Flux Balance Analysis in Metabolic Engineering: Current Methods, AI Integration, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the evolving role of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) in metabolic engineering.

Flux Balance Analysis in Metabolic Engineering: Current Methods, AI Integration, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the evolving role of Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) in metabolic engineering. It explores foundational principles, details advanced methodologies like topology-informed frameworks and machine learning integration, and addresses key challenges in model prediction accuracy and computational efficiency. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes current validation studies and comparative analyses, highlighting FBA's growing impact on therapeutic discovery, sustainable biochemical production, and personalized medicine.

Understanding Flux Balance Analysis: Core Principles and Evolving Capabilities in Systems Biology

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) is a mathematical approach for analyzing metabolic networks that predicts the flow of metabolites through a biological system. As a constraint-based modeling technique, FBA operates under the core assumption of steady-state conditions, where metabolite concentrations remain constant over time as production and consumption rates balance. This framework enables the prediction of optimal metabolic flux distributions that align with specific cellular objectives, such as biomass production or metabolite synthesis, without requiring detailed kinetic parameter information. FBA has become an indispensable tool in metabolic engineering and systems biology, facilitating the in-silico prediction of cellular behavior under various genetic and environmental perturbations [1] [2].

Core Principles of Constraint-Based Modeling

Constraint-based modeling, and FBA specifically, provides a computational framework for analyzing metabolic capabilities at systems level. The methodology is built upon several foundational principles that enable quantitative predictions of metabolic behavior.

Mathematical Framework and Steady-State Assumption

The mathematical foundation of FBA represents the metabolic network as a stoichiometric matrix S with m metabolites and n reactions. The steady-state assumption is formalized as Sv = 0, where v is a flux vector containing flux values for each reaction. This equation represents the mass balance constraint ensuring that total input flux equals total output flux for each metabolite, maintaining constant concentrations over time [1].

- Stoichiometric Matrix: Encodes the stoichiometry of all biochemical reactions in the network

- Flux Vector: Represents reaction rates in the network

- Mass Balance: Ensures metabolic homeostasis under steady-state conditions

Additional physiological constraints are incorporated as flux bounds αi ≤ vi ≤ βi for each reaction i, representing biochemical and thermodynamic limitations [1].

Comparative Analysis of Metabolic Modeling Approaches

FBA occupies a middle ground between highly detailed kinetic modeling and minimal structural analysis, offering a balance of coverage and practical parameter requirements.

Table 1: Comparison of Metabolic Modeling Approaches

| Model Type | Data Requirements | Solution Characteristics | Network Coverage | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Models | Extensive kinetic parameters, enzyme mechanisms, initial concentrations | Unique dynamic solutions approaching equilibrium | Small to medium-scale pathways | Detailed mechanistic studies of central metabolism [3] |

| Flux Balance Analysis | Stoichiometry, reaction reversibility, flux constraints | Continuous space of steady-state flux solutions | Genome-scale | Metabolic engineering, phenotype prediction, strain design [1] [2] |

| Pathway Analysis | Stoichiometry only | Extreme pathways, elementary modes | Genome-scale | Network redundancy analysis, pathway identification |

The key advantage of FBA is its ability to analyze genome-scale networks with minimal parameter requirements, focusing instead on stoichiometric constraints and optimization principles. This contrasts with dynamic models that require detailed kinetic information but provide more mechanistic insights into transient behaviors [3].

Fundamental Protocols for Flux Balance Analysis

Standard FBA Implementation Workflow

The following protocol outlines the core steps for implementing FBA to predict metabolic flux distributions:

Step 1: Network Reconstruction and Stoichiometric Matrix Formation

- Compile all metabolic reactions from genomic annotation and biochemical databases

- Represent the network as stoichiometric matrix S where rows correspond to metabolites and columns represent reactions

- Define system boundaries by identifying exchange reactions with the extracellular environment

Step 2: Application of Physiochemical Constraints

- Apply steady-state constraint: Sv = 0

- Set flux bounds based on:

- Reaction reversibility (irreversible reactions: vi ≥ 0)

- Substrate uptake rates from experimental measurements

- Maximum enzyme capacities based on catalytic constants

Step 3: Objective Function Definition

- Select biologically relevant objective function Z = cTv

- Common objectives include:

- Biomass maximization for microbial growth prediction

- Metabolite production for biochemical engineering

- ATP production for energy metabolism studies

Step 4: Linear Programming Optimization

- Solve the linear programming problem: maximize Z subject to Sv = 0 and flux bounds

- Use optimization solvers (e.g., COBRApy, MATLAB) to identify optimal flux distribution

- Validate predictions against experimental growth or production data [1] [2]

Advanced FBA Techniques

Several extensions to standard FBA have been developed to address specific research questions and improve prediction accuracy:

Flux Variability Analysis (FVA)

- Determines the range of possible flux values for each reaction while maintaining optimal objective function value

- Identifies alternative optimal flux distributions

- Highlights network flexibility and redundancies

Parsimonious FBA (pFBA)

- Identifies the most efficient flux distribution among multiple optima

- Minimizes total flux through the network while maintaining optimal objective function

- Accounts for cellular preference for energy efficiency [1]

Enzyme-Constrained FBA (ecFBA)

- Incorporates enzyme abundance and catalytic efficiency constraints

- Caps fluxes based on enzyme availability: vi ≤ [Ei] × kcati

- Provides more realistic flux predictions by accounting for proteomic limitations [2]

Regulatory FBA (rFBA)

- Integrates Boolean logic-based rules with FBA

- Constrains reaction activity based on gene expression states and environmental signals

- Captures regulatory effects on metabolic states without requiring kinetic parameters [4] [5]

Application Notes for Metabolic Engineering

Case Study: L-Cysteine Overproduction in E. coli

A practical implementation of FBA for metabolic engineering demonstrates its utility in guiding strain design and process optimization:

Model Preparation and Modification

- Base model: iML1515 genome-scale model of E. coli K-12 MG1655

- Modifications to reflect genetic engineering:

- Updated enzyme kinetic parameters (Kcat) for mutated enzymes (SerA, CysE)

- Modified gene abundance values based on promoter strength and copy number

- Added missing thiosulfate assimilation pathways via gap-filling

- Applied enzyme constraints using ECMpy workflow [2]

Medium Formulation and Constraints

- Defined uptake rates for SM1 + LB medium components based on experimental measurements

- Blocked uptake of L-serine and L-cysteine to ensure flux through engineered pathways

- Included thiosulfate as sulfur source for enhanced L-cysteine production

Table 2: Medium Components and Uptake Constraints for L-Cysteine Production

| Medium Component | Associated Uptake Reaction | Upper Bound (mmol/gDW/h) |

|---|---|---|

| Glucose | EXglcDe_reverse | 55.51 |

| Citrate | EXcite_reverse | 5.29 |

| Ammonium Ion | EXnh4e_reverse | 554.32 |

| Phosphate | EXpie_reverse | 157.94 |

| Magnesium | EXmg2e_reverse | 12.34 |

| Sulfate | EXso4e_reverse | 5.75 |

| Thiosulfate | EXtsule_reverse | 44.60 |

Optimization Strategy

- Employed lexicographic optimization to balance L-cysteine export and biomass production

- First optimized for biomass, then constrained growth to 30% of maximum while optimizing for L-cysteine export

- This approach reflected the necessary compromise between production and growth in engineered strains [2]

Protocol Integration of Experimental Data with FBA Predictions

The accuracy of FBA predictions can be significantly enhanced through integration with experimental flux measurements:

13C-Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) Integration

- Use 13C labeling patterns to determine intracellular flux distributions

- Apply flux measurements as additional constraints in FBA models

- Validate and refine model predictions using experimental data [6]

TIObjFind Framework for Objective Function Identification

- Step 1: Reformulate objective function selection as optimization problem minimizing difference between predicted and experimental fluxes

- Step 2: Map FBA solutions onto Mass Flow Graph (MFG) for pathway-based interpretation

- Step 3: Apply minimum-cut algorithm to extract critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs)

- Implementation: Custom MATLAB code with Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm for efficient minimum-cut calculation [4] [5]

This framework enables identification of context-specific objective functions that better align with experimental observations across different environmental conditions.

