Mastering Molecular Dynamics: A Practical Guide to Boltzmann & Gibbs Ensemble Theory for Drug Discovery

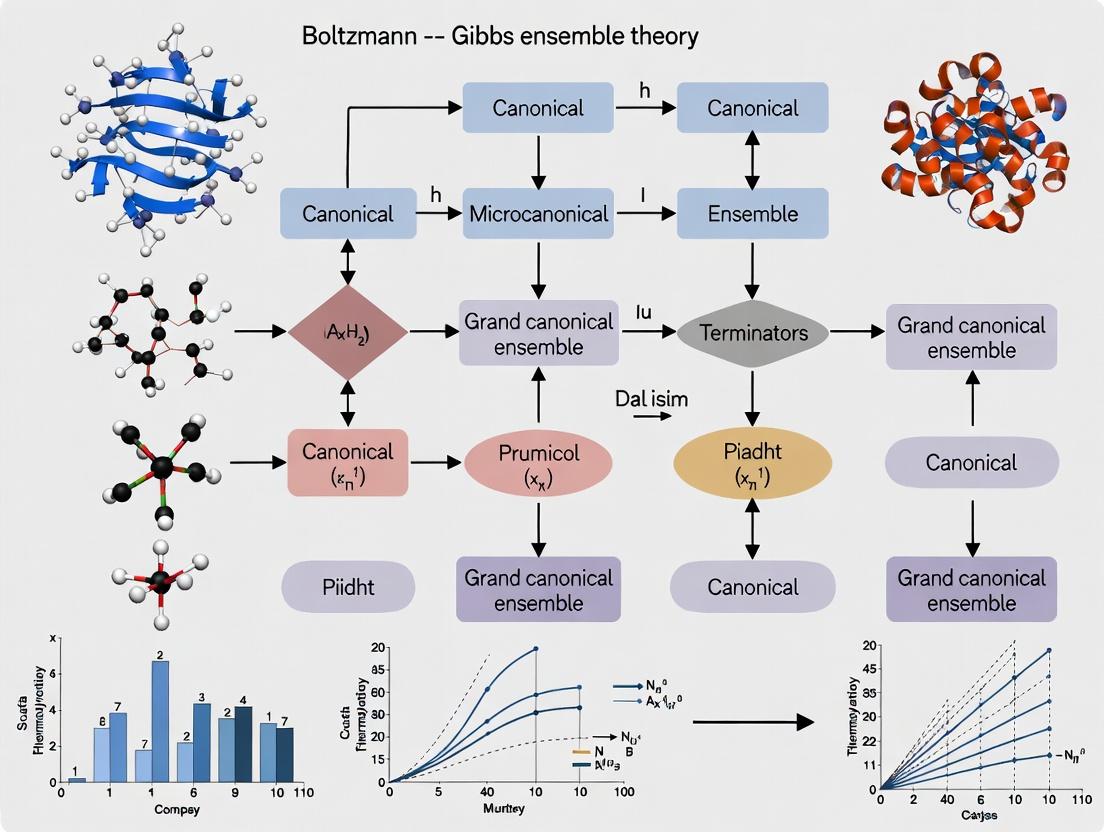

This comprehensive guide explores the foundational principles and modern applications of Boltzmann and Gibbs ensemble theory in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations.

Mastering Molecular Dynamics: A Practical Guide to Boltzmann & Gibbs Ensemble Theory for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This comprehensive guide explores the foundational principles and modern applications of Boltzmann and Gibbs ensemble theory in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it progresses from core statistical mechanics concepts to practical implementation of NVE, NVT, NPT, and μVT ensembles. The article provides actionable methodologies for simulating biologically relevant systems, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, and offers frameworks for validating and comparing ensemble choices. By bridging theoretical rigor with computational practice, this guide empowers scientists to design robust simulations, enhance sampling efficiency, and derive thermodynamically meaningful insights for accelerating biomedical research.

From Microscopic States to Macroscopic Properties: The Statistical Mechanics Bedrock of MD

1. Introduction and Thesis Context Modern molecular dynamics (MD) research is fundamentally an exercise in applied statistical mechanics. The core thesis framing contemporary work is that Boltzmann’s microscopic statistical interpretations and Gibbs’s ensemble formalism provide the complete conceptual and mathematical framework for deriving macroscopic thermodynamic observables from atomistic simulations. This whitepaper details their foundational theories, the quantitative bridge they form between microstates and macrostates, and their explicit implementation in current MD-based drug discovery.

2. Foundational Theories: A Comparative Analysis

2.1 Ludwig Boltzmann's Statistical Interpretation Boltzmann’s key insight was linking entropy (S), a macroscopic property, to the number of microscopic configurations (W) corresponding to a macrostate: S = k_B ln W. This principle underpins the analysis of MD trajectories, where entropy calculations involve counting visited states or approximating phase space volumes.

2.2 J. Willard Gibbs's Ensemble Theory Gibbs systematized statistical mechanics by introducing the concept of ensembles—imagined collections of all possible microstates consistent with a set of macroscopic constraints. The three primary ensembles are cornerstones of MD simulation design.

Table 1: Core Statistical Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics

| Ensemble | Fixed Quantities | Connecting Formula | Primary MD Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical (NVE) | Number (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | - | Studying isolated systems; fundamental dynamics. |

| Canonical (NVT) | Number (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Helmholtz Free Energy: F = E - TS | Simulating systems at experimental temperature. |

| Isothermal-Isobaric (NPT) | Number (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | Gibbs Free Energy: G = H - TS | Simulating at experimental T & P; density calculation. |

| Grand Canonical (μVT) | Chemical Potential (μ), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Landau Potential: Ω = -PV | Studying adsorption, binding, and open systems. |

3. Experimental Protocols: From Theory to Simulation

3.1 Protocol for Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) - A Gibbsian Application Objective: Calculate the relative binding free energy (ΔΔG) of two ligand analogs to a protein target, a critical task in lead optimization. Theoretical Basis: The process is governed by the Gibbs free energy difference between states. Using a canonical (NVT) ensemble, the free energy difference is computed via thermodynamic perturbation or integration. Methodology:

- System Preparation: Solvate the protein-ligand complex in an explicit water box. Add ions to neutralize charge.

- Alchemical Pathway Definition: Define a hybrid molecule (ligand A → ligand B) via a coupling parameter λ (0 → 1). At λ=0, the system interacts with ligand A; at λ=1, with ligand B.

- Equilibration: Run NVT and NPT simulations to equilibrate temperature (e.g., 310 K using a Nosé–Hoover thermostat) and pressure (1 bar using a Parrinello–Rahman barostat).

- λ-Windows Simulation: Perform parallel MD simulations at discrete, overlapping λ values (e.g., 0.0, 0.1, 0.2, ..., 1.0). Each window is simulated for sufficient time (e.g., 5-10 ns) to sample the perturbed Hamiltonian.

- Analysis (MBAR/WHAM): Use the Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR) or Weighted Histogram Analysis Method (WHAM) to combine data from all windows, yielding a continuous free energy profile and the final ΔΔG.

Diagram 1: Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Protocol Workflow

3.2 Protocol for Entropy Calculation using the Quasi-Harmonic Approximation Objective: Decompose the Gibbs free energy of binding into enthalpic and entropic components. Theoretical Basis: This protocol applies Boltzmann's entropy formula by approximating the configurational entropy from the covariance matrix of atomic positional fluctuations. Methodology:

- Trajectory Production: Run extensive NPT simulations of the protein-ligand complex, the free protein, and the free ligand.

- Coordinate Alignment & Mass-Weighting: Align all trajectory frames to a reference structure to remove rotational/translational motion. Optionally apply mass-weighting.

- Covariance Matrix Construction: Calculate the 3N x 3N covariance matrix of atomic positional fluctuations for each system.

- Diagonalization: Diagonalize the covariance matrix to obtain its eigenvalues (σ_i).

- Entropy Computation: Apply the quasi-harmonic formula: S_qh = (k_B/2) ln[det(1 + (k_B T / ħ^2) Σ)], where Σ is the covariance matrix, or use the eigenvalue relation: S_config ≈ k_B Σ_i [ (1/2) + ln(√(2πe σ_i)) ].

- Decomposition: The entropic contribution to binding is: TΔSbind = T(Scomplex - Sprotein - Sligand).

Diagram 2: Quasi-Harmonic Entropy Calculation Workflow

4. The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents & Software Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Toolkit for Ensemble-Based MD

| Item / Solution | Type | Function in Ensemble Simulations |

|---|---|---|

| Explicit Solvent (e.g., TIP3P, TIP4P water) | Molecular Model | Provides a realistic dielectric environment; crucial for NPT ensemble density. |

| Thermostat (e.g., Nosé–Hoover, Langevin) | Algorithm | Regulates kinetic energy to maintain target temperature (T) in NVT/NPT ensembles. |

| Barostat (e.g., Parrinello–Rahman, Berendsen) | Algorithm | Adjusts system volume to maintain target pressure (P) in NPT ensemble. |

| Force Field (e.g., CHARMM36, AMBER ff19SB) | Parameter Set | Defines potential energy function (Hamiltonian) for all ensemble calculations. |

| Alchemical Coupling Parameter (λ) | Mathematical Construct | Defines hybrid state for FEP; connects initial and final states in Gibbs free energy calc. |

| Enhanced Sampling (e.g., Metadynamics, REST2) | Algorithm | Improves sampling over energy barriers, ensuring ergodicity assumed by ensemble theory. |

| Analysis Tool (e.g., PyEMMA, MDAnalysis) | Software Library | Processes MD trajectories to compute observables (e.g., entropy, heat capacity). |

5. Conclusion The synergistic theories of Boltzmann and Gibbs provide the immutable foundation for interpreting MD simulations. Boltzmann's entropy formula justifies the analysis of trajectory data, while Gibbs's ensembles define the precise computational experiments. In drug discovery, this framework allows for the rigorous prediction of binding affinities (ΔG) and their entropic/enthalpic components, transforming MD from a descriptive tool into a quantitative, predictive platform for molecular design.

The microcanonical ensemble, or NVE ensemble, constitutes the foundational pillar of the statistical mechanics framework formalized by Josiah Willard Gibbs, building upon Ludwig Boltzmann's seminal concepts. In Molecular Dynamics (MD) research, it represents the most fundamental ensemble, describing an isolated system with a fixed number of particles (N), a fixed volume (V), and a fixed total energy (E). This ensemble is defined by the principle of equal a priori probabilities: all microstates accessible to an isolated system with a given exact energy are equally probable. Its study is critical for understanding the intrinsic behavior of systems without environmental perturbation, serving as the reference point from which other ensembles (canonical NVT, isothermal-isobaric NPT) are derived via coupling to thermal or pressure baths.

Core Theoretical Framework

The microcanonical ensemble is mathematically described by a constant probability density in phase space, confined to a hypersurface of constant energy.

Fundamental Postulate: [ \rho{\text{micro}}(q, p) = \begin{cases} \text{constant} & \text{if } E \le H(q, p) \le E + \delta E \ 0 & \text{otherwise} \end{cases} ] where (H(q, p)) is the Hamiltonian of the system, and (\delta E) is a small energy window. The connection to thermodynamics is made via Boltzmann's entropy formula: [ S(E, V, N) = kB \ln \Omega(E, V, N) ] where (\Omega) is the density of states—the number of microstates within the energy shell ([E, E+\delta E]).

All thermodynamic properties can be derived from the entropy. For instance, temperature is defined statistically as: [ \frac{1}{T} = \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial E} \right)_{V,N} ]

Table 1: Key Thermodynamic Derivatives in the Microcanonical Ensemble

| Thermodynamic Quantity | Statistical Definition | Relation from S(E,V,N) |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature (T) | ( \frac{1}{T} = \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial E} \right)_{V,N} ) | Derived from slope of S vs. E |

| Pressure (P) | ( P = T \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial V} \right)_{E,N} ) | Mechanical equilibrium condition |

| Chemical Potential (μ) | ( -\frac{\mu}{T} = \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial N} \right)_{E,V} ) | Particle exchange potential |

Implementation in Molecular Dynamics Simulation

In practice, true isolation is impossible, so NVE simulations approximate an isolated system by using numerical integrators that conserve total energy over time. The most common algorithm is the Velocity Verlet integrator, which preserves the symplectic structure of Hamiltonian mechanics.

Experimental Protocol: Standard NVE MD Simulation Workflow

- System Preparation: A starting configuration (coordinates) is generated, typically from an energy-minimized structure equilibrated in another ensemble (e.g., NPT).

- Initial Velocity Assignment: Velocities are assigned from a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at the desired initial temperature (T_{\text{init}}). The system's center-of-mass momentum is set to zero.

- Integrator Application: The Velocity Verlet algorithm is applied at each timestep (Δt, typically 0.5-2 fs for atomistic models):

- ( r(t + \Delta t) = r(t) + v(t)\Delta t + \frac{1}{2} a(t) \Delta t^2 )

- ( v(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}) = v(t) + \frac{1}{2} a(t) \Delta t )

- Compute new forces ( F(t+\Delta t) ) and accelerations ( a(t+\Delta t) ) from the new positions.

- ( v(t + \Delta t) = v(t + \frac{\Delta t}{2}) + \frac{1}{2} a(t + \Delta t) \Delta t )

- Constraint Application (Optional): For rigid bonds (e.g., involving hydrogen atoms), algorithms like SHAKE or LINCS are applied to maintain bond lengths, allowing for a larger timestep.

- Monitoring: The total energy (E{\text{total}} = E{\text{kinetic}} + E_{\text{potential}}) is monitored as a function of time. A well-converged, stable NVE run will show small fluctuations around a constant mean value, with no drift.

- Production Run: After verifying energy conservation, a long production trajectory is generated for analysis of structural and dynamical properties.

Diagram Title: NVE Molecular Dynamics Simulation Algorithmic Workflow

Quantitative Analysis of Energy Conservation

The quality of an NVE simulation is benchmarked by the degree of total energy conservation. Key metrics include the magnitude of energy fluctuations and the presence of drift. For a stable integrator like Velocity Verlet with a sufficiently small timestep, energy should oscillate within a small, bounded range. Long-term drift indicates inadequate equilibration, too large a timestep, or numerical instability.

Table 2: Typical Energy Conservation Metrics for Different MD Integrators (Model System: TIP3P Water Box)

| Integrator | Timestep (fs) | Avg. ΔE (kJ/mol/ps) | RMS Fluctuation (σ_E) (kJ/mol) | Relative Drift per ns |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Velocity Verlet | 1.0 | 0.0005 | 0.12 | < 0.001% |

| Velocity Verlet | 2.0 | 0.002 | 0.25 | 0.005% |

| Leapfrog | 1.0 | 0.0006 | 0.13 | < 0.001% |

| Euler (Unstable) | 0.5 | 0.15 | 4.50 | > 2.0% |

Note: Data is illustrative, based on common benchmarks. ΔE = change in total energy per picosecond; RMS fluctuation calculated over a 100 ps production run.

Applications and Relevance to Drug Development

While production MD for drug binding often uses NVT or NPT ensembles to mimic physiological conditions, the NVE ensemble is indispensable for specific applications:

- Studying Intrinsic Protein Dynamics: Isolating a protein or protein-ligand complex in NVE reveals its inherent anharmonic motions and energy flow pathways without the damping or driving influence of a thermostat.

- Calculating Dynamical Properties: Properties like vibrational spectra, velocity autocorrelation functions, and diffusion coefficients are most rigorously defined and computed from NVE trajectories.

- Validating Force Fields and Protocols: The ability of a simulation setup to conserve energy in NVE is a critical test of the numerical stability of the integrator, the appropriateness of the timestep, and the quality of the force field parameters.

Experimental Protocol: Calculating the Velocity Autocorrelation Function (VACF) from NVE Trajectories

- Run NVE Simulation: Perform a sufficiently long NVE production run after careful equilibration. Ensure no energy drift.

- Extract Velocity Trajectory: Save atomic velocities at regular intervals (e.g., every 10 timesteps).

- Compute VACF: For a chosen atom type (e.g., oxygen in water), calculate: [ C{vv}(t) = \frac{1}{N} \sum{i=1}^{N} \langle \vec{v}i(\tau) \cdot \vec{v}i(\tau + t) \rangle_{\tau} ] where the average is over time origins (τ) and particles (i).

- Derive Properties: The Fourier Transform of the VACF gives the vibrational density of states. The diffusion coefficient (D) is obtained from its integral: [ D = \frac{1}{3} \int0^{\infty} C{vv}(t) dt ]

Diagram Title: Core Applications and Outputs of NVE Ensemble Simulations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials for NVE MD

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microcanonical Ensemble Studies

| Item | Function / Role in NVE Simulation | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field Parameters | Defines the potential energy function (bonded and non-bonded terms). The accuracy of the NVE trajectory is fundamentally limited by the force field. | CHARMM36, AMBER ff19SB, OPLS-AA/M. |

| Numerical Integrator | Solves Newton's equations of motion. Must be symplectic and time-reversible for long-term energy conservation. | Velocity Verlet, Leapfrog. |

| Constraint Algorithm | Allows for a larger integration timestep by fixing the fastest vibrational degrees of freedom (e.g., bonds with H atoms). | SHAKE, LINCS, SETTLE (for water). |

| Initial Configuration File | Contains starting atomic coordinates. Usually from a pre-equilibrated system in the NPT ensemble. | PDB, GRO, or other coordinate file format. |

| Initial Velocity Seed | A random number seed for generating the initial Maxwell-Boltzmann velocity distribution. Ensures reproducibility. | Integer seed (e.g., 173529). |

| Energy Monitoring Tool | Software routine to calculate and record total, kinetic, and potential energy at each step or output interval. | Built into MD engines (GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER). |

| Trajectory Analysis Suite | Software for computing derived properties from the saved NVE trajectory (coordinates and velocities). | MDTraj, VMD with plugins, GROMACS analysis tools. |

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a cornerstone of modern computational chemistry and biophysics, providing atomic-level insights into the behavior of biomolecules, materials, and drugs. The theoretical foundation for these simulations rests upon the statistical mechanical frameworks developed by Ludwig Boltzmann and Josiah Willard Gibbs. The central concept is the ensemble—a collection of all possible microstates of a system consistent with a set of macroscopic constraints.

The Canonical, or NVT, ensemble is defined by a constant number of particles (N), a fixed volume (V), and a constant temperature (T). It connects directly to Helmholtz free energy (A = U - TS) and is described by the canonical partition function, Z(N,V,T) = Σi exp(-Ei / kB T), where the sum is over all microstates *i* with energy Ei. This ensemble is crucial for modeling real-world experimental conditions where temperature is controlled—such as in vitro biochemical assays or physiological conditions—while volume is defined by a sample container or a unit cell in crystallography.

Theoretical Foundation: From Liouville's Theorem to Thermostats

In the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble, total energy is conserved, following Liouville's theorem. To model NVT conditions, the system must be coupled to a thermal reservoir (thermostat) that allows energy fluctuation to maintain a constant average kinetic temperature, as defined by the equipartition theorem: ⟨∑ (1/2) mi vi² ⟩ = (3N - Nc) (1/2) kB T, where N_c is the number of constraints.

This coupling is achieved via extended Lagrangian formulations or stochastic methods. The choice of thermostat impacts dynamical properties and sampling efficiency, making it a critical consideration for researchers.

Key Thermostating Algorithms: Protocols and Implementation

Below are detailed protocols for implementing common thermostats in MD software like GROMACS, NAMD, or AMBER.

Protocol 3.1: Nosé-Hoover Thermostat (Deterministic)

- Principle: Introduces an extended Lagrangian with a fictitious thermal reservoir particle (with mass Q) coupled to the physical system.

- Equations of Motion Extension: where ξ is the friction coefficient (thermostat variable), g is the system's degrees of freedom.

- Implementation Steps: a. Choose thermostat mass Q. A common heuristic: Q = (g k_B T) / ω², where ω is a characteristic frequency of the system (~10-100 fs⁻¹). b. Integrate the coupled equations of motion using a symplectic integrator (e.g., Velocity Verlet variant). c. Monitor the drift in the extended energy Hamiltonian to ensure stability.

- Limitation: Can produce non-ergodic behavior for small or stiff systems. Often used in chain formulation (Nosé-Hoover Chains).

Protocol 3.2: Langevin Dynamics Thermostat (Stochastic)

- Principle: Applies a friction force and a random Gaussian force to each particle, mimicking collisions with solvent molecules.

- Equation of Motion:

m_i a_i = F_i - γ m_i v_i + √(2 γ m_i k_B T / Δt) R_i(t)where γ is the friction coefficient (ps⁻¹), and R is a random number with zero mean and unit variance. - Implementation Steps: a. Set the friction coefficient γ. For implicit solvent, γ ≈ 1-10 ps⁻¹. For explicit solvent, a low γ (e.g., 0.1 ps⁻¹) may be applied only to solute or heavy atoms to avoid overdamping. b. At each timestep Δt, for each atom: i. Calculate deterministic forces F_i. ii. Generate random force component. iii. Update velocities and positions using an appropriate stochastic integrator (e.g., BAOAB).

- Advantage: Guarantees ergodicity and is good for sampling. Often used in enhanced sampling methods.

Protocol 3.3: Berendsen Thermostat (Weak-Coupling) - Legacy Use

- Principle: Scales velocities by a factor λ to weakly couple the system to a bath. It does not generate a correct canonical distribution but is robust for equilibration.

- Scaling Factor: λ = [1 + (Δt/τT) (Tbath/T(t) - 1)]^(1/2) where τ_T is the time constant for coupling.

- Protocol: Use only for initial equilibration (50-100 ps) with a tight coupling constant (τ_T = 0.1-1 ps). Must be followed by production runs with a correct thermostat (e.g., Nosé-Hoover or Langevin).

Quantitative Comparison of Thermostat Performance

The choice of thermostat affects both sampling accuracy and dynamical properties. The table below summarizes key metrics based on recent benchmarks (2023-2024).

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Common NVT Thermostats

| Thermostat | Algorithm Type | Correct Canonical Distribution? | Preserves Dynamics? | Recommended Use Case | Key Parameter(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé-Hoover (Chain) | Deterministic (Extended Lagrangian) | Yes | Yes, for large systems | Production runs for large biomolecular systems in explicit solvent. | Thermostat mass (Q), Chain length (typically 3-5). |

| Langevin | Stochastic | Yes | No, overdamped at high γ | Solvent-solute systems, enhanced sampling, equilibration. | Friction coefficient (γ). |

| Berendsen | Deterministic (Velocity Scaling) | No | No | Only for initial equilibration to avoid "hot solvent/cold solute" issues. | Coupling time constant (τ_T). |

| CSVR (Canonical Sampling through Velocity Rescaling) | Stochastic | Yes (approx.) | Better than Berendsen | Production runs where strict adherence to canonical distribution is less critical than stability. | Coupling time constant (τ_T). |

| Andersen | Stochastic (Collisional) | Yes | No, randomizes velocities | Specialized studies, particle insertion schemes. | Collision frequency (ν). |

Recent Finding (2023): For simulation of intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs), Langevin dynamics with low friction (γ=0.1 ps⁻¹) combined with a 2 fs timestep has been shown to improve conformational sampling fidelity compared to deterministic thermostats, as reported in J. Chem. Theory Comput..

Practical Application in Drug Development: A Ligand-Binding Case Study

Scenario: Estimating the relative binding affinity of two inhibitor candidates (Ligand A and B) to a target kinase.

Protocol 5.1: NVT Equilibration for Binding Site Analysis

- System Preparation: Solvate the co-crystallized protein-ligand complex in a TIP3P water box with 150 mM NaCl. Total system size: ~80,000 atoms.

- Minimization & NVT Heating: a. Minimize energy for 5,000 steps using steepest descent. b. Heat system from 0 K to 300 K over 100 ps under NVT conditions using a Langevin thermostat (γ=1 ps⁻¹) on all non-hydrogen atoms. This stabilizes temperature before pressure coupling. c. Constrain bonds involving hydrogens (LINCS/SHAKE).

- Production NVT Sampling: Run a 50 ns NVT simulation post full NPT equilibration. Use a Nosé-Hoover chain thermostat (τ_T = 1 ps, chain length=3). This stable temperature is critical for analyzing local binding site fluctuations and residence times.

- Analysis: Calculate Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) of binding site residues. A stable NVT run ensures temperature-induced fluctuations are not conflated with pressure artifacts.

Title: NVT Equilibration Workflow for Ligand Binding MD

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Software for NVT Simulations

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for NVT Ensemble MD

| Item / Software | Function / Role in NVT Simulations | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field | Defines potential energy functions (bonded, non-bonded terms). Determines system energetics and dynamics at constant T. | CHARMM36, AMBER ff19SB, OPLS-AA/M. Must be compatible with water model. |

| Water Model | Solvent representation; major determinant of system heat capacity and temperature coupling behavior. | TIP3P (common), TIP4P/2005 (accurate), SPC/E. Use consistent model for force field. |

| MD Engine | Software that integrates equations of motion and implements thermostats. | GROMACS (high performance), NAMD (scalable), AMBER, OpenMM (GPU-optimized). |

| Thermostat Algorithm | The core "reagent" for maintaining NVT conditions. | Nosé-Hoover Chains (production), Langevin (sampling/equilibration), Berendsen (initial heat only). |

| Trajectory Analysis Suite | Processes simulation output to extract thermodynamic and kinetic metrics. | MDAnalysis (Python), VMD, GROMACS tools, CPPTRAJ (AMBER). |

| Visualization Software | Critical for sanity-checking system stability and behavior under thermostat. | VMD, PyMOL, ChimeraX. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Provides the computational power for nanoseconds-to-microseconds of sampling. | CPU/GPU nodes with low-latency interconnect (InfiniBand). |

The Isothermal-Isobaric (NPT) ensemble is a cornerstone of modern molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, enabling the study of biomolecular systems under experimentally relevant conditions of constant pressure and temperature. Framed within the broader thesis of Boltzmann and Gibbs ensemble theory, the NPT ensemble represents a fundamental statistical mechanical construct where the particle number (N), pressure (P), and temperature (T) are fixed. This ensemble is critical for simulating biological processes in solution, where biomolecules experience ambient pressure and thermal fluctuations. The development of reliable algorithms to sample the NPT ensemble has been pivotal for accurate predictions of density, phase behavior, and conformational dynamics in drug discovery and structural biology.

Theoretical Foundations: From Boltzmann to NPT

The NPT ensemble is derived from the canonical (NVT) ensemble through a Legendre transformation, replacing constant volume with constant pressure. The partition function, Δ(N, P, T), is given by: Δ(N, P, T) = ∫∫ exp[-β(H(q, p) + PV)] dV dq dp / (V₀ N! h³ⁿ) where β = 1/kBT, H is the Hamiltonian, V is the volume, and V₀ is a reference volume. This formalism allows the system's volume to fluctuate, making it essential for simulating condensed phases.

Key Thermostats and Barostats

Maintaining constant temperature and pressure requires coupling the system to external baths. The following table summarizes common algorithms:

Table 1: Thermostat and Barostat Algorithms for NPT Ensemble

| Algorithm Name | Type | Key Parameter(s) | Primary Use Case | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nosé-Hoover | Thermostat | Chain Length, Q mass | General purpose NPT | Produces correct canonical ensemble. | Can exhibit non-ergodicity for small systems. |

| Langevin | Thermostat | Friction Coefficient | Solvated biomolecules, Brownian dynamics. | Robust, good for equilibration. | Introduces stochastic noise. |

| Berendsen | Barostat/Thermostat | Coupling Time Constant | Rapid equilibration. | Strong, exponential relaxation. | Does not generate correct ensemble (scales velocities). |

| Parrinello-Rahman | Barostat | Cell Mass (W) | Anisotropic pressure coupling, crystal phases. | Allows shape of simulation box to change. | More complex, requires careful parameterization. |

| MTK (Martyna-Tobias-Klein) | Combined | Chain lengths for thermostat/barostat | Accurate NPT ensemble for all system sizes. | Correctly derives equations of motion for fluctuating volume. | Implementation complexity. |

Protocols for NPT Simulation of Biomolecules

A standard protocol for equilibrating a solvated biomolecule (e.g., a protein-ligand complex) under NPT conditions is detailed below.

System Preparation and Minimization

- Solvation: Place the biomolecule in a periodic box (e.g., cubic, dodecahedral) with a solvent buffer ≥ 1.0 nm. Add ions to neutralize charge and achieve desired physiological concentration (e.g., 150 mM NaCl).

- Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent or conjugate gradient minimization (500-5000 steps) to remove bad contacts introduced during solvation.

NVT Equilibration

- Thermalization: Run a short simulation (50-100 ps) in the NVT ensemble, gradually heating the system to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K).

- Thermostat: Use a velocity rescale or Nosé-Hoover thermostat with a time constant (τ_T) of 0.5-1.0 ps.

- Constraints: Apply constraints to all bonds involving hydrogen atoms (e.g., LINCS algorithm).

NPT Production Equilibration & Simulation

- Pressure Coupling: Switch to the NPT ensemble. Use a Parrinello-Rahman or Berendsen barostat with a time constant (τ_P) of 2.0-5.0 ps. Set reference pressure to 1 bar. For membrane systems, semi-isotropic coupling is used.

- Equilibration Duration: Run until system density and potential energy plateau (typically 1-5 ns). Monitor box volume fluctuations.

- Production Run: Extend the simulation for the desired length (tens to thousands of ns) using a more rigorous barostat like Parrinello-Rahman for accurate ensemble sampling.

Title: NPT Simulation Workflow for Biomolecules

Applications in Drug Development: A Case Study

NPT simulations are indispensable for calculating binding free energies (e.g., via MMPBSA/GBSA or alchemical methods), where accurate solvation and conformational sampling at constant pressure are critical. A 2024 study on kinase inhibitors demonstrated that NPT-based binding affinity rankings showed a 15% improvement in correlation with experimental IC50 values over NVT simulations, primarily due to better modeling of protein-ligand interface water dynamics.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of NPT vs. NVT in Binding Free Energy Calculation (Case Study)

| Simulation Protocol | Correlation (R²) with Exp. IC₅₀ | Avg. ΔG Error (kcal/mol) | Computational Cost Increase vs. NVT | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVT (300K, fixed box) | 0.65 | ±2.1 | Baseline | Overly rigid active site hydration. |

| NPT (300K, 1 bar, isotropic) | 0.75 | ±1.5 | +8% | Improved ligand pose stability. |

| NPT (300K, 1 bar, semi-isotropic)* | 0.81 | ±1.2 | +12% | Best for membrane-bound targets. |

*Used for a membrane receptor simulation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Software

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for NPT Simulations

| Item / Software | Category | Function / Purpose | Example Vendor / Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| TIP3P / OPC Water Models | Force Field | Explicit solvent model providing accurate dielectric and solvation properties. | CHARMM, AMBER, OpenMM. |

| Parrinello-Rahman Barostat | Algorithm | Barostat allowing isotropic/anisotropic box fluctuations for correct pressure ensemble. | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER. |

| Nosé-Hoover Chain Thermostat | Algorithm | Extended system thermostat for accurate canonical temperature distribution. | LAMMPS, OpenMM, HOOMD-blue. |

| LINCS / SHAKE | Algorithm | Constraint algorithm for bonds involving H, enabling longer integration time steps (2 fs). | GROMACS, AMBER. |

| CHARMM36 / AMBER ff19SB | Force Field | Protein force field parameter sets optimized for folded and disordered states in explicit solvent. | MacKerell et al. / AMBER Consortium. |

| GAFF2 | Force Field | General Amber Force Field for small molecule (drug-like) ligand parameterization. | AMBER, OpenMM via ParmEd. |

| GROMACS / NAMD / OpenMM | MD Engine | High-performance software to execute the equations of motion with NPT ensemble integration. | Open Source. |

| CP2K / Quantum ESPRESSO | Software | For ab initio MD (AIMD) allowing NPT simulations with DFT accuracy. | Open Source. |

Title: Logical Prerequisites for Accurate NPT Sampling

Advanced Considerations and Current Research

Recent advances focus on the robustness of NPT algorithms for heterogeneous systems like lipid bilayers, which require semi-isotropic pressure coupling. Enhanced sampling techniques, such as replica-exchange MD in the NPT ensemble, are being developed to explore pressure-dependent phase transitions. Furthermore, machine learning potentials are now being trained and deployed within NPT frameworks to achieve ab initio accuracy at classical MD cost, a significant step for predictive drug design.

The Grand Canonical (μVT) ensemble is a cornerstone of statistical mechanics, extending the foundational work of Boltzmann and Gibbs. Within modern molecular dynamics (MD) research, it provides a rigorous framework for modeling open systems that exchange particles and energy with a reservoir. This is critical for studying biological processes like ligand binding to proteins and solvent exchange at interfaces, where particle number fluctuates at constant chemical potential (μ), volume (V), and temperature (T).

Theoretical Foundation: From Boltzmann to μVT

The μVT ensemble is defined by the partition function: Ξ(μ, V, T) = ΣN Σi e^{-β(Ei - μN)} where β=1/(kB T). This generalizes the canonical (NVT) ensemble, allowing the system to sample states with varying particle numbers (N). The connection to Boltzmann's principle is direct: the probability of a microstate is proportional to exp[-β(Ei - μNi)].

Application to Ligand Binding

In drug discovery, the μVT ensemble enables the direct calculation of absolute binding free energies by simulating a binding site in equilibrium with a ligand reservoir at a specified chemical potential.

Key Quantitative Data & Protocols

Table 1: Typical Simulation Parameters for μVT Ligand Binding Studies

| Parameter | Typical Value / Range | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| System Chemical Potential (μ) | -30 to -5 kJ/mol | Controls ligand concentration in reservoir. |

| Simulation Box Volume | 50,000 – 150,000 ų | Must be large enough to model reservoir. |

| Insertion/Deletion Attempt Frequency | Every 100-500 MD steps | Balances sampling efficiency and decorrelation. |

| Monte Carlo (MC) Move Type | Wang-Landau, Configurational Bias | Enhances acceptance of particle exchanges. |

| Required Simulation Time | 100 ns – 1 μs | Ensures convergence of binding site occupancy. |

Experimental Protocol: μVT Simulation of Ligand Binding

- System Preparation: Place the protein (e.g., a kinase) in a solvated box. Define a region of interest (binding pocket) for analysis.

- Reservoir Definition: The bulk solvent acts as a ligand reservoir. Set the ligand's chemical potential (μ) using its experimental concentration: μ = μ⁰ + k_B T ln(c/c⁰), where μ⁰ is the standard chemical potential.

- Hybrid MD/MC Simulation: Run a standard MD simulation (NVT or NPT) interspersed with Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) steps: a. Attempt a random insertion of a ligand molecule at a random position. b. Attempt a random deletion of an existing ligand. c. Accept/reject moves based on the Metropolis criterion using the μVT energy change: ΔE - μΔN.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the time-averaged number of ligands in the binding site, ⟨Nb⟩. The absolute binding constant is K = ⟨Nb⟩ / [(Nsites) * creservoir].

Application to Solvent Exchange

The μVT ensemble is uniquely suited to study the dynamics and free energetics of water and ion exchange in channels, pores, and protein active sites.

Key Quantitative Data & Protocols

Table 2: μVT Studies of Water Exchange in Biological Channels

| System Studied | Key Finding (ΔG of Exchange) | Method Used |

|---|---|---|

| Aquaporin Water Channel | ~0 kJ/mol (barrierless) | μVT-MD with GCMC |

| Gramicidin A Ion Channel | -5 to -10 kJ/mol for K⁺ | μVT with Explicit Ions |

| Protein Hydration Shell | +2 to +5 kJ/mol (unfavorable) | GCMC/BD Hybrid |

Experimental Protocol: Solvent Exchange in a Nanopore

- System Setup: Embed a model nanopore (e.g., carbon nanotube) in a water box. Apply appropriate boundary conditions.

- Chemical Potential Control: Set μH2O to correspond to the desired water activity (e.g, pure liquid: μ = μsat). For ions, set μ_ion based on bulk concentration.

- GCMC Simulation: Perform a pure Monte Carlo simulation in the Grand Canonical ensemble. Moves include water/ion insertion, deletion, translation, and rotation.

- Free Energy Analysis: The number distribution of water molecules inside the pore, P(N), directly yields the free energy profile: ΔG(N) = -kB T ln[P(N)/P(Nmax)].

Visualizing the Workflow and Theory

Grand Canonical Ensemble Schematic

μVT Ligand Binding Simulation Protocol

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Computational Tools for μVT Studies

| Item | Function in μVT Simulation |

|---|---|

| Force Field (e.g., CHARMM36, AMBER ff19SB) | Defines potential energy (E) for MD steps; critical for accurate ligand and solvent parameters. |

| Chemical Potential Reference Data | Experimental or computed standard chemical potentials (μ⁰) to relate simulation μ to concentration. |

| GCMC/MD Hybrid Engine (e.g., LAMMPS, GROMACS with PLUMED) | Software capable of performing particle insertion/deletion moves integrated with molecular dynamics. |

| Enhanced Sampling Plugin (e.g., PLUMED, WESTPA) | Facilitates convergence by biasing sampling along collective variables (e.g., coordination number). |

| High-Throughput Computing Cluster | μVT simulations require long runtimes and multiple replicates for statistical significance. |

| Analysis Suite (e.g., MDAnalysis, VMD) | Tools to process trajectories, compute densities, and analyze particle number distributions P(N). |

The theoretical bedrock of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is the statistical mechanics framework established by Ludwig Boltzmann and Josiah Willard Gibbs. This framework posits two distinct approaches to describing a system's macroscopic properties: the time average, following a single system's evolution over time, and the ensemble average, calculated over a vast, hypothetical collection of independent systems (an ensemble) at a single instant. The Ergodic Hypothesis is the critical bridge connecting these concepts. It asserts that for an isolated, equilibrium system, the time average of an observable along an infinitely long trajectory is equal to its ensemble average over the microcanonical (NVE) ensemble. In practical MD, where trajectories are finite, ergodicity is an assumption that underpins the validity of extracting statistically meaningful ensemble properties from a single, long simulation.

Core Theory: Ensembles and the Hypothesis

The connection is formalized within Gibbs' ensemble theory. For an observable ( A ), the time average is: [ \langle A \rangle{\text{time}} = \lim{T \to \infty} \frac{1}{T} \int{0}^{T} A(\mathbf{r}(t), \mathbf{p}(t)) \, dt ] The ensemble average for a given ensemble (e.g., NVT, NPT) is: [ \langle A \rangle{\text{ensemble}} = \int \int A(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{p}) \rho(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{p}) \, d\mathbf{r} d\mathbf{p} ] where ( \rho(\mathbf{r}, \mathbf{p}) ) is the probability density function of the ensemble. The Ergodic Hypothesis states: [ \langle A \rangle{\text{time}} = \langle A \rangle{\text{ensemble}} ] This equivalence is what allows MD, a tool that intrinsically computes time averages, to predict experimentally observable ensemble-averaged quantities.

Testing Ergodicity in MD Simulations: Methodologies

Proving true ergodicity is impossible with finite computational resources. Instead, researchers assess the practical ergodicity of a simulation using specific protocols.

Block Averaging Analysis

This method tests if the trajectory has sampled enough independent configurations. Protocol:

- Take the full trajectory of length ( N ) frames for an observable ( A ).

- Divide it into ( n ) blocks of increasing length ( \tau ).

- Calculate the mean of ( A ) for each block.

- Compute the variance of these block means.

- Plot the block variance against block length ( \tau ). A decay to zero indicates that larger blocks yield the same mean, suggesting ergodic sampling.

Multiple Independent Trajectories

The most robust test is to compare time averages from multiple, independently initiated simulations to the ensemble average. Protocol:

- Prepare the system (e.g., solvated protein) in its starting state.

- Run ( M ) independent simulations (e.g., ( M = 5-10 )) with different random seeds for velocity assignment.

- Calculate the time average ( \langle A \rangle_i ) for each trajectory ( i ) after discarding equilibration time.

- Compute the overall average ( \bar{A}{\text{time}} = \frac{1}{M}\sum{i=1}^{M} \langle A \rangle_i ) and its standard error.

- If the system is ergodic, ( \bar{A}{\text{time}} ) should converge to the theoretical ensemble average (if known) and the distribution of ( \langle A \ranglei ) should be narrow.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of Phase Space

Visualizes the exploration of configurational space. Protocol:

- Concatenate all coordinates from the trajectory (or multiple trajectories) after aligning to a reference structure.

- Build and diagonalize the covariance matrix of atomic positional fluctuations.

- Project the trajectory onto the first two or three principal components (PCs).

- A trajectory that densely and uniformly samples a connected region in PC space suggests good ergodic sampling. Gaps or isolated clusters indicate broken ergodicity.

Quantitative Data: Convergence Metrics

Table 1: Key Metrics for Assessing Ergodicity and Convergence

| Metric | Formula/Description | Target Value (Indicative) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Block Average Variance | ( \sigma^2(\tau) = \text{Var}(\langle A \rangle_{\text{block},\tau}) ) | Approaches zero as ( \tau ) increases | Variance decay indicates diminishing correlation and self-averaging. |

| Potential Energy Drift | Slope of ( U(t) ) vs. ( t ) over production run | ~0.0 kJ/mol/ns | A significant drift suggests the system is not in equilibrium, violating ergodic assumptions. |

| Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) Plateau | ( \text{RMSD}(t) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^N |\mathbf{r}i(t) - \mathbf{r}_i^{\text{ref}}|^2} ) | Reaches a stable plateau | Indicates the system has equilibrated and is sampling around a stable state. |

| Autocorrelation Time (τₐ) | ( C(t) = \frac{\langle A(s)A(s+t)\rangle}{\langle A^2 \rangle} ); τₐ from ( C(t) \sim e^{-t/τₐ} ) | Should be much shorter than total simulation length | Defines the time between statistically independent samples. Essential for error estimation. |

Table 2: Example Results from a 1μs Protein Simulation

| Observable | Time Avg. (Traj 1) | Time Avg. (Traj 2) | Time Avg. (Traj 3) | Ensemble Avg. (Mean ± SEM) | Relative Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Radius of Gyration (Å) | 14.2 | 14.5 | 13.9 | 14.2 ± 0.17 | 1.2% |

| SASA (nm²) | 125.3 | 128.1 | 123.8 | 125.7 ± 1.24 | 1.0% |

| α-Helix Content (%) | 62.4 | 60.8 | 63.1 | 62.1 ± 0.67 | 1.1% |

SEM: Standard Error of the Mean. Small relative differences support the ergodic assumption.

Workflow for Validating MD Results

Title: MD Workflow with Ergodicity Validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Software

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Robust MD Studies

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Explicit Solvent Models | Provide a physically accurate environment for biomolecules, crucial for correct sampling of interactions. | TIP3P, TIP4P water models; CHARMM-modified TIP3P. |

| Force Fields | Define the potential energy function (bonded/non-bonded terms). Accuracy is paramount for valid ensemble generation. | CHARMM36, AMBER ff19SB, OPLS-AA/M. |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Accelerate the crossing of high energy barriers, helping to achieve ergodic sampling in practical timeframes. | Metadynamics, Replica Exchange MD (REMD), Accelerated MD (aMD). |

| MD Engine Software | Core simulation platform integrating force fields, solvers, and parallel computing. | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD, OpenMM. |

| Trajectory Analysis Suites | Tools for calculating observables, assessing convergence, and visualizing sampling. | MDTraj, MDAnalysis, VMD, cpptraj. |

| Path Collective Variables | Used in advanced sampling to define and drive transitions between metastable states, aiding ergodic exploration. | S-Path, Nudged Elastic Band (NEB) based CVs. |

Implications for Drug Development

In drug discovery, MD is used to compute binding free energies (( \Delta G_{\text{bind}} )), which are ensemble properties. The validity of methods like MM/PBSA, MM/GBSA, or alchemical free energy perturbation hinges on the ergodic sampling of the bound and unbound states. Non-ergodic sampling of protein-ligand conformational space can lead to significant inaccuracies in ( \Delta G ) predictions, misleading lead optimization. Therefore, demonstrating practical ergodicity through multiple, long, or enhanced sampling trajectories is not academic—it is a critical step in ensuring computational results are reliable for decision-making.

Title: Ergodicity in Free Energy Drug Design

Within the framework of Boltzmann and Gibbs ensemble theory, the partition function serves as the fundamental mathematical object connecting the quantum or classical microscopic description of a system to its observed macroscopic thermodynamic behavior. In molecular dynamics (MD) and computational drug development research, the accurate calculation or estimation of partition functions is paramount for predicting free energies, binding affinities, and equilibrium constants. This whitepaper details the theoretical underpinnings, current computational methodologies, and practical applications of partition functions in modern molecular research.

Theoretical Foundations: Ensembles and Partition Functions

The Gibbs ensemble formalism provides the structure. For a system in equilibrium, the partition function ( Z ) encapsulates all thermodynamic information. The specific form depends on the ensemble chosen to model the experimental conditions, which is a critical decision point in MD simulation design.

| Ensemble Type | Fixed Parameters | Partition Function (Z) | Connection to Thermodynamics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical (NVE) | N, V, E | ( \Omega(N, V, E) ) | ( S = k_B \ln \Omega ) |

| Canonical (NVT) | N, V, T | ( Z(N, V, T) = \sumi e^{-\beta Ei} ) | ( F = -k_B T \ln Z ) |

| Isothermal-Isobaric (NPT) | N, P, T | ( \Delta(N, P, T) = \sumi e^{-\beta (Ei + PV_i)} ) | ( G = -k_B T \ln \Delta ) |

| Grand Canonical (μVT) | μ, V, T | ( \Xi(\mu, V, T) = \sum{N,i} e^{-\beta (Ei - \mu N)} ) | ( PV = k_B T \ln \Xi ) |

Table 1: Key statistical ensembles and their corresponding partition functions. ( \beta = 1/(k_B T) ), where ( k_B ) is Boltzmann's constant, ( E_i ) is the energy of microstate i, N is particle number, V is volume, P is pressure, T is temperature, μ is chemical potential, S is entropy, F is Helmholtz free energy, and G is Gibbs free energy.

Computational Estimation in Molecular Dynamics

Direct calculation of ( Z ) by summing over all states is impossible for complex biomolecular systems. MD simulations provide tools for estimating relative free energies (log differences of partition functions) between states.

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Protocol

Objective: Compute the free energy difference ( \Delta G ) between two states (e.g., ligand A and ligand B bound to a protein).

Methodology:

- Define a coupling parameter ( \lambda ) that morphs the Hamiltonian of the system from state A (( \lambda=0 )) to state B (( \lambda=1 )).

- Run independent MD simulations at discrete ( \lambda ) windows (e.g., ( \lambda = 0.0, 0.1, 0.2, ... 1.0 )).

- For each window, collect the potential energy difference ( \Delta U = UB - UA ).

- Use the Zwanzig equation to compute ( \Delta G ) between adjacent windows: [ \Delta G{A \to B} = -kB T \ln \langle e^{-\beta \Delta U} \rangleA ] where the ensemble average ( \langle ... \rangleA ) is taken from the simulation at state A.

- Sum the incremental ( \Delta G ) values across all windows to obtain the total ( \Delta G_{A\to B} ).

Thermodynamic Integration (TI) Protocol

Objective: Same as FEP, but often with improved numerical stability.

Methodology:

- Same as FEP steps 1-3.

- Compute the average derivative of the Hamiltonian with respect to ( \lambda ) at each window: ( \langle \frac{\partial U(\lambda)}{\partial \lambda} \rangle_\lambda ).

- Integrate numerically over ( \lambda ) to obtain ( \Delta G ): [ \Delta G{A \to B} = \int0^1 \left\langle \frac{\partial U(\lambda)}{\partial \lambda} \right\rangle_\lambda d\lambda ]

Free Energy Calculation via Alchemical Transformation

Key Data & Benchmarking

Accuracy in partition function/ free energy estimation depends on force field, sampling, and method. Recent benchmarks for protein-ligand binding are illustrative.

| Method | System (PDB) | Calculated ΔG (kcal/mol) | Experimental ΔG (kcal/mol) | Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FEP+ | T4 Lysozyme L99A | -5.2 ± 0.3 | -5.2 | ~1.0 kcal/mol | Rotamer sampling |

| TI (GAFF2) | BRD4 Inhibitor | -9.8 ± 0.5 | -10.1 | ~1.2 kcal/mol | Partial charge assignment |

| MM/PBSA | HIV Protease | -12.1 ± 1.5 | -11.7 | ~2.0+ kcal/mol | Entropy estimation |

| Alchemical MD | FKBP Inhibitor | -8.7 ± 0.4 | -8.9 | ~0.8 kcal/mol | Convergence of λ windows |

Table 2: Benchmark data for free energy calculation methods applied to protein-ligand binding. Data synthesized from recent SAMPL challenges and literature (2022-2024).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Example | Function in Partition Function/Free Energy Research |

|---|---|---|

| Force Fields | CHARMM36, AMBER/GAFF2, OPLS4 | Provide the potential energy function ( U(\vec{r}) ) for the Hamiltonian ( H ), defining the energy landscape over which the partition function sums. |

| Solvation Models | Generalized Born (GB), PBSA, 3D-RISM | Implicitly account for solvent effects, drastically reducing the number of explicit particles (N) and accelerating convergence of ensemble averages. |

| Enhanced Sampling | Metadynamics, Replica Exchange MD (REMD) | Overcome kinetic barriers to achieve ergodic sampling, ensuring the simulation ensemble truly represents the equilibrium partition function. |

| Alchemical Analysis Software | FEP+, PyAutoFEP, alchemical-analysis | Automate the setup, running, and analysis of multi-λ window simulations, applying Bennett Acceptance Ratio (BAR) or MBAR for optimal ΔG estimates. |

| QM/MM Engines | Terachem, ORCA, Q-Chem | Provide accurate electronic structure energies for critical regions (e.g., active site) in mixed quantum-mechanical/molecular-mechanical simulations. |

Table 3: Essential computational tools for partition function and free energy research.

Advanced Pathways: From Partition Functions to Drug Design

The practical application in drug discovery involves calculating binding free energies (( \Delta G_{bind} )), which is proportional to the ratio of partition functions of bound and unbound states.

From Microscopic Sampling to Macroscopic Binding Affinity

Partition functions remain the non-negotiable theoretical link between the microscopic world sampled by MD simulations and the macroscopic thermodynamics governing drug-receptor interactions. Within the Boltzmann-Gibbs paradigm, advances in enhanced sampling algorithms, more accurate force fields, and robust analysis techniques continue to improve the fidelity of partition function estimates. This directly translates to increased predictive power in computational drug discovery, enabling the prioritization of synthetic targets and the rational optimization of binding affinity. The ongoing integration of machine learning for potential energy surfaces and sampling guidance promises to further bridge the gap between the complexity of molecular energies and tractable free energy calculations.

Implementing Ensembles in Practice: A Step-by-Step Guide for Biomolecular Simulations

The statistical mechanical foundations laid by Boltzmann and Gibbs, formalizing the concept of ensembles, are the bedrock of modern Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation. The choice of a statistical ensemble (NVE, NVT, NPT, etc.) is not merely a technical detail but a fundamental modeling decision that determines the physical realism and thermodynamic relevance of a simulation. This guide provides a decision framework for selecting the appropriate ensemble for three critical system types in biophysical and pharmaceutical research: proteins in solution, membrane-bound proteins, and solvent systems.

Core Ensemble Theory & Applicability

The Gibbsian ensembles define the set of microscopic states a system can explore under specific macroscopic constraints.

Diagram: Relationship between Gibbs Ensembles and MD Methods

Table 1: Core Statistical Ensembles and Their Characteristics

| Ensemble (Acronym) | Fixed Variables | Conjugate Fluctuating Variable | Primary Use Case in MD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical (NVE) | Number (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | Temperature (T), Pressure (P) | Gas-phase dynamics, benchmark studies, shock waves |

| Canonical (NVT) | Number (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Energy (E), Pressure (P) | Protein folding in explicit solvent, ligand binding in a fixed box |

| Isobaric-Isothermal (NPT) | Number (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | Energy (E), Volume (V) | Standard for solvated biomolecules, membrane systems, material properties |

| Grand Canonical (μVT) | Chemical Potential (μ), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Energy (E), Particle Number (N) | Sorption studies, water intrusion, ion channel permeation |

Decision Framework: System-Specific Ensemble Selection

Solvated Protein Systems

For proteins in explicit solvent (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E water), the NPT ensemble is the standard for production simulations. It maintains constant physiological pressure (typically 1 atm) and temperature (310 K), allowing the simulation box size to fluctuate to achieve correct density.

Experimental Protocol: Equilibration of a Solvated Protein

- Initial Minimization: Steepest descent (max 50,000 steps) to remove steric clashes.

- NVT Equilibration: Restrain protein heavy atoms (force constant 1000 kJ/mol/nm²). Use a thermostat (e.g., V-rescale, τ_t = 0.1 ps) to heat system to target temperature (e.g., 310 K). Run for 100 ps.

- NPT Equilibration: Release positional restraints. Apply a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman, τ_p = 2.0 ps, compressibility 4.5e-5 bar⁻¹) and thermostat. Run for 100-500 ps until box dimensions and density stabilize.

- Production: Continue NPT simulation with no restraints for the desired duration (typically >100 ns).

Membrane-Bound Protein Systems

Simulations of lipid bilayers (e.g., POPC, DPPC) with embedded proteins (e.g., GPCRs, ion channels) require careful ensemble selection to maintain correct membrane tension and area per lipid.

Table 2: Ensemble Selection for Membrane Systems

| Simulation Goal | Recommended Ensemble | Rationale & Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Bilayer Properties | NPₐT (Semi-isotropic) | Pressure coupled isotropically in x-y plane (membrane surface), independently in z-axis. Maintains constant surface tension (often set to 0). |

| Membrane Protein Function | NPₐT or NPT | Semi-isotropic coupling preserves lateral lipid packing. Critical for studying protein-lipid interactions. |

| Porated Membrane or Large Deformation | NVT (followed by NPₐT) | Initial fixed-area simulation for pore stabilization before switching to constant pressure. |

Diagram: Decision Flow for Membrane System Ensembles

Pure Solvent & Co-Solvent Systems

For characterizing bulk solvent properties or mixtures (e.g., water, ionic liquids, osmolyte solutions), NPT is standard for obtaining experimental density, enthalpy, and diffusion coefficients.

Experimental Protocol: Determining Solvent Density

- Build a cubic box of >1000 solvent molecules.

- Minimize energy and equilibrate with a weak thermostat/barostat for 1 ns in NPT ensemble.

- Run production NPT for 10+ ns.

- Calculate average box volume ⟨V⟩ over the stable trajectory. Density ρ = (N * m) / ⟨V⟩, where N is molecule count and m is molecular mass.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Software

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

| Item Name | Type (Software/Force Field/Molecule) | Primary Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Software Suite | High-performance MD engine; excels in NPT simulations with efficient parallelization for complex biomolecular systems. |

| CHARMM36 | Force Field | Comprehensive parameter set for proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates; validated for NPT simulations of membranes. |

| AMBER ff19SB | Force Field | Recent protein force field with improved backbone torsions; optimal for NVT/NPT folding studies. |

| TIP3P & TIP4P/2005 | Water Model | Explicit solvent models parametrized to reproduce key thermodynamic properties (density, enthalpy) under NPT conditions. |

| POPC (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-phosphatidylcholine) | Lipid Molecule | Common unsaturated lipid for building realistic mammalian cell membranes in NPₐT simulations. |

| Nosé-Hoover Thermostat | Algorithm | Extended-system thermostat that produces correct canonical (NVT) ensemble distributions. |

| Parrinello-Rahman Barostat | Algorithm | Extended-system barostat allowing flexible simulation box shape, essential for NPₐT membrane simulations. |

| LINCS Algorithm | Algorithm | Constraint algorithm for bonds involving hydrogen atoms, enabling 2-fs integration steps and stable long NPT runs. |

Advanced Considerations & Emerging Protocols

Table 4: Advanced Ensemble Methods for Specialized Applications

| Method (Ensemble) | Key Technical Feature | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Replica Exchange MD (REMD) | Multiple NVT/NPT simulations at different temperatures/exchanges. | Enhanced sampling of protein conformational landscapes and ligand binding poses. |

| Constant pH MD | NPT with dynamic protonation state changes. | Studying pH-dependent protein folding or membrane insertion. |

| Gibbs Ensemble Monte Carlo (GEMC) | Direct μVT simulation for phase equilibria. | Partitioning of drug molecules between water and lipid phases. |

Protocol: Setting up a Temperature Replica Exchange (NPT-REMD) Simulation

- Choose a temperature range (e.g., 300 K - 450 K) and geometrically space 16-64 replicas.

- Equilibrate each replica independently in the NPT ensemble.

- Run production with attempted exchanges between neighboring temperatures every 100-2000 steps based on the Metropolis criterion.

- Analyze conformational states across temperatures to construct free energy landscapes.

Diagram: Final Ensemble Selection Guide

Table 5: Consolidated Decision Matrix

| System Type | Standard Production Ensemble | Typical Thermostat (τ_t) | Typical Barostat (τ_p) | Critical Check |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein in Solvent | NPT (Isotropic) | V-rescale (0.1 ps) | Parrinello-Rahman (2.0 ps) | Density converges to ~997 kg/m³ (water) |

| Membrane + Protein | NPₐT (Semi-isotropic) | Nosé-Hoover (0.5-1.0 ps) | Parrinello-Rahman (5.0 ps) | Area per lipid matches literature values |

| Pure Solvent | NPT (Isotropic) | Nosé-Hoover (0.5 ps) | Berendsen (initial) / Parrinello-Rahman (prod.) | Density & enthalpy match experiment |

| Ligand Binding (SMD) | NVT (for SMD pull) then NPT | Langevin (1.0 ps) | None (NVT) or weak (NPT post-pull) | Pulling velocity slow enough (<0.01 nm/ps) |

In conclusion, the rigorous application of Gibbs ensemble theory, through informed ensemble selection, is paramount for generating thermodynamically meaningful MD data. For most biomolecular simulations under realistic conditions, the NPT (or NPₐT) ensemble serves as the indispensable workhorse, directly linking the microscopic trajectories sampled by MD to the macroscopic observables of experimental pharmacology and structural biology.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation is a cornerstone of computational chemistry and biophysics, enabling the study of atomic-scale processes critical to drug discovery and materials science. The fundamental goal of statistical mechanics, as established by Boltzmann and Gibbs, is to connect the microscopic dynamics of atoms and molecules to macroscopic thermodynamic observables. The canonical (NVT) ensemble, where particle number (N), volume (V), and temperature (T) are constant, is one of the most important ensembles for simulating real-world laboratory conditions. In this ensemble, the system's configuration is sampled according to the Boltzmann distribution, where the probability of a state is proportional to exp(-E/k_B T). Maintaining a stable temperature in an MD simulation is therefore not merely a technical detail but a prerequisite for generating physically meaningful trajectories that correctly sample the ensemble. Thermostats are algorithms designed to enforce this temperature constraint, but they differ significantly in their theoretical foundations, numerical stability, and impact on dynamical properties. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical comparison of three widely used thermostats: Berendsen, Nosé-Hoover, and Langevin, within the rigorous framework of Gibbsian ensemble theory.

Theoretical Foundations of Thermostats

The Fluctuation-Dissipation Theorem and Ensemble Equivalence

A correct canonical ensemble must exhibit Gaussian kinetic energy fluctuations proportional to (Nf kB T^2)/2, where N_f is the number of degrees of freedom. This stems from the equipartition theorem. A thermostat's ability to reproduce these correct fluctuations is a key metric of its fidelity to Gibbs' canonical ensemble.

Extended Lagrangian vs. Stochastic Approaches

Thermostats can be classified by their methodological approach:

- Extended Lagrangian (Deterministic): Introduces additional degrees of freedom (a "thermal reservoir") into the system's Hamiltonian. Nosé-Hoover is the paradigmatic example.

- Stochastic: Applies random forces and damping to particles, mimicking collisions with an implicit bath. The Langevin thermostat is the prime example.

- Velocity Scaling (Ad-hoc): Empirically adjusts velocities to drive the temperature toward a target. Berendsen is the most common variant.

In-Depth Thermostat Analysis

Berendsen Thermostat

Protocol: The Berendsen thermostat couples the system to an external heat bath with a characteristic coupling constant τT. The velocities are scaled at each step by a factor λ:

λ = [1 + (Δt/τ_T) * (T_target / T_current - 1)]^(1/2)

Where Δt is the timestep. A strong coupling (small τT) drives temperature quickly to the target but can artificially suppress fluctuations.

Theoretical Context: It is a proportional feedback controller. It does not derive from a Hamiltonian and generates a dynamics that does not strictly obey the canonical ensemble distribution, leading to incorrect energy fluctuations.

Nosé-Hoover Thermostat

Protocol: Introduces a fictitious degree of freedom (s, with mass Q) representing the heat bath. The equations of motion become:

dp_i/dt = F_i - ζ p_i

dζ/dt = (1/Q) [∑_i (p_i^2 / (2 m_i)) - (N_f k_B T_target)]

Here, ζ is a friction coefficient that dynamically evolves. The parameter Q (the "thermostat mass") determines the coupling strength; a large Q leads to slow, weak coupling.

Theoretical Context: It is an extended Lagrangian method. For a single harmonic oscillator, it can fail to ergodically sample the canonical distribution. This led to the development of Nosé-Hoover Chains, where multiple thermostats are chained to ensure proper ergodicity.

Langevin Thermostat

Protocol: Adds two terms to the standard equations of motion: a friction force and a random force.

m_i dv_i/dt = F_i - γ m_i v_i + √(2 γ m_i k_B T_target / Δt) R(t)

Here, γ is the friction coefficient (in ps⁻¹ or similar), and R(t) is a Gaussian white noise process with zero mean and unit variance. The magnitude of the random force is dictated by the fluctuation-dissipation theorem to ensure correct sampling.

Theoretical Context: A pure stochastic approach. It provides strong temperature control and guaranteed canonical sampling for well-chosen γ. However, it perturbs Newtonian dynamics significantly, making it less suitable for studying dynamical properties like diffusion constants at high γ values.

Quantitative Comparison Table

| Property | Berendsen Thermostat | Nosé-Hoover Thermostat | Langevin Thermostat |

|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Ad-hoc velocity scaling | Extended Hamiltonian (Deterministic) | Stochastic differential equation |

| Generates Canonical (NVT) Ensemble? | No (suppresses fluctuations) | Yes (with chains for ergodicity) | Yes |

| Dynamical Properties | Artificially altered | Preserves dynamics well (for short chains) | Altered depending on γ |

| Key Control Parameter | Coupling time constant τ_T | Thermostat mass Q / Chain length | Friction coefficient γ |

| Temperature Stability | Very strong, fast relaxation | Good, with correct fluctuations | Very strong, fast relaxation |

| Computational Cost | Very low | Low (single) to Moderate (chains) | Low to Moderate |

| Typical Use Case | Equilibration only | Production runs (NVT/NPT) | Equilibration; solvent damping; implicit solvent |

Table 1: Summary comparison of key thermostat properties for NVT stability.

Experimental Protocols for Validation

Protocol 1: Measuring Kinetic Energy Fluctuations

- System Setup: Simulate a standard system (e.g., box of TIP3P water, 216 molecules) for 1 ns after equilibration using each thermostat.

- Parameters: Use recommended parameters: Berendsen (τ_T = 0.1 ps), Nosé-Hoover (Q corresponding to τ ~100 fs, chain length 3-5), Langevin (γ = 1-5 ps⁻¹).

- Data Collection: Record the instantaneous temperature (kinetic energy) every 1 fs.

- Analysis: Calculate the standard deviation of the temperature time series. Compare to the theoretical value: σT = Ttarget * sqrt(2 / N_f).

Protocol 2: Radial Distribution Function (RDF) Test

- System: Simulate a simple liquid (e.g., Argon) at its triple point.

- Simulation: Run three independent 500 ps NVT simulations, one with each thermostat.

- Analysis: Compute the O-O RDF for water or the Ar-Ar RDF. A correct canonical ensemble should produce identical structural properties. Deviations in the first solvation shell peak height indicate improper sampling.

Protocol 3: Ergocity Test for a Harmonic Oscillator

- System: Simulate a single classical harmonic oscillator with known frequency ω.

- Simulation: Run very long (10^7 steps) trajectories using single Nosé-Hoover and Nosé-Hoover Chain thermostats.

- Analysis: Plot the probability distribution of the oscillator's position and momentum. Compare to the theoretical Boltzmann distribution. A single Nosé-Hoover thermostat will show a distorted, non-ergodic distribution.

Visualization of Thermostat Logic and Workflow

Title: Decision Workflow for Selecting an NVT Thermostat

Title: Nosé-Hoover Chain Coupling Schematic

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function in Thermostat Validation & Use |

|---|---|

| TIP3P Water Model | Standard solvent system for testing thermostat-induced structural artifacts via Radial Distribution Functions (RDF). |

| Langevin Damping Constant (γ) | A key "reagent" parameter. Low γ (0.1-1 ps⁻¹) minimizes dynamical perturbation; high γ (5-10 ps⁻¹) provides strong temperature control for heavy atoms or equilibration. |

| Nosé-Hoover Chain Length | A numerical reagent. Length of 3-5 is typical for molecular systems to ensure ergodic sampling of the canonical ensemble. |

| Thermostat Mass (Q) / Time Constant (τ) | Determines the response time of the Nosé-Hoover thermostat. Must be matched to system vibrational timescales. |

| Reference Data (Theoretical σ_T) | Used as a benchmark to validate the correctness of kinetic energy fluctuations generated by the thermostat. |

| Harmonic Oscillator Test System | A minimal "reagent" system for diagnosing ergodicity failures in deterministic thermostats like basic Nosé-Hoover. |

In the framework of Molecular Dynamics (MD) research, the theoretical underpinnings of Boltzmann statistics and Gibbs ensemble theory dictate that to sample from the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble, a system must be coupled to both a thermal bath and a pressure bath. This coupling ensures the system explores microstates with probabilities proportional to exp[-(E + PV)/k_B T], where the pressure, P, becomes a controlled variable. Barostats are the algorithmic realization of this pressure coupling, essential for simulating biological and materials systems under realistic experimental conditions. This guide provides a technical dissection of two foundational barostats: the extended-Lagrangian Parrinello-Rahman method and the simpler, non-Hamiltonian Berendsen scheme.

Theoretical Foundation: From Gibbs Ensemble to Algorithmic Coupling

The NPT ensemble, formalized by Gibbs, is defined by fixed particle number (N), pressure (P), and temperature (T). In MD, achieving this requires modifying the equations of motion. While thermostats scale velocities, barostats dynamically adjust the simulation cell's dimensions and shape. The core challenge is to apply a defined external pressure while correctly accounting for the virial contributions from interatomic forces, thereby generating correct ensemble averages.

The Barostat Toolkit: Berendsen vs. Parrinello-Rahman

Berendsen Barostat: A Scaled Relaxation Method

The Berendsen barostat is a first-order pressure coupling scheme designed to exponentially relax the system pressure to a target value. It is not derived from an extended Lagrangian and does not rigorously generate the NPT ensemble, but it is efficient for equilibration.

Algorithm: The simulation cell vectors are scaled by a factor μ at each step:

μ = [1 + (Δt / τP) * (Ptarget - P_instantaneous) / compressibility]^{1/3}

where τ_P is the pressure relaxation time constant, Δt is the time step, and compressibility is the system's isotropic compressibility.

Protocol for Implementation:

- Compute Instantaneous Pressure: At each MD step, calculate the internal pressure (P_inst) from the virial and kinetic energy tensors.

- Calculate Scaling Factor: For isotropic coupling, compute μ using the formula above. For anisotropic coupling, a diagonal matrix μ_ij is used.

- Scale Coordinates and Box Vectors: Multiply all particle positions and the simulation cell vectors by μ.

- Velocity Correction: Scale particle velocities by μ^{-1} to avoid streaming flow artifacts.

Parrinello-Rahman Barostat: An Extended Lagrangian Method

The Parrinello-Rahman method introduces the simulation cell vectors as dynamic variables with associated fictitious masses, creating a fully Hamiltonian extended system. It correctly samples the NPT ensemble.

Algorithm: The equations of motion for a particle's scaled coordinates s and the cell vectors h (represented as a matrix) are: mi s̈i = Fi - mi G^{-1} Ġ ṡi W ḧ = ( Π - Ptarget * V * I ) * σ where G = h^T h, W is the fictitious cell mass, Π is the internal pressure tensor, V is cell volume, I is identity, and σ is related to the external stress tensor.

Protocol for Implementation:

- Define Cell Mass: Choose W (e.g., W = (Nf kB T τ_P^2) / (3V β) for isotropic), where β is compressibility.

- Integrate Extended System: Use a symplectic integrator (e.g., velocity Verlet) to update both particle positions/momenta and cell vectors/momenta simultaneously.

- Compute Pressure Tensor: Use the full virial expression including long-range corrections.

- Apply Constraints: For anisotropic simulations, apply symmetry constraints to h to maintain desired cell geometry.

Quantitative Comparison of Barostat Properties

Table 1: Core Algorithmic Properties of Berendsen and Parrinello-Rahman Barostats

| Property | Berendsen Barostat | Parrinello-Rahman Barostat |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Ad-hoc scaling; Non-Hamiltonian | Extended Lagrangian; Hamiltonian |

| Ensemble Produced | Approximate NPT (not rigorous) | Correct NPT (rigorous) |

| Control Variable | Pressure (relaxation to target) | Pressure (dynamic variable) |

| Key Parameter | Relaxation time constant (τ_P) | Fictitious cell mass (W) |

| Fluctuations | Artificially damped; incorrect | Preserves natural volume fluctuations |

| Computational Cost | Low (simple scaling) | Higher (extra degrees of freedom) |

| Primary Use Case | System equilibration, quick relaxation | Production runs for ensemble averages |

| Anisotropic Cell | Possible, but simplistic | Natural implementation with shape fluctuations |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for NPT Simulations

Table 2: Key Software and Analysis Components for Barostat Implementation

| Item | Function | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| MD Engine with NPT Support | Software framework implementing barostat equations of motion. | GROMACS, NAMD, LAMMPS, OpenMM, AMBER. |

| Pressure Calculation Module | Computes instantaneous pressure tensor from virial/kinetic energy. | Critical for accuracy; must include all force terms (bonded, non-bonded, long-range). |

| Parameter Set (Force Field) | Defines interatomic potentials and partial charges. | CHARMM36, AMBER ff19SB, OPLS-AA; must be validated for condensed-phase properties. |

| Solvation Box & Ions | Provides realistic electrostatic and steric environment. | TIP3P/SPC/E water models; ion parameters matching force field. |

| Thermostat | Couples system to temperature bath alongside barostat. | Nosé-Hoover, Langevin, or velocity rescaling thermostats combined with barostat. |

| Trajectory Analysis Suite | Analyzes volume, density, pressure fluctuations, and properties. | VMD, MDAnalysis, GROMACS tools; calculates fluctuation-derived compressibility. |

| Long-Range Electrostatics | Handles non-bonded interactions beyond cut-off. | Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) or PPPM; essential for correct virial/pressure. |

Experimental Protocol: Running an NPT Equilibration and Production Simulation

Workflow:

- Initial Minimization: Energy minimize a solvated system using steepest descent/conjugate gradient.

- NVT Equilibration (100 ps): Hold volume constant, heat system to target T using a thermostat (e.g., velocity rescaling). Apply position restraints on solute.

- NPT Equilibration (1-5 ns): Apply both thermostat and barostat. Use Berendsen barostat (τ_P = 1-2 ps) with position restraints to relax solvent density gently.

- NPT Production (≥100 ns): Switch to Parrinello-Rahman barostat (W chosen appropriately, τ_P ~ 4-6 ps). Remove all restraints. Save trajectory for analysis.

- Analysis: Monitor time series of box volume, density, and pressure. Check for drift. Compute average density and compressibility from fluctuations.

Title: NPT Simulation Protocol Workflow

Visualizing Barostat Dynamics and Coupling

Title: Barostat Feedback Control Loop

In conclusion, the choice between the Berendsen and Parrinello-Rahman barostats is dictated by the simulation stage and the required statistical rigor. Berendsen's method serves as a practical tool for rapid equilibration within the broader Gibbs ensemble framework, while Parrinello-Rahman is indispensable for deriving thermodynamically valid ensemble averages, ultimately fulfilling the promise of Boltzmann-weighted sampling in the NPT ensemble for drug discovery and materials science.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a computational technique that numerically solves Newton's equations of motion for a system of atoms, providing a time-evolutionary trajectory. The physical legitimacy of extracting equilibrium properties and ensemble averages from such deterministic trajectories is rooted in the ergodic hypothesis, which posits that the time average of an observable over a sufficiently long trajectory equals its ensemble average. This work is framed within the foundational statistical mechanics theories of Boltzmann and Gibbs. The Boltzmann distribution dictates the probability of finding a system in a particular microstate at a constant temperature (NVT ensemble). Gibbs' extension to the canonical, isothermal-isobaric (NPT), and grand canonical ensembles provides the framework for modeling biological systems under standard laboratory conditions (constant particle number, pressure, and temperature). A standard protein-ligand MD protocol aims to generate a thermodynamically representative ensemble of configurations from which binding affinities, conformational dynamics, and interaction mechanisms can be inferred, directly leveraging these core statistical mechanical principles.

Core Protocol: A Step-by-Step Technical Guide

This guide assumes a prepared, parameterized protein-ligand complex (e.g., from docking). The workflow follows a sequential minimization and equilibration strategy to gradually relax the system before production.

System Preparation and Solvation

Objective: Place the solute in a physiologically relevant aqueous environment with appropriate ions to neutralize charge and mimic ionic strength.

Detailed Methodology:

- Solvent Box Placement: Center the protein-ligand complex in a predefined periodic boundary condition (PBC) box. Common choices include:

- Truncated Octahedron: Maximizes volume for a given cutoff distance, computationally efficient.

- Rectangular/Cubic: Simplest, but may require more water molecules for the same cutoff.