Foundation Models in Bioinformatics: A New Era of AI-Driven Biological Discovery

Foundation Models (FMs) are instigating a paradigm shift in bioinformatics, offering powerful solutions to long-standing challenges such as limited annotated data and high data noise.

Foundation Models in Bioinformatics: A New Era of AI-Driven Biological Discovery

Abstract

Foundation Models (FMs) are instigating a paradigm shift in bioinformatics, offering powerful solutions to long-standing challenges such as limited annotated data and high data noise. This review synthesizes current advancements, focusing on the application of these large-scale, self-supervised AI models across key biological domains like genomics, proteomics, drug discovery, and single-cell analysis. We explore the core architectures of language, vision, graph, and multimodal FMs, providing a guide for researchers to select appropriate models. The article further critically examines methodological applications, persistent challenges in data and interpretability, and rigorous benchmarking studies that pit FMs against traditional methods. Finally, we discuss future trajectories, outlining how FMs are poised to fuel continued innovation in molecular biology and clinical research.

What Are Foundation Models? Redefining AI's Role in Biology

Foundation Models (FMs) represent a transformative paradigm in artificial intelligence, characterized by their training on broad data at scale and adaptability to a wide range of downstream tasks [1]. The term was coined by researchers at the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence in 2021 to describe models that are "trained on broad data (generally using self-supervision at scale) that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks" [1]. These models have fundamentally changed how data scientists approach machine learning by providing a versatile starting point for developing specialized applications more quickly and cost-effectively than training models from scratch [2].

In bioinformatics, FMs address longstanding challenges such as limited annotated data and data noise by leveraging self-supervised learning on massive, unlabeled datasets [3]. Their capacity to learn accurate representations of intricate biological data through data-intensive pretraining enables researchers to utilize these models for various downstream tasks with limited data through fine-tuning mechanisms [3]. This flexibility has positioned FMs as essential tools for tackling core biological problems including sequence analysis, structure prediction, and function annotation across diverse data modalities including DNA, RNA, proteins, and single-cell multi-omics data [3].

Core Architecture and Technical Foundation

Defining Characteristics of Foundation Models

Foundation models exhibit several distinguishing characteristics that separate them from traditional machine learning approaches:

- Broad training data: FMs are trained on extensive, generalized datasets that span multiple domains or modalities, enabling wide applicability [2] [1].

- Self-supervised learning: These models primarily use self-supervised learning objectives during pretraining, creating labels directly from the input data without human annotation [2] [4].

- Adaptability: A fundamental feature of FMs is their ability to be adapted through fine-tuning, prompt engineering, or other techniques to perform specialized downstream tasks [2] [1].

- Scale: Advanced FMs typically contain tens of billions of parameters and require substantial computational resources for training [2] [1].

The adaptability of FMs is particularly valuable in bioinformatics, where they can be fine-tuned for specific biological problems, narrowing the representation gap between general domain knowledge and specialized biological domain knowledge [3].

The Role of Self-Supervised Learning

Self-supervised learning has become the cornerstone of modern foundation models, enabling them to learn powerful representations from vast amounts of unlabeled data [5]. By designing auxiliary tasks on raw inputs, SSL removes the reliance on human-provided labels and underpins the pretraining-finetuning paradigm that has reshaped machine learning beyond traditional empirical risk minimization frameworks [5].

In the context of FMs, SSL works by creating learning signals directly from the structure of the data itself. For example, in language models, this might involve predicting masked words in a sequence, while in biological sequences, it might involve predicting masked nucleotides or amino acids [3]. The model learns meaningful representations by solving these pretext tasks, capturing underlying patterns and relationships in the data without explicit human labeling [4] [5].

Table 1: Common Self-Supervised Learning Objectives in Foundation Models

| SSL Objective | Mechanism | Example Models | Biological Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Masked Language Modeling | Randomly masks portions of input and trains model to predict masked content | BERT, DNABERT [3] | Predicting masked nucleotides or amino acids in sequences |

| Contrastive Learning | Learns representations by contrasting similar and dissimilar pairs | CONCH [6] | Matching histopathology images with textual descriptions |

| Autoregressive Modeling | Predicts next element in a sequence given previous elements | GPT series, scGPT [2] [6] | Generating biological sequences or predicting next element |

| Replaced Token Detection | Distinguishes between real input elements and plausible fakes | BioELECTRA [6] | Identifying functional genomic elements |

Architectural Components

Foundation models leverage sophisticated neural network architectures optimized for handling large-scale, complex data:

Transformer architectures: Many FMs utilize transformer networks with self-attention mechanisms that can capture long-range dependencies in sequential data [2] [3]. The bidirectional nature of transformers in models like BERT enables comprehensive context understanding [3].

Graph Neural Networks: For biological data with inherent graph structure, GNNs process graph-structured information where nodes represent biological entities and edges represent relationships [3] [7]. Models like TxGNN use GNNs to embed drugs and diseases into a latent representational space that reflects the geometry of medical knowledge graphs [7].

Multimodal architectures: Advanced FMs can process and integrate multiple data types through unified architectures. For example, CONCH combines visual and language-based learning for histopathology analysis [6].

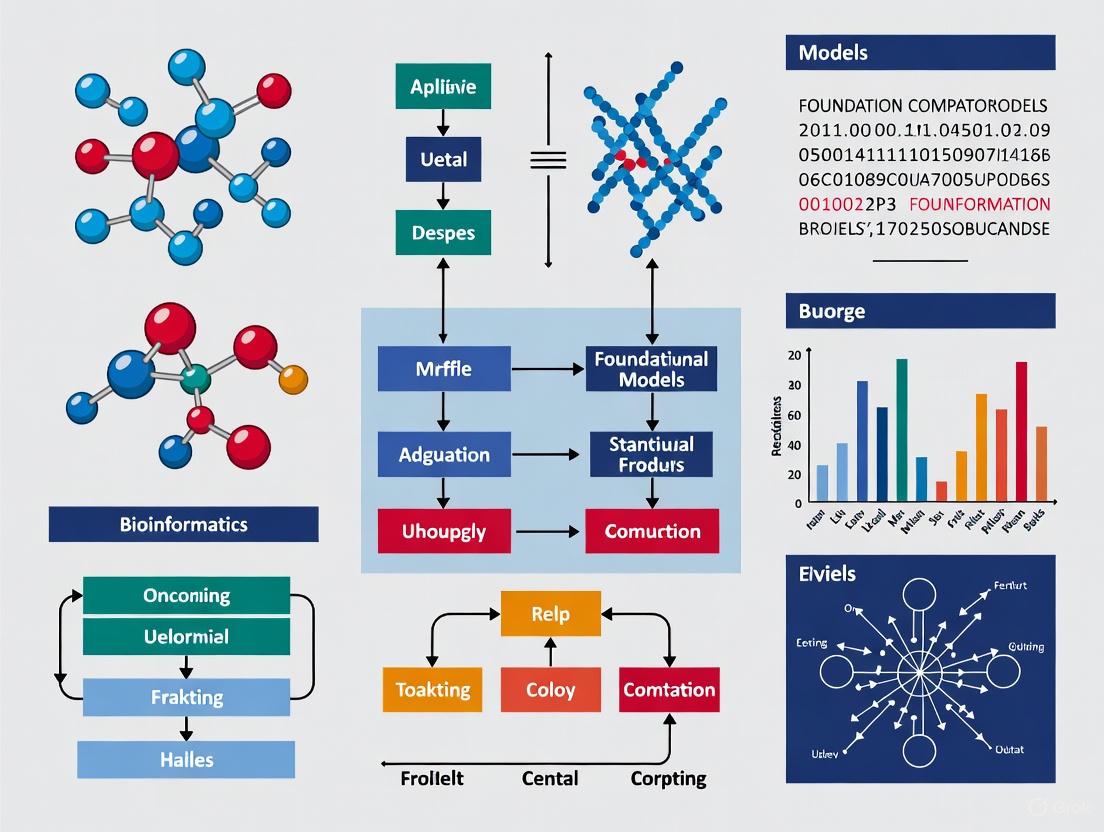

The following diagram illustrates the core self-supervised learning process that underpins foundation model pretraining:

Diagram 1: Self-Supervised Learning Process

Adaptation Methodologies: From Pretraining to Specialized Applications

The Adaptation Pipeline

Foundation models transition from general pretraining to specialized applications through carefully designed adaptation methodologies. This process typically involves two main phases: pretraining and adaptation [4]. During pretraining, the model learns general representations from a massive dataset using self-supervised learning objectives. The adaptation phase then customizes the model for specific downstream tasks, which may involve fine-tuning, linear probing, or other techniques [4].