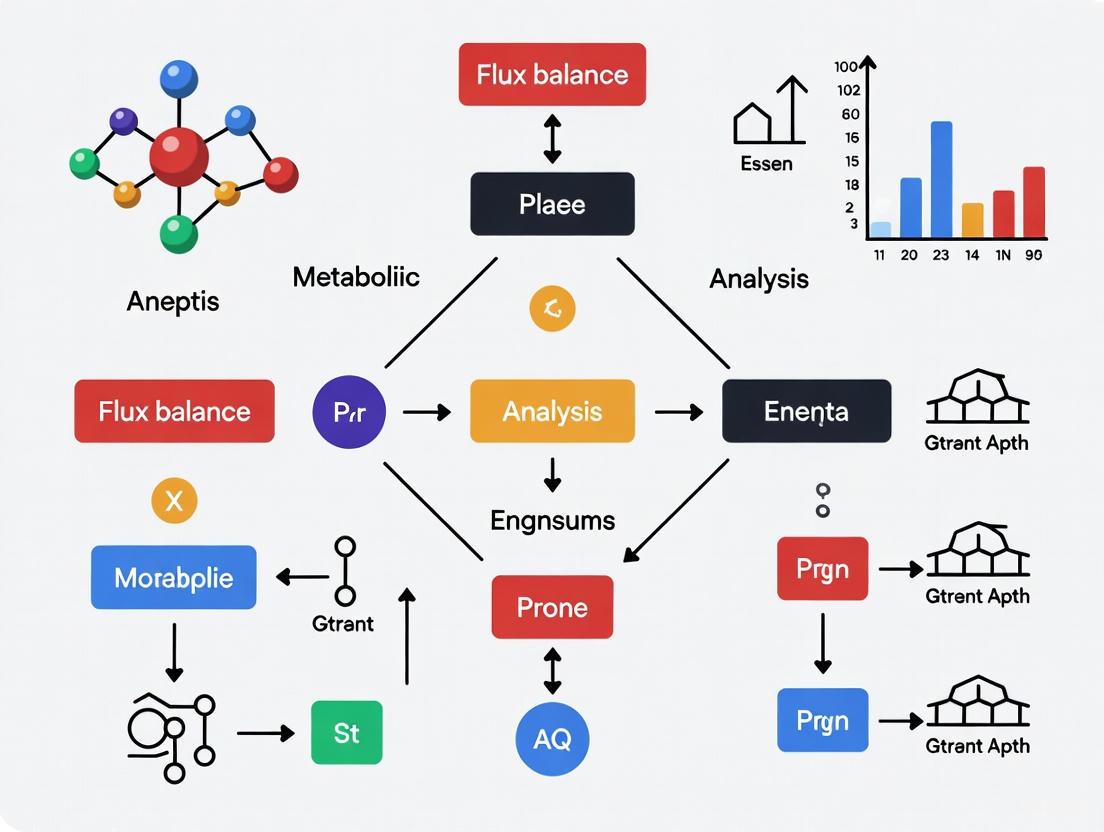

Visualization of FBA Workflow and Concepts

FBA Methodology Workflow

Advanced FBA Extension: TIObjFind Framework

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of FBA requires both computational tools and experimental resources for model construction and validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for FBA

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function in FBA Research |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Models | iML1515 (E. coli), Recon3D (human) | Provide curated stoichiometric matrices with gene-protein-reaction associations for specific organisms [2] |

| Metabolic Databases | KEGG, EcoCyc, MetaCyc | Source of biochemical pathway information, reaction stoichiometries, and metabolite identities [4] [5] |

| Enzyme Kinetic Databases | BRENDA, SABIO-RK | Provide enzyme kinetic parameters (Kcat, Km) for enzyme-constrained FBA implementations [2] |

| Software Platforms | COBRApy, MATLAB, CellNetAnalyzer | Implement FBA algorithms, optimization solvers, and visualization tools for constraint-based modeling [2] [5] |

| Experimental Validation Tools | 13C-MFA, LC-MS/MS, RNA-seq | Generate experimental flux measurements and omics data for model validation and refinement [6] |

| Protein Abundance Data | PAXdb, Proteomics datasets | Inform enzyme abundance constraints for ecFBA and proteome allocation models [2] |

Technical Considerations and Limitations

While FBA provides powerful capabilities for metabolic analysis, researchers should be aware of several important limitations and corresponding mitigation strategies:

Solution Space Degeneracy

- Multiple flux distributions can achieve identical objective function values

- Mitigation: Apply flux variability analysis or parsimonious FBA to identify realistic solutions [1]

Static vs. Dynamic Conditions

- Standard FBA assumes steady-state conditions without temporal dynamics

- Mitigation: Implement dynamic FBA (dFBA) to simulate batch cultures and changing environments [4]

Regulatory Oversimplification

- FBA does not inherently incorporate gene regulatory networks

- Mitigation: Integrate regulatory constraints via rFBA or similar approaches [4] [5]

Objective Function Selection

- Choosing inappropriate objective functions leads to biologically irrelevant predictions

- Mitigation: Use data-driven frameworks like TIObjFind to infer objective functions from experimental data [4] [5]

Thermodynamic Feasibility

- FBA solutions may include thermodynamically infeasible cycles

- Mitigation: Apply thermodynamic constraints via loopless FBA or network-embedded thermodynamic analysis [6]

In metabolic engineering, Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) serves as a fundamental computational method for predicting metabolic flux distributions within genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs). FBA operates on the principle of constraint-based modeling, where stoichiometric constraints and reaction bounds define a solution space of possible metabolic states. The critical element that guides the selection of a single flux distribution from this space is the objective function, a mathematical representation of the cell's presumed metabolic goal. The accurate selection of this function is paramount, as it directly influences the predictive capability of the model in simulating cellular behavior under various genetic and environmental conditions.

Historically, biomass maximization has been employed as the default objective function, based on the assumption that microorganisms have evolved to optimize growth. This function is formalized within a biomass equation that quantifies the required amounts of all known biomass precursors (e.g., amino acids, nucleotides, lipids). However, the accuracy of this approach is contingent upon the precise composition of the biomass equation, which can vary significantly across different environmental conditions and organisms [7]. While biomass maximization provides a good approximation for rapidly growing cells, it often fails to capture metabolic behaviors in stationary phases or under stress, where objectives such as ATP production, metabolite secretion, or survival take precedence. This limitation has spurred the development of more sophisticated, multi-objective optimization frameworks that can better represent the complex and dynamic priorities of cellular systems.

Advancements Beyond Biomass Maximization

The TIObjFind Framework: A Topology-Informed Approach

The TIObjFind (Topology-Informed Objective Find) framework represents a significant leap beyond single-objective optimization. It integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to systematically infer context-specific metabolic objectives from experimental data [4] [5]. This framework addresses a key limitation of traditional FBA: its inability to automatically adapt its objective function to reflect changing cellular priorities in response to environmental perturbations.

The TIObjFind framework operates through a structured, three-step process:

- Optimization Problem Formulation: It reformulates the objective function selection as an optimization problem that minimizes the difference between model-predicted fluxes and experimental flux data while simultaneously maximizing an inferred metabolic goal.

- Mass Flow Graph Construction: The FBA solutions are mapped onto a Mass Flow Graph (MFG), which provides a pathway-based interpretation of the metabolic flux distribution, transforming the network into a directed, weighted graph.

- Pathway Analysis and Coefficient Calculation: A minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., the Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm) is applied to this graph to identify critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs). These coefficients quantitatively represent each reaction's contribution to the overall cellular objective, acting as pathway-specific weights in the optimization [4].

This methodology allows researchers to analyze shifts in Coefficients of Importance across different biological stages, thereby revealing the system's changing metabolic priorities and identifying the objective function that best aligns with experimental observations [5].

Multi-Objective and Condition-Specific Optimization

Beyond topology-informed methods, other advanced approaches have been developed to address the complexities of cellular objective functions. In some biological contexts, such as cancer metabolism, conventional objectives like growth or ATP yield do not fully explain observed metabolic phenotypes. For instance, a study on 12 human cancer cell lines found that the total ATP regeneration flux did not correlate with growth rates. Instead, flux distributions could be accurately reproduced by an FBA model that maximized ATP consumption while considering a limitation of metabolic heat dissipation (enthalpy change). This suggests that thermal homeostasis can be a critical factor influencing metabolic objective functions, providing a potential explanation for the prevalence of aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells [6].

