Evaluating Foundation Models in Bioinformatics: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Benchmarking

Foundation models are revolutionizing bioinformatics by providing powerful, adaptable tools for analyzing complex biological data.

Evaluating Foundation Models in Bioinformatics: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Benchmarking

Abstract

Foundation models are revolutionizing bioinformatics by providing powerful, adaptable tools for analyzing complex biological data. This article offers a critical evaluation of these models for researchers and drug development professionals, addressing their core concepts, diverse methodological applications across genomics, transcriptomics, and drug discovery, and the significant challenges of data fragmentation and interpretability. It provides a practical framework for model selection, troubleshooting, and optimization, synthesizing insights from recent benchmarking studies to guide the effective implementation of foundation models in both research and clinical settings.

Demystifying Foundation Models: Core Concepts and the Current Landscape in Bioinformatics

What Are Foundation Models? Defining Large-Scale, Self-Supervised AI for Biology

Foundation Models (FMs) are large-scale artificial intelligence systems pre-trained on vast, unlabeled datasets using self-supervised learning, enabling them to be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks. In biology, these models are reconceptualizing biological sequences and structures—from DNA and proteins to single-cell data—as a form of language amenable to advanced computational analysis. This guide objectively compares the performance of leading FMs against traditional methods and simpler baselines in key bioinformatics applications, providing supporting experimental data to inform researchers and drug development professionals. The evaluation reveals that while FMs show immense promise, their performance is context-dependent, and in several cases, they are surprisingly outperformed by more straightforward approaches.

Foundation Models (FMs) represent a paradigm shift in bioinformatics artificial intelligence (AI). They are large-scale models pre-trained on extensive datasets, which allows them to learn fundamental patterns and relationships within the data. This pre-training is typically done using self-supervised learning, a method that generates labels directly from the data itself, eliminating the need for vast, manually curated datasets. Once pre-trained, these models can be adapted (fine-tuned) for a diverse array of specific downstream tasks with relatively minimal task-specific data [1] [2].

In biology, FMs treat biological entities—such as nucleotide sequences, amino acid chains, or gene expression profiles—as structured sequences or "languages." By learning the statistical patterns and complex grammar of these languages, FMs can make predictions about structure, function, and interactions that were previously challenging for computational methods [3]. The evolution of these models has progressed from task-specific networks to sophisticated, multi-purpose architectures like the AlphaFold series for protein structure prediction and transformer-based models like DNABERT for genomic sequence analysis [2].

Performance Comparison of Foundation Models

Independent benchmarking studies are crucial for evaluating the real-world performance of FMs against traditional and baseline methods. The data below summarizes findings from recent, rigorous comparisons.

Performance on Post-Perturbation Gene Expression Prediction

Predicting a cell's transcriptomic response to a genetic perturbation is a critical task in functional genomics and drug discovery. The table below benchmarks specialized foundation models against simpler baseline models across several key datasets [4].

- Datasets: Adamson (CRISPRi), Norman (CRISPRa), Replogle (CRISPRi in K562 & RPE1 cells)

- Primary Metric: Pearson correlation in differential expression space (Pearson Delta), comparing predicted vs. true pseudo-bulk expression profiles.

- Key Comparison:

- Foundation Models: scGPT, scFoundation

- Baseline Models: Train Mean (predicts the average training profile), Random Forest (RF) with Gene Ontology (GO) features, RF with model embeddings.

Table 1: Benchmarking Post-Perturbation Prediction Models (Pearson Delta Metric) [4]

| Model | Adamson | Norman | Replogle (K562) | Replogle (RPE1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train Mean (Baseline) | 0.711 | 0.557 | 0.373 | 0.628 |

| RF with GO Features | 0.739 | 0.586 | 0.480 | 0.648 |

| scGPT (FM) | 0.641 | 0.554 | 0.327 | 0.596 |

| scFoundation (FM) | 0.552 | 0.459 | 0.269 | 0.471 |

| RF with scGPT Embeddings | 0.727 | 0.583 | 0.421 | 0.635 |

Analysis: The data reveals that even the simplest baseline, Train Mean, outperformed both scGPT and scFoundation across all four datasets. Furthermore, a Random Forest model using biologically meaningful GO features significantly surpassed the foundation models. Notably, using scGPT's own embeddings within a Random Forest model yielded better performance than the fine-tuned scGPT model itself, suggesting the embeddings contain valuable information that the full FM's architecture may not be leveraging optimally for this task [4].

Performance on Single-Cell Data Representation

For single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data, a primary application of FMs is to learn meaningful embeddings of cell states that can be used for zero-shot tasks like cell-type clustering without additional fine-tuning.

Table 2: Benchmarking Single-Cell Foundation Models on Zero-Shot Clustering [5]

| Model Type | Example Models | Performance vs. Baselines |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Cell FMs | Geneformer, scGPT | In most evaluation tasks, these large models did not outperform simpler competitor methods. Their learned representations did not consistently reflect the claimed biological insight. |

| Simpler Methods | (e.g., PCA, standard autoencoders) | Often provided equal or better performance for tasks like cell-type clustering and batch integration. |

Analysis: A 2025 evaluation by Kedzierska and Lu found that the promise of zero-shot biological insight from single-cell FM embeddings is not yet fully realized. Contrary to expectations, their massive scale and complexity did not automatically translate to superior performance over more established and less complex methods for fundamental analysis tasks [5].

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

To ensure the reproducibility and validity of the comparisons presented, this section details the core experimental methodologies employed in the cited benchmarks.

Protocol for Post-Perturbation Prediction

The benchmarking study for models like scGPT and scFoundation followed a rigorous, standardized protocol [4]:

- Model Fine-Tuning: The pre-trained foundation models (scGPT and scFoundation) were fine-tuned on the target Perturb-seq datasets (Adamson, Norman, Replogle) according to their authors' specifications.

- Baseline Model Implementation:

- Train Mean: The pseudo-bulk expression profile (average of all single-cell profiles) was computed for each perturbation in the training set. The overall mean of these training profiles was used as the prediction for every test sample.

- Random Forest Models: A Random Forest Regressor was trained using prior-knowledge features. For a given perturbation (e.g., knockout of gene X), the input feature was the GO term vector or model-derived embedding of gene X. The target was the pseudo-bulk expression profile for that perturbation.

- Evaluation Metric Calculation:

- Predictions were made at the single-cell level and then averaged to create a pseudo-bulk profile per perturbation.

- Pearson Delta: The Pearson correlation was calculated between the ground truth pseudo-bulk profile and the predicted pseudo-bulk profile. This was done in the differential expression space, meaning the control profile was subtracted from both the predicted and ground-truth perturbed profiles before correlation.

- Performance was also assessed on the top 20 differentially expressed genes to focus on the most significant changes.

Protocol for Single-Cell Representation Learning

The evaluation of single-cell FMs like Geneformer and scGPT focused on their zero-shot capabilities [5]:

- Embedding Extraction: The pre-trained models (without further fine-tuning on the evaluation datasets) were used to generate embedding representations for cells from a hold-out dataset.

- Task Application: These embeddings were directly used as input for standard downstream analysis tasks, including:

- Cell-Type Clustering: Applying clustering algorithms (e.g., K-means, Leiden) to the embeddings and comparing the resulting clusters to known cell-type labels using metrics like Adjusted Rand Index (ARI).

- Batch Integration: Evaluating how well the embeddings mixed cells from different experimental batches while preserving separation between distinct cell types.

- Comparison to Baselines: The performance on these tasks was compared against the performance achieved using embeddings from simpler, non-foundation model methods, such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or standard autoencoders.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

The development and application of biological FMs rely on specific data types and computational resources. The following table details these essential "research reagents."

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Biological Foundation Model Research

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Foundation Model Research |

|---|---|

| UniProt Knowledgebase [3] | A comprehensive database of protein sequence and functional information. Serves as a primary pre-training corpus for protein-language models like ProtGPT2 and ProtBERT. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [3] | The single global archive for 3D structural data of proteins and nucleic acids. Critical for training and validating structure prediction models like AlphaFold and ESMFold. |

| Perturb-seq Datasets [4] | Combinatorial CRISPR-based perturbations with single-cell RNA sequencing readouts. The standard benchmark for evaluating model predictions of transcriptional responses to genetic interventions. |

| Model Embeddings (e.g., from scGPT, DNABERT) | Dense numerical representations of biological entities (genes, cells, sequences) learned by the FM. They can be used as features in simpler models (like Random Forest) for specific tasks. |

| Gene Ontology (GO) Vectors [4] | Structured, controlled vocabularies (ontologies) describing gene function. Used as biologically meaningful input features for baseline models, often outperforming raw FM outputs in benchmarks. |

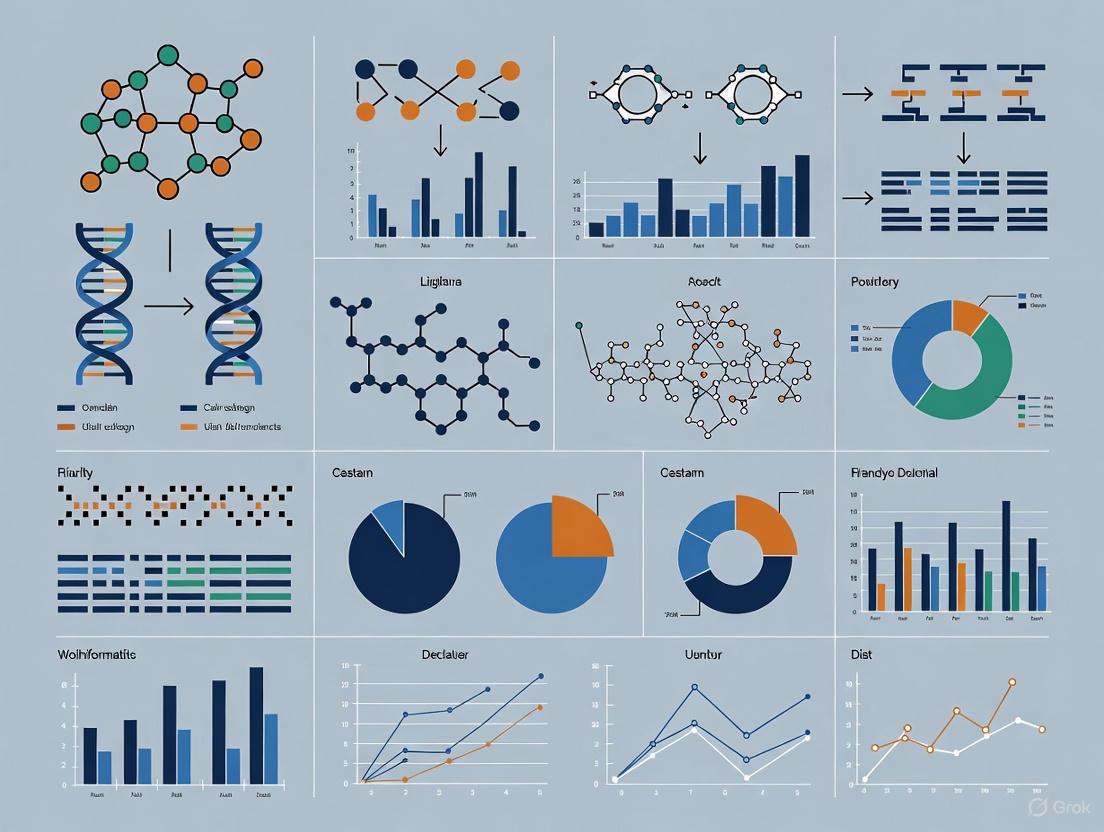

Workflow Diagram: From Pre-training to Biological Insight

The following diagram illustrates the standard workflow for developing and applying a foundation model in bioinformatics, from self-supervised pre-training to task-specific fine-tuning and benchmarking.

The landscape of foundation models in biology is dynamic and promising. Models like AlphaFold have demonstrated revolutionary capabilities in specific domains like protein structure prediction [3] [2]. However, independent benchmarking provides a necessary critical perspective. As the data shows, for tasks such as predicting transcriptional responses to perturbation or zero-shot cell type identification, large, complex FMs do not uniformly outperform simpler, often more interpretable, methods [4] [5].

The choice of model should therefore be guided by the specific biological question and data context. Researchers are advised to:

- Consider Simpler Baselines: Always benchmark FMs against straightforward baselines, like mean predictors or models using established biological features (e.g., GO terms).

- Evaluate Embeddings Separately: The embeddings learned by FMs can be valuable even if the full model is suboptimal for a task; using them as features in other models can yield better performance.

- Acknowledge Data Limitations: FMs require massive datasets for pre-training, and their performance can be constrained by the quality and scope of available biological data, especially for rare cell types [6].

The future of FMs in bioinformatics lies not only in scaling up but also in smarter architecture design, improved benchmarking, and the development of data-efficient "on-device" learning strategies to tackle the vast diversity of biological systems [6].

The field of bioinformatics is undergoing a paradigm shift driven by the adoption of foundation models—large-scale, self-supervised artificial intelligence models trained on extensive datasets that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks [1]. These models, predominantly built on transformer architectures with attention mechanisms, are reconceptualizing biological sequences—from DNA and proteins to single-cell data—as a form of 'language' amenable to advanced computational techniques [3]. This approach has created new opportunities for interpreting complex biological systems and accelerating biomedical research. The primary architectural backbone enabling these advances is the transformer, which utilizes attention mechanisms to weight the importance of different elements in input data, allowing models to capture intricate long-range relationships in biological sequences [7] [1]. These technical foundations are now being applied to diverse biological data types, creating specialized foundation models for genomics, single-cell analysis, and protein research that demonstrate remarkable adaptability across downstream tasks. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these key architectural paradigms, their performance across biological domains, and the experimental methodologies used for their evaluation, framed within the broader context of assessing foundation models in bioinformatics research.

Architectural Foundations and Biological Adaptations

Core Transformer Architecture and Attention Mechanisms

The transformer architecture, originally developed for natural language processing, has become the fundamental building block for biological foundation models. Transformers are neural network architectures characterized by self-attention mechanisms that allow the model to learn and weight relationships between any pair of input tokens [7]. In biological applications, this enables models to determine which genes, nucleotides, or amino acids in a sequence are most informative for predicting structure, function, or relationships. The key innovation of transformers is their multi-head self-attention mechanism, which computes weighted sums of values where the weights are determined by compatibility queries and keys, allowing the model to jointly attend to information from different representation subspaces [1]. This capability is particularly valuable in biological contexts where long-range dependencies—such as the relationship between distant genomic regions or amino acids in a protein structure—play critical functional roles.

The self-attention mechanism operates through three fundamental components: Query (Q), Key (K), and Value (V). Given an input sequence of embeddings, these embeddings are linearly transformed into query, key, and value spaces using learnable weight matrices. The attention operation is formally defined as:

[ \text{Attention}(Q,K,V)=\text{softmax}\left(\frac{QK^{T}}{\sqrt{d_{k}}}\right)V ]

where (d_{k}) represents the dimension of the key vectors [8]. This mechanism allows the model to selectively focus on the most relevant features when making predictions, analogous to how biological systems prioritize information processing.

Biological Sequence Tokenization Strategies

A critical adaptation of transformers to biological data involves tokenization—the process of converting raw biological sequences into discrete units that the model can process. Unlike natural language, biological sequences lack inherent ordering, requiring specialized tokenization strategies:

- DNA Sequences: Typically tokenized at single-nucleotide, k-mer, or codon levels, with models like Nucleotide Transformer using 6kb sequence contexts [9].

- Protein Sequences: Amino acids serve as natural tokens, though some models incorporate higher-order structural information [3].

- Single-Cell Data: Genes or genomic features become tokens, with expression values incorporated through binning or normalization strategies [7]. Some models rank genes by expression levels to create deterministic sequences, while others use special tokens to represent cell identity, metadata, or experimental batch information [7].

Positional encoding schemes are adapted to represent the relative order or rank of each element in the biological sequence, overcoming the non-sequential nature of data like gene expression profiles [7].

Emerging Architectural Variants

Recent research has explored specialized transformer architectures tailored to biological data's unique characteristics:

- Neuromorphic Transformers: The Spiking STDP Transformer (S2TDPT) implements self-attention through spike-timing-dependent plasticity (STDP), embedding query-key correlations in synaptic weights for extreme energy efficiency (88.47% reduction compared to standard ANN Transformers) while maintaining competitive accuracy [8].

- Bidirectional vs. Autoregressive Models: Discriminative foundation models like BERT variants use bidirectional context to capture semantic meaning, while generative models like GPT variants employ autoregressive methods for sequence generation [1].

- Hierarchical and Multi-Scale Architectures: Some models incorporate mechanisms to capture biological information at different scales, from nucleotide-level to chromosome-level interactions [9].

Performance Comparison of Biological Foundation Models

Table 1: Performance Comparison of DNA Foundation Models on Genomic Tasks

| Model | Parameters | Training Data | Average MCC (18 tasks) | Fine-tuning Efficiency | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide Transformer (Multispecies 2.5B) | 2.5 billion | 850 species genomes | 0.683 (matches or surpasses baseline in 12/18 tasks) | 0.1% of parameters needed | Best overall performance, strong cross-species generalization |

| Nucleotide Transformer (1000G 2.5B) | 2.5 billion | 3,202 human genomes | 0.672 | 0.1% of parameters needed | Excellent human-specific performance |

| Nucleotide Transformer (1000G 500M) | 500 million | 3,202 human genomes | 0.655 | 0.1% of parameters needed | Good performance with reduced computational requirements |

| DNA BERT | Varies | Human reference genome | ~0.61 (probing) | Full fine-tuning typically required | Established benchmark for DNA language modeling |

| BPNet (supervised baseline) | 28 million | Task-specific | 0.683 | N/A (trained from scratch) | Strong task-specific performance |

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Single-Cell Foundation Models

| Model | Parameters | Training Data | Zero-shot Clustering Performance | Key Limitations | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scGPT | ~100 million | CellxGene (100M+ cells) | Underperforms traditional methods | Poor masked gene expression prediction | Fine-tuning on specific cell types |

| Geneformer | ~100 million | 30 million single-cell profiles | Underperforms traditional methods | Limited biological insight in embeddings | Transfer learning with extensive fine-tuning |

| scVI (traditional baseline) | ~1-10 million | Dataset-specific | Superior clustering by cell type | Requires per-dataset training | Standard clustering and batch correction |

| Harmony (statistical baseline) | N/A | Dataset-specific | Superior batch effect correction | No transfer learning capability | Data integration and batch correction |

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Protein Language Models

| Model | Architecture | Key Applications | Notable Achievements | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProtTrans | Transformer | Structure and function prediction | Competitive with specialized methods | Computational intensity |

| ESM | Transformer | Structure prediction | State-of-the-art accuracy | Requires fine-tuning for specific tasks |

| AlphaFold | Hybrid (CNN+Transformer) | Structure prediction | Near-experimental accuracy | Not a pure language model |

| ProteinBERT | BERT-like | Function prediction | Universal sequence-function modeling | Limited structural awareness |

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation Methodologies

Standardized Benchmarking Approaches

Rigorous evaluation of biological foundation models requires standardized benchmarks and experimental protocols. For DNA foundation models like Nucleotide Transformer, evaluation typically involves:

- Task Diversity: Curated datasets encompassing splice site prediction (GENCODE), promoter identification (Eukaryotic Promoter Database), histone modification prediction (ENCODE), and enhancer activity prediction [9].

- Evaluation Strategies: Two primary approaches are employed:

- Probing: Using learned embeddings as input features to simpler models (logistic regression or small MLP) to assess representation quality.

- Fine-tuning: Replacing the model head with task-specific layers and retraining with parameter-efficient techniques.

- Cross-Validation: Rigorous k-fold cross-validation (typically 10-fold) to ensure statistical significance of results [9].

For the Nucleotide Transformer, researchers curated 18 genomic datasets processed into standardized formats to facilitate reproducible benchmarking. Performance is measured using Matthews Correlation Coefficient (MCC) for classification tasks, providing a balanced measure even with imbalanced class distributions [9].

Zero-shot Evaluation Protocols

Zero-shot evaluation is particularly important for assessing model generalization without task-specific fine-tuning. The protocol typically involves:

- Cell Type Clustering: Applying models to unseen single-cell data and evaluating whether embeddings group cells by biological function rather than technical artifacts [10].

- Batch Effect Correction: Assessing whether models can identify biological similarities despite confounding technical variations between experiments [10].

- Comparative Baselines: Comparing against traditional methods like scVI, Harmony, and simple feature selection approaches (Highly Variable Genes) [10].

Recent evaluations of single-cell foundation models revealed significant limitations in zero-shot settings, with these models underperforming simpler traditional methods across multiple datasets [5] [10]. This highlights the importance of rigorous zero-shot benchmarking before deploying models in discovery contexts.

Parameter-Efficient Fine-tuning Techniques

Given the massive parameter counts in foundation models, full fine-tuning is often computationally prohibitive. Recent approaches employ parameter-efficient methods:

- Adapter Modules: Small bottleneck layers inserted between transformer layers that contain only 0.1% of the total model parameters [9].

- Selective Layer Tuning: Only fine-tuning specific subsets of layers, often with the best performance coming from intermediate rather than final layers [9].

- Transfer Learning Protocols: Pre-training on diverse datasets followed by task-specific adaptation, with studies showing that models trained on multispecies data often outperform those trained solely on human genomes, even for human-specific tasks [9].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biological Foundation Models

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide Transformer | Foundation Model | DNA sequence representation learning | [9] |

| scGPT | Foundation Model | Single-cell multi-omics analysis | [7] [10] |

| Geneformer | Foundation Model | Single-cell transcriptomics embedding | [10] |

| CZ CELLxGENE | Data Resource | Unified access to annotated single-cell datasets | [7] |

| Hugging Face Transformers | Software Library | Transformer model implementation and sharing | - |

| ENCODE | Data Resource | Reference epigenomics datasets for benchmarking | [9] |

| ProteinBERT | Foundation Model | Protein sequence and function modeling | [3] |

Architectural Workflow and Experimental Design

Diagram 1: Biological Foundation Model Workflow. This diagram illustrates the end-to-end pipeline for developing and applying biological foundation models, from data processing through to biological applications.

The integration of transformer architectures and attention mechanisms with biological data represents a transformative development in bioinformatics. Performance comparisons reveal a complex landscape where foundation models demonstrate impressive capabilities in specific domains—particularly DNA sequence analysis and protein structure prediction—while showing limitations in others, such as zero-shot single-cell analysis. The experimental evidence indicates that model scale, training data diversity, and appropriate fine-tuning strategies significantly impact performance, with multispecies models often outperforming specialized counterparts even on species-specific tasks. As the field matures, standardization of evaluation protocols and acknowledgment of current limitations will be crucial for responsible adoption. Future advancements will likely emerge from more biologically informed architectures, improved efficiency, and better integration of multimodal data, further solidifying the role of these paradigms in decoding biological complexity.

The pretraining and fine-tuning paradigm has emerged as a transformative framework in bioinformatics, enabling researchers to leverage large-scale biological atlases for specific analytical tasks. This approach involves first pre-training a model on vast, diverse datasets to learn fundamental biological representations, then fine-tuning it on smaller, task-specific datasets to adapt it to specialized applications [11] [12]. This paradigm is particularly valuable in fields like single-cell biology, where coordinated efforts such as CZI CELLxGENE, HuBMAP, and the Broad Institute Single Cell Portal have generated massive volumes of curated data [13]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this methodology addresses a critical challenge: extracting meaningful insights from enormous reference atlases that can exceed 1 terabyte in size using standard data structures [13]. Foundation models trained on these atlases demonstrate remarkable proficiency in managing large-scale, unlabeled datasets, which is especially valuable given that experimental procedures in biology are often costly and labor-intensive [12].

Core Concepts: Pretraining, Fine-Tuning, and Transfer Learning

Fundamental Definitions

- Pretraining: The initial phase where a model is trained on a large, general dataset to learn fundamental patterns and representations. In bioinformatics, this typically involves training on extensive biological atlases comprising diverse datasets [14].

- Fine-tuning: The subsequent process of adapting a pretrained model to a specific task using a smaller, specialized dataset. This requires far less data and computational resources compared to training a model from scratch [15].

- Transfer Learning: The broader concept of transferring knowledge from a source domain (large reference atlases) to a target domain (specific research tasks), which underpins the pretraining and fine-tuning paradigm [16] [17].

Key Distinctions

It is crucial to distinguish between continuous pretraining (further training a pretrained model on new domain-specific data) and task-specific fine-tuning (adapting a model for a particular predictive task) [14]. Continuous pretraining enhances a model's domain knowledge using unlabeled data, while fine-tuning typically employs labeled data to specialize the model for a specific task like classification or regression [14].

Methodological Approaches and Experimental Protocols

Architectural Surgery with scArches

The scArches (single-cell architectural surgery) methodology provides an advanced implementation of transfer learning for mapping query datasets onto reference atlases [16]. This approach uses transfer learning and parameter optimization to enable efficient, decentralized, iterative reference building without sharing raw data—addressing common legal restrictions on data sharing in biomedical research [16].

Experimental Protocol for scArches:

- Reference Model Training: Train a conditional variational autoencoder (CVAE) such as scVI or trVAE on multiple reference datasets, assigning categorical labels to each dataset that correspond to study-specific conditions.

- Model Sharing: Share the trained reference model weights through a model repository while maintaining data privacy.

- Query Mapping: Extend the model architecture by adding trainable "adaptors" for new query datasets rather than modifying the entire network.

- Fine-tuning: Restrict trainable parameters to a small subset of weights for query study labels, functioning as an inductive bias to prevent overfitting.

- Iterative Integration: Contextualize new datasets with existing references while preserving biological variation and removing technical batch effects [16].

Benchmarking Fine-tuning Strategies

A systematic evaluation compared three fine-tuning strategies for mapping query datasets to reference atlases using a mouse brain atlas comprising 250,000 cells from two studies [16]:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Fine-Tuning Strategies

| Fine-Tuning Strategy | Parameters Updated | Batch Effect Removal | Biological Conservation | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptors Only | Minimal (query-specific adaptors) | High | High | Excellent |

| Input Layers | Encoder/decoder input layers | Moderate | Moderate | Good |

| All Weights | Entire model | High | Low | Poor |

The adaptors-only approach, which updates the fewest parameters, demonstrated competitive performance in integrating different batches while preserving distinctions between cell types, making it particularly suitable for iterative atlas expansion [16].

Performance Comparison of Foundation Models in Bioinformatics

Model Typology and Applications

Foundation models in bioinformatics can be categorized into four main types, each with distinct strengths and applications [12]:

Table 2: Foundation Model Types and Their Bioinformatics Applications

| Model Type | Example Architectures | Bioinformatics Applications | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|

| Language FMs | DNABERT, BioBERT | Genome sequence analysis, regulatory element prediction | Captures biological "grammar" and syntax |

| Vision FMs | Cell Image Models | Cellular image analysis, morphology classification | Visual pattern recognition in biological structures |

| Graph FMs | Protein Structure Graphs | Protein-protein interactions, molecular property prediction | Represents complex relational biological data |

| Multimodal FMs | Multi-omics Integrators | Cross-modal data imputation, integrative analysis | Connects different data types (e.g., genomics + proteomics) |

Quantitative Benchmarking

In a systematic evaluation of pancreas atlas integration, scArches was compared with de novo integration methods across key performance metrics [16]:

Table 3: Performance Metrics for Pancreas Atlas Integration

| Method | Batch Effect Removal (ASW) | Biological Conservation (ARI) | Rare Cell Type Detection (ILS) | Computational Efficiency (Parameters) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scArches (trVAE) | 0.78 | 0.89 | 0.82 | ~4 orders of magnitude fewer |

| scArches (scVI) | 0.75 | 0.87 | 0.79 | ~4 orders of magnitude fewer |

| De Novo Integration | 0.81 | 0.91 | 0.85 | Full parameter set |

| Batch-Corrected PCA | 0.62 | 0.76 | 0.58 | N/A |

Notably, scArches achieved comparable integration performance to de novo methods while using approximately four orders of magnitude fewer parameters, demonstrating exceptional computational efficiency [16].

Experimental Workflows and Visualization

scArches Workflow for Atlas Integration

Pretraining and Fine-Tuning Paradigm

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The effective implementation of the pretraining and fine-tuning paradigm requires specific computational tools and resources:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Atlas-Based Analysis

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Atlases | CZI CELLxGENE, HuBMAP, Human Cell Atlas | Provide curated, large-scale single-cell data for pretraining | Public/controlled |

| Model Architectures | scVI, trVAE, scANVI, totalVI | Enable integration and analysis of single-cell data | Open source |

| Transfer Learning Frameworks | scArches, TensorFlow, Hugging Face Transformers | Facilitate model adaptation to new datasets | Open source |

| Data Formats | Zarr, Parquet, TileDB | Enable efficient storage and processing of large datasets | Open standards |

| Ontologies | Cell Ontology, MAMS | Standardize annotations and ensure interoperability | Community-driven |

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its promise, several challenges persist in applying the pretraining and fine-tuning paradigm to biological atlases. Batch effects - technical artifacts emerging from differences in data generation and processing - remain a significant concern, though methods like scArches can detect and correct these effects post hoc [13]. Metadata completeness is crucial for enabling stratified analyses and preventing misinterpretation of biological variation as technical noise [13]. As the field progresses, key priorities include developing improved compression algorithms for single-cell data, creating better subsampling approaches that preserve rare cell populations, and advancing latent space representations for more compact data representation [13].

The pretraining and fine-tuning paradigm represents a fundamental shift in how researchers can leverage large-scale biological data to address specific research questions. By enabling efficient knowledge transfer from massive reference atlases to specialized tasks, this approach accelerates discovery while maximizing the value of existing data resources. As foundation models continue to evolve in bioinformatics, their careful evaluation and application will be essential for driving innovation in basic research and drug development.

The field of bioinformatics is undergoing a transformative shift with the integration of foundation models. These advanced artificial intelligence systems are moving beyond traditional sequence analysis to tackle complex challenges in drug discovery, protein engineering, and personalized medicine. This guide provides a systematic comparison of four core model types—Language, Vision, Graph, and Multimodal—framed within the context of evaluating their performance and applicability for bioinformatics research. We synthesize the latest benchmark data and experimental protocols to offer researchers and drug development professionals a structured framework for model selection.

The table below summarizes the core characteristics, leading examples, and primary bioinformatics applications of the four model types discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Overview of Foundation Model Types in Bioinformatics

| Model Type | Core Function | Exemplary Models (2025) | Primary Bioinformatics Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Language (LLM) | Process, understand, and generate human and machine languages. | GPT-5, Claude 4.5 Sonnet, Llama 4 Scout, DeepSeek-R1 [18] [19] [20] | Scientific literature mining, genomic sequence analysis, automated hypothesis generation. |

| Vision (VLM) | Interpret and reason about visual and textual data. | Gemini 2.5 Pro, InternVL3-78B, FastVLM [21] [22] | Medical image analysis (e.g., histology, radiology), microscopy image interpretation, structural biology. |

| Graph (GNN) | Learn from data structured as graphs (entities and relationships). | GraphSAGE, GraphCast, GNoME [23] | Molecular property prediction, drug-target interaction networks, protein-protein interaction networks. |

| Multimodal | Process and integrate multiple data types (e.g., text, image, audio). | GPT-4o, Gemini 2.5 Pro, Claude 4.5 [21] [19] | Integrated analysis (e.g., combining medical images with clinical notes), multi-omics data fusion. |

Performance Benchmarking and Quantitative Comparison

To objectively compare model capabilities, we present results from standardized benchmarks that are relevant to scientific reasoning and problem-solving.

General Reasoning and Knowledge Benchmarks

The following table consolidates performance data from several key benchmarks that test broad knowledge and reasoning abilities, which are foundational for scientific tasks.

Table 2: Performance on General Capability Benchmarks (Percentage Scores) [18]

| Model | GPQA Diamond (Reasoning) | AIME 2025 (High School Math) | Humanity's Last Exam (Overall) | MMMLU (Multilingual Reasoning) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gemini 3 Pro | 91.9 | 100.0 | 45.8 | 91.8 |

| GPT-5.1 | 88.1 | - | - | - |

| Claude Opus 4.5 | 87.0 | - | 35.2 | 90.8 |

| Grok 4 | 87.5 | - | 25.4 | - |

| Kimi K2 Thinking | - | 99.1 | 44.9 | - |

Specialized and Efficiency Benchmarks

For research environments, specialized task performance and computational efficiency are critical. The table below highlights performance on agentic coding and visual reasoning, alongside key efficiency metrics.

Table 3: Performance on Specialized Tasks and Efficiency Metrics [18] [21]

| Model | SWE-Bench (Agentic Coding) | ARC-AGI 2 (Visual Reasoning) | Latency (TTFT in seconds) | Cost (USD per 1M output tokens) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Claude Sonnet 4.5 | 82.0 | - | ~0.3 | $15.00 |

| Claude Opus 4.5 | 80.9 | 37.8 | ~0.5 | $25.00 |

| GPT-5.1 | 76.3 | 18.0 | - | $10.00 |

| Gemini 3 Pro | 76.2 | 31.0 | ~0.3 | $12.00 |

| Llama 4 Scout | - | - | 0.33 | $0.34 |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking

Understanding the methodology behind these benchmarks is essential for their critical appraisal and application to specific bioinformatics use cases.

Protocol for AesBiasBench: Evaluating Bias in Multimodal Models

This protocol is designed to assess stereotype bias and human alignment in multimodal models, which is crucial for ensuring fairness in biomedical applications [24].

- Task Design: Models are evaluated across three subtasks:

- Aesthetic Perception: The model describes the aesthetic qualities of an image.

- Aesthetic Assessment: The model provides a quantitative or qualitative rating of an image's aesthetics.

- Aesthetic Empathy: The model predicts the emotional response a human might have to an image.

- Demographic Incorporation: To measure bias, demographic factors (e.g., gender, age, education) of the hypothetical image creator or viewer are systematically incorporated into the prompts.

- Metric Calculation:

- Stereotype Bias: Quantified using metrics like IFD (Identity-Flipped Discrepancy) and NRD (Non-Identity Relative Discrepancy), which measure variation in model outputs across demographic groups.

- Human Alignment: Measured using the AAS (Aesthetic Alignment Score) to quantify the concordance between model outputs and genuine human preferences from curated datasets.

- Model Comparison: The protocol evaluates a wide range of proprietary and open-source models (e.g., GPT-4o, Claude-3.5-Sonnet, InternVL-2.5) to compare their susceptibility to bias.

Protocol for Circuit Tracing in Language Models

This method from mechanistic interpretability research aims to uncover the internal "circuits" a model uses to produce an output, which can help verify the scientific soundness of a model's reasoning [25].

- Replacement Model Construction: A trained Cross-Layer Transcoder (CLT), which is an interpretable component, is substituted for the multi-layer perceptrons (MLPs) in the original model. This CLT is designed to approximate the original model's outputs while using sparse, human-interpretable features.

- Attribution Graph Generation: For a specific input prompt, an "attribution graph" is produced. This graph describes the sequence of computational steps (active features and their linear effects) the replacement model used to generate the target output.

- Graph Pruning: The graph is pruned to retain only the nodes and edges that most contributed to the final output, creating a sparse, interpretable representation of the model's internal process.

- Validation via Perturbation: The discovered circuits are validated by perturbing the model's activations in the direction of key features and observing if the resulting changes in other features and the final output are consistent with the attribution graph.

Visualizing Model Architectures and Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate key architectural concepts and experimental workflows described in this guide.

Vision Language Model (VLM) High-Level Architecture

Diagram 1: Standard VLM architecture with a vision encoder and LLM.

Graph Neural Network (GNN) Message Passing

Diagram 2: GNN message-passing mechanism for learning node representations.

AesBiasBench Experimental Workflow

Diagram 3: AesBiasBench workflow for evaluating bias and alignment.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

This section details essential "research reagents" – in this context, key software tools, benchmarks, and datasets – required for conducting rigorous evaluations of foundation models in a bioinformatics context.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Model Evaluation

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Evaluation |

|---|---|---|

| AesBiasBench [24] | Benchmark | Systematically evaluates stereotype bias and human alignment in multimodal models for subjective tasks. |

| GPQA Diamond [18] | Benchmark | A high-quality, difficult question-answering dataset requiring advanced reasoning, used to test expert-level knowledge. |

| SWE-Bench [18] | Benchmark | Evaluates models' ability to solve real-world software engineering issues, analogous to troubleshooting complex analysis pipelines. |

| Cross-Layer Transcoder (CLT) [25] | Methodological Tool | A key component in circuit tracing, used to create an interpretable replacement model for mechanistic analysis. |

| Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) [25] | Methodological Tool | Used to extract interpretable features from model activations, which serve as building blocks for understanding model circuits. |

| FastViTHD [22] | Model Component | A hybrid convolutional-transformer vision encoder optimized for high-resolution image processing in VLMs, improving efficiency and accuracy. |

In the era of data-driven biology, molecular, cellular, and textual repositories have become indispensable infrastructure supporting groundbreaking research from basic science to drug development. These resources provide the organized, accessible data essential for training and evaluating the foundation models that are revolutionizing bioinformatics. The evolution of biological data resources spans a hierarchy of sophistication—from simple archives of raw data to advanced information systems that integrate and analyze information across multiple sources [26]. As single-cell foundation models (scFMs) and large language models (LLMs) transform our ability to interpret complex biological systems, the quality and comprehensiveness of these underlying data repositories directly determine research outcomes [27] [28]. This guide provides an objective comparison of repository types and their experimental applications, offering researchers a framework for selecting appropriate resources based on specific research needs and contexts.

Repository Taxonomy and Functional Hierarchy

Biological data resources vary considerably in complexity, functionality, and maintenance requirements. Understanding these categories enables researchers to select appropriate resources for their specific applications, from simple data storage to complex analytical tasks.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Biological Data Resources

| Category | Complexity | Content & Metadata | Search & Retrieval | Data Mining Capabilities | Primary Audience |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archives | Low | Raw data with little or no metadata | Not indexed; cumbersome searching | Very difficult | Single lab or institution |

| Repositories | Medium | Primary data with some metadata | Indexed data facilitating basic searches | Limited to basic statistics | Collaborative/Public access |

| "Databases" | High | Extensively curated metadata | Search driven by database system | Built-in analysis and report tools | Single lab, organization, or public |

| Advanced Information Systems (AIS) | Very High | Curated metadata integrated with external resources | Efficient search and retrieval | Customizable tools for user data analysis | Organization or public |

The distinctions between these categories are fluid, with many resources exhibiting hybrid characteristics. For instance, the Protein Data Bank (PDB) primarily functions as a repository but incorporates database-like features such as advanced search capabilities based on experimental details [26]. True Advanced Information Systems remain aspirational for most biological domains, though resources like UniProt and the PDB are evolving toward this comprehensive "hub" model by integrating increasingly sophisticated analytical tools and cross-references to external data sources [26] [29].

Figure 1: Data Resource Evolution Pathway. The diagram illustrates the hierarchical relationship between data resource types, showing how functionality increases with additional layers of structure, validation, and integration.

Experimental Benchmarking of Repository-Driven Foundation Models

Benchmarking Methodology for Single-Cell Foundation Models

The evaluation of repository-dependent foundation models requires rigorous benchmarking frameworks that assess performance across multiple dimensions. A comprehensive benchmark for single-cell foundation models (scFMs) should encompass two gene-level and four cell-level tasks evaluated across diverse datasets representing various biological conditions and clinical scenarios [27]. Performance should be measured using multiple metrics (typically 12 or more) spanning unsupervised, supervised, and knowledge-based approaches [27].

A critical methodological consideration is the implementation of zero-shot evaluation protocols, which assess the intrinsic quality of learned representations without task-specific fine-tuning [27]. This approach tests the fundamental biological knowledge captured during pretraining on repository data. Additionally, ontology-informed metrics such as scGraph-OntoRWR (which measures consistency of cell type relationships with prior biological knowledge) and Lowest Common Ancestor Distance (LCAD, which measures ontological proximity between misclassified cell types) provide biologically meaningful assessment beyond technical performance [27].

To mitigate data leakage concerns, benchmarks should incorporate independent validation datasets not used during model training, such as the Asian Immune Diversity Atlas (AIDA) v2 from CellxGene [27]. Performance should be evaluated across challenging real-world scenarios including novel cell type identification, cross-tissue homogeneity, and intra-tumor heterogeneity [27].

Performance Comparison of Single-Cell Foundation Models

Experimental benchmarking of leading scFMs reveals distinct performance profiles across different task types. The following table summarizes quantitative results from comprehensive evaluations:

Table 2: Single-Cell Foundation Model Performance Comparison

| Model Name | Parameters | Pretraining Dataset Scale | Gene Embedding Strategy | Top-performing Tasks | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geneformer [27] | 40M | 30 million cells | Lookup Table | Cell type annotation, Network analysis | Limited to scRNA-seq data |

| scGPT [27] | 50M | 33 million cells | Lookup Table + Value binning | Multi-omics integration, Batch correction | Computationally intensive |

| UCE [27] | 650M | 36 million cells | Protein embedding from ESM-2 | Cross-species transfer learning | Complex embedding scheme |

| scFoundation [27] | 100M | 50 million cells | Lookup Table + Value projection | Large-scale pattern recognition | High memory requirements |

| LangCell [27] | 40M | 27.5 million cell-text pairs | Lookup Table | Text-integration tasks | Requires curated text labels |

| scCello [27] | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing | Developmental trajectory inference | Specialized scope |

Notably, benchmarking results demonstrate that no single scFM consistently outperforms others across all tasks, emphasizing the need for task-specific model selection [27]. Simple machine learning models sometimes outperform complex foundation models, particularly in dataset-specific applications with limited resources [27]. The roughness index (ROGI), which measures landscape complexity in latent space, can serve as a proxy for model selection in dataset-dependent applications [27].

Figure 2: Single-Cell Foundation Model Workflow. The diagram illustrates the standard processing pipeline for scFMs, from raw repository data through tokenization, model architecture, pretraining, and application to downstream tasks.

Specialized Repository Types and Their Research Applications

Molecular and Cellular Data Repositories

Molecular and cellular repositories provide the essential data infrastructure for foundational research in bioinformatics and systems biology. These resources vary in scope from comprehensive genomic databases to specialized collections focusing on specific biological entities or processes.

Table 3: Specialized Biological Data Repositories

| Repository Name | Primary Content | Data Types | Key Features | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STRING [30] | Protein-protein associations | Functional, physical, and regulatory networks | Confidence scoring, Cross-species transfer, Network clustering | Pathway analysis, Functional annotation, Network medicine |

| CellFinder [31] | Mammalian cell characterization | 3,394 cell types, 50,951 cell lines, Images, Expression data | Ontology-based integration, Developmental trees, Body browser | Cell type identification, Developmental biology, Disease modeling |

| GravyTrain [32] | Yeast genetic constructs | Gene deletion and tagging constructs | Modular cloning scheme, Restriction-free shuffling | Molecular cell biology, Autophagy studies, Genomic modifications |

| BRENDA [29] | Enzyme information | Functional parameters, Organism data, Reaction specifics | Comprehensive coverage, Kinetic data, Taxonomic classification | Metabolic engineering, Enzyme discovery, Biochemical research |

| UniProt [29] | Protein sequences and functional information | Sequences, Functional annotations, Structural data | Manual curation, Comparative analysis, Disease associations | Protein function prediction, Phylogenetics, Drug target identification |

| ENA/GenBank/DDBJ [29] | Nucleotide sequences | Raw sequences, Assemblies, Annotations | International collaboration, Standardized formats, Cross-references | Genomic analysis, Comparative genomics, Phylogenetic studies |

Protocol: Utilizing STRING Database for Protein Network Analysis

The STRING database exemplifies how integrated repositories enable sophisticated biological analyses. Below is a detailed protocol for employing STRING in protein network analysis:

Experimental Objective: To identify and characterize functional association networks for a set of proteins of interest using evidence-integration approaches.

Methodology:

- Input Preparation: Compile a list of protein identifiers (genes, UniProt IDs, or amino acid sequences) for proteins of interest.

- Network Retrieval: Access the STRING database (https://string-db.org/) and input target proteins, selecting the appropriate organism and required confidence score threshold (default: 0.70).

- Evidence Channel Configuration: Enable/disable specific evidence channels based on research needs: genomic context (neighborhood, fusion, co-occurrence), co-expression, experimental data, curated databases, and text mining [30].

- Network Type Selection: Choose between functional, physical, or regulatory network modes based on research questions [30].

- Analysis Execution:

- Apply hierarchical clustering to identify functional modules within the network.

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis using STRING's precomputed functional modules or external ontologies.

- For regulatory networks, examine interaction directionality extracted through fine-tuned language models [30].

- Result Interpretation:

- Examine confidence scores representing estimated likelihood of associations.

- Review evidence viewers for underlying support of specific interactions.

- Export network embeddings for machine learning applications [30].

Technical Considerations: The confidence scoring system integrates evidence from multiple channels probabilistically, assuming channel independence [30]. For physical interactions, dedicated language models detect supporting evidence in literature [30]. Cross-species transfers use interolog predictions based on evolutionary relationships [30].

Research Reagent Solutions for Repository-Driven Science

The effective utilization of biological repositories requires both computational tools and experimental reagents designed for systematic biological investigation.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Name | Type | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GravyTrain Toolbox [32] | Molecular constructs | Genomic modifications in yeast | Yeast genetics, Molecular cell biology | Modular cloning, Restriction-free shuffling, Comprehensive tag collection |

| pYM Plasmid Library [32] | Molecular biology | Genomic modification in yeast | Protein tagging, Gene deletion | Standardized S1/S2/S3/S4 adapters, Homology-based integration |

| AID* Tag [32] | Degradation tag | Auxin-induced protein degradation | Protein function analysis | Transient, quantitative depletion, SCFTIR1-mediated ubiquitination |

| TurboID [32] | Proximity labeling | Identification of protein interactions | Interactome mapping | proximity-based biotinylation, Mass spectrometry analysis |

| TAP Tag [32] | Affinity tag | Protein purification and detection | Protein characterization | Tandem affinity purification, Multiple detection modalities |

| scFMs (Geneformer, scGPT, etc.) [27] [28] | Computational models | Single-cell data analysis | Cellular heterogeneity studies, Drug response prediction | Transfer learning, Zero-shot capability, Multi-task adaptation |

Molecular, cellular, and textual repositories form the essential foundation upon which modern bioinformatics research is built. As foundation models become increasingly central to biological discovery, the symbiotic relationship between curated data resources and analytical algorithms will continue to intensify. The experimental comparisons presented in this guide demonstrate that repository selection directly influences research outcomes, with different resource types offering complementary strengths and limitations. Future developments will likely focus on enhancing repository interoperability, improving metadata standards, and developing more sophisticated benchmarking frameworks that better capture biological plausibility beyond technical performance metrics. Researchers are advised to maintain current knowledge of evolving repository capabilities and to select resources based on both current needs and anticipated future requirements as the field of data-driven biology continues to mature.

From Sequence to Function: Methodological Advances and Domain-Specific Applications

Tokenization, the process of converting raw biological data into discrete computational units, serves as the foundational step for applying deep learning in bioinformatics. The performance of foundation models on tasks ranging from gene annotation to protein structure prediction is profoundly influenced by the chosen tokenization strategy. Unlike natural language, biological sequences and structures lack inherent delimiters like spaces or punctuation, making the development of effective tokenization methods a significant research challenge [33] [34]. Current approaches have evolved beyond naive character-level tokenization to include sophisticated data-driven methods that capture biologically meaningful patterns, though significant work remains in developing techniques that fully encapsulate the complex semantics of biological data [34] [35]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of tokenization strategies across genomic, protein, and single-cell modalities, offering experimental data and methodologies to inform researchers and drug development professionals in selecting optimal approaches for their specific applications.

Tokenization Approaches Across Biological Modalities

Genomic Sequence Tokenization

Genomic tokenization strategies have evolved from simple nucleotide-based approaches to more sophisticated methods that capture biological context. The table below compares the primary tokenization methods used for DNA sequence analysis:

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Genomic Tokenization Strategies

| Tokenization Method | Vocabulary Size | Sequence Length Reduction | Biological Interpretability | Key Applications | Notable Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleotide (Character-level) | 4-5 tokens (A,C,G,T,N) | None (1:1 mapping) | Low | Basic sequence analysis | Enformer, HyenaDNA |

| Fixed k-mer | 4k tokens | ~k-fold reduction | Medium (captures motifs) | Sequence classification | DNABERT, Nucleotide Transformer |

| Overlapping k-mer | 4k tokens | Minimal reduction | High (preserves context) | Regulatory element prediction | DNABERT, SpliceBERT |

| Data-driven (BPE/WordPiece) | Configurable (typically 512-4096) | 2-4 fold reduction | Variable (learned patterns) | General-purpose genomics | DNABERT-2 |

| Codon-based | 64 tokens (sense codons) | 3-fold reduction | High (biological relevance) | Coding sequence analysis | GenSLM |

Fixed k-mer tokenization, which breaks sequences into contiguous segments of k nucleotides, provides a balance between vocabulary size and biological meaning, with 6-mers being a popular choice as they approximate transcription factor binding site lengths [34]. Overlapping k-mers, as implemented in DNABERT, extend this approach by creating sliding windows across sequences, preserving contextual information crucial for tasks like splice site prediction [34]. More advanced data-driven approaches like Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) and WordPiece adapt to specific datasets by iteratively merging frequent nucleotide pairs, resulting in vocabulary items of varying lengths that capture repetitive elements and common motifs [33] [36]. Experimental evidence demonstrates that applying these alternative tokenization algorithms can increase model accuracy while substantially reducing input sequence length compared to character-level tokenization [33].

Protein Representation Tokenization

Protein tokenization encompasses both sequence-based and structure-based approaches, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 2: Protein Tokenization Methods and Performance Characteristics

| Tokenization Method | Input Modality | Vocabulary Size | Reconstruction Accuracy | Information Retention | Representative Models |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid (Residue-level) | Sequence | 20-25 tokens (standard aa + special) | N/A | High sequential information | ESM, ProtTrans |

| Subword BPE | Sequence | Configurable (256-1024) | N/A | Medium-High (balances granularity & context) | ESM-2, ProGen |

| VQ-VAE Structure Tokens | 3D Structure | 512-4096 tokens | 1-2 Å RMSD | High local structural information | ESM3, AminoAseed |

| Inverse Folding-based | 3D Structure | 20-64 tokens | Variable | High sequence-structure relationship | ProteinMPNN |

| All-Atom Vocabulary | 3D Structure | 1024+ tokens | <2 Å scale accuracy | Comprehensive structural details | CHEAP |

For protein sequences, subword tokenization methods like Byte-Pair Encoding (BPE) have demonstrated effectiveness by creating meaningful fragments that capture conserved domains and motifs [33]. For structural representation, Vector Quantized Variational Autoencoders (VQ-VAEs) have emerged as powerful approaches, compressing local 3D structures into discrete tokens via a learnable codebook [37] [38]. The StructTokenBench framework provides comprehensive evaluation of these methods, revealing that Inverse-Folding-based tokenizers excel in downstream effectiveness while methods like ProTokens achieve superior sensitivity in capturing structural variations [37]. Recent innovations like the AminoAseed tokenizer address critical challenges like codebook under-utilization (a problem where up to 70% of codes in ESM3 remain inactive), achieving a 124.03% improvement in codebook utilization rate and 6.31% average performance gain across 24 supervised tasks compared to ESM3 [37] [38].

Single-Cell Data Tokenization

Single-cell foundation models (scFMs) employ distinct tokenization strategies to represent gene expression profiles:

Table 3: Tokenization Approaches in Single-Cell Foundation Models

| Model | Tokenization Strategy | Gene Ordering | Value Representation | Positional Encoding | Pretraining Data Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geneformer | Rank-based (top 2,048 genes) | Expression magnitude | Order as value embedding | Standard transformer | 30 million cells |

| scGPT | HVG-based (top 1,200 genes) | Not ordered | Value binning | Not used | 33 million cells |

| scBERT | Bin-based expression | Expression categories | Binned expression | Standard transformer | 10+ million cells |

| UCE | Non-unique sampling | Genomic position | Expression threshold | Genomic position | 36 million cells |

| scFoundation | Comprehensive (all ~19k genes) | Not ordered | Value projection | Not used | 50 million cells |

A fundamental challenge in single-cell tokenization is that gene expression data lacks natural ordering, unlike sequential language data [28] [27]. To address this, models employ various gene ordering strategies, with expression-level ranking being particularly common. In this approach, genes are sorted by expression magnitude within each cell, creating a deterministic sequence for transformer processing [28]. Alternative strategies include genomic position ordering (leveraging the physical arrangement of genes on chromosomes) and value-based binning (categorizing expression levels) [27]. Benchmark studies reveal that no single scFM consistently outperforms others across all tasks, emphasizing the need for tokenization selection tailored to specific applications like cell type annotation versus drug response prediction [27].

Experimental Protocols and Performance Benchmarks

Evaluation Framework for Biological Tokenizers

Rigorous evaluation frameworks are essential for comparing tokenization strategies. The StructTokenBench framework for protein structure tokenizers assesses four key perspectives:

- Downstream Effectiveness: Performance on supervised tasks like function prediction and stability assessment

- Sensitivity: Ability to detect subtle structural variations

- Distinctiveness: Capacity to generate diverse representations for different structures

- Codebook Utilization Efficiency: Proportion of actively used tokens in the vocabulary [37] [38]

For genomic tokenizers, standard evaluation protocols involve measuring performance on tasks including protein function prediction, protein stability assessment, nucleotide sequence alignment, and protein family classification [33]. Single-cell tokenizers are typically assessed through cell type annotation accuracy, batch integration effectiveness, and drug sensitivity prediction [27].

Diagram 1: Protein Structure Tokenization Evaluation Workflow

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Experimental results provide critical insights into tokenizer performance across biological domains:

Table 4: Experimental Results for Different Tokenization Strategies

| Tokenization Method | Task | Performance Metric | Result | Sequence Length Reduction | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPE (Biological) | Protein Function Prediction | Accuracy | +5.8% vs baseline | 3.2x reduction | Captures functional domains effectively [33] |

| AminoAseed (VQ-VAE) | 24 Supervised Protein Tasks | Average Performance | +6.31% vs ESM3 | N/A | 124.03% higher codebook utilization [37] |

| DNABERT-2 (BPE) | Genome Annotation | F1 Score | 0.89 | 3-4x reduction | Outforms overlapping k-mer on regulatory tasks [34] |

| Overlapping k-mer (DNABERT) | Splice Site Prediction | Accuracy | 0.94 | Minimal reduction | Excellent for precise boundary detection [34] |

| scGPT (Value Binning) | Cell Type Annotation | Accuracy | 0.87 (zero-shot) | N/A | Robust across tissue types [27] |

| Inter-Chrom (Dynamic) | Chromatin Interaction | AUROC | 0.92 | Configurable | Superior to SPEID, PEP [36] |

For genomic tasks, data-driven tokenizers like BPE demonstrate significant advantages. On eight different biological tasks, alternative tokenization algorithms increased accuracy while achieving a 3-fold decrease in token sequence length when trained on large-scale datasets containing over 400 billion amino acids [33]. The dynamic tokenization approach in Inter-Chrom, which extracts top-k words based on length and frequency for both DNA strands, outperformed existing methods for chromatin interaction prediction by effectively capturing both ubiquitous features and unique sequence specificity [36].

Implementation Guide: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of biological tokenization strategies requires specific computational tools and resources:

Table 5: Essential Research Reagents for Biological Tokenization

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Primary Function | Application Context | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SentencePiece | Software Library | Unsupervised tokenization | DNA sequence tokenization | Open source |

| Hugging Face Tokenizers | Software Library | BPE, WordPiece implementation | General biological sequences | Open source |

| StructTokenBench | Evaluation Framework | Protein tokenizer benchmarking | Comparative analysis | GitHub |

| BiologicalTokenizers | Trained Models | Pre-trained biological tokenizers | Transfer learning | GitHub [33] |

| ESMFold | Protein Language Model | Structure embedding source | CHEAP embeddings | Academic license |

| CHEAP Embeddings | Compressed Representation | Joint sequence-structure tokens | Multi-modal protein analysis | Upon request [39] |

| scGPT | Single-Cell Foundation Model | Gene expression tokenization | Cell-level analysis | GitHub |

| DNABERT | Genomic Language Model | k-mer-based tokenization | DNA sequence analysis | GitHub |

Tokenization strategies represent a critical frontier in bioinformatics foundation models, with significant implications for model performance, computational efficiency, and biological interpretability. Current evidence suggests that data-driven approaches like BPE and VQ-VAE generally outperform fixed strategies across diverse biological tasks, offering better sequence compression while maintaining or enhancing predictive accuracy [33] [37]. However, the optimal tokenization strategy remains highly context-dependent, with factors including data type (sequence vs. structure), task requirements (classification vs. generation), and computational constraints influencing selection.

Future developments will likely focus on multi-modal tokenization that jointly represents sequence, structure, and functional annotations [39], improved codebook utilization in VQ-VAE approaches [37], and biologically constrained tokenization that incorporates prior knowledge about molecular interactions and pathways. As the field matures, standardized evaluation frameworks like StructTokenBench will become increasingly important for objective comparison and strategic development of tokenization methods that fully leverage the complex, hierarchical nature of biological systems.

Single-cell foundation models (scFMs) represent a transformative paradigm in computational biology, leveraging large-scale deep learning to interpret the complex language of cellular function. Defined as large-scale models pretrained on vast and diverse single-cell datasets, scFMs utilize self-supervised learning to develop a fundamental understanding of gene relationships and cellular states that can be adapted to numerous downstream biological tasks [28]. The rapid accumulation of public single-cell data—with archives like CZ CELLxGENE now providing access to over 100 million unique cells—has created the essential training corpus for these models [28]. Inspired by the success of transformer architectures in natural language processing, researchers have begun developing scFMs that treat individual cells as "sentences" and genes as "words," enabling the models to learn the syntactic and semantic rules governing cellular identity and function [28].

This comparison guide examines the current landscape of scFMs within the broader context of evaluating foundation models in bioinformatics research. As the field experiences rapid growth with numerous models being developed, a critical crisis of fragmentation has emerged—dozens of models with similar capabilities but unclear differentiation [40]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals navigating this complex ecosystem, understanding the relative strengths, limitations, and appropriate applications of available scFMs becomes essential for advancing biological discovery and translational applications.

Comparative Performance Evaluation of Leading scFMs

Evaluation Methodology and Benchmarking Frameworks

Comprehensive benchmarking studies have employed rigorous methodologies to evaluate scFM performance across diverse biological tasks. The most robust evaluations assess models in zero-shot settings (without task-specific fine-tuning) to genuinely measure their foundational biological understanding [27] [10]. Benchmarking frameworks typically evaluate performance across multiple task categories:

- Gene-level tasks: Gene function prediction, gene-gene relationship modeling

- Cell-level tasks: Cell type annotation, batch integration, clustering

- Clinical prediction tasks: Drug sensitivity prediction, cancer cell identification

These evaluations employ a range of metrics including traditional clustering metrics, novel biological relevance metrics like scGraph-OntoRWR (which measures consistency of cell type relationships with biological knowledge), and LCAD (Lowest Common Ancestor Distance) which quantifies the severity of cell type misannotation errors [27]. Performance is typically compared against traditional bioinformatics methods like Seurat, Harmony, and scVI to determine whether the complexity of scFMs provides tangible benefits [27].

Performance Across Biological Tasks

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Major scFMs Across Task Categories

| Model | Pretraining Data | Architecture | Cell Type Annotation | Batch Integration | Perturbation Prediction | Gene Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scGPT | 33M cells [27] | Transformer Decoder [28] | Strong [41] | Robust [42] | Strong [42] | Excellent [41] |

| Geneformer | 30M cells [27] | Transformer Encoder [28] | Moderate [10] | Variable [5] | Strong [43] | Excellent [41] |

| scFoundation | 50M cells [27] | Asymmetric Encoder-Decoder [27] | Moderate [27] | Moderate [27] | Good [27] | Strong [41] |

| UCE | 36M cells [27] | Transformer Encoder [27] | Moderate [27] | Moderate [27] | Not Reported | Strong [27] |

| scBERT | Not Specified | Transformer Encoder [28] | Limited [41] | Limited [41] | Limited [41] | Limited [41] |

| Traditional Methods (Seurat, Harmony, scVI) | N/A | N/A | Variable [10] | Strong [10] | Specialized Approaches Required | Limited Capabilities |

Table 2: Computational Requirements and Specialized Capabilities

| Model | Parameters | Hardware Requirements | Multimodal Support | Spatial Transcriptomics | Cross-Species |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scGPT | 50M [27] | High GPU memory [42] | scATAC-seq, CITE-seq [28] | Supported [28] | Limited reporting |

| Geneformer | 40M [27] | Moderate GPU [10] | scRNA-seq only [27] | Not native | Limited reporting |

| scFoundation | 100M [27] | High GPU memory [27] | scRNA-seq focus [27] | Limited reporting | Limited reporting |

| UCE | 650M [27] | Very High GPU memory [27] | scRNA-seq only [27] | Not reported | Not reported |

| scPlantFormer | Not specified | Moderate [42] | Plant omics [42] | Limited reporting | Excellent [42] |

| Nicheformer | Not specified | Very High [42] | Spatial focus [42] | Specialized [42] | Limited reporting |

Independent benchmarking reveals that no single scFM consistently outperforms all others across diverse tasks [27]. scGPT demonstrates robust performance across most applications, particularly excelling in cell type annotation and perturbation response prediction [41] [42]. Geneformer and scFoundation show particular strength in gene-level tasks, benefiting from their effective pretraining strategies [41]. However, evaluations have uncovered a significant limitation: in zero-shot settings, many scFMs underperform compared to traditional methods like scVI or even simple highly variable genes selection [5] [10].

Experimental Protocols for scFM Evaluation

For researchers seeking to reproduce or extend these evaluations, the following experimental protocols are essential:

Zero-Shot Cell Type Annotation Protocol:

- Embedding Extraction: Process query cells through scFM without fine-tuning to obtain latent embeddings [10]

- Clustering: Apply standard clustering algorithms (e.g., Louvain, Leiden) to embeddings

- Label Transfer: Map clusters to reference cell types using marker genes or automated annotation tools

- Evaluation: Calculate metrics comparing to ground truth labels, with special attention to biological plausibility of errors using LCAD [27]

Batch Integration Assessment:

- Dataset Selection: Curate datasets with known batch effects and biological ground truth [10]

- Embedding Generation: Process batched data through scFM to obtain integrated embeddings

- Batch Mixing Assessment: Quantify with metrics like ASW (average silhouette width) for batch versus biological grouping

- Biological Preservation: Evaluate conservation of known biological cell groups post-integration

Gene Function Prediction Evaluation:

- Masking Strategy: Mask specific gene expressions in input data

- Prediction: Recover masked values using model's understanding of gene relationships [10]

- Validation: Compare predictions to held-out true values and known biological pathways

Technical Architectures and Implementation Considerations

Model Architectures and Training Approaches

scFMs predominantly utilize transformer architectures, but with significant variations in implementation:

Tokenization Strategies:

- Gene Ranking: Many models (Geneformer, LangCell) rank genes by expression level to create ordered sequences from inherently non-sequential data [28] [27]

- Value Binning: scGPT discretizes expression values into bins, combining gene identity and expression level information [27]

- Protein Embeddings: UCE incorporates protein sequence information via ESM-2 embeddings, connecting transcriptomics with proteomics [27]

Architectural Variations:

- Encoder Models (e.g., Geneformer): Use bidirectional attention, ideal for classification tasks and embedding generation [28]

- Decoder Models (e.g., scGPT): Employ masked self-attention, better suited for generative tasks [28]

- Hybrid Architectures: Newer models explore encoder-decoder combinations for enhanced flexibility [28]

Pretraining Objectives:

- Masked Gene Modeling: Most models predict masked/hidden genes based on context, analogous to masked language modeling in NLP [28]

- Multi-task Learning: Advanced models incorporate additional objectives like cell state prediction and contrastive learning [42]

scFM Architecture Workflow

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for scFM Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Datasets | Function/Purpose | Access Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | CZ CELLxGENE [28], Human Cell Atlas [28], PanglaoDB [28] | Provide standardized single-cell datasets for training and benchmarking | Public access with standardized annotation formats |

| Pretrained Models | scGPT, Geneformer, scFoundation [41] | Enable transfer learning without costly pretraining | Varied licensing; some models not publicly available [5] |

| Evaluation Frameworks | BioLLM [41], scGraph-OntoRWR [27] | Standardized benchmarking and biological relevance assessment | Open-source frameworks emerging |

| Computational Infrastructure | GPUs ( NVIDIA A100/H100), High-Memory Servers | Handle large model parameters and massive single-cell datasets | Significant resource requirements for full model training |