Machine Learning vs Statistical Models in Drug Discovery: A Practical Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of machine learning (ML) and traditional statistical models, specifically tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Machine Learning vs Statistical Models in Drug Discovery: A Practical Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of machine learning (ML) and traditional statistical models, specifically tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It explores the foundational philosophies, methodological applications in target identification and clinical trial optimization, and practical challenges like data quality and model interpretability. By synthesizing current evidence and real-world case studies, it offers a validated framework for model selection to enhance efficiency, reduce costs, and accelerate the translation of discoveries into viable therapies.

Core Principles: Understanding the Philosophical Divide Between ML and Statistics

In the evolving landscape of data analysis, a fundamental schism exists between two primary modeling philosophies: one geared towards prediction and the other towards inference and hypothesis testing. This division often, though not exclusively, maps onto the comparison between modern machine learning (ML) models and traditional statistical models [1] [2]. While both approaches use data to build models and share a common mathematical foundation, their core objectives dictate everything from model selection and evaluation to the final interpretation of results [3] [4].

Prediction is concerned with forecasting an outcome or classifying new observations based on patterns learned from historical data [5] [4]. The paramount goal is predictive accuracy on new, unseen data [1]. In contrast, inference aims to understand the underlying data-generating process, quantify the relationships between variables, and test well-defined hypotheses about these relationships [1] [6]. The focus here is on interpretability and understanding the strength and direction of influence that various factors have on the outcome [5]. For researchers and drug development professionals, confusing these purposes can lead to flawed decisions, misguided interventions, and a breakdown in trust with stakeholders [5]. This guide provides a structured comparison to inform the choice between these two critical paradigms.

Conceptual Framework: Objectives and Applications

The choice between a predictive or inferential framework is not a matter of which is universally better, but rather which is more appropriate for the specific question at hand.

The Goal of Prediction

The purpose of prediction is to build a model that can make reliable forecasts for future or unseen data points [5] [4]. The model is treated as a "black box" in the sense that the internal mechanics are less important than the final output's accuracy [1]. For instance, in a clinical setting, a predictive model might be used to forecast a patient's risk of readmission within 30 days based on their medical history and treatment pathway. The clinical team may not need to know exactly which variables drove the prediction; they primarily need to know that the high-risk identification is correct to allocate additional resources [4].

Typical questions answered by prediction:

- What is the predicted sales volume for this drug next quarter? [4]

- Will this customer churn in the next month? [4]

- Is this tissue sample malignant or benign? [7]

The Goal of Inference and Hypothesis Testing

Inference focuses on understanding the 'why' [4]. It involves drawing conclusions about the relationships between variables and the underlying population from which the data were sampled [6]. This approach is inherently hypothesis-driven; a researcher begins with a theory about how variables interact and uses the model to test that hypothesis [1] [5]. In pharmaceutical research, inference would be used to determine whether a new drug treatment has a statistically significant effect on patient outcomes, and to quantify the size of that effect while controlling for confounding variables like age or disease severity [3]. The interpretability of the model is paramount [1].

Typical questions answered by inference:

- What is the effect of a specific gene's expression level on treatment response? [6]

- How much does the drug's efficacy increase for every 5mg increase in dosage? [3]

- Is there a causal relationship between a particular biomarker and disease progression?

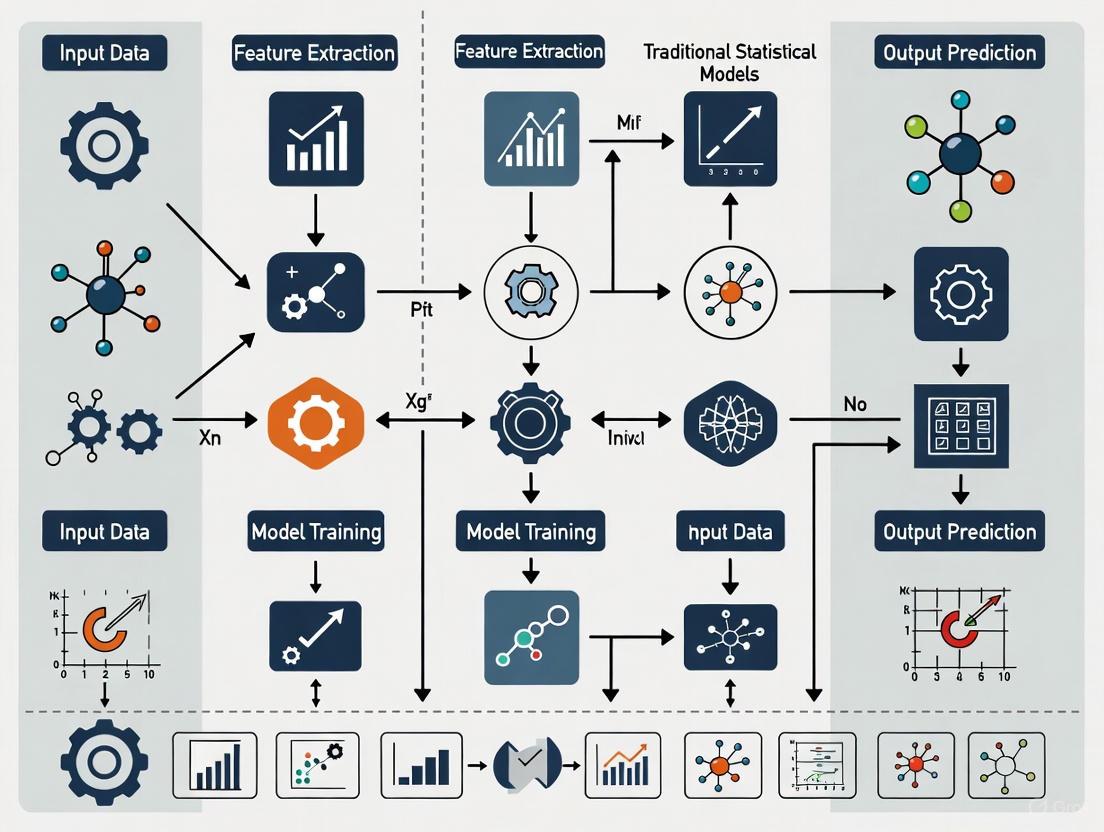

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and distinct focus of each approach.

Comparative Analysis: Performance and Characteristics

The fundamental differences in goals lead to divergent practices in methodology, model complexity, and evaluation. The table below summarizes these key distinctions.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Prediction and Inference

| Feature | Prediction | Inference |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Forecast future outcomes accurately [5] [4] | Understand relationships between variables and test hypotheses [1] [6] |

| Model Approach | Data-driven, algorithmic [1] | Hypothesis-driven, probabilistic [1] [5] |

| Key Question | "What will happen?" | "Why did it happen?" or "What is the effect?" [5] |

| Model Complexity | Often high (e.g., deep neural networks) to capture complex patterns [1] | Typically simpler (e.g., linear models) for interpretability [1] [4] |

| Interpretability | Often low ("black box"); sacrifice interpretability for power [1] | High ("white box"); model must be interpretable [1] [4] |

| Data Requirements | Large datasets for training [1] | Can work with smaller, curated datasets [4] |

Empirical Performance Comparison

Theoretical distinctions are borne out in practical performance across various domains. A systematic review of 56 studies in building performance compared traditional statistical methods with machine learning algorithms, providing robust, cross-domain experimental data [8]. Similarly, research in the medical device industry offers a clear comparison of forecasting accuracy.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Domains

| Domain / Model Type | Specific Models Tested | Key Performance Metric | Result | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building Performance | Linear Regression, Logistic Regression vs. Various ML (RF, SVM, ANN) | Classification & Regression Metrics | ML algorithms performed better in 73% of cases for classification and 64% for regression. | [8] |

| Medical Device Demand Forecasting | SARIMAX, Exponential Smoothing, Linear Regression vs. LSTM (Deep Learning) | Weighted Mean Absolute Percentage Error (wMAPE) | LSTM (DL) was most accurate (wMAPE: 0.3102), outperforming all statistical and other ML models. | [9] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure valid and reproducible results, the experimental design must align with the analytical goal. Below are detailed protocols for both prediction and inference-focused studies.

