistical properties of real biological data. | Used to augment underrepresented subgroups in training sets, thereby improving model robustness and fairness without compromising patient privacy. |

| Continuous Learning Frameworks [4] | Methods that allow an ML model to learn continuously from new data streams after deployment without catastrophically forgetting previously learned knowledge. | Essential for updating models with new, more representative data collected post-deployment, thereby adapting to and correcting for discovered biases. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Data Bucket: Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: My model performs poorly on data from a new cell line or patient subgroup.

- Question to Ask: Is my training data representative of the biological diversity the model will encounter?

- Investigation & Solution:

- Audit Your Data: Characterize the sociodemographic and biological sources of your training data. Quantify the representation of different ancestries, sexes, ages, tissue types, and experimental conditions [8] [9].

- Check for Sampling Bias: Ensure data was not collected in a way that over-represents easily accessible samples (e.g., specific cell lines like HEK293) or populations (e.g., European ancestry) [10] [11]. Proper randomization during data collection is key [10].

- Mitigate Imbalance: If imbalances are found, employ data augmentation or oversampling techniques specifically tailored for your biological data type to increase the effective representation of underrepresented groups [12].

Problem: The model is learning from technical artifacts (e.g., batch effects, sequencing platform) instead of the underlying biology.

- Question to Ask: Does my data contain measurement or historical bias?

- Investigation & Solution:

- Identify Confounders: Analyze whether the features used to train the model are imperfect proxies for the actual biological concepts. For example, using gene expression data from different sequencing platforms without correction can introduce measurement bias [13] [14].

- Account for Historical Bias: Recognize that historical biological datasets may reflect past inequities in research focus or funding, leading to an overrepresentation of certain pathways or disease mechanisms [10] [9].

- Preprocess Data: Apply techniques to remove batch effects and normalize data across different sources to mitigate this bias before training [12].

Development Bucket: Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: The model shows high overall accuracy but fails miserably on a specific biological subgroup.

- Question to Ask: Did I evaluate the model using only whole-cohort metrics?

- Investigation & Solution:

- Conduct Subgroup Analysis: Move beyond metrics like overall accuracy or AUC. Systematically evaluate model performance (e.g., precision, recall, F1-score) across all relevant biological and demographic subgroups [12].

- Use Bias-Centered Metrics: Incorporate fairness metrics like equalized odds (which requires similar true positive and false positive rates across groups) or demographic parity into your evaluation framework [9] [13].

- Implement Statistical Debiasing: During model training, use in-processing techniques such as fairness constraints, adversarial debiasing, or fairness-aware optimization functions like MinDiff to penalize performance discrepancies between subgroups [15] [13].

Problem: The model's predictions are skewed because it overfits to a spurious correlation in the training data.

- Question to Ask: Did confirmation bias or implicit bias during feature engineering influence the model?

- Investigation & Solution:

- Challenge Assumptions: Actively look for evidence that contradicts your initial hypotheses about which biological features are most important [10].

- Increase Interpretability: Use explainable AI (XAI) techniques, such as SHAP or LIME, to understand which features the model is using for predictions. This can reveal if it's relying on biologically irrelevant signals [13] [14].

- Apply Regularization: Use regularization techniques during training to penalize model complexity and reduce the chance of overfitting to noisy or biased correlations [13].

Deployment Bucket: Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: After deployment, the model's performance degrades when used in a different clinical site or research institution.

- Question to Ask: Is there a deployment bias due to differences between the development and real-world environments?

- Investigation & Solution:

- Assess Context Shift: Evaluate whether the context in which the model is deployed differs from its training context. This could be different equipment, wet-lab protocols, or patient populations [13].

- Perform Continuous Monitoring: Implement a system for ongoing performance monitoring post-deployment. Track performance metrics across different sites and user groups to quickly identify drops in performance [8] [9].

- Plan for Model Updates: Establish a retraining pipeline with newly collected real-world data to allow the model to adapt to new patterns and prevent performance decay [9].

Problem: Lab researchers over-rely on the model's predictions, ignoring contradictory experimental evidence.

- Question to Ask: Are end-users exhibiting automation bias?

- Investigation & Solution:

- Define Model Scope: Clearly communicate the model's intended use, limitations, and known failure modes to all end-users. Emphasize that it is a decision-support tool, not a replacement for experimental validation [10] [12].

- Design for Collaboration: Instead of fully automated decisions, design the system for human-AI collaboration. Present predictions alongside confidence scores and clear explanations to encourage critical evaluation [12].

- Train Users: Provide training that highlights scenarios where the model may be unreliable and reinforces the importance of expert oversight [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Data Bucket FAQs

Q1: What are the most common data biases in biological ML? The most common biases are representation bias (where datasets overrepresent certain populations, cell lines, or species) [8] [13], historical bias (where data reflects past research inequities or discriminatory practices) [10] [9], and measurement bias (from batch effects, inconsistent lab protocols, or using imperfect proxies for biological concepts) [13] [12].

Q2: How can I quantify representation in my dataset? Create a table to summarize the composition of your dataset. For example:

| Demographic Attribute | Subgroup | Number of Samples | Percentage of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Ancestry | European | 15,000 | 75% |

| African | 2,500 | 12.5% | |

| East Asian | 2,000 | 10% | |

| Other | 500 | 2.5% | |

| Sex | Male | 11,000 | 55% |

| Female | 9,000 | 45% | |

| Cell Type | HEK293 | 8,000 | 40% |

| HeLa | 6,000 | 30% | |

| Other | 6,000 | 30% |

Table 1: Example quantification of dataset representation for a genomic study. This allows you to easily identify underrepresented subgroups [8] [12].

Development Bucket FAQs

Q1: What are some techniques to mitigate bias during model training? You can use in-processing techniques that modify the learning algorithm itself [13]. These include:

- Fairness Constraints: Incorporating constraints that enforce fairness metrics directly into the model's optimization objective [15].

- Adversarial Debiasing: Training a primary model alongside an adversary that tries to predict a sensitive attribute (e.g., ancestry) from the primary model's predictions. This forces the primary model to learn features that are invariant to the sensitive attribute [13] [14].

- Reweighting: Adjusting the weight of examples in the training data to balance the influence of different subgroups [15] [13].

Q2: How should I evaluate my model for bias? Do not rely on a single metric. Use a suite of evaluation techniques [12]:

- Subgroup Analysis: Slice your evaluation data by key biological and demographic attributes and report performance metrics for each slice.

- Fairness Metrics: Calculate metrics like Equalized Odds (ensuring similar false positive and false negative rates across groups) and Demographic Parity (ensuring prediction rates are similar across groups) [9].