Furthermore, practical applications in metabolic engineering often require a balance between multiple, competing objectives. For example, a project aiming to optimize E. coli for L-cysteine production encountered a classic trade-off: maximizing product export led to predicted biomass growth of zero, an unrealistic outcome. To resolve this, lexicographic optimization was employed. This multi-objective technique involves first optimizing for biomass growth and then constraining the model to maintain a percentage of that optimal growth (e.g., 30%) while subsequently optimizing for the production target [2]. This ensures that solutions are both high-yielding and physiologically plausible.

Table 1: Advanced Frameworks for Objective Function Identification

| Framework Name | Core Methodology | Key Output | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIObjFind [4] [5] | Integrates FBA with Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) and graph theory. | Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) | Identifying stage-specific metabolic objectives and key pathways in biological systems. |

| ObjFind [4] | Maximizes a weighted sum of fluxes while minimizing error from experimental data. | Reaction weight coefficients (cj) | Aligning FBA predictions with experimental flux data. |

| Lexicographic Optimization [2] | Solves a sequence of optimization problems with ordered priorities. | A flux distribution satisfying multiple objectives. | Balancing cell growth with product synthesis in strain engineering. |

| FBAwEB [7] | Uses ensemble representations of biomass equations. | A range of flux distributions accounting for compositional uncertainty. | Mitigating errors from natural variations in biomass composition. |

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing the TIObjFind Framework

This protocol details the steps for applying the TIObjFind framework to identify context-dependent objective functions in a metabolic network, using the provided toy model as a reference [4].

I. Research Reagent Solutions Table 2: Essential Reagents and Computational Tools for TIObjFind

| Item | Function/Description | Example Source/Format |

|---|---|---|

| Genome-Scale Model (GEM) | Provides the stoichiometric matrix (S) and reaction bounds defining the metabolic network. | Model repositories (e.g., BiGG, MetaNetX). |

| Experimental Flux Data (vexp) | Ground-truth data for validating and fitting the model, often from 13C-MFA. | Isotopomer analysis, literature. |

| MATLAB Environment | Primary computational environment for executing the TIObjFind algorithm. | MathWorks MATLAB. |

| MATLAB maxflow package | Solves the minimum-cut problem in the Mass Flow Graph. | MATLAB built-in package [4]. |

| COBRA Toolbox | Performs standard FBA simulations and model manipulation. | Open-source MATLAB/Python toolbox. |

| Python with pySankey | Visualizes the resulting flux distributions and pathways. | Python package for Sankey diagrams. |

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Problem Formulation:

- Define the stoichiometric matrix S and the lower/upper bounds (lb, ub) for all reactions in the network.

- Formulate the optimization problem to find the coefficient vector c that minimizes the squared difference between predicted fluxes (v) and experimental fluxes (vexp), while maximizing the objective cTv.

Single-Stage FBA Optimization:

- Solve a series of FBA problems to find candidate flux distributions v* that fit the experimental data. This can be implemented using a Karush-Kuhn-Tucker (KKT) formulation.

- Example: For a toy model where the objective is assigned to reaction r6, the coefficient vector would be

c = [0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 0], resulting in a flux distributionv* = [0.60, 0.20, 0.32, 0.14, 0.32, 0.14, 0.46][4].

Mass Flow Graph (MFG) Construction:

- Map the calculated flux distribution v* onto a directed, weighted graph G(V, E).

- Nodes (V) represent metabolic reactions.

- Edges (E) represent metabolic fluxes between reactions, weighted by the flux value.

Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with Minimum Cut:

- Select start (source, s) and end (target, t) reactions. Typically, s is a substrate uptake reaction (e.g., glucose uptake), and t is a product secretion reaction.

- Apply a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to the MFG to identify the critical bottleneck pathways between s and t. The capacity of the minimum cut quantifies the maximum flow between these points.

Calculation of Coefficients of Importance (CoIs):

- The results from the minimum-cut analysis are used to compute the CoIs, which quantify the contribution of each reaction to the objective.

- These coefficients are then used as weights in the objective function for subsequent, more accurate FBA simulations.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps and data flow in the TIObjFind protocol:

Protocol 2: Implementing Enzyme-Constrained FBA for L-Cysteine Overproduction

This protocol applies a multi-objective strategy to engineer E. coli for L-cysteine production, demonstrating how to handle conflicting objectives like growth and yield [2].

I. Research Reagent Solutions Table 3: Key Reagents and Models for Enzyme-Constrained FBA

| Item | Function/Description | Example Source |

|---|---|---|

| iML1515 GEM | A high-quality genome-scale model of E. coli K-12 MG1655. | [Monk et al., 2017] |

| ECMpy Workflow | A Python package for adding enzyme constraints to GEMs without altering the stoichiometric matrix. | [Li et al., 2021] |

| COBRApy | A Python package for performing constraint-based reconstructions and analyses. | [Ebrahim et al., 2013] |

| BRENDA Database | Source of enzyme kinetic data (Kcat values). | https://www.brenda-enzymes.org/ |

| PAXdb | Source of protein abundance data. | https://pax-db.org/ |

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Model and Media Preparation:

- Acquire the base iML1515 GEM and update it using databases like EcoCyc to correct Gene-Protein-Reaction (GPR) relationships and reaction directions.

- Add any missing reactions critical for the study (e.g., thiosulfate assimilation pathways for L-cysteine production) via gap-filling.

- Set the medium conditions by defining the upper bounds for uptake reactions to reflect the experimental culture medium (e.g., SM1 + LB).

Incorporation of Enzyme Constraints:

- Use the ECMpy workflow to add enzyme capacity constraints.

- Split all reversible reactions into forward and reverse directions.

- Assign Kcat values from the BRENDA database and molecular weights from EcoCyc.

- Set the total protein mass fraction of the cell (e.g., 0.56).

- Integrate protein abundance data from PAXdb.

Parameter Modification to Reflect Genetic Engineering:

- Modify model parameters to reflect genetic manipulations. For example:

- Increase the

Kcat_forwardfor the PGCD reaction from 20 1/s to 2000 1/s to reflect the removal of feedback inhibition in the SerA enzyme. - Increase the gene abundance values for

SerAandCysEto reflect stronger promoters and higher plasmid copy numbers [2].

- Increase the

- Modify model parameters to reflect genetic manipulations. For example:

Lexicographic Optimization:

- Step 1: Set the objective function to biomass maximization and solve the FBA to find the maximum growth rate, μ_max.

- Step 2: Add a constraint to the model that requires the growth rate to be at a fixed percentage of μ_max (e.g., 30%).

- Step 3: Change the objective function to maximize the flux of the L-cysteine export reaction and solve the FBA again. This yields a flux distribution that supports substantial growth while maximizing product yield.

The logic of this multi-objective optimization is summarized in the following diagram:

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has become a cornerstone computational method in systems biology and metabolic engineering for predicting steady-state flux distributions in metabolic networks [8] [9]. This constraint-based approach analyzes metabolic functionality using physicochemical constraints without requiring detailed kinetic parameters, making it particularly valuable for genome-scale modeling [10]. FBA operates by defining a biological objective function—typically biomass maximization or metabolite production—and using linear programming to identify optimal flux distributions that satisfy stoichiometric mass-balance constraints under the steady-state assumption [8] [9]. The mathematical foundation of FBA is expressed as maximizing cᵀv subject to S⋅v = 0 and lower bound ≤ v ≤ upper bound, where S represents the stoichiometric matrix, v is the flux vector, and c is a vector of coefficients defining the biological objective [8].

Despite its widespread adoption and computational efficiency, FBA faces significant limitations in capturing the inherent flexibility of metabolic networks and their dynamic responses to changing environmental conditions [4] [5]. A primary challenge lies in the inherent degeneracy of optimal solutions, where multiple flux distributions can achieve the same optimal objective value, leading to uncertainty in predicting actual cellular behavior [11]. Furthermore, the critical assumption of static objective functions often fails to represent the adaptive nature of cellular metabolism under different physiological states or environmental perturbations [4] [5]. These limitations become particularly pronounced when modeling complex systems such as multi-species communities, industrial bioprocesses, or disease states like cancer metabolism, where metabolic priorities shift dynamically [4] [6]. This application note examines these key challenges in detail and provides structured frameworks and methodologies to enhance the predictive accuracy of FBA in capturing flux variability and condition-dependent cellular responses.

