From Code to Cure: How CADD is Revolutionizing Antibiotic Discovery Against Superbugs

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) in the fight against antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

From Code to Cure: How CADD is Revolutionizing Antibiotic Discovery Against Superbugs

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) in the fight against antimicrobial resistance (AMR). Targeting researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of targeting resistant pathogens, details core methodologies like virtual screening and structure-based design, addresses common computational and biological challenges, and evaluates validation strategies through case studies. The synthesis offers a roadmap for integrating CADD into the next generation of antimicrobial pipelines.

Understanding the Enemy: CADD's Role in Targeting Resistant Pathogens

Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR) is a complex global health threat driven by the overuse and misuse of antimicrobials in humans, animals, and agriculture. The following table summarizes the current burden and projected impact, highlighting the urgent need for intervention.

Table 1: The Global Burden and Economic Impact of AMR (2022-2050 Projections)

| Metric | Current/Projected Figure | Source & Year | Key Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct Annual Deaths (Global) | ~1.27 million (attributable), ~4.95 million (associated) | The Lancet, 2022 | AMR is a leading cause of death worldwide, exceeding HIV/AIDS and malaria. |

| Projected Annual Deaths by 2050 | Up to 10 million | O'Neill Review, 2016 | Without action, AMR could cause more deaths than cancer. |

| Additional Healthcare Cost & Productivity Loss (US, Annual) | >$55 billion | CDC, 2019 | AMR imposes a severe financial burden on health systems and economies. |

| Global GDP Loss by 2050 (Cumulative) | $100 trillion | World Bank, 2017 | AMR threatens global economic stability and development goals. |

| Pipeline Sufficiency (Bacteria-focused) | 43% of 32 late-stage candidates are non-traditional | WHO, 2023 | The clinical pipeline remains insufficient and lacks innovation against critical pathogens. |

The Scientific Challenge: Key Resistance Mechanisms

The evolution of resistance is mediated through specific, exploitable biological mechanisms. The primary pathways are summarized below.

Table 2: Major Antimicrobial Resistance Mechanisms and Examples

| Mechanism | Description | Pathogen Example | Drug Class Affected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic Inactivation | Production of enzymes that degrade or modify the drug. | E. coli (ESBL, NDM-1) | β-lactams (Penicillins, Cephalosporins, Carbapenems) |

| Target Modification | Genetic mutation or enzymatic alteration of the drug's binding site. | MRSA (mecA gene), Mycobacterium tuberculosis | β-lactams, Fluoroquinolones |

| Efflux Pump Upregulation | Overexpression of transporters that actively expel the drug from the cell. | Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter baumannii | Tetracyclines, Macrolides, Fluoroquinolones |

| Membrane Permeability Reduction | Loss of porins or changes in membrane structure to limit drug uptake. | P. aeruginosa (loss of OprD) | Carbapenems, Aminoglycosides |

| Bypass Pathway | Development of an alternative metabolic pathway unaffected by the drug. | MRSA (alternative PBP2a) | β-lactams |

Diagram Title: Core Mechanisms of Antimicrobial Resistance

Computational-Aided Drug Discovery (CADD) Protocols

Integrating CADD into the discovery workflow accelerates the identification of novel therapeutics targeting resistance mechanisms.

Protocol 3.1: Structure-Based Virtual Screening for Novel Efflux Pump Inhibitors

Objective: To identify small-molecule inhibitors of the E. coli AcrB efflux pump proton transporter subunit using a high-resolution crystal structure.

Reagents & Materials:

- Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID: 4DX5 (AcrB proton transporter, inhibited state).

- Chemical Libraries: ZINC15 "Fragment Now" subset, Enamine REAL Diversity-Oriented Synthesis (DOS) library.

- Software: UCSF Chimera (preparation), AutoDock Vina (docking), PyMOL (visualization), Open Babel (format conversion).

- Hardware: High-performance computing cluster with GPU acceleration.

Procedure:

- Target Preparation:

- Download PDB file 4DX5. Remove co-crystallized ligand, water molecules, and heteroatoms.

- Add polar hydrogen atoms and compute Gasteiger partial charges using UCSF Chimera.

- Define the binding site grid box centered on the known inhibitor (e.g., D13-9001) binding pocket in the transmembrane region. Set box dimensions to 20x20x20 Å.

- Ligand Library Preparation:

- Download ~10,000 drug-like compounds from specified libraries in SDF format.

- Convert to PDBQT format using Open Babel, enumerating protonation states at pH 7.4.

- Molecular Docking:

- Execute AutoDock Vina in batch mode. Use an exhaustiveness value of 32 for thorough sampling.

- Dock each ligand into the defined grid box. Output the top 9 binding poses per ligand ranked by Vina score (kcal/mol).

- Post-Docking Analysis:

- Cluster results by binding pose and chemical scaffold. Select top 200 compounds based on score and interaction profile (e.g., key hydrogen bonds with residues Arg620, Asn274).

- Visually inspect top 50 complexes in PyMOL for sensible binding modes.

Protocol 3.2: Pharmacophore Modeling for Broad-Spectrum β-Lactamase Inhibitors

Objective: To generate a ligand-based pharmacophore model from known serine β-lactamase inhibitors (e.g., avibactam, relebactam) to screen for novel scaffolds.

Reagents & Materials:

- Ligand Set: 3D structures of 15 known covalent and non-covalent β-lactamase inhibitors (SDF format).

- Software: MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) or LigandScout.

- Database: ChEMBL database filtered for molecules with reported activity against class A β-lactamases.

Procedure:

- Ligand Preparation & Alignment:

- Energy minimize all 15 inhibitor structures using the MMFF94x forcefield.

- Perform flexible structural alignment based on the shared pharmacophoric features.

- Model Generation:

- Use the "Pharmacophore Query" module to identify common features: a) Anionic center (carboxylate/sulfate), b) Hydrogen bond acceptor (carbonyl oxygen), c) Two hydrophobic aromatic centers.

- Define geometric constraints (distances, angles) between features based on the aligned set.

- Validate model by screening a decoy set; calculate Guner-Henry score (>0.7 acceptable).

- Virtual Screening:

- Use the validated pharmacophore as a 3D query to screen the prepared ChEMBL subset.

- Retrieve and visually inspect the top 500 hits that match all critical features.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for AMR & CADD Integration Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CAMHB) | Standardized medium for broth microdilution antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST). | Determining MIC values for novel hits against WHO priority pathogens. |

| Checkerboard Assay Plate (96-well) | Pre-formatted microtiter plate for efficient testing of drug combination synergy (e.g., novel inhibitor + existing antibiotic). | Evaluating the efficacy of a candidate efflux pump inhibitor in combination with levofloxacin. |

| Clinical Isolate Panels (ESKAPE Pathogens) | Defined sets of genetically characterized, multidrug-resistant clinical bacterial isolates. | Profiling the spectrum of activity of a new compound against real-world resistant strains. |

| β-Lactamase Enzymes (Recombinant, Purified) | Purified enzymes (e.g., NDM-1, KPC-2) for high-throughput enzymatic inhibition assays. | Validating hits from the pharmacophore screen in a biochemical inhibition assay. |

| Membrane Permeabilization Assay Kit | Uses fluorescent dyes (e.g., SYTOX Green) that only enter cells with compromised membranes. | Mechanistic study to confirm if a novel peptide disrupts bacterial outer membrane integrity. |

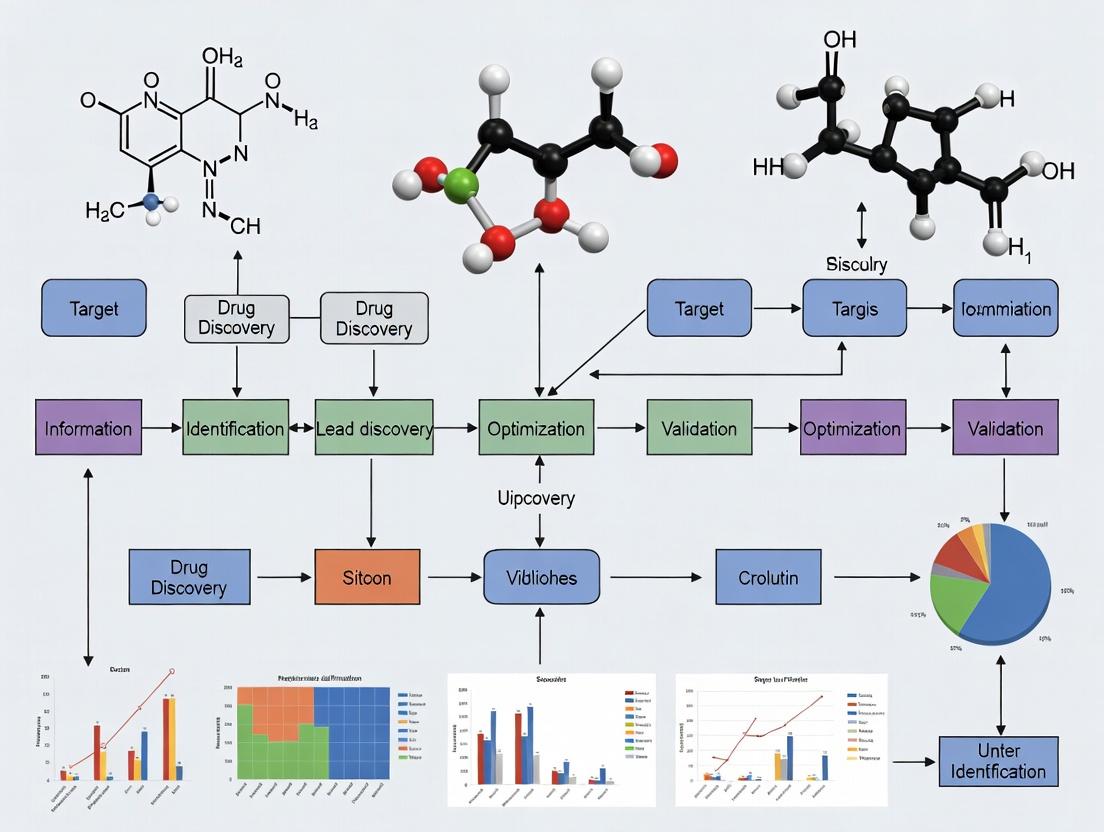

Diagram Title: Integrated CADD-Experimental Workflow for Novel Anti-AMR Therapeutics

Application Notes: CADD in AMR Drug Discovery

The global antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis necessitates accelerated discovery of novel agents against resistant pathogens. Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) provides a strategic framework to prioritize candidates, reduce experimental costs, and understand resistance mechanisms. This note details contemporary CADD applications targeting AMR.