In bioinformatics, this adaptation pipeline is particularly valuable because it allows researchers to leverage knowledge learned from large-scale biological datasets and apply it to specialized problems with limited labeled data [3]. The adaptation process can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 2: Foundation Model Adaptation Pipeline

Key Adaptation Techniques

The adaptation of foundation models to specialized tasks can be accomplished through several technical approaches:

Fine-tuning: This approach updates both the pretrained model parameters and the task-specific head using the downstream dataset [4]. Fine-tuning allows the model to adjust its representations to the specific nuances of the target task while retaining knowledge from pretraining.

Linear probing: In this method, the pretrained model parameters remain frozen, and only a linear classification head is trained on the downstream task [4]. This approach is useful for assessing the quality of the learned representations and for scenarios with limited computational resources.

Prompt engineering: Particularly prevalent in language models, this technique involves crafting input prompts to steer the model toward desired outputs without updating model parameters [2].

Metric learning for zero-shot prediction: Models like TxGNN implement metric learning components that transfer knowledge from well-annotated domains to those with limited treatments by measuring similarities between entities in the learned representation space [7].

Table 2: Adaptation Techniques for Foundation Models in Bioinformatics

| Adaptation Method | Parameters Updated | Data Requirements | Use Cases in Bioinformatics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fine-tuning | All parameters | Moderate labeled data | Specializing protein language models for specific families |

| Linear Probing | Only final layer | Limited labeled data | Rapid prototyping, representation quality assessment |

| Prompt Engineering | None | No labeled data | Leveraging LLMs for biological knowledge extraction |

| Metric Learning | Similarity metrics | Limited to no labeled data | Zero-shot drug repurposing [7] |

Foundation Models in Bioinformatics: Case Studies and Experimental Approaches

TxGNN: A Case Study in Drug Repurposing

TxGNN represents a pioneering application of foundation models in bioinformatics, specifically designed for zero-shot drug repurposing [7]. This model addresses the critical challenge of identifying therapeutic candidates for diseases with limited treatment options or no existing drugs—a scenario that affects approximately 92% of the 17,080 diseases examined in the original study [7].

Experimental Protocol for TxGNN:

Knowledge Graph Construction: TxGNN is trained on a comprehensive medical knowledge graph that collates decades of biological research across 17,080 diseases, containing 9,388 indications and 30,675 contraindications [7].

Model Architecture: The framework consists of two main modules:

- TxGNN Predictor: A graph neural network optimized on relationships in the medical KG that produces meaningful representations for all concepts through large-scale, self-supervised pretraining [7].

- TxGNN Explainer: A module that provides interpretable insights through multi-hop medical knowledge paths that form the predictive rationales [7].

Zero-shot Prediction Mechanism: TxGNN implements a metric learning component that creates disease signature vectors based on neighborhood topology in the KG. When querying a specific disease, it retrieves similar diseases, generates embeddings for them, and adaptively aggregates them based on similarity to the queried disease [7].

Evaluation: Under stringent zero-shot evaluation, TxGNN improved prediction accuracy for indications by 49.2% and contraindications by 35.1% compared to eight benchmark methods [7].

The following diagram illustrates the TxGNN architecture and workflow for drug repurposing:

Diagram 3: TxGNN Architecture for Drug Repurposing

Experimental Protocols for Biological Foundation Models

The evaluation of foundation models in bioinformatics requires specialized experimental protocols that account for the unique characteristics of biological data and research questions:

Benchmarking Protocol for Sequence-Based FMs:

- Data Partitioning: Implement rigorous cross-validation strategies that account for sequence homology to avoid data leakage [3].

- Baseline Comparison: Compare against traditional machine learning approaches and specialized bioinformatics tools [3] [7].

- Performance Metrics: Utilize domain-appropriate metrics including area under the precision-recall curve (AUPRC), receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, and rank-based metrics [7].

- Biological Significance Validation: Where possible, validate computational predictions with experimental evidence from literature or new experiments [7] [6].

Interpretability Analysis Protocol:

- Attention Visualization: For transformer-based models, analyze attention patterns to identify biologically relevant regions in sequences [3].

- Pathway Enrichment: For models generating embeddings, perform enrichment analysis on genes or proteins with similar representations [6].

- Ablation Studies: Systematically remove components of the model or input features to assess their contribution to performance [7].

Table 3: Key Foundation Models in Bioinformatics and Their Applications

| Model | Modality | Architecture | Primary Applications | Notable Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold [6] | Protein sequences | Neural networks | 3D protein structure prediction | Near-experimental accuracy, 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry |

| DNABERT [3] [6] | DNA sequences | Transformer | Predicting regulatory regions | Adapts BERT to understand DNA sequences contextually |

| Geneformer [6] | Single-cell transcriptomics | Transformer | Predicting tissue-specific gene network dynamics | Trained on 30-95 million single-cell transcriptomes |

| scGPT [6] | Single-cell data | Transformer | Cell annotation, gene network inference | Distills insights from ~30 million cells |

| TxGNN [7] | Medical knowledge graph | Graph Neural Network | Zero-shot drug repurposing | 49.2% improvement in indication prediction accuracy |

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The development and application of foundation models in bioinformatics requires specialized computational "reagents" and resources. The following table details key resources that constitute the essential toolkit for researchers in this field:

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Foundation Model Development in Bioinformatics

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Architectures | Transformer, GNN, VAE | Core neural network architectures for processing different data types | Transformers for sequences [3], GNNs for knowledge graphs [7] |

| Pretraining Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, JAX | Enable efficient large-scale model training | Implementing self-supervised learning objectives [5] |

| Biological Data Resources | NCBI, UniProt, Protein Data Bank | Provide structured biological data for pretraining | Protein sequences, 3D structures, genomic data [6] |

| Specialized Model Hubs | Hugging Face, Model Zoo | Repository of pretrained models for adaptation | Access to nearly 200,000 models [2] |

| Knowledge Graphs | Medical KG [7], Biological networks | Structured knowledge representation | TxGNN training [7], relationship mining |

| Interpretability Tools | GraphMask [7], Attention visualization | Explain model predictions and rationales | TxGNN Explainer module [7] |

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite their remarkable capabilities, foundation models in bioinformatics face several significant challenges that represent opportunities for future research:

Technical and Methodological Challenges

Data quality and bias: Foundation models can pick up inappropriate patterns or biases from training data, requiring careful data filtering and norm encoding [2]. In biological contexts, this may manifest as overrepresentation of well-studied organisms or pathways.

Interpretability and reliability: The complex, nonlinear features extracted by FMs face challenges regarding biological interpretability and model reliability [3]. Methods like TxGNN's Explainer module represent important steps toward addressing this challenge [7].

Computational requirements: Building a foundation model from scratch is expensive and requires enormous resources, with training potentially taking months [2]. This creates barriers to entry for many research institutions.

Generalization limitations: While FMs exhibit strong performance across many tasks, they may struggle with out-of-distribution data or rare biological phenomena not well-represented in training data [3].

Emerging Research Directions

Several promising research directions are emerging at the intersection of foundation models and bioinformatics:

Multimodal foundation models: Integrating multiple data types (e.g., sequences, structures, images, text) within unified architectures to capture complementary biological information [3] [6].

Federated learning approaches: Developing methods to train FMs across distributed biological datasets while maintaining data privacy and security [3].

Causal representation learning: Moving beyond correlational patterns to discover causal relationships in biological systems [3].