Quantitative Analysis of Key Limitations

Table 1: Primary Limitations in Capturing Flux Variability and Condition-Dependence

| Limitation Category | Specific Challenge | Impact on Predictive Accuracy | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methodological Constraints | High degeneracy of optimal FBA solutions | Non-unique flux distributions; uncertainty in network flexibility assessment | Requires 2n+1 LPs for comprehensive FVA of n reactions [11] |

| Environmental Sensitivity | Violation of steady-state assumptions under specific conditions | Biased flux peaks; inaccurate diurnal cycle predictions | Early transpiration peaks in cloud forests due to additional water vapor sources [12] |

| Objective Function Selection | Static objective functions not reflecting cellular adaptation | Poor prediction of metabolic fluxes and growth phenotypes in engineered strains | Discrepancy with 13C-MFA measured fluxes; failure to predict knockout strain behavior [9] [6] |

| Thermodynamic Oversimplification | Ignoring metabolic thermogenesis and heat dissipation | Inability to explain aerobic glycolysis in cancer cells (Warburg effect) | ATP maximization considering enthalpy change improved agreement with measured fluxes [6] |

| Metabolite Dilution | Failure to account for growth-associated dilution of intermediate metabolites | Biased gene essentiality and growth rate predictions | MD-FBA outperformed traditional FBA in 11,375 E. coli growth conditions [10] |

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of FVA Algorithm Improvements

| Algorithm Approach | Number of LPs Required | Computational Efficiency | Application Scale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional FVA | 2n+1 linear programs (n = number of reactions) | Lower efficiency; relies on parallelization for speed | Suitable for small to medium networks [11] |

| Improved FVA with Solution Inspection | <2n+1 linear programs | Reduced computational complexity; O(n²) inspection time | Benchmarked on networks from iMM904 to Recon3D [11] |

| FastFVA & VFFVA | 2n+1 linear programs | Maximized parallelization efficiency across CPU cores | Large-scale metabolic networks [11] |

The limitations detailed in Table 1 demonstrate fundamental gaps between standard FBA predictions and actual cellular behavior. The methodological constraint of solution degeneracy means that identifying a single optimal flux distribution provides an incomplete picture of metabolic capabilities [11]. Flux Variability Analysis (FVA) addresses this by quantifying the feasible ranges of reaction fluxes at optimal or sub-optimal production, but traditional implementations require substantial computational resources—solving 2n+1 linear programming problems for a network with n reactions [11]. Recent algorithmic improvements utilize basic feasible solution properties to reduce the number of required linear programs, significantly enhancing computational efficiency for large-scale models including human metabolic system Recon3D [11].

Environmental sensitivity presents another critical challenge, as demonstrated by applications of the Flux Variance Similarity (FVS) method in Taiwan's Chi-Lan montane cloud forest, where additional water vapor sources from valley wind violated method assumptions and produced biased early peaks of transpiration that did not align with observed diurnal cycles or sap flow measurements [12]. Similarly, high relative humidity conditions increased uncertainty due to minimal gradients between intercellular and ambient water vapor concentrations [12]. These findings emphasize how specific environmental conditions can fundamentally disrupt FBA assumptions, leading to erroneous predictions.

Perhaps the most significant limitation concerns the appropriate selection of objective functions. Conventional FBA often assumes static objectives like biomass maximization, failing to capture how cells dynamically adjust metabolic priorities in response to environmental changes [4] [5]. This shortcoming becomes evident when FBA predictions contradict fluxes measured via 13C-MFA, particularly in engineered strains or pathogenic organisms where metabolic objectives may diverge from optimal growth [9] [6]. The recently developed TIObjFind framework addresses this by integrating Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to systematically infer context-specific objective functions from experimental data [4] [5].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Enhanced Flux Variability Analysis

Principle: Traditional FVA characterizes the range of possible fluxes for each reaction while maintaining optimal objective function value, but can be computationally intensive. This enhanced protocol reduces computational burden through solution inspection [11].

Procedure:

- Phase 1 - Determine Optimal Objective Value: Solve the initial FBA problem to find Z₀ = maximize cᵀv subject to S⋅v = 0 and vₗ ≤ v ≤ vᵤ [11].

- Phase 2 - Calculate Flux Ranges: For each reaction i, solve two optimization problems (maximize and minimize vᵢ) with additional constraint cᵢv ≥ μZ₀, where μ represents fractional optimality [11].

- Solution Inspection: After each LP solution, check if flux variables attain their upper or lower bounds. If a bound is attained, skip the corresponding FVA optimization for that flux, as the extent is already known to be achievable [11].

- Algorithm Selection: Use primal simplex method rather than dual simplex to enable warm-starting subsequent LPs, avoiding initialization phases and reducing solve time by 30-100% [11].

Technical Notes: The solution inspection procedure scales linearly with network size (O(n)) and is called 2n+1 times during FVA, resulting in overall time complexity of O(n²)—significantly lower than solving a single LP [11]. This approach is particularly beneficial for large-scale models such as Recon3D (human metabolism) or iMM904 (yeast) [11].

Protocol 2: Metabolite Dilution Flux Balance Analysis

Principle: Standard FBA ignores growth-associated dilution of intermediate metabolites not included in biomass composition, leading to biologically implausible flux distributions and incorrect gene essentiality predictions. MD-FBA addresses this limitation [10].

Procedure:

- Model Formulation: Implement MD-FBA as a Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) problem that maximizes biomass production while accounting for dilution of all synthesized intermediate metabolites [10].

- Metabolite Tracking: Identify all intermediate metabolites produced via non-zero flux through metabolic reactions, applying uniform minimal dilution rate assumption when actual concentrations are unknown [10].

- Constraint Implementation: Incorporate growth dilution terms for all intermediate metabolites into mass-balance constraints, ensuring synthesis rates compensate for both metabolic consumption and biomass dilution [10].

- Validation: Apply MD-FBA to genome-scale metabolic network models (e.g., E. coli model with 1,260 genes, 2,382 reactions, 1,668 metabolites) and compare predictions with traditional FBA across diverse growth media and gene knockouts [10].

Application Guidance: MD-FBA is particularly crucial for metabolites participating in catalytic cycles, especially metabolic co-factors. Implementation requires MILP capability but significantly improves phenotype prediction accuracy, especially under varying nutrient conditions [10].

Protocol 3: Topology-Informed Objective Function Identification

Principle: Static objective functions in FBA often misrepresent cellular priorities under changing conditions. The TIObjFind framework systematically infers metabolic objectives by integrating Metabolic Pathway Analysis with FBA and experimental data [4] [5].

Procedure:

- Problem Formulation: Reformulate objective function selection as an optimization problem minimizing the difference between predicted and experimental fluxes while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal [4] [5].

- Mass Flow Graph Construction: Map FBA solutions onto a directed, weighted graph (Mass Flow Graph) representing metabolic flux distributions between reactions [4] [5].

- Pathway Analysis: Apply minimum-cut algorithms (Boykov-Kolmogorov recommended for computational efficiency) to extract critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's contribution to objective functions [4] [5].

- Iterative Refinement: Use CoIs as pathway-specific weights in FBA optimization, ensuring flux predictions align with experimental data while maintaining biological interpretability of network topology [4] [5].

Implementation Details: The TIObjFind framework has been implemented in MATLAB, utilizing MATLAB's maxflow package for minimum-cut calculations and Python with pySankey for visualization. The method has been validated in multi-species systems including Clostridium acetobutylicum and C. ljungdahlii IBE production systems [4] [5].

Visualization of Methodologies and Metabolic Relationships

Diagram 1: Workflow for Enhanced Flux Analysis. This diagram illustrates the integrated protocol for addressing FBA limitations through flux variability analysis and context-specific objective function identification.

Diagram 2: FBA Limitations and Corresponding Solutions. This diagram maps primary FBA challenges to specific methodological solutions discussed in this application note.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Advanced Flux Analysis

| Reagent/Tool | Specific Function | Application Context | Implementation Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox | MATLAB-based suite for constraint-based modeling | FBA, FVA, and network visualization; gene deletion studies | Integrates FBA algorithms, widely used in metabolic engineering [9] |

| 13C-MFA Assay Kits | Experimental flux quantification via isotopic labeling | Validation of FBA predictions; absolute flux measurements | Includes glucose uptake, metabolite, and enzyme activity assays [9] [6] |

| Metabolite Assay Kits | Quantitative analysis of specific metabolite concentrations | Constraint parameterization; model validation | ATP, amino acid, co-factor measurement kits [9] |

| TIObjFind Framework | Data-driven objective function identification | Context-specific FBA under changing conditions | MATLAB implementation with Python visualization [4] [5] |

| MD-FBA Algorithm | Account for metabolite dilution in growing cells | Improved gene essentiality and growth rate prediction | MILP formulation required [10] |

| FastFVA | High-performance FVA implementation | Large-scale metabolic network analysis | Enables parallelization of FVA calculations [11] |

The limitations of traditional FBA in capturing flux variability and condition-dependent responses represent significant challenges in metabolic engineering and systems biology research. This application note has detailed structured methodologies to address these limitations, including enhanced FVA with solution inspection, metabolite dilution-aware FBA, and topology-informed objective function identification. Successful implementation requires careful consideration of computational resources—particularly for MILP-based MD-FBA—and validation through experimental flux measurements via 13C-MFA. The presented frameworks enable researchers to move beyond static biomass maximization assumptions toward dynamic, context-aware metabolic modeling that better reflects biological reality. Future directions should focus on integrating regulatory constraints and multi-scale modeling approaches to further enhance predictive capabilities across diverse biological systems and conditions.

Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) has established itself as a cornerstone method in systems biology for predicting metabolic flux distributions in genome-scale metabolic models. However, conventional FBA operates on the fundamental assumption of steady-state conditions, which limits its ability to capture the dynamic adaptations and regulatory complexities that characterize living cells in changing environments [4]. This limitation becomes particularly significant when modeling biological systems for metabolic engineering and drug development, where temporal dynamics and cellular decision-making processes critically influence outcomes. To address these challenges, the field has developed sophisticated extensions that preserve the genome-scale scope of FBA while incorporating temporal and regulatory dimensions.

Dynamic FBA (dFBA) and Regulatory FBA (rFBA) represent two pivotal frameworks that have expanded the modeling capacity beyond steady-state constraints. dFBA introduces a time variable to simulate how metabolic fluxes change over time in response to evolving extracellular conditions [13]. Meanwhile, rFBA integrates regulatory mechanisms, often using Boolean logic-based rules, to constrain metabolic activity based on gene expression states and environmental signals [4]. These advanced frameworks enable researchers to model complex phenomena such as metabolic shifts in fermentation processes, competition between cell populations, and disease progression mechanisms that unfold over time and involve multi-layered regulation.

The integration of these methods has opened new avenues for applications ranging from optimizing bioproduction processes to understanding cancer metabolism and designing therapeutic interventions. This article provides a comprehensive overview of the methodologies, applications, and implementation protocols for dFBA and rFBA, specifically framed within metabolic engineering research for drug development applications.

Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis (dFBA)

Core Principles and Methodologies

Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis extends the capabilities of traditional FBA by incorporating temporal changes in extracellular metabolite concentrations and biomass levels. Where standard FBA predicts flux distributions at a single steady-state point, dFBA simulates metabolic behavior across multiple time points, capturing how nutrient depletion and product accumulation feedback to influence cellular metabolism [13]. This is achieved through a sequential optimization approach where FBA calculations are performed at discrete time intervals, with metabolite concentrations and biomass updated between each optimization step.

The fundamental mathematical implementation of dFBA employs ordinary differential equations (ODEs) to describe the time-dependent changes in extracellular metabolites coupled with FBA-derived internal fluxes:

dB/dt = μ·B

dC_i/dt = -v_uptake·B + v_production·B

Where B represents biomass concentration, μ is the growth rate determined by FBA, C_i represents extracellular metabolite concentrations, and v_uptake and v_production are exchange fluxes computed through FBA optimization [13]. A common implementation uses Euler's method for numerical integration, where the model is optimized using lexicographic optimization with bounds updated at each time step to reflect changing nutrient availability [13].

Implementation Protocol: Dynamic FBA

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Genome-scale metabolic model (e.g., in SBML format)

- Programming environment (Python with COBRApy or MATLAB with COBRA Toolbox)

- Initial metabolite concentrations

- Biomass growth parameters

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Initialization Phase:

- Load the genome-scale metabolic model and validate its consistency

- Set initial values for extracellular metabolites and biomass concentration

- Define the time step (Δt) for numerical integration (typically 0.1-0.5 hours)

- Specify total simulation time based on experimental observations

Dynamic Simulation Loop:

- For each time point from t=0 to t=final time: a. Apply FBA to calculate optimal flux distribution using current extracellular metabolite concentrations b. Extract growth rate (μ) and exchange fluxes from FBA solution c. Update biomass concentration: B(t+Δt) = B(t) + μ·B(t)·Δt d. Update extracellular metabolite concentrations: Ci(t+Δt) = Ci(t) + v_i·B(t)·Δt e. Check for nutrient depletion and adjust bounds accordingly f. Store flux distributions and concentration values for analysis

- Repeat until final simulation time is reached

Output Analysis:

- Plot biomass growth curve and metabolite concentration profiles over time

- Identify phase transitions in metabolic states

- Calculate product yields and substrate consumption rates

Troubleshooting Notes:

- Numerical instability may occur with large time steps; reduce Δt if oscillations are observed

- If growth ceases prematurely, verify upper bounds on nutrient uptake rates

- For multi-substrate systems, ensure correct prioritization through constraint ordering

Applications and Case Studies

dFBA has been successfully applied to model complex microbial behaviors such as metabolic switching in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1. During aerobic growth on lactate, this organism produces metabolic byproducts (pyruvate and acetate) that are subsequently consumed as alternative carbon sources when preferred nutrients are depleted [14]. Implementing dFBA to capture these sequential metabolic phases requires careful constraint management to simulate the dynamic substrate switching observed experimentally.

Another significant application involves modeling cell-cell competition through dynamic competition FBA (dcFBA). This extension specifically accounts for changes in cell density caused by competition for resources, addressing a critical limitation of standard dFBA when modeling multiple cell populations [15]. In multicellular systems or microbial consortia, dcFBA has revealed how "social" versus "asocial" cell behaviors impact population dynamics, with implications for understanding cancer progression and ecological blooms [15].

Table 1: Quantitative Parameters for dFBA Implementation in Case Studies

| Parameter | Shewanella oneidensis [14] | Cell Competition Model [15] |

|---|---|---|

| Time Step (Δt) | 0.1 hours | 1.0 month |

| Key Metabolites | Lactate, Pyruvate, Acetate, Oxygen | Glucose, Common Goods (X, Y) |

| Growth Rate (μ) | 0.2-0.5 h⁻¹ | 0.05-0.15 month⁻¹ |

| Simulation Duration | 50 hours | 60 months |

| Critical Constraints | Multi-step LP with byproduct parameters | Maximum metabolite production capacities |

Regulatory Flux Balance Analysis (rFBA)

Foundations and Methodological Framework

Regulatory Flux Balance Analysis addresses the critical need to incorporate gene regulatory influences on metabolic networks. While standard FBA assumes all metabolic genes are equally available, in reality, cellular regulation dynamically activates and represses different metabolic pathways in response to environmental and internal cues. rFBA formalizes this integration by combining Boolean logic-based regulatory rules with constraint-based metabolic modeling [4].

The core innovation of rFBA is its dual-layered structure: (1) a regulatory network that determines gene expression states based on environmental conditions, and (2) a metabolic network where these expression states translate into enzyme activity constraints. This framework explicitly accounts for the impact of gene regulation on metabolic states by integrating Boolean logic rules with FBA, thereby constraining reaction activity based on gene expression states and environmental signals [4]. Flexible implementations such as FlexFlux have extended this concept by combining qualitative regulatory networks with constraint-based modeling at genome scale, without requiring detailed kinetic parameters [4].

Advanced Framework: Topology-Informed Objective Finding

A recent innovation in regulatory metabolic modeling is the TIObjFind (Topology-Informed Objective Find) framework, which integrates Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA) with FBA to systematically infer context-specific objective functions [4] [5]. This approach addresses a fundamental challenge in FBA—selecting appropriate cellular objectives that reflect true physiological priorities under different conditions.