Protocol for a Prediction Task

Objective: To develop a model that accurately predicts patient readmission risk within 30 days of discharge.

Workflow Description: This protocol begins with data preparation and preprocessing, followed by model training focused on maximizing predictive performance. The process involves splitting data into training and testing sets, then engineering features to improve model accuracy. Researchers select and train multiple machine learning algorithms, tuning their hyperparameters to optimize results. The final stage evaluates model performance on unseen test data using robust metrics, with the best-performing model selected for deployment to generate future predictions.

Protocol for an Inference Task

Objective: To test the hypothesis that a new drug treatment (Drug X) has a significant positive effect on reducing blood pressure, after controlling for patient age, weight, and baseline health.

Workflow Description: This protocol starts with a clearly defined hypothesis and careful study design to establish causality. Researchers collect data through a controlled experiment, such as a randomized controlled trial (RCT), ensuring proper randomization into treatment and control groups. After data cleaning, a statistical model is specified based on the research question, incorporating the treatment variable and key covariates. The core analysis involves fitting the model, checking its underlying assumptions, and interpreting the coefficients, p-values, and confidence intervals to draw conclusions about the hypothesis and effect sizes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Selecting the right tools is critical for executing the experimental protocols effectively. This toolkit details essential solutions, software, and materials for both prediction and inference workflows.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Prediction and Inference Research

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Python (scikit-learn) | Software Library | Provides a unified toolkit for building, training, and evaluating a wide range of ML models. | Core platform for implementing prediction workflows (e.g., Random Forest, SVM). [9] [8] |

R with stats package |

Software Library | Offers comprehensive functions for fitting traditional statistical models like linear and logistic regression. | Core platform for inference tasks, hypothesis testing, and calculating p-values. [3] |

| Structured Query Language (SQL) | Data Language | Extracts and manages structured data from relational databases for analysis. | Extracting patient records or sales history from institutional databases. |

| Jupyter Notebook / RStudio | Development Environment | Provides an interactive computational environment for exploratory data analysis, modeling, and visualization. | The primary workspace for conducting and documenting all stages of analysis. [1] |

| Training/Test Datasets | Data Artifact | A split of the full dataset used to develop models without data leakage and to evaluate genuine predictive performance. | Critical for the prediction protocol to avoid overfitting and validate accuracy. [1] |

| Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) Data | Data Artifact | The gold-standard data collection method where subjects are randomly assigned to groups to establish causality. | The ideal data source for inferential studies aiming to test the effect of a treatment. [5] |

| Cross-Validation (e.g., k-Fold) | Methodological Technique | Resamples the training data to tune model parameters and assess how a model will generalize to an unseen dataset. | Used in prediction tasks for robust hyperparameter tuning and model selection. [1] |

| Diagnostic Plots (e.g., Q-Q, Residuals) | Analytical Tool | Graphical methods used to check if a statistical model's assumptions (e.g., normality of errors) are met. | A crucial step in the inference protocol to validate the reliability of the model's results. [3] |

The distinction between prediction and inference is foundational for researchers and drug development professionals. Machine learning models often excel in prediction tasks, achieving high accuracy by leveraging complex algorithms on large datasets, as evidenced by their superior performance in forecasting demand and building performance [9] [8]. Conversely, traditional statistical models remain indispensable for inference and hypothesis testing, where understanding the specific effect of a variable—such as a drug's dosage—is the primary goal, and model interpretability is non-negotiable [1] [3].

The most effective analytical strategy is not an exclusive choice but an informed one. The decision should be guided by a clear research objective: use predictive modeling to answer "what" will happen, and use inferential statistics to answer "why" it happens or "what is the effect" of a specific change. By aligning your goal with the correct methodology and toolkit, you ensure that your data analysis is both technically sound and scientifically meaningful.

The selection of a predictive modeling approach is a foundational decision in computational drug development, one that fundamentally shapes the trajectory and outcome of research. This choice often presents a dichotomy between models built on parametric foundations—with their strong, a priori assumptions about data structure—and those offering data flexibility—which learn complex patterns directly from the data itself. This divergence is not merely technical but philosophical, representing the broader tension between traditional statistical models, designed for inference and interpretability, and modern machine learning (ML), engineered for predictive accuracy and scalability [1].

Within the high-stakes, resource-intensive domain of drug development, the implications of this choice are profound. Parametric models, such as logistic regression (LR), provide a framework for understanding relationships between variables, testing specific hypotheses, and generating interpretable results with clear confidence intervals [1]. In contrast, nonparametric ML models, including random forests (RF) and deep learning networks, forego rigid assumptions about the underlying functional form, enabling them to capture intricate, nonlinear relationships in large, complex datasets, albeit often at the cost of interpretability [10] [11]. This guide objectively compares the performance of these approaches, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the experimental data and methodological insights needed to inform their modeling strategies.

Conceptual Foundations: Parametric and Nonparametric Models

Defining the Paradigms

At their core, parametric and nonparametric models are distinguished by their relationship to the data's underlying functional form.

Parametric Models summarize data with a set of parameters of a fixed size, which is independent of the number of training examples [10] [11]. This model family operates in two key steps:

- Select a form for the function (e.g., a linear relationship).

- Learn the coefficients for the function from the training data [10]. Examples prevalent in drug research include Logistic Regression, Linear Discriminant Analysis, and Naive Bayes [10] [11]. The primary strength of parametric models is their simplicity and efficiency; they are faster to train, require less data, and yield results that are generally easier to understand and interpret [1] [10]. Their critical limitation is constraint; if the assumed functional form is incorrect, the model will produce a poor fit, limiting its applicability to simpler problems [10].

Nonparametric Models do not make strong assumptions about the form of the mapping function. They are free to learn any functional form from the training data, allowing them to fit a vast number of possible shapes [10] [11]. The term "nonparametric" does not imply an absence of parameters, but rather that the number and nature of parameters are flexible and can change based on the data [11]. Common examples include k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), Decision Trees (e.g., CART), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Random Forests [10] [11]. Their main advantage is flexibility and power; with sufficient data, they can discover complex patterns that elude parametric models, often leading to superior predictive performance [1] [10]. This power comes with trade-offs: they require large amounts of training data, are slower to train, carry a greater risk of overfitting, and are often more difficult to interpret—a significant consideration in regulated environments like drug development [10] [11].

A Visual Guide to Model Selection Logic

The following workflow diagram outlines the key decision points for researchers when choosing between parametric and nonparametric approaches, particularly in the context of drug development.

Experimental Comparisons in Drug Development Contexts

Predicting Clinical Outcomes: ML vs. Logistic Regression

A systematic review and meta-analysis from 2025 directly compared the performance of ML models and conventional LR for predicting outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), a common medical procedure [12]. The study pooled the best-performing ML and LR-based models from 59 included studies to provide a head-to-head comparison across several critical clinical endpoints.

Table 1: Performance Comparison (C-statistic) of ML vs. Logistic Regression for PCI Outcome Prediction [12]

| Clinical Outcome | Machine Learning Models | Logistic Regression Models | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-term Mortality | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.178 |

| Short-term Mortality | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.149 |

| Major Adverse Cardiac Events (MACE) | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.406 |

| Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.373 |

| Bleeding | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.261 |

Experimental Protocol & Methodology [12]:

- Objective: To compare the discrimination performance (using the c-statistic, equivalent to the area under the ROC curve) of ML and deep learning (DL) models against LR-based models for predicting adverse post-PCI outcomes.

- Data Sources: Studies utilizing large-scale clinical registries and electronic health records (EHRs).

- Inclusion Criteria: Studies that provided a c-statistic for both an ML/DL model and an LR model predicting mortality, MACE, in-hospital bleeding, or AKI.

- Analysis: The best-performing model from each study was pooled separately for ML and LR categories. A meta-analysis was then conducted to compare the pooled c-statistics, with a p-value < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

- Risk of Bias: Assessed using the PROBAST and CHARMS checklists, which found a high risk of bias in a majority of the included ML studies (93% for long-term mortality, 70% for short-term mortality).

Interpretation of Findings: The meta-analysis demonstrated that while ML models consistently achieved higher average c-statistics across all five clinical outcomes, none of these differences reached statistical significance [12]. This suggests that in many clinical prediction scenarios, the sophisticated pattern recognition of ML may not yield a decisive performance advantage over well-specified traditional models. The authors note that the high risk of bias and complexity in interpreting ML models may undermine their validity and impact clinical adoption [12].

Forecasting in Medical Device Manufacturing

Research extending beyond clinical prediction into operational aspects of healthcare demonstrates scenarios where nonparametric models demonstrate a clearer advantage. A 2025 study compared traditional statistical, ML, and DL models for demand forecasting of medical devices for a German manufacturer [9].

Table 2: Forecasting Accuracy (wMAPE) for Medical Device Demand [9]

| Model Category | Example Models | Performance (wMAPE) | Relative Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Statistical | SARIMAX, Exponential Smoothing, Linear Regression | Higher wMAPE | Simple, interpretable, less accurate with complex patterns |

| Machine Learning (Nonparametric) | SVR, Random Forest, k-NN | Intermediate wMAPE | Flexible, handles non-linearity, requires preprocessing |

| Deep Learning (Nonparametric) | LSTM, GRU, CONV1D | Lowest wMAPE (e.g., LSTM: 0.3102) | High accuracy, data-hungry, extensive preprocessing needed |

Experimental Protocol & Methodology [9]:

- Objective: To evaluate the effectiveness of various forecasting models in predicting demand for medical devices to improve supply chain efficiency.

- Data: Historical sales records from a German medical device manufacturer.

- Models Evaluated: A wide array, including SARIMAX, Exponential Smoothing, Linear Regression (parametric); Support Vector Regression (SVR), Random Forest (RF), k-Nearest Neighbour Regression (KNR) (nonparametric ML); and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU), Convolution 1D (nonparametric DL).

- Evaluation Metric: Weighted Mean Absolute Percentage Error (wMAPE). A lower wMAPE indicates a more accurate forecast.

- Key Finding: The LSTM model, a nonparametric DL architecture designed for sequential data, achieved the highest predictive accuracy with an average wMAPE of 0.3102, surpassing all other models [9]. This highlights the power of flexible, nonparametric models when dealing with complex, time-dependent data patterns, even with limited datasets.

Handling Missing Data in Clinical Trials

Another critical application in drug development is the handling of missing data in clinical trials. A 2025 simulation study compared parametric and machine-learning multiple imputation (MI) methods for RCTs with missing continuous outcomes [13].

Experimental Protocol & Methodology [13]:

- Simulations: Two simulations were conducted based on RCT settings. The first explored non-linear covariate-outcome relationships with and without covariate-treatment interactions. The second simulation was based on a trial with skewed repeated measures data.

- Compared Methods: Complete Cases analysis, standard parametric MI (MI-norm), MI with predictive mean matching (MI-PMM), and ML-based MI methods including classification and regression trees (MI-CART) and Random Forests (MI-RF).

- Findings: In the absence of complex interactions, parametric MI (MI-norm) performed reliably. However, ML-based MI approaches (MI-RF, MI-CART) could lead to a smaller mean squared error in specific non-linear settings. A critical finding was that in the presence of complex treatment-covariate interactions, performing MI separately by treatment arm—using either parametric or ML methods—provided more reliable inference. The study also cautioned that ML approaches can sometimes provide unreliable inference (bias in effect or standard error) when applying standard combination rules (Rubin's Rules) [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Platforms

The practical application of these models relies on a suite of software tools and platforms that constitute the modern data scientist's laboratory.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Modeling

| Tool Category | Example Platforms & Libraries | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Statistical Analysis | R, SAS, Python (Statsmodels) | Implement traditional parametric models (e.g., LR, ANOVA) for inference and hypothesis testing. [1] |

| Machine Learning Frameworks | Python (Scikit-learn, XGBoost), R (caret) | Provide algorithms for both parametric (e.g., Linear Regression) and nonparametric (e.g., RF, SVM) modeling. [10] [11] |

| Deep Learning Platforms | TensorFlow, PyTorch, Keras | Build and train complex nonparametric models like neural networks (CNNs, RNNs) for tasks such as molecular property prediction. [14] [15] |

| AI-Driven Drug Discovery | AlphaFold, Insilico Medicine Platform, Atomwise | Utilize nonparametric DL for specific tasks like protein structure prediction (AlphaFold) or molecular interaction modeling (Atomwise). [14] |

| Experiment Tracking & MLOps | MLflow, Neptune.ai, Weights & Biases | Manage machine learning experiments, log parameters/metrics, and ensure reproducibility across complex model training runs. [16] |

| AutoML Platforms | Google Cloud AutoML, H2O.ai, Azure AutoML | Democratize ML by automating feature selection, model selection, and hyperparameter tuning, often leveraging nonparametric models. [15] |

The experimental evidence indicates that there is no universal "best" model; the optimal choice is contingent upon the specific research question, data landscape, and regulatory requirements.

Recommend Parametric Models (e.g., Logistic Regression) When: The primary goal is inference and interpretability—for instance, understanding the strength and direction of a specific treatment effect or biomarker [1] [12]. They are also ideal when working with smaller, well-structured datasets or when it is essential to provide confidence intervals and p-values for regulatory submissions [1] [10]. The recent PCI outcome prediction meta-analysis confirms that well-specified parametric models remain highly competitive for many clinical prediction tasks [12].

Recommend Nonparametric Models (e.g., Random Forests, LSTMs) When: The primary goal is maximizing predictive accuracy for complex endpoints, even at the cost of some interpretability [1] [10]. They are essential for leveraging large, complex datasets such as high-dimensional genomic data, medical images, or sequential time-series data from sensors or EHRs [1] [9]. The medical device demand forecasting study showcases their superior performance in capturing intricate, nonlinear patterns [9]. Their application is also growing in foundational drug discovery tasks like molecular design and protein folding, where data flexibility is paramount [14].

The future of modeling in drug development is not a contest for supremacy but a strategic integration of both paradigms. The most effective research pipelines will leverage the interpretability of parametric models for validating hypotheses and communicating results with clinicians and regulators, while simultaneously harnessing the predictive power of nonparametric models to explore complex biological data and generate novel insights. As the field advances, techniques from explainable AI (XAI) and unified ML platforms will be critical for bridging the interpretability gap, ensuring that these powerful, flexible models can be trusted and effectively deployed to accelerate the delivery of new therapies [15] [17].

In the evolving landscape of data analysis, algorithmic learning (encompassing machine learning and statistical learning theory) and mathematical modeling represent two fundamentally distinct approaches for extracting knowledge from data and building predictive systems. While both paradigms aim to create models of real-world phenomena, their philosophical foundations, methodological priorities, and application domains differ significantly. Algorithmic learning focuses primarily on prediction accuracy, using data-driven algorithms to minimize error on unseen data, often with limited concern for underlying mechanisms [18]. In contrast, mathematical modeling emphasizes mechanistic understanding, constructing systems based on first principles and theoretical relationships between variables, with interpretability as a key concern [19].

This distinction is particularly relevant in scientific fields like drug development and healthcare, where the choice between approaches carries significant implications for model transparency, validation requirements, and ultimate utility. The 2025 AI Index Report notes that AI (largely based on algorithmic learning) is increasingly embedded in everyday life, with the FDA approving 223 AI-enabled medical devices in 2023, up from just six in 2015 [20]. Meanwhile, traditional mathematical models continue to provide value in scenarios where causal understanding and interpretability are paramount.

Conceptual Foundation: Core Principles and Distinctions

Philosophical Underpinnings and Objectives

The fundamental distinction between these approaches lies in their core objectives. Algorithmic learning methods are "focused on making predictions as accurate as possible," while traditional statistical models (a subset of mathematical modeling) are "aimed at inferring relationships between variables" [18]. This difference in purpose manifests throughout the model development process, from experimental design to validation and interpretation.

Mathematical modeling typically begins with theoretical understanding, constructing systems based on established scientific principles. These models attempt to represent reality through mathematical relationships that often have direct mechanistic interpretations. In contrast, algorithmic learning is predominantly data-driven, prioritizing performance on specific tasks over interpretability of underlying mechanisms. As noted in research comparing these approaches in medicine, "A crucial difference between human learning and ML is that humans can learn to make general and complex associations from small amounts of data. Machines, in general, require several more samples than humans to acquire the same task, and machines are not capable of common sense" [18].

Methodological Characteristics and Trade-offs

The following table summarizes key methodological differences between these approaches:

Table 1: Fundamental Methodological Distinctions Between Approaches

| Characteristic | Algorithmic Learning | Mathematical Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Prediction accuracy | Parameter inference & mechanistic understanding |

| Data Requirements | Large sample sizes | Can work with smaller samples with strong assumptions |

| Assumptions | Fewer a priori assumptions; data-driven | Strong assumptions about distributions, relationships |

| Interpretability | Often "black box" (especially deep learning) | Typically transparent and interpretable |

| Handling Complexity | Excels with high-dimensional, complex patterns | Struggles with complex interactions without simplification |

| Theoretical Basis | Algorithmic versus statistical guarantees | First principles, mechanistic relationships |

Algorithmic learning offers significant advantages in flexibility and scalability compared to conventional statistical approaches [18]. This makes it particularly deployable for tasks such as diagnosis, classification, and survival predictions where pattern recognition is more valuable than causal inference. However, this flexibility comes at the cost of interpretability, as the results of machine learning "are often difficult to interpret," particularly in complex neural networks [18].

Mathematical modeling, while less flexible, produces "clinician-friendly measures of association, such as odds ratios in the logistic regression model or the hazard ratios in the Cox regression model" that allow researchers to "easily understand the underlying biological mechanisms" [18]. This interpretability is crucial in high-stakes fields like drug development and healthcare, where understanding why a model makes a specific prediction can be as important as the prediction itself.

Experimental Performance Comparison

Quantitative Performance Across Domains

Experimental comparisons between these approaches reveal context-dependent performance advantages. The following table summarizes key findings from empirical studies across multiple domains:

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Across Domains

| Domain | Algorithmic Learning Performance | Mathematical Modeling Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Risk Assessment | CNN accuracy: 93-98% [21] | Not specified | Comparison of CNN vs. RNN in financial risk models |

| Financial Risk Assessment | RNN accuracy: 89-96% [21] | Not specified | Comparison of CNN vs. RNN in financial risk models |

| Perioperative Medicine | Variable performance; context-dependent [22] | Often comparable with better interpretability [22] | Review of 37 studies comparing prediction models |

| Classifier Performance with 20% Overlap | Random Forest: ~0.82 accuracy [23] | K-Nearest Neighbors: ~0.76 accuracy [23] | Multi-class imbalanced data with synthetic overlapping |

| Classifier Performance with 40% Overlap | Random Forest: ~0.74 accuracy [23] | K-Nearest Neighbors: ~0.68 accuracy [23] | Multi-class imbalanced data with synthetic overlapping |

| Healthcare | Superior with complex interactions and high-dimensional data [18] | Superior when variable relationships are well-established [18] | Narrative review of applications in medicine |

In perioperative medicine, a comprehensive review of 37 studies found that "the variable performance of ML models compared to traditional statistical methods underscores a crucial point: the effectiveness of ML is highly context dependent" [22]. While some studies demonstrated clear advantages for algorithmic learning, particularly in complex scenarios, others found "no significant benefit over traditional methods" [22].

Impact of Data Characteristics on Performance

Data characteristics significantly influence the relative performance of these approaches. Algorithmic learning generally excels with high-dimensional data (where the number of features is large) and complex interaction effects, while mathematical modeling performs better when relationships are well-understood and can be explicitly specified.

Research on class overlapping in multi-class imbalanced data shows that "overlapping regions, where various classes are difficult to distinguish, affect the classifier's overall performance in multi-class imbalanced data more than the imbalance itself" [23]. In such complex scenarios, algorithmic learning approaches like Random Forest generally maintain better performance than more traditional distance-based methods like K-Nearest Neighbors as overlapping increases.

The following diagram illustrates the relationship between data characteristics and the suitability of each approach:

Methodological Frameworks and Protocols

Experimental Protocol for Model Comparison

Robust comparison between algorithmic learning and mathematical modeling requires structured experimental protocols. The ModelDiff framework provides a systematic approach for comparing learning algorithms through feature-based analysis [24]. The key steps include:

Datamodel Calculation: Compute linear datamodels for each algorithm, representing how instance-wise predictions depend on individual training examples [24]. These datamodels serve as algorithm-agnostic representations enabling comparison across different approaches.

Residual Analysis: Isolate differences between algorithms by computing residual datamodels that capture directions in training data space that influence one algorithm but not the other: θ(¹\²)ₓ = θ(¹)ₓ - ⟨θ(¹)ₓ, θ̂(²)ₓ⟩θ̂(²)ₓ [24].

Distinguishing Direction Identification: Apply Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to residual datamodels to identify distinguishing training directions - weighted combinations of training examples that generally influence predictions of one algorithm but not the other [24].

Hypothesis Validation: Conduct counterfactual experiments to test whether identified features actually influence model behavior as hypothesized [24].

Addressing Class Overlapping in Comparative Studies

In classification tasks, class overlapping significantly impacts performance differences between approaches. Recent research proposes synthetic generation of controlled overlapping samples to systematically evaluate algorithm robustness [23]. The protocol involves:

Overlap Generation: Implementing algorithms like Majority-class Overlapping Scheme (MOS), All-class Oversampling Scheme (AOS), Random-class Oversampling Scheme (ROS), and AOS using SMOTE to introduce controlled overlapping [23].

Degree Variation: Applying algorithms with different degrees of overlap (10%, 20%, 30%, 40%, 50%) to measure performance degradation [23].

Multi-class Focus: Specifically addressing overlapping in multi-class imbalanced data, where "the increase in the number of classes involved in data overlapping makes the classification more challenging" [23].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this experimental protocol:

Key Algorithms and Modeling Approaches

Researchers should be familiar with core algorithms from both paradigms to select appropriate approaches for specific problems:

Table 3: Essential Algorithms and Modeling Techniques

| Category | Method | Primary Use Cases | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithmic Learning | Random Forest [23] | Classification, regression with imbalanced data | Ensemble method, handles nonlinear relationships |

| Algorithmic Learning | K-Nearest Neighbors [23] | Pattern recognition, similarity-based classification | Instance-based learning, simple interpretation |

| Algorithmic Learning | Support Vector Machines [23] | Binary classification, high-dimensional data | Maximum margin classifier, kernel tricks |

| Algorithmic Learning | Convolutional Neural Networks [21] | Image data, spatial patterns | Parameter sharing, translation invariance |

| Algorithmic Learning | Recurrent Neural Networks [21] | Sequential data, time series | Handles variable-length sequences, temporal patterns |

| Mathematical Modeling | Cox Proportional Hazards [18] | Survival analysis, time-to-event data | Hazard ratios, interpretable parameters |

| Mathematical Modeling | Logistic Regression [18] | Binary outcomes, probability estimation | Odds ratios, clinically interpretable |

| Mathematical Modeling | Linear Regression [25] | Continuous outcomes, relationship modeling | Coefficient interpretation, assumption-sensitive |

| Comparative Frameworks | ModelDiff [24] | Algorithm comparison, feature importance | Identifies distinguishing subpopulations |

| Data Preprocessing | SMOTE [23] | Imbalanced data, class overlapping | Synthetic sample generation, borderlines |

Validation and Comparison Frameworks

Robust validation is essential for both approaches, though the specific concerns differ. For algorithmic learning, the primary challenges include overfitting and generalizability, while mathematical modeling faces issues of assumption violations and misspecification.

The ModelDiff framework enables fine-grained comparison between learning algorithms by tracing model predictions back to specific training examples [24]. This approach helps identify distinguishing subpopulations where algorithms behave differently, enabling more nuanced comparisons beyond aggregate performance metrics.

Sensitivity analysis is particularly crucial for mathematical modeling, as "all model-knowing is conditional on assumptions" [19]. Unfortunately, "most modelling studies don't bother with a sensitivity analysis—or perform a poor one" [19], significantly limiting the reliability of their conclusions.

Applications in Scientific Research and Drug Development

Domain-Specific Implementation Considerations

The choice between algorithmic learning and mathematical modeling depends heavily on the specific research domain and question:

Drug Development and Healthcare: In medicine, "ML could be more suited in highly innovative fields with a huge bulk of data, such as omics, radiodiagnostics, drug development, and personalized treatment" [18]. These domains typically involve high-dimensional data with complex, poorly understood interactions where algorithmic learning's pattern recognition capabilities excel.

However, traditional statistical approaches remain valuable "when there is substantial a priori knowledge on the topic under study" and "the number of observations largely exceeds the number of input variables" [18]. This often occurs in public health research and clinical trials where relationships are better established.

Theoretical Research: Algorithmic Learning Theory (ALT) conferences highlight ongoing theoretical advances, with recent work on bandit problems showing how "structured randomness approaches can be as effective as optimistic approaches in linear bandits" [26]. Such theoretical foundations inform practical implementations across domains.

Integrated Approaches and Future Directions

Rather than treating these approaches as mutually exclusive, researchers increasingly recognize the value of integration. As noted in medical research, "Integration of the two approaches should be preferred over a unidirectional choice of either approach" [18]. Potential integration strategies include:

Model Stacking: Using mathematical models as features within algorithmic learning frameworks to incorporate domain knowledge.

Interpretability Enhancements: Applying model explanation techniques (like feature importance rankings) to black-box algorithms to bridge the interpretability gap [22].

Hybrid Validation: Combining quantitative performance metrics with qualitative, domain-expert evaluation to assess both predictive accuracy and mechanistic plausibility.

Uncertainty Quantification: Implementing comprehensive sensitivity analysis for both approaches to understand how conclusions depend on assumptions and data limitations [19].

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with the 2025 AI Index Report noting that "AI becomes more efficient, affordable and accessible" through "increasingly capable small models" and declining costs [20]. These trends suggest that algorithmic learning will become increasingly prevalent, making thoughtful integration with traditional mathematical modeling approaches even more crucial for scientific progress.

Key Strengths and Inherent Limitations of Each Paradigm

In the evolving landscape of data analysis, the choice between traditional statistical models and machine learning (ML) paradigms is pivotal for researchers and drug development professionals. While statistical methods provide robust, interpretable models for understanding variable relationships, ML algorithms excel at predicting complex, non-linear patterns from large, high-dimensional datasets. Objective performance comparisons across multiple scientific domains, including healthcare and clinical prediction, reveal a nuanced reality: ML models often show marginally higher predictive accuracy, but this advantage is frequently not statistically significant and comes at the cost of interpretability and increased computational complexity [12] [8]. This guide provides a structured comparison of their performance, methodologies, and appropriate applications to inform strategic decisions in scientific research and development.

Conceptual Foundations and Core Objectives

Understanding the fundamental goals of each paradigm is essential for selecting the appropriate analytical tool.

Traditional Statistical Models focus primarily on inference—understanding and quantifying the relationships between variables within a dataset. The core aim is to test a pre-specified hypothesis about the data's structure and to model the underlying relationship between inputs and outputs, often relying on strict assumptions about the data (e.g., normal distribution, independence of variables) [27] [8]. The model's output is typically a parameter that describes a population, and the emphasis is on the interpretability of the model and its parameters.

Machine Learning Models prioritize prediction and classification accuracy. The primary goal is to build an algorithm that learns from data to make accurate predictions on new, unseen data, without necessarily understanding the underlying causal relationships [27]. ML is less reliant on pre-specified assumptions about data structure and is particularly adept at handling large, complex, and unstructured datasets to uncover hidden patterns that might be intractable for traditional methods [27] [8]. This often results in models that are more accurate but function as "black boxes," making it difficult to trace the decision-making process [8].

The following diagram illustrates the distinct workflows and primary focuses of each paradigm.

Performance Comparison Across Scientific Domains

Empirical evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses provides a critical lens for evaluating the real-world performance of these paradigms. The following table summarizes quantitative findings from healthcare and building science, two fields with rigorous data analysis demands.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison (C-statistic/AUC)

| Domain | Outcome Metric | Machine Learning Performance | Traditional Statistical Performance | P-value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthcare (PCI) | Long-term Mortality | 0.84 | 0.79 | 0.178 | [12] |

| Healthcare (PCI) | Short-term Mortality | 0.91 | 0.85 | 0.149 | [12] |

| Healthcare (PCI) | Major Adverse Cardiac Events (MACE) | 0.85 | 0.75 | 0.406 | [12] |

| Healthcare (PCI) | Acute Kidney Injury (AKI) | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.373 | [12] |

| Healthcare (PCI) | Bleeding | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.261 | [12] |

| Building Science | Classification & Regression Tasks | Generally Higher | Generally Lower | Not Specified | [8] |

Analysis of Results: The data consistently shows a trend where ML models achieve higher c-statistics (a measure of discriminative ability, where 1.0 is perfect and 0.5 is random) across various clinical outcomes after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [12]. However, the lack of statistical significance (P > 0.05 for all outcomes) indicates that this observed superiority is not reliable across all contexts. This finding is corroborated by a separate systematic review in clinical medicine which concluded that there is "no significant performance benefit of machine learning over logistic regression for clinical prediction models" [8].

Beyond predictive accuracy, the choice of paradigm involves trade-offs in interpretability, data requirements, and operational overhead. The following table contrasts their key operational characteristics.

Table 2: Paradigm Operational Characteristics & Trade-offs

| Characteristic | Traditional Statistical Models | Machine Learning Models |

|---|---|---|

| Core Strength | Inference, Interpretability, Hypothesis Testing | Prediction, Handling Complex/Unstructured Data |

| Data Handling | Best with structured, smaller datasets [28] | Excels with large, high-dimensional, unstructured data [27] |

| Model Interpretability | High (Transparent, causal relationships) [8] | Low to Very Low ("Black box" problem) [8] |

| Assumptions | Relies on strict assumptions (e.g., normality, linearity) [27] | Fewer inherent assumptions; data-driven [8] |

| Computational Demand | Low to Moderate [8] | High (Requires significant resources and expertise) [8] |

| Risk of Bias in Studies | Lower (Established methodology) | High (e.g., 93% of long-term mortality studies in PCI were high risk) [12] |

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarking

To ensure fair and reproducible comparisons between statistical and ML models, a standardized benchmarking framework is essential. The following workflow, adapted from the "Bahari" framework in building science, provides a generalized protocol suitable for biomedical and pharmaceutical research [8].

Key Considerations for Experimental Design:

- Data Splitting: A rigorous hold-out method, such as splitting data into training (e.g., 70%), validation (e.g., 15%), and test (e.g., 15%) sets, is critical. The validation set is used for model tuning, and the final evaluation is performed on the untouched test set to provide an unbiased estimate of real-world performance [8] [29].

- Performance Metrics: The choice of metric must align with the research goal. Common metrics include:

- Comparative Analysis: The best-performing ML model should be compared against the best-performing traditional statistical model (e.g., logistic regression) from the same study and dataset to ensure a fair comparison [12]. The difference in performance should then be tested for statistical significance, as shown in Table 1.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Predictive Modeling

This section details key "research reagents" — core algorithms and methodologies — that form the essential toolkit for conducting comparative analyses in data-driven research.

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Predictive Modeling Experiments

| Reagent (Algorithm) | Paradigm | Primary Function | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear/Logistic Regression | Statistical | Regression / Classification | Foundation method; highly interpretable; provides effect sizes and p-values [12] [27] |

| LASSO/Ridge Regression | Statistical | Regression / Feature Selection | Extends linear models with regularization to prevent overfitting and handle multicollinearity [8] |

| Support Vector Machines (SVM) | Machine Learning | Classification / Regression | Effective in high-dimensional spaces; versatile through kernel functions [9] |

| Random Forest | Machine Learning | Classification / Regression | Ensemble method; robust to outliers; provides feature importance scores [9] |

| Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) | Machine Learning (Deep Learning) | Regression / Time-Series | Excels at learning long-term dependencies in sequential data; high accuracy but complex [9] |

| Gated Recurrent Unit (GRU) | Machine Learning (Deep Learning) | Regression / Time-Series | Similar to LSTM but often more computationally efficient [9] |

The evidence demonstrates that there is no universal "best" paradigm. The choice between traditional statistics and machine learning must be guided by the specific research objective.

Use Traditional Statistical Models when your goal is inference: explaining relationships between variables, testing a scientific hypothesis, requiring model interpretability for regulatory approval or clinical understanding, or working with smaller, structured datasets [27] [8]. The marginal predictive gains from ML in these scenarios often do not justify the loss of transparency and increased complexity [12].

Use Machine Learning Models when your primary goal is maximizing predictive accuracy for complex problems, particularly with large, unstructured datasets (e.g., medical images, genomic sequences, sensor data) where underlying relationships are likely non-linear and not well understood [27] [8] [9]. ML is the preferred tool when prediction is paramount and interpretability is secondary.

A hybrid approach is often the most powerful strategy. This involves using statistical models to understand core relationships and validate hypotheses, while employing ML models to enhance predictive power and uncover novel patterns in complex data. By understanding the inherent strengths and limitations of each paradigm, researchers and drug development professionals can make informed, strategic decisions to advance their scientific objectives.

From Theory to Therapy: Applying ML and Statistical Models in Drug Development

The process of identifying druggable targets is undergoing a profound transformation, moving from traditional single-omics approaches to sophisticated multi-omics integration powered by artificial intelligence (AI) and network analysis. This shift is critical given that approximately 90% of drug candidates fail in preclinical or clinical trials, often due to inadequate target validation [30]. Traditional statistical models, while reliable for analyzing individual data types like genomics or transcriptomics in isolation, struggle to capture the complex interactions between multiple biological layers that drive disease phenotypes. In contrast, AI-driven network approaches can synthesize diverse omics data—including genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics—within the context of biological networks, revealing emergent properties that remain invisible to conventional methods [31].

The integration of multi-omics data with network biology has led to the realization that diseases are rarely the result of single molecular defects but rather emerge from perturbations in complex biological networks [31]. This understanding aligns with the observed complementarity of different omics data; for instance, combining single-cell transcriptomics with metabolomics has revealed how metabolic reprogramming drives cancer metastasis [31]. Within this new paradigm, AI and machine learning act as powerful engines for pattern recognition, capable of identifying subtle, multi-factorial signatures of disease susceptibility within these integrated networks, thereby pinpointing targets with higher therapeutic potential and lower likelihood of failure in later stages.

Methodological Framework: Classifying Integration Approaches

Network-based multi-omics integration methods represent a rapidly evolving field that can be systematically categorized into four primary approaches based on their underlying algorithmic principles and applications in drug discovery [31]. The following table summarizes these core methodologies:

Table 1: Classification of Network-Based Multi-Omics Integration Methods

| Method Category | Algorithmic Principle | Primary Applications in Drug Discovery | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Network Propagation/Diffusion | Spreading information from known disease-associated nodes through biological networks | Target prioritization, disease module identification | Robust to noise, incorporates network topology |

| Similarity-Based Approaches | Measuring functional similarity between molecules across omics layers | Drug repurposing, side-effect prediction | Intuitive, works with heterogeneous data types |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Learning node embeddings through neural network architectures on graphs | Drug response prediction, polypharmacology forecasting | High predictive accuracy, automatic feature learning |

| Network Inference Models | Reconstructing causal relationships from correlational data | Causal target identification, mechanism of action elucidation | Provides directional relationships, mechanistic insights |

These methodologies differ significantly in their computational requirements, data needs, and output interpretations. Network propagation methods, for instance, excel at identifying novel disease-associated genes by simulating the flow of information through protein-protein interaction networks, starting from known disease genes [31]. Similarity-based approaches construct heterogeneous networks where different node types represent various biological entities (genes, drugs, diseases) and use similarity measures to predict new associations. Graph Neural Networks represent the most advanced category, leveraging deep learning to automatically learn informative representations of nodes and edges within biological networks, thereby enabling highly accurate predictions of drug-target interactions and drug responses [31].

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual workflow and relationships between these different methodological approaches:

Experimental Protocols and Performance Benchmarks

Standardized Evaluation Frameworks

Rigorous evaluation of AI-driven target identification methods requires standardized benchmarks and performance metrics. Independent evaluations, such as the 2025 synthetic data benchmark by AIMultiple, have established rigorous testing protocols utilizing holdout datasets comprising 70,000 samples with both numerical and categorical features [32]. In this benchmark, each generator was trained on 35,000 samples and evaluated against the remaining 35,000 to assess their ability to replicate real-world data characteristics. Performance was assessed across three key statistical metrics: Correlation Distance (Δ) for preserving relationships between numerical features, Kolmogorov-Smirnov Distance (K) for evaluating similarity of numerical feature distributions, and Total Variation Distance (TVD) for measuring accuracy of categorical feature distributions [32].

The "lab in a loop" approach represents another innovative experimental framework that integrates wet and dry lab experimentation. In this paradigm, data from the lab and clinic are used to train AI models and algorithms, which then generate predictions on drug targets and therapeutic molecules [30]. These predictions are experimentally tested in the lab, generating new data that subsequently retrains the models to improve accuracy. This iterative process streamlines the traditional trial-and-error approach for novel therapies and progressively enhances model performance across all research programs [30].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The performance advantage of AI and network-based approaches over traditional methods becomes evident when examining quantitative benchmarks across key drug discovery applications:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of AI vs. Traditional Methods in Drug Discovery

| Application Area | Traditional Methods | AI/Network Approaches | Performance Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | Literature mining, expression analysis | Multi-omics network propagation | 20-30% higher precision in predicting validated targets [31] |

| Drug Response Prediction | Statistical regression, clustering | Graph neural networks on PPI networks | 15-25% improvement in accuracy across cancer types [31] |

| Drug Repurposing | Manual literature review, signature matching | Heterogeneous network similarity learning | Identifies 3-5x more viable repurposing candidates [31] |

| Clinical Trial Success | ~10% industry average | AI-prioritized targets in development | Potential to reduce failure rates by 30-40% [33] [30] |

Beyond these specific applications, companies adopting AI-driven decision-making have reported significant operational benefits, including an average increase of 10% in revenue and a 15% reduction in costs [34]. In the pharmaceutical context, these efficiencies translate to accelerated development timelines and improved resource allocation across the drug discovery pipeline.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Implementing AI-driven multi-omics target identification requires specialized computational tools and biological resources. The following table details essential components of the research infrastructure:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for AI-Driven Target Identification

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Networks | Protein-protein interaction (PPI) networks, Gene regulatory networks (GRNs), Drug-target interaction (DTI) networks | Provide organizational framework for data integration and biological context for predictions [31] |

| Omics Data Platforms | TCGA, GDSC, CCLE, DepMap | Supply standardized, annotated multi-omics datasets for model training and validation [31] |

| AI/ML Libraries | PyTorch Geometric, Deep Graph Library, TensorFlow | Provide implementations of graph neural networks and other network-based learning algorithms [31] |

| Synthetic Data Generators | YData, Mostly AI, Gretel, Synthetic Data Vault (SDV) | Generate high-fidelity synthetic data for method development and privacy preservation [32] |

| Validation Assays | CRISPR screens, high-throughput target engagement assays | Experimentally confirm computational predictions in biological systems [30] |

The integration of these resources enables the implementation of advanced computational strategies such as Genentech's "lab in a loop" approach, where proprietary ML algorithms are enhanced using accelerated computing and software, ultimately speeding up the drug development process and improving the success rate of research and development [30]. These collaborations between pharmaceutical companies and technology partners highlight the interdisciplinary nature of modern target identification.

Implementation Workflow: From Data to Discoveries

The process of implementing AI and network analysis for target identification follows a structured workflow that transforms raw multi-omics data into high-confidence candidate targets. The following diagram illustrates this multi-stage process:

Workflow Stage Description

Stage 1: Multi-Omics Data Collection - Diverse molecular profiling data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) are collected from relevant biological samples, often from public repositories like TCGA or generated in-house [31].

Stage 2: Biological Network Construction - Context-appropriate biological networks are assembled from databases or inferred from the data itself. Protein-protein interaction networks, gene regulatory networks, and metabolic networks provide the scaffolding for data integration [31].

Stage 3: Multi-Omics Data Integration - The various omics datasets are mapped onto their corresponding nodes in the biological networks, creating a multi-layered network representation that captures interactions across biological scales [31].

Stage 4: AI/Network Analysis - Computational algorithms from the four method categories (Table 1) are applied to the integrated network to identify disease modules, predict candidate targets, and prioritize interventions [31].

Stage 5: Target Prediction & Prioritization - The analytical results are synthesized to generate ranked lists of candidate targets based on their network properties, predicted efficacy, and potential side effects [31].

Stage 6: Experimental Validation - Top-ranking candidates are tested in biological systems using CRISPR screens, target engagement assays, or other relevant experimental approaches to confirm computational predictions [30].

This workflow embodies the iterative "lab in a loop" paradigm, where validation results feed back into model refinement, creating a continuous cycle of improvement that enhances the accuracy of future predictions [30].

The integration of AI and network analysis for mining multi-omics data represents a fundamental shift in target identification strategy, moving beyond the limitations of traditional statistical models to embrace the complexity of biological systems. By leveraging network biology as an integrative framework and AI as a pattern recognition engine, this approach enables researchers to identify therapeutic targets that reflect the multi-factorial nature of disease. The quantitative performance advantages demonstrated across multiple applications—from target identification to drug repurposing—highlight the transformative potential of these methods to increase productivity and reduce failure rates in drug discovery.

Despite significant progress, challenges remain in computational scalability, data integration, and biological interpretation [31]. Future developments will likely focus on incorporating temporal and spatial dynamics, improving model interpretability, and establishing standardized evaluation frameworks. As these methodologies mature and more comprehensive multi-omics datasets become available, AI-driven network approaches will become increasingly central to target identification, potentially extending their impact to personalized medicine through the analysis of individual patient multi-omics profiles. The convergence of biological network theory, multi-omics technologies, and artificial intelligence is creating a new paradigm for understanding and treating disease, with the potential to significantly accelerate the delivery of innovative therapies to patients.

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has rapidly evolved from a theoretical promise to a tangible force driving a paradigm shift in drug discovery, replacing labor-intensive, human-driven workflows with AI-powered discovery engines capable of compressing timelines and expanding chemical search spaces [35]. This transition marks a fundamental departure from traditional approaches long reliant on cumbersome trial-and-error methods, instead leveraging machine learning (ML) and generative models to accelerate tasks across the entire drug development pipeline [35]. By seamlessly integrating data, computational power, and algorithms, AI enhances the efficiency, accuracy, and success rates of pharmaceutical research while shortening development timelines and reducing costs [33]. The growth in AI-derived drug candidates has been exponential, with over 75 AI-derived molecules reaching clinical stages by the end of 2024—a remarkable leap from essentially zero AI-designed drugs in human testing at the start of 2020 [35]. This comprehensive guide objectively compares the performance of leading AI-powered platforms and methodologies against traditional approaches in de novo molecular design and virtual screening, providing researchers with experimental data and protocols to inform their discovery workflows.

Performance Comparison: AI Platforms vs. Traditional Methods

Clinical Pipeline Progress and Efficiency Metrics

Table 1: Clinical-Stage AI Drug Discovery Platforms (Data as of 2024-2025)

| Company/Platform | Key AI Technology | Therapeutic Areas | Clinical Candidates | Reported Efficiency Gains | Clinical Progress |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exscientia | Generative AI, Centaur Chemist | Oncology, Immunology | 8+ candidates designed | ~70% faster design cycles; 10x fewer compounds synthesized [35] | Multiple Phase I/II trials; Pipeline prioritized post-merger [35] |

| Insilico Medicine | Generative AI, Target Identification | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, Oncology | IPF drug: target to Phase I in 18 months [35] [36] | Traditional timeline: 3-6 years compressed to 18 months [36] | Phase I; Novel QPCTL inhibitors for oncology [36] |

| Recursion | Phenomics, ML | Oncology, Rare diseases | Multiple candidates | Combined data generation with AI analysis [35] | Phase I/II trials; Merged with Exscientia in 2024 [35] |

| BenevolentAI | Knowledge Graphs, ML | Glioblastoma, Immunology | Novel targets identified | AI-predicted novel targets in glioblastoma [36] | Target discovery/validation stage [35] [36] |

| Schrödinger | Physics-based Simulations, ML | Diverse portfolio | Multiple candidates | Physics-based platform for molecular design [35] | Various clinical stages [35] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Benchmarks of AI vs. Traditional Discovery

| Performance Metric | Traditional Drug Discovery | AI-Accelerated Discovery | Evidence & Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Discovery Timeline | 3-6 years | 18-24 months | Insilico Medicine: 18 months from target to Phase I [35] [36] |

| Compounds Synthesized | Thousands | Hundreds | Exscientia: 136 compounds for CDK7 inhibitor candidate vs. thousands typically [35] |

| Design Cycle Efficiency | Baseline | ~70% faster | Exscientia: algorithmic design cycles substantially faster [35] |

| Clinical Entry Rate | Low throughput | >75 AI-derived molecules in clinical trials by end of 2024 [35] | From zero in 2020 to surge in past 3 years [35] |

| Virtual Screening Throughput | Weeks to months for million-compound libraries | Days for billion-compound libraries | OpenVS: 7 days for multi-billion compound libraries [37] |

Virtual Screening Performance Benchmarks

Table 3: Virtual Screening Method Performance on Standard Benchmarks

| Screening Method | Technology Type | CASF2016 Docking Power (RMSD ≤ 2Å) | Top 1% Enrichment Factor (EF1%) | Success Rate (Top 1%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RosettaGenFF-VS | Physics-based AI | Leading performance [37] | 16.72 [37] | Superior to other methods [37] |

| Other Physics-Based Methods | Traditional physics-based | Lower performance | 11.9 (second best) [37] | Lower success rates [37] |

| Deep Learning Methods | AI-based | Better for blind docking | Varies | Less generalizable to unseen complexes [37] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Frameworks

De Novo Molecular Generation Evaluation Protocol

Objective: To rigorously evaluate 3D molecular generative models using chemically accurate benchmarks, addressing critical flaws in existing evaluation protocols [38].

Background: The GEOM-drugs dataset serves as a foundational benchmark for developing 3D molecular generative models. However, current evaluation protocols suffer from critical flaws including incorrect valency definitions, bugs in bond order calculations, and reliance on force fields inconsistent with reference data [38].

Methodology:

- Data Preprocessing: Implement corrected data preprocessing scripts to exclude molecules where GFN2-xTB calculations fractured the original molecule

- Valency Calculation: Fix the aromatic bond valency computation bug where contributions were incorrectly rounded to 1 instead of the proper value of 1.5

- Lookup Table Construction: Create a chemically accurate valency lookup table derived from the refined dataset, removing chemically implausible entries

- Energy Evaluation: Implement GFN2-xTB-based geometry and energy benchmarks for chemically interpretable assessment

- Model Retraining: Retrain leading models (EQGAT-Diff, Megalodon, SemlaFlow, FlowMol) under the corrected framework [38]

Validation Metrics:

- Molecule Stability: Fraction of molecules where all atoms have valid valencies using corrected calculation

- Reconstruction Accuracy: Ability to accurately generate molecular structures

- Chemical Validity: Adherence to chemical rules and constraints

- Energy-Based Assessment: Evaluation of generated molecular 3D geometries using GFN2-xTB

Results Interpretation: The original flawed implementations significantly inflated stability scores—for example, originally reported stability of 0.935±0.007 for EQGAT dropped to 0.451±0.006 when using correct aromatic bond valuation before recovering to 0.899±0.007 with the comprehensive corrected framework [38].

AI-Accelerated Virtual Screening Protocol

Objective: To efficiently screen multi-billion compound libraries using AI-accelerated platforms while maintaining accuracy [37].

Platform Configuration: OpenVS platform with RosettaVS protocol, integrating:

- Virtual Screening Express (VSX): Rapid initial screening mode

- Virtual Screening High-Precision (VSH): Accurate method for final ranking with full receptor flexibility

- Active Learning: Target-specific neural network trained during docking computations to triage promising compounds [37]

Experimental Workflow:

- Target Preparation: Protein structure preparation and binding site definition

- Library Curation: Multi-billion compound library preprocessing and filtering

- Active Learning Phase: Iterative compound selection based on predicted binding affinity

- VSX Screening: High-speed docking of selected compounds

- VSH Refinement: High-precision docking of top hits from VSX

- Hit Validation: Experimental validation through binding assays and X-ray crystallography

Performance Validation: Using the DUD dataset (40 pharmaceutical-relevant targets with over 100,000 small molecules), evaluate using:

- Area Under Curve (AUC) of receiver operating characteristic (ROC)

- ROC Enrichment: Early recognition capability

- Experimental Confirmation: X-ray crystallographic validation of predicted docking poses [37]

Case Study Results: For targets KLHDC2 and NaV1.7, screening of multi-billion compound libraries completed in less than seven days using 3000 CPUs and one GPU per target, discovering hit compounds with 14% and 44% hit rates respectively, all with single-digit micromolar binding affinities [37].

Visualization of AI-Accelerated Drug Discovery Workflows

AI vs Traditional Drug Discovery Timeline

AI-Accelerated Virtual Screening Platform

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for AI-Driven Drug Discovery

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| GEOM-drugs Dataset | Benchmark Dataset | Large-scale high-accuracy molecular conformations for training and evaluation [38] | 3D molecular generative model benchmarking |

| GFN2-xTB | Computational Method | Fast quantum chemical calculation for geometry and energy evaluation [38] | Energy-based assessment of generated molecules |

| RosettaGenFF-VS | Force Field | Physics-based scoring for binding pose and affinity prediction [37] | Virtual screening with receptor flexibility |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Chemical structure curation, manipulation, and analysis [38] | Molecular preprocessing and valency calculation |

| OpenVS Platform | Screening Infrastructure | Open-source AI-accelerated virtual screening with active learning [37] | Billion-compound library screening |

| DUD Dataset | Benchmark Dataset | 40 pharmaceutical targets with >100,000 small molecules for validation [37] | Virtual screening performance assessment |

| CASF2016 Benchmark | Evaluation Framework | 285 diverse protein-ligand complexes for scoring function assessment [37] | Docking power and screening power tests |

Critical Analysis: Machine Learning vs. Traditional Models in Practice

The Data Quality Imperative

A profound challenge in applying machine learning to drug discovery lies in what Eric Ma of Moderna identifies as the "hidden crisis in historical data" [39]. Much historical assay data rests on shaky foundations due to experimental drift—changes in operators, machines, and software over time—without proper metadata tracking. This creates a fundamental limitation for ML models trained on such data, as they're built on statistically unstable ground [39]. The solution requires "statistical discipline in statistical systems"—a systemic approach to tracking all experimental parameters and workflow orchestration, not just individual statistical expertise [39].

The Economic Paradox of ML Implementation

The economics of machine learning present a catch-22 scenario: supervised ML models require substantial data for accuracy, but if assays are expensive, generating sufficient data is prohibitive. Conversely, if assays are cheap enough to generate massive datasets, the need for predictive models diminishes as brute-force screening becomes feasible [39]. This leaves a narrow sweet spot where ML provides genuine value: expensive assays with available historical data, or scenarios requiring sophisticated uncertainty quantification with small datasets [39].

Performance Validation Beyond Benchmarks

While AI platforms demonstrate impressive benchmark performance, the ultimate validation requires clinical success. Notably, despite accelerated progress into clinical stages, no AI-discovered drug has received full regulatory approval yet, with most programs remaining in early-stage trials [35]. This raises the critical question of whether AI is truly delivering better success rates or just faster failures [35]. Companies like Exscientia have undergone strategic pipeline prioritization, narrowing focus to lead programs while discontinuing others, indicating the ongoing refinement of AI-driven discovery approaches [35].

Hybrid Approaches: Integrating Physics and AI

The most promising developments emerge from integrating physics-based methods with AI. RosettaVS combines physics-based force fields with active learning for billion-compound screening [37], while companies like Schrödinger leverage physics-based simulations enhanced by ML [35]. This hybrid approach addresses limitations of pure deep learning methods, which, though faster, are less generalizable to unseen complexes and often better suited for blind docking scenarios where binding sites are unknown [37].

The integration of AI into molecular design and virtual screening represents a fundamental transformation in pharmaceutical research, demonstrating measurable advantages in speed and efficiency over traditional methods. The experimental data and protocols presented in this comparison guide provide researchers with validated frameworks for implementing these technologies, from chemically accurate generative model evaluation to AI-accelerated screening of ultra-large libraries. As the field progresses beyond accelerated compound identification to demonstrating improved clinical success rates, the fusion of biological expertise with computational power—coupled with rigorous validation and standardized benchmarking—will determine the full realization of AI's potential to deliver safer, more effective therapeutics to patients.

The biopharmaceutical industry faces unprecedented challenges in clinical trial delivery, with recruitment delays affecting 80% of studies and cumulative expenditure on Alzheimer's disease research alone estimated at $42.5 billion since 1995 [40]. Traditional statistical methods, while reliable and interpretable, often struggle to capture the complex, nonlinear relationships in large-scale healthcare data [22] [41]. Machine learning (ML) emerges as a transformative approach, offering the potential to enhance predictive accuracy and operational efficiency throughout the clinical trial lifecycle. This comparison guide objectively examines the performance of ML methodologies against traditional statistical models specifically for patient recruitment and stratification—two critical domains that significantly impact trial success, costs, and timelines.

Performance Comparison: ML vs. Traditional Methods

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Table 1: Overall Performance Metrics of ML in Clinical Trials

| Performance Area | Metric | ML Performance | Traditional Method Benchmark |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Recruitment | Enrollment Rate Improvement | 65% improvement [42] | Baseline (Not specified) |

| Trial Efficiency | Timeline Acceleration | 30-50% acceleration [42] | Baseline (Not specified) |

| Cost Management | Cost Reduction | Up to 40% reduction [42] | Baseline (Not specified) |

| Outcome Prediction | Accuracy in Forecasting | 85% accuracy [42] | Varies by context |

| Risk Stratification | Concordance Index (C-index) | 0.878 (Random Survival Forests for Alzheimer's progression) [43] | Lower than ML (Context-dependent) |

Patient Recruitment and Enrollment

AI-powered recruitment tools have demonstrated a 65% improvement in enrollment rates [42]. These systems leverage natural language processing (NLP) and data mining to analyze diverse sources such as electronic health records (EHRs) and medical literature, significantly improving patient-trial matching [44]. For instance, tools like the Clinical Trial Knowledge Base use scalable methods to summarize and standardize free-text eligibility criteria from over 350,000 trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov [44]. A scoping review of 51 studies confirmed that applying AI to recruitment generates positive outcomes including increased efficiency, cost savings, improved accuracy, and enhanced patient satisfaction [44].

Patient Stratification and Outcome Prediction