Genome Assembly Algorithms Compared: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of genome assembly algorithms, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Genome Assembly Algorithms Compared: A Practical Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of genome assembly algorithms, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of de novo and reference-guided assembly, the practical application of Overlap-Layout-Consensus (OLC) and de Bruijn Graph methods for short and long reads, and strategies for troubleshooting common issues like repeats and sequencing errors. Furthermore, it details rigorous methods for validating assembly quality using modern tools and metrics, empowering scientists to select the optimal assembly strategy for their projects, ultimately enhancing the reliability of genomic data in biomedical discovery.

The Genome Assembly Puzzle: Core Concepts and Inherent Challenges

Genome assembly is a fundamental process in genomics that involves reconstructing the original DNA sequence of an organism from shorter, fragmented sequencing reads [1]. The field has evolved significantly from early Sanger sequencing methods to the current era of third-generation long-read technologies, yet the computational challenge of accurately piecing together a genome remains [1] [2]. Two principal strategies have emerged: de novo assembly, which reconstructs the genome without a prior template, and reference-guided assembly, which uses a related genome as a scaffold. The choice between these approaches carries profound implications for downstream biological interpretation, particularly in comparative genomics, variant discovery, and clinical applications [3] [4]. Within the broader context of genome assembly algorithm comparison research, understanding the technical specifications, performance characteristics, and appropriate applications of each method is paramount for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to leverage genomic information.

Core Concepts and Key Differences

De Novo Genome Assembly

De novo assembly reconstructs genomes directly from sequencing reads without reference to a known genome structure. This approach relies on computational detection of overlapping regions among reads to build longer contiguous sequences (contigs), which are then connected into scaffolds using mate-pair or long-range information [1] [3]. The process is computationally intensive due to challenges posed by repetitive elements, heterozygosity, and sequencing errors [2] [5]. Modern de novo assembly benefits from long-read technologies like PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore, which produce reads tens of kilobases long, helping to span repetitive regions that traditionally fragmented short-read assemblies [6] [2]. Recent achievements include telomere-to-telomere (T2T) gapless assemblies for several eukaryotic species and the development of pangenomes that capture diversity across individuals [2].

Reference-Guided Assembly

Reference-guided assembly utilizes a previously assembled genome from a related species or genotype as a template to guide the reconstruction process [5]. This approach can be implemented through direct read mapping and consensus generation, or through more sophisticated hybrid methods that combine reference mapping with local de novo assembly [7] [8] [5]. The primary advantage lies in reduced computational complexity and the ability to leverage evolutionary conservation between the target and reference organisms [5]. However, reference bias presents a significant limitation, where genomic regions divergent from the reference may be misassembled or omitted entirely [5] [4]. This is particularly problematic for populations or species with significant structural variation relative to the reference [4].

Comparative Analysis: Advantages and Limitations

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of De Novo and Reference-Guided Assembly Approaches

| Feature | De Novo Assembly | Reference-Guided Assembly |

|---|---|---|

| Prerequisite | No prior genomic information required | Requires closely related reference genome |

| Computational Demand | High (memory and processing intensive) | Moderate to low |

| Bias Potential | Free from reference bias | Susceptible to reference bias |

| Variant Discovery | Comprehensive for all variant types | Limited to differences from reference |

| Optimal Use Cases | Novel species, pangenomes, structural variant studies | Population studies, resequencing projects |

| Cost Considerations | Higher due to deep sequencing and computing | Lower for projects with available references |

| Handling Repetitive Regions | Improved with long reads | Dependent on reference quality in repetitive areas |

The fundamental trade-off between these approaches centers on completeness versus efficiency. De novo assembly provides an unbiased representation of the target genome but demands substantial resources [2] [3]. Reference-guided methods offer computational efficiency but risk missing biologically significant regions that diverge from the reference [5] [4]. For populations underrepresented in genomic databases, such as the Kinh Vietnamese population, de novo assembly has proven superior for capturing population-specific variation [4]. Similarly, in invasive species research, de novo assembly followed by population genomics has revealed chromosomal inversions linked to environmental adaptation [9].

Quantitative Comparison of Assembly Performance

Table 2: Performance Metrics from Recent Genome Assembly Studies

| Study/Organism | Assembly Approach | Key Metrics | Biological Insights Gained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Styela plicata (invasive ascidian) [9] | De novo (PacBio CLR, Illumina, Omni-C, RNAseq) | Size: 419.2 Mb, NG50: 24.8 Mb, BUSCO: 92.3% | Chromosomal inversions related to invasive adaptation |

| Kinh Vietnamese genome [4] | De novo (PacBio HiFi + Bionano mapping) | Size: 3.22 Gb, QV: 48, BUSCO: 92%, Scaffold N50: 50 Kbp | Superior variant detection for Vietnamese population |

| Hippobosca camelina (camel ked) [10] | De novo (Nanopore) | Size: 135.6 Mb (female), N50: 1.2 Mb, BUSCO: >94% | Identification of 44 chemosensory genes |

| Simulated plant genome [5] | Reference-guided de novo | Summed z-scores of 36 statistics | Outperformed de novo alone when using related species reference |

Performance assessment requires multiple metrics to evaluate both continuity and accuracy. Common continuity metrics include N50 (length of the shortest contig in the set that contains the fewest longest contigs that collectively represent 50% of assembly size) and BUSCO scores (assessment of completeness based on evolutionarily informed expectations of gene content) [9] [10]. Accuracy is typically evaluated through quality value (QV) scores and k-mer completeness [9] [4]. The development of population-specific reference genomes for the Kinh Vietnamese population demonstrated substantially improved variant calling accuracy compared to standard hg38 reference, highlighting how de novo assemblies can reduce reference bias in genomic studies [4].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: De Novo Genome Assembly Using Long Reads and Hi-C

This protocol outlines the production of a chromosome-level de novo assembly, integrating long-read sequencing with chromatin conformation data for scaffolding [9] [6].

DNA Extraction: High-molecular-weight (HMW) DNA is critical. Use fresh or flash-frozen tissue and extraction methods that minimize shearing (e.g., phenol-chloroform). Assess DNA quality via pulse-field gel electrophoresis or the 4200 TapeStation System, targeting molecules >80-100 kbp [4].

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- PacBio HiFi Library: Shear HMW DNA to 10-15 kbp fragments using g-tubes. Prepare SMRTbell libraries using the SMRTbell Express Template Prep Kit 2.0. Sequence on PacBio Sequel II/Revio systems to generate HiFi reads with minimum Q20 (99%) accuracy [6] [4].

- Hi-C Library: Fix tissue with formaldehyde to crosslink chromatin. Digest with restriction enzyme (e.g., DpnII), mark restriction sites with biotinylated nucleotides, and ligate crosslinked fragments. Shear DNA and pull down biotinylated fragments using streptavidin beads [9] [6].

- Optional Optical Mapping: For additional scaffolding, prepare DNA for Bionano Genomics Saphyr system using the Bionano SP Blood and Cell Culture DNA Isolation protocol [4].

Genome Assembly:

- Initial Assembly: Assemble HiFi reads into contigs using HiFiasm (v0.16.1 or newer) with default parameters [4]. This assembler effectively handles heterozygosity and produces haploid-resolved assemblies.

- Hi-C Scaffolding: Map Hi-C reads to initial contigs using Juicer or similar tools. Use 3D-DNA or SALSA2 to order and orient contigs into chromosomes based on chromatin interaction frequencies [9].

- Integration with Optical Maps: If available, use Bionano Solve software to combine assembly with optical maps, creating super-scaffolds with the "Resolve Conflicts" and "Trim Overlapping Sequence" parameters enabled [4].

Quality Control and Validation: Assess assembly completeness with BUSCO against appropriate lineage datasets. Check for misassemblies using long-read mapping and k-mer analysis. Validate assembly structure through Hi-C contact heatmaps [9] [10].

Protocol 2: Reference-Guided De Novo Assembly Approach

This hybrid approach, adapted from Schneeberger et al. and subsequent improvements, uses a related reference genome to guide assembly while maintaining the ability to detect divergent regions [5].

Read Processing and Quality Control:

- Trim sequencing adapters and quality-trim reads using Trimmomatic (v0.32) with parameters: LEADING:3 TRAILING:3 SLIDINGWINDOW:4:15 MINLEN:40 [5].

- Perform quality assessment with FastQC (v0.10.1).

Reference Mapping and Superblock Definition:

- Map quality-trimmed paired-end reads to the reference genome of a related species using Bowtie2 (v2.2.1) in fast-local mode [5].

- Define "superblocks" - continuous regions with read coverage. Combine adjacent blocks until reaching at least 12 kb, allowing overlaps of 300 bp between superblocks. Split any superblocks exceeding 100 kb [5].

Localized De Novo Assembly:

- Extract reads mapping to each superblock, including unmapped reads with properly mapped mates.

- Perform de novo assembly on each superblock separately using an assembler of choice (e.g., CANU, Flye) [5].

- Separately assemble all completely unmapped reads to capture highly divergent regions.

Redundancy Removal and Integration:

- Assemble contigs from superblocks using the AMOScmp (v3.1.0) Sanger assembler with the reference genome as a guide to remove redundancy from overlapping regions [5].

- Add contigs from the unmapped read assembly to the supercontig set.

- Map all trimmed reads back to the combined supercontigs using Bowtie2 sensitive mode to validate and error-correct.

Final Scaffolding and Evaluation:

- Scaffold using mate-pair or long-range information if available.

- Evaluate using multiple metrics including N50, BUSCO completeness, and consensus quality compared to the original reads [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Genome Assembly

| Category/Item | Specific Examples | Function in Genome Assembly |

|---|---|---|

| Long-read Sequencing Platforms | PacBio Revio/Sequel II, Oxford Nanopore PromethION | Generate long reads (15-20 kb HiFi reads, >100 kb Ultralong) to span repeats and resolve complex regions [6] [2] |

| Short-read Sequencing Platforms | Illumina NovaSeq, NextSeq | Provide high-accuracy reads for polishing and error correction [4] |

| Chromatin Conformation Kits | Dovetail Omni-C, Hi-C Kit | Capture chromatin interactions for chromosome-level scaffolding [9] [6] |

| Optical Mapping Systems | Bionano Saphyr | Generate long-range mapping information for scaffold validation and large SV detection [4] |

| HMW DNA Extraction Kits | Qiagen Blood & Cell Culture DNA Midi Kit, Circulomics Nanobind | Preserve long DNA fragments crucial for long-read technologies [4] |

| Assembly Software | HiFiasm, CANU, Verkko, MetaCompass | Perform core assembly algorithms from read overlap to graph resolution [2] [4] |

| Quality Assessment Tools | BUSCO, Merqury, QUAST | Evaluate assembly completeness, accuracy, and contiguity [9] [10] |

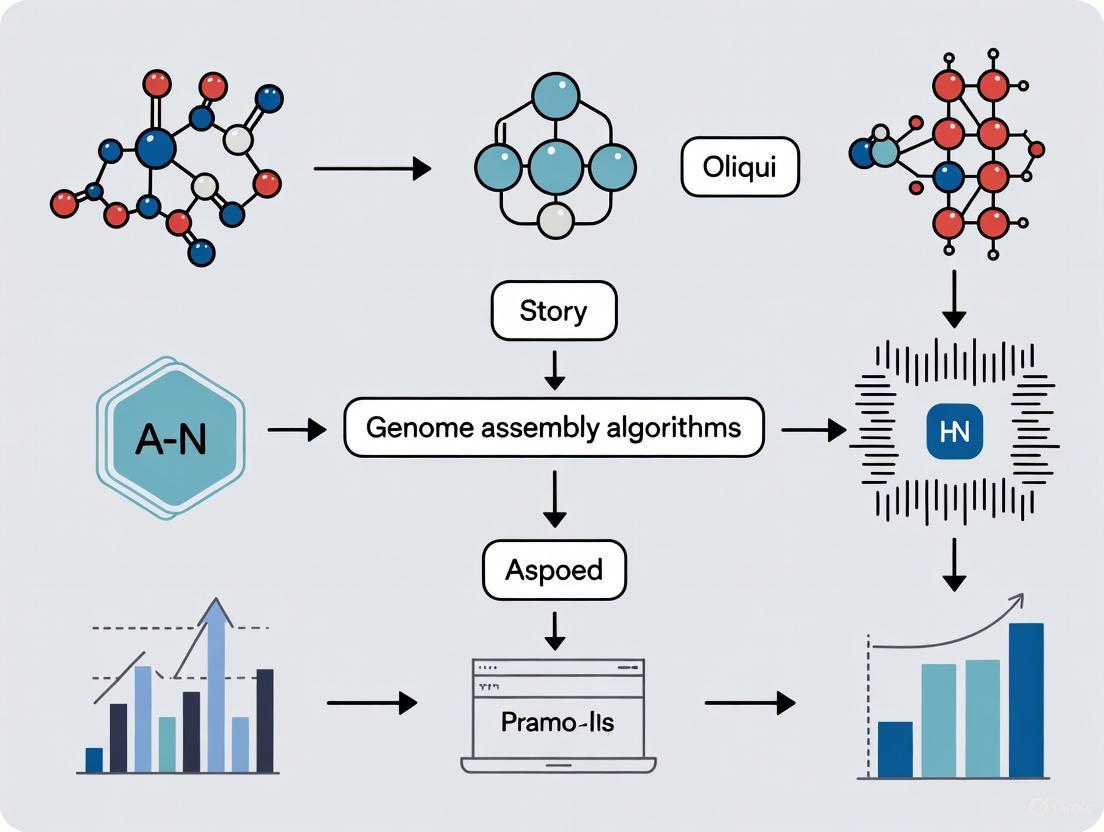

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflows for Genome Assembly Strategies

The strategic selection between de novo and reference-guided assembly approaches represents a critical decision point in genomic research design. De novo assembly provides the comprehensive, unbiased reconstruction necessary for novel species characterization, structural variant discovery, and the creation of pangenome resources [9] [2]. Conversely, reference-guided methods offer computational efficiency and practical advantages for population genomics and clinical applications where high-quality references exist [5] [4]. The emerging paradigm favors de novo assembly as a foundation for population-specific references, particularly for underrepresented groups, as demonstrated by the Kinh Vietnamese genome project [4]. Future directions point toward hybrid approaches that leverage the strengths of both methods, with ongoing innovation in long-read technologies, assembly algorithms, and pangenome representations progressively overcoming current limitations in resolving complex genomic regions [2] [5]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this evolving landscape offers increasingly powerful tools to connect genomic variation with biological function and therapeutic targets.

De novo genome assembly represents a foundational challenge in genomics, tasked with reconstructing an organism's complete DNA sequence from shorter, fragmented sequencing reads. The computational heart of this process lies in its algorithms, which must efficiently and accurately resolve the complex puzzle of read overlap and orientation without a reference blueprint. For decades, two major algorithmic paradigms have dominated this field: Overlap-Layout-Consensus (OLC) and de Bruijn Graphs (DBG) [11] [12]. The fundamental difference between them lies in their initial approach to the reads. The OLC paradigm considers entire reads as the fundamental unit, building a graph of how these complete sequences overlap. In contrast, the DBG method first breaks all reads down into shorter, fixed-length subsequences called k-mers, constructing a graph from the overlap relationships between these k-mers [11] [13]. The choice between these paradigms is not trivial and is critically influenced by the type of sequencing data available, the computational resources at hand, and the biological characteristics of the target genome. This article provides a detailed comparison of the OLC and DBG approaches, offering application notes and protocols to guide researchers in selecting and implementing the appropriate algorithmic strategy for their genome projects.

Algorithmic Foundations and Comparative Analysis

The Overlap-Layout-Consensus (OLC) Paradigm

The OLC strategy, one of the earliest approaches used for Sanger sequencing reads, follows a logically intuitive three-step process mirroring its name [12]. Initially, it performs an all-pairs comparison of reads to identify significant overlaps between a suffix of one read and a prefix of another. The result of this computationally intensive step is an overlap graph, where each node represents a full read, and directed edges connect nodes if their corresponding reads overlap [14] [12]. Subsequently, the layout step analyzes this graph to determine the order and orientation of the reads, aiming to find a path that visits each read exactly once—a concept known as a Hamiltonian path. Finally, the consensus step generates the final genomic sequence by merging the multiple aligned reads from the layout, which helps to cancel out random sequencing errors and produce a high-confidence sequence [15].

A significant limitation of the classical OLC approach is that the layout problem is NP-complete, making it computationally intractable for large datasets [14]. In response, modern assemblers have shifted towards using string graphs, a simplified form of overlap graph that removes redundant information (such as transitively inferable edges), thereby streamlining the graph and making the path-finding problem more manageable [13]. OLC assemblers are particularly well-suited for long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio and Oxford Nanopore) because they preserve the long-range information contained within each read. This makes them powerful for spanning repetitive regions, a major challenge in genome assembly [12] [15]. However, a primary drawback is that the all-pairs overlap calculation has a high computational cost, which becomes prohibitive with the massive datasets generated by short-read technologies [13].

The de Bruijn Graph (DBG) Paradigm

The de Bruijn Graph approach offers a counter-intuitive but highly effective alternative. It bypasses the need for all-pairs read overlap by first shattering every read into a set of shorter, fixed-length k-mers (substrings of length k) [12]. The graph is then constructed such that each node is a unique k-mer. A directed edge connects two k-mers if they appear consecutively in a read and overlap by k-1 nucleotides [13] [12]. For example, if k=3, the reads TAA and AAT would be connected because the suffix AA of the first overlaps the prefix AA of the second.

The assembly process involves traversing this graph to find non-branching paths (contigs), which are reported as the assembled sequences [13]. The DBG strategy is computationally efficient for large volumes of short-read data (like Illumina), as it avoids the quadratic complexity of the OLC overlap step [13] [12]. However, its performance is highly dependent on the choice of the k-mer size (k). A smaller k value increases connectivity, which is beneficial for low-coverage regions, but fails to resolve longer repeats, creating tangled graphs. Conversely, a larger k value can resolve longer repeats but may lead to a fragmented graph in regions of low coverage [12]. To balance these trade-offs, iterative de Bruijn graph approaches have been developed, such as IDBA, which build and refine the graph using multiple values of k, from small to large. This allows contigs from a smaller k to patch gaps in a larger k graph, while the larger k graph helps resolve branches from the smaller k graph [13].

Quantitative Comparison of OLC and DBG Assemblers

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Assembly Algorithms and Their Performance on HiFi Read Data.

| Algorithm / Tool | Primary Paradigm | Key Strength | Optimal Read Type | Computational Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hifiasm [14] [2] | OLC (String Graph) | Haplotype-phased assembly | PacBio HiFi | High |

| HiCanu [14] [15] | OLC | Homopolymer compression; repeat separation | PacBio HiFi | High |

| Canu [15] | OLC (MinHash) | Robust overlap detection for noisy reads | PacBio CLR, Nanopore | High |

| Verkko [14] [2] | Hybrid (OLC & DBG) | Telomere-to-telomere diploid assembly | HiFi + ONT | Very High |

| SPAdes [13] | Iterative DBG | Multi-cell, single-cell assembly | Illumina Short Reads | Moderate |

| IDBA-UD [13] | Iterative DBG | Uneven sequencing depth (e.g., metagenomics) | Illumina Short Reads | Moderate |

| GNNome [14] | AI/Graph Neural Network | Path finding in complex graphs | HiFi / ONT (OLC Graph) | Very High (GPU) |

Table 2: Assembly Performance Metrics on the Homozygous CHM13 Genome Using HiFi Reads (adapted from [14]).

| Assembler | Assembly Size (Mb) | NG50 (Mb) | NGA50 (Mb) | Completeness (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GNNome | 3051 | 111.3 | 111.0 | 99.53 |

| Hifiasm | 3052 | 87.7 | 87.7 | 99.55 |

| HiCanu | 3297 | 69.7 | 69.7 | 99.54 |

| Verkko | 3030 | 9.4 | 9.4 | 99.44 |

Advanced Protocols and Emerging Methods

Protocol: De Novo Assembly Using an OLC-Based Workflow

Application Note: This protocol is optimized for generating a high-quality, contiguous draft genome from PacBio HiFi long-read data using the Hifiasm assembler, which represents the state-of-the-art in the OLC paradigm [14] [2].

Research Reagent & Computational Solutions:

- Sequencing Data: PacBio HiFi reads. HiFi reads provide high accuracy (Q20+) and length (typically 15-20 kb), which are ideal for OLC assembly as they produce long, reliable overlaps [14] [15].

- Assembly Software: Hifiasm (v0.18.7 or newer) [14] [2].

- Compute Infrastructure: High-memory server. A machine with ≥ 1 TB of RAM and multiple CPU cores is recommended for a mammalian-sized genome, as the initial overlap step is memory-intensive.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing: Quality-check raw HiFi reads using FastQC. Typically, HiFi data requires no further error-correction.

- Graph Construction: Run Hifiasm with default parameters to build the phased assembly graph. The command is typically:

hifiasm -o output_prefix.asm -t <number_of_threads> input_reads.fq. - Graph Simplification: Hifiasm automatically performs graph simplification, which includes trimming dead-end spur sequences and resolving small, simple repeats that create "bubbles" in the graph [14].

- Haplotype Resolution: For diploid samples, leverage Hifiasm's integrated phasing to generate two haplotype-resolved assemblies. This utilizes heterozygous sites to separate maternal and paternal sequences [2] [15].

- Output Contigs: The primary output is a set of contig sequences in FASTA format, which represent the paths found through the simplified assembly graph.

Protocol: Scalable Iterative de Bruijn Graph Assembly

Application Note: This protocol outlines a distributed computing approach for assembling large, complex short-read datasets (e.g., from metagenomics or single-cell sequencing) using the DRMI-DBG model, which enhances the iterative DBG paradigm for scalability [13].

Research Reagent & Computational Solutions:

- Sequencing Data: Illumina short-read data.

- Assembly Software: A distributed iterative DBG implementation, such as DRMI-DBG, which leverages Apache Spark and Apache Giraph frameworks [13].

- Compute Infrastructure: A computing cluster with a Hadoop distributed file system (HDFS). The DRMI-DBG model is designed to scale across multiple nodes to handle memory-intensive graphs [13].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- K-mer Spectrum Analysis: Analyze the read set to determine an optimal range of k-values (e.g., from k_min = 21 to k_max = 121 with varying steps) [13].

- Distributed Graph Construction: Use Apache Spark to hash reads into k-mers and construct de Bruijn graphs for different k-values in a parallel, distributed manner across the cluster.

- Iterative Graph Processing: Employ Apache Giraph, a Bulk Synchronous Parallel (BSP) framework, to process the graphs iteratively. The DRMI-DBG algorithm starts with the largest k-value to build a simple initial graph and progressively integrates information from graphs with smaller k-values to connect low-coverage regions and resolve gaps [13].

- Contig Extraction: Traverse the final, refined de Bruijn graph to extract all maximal non-branching paths, which are output as contigs.

Emerging Paradigm: AI-Driven Assembly with GNNome

A novel paradigm is emerging that leverages Geometric Deep Learning to address the critical challenge of path finding within complex assembly graphs. The GNNome framework utilizes Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) trained on telomere-to-telomere reference genomes to analyze a raw OLC assembly graph and assign probabilities to each edge, indicating its likelihood of being part of the correct genomic path [14].

Workflow: The process begins with a standard OLC graph built from HiFi or ONT reads by an assembler like Hifiasm. This graph is fed into a pre-trained GNN model (SymGatedGCN), which performs message-passing across the graph's structure. The model outputs a probability for each edge. A search algorithm then walks through this probability-weighted graph, following high-confidence paths to generate contigs [14]. This method shows great promise in overcoming complex repetitive regions where traditional algorithmic methods often fail, achieving contiguity and quality comparable to state-of-the-art tools on several species [14].

Visualization of Algorithmic Workflows

Table 3: Key Research Reagent and Computational Solutions for Genome Assembly.

| Item Name | Function / Application Note |

|---|---|

| PacBio HiFi Reads | Provides long (typically 15-20 kb), highly accurate (<0.5% error rate) reads. Ideal for OLC assemblers to generate contiguous haploid or haplotype-resolved assemblies [14] [2]. |

| Oxford Nanopore Ultra-Long Reads | Delivers extreme read length (>100 kb), facilitating the spanning of massive repetitive regions. Lower single-read accuracy (~5%) is mitigated by high coverage and hybrid strategies [14] [2]. |

| Illumina Short Reads | Offers massive volumes of high-quality, cheap short reads (150-300 bp). The standard data source for de Bruijn Graph assemblers, especially for small genomes or transcriptomes [13] [12]. |

| Hi-C Sequencing Data | Used for scaffolding assembled contigs into chromosomes. Proximity ligation data reveals long-range interactions, allowing contigs to be ordered, oriented, and grouped [12]. |

| Hifiasm Software | State-of-the-art OLC assembler for PacBio HiFi and ONT data. Particularly effective for haplotype-resolved assembly without parental data [14] [2]. |

| High-Memory Server (≥1 TB RAM) | Essential for OLC assembly of large eukaryotic genomes, as the initial overlap step requires holding all-vs-all overlap information in memory [14]. |

| Apache Spark & Giraph Cluster | Distributed computing frameworks that enable scalable, parallel processing of massive iterative de Bruijn graphs for large or complex short-read datasets [13]. |

The pursuit of complete and accurate genome assemblies is a cornerstone of modern genomics, enabling advances in comparative genetics, medicine, and drug discovery. Despite significant technological progress, three persistent challenges critically impact the quality of assembled genomes: repetitive sequences, sequencing errors, and genetic polymorphism. Repetitive DNA, which can constitute over 80% of some plant genomes and nearly half of the human genome, creates ambiguities in sequence alignment and assembly [16]. Sequencing errors, inherent to all sequencing technologies, introduce noise that can be misinterpreted as biological variation [17]. Furthermore, high levels of genetic polymorphism in diploid or wild populations, a common feature in many species, complicate haplotype resolution and can lead to fragmented assemblies [18]. This application note details these challenges within the context of genome assembly algorithm comparisons, providing structured data, experimental protocols, and analytical workflows to identify, quantify, and mitigate these issues.

The tables below summarize the core quantitative data and common research reagents relevant to these assembly challenges.

Table 1: Impact and Scale of Repetitive Elements in Selected Genomes

| Species | Genome Size | Repeat Content | Major Repeat Classes | Key Challenge for Assembly |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human (Homo sapiens) | ~3.2 Gb | ~50% [16] | Alu, LINE, SINE, Segmental Duplications [16] [19] | Ambiguity in read placement and scaffold mis-joins [16] |

| Maize (Zea mays) | ~2.3 Gb | >80% [16] | Transposable Elements [16] | Collapse of repetitive regions, fragmentation [16] |

| Sea Squirt (Ciona savignyi) | ~190 Mb | Not specified | Not specified | High heterozygosity (4.6%) masquerading as paralogy [18] |

| Orientia tsutsugamushi (Bacterium) | ~2.1 Mb | Up to 40% [16] | Not specified | Difficulty in achieving contiguous assembly [16] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Genome Assembly and Quality Control

| Reagent / Tool Category | Example | Primary Function in Assembly |

|---|---|---|

| Long-Read Sequencing | PacBio HiFi, Oxford Nanopore (ONT) | Generates long reads (kb to Mb) to span repetitive regions and resolve complex haplotypes [20] [2]. |

| Linked-Read / Strand-Specific Sequencing | Strand-seq, Hi-C | Provides long-range phasing information and scaffolds contigs into chromosomes [19] [20]. |

| Optical Mapping | Bionano Genomics | Creates a physical map based on motif patterns to validate scaffold structure and detect large mis-assemblies [19]. |

| Assembly Evaluation Tools | CRAQ, Merqury, QUAST, BUSCO | Assess assembly completeness, base-level accuracy, and structural correctness in a reference-free or reference-based manner [21]. |

| Assembly Algorithms | Verkko, hifiasm, Canu | Performs de novo assembly using specialized strategies for handling repeats and heterozygosity [20] [2]. |

Application Notes and Protocols

Protocol: Identification and Correction of Assembly Errors Using CRAQ

Background: The Clipping information for Revealing Assembly Quality (CRAQ) tool is a reference-free method that maps raw sequencing reads back to a draft assembly to identify regional and structural errors at single-nucleotide resolution. It effectively distinguishes true assembly errors from heterozygous sites or structural differences between haplotypes [21].

Materials:

- Input Data: A draft genome assembly in FASTA format.

- Sequencing Reads: Original NGS short-reads (e.g., Illumina) and/or SMS long-reads (e.g., PacBio HiFi, ONT) used for the assembly.

- Software: CRAQ installed as per developer instructions.

- Computing Resources: A high-performance computing cluster is recommended for large genomes.

Procedure:

- Read Mapping: Map the original NGS and SMS reads back to the draft assembly using a compatible aligner (e.g., minimap2 for long reads).

- Run CRAQ Analysis:

Use the

-sand-lflags to specify BAM files for short and long reads, respectively. - Interpret Output:

- CRAQ generates two primary error classifications: Clip-based Regional Errors (CREs) for small-scale local errors and Clip-based Structural Errors (CSEs) for large-scale mis-joins [21].

- The tool outputs an Assembly Quality Index (AQI), calculated as ( AQI = 100 \cdot e^{-0.1N/L} ), where ( N ) is the normalized error count and ( L ) is the assembly length in megabases. Higher AQI indicates better quality [21].

- Misjoin Correction: CRAQ can output a corrected assembly by breaking contigs at identified CSE breakpoints. This corrected assembly can then be used for downstream scaffold building with Hi-C or optical mapping data [21].

CRAQ Analysis Workflow: This diagram illustrates the process of using raw read mapping and clipping information to classify regions in a draft assembly as errors or heterozygosity.

Protocol: Resolving High Heterozygosity in Diploid Genomes

Background: Conventional assemblers can misinterpret divergent haplotypes in a highly polymorphic diploid individual as separate paralogous loci, leading to a highly fragmented and duplicated assembly. A solution is to separately assemble the two haplotypes before merging them into a final reference [18].

Materials:

- Biological Sample: DNA from a single, diploid, heterozygous individual.

- Sequencing Data: Whole-genome shotgun (WGS) data from libraries with multiple insert sizes (e.g., 5-kb and 40-kb plasmids, Fosmids) to a high depth of coverage (>12x) [18].

- Software: A modified assembler like Arachne with a "splitting rule" constraint to enforce haplotype separation [18]. Modern alternatives include Verkko or hifiasm, which are designed for haplotype-resolved assembly [20] [2].

Procedure:

- Data Generation: Sequence the genome to high coverage using WGS with paired-end reads from multiple insert-size libraries.

- Initial Assembly with Splitting Rule: Run the assembler with parameters that reinforce the separation of polymorphic haplotypes. In Arachne, this involves a constraint that prevents the merging of two reads if they contain an excess of high-quality discrepancies, treating them as coming from different haplotypes [18].

- Form Diploid Scaffolds: Identify long-range correspondences between the separate haplotypic scaffolds using paired-read information.

- Merge Haplotypes: Create a single reference sequence by selecting one representative haplotype at each locus. The choice can be based on factors like contiguity or alignment to a related species' genome.

Haplotype Resolution Strategy: Comparing standard assembly outcomes with the specialized splitting rule approach for polymorphic genomes.

Protocol: Automated Base-Calling Correction Using Assembly Consensus (AutoEditor)

Background: AutoEditor is an algorithm that significantly improves base-calling accuracy by re-analyzing the primary chromatogram data from Sanger sequencing using the consensus of an assembled contig. It reduces erroneous base calls by approximately 80% [17].

Materials:

- Input Data: An initial multiple sequence alignment of reads to a consensus sequence (contig) and the original chromatogram files.

- Software: AutoEditor or a modern equivalent designed for re-calling bases using assembly consensus.

Procedure:

- Generate Input Alignment: Assemble sequencing reads into contigs to create a multiple alignment where each base position is covered by several reads.

- Identify Discrepancy Slices: AutoEditor scans the multiple alignment for "slices" (columns) where base calls disagree. A homogeneous majority is required for correction [17].

- Re-analyze Chromatograms: For each discrepant base, the algorithm re-examines the original chromatogram trace in a "search region" that encompasses the entire local sequence context (e.g., a homopolymer run) [17].

- Correct Errors: Based on the trace re-analysis and the majority consensus, AutoEditor corrects substitution, insertion, and deletion elements. Corrections are made with high accuracy (~1 error per 8828 corrections) [17].

- Re-call Consensus: The final consensus sequence is re-called using the corrected reads, incorporating base quality values, which may involve the use of ambiguity codes.

Discussion

The protocols outlined here provide concrete methodologies for tackling the core challenges in genome assembly. The selection of the appropriate protocol depends on the primary bottleneck. For base-level inaccuracies, especially in Sanger-based projects, an AutoEditor-like approach is powerful [17]. For fragmented assemblies caused by high heterozygosity, a haplotype-separating assembly strategy is essential [18]. Finally, for validating and improving any draft assembly, especially in identifying persistent mis-joins, tools like CRAQ are invaluable [21].

The integration of long-read sequencing technologies and advanced assemblers like Verkko [20] has dramatically improved the ability to navigate repeats and resolve haplotypes. However, as evidenced by the recent complete human genomes, challenges remain in assembling ultra-long tandem repeats and complex structural variants, particularly in centromeric and pericentromeric regions [19] [20] [2]. Continuous development in algorithmic and wet-lab protocols is required to achieve truly complete and accurate genomes for diverse species and individuals, a prerequisite for advancing personalized medicine and understanding genomic diversity.

The selection of sequencing technology is a foundational decision in genomics, directly influencing the contiguity, completeness, and accuracy of genome assemblies. While short-read sequencing has been the cornerstone of genomic studies for decades, offering high base-level accuracy at low cost, long-read sequencing technologies now enable the resolution of complex genomic regions, including repetitive elements and structural variants. This Application Note delineates the technical distinctions between short- and long-read sequencing platforms, provides a quantitative framework for their evaluation, and details a standardized protocol for comparing their performance in genome assembly. The findings underscore that long-read sequencing, particularly high-fidelity (HiFi) methods, produces more complete assemblies, whereas an optimized hybrid approach can yield superior variant calling accuracy for epidemiological studies.

Genome assembly is the process of reconstructing a complete genome from numerous short or long DNA sequences (reads). The choice of sequencing technology imposes fundamental constraints on the design and potential quality of the final assembly.

- Short-Read Sequencing (Second-Generation): Dominated by Illumina sequencing-by-synthesis (SBS) technology, this approach generates reads typically 50-600 bases in length [22] [23]. It is valued for its exceptional throughput and high per-base accuracy (>99.9%) [24]. However, the shortness of the reads complicates the assembly process, making it difficult to resolve repetitive sequences and large structural variations.

- Long-Read Sequencing (Third-Generation): Pioneered by Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT), these platforms sequence single DNA molecules, producing reads that can span thousands to tens of thousands of bases, with some ONT reads exceeding 1 million bases [24] [23]. This inherent length provides the contextual information needed to traverse repetitive regions and phase haplotypes directly. Early long-read technologies suffered from high error rates, but modern iterations, such as PacBio HiFi (circular consensus sequencing), achieve accuracies exceeding 99.9% [23] [25].

The shift towards long-read technologies is driven by their ability to generate more complete and contiguous assemblies, which is critical for comprehensive genomic analysis in fields ranging from rare disease diagnosis to pathogen surveillance [26] [24].

Quantitative Comparison of Sequencing Technologies

The following tables summarize the core characteristics and performance metrics of contemporary sequencing platforms, providing a basis for informed experimental design.

Table 1: Core Technology Specifications of Major Sequencing Platforms

| Technology / Platform | Read Length | Key Chemistry | Typical Workflow | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | 50-600 bp [22] | Sequencing-by-Synthesis (SBS) | Short-read; ensemble-based | Very high raw accuracy, high throughput, low cost per base [22] |

| PacBio HiFi | 15,000-20,000+ bp [25] | Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) with Circular Consensus Sequencing (CCS) | Long-read; single-molecule | High accuracy (99.9%), long reads, uniform coverage, native methylation detection [25] |

| Oxford Nanopore (ONT) | 5,000-30,000+ bp (up to ~1 Mbp) [24] [23] | Nanopore-based current sensing | Long-read; single-molecule | Ultra-long reads, portability, real-time analysis, native methylation detection [24] |

| Element Biosciences | Short-read | Sequencing By Binding (SBB) | Short-read; ensemble-based | High accuracy (Q40+), unique chemistry [23] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics in Genome Assembly Applications

| Performance Metric | Short-Read (Illumina) | Long-Read (PacBio HiFi) | Long-Read (ONT) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per-Base Accuracy | >99.9% (Q30+) [23] | >99.9% (Q30+) [25] | Varies; raw read error rate is higher, but consensus accuracy can be high with sufficient coverage [24] [23] |

| Assembly Contiguity | Lower; fragmented in repetitive regions | Higher; more complete genomes [26] [25] | Highest potential due to ultra-long reads [24] |

| Variant Detection | Excellent for SNPs/small indels | Comprehensive for SNPs, indels, and SVs [25] | Comprehensive for SNPs, indels, and SVs; excels in real-time applications [24] |

| Phasing Ability | Limited, requires statistical methods | Excellent, inherent due to read length [25] | Excellent, inherent due to read length [24] |

| Repetitive Region Resolution | Poor | Excellent [25] | Excellent [24] |

Experimental Protocol: A Comparison of Short- and Long-Read Sequencing for Microbial Genomics

This protocol outlines a robust methodology for empirically comparing the performance of short- and long-read sequencing technologies in genome assembly and variant calling, based on a recent study of phytopathogenic Agrobacterium strains [26] [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| High-Quality DNA Extraction Kit | To extract high molecular weight (HMW) genomic DNA for long-read sequencing. Integrity must be verified via pulse-field gel electrophoresis or Fragment Analyzer. |

| Illumina DNA Library Prep Kit | For preparing fragment libraries compatible with Illumina short-read sequencers (e.g., NovaSeq). |

| Oxford Nanopore Ligation Sequencing Kit | For preparing DNA libraries for Nanopore sequencing on platforms like GridION or PromethION. |

| PacBio SMRTbell Prep Kit | For preparing circularized DNA templates for PacBio HiFi sequencing on Sequel IIe or Revio systems. |

| Bioinformatic Pipelines | Specialized software for data analysis (e.g., Canu, Flye, Hifiasm for assembly; NGSEP, NECAT for variant calling) [26] [15]. |

Detailed Workflow

The end-to-end experimental and computational workflow for a comparative study is depicted below.

Sample Preparation and Sequencing

- DNA Extraction: Isolate high molecular weight (HMW) genomic DNA from the target microbial strains (e.g., Agrobacterium spp.). Assess DNA quality and quantity using spectrophotometry and fragment analysis.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Short-Read Data: Prepare sequencing libraries from the HMW DNA using an Illumina-compatible library preparation kit, following the manufacturer's protocol. Sequence the libraries on an Illumina platform (e.g., NovaSeq) to achieve sufficient coverage (>50x).

- Long-Read Data: Using the same HMW DNA extract, prepare a separate library for Oxford Nanopore sequencing using the Ligation Sequencing Kit. Sequence on a PromethION or GridION flow cell to achieve a target coverage (>50x) [26].

Genome Assembly and Analysis

- De Novo Assembly:

- Short-Read Assembly: Assemble the Illumina reads using a dedicated short-read assembler or a standard pipeline.

- Long-Read Assembly: Assemble the Nanopore reads using a long-read specific assembler (e.g., Canu, Flye, or NECAT) [15].

- Assembly Quality Assessment: Compare the resulting assemblies using metrics such as contiguity (contig N50), completeness (BUSCO scores), and base-level accuracy by aligning to a reference genome if available [28]. Long-read assemblies are expected to be significantly more contiguous and complete [26].

- Variant Calling and Genotyping:

- Call variants against a reference genome using pipelines designed for short reads and pipelines designed for long reads.

- Optimized Hybrid Approach: Computationally fragment the long reads into shorter pseudo-reads (e.g., 300 bp). Use these fragmented reads as input for the standard short-read variant calling pipeline. This approach has been shown to improve genotyping accuracy from long-read data [26] [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Algorithms and Metrics

The evolution of sequencing technologies has been paralleled by advancements in bioinformatics tools for data analysis and quality assessment.

Table 4: Essential Bioinformatics Tools and Quality Metrics

| Category | Tool / Metric | Function / Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Assembly Algorithms | SHARCGS [29] | Early algorithm for accurate de novo assembly of very short reads (25-40 bp). |

| Canu, Flye, FALCON [15] | Overlap-Layout-Consensus (OLC) based assemblers designed for long, error-prone reads. | |

| Hifiasm, HiCanu [15] | Modern assemblers optimized for highly accurate PacBio HiFi reads. | |

| NGSEP [15] | Incorporates new algorithms for efficient and accurate assembly from long reads. | |

| Quality Metrics | N50 / L50 [28] | Standard contiguity metrics; higher N50 indicates a more contiguous assembly. |

| BUSCO [28] | Assesses assembly completeness based on the presence of universal single-copy orthologs. | |

| Proportional N50 [30] | A proposed new metric that normalizes N50 by average chromosome size, allowing better cross-assembly comparisons. | |

| LAI (LTR Assembly Index) [28] | Evaluates the continuity of repetitive regions, particularly retrotransposons. | |

| QV (Quality Value) [28] | A quantitative measure of base-level accuracy in an assembly. |

The empirical data generated from the outlined protocol will clearly demonstrate the strengths and limitations of each technology. Findings will likely align with recent literature, confirming that long-read sequencing produces more complete genome assemblies by effectively spanning repetitive regions [26]. However, a critical finding is that for downstream applications like variant calling, the analysis pipeline is as important as the data itself. The optimized approach of computationally fragmenting long reads for use with established short-read pipelines can yield the highest genotyping accuracy, combining the assembly benefits of long reads with the analytical robustness of short-read tools [26] [27].

For research focused on generating a high-quality reference genome or resolving complex structural variation, long-read sequencing, particularly PacBio HiFi, is the unequivocal choice. For large-scale population studies or clinical epidemiology where accuracy and cost-efficiency are paramount, a hybrid approach utilizing both technologies—or an optimized long-read-only pipeline—may represent the most effective strategy. The decision matrix for sequencing technology is therefore not a matter of simple superiority, but one of strategic alignment with the specific biological questions and analytical end-goals of the research project.

The reconstruction of complete genomic sequences from fragmented sequencing reads remains a foundational challenge in genomics. The quality of a genome assembly directly influences downstream biological interpretations, making rigorous quality assessment indispensable for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. While sequencing technologies have advanced from short-read to long-read platforms, the fundamental metrics for evaluating assembly contiguity have evolved rather than become obsolete. This application note focuses on three critical dimensions of assembly assessment: contiguity metrics (N50/L50), coverage calculation, and their practical application within a genome assembly algorithm comparison framework. These metrics provide an objective foundation for selecting the most appropriate assembly for specific research applications, from gene discovery to variant identification.

The evaluation of a genome assembly is a multi-faceted process, where contiguity, completeness, and correctness must be balanced [28]. Contiguity measures how fragmented the assembly is, completeness assesses what proportion of the genome is represented, and correctness evaluates the accuracy of the sequence reconstruction. This document provides detailed methodologies for calculating, interpreting, and contextualizing key contiguity and coverage metrics, enabling informed decision-making in genomic research and its applications in biomedicine.

Core Metrics for Assessing Assembly Contiguity

Definition and Calculation of N50 and L50

N50 is a weighted median statistic that describes the contiguity of a genome assembly. It is defined as the length of the shortest contig or scaffold such that 50% of the entire assembly is contained in contigs or scaffolds of at least this length [31]. To calculate the N50, one must first order all contigs from longest to shortest, then cumulatively sum their lengths until the cumulative total reaches or exceeds 50% of the total assembly size. The length of the contig at which this cumulative sum is achieved is the N50 value [32].

L50 is the companion statistic to N50, representing the count of the smallest number of contigs whose combined length represents at least 50% of the total assembly size [31]. From the same ordered list of contigs used for the N50 calculation, the L50 is simply the count of contigs included in the cumulative sum that reaches the 50% threshold [33]. For example, if the three longest contigs in an assembly combine to represent more than half of the total assembly length, then the L50 count is 3 [31].

Table 1: Key Contiguity Metrics and Their Definitions

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| N50 | The length of the shortest contig at 50% of the total assembly length. | Higher values indicate more contiguous assemblies. |

| L50 | The smallest number of contigs whose length sum comprises 50% of the genome size. | Lower values indicate more contiguous assemblies. |

| N90 | The length for which all contigs of that length or longer contain at least 90% of the sum of all contig lengths. | A more stringent measure of contiguity. |

| NG50 | The length of the shortest contig at 50% of the known or estimated genome size rather than the assembly size. | Allows comparison between assemblies of different sizes. |

Related Metrics: N90, NG50, and Beyond

While N50 and L50 are the most widely reported contiguity statistics, several related metrics provide additional insights:

- N90: This is a more stringent contiguity metric calculated similarly to N50 but using a 90% threshold instead of 50%. The N90 statistic will always be less than or equal to the N50 statistic, as it represents the contig length at which 90% of the assembly is covered [31].

- NG50: This variant of N50 addresses a critical limitation when comparing assemblies of different sizes. The NG50 statistic uses 50% of the known or estimated genome size as the threshold rather than 50% of the actual assembly size [31]. This prevents inflated N50 values from assemblies with excess duplication from appearing superior. For a given assembly, the NG50 will not be more than the N50 statistic when the assembly size does not exceed the genome size.

- D50: This statistic represents the lowest value d for which the sum of the lengths of the largest d contigs is at least 50% of the sum of all lengths [31].

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for calculating these core contiguity metrics:

Critical Limitations and Contextual Interpretation

When N50 Can Be Misleading

Despite its widespread use, N50 has significant limitations that researchers must consider:

Sensitivity to Assembly Size: The standard N50 is calculated based on the assembly size rather than the genome size. This means that an assembly with significant duplication can appear to have a higher N50 than a more complete but less duplicated assembly [31]. The NG50 metric should be used to address this limitation when the genome size is known or can be reliably estimated.

Exclusion of Short Contigs: Researchers can artificially inflate N50 by removing shorter contigs from the assembly, as the statistic is calculated only on the remaining sequences [31]. This practice improves the apparent contiguity while potentially discarding biologically relevant sequences.

Lack of Completeness and Correctness Information: A high N50 value does not guarantee that the assembly is complete or correct [34] [28]. An assembly can have excellent contiguity while missing significant portions of the genome or containing misassembled regions. One study noted that "the correctness of an assembly also varies widely and is not well correlated with statistics on contiguity" [34].

The Importance of Multi-Dimensional Assessment

Given these limitations, N50 and L50 should never be used as standalone metrics for assembly quality. A comprehensive assessment should integrate multiple quality dimensions [28]:

- Completeness: Evaluated using tools like BUSCO (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs) to assess the presence of expected conserved genes [35], or k-mer based approaches like Merqury that compare k-mer content between sequencing reads and the assembly [28].

- Correctness: Assessed through reference-based comparisons when available, or through internal consistency checks such as k-mer validation or the LTR Assembly Index (LAI) for evaluating repetitive region assembly [35] [28].

- Contiguity: The domain of N50/L50 metrics, but ideally supplemented with the "contig-to-chromosome ratio" (CC ratio), which measures how close the assembly is to being chromosome-complete [28].

Genome Coverage: Calculation and Implications

Defining and Calculating Coverage

Coverage (also called depth or sequencing depth) describes the average number of reads aligning to each position in the genome [36]. It is a critical parameter in sequencing project design and quality assessment, as it directly influences the ability to detect variants and assemble complete sequences. The formula for calculating coverage is:

Coverage = Total amount of sequencing data / Genome size

For example, if sequencing a human genome (approximately 3.1 Gb) generates 100 Gb of data, the average coverage would be 100 / 3.1 ≈ 32.3x [36]. Conversely, to determine how much data is needed to achieve a specific coverage target:

Total data required = Genome size × Desired coverage

To achieve 20x coverage of a mouse genome (approximately 2.7 Gb), one would need 2.7 × 20 = 54 Gb of data [36].

Coverage in Assembly Context

Adequate coverage is essential for generating complete and accurate genome assemblies. Different sequencing technologies and assembly goals require different coverage depths. Long-read technologies (Oxford Nanopore and PacBio) often require lower coverage than short-read technologies for comparable assembly contiguity, thanks to their ability to span repetitive regions. However, higher coverage is typically needed for accurate variant calling or for assembling through particularly challenging regions.

Integrated Protocols for Metric Calculation and Assembly Evaluation

Protocol 1: Calculating N50 and L50 from an Assembly

This protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for calculating contiguity metrics from a draft genome assembly.

Research Reagent Solutions Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Assembly Metric Calculation

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| FASTA file | Standard format containing assembly sequences | Input data containing contigs/scaffolds to be evaluated |

| Custom Perl/Python script | Calculate N50, L50, and related statistics | Flexible metric calculation without specialized software |

| QUAST | Quality Assessment Tool for Genome Assemblies | Comprehensive assembly evaluation with multiple metrics |

| Bioinformatics workspace | Computational environment with adequate memory | Execution of analysis scripts and tools |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Input Preparation: Obtain the assembly file in FASTA format. Each contig or scaffold should be represented as a separate sequence entry with a header line beginning with '>' followed by sequence data.

Length Calculation: Compute the length of each contig/scaffold in the assembly. This can be done by summing the number of nucleotide characters (A, C, G, T, N) for each sequence, excluding header lines and any non-sequence characters.

Sorting: Sort all contigs/scaffolds by their lengths in descending order (from longest to shortest).

Total Assembly Size: Calculate the sum of the lengths of all contigs/scaffolds to determine the total assembly size.

Threshold Determination: Calculate 50% of the total assembly size (total size × 0.5).

Cumulative Summation: Iterate through the sorted list of contigs, maintaining a running sum of their lengths. Continue until the cumulative sum reaches or exceeds the 50% threshold calculated in the previous step.

Metric Extraction:

- The N50 is the length of the contig at which the cumulative sum first meets or exceeds the threshold.

- The L50 is the number of contigs included in the cumulative sum at this point.

Validation: For verification, ensure that the sum of all contigs longer than the N50 is approximately equal to the sum of all contigs shorter than the N50 [31].

Code Example Snippet (Conceptual):

Adapted from implementation example in [37]

Protocol 2: Comprehensive Assembly Quality Assessment Framework

This protocol outlines a holistic approach to genome assembly evaluation, integrating contiguity metrics with completeness and correctness assessments.

Workflow Diagram:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Generate Multiple Assemblies: Using the same sequencing dataset, generate assemblies using multiple algorithms (e.g., Canu, Flye, NECAT, WTDBG2) with optimized parameters for each [35] [34].

Calculate Contiguity Metrics: For each assembly, calculate N50, L50, NG50, and N90 statistics following Protocol 1. Record these values in a comparative table.

Assess Completeness:

Evaluate Correctness:

- Calculate the LTR Assembly Index (LAI) to assess the assembly quality of repetitive regions [35] [28].

- If a reference genome is available, perform whole-genome alignment to identify potential misassemblies and large-scale errors.

- Use k-mer-based validation tools to identify base-level errors and inconsistencies [28].

Integrate Results and Select Optimal Assembly: Create a comprehensive metrics table that includes all quantitative assessments. Rather than selecting based on any single metric, choose the assembly that best balances contiguity, completeness, and correctness for the specific research objectives.

N50, L50, and genome coverage are fundamental metrics for evaluating genome assemblies, but they represent just one dimension of assembly quality. These contiguity statistics provide valuable insights into the fragmentation level of an assembly, with higher N50 and lower L50 values generally indicating more contiguous reconstructions. However, as demonstrated throughout this application note, these metrics must be interpreted in the broader context of completeness and correctness assessments to form a complete picture of assembly quality.

For researchers comparing genome assembly algorithms, we recommend a comprehensive evaluation framework that includes not just N50 and L50, but also NG50 (for size-normalized comparison), BUSCO scores (for completeness), LAI (for repeat region quality), and k-mer based validation. This multi-dimensional approach ensures selection of assemblies that are not just contiguous but also complete and accurate, providing a reliable foundation for downstream biological discovery and application in drug development pipelines. As sequencing technologies continue to evolve toward truly complete telomere-to-telomere assemblies, the precise role of these metrics may shift, but the fundamental principles of rigorous assembly evaluation will remain essential.

Choosing Your Tool: A Practical Guide to Assembly Algorithms and Pipelines

Within the paradigm of Overlap-Layout-Consensus (OLC)", assemblers play a crucial role in reconstructing genomes from long-read sequencing data generated by platforms such as Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT). These assemblers are designed to handle the inherent challenges of long reads, including high error rates and complex repetitive regions, to produce contiguous and accurate genome assemblies [38] [39]. This application note provides a detailed overview of three prominent OLC-based assemblers—Canu, Falcon, and Flye—framed within a broader research project comparing genome assembly algorithms. We summarize quantitative performance data from benchmark studies, outline detailed experimental protocols for their application, and visualize their workflows to guide researchers and scientists in selecting and implementing the appropriate tool for their genomic projects.

The OLC paradigm involves three fundamental steps: first, computing pairwise overlaps between all reads; second, determining a layout of reads based on overlap information to form contigs; and finally, calculating a consensus sequence to correct base errors in the contigs [38] [40]. While Canu and Falcon are traditional OLC assemblers, Flye employs a repeat graph, a variant of the OLC approach, to improve assembly continuity and accuracy [39] [41].

Benchmarking studies on prokaryotic and eukaryotic datasets reveal critical differences in the performance of these tools. The following table summarizes key quantitative metrics for Canu, Falcon, and Flye based on real and simulated read sets:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Canu, Falcon, and Flye

| Assembler | Algorithm Type | Contiguity (Prokaryotic Contig Count) | Runtime (E. coli, in hours) | RAM Usage (Human Genome, in GB) | Strengths and Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canu | OLC with read correction | 3–5 contigs [39] | ~6.0 [39] | ~40-50 (prokaryotic) [38] | High accuracy but fragmented assemblies; longest runtimes [38] [39] |

| Falcon | Hierarchical OLC (for diploids) | Information Missing | Information Missing | Information Missing | Designed for haplotype-aware assembly; used in hybrid pipelines [42] [43] |

| Flye | A-Bruijn Graph (OLC variant) | Often 1 contig [39] | ~0.5 [39] | 329–502 (human) [44] | Best balance of accuracy and contiguity; sensitive to input read quality [38] [39] |

Performance is influenced by sequencing depth and read length. For complex genomes, assemblies with ≤30x depth and shorter read lengths are highly fragmented, with genic regions showing degradation at 20x depth [42]. A depth of at least 30x is recommended for satisfactory gene-space assembly in complex genomes like maize [42].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Genome Assembly with Flye

Application: Producing high-quality, contiguous assemblies for prokaryotic or small eukaryotic genomes. Principle: Flye uses a repeat graph to resolve genomic repeats iteratively, which allows it to generate complete, circular assemblies from error-prone long reads [38] [39].

Materials:

- Sequencing Data: ONT or PacBio long-read data in FASTQ format.

- Computational Resources: For a human genome, expect to use ~500 GB RAM and up to a day of compute time [44].

- Software: Flye (v2.8 or newer) installed.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Ensure reads are in a single FASTQ file. Preprocessing (e.g., filtering and trimming) is recommended for optimal results [39].

- Execute Assembly: Run Flye from the command line with core parameters:

--nano-hq: Specifies high-quality ONT reads. Use--pacbio-hqfor PacBio HiFi or--pacbio-rawfor CLR reads.--genome-size: Estimated genome size (e.g.,5mfor 5 Mbp).--out-dir: Directory for output files.--threads: Number of CPU threads to use.

- Output: The primary assembly contigs will be in

<output_dir>/assembly.fasta.

Protocol 2: Genome Assembly with Canu

Application: Ideal for projects requiring high sequence identity and accurate consensus, especially on bacterial genomes and plasmids. Principle: Canu integrates read correction, trimming, and assembly into a single OLC-based pipeline, making it robust for high-noise data [38] [39].

Materials:

- Sequencing Data: ONT or PacBio long-read data in FASTQ format.

- Computational Resources: This is the most computationally intensive tool; for an E. coli genome, it can require ~6 hours and significant RAM [39].

- Software: Canu (v2.1 or newer) installed.

Procedure:

- Data Preparation: Canu performs internal correction, so raw reads can be used as input.

- Execute Assembly: Run Canu with parameters adjusted for genome size and technology:

-pand-d: Define the project name and output directory.genomeSize: Crucial for coverage calculations.useGrid=false: Disables grid execution for a single-machine run.-nanoporeor-pacbio: Specifies the read type.

- Output: The final corrected assembly is in

<output_dir>/<project_name>.contigs.fasta.

Protocol 3: Hybrid Assembly with Falcon and Canu

Application: Assembling complex, repeat-rich eukaryotic genomes (e.g., maize) by leveraging the strengths of multiple tools. Principle: This hybrid protocol uses Falcon for initial error correction of reads, followed by Canu for assembly, balancing accuracy and contiguity for large genomes [42].

Materials:

- Sequencing Data: High-depth (e.g., 50-75x) PacBio long-read data.

- Computational Resources: This pipeline is extremely resource-intensive and was accelerated via cloud computing for the 2.3 Gb maize genome [42].

- Software: Falcon and Canu installed.

Procedure:

- Error Correction with Falcon: Use Falcon to error-correct the raw subreads.

- Assembly with Canu: Assemble the error-corrected reads using Canu.

- Optional Scaffolding: Use an optical mapping technology (e.g., Bionano) to scaffold the resulting contigs into chromosome-scale molecules [42].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the core steps and key differences in the workflows of Canu, Falcon, and Flye.

Figure 1: Comparative workflows of Canu, Flye, and Falcon. Canu incorporates read correction and trimming internally. Flye builds and simplifies a repeat graph for assembly. In the hybrid pipeline, Falcon acts as an error-correction preprocessor for another assembler like Canu.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Oxford NanoporeMinION Mk1B | Portable device for generating long-read sequencing data. | Sequencing genomic DNA from bacterial isolates or complex eukaryotes [39]. |

| PacBio Sequel | Platform for generating long-read data (CLR or HiFi). | Producing high-depth reads for assembling complex plant genomes [42]. |

| DNeasy Blood &Tissue Kit | Extraction of high-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA. | Preparing DNA from E. coli DH5α for ONT library construction [39]. |

| SQK-LSK109Ligation Kit | Prepares genomic DNA libraries for sequencing on ONT flow cells. | Standard library preparation for ONT sequencing [39]. |

| Bionano OpticalMapping | Provides long-range scaffolding information for contigs. | Scaffolding a fragmented maize assembly to chromosome-scale [42]. |

| Canu/Flye/Falcon | OLC-based software for de novo genome assembly. | Reconstructing a complete bacterial genome into a single, circular contig [38] [39]. |

De Bruijn graph (DBG) assemblers have become fundamental tools for reconstructing genomes from short-read sequencing data, effectively addressing challenges posed by high-throughput technologies. These assemblers break reads down into smaller substrings (k-mers) and assemble them via graph traversal, balancing the trade-offs between resolving repeats and handling sequencing errors. Within this domain, SPAdes, ABySS, and Velvet represent significant algorithmic advancements, each contributing distinct strategies for managing computational complexity and assembly quality. This application note details their operational protocols, performance characteristics, and practical implementation within a broader research context focused on genome assembly algorithm comparison.

Core Principles and Strategic Differences

Velvet, one of the pioneering DBG assemblers, introduced a compact graph representation using k-mers to manage high-coverage, very short read (25-50 bp) datasets [45]. Its algorithm involves graph construction, error correction through topological features, and simplification to produce contigs. In contrast, ABySS was designed to overcome memory constraints by implementing a distributed de Bruijn graph, enabling parallel computation across multiple compute nodes and making large genome assemblies feasible [46]. SPAdes employs an iterative multi-k-mer approach, constructing graphs for a range of k-values to leverage the advantages of both short and long k-mers—shorter k-mers help resolve low-coverage regions, while longer k-mers effectively break repeats [47].

Benchmarking and Performance Metrics

Independent evaluations consistently highlight the superior performance of these tools under specific conditions. A 2022 benchmarking study on viral next-generation sequencing (NGS) data, including SARS-CoV-2, concluded that SPAdes, IDBA-UD, and ABySS performed consistently well, demonstrating robust genome fraction recovery and assembly contiguity [48]. Another study evaluating assemblers on microbial genomes reported that while SPAdes and ABySS produced quality assemblies, Velvet showed relatively lower performance in terms of contiguity (NGA50) compared to other modern assemblers [49].

Table 1: Summary of Key Features and Performance of SPAdes, ABySS, and Velvet

| Assembler | Primary Strategy | Key Strength | Noted Limitation | Optimal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPAdes | Iterative multi-k-mer assembly [47] | High contiguity, especially at low coverages [50] [48] | Computationally intensive [13] | Bacterial genomes, single-cell sequencing [49] |

| ABySS | Distributed de Bruijn graph [46] | Scalability for large genomes (e.g., human) [46] | Lower N50 compared to some peers [50] | Large, complex eukaryotic genomes [46] |

| Velvet | De Bruijn graph with error removal [45] | Effective for short reads and error correction [45] | Lower NGA50 in microbial benchmarks [49] | Small to medium-sized genomes, proof-of-concept |

Performance is also influenced by read coverage. An analysis of seven popular assemblers found that SPAdes consistently achieved the highest average N50 values at low read coverages (below 16x), while Velvet, SOAPdenovo2, and ABySS formed a group with comparatively lower N50 values across different coverage depths [50].

Table 2: Comparative Assembly Performance on Simulated Microbial Genomes (100x Coverage) [49]

| Assembler | NGA50 (kb)* | Assembly Errors | Key Performance Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| MaSuRCA | 297 | Highest | Produced the largest scaffolds but with the most errors. |

| Ray | - | Low | Balanced performance with good contiguity and low errors. |

| ABySS | - | - | Ranked highly in contiguity after MaSuRCA and Ray. |

| SPAdes | - | - | Mid-range performance in contiguity. |

| Velvet | Lowest | - | Generated the shortest scaffolds among the tested assemblers. |

Note: Exact NGA50 values for all assemblers were not provided in the source; the table reflects relative rankings. [49]

Experimental Protocols

General Workflow for De Novo Genome Assembly

The following protocol outlines the standard steps for de novo genome assembly using DBG-based tools, with specific considerations for SPAdes, ABySS, and Velvet.

Step 1: Data Quality Control and Preprocessing

- Input: Raw paired-end short-read sequences (FASTQ format).

- Procedure: Use tools like FastQC for quality assessment. Perform adapter trimming and quality filtering with Trimmomatic or Cutadapt. For a more accurate assembly, error correction tools specific to your sequencing technology can be applied to the reads.

- Critical Parameter: Ensure high-quality reads remain after trimming, as base call errors significantly complicate the de Bruijn graph.

Step 2: Selection of the k-mer Spectrum

- SPAdes: Automatically selects and employs a range of k-mer values. The user can also specify a custom range (e.g.,

-k 21,33,55). - ABySS & Velvet: Require a single k-mer value per run. Benchmarking multiple k-mers is essential (e.g., k=32, 64, 96 for Velvet [50]). A smaller k-mer (e.g., 21-31) helps in low-coverage regions, while a larger k-mer (e.g., 64-127) resolves repeats.

Step 3: Genome Assembly Execution

- SPAdes Command (Single-Cell):

The

--scflag is used for single-cell data, which has uneven coverage. For multi-cell data, omit this flag and use--carefulfor mismatch correction [50].

Velvet Commands:

The

velvethcommand builds the dataset for a k-mer of 31.velvetgconstructs the graph and produces contigs. Parameters like-cov_cutoffand-exp_covcan be set to 'auto' or defined based on read characteristics [45] [50].ABySS Command:

For a parallelized cluster run, environment variables like

NP(number of processes) must be configured [46].

Step 4: Post-Assembly and Validation

- Output: The primary outputs are contigs and scaffolds (FASTA format).

- Procedure: Assess assembly quality using metrics like N50, NG50, and L50 with QUAST [50]. QUAST can align contigs to a reference genome (if available) to report misassemblies, indels, and mismatches. Benchmarking with Unaligned Sequence (BUSCO) can assess genomic completeness.

Workflow Visualization

Title: General workflow for de novo assembly with SPAdes, ABySS, and Velvet.

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Assembly and Validation

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| FastQC | Quality Control | Visualizes read quality metrics (per-base sequence quality, adapter content). | Used pre-assembly to identify problematic datasets. |

| Trimmomatic | Preprocessing | Removes adapters and trims low-quality bases from reads. | Critical for reducing graph complexity and errors. |

| QUAST | Quality Assessment | Evaluates contiguity (N50) and correctness vs. a reference [50] [49]. | The standard for comparative assembly benchmarking. |

| ART Illumina | Read Simulation | Generates synthetic Illumina reads from a reference genome [49]. | Enables controlled assembler performance testing. |

| SAMtools | Data Handling | Processes and extracts reads from alignment files (BAM) [50]. | Used in preparatory steps for real data analysis. |

SPAdes, ABySS, and Velvet are foundational tools that have shaped the landscape of short-read genome assembly. SPAdes excels in automated, multi-k-mer assemblies for smaller genomes, ABySS provides the distributed computing power necessary for large eukaryotic genomes, and Velvet offers a historically important and robust algorithm for standard projects. The choice among them depends on the specific biological question, genome size, and computational resources. Furthermore, employing multiple assemblers and reconciliation tools [51] is a recommended strategy in clinical and public health settings to ensure robustness, as no single algorithm is flawless. Continuous benchmarking and validation, as part of a comprehensive assembly protocol, remain paramount for generating high-quality genomic sequences.

De novo genome assembly is a foundational step in genomic research, enabling the reconstruction of an organism's complete DNA sequence from fragmented sequencing reads. The advent of long-read sequencing (LRS) technologies from Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) has revolutionized genome assembly by spanning repetitive regions and complex structural variations that previously confounded traditional short-read sequencing (SRS) approaches [52]. However, each sequencing paradigm presents distinct advantages and limitations. While SRS offers high base-level accuracy at low cost, it produces fragmented assemblies due to limited read lengths. Conversely, LRS generates long reads that enhance contiguity but suffers from higher error rates and increased costs [52].

Hybrid assembly strategies have emerged as a powerful solution that integrates data from both short and long-read technologies, leveraging their complementary strengths to produce more accurate and complete genome reconstructions [53] [52]. This approach utilizes high-throughput, high-accuracy short reads to correct sequencing errors inherent in long-read data, followed by de novo assembly using these error-corrected, highly contiguous long reads [52]. The resulting assemblies demonstrate significantly improved continuity and accuracy, particularly in repeat-rich regions, while optimizing resource utilization compared to long-read-only approaches requiring high coverage [52].

The utility of hybrid sequencing extends across diverse genomic applications, including eukaryotic genome assembly, bacterial genomics, viral community analysis, metagenomic studies of complex microbial communities, and clinical applications in personalized medicine [52]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of hybrid assembly methodologies, quantitative performance assessments, detailed experimental protocols, and implementation frameworks to guide researchers in deploying these strategies effectively.

Comparative Performance of Sequencing and Assembly Approaches

Fundamental Technological Comparisons

Table 1: Comparison of Sequencing Technology Characteristics

| Feature | Short-Read Sequencing | Long-Read Sequencing | Hybrid Sequencing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Length | 50–300 bp | 5,000–100,000+ bp | Combines both read types |

| Accuracy (per read) | High (≥99.9%) | Moderate (85–98% raw) | High (≥99.9%; after correction with SRS) |

| Primary Platforms | Illumina, BGI | Oxford Nanopore, PacBio | Illumina + ONT/PacBio |

| Cost per Base | Low | Higher | Moderate |

| Throughput | Very high | Moderate to high | Depends on balance of platforms |

| Best Applications | Variant calling, RNA-seq, Population studies | Structural variation, isoform detection, de novo assembly | Comprehensive genome analysis, complex genomic regions |

| Primary Limitations | Limited context for repeats or SVs; fragmented assemblies | Higher error rates; more complex preparation; higher cost | More complex analysis; higher logistical requirements |

Assembly Performance Metrics