Target Identification & Prioritization

Genomic and proteomic comparisons between resistant and susceptible strains identify potential targets. Essentiality and conservation analyses prioritize targets with broad-spectrum potential and low human homology.

Table 1: Prioritized AMR Targets from Recent Pan-Genomic Analyses (2023-2024)

| Target Protein (Pathogen) | Resistance Mechanism Addressed | Essentiality Score | Druggability (AF2 pLDDT) | Conserved Across Strains |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LpxC (A. baumannii) | LPS biosynthesis, Colistin resistance | 0.98 | 92.1 | 99% |

| DNA Gyrase B (M. tuberculosis) | Fluoroquinolone resistance mutations | 0.96 | 89.7 | 100% |

| NDM-1 (K. pneumoniae) | Metallo-β-lactamase enzyme | N/A (non-essential) | 88.5 | 78% (plasmid-borne) |

| Ddl (E. faecium) | D-Ala-D-Ala ligase, Vancomycin resistance bypass | 0.91 | 85.2 | 95% |

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD)

High-resolution structures from AlphaFold2 DB and experimental crystallography enable virtual screening and rational design against previously intractable targets.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of SBDD Workflows Against AMR Targets (Recent Benchmarks)

| Method (Software) | Target Class | Avg. Enrichment Factor (Top 1%) | Avg. RMSD of Predicted Pose (Å) | Computational Cost (GPU hrs/1000 cpds) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glide (XP) | Enzymes | 32.5 | 1.8 | 12.4 |

| AutoDock-GPU | Membrane Proteins | 18.7 | 2.5 | 4.2 |

| DiffDock | Novel Folds (AF2) | 25.1 | 2.1 | 8.7 (including inference) |

| FRED (OEDocking) | Protein-Protein Interfaces | 12.9 | 3.0 | 3.8 |

AI/ML for ADMET & Resistance Prediction

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Transformer models predict compound activity, toxicity, and potential resistance emergence early in the pipeline.

Table 3: Predictive Model Performance for Key ADMET/Resistance Properties

| Model (Platform) | Prediction Task | Dataset Size | Avg. AUC-ROC | Key Features Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MegaMolBART (Relenza) | hERG inhibition | 450,000 | 0.89 | SMILES, molecular graphs |

| DeepAR (In-house) | MIC against ESKAPE panel | 12,450 | 0.81 | ECFP6, 3D pharmacophores |

| RoBERTa (DrugResist) | Mutation-induced resistance likelihood | 8,120 mutations | 0.76 | Protein sequence, ligand fingerprint |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Structure-Based Virtual Screening for β-Lactamase Inhibitors

Objective: Identify novel, non-β-lactam scaffolds that inhibit the Class A β-lactamase KPC-2.

Materials:

- Hardware: GPU cluster node (minimum: NVIDIA V100, 32GB RAM).

- Software: UCSF ChimeraX, OpenBabel, AutoDock-GPU 1.2, Python 3.9+ with RDKit.

- Data: KPC-2 crystal structure (PDB: 5UL8), prepared library of 50,000 lead-like compounds (ZINC20).

Procedure:

- Target Preparation (ChimeraX):

- Load 5UL8. Remove water molecules and co-crystallized ligand.

- Add polar hydrogens. Assign AMBER ff14SB charges via DockPrep module.

- Define a grid box centered on the catalytic Ser70 residue (coordinates: x= -12.8, y= 17.2, z= 45.1). Set box dimensions to 20x20x20 Å.

- Ligand Library Preparation (OpenBabel/RDKit):

- Convert library from SDF to PDBQT format:

babel -isdf input.sdf -opdbqt output.pdbqt -xm -p 7.4. - Generate up to 10 conformers per ligand using RDKit's ETKDG method.

- Convert library from SDF to PDBQT format:

- Virtual Screening (AutoDock-GPU):

- Execute batch docking:

autodock_gpu_128wi -ffile target.pdbqt -lfile ligands.pdbqt -nrun 50 -heuristic 1. - Use Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm. Set population size to 150, energy evaluations to 2,500,000.

- Execute batch docking:

- Post-Docking Analysis:

- Rank compounds by predicted binding energy (ΔG in kcal/mol).

- Cluster top 500 poses by root-mean-square deviation (RMSD < 2.0 Å).

- Visually inspect top 50 unique scaffolds for key interactions with S70, K73, E166, and S130.

- Output: Ranked list of 200 top-scoring compounds for in vitro assay.

Protocol 2: AI-Driven De Novo Design of Gram-Negative Outer Membrane Permeators

Objective: Generate novel small molecules predicted to penetrate the Pseudomonas aeruginosa outer membrane via porins.

Materials:

- Hardware: Single NVIDIA A100 GPU, 64 GB CPU RAM.

- Software: REINVENT 4.0, PyTorch, OM permeability prediction model (trained on logP_op data).

- Data: SMILES of known porin-permeating molecules (n=1,200), PAO1 OM lipid composition profile.

Procedure:

- Agent Configuration (REINVENT):

- Load a pre-trained RNN as the Prior network.

- Define a custom Scoring Function (SF) combining:

- Predictive Model:

P(permeation) = 0.6 * [OM_model_output] - PhysChem Filters:

+ 0.2 * [1 if 200<MW<500 & -2<LogD<5 else 0] - Novelty Penalty:

- 0.2 * [Tanimoto similarity to known permeators > 0.7]

- Predictive Model:

- Set reinforcement learning parameters: σ=120, learning rate=0.0001.

- Generative Run:

- Initialize the Agent network as a copy of the Prior.

- Run for 500 epochs. In each epoch, the Agent generates 100 molecules, which are scored by the SF.

- The Agent's weights are updated to maximize the likelihood of generating high-scoring molecules.

- Validation & Output:

- Extract the top 50 unique scaffolds from the final epoch.

- Run MD-based membrane insertion simulations (PMX) on 5 selected candidates to validate porin localization.

- Output: A focused library of 50 generated compounds for synthesis and uptake assays.

Visualization

Diagram 1: CADD Workflow for AMR Target Discovery

Diagram 2: Key Resistance Mechanisms & CADD Intervention Points

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools & Resources for CADD in AMR Research

| Item Name (Vendor/Provider) | Category | Function/Benefit in AMR CADD |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 Database (EMBL-EBI) | Protein Structure | Provides high-accuracy predicted structures for resistant pathogen targets lacking experimental data. |

| ZINC22 (UCSF) | Compound Library | Curated, purchasable library of >230 million compounds for virtual screening. |

| CARD Database (McMaster Uni) | Bioinformatics | Comprehensive repository of antimicrobial resistance genes, proteins, and mutations. |

| GLASS (Go Lab) | Screening Collection | A focused, physicochemically diverse library pre-filtered for predicted Gram-negative permeation. |

| ChEMBL (EMBL-EBI) | Bioactivity Data | Manually curated database of drug-like molecules with bioactivity data against pathogens. |

| AutoDock-GPU (Scripps) | Docking Software | Accelerated molecular docking suite enabling high-throughput virtual screening on GPU clusters. |

| GROMACS 2024 (Open Source) | Molecular Dynamics | Performs all-atom MD simulations to study drug-target binding stability and membrane permeation. |

| REINVENT 4.0 (Pfizer/Open) | AI Generative Model | Deep reinforcement learning framework for de novo molecular design optimized against custom rewards. |

| Open Babel (Open Source) | Cheminformatics | Converts chemical file formats, calculates descriptors, and filters compound libraries. |

| PyMOL 3.0 (Schrödinger) | Visualization | Critical for analyzing docking poses, protein-ligand interactions, and structural biology data. |

Application Note 1: Targeting Essential Bacterial Enzymes with CADD

Within the broader thesis of CADD applications in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) drug discovery, the inhibition of essential enzymes remains a cornerstone strategy. These targets are crucial for bacterial survival and proliferation, offering a direct path to bactericidal or bacteriostatic effects. CADD accelerates the identification and optimization of novel inhibitors by screening vast virtual libraries against high-resolution enzyme structures, predicting binding affinities, and optimizing lead compounds for potency and selectivity.

