How Machine Learning is Revolutionizing Biomarker Discovery: From Multi-Omics Integration to Clinical Validation

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative impact of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) on biomarker discovery for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

How Machine Learning is Revolutionizing Biomarker Discovery: From Multi-Omics Integration to Clinical Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative impact of machine learning (ML) and artificial intelligence (AI) on biomarker discovery for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational shift from single-analyte approaches to ML-driven analysis of complex multi-omics datasets, detailing key methodologies from feature selection to deep learning. The scope extends to practical applications across oncology, neurology, and infectious diseases, while critically addressing central challenges including data heterogeneity, model interpretability, and overfitting. Furthermore, the article outlines rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses of ML techniques essential for translating computational biomarkers into clinically validated tools for precision medicine, synthesizing current evidence and future directions in the field.

The New Paradigm: How AI is Redefining Biomarker Discovery

{LIMITATIONS OF SINGLE-FEATURE BIOMARKERS} The reliance on a single biological feature as a definitive classifier for disease state or treatment response introduces several critical vulnerabilities into the research and development pipeline. These limitations not only hinder clinical utility but also contribute to the high attrition rate of biomarker candidates [1].

Table 1: Key Limitations of Single-Feature Biomarker Approaches

| Limitation | Underlying Cause | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Biological Reflection | Inability to capture disease heterogeneity, compensatory pathways, and complex tumor microenvironments [2]. | Suboptimal patient stratification, failure to predict treatment efficacy accurately, and inability to anticipate resistance mechanisms. |

| Limited Analytical Performance | Dependence on a single analytical signal, making the result vulnerable to pre-analytical and analytical variability [3]. | Poor reproducibility and reliability across different laboratories and sample types, leading to inconsistent clinical decisions. |

| Susceptibility to Confounding | The single feature may be a correlative rather than a causative factor, or influenced by unrelated biological processes [4] [5]. | High false-positive and false-negative rates, as seen with C-reactive protein in cardiovascular disease where levels are affected by obesity and other conditions [4]. |

| Restricted Clinical Utility | Provides a binary (positive/negative) result that often fails to inform on prognosis, disease subtype, or optimal therapy sequencing [6]. | Limited value in guiding complex treatment decisions in adaptive trial designs and personalized medicine strategies [2]. |

{QUANTITATIVE EVIDENCE AND CASE STUDIES} Empirical data and historical case studies underscore the practical challenges outlined in Table 1. The high failure rate of biomarker development is a testament to these issues; most discovered biomarkers never achieve clinical adoption [1]. A systematic analysis of biomarker success identified that robust clinical validity and utility are the most significant predictors of translation, areas where single-feature approaches are inherently weak [1]. The following case studies illustrate these points.

Table 2: Case Studies Highlighting Single-Feature Biomarker Challenges

| Biomarker & Disease Context | Documented Challenge | Impact on Clinical Application |

|---|---|---|

| HER2 in Breast Cancer [3] | Ongoing debate regarding optimal assay methodology (IHC vs. FISH) and efficacy of targeted therapy in patients with low HER2 expression [3]. | Continuous refinement of testing guidelines and potential denial of effective therapy to a subset of patients. |

| EGFR in Colorectal & Lung Cancer [3] | EGFR protein expression by IHC fails to reliably predict response to EGFR inhibitors; other features (KRAS mutations, EGFR amplification) are critical. | Initial patient selection based on a single feature (EGFR IHC) was suboptimal, requiring subsequent incorporation of additional biomarkers. |

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) in Cardiovascular Disease [4] | Disputed causal relationship; levels are confounded by factors like obesity and physical activity, complicating interpretation [4]. | Significant confusion regarding its role as a risk predictor versus a consequence of disease, limiting its standalone utility. |

{EXPERIMENTAL PROTOCOLS FOR EVALUATING BIOMARKER LIMITATIONS} To systematically evaluate the performance and limitations of a candidate single-feature biomarker, the following protocols provide a standardized methodological framework.

Protocol 1: Assessing Biomarker Specificity in a Heterogeneous Population

- Objective: To determine the false positive rate of a candidate biomarker by testing its presence in non-disease control populations and in tissues/cells with confounding conditions.

- Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: See Table 4 for essential materials.

- Sample Sets: Banked tissue sections, serum/plasma samples, or cell line lysates from (a) confirmed disease-positive patients, (b) healthy controls, and (c) patients with pathologically similar or confounding conditions (e.g., other cancer types, inflammatory diseases).

- Methodology:

- Sample Processing: Execute standardized protocols for nucleic acid extraction (for genomic biomarkers) or protein extraction (for proteomic biomarkers) from all sample sets.

- Assay Performance: Analyze all samples using the designated platform for the candidate biomarker (e.g., qPCR for DNA/RNA, immunohistochemistry for protein).

- Data Analysis: Calculate sensitivity, specificity, and positive predictive value. A high false positive rate in control groups (c) indicates low specificity and high susceptibility to confounding.

Protocol 2: Evaluating Dynamic Range and Quantitative Correlation

- Objective: To establish whether the biomarker's level quantitatively correlates with disease severity or drug response, moving beyond a binary positive/negative readout.

- Materials:

- Research Reagent Solutions: Refer to Table 4.

- Sample Sets: A longitudinal series of samples from the same patient (pre-treatment, on-treatment, progression) or a cohort with well-defined, graded disease severity.

- Methodology:

- Quantitative Assay: Employ a quantitative or semi-quantitative assay (e.g., quantitative RT-PCR, ELISA, RNA-Seq, targeted mass spectrometry).

- Standard Curve Generation: For analytical methods like ELISA, include a standard curve with known concentrations of the analyte to ensure accurate quantification.

- Correlation Analysis: Statistically correlate the quantitative level of the biomarker with clinical endpoints (e.g., tumor size, survival time, pathological grade). A weak correlation suggests limited prognostic or predictive power.

{VISUALIZING THE CONCEPTUAL SHIFT} The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz, illustrate the core conceptual limitations of the single-feature approach and the logical pathway for its evaluation.

Diagram 1: Single-feature versus multi-feature biomarker models.

Diagram 2: Tumor heterogeneity confounding single-feature assays.

Diagram 3: Logical workflow for evaluating single-feature biomarker limitations.

{THE SCIENTIST'S TOOLKIT: RESEARCH REAGENT SOLUTIONS} Successful execution of the experimental protocols requires standardized, high-quality reagents and platforms. The following table details essential materials for biomarker evaluation studies.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Biomarker Evaluation

| Reagent / Platform | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Formalin-Fixed, Paraffin-Embedded (FFPE) Tissue Sections | Preserves tissue morphology and biomolecules for retrospective histological and molecular analysis. | Immunohistochemistry (IHC) for protein biomarker localization and semi-quantification [3]. |

| Validated Antibodies (Monoclonal/Polyclonal) | Highly specific binding to target antigen for detection and quantification. | HercepTest (anti-HER2 antibody) for IHC-based stratification for trastuzumab therapy [3]. |

| Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) Probes | Labeled nucleic acid sequences for detecting specific gene loci or chromosomal abnormalities. | PathVysion HER2 DNA Probe Kit for determining HER2 gene amplification status [3]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Panels | High-throughput, parallel sequencing of multiple genes or entire genomes/transcriptomes. | Identifying co-occurring mutations (e.g., KRAS, NRAS) in colorectal cancer to predict resistance to EGFR therapy [3] [7]. |

| Liquid Biopsy Collection Tubes | Stabilizes cell-free DNA and other analytes in blood samples for non-invasive biomarker analysis. | Isolation of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) for dynamic monitoring of tumor burden and resistance mutations [7]. |

| Digital Biomarker Discovery Pipelines (e.g., DBDP) | Open-source computational toolkits for standardized processing of digital health data (e.g., from wearables) [8]. | Extracting features like heart rate variability from ECG data as a digital biomarker for cardiovascular risk [8]. |

{CONCLUSION} The evidence demonstrates that traditional single-feature biomarker approaches are fundamentally constrained in their ability to navigate the complex biological networks underlying human disease. The protocols and visualizations provided herein offer a systematic pathway for researchers to empirically validate these limitations within their specific contexts. The consistent failure of such narrow approaches to achieve clinical translation [1] underscores the necessity for a paradigm shift. The future of biomarker discovery lies in integrated multi-omics data and machine learning models capable of identifying complex, multi-analyte signatures that more accurately reflect disease biology and power the next generation of personalized medicine [4] [2] [9].

{ARTICLE CONTENT END}

Biomarkers are defined characteristics measured as indicators of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or responses to an exposure or intervention [10]. In precision medicine, biomarkers facilitate accurate diagnosis, risk stratification, disease monitoring, and personalized treatment decisions by tailoring therapies to individual genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors [11]. The joint FDA-NIH Biomarkers, EndpointS, and other Tools (BEST) resource establishes standardized definitions to ensure clarity across research and clinical practice [10]. This document delineates the core definitions and applications of diagnostic, prognostic, and predictive biomarkers, contextualized within modern machine learning-driven discovery frameworks.

Core Biomarker Definitions and Applications

Biomarkers are categorized based on their specific clinical applications. Understanding the distinctions between these categories is essential for appropriate use in both research and clinical decision-making [10] [12].

Table 1: Core Biomarker Types, Definitions, and Applications

| Biomarker Type | Definition | Primary Application | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic | Detects or confirms the presence of a disease or condition of interest [10]. | Disease identification and classification [10]. | PSA for prostate cancer screening; Troponin for acute myocardial infarction [10] [12]. |

| Prognostic | Provides information on the overall disease outcome, including the risk of recurrence or progression, regardless of therapy [13] [14]. | Informing disease management strategies and patient counseling on likely disease course [14] [15]. | Oncotype DX and MammaPrint assays for estimating breast cancer recurrence risk [14] [12]. |

| Predictive | Identifies individuals who are more likely to experience a favorable or unfavorable effect from a specific therapeutic intervention [13] [14]. | Guiding treatment selection to optimize efficacy and avoid ineffective therapies [14] [12]. | HER2 overexpression predicting response to trastuzumab in breast cancer; EGFR mutations predicting response to gefitinib in lung cancer [13] [14] [12]. |

A critical conceptual distinction is that a prognostic biomarker informs on the aggressiveness of a disease, while a predictive biomarker informs on the effectiveness of a specific therapy [12]. A single biomarker can serve both prognostic and predictive roles, though evidence must be developed for each context of use [10] [14].

Experimental Protocols for Biomarker Validation

Analytical Validation

Before clinical utility can be assessed, a biomarker assay must undergo rigorous analytical validation to prove technical robustness [12]. This process is the focus of Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) regulations and involves evaluating several key parameters [12].

Table 2: Key Parameters for Biomarker Analytical Validation

| Parameter | Definition | Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | The degree to which the measured value reflects the true value [12]. | Compare results from the new assay against a gold-standard reference method using a panel of known positive and negative samples. Calculate percent agreement or correlation coefficients [12]. |

| Precision | The closeness of agreement between independent measurement results obtained under stipulated conditions [12]. | Run replicate measurements of the same sample across multiple days, by different operators, and using different instrument lots. Report results as coefficients of variation (CV) [12]. |

| Analytical Sensitivity | The lowest amount of the biomarker that can be reliably distinguished from zero [12]. | Perform serial dilutions of a sample with a known concentration of the biomarker. The limit of detection (LoD) is the lowest concentration consistently detected in ≥95% of replicates [12]. |

Clinical Validation and Statistical Assessment

Clinical validation provides proof that the biomarker is fit for its intended clinical purpose [12]. This requires testing the biomarker in a patient population entirely distinct from the discovery cohort to avoid overfitting [13] [12].

Key Statistical Considerations and Protocols:

- Study Power and Design: The intended use and target population must be defined early. For prognostic biomarkers, retrospective studies with prospectively collected biospecimens from a cohort representing the target population are often used. Predictive biomarkers, however, must be identified through secondary analyses of randomized clinical trials, testing for a statistically significant interaction between the treatment and the biomarker in a statistical model [13].

- Minimizing Bias: Implement randomization during specimen analysis to control for batch effects and non-biological experimental variations. Blinding should be used to keep laboratory personnel unaware of clinical outcomes during biomarker data generation [13].

- Performance Metrics: The analytical plan must be pre-specified prior to data analysis. Performance is quantitatively assessed using metrics tailored to the biomarker's purpose [13]:

- Sensitivity: Proportion of true cases correctly identified.

- Specificity: Proportion of true controls correctly identified.

- Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve and Area Under the Curve (AUC): Plots sensitivity vs. (1-specificity) across all thresholds, with AUC providing a measure of overall discriminative ability [13].

- Positive/Negative Predictive Values (PPV/NPV): Proportion of test-positive/negative patients who truly have/do not have the disease or outcome, dependent on disease prevalence [13].

Machine Learning in Biomarker Discovery

Traditional single-feature biomarker discovery faces challenges with reproducibility and capturing disease complexity. Machine learning (ML) addresses these by integrating large, complex multi-omics datasets to identify reliable biomarkers [11].

ML Applications by Biomarker Type

Table 3: Machine Learning Applications for Biomarker Discovery

| Biomarker Type | ML Application | Exemplary Study |

|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic | Classifying disease status based on molecular profiles [11] [4]. | Using transcriptomic data from rheumatoid arthritis patients, an ML pipeline (including PCA and t-SNE for visualization) demonstrated clear separation between patients and controls [4]. |

| Prognostic | Forecasting disease progression and patient stratification [11] [15]. | In multiple myeloma, ML models integrate genetic, transcriptomic, and imaging data to identify high-risk patients, moving beyond traditional staging systems like R-ISS [15]. |

| Predictive | Estimating response to specific therapies [11] [16]. | A study predicting Large-Artery Atherosclerosis (LAA) integrated clinical factors and metabolite profiles. A logistic regression model achieved an AUC of 0.92, identifying predictive features like smoking status and lipid metabolites [16]. |

Standard ML Workflow Protocol

A typical ML workflow for biomarker discovery involves:

- Data Preprocessing: Handling missing data (e.g., mean imputation), label encoding, and participant grouping. Data is typically split into training/validation (e.g., 80%) and external testing (e.g., 20%) sets [16].

- Exploratory Data Analysis and Feature Selection: Using unsupervised learning techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) to visualize data structure, identify outliers, and understand group dynamics [4]. Recursive feature elimination is then used to identify the most informative biomarkers and reduce overfitting [16].

- Model Training and Validation: Training multiple supervised learning models (e.g., Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines, Random Forests, XGBoost) on the training set using tenfold cross-validation. Model performance is evaluated on the held-out test set using metrics like AUC [16].

- Interpretation and Validation: Using explainable AI (XAI) techniques to interpret model predictions and identify features driving the classification. Biomarkers identified computationally must subsequently undergo rigorous wet-lab validation to ensure clinical reliability [11] [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Biomarker Discovery

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Absolute IDQ p180 Kit | A targeted metabolomics kit that quantifies 194 endogenous metabolites from 5 compound classes [16]. | Used in the LAA study for plasma metabolite profiling to identify biomarkers linked to aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis and lipid metabolism [16]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | High-throughput technology for comprehensive genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic profiling [13] [17]. | Identifies mutations, gene rearrangements, and differential gene expression as candidate biomarkers in oncology and other diseases [13] [17]. |

| Liquid Biopsy Assays | Minimally invasive analysis of circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), circulating tumor cells (CTCs), and other blood-based biomarkers [13] [17]. | Used for cancer diagnosis, monitoring therapeutic response, and detecting minimal residual disease via ctDNA analysis [13] [17]. |

| Waters Acquity Xevo TQ-S | Tandem mass spectrometry instrument for highly sensitive and specific quantification of small molecules [16]. | Coupled with the Biocrates kit for precise measurement of metabolite concentrations in biomarker discovery studies [16]. |

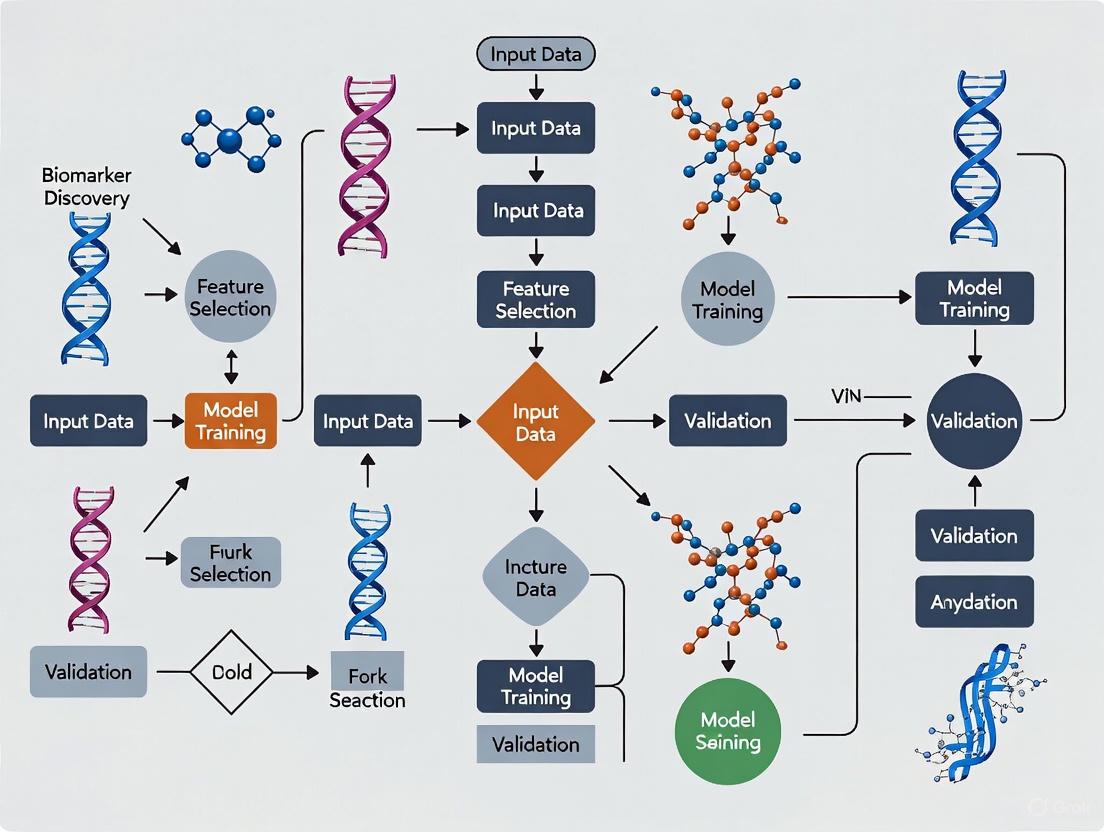

Workflow Visualization

Biomarker Development Pipeline

The journey from discovery to clinical application is long and requires multiple, rigorous stages [12] [17].

ML-Driven Discovery Workflow

Machine learning reshapes the initial discovery and validation phases, enabling integration of complex, high-dimensional data [11] [4] [16].

The Role of Machine Learning in Integrating Multi-Omics Data (Genomics, Proteomics, Metabolomics)

The complexity of biological systems necessitates moving beyond single-layer analyses to a more holistic approach. Multi-omics integrates data from various molecular levels—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, and metabolomics—to provide a comprehensive view of biological processes and disease mechanisms [18] [19]. This approach is revolutionizing biomedical research by enabling the identification of comprehensive biomarker signatures and providing insights into disease etiology and potential treatment targets that would remain elusive with single-omics studies [19].

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a critical enabler for multi-omics integration, addressing significant challenges inherent in these complex datasets. Traditional statistical models often struggle with the high dimensionality, heterogeneity, and noise characteristic of multi-omics data [20]. ML algorithms, particularly deep learning models, can effectively handle these challenges by identifying complex, non-linear patterns across different biological layers, thereby revealing hidden connections and improving disease prediction capabilities [9] [20]. This integration is especially valuable in precision medicine, where it supports disease diagnosis, prognosis, personalized treatments, and therapeutic monitoring [9].

Machine Learning Approaches for Multi-Omics Data Integration

Categories of Integration Strategies

Machine learning approaches for multi-omics integration can be categorized based on how and when the data fusion occurs during the analytical process. The selection of an appropriate integration strategy depends on the specific research objectives, data characteristics, and computational resources available [21].

Table 1: Machine Learning Integration Strategies for Multi-Omics Data

| Integration Strategy | Description | Advantages | Limitations | Common Algorithms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Concatenates all omics datasets into a single matrix before analysis [21]. | Simple to implement; captures cross-omics correlations immediately [21]. | High dimensionality and noise; ignores data structure differences [21]. | Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forests [22]. |

| Intermediate Integration | Learns joint representations from multiple omics datasets simultaneously [23] [21]. | Balances data specificity and integration; effectively captures inter-omics interactions [21]. | Requires robust pre-processing; complex model implementation [21]. | Multiple Kernel Learning, MOFA, Deep Learning Autoencoders [20]. |

| Late Integration | Analyzes each omics dataset separately and combines the results or predictions at the final stage [21]. | Avoids challenges of direct data fusion; utilizes domain-specific models [21]. | Does not directly capture inter-omics interactions [21]. | Ensemble Methods, Voting Classifiers [22]. |

| Network-Based Integration | Utilizes biological networks to contextualize and integrate multi-omics data [24]. | Incorporates prior biological knowledge; provides biological context for findings [24]. | Dependent on quality and completeness of network databases [24]. | Graph Neural Networks, Network Propagation [24]. |

Deep Learning Architectures for Multi-Omics

Deep learning has become increasingly prominent in multi-omics research due to its ability to model complex, non-linear relationships in high-dimensional data [20]. These models can be broadly divided into two categories:

Non-generative models include architectures such as feedforward neural networks (FFNs), graph convolutional networks (GCNs), and autoencoders, which are designed to extract features and perform classification directly from the input data [20]. For instance, convolutional neural networks (CNNs) have been applied to multi-omics classification tasks, while recurrent neural networks (RNNs) like CNN-BiLSTM can model sequential dependencies in omics data [25].

Generative models, including variational autoencoders (VAEs), generative adversarial networks (GANs), and generative pretrained transformers (GPTs), focus on creating adaptable representations that can be shared across multiple modalities [20]. These approaches are particularly valuable for handling missing data and dimensionality challenges, often outperforming traditional methods [20].

Computational Framework and Workflow

Implementing a successful machine learning pipeline for multi-omics data requires a systematic approach that addresses the unique characteristics of biological datasets. The following workflow outlines the key stages in this process.

Data Preprocessing and Quality Control

The initial preprocessing stage is critical for ensuring data quality and analytical robustness. Key steps include:

Normalization and Batch Effect Correction: Technical variations across different sequencing platforms, laboratory conditions, or sample processing batches can introduce significant artifacts. Methods such as Harmony analysis are employed to mitigate batch effects and ensure that biological signals rather than technical variations drive the analytical results [26]. Normalization techniques must be appropriately selected for each omics layer to account for differences in data distribution and scale [21].

Missing Value Imputation: Omics datasets frequently contain missing values due to various technical and biological reasons. specialized imputation processes are required to infer these missing values before statistical analyses can be applied [21]. Techniques range from simple mean/median imputation to more sophisticated K-nearest neighbors (KNN) or matrix factorization methods, with the choice dependent on the missing data mechanism and proportion.

Dimensionality Reduction and Feature Selection: The "high-dimension low sample size" (HDLSS) problem, where variables significantly outnumber samples, can cause ML algorithms to overfit, reducing their generalizability [21]. Feature selection methods (e.g., variance filtering, LASSO) and dimensionality reduction techniques (e.g., PCA, UMAP) help address this challenge by focusing on the most biologically relevant features [26].

Machine Learning Model Training and Validation

Following data preprocessing, the ML model development phase involves:

Model Selection and Training: The choice of algorithm depends on the research objective, data characteristics, and sample size. For example, in a schizophrenia study comparing 17 machine learning models, LightGBMXT achieved superior performance for multi-omics classification with an AUC of 0.9727, outperforming other models including CNN-BiLSTM [25]. Ensemble methods often demonstrate strong performance in multi-omics applications.

Validation and Generalizability Assessment: Rigorous validation is essential to ensure model robustness. This includes internal validation through techniques such as k-fold cross-validation and external validation on independent datasets [9]. Performance metrics should be selected based on the specific application—AUC-ROC for classification tasks, C-index for survival analysis, or mean squared error for continuous outcomes.

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Studies

Protocol 1: Multi-Omics Biomarker Discovery for Disease Classification

This protocol outlines the procedure for identifying integrative biomarkers for disease classification, adapted from a study on schizophrenia [25].

Sample Preparation and Data Generation:

- Cohort Selection: Recruit a well-characterized cohort of case and control participants (e.g., 104 individuals total) with matched clinical phenotypes [25].

- Sample Collection: Collect peripheral blood samples in EDTA tubes and isolate plasma through centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- Multi-Omics Data Generation:

- Proteomics: Process plasma samples using liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with isobaric labeling (TMT or iTRAQ) for protein quantification. Include post-translational modification (PTM) analysis through enrichment protocols.

- Metabolomics: Perform untargeted metabolomic profiling using LC-MS in both positive and negative ionization modes.

Data Preprocessing:

- Proteomics Data: Normalize protein abundances using quantile normalization, impute missing values with KNN imputation, and log2-transform the data.

- Metabolomics Data: Perform peak alignment, retention time correction, and compound identification using reference standards. Normalize to total ion count.

- Data Integration: Merge proteomics, PTM, and metabolomics datasets using shared sample identifiers, ensuring proper alignment of samples across platforms.

Machine Learning Analysis:

- Feature Pre-selection: Apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction (e.g., FDR < 0.05) and retain features with significant differential abundance between cases and controls.

- Model Training: Implement multiple machine learning algorithms (e.g., LightGBMXT, Random Forest, SVM, CNN-BiLSTM) using a standardized framework. Utilize automated machine learning (AutoML) to optimize hyperparameters.

- Model Validation: Perform 100 iterations of 5-fold cross-validation, evaluating performance using AUC-ROC, precision, recall, and F1-score.

- Biomarker Interpretation: Apply feature importance analysis (e.g., SHAP values) to identify top discriminative features. Conduct functional enrichment analysis on prioritized biomarkers using databases like GO, KEGG, and Reactome.

Protocol 2: Network-Based Multi-Omics Integration for Drug Target Identification

This protocol utilizes network biology approaches to identify novel drug targets from multi-omics data, based on methodologies from network-based multi-omics integration studies [24].

Data Collection and Processing:

- Multi-Omics Data Acquisition: Collect genomic (DNA sequencing), transcriptomic (RNA-seq), and proteomic (LC-MS/MS) data from patient samples and public repositories (e.g., TCGA, CPTAC) [24] [26].

- Molecular Network Construction:

- Download protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks from curated databases (e.g., STRING, BioGRID).

- Construct gene co-expression networks using WGCNA on transcriptomics data.

- Integrate pathway information from KEGG, Reactome, and WikiPathways.

Network-Based Integration:

- Multi-Layer Network Construction: Create an integrated network with nodes representing biomolecules (genes, proteins) and edges representing interactions from different omics layers and databases.

- Network Propagation: Apply network propagation algorithms (e.g., Random Walk with Restart) to diffuse molecular alterations (e.g., mutations, expression changes) through the integrated network.

- Module Detection: Identify densely connected network modules exhibiting significant alterations across multiple omics layers using community detection algorithms (e.g., Louvain method).

Target Prioritization and Validation:

- Target Scoring: Develop a multi-parametric scoring system incorporating network centrality, cross-omics alteration frequency, functional essentiality, and druggability predictions.

- Experimental Validation: Select top-ranked targets for functional validation using CRISPR knockdown, organoid models, or high-content screening assays.

- Therapeutic Response Prediction: Integrate drug-target interaction networks with multi-omics profiles to predict drug response and identify potential repurposing opportunities [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of multi-omics studies with machine learning integration requires both wet-lab reagents and computational resources.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Multi-Omics Studies

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | DNA polymerases, dNTPs, oligonucleotide primers [19] | Genomics, epigenomics, and transcriptomics analyses | Fundamental components for PCR-based amplification |

| Reverse transcriptases, cDNA synthesis kits [19] | Transcriptomics: conversion of RNA to cDNA | Enable gene expression analysis via RT-PCR and qPCR | |

| Methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes [19] | Epigenomics: DNA methylation studies | Detect and analyze reversible DNA modifications | |

| Mass spectrometry kits and reagents [19] | Proteomics and metabolomics profiling | Identify and quantify proteins and metabolites | |

| Computational Tools | Python/R ML libraries (scikit-learn, TensorFlow) [9] | Implementation of machine learning models | Provide algorithms for classification, regression, clustering |

| Multi-omics integration tools (MOFA, mixOmics) [23] | Integration of multiple omics datasets | Specialized methods for combining different data types | |

| Biological network analysis (Cytoscape, NetworkX) [24] | Construction and analysis of molecular networks | Visualize and analyze complex biological interactions | |

| Single-cell analysis tools (Seurat, Scanpy) [26] | Analysis of single-cell RNA sequencing data | Process and interpret single-cell resolution data |

Case Study: Schizophrenia Biomarker Discovery Through Multi-Omics Integration

A recent study demonstrated the power of AI-driven multi-omics integration for identifying peripheral biomarkers for schizophrenia risk stratification [25]. The research utilized an open-access dataset comprising plasma proteomics, post-translational modifications (PTMs), and metabolomics data from 104 individuals.

Experimental Workflow and Key Findings: The researchers applied a comprehensive machine learning framework with 17 different algorithms, finding that multi-omics integration significantly enhanced classification performance compared to single-omics approaches. The best-performing model (LightGBMXT) achieved an AUC of 0.9727, outperforming models using proteomics data alone [25].

Interpretable feature prioritization identified specific molecular events as key discriminators, including:

- Carbamylation at immunoglobulin-constant region sites IGKCK20 and IGHG1K8

- Oxidation of coagulation factor F10 at residue M8 [25]

Functional analyses revealed significantly enriched pathways including complement activation, platelet signaling, and gut microbiota-associated metabolism. Protein interaction networks further implicated coagulation factors (F2, F10, PLG) and complement regulators (CFI, C9) as central molecular hubs [25].

Biological Implications and Clinical Relevance: The study revealed an immune-thrombotic dysregulation as a critical component of schizophrenia pathology, with PTMs of immune proteins serving as quantifiable disease indicators [25]. This integrative approach delineated a robust computational strategy for incorporating multi-omics data into psychiatric research, providing biomarker candidates for future diagnostic and therapeutic applications.

Visualization of Molecular Interactions and Pathways

Understanding the complex interactions between identified biomarkers and their functional pathways is essential for biological interpretation. The following diagram illustrates a representative immune-coagulation network identified in the schizophrenia multi-omics study [25].

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite significant advancements, several challenges remain in the application of machine learning to multi-omics integration. Key limitations include:

Data Quality and Heterogeneity: The inherent heterogeneity of omics data comprising varied datasets with different distributions and types presents significant integration challenges [21]. Additionally, issues of missing data and batch effects require specialized preprocessing approaches that can impact downstream analyses [20] [21].

Model Interpretability and Biological Validation: Many advanced machine learning models, particularly deep learning approaches, function as "black boxes" with limited interpretability [9]. The development of explainable AI (XAI) methods is crucial for translating computational findings into biologically meaningful insights [9] [23]. Furthermore, computational predictions require experimental validation through techniques such as knockdown experiments, organoid models, or clinical correlation studies [22].

Regulatory and Ethical Considerations: The clinical implementation of AI-driven multi-omics approaches requires careful attention to regulatory requirements and ethical considerations, particularly regarding patient data privacy and algorithmic bias [9]. Establishing standards for trustworthy AI in biomedical research is essential for clinical adoption [9].

Future developments in the field will likely focus on incorporating temporal and spatial dynamics through technologies such as single-cell sequencing and spatial transcriptomics [26], improving model interpretability through explainable AI techniques, and establishing standardized evaluation frameworks for comparing different integration methods [24]. As these technologies mature, machine learning-powered multi-omics integration will play an increasingly central role in precision medicine, biomarker discovery, and therapeutic development.

Performance Benchmarks of ML-Driven Biomarker Discovery

Table 1: Performance Metrics of ML Models for Biomarker Discovery Across Diseases

| Disease Area | ML Model(s) Used | Biomarker Type / Purpose | Key Performance Metrics | Reference / Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oncology | Random Forest, XGBoost | Predictive biomarkers for targeted cancer therapeutics | LOOCV Accuracy: 0.7 - 0.96 | [27] |

| Ovarian Cancer | Ensemble Methods (RF, XGBoost) | Diagnostic biomarkers (e.g., CA-125, HE4 panels) | AUC > 0.90; Accuracy up to 99.82% | [28] |

| Alzheimer's Disease (AD) | Random Forest | Digital plasma spectra for AD vs. Healthy Controls | AUC: 0.92, Sensitivity: 88.2%, Specificity: 84.1% | [29] |

| Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) | Random Forest | Digital plasma spectra for MCI vs. Healthy Controls | AUC: 0.89, Sensitivity: 88.8%, Specificity: 86.4% | [29] |

| Infectious Diseases | Explainable AI, Ensemble Learning | Surveillance, diagnosis, and prognosis | High accuracy in prediction (Specific metrics vary by study) | [30] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Predictive Biomarker Discovery in Oncology

This protocol outlines the process for using machine learning to identify protein-based predictive biomarkers for targeted cancer therapies, based on the MarkerPredict framework [27].

1. Data Acquisition and Network Construction

- Signaling Networks: Obtain protein-protein interaction data from dedicated signaling networks. The MarkerPredict study used the Human Cancer Signaling Network (CSN), SIGNOR, and ReactomeFI [27].

- Protein Disorder Data: Compile intrinsic disorder predictions for proteins using databases like DisProt and prediction tools such as IUPred and AlphaFold (using pLDDT scores) [27].

- Biomarker Annotation: Gather known biomarker data from text-mining databases like CIViCmine to create labeled training data [27].

2. Training Set Construction

- Positive Controls: Create a set of protein pairs where one protein is a known predictive biomarker for a drug targeting the other protein in the pair [27].

- Negative Controls: Create a set of protein pairs where the neighbor protein is not listed as a predictive biomarker in the annotation database [27].

3. Feature Extraction For each target-neighbor protein pair, extract the following features for ML model training:

- Network Topological Features: Calculate properties related to the protein's position and role within the signaling network (e.g., motif characteristics, centrality measures) [27].

- Motif Participation: Identify if the protein pair participates in specific three-nodal network motifs (triangles), which indicate close regulatory connections [27].

- Protein Disorder: Integrate metrics on intrinsic protein disorder for the neighbor protein [27].

4. Machine Learning Model Training and Validation

- Algorithm Selection: Employ tree-based ensemble algorithms such as Random Forest and XGBoost, which offer a balance between performance and interpretability [27].

- Model Validation: Perform rigorous validation using Leave-One-Out-Cross-Validation (LOOCV) and k-fold cross-validation to assess model accuracy and prevent overfitting [27].

- Biomarker Probability Score (BPS): Define a normalized score that aggregates the results from multiple models to rank potential predictive biomarkers [27].

5. Downstream Validation

- Experimental Validation: Prioritize high-ranking biomarker candidates for validation in wet-lab experiments using cell lines, organoids, or patient-derived samples [2] [27].

- Clinical Correlation: Investigate the correlation of candidate biomarkers with treatment response and patient outcomes in clinical datasets or trials [27].

Protocol for Digital Biomarker Discovery in Neurodegenerative Diseases

This protocol details a methodology for developing low-cost, machine learning-based digital biomarkers from blood plasma for Alzheimer's Disease (AD) and mild cognitive impairment (MCI), adapted from a 2025 validation study [29].

1. Participant Recruitment and Cohort Definition

- Recruit well-characterized participants across multiple cohorts: Amyloid-beta positive AD patients, patients with MCI, patients with other neurodegenerative diseases (e.g., DLB, FTD, PSP) for differential diagnosis, and healthy controls (HCs) [29].

- Conduct neuropsychological assessments (e.g., MMSE, MoCA) and confirm AD pathology via CSF analysis or PiB-PET imaging where feasible [29].

2. Sample Collection and Spectral Data Acquisition

- Collect plasma samples from all participants using standardized, minimally invasive venipuncture procedures [29].

- Spectral Analysis: Analyze plasma samples using Attenuated Total Reflectance-Fourier Transform Infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy to generate distinct spectral fingerprints. This technique examines functional groups and molecular conformations associated with proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [29].

- (Optional) Measure traditional plasma biomarkers (e.g., p-tau217, GFAP, Aβ42) using technologies like Single Molecule Immune Detection (SMID) for subsequent correlation analysis [29].

3. Data Preprocessing and Feature Selection

- Preprocess spectral data to correct for baseline effects and normalize across samples [29].

- Digital Biomarker Selection: Use a Random Forest classifier in conjunction with feature selection procedures to identify the most informative spectral features (wavenumbers or peaks) that serve as digital biomarkers for distinguishing patient groups [29].

4. Machine Learning Model Development

- Train the Random Forest model using the selected digital biomarker panel to perform binary classifications (e.g., AD vs. HC, AD vs. DLB) [29].

- Validate model performance on independent validation cohorts to ensure generalizability. Report standard metrics including Area Under the Curve (AUC), sensitivity, and specificity [29].

5. Model Interpretation and Biological Correlation

- Analyze the correlation between the identified spectral digital biomarkers and concentrations of established pathological plasma biomarkers (e.g., p-tau217, GFAP) to provide a biological interpretation for the ML model's decisions [29].

Protocol for Biomarker Discovery in Infectious Disease Management

This protocol provides a general workflow for applying ML to identify biomarkers for infectious disease surveillance, diagnosis, and prognosis, synthesized from a 2025 scoping review [30].

1. Problem Definition and Data Source Identification

- Define the specific clinical objective: surveillance (outbreak prediction), diagnosis (pathogen or disease identification), or prognosis (predicting disease severity or outcome) [30].

- Identify and gather relevant multimodal data sources. These can include:

- Clinical Data: Electronic Health Records (EHRs), vital signs, laboratory results [30].

- Omics Data: Genomic, transcriptomic, or proteomic data from host or pathogen [30].

- Epidemiological Data: Public health reports, web surveillance data, phylogenetic trees [30].

- Other Data: Medical imaging (e.g., chest X-rays) or biomarker test results [30].

2. Data Preprocessing and Feature Engineering

- Clean the data by handling missing values and normalizing or standardizing features.

- Perform feature engineering to create informative inputs for the models. For heterogeneous data, dimensionality reduction techniques (e.g., PCA) may be necessary [30].

3. Model Selection and Training

- Select appropriate ML algorithms based on the data type and clinical question. The review suggests Explainable AI (XAI) and Ensemble Learning models are broadly applicable and achieve high accuracy [30].

- Model Candidates:

- Train the models on a dedicated training set, using techniques like cross-validation to tune hyperparameters [30].

4. Model Validation and Implementation

- Rigorous Validation: Test the final model on a held-out test set and, crucially, on independent external cohorts to assess generalizability and avoid biases present in the training data [30].

- Clinical Workflow Integration: Develop an actionable workflow for integrating the model into clinical practice to complement and augment clinical decision-making [30].

Workflow Visualization

Predictive Biomarker Discovery in Oncology

Digital Biomarker Workflow for Neurodegenerative Diseases

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for ML-Driven Biomarker Discovery

| Tool / Resource | Function / Application | Specific Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SomaScan Platform | High-throughput proteomic discovery; measures thousands of proteins simultaneously in biofluids. | Used by the Global Neurodegeneration Proteomics Consortium (GNPC) on ~35,000 samples [31]. |

| Olink & Mass Spectrometry | Complementary proteomic platforms for biomarker verification and validation. | Used by GNPC for cross-platform comparison and validation of SomaScan findings [31]. |

| ATR-FTIR Spectroscopy | Label-free biosensor generating digital spectral fingerprints from plasma/serum. | Identifies molecular-level changes for digital biomarker creation in neurodegenerative diseases [29]. |

| Spatial Biology Platforms | Enables in-situ analysis of biomarker distribution and cell interactions within tissue context. | Critical for characterizing the tumor microenvironment (TME) in oncology [2]. |

| Organoids & Humanized Models | Advanced disease models that recapitulate human biology for functional biomarker validation. | Used for screening functional biomarkers and studying therapy response in immunooncology [2]. |

| CIViCmine Database | Text-mined knowledgebase of clinical evidence for cancer biomarkers. | Provides curated data for training and validating ML models in oncology [27]. |

| DisProt / IUPred / AlphaFold | Databases and tools for analyzing intrinsic protein disorder, a feature for predictive biomarkers. | Used as features in ML models like MarkerPredict to identify cancer biomarkers [27]. |

| Cloud Data Environments | Secure, scalable platforms for collaborative analysis of large, harmonized datasets. | Alzheimer's Disease Data Initiative's AD Workbench used by GNPC to manage data access and analysis [31]. |

The field of biomarker discovery is undergoing a fundamental transformation, shifting from traditional single-analyte approaches toward integrative, data-intensive strategies powered by machine learning (ML). This evolution is critical for addressing the biological complexity underlying disease mechanisms, particularly for heterogeneous conditions like cancer, neurological disorders, and metabolic diseases. Where conventional methods often identified correlative biomarkers with limited clinical utility, modern ML approaches now enable researchers to uncover functional biomarkers—molecules and molecular signatures with direct roles in pathological processes—thus bridging the gap between correlation and causation.

The limitations of traditional biomarker discovery are becoming increasingly apparent. Methods focusing on single molecular features face significant challenges with reproducibility, high false-positive rates, and inadequate predictive accuracy due to the inherent biological heterogeneity of complex diseases [11]. These approaches often fail to capture the multifaceted biological networks underpinning disease mechanisms. In contrast, machine learning and deep learning methodologies represent a substantial shift by handling vast and complex biological datasets, known collectively as multi-omics data, which integrate genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, imaging, and clinical records [11]. This comprehensive profiling facilitates the identification of highly predictive biomarkers and provides unprecedented insights into functional disease mechanisms.

The application of these advanced computational techniques has expanded beyond conventional diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers to include functional biomarkers like biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs)—groups of genes encoding enzymatic machinery for producing specialized metabolites with therapeutic potential [11]. This represents a novel dimension in biomarker discovery, directly linking genomic capabilities to functional outcomes. This article explores the transformative role of machine learning in uncovering functional biomarkers, detailing experimental protocols, analytical frameworks, and their applications in precision medicine.

Machine Learning Approaches for Functional Biomarker Discovery

Methodological Frameworks and Algorithms

Machine learning applications in biomarker discovery encompass diverse methodologies tailored to different data structures and biological questions. Supervised learning approaches train predictive models on labeled datasets to classify disease status or predict clinical outcomes. Commonly used techniques include Support Vector Machines (SVM), which identify optimal hyperplanes for separating classes in high-dimensional omics data; Random Forests, ensemble models that aggregate multiple decision trees for robustness against noise; and gradient boosting algorithms (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM), which iteratively correct previous prediction errors for superior accuracy [11]. For feature selection, Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (LASSO) regression effectively identifies the most relevant molecular features from high-dimensional datasets [32].

In contrast, unsupervised learning explores unlabeled datasets to discover inherent structures or novel subgroupings without predefined outcomes. These methods are invaluable for endotyping—classifying diseases based on underlying biological mechanisms rather than purely clinical symptoms [11]. Techniques include clustering methods (k-means, hierarchical clustering) and dimensionality reduction approaches (principal component analysis).

Deep learning architectures represent a more advanced frontier, with convolutional neural networks (CNNs) excelling at spatial pattern recognition in imaging and histopathology data, and recurrent neural networks (RNNs) capturing temporal dynamics in longitudinal biomedical data [11] [32]. The emerging integration of large language models and transformers further enhances the ability to extract insights from complex clinical narratives and molecular sequences [11].

Table 1: Machine Learning Algorithms for Different Data Types in Biomarker Discovery

| Omics Data Type | ML Techniques | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Transcriptomics | Feature selection (e.g., LASSO); SVM; Random Forests | Identifying differential gene expression signatures; Disease classification |

| Proteomics | CNN; LASSO; SVM-RFE | Pattern recognition in protein arrays; Biomarker signature identification |

| Metagenomics | Random Forests; CNN; Feature selection | Identifying microbial signatures; Predicting functional traits like BGCs |

| Imaging Data | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN); Deep Learning | Extracting prognostic features from histopathology; Quantitative imaging biomarkers |

| Multi-omics Integration | Multi-layer perceptrons; Ensemble methods; Stacked generalization | Developing comprehensive biomarker panels; Disease endotyping |

Workflow for Identifying Functional Biomarkers

The discovery of functional biomarkers follows a structured computational and experimental workflow. The process begins with data acquisition and preprocessing from diverse sources, including public repositories like the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and in-house experimental data. For transcriptomic analyses, the "limma" R package is commonly employed to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) using criteria such as |logFold Change (logFC)| > 0.585 and adjusted p-value < 0.05 [32].

Following differential expression analysis, Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA) identifies gene modules associated with specific traits or diseases by constructing a biologically meaningful network through selection of an appropriate soft-threshold power (β) [33] [32]. This approach transforms adjacency matrices into topological overlap matrices (TOM) and identifies gene modules using hierarchical clustering and dynamic tree cutting. Key modules are selected based on correlations between module eigengenes and clinical traits.

Integration of multiple machine learning algorithms significantly enhances the robustness of biomarker identification. Studies often employ 101 unique combinations of 10 machine learning algorithms to identify the most significant interacting genes between related conditions [33]. For instance, the glmBoost+RF combination has demonstrated superior performance in identifying biomarkers linking diabetes and kidney stones [33]. Similarly, integration of LASSO, Random Forest, Boruta, and SVM-RFE has proven effective in heart failure biomarker discovery [32].

Functional validation of computational predictions involves protein-protein interaction (PPI) network construction using databases like STRING (with a composite score > 0.4 considered significant) and functional enrichment analysis using Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analyses via the "clusterProfiler" R package [32]. These analyses elucidate biological processes, molecular functions, and signaling pathways associated with candidate biomarkers.

Diagram 1: Computational Workflow for Functional Biomarker Discovery. The process integrates multiple data analysis steps from acquisition to experimental validation.

Application Notes: Case Studies in Functional Biomarker Discovery

Case Study 1: Bridging Diabetes and Nephrolithiasis Through Programmed Cell Death Pathways

Our first case study demonstrates the power of integrative bioinformatics and machine learning to uncover shared mechanisms between metabolic and urinary system disorders. Research has revealed an increased prevalence of kidney stones among diabetic patients, suggesting potential underlying mechanistic links [33]. To investigate these connections, researchers conducted bulk transcriptome differential analysis using sequencing data combined with the AS dataset (GSE231569) after eliminating batch effects [33].

The investigation focused on programmed cell death (PCD) pathways—including apoptosis, autophagy, pyroptosis, ferroptosis, and necroptosis—given their established roles in both diabetic complications and kidney stone formation. Differential expression analysis of PCD-related genes was conducted using the limma R package with criteria of adjusted P.Val < 0.05 and |logFC| > 0.25 [33]. This was complemented by WGCNA to identify gene modules associated with both conditions.

Through the application of 10 machine learning algorithms generating 101 unique combinations, three key biomarkers emerged as the most significant interacting genes: S100A4, ARPC1B, and CEBPD [33]. These genes were validated in both training and test datasets, demonstrating strong diagnostic potential. Western blot analysis confirmed protein-level expression changes, providing orthogonal validation of the computational findings.

The functional significance of these biomarkers was further elucidated through enrichment analyses, which revealed their involvement in immune regulation and inflammatory processes—key mechanisms linking diabetes and nephrolithiasis. This case exemplifies how machine learning can unravel complex relationships between seemingly distinct conditions, revealing shared pathological mechanisms and potential therapeutic targets.

Case Study 2: Deep Learning for Heart Failure Biomarkers and Therapeutic Targets

Our second case study explores a comprehensive approach to heart failure biomarker discovery, culminating in the development of a deep learning diagnostic model. The study utilized gene expression data from GEO datasets (GSE17800, GSE57338, and GSE29819), applying the ComBat algorithm to remove batch effects before analysis [32].

The research employed four machine learning methods—LASSO, Random Forest, Boruta, and SVM-RFE—to identify potential genes linked to heart failure [32]. This multi-algorithm approach identified four essential genes: ITIH5, ISLR, ASPN, and FNDC1. The study then developed a novel diagnostic model using a deep learning convolutional neural network (CNN), which demonstrated strong performance in validation against public datasets [32].

Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis of dataset GSE145154 provided unprecedented resolution, revealing stable up-regulation patterns of these genes across various cardiomyocyte types in HF patients [32]. This single-cell validation at the cellular level strengthened the case for the functional relevance of these biomarkers.

Beyond biomarker discovery, the study explored drug-protein interactions, revealing two potential therapeutic drugs targeting the identified key genes [32]. Molecular docking simulations provided feasible pathways for these interactions, demonstrating how functional biomarker discovery can directly inform therapeutic development. This end-to-end pipeline—from computational biomarker identification to therapeutic candidate prediction—showcases the transformative potential of machine learning in cardiovascular precision medicine.

Table 2: Key Biomarkers Identified Through ML Approaches in Recent Studies

| Disease Context | Identified Biomarkers | ML Methods Used | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diabetes & Nephrolithiasis | S100A4, ARPC1B, CEBPD | 10 algorithms with 101 combinations; glmBoost+RF | Role in programmed cell death pathways linking metabolic and urinary diseases |

| Heart Failure | ITIH5, ISLR, ASPN, FNDC1 | LASSO, Random Forest, Boruta, SVM-RFE | Extracellular matrix organization; cardiac remodeling |

| Psychiatric Disorders | Resting-state Functional Connectivity patterns | Ensemble sparse classifiers | Altered brain network connectivity in MDD, SCZ, and ASD |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Transcriptomic Biomarker Discovery with Integrated Machine Learning

Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition

- Tissue Collection: Obtain tissue samples (e.g., renal papilla, cardiac tissue) from both disease models and controls. For animal studies, ensure compliance with institutional animal care guidelines (e.g., NIH guidelines) [33].

- RNA Extraction: Use TRIzol reagent for total RNA extraction. Quantity RNA using NanoDrop 2000, ensuring 260/280 ratios between 1.8-2.0 [33].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Perform reverse transcription using kits such as ToloScript All-in-one RT EasyMix. Conduct RNA sequencing using appropriate platforms (e.g., Illumina) with minimum depth of 30 million reads per sample [33].

- Public Data Sourcing: Download complementary datasets from GEO database (e.g., GSE231569, GSE73680) for validation cohorts [33].

Computational Analysis

- Data Preprocessing: Normalize data using preprocessCore R package. Remove batch effects using ComBat algorithm when integrating multiple datasets [32].

- Differential Expression Analysis: Use limma R package with cutoff criteria of adjusted P.Val < 0.05 and |logFC| > 0.25-0.585 [33] [32]. Generate volcano plots and heatmaps using "pheatmap" package.

- Weighted Gene Co-expression Network Analysis (WGCNA):

- Select top 50% of genes with greatest variance for network construction.

- Determine soft-threshold power (β) based on scale-free topology criterion.

- Construct topological overlap matrix (TOM) and identify gene modules using dynamic tree cutting.

- Calculate gene significance (GS) and module membership (MM) for trait associations [33] [32].

- Machine Learning Integration: Apply multiple ML algorithms (LASSO, Random Forest, SVM-RFE, Boruta) with 10-fold cross-validation. Intersect results from different methods to identify robust biomarker candidates [32].

Functional Validation

- Protein-Protein Interaction Networks: Construct PPI networks using STRING database (confidence score > 0.4) and visualize with Cytoscape [33] [32].

- Functional Enrichment: Perform GO and KEGG pathway analyses using "clusterProfiler" R package. Set statistical significance threshold at p < 0.05 [33] [32].

- Transcription Factor Network Analysis: Predict upstream regulators using RegNetwork database and construct TF-gene interaction networks [33].

Protocol 2: Spatial Biomarker Validation Using Advanced Imaging Technologies

Sample Preparation and Multiplex Imaging

- Tissue Sectioning: Prepare fresh-frozen or FFPE tissue sections at 4-5μm thickness using a cryostat or microtome.

- Multiplex Immunohistochemistry/Optical Coherence Tomography:

- Perform antigen retrieval using appropriate buffers (e.g., citrate buffer for FFPE tissues).

- Implement sequential staining with antibody panels including 10-40 markers.

- Use tyramide signal amplification (TSA) for signal enhancement with careful antibody stripping between rounds.

- For OCT, capture cross-sectional retinal images with micron-level resolution [34].

Image Analysis and Biomarker Quantification

- Image Preprocessing: Apply flat-field correction, background subtraction, and compensation for spectral overlap.

- Cell Segmentation: Use machine learning-based segmentation (e.g., CellProfiler, Ilastik) to identify individual cells and subcellular compartments.

- Spatial Analysis: Quantify biomarker expression patterns relative to tissue structures and cellular neighborhoods. Calculate cell-to-cell distances and interaction frequencies [2].

- Biomarker Validation: Correlate spatial expression patterns with clinical outcomes using appropriate statistical models.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Functional Biomarker Discovery

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| TRIzol Reagent | RNA isolation from tissues and cells | Preserves RNA integrity for transcriptomic studies [33] |

| RIPA Lysis Buffer | Protein extraction from tissues | Western blot validation of candidate biomarkers [33] |

| Primary Antibodies | Target protein detection | Validation of ARPC1B, S100A4, CEBPD and other biomarkers [33] |

| Seurat R Package | Single-cell RNA sequencing analysis | Cell type identification and differential expression [33] |

| STRING Database | Protein-protein interaction network analysis | Understanding functional relationships between biomarker candidates [33] [32] |

| Omni LH 96 Homogenizer | Automated sample homogenization | Standardized sample preparation for multi-omics studies [7] |

| Optical Coherence Tomography | Non-invasive retinal imaging | Measuring RNFL and GCIPL thickness as structural biomarkers [34] |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The integration of machine learning with multi-omics data represents a paradigm shift in biomarker discovery, enabling the transition from correlative to functional biomarkers. However, several challenges remain in the clinical implementation of these approaches. Data quality issues, including limited sample sizes, noise, batch effects, and biological heterogeneity, can severely impact model performance, leading to overfitting and reduced generalizability [11]. The interpretability of ML models remains a significant hurdle, as many advanced algorithms function as "black boxes," making it difficult to elucidate specific prediction mechanisms [11].

Future advancements will likely focus on several key areas. First, the development of explainable AI (XAI) methods will be crucial for clinical adoption, where transparency and trust in predictive models are essential [11]. Second, rigorous external validation using independent cohorts and experimental methods must become standard practice to ensure reproducibility and clinical reliability [11]. Third, the integration of temporal dynamics through longitudinal data collection and analysis will enhance our understanding of disease progression and biomarker evolution.

The ethical and regulatory considerations surrounding ML-derived biomarkers also warrant careful attention. Biomarkers used for patient stratification, therapeutic decision-making, or disease prognosis must comply with rigorous standards set by regulatory bodies such as the FDA [11]. The dynamic nature of ML-driven biomarker discovery, where models continuously evolve with new data, presents particular challenges for regulatory oversight and demands adaptive yet strict validation frameworks.

Emerging technologies like spatial biology and liquid biopsy are further expanding the frontiers of biomarker discovery [2] [7]. Spatial techniques enable researchers to understand biomarker organization within tissue architecture, providing critical context for functional interpretation [2]. Liquid biopsy approaches offer non-invasive methods for biomarker detection and monitoring, potentially revolutionizing patient follow-up and treatment response assessment [7].

As these technologies mature and computational methods advance, functional biomarker discovery will increasingly enable disease endotyping—classifying subtypes based on shared molecular mechanisms rather than solely clinical symptoms [11]. This mechanistic approach supports more precise patient stratification, therapy selection, and understanding of disease heterogeneity, ultimately fulfilling the promise of precision medicine across diverse therapeutic areas.

Diagram 2: Evolution from Correlative to Functional Biomarkers. The field is transitioning through integration of multi-omics data and machine learning toward functionally validated biomarkers with direct therapeutic relevance.

A Practical Guide to ML Algorithms and Their Biomedical Applications

The advent of high-throughput technologies has enabled the comprehensive profiling of biological systems across multiple molecular layers, generating vast amounts of high-dimensional omics data. A fundamental challenge in analyzing these data is the "curse of dimensionality," where the number of features (e.g., genes, proteins, metabolites) vastly exceeds the number of samples, creating a high-dimensional, low-sample-size (HDLSS) scenario [35] [36]. This imbalance poses significant risks of overfitting and poor model generalization, ultimately compromising the reliability of identified biomarkers and biological insights. Feature selection techniques have thus become indispensable tools for navigating this complexity, serving to identify the most informative molecular features while discarding irrelevant or redundant variables [37].

The challenges are particularly pronounced in multi-omics studies, where datasets integrate various molecular layers such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics. These data types exhibit heterogeneous structures, varying scales, and different noise characteristics, creating unique analytical hurdles [38] [39]. Furthermore, omics datasets frequently suffer from class imbalance, where certain biological or clinical outcomes are underrepresented, potentially biasing predictive models [40]. Effective feature selection must therefore not only reduce dimensionality but also account for the complementary information embedded across omics modalities while maintaining biological relevance.

Feature Selection Methodologies and Comparative Performance

Categories of Feature Selection Approaches

Feature selection methods can be broadly categorized into three main types based on their integration with the modeling process. Filter methods evaluate the relevance of features based on statistical properties independent of any machine learning algorithm. Common examples include minimum Redundancy Maximum Relevance (mRMR), which selects features that have high mutual information with the target class but low mutual information with other features [37]. Embedded methods incorporate feature selection as part of the model training process; typical examples include Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator (Lasso), which performs regularization and variable selection simultaneously, and permutation importance from Random Forests (RF-VI) [37]. Wrapper methods use the performance of a predictive model to evaluate feature subsets, such as Recursive Feature Elimination (RFE) and Genetic Algorithms (GA), though these approaches tend to be computationally intensive [37].

Recent advancements have introduced ensemble and hybrid approaches that combine multiple selection strategies to enhance robustness. For instance, MCC-REFS employs an ensemble of eight machine learning classifiers and uses the Matthews Correlation Coefficient as a selection criterion, which is particularly effective for imbalanced datasets [40]. Similarly, Deep Learning-based feature selection methods, such as those incorporating transformer architectures, have shown promise in capturing complex, non-linear relationships in multi-omics data [41].

Benchmarking Studies and Performance Insights

Large-scale benchmarking studies provide critical insights into the relative performance of feature selection methods in omics contexts. A comprehensive evaluation using 15 cancer multi-omics datasets from The Cancer Genome Atlas revealed that mRMR, Random Forest permutation importance (RF-VI), and Lasso consistently outperformed other methods in predicting binary outcomes [37]. Notably, mRMR and RF-VI achieved strong predictive performance even with small feature subsets (e.g., 10-100 features), while other methods required larger feature sets to comparable performance [37].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Feature Selection Methods on Multi-omics Data

| Method | Type | Key Strengths | Performance Notes | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRMR | Filter | Selects non-redundant, informative features | High performance with small feature sets; best overall in multiple benchmarks | Moderate |

| RF-VI | Embedded | Robust to noise and non-linear relationships | Strong performance with few features; handles complex interactions | Low to Moderate |

| Lasso | Embedded | Simultaneous feature selection and regularization | Requires more features than mRMR/RF-VI; excellent predictive accuracy | Low |

| SVM-RFE | Wrapper | Model-guided feature elimination | Performance varies with classifier; can be effective with SVM | High |

| ReliefF | Filter | Sensitive to feature interactions | Lower performance with small feature sets | Moderate |

| Genetic Algorithm | Wrapper | Comprehensive search of feature space | Often selects too many features; computationally intensive | Very High |

The integration strategy—whether features are selected separately per omics type or concurrently across all omics—showed minimal impact on predictive performance for most methods. However, concurrent selection generally required more computation time [37]. This suggests that the choice between separate and concurrent integration may depend more on practical considerations than on performance gains for standard predictive tasks.

Practical Implementation Protocols

Automated Machine Learning Pipeline for Biomarker Discovery

The BioDiscML platform exemplifies an integrated approach to biomarker discovery, implementing a comprehensive pipeline that automates key machine learning steps [35]. The protocol begins with data preprocessing, where input datasets are merged (if multiple sources are provided) and split into training and test sets (typically 2/3 for training, 1/3 for testing). A feature ranking algorithm then sorts all features based on their predictive power, retaining only the top-ranked features (default: 1,000) to reduce dimensionality [35].

The core feature selection process employs two main strategies: top-k feature selection, which simply selects the best k elements from the ordered feature set, and stepwise selection, where features are sequentially added or removed based on performance improvement. For each candidate feature subset, the pipeline trains a model and evaluates performance using 10-fold cross-validation. This process is repeated across multiple machine learning algorithms, ultimately generating thousands of potential models [35]. The final output includes optimized feature signatures with associated performance metrics, providing researchers with actionable biomarker candidates.

Multi-omics Integration Framework for Survival Analysis

For complex endpoints such as survival outcomes, advanced integration frameworks are required. One such approach for breast cancer survival analysis employs genetic programming to adaptively select and integrate features across omics modalities [39]. The protocol begins with data preprocessing to handle missing values, normalize distributions, and align samples across omics platforms. The core integration phase uses genetic programming to evolve optimal combinations of molecular features, evaluating each candidate feature set based on its ability to predict survival outcomes using the concordance index (C-index) as the fitness metric [39].

The final model development phase constructs a survival model using the selected multi-omics features, typically employing Cox proportional hazards models or random survival forests. This approach has demonstrated robust performance in breast cancer survival prediction, achieving a C-index of 78.31 during cross-validation and 67.94 on independent test sets [39]. The adaptive nature of genetic programming allows the framework to identify complex, non-linear relationships between different molecular layers and clinical outcomes, often revealing biologically insightful interactions that might be missed by conventional methods.

Transformer-Based Deep Learning for Multi-omics Feature Selection

Recent advances in deep learning have introduced transformer-based architectures for multi-omics feature selection. In a study focused on hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), researchers developed a novel approach combining recursive feature selection with transformer models as estimators [41]. The protocol begins with data preparation from multiple mass spectrometry-based platforms, including metabolomics, lipidomics, and proteomics. Following data normalization and batch effect correction, the transformer model is trained to classify samples (e.g., HCC vs. cirrhosis) while simultaneously learning feature importance [41].

The key innovation lies in using the self-attention mechanisms of transformers to weight the importance of different molecular features across omics layers. Features are then recursively eliminated based on their attention scores, with the process repeating until an optimal feature subset is identified. This approach has demonstrated superior performance compared to sequential deep learning methods, particularly for integrating multi-omics data with limited sample sizes [41]. The selected features can subsequently be validated through pathway analysis tools to establish biological relevance and potential mechanistic insights.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-omics Feature Selection

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| BioDiscML | Automated biomarker discovery platform | General omics biomarker discovery [35] |

| MCC-REFS | Ensemble feature selection with MCC criterion | Imbalanced class datasets [40] |

| SMOPCA | Spatial multi-omics dimension reduction | Spatial domain detection in tissue samples [42] |

| MOFA+ | Bayesian group factor analysis | Multi-omics data integration [39] |

| Transformer-SVM | Deep learning feature selection | HCC biomarker discovery [41] |

| Genetic Programming Framework | Adaptive multi-omics integration | Survival analysis in breast cancer [39] |

Advanced Integration Strategies and Emerging Directions

Spatial Multi-omics Integration