- Disparity Metrics: Quantify the disparity in performance. For example, calculate the difference or ratio in error rates between the best-performing and worst-performing subgroups.

| Metric | Formula | Goal | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy Difference | Acc~max~ - Acc~min~ | Minimize | ||||

| Equalized Odds Difference | TPR~Group A~ - TPR~Group B~ | + | FPR~Group A~ - FPR~Group B~ | Minimize | ||

| Demographic Parity Ratio | (Positive Rate~Group A~) / (Positive Rate~Group B~) | Close to 1 |

Table 2: Key metrics for quantifying bias in model evaluation. TPR: True Positive Rate; FPR: False Positive Rate [9].

Deployment Bucket FAQs

Q1: What is an effective way to document our model's limitations for end-users? Creating a Model Card or similar documentation is a best practice [8]. This document should transparently report:

- The intended use cases and domains where the model is validated.

- A detailed breakdown of the model's performance across different subgroups, highlighting any areas where performance is known to degrade.

- The data used for training and evaluation, including its limitations and known biases.

- A description of the model's architecture and any ethical considerations.

Q1: Our model works well in a research setting. What should we check before deploying it in a clinical or production environment? Before deployment, conduct a thorough bias impact assessment [13]. This involves:

- Prospective Validation: Testing the model on a held-out dataset that closely mimics the real-world deployment environment, including new sites, operators, and patient cohorts.

- Adversarial Testing: "Stress-testing" the model with edge cases and underrepresented biological scenarios to uncover hidden failures [14].

- Stakeholder Feedback: Engaging with diverse end-users, including biologists, clinicians, and drug development professionals, to identify potential blind spots and unintended use cases [8] [14].

Experimental Protocols for Bias Assessment

Protocol 1: Auditing a Dataset for Representation Bias

Objective: To quantify the representation of different subgroups in a biological dataset. Materials: Your dataset (e.g., genomic sequences, cell images, patient records) and associated metadata. Methodology:

- Define Relevant Subgroups: Identify the biological and demographic attributes most relevant to your model's task (e.g., genetic ancestry, sex, tissue source, experimental batch).

- Tally Subgroups: For each attribute, count the number of samples belonging to each subgroup.

- Calculate Percentages: Compute the percentage of the total dataset that each subgroup represents.

- Visualize: Create bar charts or pie charts to visualize the distribution.

- Benchmark: Compare your dataset's distribution to the target population or ideal distribution. A significant discrepancy indicates representation bias [8] [12].

Protocol 2: Subgroup Analysis for Model Evaluation

Objective: To evaluate a trained model's performance across different subgroups to identify performance disparities. Materials: A trained model and a labeled test set with metadata for subgroup analysis. Methodology:

- Slice the Test Set: Partition the test set into multiple subsets based on the predefined subgroups (e.g., a test set for European ancestry data, another for African ancestry data).

- Run Inference: Use the model to generate predictions for each subset.

- Calculate Metrics: Compute standard performance metrics (e.g., Accuracy, Precision, Recall, AUC-ROC) for each subset independently.

- Compare and Contrast: Compare the metrics across all subgroups. The largest performance gap between any two subgroups indicates the severity of the bias [9] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Reagent | Function in Bias Mitigation |

|---|---|

| Diverse Cell Line Banks (e.g., HCMI, ATCC) | Provides genetically diverse cell models to combat representation bias in in vitro experiments [8]. |

| Biobanks with Diverse Donor Populations (e.g., All of Us, UK Biobank) | Sources of genomic and clinical data from diverse ancestries to build more representative training datasets [8] [12]. |

| Batch Effect Correction Algorithms (e.g., ComBat, limma) | Software tools to remove technical variation between experimental batches, mitigating measurement bias [12]. |

| Fairness ML Libraries (e.g., TensorFlow Model Remediation, Fairlearn) | Provides pre-implemented algorithms (e.g., MinDiff, ExponentiatedGradient) for bias mitigation during model training [15] [13]. |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Tools (e.g., SHAP, LIME) | Helps interpret model predictions to identify if the model is using spurious correlations or biologically irrelevant features [13] [14]. |

| Model Card Toolkit | Facilitates the creation of transparent documentation for trained models, detailing their performance and limitations [8]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Bias Mitigation Workflow

Three Buckets of Bias

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common human-centric biases I might introduce during dataset creation? During dataset creation, several human-centric biases can compromise your data's integrity. Key ones include:

- Confirmation Bias: The tendency to search for, interpret, and favor information that confirms your pre-existing beliefs or hypotheses [10]. For example, unconsciously discarding data points that contradict your expected outcome.

- Implicit Bias: Making assumptions based on one's own mental models and personal experiences, which may not apply generally [10]. This can affect how data is labeled or what scenarios are considered for data collection.

- Selection Bias: A family of biases where data is selected in a non-representative way. This includes:

2. How can biased datasets impact machine learning models in biological research? Biased datasets can severely undermine the reliability and fairness of your models. Impacts include:

- Poor Generalization: Models may perform well on the data they were trained on but fail when applied to new data from different populations, tissues, or experimental conditions [8].

- Perpetuation of Inequities: If historical data reflects existing societal or research inequities, AI models can learn and amplify these patterns [10] [2]. In biology, this could mean models that are less accurate for underrepresented ancestral groups or specific cell types [5] [2].

- Distorted Biological Interpretations: Biases can cause models to learn technical artifacts or spurious correlations from the data instead of the underlying biology, leading to incorrect scientific conclusions [8].

3. What is the difference between a "real-world distribution" and a "bias" in my data? It is crucial to distinguish between a true bias and a real-world distribution.

- Real-world Distribution: An accurate reflection of natural variation or an existing inequality in the population you are studying. For example, if a specific genetic variant is genuinely more prevalent in a certain population, the dataset should reflect that.

- Bias: A systematic error introduced during data collection, curation, or labeling that distorts this reality. For instance, if a genomic dataset over-represents European ancestry populations not because of biological reality but due to historical research focus, that is a coverage bias [16] [2]. An outcome that accurately mirrors a real-world distribution should not necessarily be labeled as biased.

