How to Start in Computational Genomics: A 2025 Roadmap for Researchers and Drug Developers

This guide provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to launch a successful career in computational genomics.

How to Start in Computational Genomics: A 2025 Roadmap for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This guide provides a comprehensive roadmap for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to launch a successful career in computational genomics. It covers foundational knowledge from defining the field and essential skills to building a robust educational background. The article delves into core methodologies like NGS analysis and AI-powered tools, offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for data security and workflow efficiency, and concludes with frameworks for validating results and comparing analytical approaches to ensure scientific rigor. By synthesizing the latest trends, technologies, and training resources available in 2025, this article equips professionals to contribute meaningfully to advancements in biomedical research and precision medicine.

Building Your Base: Core Concepts and Career Paths in Computational Genomics

Computational biology represents a fundamental pillar of modern biomedical research, merging biology, computer science, and mathematics to decipher complex biological systems. This whitepaper delineates the core responsibilities, skill requirements, and transformative impact of computational biologists within the context of initiating research in computational genomics. We examine the field's evolution from a supportive function to a driver of scientific innovation, detail essential technical competencies and analytical workflows, and project career trajectories. The guidance provided herein equips researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the foundational knowledge to navigate and contribute to this rapidly advancing discipline.

The landscape of biological research has undergone a paradigm shift over the past two decades, transitioning toward data-centric science driven by the explosive growth of large-scale biological data and concurrent decreases in sequencing costs [1]. Computational biology has emerged as an indispensable discipline that uses computational and mathematical methods to develop models for understanding biological systems [2]. This field stands at the forefront of scientific inquiry, from decoding genetic regulation to unraveling complex cellular signaling pathways, holding the potential to revolutionize our understanding of nature and lead to groundbreaking discoveries [1].

The role of computational researchers has evolved significantly from providing supportive functions within research programs led by others to becoming leading innovators in scientific advancement [1]. This evolution reflects a cultural shift towards computational, data-centric research practices and the widespread sharing of data in the public domain, making computational biology an essential component of biomedical research [1]. The integration of computational methodologies with technological innovation has sparked a surge in interdisciplinary collaboration, accelerating bioinformatics as a mainstream component of biology and transforming how we study life systems [1].

What Computational Biologists Do: Core Functions and Methodologies

Primary Responsibilities and Daily Work

Computational biologists are professionals who deploy computational methods and technology to study and analyze biological data, operating at the intersection of biology, computer science, and mathematics [3]. Their core mandate is to manage and analyze the large-scale genomic datasets that are increasingly common in biomedical, biological, and public health research [4]. A key task involves developing and applying computational pipelines to analyze large and complex sets of biological data, including DNA sequences, protein structures, and gene expression patterns [3]. The analytical objectives are to identify patterns, relationships, and insights that advance our understanding of biological systems and to develop computer simulations that model these systems to test hypotheses and make predictions [3].

In practical terms, computational biologists are responsible for managing and interpreting diverse types of biological data by applying knowledge of molecular genetics, genome structure and organization, gene expression regulation, and modern technologies including genotyping, genome-seq, exome-seq, RNA-seq, and ChIP-seq [4]. They utilize major genomics data resources, develop skills in sequence analysis, gene functional annotation, and pathway analysis, and apply data mining, statistical analysis, and machine learning approaches to extract meaningful biological insights [4].

Impact Through Collaboration: The Case of Single-Cell Biology

The crucial role of computational biologists is exemplified in emerging fields like single-cell biology. The growth in the number and size of available single-cell datasets provides exciting opportunities to push the boundaries of current computational tools [5]. Computational biologists build "the bridge between data collection and data science" by creating novel computational resources and tools that embed biological mechanisms to uncover knowledge from the wealth of valuable atlas datasets [5]. This capability was demonstrated during the COVID-19 pandemic when early data from the Human Cell Atlas (HCA) was analyzed to identify cells in the nose with potential roles in spreading the virus—a finding that has since been cited by more than 1,000 other studies [5].

The Essential Toolkit: Skills, Education, and Technical Competencies

Educational Pathways and Requirements

Entering the field of computational biology requires a specific educational foundation that blends quantitative skills with biological knowledge. As shown in Table 1, postgraduate education is typically essential, with the majority of positions requiring advanced degrees.

Table 1: Computational Biology Career Entry Requirements

| Aspect | Typical Requirements |

|---|---|

| Education | Master's Degree (28.46%) or Doctoral Degree (77.69%) [2] |

| Common Programs | Computational Biology, Bioinformatics, Quantitative Genetics, Biostatistics [4] |

| Undergraduate Prep | Mathematical sciences or allied fields; Calculus; Linear algebra; Probability/Statistics; Molecular biology [4] |

| Experience | 0-2 years (33.47%) or 3-5 years (42.6%) [2] |

Harvard's Master of Science in Computational Biology and Quantitative Genetics provides a representative curriculum, including courses in applied regression analysis, introductory genomics and bioinformatics, epidemiological methods, and molecular biology for epidemiologists, with specialized tracks in statistical genetics or computational biology [4].

Technical and Professional Skills

Success in computational biology demands proficiency across multiple domains. The role requires not only technical expertise but also the ability to communicate findings effectively and collaborate across disciplines. Table 2 categorizes the most critical skills for computational biologists based on frequency of mention in job postings.

Table 2: Computational Biology Skills Taxonomy

| Skill Category | Specific Skills | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Defining Skills | Python (56.23%), Computational Biology (57.33%), Bioinformatics (51.68%), R (43.1%), Machine Learning (46.01%), Computer Science (41.65%), Biology (60.38%) [2] | Core to the occupation; frequently appears in job postings |

| Baseline Skills | Research (81.12%), Communication (39.37%), Writing (17.41%), Leadership (17.03%), Problem Solving (12.69%) [2] | Required across broad range of occupations |

| Necessary Skills | Data Science (21.99%), Artificial Intelligence (31.22%), Linux (11.28%), Biostatistics (12.95%), Drug Discovery (14.69%) [2] | Requested frequently but not specific to computational biology |

| Distinguishing Skills | Functional Genomics (5.96%), Computational Genomics (3.41%), Genome-Wide Association Study (2.38%) [2] | May distinguish a subset of the occupation |

Beyond these technical capabilities, computational biologists must develop strong analytical competencies, including the use of basic statistical inference and applied regression, survival, longitudinal, and Bayesian statistical analysis to identify statistically significant features that correlate with phenotype [4].

A Roadmap for Computational Genomics Research

Foundational Knowledge and Technical Setup

For researchers beginning in computational genomics, establishing a robust technical foundation is essential. This starts with understanding core genomic concepts and computational environments. Necessary biological background includes molecular genetics, human genome structure and organization, gene expression regulation, epigenetic regulation, and the applications of modern technologies like genotyping and various sequencing methods [4].

The computational foundation requires proficiency with UNIX commands, a scripting language (Python, Perl), an advanced programming language (C, C++, Java), and R/Bioconductor, along with familiarity with database programming and modern web technologies to interrogate biological data [4]. Establishing access to adequate computational resources is equally critical, as personal computational devices often lack sufficient storage or computational power to process large-scale data. Dry labs depend on high-performance computing clusters, cloud computing platforms, specialized software, and data storage systems to handle the complexities inherent in large-scale data analysis [1].

Core Analytical Workflow

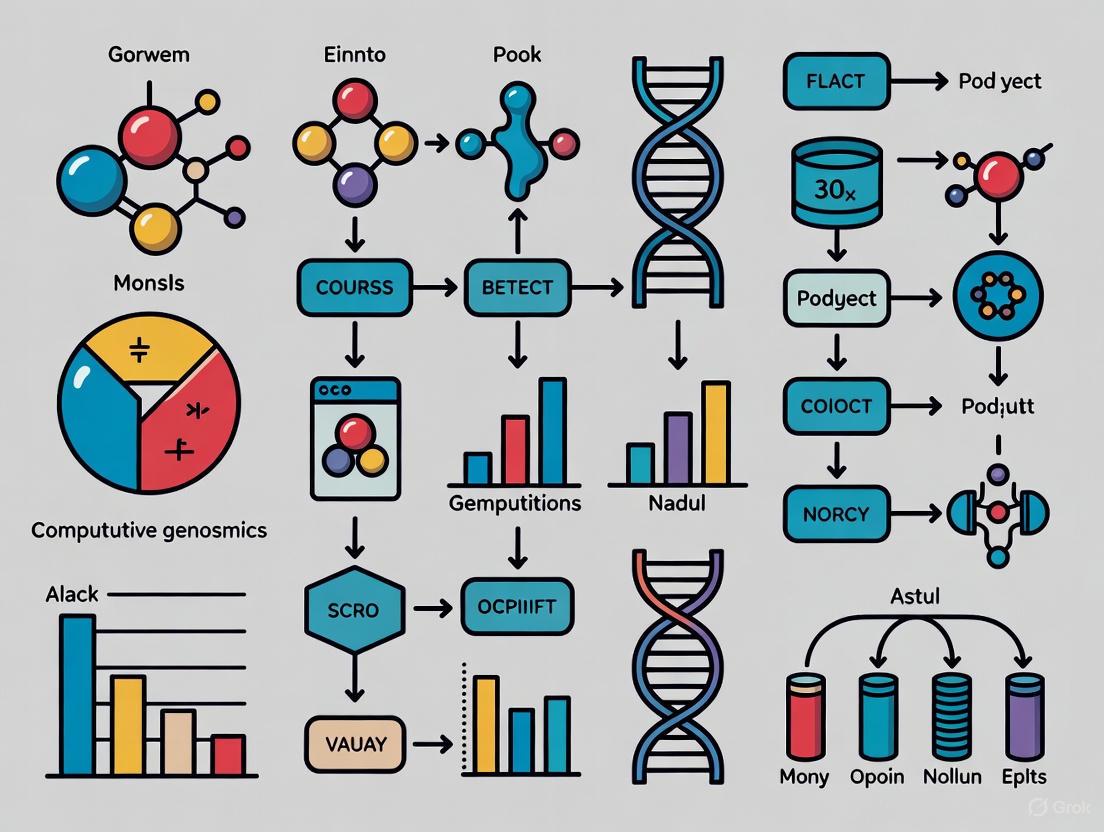

The analytical process in computational genomics follows a structured pathway from raw data to biological insight. The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for genomic data analysis:

This workflow transforms raw sequencing data through quality control, alignment, processing, and analysis stages, culminating in biological interpretation and visualization. Downstream analysis may include variant calling, differential expression, epigenetic profiling, or other specialized analytical approaches depending on the research question.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Computational research relies on specialized resources and platforms rather than traditional wet lab reagents. Table 3 details key computational "research reagents" essential for genomic analysis.

Table 3: Essential Computational Research Reagents and Resources

| Resource Category | Examples | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Data Repositories | NCBI, EMBL-EBI, DDBJ, UniProt, Gene Ontology [1] | Centralized repositories for biological data; provide standardized annotations and functional information |

| Cloud Platforms | AWS, Google Cloud, Microsoft Azure [1] | Scalable storage and processing infrastructure for large-scale data |

| Analysis Tools/Frameworks | R/Bioconductor, Python, CZ CELLxGENE [1] [5] [4] | Programming environments and specialized platforms for genomic data manipulation and exploration |

| Computing Environments | High-performance computing clusters, Linux systems [1] | Computational power necessary for processing complex datasets |

Effective visualization represents a crucial final step in the analytical process. When creating biological data visualizations, follow established principles for colorization: identify the nature of your data (nominal, ordinal, interval, ratio), select an appropriate color space (preferably perceptually uniform spaces like CIE Luv/Lab), check color context, assess color deficiencies, and ensure accessibility for both web and print [6] [7].

Career Outlook and Professional Opportunities

Employment Landscape and Compensation

The job market for computational biologists demonstrates robust demand across multiple sectors. Recent data indicates 2,860 job postings in the United States over a one-year period, with 42 positions specifically in North Carolina [2]. The field offers competitive compensation, with an average estimated salary of $117,447 nationally, though regional variation exists (e.g., $85,564 in North Carolina) [2]. Salary percentiles reveal that 25% of positions offered less than $83,788, indicating significant earning potential for experienced professionals [2].

Employment opportunities span diverse settings, including universities, hospitals, research organizations, pharmaceutical companies, and biotechnology firms [4]. Top employers include leading research institutions and pharmaceutical companies such as Genentech, Merck & Co., Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and major cancer centers [2].

Evolving Roles and Future Directions

The field of computational biology continues to evolve with emerging areas of specialization and research focus. Single-cell biology represents one rapidly expanding frontier where computational biologists are essential for integrating datasets, scaling to higher dimensionalities, mapping new datasets to reference atlases, and developing benchmarking frameworks [5]. The Chan Zuckerberg Initiative's funding programs specifically support computational biologists working to advance tools and resources that generate greater insights into health and disease from single-cell biology datasets [5].

The future direction of computational biology will likely involve increased emphasis on method standardization, toolchain interoperability, and the development of robust benchmarking frameworks that enable comparison of analytical tools [5]. Additionally, as the volume and complexity of biological data continue to grow, computational biologists will play an increasingly critical role in bridging domains and fostering collaborative networks between experimental and computational research communities [1] [5].

Computational biology has matured from an ancillary support function to an independent scientific domain that drives innovation in biomedical research. This whitepaper has delineated the core responsibilities, required competencies, analytical workflows, and career pathways that define the field. For researchers embarking in computational genomics, success requires developing interdisciplinary expertise across biological and computational domains, establishing proficiency with essential tools and platforms, and engaging with the collaborative networks that propel the field forward. As biological data continues to grow in scale and complexity, the role of computational biologists will become increasingly crucial to extracting meaningful insights, advancing scientific understanding, and developing novel approaches to address complex biological questions in human health and disease.

Computational genomics stands as a quintessential interdisciplinary field, representing a powerful synergy of biology, computer science, and statistics. Its primary aim is to manage, analyze, and interpret the vast and complex datasets generated by modern high-throughput genomic technologies [8] [1]. This fusion has become the backbone of contemporary biological research, enabling discoveries that were once unimaginable. The field has evolved from a supportive role into a leading scientific discipline, driven by the exponential growth of biological data and the continuous development of sophisticated computational methods [1]. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals embarking on a journey in computational genomics, mastering the integration of these three core domains is not merely beneficial—it is essential for transforming raw data into meaningful biological insights and actionable outcomes in areas such as drug discovery, personalized medicine, and agricultural biotechnology [8] [9]. This guide provides a detailed roadmap of the essential skill sets required to navigate and excel in this dynamic field.

Foundational Knowledge Domains

A successful computational genomicist operates at the intersection of three distinct yet interconnected domains. A deep understanding of each is crucial for designing robust experiments, developing sound analytical methods, and drawing biologically relevant conclusions.

Biology and Genomics: This domain provides the fundamental questions and context. Essential knowledge includes Molecular Biology (understanding the central dogma, gene regulation, and genetic variation) [9], Genetics (principles of heredity and genetic disease) [9], and Genomics (the structure, function, and evolution of genomes) [8] [9]. Furthermore, familiarity with key biological databases is a critical skill, allowing researchers to retrieve and utilize reference data effectively [10]. These databases include GenBank (nucleotide sequences), UniProt (protein sequences and functions), and Ensembl (annotated genomes) [8] [9] [11].

Computer Science and Programming: This domain provides the toolkit for handling data at scale. Proficiency in programming is the gateway skill [10]. Python and R are the dominant languages in the field; Python is prized for its general-purpose utility and libraries like Biopython, while R is exceptional for statistical analysis and data visualization [9] [10]. The ability to work in a UNIX/Linux command-line environment is indispensable for running specialized bioinformatics tools and managing computational workflows [12]. Additionally, knowledge of database management (SQL/NoSQL) and algorithm fundamentals is vital for developing efficient and scalable solutions to biological problems [9].

Statistics and Mathematics: This domain provides the framework for making inferences from data. A solid grounding in probability and statistical inference is necessary for hypothesis testing and estimating uncertainty [10]. Key concepts include descriptive and inferential statistics, hypothesis testing, and multiple testing corrections like False Discovery Rate (FDR) [10]. With the rise of complex, high-dimensional data, machine learning has become a core component for tasks such as biomarker discovery, classification, and predictive modeling [10] [13]. Techniques such as clustering, principal component analysis (PCA), and the use of models like XGBoost and TensorFlow are increasingly important [10].

The diagram below illustrates how these three domains converge and interact in a typical computational genomics research workflow, from data acquisition to biological insight.

Core Technical Skills and Tools

Translating foundational knowledge into practical research requires proficiency with a specific set of technical skills and tools. The following table summarizes the key technical competencies for a computational genomicist.

Table 1: Core Technical Skills for Computational Genomics

| Skill Category | Specific Technologies & Methods | Primary Application in Genomics |

|---|---|---|

| Programming & Data Analysis | Python (Biopython, pandas), R (ggplot2, DESeq2), UNIX command line [9] [10] | Data manipulation, custom script development, statistical analysis, and workflow automation. |

| Sequencing Data Analysis | FastQC, STAR, GATK, Salmon, MultiQC [10] | Quality control, read alignment, variant calling, gene expression quantification, and report generation for NGS data. |

| Statistical Modeling & Machine Learning | scikit-learn, XGBoost, TensorFlow/PyTorch; PCA, clustering, classification [10] | Biomarker discovery, pattern recognition in large datasets, and predicting biological outcomes. |

| Data Visualization | ggplot2 (R), Matplotlib/Seaborn (Python), Cytoscape [9] [11] | Creating publication-quality figures (heatmaps, PCA plots, volcano plots) and biological network diagrams. |

| Workflow Management & Reproducibility | Nextflow, nf-core, Galaxy, Git [10] [14] | Building reproducible, shareable, and scalable analysis pipelines. |

In computational genomics, software, data, and computing resources are the essential "research reagents." The table below details the key components of a modern computational toolkit.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Computational Genomics

| Item | Function | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Programming Languages & Libraries | Provide the environment for data manipulation, analysis, and custom algorithm development. | Python, R, Biopython, pandas, scikit-learn, DESeq2 [9] [10]. |

| Bioinformatics Software Suites | Perform specific, often complex, analytical tasks such as sequence alignment or structural visualization. | BLAST, Clustal Omega, Cytoscape, PyMOL, GROMACS [8] [9] [11]. |

| Biological Databases | Serve as curated repositories of reference data for annotation, comparison, and hypothesis generation. | GenBank, UniProt, Ensembl, PDB, KEGG [8] [9] [10]. |

| Workflow Management Systems | Ensure reproducibility and scalability by orchestrating multi-step analytical processes. | Nextflow, nf-core, Galaxy [11] [10]. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Provides the necessary computational power and storage to process and analyze large-scale datasets. | Local computing clusters, cloud platforms (AWS, Google Cloud, Azure) [1] [13]. |

Practical Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Success in computational genomics research hinges on more than just technical skill; it requires rigorous methodology and adherence to best practices for scientific integrity.

Protocol for a Reproducible NGS Analysis Workflow

A typical RNA-Seq analysis, which quantifies gene expression, provides an excellent example of a standard computational protocol. The following diagram outlines the major steps in this workflow.

1. Experimental Design and Data Acquisition:

- Objective: To identify genes that are differentially expressed between two biological conditions (e.g., diseased vs. healthy tissue).

- Methodology: Before analysis, ensure the experiment is properly designed with sufficient biological replicates to achieve statistical power. Raw sequencing data in FASTQ format is obtained from the sequencing facility [10].

2. Quality Control and Preprocessing:

- Objective: Assess read quality and remove low-quality sequences to prevent artifacts in downstream analysis.

- Methodology: Use FastQC for initial quality assessment of FASTQ files. Subsequently, employ tools like Trimmomatic or cutadapt to trim adapter sequences and low-quality bases from reads [10].

3. Alignment and Quantification:

- Objective: Map the cleaned sequencing reads to a reference genome and count the number of reads per gene.

- Methodology: Use a splice-aware aligner like STAR or HISAT2 to align reads to the reference genome. Alternatively, for faster quantification, a tool like Salmon can be used which aligns reads transcriptome-wide without generating a full BAM file. Generate a count matrix representing the expression level of each gene in each sample [10].

4. Differential Expression Analysis:

- Objective: Statistically identify genes whose expression levels are significantly different between the experimental conditions.

- Methodology: Import the count matrix into R and use a specialized package like DESeq2 or edgeR. These tools model count data using statistical distributions (e.g., negative binomial) and perform normalization and hypothesis testing to calculate p-values and false discovery rates (FDR) for each gene [10].

5. Interpretation and Visualization:

- Objective: Understand and communicate the results.

- Methodology: Create visualizations such as PCA plots to assess sample similarity, volcano plots to visualize the relationship between statistical significance and magnitude of change, and heatmaps to display expression patterns of significant genes across samples [10]. Functional analysis of the resulting gene list using pathway databases like KEGG is then performed for biological interpretation.

Adopting FAIR Principles and Open Science

For computational work to have lasting impact, it must be reproducible. Adhering to the FAIR principles—making data and code Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable—is a critical methodology in itself [14]. This involves:

- Using version control systems like Git to track changes in analysis code [14].

- Utilizing workflow managers like Nextflow and nf-core to create self-documented, portable analysis pipelines [10].

- Depositing code in public repositories (e.g., GitHub) and data in public archives (e.g., GenBank, GEO) upon publication [1].

The integration of biology, computer science, and statistics forms the bedrock of modern computational genomics. As the field continues to evolve with advancements in AI, multi-omics integration, and cloud computing, the demand for professionals who can seamlessly blend these skill sets will only intensify [1] [13]. For the aspiring researcher or drug development professional, a commitment to continuous learning and interdisciplinary collaboration is paramount. By mastering the foundational knowledge, technical tools, and rigorous methodologies outlined in this guide, one is well-equipped to contribute meaningfully to this exciting and transformative field, driving innovation from the bench to the bedside.

The journey from academic research in computational genomics to a career in pharmaceutical drug discovery represents a strategic and impactful career trajectory. This path leverages deep expertise in computational biology, statistical genetics, and data analysis to address core challenges in modern therapeutic development. Computational biology, an interdisciplinary science that utilizes computer tools, statistics, and mathematics to answer complex biological questions, has become a critical component of genomic research and drug discovery [15]. The ability to sequence and analyze organisms' DNA has revolutionized biology, enabling researchers to understand how genomes function and how genetic changes affect life processes. This foundation is directly applicable to the drug discovery process, where researchers must evaluate thousands of molecular compounds to identify candidates for development as medical treatments [16]. For computational genomics researchers considering this transition, understanding how their skills map onto the drug development pipeline is essential for successfully navigating this career path and making meaningful contributions to human health.

Foundational Skills from Academic Computational Genomics

Academic training in computational genomics provides the essential foundation for contributing to drug discovery research. This foundation encompasses both technical proficiencies and conceptual understanding of biological systems.

Core Computational and Analytical Competencies:

- Programming and Scripting: Working knowledge of scripting and programming languages like R, Python, and Java is paramount for computational biologists [15]. These skills enable the development of custom analytical pipelines and the adaptation of existing tools to novel problems.

- Data Management and Analysis: The ability to organize, analyze, and visualize data from genomic sciences is fundamental [15]. This includes experience with large-scale genomic datasets, such as those generated by high-throughput sequencing technologies, which can involve managing data from a single human genome sequence of approximately 200 gigabytes [15].

- Algorithm and Tool Development: Computational biologists often develop and apply analytical methods and mathematical modeling techniques to study genomic systems [15]. This includes creating new algorithms for tasks such as genome assembly, variant identification, and comparative genomics.

- Statistical and Quantitative Genetics: Understanding of genetic analysis of quantitative or complex traits based on statistical quantities such as genetic variances and heritability provides a crucial framework for analyzing the genetic basis of diseases and treatment responses [17].

Biological and Domain Knowledge:

A successful transition requires more than technical prowess. A strong understanding of biological systems is indispensable, typically gained through life sciences coursework and research experience [15]. This knowledge enables meaningful interpretation of computational results within their biological context. Additionally, experience with specific genomic methodologies—such as comparative genomics, which identifies evolutionarily conserved DNA sequences to understand gene function and influence on organismal health—provides directly transferable skills for target identification and validation in drug discovery [15].

Table 1: Core Competencies for Computational Genomics in Drug Discovery

| Competency Area | Specific Skills | Drug Discovery Application |

|---|---|---|

| Technical Programming | R, Python, Java, SQL | Data analysis, pipeline development, tool customization |

| Data Analysis | Statistical modeling, data visualization, pattern recognition | Biomarker identification, patient stratification, efficacy analysis |

| Genomic Methodologies | Genome assembly, variant calling, comparative genomics | Target identification, mechanism of action studies |

| Domain Knowledge | Molecular biology, genetics, biochemistry | Target validation, understanding disease mechanisms |

The Drug Discovery and Development Pipeline

Understanding the complete drug discovery and development process is essential for computational genomics researchers transitioning to pharmaceutical careers. This process is lengthy, complex, and requires interdisciplinary collaboration, typically taking 10-15 years and costing billions of dollars to bring a new treatment to market [16].

3.1 Drug Discovery Stage

The discovery stage represents the initial phase of bringing a new drug to market. During this stage, researchers evaluate compounds to determine which could be candidates for development as medical treatments [16]. The process begins with the identification of a target molecule, typically a protein or other molecule involved in the disease process. Computational genomics plays a crucial role in this phase through the analysis of genetic associations, gene expression data, and proteomics data to identify and prioritize potential disease targets [18]. The process of developing a new drug from original idea to a finished product is complex and involves building a body of supporting evidence before selecting a target for a costly drug discovery program [18].

Once a target is identified, scientists must design and synthesize new compounds that will interact with the target molecule and influence its function. Researchers use several methods in the discovery process, including testing numerous molecular compounds for possible benefits against diseases, re-testing existing treatments for benefits against other diseases, using new information about diseases to design products that could stop or reverse disease effects, and adopting new technologies to treat diseases [16]. The scale of this screening process is immense—for every 10,000 compounds tested in the discovery stage, only 10-20 typically move on to the development phase, with approximately half of those ultimately proceeding into preclinical trials [16].

3.2 Preclinical and Clinical Development Stages

After identifying a promising compound, it enters the preclinical research development stage, where researchers conduct non-clinical studies to assess toxicity and activity in animal models and human cells [16]. These studies must provide detailed information on the drug's pharmacology and toxicity levels following Good Laboratory Practices (GLP) regulations. Simultaneously, developers work on dosage formulation development and manufacturing according to Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP) standards [16].

The clinical development stage consists of three formal phases of human trials [16]:

- Phase I trials are small, single-dose studies conducted in healthy volunteers (20-100 people) to assess compound safety, examining how the compound moves through the body and identifying serious side effects.

- Phase II trials are larger (several hundred people), multi-dose studies in patients with the target disease to determine if the new compound improves their condition and has any adverse side effects. These trials generate initial efficacy data and help determine appropriate dosing.

- Phase III trials are the largest and most rigorous, conducted in hundreds to thousands of patients with the disease to establish definitive efficacy and safety profiles. These trials require extensive collaboration and organization, with only 12% of drugs successfully completing this stage [16].

Following successful clinical trials, developers submit a New Drug Application (NDA) or Biologics License Application (BLA) to regulatory authorities like the FDA, containing all clinical results, proposed labeling, safety updates, and manufacturing information [16]. Even after approval, post-marketing monitoring (Phase IV) continues to understand long-term safety, effectiveness, and benefits-risk balance in expanded patient populations.

Diagram 1: Drug Development Pipeline from Discovery to Market

Table 2: Key Stages in Pharmaceutical Development with Computational Genomics Applications

| Development Stage | Primary Activities | Computational Genomics Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Target Identification & Validation | Identify and verify biological targets involved in disease | Genetic association studies, gene expression analysis, pathway analysis [18] |

| Lead Discovery & Optimization | Screen and optimize compounds for efficacy and safety | Structure-based drug design, virtual screening, QSAR modeling [19] |

| Preclinical Development | Assess toxicity and activity in model systems | Toxicogenomics, biomarker identification, pharmacokinetic modeling |

| Clinical Trials | Evaluate safety and efficacy in humans | Patient stratification, pharmacogenomics, clinical trial simulation |

| Regulatory Submission & Post-Market | Document efficacy/safety and monitor long-term effects | Real-world evidence generation, pharmacovigilance analytics |

Transitioning from Academia to Industry: A Practical Guide

Making the transition from academic research to the pharmaceutical industry requires both strategic preparation and mindset adjustment. Researchers who have successfully navigated this path emphasize the importance of understanding motivations, networking effectively, and adapting to industry culture.

4.1 Motivation and Mindset

A common motivation for transitioning scientists is the desire to see their work have more direct impact on patients [20]. As Magdia De Jesus, PhD, now at Pfizer's Vaccine Research and Development Unit, explained: "I wanted to make a larger impact across science. I felt I needed to do something bigger. I wanted to learn how to develop a real vaccine that goes into the arms of patients" [20]. This patient-centric focus differentiates much of industry work from basic academic research.

The decision to transition requires careful consideration. Sihem Bihorel, PharmD, PhD, a senior director at Merck & Co., noted: "This is not a decision that you make very easily. You think about it, you consult with friends, with colleagues and others, and you weigh the pros and cons. You always know what you are leaving, but you don't know what you are going to get" [20]. Successful transitions often involve overcoming misconceptions about industry work, particularly regarding research freedom and publication opportunities. As Bihorel discovered, "I had the perception that industry was a very closed environment. I have to admit I was completely wrong. What I thought were challenges — things that were holding me back from making the decision — in the end turned out to be positives" [20].

4.2 Strategic Networking and Preparation

Building connections within the industry is crucial for a successful transition. The panelists encouraged reaching out to researchers for informational interviews to better understand what it's like to work at specific companies [20]. Many scientists in industry are former professors who have undergone similar transitions and can provide valuable insights. Networking helps candidates identify suitable positions, understand company cultures, and prepare for interviews.

For computational genomics researchers specifically, highlighting transferable skills is essential. These include:

- Experience with large-scale data analysis and interpretation

- Proficiency with relevant programming languages and analytical tools

- Understanding of biological systems and disease mechanisms

- Ability to work in interdisciplinary teams

- Project management and communication skills

Stacia Lewandowski, PhD, a senior scientist at Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research, emphasized that despite initial concerns, she found industry work equally intellectually stimulating: "I still feel just as invigorated and enriched as I did as a postdoc and grad student, maybe a little bit more" [20].

Key Methodologies: Bridging Both Worlds

5.1 Target Identification and Validation

Target identification represents one of the most direct applications of computational genomics to drug discovery. This process involves identifying biological targets (proteins, genes, RNA) whose modulation is expected to provide therapeutic benefit [18]. Computational approaches include data mining of biomedical databases, analysis of gene expression patterns in diseased versus healthy tissues, and identification of genetic associations through genome-wide association studies (GWAS) [18].

Following identification, targets must be validated to establish confidence in the relationship between target and disease. A multi-validation approach significantly increases confidence in the observed outcome [18]. Methodologies include:

- Antisense Technology: Using chemically modified oligonucleotides complementary to target mRNA to prevent synthesis of encoded proteins [18]

- Transgenic Animals: Generating gene knockouts or knock-ins to observe phenotypic consequences of gene manipulation [18]

- RNA Interference (RNAi): Utilizing small interfering RNA (siRNA) to silence specific genes and assess functional consequences [18]

- Monoclonal Antibodies: Employing highly specific antibodies to inhibit target protein function and validate therapeutic effects [18]

- Chemical Genomics: Applying diversity-oriented chemical libraries and high-content cellular assays to probe gene function [18]

5.2 Experimental Protocols for Genomic Analysis in Drug Discovery

Protocol 1: In Silico Target Prioritization Pipeline

- Data Collection: Aggregate genomic data from public repositories (e.g., ChEMBL, which contains over 2.4 million compounds with testing data) or internal sources [19]

- Genetic Association Analysis: Identify variants correlated with disease risk or progression using statistical genetics approaches

- Expression Profiling: Analyze transcriptomic data to identify differentially expressed genes in disease states

- Pathway Enrichment Analysis: Place candidate targets in biological context using pathway databases and network analysis tools

- Druggability Assessment: Evaluate structural and chemical properties that determine whether a target is amenable to therapeutic modulation

- Multi-Parameter Prioritization: Integrate evidence across data types to rank targets for experimental follow-up

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Screening Data Analysis

- Data Quality Control: Implement normalization procedures and quality metrics to identify technical artifacts in screening data

- Hit Identification: Apply statistical methods to distinguish true positive signals from background noise

- Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) Analysis: Identify chemical features associated with biological activity using machine learning approaches

- Compound Prioritization: Integrate efficacy, selectivity, and chemical properties to select lead compounds for optimization

Diagram 2: Computational Target Identification Workflow

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Genomics in Drug Discovery

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Drug Discovery |

|---|---|---|

| Bioinformatics Databases | ChEMBL, PubMed, patent databases | Provide compound and target information for data mining and hypothesis generation [19] [18] |

| Genomic Data Resources | Gene expression datasets, proteomics data, transgenic phenotyping data | Enable target identification and validation through analysis of gene-disease relationships [18] |

| Chemical Libraries | Diversity-oriented chemical libraries, compound profiling data | Support chemical genomics approaches to target identification and validation [18] |

| Interrogation Tools | Antisense oligonucleotides, siRNA, monoclonal antibodies, tool compounds | Facilitate target validation through functional modulation studies [18] |

| Analytical Software | R, Python, specialized packages for statistical genetics | Enable data analysis, visualization, and interpretation across discovery stages |

The career trajectory from academic computational genomics to pharmaceutical drug discovery offers exciting opportunities to apply cutting-edge scientific expertise to address significant unmet medical needs. This path requires both strong technical foundations in computational methods and the ability to translate biological insights into therapeutic strategies. By understanding the complete drug development pipeline, developing relevant skills, and strategically networking within the industry, computational genomics researchers can successfully navigate this transition. As the field continues to evolve with advances in technologies like artificial intelligence and increasingly complex multimodal data, the role of computational expertise in drug discovery will only grow in importance. For researchers considering this path, the experiences of those who have successfully transitioned underscore the potential for both professional fulfillment and meaningful contribution to human health.

The field of computational genomics represents a critical intersection of biological science, computational technology, and statistical analysis, driving innovations in drug development, personalized medicine, and fundamental biological discovery. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to enter this rapidly evolving discipline, navigating the educational landscape requires a strategic approach combining formal academic training with targeted self-study. The complexity of modern genomic research demands professionals who can develop and apply novel computational methods for analyzing massive-scale genetic, genomic, and health data to address pressing biological and medical challenges [21]. These methodologies include advanced techniques from computer science and statistics such as machine learning, artificial intelligence, and causal inference, applied to diverse areas including variant detection, disease risk prediction, single-cell analysis, and multi-omics data integration.

This guide provides a comprehensive framework for building expertise in computational genomics through three complementary pathways: structured university programs delivering formal credentials, curated self-study resources for skill-specific development, and practical experimental protocols that translate theoretical knowledge into research capabilities. By mapping the educational ecosystem from foundational to advanced topics, we enable professionals to construct individualized learning trajectories that align with their research goals and career objectives within the pharmaceutical and biotechnology sectors. The following sections detail specific programs, resources, and methodologies that collectively form a robust foundation for computational genomics proficiency.

University Degrees and Certificate Programs

Formal academic programs provide structured educational pathways with rigorous curricula, expert faculty guidance, and recognized credentials that validate expertise in computational genomics. These programs typically integrate core principles from computational biology, statistics, and molecular genetics, offering both broad foundational knowledge and specialized training in advanced methodologies. For professionals in drug development, such programs deliver the theoretical underpinnings and practical skills necessary to manage and interpret complex genomic datasets in research and clinical contexts.

Table 1: Graduate Certificate Programs in Computational Genomics

| Institution | Program Name | Core Focus Areas | Notable Faculty |

|---|---|---|---|

| University of Washington | Graduate Certificate in Computational Molecular Biology | Computational biology, genome sciences, statistical analysis | Su-In Lee (AI in Biomedicine), William Noble (Statistical Genomics), Sara Mostafavi (Computational Genetics) [22] |

| Harvard University | Program in Quantitative Genomics | Statistical genetics, genetic epidemiology, computational biology, molecular biology | Interdisciplinary faculty across Harvard Chan School [23] |

University certificate programs offer focused, advanced training that can significantly enhance a researcher's capabilities without the time investment of a full degree program. The University of Washington's Computational Molecular Biology certificate exemplifies this approach, representing a cooperative effort across ten research departments and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center [22]. This program facilitates connections across the computational biology community while providing formal recognition for specialized coursework and research. Similarly, Harvard's Program in Quantitative Genomics (PQG) emphasizes interdisciplinary research approaches, developing and applying quantitative methods to handle massive genetic, genomic, and health data with the goal of improving human health through integrated study of genetics, behavior, environment, and health outcomes [23].

For researchers seeking comprehensive training, numerous universities offer full graduate degrees with specialized tracks in computational genomics. Yale University's Biological and Biomedical Sciences program, for instance, includes a computational genomics research area focused on developing and applying new computational methods for analyzing and interpreting genomic information [21]. Such programs typically feature faculty with diverse expertise spanning statistical genetics, machine learning applications, variant impact prediction, gene discovery, and genomic privacy. These academic hubs provide not only formal education but also crucial networking opportunities through seminars, collaborations, and exposure to innovative research methodologies directly applicable to drug development challenges.

For professionals unable to pursue full-time academic programs or seeking to address specific skill gaps, self-study resources provide a flexible alternative for developing computational genomics expertise. A structured approach to self-directed learning should encompass five critical domains: programming proficiency, genetics and genomics knowledge, mathematical foundations, machine learning competency, and practical project experience. This multifaceted strategy ensures comprehensive skill development that mirrors the integrated knowledge required for effective research in drug development contexts.

Table 2: Curated Self-Study Resources for Computational Genomics

| Skill Category | Recommended Resources | Specific Applications in Genomics |

|---|---|---|

| Programming | DataQuest Python courses; "Python for Data Analysis"; DataCamp SQL courses; R with "R for Everyone" [24] | Data wrangling with Pandas; Genomic data processing; Statistical analysis with R |

| Genomics & Bioinformatics | Biostar Handbook; Rosalind problem-solving; GATK Best Practices; SAMtools [24] [25] | Variant calling pipelines; NGS data processing; Sequence analysis algorithms |

| Mathematics & Machine Learning | Coursera Mathematics for ML; Fast.ai Practical Deep Learning; "Python Machine Learning" [24] | Predictive model building; Linear algebra for algorithms; Statistical learning |

| Data Integration & Analysis | EdX Genomic Data Science; Coursera Genomic Data Science Specialization [24] | Multi-omics data integration; EHR and genomic data analysis; Biobank-scale analysis |

A progressive learning pathway begins with establishing computational foundations through Python and R programming, focusing specifically on data manipulation, statistical analysis, and visualization techniques relevant to genomic datasets [24]. Subsequent specialization in genomic tools and methodologies should include hands-on experience with industry-standard platforms like the Genome Analysis Tool Kit (GATK) for variant discovery and SAMtools for processing aligned sequence data [24]. The Biostar Handbook provides particularly valuable context for bridging computational skills with biological applications, offering practical guidance on analyzing high-throughput sequencing data, while platforms like Rosalind strengthen problem-solving abilities through bioinformatics challenges [24].

Advanced self-study incorporates mathematical modeling and machine learning techniques specifically adapted to genomic applications. Key resources include linear algebra courses focused on computer science implementations, statistical learning texts with genomic applications, and specialized training in deep learning architectures relevant to biological sequence analysis [24]. The most critical component, however, involves applying these skills to authentic research problems through platforms like Kaggle, which hosts genomic prediction challenges, or by analyzing public datasets from sources such as the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus [24]. This project-based approach solidifies abstract concepts through practical implementation, building a portfolio of demonstrated capabilities directly relevant to drug development research. Documenting this learning journey through technical blogs or GitHub repositories further enhances knowledge retention and provides tangible evidence of expertise for career advancement.

Experimental Protocols and Computational Methodologies

Translating theoretical knowledge into practical research capabilities requires familiarity with established experimental protocols and computational workflows in computational genomics. The following section details representative methodologies that illustrate the application of computational approaches to fundamental genomic analysis tasks, providing researchers with templates for implementing similar analyses in their drug development research.

RNA Biomarker Identification for Disease Research

This protocol outlines a comprehensive approach for identifying RNA biomarkers associated with specific diseases using gene expression data, a methodology particularly relevant to early-stage drug target discovery and biomarker identification in pharmaceutical development.

Experimental Workflow:

- Dataset Selection and Acquisition: Obtain RNA expression datasets from public repositories (e.g., GEO, TCGA) or internal sources, ensuring appropriate sample sizes for case-control comparisons relevant to the disease of interest.

- Quality Control and Preprocessing: Implement quality assessment using FastQC (for raw sequencing data) followed by adapter trimming, alignment to reference genomes, and generation of expression count matrices.

- Differential Expression Analysis: Perform statistical comparisons (e.g., T-tests with multiple testing correction) to identify significantly dysregulated genes between experimental conditions.

- Functional Enrichment Analysis: Interpret results through pathway analysis (KEGG, Reactome) and gene ontology enrichment to identify biological processes disrupted in the disease state.

- Validation and Prioritization: Confirm findings in independent datasets and prioritize candidate biomarkers based on effect size, statistical significance, and biological plausibility.

This workflow mirrors approaches used in educational settings to introduce computational biology concepts, where students determine a disease focus, collaborate on researching the disease, and work to identify novel diagnostic or therapeutic targets [26].

Cross-Biobank Analysis for Genetic Epidemiology

Large-scale biobank data analysis represents a cutting-edge methodology in computational genomics, enabling genetic discovery through integration of diverse datasets. This approach is particularly valuable for drug development professionals seeking to validate targets across populations and understand the genetic architecture of complex diseases.

Experimental Workflow:

- Data Harmonization: Process genotype and phenotype data from multiple biobanks through standardized quality control pipelines, addressing population stratification, relatedness, and heterogeneity across datasets [27].

- Variant Association Testing: Conduct genome-wide association studies within individual biobanks using standardized statistical approaches, then meta-analyze results across biobanks using fixed or random effects models.

- Polygenic Risk Score Construction: Develop and validate polygenic risk models using clumping and thresholding or Bayesian approaches, assessing transferability across diverse ancestral backgrounds [27].

- Functional Annotation: Annotate associated variants using functional genomic data (e.g., epigenomic marks, chromatin conformation) to prioritize likely causal mechanisms.

- Cross-Biobank Replication: Validate findings through independent replication in held-out biobank samples or published consortium data.

This methodology addresses the unique computational challenges of biobank-scale data, including efficient computational workflows, privacy-preserving analysis methods, and approaches for harmonizing summary statistics from multiple sources [27]. The protocol emphasizes practical considerations for researchers, including data access procedures, security requirements, and reproducibility frameworks essential for robust genetic epidemiology research.

Visualization of Computational Genomics Workflows

Effective visualization of computational workflows enables researchers to understand, communicate, and optimize complex analytical processes in genomics research. The following diagrams illustrate key workflows and relationships in computational genomics education and research.

Computational Genomics Education Pathway

Genomic Data Analysis Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Computational genomics research relies on a suite of analytical tools and platforms that function as "research reagents" in the digital domain. These resources enable the processing, analysis, and interpretation of genomic data, forming the essential toolkit for researchers in both academic and pharmaceutical settings.

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Genomics Research

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Programming Environments | Python with Pandas/Scikit-learn; R with Tidyverse/Bioconductor | Data manipulation, statistical analysis, visualization | General-purpose genomic data analysis and machine learning [24] |

| Genome Analysis Tools | GATK; SAMtools; BEDTools | Variant discovery, sequence data processing, genomic intervals | Processing NGS data; variant calling; manipulation of aligned data [24] |

| Workflow Management | WDL; Snakemake; Nextflow | Pipeline orchestration, reproducibility, scalability | Building robust, reusable analysis pipelines for production environments [24] |

| Specialized Learning Platforms | Rosalind; Biostar Handbook; Computational Genomics Tutorials | Bioinformatics skill development, problem-solving | Educational contexts for building specific competencies [24] [25] |

| Data Resources | Public Biobanks; GEO; TCGA; Kaggle Genomic Datasets | Source of genomic datasets for analysis | Providing raw materials for analysis and method development [24] [27] |

These computational reagents serve analogous functions to laboratory reagents in experimental biology, enabling specific, reproducible manipulations of genomic data. For example, GATK implements best practices for variant discovery across different sequencing applications (genomics, transcriptomics, somatic mutations), while tools like SAMtools provide fundamental operations for working with aligned sequencing data [24]. Programming environments like Python and R, with their extensive ecosystems of domain-specific packages, constitute the basic solvent in which most computational analyses are performed—the flexible medium that enables custom workflows and novel analytical approaches.

Specialized platforms like Rosalind offer structured problem-solving opportunities to develop specific bioinformatics competencies, functioning as targeted assays for particular analytical skills [24]. Similarly, public data resources like biobanks and expression repositories provide the raw materials for computational experiments, enabling researchers to test hypotheses and develop methods without generating new sequencing data [27]. Together, these tools form a comprehensive toolkit that supports the entire research lifecycle from data acquisition through biological interpretation, with particular importance for drug development professionals validating targets across diverse datasets and populations.

The educational pathway for computational genomics integrates formal academic training, targeted self-study, and practical experimental experience to prepare researchers for contributions to drug development and genomic medicine. University programs from institutions like the University of Washington, Harvard, and Yale provide foundational knowledge and recognized credentials, while curated self-study resources enable flexible skill development in specific technical domains [22] [23] [21]. The experimental protocols and computational tools detailed in this guide offer practical starting points for implementing genomic analyses relevant to target discovery and validation.

Mastering computational genomics requires maintaining this integrated perspective—viewing formal education, self-directed learning, and hands-on practice as complementary components of professional development. The rapidly evolving nature of genomic technologies and analytical approaches necessitates continued learning through conferences, specialized workshops, and engagement with the scientific community [28] [27]. By strategically combining these educational modalities, researchers and drug development professionals can build the interdisciplinary expertise required to advance personalized medicine and address complex biological challenges through computational genomics.

The field of computational genomics represents the intersection of biological science, computer science, and statistics, enabling researchers to extract meaningful information from vast genomic datasets. While sequencing the first human genome required over a decade and $3 billion as recently as 2001, technological advancements have reduced both cost (now under $200 per genome) and processing time to mere hours [29]. This dramatic transformation has made genomic analysis accessible across research and clinical environments, fundamentally changing how we approach biological questions and therapeutic development.

For researchers and drug development professionals entering computational genomics, understanding three fundamental concepts—genome architecture, sequencing technologies, and genetic variation—provides the essential foundation for effective research design and analysis. This guide presents both the biological theory and practical computational methodologies needed to begin impactful work in this rapidly evolving field. The annual Computational Genomics Course offered by Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory emphasizes that proper training in this domain requires not just learning software tools, but developing "a deep, algorithmic understanding of the technologies and methods used to reveal genome function" [12], enabling both effective application of existing methods and development of novel analytical approaches.

Core Biological Concepts

Genome Architecture and Organization

The genome represents the complete set of genetic instructions for an organism, encoded in DNA sequences that are organized into chromosomes. Understanding genome architecture requires moving beyond the outdated single-reference model to contemporary approaches that capture global genetic diversity. The newly developed Human Pangenome Reference addresses historical biases by providing a more inclusive representation of global genetic diversity, significantly enhancing the accuracy of genomic analyses across different populations [30]. This shift is critical for equitable genomic medicine, as it ensures research findings and clinical applications are valid across all populations, not just those historically represented in genetic databases.

Key elements of genome architecture include:

- Protein-coding genes: Sequences that are transcribed into mRNA and ultimately translated into proteins, representing approximately 1-2% of the human genome

- Regulatory elements: Non-coding regions that control when and where genes are expressed, including promoters, enhancers, and silencers

- Non-coding RNA genes: Functional RNA molecules that are not translated into proteins, including microRNAs and long non-coding RNAs

- Repetitive elements: Sequences that occur multiple times throughout the genome, including transposable elements and satellite DNA

- Structural features: Higher-order organization including chromatin loops, topological associating domains, and compartmentalization that influence gene regulation

The integration of multiomics approaches—combining genomics with transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics—provides comprehensive insights into biological systems by revealing the pathways linking genetic variants to phenotypic outcomes [30]. For example, the UK Biobank's epigenomic dataset, which includes 50,000 participants, demonstrates how combining DNA methylation data with genomic sequences enhances disease risk prediction [30].

Sequencing Technologies and Applications

Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technologies have evolved into sophisticated platforms that continue to drive down costs while improving accuracy. The current landscape, often termed NGS 2.0, includes several complementary approaches [30]:

Table 1: Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms and Applications

| Platform | Capability | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq X | Sequences >20,000 whole genomes/year | Large-scale population genomics |

| Ultima Genomics UG 100 with Solaris | Sequences >30,000 whole genomes/year | Cost-effective whole genome sequencing |

| Oxford Nanopore | Real-time portable sequencing | Point-of-care and field-based applications |

These technological advancements have enabled diverse sequencing applications that support both research and clinical goals:

- Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS): Comprehensive analysis of an organism's complete DNA sequence, requiring highly accurate variant callers (e.g., DeepVariant, Strelka2) and assembly tools (e.g., HiFi-ASM) that can handle large genomes and complex structural variations [31]

- Single-Cell RNA-Seq: Analysis of gene expression at individual cell resolution, requiring specialized tools for quality control, normalization, dimensionality reduction (e.g., UMAP, t-SNE), clustering, and differential expression analysis [31]

- Metagenomics: Analysis of genetic material recovered directly from environmental or clinical samples, benefiting from improved taxonomic classification tools (e.g., Kraken, Centrifuge) and assembly methods for complex microbial communities [31]

- Long-read sequencing: Technologies like Nanopore and HiFi sequencing that enable more complete genome assembly and better detection of complex structural variations, requiring specialized algorithms capable of handling longer reads [31]

The choice of sequencing technology depends on research objectives, with considerations including required resolution, throughput, budget constraints, and analytical infrastructure.

Genetic Variation and Functional Interpretation

Genetic variation represents differences in DNA sequences among individuals and populations, serving as the fundamental substrate for evolution and the basis for individual differences in disease susceptibility and treatment response. The accurate identification and interpretation of these variations is a central challenge in computational genomics.

Major types of genetic variation include:

- Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs): Single base pair changes, the most common type of genetic variation

- Insertions and deletions (Indels): Small sequences added or removed from the DNA

- Copy number variations (CNVs): Larger segments of DNA that are duplicated or deleted

- Structural variations (SVs): Large-scale rearrangements including inversions, translocations, and complex combinations

- Short tandem repeats (STRs): Repeated sequences of 2-6 base pairs that exhibit length variation

Variant calling—the process of identifying differences between a sample genome and a reference genome—has been revolutionized by artificial intelligence approaches. Traditional methods often struggled with accuracy, particularly in complex genomic regions, but AI models like DeepVariant have now surpassed conventional tools, achieving greater precision in identifying genetic variations [32]. This improved accuracy is particularly critical for clinical applications where correct variant identification can directly impact diagnosis and treatment decisions.

Functional interpretation of genetic variants relies on increasingly sophisticated computational approaches:

- Variant effect prediction: Algorithms that predict whether a variant affects gene function, protein structure, or regulatory regions

- Pathway analysis: Methods that determine whether variants cluster in specific biological pathways

- Population genetics statistics: Measures that assess variation within and between populations

- Annotation tools: Resources that provide functional context for variants using databases such as Ensembl and NCBI [31]

The integration of AI and machine learning has dramatically improved variant prioritization, accelerating rare disease diagnosis by enabling faster identification of pathogenic mutations [30]. These approaches are increasingly essential for managing the volume of data generated by modern sequencing technologies.

Computational Methods and Analytical Approaches

Analytical Workflows and Platforms

Computational genomics relies on reproducible workflows and specialized platforms that streamline analysis while maintaining scientific rigor. The field has seen significant advancement in workflow automation technologies that ensure reproducible and scalable analysis pipelines [31]. Platforms like Nextflow, Snakemake, and Cromwell have become essential tools, with containerization technologies like Docker and Singularity providing crucial portability and consistency across computing environments [31].

Cloud-based and serverless computing architectures have transformed genomic analysis by removing the need for expensive local computing infrastructure. Major cloud platforms (AWS, GCP, Azure) now offer sophisticated services for NGS data storage, processing, and analysis, with serverless computing further abstracting away infrastructure management to allow researchers to focus on analytical questions rather than computational logistics [31]. This shift has democratized access to computational resources, enabling smaller labs and institutions in underserved regions to participate in large-scale genomic research.

The emerging approach of federated learning addresses both technical and privacy challenges by enabling institutions to collaboratively train machine learning models without transferring sensitive genomic data to a central server [30]. This decentralized machine learning approach brings the code to the data, preserving privacy and regulatory compliance while still allowing models to benefit from diverse datasets—a particularly valuable capability given the sensitive nature of genomic information.

Artificial Intelligence in Genomics

Artificial intelligence has fundamentally transformed genomic analysis, with machine learning and deep learning approaches now achieving accuracy improvements of up to 30% while cutting processing time in half compared to traditional methods [32]. The global NGS data analysis market reflects this transformation—projected to reach USD 4.21 billion by 2030, growing at a compound annual growth rate of 19.93% from 2024 to 2030, largely fueled by AI-based bioinformatics tools [32].

Key applications of AI in genomics include:

- Variant calling: AI models like DeepVariant use convolutional neural networks to distinguish true genetic variations from sequencing artifacts, significantly improving accuracy [30] [32]

- Variant prioritization: Machine learning algorithms accelerate rare disease diagnosis by identifying pathogenic mutations from among thousands of benign variants [30]

- Protein structure prediction: Tools like AlphaFold 3 predict the structure of proteins, DNA, RNA, ligands, and other biomolecules and their interactions [30]

- Drug response modeling: AI systems predict how patients will respond to medications based on their genetic profiles [30]

An especially promising frontier involves applying language models to interpret genetic sequences. As one expert explains: "Large language models could potentially translate nucleic acid sequences to language, thereby unlocking new opportunities to analyze DNA, RNA and downstream amino acid sequences" [32]. This approach treats genetic code as a language to be decoded, potentially identifying patterns and relationships that humans might miss, with profound implications for understanding genetic diseases, drug development, and personalized medicine.

Data Security and Privacy Considerations

As genomic data volumes grow exponentially, so does the focus on data security. Genetic information represents uniquely sensitive data—revealing not just current health status but potential future conditions and even information about family members—demanding protection measures beyond standard data security practices [32].

Leading NGS platforms now implement multiple security layers including:

- Advanced encryption protocols: End-to-end encryption that protects data both during storage and transmission

- Secure cloud storage solutions: Robust security measures configured correctly for genomic data

- Strict access controls: Implementation of the principle of least privilege, where team members can only access specific data needed for their work

- Multi-factor authentication: Requiring users to verify their identity through multiple means before accessing sensitive genomic data

For researchers working with genomic data, several security best practices have emerged as essential in 2025. Data minimization—collecting and storing only the genetic information necessary for specific research goals—reduces risk exposure. Regular security audits help identify and address potential vulnerabilities before they can be exploited. For collaborative projects involving multiple institutions, data sharing agreements should clearly outline security requirements and responsibilities for all parties [32].

Experimental Design and Protocols

Whole Genome Sequencing Analysis

Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) provides the most comprehensive view of an organism's genetic makeup, enabling researchers to detect variants across the entire genome. A robust WGS analysis pipeline requires careful experimental design and multiple analytical steps to ensure accurate results.

Table 2: Core Components of WGS Analysis

| Component | Function | Common Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Quality Control | Assess sequencing data quality | FastQC, MultiQC |

| Read Alignment | Map sequences to reference genome | BWA, Bowtie2, Minimap2 |

| Variant Calling | Identify genetic variants | DeepVariant, Strelka2 |

| Variant Filtering | Remove false positives | VQSR, hard filtering |

| Variant Annotation | Add biological context | SnpEff, VEP |

| Visualization | Explore results visually | IGV, Genome Browser |

The standard workflow for WGS analysis includes:

- Sample Preparation and Sequencing: Extract high-quality DNA, prepare sequencing libraries, and sequence using appropriate NGS platforms based on research needs (e.g., Illumina for short-read, Nanopore for long-read)

- Quality Control: Assess raw sequencing data using FastQC to identify potential issues with base quality, GC content, adapter contamination, or overrepresented sequences

- Read Alignment: Map sequencing reads to a reference genome using aligners optimized for the specific sequencing technology (BWA for short reads, Minimap2 for long reads)

- Post-Alignment Processing: Sort and index alignment files, mark duplicate reads, and perform base quality score recalibration to improve variant discovery

- Variant Calling: Identify SNPs, indels, and structural variants using specialized callers, with DeepVariant using deep learning approaches to achieve superior accuracy

- Variant Filtering: Apply quality filters to remove false positives while retaining true variants, using approaches like Variant Quality Score Recalibration (VQSR)

- Variant Annotation and Prioritization: Add functional annotations using databases like Ensembl and dbSNP, then prioritize variants based on predicted functional impact and association with phenotypes of interest

The primary challenges in WGS analysis include managing the substantial computational resources required, distinguishing true variants from artifacts, and interpreting the clinical or biological significance of identified variants. The emergence of pangenome references has improved variant detection, particularly in regions poorly represented in traditional linear references [30].

Single-Cell RNA Sequencing Analysis

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) enables researchers to profile gene expression at individual cell resolution, revealing cellular heterogeneity that is masked in bulk RNA-seq experiments. This approach has transformed our understanding of complex tissues, development, and disease mechanisms.

The scRNA-seq workflow consists of these key steps:

- Single-Cell Isolation: Separate individual cells using microfluidic platforms (e.g., 10x Genomics Chromium), fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), or other isolation methods

- cDNA Synthesis and Library Preparation: Reverse transcribe RNA from each cell, add cell barcodes and unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), and prepare sequencing libraries

- Sequencing: Sequence libraries using NGS platforms, typically requiring shallower sequencing per cell but across thousands of cells

- Quality Control and Filtering: Remove low-quality cells based on metrics like total counts, number of detected genes, and mitochondrial content

- Normalization and Scaling: Adjust counts to account for technical variability between cells using methods like SCTransform or log-normalization

- Feature Selection: Identify highly variable genes that drive heterogeneity across cells

- Dimensionality Reduction: Project high-dimensional gene expression data into 2-3 dimensions using PCA, UMAP, or t-SNE for visualization and analysis

- Clustering: Identify distinct cell populations using graph-based or centroid-based clustering algorithms

- Cell Type Annotation: Assign cell identities to clusters using marker genes from reference datasets or known cell-type-specific signatures

- Differential Expression Analysis: Identify genes that are differentially expressed between conditions or cell types using methods like MAST or Wilcoxon rank-sum test

Advanced scRNA-seq applications include:

- Trajectory inference: Reconstructing developmental pathways or cellular transition states using algorithms like Monocle3 or PAGA

- RNA velocity: Predicting future cell states by comparing spliced and unspliced mRNA counts

- Cellular interaction analysis: Inferring cell-cell communication networks from ligand-receptor co-expression

- Multi-modal integration: Combining scRNA-seq with other data types like ATAC-seq (assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with sequencing) to profile gene regulation

The Computational Genomics Course offered by the Mayo Clinic & Illinois Alliance covers both basic and clinical applications of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, highlighting their growing importance in both research and clinical diagnostics [33].

Single-cell RNA-seq Analysis Workflow

Variant Calling Methodology

Variant calling represents one of the most fundamental computational genomics tasks, with methodologies varying based on variant type and sequencing technology. The core protocol involves:

Input Requirements:

- Sequence alignment files (BAM/CRAM format) from WGS, whole exome sequencing, or targeted sequencing

- Reference genome sequence (FASTA format) and pre-built index files

- Known variant sites for training machine learning models (VCF format)

Variant Calling Steps:

- Preprocessing: Clean alignment files by removing PCR duplicates, realigning around indels, and recalibrating base quality scores using GATK or similar tools

- Variant Discovery:

- For SNPs and small indels: Use callers like DeepVariant (convolutional neural network-based) or GATK HaplotypeCaller (local de novo assembly-based)

- For structural variants: Use callers like Manta (paired-end and split-read evidence) or Delly (read depth and junction evidence)