The TIObjFind framework operates through three key stages:

- Optimization Problem Formulation: Reformulates objective function selection as an optimization problem that minimizes the difference between predicted and experimental fluxes while maximizing an inferred metabolic goal

- Mass Flow Graph Construction: Maps FBA solutions onto a directed, weighted graph that enables pathway-based interpretation of metabolic flux distributions

- Pathway Analysis: Applies a minimum-cut algorithm (e.g., Boykov-Kolmogorov) to extract critical pathways and compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs), which serve as pathway-specific weights in optimization [4] [5]

This topology-informed approach selectively evaluates fluxes in key pathways, significantly enhancing interpretability and adaptability compared to methods that assign weights across all network reactions.

Implementation Protocol: Regulatory FBA with TIObjFind

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Genome-scale metabolic model with gene-protein-reaction associations

- Regulatory network (Boolean rules or gene expression data)

- MATLAB with maxflow package or Python with NetworkX

- Experimental flux data (if available for validation)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Network Integration:

- Map regulatory rules to metabolic genes using Boolean logic statements

- Define environmental conditions that trigger regulatory responses

- Establish gene expression states based on regulatory network

Constraint Application:

- For reactions associated with repressed genes, set upper and lower bounds to zero

- For activated genes, remove artificial constraints on corresponding reactions

- Implement temporal sequence if modeling dynamic regulation

TIObjFind-Specific Implementation:

- Calculate FBA solutions under varying cellular conditions

- Construct flux-dependent weighted reaction graph (Mass Flow Graph)

- Select start (e.g., glucose uptake) and target reactions (e.g., product secretion)

- Apply minimum-cut algorithm to identify critical pathways

- Compute Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) quantifying each reaction's contribution

- Validate against experimental flux data [4] [5]

Model Validation:

- Compare predicted flux distributions with experimental measurements (e.g., from 13C-MFA)

- Assess consistency of regulatory predictions with transcriptomic data

- Perform sensitivity analysis on regulatory parameters

Technical Notes:

- The minimum-cut problem can be solved using various algorithms (Ford-Fulkerson, Edmonds-Karp, Push-Relabel)

- The Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm offers superior computational efficiency for large networks [4]

- Visualization of results can be accomplished using Python's pySankey package

Comparative Analysis and Integration

Method Selection Guide

The choice between dFBA, rFBA, and integrated approaches depends on the specific biological question and available data. The following table provides guidance for method selection based on research objectives:

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Advanced FBA Frameworks

| Framework | Primary Application Context | Data Requirements | Computational Demand | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic FBA | Bioprocess optimization, Microbial community dynamics | Time-course metabolite data, Uptake kinetics | Medium to High (depending on time resolution) | Captures metabolite dynamics and diauxic shifts |

| Regulatory FBA | Cell differentiation, Stress responses, Disease mechanisms | Gene regulatory networks, Transcriptomic data | Low to Medium (depends on network complexity) | Predicts regulatory-metabolic interactions |

| dcFBA [15] | Multi-cell type competition, Cancer-microenvironment interactions | Cell-specific uptake rates, Growth parameters | High (multiple cell types) | Models resource competition and population dynamics |

| TIObjFind [4] [5] | Identifying metabolic objectives, Strain design | Experimental flux data, Pathway topology | Medium (optimization problem) | Data-driven objective function identification |

Integrated Workflow for Complex Systems

Many biological systems require integrating both dynamic and regulatory dimensions. For instance, modeling a microbial production host over a fermentation timeline may need to account for both changing nutrient availability (dynamic aspect) and regulatory responses to metabolite accumulation (regulatory aspect). The following diagram illustrates an integrated workflow for such applications:

Diagram Title: Integrated dFBA-rFBA Workflow

This integrated approach cycles between regulatory evaluation and dynamic simulation, enabling comprehensive modeling of complex biological systems where metabolism and regulation co-evolve over time.

Successful implementation of advanced FBA methods requires both computational tools and experimental data for validation. The following table catalogues essential resources referenced in the studies reviewed:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced FBA Implementation

| Resource | Type | Application Context | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| iMR799 [14] | Genome-Scale Model | Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 metabolism | Base metabolic network for dFBA simulations of metabolic switching |

| ClpXP Protease System [16] | Protein Degradation Machinery | Dynamic metabolic control in E. coli | Implement controlled proteolysis for metabolic valve operation |

| CRISPR Interference [16] | Gene Silencing System | Dynamic metabolic control | Enable targeted reduction of enzyme levels in two-stage bioprocesses |

| DAS+4 Peptide Tags [16] | Degradation Tag | Controlled proteolysis | Target proteins for ClpXP-mediated degradation in metabolic valves |

| 13C-MFA [6] | Experimental Flux Method | Cancer cell metabolism validation | Provide experimental flux data for FBA constraint refinement |

| MATLAB maxflow package [4] | Computational Tool | TIObjFind implementation | Solve minimum-cut problems for metabolic pathway analysis |

| pySankey [4] | Visualization Package | Metabolic flux visualization | Create Sankey diagrams of flux distributions in metabolic networks |

Future Directions and Emerging Methodologies

The field of advanced FBA continues to evolve with several promising methodologies emerging. Machine learning integration represents a particularly exciting frontier, with approaches such as artificial neural networks (ANNs) being employed as surrogate FBA models to dramatically reduce computational time in dynamic simulations [14]. These ANN-based surrogate models have demonstrated computational time reductions of several orders of magnitude compared to original LP-based FBA models while maintaining robust numerical stability without special stabilization measures [14].

Another significant development is the creation of NEXT-FBA, a hybrid stoichiometric/data-driven approach designed to improve intracellular flux predictions [17]. This methodology exemplifies the growing trend toward integrating machine learning with traditional constraint-based approaches to overcome limitations in both pure mechanistic and purely data-driven modeling.

For researchers working with complex microbial communities or host-pathogen systems, flux sampling approaches are gaining traction as they enable exploration of the entire space of feasible fluxes rather than focusing solely on optimal states [18] [19]. This is particularly valuable for modeling human tissues for drug development and microbial communities for synthetic ecology, where distributions of biologically relevant states may be more informative than single optimal predictions [18].

As these methodologies mature, they promise to further bridge the gap between computational prediction and experimental reality, advancing the application of metabolic models in both basic research and industrial applications.

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) are structured knowledge bases that mathematically represent all known metabolic reactions of an organism and their relationships to genes and proteins [20]. The core of a GEM is the stoichiometric matrix (S), where rows represent metabolites and columns represent biochemical reactions. This matrix enables constraint-based modeling approaches, notably Flux Balance Analysis (FBA), which predicts steady-state metabolic fluxes by optimizing an objective function (e.g., biomass production) within physicochemical constraints [20] [21]. Standard GEMs represent the metabolic potential of an organism. However, context-specific GEMs are computational reconstructions tailored to reflect metabolic activity under particular biological conditions by integrating multi-omics data [22]. This integration allows researchers to move from generic metabolic networks to models that simulate condition-specific physiological states, providing more accurate insights into cellular behavior in health, disease, or specific environmental conditions [23].

Data Types for Integration

The reconstruction of context-specific GEMs utilizes data from multiple molecular layers:

- Genomics: Gene presence/absence and variations [23]

- Transcriptomics: Gene expression levels (e.g., from RNA-Seq) [24] [23]

- Proteomics: Protein abundance data [23]

- Metabolomics: Metabolite concentration and flux measurements [22] [23]

- Epigenomics: DNA methylation and histone modification data [23]

Public Data Repositories

Several comprehensive repositories provide curated multi-omics datasets suitable for building context-specific GEMs:

Table 1: Major Public Repositories for Multi-Omics Data

| Repository Name | Primary Focus | Available Data Types | Web Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) | Cancer | RNA-Seq, DNA-Seq, miRNA-Seq, SNV, CNV, DNA methylation, RPPA [23] | https://cancergenome.nih.gov/ |

| International Cancer Genomics Consortium (ICGC) | Cancer | Whole genome sequencing, somatic and germline mutations [23] | https://icgc.org/ |

| Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) | Cancer | Proteomics data corresponding to TCGA cohorts [23] | https://cptac-data-portal.georgetown.edu/cptacPublic/ |

| Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) | Cancer cell lines | Gene expression, copy number, sequencing, drug response [23] | https://portals.broadinstitute.org/ccle |

| Omics Discovery Index (OmicsDI) | Consolidated multi-omics data | Genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics [23] | https://www.omicsdi.org |

Computational Frameworks and Algorithms for Integration

Multiple algorithms have been developed to extract context-specific GEMs from global reconstructions using omics data. The selection of an appropriate algorithm depends on data type, biological domain, and research questions [22].

Table 2: Categories of Model Extraction Methods for Context-Specific GEMs

| Method Category | Underlying Principle | Typical Data Inputs | Representative Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constraint-Based | Adds quantitative constraints to reaction fluxes based on omics data | Transcriptomics, Proteomics | INIT [22], MBA [22] |

| Machine Learning Hybrid | Combines mechanistic modeling with data-driven pattern recognition | Multi-omics datasets | MINN [25] |

| Stoichiometric | Uses network topology and expression data to extract active subnetworks | Transcriptomics, Proteomics | iMAT [22], GIMME [22] |

| Probabilistic | Employs Bayesian frameworks to integrate data with uncertainty estimates | Multiple omics data types with varying quality | FASTCORE [22] |

Metabolic-Informed Neural Networks (MINN): A Hybrid Approach

The MINN framework represents a recent advancement that hybridizes mechanistic modeling with machine learning. MINN integrates multi-omics data into GEMs to predict metabolic fluxes by leveraging the strengths of both approaches [25]. This architecture handles the trade-off between biological constraints and predictive accuracy through different model versions. In validation studies on E. coli multi-omics data from single-gene knockouts grown in minimal glucose medium, MINN demonstrated superior performance compared to traditional pFBA and random forest (RF) methods [25]. The framework also addresses conflicts between data-driven and mechanistic objectives and enhances interpretability through coupling with pFBA.

Protocol for Building Context-Specific GEMs Using Omics Data

Workflow for Model Construction

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for constructing context-specific GEMs using multi-omics data:

Detailed Experimental Methodology

Step 1: Preparation of Reference Genome-Scale Metabolic Model

- Obtain a comprehensive, well-curated GEM for your target organism from databases such as ModelSEED, BiGG, or AGORA2 [26] [27].

- For microbial systems, AGORA2 provides curated strain-level GEMs for 7,302 gut microbes, while ModelSEED offers reconstructions for diverse taxa [27].

- Verify model quality by ensuring mass and charge balance in all reactions and checking for energy-generating cycles [26].

Step 2: Acquisition and Preprocessing of Multi-Omics Data

- Extract relevant omics data from public repositories (Table 1) or generate experimental data.

- For transcriptomics data: Process raw RNA-Seq data through quality control, adapter trimming, alignment, and expression quantification [24].

- Normalize expression data using appropriate methods (e.g., TPM for RNA-Seq) and transform to log2 scale when necessary [24].

- Map gene identifiers between omics datasets and metabolic model gene annotations to ensure consistency [22].

Step 3: Context-Specific Model Extraction

- Select appropriate integration algorithm based on data availability and research question (Table 2).

- For INIT-like methods: Convert expression data to reaction weights, with highly expressed genes conferring higher weights to corresponding reactions [22].

- Set quantitative constraints using the COBRA Toolbox (MATLAB), COBRApy (Python), or RAVEN Toolbox [22].

- Define the biological objective function relevant to your context (e.g., biomass production, ATP synthesis, or metabolite secretion) [20] [27].

Step 4: Gap Filling and Model Refinement

- Identify metabolic gaps where the model cannot produce essential biomass precursors despite apparently complete pathways [26].

- Use computational gapfilling algorithms to propose minimal reaction additions that enable metabolic functionality [26].

- Implement gapfilling using linear programming to minimize the sum of flux through gapfilled reactions [26].

- Manually curate automated gapfilling solutions based on biochemical literature and experimental evidence [24].

Step 5: Model Validation and Quality Assessment

- Validate predictive accuracy by comparing simulated growth rates with experimental measurements where available [24].

- Assess gene essentiality predictions against experimental knockout studies [24] [28].

- Test substrate utilization predictions against phenotyping data [24].

- Evaluate flux predictions using 13C fluxomics data when available [22].

Step 6: Metabolic Simulation and Analysis

- Perform Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) to predict growth rates or metabolic secretion patterns [20] [21].

- Conduct flux variability analysis (FVA) to identify alternative optimal flux distributions [20].

- Implement robustness analysis to determine how changes in environmental conditions affect metabolic objectives [20].

- Use the finalized context-specific model for your specific applications: drug target identification, biomarker discovery, or metabolic engineering [22] [27].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Building Context-Specific GEMs

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| COBRA Toolbox [20] [22] | MATLAB toolbox for constraint-based modeling | Performs FBA, gap filling, and context-specific model extraction; supports SBML format models |

| COBRApy [22] | Python implementation of COBRA methods | Enables scripting of complex metabolic analyses and integration with machine learning libraries |

| RAVEN Toolbox [22] | MATLAB toolbox for network reconstruction and analysis | Includes functions for omics data integration and comparative analysis of metabolic networks |

| ModelSEED [26] | Web-based platform for automated model reconstruction | Generates draft models from genome annotations; uses standardized biochemistry database |

| AGORA2 [27] | Resource of curated GEMs for gut microbes | Contains 7,302 strain-level models for simulating host-microbe interactions |

| SBML [20] | Systems Biology Markup Language | Standardized format for exchanging metabolic models between tools and databases |

| SCIP/GLPK Solvers [26] | Optimization solvers for linear programming | Compute optimal flux distributions in FBA and gapfilling solutions |

Application Notes and Case Studies

Application in Live Biotherapeutic Development

Context-specific GEMs have shown particular utility in the systematic development of Live Biotherapeutic Products (LBPs). A recently proposed framework utilizes GEMs to characterize LBP candidate strains and their metabolic interactions with host cells at a systems level [27]. The approach involves:

- Top-down screening: Isolating microbes from healthy donor microbiomes and using AGORA2 GEMs to identify therapeutic targets through in silico analysis of metabolite exchange reactions [27].

- Bottom-up approach: Starting with predefined therapeutic objectives based on omics-driven analysis, then screening AGORA2 GEMs to identify candidates aligning with intended mechanisms [27].

- Strain evaluation: Assessing metabolic activity, growth potential, and environmental adaptability through FBA predictions across diverse nutritional conditions [27].

- Safety profiling: Identifying potential LBP-drug interactions, resistance mechanisms, and toxic metabolite production using constraint-based modeling [27].

Cancer Metabolic Subtyping Case Study

Srivastava and Vinod demonstrated the application of context-specific GEMs in identifying metabolic subtypes of endometrial cancer [22]. By integrating the Human Metabolic Reaction (HMR) database 2.0 with transcriptomics data from TCGA, they:

- Reconstructed context-specific models for endometrial cancer tumors

- Performed non-negative matrix factorization-based clustering of metabolic genes

- Identified two distinct metabolic subtypes with different patient survival outcomes

- Correlated these metabolic subtypes with histological and clinical features

- The approach provided insights into metabolic reprogramming in cancer cells and identified potential metabolic vulnerabilities for therapeutic targeting [22].

Advanced Integration Techniques and Future Directions

Multi-Omics Integration Challenges and Solutions

Current challenges in multi-omics integration for metabolic modeling include:

- Data heterogeneity: Different omics layers have varying scales, noise characteristics, and missing data patterns [23].

- Temporal mismatches: Discrepancies in timing between transcript, protein, and metabolite measurements [22].

- Spatial considerations: Subcellular localization and tissue compartmentalization effects [22]. Emerging solutions include:

- Multi-layer integration algorithms that simultaneously incorporate transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic constraints [22].

- Time-resolved modeling approaches that capture metabolic dynamics [22].

- Machine learning hybrids like MINN that leverage both data-driven patterns and mechanistic constraints [25].

Workflow for Advanced Multi-Omics Integration

For complex multi-omics integration projects, the following detailed workflow ensures robust context-specific model construction:

The integration of multi-omics data into genome-scale metabolic models represents a powerful paradigm for understanding context-specific metabolism in disease, biotechnology, and basic research. Following the detailed protocols and methodologies outlined in this application note will enable researchers to construct biologically meaningful models that bridge the gap between genomic potential and observed metabolic phenotypes. As computational methods continue to advance, particularly through hybrid machine learning and mechanistic approaches, the accuracy and applicability of context-specific GEMs will further expand their utility in metabolic engineering and therapeutic development.

Advanced FBA Frameworks and Their Biotechnological Applications

The Topology-Informed Objective Find (TIObjFind) framework represents a significant methodological advancement in constraint-based metabolic modeling by systematically integrating Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) with Metabolic Pathway Analysis (MPA). This novel optimization-based approach addresses the critical challenge of selecting appropriate cellular objective functions in dynamic biological systems by introducing Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each metabolic reaction's contribution to overall cellular objectives. By leveraging network topology and experimental flux data, TIObjFind enables researchers to infer context-specific metabolic goals, align computational predictions with experimental observations, and uncover adaptive metabolic shifts in response to environmental perturbations. This protocol details the theoretical foundation, computational implementation, and practical application of TIObjFind, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for enhancing the biological relevance of metabolic models in strain engineering, drug discovery, and systems biology research.

Flux Balance Analysis is a cornerstone mathematical approach for analyzing metabolite flow through genome-scale metabolic networks by calculating steady-state flux distributions that optimize a specified cellular objective [20] [8]. The method operates on the fundamental mass balance constraint at steady state, represented mathematically as:

[ S \cdot v = 0 ]

Where (S) is the (m \times n) stoichiometric matrix ((m) metabolites and (n) reactions), and (v) is the vector of reaction fluxes. FBA formulates phenotype prediction as a linear programming problem to maximize or minimize an objective function (Z = c^T v), where (c) is a vector of weights indicating how much each reaction contributes to the objective [20]. Common biological objectives include biomass production, ATP generation, or synthesis of specific metabolites.

Despite its widespread application in bioprocess engineering, drug target identification, and microbial physiology studies [8], traditional FBA faces a fundamental limitation: its predictive accuracy heavily depends on selecting an appropriate single objective function, which may not adequately capture cellular behaviors across different environmental conditions or growth phases [5] [4]. Microorganisms dynamically adjust their metabolic priorities in response to environmental changes, yet standard FBA implementations often utilize static objective functions that cannot represent these adaptive metabolic shifts.

Theoretical Foundation of TIObjFind

The TIObjFind framework addresses the objective function selection challenge by integrating MPA with FBA to systematically infer metabolic objectives from experimental data [5]. The methodology introduces Coefficients of Importance (CoIs) that quantify each reaction's additive contribution to a cellular objective, effectively creating a weighted combination of fluxes that aligns model predictions with experimental flux data [4].

Conceptual Framework and Key Innovations

TIObjFind builds upon the earlier ObjFind framework, which maximized a weighted sum of fluxes while minimizing the sum of squared deviations from experimental data [4]. However, TIObjFind introduces several key innovations that significantly enhance its capabilities:

- Topology-Aware Optimization: Unlike ObjFind, which assigned weights across all metabolites, TIObjFind utilizes network topology to focus on specific pathways, reducing overfitting potential and improving biological interpretability [5]

- Pathway-Centric Weighting: The framework employs MPA to distribute importance to metabolic pathways rather than individual reactions, better capturing systemic metabolic adaptations [5]

- Mass Flow Graph Representation: FBA solutions are mapped onto a flux-dependent weighted reaction graph that enables pathway-based interpretation of metabolic flux distributions [4]

Mathematical Formulation

The TIObjFind framework solves an optimization problem that minimizes the difference between predicted fluxes ((v)) and experimental flux data ((v^{exp})), while simultaneously maximizing an inferred metabolic goal derived from the stoichiometry of biochemical networks [4]. The approach can be conceptualized as a scalarization of a multi-objective optimization problem, formalized as:

[ \begin{aligned} & \underset{v}{\text{minimize}} & & \| v - v^{exp} \|^2 \ & \text{subject to} & & S v = 0 \ & & & v{min} \leq v \leq v{max} \end{aligned} ]

The solution to this optimization yields flux distributions that are subsequently mapped to a Mass Flow Graph (MFG) for pathway analysis and computation of Coefficients of Importance [4].

Computational Implementation of TIObjFind

The TIObjFind framework implements a structured three-step computational workflow that transforms traditional FBA into a topology-informed, data-driven optimization approach.

Stepwise Workflow and Data Transformation

Technical Implementation Specifications

The TIObjFind framework was implemented in MATLAB, with custom code for the primary analysis and minimum cut set calculations performed using MATLAB's maxflow package [5]. The implementation employs specific computational strategies:

- Algorithm Selection: The Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm was selected for minimum-cut calculations due to its demonstrated near-linear performance across various graph sizes and superior computational efficiency compared to conventional algorithms [5]

- Visualization: Results visualization was accomplished using Python with the pySankey package, enabling intuitive representation of complex flux distributions and pathway relationships [5]

- Data Integration: The framework incorporates experimental flux data obtained through techniques such as isotopomer analysis, though this requirement presents practical limitations for organisms where such data are scarce [4]

Table 1: Computational Tools and Resources for TIObjFind Implementation

| Resource Name | Type/Function | Implementation Role | Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| MATLAB | Numerical computing environment | Primary computational platform | Commercial license |

| MATLAB maxflow package | Graph algorithm library | Minimum cut set calculations | Included in MATLAB |

| Boykov-Kolmogorov algorithm | Minimum-cut algorithm | Identifies critical pathways in MFG | Open implementation |

| COBRA Toolbox | Constraint-based modeling | FBA simulations | Open source [20] |

| pySankey (Python) | Data visualization | Flux distribution plotting | Open source |

| Genome-scale models (e.g., iCAC802) | Metabolic network reconstructions | Stoichiometric matrix input | Public repositories |

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

This section provides detailed methodological protocols for applying TIObjFind, validated through two case studies demonstrating its utility in predicting metabolic adaptations.

Case Study 1: Clostridium acetobutylicum Glucose Fermentation

Background: This case study applies TIObjFind to analyze the glucose fermentation metabolism of Clostridium acetobutylicum, an organism relevant to industrial solvent production [5].

Experimental Protocol:

Model Preparation

- Obtain the genome-scale metabolic model for C. acetobutylicum (e.g., iCAC802)

- Define system boundaries and environmental conditions (glucose minimal medium)

- Set flux constraints for glucose uptake and gas exchange reactions

Experimental Data Collection

- Cultivate C. acetobutylicum under controlled bioreactor conditions

- Measure extracellular flux rates (glucose consumption, organic acid, and solvent production)

- Quantify intracellular fluxes using 13C metabolic flux analysis for key central metabolic pathways

TIObjFind Implementation

- Formulate the optimization problem with experimental flux data as constraints

- Compute optimal flux distributions using the primal-dual transformation

- Construct the Mass Flow Graph with glucose uptake as source (s) and product secretion reactions as targets (t)

Pathway Analysis

- Apply minimum-cut algorithm to identify critical pathways

- Calculate Coefficients of Importance for reactions in central carbon metabolism

- Compare pathway weights across different fermentation phases (acidogenic vs. solventogenic)

Results Interpretation: The analysis revealed shifting Coefficients of Importance for enzymes in the acidogenesis-to-solventogenesis transition, accurately capturing the metabolic reorientation from acetate/butyrate to ethanol/butanol production and reducing prediction errors by 34% compared to static biomass maximization objectives [5].

Case Study 2: Multi-Species IBE Production System

Background: This case study examines a more complex multi-species system for isopropanol-butanol-ethanol (IBE) production co-culturing C. acetobutylicum and C. ljungdahlii [5] [4].

Experimental Protocol:

System Modeling

- Develop a combined metabolic model representing both species

- Define metabolite exchange and cross-feeding interactions

- Establish community-level objective functions

Data Integration

- Measure species-specific metabolic fluxes using isotope labeling experiments

- Quantify metabolite exchange rates between species

- Monitor population dynamics and product titers over time

TIObjFind Analysis

- Implement the framework with stage-specific experimental data

- Compute Coefficients of Importance for cross-species metabolic exchanges

- Identify critical interconnection points in the multi-species network

Validation

- Compare predicted vs. measured community metabolic phenotypes

- Test model predictions by perturbing key identified pathways

- Evaluate CoI stability through cross-validation