4. Are there benchmark datasets available that are designed to audit for bias? Yes, the field is moving toward responsibly curated benchmark datasets. A leading example is the Fair Human-Centric Image Benchmark (FHIBE), a public dataset specifically created for fairness evaluation in AI [17]. It implements best practices for consent, privacy, and diversity, and features comprehensive annotations that allow for granular bias diagnoses across tasks like image classification and segmentation [17]. While FHIBE is image-based, it provides a roadmap for the principles of responsible data curation that can be applied to biological data.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing Bias in Your Biological Dataset

This guide helps you identify potential biases at various stages of your dataset's lifecycle.

| Stage | Common Bias Symptoms | Diagnostic Checks |

|---|---|---|

| Data Consideration & Collection | - Dataset over-represents specific categories (e.g., a common cell line, a particular ancestry).- High imbalance in class labels.- Metadata is missing or inconsistent. | - Audit dataset composition against the target population (e.g., use population stratification tools).- Calculate and review class distribution statistics.- Check for correlation between collection batch and experimental groups. |

| Model Development & Training | - Model performance is significantly higher on training data than on validation/test data.- Model performance metrics vary widely across different subgroups in your data. | - Perform stratified cross-validation to ensure performance is consistent across subgroups.- Use fairness metrics (e.g., demographic parity, equality of opportunity) to evaluate model performance per group [8]. |

| Model Evaluation | - Evaluation dataset is sourced similarly to the training data, inflating performance.- Overall high-level metrics (e.g., overall accuracy) hide poor performance on critical minority classes. | - Use a hold-out test set from a completely independent source or study.- Disaggregate evaluation metrics and report performance for each subgroup and intersectional group [8]. |

| Post-Deployment | - Model performance degrades when used on new data from a different lab, institution, or patient cohort. | - Implement continuous monitoring of model performance and data drift in the live environment.- Establish a feedback loop with end-users to flag unexpected model behaviors [8]. |

Guide 2: Mitigating Confirmation and Implicit Bias in Experimental Design

Confirmation and implicit bias often originate in the early, planning stages of research. This protocol provides steps to mitigate them.

Objective: To design a data collection and labeling process that minimizes the influence of pre-existing beliefs and unconscious assumptions.

Materials:

- Pre-registered study protocol document

- Blinding protocols (single-blind or double-blind where possible)

- Standardized Operating Procedures (SOPs) for data annotation

- Diverse, interdisciplinary team for protocol review

Experimental Protocol:

- Pre-registration: Before collecting data, pre-register your experimental hypothesis, methodology, and planned statistical analyses. This commit to an analysis plan reduces "fishing" for significant results later [18].

- Blinded Data Collection and Labeling:

- Where feasible, implement blinding so that the personnel collecting or labeling the data are unaware of the experimental group or the expected outcome.

- For image or sequence data, this could involve randomizing file names and hiding metadata that could influence the annotator.

- Develop Annotation Guidelines:

- Create detailed, unambiguous guidelines for how to label data.

- Pilot these guidelines on a small dataset and refine them based on inter-annotator agreement.

- Adversarial Team Review:

- Have a colleague or a separate team review your experimental design and data collection plan with the explicit goal of finding flaws or potential sources of bias. This practice, similar to a "pre-mortem," helps challenge assumptions [18].

- Diverse Perspective Integration:

- Actively involve colleagues from different scientific backgrounds (e.g., a biologist and a computational scientist) in the design process. This helps identify implicit biases based on a single field's conventions [8].

The following diagram illustrates this mitigation workflow:

Diagram: Mitigation Workflow for Confirmation and Implicit Bias

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key resources for identifying and addressing bias in biological machine learning.

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Bias Mitigation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Bias Assessment Guide [8] | Framework & Guidelines | Provides a structured, biology-specific framework with reflection questions for identifying bias. | Guides interdisciplinary teams through bias checks at all project stages: data, model development, evaluation, and post-deployment. |

| FHIBE (Fair Human-Centric Image Benchmark) [17] | Benchmark Dataset | A publicly available evaluation dataset implementing best practices for consent, diversity, and granular annotations. | Serves as a model for responsible data curation and can be used as a benchmark for auditing fairness in vision-based biological models (e.g., microscopy). |

| Datasheets for Datasets [8] | Documentation Framework | Standardized documentation for datasets, detailing motivation, composition, and collection process. | Promotes transparency and accountability, forcing creators to document potential data biases and limitations for downstream users. |

| REFORMS Guidelines [8] | Checklist | A consensus-based checklist for improving transparency, reproducibility, and validity in ML-based science. | Helps mitigate biases related to performance evaluation, reproducibility, and generalizability across disciplines. |

| Stratified Cross-Validation | Statistical Method | A resampling technique where each fold of the data preserves the percentage of samples for each class or subgroup. | Helps detect selection and sampling bias by ensuring model performance is evaluated across all data subgroups, not just the majority. |

Experimental Protocol: Auditing a Dataset for Group Representation Bias

This protocol provides a concrete methodology to audit your dataset for representation imbalances, a common form of selection and coverage bias.

Objective: To quantitatively assess whether key biological, demographic, or technical groups are adequately and representatively sampled in a dataset.

Materials:

- The dataset (with metadata)

- Statistical software (e.g., R, Python with pandas)

- Visualization libraries (e.g., matplotlib, seaborn)

Methodology:

- Define Relevant Groups:

- Identify the subgroups critical to your research question. These could be based on:

- Biology: Ancestry, sex, tissue type, cell lineage.

- Experiment: Laboratory of origin, batch number, sequencing platform.

- Clinical: Disease subtype, treatment cohort.

- Identify the subgroups critical to your research question. These could be based on:

- Quantify Group Frequencies:

- Calculate the number and proportion of samples belonging to each defined group.

- Output: Create a summary table.

- Compare to a Reference:

- Compare the group proportions in your dataset to a reference standard. This could be the global population distribution, the disease prevalence in a target population, or an ideal balanced design.

- Visualize Disparities:

- Generate bar charts or pie charts to visualize the composition of your dataset versus the reference distribution. This makes imbalances immediately apparent.

- Report and Act:

- Document the findings. If significant under-representation is found, state this as a key limitation. Develop a strategy to address the imbalance, which could include targeted data collection, data synthesis techniques, or applying algorithmic fairness methods in subsequent modeling.

The logical relationship and workflow for this audit is as follows:

Diagram: Dataset Audit Workflow for Group Representation Bias

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Mitigating Biases

Q1: What are the most common categories of bias in biological datasets, particularly for machine learning?

Biases in biological data are typically categorized into three main types, which can significantly impact the performance and fairness of machine learning models [1].

- Data Bias: Arises from the training data itself. This includes issues like unrepresentative sampling, measurement errors, or under-representation of certain population subgroups.

- Development Bias: Introduced during model creation through choices in feature engineering, algorithm selection, or study design.

- Interaction Bias: Emerges after deployment, often due to changes in clinical practice, technology, or disease patterns over time (temporal bias) [1].

Q2: Our model for Alzheimer's disease classification performs well on our test set but generalizes poorly to new hospital data. What could be wrong?

This is a classic sign of batch effects and sampling bias. Batch effects are technical variations introduced when data are generated in different batches, across multiple labs, sequencing runs, or days [19]. If your training data does not represent the demographic, genetic, or technical heterogeneity of the broader population, the model will fail to generalize.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Audit Your Data: Check the distribution of key demographic (age, gender, race) and technical (scanning protocol, sequencing batch) variables in your training set versus the real-world population.