Resource-efficient adaptation: Creating methods that enable effective adaptation of large FMs with limited computational resources and labeled data [4] [3].

The rapid evolution of foundation models continues to reshape the bioinformatics landscape, offering unprecedented opportunities to decipher complex biological systems and accelerate therapeutic development. As these models become more sophisticated, accessible, and interpretable, they are poised to become indispensable tools in the researcher's toolkit, ultimately bridging the gap between data-intensive biology and actionable biological insights.

The field of bioinformatics has undergone a profound transformation, driven by the exponential accumulation of biological data from high-throughput sequencing technologies and multi-omics approaches [8]. This data deluge posed significant challenges for analysis and interpretation, creating an urgent need for more sophisticated computational approaches [8]. Concurrently, artificial intelligence (AI) has achieved groundbreaking advances, evolving from specialized, niche models handling specific biological tasks to powerful general-purpose tools capable of addressing fundamental biological questions across multiple domains [8] [9]. This evolution has been marked by the emergence of foundation models (FMs)—large-scale AI systems pretrained on vast datasets that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks [9] [10]. These models represent a paradigm shift from task-specific solutions to versatile tools that leverage transfer learning and self-supervised pretraining to capture universal patterns in biological data [10]. The integration of AI in bioinformatics has now reached a pivotal moment where these systems are not merely analytical tools but collaborative partners in scientific discovery, enabling breakthroughs in genomics, proteomics, drug discovery, and single-cell analysis [8] [9] [10].

The Trajectory of AI in Bioinformatics: From Specific to General

The Era of Traditional Machine Learning

Initial applications of AI in bioinformatics relied heavily on traditional machine learning (ML) methods, which excelled in scenarios with well-defined features and controlled experimental conditions [8]. These approaches operated within a structured framework where models learned functions to minimize objective functions for classification or regression tasks [8]. Support vector machines (SVM) and random forests (RF) became workhorses for analyzing genomic sequencing fragments, physicochemical properties of proteins, and medical imaging signals [8]. While effective for specific, limited-scale datasets, these methods required substantial feature engineering and domain expertise, constraining their applicability to broader biological questions. Their performance was closely tied to data quality and manual curation, making them suitable for targeted analyses but inadequate for extracting generalizable insights from the increasingly complex and massive biological datasets being generated [8].

The Deep Learning Revolution

The limitations of traditional ML prompted a shift toward deep learning approaches, characterized by complex neural networks that perform automated feature extraction and transformation across multiple processing layers [8]. Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) demonstrated remarkable capabilities in capturing spatial and sequential dependencies in biological data, enabling more sophisticated analysis of genomic sequences and protein structures [8]. A pivotal advancement came with the introduction of Transformer architectures, which leveraged self-attention mechanisms to process sequential data with unprecedented effectiveness [8]. Models such as AlphaFold for protein structure prediction and DNABERT for genomic sequence analysis achieved landmark results that surpassed previous methods [8]. These architectures formed the foundation for the next evolutionary step: the development of foundation models that could generalize across diverse biological domains and tasks [8] [9].

The Emergence of Foundation Models

Foundation models represent the current frontier in AI for bioinformatics, characterized by their large-scale pretraining on extensive datasets and adaptability to numerous downstream applications [9] [10]. These models overcome the fundamental limitation of earlier approaches—their narrow specialization—by learning generalizable patterns from massive, diverse biological data corpora [10]. The defining features of foundation models include: (1) training on extremely large and diverse datasets to capture universal patterns, (2) effective architectures based on transformers that model complex dependencies, and (3) the ability to fine-tune or prompt the model for new tasks, transferring learned knowledge to improve performance on target applications [10]. This paradigm shift has enabled researchers to address biological questions that previously required specialized models and extensive retraining for each new task [9].

Table 1: Quantitative Performance of AI Applications in Bioinformatics

| Application Domain | AI Model/Method | Performance Metrics | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure Prediction | AlphaFold | Median 0.96 Å on CASP14 | Near-atomic accuracy [8] |

| Single-Cell Modeling | scFMs | AvgBIO 0.82 | Robust cellular representation [8] |

| Protein Design | AI-based Design | Up to 92% success rate | High precision engineering [8] |

| Cancer Detection | AI Diagnostics | Area Under Curve (AUC) 0.93 | Sensitive disease identification [8] |

| Genomic Data Curation | GPT-4 | 97% correct categorization | Efficient data extraction [11] |

| Quantitative Trait Loci Extraction | GPT-4 | 61% of marker-trait associations | Automated literature mining [11] |

Technical Architectures and Methodological Innovations

Transformer Architectures in Biological Foundation Models

The transformer architecture serves as the fundamental backbone for most contemporary foundation models in bioinformatics [10]. Originally developed for natural language processing, transformers utilize attention mechanisms that allow the model to learn and weight relationships between any pair of input tokens [10]. In biological applications, this enables models to determine which genes, sequences, or structural elements are most informative for specific analyses. The self-attention mechanism is particularly powerful for biological data because it can capture long-range dependencies and complex interactions that simpler architectures might miss [10]. For genomic sequences, this means identifying regulatory elements that influence distant genes; for protein structures, it means recognizing how amino acid interactions dictate folding patterns [10]. The adaptability of transformer architectures has facilitated their application across diverse biological data types, including DNA sequences, protein structures, and single-cell transcriptomes [9] [10].

Single-Cell Foundation Models: A Case Study in Architectural Innovation

Single-cell foundation models (scFMs) exemplify the sophisticated architectural innovations driving AI evolution in bioinformatics [10] [12]. These models face the unique challenge of processing non-sequential data—gene expression profiles lack the inherent ordering of words in a sentence [10]. To address this, researchers have developed innovative tokenization strategies that convert single-cell data into sequences that transformers can process effectively [10]. Common approaches include ranking genes within each cell by expression levels or partitioning genes into bins based on expression values [10]. The input layers of scFMs typically comprise three components: gene embeddings (analogous to word embeddings), value embeddings representing expression levels, and positional embeddings that provide information about gene order or rank [12]. Models such as scBERT employ bidirectional encoder architectures, while scGPT uses decoder-inspired architectures with unidirectional masked self-attention [10]. These architectural variations represent different strategies for capturing the complex relationships in single-cell data, with each offering distinct advantages for specific analytical tasks [10] [12].

Diagram 1: Single-Cell Foundation Model Architecture

Evolutionary-Informed AI: Integrating Phylogenetic Knowledge

A recent innovation in biological AI involves explicitly incorporating evolutionary relationships into model architectures [13]. Traditional AI algorithms often struggle to analyze biological data through an evolutionary lens because they lack prior knowledge about phylogenetic trees and get confused by random patterns [13]. Researchers have addressed this limitation by developing neural networks that incorporate prior knowledge of species ancestry trees during training [13]. This approach classifies groups of four species into presumably correct ancestry trees, enabling the AI to identify patterns that have evolved throughout evolutionary history [13]. The method works not only for genetic sequence data but also for other data types, including images and structural patterns of biomolecules from various species [13]. This represents a significant advancement toward creating AI systems that reason about biological data in ways that align with established biological principles, moving beyond pattern recognition to embody deeper conceptual understanding of evolutionary processes [13].

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking Frameworks

Benchmarking Single-Cell Foundation Models

Comprehensive benchmarking studies have emerged to evaluate the performance of scFMs under realistic biological scenarios [12]. These evaluations typically assess models across multiple task categories, including gene-level tasks (tissue specificity prediction, Gene Ontology term prediction) and cell-level tasks (dataset integration, cell type annotation, cancer cell identification, drug sensitivity prediction) [12]. Performance is measured using a combination of traditional metrics and novel biology-informed approaches such as scGraph-OntoRWR, which measures the consistency of cell type relationships captured by scFMs with prior biological knowledge [12]. The benchmarking pipeline involves extracting zero-shot gene and cell embeddings from pretrained models without additional fine-tuning, then evaluating these representations on diverse datasets that challenge models with real-world complexities like batch effects, novel cell types, and cross-tissue heterogeneity [12]. This rigorous evaluation framework provides crucial insights into model strengths and limitations, guiding researchers in selecting appropriate tools for specific biological questions.