Table 1: Key Essential Enzyme Targets in AMR Drug Discovery

| Target Enzyme | Primary Function | Representative Pathogens | Known Inhibitor(s) | CADD Utility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Gyrase/Topoisomerase IV | DNA replication & supercoiling | E. coli, S. aureus | Fluoroquinolones (e.g., Ciprofloxacin) | Structure-based design to overcome QRDR mutations. |

| Dihydrofolate Reductase (DHFR) | Folic acid synthesis | S. aureus, E. coli | Trimethoprim | Scaffold hopping to design analogs avoiding common resistant variants. |

| β-Lactamases | β-lactam antibiotic hydrolysis | K. pneumoniae, E. coli | Clavulanic acid, Avibactam | Virtual screening for novel, broad-spectrum β-lactamase inhibitors. |

| MurA (UDP-N-acetylglucosamine enolpyruvyl transferase) | Peptidoglycan biosynthesis | H. pylori, M. tuberculosis | Fosfomycin | Pharmacophore modeling to find new inhibitors of this validated target. |

| Ligand (Lip)G4 | Lipid A biosynthesis | P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii | CHIR-090 (experimental) | Molecular docking to optimize arylacetylene bisphosphonate scaffolds. |

Protocol 1.1: In Silico Screening for Novel DHFR Inhibitors

Objective: To identify novel, high-affinity inhibitors of bacterial DHFR using a CADD workflow.

Materials & Workflow:

- Target Preparation: Retrieve the crystal structure of Trimethoprim-resistant S. aureus DHFR (e.g., PDB ID: 2W9S) from the RCSB Protein Data Bank. Using molecular modeling software (e.g., Schrödinger Maestro, UCSF Chimera), remove water molecules, add hydrogens, assign bond orders, and optimize protonation states of key residues (e.g., Asp27, Ile20).

- Binding Site Definition: Define the active site using the coordinates of the bound folate or Trimethoprim. Generate a grid box encompassing the site with ~10 Å margin.

- Library Preparation: Prepare a virtual library of small molecules (e.g., ZINC20 fragment library) by generating 3D conformers and minimizing their energy.

- Virtual Screening: Perform high-throughput virtual screening (HTVS) using a docking program (e.g., AutoDock Vina, Glide). Screen compounds first with a fast, less precise method, then re-dock top hits (e.g., 1000 compounds) with higher precision.

- Post-Docking Analysis: Rank compounds by docking score (kcal/mol). Visually inspect top-ranking poses for key interactions: hydrogen bonds with Asp27 and Ile5, π-π stacking with Phe92. Apply filters for drug-likeness (Lipinski's Rule of Five).

- MM/GBSA Calculation: Refine binding affinity predictions for the top 100 hits using a more rigorous Molecular Mechanics/Generalized Born Surface Area (MM/GBSA) calculation.

Diagram: CADD Workflow for Enzyme Inhibitor Discovery

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents for Enzyme Inhibition Assays

- Recombinant Target Enzyme: Purified protein for in vitro activity assays.

- Fluorogenic/Luminescent Substrate: Enables real-time, high-throughput measurement of enzyme activity (e.g., Substrate for β-lactamase hydrolysis).

- Positive Control Inhibitor: Validated inhibitor (e.g., Trimethoprim for DHFR) to benchmark assay performance.

- ITC/MST Reagents: Isothermal Titration Calorimetry or Microscale Thermophoresis kits for direct measurement of binding affinity (Kd).

- 96/384-Well Assay Plates: For high-throughput screening of compound libraries.

Application Note 2: Disrupting Efflux Pumps via CADD

Efflux pumps are a major AMR mechanism, extruding diverse antibiotics and reducing intracellular concentration. CADD is instrumental in developing Efflux Pump Inhibitors (EPIs), which can restore the efficacy of existing antibiotics. Strategies include: 1) Designing competitive substrates that jam the pump, 2) Developing allosteric inhibitors that interfere with pump energy coupling or assembly, and 3) Identifying inhibitors of transcriptional regulators of pump expression (e.g., ramA, marR).

Table 2: Major Efflux Pump Families & CADD Strategies

| Pump Family | Energy Source | Key Example | Substrates | CADD Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RND (Resistance-Nodulation-Division) | Proton Motive Force | AcrAB-TolC (E. coli) | Tetracyclines, β-lactams, Fluoroquinolones | Docking into AcrB substrate binding pockets (Deep, Proximal). |

| MFS (Major Facilitator Superfamily) | Proton Motive Force | NorA (S. aureus) | Fluoroquinolones, Dyes | Pharmacophore modeling based on known EPIs like reserpine. |

| MATE (Multidrug and Toxic Compound Extrusion) | Na+ or H+ gradient | NorM (V. cholerae) | Fluoroquinolones, Aminoglycosides | Molecular dynamics to study Na+ ion binding and transport cycle. |

| ABC (ATP-Binding Cassette) | ATP Hydrolysis | MsrA (S. epidermidis) | Macrolides, Streptogramins | Targeting the ATPase nucleotide-binding domain (NBD). |

Protocol 2.1: Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation of AcrB with Inhibitor

Objective: To simulate the interaction dynamics and stability of a novel EPI bound to the AcrB efflux pump.

Materials & Workflow:

- System Setup: Use the crystal structure of AcrB (PDB ID: 4DX5). Dock the proposed EPI into the distal binding pocket. Use a tool like CHARMM-GUI to embed the protein-ligand complex in a phospholipid bilayer (e.g., POPE), solvate with TIP3P water, and add ions (Na+, Cl-) to neutralize the system (~0.15 M).

- Energy Minimization: Perform 5,000 steps of steepest descent minimization to remove steric clashes.

- Equilibration: Run a two-phase equilibration using NVT (constant Number, Volume, Temperature) for 100 ps, then NPT (constant Number, Pressure, Temperature) for 200 ps, gradually releasing restraints on the protein.

- Production MD: Run an unrestrained MD simulation for 100-200 ns using a GPU-accelerated engine (e.g., AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD). Maintain temperature at 310 K (Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover thermostat) and pressure at 1 bar (Parrinello-Rahman barostat).

- Trajectory Analysis: Analyze root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the protein and ligand, root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of binding site residues, hydrogen bond occupancy, and interaction fingerprints over time.

Diagram: Efflux Pump Inhibition Pathways & CADD

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents for Efflux Studies

- Fluorometric Efflux Substrates: (e.g., Ethidium Bromide, Hoechst 33342) to visualize and quantify pump activity via fluorescence.

- Protonophore (CCCP): A positive control that dissipates proton motive force, inhibiting RND/MFS pumps.

- Real-time PCR Kits: To quantify efflux pump gene expression levels in response to treatment.

- Membrane Protein Purification Kits: For isolating functional efflux pumps for biochemical assays.

- Strains with Overexpressed/Deleted Pumps: Isogenic bacterial strains to confirm EPI mechanism of action.

Application Note 3: Targeting Biofilm Formation and Persistence

Biofilms are structured microbial communities encased in an extracellular polymeric substance (EPS), conferring up to 1000x increased antibiotic tolerance. CADD approaches target: 1) Quorum Sensing (QS) Systems: Disrupting bacterial communication (e.g., LasR/LuxR receptors in P. aeruginosa). 2) Second Messenger Systems: Inhibiting cyclic-di-GMP synthesis/degradation enzymes to reduce biofilm stability. 3) EPS Matrix Components: Designing enzymes or small molecules that degrade alginate, PNAG, or eDNA.

Table 3: CADD Targets for Anti-Biofilm Strategies

| Target System | Key Target/Protein | Function in Biofilm | CADD Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quorum Sensing | LasR receptor (P. aeruginosa) | Activates virulence & biofilm genes | Virtual screening for competitive antagonists of the autoinducer binding pocket. |

| c-di-GMP Signaling | Diguanylate Cyclase (DGC) | Synthesizes c-di-GMP, promotes biofilm | Structure-based design of inhibitors targeting the catalytic GG(D/E)EF domain. |

| EPS Matrix | PslG (P. aeruginosa) | Glycosyl hydrolase that degrades Psl | In silico screening for small-molecule activators of PslG. |

| Two-Component Systems | BfmS/BfmR (A. baumannii) | Regulates biofilm formation & adhesion | Targeting the histidine kinase (BfmS) ATP-binding site. |

Protocol 3.1: Pharmacophore Modeling for LasR Antagonists

Objective: To generate a pharmacophore model for screening virtual libraries to find novel LasR QS inhibitors.

Materials & Workflow:

- Ligand Set Curation: Collect 10-20 known LasR agonists (e.g., 3-oxo-C12-HSL) and antagonists (e.g., furanones, triazoles) with reported IC50 values. Prepare their 3D structures using a conformational search.

- Common Feature Pharmacophore Generation: Use software (e.g., Catalyst/HypoGen, Phase) to align multiple active antagonists and identify common chemical features: Hydrogen Bond Acceptors (HBA), Hydrogen Bond Donors (HBD), Hydrophobic (H) regions, and Aromatic Rings (R).

- Model Validation: Test the generated pharmacophore model by screening a small, known decoy set containing both actives and inactives. Calculate enrichment factors and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves to assess model quality.

- Virtual Screening: Use the validated model as a 3D query to screen a large commercial database (e.g., Enamine REAL). Retrieve compounds that match all or critical features of the pharmacophore.

- Post-Processing: Dock the retrieved hits into the LasR binding site (PDB ID: 3IX3) to refine the selection and predict binding poses.

Diagram: Multi-Target CADD Strategy Against Biofilms

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents for Biofilm Studies

- Microtiter Plate (96-well) for CV Staining: Polystyrene plates for growing and quantifying biofilms via crystal violet (CV) assay.

- Synthetic Autoinducers: (e.g., C4-HSL, 3-oxo-C12-HSL) for QS induction controls.

- c-di-GMP ELISA Kit: To quantify intracellular c-di-GMP levels upon treatment.

- Fluorescent Conjugates (ConA, WGA): Lectins for staining specific EPS polysaccharides (e.g., Psl, Pel) in confocal microscopy.

- Flow Cell Systems: For growing biofilms under continuous flow for advanced imaging and real-time disruption studies.