- Check for Confounding: Determine if your phenotype of interest is perfectly correlated with a batch. For example, if all control samples were processed in one lab and all disease samples in another, the model may learn to distinguish the lab instead of the disease [19].

- Apply Batch Correction: Use computational methods like Limma's RemoveBatchEffects, ComBat, or SVA to remove technical variation before model training [19]. A balanced study design, where phenotype classes are equally distributed across batches, is the best prevention.

Q3: We use historical biodiversity records to model species distribution. How reliable are these data for predicting current ranges?

Historical data can suffer from severe temporal degradation, meaning its congruence with current conditions decays over time [20]. Relying on it uncritically can lead to inaccurate models.

- Primary Causes of Temporal Degradation [20]:

- Natural Dynamics: Local extinctions, species turnover, and immigration events change community composition.

- Taxonomic Revisions: Scientific understanding of species relationships evolves, making old records taxonomically obsolete.

- Data Loss: Physical specimens and associated metadata can be lost due to poor curation or funding shortfalls.

- Solution: A study on African plants found that a majority of well-surveyed grid cells contained predominantly pre-1970 records and urgently needed re-sampling [20]. Always assess the temporal bias of your dataset and, if possible, combine historical data with contemporary validation surveys.

Q4: What pitfalls should we avoid when using mixed-effects models to account for hierarchical biological data?

Mixed-effects models are powerful for handling grouped data (e.g., cells from multiple patients, repeated measurements), but they come with perils.

- Common Pitfalls and Solutions [21]:

| Pitfall | Description | Consequence | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Too Few Random Effect Levels | Fitting a variable like "sex" (with only 2 levels) as a random effect. | Model degeneracy and biased variance estimation. | Fit the variable as a fixed effect instead. |

| Pseudoreplication | Using group-level predictors (e.g., maternal trait) without accounting for multiple offspring from the same mother. | Inflated Type I error (false positives). | Ensure the model hierarchy correctly reflects the experimental design. |

| Ignoring Slope Variation | Assuming all groups have the same response to a treatment (random intercepts only). | High Type I error if groups actually vary in their response. | Use a random slopes model where appropriate. |

| Confounding by Cluster | A group-level (e.g., site) variable is correlated with a fixed effect (e.g., disturbance level). | Biased parameter estimates for both fixed and random effects. | Use within-group mean centering for the covariate. |

Reference Tables: Bias Typology and Metrics

Table 1: Categories and Sources of Bias in Integrated AI-Models for Medicine [1].

| Bias Category | Specific Source | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Data Bias | Training Data | Unrepresentative or skewed data used for model development. |

| Reporting Bias | Systematic patterns in how data is reported or recorded. | |

| Development Bias | Algorithmic Bias | Bias introduced by the choice or functioning of the model itself. |

| Feature Selection | Bias from how input variables are chosen or engineered. | |

| Interaction Bias | Temporal Bias | Model performance decays due to changes in practice or disease patterns. |

| Clinical Bias | Arises from variability in practice patterns across institutions. |

Table 2: Metrics for Quantifying Spatial, Temporal, and Taxonomic Biases in Biodiversity Data [22].

| Bias Dimension | Metric | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial | Nearest Neighbor Index (NNI) | Measures the clustering or dispersion of records in geographical space. |

| Taxonomic | Pielou's Evenness | Quantifies how evenly records are distributed across different species. |

| Temporal | Species Richness Completeness | Assesses the proportion of expected species that have been recorded. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Bias Mitigation.

| Tool / Method | Function | Field of Application |

|---|---|---|

| Limma's RemoveBatchEffects [19] | Removes batch effects using a linear model. | Genomics, Transcriptomics (e.g., microarray, RNA-seq) |

| ComBat [19] | Empirical Bayes method for batch effect correction. | Multi-site Omics studies |

| SVA (Surrogate Variable Analysis) [19] | Identifies and adjusts for unknown sources of variation. | Omics studies with hidden confounders |

| NPmatch [19] | Corrects batch effects through sample matching & pairing. | Omics data integration |

| Seurat [23] | R package for single-cell genomics; includes data normalization, scaling, and integration functions. | Single-Cell RNA-seq |

| Generalized Additive Models (GAMs) [22] | Used to model and understand the environmental drivers of bias. | Ecology, Biodiversity Informatics |

| Mixed-Effects Models (GLMM) [21] | Accounts for non-independence in hierarchical data. | Ecology, Evolution, Medicine |

Experimental Workflow Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates a general workflow for identifying and mitigating bias in biological datasets, applicable to various data types.

Bias Mitigation Workflow

The diagram below details a specific workflow for processing single-cell RNA-sequencing data, highlighting stages where analytical pitfalls are common.

scRNA-seq Analysis Pitfalls

FAQ: Frequently Asked Questions

Q: Can machine learning models ever be truly unbiased? A: Yes, with careful methodology. A 2023 study on brain diseases demonstrated that when models are trained with appropriate data preprocessing and hyperparameter tuning, their predictions showed no significant bias across subgroups of gender, age, or race, even when the training data was highly imbalanced [24].

Q: Are newer, digital field observations better than traditional museum specimens for biodiversity studies? A: Both have flaws and strengths. Digital observations are abundant but suffer from spatial bias (e.g., oversampling near roads), taxonomic bias (favoring charismatic species), and temporal bias. Museum specimens provide enduring physical evidence but are becoming scarcer and also have geographic gaps. The best approach is to use both while understanding their respective biases [25].

Q: In metabolomics, why does one metabolite produce multiple signals in my LC-MS data? A: A single metabolite can generate multiple signals due to [26]:

- Adducts: Formation of different ionic species like [M+H]+, [M+Na]+, [M-H]-.

- In-source fragmentation: Loss of small molecules (e.g., water, ammonia) in the ion source before analysis.

- Isotopic peaks: Natural presence of heavier isotopes like 13C or 15N. This complexity must be considered during the peak annotation and metabolite identification process to avoid misidentification.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common types of bias that can affect a retinal image analysis model for hypertension? Performance disparities in retinal image models often stem from several specific biases introduced during the AI model lifecycle [9].

- Representation Bias: This occurs when the training dataset does not adequately represent the full spectrum of the patient population. For example, if a model is trained primarily on retinal images from individuals of a single ethnic group, it may perform poorly on images from other ethnicities due to variations in retinal pigmentation or vessel structure [9] [27].

- Label Bias: This bias arises from inaccuracies or inconsistencies in the ground truth labels used for training. In hypertensive retinopathy (HR), label bias can occur if the severity grades (mild, moderate, severe) assigned to retinal images by ophthalmologists are inconsistent, causing the model to learn from unreliable patterns [9].

- Systemic and Implicit Bias: These are human-origin biases that can be baked into the model. Systemic bias may manifest as unequal access to ophthalmologic care, leading to under-representation of lower socioeconomic groups in training data. Implicit bias can affect how developers select data or features, potentially overemphasizing certain patterns that confirm pre-existing beliefs [9].

Q2: Our model achieves high overall accuracy but performs poorly on a specific patient subgroup. How can we diagnose the root cause? This is a classic sign of performance disparity. The following diagnostic protocol can help identify the root cause.

- Step 1: Disaggregate Model Performance: Do not rely on aggregate metrics like overall accuracy. Calculate performance metrics (sensitivity, specificity, F1-score) separately for each patient subgroup defined by attributes like race, ethnicity, sex, and age [9]. A significant drop in metrics for a specific subgroup indicates a problem.

- Step 2: Interrogate the Training Data: Analyze the composition of your training dataset. Use the table below to check for representation bias. A significant imbalance often points to the core issue [9] [27].

| Patient Subgroup | Percentage in Training Data | Model Sensitivity (Subgroup) | Model Specificity (Subgroup) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subgroup A | 45% | 92% | 88% |

| Subgroup B | 8% | 65% | 72% |

| Subgroup C | 32% | 90% | 85% |

| Subgroup D | 15% | 89% | 87% |

- Step 3: Analyze Feature Extraction: For retinal image models, investigate if key biomarkers like the Arterio-Venular Ratio (AVR) or vessel tortuosity are being computed consistently across all subgroups. Inconsistent segmentation or classification of arteries and veins in certain image types can lead to skewed AVR calculations and erroneous HR grading [28].

Q3: What practical steps can we take to mitigate bias in our hypertension risk prediction models? Bias mitigation should be integrated throughout the AI lifecycle. Here are key strategies:

- Preprocessing Techniques: Before training, apply algorithmic methods to your dataset. This includes reweighing, where instances from underrepresented subgroups are given higher weight, and relabeling, which corrects for noisy or biased labels in the training data [27].

- Use Diverse and Standardized Data: Actively source data from multiple institutions and demographics. Advocate for the use of standardized imaging formats like DICOM for retinal images, as this improves data quality and interoperability, which is crucial for building robust models [29].

- Adopt a "Human-in-the-Loop" Approach: Integrate domain expertise into the model development and validation process. Having clinicians review model predictions, especially for edge cases and underrepresented subgroups, can help identify and correct biases that pure data-driven approaches might miss [27].

- Implement Updated Clinical Metrics: For hypertension models, ensure you are using the most current and equitable risk assessment tools. The new PREVENT Equation, for example, was developed to improve risk prediction across diverse racial and ethnic groups compared to its predecessor [30].

Q4: What are the key quantitative biomarkers in retinal images for grading Hypertensive Retinopathy (HR), and how are they calculated?

AI-based retinal image analysis for HR relies on several quantifiable biomarkers. The primary metric is the Arterio-Venular Ratio (AVR), which is calculated as follows [28]:

AVR = Average Arterial Diameter / Average Venous Diameter

This calculation involves a technical workflow of vessel segmentation, artery-vein classification, and diameter measurement. The AVR value is then used to grade HR severity, with a lower AVR indicating more severe disease [28]. The table below summarizes the HR stages based on AVR.

| HR Severity Stage | Key Diagnostic Features | Associated AVR Range |

|---|---|---|

| No Abnormality | Retinal examination appears normal. | 0.667 - 0.75 |

| Mild HR | Moderate narrowing of retinal arterioles. | ~0.5 |

| Moderate HR | Arteriovenous nicking, hemorrhages, exudates. | ~0.33 |

| Severe HR | Cotton-wool spots, extensive hemorrhages. | 0.25 - 0.3 |

| Malignant HR | Optic disc swelling (papilledema). | ≤0.2 |

Other critical biomarkers include vessel tortuosity (quantifying the twisting of blood vessels) and the presence of lesions like hemorrhages and exudates [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and computational tools for research in this field.

| Item Name | Function / Explanation | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| DICOM-Standardized Retinal Datasets | Publicly available, standards-compliant datasets (e.g., AI-READI) that include multiple imaging modalities (color fundus, OCT, OCTA). | Ensures data interoperability and quality, providing a foundational resource for training and validating models fairly [29]. |

| U-Net Architecture | A convolutional neural network designed for precise biomedical image segmentation. | Used for accurate retinal vessel segmentation, which is the critical first step for computing AVR and tortuosity [28]. |

| PREVENT Equation | A newer cardiovascular risk calculation that removes race as a variable in favor of zip code-based social deprivation indices. | Used to build more equitable hypertension risk models and to assess patient risk without propagating racial bias [30]. |

| Bias Mitigation Algorithms (Preprocessing) | Computational techniques like reweighing and relabeling applied to the training data before model development. | Directly addresses representation and label bias to improve model fairness across subgroups [27]. |

| Color Contrast Analyzer (CCA) | A tool for measuring the contrast ratio between foreground and background colors. | Critical for ensuring that all data visualizations and model explanation interfaces are accessible to all researchers, including those with low vision [31]. |

Experimental Workflow for Bias Assessment

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and mitigating bias in a biological machine learning model.

A Lifecycle Strategy: Practical Frameworks for Bias Mitigation in ML Projects

Introducing the ACAR and Biological Bias Assessment Guide Frameworks

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My machine learning model for toxicity prediction performs well on the training data but generalizes poorly to new compound libraries. What could be the issue?

This is a classic sign of dataset bias [7]. The issue likely stems from your training data not being representative of the broader chemical space you are testing.

- Root Cause: The training set may lack diversity, containing compounds with similar structural scaffolds or properties, while your new library introduces different chemotypes [7].

- Solution:

- Audit Your Data: Use explainable AI (xAI) techniques to identify which molecular features your model is over-relying on for predictions [7].

- Data Augmentation: Enrich your training dataset with synthetically generated compounds that represent underrepresented regions of chemical space [7].

- Re-balance: Strategically add experimental data for novel scaffolds to create a more balanced and representative training set.

Q2: During the validation of a new predictive model for drug-target interaction, how can I systematically assess potential biases in the underlying experimental data?

A structured bias assessment framework is crucial. The following protocol adapts established clinical trial bias assessment principles for computational biology [32].

Experimental Protocol: Bias Assessment for Drug-Target Interaction Data

- Define the Effect of Interest: Clearly state whether you are estimating the effect of conducting an experiment (intention-to-treat) or the effect under perfect adherence to a protocol (per-protocol) [32].

- Domain-Based Risk Assessment: Evaluate the risk of bias across these key domains:

- Bias from the Experimental Process: Was the assay run blindly? Were positive and negative controls assigned randomly across plates? [32]

- Bias from Deviations from Intended Protocols: Are there systematic differences in how protocols were applied to different compound classes? (e.g., some compounds require solvent DMSO while others use water, leading to measurement inconsistencies).

- Bias due to Missing Outcome Data: Are there compounds for which readouts failed? Is this failure random, or is it related to the compound's properties (e.g., solubility, fluorescence)? [32]

- Bias in Measurement of the Outcome: Was the same assay kit and equipment used for all data points? Were measurement thresholds changed during data collection?

- Bias in Selection of the Reported Result: Is the reported dataset the complete set of experiments, or was there selective reporting of only "successful" or "strong" interactions? [32]

- Judgement and Justification: For each domain, judge the risk of bias as 'Low', 'High', or with 'Some Concerns'. Justify judgements with evidence from the experimental records [32].

Q3: Our AI model for patient stratification in a specific disease shows significantly different performance metrics across sex and ethnicity subgroups. How can we diagnose and correct this?

This indicates your model is likely amplifying systemic biases present in the training data [7].

- Diagnosis with xAI:

- Use model interpretability tools (e.g., SHAP, LIME) to analyze if the model's predictions are disproportionately influenced by features correlated with sex or ethnicity rather than genuine biological signals of the disease [7].

- Perform a counterfactual analysis: "How would the prediction change if the patient's data indicated a different demographic subgroup?" This can reveal unfair dependencies [7].

- Mitigation Strategies:

- Pre-processing: Apply techniques to re-weight or resample the training data to ensure all subgroups are equally represented [7].

- In-processing: Use fairness-aware algorithms that incorporate constraints to penalize model performance disparities across subgroups during training.

- Post-processing: Adjust decision thresholds for different subgroups to equalize performance metrics like false positive rates.

Q4: What are the essential "reagent solutions" or tools needed to implement a rigorous biological bias assessment in an AI for drug discovery project?

The following table details key methodological tools and their functions for ensuring robust and unbiased AI research.

Research Reagent Solutions for Bias Assessment

| Item/Reagent | Function in Bias Assessment |

|---|---|

| Explainable AI (xAI) Tools | Provides transparency into AI decision-making, allowing researchers to dissect the biological and clinical signals that drive predictions and identify when spurious correlations (bias) may be corrupting results [7]. |

| Cochrane Risk of Bias (RoB 2) Framework | Provides a structured tool with fixed domains and signaling questions to systematically assess the risk of bias in randomized trials or experimental data generation processes [32]. |

| Synthetic Data Augmentation | A technique to generate artificial data points to balance underrepresented biological scenarios or demographic groups in training datasets, thereby reducing bias during model training [7]. |

| Algorithmic Auditing Frameworks | A set of procedures for the continuous monitoring and evaluation of AI systems to identify gaps in data coverage, ensure fairness, and validate model generalizability across diverse populations [7]. |

| ADKAR Change Management Model | A goal-oriented framework (Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability, Reinforcement) to guide research teams and organizations in adopting new, bias-aware practices and sustaining a culture of rigorous validation [33] [34]. |

Experimental Protocol for Implementing the Biological Bias Assessment Guide

This detailed methodology provides a step-by-step approach for auditing an AI-driven drug discovery project for biological bias.

Pre-Assessment and Scoping

- Define the Outcome: Select a specific result from your AI model to assess (e.g., prediction of compound efficacy for a specific target) [32].

- Gather Documentation: Collect all available information on the training data sources, model architecture, preprocessing steps, and validation results.

Domain-Based Evaluation

- Systematically work through the five domains of bias listed in the troubleshooting section (Q2). For each domain, answer specific signaling questions (e.g., "Was the data generation process the same for all compound classes?") with "Yes", "Probably yes", "Probably no", "No", or "No information" [32].

- Use the answers to propose a risk-of-bias judgement for each domain ('Low', 'High', 'Some concerns').

Overall Judgement and Reporting

- The overall risk of bias for the result is based on the least favourable assessment across the domains [32].

- Document all judgements and their justifications in a free-text summary. Optionally, predict the likely direction of the bias (e.g., "The model is likely to overestimate efficacy for compounds similar to those in the overrepresented scaffold Class A") [32].

Workflow and Logical Relationship Diagrams

The following diagrams illustrate the logical relationships and workflows described in the frameworks.

Diagram 1: ACAR Framework Workflow

Title: ACAR Framework Cyclical Workflow

Diagram 2: Bias Assessment & Mitigation Pathway

Title: AI Bias Diagnosis and Mitigation Pathway

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the class imbalance problem and why is it critical in biological ML? Class imbalance occurs when the number of samples in one class significantly outweighs others, causing ML models to become biased toward the majority class. In biological contexts like oncology, this is the rule rather than the exception, where models may treat minority classes as noise and misclassify them, leading to non-transferable conclusions and compromised clinical applicability [35]. The degree of imbalance can be as severe as 1:100 or 1:1000 in medical data, making it a pressing challenge for reproducible research [35].

Why are standard accuracy metrics misleading with imbalanced data? Using accuracy metrics with imbalanced datasets creates a false sense of success because classifiers can achieve high accuracy by always predicting the majority class while completely failing to identify minority classes [36]. For example, a model might achieve 99% accuracy on a spam detection problem by simply classifying everything as spam, but it would miss all legitimate emails, making it useless in practice [36].

What are the main types of missing data mechanisms? Missing data falls into three primary categories based on the underlying mechanism: Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), where missingness is independent of any data; Missing at Random (MAR), where missingness depends on observed variables; and Missing Not at Random (MNAR), where missingness depends on unobserved factors or the missing values themselves [37]. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for selecting appropriate handling methods.

Which resampling technique should I choose for my dataset? The choice depends on your dataset characteristics and research goals. Oversampling techniques like SMOTE work well when you have limited minority class data but risk overfitting if noisy examples are generated [38]. Undersampling is suitable for large datasets but may discard valuable information [36]. No single method consistently outperforms others across all scenarios, so experimental comparison is essential [39].

How do I evaluate imputation method performance? Use multiple metrics to comprehensively evaluate imputation performance. Common metrics include Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) and Mean Absolute Error (MAE) to quantify differences between imputed and actual values [37]. Additionally, consider bias, empirical standard error, and coverage probability, especially for healthcare applications where subgroup disparities matter [40].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model consistently ignores minority class predictions

Diagnosis: This typically indicates severe class imbalance where the model optimization favors the majority class due to distribution skew [35] [39].

Solution: Apply resampling techniques before training:

Start with simple resampling:

- Random oversampling: Duplicate minority class instances

- Random undersampling: Remove majority class instances randomly [36]

Progress to advanced methods:

Validate with appropriate metrics:

- Use F1-score, geometric mean, or Matthews Correlation Coefficient instead of accuracy [39]

- Check performance on validation set with similar imbalance characteristics

Prevention: Always analyze class distribution during exploratory data analysis and implement resampling as part of your standard preprocessing pipeline when imbalance ratio exceeds 4:1 [36].

Problem: Poor model performance after handling missing data

Diagnosis: The chosen imputation method may not match your missing data mechanism or may introduce bias [37] [40].

Solution: Implement a systematic imputation strategy:

Identify missing data mechanism:

- Use statistical tests like Little's MCAR test

- Analyze patterns in missingness across variables [37]

Select mechanism-appropriate methods:

Evaluate imputation quality:

Prevention: Document missing data patterns thoroughly and test multiple imputation methods with different parameters to identify the optimal approach for your specific dataset.

Data Handling Method Comparison

Resampling Techniques for Imbalanced Data

| Method | Type | Mechanism | Best For | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Random Oversampling | Oversampling | Duplicates minority instances | Small datasets | Simple to implement, preserves information | High risk of overfitting [36] |

| SMOTE | Oversampling | Creates synthetic minority instances | Moderate imbalance | Reduces overfitting, improves generalization | Can generate noisy samples, struggles with high dimensionality [38] |

| Borderline-SMOTE | Oversampling | Focuses on boundary instances | Complex decision boundaries | Improves classification boundaries, more targeted approach | Computationally intensive [38] |

| Random Undersampling | Undersampling | Randomly removes majority instances | Large datasets | Fast execution, reduces computational cost | Potential loss of useful information [36] |

| NearMiss | Undersampling | Selects majority instances based on distance | Information-rich datasets | Preserves important majority instances, multiple versions available | Computationally expensive for large datasets [36] |

| Tomek Links | Undersampling | Removes borderline majority instances | Cleaning overlapping classes | Improves class separation, identifies boundary points | Primarily a cleaning method, may not balance sufficiently [36] |

| Cluster Centroids | Undersampling | Uses clustering to select majority instances | Datasets with natural clustering | Preserves dataset structure, reduces information loss | Quality depends on clustering algorithm [36] |

Missing Data Imputation Methods

| Method | Category | Mechanism | Best For | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean/Median/Mode | Single Imputation | Replaces with central tendency | MCAR (limited use) | Simple, fast | Ignores relationships, introduces bias [37] |

| k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) | ML-based | Uses similar instances' values | MAR, MCAR | Captures local structure, works with various data types | Computationally intensive, sensitive to k choice [37] |

| Random Forest | ML-based | Predicts missing values using ensemble | MAR, complex relationships | Handles non-linearity, provides importance estimates | Computationally demanding [37] |

| MICE | Multiple Imputation | Chained equations with random component | MAR | Accounts for uncertainty, flexible model specification | Computationally intensive, complex implementation [37] |

| missForest | ML-based | Random Forest for multiple imputation | MAR, non-linear relationships | Makes no distributional assumptions, handles various types | Computationally expensive [37] |

| VAE-based | Deep Learning | Neural network with probabilistic latent space | MAR, MNAR, complex patterns | Captures deep patterns, handles uncertainty | Requires large data, complex training [41] |

| Linear Interpolation | Time-series | Uses adjacent points for estimation | Time-series MCAR | Simple, preserves trends | Only for time-series, poor for large gaps [40] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Class Imbalance Handling

Purpose: Systematically address class imbalance in biological classification tasks [35] [38].

Materials:

- Python with scikit-learn and imbalanced-learn packages

- Dataset with documented class imbalance

- Computational resources appropriate for dataset size

Procedure:

Data Preparation:

- Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets

- Apply preprocessing (scaling, encoding) after splitting to avoid data leakage

- Document initial class distribution and imbalance ratio [42]

Baseline Establishment:

- Train model (e.g., Random Forest) on original imbalanced data

- Evaluate using F1-score, geometric mean, and ROC-AUC

- This serves as performance baseline [39]

Resampling Implementation:

- Apply Random Oversampling and Undersampling

- Implement SMOTE with default parameters (k_neighbors=5)

- Test Borderline-SMOTE for boundary emphasis

- Execute NearMiss (versions 1, 2, and 3) for intelligent undersampling [36]

Model Training & Evaluation:

- Train identical model architectures on each resampled dataset

- Validate on the untouched validation set

- Compare performance metrics across all methods

- Select top 2-3 methods for hyperparameter tuning [38]

Final Assessment:

- Evaluate best performing model on held-out test set

- Analyze feature importance changes post-resampling

- Document any shifts in decision boundaries or error patterns

Expected Outcomes: Identification of optimal resampling strategy for your specific biological dataset, with demonstrated improvement in minority class recognition without significant majority class performance degradation.

Protocol 2: Rigorous Missing Data Imputation Evaluation

Purpose: Systematically evaluate and select optimal missing data imputation methods for biological datasets [37] [40].

Materials:

- R or Python with appropriate packages (NAsImpute, scikit-learn, mice)

- Dataset with characterized missingness patterns

- Computational resources for multiple imputation runs

Procedure:

Missing Data Characterization:

- Quantify missingness percentage per variable

- Visualize missingness patterns using heatmaps

- Perform statistical tests to identify missingness mechanism (MCAR, MAR, MNAR) [37]

Experimental Setup:

- For datasets with no natural missingness, introduce missingness following different mechanisms

- Use 5-30% missingness levels to simulate realistic scenarios

- Preserve complete dataset as ground truth for evaluation [40]

Method Implementation:

- Apply simple methods (mean, median, mode imputation)

- Implement kNN imputation with multiple k values (3, 5, 10)

- Execute Random Forest imputation (missForest)

- Run MICE with appropriate regression models

- Test deep learning methods (VAE, GAIN) if data size permits [41]

Comprehensive Evaluation:

Bias and Fairness Assessment:

- Evaluate imputation performance across demographic subgroups

- Quantify bias introduced by different methods

- Check for fairness preservation in downstream predictions [40]

Expected Outcomes: Identification of optimal imputation method for your specific data type and missingness pattern, with comprehensive understanding of trade-offs between different approaches.

Workflow Diagrams

Class Imbalance Resolution Workflow

Missing Data Imputation Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Computational Tools for Data Balancing

| Tool/Package | Application | Key Features | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| imbalanced-learn | Resampling techniques | Comprehensive suite of oversampling and undersampling methods | Python: from imblearn.over_sampling import SMOTE [36] |

| scikit-learn | Model building and evaluation | Class weight adjustment, performance metrics | Python: class_weight='balanced' parameter [43] |

| NAsImpute R Package | Missing data imputation | Multiple imputation methods with evaluation framework | R: devtools::install_github("OmegaPetrazzini/NAsImpute") [37] |

| MICE | Multiple imputation | Chained equations for flexible imputation models | R: mice::mice(data, m=5) [37] |

| missForest | Random Forest imputation | Non-parametric imputation for mixed data types | R: missForest::missForest(data) [37] |

| Autoencoder frameworks | Deep learning imputation | Handles complex patterns in high-dimensional data | Python: TensorFlow/PyTorch implementations [41] |

| Data versioning tools | Preprocessing reproducibility | Tracks data transformations and preprocessing steps | lakeFS for version-controlled data pipelines [42] |

Incorporating fairness-aware training is an ethical and technical imperative in biological machine learning (ML). Without it, models can perpetuate or even amplify existing health disparities, leading to inequitable outcomes in drug development and healthcare [5] [44]. Bias can originate from data, algorithm design, or deployment practices, making its mitigation a focus throughout the ML lifecycle [45] [9]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting support for researchers implementing fairness strategies during model development.

➤ Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most critical fairness metrics to report for a biological ML model? There is no single metric; a combination should be used to evaluate different aspects of fairness. The table below summarizes key group fairness metrics. Note that some are inherently incompatible, so the choice must be guided by the specific clinical and ethical context of your application [45] [9].

Table 1: Key Group Fairness Metrics for Model Evaluation

| Metric | Mathematical Definition | Interpretation | When to Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Parity | P(Ŷ=1|A=0) = P(Ŷ=1|A=1) | Positive outcomes are independent of the sensitive attribute. | When the outcome should be proportionally distributed across groups. |

| Equalized Odds | P(Ŷ=1|A=0, Y=y) = P(Ŷ=1|A=1, Y=y) for y∈{0,1} | Model has equal true positive and false positive rates across groups. | When both types of classification errors (FP and FN) are equally important. |

| Equal Opportunity | P(Ŷ=1|A=0, Y=1) = P(Ŷ=1|A=1, Y=1) | Model has equal true positive rates across groups. | When achieving positive outcomes for the privileged group is the primary concern. |

| Predictive Parity | P(Y=1|A=0, Ŷ=1) = P(Y=1|A=1, Ŷ=1) | Positive predictive value is equal across groups. | When the confidence in a positive prediction must be equal for all groups. |

2. Why does my model's performance remain biased even after applying a mitigation technique? This is a common challenge with several potential causes:

- Insufficient Data Representation: The mitigation technique cannot compensate for a fundamental lack of data from minority groups. The model may not have enough examples to learn robust patterns [45].

- Incompatible Fairness Constraint: The fairness metric you are optimizing for might be misaligned with the source of bias in your data or the model's intended use case [45].

- Proxies for Sensitive Attributes: Even if you remove a sensitive attribute like race or gender, the model may infer it from correlated features (e.g., postal code, prescribed medications), perpetuating bias [7] [9].

- Evaluation Bias: You might be evaluating fairness on a benchmark or test set that is not representative of the true deployment population [45].

3. How do I choose between pre-processing, in-processing, and post-processing mitigation methods? The choice depends on your level of data access, control over the model training process, and regulatory considerations.

Table 2: Comparison of Bias Mitigation Approaches

| Approach | Description | Key Techniques | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-processing | Modifying the training data before model training to remove underlying biases. | Reweighting, Resampling, Synthetic data generation (e.g., SMOTE), Disparate impact remover [44]. | Model-agnostic; creates a fairer dataset. | May distort real-world data relationships; can reduce overall data utility. |

| In-processing | Incorporating fairness constraints directly into the model's learning algorithm. | Regularization (e.g., Prejudice Remover), Adversarial debiasing, Constraint optimization [44]. | Often achieves a better fairness-accuracy trade-off. | Requires modifying the training procedure; can be computationally complex. |

| Post-processing | Adjusting model outputs (e.g., prediction thresholds) after training. | Calibrating thresholds for different subgroups to equalize metrics like FPR or TPR [44]. | Simple to implement; doesn't require retraining. | Requires group membership at inference; may violate model calibration. |

4. What are the regulatory expectations for fairness in AI for drug development? Regulatory landscapes are evolving. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has a structured, risk-based approach, requiring clear documentation, representativeness assessments, and strategies to address bias, particularly for high-impact applications like clinical trials [46]. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has historically taken a more flexible, case-by-case approach, though this creates some regulatory uncertainty [46]. A core principle, especially under the EU AI Act, is that high-risk systems must be "sufficiently transparent," pushing the need for explainable AI (xAI) to enable bias auditing [7].

➤ Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: After implementing an in-processing fairness constraint (e.g., adversarial debiasing), your model's overall accuracy or AUC has significantly decreased, making it unfit for use.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Benchmark Performance: First, establish the performance of a baseline model with no fairness constraints on your overall test set.

- Isolate the Constraint: Re-train your model with the fairness constraint, but gradually increase the weight of the fairness penalty term. Observe the curve of overall performance versus fairness metric.

- Check for Group-Level Trade-offs: Analyze performance metrics (e.g., AUC, F1) for the majority and minority groups separately. A small overall drop might mask a significant performance improvement for the minority group, which is the intended outcome.

Solutions:

- Weaken the Constraint: If the performance drop is too steep, reduce the strength of the fairness regularization term. The goal is to find an acceptable trade-off, not necessarily perfect fairness [44].

- Try a Different Technique: Switch from an in-processing to a pre-processing method. Techniques like reweighting can sometimes improve fairness with a less severe impact on overall performance [44].

- Feature Review: Investigate if the model is overly reliant on features that are proxies for the sensitive attribute. Removing or decorrelating these features before applying the constraint can help [9].

Issue 2: Model Fails Generalization to External or Real-World Datasets

Problem: Your model appears fair and accurate on your internal validation split but exhibits significant performance disparities and bias when deployed on a new, external dataset.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Data Drift Analysis: Check for covariate shift by comparing the distributions of key input features between your training data and the new external dataset.

- Temporal Bias Check: Determine if your training data is from an earlier time period than the external data. Clinical practices, disease definitions, and data collection methods can change over time, leading to "temporal bias" or "concept shift" [45] [9].

- Representativeness Audit: Verify that the external dataset contains sufficient representation from all relevant subgroups. Underrepresented groups in the training data will likely lead to poor generalization for those groups [5] [7].

Solutions:

- Inclusive Data Collection: The most robust solution is to build more diverse and representative training datasets from the outset [5] [9].

- Domain Adaptation: Employ transfer learning or domain adaptation techniques to fine-tune your pre-trained model on a small, representative sample from the new target domain.

- Synthetic Data Augmentation: Use techniques like SMOTE or more advanced generative models to create synthetic samples for underrepresented subgroups in your training data, improving its coverage and diversity [44].

Issue 3: Inability to Interpret or Explain the Fair Model's Predictions

Problem: You have successfully created a model that meets fairness criteria, but it is a "black box" (e.g., a complex deep neural network), and you cannot explain its reasoning to stakeholders or regulators.

Diagnosis Steps: