Establishing Computational Model Credibility: Standards, Applications, and Best Practices for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the standards and practices for establishing credibility in computational models, with a specific focus on applications in drug development and medical device innovation.

Establishing Computational Model Credibility: Standards, Applications, and Best Practices for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to the standards and practices for establishing credibility in computational models, with a specific focus on applications in drug development and medical device innovation. It explores the foundational principles of risk-based credibility frameworks like ASME V&V 40 and FDA guidance, detailing methodological steps for verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification. The content further addresses common implementation challenges—including data quality, model bias, and talent shortages—and offers troubleshooting strategies. Finally, it examines comparative validation approaches and the evolving role of in silico trials, equipping researchers and professionals with the knowledge to build trustworthy models for regulatory submission and high-impact decision-making.

The Bedrock of Trust: Core Principles and Regulatory Frameworks for Model Credibility

In the development of drugs and medical devices, computational modeling and simulation (CM&S) have become critical tools for evaluating safety and effectiveness. The credibility of these models is paramount, especially when they are used to inform high-stakes regulatory decisions. Model credibility is broadly defined as the trust, established through the collection of evidence, in the predictive capability of a computational model for a specific context of use [1] [2]. Establishing this trust requires a systematic, evidence-based approach.

Two primary frameworks have emerged to guide this process: the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance document, "Assessing the Credibility of Computational Modeling and Simulation in Medical Device Submissions," and the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) V&V 40 standard, "Assessing Credibility of Computational Modeling through Verification and Validation: Application to Medical Devices" [3] [4]. The FDA guidance provides a risk-informed framework for regulatory submissions, while the ASME V&V 40 standard offers a detailed engineering methodology. This guide objectively compares these frameworks, detailing their applications and the experimental protocols required to demonstrate model credibility.

Comparative Analysis of Credibility Frameworks

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of the FDA and ASME frameworks, highlighting their shared principles and distinct focuses.

Table 1: Core Framework Comparison: FDA Guidance vs. ASME V&V 40 Standard

| Feature | FDA Guidance | ASME V&V 40 Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Regulatory recommendations for medical device submissions [3] [5]. | Engineering standard for establishing model credibility [4] [1]. |

| Scope of Application | Physics-based, mechanistic models for medical devices [3] [5]. | Computational models for medical devices; principles adapted for other areas like drug development [1] [6]. |

| Core Methodology | Risk-informed credibility assessment framework [3]. | Risk-informed credibility assessment framework [1]. |

| Defining Element | Context of Use (COU): A detailed statement defining the specific role and scope of the model [3] [1]. | Context of Use (COU): A detailed statement defining the specific role and scope of the model [1]. |

| Risk Assessment Basis | Combination of Model Influence (on decision) and Decision Consequence (of an error) [1]. | Combination of Model Influence (on decision) and Decision Consequence (of an error) [1] [6]. |

| Key Output | Guidance on evidence needed for a credible regulatory submission [3]. | Goals for specific Credibility Factors (e.g., code verification, validation) [1]. |

| Regulatory Status | Final guidance for industry and FDA staff (November 2023) [3]. | Consensus standard; recognized and utilized by the FDA [1]. |

The FDA guidance and ASME V&V 40 standard are highly aligned, with the ASME standard providing the foundational, technical methodology that the FDA guidance adapts for the regulatory review process [7] [1]. The core principle shared by both is that the level of evidence required to demonstrate a model's credibility should be commensurate with the model risk [1] [6]. This means that a model supporting a critical decision with significant patient impact requires more rigorous evidence than one used for exploratory purposes.

The Risk-Based Credibility Assessment Workflow

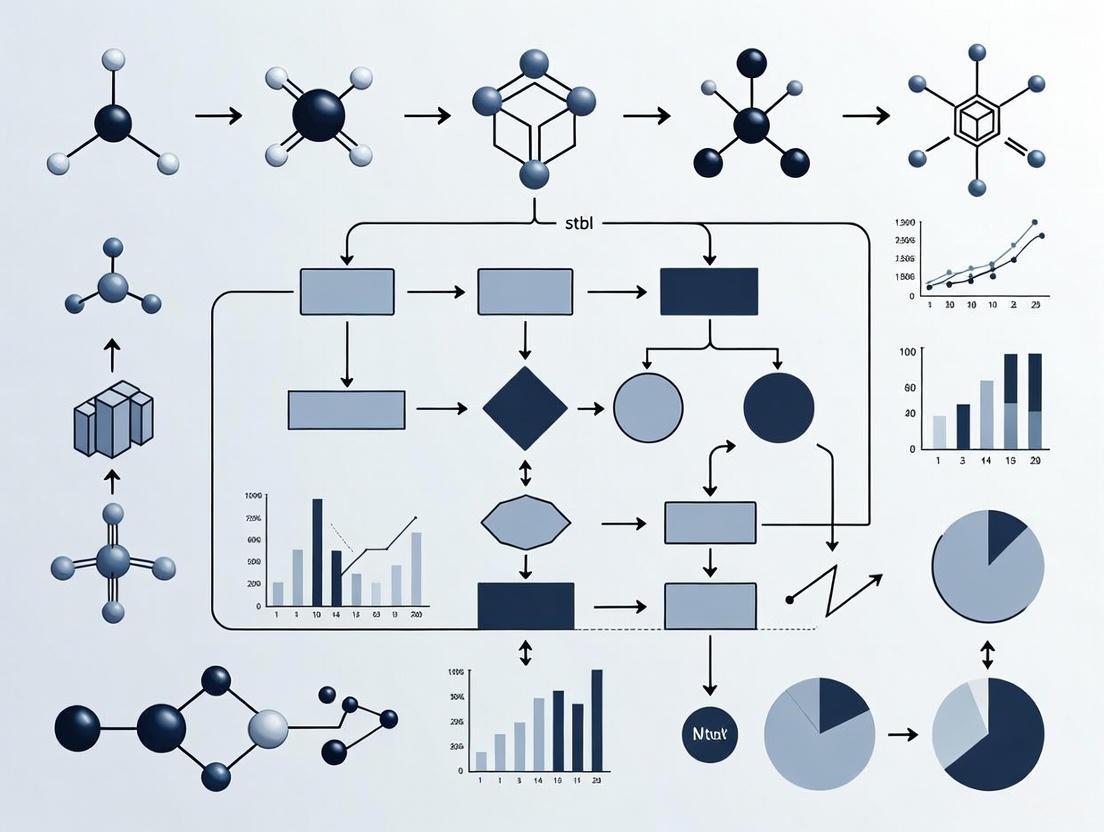

Both frameworks operationalize the risk-based approach through a structured workflow. The diagram below illustrates the key steps, from defining the model's purpose to assessing its overall credibility.

Diagram 1: Credibility Assessment Workflow

Defining Context of Use and Risk Assessment

The process begins by precisely defining the Context of Use (COU), a detailed statement of the specific role and scope of the computational model in addressing a question of interest [1] [6]. For example, a COU could be: "The PBPK model will be used to predict the effect of a moderate CYP3A4 inhibitor on the pharmacokinetics of Drug X in adult patients to inform dosing recommendations" [6].

The COU directly informs the model risk assessment, which is a function of two factors:

- Model Influence: The contribution of the computational model relative to other evidence in making a decision (e.g., supportive vs. primary evidence) [1] [6].

- Decision Consequence: The significance of an adverse outcome resulting from an incorrect decision based on the model [1] [6].

The following table illustrates how different combinations of these factors determine the overall model risk, using examples from medical devices and drug development.

Table 2: Model Risk Assessment Matrix with Application Examples

| Decision Consequence | Low Model Influence | High Model Influence |

|---|---|---|

| Low | Low Risk: Model for internal design selection, with low impact on patient safety. | Moderate Risk: Model used as primary evidence to waive in vitro bioequivalence study for a low-risk drug. |

| High | Moderate Risk: Model supports, but is not primary for, a clinical trial design for a ventricular assist device [1]. | High Risk: Model used as primary evidence to replace a clinical trial for a high-risk implant or to set pediatric dosing [1] [6]. |

Credibility Factors and Validation Activities

The model risk drives the rigor required for specific credibility factors, which are elements of the verification and validation (V&V) process [1]. The following table lists key credibility factors and examples of corresponding validation activities, with data from a centrifugal blood pump case study [1].

Table 3: Credibility Factors and Corresponding Experimental Validation Activities

| Credibility Factor | Experimental Validation Activity | Example from Blood Pump Case Study [1] |

|---|---|---|

| Model Inputs | Characterize and quantify uncertainty in input parameters. | Use validated in vitro tests to define blood viscosity and density for fluid dynamics model. |

| Test Samples | Ensure test articles are representative and well-characterized. | Use a precise, manufactured prototype of the pump for validation testing. |

| Test Conditions | Ensure experimental conditions represent the COU. | Perform experiments at operating conditions (flow rate, pressure) specified in the COU (e.g., 2.5-6 L/min, 2500-3500 RPM). |

| Output Comparison | Compare model outputs to experimental data with a defined metric. | Compare Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD)-predicted hemolysis levels to in vitro hemolysis measurements using a pre-defined acceptance criterion. |

| Applicability | Demonstrate relevance of validation activities to the COU. | Justify that in vitro hemolysis testing is a relevant comparator for predicting in vivo hemolysis. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

This section provides a detailed methodology for key experiments used to generate validation data, as referenced in the credibility factors above.

In Vitro Hemolysis Testing for Blood Pump Validation

Purpose and Principle: This test is designed to quantify the level of red blood cell damage (hemolysis) caused by a blood pump under controlled conditions. It serves as a critical comparator for validating computational fluid dynamics (CFD) models that predict hemolysis [1]. The principle involves circulating blood through the pump under specified operating conditions and measuring the release of hemoglobin.

Protocol Workflow: The experimental sequence for hemolysis validation is methodical, proceeding from system preparation to data analysis.

Diagram 2: In Vitro Hemolysis Testing Protocol

Key Reagents and Materials:

- Fresh Heparinized Blood: Typically bovine or porcine blood; provides the biological substrate for measuring shear-induced damage. The hematocrit should be adjusted to a standardized level (e.g., 30%±2%) [1].

- PBS (Phosphate Buffered Saline): Used for priming the flow loop and diluting blood samples; prevents clotting and cell lysis from osmotic shock prior to testing.

- Centrifuge: Critical for separating plasma from blood cells after sample collection, enabling accurate measurement of plasma-free hemoglobin.

- Spectrophotometer: Instrument used to measure the concentration of free hemoglobin in plasma by detecting absorbance at specific wavelengths (e.g., 540 nm).

Data Analysis: The primary output is the Normalized Index of Hemolysis (NIH), which is calculated based on the increase in plasma-free hemoglobin, the total hemoglobin content in the blood, the test flow rate, and the duration of the test [1]. This normalized value allows for comparison across different test setups and conditions.

PBPK Model Validation for Drug-Drug Interactions

Purpose and Principle: Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models are used in drug development to predict pharmacokinetic changes, such as those caused by drug-drug interactions (DDIs). The credibility of a PBPK model is established by assessing its predictive performance against observed clinical data [6].

Protocol Workflow: The validation of a PBPK model is an iterative process of building, testing, and refining the model structure and parameters.

Diagram 3: PBPK Model Development and Validation Workflow

Key Reagents and Materials:

- In Vitro System Data: Data from experiments like human liver microsome or transfected cell assays to quantify enzyme kinetics (e.g., Km, Vmax) for the drug of interest [6].

- Clinical PK Data: Observed concentration-time data from early-phase clinical trials in humans; used for model calibration and refinement before the final validation step.

- Independent Clinical DDI Study Data: Data from a dedicated drug-drug interaction clinical study not used in model development; serves as the primary comparator for final model validation [6].

- PBPK Software Platform: A qualified and verified software tool (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp, PK-Sim) used to implement the mathematical model and perform simulations.

Data Analysis: Validation involves a quantitative comparison of PBPK model predictions to observed clinical data. Standard pharmacokinetic parameters like Area Under the Curve (AUC) and maximum concentration (Cmax) are compared. Predictive performance is typically assessed by calculating the fold-error of the prediction and checking if it falls within pre-specified acceptance criteria (e.g., within 1.25-fold or 2-fold of the observed data) [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table catalogs key materials and their functions for conducting the experiments essential to model validation.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Credibility Evidence Generation

| Item | Function in Credibility Assessment |

|---|---|

| Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) | An optical experimental method used to measure instantaneous velocity fields in fluids. It serves as a key comparator for validating CFD-predicted flow patterns and shear stresses in medical devices like blood pumps [1]. |

| Human Liver Microsomes | Subcellular fractions containing drug-metabolizing enzymes (e.g., CYPs). Used in in vitro assays to generate kinetic parameters for drug metabolism, which are critical model inputs for PBPK models [6]. |

| Standardized Blood Analog Fluid | A solution with optical and viscous properties matching human blood. Used in in vitro flow testing (e.g., for PIV) to provide a safe, reproducible, and well-characterized fluid that represents key biological properties [1]. |

| Qualified PBPK Software Platform | Commercial or proprietary software used to build and simulate PBPK models. The platform itself must undergo code verification and software quality assurance to ensure it solves the underlying mathematics correctly [6]. |

| Clinical Bioanalytical Assay (LC-MS/MS) | A validated method (e.g., Liquid Chromatography with Tandem Mass Spectrometry) for quantifying drug concentrations in biological samples. It generates the high-quality clinical PK data used as a comparator for PBPK model validation [6]. |

The journey toward establishing model credibility is a structured, evidence-driven process guided by the complementary frameworks of the FDA guidance and the ASME V&V 40 standard. The core takeaway is that credibility is not a one-size-fits-all concept; it is a risk-informed judgment where the required evidence is proportional to the model's impact on decisions related to patient safety and product effectiveness [3] [1]. Success hinges on the precise definition of the Context of Use and the execution of targeted verification and validation activities—ranging from mesh refinement studies to in vitro hemolysis tests and clinical DDI studies—to generate the necessary evidence. As computational models take on more significant roles, including enabling In Silico Clinical Trials, the rigorous and transparent application of these credibility standards will be foundational to gaining the trust of regulators, clinicians, and patients [7].

The Centrality of Context of Use (COU) in Risk-Based Assessment

In computational science, the Context of Use (COU) is a formal statement that defines the specific role, scope, and objectives of a computational model within a decision-making process [1] [8]. This concept is foundational to modern risk-based credibility assessment frameworks, which posit that the evidence required to trust a model's predictions should be commensurate with the risk of an incorrect decision impacting patient safety or public health [1] [8] [9]. As computational models transition from supporting roles to primary evidence in regulatory submissions for medical devices and pharmaceuticals, establishing model credibility through a structured, risk-informed process has become essential [1] [10] [8].

The American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) V&V 40 subcommittee developed a pioneering risk-informed framework that directly links the COU to the required level of model validation [1]. This framework has been adapted across multiple domains, including drug development and systems biology, demonstrating its utility as a standardized approach for establishing model credibility [11] [8]. The core principle is that a model's COU determines its potential influence on decisions and the consequences of those decisions, which collectively define the model risk and corresponding credibility requirements [1].

The Risk-Based Framework: From COU to Credibility

Core Components of the Assessment Framework

The risk-based credibility assessment framework involves a systematic process with clearly defined steps and components. The table below outlines the key terminology essential for understanding this approach.

Table 1: Core Terminology in Risk-Based Credibility Assessment

| Term | Definition | Role in Credibility Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Context of Use (COU) | A detailed statement defining the specific role and scope of a computational model in addressing a question of interest [1] [8]. | Serves as the foundational document that frames all subsequent credibility activities. |

| Model Influence | The degree to which the computational model output influences a decision, ranging from informative to decisive [1]. | One of two factors determining model risk. |

| Decision Consequence | The potential severity of harm resulting from an incorrect decision made based on the model [1] [9]. | One of two factors determining model risk. |

| Model Risk | The possibility that using a computational model leads to a decision resulting in patient harm. It is the combination of model influence and decision consequence [1]. | Directly drives the level of evidence (credibility goals) required. |

| Credibility Factors | Elements of the verification and validation (V&V) process, such as conceptual model validation or operational validation [1]. | The specific V&V activities for which evidence-based goals are set. |

| Credibility Goals | The target level of evidence needed for each credibility factor to establish sufficient trust in the model for the given COU [1]. | The final output of the risk analysis, defining the evidentiary bar. |

The Sequential Assessment Workflow

The following diagram visualizes the standard workflow for applying the risk-based credibility framework, from defining the COU to the final credibility assessment.

Comparative Analysis: COU-Driven Credibility Requirements

Case Study: Computational Fluid Dynamics in a Blood Pump

The ASME V&V 40 standard illustrates the profound impact of COU using a hypothetical computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model of a generic centrifugal blood pump [1]. The model predicts flow-induced hemolysis (red blood cell damage), but the required level of validation changes dramatically based on the pump's clinical application.

Table 2: Impact of COU on Credibility Requirements for a Centrifugal Blood Pump Model [1]

| Context of Use (COU) Element | COU Scenario 1:\nCardiopulmonary Bypass (CPB) | COU Scenario 2:\nVentricular Assist Device (VAD) |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Application | Short-term cardiopulmonary bypass surgery (hours) | Long-term ventricular assist device (years) |

| Device Classification | Class II | Class III |

| Model Influence | Informs safety assessment, but not the sole evidence | Primary evidence for hemolysis safety assessment |

| Decision Consequence | Low; temporary injury if hemolysis occurs | High; potential for severe permanent injury or death |

| Resulting Model Risk | Low | High |

| Credibility Goal for Validation | Low: Comparison with a single in-vitro hemolysis dataset may be sufficient. | High: Requires rigorous validation against multiple, high-quality experimental datasets under various operating conditions. |

This comparison demonstrates that the same computational model requires substantially different levels of validation evidence based solely on changes to its COU. For the high-risk VAD application, the consequence of an incorrect model prediction is severe, justifying the greater investment in comprehensive validation [1].

Cross-Domain Application of the Framework

The risk-informed principle pioneered by ASME V&V 40 has been successfully adapted to other fields, including drug development and systems biology.

Table 3: Application of Risk-Informed Credibility Assessment Across Domains

| Domain | Framework/Initiative | Role of COU | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medical Devices | ASME V&V 40 [1] | Central driver of model risk and credibility goals. | CFD models for blood pump hemolysis, fatigue analysis of implants. |

| Drug Development | Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) [12] [8] | Defines the "fit-for-purpose" application of quantitative models. | Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models for dose selection, trial design. |

| Systems Biology | Adapted credibility standards [11] | Informs the level of reproducibility and annotation required for a model to be trusted. | Mechanistic subcellular models used for drug target identification. |

| AI/ML Medical Devices | Alignment with MDR/ISO 14971 [9] | Determines the clinical impact of model errors (e.g., false negatives vs. false positives). | Image-based diagnosis classifiers (e.g., for cancer detection). |

In drug development, the "fit-for-purpose" paradigm mirrors the risk-based approach, where the selection and evaluation of Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) tools are closely aligned with the COU and the model's impact on development decisions [12]. For AI/ML-based medical devices, the COU is critical for understanding the clinical impact of different types of model errors, necessitating performance metrics that incorporate risk rather than relying solely on standard accuracy rates [9].

Experimental Protocols for Establishing Credibility

The credibility of a computational model is established through rigorous Verification and Validation (V&V) activities. The specific protocols are tailored to meet the credibility goals set by the risk analysis.

Protocol for a High-Risk CFD Model (e.g., VAD Blood Pump)

For a high-risk model, such as the CFD model for a Ventricular Assist Device, a comprehensive V&V protocol is required.

1. Verification

- Code Verification: Ensure the computational solver (e.g., ANSYS CFX) correctly implements the underlying mathematical equations. This involves solving problems with known analytical solutions [1].

- Calculation Verification: Estimate the numerical accuracy of the specific simulation (e.g., for a blood pump). This includes performing a mesh refinement study to ensure results are independent of the discretization of the geometry [1].

2. Validation

- Objective: Demonstrate that the model accurately represents the real-world physics. This is done by comparing model predictions with experimental data.

- Experimental Comparator: In-vitro hemolysis testing using a blood analog fluid in a mock circulatory loop [1].

- Key Metrics: The Modified Index of Hemolysis (MIH) is calculated from experimental measurements and compared to the hemolysis index predicted by the CFD model.

- Acceptance Criterion: The model's prediction of the MIH must fall within a pre-defined agreement margin (e.g., ±20%) of the experimental measurements across the pump's operating range. The strictness of this margin is dictated by the model risk [1].

The workflow for this protocol is detailed below.

Protocol for a Low-Risk or Informational Model

For a model with low influence and consequence, the V&V process may be substantially reduced. The focus may be on conceptual model validation, where the underlying assumptions and model structure are reviewed by subject matter experts, with limited or no quantitative validation against physical data required [1].

The following table details key resources and methodologies that support the development and credibility assessment of computational models across different domains.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Computational Modeling

| Tool/Resource | Function/Purpose | Relevance to Credibility |

|---|---|---|

| ASME V&V 40 Standard | Provides the authoritative framework for conducting risk-informed credibility assessment [1]. | The foundational methodology for linking COU and risk to V&V requirements. |

| Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) | A standardized XML-based format for representing computational models in systems biology [11]. | Ensures model reproducibility and interoperability, a prerequisite for credibility. |

| MIRIAM Guidelines | Define minimum information for annotating biochemical models, ensuring proper metadata [11]. | Supports model reusability and understanding, key factors in long-term credibility. |

| PBPK/PD Modeling Software (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp) | Tools for developing mechanistic Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic models [12]. | Used in MIDD to generate evidence for regulatory submissions; credibility is assessed via a fit-for-purpose lens. |

| In-vitro Hemolysis Test Loop | A mock circulatory loop for measuring hemolysis in blood pumps under controlled conditions [1]. | Serves as the source of experimental comparator data for validating high-risk CFD models. |

| ISO 14971 Standard | The international standard for risk management of medical devices [9]. | Provides the overall risk management process into which the risk-based evaluation of an AI/ML model is integrated. |

The Context of Use is the central pillar of a modern, risk-based approach to computational model credibility. It is the critical starting point that determines the model's risk profile and, consequently, the requisite level of evidence from verification and validation activities. As demonstrated across medical devices, drug development, and AI/ML, a disciplined application of this COU-driven framework ensures that models are fit-for-purpose, resources are allocated efficiently, and regulatory decisions are based on a justified level of trust. This structured approach is essential for harnessing the full potential of computational modeling to advance public health while safeguarding patient safety.

Understanding the ASME V&V 40 Risk-Informed Credibility Framework

In the development of pharmaceuticals and medical devices, computational modeling and simulation (CM&S) has become a critical tool for accelerating design, informing decisions, and supporting regulatory submissions. The credibility of these models—the trust in their predictive capability for a specific context—is paramount, particularly when they influence high-stakes regulatory and patient-care decisions [6] [5]. Several standards have been developed to guide the credibility assessment process. The ASME V&V 40 framework, specifically tailored for medical devices, provides a risk-informed approach for determining the necessary level of model confidence [1] [4]. Other influential standards include those from NASA, which focus on broad engineering and physical science models, and various systems biology standards (like SBML and MIRIAM) that ensure the reproducibility and unambiguous annotation of biological models [2]. This guide objectively compares the ASME V&V 40 standard with these alternative approaches, detailing their applications, experimental protocols, and the evidence required to establish model credibility.

Comparative Analysis of Credibility Frameworks

The following table summarizes the core objectives, primary application domains, and key characteristics of three major approaches to computational model credibility.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Computational Model Credibility Frameworks

| Framework Characteristic | ASME V&V 40 (2018) | NASA Standards | Systems Biology Standards |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Scope & Objective | Risk-based credibility for medical device CM&S [1] | Quality assurance for computational models in engineering & physical science [2] | Reproducibility & reusability of biological models [2] |

| Core Application Domain | Physics-based/mechanistic medical device models [3] [5] | Aerospace, mechanical engineering [2] | Mechanistic, subcellular biological systems [2] |

| Governance & Recognition | FDA-recognized standard; developed by ASME [13] [3] | Developed by NASA for internal and partner use [2] | Community-driven (e.g., SBML, CellML, MIRIAM) [2] |

| Defining Principle | Credibility effort is commensurate with model risk [1] | Rigorous, generalized quality assurance for simulation [2] | Standardized model encoding, annotation, and dissemination [2] |

| Key Artifacts/Outputs | Credibility Assessment Plan & Report; VVUQ evidence [1] | Model quality assurance documentation [2] | Annotated model files (SBML, CellML); simulation results [2] |

Core Methodology of the ASME V&V 40 Framework

The ASME V&V 40 framework introduces a structured, risk-informed process to establish the level of evidence needed for a model to be deemed credible for its specific purpose. The workflow is not a one-size-fits-all prescription but a logical sequence for planning and executing a credibility assessment.

Figure 1: The ASME V&V 40 Credibility Assessment Workflow

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Applying the Framework

The following steps outline the protocol for executing a V&V 40-compliant credibility assessment, as demonstrated in applications ranging from heart valve analysis to centrifugal blood pumps [13] [1].

- Define the Question of Interest: Articulate the specific question, decision, or concern the study aims to address. This question may be broader than the model's immediate use.

- Define the Context of Use (COU): Create a detailed statement specifying the role, scope, and applicable boundaries of the computational model in addressing the question. This includes defining the quantities of interest the model will predict [6] [1].

- Assess Model Risk: Model risk is a combination of:

- Decision Consequence: The significance of an adverse outcome from an incorrect decision. This is often tied to patient impact [1].

- Model Influence: The contribution of the computational model relative to other evidence in the decision-making process [6] [1]. This risk assessment directly dictates the rigor of subsequent V&V activities.

- Establish Credibility Goals: For each of the 13 credibility factors (e.g., code verification, model input accuracy, output comparison), define specific, measurable goals. The stringency of these goals is determined by the model risk [1].

- Gather V&V Evidence: Execute the planned verification, validation, and uncertainty quantification activities. This involves using comparator data (e.g., from benchtop or clinical studies) to validate the model's outputs [13] [6].

- Assess Overall Credibility: A team of experts reviews the collected evidence against the pre-defined credibility goals to determine if the model is sufficiently credible for the stated COU [1].

- Document and Report: The entire process, rationale, and results are documented to provide a transparent record for internal review or regulatory submission [3].

Quantitative Comparisons and Case Study Data

The flexibility of the V&V 40 framework is best illustrated through concrete examples. The following table compares two hypothetical Contexts of Use for a computational fluid dynamics (CFD) model of a centrifugal blood pump, demonstrating how risk drives credibility requirements [1].

Table 2: Case Study Comparison: Credibility Requirements for a Centrifugal Blood Pump Model

| Credibility Factor | Context of Use 1:\nCPB Pump (Low Risk) | Context of Use 2:\nVAD Pump (High Risk) | Supporting Experimental Data & Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Influence | Complementary evidence (Medium) | Primary evidence (High) | For the VAD COU, the model is a primary source of "clinical" information on hemolysis [1]. |

| Decision Consequence | Low impact on patient risk | High impact on patient risk | VAD use is life-sustaining; hemolysis directly impacts patient safety [1]. |

| Output Comparison | Qualitative comparison of flow fields | Quantitative comparison with strict acceptance criteria | For the VAD COU, a quantitative validation metric (e.g., using in vitro hemolysis test data) with tight tolerances is required [1]. |

| Test Samples | Single operating point tested | Multiple operating points across the design space | The high-risk VAD COU requires validation over the entire intended operating range (e.g., 2.5-6 LPM, 2500-3500 RPM) [1]. |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Not required | Required for key output quantities | The prediction of hemolysis for the VAD must include uncertainty bounds to inform safety margins [1]. |

Another case study involving a finite element analysis (FEA) model of a transcatheter aortic valve (TAV) for design verification highlights the framework's application in regulatory contexts. The model was used for structural component stress/strain analysis per ISO5840-1:2021, and its credibility was established specifically for that COU [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successfully implementing the V&V 40 framework requires a suite of tools and materials for model development, testing, and validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for V&V 40 Compliance

| Tool/Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Credibility Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Commercial Simulation Software | ANSYS CFX, ANSYS Mechanical [13] [1] | Provides the core computational physics solver for the model. Its built-in verification tools and quality assurance are foundational. |

| Experimental Test Rigs | In vitro hemolysis test loops [1]; Particle Image Velocimetry (PIV) systems [1] | Generate high-quality comparator data for model validation under controlled conditions that mimic the COU. |

| CAD & Meshing Tools | SolidWorks [1]; ANSYS Meshing [1] | Used to create the digital geometry and finite volume/finite element representation of the medical device. |

| Standardized Material Properties | Medical-grade PEEK for device testing [13]; Newtonian blood analog fluids [1] | Provide consistent, well-defined model inputs and ensure test conditions are representative of real-world use. |

| Code Verification Suites | Method of Manufactured Solutions (MMS) benchmarks; grid convergence study tools [7] | Used to verify that the numerical algorithms in the software are solving the mathematical equations correctly. |

| Data Analysis & Statistical Packages | Custom scripts for validation metrics; uncertainty quantification libraries | Enable quantitative output comparison and the calculation of uncertainty intervals for model predictions. |

The ASME V&V 40 standard provides a uniquely flexible and powerful framework for establishing confidence in computational models used for medical devices. Its core differentiator is the risk-informed principle, which ensures that the rigor and cost of credibility activities are proportionate to the model's impact on patient safety and regulatory decisions [1]. While standards from NASA offer robust methodologies for general engineering applications, and systems biology standards solve critical challenges in model reproducibility, V&V 40 is specifically designed and recognized for the medical device regulatory landscape [3] [2]. As the field evolves with emerging applications like In Silico Clinical Trials (ISCT), the principles of V&V 40 continue to be extended and refined, underscoring its role as a foundational element in the credible practice of computational modeling for healthcare [7].

Computational models are increasingly critical for high-impact decision-making across scientific, engineering, and medical domains. Within regulatory science, agencies including the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) have established frameworks to ensure the credibility of these computational approaches. These standards are particularly relevant for pharmaceutical development and public health protection, where model predictions can influence therapeutic approval and patient safety. This guide provides a systematic comparison of credibility standards across these three organizations, contextualized within broader research on computational model validation. It is designed to assist researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in navigating multi-jurisdictional regulatory requirements for in silico evidence submission. The comparative analysis focuses on organizational structures, specific credibility assessment criteria, and practical implementation pathways, supported by standardized experimental data presentation and visualization.

Organizational Structures and Regulatory Authority

The regulatory frameworks governing computational model credibility are fundamentally shaped by the distinct organizational structures and mandates of the FDA, EMA, and NASA.

FDA (U.S. Food and Drug Administration): The FDA operates as a centralized federal authority within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Its Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) possesses direct decision-making power to approve, reject, or request additional information for new drug applications. This centralized model enables relatively swift decision-making, as review teams consist of FDA employees who facilitate consistent internal communication. Upon FDA approval, a drug is immediately authorized for marketing throughout the entire United States, providing instantaneous nationwide market access [14].

EMA (European Medicines Agency): In contrast, the EMA functions primarily as a coordinating network across European Union Member States rather than a single decision-making body. Based in Amsterdam, it coordinates the scientific evaluation of medicines through its Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP), which leverages experts from national competent authorities. Rapporteurs from these national agencies lead the assessment, and the CHMP issues scientific opinions. The final legal authority to grant marketing authorization, however, rests with the European Commission. This network model incorporates diverse scientific perspectives from across Europe but requires more complex coordination among multiple national agencies, potentially reflecting varied healthcare systems and medical traditions [14].

NASA (National Aeronautics and Space Administration): As a U.S. federal agency, NASA's credibility standards for computational modeling were developed to ensure reliability in high-stakes aerospace applications, including missions that are prohibitively expensive or require unique environments like microgravity. These standards have subsequently influenced regulatory science in other fields, including medicine. NASA's approach is characterized by a rigorous, evidence-based framework for establishing trust in computational models, which has served as a reference for other organizations developing their own credibility assessments [2].

Table 1: Overview of Regulatory Structures and Model Evaluation Contexts

| Organization | Organizational Structure | Primary Context for Model Evaluation | Geographical Scope |

|---|---|---|---|

| FDA | Centralized Federal Authority | Drug/Biologic Safety, Efficacy, and Quality | United States |

| EMA | Coordinating Network of National Agencies | Medicine Safety, Efficacy, and Quality | European Union |

| NASA | Centralized Federal Agency | Aerospace Engineering and Science | Primarily U.S., with international partnerships |

Comparative Analysis of Credibility Standards

While all three organizations share the common goal of ensuring model reliability, their specific approaches to credibility assessment differ in focus, application, and procedural details.

FDA Credibility Standards for Computational Modeling

The FDA defines model credibility as “the trust, established through the collection of evidence, in the predictive capability of a computational model for a context of use (COU)” [2]. The FDA's approach is adaptable, with credibility evidence requirements scaling proportionally with the model's impact on regulatory decisions. For models supporting key safety or efficacy conclusions, the FDA expects comprehensive verification and validation (V&V). Key components of the FDA's framework include:

- Context of Use Definition: A precise specification of the model's purpose and the specific regulatory question it addresses.

- Model Verification: Ensuring the computational model is implemented correctly and operates as intended.

- Model Validation: Assessing the model's accuracy in representing real-world biological or clinical systems, often through comparison with experimental or clinical data.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Characterizing the uncertainty in model inputs, parameters, and outputs to understand their impact on predictions.

The FDA has begun accepting modeling and simulation as forms of evidence for pharmaceutical and medical device approval, particularly when such models are adequately validated and their limitations are understood [2].

EMA Requirements for Model Credibility

The EMA's approach to computational model assessment is integrated within its broader regulatory evaluation process for medicines. Like the FDA, the EMA acknowledges the growing role of modeling and simulation in product development and regulatory submission. A cornerstone of the EMA's framework is the Risk Management Plan (RMP), required for all new marketing authorization applications. The RMP is a dynamic document that includes detailed safety specifications and pharmacovigilance activities, which can encompass the use of predictive models [15] [14]. While the EMA does not have a separate, publicly detailed credibility standard akin to NASA's, its scientific committees evaluate the credibility of submitted models based on principles of scientific rigor, transparency, and relevance to the clinical context. The assessment often emphasizes the clinical meaningfulness of model-based findings beyond mere statistical significance [14].

NASA Credibility Standards and Their Influence

NASA has developed a well-structured and influential framework for credibility assessment, formalized in a set of "Ten Rules" and a corresponding rubric for evaluating conformance [16]. This framework was born from the need to rely on computational models for complex, high-consequence aerospace experiments and engineering tasks. The standard is designed to be qualitative and adaptable to a wide range of models, from engineering simulations to potential biomedical applications. The core principles emphasize:

- Comprehensive Documentation: Ensuring all aspects of model development, assumptions, and implementation are thoroughly documented.

- Robust Verification and Validation: Demonstrating that the model is solved correctly (verification) and that it accurately represents the real-world system (validation).

- Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis: Quantifying uncertainties and determining how they affect model outcomes.

- Model Reproducibility: Enabling independent researchers to recreate the model and obtain consistent results, a significant challenge in computational science [2].

This NASA framework provides a foundational structure that has informed credibility discussions in other regulatory and scientific communities, including biomedical research [16] [2].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Credibility Framework Components

| Component | FDA | EMA | NASA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Guidance | Context of Use-driven Evidence Collection | Integrated within RMP and Scientific Advice | "Ten Rules" Rubric |

| Core Principle | Evidence-based trust in predictive capability | Scientific rigor and clinical relevance | Comprehensive verification and validation |

| Key Document | Submission-specific evidence package | Risk Management Plan (RMP) | Conformance rubric and documentation |

| Uncertainty Handling | Uncertainty Quantification | Implicit in benefit-risk assessment | Explicit Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis |

| Applicability | Pharmaceutical & Medical Device Submissions | Pharmaceutical Submissions | Aerospace, Engineering, with cross-disciplinary influence |

Experimental Protocols for Credibility Assessment

Implementing a robust credibility assessment requires a systematic, multi-stage experimental workflow. The following protocol, aligned with regulatory expectations, outlines the key methodologies for establishing model credibility.

Figure 1: A generalized workflow for assessing computational model credibility, illustrating the sequence from context definition to final evidence assembly for regulatory review.

Protocol 1: Context of Use (COU) Definition

Objective: To establish a clear and unambiguous statement of the computational model's purpose, the specific regulatory question it will inform, and the boundaries of its application. This is the critical first step that determines the scope and extent of all subsequent credibility evidence [2].

Methodology:

- Problem Scoping: Formally define the clinical or biological problem the model addresses. For a drug development context, this could be predicting tumor growth inhibition or characterizing a pharmacokinetic profile.

- Model Interface Specification: Detail the model's inputs (e.g., drug dose, patient biomarkers) and outputs (e.g., survival probability, biomarker change).

- Acceptable Risk Thresholds: In consultation with regulatory guidelines, define the level of uncertainty that is acceptable for the intended decision. A model supporting a primary efficacy endpoint requires a higher evidence standard than one used for exploratory research.

Protocol 2: Model Verification and Validation (V&V)

Objective: To ensure the computational model is implemented correctly (Verification) and that it accurately represents the real-world system of interest (Validation).

Methodology:

- Verification:

- Code Verification: Use techniques like unit testing, consistency checks, and convergence analysis to ensure the software is free of coding errors and the numerical solutions are accurate.

- Model Verification: Confirm that the conceptual model has been correctly translated into computer code, often by comparing outputs to known analytical solutions or results from independent implementations.

- Validation:

- Experimental Design: Identify and procure independent datasets not used in model calibration. These can come from clinical trials, published literature, or experimental studies.

- Goodness-of-fit Testing: Quantitatively compare model predictions against the validation data using appropriate statistical measures (e.g., Mean Squared Error, R-squared, Bayesian metrics).

- Face Validation: Engage domain experts (e.g., clinicians, biologists) to qualitatively assess whether the model behavior and outputs are biologically or clinically plausible.

Protocol 3: Uncertainty and Sensitivity Analysis

Objective: To quantify the uncertainty in model predictions and identify which model inputs and parameters contribute most to this uncertainty.

Methodology:

- Uncertainty Quantification (UQ):

- Characterize uncertainty in model input parameters (e.g., as probability distributions derived from data).

- Propagate these uncertainties through the model using techniques like Monte Carlo sampling to generate a distribution of possible outputs, resulting in prediction intervals (e.g., 95% confidence intervals) rather than single point estimates.

- Sensitivity Analysis (SA):

- Perform global sensitivity analysis (e.g., using Sobol' indices or Morris method) to rank the influence of model inputs and parameters on the output variance.

- This identifies critical parameters that require more precise estimation and simplifies models by fixing non-influential parameters.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successfully executing credibility assessments requires leveraging a suite of standardized tools, resources, and data formats. The table below details key "research reagents" for computational modeling in a regulatory context.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Credibility Assessment

| Item Name | Type/Category | Primary Function in Credibility Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) | Model Encoding Standard | Provides a standardized, machine-readable format for exchanging and reproducing computational models of biological processes [2]. |

| CellML | Model Encoding Standard | An XML-based language for storing and sharing mathematical models, with a strong emphasis on unit consistency and modular component reuse [2]. |

| MIRIAM Guidelines | Annotation Standard | Defines the minimum information required for annotating biochemical models, ensuring model components are unambiguously linked to biological entities, which is crucial for reproducibility [2]. |

| BioModels Database | Model Repository | A curated resource of published, peer-reviewed computational models, providing access to reproducible models for validation and benchmarking [2]. |

| Risk Management Plan (RMP) | Regulatory Document Template (EMA) | The structured template required by EMA for detailing pharmacovigilance activities and risk minimization measures, which may include model-based safety analyses [15] [14]. |

| Common Technical Document (CTD) | Regulatory Submission Format | The internationally agreed-upon format for submitting regulatory applications to both FDA and EMA, organizing the information into five modules [14]. |

| NASA "Ten Rules" Rubric | Credibility Assessment Tool | A conformance checklist and guidance for establishing model credibility, adaptable from aerospace to biomedical applications [16]. |

Signaling Pathways in Regulatory Submissions

The interaction between different credibility standards and the regulatory submission pathway can be conceptualized as an integrated system. The following diagram maps the logical flow from model development through the application of agency-specific standards to a final regulatory outcome.

Figure 2: A signaling pathway illustrating how computational models and data are processed through agency-specific credibility standards (FDA, EMA, and the influential NASA framework) to inform regulatory submissions and final decisions.

The integration of in silico clinical trials into regulatory decision-making represents one of the most significant transformations in medical product development. As regulatory agencies increasingly accept computational evidence, establishing model credibility has become paramount for researchers and developers. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) now explicitly states that verified virtual evidence can support regulatory submissions for devices and biologics, fundamentally changing the evidence requirements for market approval [17]. This paradigm shift demands rigorous validation frameworks to ensure that computational models reliably predict real-world clinical outcomes, particularly when these models aim to reduce, refine, or replace traditional human and animal testing [18] [19].

The FDA's 2023 guidance document "Assessing the Credibility of Computational Modeling and Simulation in Medical Device Submissions" provides a risk-informed framework for evaluating computational evidence, signaling a maturation of regulatory standards for in silico methodologies [3]. This guidance, coupled with recent legislative changes such as the FDA Modernization Act 2.0 which removed the mandatory animal testing requirement for drugs, has created both unprecedented opportunities and substantial validation challenges for researchers [20]. Within this evolving landscape, this article examines the concrete standards, experimental protocols, and validation methodologies that underpin credible in silico approaches to regulatory submissions.

Establishing Credibility: Frameworks and Standards

Regulatory Foundations and Validation Frameworks

Regulatory acceptance of in silico evidence hinges on systematic credibility assessment following established frameworks. The ASME V&V 40 standard provides the foundational framework for assessing computational model credibility, offering a risk-informed approach that links validation activities to a model's context of use [17] [21]. This standard has been directly referenced in FDA guidance documents and has seen practical application in developing regulatory-grade models, such as the Bologna Biomechanical Computed Tomography solution for hip fracture risk prediction [21].

The FDA's risk-informed credibility assessment framework evaluates computational modeling and simulation (CM&S) through multiple evidence dimensions [3]. This approach requires researchers to establish a clear context of use (COU) statement that precisely defines the role and scope of the computational model within the regulatory decision-making process. The level of required credibility evidence escalates with the model's risk influence factor – a measure of how substantially the computational results will impact regulatory determinations of safety and effectiveness.

Table 1: Key Regulatory Developments Enabling In Silico Submissions

| Date | Agency | Policy/Milestone | Impact on In Silico Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| December 2022 | U.S. Congress | FDA Modernization Act 2.0 | Removed statutory animal-test mandate; recognized in silico models as valid nonclinical tests [20] |

| November 2023 | FDA | CM&S Credibility Assessment Guidance | Formalized risk-informed framework for evaluating computational evidence in medical device submissions [3] |

| April 2025 | FDA | Animal Testing Phase-Out Roadmap | Announced plan to reduce/Replace routine animal testing, prioritizing MPS data and AI-driven models [18] [20] |

| September 2024 | FDA | First Organ-Chip in ISTAND Program | Accepted Liver-Chip S1 for predicting drug-induced liver injury, setting procedural precedent [20] |

Credibility Evidence Requirements and Documentation

Building a persuasive credibility dossier requires multifaceted evidence across technical and biological domains. The FDA's framework emphasizes three interconnected evidence categories: computational verification (ensuring models are solved correctly), experimental validation (confirming models accurately represent reality), and uncertainty quantification (characterizing variability and error) [3]. For high-impact regulatory submissions, developers must provide comprehensive documentation spanning model assumptions, mathematical foundations, input parameters, and validation protocols.

Technical credibility requires demonstration of numerical verification through mesh convergence studies, time step independence analyses, and solver accuracy assessments. Meanwhile, physical validation demands comparison against high-quality experimental data, with increasing rigor required for higher-stakes applications. The emerging best practice involves creating a validation hierarchy where model components are validated against simpler systems before progressing to full organ-level or organism-level validation [3].

In Silico Trials in Regulatory Submissions: Applications and Outcomes

Therapeutic Area Implementation and Impact

In silico methodologies have demonstrated particularly strong value in therapeutic areas where traditional trials face ethical, practical, or financial constraints. Oncology represents the largest application segment, capturing 25.78% of the in silico clinical trials market in 2024, with projections reaching $1.6 billion by 2030 [17]. The complexity of multi-drug regimens and significant tumor genetic heterogeneity in oncology benefit tremendously from in silico dose optimization and the creation of large synthetic cohorts to achieve statistical power.

Neurology has emerged as the fastest-growing discipline with a 15.46% CAGR, driven by advanced applications such as Stanford's visual-cortex digital twin that enables unlimited virtual experimentation [17]. The repeated failures of Alzheimer's candidates in late-stage traditional trials have highlighted the limitations of conventional models and created urgency for more predictive computational approaches that can simulate long-term disease progression and stratify patients by digital biomarkers [19].

Table 2: In Silico Clinical Trial Applications Across Development Phases

| Development Phase | Primary Applications | Reported Impact | Example Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preclinical | PBPK models, toxicity screening, animal study reduction | Flags risky compounds early; reduces animal use [22] | Roche's AI surrogate model for T-DM1 dose selection [22] |

| Phase I | First-in-human dose prediction, virtual cohort generation | Rising fastest at 13.78% CAGR; could surpass $510M by 2030 [17] | AI-designed compounds with pre-computed toxicity profiles [17] |

| Phase II | Dose optimization, synthetic control arms, efficacy assessment | Constituted 34.85% of deployments in 2024 [17] | AstraZeneca's QSP model for PCSK9 therapy (6-month acceleration) [22] |

| Phase III/Registrational | Trial design optimization, digital twin control arms | Synthetic control arms reduce enrollment by 20% [17] | Pfizer's PK/PD simulations for tofacitinib (replaced Phase 3 trials) [22] |

| Post-Approval | Long-term safety extrapolation, label expansion simulations | Enhanced surveillance with real-world data feeds [17] [22] | BMS-PathAI partnership for PD-L1 scoring in tumor slides [22] |

Regulatory Precedents and Successful Submissions

Several landmark regulatory submissions have demonstrated the viability of in silico evidence as a primary component of regulatory packages. Pfizer secured FDA acceptance for in silico PK/PD simulation data bridging efficacy between immediate- and extended-release tofacitinib for ulcerative colitis, eliminating the need for new phase 3 trials [22] [23]. This precedent confirms that properly validated computational models can substantially reduce traditional clinical trial requirements for approved molecules seeking formulation changes.

In the medical device sector, the FDA approved the restor3d Total Talus Replacement based primarily on computational design from patient CT data, demonstrating that in silico engineering approaches can meet safety thresholds for implantable devices [17]. Similarly, Medtronic utilized computational fluid dynamics (CFD) virtual trials to predict aneurysm flow reduction for its Pipeline Embolization Device, with results correlating well with subsequent clinical trial outcomes [23].

The expanding regulatory acceptance is reflected in market data: the in-silico clinical trials market size reached $3.95 billion in 2024 and is projected to grow to $6.39 billion by 2033, demonstrating increasing integration into mainstream development pathways [24].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Core Validation Methodologies

Establishing model credibility requires rigorous experimental protocols that systematically evaluate predictive performance against relevant clinical data. The following standardized protocol outlines key validation steps:

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Model Validation

- Context of Use Definition: Precisely specify the model's regulatory application, including specific clinical endpoints and patient populations.

- Validation Hierarchy Establishment: Define a cascade of validation benchmarks from simple systems (cellular, tissue) to complex organ-level or population-level responses.

- Reference Data Collection: Curate high-quality clinical or experimental data for comparison, documenting sources, demographics, and measurement uncertainties.

- Model Prediction: Generate computational results for validation cases without reference to outcome data (prospective prediction preferred).

- Comparison Metrics Application: Calculate quantitative agreement metrics including mean absolute error, correlation coefficients, and confidence intervals.

- Uncertainty Quantification: Characterize uncertainty from input parameters, numerical approximations, and biological variability.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Identify influential parameters and assumptions through local (one-at-a-time) or global (variance-based) methods.

- Documentation and Reporting: Compile comprehensive validation report including all inputs, methods, results, and limitations.

This structured approach aligns with the ASME V&V 40 framework and FDA guidance recommendations, emphasizing transparency and methodological rigor [21] [3].

Technical Workflow for In Silico Trial Implementation

The implementation of regulatory-grade in silico trials requires integration of multiple computational and data modules into a cohesive workflow. The leading framework comprises six tightly integrated components that simulate different aspects of clinical trials [22]:

Figure 1: In Silico Trial Workflow illustrating the six modular components and their interactions, with feedback loops enabling iterative refinement.

This workflow creates an iterative system where outputs from later stages can refine earlier modules. For instance, operational simulations might reveal that certain protocol designs are impractical to implement, triggering protocol redesign before resimulation [22]. This iterative refinement capability represents a significant advantage over traditional static trial designs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

Implementing credible in silico trials requires specialized computational tools and platforms validated for regulatory applications. The following table details essential solutions across key functional categories:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for In Silico Trials

| Tool Category | Representative Platforms | Primary Function | Regulatory Validation Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| PK/PD Modeling | Certara Phoenix, Simulations Plus | Predicts drug concentration and effect relationships; supports dose selection | Used in 75+ top pharma companies; accepted by 11 regulatory agencies [24] |

| Medical Device Simulation | ANSYS, Dassault Systèmes | Physics-based modeling of device performance and tissue interactions | FDA acceptance for implantable devices (e.g., restor3d Talus Replacement) [17] |

| Virtual Patient Generation | Insilico Medicine, InSilicoTrials | Creates synthetic patient cohorts with realistic characteristics and variability | Deployed in Phase I supplement studies; synthetic control arms [17] [23] |

| Trial Operational Simulation | The AnyLogic Company, Nova | Models recruitment, site activation, and other operational factors | Integrated into protocol optimization workflows at major CROs [22] [24] |

| QSP Platforms | Physiomics Plc, VeriSIM Life | Mechanistic modeling of drug effects across biological pathways | Used in AstraZeneca's PCSK9 accelerator program (6-month time saving) [22] [23] |

Beyond commercial platforms, successful in silico trial implementation requires robust data management infrastructures that adhere to FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable). The integration of real-world data from electronic health records, wearable sensors, and patient registries provides essential training and validation datasets for refining computational models [22]. Emerging best practices also emphasize the importance of version control systems for computational models and comprehensive documentation pipelines that track all model modifications and assumptions throughout the development process.

Signaling Pathways: The Credibility Assessment Framework

The credibility assessment process for regulatory submissions follows a systematic pathway that evaluates multiple evidence dimensions. The following diagram illustrates the key decision points and validation requirements:

Figure 2: Credibility Assessment Framework depicting the systematic pathway from context definition to regulatory decision, emphasizing evidence requirements.

This assessment pathway begins with precise Context of Use (COU) specification, which determines the model's purpose and regulatory impact. The Risk Influence Factor assessment then establishes the required evidence level, with higher-risk applications demanding more extensive validation [3]. Evidence gathering encompasses three interconnected domains: Verification and Validation (V&V) confirms numerical accuracy and predictive capability; Uncertainty Quantification characterizes variability and error; and Sensitivity Analysis identifies influential parameters and assumptions. The cumulative evidence supports the final regulatory determination of model credibility for the specified context.

The integration of in silico methodologies into regulatory submissions represents a fundamental transformation in medical product development. As regulatory agencies increasingly accept computational evidence, establishing model credibility through rigorous validation frameworks has become essential. The convergence of regulatory modernization, computational advancement, and growing clinical validation has created an inflection point where in silico trials are transitioning from supplemental to central components of development pipelines.

The successful examples from industry leaders demonstrate that properly validated computational models can accelerate development timelines by 25% or more while reducing costs and ethical burdens [25]. However, realizing this potential requires meticulous attention to credibility frameworks, comprehensive validation protocols, and transparent documentation. The institutions that master these competencies will lead the next era of medical product development, where simulation informs every stage from discovery through post-market surveillance.

For researchers and developers, the imperative is clear: invest in robust validation methodologies, maintain rigorous documentation practices, and actively engage with evolving regulatory expectations. As one editorial starkly concluded, "In a decade, failing to run in silico trials may not just be seen as a missed opportunity. It may be malpractice" [19]. The standards for computational credibility are being written today through pioneering submissions that establish precedents for the entire field.

From Theory to Practice: Implementing Verification, Validation, and Uncertainty Quantification

The ASME V&V 40-2018 standard provides a risk-informed framework for establishing credibility requirements for computational models used in medical device evaluation and other high-consequence fields [7] [4]. This standard has become a key enabler for regulatory submissions, forming the basis of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) CDRH framework for evaluating computational modeling and simulation data in medical device submissions [7] [3]. The core innovation of V&V 40 lies in its risk-based approach to verification and validation (V&V), which tailors the rigor and extent of credibility activities to the model's specific context of use and the decision-related risks involved [7].

The standard introduces credibility factors as essential attributes that determine a model's trustworthiness for its intended purpose. These factors guide the planning and execution of V&V activities, ensuring that computational models provide sufficient evidence to support high-stakes decisions in medical device development, regulatory evaluation, and increasingly in in-silico clinical trials (ISCTs) [7] [26]. The framework acknowledges that different modeling contexts require different levels of evidence, and it provides a structured methodology for determining the appropriate level of V&V activities based on the model's role in decision-making and the potential consequences of an incorrect result [3].

Core Components of the Credibility Factor Framework

Foundational Principles and Risk-Based Approach

The Credibility Factor Framework operates on several foundational principles that distinguish it from traditional V&V approaches. First, it explicitly recognizes that not all models require the same level of validation – the necessary credibility evidence is directly proportional to the model's decision consequence, meaning the impact that an incorrect model result would have on the overall decision [7]. Second, the framework emphasizes a systematic planning process that begins with clearly defining the context of use, which includes the specific question the model will answer, the relevant physical quantities of interest, and the required accuracy [3].

The risk-based approach incorporates two key dimensions: decision consequence and model influence. Decision consequence categorizes the potential impact of an incorrect model result (low, medium, or high), while model influence assesses how much the model output contributes to the overall decision (supplemental, influential, or decisive). These dimensions collectively determine the required credibility level for each credibility factor [7] [3]. This nuanced approach represents a significant advancement over one-size-fits-all validation requirements, enabling more efficient allocation of V&V resources while maintaining scientific rigor where it matters most.

Key Credibility Factors and Corresponding V&V Activities

The framework identifies specific credibility factors that must be addressed to establish model trustworthiness. For each factor, the standard outlines a continuum of potential V&V activities ranging from basic to comprehensive, with the appropriate level determined by the risk assessment [7]. The following table summarizes the core credibility factors and their corresponding V&V activities:

Table: Core Credibility Factors and Corresponding V&V Activities in ASME V&V 40

| Credibility Factor | Description | Example V&V Activities |

|---|---|---|

| Verification | Ensuring the computational model is implemented correctly and without error [7]. | Code verification, calculation verification, systematic mesh refinement [7]. |

| Validation | Determining how accurately the computational model represents the real-world system [7]. | Comparison with experimental data, historical data as comparator, validation experiments [7] [21]. |

| Uncertainty Quantification | Characterizing and quantifying uncertainties in model inputs, parameters, and predictions [27]. | Sensitivity analysis, statistical uncertainty propagation, confidence interval estimation [27]. |

| Model Form | Assessing the appropriateness of the underlying mathematical models and assumptions [7]. | Comparison with alternative model forms, evaluation of simplifying assumptions [7]. |

| Input Data | Evaluating the quality and appropriateness of data used to define model inputs and parameters [7]. | Data provenance assessment, parameter sensitivity analysis, input uncertainty characterization [7]. |

Experimental Protocols for Credibility Assessment

Verification Protocols: Code and Calculation Verification

Verification constitutes the foundational layer of credibility assessment, ensuring that the computational model is implemented correctly and solved accurately. The protocol begins with code verification, which confirms that the mathematical algorithms are implemented without programming errors. This typically involves comparing computational results against analytical solutions for simplified cases where exact solutions are known [7].

Calculation verification follows, focusing on quantifying numerical errors in specific solutions. As highlighted in recent applications, systematic mesh refinement plays a critical role in this process [7]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Generating a series of computational meshes with progressively refined element sizes

- Solving the boundary value problem on each mesh

- Quantifying solution metrics of interest for each mesh refinement level

- Analyzing the convergence behavior of these metrics as mesh size decreases

- Extrapolating to estimate the discretization error at zero mesh size

Research demonstrates that failing to apply systematic mesh refinement can produce misleading results, particularly for complex simulations like blood hemolysis modeling [7]. For unstructured meshes with nonuniform element sizes, maintaining systematic refinement requires special attention to often-overlooked aspects such as consistent element quality metrics across refinement levels [7].

Validation Protocols: Comparative Analysis and Uncertainty Quantification

Validation protocols determine how accurately a computational model represents real-world physics. The standard approach involves hierarchical testing, beginning with component-level validation and progressing to system-level validation as needed based on the risk assessment [7] [3]. The validation protocol comprises:

- Designing validation experiments that isolate specific physical phenomena relevant to the context of use

- Quantifying experimental uncertainty through repeated measurements and statistical analysis

- Comparing computational results with experimental data using predefined validation metrics

- Assessing agreement through both quantitative measures and qualitative engineering judgment

For patient-specific models, such as those used in femur fracture prediction, validation presents unique challenges. The ASME VVUQ 40 sub-committee is developing a classification framework for comparators that assesses the credibility of patient-specific computational models [7]. This framework defines, classifies, and compares different types of comparators (e.g., direct experimental measurements, clinical imaging, historical data), highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of each comparator type, and providing rationale for selection [7].

A key advancement in validation methodology is the formal uncertainty quantification process, which characterizes both computational and experimental uncertainties and propagates them through the model to determine whether differences between simulation and experiment are statistically significant [27]. This represents a shift from binary pass/fail validation to a probabilistic assessment of agreement.

Workflow Visualization: Credibility Factor Assessment Process

The following diagram illustrates the systematic workflow for planning V&V activities using the Credibility Factor Framework:

Diagram: Credibility Factor Assessment Workflow. This workflow illustrates the iterative process of establishing model credibility according to ASME V&V 40.

Comparative Analysis of V&V Implementation Scenarios

The application of the Credibility Factor Framework varies significantly based on the modeling context and application domain. The following table compares implementation approaches across different scenarios, highlighting how V&V activities are tailored to specific contexts:

Table: Comparative Analysis of V&V Implementation Across Application Domains

| Application Domain | Context of Use | Key Credibility Factors | Implementation Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Medical Devices | Evaluation of tibial tray durability [7] | Model verification, validation, uncertainty quantification | Comprehensive verification via mesh refinement; physical testing validation; moderate UQ |

| In-Silico Clinical Trials | Synthetic patient cohorts for trial simulation [26] | Model form validity, predictive capability, uncertainty quantification | High-fidelity validation against historical data; extensive UQ for population variability |

| Patient-Specific Modeling | Femur fracture prediction [7] [21] | Input data credibility, validation with clinical data | Classification framework for comparators; imaging data validation; specialized UQ |

| Digital Twins in Manufacturing | Real-time decision support [27] | Ongoing verification, continuous validation, UQ | Lifecycle V&V approach; real-time validation with sensor data; dynamic UQ |

The comparative analysis reveals that while the fundamental credibility factors remain consistent, their implementation varies based on the model's context of use. For traditional medical devices, the focus remains on rigorous verification and physical validation [7]. In contrast, in-silico clinical trials emphasize predictive capability and comprehensive uncertainty quantification due to their role in augmenting or replacing human clinical trials [26]. Patient-specific models require specialized approaches to validation, often relying on medical imaging data as comparators rather than traditional physical experiments [7]. For digital twins in manufacturing, the credibility assessment extends throughout the entire lifecycle, requiring continuous rather than one-time V&V activities [27].

Successful implementation of the Credibility Factor Framework requires both methodological expertise and practical tools. The following table details essential resources for researchers planning V&V activities:

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Credibility Assessment

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ASME VVUQ 40.1 Technical Report | Provides detailed example applying V&V 40 to a tibial tray durability model [7] | Medical device evaluation; educational resource |

| Systematic Mesh Refinement Tools | Enables code and calculation verification through controlled mesh refinement studies [7] | Finite element analysis; computational fluid dynamics |

| Comparator Classification Framework | Guides selection of appropriate comparators for model validation, especially for patient-specific models [7] | Patient-specific modeling; clinical applications |

| Uncertainty Quantification Software | Characterizes and propagates uncertainties through computational models [27] | Risk assessment; predictive modeling |

| FDA Credibility Assessment Guidance | Provides regulatory perspective on implementing credibility factors for medical devices [3] | Regulatory submissions; medical device development |

Future Directions and Emerging Applications

The Credibility Factor Framework continues to evolve through standardization efforts and emerging applications. The ASME VVUQ 40 sub-committee is actively working on several extensions, including technical reports focused on patient-specific modeling and specialized applications [7]. These efforts aim to address unique challenges in personalized medicine and clinical decision support, where traditional V&V approaches may require adaptation [7] [21].