Leveraging Genomic and Structural Data from Resistant Bacterial Strains

Application Note AN-101: Integrating Genomic and Structural Data for CADD-Driven Target Identification

The growing crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) necessitates novel strategies for drug discovery. This application note details a Computational-Aided Drug Design (CADD) workflow that integrates genomic data from resistant bacterial strains with high-resolution structural biology to identify and prioritize novel antimicrobial targets and compounds. This work is framed within a broader thesis that posits CADD as an essential accelerator for overcoming AMR by rationally designing inhibitors against validated, resistance-associated targets.

Core Data Workflow and Key Quantitative Insights

The process begins with the comparative genomic analysis of resistant versus susceptible bacterial isolates. Key metrics include Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) density, gene presence/absence, and the identification of non-synonymous mutations in putative target proteins. These genomic insights guide the selection of proteins for structural characterization.

Table 1: Summary of Genomic Analysis Metrics from a Prototypical K. pneumoniae Carbapenem-Resistant (CRKP) Study

| Metric | Susceptible Strain (n=50 isolates) | Resistant Strain (n=50 isolates) | Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. SNPs in penA (PBP2x) | 2.1 ± 1.5 | 18.7 ± 4.2 | <0.001 |

| Presence of blaKPC gene | 0% | 100% | <0.001 |

| Non-synonymous mutations in efflux pump regulator ramR | 12% | 94% | <0.001 |

| Copy number variation of acrAB efflux operon | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 2.3 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

Structural data, primarily from X-ray crystallography and Cryo-EM, is used to understand the mechanistic basis of resistance conferred by mutations identified in Table 1. For instance, structures of mutant Penicillin-Binding Proteins (PBPs) with reduced antibiotic affinity or mutant beta-lactamases with extended spectrum activity are solved.

Table 2: Structural Impact of Common Resistance Mutations in Key Bacterial Targets

| Target Protein (PDB ID) | Resistance Mutation | Effect on Antibiotic Binding (ΔΔG, kcal/mol)* | Structural Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| PBP2a (7CIT) | M641F | +3.2 | Steric occlusion of drug entry channel |

| NDM-1 Beta-lactamase (6NIP) | M154L | +1.8 | Altered active site water network |

| DNA Gyrase (6F86) | S83L | +4.1 | Loss of key hydrogen bond with fluoroquinolone |

| MmpL3 (6AJG) | S288R | +2.5 | Electrostatic repulsion of inhibitor scaffold |

*Positive ΔΔG indicates destabilization of the drug-protein complex.

These integrated data streams feed directly into CADD pipelines for structure-based virtual screening (SBVS) and de novo design against the resistant variant of the target.

Protocol PRO-101: Structure-Based Virtual Screening Against a Resistance-Conferred Target Variant

Objective: To identify novel lead compounds that effectively bind to the mutant, resistance-associated form of a target protein (e.g., PBP2a M641F) using a sequential computational screening protocol.

Materials & Software:

- Hardware: High-performance computing cluster with GPU acceleration.

- Software: Molecular docking suite (e.g., Schrödinger Glide, AutoDock Vina), molecular dynamics (MD) simulation package (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER), cheminformatics toolkit (e.g., RDKit).

- Data Inputs:

- High-resolution protein structure of mutant target (from PDB or homology model).

- Prepared commercial screening library (e.g., Enamine REAL, ZINC20, ~1-10 million compounds).

Procedure:

Target Preparation (2-4 hours):

- Download the mutant protein structure (e.g., PDB: 7CIT chain A).

- Using a protein preparation wizard, add missing hydrogen atoms, assign correct protonation states for residues (especially in the active site) at physiological pH (7.4), and optimize hydrogen bonding networks.

- Define a grid box for docking centered on the binding site of the native ligand or the region impacted by the resistance mutation.

Ligand Library Preparation (3-5 hours):

- Download and curate a screening library in SMILES format.

- Generate 3D conformers for each compound using tools like OMEGA or RDKit.

- Apply standard energy minimization and assign correct partial charges (e.g., OPLS4, MMFF94s).

High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) & Standard Precision (SP) Docking (24-48 hours):

- Perform an initial, rapid HTVS docking of the entire library to the prepared mutant target grid.

- Select the top 10% of compounds ranked by docking score.

- Re-dock this subset using more rigorous SP docking with flexible sampling.

Post-Docking Analysis & Enrichment (8-12 hours):

- Cluster the top 1,000 SP hits based on chemical similarity.

- Select top-ranked representatives from each major cluster for visual inspection, focusing on compounds forming specific interactions with residues critical for function and/or compensating for the resistance mutation (e.g., forming new bonds with M641F).

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Validation (5-7 days):

- For the top 20-30 candidate complexes, run an MD simulation (e.g., 100 ns in explicit solvent).

- Analyze root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), ligand-protein interaction fingerprints, and binding free energies (using MMPBSA/GBSA).

- Prioritize compounds demonstrating stable binding poses and favorable calculated binding affinities to the mutant target.

Expected Outcome: A shortlist of 5-10 computationally validated lead compounds with predicted activity against the resistant bacterial target, ready for in vitro biochemical and antimicrobial testing.

Visualization of Workflows

Genomic & Structural Data Integration for CADD

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Featured Protocols

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Resistant Strain Panels (e.g., CRISPR-BAGEL, BEI Resources) | Validated, quality-controlled genomic DNA from pan-resistant bacterial strains (e.g., CRKP, MRSA) for benchmarking genomic analyses and resistance gene detection. |

| Cloning & Expression Kits for Mutant Proteins (e.g., NEB HiFi Assembly, pET vectors) | Essential for constructing plasmids expressing the specific mutant target proteins identified from genomic data, enabling their production for structural studies. |

| Crystallization Screening Kits (e.g., JC SG, Morpheus, MemGold) | Pre-formulated sparse matrix screens used to identify initial crystallization conditions for novel or mutant membrane and soluble proteins. |

| Virtual Screening Compound Libraries (e.g., Enamine REAL, ZINC, MolPort) | Large, commercially available, chemically diverse libraries in ready-to-dock 3D formats, providing the chemical matter for computational screening campaigns. |

| GPU-Accelerated Cloud Computing (e.g., AWS EC2 G4/G5, Google Cloud A2) | Provides on-demand, scalable computational power necessary for running resource-intensive molecular docking and MD simulations. |

| MD Simulation Parameter Databases (e.g., CHARMM36, GAFF2) | Force fields providing the mathematical parameters for atoms and bonds, crucial for running accurate and physically meaningful MD simulations of drug-target complexes. |

Application Note: CADD in Target Identification & Validation for AMR

Objective: To identify and prioritize novel, essential bacterial targets with low human homology to address antimicrobial resistance.

CADD Integration: In silico comparative genomics, pangenome analysis, and structural bioinformatics are deployed to analyze pathogen genomes. Essentiality is predicted via gene knockout simulations, while homology modeling identifies unique structural features.

Key Data & Findings:

Table 1: In Silico Prioritization of Novel Bacterial Targets for a Gram-Negative Pathogen

| Target Gene | Essentiality Score | Human Homology (%) | Known Resistance Mutations | Druggability Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FabI | 0.98 | 22 | Yes (clinical) | 0.87 |

| MrdA | 0.96 | 18 | No | 0.65 |

| Lipid A Kinase X | 0.99 | 12 | Rare | 0.72 |

| Metallo Enzyme Y | 0.94 | 31 | Yes (in vitro) | 0.91 |

Protocol 1.1: Genomic Essentiality and Druggability Profiling

- Data Acquisition: Download complete genome sequences for target pathogen and non-pathogenic strains from NCBI RefSeq.

- Pangenome Analysis: Use Panaroo (v1.3) to define core (present in all strains) and accessory genomes.

- Essentiality Prediction: Submit core genome to the DEG (Database of Essential Genes) API for cross-species essentiality mapping. Complement with metabolic network reconstruction tools like ModelSEED.

- Homology Screening: Perform BLASTp of core genes against the human proteome (UniProt). Filter targets with <35% sequence identity.

- Druggability Assessment: For filtered targets, generate homology models using SWISS-MODEL. Screen models against the SiteMap (Schrödinger) module to identify potential binding pockets with favorable properties (size, hydrophobicity, enclosure).

- Prioritization: Rank targets using a composite score: Essentiality (40%), Low Human Homology (30%), Druggability Index (30%).

Application Note: Structure-Based Virtual Screening (SBVS) Against a Novel AMR Target

Objective: To rapidly identify hit compounds that bind to the active site of a validated, resistance-free bacterial target.

CADD Integration: Molecular docking screens millions of compounds against a 3D protein structure. Pharmacophore modeling and MM-GBSA scoring refine hit selection.

Protocol 2.1: High-Throughput Virtual Screening Workflow

- Target Preparation: Obtain the crystal structure (e.g., PDB ID: 7BXY). Use Protein Preparation Wizard (Maestro) to add hydrogens, assign bond orders, optimize H-bonds, and perform restrained minimization.

- Compound Library Preparation: Download the "ZINC20 Lead-Like" library (~10 million compounds). Prepare ligands using LigPrep, generating possible tautomers and protonation states at pH 7.4 ± 2.

- Grid Generation: Define the binding site using the native ligand or SiteMap coordinates. Generate a receptor grid with an inner box (10x10x10 Å) centered on the site.

- Molecular Docking: Execute Glide HTVS followed by SP and XP docking stages. Apply OPLS4 force field.

- Post-Docking Analysis: Re-score top 1000 XP poses using MM-GBSA (Prime). Apply a pharmacophore filter (e.g., requires one hydrogen bond donor and two hydrophobic features).

- Visual Inspection & Selection: Manually inspect the top 100 ranked, filtered poses for binding mode rationality. Select 50 compounds for in vitro testing.

Table 2: Top Virtual Screening Hits Against Target MrdA

| ZINC ID | Glide XP GScore (kcal/mol) | MM-GBSA dG Bind (kcal/mol) | Pharmacophore Match | Predicted LE |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ZINC000008 | -12.3 | -65.8 | Full | 0.41 |

| ZINC000542 | -11.7 | -59.3 | Full | 0.38 |

| ZINC001204 | -11.5 | -62.1 | Partial | 0.35 |

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Schrödinger Suite: Integrated software for protein prep, docking, and scoring.

- ZINC20 Database: Publicly accessible library of commercially available compounds for virtual screening.

- Prime (MM-GBSA): Tool for more accurate binding free energy estimation.

- PyMOL: For 3D visualization and analysis of docking poses.

- COOT: For crystallographic model building and validation of target structures.

Title: CADD Integration Across the Drug Discovery Pipeline

Application Note & Protocol: Predictive ADMET and Resistance Liability Modeling

Objective: To optimize lead compounds for favorable pharmacokinetics and low propensity to induce resistance.

CADD Integration: QSAR models predict absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) properties. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations assess the energetic cost of potential resistance mutations.

Protocol 3.1: Resistance Liability Assessment via MD Simulation

- System Setup: Model the lead compound bound to the target (e.g., FabI-enoyl reductase). Use the Desmond system builder to solvate the complex in an orthorhombic water box with OPC3 water model and neutralize with ions.

- Wild-Type Simulation: Run a 200 ns MD simulation under NPT conditions (300K, 1 bar). Record root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) and protein-ligand contacts.

- Mutant Modeling: Introduce a clinically observed resistance mutation (e.g., G93S) in silico using the residue mutation tool. Repeat system setup and simulation.

- Binding Energy Analysis: Use the MM-GBSA method to calculate the binding free energy (ΔG_bind) for the ligand to both wild-type and mutant proteins from 100 equally spaced trajectory frames.

- Interpretation: A significant increase in ΔG_bind for the mutant indicates high resistance liability. Prioritize leads that maintain strong binding despite the mutation or interact with conserved, mutationally constrained residues.

Table 3: Predicted ADMET and Resistance Profile for Lead Series

| Compound | Predicted Caco-2 Permeability (nm/s) | hERG Inhibition Risk | CYP3A4 Inhibition | ΔΔG_bind (Mutant - WT) kcal/mol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead-1 | 350 | Low | Medium | +4.2 (High Liability) |

| Lead-2 | 280 | Low | Low | +0.8 (Low Liability) |

| Lead-3 | 510 | Medium | Low | +1.5 (Moderate Liability) |

Title: Predictive ADMET and Resistance Liability Workflow

The CADD Toolkit: Key Strategies for Designing Novel Antimicrobials

Application Notes

Structure-Based Drug Design (SBDD) is a pivotal computational approach in combating antimicrobial resistance (AMR). It enables the rational design of novel inhibitors that target evolving resistance mechanisms, specifically mutated enzyme active sites and regulatory allosteric pockets. This application is critical for extending the lifespan of existing antibiotic classes and developing novel, resistance-evading therapeutics.

1. Targeting Mutated Active Sites: Pathogens acquire single or multiple point mutations in antibiotic target sites (e.g., beta-lactamases, RNA polymerase, DNA gyrase), reducing drug binding affinity. SBDD strategies involve:

- Resistance Mutation Mapping: Using computational structural biology to model mutant protein structures and identify altered binding geometries.

- Adaptive Docking: Screening compound libraries against mutant active sites to identify scaffolds maintaining interactions despite mutations.

- Consensus Pharmacophore Design: Deriving common interaction features required to inhibit both wild-type and prevalent mutant forms.

2. Targeting Allosteric Pockets: Allosteric sites offer advantages for overcoming resistance, as they are often less conserved and under lower evolutionary selection pressure than orthosteric (active) sites.

- De Novo Allosteric Site Prediction: Using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and binding site detection algorithms (e.g., Fpocket, SiteMap) to identify cryptic, regulatory pockets.

- Allosteric Modulator Design: Designing compounds that stabilize inactive conformations or disrupt functional dynamics, leading to inhibition.

- Dual-Targeting Strategies: Designing bivalent or bifunctional molecules that simultaneously engage the active site and an allosteric pocket for enhanced potency and resistance profile.

Quantitative Data Summary: Recent SBDD Successes in AMR (2022-2024)

Table 1: SBDD-Derived Inhibitors Against Mutated Targets

| Target Protein (Pathogen) | Resistance Mutation | Computationally Designed Inhibitor | Experimental IC50/Ki | Improvement over Legacy Drug |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NDM-1 Beta-lactamase (K. pneumoniae) | V88L, D130G | VNRX-9948 (Boronic acid transition-state analog) | 0.08 µM | >100x more potent than meropenem vs. NDM-1 |

| DNA Gyrase (E. coli) | S83L, D87N (QRDR) | Novel spiropyrimidinetrione | 0.5 µM | Retains activity against ciprofloxacin-resistant strains |

| DHFR (S. aureus) | F98Y, H30N | Compound 6a (Propargyl-linked diaminopteridine) | 9 nM | 500x more potent than trimethoprim |

Table 2: Allosteric Inhibitors Discovered via SBDD

| Target Protein (Pathogen) | Allosteric Site Description | Discovery Method | Inhibitor Mode of Action | Efficacy (in vitro) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX-M-15 Beta-lactamase (E. coli) | Distal to active site, near Ω-loop | MD Simulations + Virtual Screening | Non-competitive, stabilizes occluded state | Restores ampicillin efficacy (MIC reduced to 2 µg/mL) |

| AAC(6')-Ib (A. baumannii) | Dimerization interface | Protein-Protein Interaction Docking | Disrupts dimerization, abolishes acetylation | Reduces amikacin MIC by 64-fold in resistant strain |

| KasA (M. tuberculosis) | Substrate channel, 12Å from active site | Fpocket + Pharmacophore Modeling | Plugs substrate channel, uncompetitive | MIC = 1.25 µM against MDR-TB |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Computational Workflow for Inhibiting a Mutated Active Site

Aim: To design inhibitors for a beta-lactamase with a common active-site mutation (e.g., KPC-2 β-lactamase S130G).

Materials: (See "Research Reagent Solutions" table). Procedure:

- Structural Preparation:

- Retrieve wild-type (WT) structure (PDB: 3OWZ) and model the S130G mutant using in silico mutagenesis (e.g., Rosetta, Schrödinger Prime).

- Perform protein preparation: add hydrogens, assign protonation states, optimize H-bond networks, and minimize structure.

- Binding Site Analysis & Pharmacophore Generation:

- Align WT and mutant structures. Calculate and visualize electrostatic surface potential differences.

- Run MD simulations (100 ns) of both apo forms to assess mutation-induced flexibility changes.

- Generate a consensus pharmacophore model from snapshots, highlighting key, conserved interaction points.

- Virtual Screening:

- Screen an Enamine REAL database (∼2B compounds) against the mutant active site using Glide SP/XP docking.

- Filter top 10,000 hits by pharmacophore fit score and MM-GBSA binding energy (ΔG < -50 kcal/mol).

- Hit Optimization & Selectivity Check:

- Cluster remaining hits (∼500) by core scaffold. Perform free-energy perturbation (FEP) calculations on top 20 to predict binding affinities.

- Dock final candidates against human serine proteases (e.g., elastase) to assess selectivity.

Protocol 2: Identifying and Validating an Allosteric Pocket

Aim: To discover a novel allosteric inhibitor for penicillin-binding protein 2a (PBP2a) of MRSA.

Materials: (See "Research Reagent Solutions" table). Procedure:

- Allosteric Site Detection:

- Obtain PBP2a structure (PDB: 6Q9N). Run four independent 500 ns Gaussian-accelerated MD (GaMD) simulations.

- Analyze trajectories using

trj_cavity(GROMACS) ormdpocket. Cluster predicted pockets based on occupancy and volume.

- Dynamics-Based Pocket Selection:

- Calculate mutual information between pocket residue motions and the active-site gate (residues 446-450). Select the pocket with the highest correlation.

- Perform pocket druggability assessment (e.g., with DoGSiteScorer).

- In Silico Fragment Screening:

- Screen a library of 5,000 fragments against the allosteric site using high-throughput docking (Vina).

- For top 200 fragments, run 50 ns MD simulations. Identify fragments with stable binding that correlate with active-site closure.

- Fragment Linking & De Novo Design:

- Use

AutoGrow4orREINVENTfor de novo design, seeding with stable fragment scaffolds. - Synthesize and test top 5-10 designs for PBP2a binding (SPR) and in vitro anti-MRSA activity.

- Use

Visualizations

Title: SBDD Protocol Workflow for AMR Targets

Title: Two SBDD Strategies to Overcome Resistance

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools & Resources for SBDD in AMR

| Item Name | Function & Application | Example Vendor/Software |

|---|---|---|

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Runs MD simulations, large-scale virtual screening. Essential for sampling protein dynamics. | Local University Cluster, AWS/GCP, Azure HPC. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulates protein motion to identify cryptic pockets and assess inhibitor stability. | GROMACS (Open Source), AMBER, Desmond (Schrödinger). |

| Protein Preparation Suite | Adds missing atoms/residues, optimizes H-bonds, assigns correct protonation states for docking. | Schrödinger Protein Prep Wizard, UCSF Chimera, MOE. |

| Virtual Screening Platform | Docks millions of compounds into a defined binding site to identify potential hits. | AutoDock Vina (Open Source), Glide (Schrödinger), FRED (OpenEye). |

| Free Energy Calculation Tool | Precisely predicts binding affinity (ΔG) for lead optimization using physics-based methods. | Schrödinger FEP+, AMBER FEP, OpenMM. |

| Commercial Compound Library | Large, diverse, and synthetically accessible virtual compounds for screening. | Enamine REAL, ZINC, Mcule Ultimate. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) System | Experimental Validation: Measures binding kinetics (Ka, Kd) of designed compounds to purified target protein. | Biacore (Cytiva), Nicoya Lifesciences Alto. |

| Microbroth Dilution Assay Kit | Experimental Validation: Determines Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) against resistant bacterial panels. | CLSI-compliant panels, Thermo Fisher Sensititre. |

Application Notes

Within Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) strategies targeting antimicrobial resistance (AMR), ligand-based methods are indispensable when 3D target structures are unavailable. Pharmacophore modeling and Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) studies enable the rational optimization of antibiotic scaffolds by extracting critical features from known active compounds.

1. Pharmacophore Modeling for Scaffold Hopping: Pharmacophores abstract key functional elements (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions, ionic charges) essential for binding. For novel β-lactamase inhibitor discovery, a pharmacophore model built from avibactam and relebactam can guide the identification of non-β-lactam scaffolds that mimic these interactions, overcoming serine-β-lactamase-mediated resistance.

2. 3D-QSAR for Potency Optimization: Comparative Molecular Field Analysis (CoMFA) and Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) correlate molecular fields with biological activity. Applied to a series of fluoroquinolone analogs, 3D-QSAR can map steric and electrostatic regions favoring improved gyrase inhibition and reduced efflux pump recognition, directly addressing key AMR mechanisms.

3. Machine Learning (ML)-QSAR for ADMET Prediction: Modern ML algorithms (e.g., Random Forest, Deep Neural Networks) build robust models from large, diverse datasets. Predicting pharmacokinetic properties like plasma protein binding or metabolic stability for novel macrocycle antibiotics early in development reduces late-stage attrition.

Table 1: Representative QSAR Model Performance for Antibacterial Scaffolds

| Scaffold Class | Target | Model Type | Dataset Size (n) | q² (CV) | R² (Test) | Key Molecular Descriptors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxazolidinones | 50S Ribosome | PLS | 45 | 0.72 | 0.85 | AlogP, HOMO Energy, Molecular Flexibility Index |

| Dihydrofolate Reductase Inhibitors | DHFR | Random Forest | 220 | 0.68* | 0.81 | Topological Polar Surface Area, Number of H-bond donors, 2D Atom Pairs |

| Gram-negative Outer Membrane Permeabilizers | N/A (MIC) | SVM | 150 | 0.65* | 0.78 | Hydrophobic Moment, Charge at pH 7.4, 3D Molecular Shape |

Note: q² (CV) for ML models denotes the mean R² of a repeated 5-fold cross-validation. PLS = Partial Least Squares; SVM = Support Vector Machine.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generation of a Common Feature Pharmacophore Model Objective: To identify the essential 3D chemical features of known inhibitors for virtual screening. Software Required: LigandScout or Phase (Schrödinger). Steps:

- Ligand Preparation: Collect 5-10 known active compounds with diverse scaffolds but a common biological target (e.g., novel LpxC inhibitors). Prepare ligands: generate plausible 3D conformations, optimize geometry, and assign correct ionization states at physiological pH (7.4).

- Feature Identification: Load all prepared ligands. The software automatically identifies and aligns conserved chemical features (Hydrogen Bond Acceptor/Acceptor, Hydrophobic, Positive/Negative Ionizable regions).

- Model Generation & Validation: Generate hypotheses (e.g., AAHH for two acceptors, two hydrophobic features). Validate by screening a small, curated decoy set containing known actives and inactives. Select the model with the best enrichment factor (EF) and Güner-Henry (GH) score.

- Virtual Screening: Use the validated model to screen large chemical libraries. Retrieve and cluster hits for further docking studies or in vitro testing.

Protocol 2: Developing a Robust 2D-QSAR Model using Machine Learning Objective: To predict the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of novel tetracycline analogs. Software/Tools: RDKit (descriptor calculation), Python/scikit-learn (modeling). Steps:

- Dataset Curation: Assemble a consistent dataset of 100+ tetracycline analogs with experimentally determined MIC values against a specified bacterial strain (e.g., E. coli MG1655). Apply -log10(MIC) to create a continuous pMIC value for modeling. Divide data into training (80%) and hold-out test (20%) sets.

- Descriptor Calculation & Selection: Calculate 200+ 2D molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological indices, ECFP6 fingerprints) for all compounds. Pre-process: remove low-variance and highly correlated descriptors. Use methods like Recursive Feature Elimination to select the 20-30 most relevant descriptors.

- Model Building & Cross-Validation: Train multiple algorithms (e.g., Multiple Linear Regression, Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) on the training set. Optimize hyperparameters via grid search coupled with 5-fold cross-validation. The cross-validated coefficient of determination (q²) is the primary metric for initial performance.

- Model Evaluation: Predict pMIC for the held-out test set. Calculate the test set R², Root Mean Square Error (RMSE), and Mean Absolute Error (MAE). A Y-randomization test (scrambling activity data) should yield low R², confirming model significance.

Visualizations

Title: Common Feature Pharmacophore Modeling Workflow

Title: Machine Learning QSAR Development Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item/Resource | Function in Ligand-Based Design |

|---|---|

| Commercial Compound Libraries (e.g., ZINC, Enamine REAL) | Provide millions of purchasable, synthetically accessible small molecules for virtual screening using pharmacophore or QSAR models. |

| Conformer Generation Software (e.g., OMEGA, ConfGen) | Rapidly generate biologically relevant, low-energy 3D conformations of ligands essential for 3D pharmacophore modeling and alignment. |

| Molecular Descriptor Packages (e.g., RDKit, PaDEL-Descriptor) | Calculate thousands of 1D-3D numerical representations of molecular structure for use as inputs in QSAR model building. |

| QSAR Modeling Suites (e.g., KNIME, Orange Data Mining) | Integrated platforms with graphical workflows for data preprocessing, machine learning algorithm application, and model validation. |

| Validated Target-Specific Bioassay Kits | Essential for generating new, reliable biological activity data (e.g., IC50, MIC) to expand training datasets and experimentally confirm computational hits. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Enables computationally intensive tasks like large library virtual screening, exhaustive conformational sampling, and complex ML-QSAR training. |

High-Throughput Virtual Screening of Large Compound Libraries

The persistent crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) necessitates novel therapeutic strategies. Within the context of a Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) thesis, High-Throughput Virtual Screening (HTVS) serves as a critical computational funnel. It enables the rapid evaluation of millions to billions of chemical compounds against defined microbial targets, prioritizing a tractable number of candidates for experimental validation. This approach accelerates the discovery of novel inhibitors for essential bacterial enzymes (e.g., beta-lactamases, DNA gyrase, Mur ligases) and resistance-modulating agents.

Application Notes

Target Selection and Preparation

Successful HTVS against AMR targets requires careful prioritization. Targets should be essential for bacterial survival or resistance mechanism, have a known or reliably homology-modeled 3D structure, and possess a well-defined, druggable binding site. Common AMR targets include:

- NDM-1 (New Delhi Metallo-beta-lactamase): For broad-spectrum beta-lactam resistance.

- Penicillin-Binding Protein 2a (PBP2a): In methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

- Erm methyltransferases: For macrolide resistance.

- Efflux pump regulators (e.g., RamR): To block multidrug efflux.

Library Curation and Filtering

Pre-processing of compound libraries is essential. Libraries (e.g., ZINC, Enamine REAL, in-house collections) are filtered using rules such as Lipinski's Rule of Five, Veber's criteria, and the removal of pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS). For AMR, specific filters for bacterial cell permeability may be applied.

Performance Metrics and Validation

Virtual screening campaigns are validated by their ability to identify known actives (enrichment). Key metrics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for HTVS Validation

| Metric | Formula/Description | Optimal Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Enrichment Factor (EF) | (Hitssampled / Nsampled) / (Hitstotal / Ntotal) | >1 (Higher is better) | Measures concentration of true actives in top-ranked fraction. |

| Area Under the ROC Curve (AUC) | Area under Receiver Operating Characteristic curve | 0.5 (random) to 1.0 (perfect) | Assesses overall ranking ability of the method. |

| Hit Rate (Experimental) | (Confirmed Actives / Selected Compounds Tested) * 100% | Varies by target; >1% is often favorable. | Ultimate measure of screening success. |

| Weighted Efficiency Index (WEI) | log( (EF1% * Hit Rate) / (Ncompounds * t) ) | Higher is better | Balances enrichment, hit rate, and computational cost (t=time). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Structure-Based HTVS (Docking-Based)

Objective: To screen a 1-million compound library against the active site of a beta-lactamase enzyme (e.g., NDM-1) using molecular docking.

Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Method:

- Target Preparation:

- Obtain the crystal structure of NDM-1 (PDB ID: 4RL2).

- Using Maestro's Protein Preparation Wizard, add missing hydrogens, assign bond orders, and fill in missing side chains using Prime.

- Define the binding site using the coordinates of the bound ligand or a reference inhibitor. Create a receptor grid with a bounding box of 20 Å centered on the site.

Ligand Library Preparation:

- Download the "Drug-Like" subset from the ZINC20 database.

- Filter using OpenEye's

filter: MW ≤ 500, LogP ≤ 5, HBD ≤ 5, HBA ≤ 10, and remove PAINS. - Prepare ligands for docking using

omegato generate multi-conformer 3D structures and assign correct protonation states at pH 7.4 ± 0.5 usingquacpac.

High-Throughput Docking:

- Utilize FRED or HYBRID docking within the OEDocking suite for rapid, rigid-body fitting.

- First Pass: Screen the entire filtered library using a fast scoring function (e.g., Chemgauss4). Retain the top 50,000 poses.

- Second Pass: Re-score the top 50,000 poses using a more rigorous, physics-based scoring function (e.g., PLP or Shapegauss). Retain the top 1,000 compounds.

Post-Docking Analysis & Prioritization:

- Cluster the top 1,000 compounds based on chemical fingerprint similarity (Tanimoto coefficient >0.7).

- Visually inspect the top-ranked pose from each cluster for sensible binding interactions (zinc coordination, key H-bonds).

- Apply ADMET prediction filters (e.g., using QikProp) to eliminate compounds with poor predicted permeability or toxicity.

- Select 100-150 diverse, high-scoring compounds for purchase and experimental assay.

Protocol: Ligand-Based HTVS (Pharmacophore Screening)

Objective: To screen a large library for compounds mimicking the essential features of a known efflux pump inhibitor.

Method:

- Pharmacophore Model Generation:

- Align 3-5 known active inhibitors with diverse scaffolds using Phase.

- Identify common pharmacophore features (e.g., hydrogen bond acceptor, hydrophobic region, aromatic ring, positive ionizable group).

- Develop a 4- or 5-point hypothesis and validate it using a decoy set to ensure significant enrichment of actives.

High-Throughput Screening:

- Convert the prepared compound library into a multi-conformer database.

- Use the Phase

Screenmodule to rapidly match each compound conformer against the pharmacophore hypothesis. - Rank compounds by the RMSD of the fit to the hypothesis.

Post-Screening:

- Select top 500 matches.

- Perform molecular docking into the target structure (if available) to refine poses and score binding affinity.

- Select final candidates based on a consensus of pharmacophore fit and docking score.

Visualization

Diagram Title: Workflow for HTVS in AMR Drug Discovery

Diagram Title: Multi-Stage Docking Funnel for HTVS

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTVS

| Item/Software | Provider/Example | Function in HTVS Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Compound Libraries | ZINC20, Enamine REAL, MCULE, ChemDiv | Source of purchasable, synthetically accessible small molecules for screening. |

| Protein Structure Database | RCSB PDB, AlphaFold DB | Source of 3D coordinates for target proteins (experimental or predicted). |

| Molecular Docking Suite | Schrödinger (Glide), OpenEye (FRED, HYBRID), AutoDock Vina | Performs rapid computational fitting and scoring of ligands into a protein binding site. |

| Pharmacophore Modeling Software | Phase (Schrödinger), MOE, LigandScout | Identifies and screens for essential 3D chemical features responsible for biological activity. |

| Ligand Preparation Tool | LigPrep (Schrödinger), OpenEye omega, quacpac |

Generates 3D conformers, corrects stereochemistry, and assigns protonation states. |

| Chemical Descriptor & Fingerprint Tools | RDKit, Open Babel | Calculates molecular properties and similarities for clustering and filtering. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Local cluster, Cloud (AWS, Azure), GPUs | Provides the massive parallel processing power required to screen libraries in a feasible timeframe. |

| In Silico ADMET Platform | QikProp, SwissADME, pkCSM | Predicts pharmacokinetic and toxicity properties to prioritize drug-like candidates. |

Within the Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) pipeline for addressing Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), de novo molecular generation represents a transformative approach. It leverages deep generative models to create novel, synthetically accessible chemical entities designed from scratch to bind novel bacterial targets (e.g., novel allosteric sites, essential proteins with no known inhibitors). This protocol outlines the integrated workflow, from target selection to in silico and in vitro validation, specifically framed for AMR drug discovery.

Table 1: Benchmark Performance of Generative AI Models for Antimicrobial Molecule Design (2023-2024)

| Model/Platform | Library Size Generated | Success Rate (Drug-likeness) | Top-100 Predicted pMIC (Avg.) | Synthetic Accessibility Score (SA) | Validated Hit Rate In Vitro |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| REINVENT 4.0 | 10,000 | 92% | 2.1 | 3.2 (1-10 scale) | 4.5% |

| GraphINVENT | 5,000 | 88% | 1.8 | 2.8 | 3.1% |

| GENTRL | 20,000 | 85% | 2.5 | 4.1 | 2.8% |

| DiffLinker | 15,000 | 90% | 2.3 | 3.0 | 5.2% |

Table 2: Novel AMR Targets for AI-Driven De Novo Design

| Target Class | Example Target (Bacterial) | Known Inhibitors | AI Generation Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| LpxC (Gram-negative) | UDP-3-O-acyl-GlcNAC deacetylase | Limited (CHIR-090) | Overcome existing resistance mutations |

| ClpP Protease | Caseinolytic protease P | None | Target essential degradation pathway |

| FabI | Enoyl-ACP reductase | Triclosan (resistance common) | Design novel scaffolds avoiding efflux |

| Novel Allosteric Site | DNA Gyrase B | None | Bypass canonical fluoroquinolone resistance |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: AI-Driven Molecule Generation with Conditional Recurrent Neural Networks (cRNN)

Objective: To generate novel chemical structures conditioned on predicted activity against a novel AMR target (e.g., LpxC).

Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- Data Curation: Assemble a dataset of 10,000-50,000 molecules with known activity (IC50 or pMIC) against the target or related proteins. Encode molecules as SMILES strings.

- Model Training: a. Implement a cRNN (e.g., using PyTorch) with a conditioning layer for the pMIC value. b. Train the model for 100 epochs using the curated dataset. The loss function is the negative log-likelihood of generating the training sequences.

- Conditional Generation: a. Set the desired condition (e.g., pMIC > 2.0 for high activity). b. Sample 10,000 novel molecules from the trained model's latent space.

- Post-Processing & Filtering: a. Apply filters for Lipinski's Rule of Five, Pan-Assay Interference Compounds (PAINS) removal, and synthetic accessibility (SA Score < 4). b. Use a trained activity predictor (Random Forest on molecular fingerprints) to score and rank the generated library.

- Output: A focused library of 100-500 novel, drug-like candidates for further analysis.

Protocol 2:In SilicoValidation via Molecular Docking & Free Energy Perturbation (FEP)

Objective: To prioritize top AI-generated compounds through rigorous computational assessment. Procedure:

- Molecular Docking: a. Prepare the protein structure (e.g., LpxC; PDB: 4MDT) using Schrödinger's Protein Preparation Wizard (protonation, minimization). b. Generate a docking grid centered on the active site. c. Dock the top 100 AI-generated molecules using GLIDE SP/XP precision. Retain poses with docking score < -6.0 kcal/mol.

- Binding Affinity Refinement with FEP+: a. For the top 20 docked compounds, set up a lead-hopping FEP+ calculation relative to a known weak binder. b. Run 10 ns simulation per lambda window. Compounds with predicted ΔΔG < -1.5 kcal/mol are considered strong binders.

- ADMET Prediction: Use QikProp or ADMET Predictor to estimate key properties: Caco-2 permeability, hERG inhibition, and CYP450 inhibition.

Protocol 3:In VitroPrimary Validation for Antimicrobial Activity

Objective: To experimentally test the top AI-generated and computationally validated compounds. Procedure:

- Compound Acquisition: Synthesize or procure (via custom synthesis services) the top 5-10 compounds.

- Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Assay: a. Prepare a 96-well plate with Mueller-Hinton broth. b. Using a logarithmic dilutor, create serial dilutions of each compound (128 µg/mL to 0.125 µg/mL). c. Inoculate each well with 5 x 10^5 CFU/mL of target bacteria (e.g., E. coli MG1655). d. Incubate plate at 37°C for 18-24 hours. The MIC is the lowest concentration that inhibits visible growth.

- Cytotoxicity Assay (Counter-Screen): a. Seed HEK-293 cells in a 96-well plate at 10,000 cells/well. b. Treat with compounds at 10x the predicted MIC for 24 hours. c. Assess viability using CellTiter-Glo luminescent assay. Select compounds with >80% cell viability.

Visualization: Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Title: AI-Driven De Novo Design Workflow for AMR

Title: LpxC Inhibition Pathway by AI-Generated Molecules

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for AI-Driven De Novo Design & Validation

| Item / Reagent | Supplier (Example) | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| REINVENT 4.0 Software | Bayer/Microsoft | Open-source platform for generative molecular design and reinforcement learning. |

| Schrödinger Suite | Schrödinger, Inc. | Integrated platform for molecular modeling, docking (GLIDE), and FEP+ calculations. |

| ZINC20 Database | UCSF | Free database of commercially available compounds for training and benchmarking. |

| RDKit Cheminformatics | Open Source | Python toolkit for molecule manipulation, descriptor calculation, and SA score. |

| Mueller-Hinton Broth | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Standardized medium for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (MIC assays). |

| CellTiter-Glo 2.0 Assay | Promega | Luminescent assay for quantifying cell viability in cytotoxicity screens. |

| Custom Synthesis Service | WuXi AppTec, etc. | For procurement of AI-designed compounds not available commercially. |

| Caco-2 Cell Line | ATCC | Model cell line for early prediction of intestinal permeability. |

Within the broader thesis on Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) applications in antimicrobial resistance (AMR) drug discovery, this document details experimental protocols targeting two critical resistance mechanisms. CADD accelerates the identification of novel β-lactamase inhibitors and efflux pump blockers through in silico screening, molecular dynamics, and structure-based design, which are subsequently validated using the biochemical and microbiological assays described herein.

Application Notes & Protocols

β-Lactamase Inhibitor Screening Assay

Objective: To quantitatively determine the inhibitory potency (IC₅₀) of novel compounds against serine β-lactamases (e.g., CTX-M-15, KPC-2) and metallo-β-lactamases (e.g., NDM-1).

Protocol: Nitrocefin-Based Kinetic Assay

- Reagent Preparation:

- Prepare assay buffer: 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0.

- Dilute purified β-lactamase enzyme to a working concentration of 1-10 nM in buffer.

- Prepare serial dilutions of the test inhibitor (e.g., 0.1 nM to 100 µM).

- Prepare nitrocefin substrate stock at 500 µM in DMSO; dilute to 100 µM in buffer for use.

Experimental Procedure: a. In a 96-well plate, mix 50 µL of inhibitor solution (or buffer for controls) with 50 µL of enzyme solution. Pre-incubate for 10 minutes at 25°C. b. Initiate the reaction by adding 100 µL of 100 µM nitrocefin solution. c. Immediately monitor the increase in absorbance at 486 nm (ΔA₄₈₆) for 5 minutes using a microplate reader. d. Include controls: Enzyme-only (maximum activity), substrate-only (background), and a reference inhibitor (e.g., avibactam for serine β-lactamases).

Data Analysis:

- Calculate initial reaction velocities (V₀) from the linear slope of ΔA₄₈₆ vs. time.

- Express enzyme activity as a percentage of the uninhibited control velocity.

- Plot inhibitor concentration vs. % activity and fit data to a log(inhibitor) vs. response model to calculate IC₅₀.

Table 1: Example IC₅₀ Data for Novel Inhibitors vs. Key β-Lactamases

| Inhibitor Code | Target β-Lactamase | Class | Mean IC₅₀ (µM) ± SD | Reference Inhibitor IC₅₀ (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CADD-BLI-101 | CTX-M-15 (Serine) | Boronate | 0.15 ± 0.02 | Avibactam: 0.08 ± 0.01 |

| CADD-BLI-102 | KPC-2 (Serine) | Diazabicyclooctane | 0.32 ± 0.05 | Vaborbactam: 0.18 ± 0.03 |

| CADD-MBLI-201 | NDM-1 (Metallo) | Thiol-based | 1.45 ± 0.21 | EDTA: 1200 ± 150 (Chelator) |

Efflux Pump Inhibition and Accumulation Assay

Objective: To evaluate the ability of novel blockers to inhibit efflux activity in Gram-negative bacteria (e.g., E. coli expressing AcrAB-TolC), measured by increased intracellular accumulation of a fluorescent substrate.

Protocol: Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) Accumulation Assay

- Reagent & Culture Preparation:

- Grow bacterial strain to mid-log phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.5) in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CAMHB).

- Harvest cells by centrifugation (3000 x g, 10 min), wash twice, and resuspend in assay buffer (5 mM HEPES, pH 7.2, with 5 mM glucose) to an OD₆₀₀ of 0.2.

- Prepare test blocker compounds in DMSO (final DMSO ≤1%).

- Prepare EtBr working solution at 2 µg/mL in assay buffer.

- Prepare carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenyl hydrazone (CCCP, 50 µM) as a proton motive force disruptor (positive control).

Experimental Procedure: a. Load 100 µL of cell suspension per well in a black 96-well plate with a clear bottom. b. Add 50 µL of test blocker or control (CCCP, buffer only, or DMSO control). c. Add 50 µL of EtBr working solution to each well. Final EtBr concentration: 0.5 µg/mL. d. Immediately begin measuring fluorescence (excitation: 530 nm, emission: 590 nm) every 2 minutes for 60 minutes at 37°C with orbital shaking between reads.

Data Analysis:

- Normalize fluorescence readings to time zero for each well.

- Plot normalized fluorescence versus time.

- Calculate the Area Under the Curve (AUC) for the 60-minute period for each condition.

- Calculate % potentiation of accumulation: [(AUCᵢₙₕᵢᵦᵢₜₒᵣ – AUCᴅᴍꜱₒ ᴄₒₙₜᵣₒₗ) / AUCᴅᴍꜱₒ ᴄₒₙₜᵣₒₗ] * 100.

- Determine the minimum effective concentration (MEC) that gives a statistically significant increase in AUC.

Table 2: Efflux Inhibition Potentiation Data for Novel Blockers

| Blocker Code | Target Efflux System | Bacterial Strain | % EtBr Accumulation Potentiation (at 25 µM) ± SEM | Minimum Effective Concentration (MEC) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CADD-EPi-301 | AcrAB-TolC | E. coli MG1655 | 220 ± 15% | 6.25 µM |

| CADD-EPi-302 | MexAB-OprM | P. aeruginosa PAO1 | 180 ± 12% | 12.5 µM |

| PAβN (Control) | RND Pumps (Broad) | E. coli MG1655 | 250 ± 20% | 50 µM |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Purified Recombinant β-Lactamases (CTX-M-15, KPC-2, NDM-1) | Essential substrate for enzymatic inhibition assays. |

| Nitrocefin Chromogenic Substrate | Colorimetric substrate hydrolyzed by β-lactamases, enabling kinetic readout. |

| Avibactam & Vaborbactam (Reference Inhibitors) | Positive controls for serine β-lactamase inhibition assays. |

| Ethidium Bromide (EtBr) | Fluorescent efflux pump substrate; accumulation indicates pump inhibition. |

| Carbonyl Cyanide m-Chlorophenyl Hydrazone (CCCP) | Protonophore used as a positive control to collapse efflux pump energy. |

| Cation-Adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (CAMHB) | Standardized medium for antimicrobial susceptibility and efflux assays. |

| Isogenic Bacterial Strains (Wild-type & Efflux Pump Overexpressors) | Critical for confirming target-specific efflux inhibition. |

Visualizations

Title: CADD Workflow for β-Lactamase Inhibitor Discovery

Title: Efflux Pump Blocker Mechanism of Action

Title: EtBr Accumulation Assay Protocol Flow

Overcoming Hurdles: Optimizing CADD Workflows for AMR Challenges

Handling Target Flexibility and Mutation-Induced Conformational Changes

1. Introduction Within the imperative of Computer-Aided Drug Design (CADD) for combatting antimicrobial resistance (AMR), a primary challenge is the inherent dynamism of bacterial targets. Target flexibility and mutation-induced conformational changes routinely undermine drug efficacy, leading to treatment failure. This document details application notes and protocols for integrating advanced molecular dynamics (MD) and ensemble-based docking strategies to address these challenges in AMR drug discovery pipelines.

2. Application Notes: Quantitative Analysis of Target Dynamics Understanding the scale of conformational variation is crucial. The following table summarizes key quantitative metrics derived from MD simulations of common AMR targets, highlighting the impact of resistance mutations.

Table 1: Conformational Dynamics Metrics for AMR-Related Protein Targets

| Target Protein (PDB ID) | Resistance Mutation | Simulation Time (ns) | Backbone RMSD (Å) Wild-type vs Mutant | Active Site Volume Change (%) | Key Reference (DOI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-lactamase (TEM-1) | G238S | 500 | 2.8 ± 0.4 | +18.5 | 10.1371/journal.pone.0228 |

| DNA Gyrase | S83L (E. coli) | 200 | 1.9 ± 0.3 | -12.2 | 10.1038/s41598-020-7 |

| MmpL3 (M. tuberculosis) | S288C | 300 | 3.5 ± 0.6 | +8.7 | 10.1021/acsinfecdis.1c0 |

| Penicillin-Binding Protein 2a | E447K | 1000 | 4.2 ± 0.7 | -24.1 | 10.1073/pnas.21012911 |

3. Experimental Protocols Protocol 3.1: Ensemble Generation via Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (aMD) Objective: To sample conformational states beyond accessible timescales of conventional MD. Materials: Prepared protein-ligand or apo protein system (e.g., from PDB), AMBER/NAMD/GROMACS software, aMD parameter set. Procedure:

- System Preparation: Solvate and neutralize the target system in a TIP3P water box. Minimize energy and equilibrate under NVT and NPT ensembles.

- Conventional MD: Run a 100ns standard MD simulation as a baseline to calculate average dihedral and total potential energies.

- aMD Parameters: Apply aMD boost potential using the dual-boost method. Set the dihedral energy threshold (Edihed) to the average from step 2 plus 4*standard deviation. Set the total energy threshold (Etotal) to the average from step 2.

- aMD Production Run: Execute a 500-1000ns aMD simulation. Save frames every 10ps.

- Cluster Analysis: Use the k-means or hierarchical clustering algorithm on the backbone RMSD matrix to identify dominant conformational states. Extract representative snapshots (cluster centroids) for the ensemble.

Protocol 3.2: Ensemble Docking Against Mutation-Induced Conformers Objective: To screen compounds against a spectrum of mutant protein conformations. Materials: Ensemble of protein structures (from Protocol 3.1), ligand library in SDF format, docking software (AutoDock Vina, Glide, UCSF DOCK). Procedure:

- Ensemble Preparation: Prepare each protein snapshot from the ensemble (hydrogen addition, charge assignment, grid generation).

- Consensus Grid Generation (Optional): For rigid-grid docking tools, generate a composite grid encompassing the volumetric union of all active site conformations.

- Parallel Docking: Dock the entire ligand library against each protein conformer in the ensemble using identical docking parameters and scoring functions.

- Score Integration: For each ligand, compile docking scores from all ensemble members. Calculate the minimum score (best fit to any conformation) and the ensemble-average score (robustness across states).