Table 2: Single-Cell Foundation Model Performance Benchmarking

| Model | Architecture Type | Batch Integration | Cell Type Annotation | Biological Relevance | Computational Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geneformer | Transformer-based | High | Medium | High | Medium |

| scGPT | GPT-inspired | High | High | High | Low |

| scBERT | BERT-like | Medium | High | Medium | High |

| UCE | Custom encoder | Medium | Medium | High | Medium |

| scFoundation | Transformer-based | High | High | High | Low |

| LangCell | Language model-inspired | High | Medium | Medium | Medium |

Evaluating Large Language Models for Biocuration

The application of large language models (LLMs) to biological curation tasks represents another important domain where rigorous experimental protocols have been developed [11]. These protocols typically involve comparing LLM performance against human curators for specific tasks such as categorizing manuscripts, extracting traits, and identifying marker-trait associations [11]. In one representative study, researchers used retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) to enhance GPT models with domain-specific knowledge, then evaluated their performance on curating wheat and barley genetics literature [11]. The experimental workflow involved parsing scientific PDFs, splitting text into overlapping chunks, generating vector embeddings, and querying the system with biologically relevant prompts [11]. Performance was assessed using precision metrics comparing LLM extractions against manual curation by PhD-level biologists [11]. This approach demonstrated that GPT-4 could correctly categorize manuscripts 97% of the time, extract 80% of traits, and identify 61% of marker-trait associations, highlighting both the potential and limitations of current LLMs for biological curation tasks [11].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for scFM Research

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Single-Cell Foundation Model Development

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | CZ CELLxGENE, Human Cell Atlas, NCBI GEO, PanglaoDB | Provide standardized, annotated single-cell datasets for model training [10] |

| Processing Tools | Scipy, Scikit-learn, Scanpy | Enable data preprocessing, normalization, and quality control [12] |

| Model Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, Hugging Face Transformers | Provide foundational architectures for developing and training scFMs [10] [12] |

| Benchmarking Platforms | Custom evaluation pipelines, scGraph-OntoRWR metric | Enable standardized performance assessment and comparison [12] |

| Specialized Compute | GPU clusters, Cloud computing resources | Handle computational intensity of training and fine-tuning large models [10] |

Applications and Impact Across Biological Domains

Genomic Sequence Analysis and Interpretation

Foundation models have revolutionized genomic sequence analysis by enabling researchers to identify evolutionarily conserved regions, mutation patterns, and critical functional domains directly from sequence information [8]. Language-inspired models treat DNA sequences as textual data, applying transformer architectures to predict regulatory elements, transcription factor binding sites, and variant effects [8] [9]. These approaches have demonstrated remarkable success in connecting sequence variations to functional consequences, providing insights into disease mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets [8]. The application of foundation models to genomics has moved beyond simple pattern recognition to enable predictive modeling of complex genotype-phenotype relationships, accelerating discovery in functional genomics and personalized medicine [8] [9].

Protein Structure Prediction and Design

The most celebrated success of AI in bioinformatics remains the breakthrough in protein structure prediction achieved by AlphaFold and related systems [8]. These models demonstrated median accuracy of 0.96 Å on the CASP14 assessment, approaching near-atomic resolution directly from amino acid sequences [8]. This achievement represented a decades-old challenge in structural biology and has fundamentally changed how researchers approach protein characterization and engineering [8]. Beyond structure prediction, foundation models have enabled innovative approaches to protein design, with AI-driven methods achieving success rates up to 92% for designing proteins with specific functions or properties [8]. These capabilities are accelerating therapeutic development, enzyme engineering, and the creation of novel biomaterials, demonstrating how foundation models can transition from analytical tools to generative platforms for biological innovation [8] [9].

Drug Discovery and Development

Foundation models are transforming drug discovery by enabling more efficient target identification, compound screening, and toxicity prediction [9]. These models integrate diverse data types—including genomic sequences, protein structures, chemical properties, and clinical outcomes—to identify promising therapeutic candidates and predict their behavior in biological systems [9]. The ability to pretrain on massive unlabeled datasets then fine-tune for specific discovery tasks has proven particularly valuable in drug development, where labeled data is often limited and expensive to acquire [9]. Foundation models can identify novel drug targets, predict drug-drug interactions, and optimize compound properties, significantly reducing the time and cost associated with traditional discovery pipelines [9]. As these models continue to improve, they promise to accelerate the development of personalized therapeutics tailored to individual genetic profiles and disease characteristics [8] [9].

Diagram 2: Foundation Models in Drug Discovery Workflow

Challenges and Future Directions

Technical and Interpretability Limitations

Despite remarkable progress, foundation models in bioinformatics face significant technical challenges that limit their widespread adoption [8] [10] [14]. Massive and heterogeneous biological datasets frequently contain inherent noise, biases, and class imbalance issues that can compromise model performance and generalizability [8]. Biological sequences, particularly from higher organisms, often exceed the context windows of current transformer architectures, complicating effective modeling of long-range dependencies [8]. Perhaps most critically, explainability and reproducibility of AI models face heightened scrutiny from biological and medical communities [8] [14]. Black-box AI models raise concerns about decision transparency and user confidence, driving increased demand for explainable AI (XAI) approaches that can provide biological insights into model predictions [14]. Current research focuses on developing interpretation methods that reveal which features and patterns drive model decisions, enabling researchers to validate predictions against biological knowledge and generate testable hypotheses [14].

Data Quality and Integration Challenges

The effectiveness of foundation models depends critically on the quality and diversity of their training data [10]. Single-cell genomics exemplifies these challenges, as models must contend with datasets exhibiting varying sequencing depth, batch effects, technical noise, and inconsistent processing steps across different studies and platforms [10]. Assembling high-quality, non-redundant datasets for pretraining requires careful selection, filtering, and balancing of dataset compositions [10]. Furthermore, integrating multimodal data—such as combining genomic sequences, protein structures, medical imaging, and clinical text—presents additional complexities related to data alignment, representation learning, and cross-modal inference [8] [10]. Future advancements will require not only improved model architectures but also better data standardization, curation practices, and integration frameworks that preserve biological signals while mitigating technical artifacts [10].

Ethical Considerations and Future Trajectories

The expanding capabilities of foundation models in bioinformatics raise important ethical considerations, particularly regarding privacy when handling sensitive genomic and clinical patient data [8]. Establishing rigorous standards and frameworks for responsible AI deployment is essential as these models become integrated into healthcare and research settings [8]. Looking forward, researchers anticipate several promising directions for the field, including large-scale data mining across expanded biological corpora, improved cross-domain model generalization, innovations in drug design and personalized medicine, and the establishment of more open and collaborative research ecosystems [8] [15]. The integration of evolutionary perspectives represents another exciting frontier, enabling models to reason about biological data through phylogenetic relationships rather than just statistical patterns [13]. As these advancements mature, foundation models will increasingly serve not merely as analytical tools but as collaborative partners in biological discovery, helping researchers formulate hypotheses, design experiments, and interpret results across the vast complexity of living systems [8] [9] [10].

Foundation Models (FMs), large-scale machine learning models pre-trained on extensive datasets, are revolutionizing data interpretation across diverse scientific fields through self-supervised learning [10]. In bioinformatics, these models demonstrate remarkable proficiency in managing large-scale, unlabeled biological datasets, effectively addressing historical challenges related to data integration and analysis [9]. The adaptability of FMs enables their application to various downstream tasks in computational biology, consistently achieving high accuracy in representing complex biological entities and processes [9] [6].

This technical guide examines the four core architectural types of foundation models—Language, Vision, Graph, and Multimodal—within the specific context of bioinformatics research. We provide a comprehensive analysis of each architecture's fundamental principles, representative models, biological applications, and experimental methodologies. The content is structured to serve researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to understand and implement these transformative technologies in their computational workflows.

Core Foundation Model Architectures in Bioinformatics

Foundation models in bioinformatics leverage different architectural paradigms to process various types of biological data. The table below summarizes the four core types, their data handling characteristics, primary biological applications, and specific model examples.

Table 1: Core Foundation Model Architectures in Bioinformatics

| Architecture Type | Primary Data Handling | Key Biological Applications | Representative Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Language FMs [9] | Sequential data (e.g., DNA, protein sequences) [6] | Genome annotation, variant effect prediction, regulatory element identification [6] | DNABERT, Geneformer, scGPT [6] [10] |

| Vision FMs [9] | Image-based data (e.g., medical scans, protein structures) [16] | Medical image analysis (X-ray, MRI), protein structure prediction, histopathology [6] [16] | AlphaFold, CONCH [6] [16] |

| Graph FMs [9] | Graph-structured data (e.g., molecular structures, interaction networks) | Drug discovery, molecular property prediction, knowledge graph reasoning [6] | TxGNN, Novae [6] |

| Multimodal FMs [9] | Integrated multiple data types (e.g., text + images, multi-omics) [16] | Spatial transcriptomics, clinical diagnostics (imaging + EHR), multi-omics integration [6] [16] [10] | Nicheformer, MLLM4TS [17] [6] |

Language Foundation Models

Language FMs process biological sequences—such as DNA, RNA, and proteins—as textual data, where discrete biological elements (nucleotides, amino acids) are treated as tokens or "words" in a biological language [18]. These models typically employ transformer architectures with self-attention mechanisms to capture contextual relationships within sequences [10].

Key Architectures and Pre-training Strategies:

- Encoder-based Models (e.g., BERT-style): Use bidirectional attention to learn from the entire sequence context simultaneously. Pre-training often involves masked language modeling, where random tokens in the input sequence are masked and the model learns to predict them based on surrounding context [10] [18].

- Decoder-based Models (e.g., GPT-style): Employ unidirectional masked self-attention, iteratively predicting next elements in a sequence conditioned on previous elements. This approach is particularly effective for generative tasks [10].

Bioinformatics Applications and Experimental Protocols:

- Variant Effect Prediction: Models like Enformer are trained to predict the effects of non-coding DNA variants on gene expression by analyzing sequence context and long-range genomic interactions (up to 100kb) [6]. Experimental validation typically involves comparing predictions with functional genomics data from assays like ChIP-seq or STARR-seq.

- Single-Cell Analysis: scGPT is pre-trained on approximately 30 million single-cell transcriptomes to learn gene-gene interaction patterns [6]. For cell type annotation, the protocol involves:

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize raw count data and tokenize gene expression values.

- Embedding Generation: Feed tokenized cells to scGPT to obtain latent embeddings.

- Fine-tuning: Add a classification head and fine-tune on a smaller, labeled dataset using cross-entropy loss.

- Validation: Compare predicted cell types against manual annotations or marker genes.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Language FM Experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Reference Genome (e.g., hg38) [19] | Standardized genomic coordinate system for alignment and variant calling. |

| Pre-trained Model Weights [6] [18] | Foundation for transfer learning, eliminating need for expensive pre-training. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster [19] | Provides computational capacity for training and fine-tuning large models. |

| Single-Cell Datasets (e.g., CZ CELLxGENE) [10] | Curated, annotated data for model fine-tuning and validation. |

| Containerized Software (Docker/Singularity) [19] | Ensures computational reproducibility across different environments. |

Vision Foundation Models

Vision FMs process and interpret image-based biological data, including medical scans, protein structures, and cellular imagery. These models leverage convolutional neural networks and vision transformers (ViTs) to extract hierarchical visual features [16].

Key Architectures:

- Vision Encoders: Models like CLIP (Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training) use contrastive learning to align visual data with textual descriptions, creating a shared representation space [16].

- Protein Structure Prediction: AlphaFold employs novel neural architectures to predict 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences with near-experimental accuracy [6].

Bioinformatics Applications and Experimental Protocols:

- Medical Image Analysis: In radiology, MLLMs integrate diverse imaging modalities (CT, MRI, X-ray) with textual clinical data for tasks like automated radiology report generation and visual question answering [16]. The standard workflow involves:

- Image Preprocessing: Standardize image dimensions, orientation, and intensity values.

- Feature Extraction: Process images through a pre-trained vision encoder (e.g., ViT) to obtain visual embeddings.

- Multimodal Fusion: Align visual embeddings with text embeddings using a multimodal connector.

- Task-Specific Heads: Generate diagnostic reports or answers using the fused representations.

- Time-Series Analysis: The MLLM4TS framework converts multivariate time-series data into color-coded line-plot images, enabling anomaly detection and forecasting through visual pattern recognition [17].

Graph Foundation Models

Graph FMs specialize in processing graph-structured biological data, including molecular structures, protein-protein interaction networks, and knowledge graphs. These models use graph neural networks (GNNs) to capture topological relationships between biological entities [6].

Bioinformatics Applications and Experimental Protocols:

- Drug Discovery: TxGNN is trained on medical knowledge graphs to identify potential new purposes for existing drugs by traversing relationships between compounds, diseases, and biological pathways [6]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Knowledge Graph Construction: Integrate data from sources like DrugBank, STITCH, and clinical trials.

- Message Passing: Use graph attention networks to propagate information between connected nodes.

- Link Prediction: Score potential drug-disease pairs using learned node embeddings.

- Validation: Compare predictions against known off-label uses or conduct retrospective clinical validation.

- Satial Biology Analysis: Novae uses graph-based learning to correct for batch effects in spatial transcriptomics data, enabling more accurate comparison of spatial domains across different samples and experiments [6].

Multimodal Foundation Models

Multimodal FMs represent the most advanced architecture, capable of processing and integrating multiple data types simultaneously. These models align representations from different modalities into a shared semantic space, enabling complex cross-modal reasoning [16].

Key Architectural Components:

- Modality-Specific Encoders: Transform raw data from each modality (image, text, etc.) into meaningful representations [16].

- Multimodal Connector: Bridges the modality gap by mapping non-textual data to representations interpretable by Large Language Models (LLMs). Connector types include:

- Projection-based: Employ Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) to transform visual data to align with language representations [16].

- Query-based: Utilize trainable 'query tokens' to extract salient visual details [16].

- Fusion-based: Facilitate feature-level integration through cross-attention mechanisms [16].

- Pre-trained LLM Backbone: Serves as the cognitive engine, providing reasoning capabilities without requiring additional fine-tuning for multimodal inputs [16].

Training Strategies: Multimodal FMs are typically developed through three sequential stages [16]:

- Pre-training: The multimodal connector learns to align visual and textual representations using autoregressive captioning on image-text pairs.

- Instruction Tuning: The model is fine-tuned with diverse natural language instructions and multimodal inputs to reliably follow complex directives.

- Alignment Tuning: The model's outputs are optimized to better reflect human preferences through reinforcement learning from human feedback.

Bioinformatics Applications and Experimental Protocols:

- Spatial Transcriptomics: Nicheformer is trained on both dissociated single-cell transcriptomics data (>57 million cells) and spatially-resolved transcriptomics data (>53 million cells) to make context-specific predictions about cellular microenvironments [6]. The protocol involves:

- Data Alignment: Map dissociated cells to spatial coordinates using transfer learning.

- Contextual Prediction: Infer spatial organization and cell-cell communication patterns.

- Biological Validation: Validate predictions using techniques like multiplexed FISH or immunohistochemistry.

- Clinical Diagnostics: MLLMs in radiology integrate imaging data with clinical notes and laboratory results to generate comprehensive diagnostic reports [16]. Implementation requires robust validation against clinician interpretations and monitoring for hallucinated findings.

Foundation Models Classification in Bioinformatics

Implementation and Workflow Management

Successfully implementing foundation models in bioinformatics requires robust computational infrastructure and standardized workflow management. Nextflow and nf-core provide a critical framework for creating reproducible, scalable, and portable analysis pipelines [20].

Essential Implementation Rules:

- Strategic Planning: Align computational infrastructure with institutional priorities and research needs, identifying available HPC resources and existing knowledge gaps [20].

- Workflow Standardization: Transition from ad hoc scripts to containerized Nextflow pipelines, ensuring reproducibility through version control and standardized file formats [19] [20].

- Containerized Environments: Encapsulate software in Docker or Singularity containers to maintain consistency across different computational environments [19].

- Quality Assurance: Implement comprehensive testing strategies at unit, integration, system, and end-to-end levels, validating pipelines against standard truth sets like GIAB for germline variant calling [19].

- Community Engagement: Facilitate continuous learning through seminars, hackathons, and collaborative platforms to build sustainable bioinformatics capacity [20].

Bioinformatics Analysis Workflow with Foundation Models

Future Perspectives and Challenges

Despite their transformative potential, foundation models in bioinformatics face several significant challenges that must be addressed for widespread clinical and research adoption [21] [16] [10].

Critical Challenges:

- Data Quality and Availability: Limited access to large-scale, high-quality multimodal datasets, coupled with issues of batch effects, technical noise, and inconsistent processing steps across studies [16] [10].

- Computational Intensity: Substantial computational resources required for training and fine-tuning, creating barriers for resource-limited institutions [10].

- Interpretability and Transparency: Difficulty in interpreting the biological relevance of latent embeddings and model representations, particularly in clinical settings where decision-making processes must be explainable [16] [10].

- Hallucination and Reliability: Risks of hallucinated findings in generative models, requiring robust validation frameworks and human oversight [16].

- Security and Privacy: Ensuring data security, patient privacy, and ethical use of sensitive clinical information, particularly when using cloud-based resources [21].

Future Directions:

- Region-Grounded Reasoning: Developing models that can link outputs to specific regions in images or genomic sequences to enhance interpretability [16].

- Robust Foundation Models: Creating larger models pre-trained on comprehensive medical datasets specifically designed for healthcare applications [16].

- Integration Strategies: Establishing safe and effective protocols for integrating FMs into clinical practice, including validation standards and regulatory frameworks [16].

- Cross-Modal Generalization: Enhancing model capabilities to transfer knowledge across different biological modalities and species [10].

As these challenges are systematically addressed, foundation models are poised to become indispensable tools in bioinformatics, enabling deeper insights into cellular function, disease mechanisms, and therapeutic development [10]. Their continued evolution will likely establish the theoretical and practical foundation for ongoing innovation in molecular biology and precision medicine [9].

Foundation Models (FMs) are revolutionizing bioinformatics by providing a unified framework to interpret complex biological systems. Trained on massive-scale datasets through self-supervised learning, these models learn fundamental principles that can be adapted to a wide range of downstream tasks with minimal fine-tuning. Their capacity to capture intricate patterns and relationships within biological data makes them particularly suited for the high-dimensional, sparse, and heterogeneous nature of modern biological datasets. This technical guide details the core biological data types—DNA, RNA, proteins, and single-cell multi-omics—that form the corpus for these powerful models, outlining the specific FMs developed for each, their operational mechanisms, and their transformative applications in biomedical research and drug development.

DNA and Genomic Foundation Models

Genomic FMs are trained on DNA sequence data to understand the regulatory language of the genome and predict the functional impact of genetic variation.

Core Data Characteristics and Pretraining

Genomic FMs process DNA sequences as strings of nucleotides (A, C, G, T). Tokenization typically involves dividing long sequences into shorter k-mers (contiguous sequences of k nucleotides), which serve as the basic input tokens analogous to words in a sentence [3]. These models are pretrained on large-scale datasets from public repositories like the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) using self-supervised objectives, most commonly Masked Language Modeling (MLM), where random tokens in the input sequence are masked and the model is trained to predict them based on context [3].

Representative Models and Methodologies

Table 1: Foundation Models for DNA Sequence Analysis

| Model Name | Architecture | Pretraining Data | Key Functionalities |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNABERT [6] | Transformer Encoder (BERT) | DNA sequences | Predicts regulatory regions (promoters, transcription factor binding sites), splice sites, and non-coding variant effects. |

| Enformer [6] | Deep Learning (CNN + Transformer) | DNA sequences with long-range context | Predicts the effects of non-coding DNA on gene expression, incorporating long-range interactions up to 100 kilobases. |

| DeepSEA [6] | Deep Learning (CNN) | Non-coding genomic variants | Predicts the chromatin and epigenetic effects of non-coding genomic variants. |

Experimental Protocol for Variant Effect Prediction

A standard protocol for using DNA FMs to predict the pathogenicity of non-coding variants involves:

- Sequence Input: Extract a reference DNA sequence window (e.g., 1 kb) centered on the variant of interest.

- Variant Representation: Generate an alternative sequence by introducing the specific nucleotide change.

- Model Inference: Pass both reference and alternative sequences through the FM (e.g., Enformer or DeepSEA) to obtain predictions for chromatin features (e.g., histone marks, transcription factor binding) or gene expression levels.

- Effect Scoring: Calculate a prediction difference score (e.g., Euclidean distance between the model's outputs for the two sequences). A larger difference indicates a higher predicted functional impact [6].

RNA and Transcriptomic Foundation Models

Transcriptomic FMs focus on gene expression data, particularly from single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), to characterize cellular heterogeneity, states, and functions.

Core Data Characteristics and Pretraining

The input data is a cell-by-gene matrix of expression counts. A significant challenge is the non-sequential nature of this data; genes have no inherent order. To apply transformer architectures, models use various tokenization strategies:

- Rank-based: Genes are ordered by their expression level within each cell, and the top-k genes form the input sequence [10] [22].

- Binning: Genes are partitioned into bins based on their expression values [10].

- Normalized Counts: Some models simply use normalized counts without complex ranking [10]. Each gene is typically represented by a token embedding that combines a gene identifier and its expression value. Special tokens for cell identity or batch information can be prepended [10].

Representative Models and Methodologies

Table 2: Foundation Models for Single-Cell Transcriptomics

| Model Name | Architecture | Pretraining Data | Key Functionalities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geneformer [22] [6] | Transformer Encoder | ~30-95 million single-cell transcriptomes | Predicts tissue-specific gene network dynamics, cell type annotation, response to perturbation. |

| scGPT [10] [22] [6] | Transformer Decoder (GPT-style) | ~30 million cells from scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, CITE-seq | Cell type annotation, gene network inference, multi-omics data integration, and generative modeling. |

| scVI [6] [23] | Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Single-cell gene expression data | Dimensionality reduction, visualization, clustering, and differential expression analysis. |

Experimental Protocol for Cell Type Annotation

A common application of transcriptomic FMs is annotating cell types in a new scRNA-seq dataset:

- Data Preprocessing: The query dataset is filtered and normalized. Gene expression profiles are converted into a sequence of tokens according to the FM's specific tokenization scheme (e.g., top 2,048 ranked genes for Geneformer) [22].

- Latent Embedding: The tokenized sequences are passed through the pretrained FM to generate a low-dimensional latent embedding for each cell.

- Annotation:

Figure 1: Workflow for processing single-cell RNA-seq data through a foundation model for tasks like cell type annotation.

Protein and Structural Foundation Models

Protein FMs interpret amino acid sequences and, in some cases, predict their three-dimensional structures, which is critical for understanding function and enabling drug design.

Core Data Characteristics and Pretraining

These models use amino acid sequences (strings of 20 standard letters) as primary input. Tokenization is straightforward, with each amino acid treated as a discrete token. Pretraining leverages large public databases like UniProt and can involve multiple self-supervised tasks, including MLM and predicting whether a protein is native-like [3]. Advanced models also incorporate physical and evolutionary constraints.

Representative Models and Methodologies

- AlphaFold: A deep learning model that uses neural networks to predict 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences with near-experimental accuracy. Its successor, AlphaFold3, extends this capability to complexes of proteins with other biomolecules [6].

- ESM (Evolutionary Scale Modeling): A series of transformer-based protein language models pretrained on millions of protein sequences. They generate informative representations that can be used for predicting structure, function, and the effects of mutations without an explicit multiple sequence alignment [3].

Experimental Protocol for Protein Structure Prediction

Using AlphaFold as a paradigm:

- Input Preparation: The target amino acid sequence is provided. A multiple sequence alignment (MSA) is generated for the target using databases of known protein sequences to infer evolutionary constraints.

- Model Inference: The target sequence and its MSA are fed into AlphaFold's neural network architecture.

- Structure Generation: The model outputs a 3D atomic coordinates file (PDB format) representing the most likely structure, along with per-residue confidence estimates (pLDDT scores) [6].

Single-Cell Multi-omics Foundation Models

This frontier in biological FMs aims to achieve a holistic view of the cell by jointly analyzing multiple molecular modalities measured within the same cell.

Core Data Characteristics and Pretraining

Single-cell multi-omics data encompasses simultaneously measured transcriptomic (RNA), epigenomic (e.g., scATAC-seq for chromatin accessibility), and proteomic (e.g., antibody-derived tags, ADTs) profiles [24] [25]. The key challenge for FMs is the "diagonal integration" of these distinct feature sets. Models are trained on datasets from technologies like CITE-seq (RNA + protein) and SHARE-seq (RNA + chromatin accessibility) [24] [25]. They must handle weak or limited correlations between some modalities (e.g., mRNA levels and protein abundance) and data sparsity [24].

Representative Models and Integration Strategies

Table 3: Foundation Models and Deep Learning Approaches for Single-Cell Multi-omics Integration

| Model Name | Architecture | Key Integration Strategy | Modalities Handled |

|---|---|---|---|

| scMODAL [24] | Neural Networks + Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) | Aligns cell embeddings using known feature links and adversarial learning. | scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, Proteomics |

| scGPT [10] [25] | Transformer | Uses modality-specific tokens and a unified transformer to process and integrate data. | scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, CITE-seq, Spatial |

| scMaui [23] | Variational Autoencoder (Product-of-Experts) | Combines marginal distributions of different modalities into a joint latent representation. Handles batch effects and missing data. | Multiple, flexible assays |

| Nicheformer [6] | Transformer | Trained on both dissociated and spatial transcriptomics data to contextualize cells within their tissue microenvironment. | scRNA-seq, Spatial Transcriptomics |

Experimental Protocol for Multi-omics Data Integration

A standard workflow using a model like scMODAL or scMaui involves:

- Input Data Preparation: Provide cell-by-feature matrices for each modality (e.g.,

X_rna,X_adt). Compile prior knowledge of linked features (e.g., a gene and its protein product) into paired matrices [24]. - Model Training: The FM (e.g., an encoder network) is trained to project all cells into a shared latent space. Training employs several techniques:

- Adversarial Learning: A discriminator network ensures the latent distributions of different modalities are indistinguishable, removing unwanted technical variation [24].

- Anchor-Based Guidance: Mutual nearest neighbors (MNN) calculated on linked features are used to pull corresponding cells together in the latent space [24].

- Topology Preservation: Regularization terms ensure the intrinsic geometric structure of each dataset is preserved [24].

- Downstream Analysis: The output is a unified, low-dimensional embedding of all cells. This embedding is used for clustering to identify novel cell states, trajectory inference, and cross-modality feature imputation [24] [23].

Figure 2: A generalized architecture for single-cell multi-omics integration using foundation models, showing key components like adversarial learning and mutual nearest neighbor (MNN) guidance.

Table 4: Essential Resources for Working with Biological Foundation Models

| Resource Category | Item | Function & Utility |

|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | NCBI GEO / SRA [10] | Primary archives for raw and processed genomic and transcriptomic sequencing data used for pretraining and fine-tuning. |

| CZ CELLxGENE [10] [22] | Curated platform providing unified access to millions of annotated single-cell datasets. | |

| Software & Tools | scvi-tools [6] | A Python package providing scalable implementations of probabilistic models for single-cell omics data, including scVI. |

| Seurat [24] [23] | An R toolkit widely used for single-cell multi-omics analysis, often used as a baseline for comparison. | |

| Pretrained Models | Hugging Face / Model Zoos | Platforms where pretrained FMs (e.g., scGPT, Geneformer) are often hosted for community use, enabling transfer learning. |

| Benchmarking Studies | Comparative Reviews [22] | Independent evaluations that provide holistic rankings of FM performance across diverse tasks, guiding model selection. |

Foundation models represent a paradigm shift in computational biology, moving from task-specific algorithms to general-purpose models that learn the underlying language of DNA, RNA, proteins, and cellular systems. The integration of multiple data types, particularly through single-cell multi-omics FMs, is paving the way for a more comprehensive and predictive understanding of cellular function in health and disease. As these models continue to evolve, addressing challenges such as data quality, interpretability, and computational cost will be crucial. However, their current capacity to integrate heterogeneous data, generate novel biological hypotheses, and provide actionable insights for drug discovery already marks them as indispensable tools in the modern biologist's and drug developer's arsenal.

The emergence of foundation models has catalyzed a paradigm shift in bioinformatics, moving from task-specific models to general-purpose tools trained on massive, unlabeled datasets. This approach, known as pretraining, allows models to learn fundamental biological principles directly from data without manual annotation. By processing diverse biological sequences and structures through self-supervised learning, these models develop a comprehensive understanding of biological "grammar" that can be efficiently adapted to specialized tasks. The pretraining paradigm has demonstrated remarkable success across genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics, and bioimaging, enabling breakthroughs in disease prediction, drug discovery, and functional annotation. This technical guide examines the core methodologies, experimental protocols, and implementations of pretraining across biological domains, providing researchers with a comprehensive framework for leveraging unlabeled biological data.

Core Principles of Biological Pretraining

Conceptual Foundation and Biological Rationale

Pretraining in biological systems operates on the principle that biological sequences—whether DNA, RNA, proteins, or cellular images—contain inherent patterns and relationships that can be learned through self-supervised objectives without explicit labeling. This approach mirrors how large language models learn statistical regularities in human language, but applied to the "language of life." The fundamental insight is that the structure-function relationship in biology is encoded in sequences and images through evolutionary constraints and biophysical principles. By training on vast corpora of unlabeled data, models can internalize these constraints and develop representations that capture biologically meaningful features, from conserved protein motifs to regulatory DNA elements [26] [27].

The biological rationale stems from the observation that similar sequences often share similar functions across organisms, and that cellular images contain reproducible patterns corresponding to biological states. Pretraining enables models to capture these transferable principles, creating a foundation of biological knowledge that can be fine-tuned for specific applications. This is particularly valuable in biology where labeled data is scarce and expensive to generate, while unlabeled data exists in abundance through public repositories and large-scale sequencing initiatives [28] [10].

Key Architectural Components

Table 1: Core Architectural Components of Biological Foundation Models

| Component | Function | Implementation Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Tokenization | Converts raw biological data into discrete units | k-mer splitting for DNA (e.g., "ATGCGA"), gene-level tokenization for expression data [26] |

| Embedding Layer | Maps tokens to dense vector representations | Learned embeddings for k-mers or gene identifiers [10] |

| Transformer Backbone | Captures long-range dependencies in sequences | Encoder-only (BERT-style), Decoder-only (GPT-style), or Encoder-Decoder architectures [26] [10] |

| Attention Mechanism | Models relationships between all positions in sequence | Multi-head self-attention with biological positional encodings [10] |

| Pretraining Head | Performs self-supervised learning objectives | Masked language modeling, next token prediction, contrastive learning [26] |

The transformer architecture serves as the foundational backbone for most biological pretraining approaches, adapted to handle domain-specific challenges. Unlike natural language, biological sequences often lack inherent ordering—genes in a cell have no natural sequence, yet transformers require ordered input. Solutions include ranking genes by expression levels or using expression-based binning to create deterministic sequences from non-sequential data [10]. Positional encodings are adapted to represent biological context, such as genomic coordinates or cellular neighborhoods.

Domain-Specific Implementation Frameworks

Genomic Sequence Pretraining

Genomic pretraining treats DNA nucleotides as a vocabulary and sequences as texts to be understood. The standard workflow involves tokenizing DNA sequences into k-mers (typically 3-6 nucleotides), embedding these tokens, and processing through transformer layers. Pretraining tasks include masked language modeling where random nucleotide spans are masked and predicted based on context, or next nucleotide prediction in autoregressive frameworks [26]. Models like DNABERT and Nucleotide Transformer have demonstrated that this approach captures regulatory elements, conservation patterns, and functional annotations without supervision.

A critical advancement is the development of cross-species pretraining, where models trained on human genomic datasets transfer effectively to other organisms. Research has shown that models pretrained on human data then fine-tuned on diverse tissues and species achieve high prediction accuracy (Pearson correlation up to 0.8) while significantly reducing computational costs compared to training from scratch [28]. This demonstrates that fundamental genomic principles are conserved across species and can be transferred through pretraining.

Single-Cell Multi-Omics Pretraining

Single-cell foundation models (scFMs) represent a transformative approach for analyzing cellular heterogeneity at scale. These models treat individual cells as "documents" and genes or genomic features as "words," learning to represent cellular states and regulatory relationships through pretraining on millions of single-cell transcriptomes [10]. The tokenization challenge is particularly acute in single-cell data, where gene expression profiles lack natural ordering. Solutions include ranking genes by expression value, binning expression levels, or using deterministic algorithms to create sequence structure from inherently non-sequential data.

Architecturally, scFMs employ both encoder-style models like scBERT for classification tasks and decoder-style models like scGPT for generation. Pretraining strategies include masked gene prediction, where random portions of the gene expression vector are masked and reconstructed based on context, enabling the model to learn gene-gene correlations and regulatory networks [10]. These models demonstrate remarkable transfer learning capabilities, adapting to novel cell types and conditions with minimal fine-tuning.

Table 2: Single-Cell Foundation Models and Their Applications

| Model | Architecture | Pretraining Data | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| scBERT [10] | BERT-style Encoder | ~30M single-cell transcriptomes | Cell type annotation, novel cell type discovery |

| scGPT [10] | GPT-style Decoder | Multi-omics single-cell data | Cell state generation, perturbation response prediction |

| GeneLLM [29] | Encoder-Decoder | cfDNA/cfRNA sequencing data | Preterm birth risk prediction, multi-omics integration |

Bioimaging Pretraining

CytoImageNet exemplifies the pretraining paradigm for biological images, applying ImageNet-inspired approaches to microscopy data. This large-scale dataset contains ~890,000 weakly labeled images across 894 classes, compiled from 40 publicly available datasets [30]. Unlike natural images, microscopy images require specialized preprocessing, including channel normalization, artifact filtering, and multi-scale cropping to enhance diversity.

The pretraining workflow involves training convolutional networks (e.g., EfficientNetB0) to classify images using weak labels derived from metadata (e.g., organism, cell type, phenotype). Despite relatively low classification accuracy (11.32% validation), the learned features transfer effectively to downstream microscopy classification tasks, complementing ImageNet-pretrained features [30]. This demonstrates that domain-specific pretraining captures biologically relevant features not present in natural image distributions.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Data Curation and Preprocessing

High-quality data curation is fundamental to successful biological pretraining. The CytoImageNet protocol illustrates comprehensive data processing: manual annotation of 65 datasets with dataset-specific processing to handle inconsistent metadata, standardization of file formats to PNG, conversion of RGB to grayscale where appropriate, normalization of fluorescent channels using 0.1th and 99.9th percentile pixel intensity, and quality control filtering to remove uniform images, binary masks, and dim/empty images [30].

For genomic sequences, the standard protocol involves:

- Sequence acquisition from reference genomes and sequencing repositories

- Tokenization using k-mer splitting with typical k values of 3-6

- Sequence augmentation through reverse complementation and random cropping

- Quality filtering to remove low-complexity and low-quality sequences

Single-cell data requires particularly careful preprocessing due to batch effects and technical noise. The standard workflow includes rigorous quality control, normalization using techniques like SCTransform, highly variable gene selection, and batch correction where necessary [10].

Pretraining Implementation

The technical implementation of pretraining follows a standardized workflow with domain-specific adaptations. The core process involves:

Model Architecture Selection: Choosing appropriate transformer variants (encoder, decoder, or encoder-decoder) based on target tasks. Encoder models excel at classification and representation learning, while decoder models favor generation tasks.

Pretraining Objective Implementation:

- Masked Language Modeling: Randomly masking 15% of input tokens and training the model to reconstruct them

- Next Token Prediction: Autoregressively predicting each token based on previous context

- Contrastive Objectives: Learning representations by maximizing similarity between related biological sequences

Training Configuration: Using large batch sizes (1024+ sequences), optimized learning rate schedules, and distributed training across multiple GPUs/TPUs. Training typically requires days to weeks on specialized hardware.

Validation and Checkpointing: Monitoring performance on held-out validation sets and saving checkpoints for downstream fine-tuning.

The GeneLLM implementation for preterm birth prediction demonstrates a sophisticated multi-omics approach, processing cfDNA VCF files and cfRNA expression matrices through separate tokenization pipelines before integration in a transformer architecture [29]. This model achieved AUCs of 0.822 (cfDNA), 0.851 (cfRNA), and 0.890 (combined) for preterm birth prediction, significantly outperforming conventional machine learning approaches.

Transfer Learning and Fine-tuning

The true power of pretrained biological models emerges through transfer learning. The standard protocol involves:

- Task-Specific Adaptation: Replacing the pretraining head with task-specific layers (e.g., classification layers for disease prediction)

- Progressive Unfreezing: Gradually unfreezing layers during fine-tuning to prevent catastrophic forgetting

- Differential Learning Rates: Applying lower learning rates to earlier layers that capture general features and higher rates to task-specific layers

Cross-species transfer represents a particularly powerful application. Models pretrained on human genomic data successfully transfer to other organisms, achieving high accuracy with minimal fine-tuning. This approach dramatically reduces computational requirements compared to training from scratch for each new species or task [28].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Biological Pretraining

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Datasets | Primary Function | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pretraining Datasets | CytoImageNet [30] | Bioimage pretraining | ~890,000 images, 894 classes, available on Kaggle |

| Genomic Sequences | CZ CELLxGENE [10] | Single-cell transcriptomes | >100 million unique cells, standardized annotations |

| Model Architectures | DNABERT, Nucleotide Transformer [26] | Genomic sequence processing | Open-source implementations available |

| Training Frameworks | PyTorch, JAX, Hugging Face | Model development ecosystem | Open-source with biological extensions |

| Specialized Hardware | GPU/TPU clusters | Accelerated model training | Cloud providers and institutional resources |

Advanced Applications and Validation Frameworks

Interpretability and Biological Discovery

Beyond predictive performance, pretrained models serve as discovery tools when combined with interpretability methods. Sparse autoencoders (SAEs) applied to protein language models have identified missing functional annotations in biological databases. For example, analysis of ESM-2 revealed a "Nudix box motif" feature that correctly identified annotations missing from Swiss-Prot [31]. Similarly, interpretability methods applied to genomic models have uncovered evolutionary relationships, including prophage regions and CRISPR-phage associations that reflect functional biological relationships rather than superficial sequence similarity [31].

The emerging methodology involves:

- Feature Extraction: Using SAEs to decompose model activations into interpretable directions

- Concept Mapping: Associating these directions with biological concepts through enrichment analysis

- Experimental Validation: Testing model-derived hypotheses through targeted experiments

This approach transforms black-box models into hypothesis generation engines, directly contributing to biological knowledge discovery.

Multi-Modal Integration

The most powerful biological pretraining approaches integrate multiple data modalities. The GeneLLM architecture for preterm birth prediction demonstrates this principle, processing both cfDNA variation profiles and cfRNA expression data through quantized representations that are combined in a transformer framework [29]. The integrated model significantly outperformed single-modality approaches, achieving an AUC of 0.890 compared to 0.822 (cfDNA only) and 0.851 (cfRNA only).

The technical implementation involves: