Molecular Dynamics Force Fields: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a systematic comparison of molecular dynamics (MD) force fields, essential tools for simulating biomolecular systems in drug discovery.

Molecular Dynamics Force Fields: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of molecular dynamics (MD) force fields, essential tools for simulating biomolecular systems in drug discovery. We explore the foundational principles of Class I, II, and III force fields, including additive and polarizable models like AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS, and Drude. The guide details methodological considerations for simulating proteins, intrinsically disordered regions, and protein-ligand complexes, supported by benchmarks against experimental data. We further address common challenges and optimization strategies, culminating in a validation framework to empower researchers in selecting and applying the most accurate force fields for their specific biomedical applications, from target characterization to lead optimization.

Understanding Force Fields: The Engine of Molecular Dynamics Simulations

In computational chemistry and biology, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a crucial tool for investigating the structural and dynamic properties of biomolecules at the atomic level. The predictive power of these simulations hinges on the accuracy of the underlying molecular mechanics force fields, which are empirical mathematical models that describe the potential energy of a system as a function of its atomic coordinates [1]. Unlike quantum mechanical methods that explicitly treat electrons, force fields utilize a "ball and spring" approximation where atoms are represented as spheres and bonds as springs, significantly reducing computational cost while enabling the simulation of large systems over biologically relevant timescales [1] [2]. The energy calculations performed by these force fields form the physical basis for simulating atomic motions and predicting thermodynamic properties, playing a critical role in applications ranging from drug discovery to materials science [3] [4].

Biomolecular force fields are generally categorized into different classes based on their complexity. Class 1 force fields, which include widely used versions like AMBER, CHARMM, and OPLS-AA, employ simple harmonic approximations for bonded terms and pairwise additive approximations for non-bonded interactions [2]. Class 2 force fields incorporate more sophisticated anharmonic terms and cross-terms that account for coupling between different internal coordinates, with examples including MMFF94 [1] [2]. The more advanced Class 3 force fields, such as AMOEBA and DRUDE, explicitly include polarization effects and other electronic phenomena, providing greater accuracy at increased computational expense [2]. This review will focus primarily on the components of Class 1 force fields, which remain the most widely used in biomolecular simulations today.

Core Mathematical Components of a Force Field

The total potential energy ( U_{\text{total}} ) of a molecular system in a typical Class 1 force field is calculated as the sum of bonded and non-bonded interaction terms [2]. The canonical mathematical representation is:

[ U{\text{total}} = \sum{\text{bonds}} U{\text{bond}} + \sum{\text{angles}} U{\text{angle}} + \sum{\text{dihedrals}} U{\text{dihedral}} + \sum{\text{non-bonded}} U_{\text{non-bonded}} ]

Each term in this equation represents a specific type of atomic interaction, with the bonded terms maintaining molecular connectivity and geometry, while the non-bonded terms capture intermolecular forces and interactions between atoms that are not directly bonded. The precise functional forms and parameters for these energy terms vary between different force field families but share common underlying physical principles [2].

Bonded Interaction Terms

Bonded interactions describe the energy associated with the covalent bond structure of molecules and include terms for bond stretching, angle bending, and dihedral torsions. These terms collectively maintain the structural integrity of molecules during simulations.

Bond Stretching: This term describes the energy required to stretch or compress a covalent bond from its equilibrium length. It is typically modeled using a harmonic potential approximating Hooke's law: [ U{\text{bond}} = kb(r{ij} - r0)^2 ] where ( kb ) is the bond force constant, ( r{ij} ) is the distance between atoms ( i ) and ( j ), and ( r_0 ) is the equilibrium bond length [2]. This harmonic approximation works well at moderate temperatures but becomes less accurate under extreme stretching.

Angle Bending: This term represents the energy associated with bending the angle between three sequentially bonded atoms from its equilibrium value. Like bond stretching, it typically employs a harmonic potential: [ U{\text{angle}} = k\theta(\theta{ijk} - \theta0)^2 ] where ( k\theta ) is the angle force constant, ( \theta{ijk} ) is the angle formed by atoms ( i ), ( j ), and ( k ), and ( \theta_0 ) is the equilibrium angle [2]. The force constants for angle bending are typically about five times smaller than those for bond stretching.

Torsion (Dihedral) Angles: This term describes the energy associated with rotation around a central bond connecting four sequentially bonded atoms. Unlike bond and angle terms, dihedral potentials are periodic and are typically modeled using a cosine series: [ U{\text{dihedral}} = k\phi(1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta)) ] where ( k_\phi ) is the dihedral force constant, ( n ) is the periodicity (number of minima/maxima in a 360° rotation), ( \phi ) is the dihedral angle, and ( \delta ) is the phase shift angle [2]. Multiple periodic functions are often summed to accurately reproduce complex rotational energy profiles, such as cis/trans and trans/gauche energy differences [2].

Improper Torsions: This specialized term enforces planarity in molecular structures (e.g., aromatic rings, peptide bonds) and is often modeled with a harmonic function: [ U{\text{improper}} = k\phi(\phi - \phi0)^2 ] where ( \phi ) is the angle between planes defined by three atoms bonded to a central atom and ( \phi0 ) is the equilibrium value, typically 0° or 180° [2].

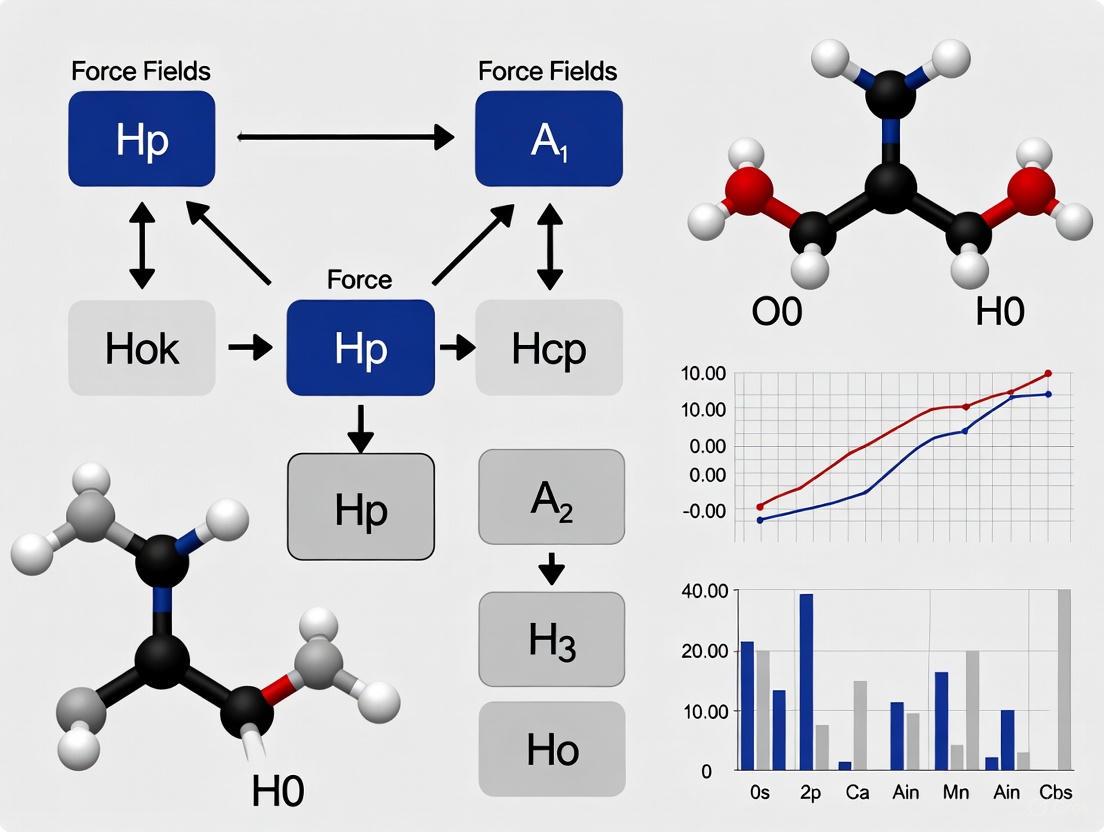

The following diagram illustrates the relationships between these primary bonded interactions in a molecular system:

Non-Bonded Interaction Terms

Non-bonded interactions describe forces between atoms that are not directly connected by covalent bonds, including both repulsive and attractive interactions. These terms are computationally intensive as they must be calculated for all pairs of atoms within a specified cutoff distance.

Van der Waals Interactions: These short-range forces include both attractive (London dispersion) and repulsive (Pauli exclusion) components. The most common model is the Lennard-Jones 12-6 potential: [ V_{\text{LJ}}(r) = 4\epsilon\left[\left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{6}\right] ] where ( \epsilon ) is the potential well depth, ( \sigma ) is the finite distance where the potential is zero, and ( r ) is the interatomic distance [2]. The ( r^{-12} ) term describes strong repulsive forces at short distances, while the ( r^{-6} ) term models weaker attractive forces. Some force fields employ the Buckingham potential, which replaces the repulsive ( r^{-12} ) term with an exponential function for a more realistic description of electron density, though it carries a risk of numerical instability at very short distances [2].

Electrostatic Interactions: These long-range forces between charged atoms are described by Coulomb's Law: [ V{\text{Elec}} = \frac{qi qj}{4\pi\epsilon0 \epsilonr r{ij}} ] where ( qi ) and ( qj ) are the partial atomic charges, ( \epsilon0 ) is the vacuum permittivity, ( \epsilonr ) is the relative dielectric constant, and ( r_{ij} ) is the distance between atoms [2]. In additive force fields, these interactions are calculated using fixed partial charges assigned to each atom, while polarizable force fields employ more sophisticated models to account for electronic polarization.

Combining Rules: To avoid parameterizing every possible atomic pair combination, force fields use combining rules to calculate interaction parameters between different atom types. Common approaches include:

- Lorentz-Berthelot: ( \sigma{ij} = \frac{\sigma{ii} + \sigma{jj}}{2} ), ( \epsilon{ij} = \sqrt{\epsilon{ii} \times \epsilon{jj}} ) (Used in CHARMM, AMBER) [2]

- Geometric Mean: ( \sigma{ij} = \sqrt{\sigma{ii} \times \sigma{jj}} ), ( \epsilon{ij} = \sqrt{\epsilon{ii} \times \epsilon{jj}} ) (Used in OPLS) [2] Different force fields require specific combining rules, and incorrect application can lead to inaccurate simulation results [2].

Treatment of 1-4 Interactions: A specialized case involves atoms separated by exactly three bonds (1-4 interactions). Traditional force fields employ a combination of torsional terms and empirically scaled non-bonded interactions, but recent approaches demonstrate that bonded coupling terms alone can more accurately model these interactions while improving parametrization and transferability [5].

The diagram below summarizes the key non-bonded interactions and their characteristics:

Experimental Benchmarking of Force Field Performance

Comparative Methodologies

Evaluating force field accuracy requires rigorous benchmarking against experimental data. Key methodologies include:

Thermodynamic Property Analysis: Calculating properties like density, shear viscosity, and free energy of solvation across temperature ranges and comparing with experimental measurements [3]. For example, density calculations typically employ large systems (e.g., 3375 molecules) in multiple cubic unit cells to balance fluctuations and computational cost [3].

NMR Data Comparison: Computing order parameters (S²) of backbone N-H bond vectors from MD simulations and comparing with heteronuclear Overhauser effect measurements from NMR spectroscopy [6] [7]. This provides quantitative assessment of how well force fields reproduce protein dynamics.

Structural Stability Tests: Running extended MD simulations of folded proteins and measuring structural drift using root mean square displacement (RMSD) of backbone atoms and distances between catalytic residues [7] [8]. This evaluates the force field's ability to maintain native folds.

Conformational Analysis: Comparing force field predictions of relative energies and geometries of different molecular conformations against quantum mechanical calculations or experimental data [1].

Principal Component Analysis (PCA): Comparing essential subspaces sampled by different force fields to quantify overlap in conformational sampling beyond direct experimental comparison [7].

The following workflow illustrates a comprehensive force field benchmarking methodology:

Quantitative Performance Comparison of Common Force Fields

Extensive benchmarking studies have revealed significant differences in how various force fields reproduce experimental observables. The table below summarizes key findings from recent comparative studies:

Table 1: Performance comparison of common biomolecular force fields across different systems and properties

| Force Field | Test System | Key Performance Metrics | Comparison Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAFF | Diisopropyl ether (DIPE) membranes | Density, shear viscosity | Similar to OPLS-AA/CM1A; accurately reproduces density and viscosity over 243-333 K | [3] |

| OPLS-AA/CM1A | Diisopropyl ether (DIPE) membranes | Density, shear viscosity | Similar to GAFF; good agreement with experimental density and viscosity | [3] |

| CHARMM36 | Diisopropyl ether (DIPE) membranes | Density, shear viscosity | Underestimates density by 2-4%; overestimates viscosity by factor of 2-3 | [3] |

| COMPASS | Diisopropyl ether (DIPE) membranes | Density, shear viscosity | Underestimates density by 2-4%; overestimates viscosity by factor of 2-3 | [3] |

| OPLS-AA | SARS-CoV-2 PLpro protein | Structural stability, native fold maintenance | Superior performance in maintaining catalytic domain folding in long simulations | [8] |

| CHARMM27 | SARS-CoV-2 PLpro protein | Structural stability, native fold maintenance | Showed local unfolding of N-terminal segment in longer simulations | [8] |

| AMBER03 | Ubiquitin, Protein GB3 | NMR order parameters, conformational sampling | Intermediate agreement with NMR data; distinct conformational ensemble | [7] |

| AMBER ff99SB-ILDN | Ubiquitin, Protein GB3 | NMR order parameters, conformational sampling | Good agreement with NMR data; similar ensemble to CHARMM22* | [7] |

| ZAFF | Zinc-finger proteins | NMR-derived order parameters | Accurately reproduces dynamic behavior of zinc-binding proteins | [6] |

| MMFF94 | Small organic molecules | Conformational energies, geometries | Consistently strong performance for organic molecule conformations | [1] |

Table 2: Performance of force fields for specific molecular properties and systems

| Molecular System | Best Performing Force Fields | Key Experimental Validation | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ether-based liquid membranes | GAFF, OPLS-AA/CM1A | Density, shear viscosity, interfacial tension with water | [3] |

| Small organic molecules | MMFF94, MM2, MM3 | Conformational energies compared to QM calculations | [1] |

| Zinc-binding proteins | ZAFF, NBFF | Backbone N-H order parameters from NMR | [6] |

| Stable folded proteins | AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, CHARMM22* | NMR residual dipolar couplings, scalar couplings | [7] |

| SARS-CoV-2 PLpro | OPLS-AA (with TIP3P water) | Backbone RMSD, catalytic residue distance | [8] |

Successful implementation of molecular dynamics simulations with biomolecular force fields requires specialized tools and resources. The following table outlines key components of the computational scientist's toolkit:

Table 3: Essential resources and methodologies for force field applications and validation

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| MD Simulation Software | GROMACS, NAMD, AMBER, OpenMM, LAMMPS | Software packages that implement force field mathematics to perform molecular dynamics simulations |

| Force Field Parameter Sets | AMBER (ff19SB, ff14SB), CHARMM (CHARMM36), OPLS-AA, GAFF | Specific parameter files defining bonded and non-bonded terms for different molecule classes |

| Validation Methodologies | NMR comparison, thermodynamic property calculation, conformational analysis | Protocols for assessing force field accuracy against experimental or QM reference data |

| System Preparation Tools | PACKMOL, CHARMM-GUI, tLEaP | Utilities for building complex molecular systems, solvation, and ion addition |

| Specialized Force Fields | ZAFF (zinc-AMBER), Lipid17 (lipids), Glycam (carbohydrates) | Force fields parameterized for specific molecular classes or metal ions |

| Analysis Utilities | MDAnalysis, VMD, CPPTRAJ | Software tools for analyzing simulation trajectories and calculating properties |

| Water Models | TIP3P, TIP4P, TIP5P, SPC | Specific water models designed to work with different force fields [8] |

| Benchmarking Datasets | Protein Data Bank structures, thermodynamic databases | Experimental data for validating force field performance |

Biomolecular force fields, with their core components of bonded and non-bonded terms, provide the fundamental theoretical framework for molecular dynamics simulations. The bonded terms—bond stretching, angle bending, dihedral torsions, and improper torsions—maintain molecular structure and define internal flexibility. The non-bonded terms—van der Waals and electrostatic interactions—capture intermolecular forces and are computationally demanding due to their long-range nature and extensive pairwise calculations.

Comprehensive benchmarking studies reveal that force field performance is highly system-dependent. For ether-based liquid membranes, GAFF and OPLS-AA/CM1A demonstrate superior accuracy in reproducing thermodynamic and transport properties [3]. In protein simulations, particularly for maintaining native folds in extended simulations, OPLS-AA shows notable stability [8]. For small organic molecules, the MM family of force fields (MMFF94, MM2, MM3) consistently provides accurate conformational energies and geometries [1]. Specialized systems, such as zinc-binding proteins, benefit from purpose-parameterized force fields like ZAFF [6].

The field continues to evolve with emerging trends including polarizable force fields that more accurately model electronic effects, machine learning approaches that offer quantum-chemical accuracy at lower computational cost, and automated parametrization tools that improve transferability [4] [9] [5]. Despite these advances, traditional additive force fields remain indispensable tools for biomolecular simulation, with their continued utility dependent on understanding their components, limitations, and appropriate applications through rigorous experimental validation.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, the force field defines the potential energy surface governing atomic interactions and is foundational to the accuracy and reliability of the simulation. Class I force fields, which use simple harmonic potentials for bonded interactions and Lennard-Jones plus Coulomb potentials for non-bonded interactions, represent the most widely used category in biomolecular simulation. Among these, AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, and OPLS have emerged as the established workhorses, each with unique parameterization philosophies, strengths, and limitations [10]. These force fields are routinely applied to study proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and drug-like molecules, providing critical insights into structural flexibility, molecular recognition, and dynamics at atomic resolution [11] [12].

This guide provides a comparative analysis of these four force fields, focusing on their performance across different chemical systems and physical properties. We synthesize findings from rigorous benchmarking studies to offer objective guidance for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the most appropriate force field for their specific molecular system and properties of interest.

Performance Comparison Across Systems

Extensive benchmarking studies have evaluated these force fields against experimental data and quantum mechanical calculations. Their relative performance varies significantly depending on the target properties and molecular systems studied.

Table 1: Overall Performance Summary Across Different Systems

| Force Field | Proteins & Peptides | Lipids & Membranes | Small Organic Molecules | Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Excellent for folded proteins [13]; some variants optimized for IDPs [14] | Limited native lipid parameters | Good with GAFF/GAFF2 [15] | Variable performance; tends to produce compact conformations [14] |

| CHARMM | Excellent with CMAP correction [13]; top-ranked for IDPs [14] | Excellent with dedicated lipid FF [13] [3] | Good with CGenFF [15] | Best overall performance for R2-FUS-LC region [14] |

| GROMOS | Good for proteins; united-atom efficiency [13] | Not recommended for lipids [13] | Limited small molecule coverage | Limited polar hydrogen representation [12] |

| OPLS | Good protein stability [13] | Good for ether-based membranes [3] | Excellent for liquid densities [10] | Less validated for IDPs |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics from Benchmarking Studies

| Force Field | Liquid Density RMSE (g/mL) | Solvation Free Energy RMSE (kJ/mol) | VLE Accuracy | Viscosity Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | ~0.04 (GAFF) [10] | 3.3-3.6 (GAFF2) [15] | Moderate [10] | Variable [3] |

| CHARMM | ~0.04 [10] | 4.0-4.8 (CGenFF) [15] | Good [10] | Good for DIPE [3] |

| GROMOS | Varies by version [13] | 2.9 (2016H66) [15] | Good [10] | Physically incorrect with twin-range cutoff [13] |

| OPLS | Excellent [10] | 2.9 (OPLS-AA) [15] | Good [10] | Excellent for DIPE [3] |

Methodologies for Key Benchmarking Experiments

To ensure reproducibility and proper interpretation of force field performance data, this section details common experimental protocols used in benchmarking studies.

Vapor-Liquid Coexistence Curves (VLCC) and Liquid Densities

Objective: Assess accuracy in predicting thermodynamic properties of pure liquids [10].

Protocol:

- System Setup: Create cubic simulation boxes containing 3375 molecules for sufficient statistical sampling [3].

- Ensemble Selection: Perform simulations in NVT-Gibbs ensemble for vapor-liquid coexistence or isobaric-isothermal ensemble for liquid densities at atmospheric pressure [10].

- Force Field Settings: Apply 12-6 Lennard-Jones potentials with point charges, using Lorentz-Berthelot mixing rules for unlike atoms [10].

- Cutoff Handling: Implement dual cutoffs (e.g., 10 Å non-bonded cutoff with analytical tail corrections) for efficient calculation of non-bonded interactions [10].

- Sampling Method: Utilize coupled-decoupled configurational-bias Monte Carlo within the MCCCS Towhee simulation program [10].

- Analysis: Compute coexistence liquid densities, vapor densities, and extrapolate critical temperature using density scaling law and law of rectilinear diameters [10].

Cross-Solvation Free Energy Calculations

Objective: Evaluate accuracy in predicting solute-solvent interactions across diverse chemical systems [15].

Protocol:

- Matrix Design: Construct N×N matrix of cross-solvation free energies for N different liquid molecules, considering each molecule as both solute and solvent [15].

- System Preparation: Solvate single solute molecules in boxes of solvent molecules, ensuring sufficient solvent shells (typically >1000 molecules total).

- Free Energy Calculation: Employ thermodynamic integration or free energy perturbation methods with multiple λ windows for alchemical transformations.

- Simulation Details: Use particle mesh Ewald for long-range electrostatics, 1 nm distance cutoffs, and 2 fs time steps with constraints on bonds involving hydrogen [15].

- Benchmarking: Compare results against experimental solvation free energies with root-mean-square error (RMSE) as primary metric [15].

Transport Properties of Liquid Membranes

Objective: Assess accuracy for membrane system properties including diffusion and viscosity [3].

Protocol:

- System Construction: Build initial configurations of pure solvents (e.g., diisopropyl ether) or water-solvent interfaces with thousands of molecules.

- Equilibration: Perform stepwise equilibration with decreasing position restraints on heavy atoms, followed by unrestrained equilibration until properties stabilize.

- Production Simulation: Run extended simulations (hundreds of nanoseconds) in NPT ensemble using Nosé-Hoover thermostat and barostat.

- Property Calculation:

- Density: Direct measurement from simulated system dimensions.

- Shear Viscosity: Calculate using Green-Kubo relation from autocorrelation of off-diagonal pressure tensor components.

- Interfacial Tension: Use Kirkwood-Buff method for interface systems.

- Diffusion Coefficients: Compute from mean squared displacement of molecules.

- Validation: Compare calculated properties with experimental measurements across temperature ranges [3].

Diagram 1: Force field selection methodology based on system type and target properties

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Force Field Implementation

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Force Field Compatibility | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | High-performance MD simulation | All major FFs [13] | Extreme performance; extensive analysis tools [13] |

| MCCCS Towhee | Monte Carlo/MD hybrid | Specialized for VLCC calculations [10] | Gibbs ensemble; configurational bias [10] |

| AMBER Package | MD simulation & analysis | Native AMBER FFs [11] | Integrated workflow; PMEMD |

| CHARMM | MD simulation & analysis | Native CHARMM FFs [3] | All-atom additive force fields |

| VOTCA | Systematic coarse-graining | Interface with GROMACS [13] | Boltzmann inversion; iterative optimization [13] |

Table 4: Experimental Data Sources for Validation

| Data Type | Source | Application in Force Field Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Vapor-Liquid Coexistence | NIST Chemistry WebBook | Thermodynamic property validation [10] |

| Solvation Free Energies | MNSOL database | Solvation matrix benchmarks [15] |

| Liquid Densities | Experimental literature (e.g., Meng et al.) | Density and pvT property validation [3] |

| Transport Properties | Viscosity/conductivity measurements | Shear viscosity validation [3] |

| NMR Chemical Shifts | BMRB database | IDP structural ensemble validation [14] |

Diagram 2: Comprehensive workflow for force field validation against experimental data

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that no single force field universally outperforms others across all systems and properties. OPLS-AA excels in reproducing liquid-phase thermodynamic properties, making it particularly suitable for organic solvents and pure liquids [10] [3]. CHARMM36 delivers robust performance across diverse biomolecular systems, including proteins, membranes, and notably intrinsically disordered proteins, where it currently shows superior performance [3] [14]. AMBER force fields, particularly when combined with the General Amber Force Field (GAFF), provide excellent coverage for drug-like molecules and proteins [15]. GROMOS offers computational efficiency through its united-atom approach but requires careful attention to its parameterization limitations, particularly for lipids and when using modern integration schemes [13].

Selection should be guided by the specific molecular system and target properties, with validation against available experimental data being an essential step in any research workflow. As force field development continues, the integration of machine learning approaches and more sophisticated parameterization methods promises to further enhance accuracy and transferability across the chemical space [11] [16].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are indispensable tools for investigating the physical properties of proteins, nucleic acids, and for designing new molecules and materials [17]. The potential-energy functions, or force fields, that underlie these simulations have evolved significantly to meet increasing demands for accuracy across diverse chemical environments. This evolution is categorized into classes that reflect their theoretical sophistication. Class I force fields, characterized by simple harmonic potentials for bonded terms and fixed point charges for electrostatics, have served as the workhorse for biomolecular simulations for decades [18]. While computationally efficient, their approximations—particularly the neglect of electronic polarization and anharmonicity—limit their accuracy in simulating phenomena where electronic response or bond dissociation is critical.

This guide focuses on Class II and Class III force fields, which introduce greater physical fidelity. Class II force fields incorporate anharmonicity and more complex coupling between internal coordinates, providing a more accurate description of potential energy surfaces, especially for distorted molecular geometries [19]. Class III force fields explicitly treat electronic polarization, allowing the electronic distribution to respond to a changing environment, which is crucial for modeling heterogeneous systems like interfaces, membranes, and protein-ligand complexes [17]. Understanding the capabilities, performance, and implementation requirements of these advanced force fields is essential for researchers aiming to push the boundaries of molecular simulation.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Differentiators

Core Energy Components and Their Advanced Forms

The total potential energy in a force field is a sum of several terms. Class II and III force fields enhance these components to achieve higher accuracy.

- Bonded Interactions: Class I force fields use harmonic potentials for bond stretching and angle bending. Class II force fields often replace these with more physically realistic Morse potentials for bonds (Figure 1A), which correctly describe bond dissociation [20]. They also introduce cross-coupling terms (e.g., bond-bond, bond-angle, and angle-torsion couplings) to capture the interdependence of internal coordinates [19].

- Nonbonded Interactions: Class I force fields use fixed point charges and Lennard-Jones potentials. Class III force fields employ sophisticated electrostatic models that include polarizability and often improve the representation of permanent electrostatics via atomic multipoles or off-center charge sites to model anisotropic effects [17].

Explicit Treatment of Polarizability

Polarizable force fields address a key limitation of fixed-charge models: the inability of the electrostatic model to respond to its environment. The three primary approaches are (Figure 2) [17]:

- Induced Dipole Model: Atoms are assigned a polarizability, allowing them to develop induced dipoles in response to the electric field from other particles.

- Drude Oscillator Model: Also known as the charge-on-spring model, this approach attaches a mobile Drude particle to an atom via a harmonic spring, forming an inducible dipole.

- Fluctuating Charge (FQ) Model: This model, based on electronegativity equalization, allows atomic charges to fluctuate to equalize the chemical potential across the system.

These models, while more computationally demanding, provide a more realistic description of interactions in environments with varying dielectric properties.

Incorporating Anharmonicity

Anharmonic potentials are crucial for accurately modeling bond dissociation and large-amplitude motions. The replacement of harmonic bond potentials with Morse potentials is a hallmark of this approach (Figure 1A) [20]. The Morse potential is described by: [ E{\text{bond}} = De \left(1 - e^{-\alpha(r-r0)}\right)^2 ] where ( De ) is the bond dissociation energy, ( r_0 ) is the equilibrium bond distance, and ( \alpha ) controls the width of the potential well. This function captures the anharmonic softening of the potential at larger bond displacements, which is absent in the simple harmonic model.

Comparative Analysis of Force Field Performance

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of Class I, II, and III force fields, highlighting their progressive complexity.

Table 1: Comparison of Force Field Classes by Characteristic and Capability.

| Feature | Class I (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS-AA) | Class II (e.g., IFF-R, MM3, CFF) | Class III (Polarizable FFs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Stretching | Harmonic potential | Morse potential & cross-coupling terms [20] [19] | Harmonic or anharmonic, depending on specific implementation |

| Electrostatics | Fixed point charges | Fixed point charges (typically) | Induced dipoles, Drude oscillators, or fluctuating charges [17] |

| Polarizability | Not included (implicit via parameterization) | Not included (implicit) | Explicitly included [17] |

| 1-4 Interactions | Scaled non-bonded interactions | Bonded coupling terms (in modern approaches) [19] | Treated via polarizable non-bonded terms |

| Bond Breaking | Not possible | Enabled via Morse potential [20] | Possible with reactive extensions |

| Computational Cost | Low | Moderate | High (2-5x Class I) |

Quantitative Performance in Benchmarking Studies

Performance varies significantly across force fields and the specific property being evaluated. The following table compiles key quantitative findings from the literature.

Table 2: Experimental Data and Performance Benchmarks for Different Force Field Types.

| Force Field Type / Name | Test System | Key Performance Metric | Result vs. Reference | Reference Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MM-type (Class II) | Small organic molecules | Conformational energies & geometries | Strong performance, close to QM reference [1] | QM calculations & experiment [1] |

| IFF-R (Class II) | Various materials (PAN, SWCNT, etc.) | Stress-strain curves up to failure | Accurately predicts failure & material properties [20] | Experiment & QM [20] |

| IFF-R (Class II) | General | Computational speed for reactive sim. | ~30x faster than ReaxFF [20] | Comparison to ReaxFF simulation time [20] |

| Polarizable (Class III) | Biomolecules | Electrostatic properties in varying environments | Superior to fixed-charge FFs in heterogeneous systems [17] | QM calculations & experiment [17] |

| Bonded 1-4 Model | Small molecules & Alanine Dipeptide | Potential Energy Surface (PES) reproduction | Sub-kcal/mol mean absolute error [19] | Ab initio QM calculations [19] |

Experimental Protocols and Validation

Parameterization of a Class II Morse Potential for Bond Breaking

The IFF-R (Reactive INTERFACE Force Field) provides a clear methodology for introducing anharmonicity and reactivity into a Class I force field [20]. The protocol involves a clean replacement of harmonic bond potentials with Morse potentials.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

- Initial State: Begin with a Class I harmonic force field that has been previously validated for structural and energetic properties under standard conditions (e.g., IFF, CHARMM, AMBER) [20].

- Bond Selection: Identify the specific covalent bond types (pairs of atom types) for which reactive dissociation will be enabled.

- Parameter Acquisition:

- Bond Dissociation Energy (Dₑ): This key parameter is obtained from experimental data or high-level quantum mechanical calculations (e.g., CCSD(T) or MP2) [20].

- Equilibrium Bond Length (r₀): This is retained from the equilibrium distance in the original harmonic potential.

- Alpha (α) Parameter: This parameter, which controls the width of the potential well, is initially fit to match the harmonic potential near the equilibrium geometry. It is subsequently refined to reproduce experimental vibrational frequencies from infrared or Raman spectroscopy [20]. The relationship ( \alpha = \sqrt{Kb / 2De} ) provides a starting point, where ( K_b ) is the harmonic force constant.

- Validation: The newly parameterized IFF-R must be validated to ensure it maintains the accuracy of the original force field for non-reactive properties. This includes checking mass densities, vaporization energies, and elastic moduli against experimental or high-level theoretical reference data [20].

Workflow for Simulating Bond Failure in a Polymer

Once parameterized, IFF-R can be used to simulate material failure.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

- System Preparation: Construct an atomistic model of the polymer (e.g., syndiotactic polyacrylonitrile, PAN) using the IFF-R parameters [20].

- Energy Minimization: Relax the initial structure to remove any high-energy steric clashes.

- Equilibration: Perform MD simulation in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble to bring the system to the desired temperature and density.

- Mechanical Test: Apply a constant uniaxial strain rate to the simulation box. The stress is calculated from the virial tensor.

- Reactive Dynamics: As strain increases, the Morse potentials allow bonds to stretch and ultimately break when the stress exceeds the bond strength. The simulation captures the cascade of bond failures leading to material fracture.

- Analysis: The stress-strain curve is plotted, and the failure point is identified. The atomic trajectory is analyzed to visualize the initiation and propagation of cracks.

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section lists essential resources and tools for researchers working with advanced force fields.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Force Field Development and Application.

| Item Name | Function/Benefit | Relevance to Class II/III FFs |

|---|---|---|

| Q-Force Toolkit [19] | Automated force field parameterization framework. | Systematically derives bonded coupling terms for Class II FFs and polarizable parameters. |

| REACTER Protocol [20] | Template-based method for simulating bond-forming reactions within MD. | Enables fully reversible chemistry in Class II reactive MD (IFF-R). |

| Martini Coarse-Grained FF [21] | A generic 4-to-1 mapping coarse-grained force field. | Often used in multi-scale approaches; polarizable version exists for water and lipids. |

| Ab Initio Data (QM) | Reference data from electronic structure calculations. | Essential for parameterizing and validating both Class II and III force fields [20] [19]. |

| Machine Learning Potentials [22] | ML models for interatomic potentials and polarizability tensors. | Used to capture complex anharmonic effects and accelerate PES exploration [22]. |

| AMOEBA Force Field [17] [19] | A prominent polarizable force field using atomic multipoles and induced dipoles. | A leading example of a Class III force field for biomolecules and materials. |

The adoption of Class II and III force fields represents a significant step toward greater predictive power in molecular simulations. Class II force fields, with their anharmonic potentials and sophisticated coupling terms, are uniquely suited for problems involving bond dissociation, material failure, and the accurate description of distorted molecular geometries. Class III polarizable force fields are essential for simulating systems where the electrostatic environment is heterogeneous, such as at biological interfaces, in membranes, or in mixed solvents.

The choice between these classes, and specific force fields within them, involves a trade-off between physical accuracy and computational cost. While Class II and III force fields are more demanding, advancements in algorithms, parameterization tools like Q-Force, and computing hardware are making them increasingly accessible. For research questions where the limitations of Class I force fields are a known bottleneck—such as in chemical reactivity, detailed spectroscopy, or interfacial phenomena—the investment in advanced force fields is not just beneficial, but necessary for achieving reliable, quantitative results.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are an indispensable tool in modern chemical research and drug development, providing atomistic resolution into biophysical processes. The accuracy of these simulations hinges entirely on the underlying force field—the mathematical model that defines the potential energy of a molecular system. For decades, the field has been dominated by fixed-charge models (e.g., AMBER, CHARMM, OPLS), which approximate electrostatic interactions using static, atom-centered point charges. While computationally efficient, these models intrinsically lack electronic polarization, the critical many-body effect whereby a molecule's electron density redistributes in response to its local electrostatic environment [23] [24].

To overcome this limitation, next-generation polarizable force fields have been developed, with the Drude oscillator and AMOEBA (Atomic Multipole Optimized Energetics for Biomolecular Applications) models representing two leading approaches [23] [25]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these frameworks, focusing on their fundamental methodologies, performance in experimental validation, and practical applications in drug discovery. The inclusion of explicit polarization offers a more accurate description of molecular interactions, which is crucial for modeling protein-ligand binding, ion solvation, and nucleic acid dynamics—all key areas in pharmaceutical development [26] [23].

Fundamental Principles and Methodologies

The Drude and AMOEBA models incorporate polarization through distinct physical representations and mathematical formalisms. The table below summarizes their core characteristics.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of the Drude and AMOEBA Force Fields

| Feature | Drude Oscillator Model | AMOEBA Model |

|---|---|---|

| Core Polarization Method | Charged harmonic oscillator (core-shell particle) [25] | Inducible atomic point dipole [23] |

| Electrostatic Representation | Atom-centered point charges [25] | Atomic multipoles (charge, dipole, quadrupole) [23] |

| Van der Waals Form | Typically Lennard-Jones [24] | Buffered 14-7 function [23] |

| Induction Scheme | Extended Lagrangian or self-consistent minimization [25] | Iterative, self-consistent field (SCF) induction [23] |

| Computational Cost | Lower than AMOEBA [23] | Higher than Drude; intermediate among polarizable FFs [23] |

The Drude Oscillator Model

In the Drude (or shell) model, polarization is represented by attaching a auxiliary charged particle (the "Drude oscillator" or "shell") to an atomic core via a harmonic spring [25]. This core-shell pair constitutes a polarizable atom. The displacement of the Drude particle from its core in an electric field creates an induced dipole moment. In molecular dynamics simulations, the Drude particles are often treated as dynamic variables with a fictitious mass, adiabatically decoupled from the physical atomic nuclei, allowing them to be propagated using an extended Lagrangian formalism [25].

The AMOEBA Polarizable Force Field

The AMOEBA force field adopts a more comprehensive approach. Its electrostatic model is based on atomic permanent multipoles, including charge, dipole, and quadrupole moments, which provide a superior description of molecular electrostatic potentials compared to simple point charges [23]. Polarization is handled through inducible atomic dipoles, where the dipole moment on each atom is proportional to the total electrostatic field at that atom's position, generated by both the permanent multipoles and the induced dipoles of all other atoms [26] [23]. An iterative procedure is required to achieve self-consistency for the induced dipoles. The AMOEBA potential energy function also includes a more complex valence terms with cross-coupling and a "softer" buffered 14-7 van der Waals potential [23].

Performance and Experimental Validation

A force field's value is determined by its accuracy in reproducing experimental observables. Both the Drude and AMOEBA models have undergone extensive validation across various chemical and biological systems.

Performance Benchmarking

The following table synthesizes quantitative data from key validation studies, highlighting the performance of each force field in critical benchmark areas.

Table 2: Experimental Validation and Performance Benchmarks

| Validation Metric | AMOEBA Performance | Drude Performance | Key Experimental Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA/RNA Duplex RMSD | ~2.0 Å from NMR [26] | Comparable stability [26] | NMR Structures [26] |

| Protein-Ligand Binding | Significant improvement over fixed-charge [23] | Improved accuracy [23] | ITC, Crystallography [23] |

| Small Molecule Thermodynamics | Excellent for structural & thermodynamic data [23] | Good agreement [23] | Solvation Free Energy [23] |

| Infrared Spectroscopy | Accurately reproduces nitrile vibrational shifts [27] | Suitable for spectroscopy [25] | IR Spectroscopy [27] |

| Computational Cost | Higher than Drude [23] | Lower than AMOEBA [23] | N/A |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To contextualize the data in Table 2, the methodologies for several key experiments are outlined below.

1. Nucleic Acid Structure Stability Simulation (AMOEBA) [26]

- Objective: Validate the ability to maintain native DNA/RNA structures and capture transitions.

- System Setup: Multiple DNA (e.g., Dickerson-Drew dodecamer) and RNA (duplexes, tetraloops) molecules were simulated. Systems were solvated in aqueous solution or water-ethanol mixtures.

- Simulation Protocol: Over 35 microseconds of total simulation time were performed using the TINKER software. Conditions were varied (e.g., 90% ethanol) to induce B- to A-form DNA transition.

- Validation Data: Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) was calculated against experimental NMR and X-ray crystal structures. Backbone dihedrals, sugar pucker, and groove geometries were analyzed.

2. Nitrile Vibrational Spectroscopy in Proteins (AMOEBA) [27]

- Objective: Test the accuracy of the force field in simulating local electric fields and H-bonding interactions.

- System Setup: A nitrile group was site-specifically incorporated into photoactive yellow protein, and local interactions were engineered via mutagenesis.

- Simulation Protocol: Extensive MD simulations were performed. The simulated electric fields at the nitrile site were correlated with its IR frequency.

- Validation Data: Experimental IR data and high-resolution X-ray crystal structures were used for direct comparison. The force field's ability to correlate with the nitrile's IR shift (blueshift) and electric field was assessed.

3. QM/MM Simulation with Polarizable Force Field (Drude) [25]

- Objective: Investigate the effect of MM polarization on reaction free energy barriers and properties.

- System Setup: Model systems like a water cluster, an oxygen vacancy in silica, and a zeolite-catalyzed reaction were prepared.

- Simulation Protocol: An extended Lagrangian QM/MM scheme was implemented. The Drude shells were treated as dynamic variables and propagated with a small fictitious mass, adiabatically decoupled from the nuclear degrees of freedom.

- Validation Data: Reaction free energy barriers and defect formation energies calculated with the QM/Drude-MM model were compared against those from fixed-charge QM/MM simulations and higher-level theoretical calculations.

Successful implementation of polarizable simulations requires a suite of specialized software tools and parameters.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Polarizable Simulations

| Tool/Resource | Function | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| TINKER | Software for molecular mechanics and dynamics [23] | Primary platform for AMOEBA simulations [26] [23] |

| CHARMM/OpenMM | Comprehensive simulation packages [23] | Support for Drude oscillator simulations [26] |

| ForceBalance | Automated parameter optimization tool [24] | Refines torsional and non-bonded parameters using QM and experimental data [24] |

| Gaussian 09 | Quantum chemistry software [26] | Generates target data (structures, electrostatic potentials) for force field parametrization [26] |

| Polarizable Ion Model (PIM) | A force field for molten salts [28] | Demonstrates application of polarizable principles beyond biomolecules [28] |

The transition from fixed-charge to polarizable force fields represents a generational shift in molecular simulation. Both the Drude oscillator and AMOEBA models offer demonstrable improvements in accuracy for a range of physicochemical properties, from nucleic acid structure to protein-ligand binding [26] [23]. The choice between them involves a trade-off between physical detail and computational expense.

The AMOEBA model, with its atomic multipole representation and induced dipole polarization, aims for high fidelity to ab initio quantum mechanical calculations and is particularly successful in areas where accurate electrostatics are critical [23] [27]. The Drude model offers a computationally less demanding path to include polarization, making it attractive for larger systems or longer time-scale simulations [23] [25].

For researchers in drug development, the adoption of polarizable force fields can provide more reliable insights into molecular recognition and binding, potentially improving the predictive power of structure-based drug design. As high-performance computing resources become more accessible, these advanced models are poised to move from specialized use to mainstream application, ultimately leading to a more robust and physically accurate computational toolkit for scientific discovery.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become indispensable tools in modern scientific research, particularly in drug discovery and materials science, where they provide atomistic insights into complex biological and chemical processes. The predictive accuracy of these simulations hinges critically on the quality of the underlying force fields—the mathematical functions and parameters that describe the potential energy of a molecular system. Among the most widely used all-atom, fixed-charge force fields in biomolecular simulations are CHARMM (Chemistry at HARvard Macromolecular Mechanics), AMBER (Assisted Model Building with Energy Refinement), and OPLS (Optimized Potentials for Liquid Simulations). While similarly successful in modeling condensed phase behavior, these force fields are distinguished by fundamentally different parameterization philosophies regarding target data, charge derivation methods, and treatment of non-bonded interactions. These philosophical differences create distinct strengths and limitations that can significantly influence simulation outcomes for specific chemical systems and physical properties. Understanding these core development principles is essential for researchers to select the most appropriate force field for their particular scientific questions, especially when modeling drug-receptor interactions, predicting solvation behavior, or simulating complex biological macromolecules.

Core Parameterization Philosophies and Methodologies

The development of CHARMM, AMBER, and OPLS force fields reflects distinct historical priorities and theoretical approaches to capturing molecular interactions. A comparative analysis of their core philosophies reveals how these priorities shape their modern implementations and applications.

Table 1: Core Philosophical Foundations of Major Biomolecular Force Fields

| Force Field | Primary Development Focus | Charge Derivation Philosophy | Parameterization Targets | Underlying Theoretical Presumption |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM/CGenFF | Biomolecular simulations, consistency with biomolecular force field | Reproduce QM-derived interaction energy with a water probe (HF/6-31G(d)) [29]. | Condensed phase properties, hydration free energies (HFE) [29]. | Captures condensed phase polarization effects explicitly via charge training [29]. |

| AMBER/GAFF | Accurate biomolecular structures and conformational energies | Fit to electrostatic potential (ESP) using AM1-BCC to reproduce HF/6-31G* gas-phase dipole moment [29]. | Conformational energies, gas-phase structures, vibrational spectra [30]. | Gas-phase polarization effects fortuitously represent condensed phase behavior [29]. |

| OPLS-AA | Accurate thermodynamic and bulk properties of liquids | Typically uses partial charges fitted to reproduce liquid-state properties or electrostatic potentials [31] [30]. | Heats of vaporization, liquid densities, solvation free energies [30]. | Optimized for condensed phase; prioritizes reproduction of experimental liquid properties. |

CHARMM Philosophy and Evolution

The CHARMM force field prioritizes consistency across different molecular classes and explicit modeling of condensed phase polarization effects. Its generalized version, CGenFF, extends this philosophy to drug-like small molecules. The defining characteristic of CHARMM's charge derivation is its parameterization to reproduce the quantum mechanical (QM) interaction energy between a water molecule and the target compound at the HF/6-31G(d) level. This approach is intended to explicitly capture the polarization effect a proximal water molecule would induce, making it inherently geared toward simulating solvated biomolecular systems [29]. The force field is trained on large, chemically diverse datasets to ensure transferability, with a strong emphasis on reproducing experimental hydration free energies (HFE) [29]. This focus on solvation and biomolecular consistency has made CHARMM a dominant force field in the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and their complexes with small molecules.

AMBER Philosophy and Evolution

The AMBER force field family, including its generalized small molecule counterpart GAFF (Generalized AMBER Force Field), is historically rooted in achieving high-fidelity representation of gas-phase molecular structures and conformational energies. Its charge derivation strategy relies on the AM1-BCC model, which aims to accurately reproduce the electrostatic surface potential (ESP) around a molecule calculated at the HF/6-31G* level in the gas phase [29]. The underlying presumption is that the overestimated gas-phase dipole moment fortuitously incorporates the polarization effects present in the condensed phase. A key tenet of the AMBER philosophy, particularly with the ff99 force field, was that using restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) charges would reduce the need for extensive torsional parameter corrections compared to models with more empirical charge derivation [30]. This philosophy results in a force field exceptionally well-regarded for the simulation of native biomolecular structures and conformational dynamics.

OPLS Philosophy and Evolution

The OPLS force field, particularly the all-atom OPLS-AA variant, is distinguished by its primary design goal: the accurate reproduction of experimental thermodynamic and bulk liquid properties. Unlike CHARMM and AMBER, which originated with a strong focus on biomolecular structure, OPLS was conceived with liquid simulations as a central target [30]. Its parameterization heavily prioritizes the experimental heats of vaporization, liquid densities, and free energies of solvation. Charge assignments in OPLS are typically derived to be consistent with these condensed-phase properties. Recent developments continue this trend; for instance, a 2025 refinement for organosulfur and organohalogen APIs involved deriving atomic point charges using the ChelpG methodology, with explicit inclusion of X-sites to mimic the σ-hole on iodine, and validated the parameters against experimental sublimation enthalpies and crystal lattice dimensions [31]. This empirical grounding in thermodynamic data makes OPLS a powerful tool for simulating solutions, pure liquids, and predicting solvation-related properties critical to drug design.

Comparative Performance in Experimental Validation

The theoretical differences in parameterization philosophies manifest as distinct performance profiles when these force fields are subjected to experimental validation. Benchmarking studies often reveal that while overall accuracy may be similar, systematic errors can be linked to specific functional groups based on each force field's training data and charge model.

Table 2: Performance Analysis by Functional Group and Property

| Force Field | Performance in Hydration Free Energy (HFE) Prediction | Performance in Structural Reproduction | Known Functional Group Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM/CGenFF | Generally accurate, but molecules with amine-groups are under-solubilized (more so than in GAFF) [29]. | Good reproduction of protein backbone structure in collagen triple helices, though some backbone dihedral deviations occur [32]. | Amine-groups lead to under-solubilization; Nitro-groups can cause over-solubilization [29]. |

| AMBER/GAFF | Generally accurate, but carboxyl groups are more over-solubilized than in CGenFF. Molecules with nitro-groups are under-solubilized [29]. | Evaluated for collagen structure; some force fields (e.g., ff99SB) showed large deviations from crystal structure data [32]. | Carboxyl groups lead to over-solubilization; Nitro-groups lead to under-solubilization [29]. |

| OPLS-AA | Designed for accurate liquid thermodynamics. Recent refinements show accurate prediction of sublimation enthalpies and unit cell dimensions for APIs [31]. | Good capacity to reproduce crystal structures of small molecule APIs, including organosulfur and organohalogen compounds [31]. | Performance for specific novel functional groups (e.g., σ-hole halogens) can require explicit parameterization with X-sites [31]. |

Performance in Predicting Solvation Thermodynamics

Hydration free energy (HFE) is a critical property in drug design, as it influences solubility, permeability, and binding affinity. A large-scale comparison of CGenFF and GAFF on over 600 molecules from the FreeSolv database revealed that while both are generally accurate, they exhibit systematic, chemically intuitive errors [29]. The study found that molecules containing nitro-groups are over-solubilized in CGenFF but under-solubilized in GAFF. Furthermore, amine-groups cause under-solubilization in both force fields, but this effect is more pronounced in CGenFF. Conversely, carboxyl groups are over-solubilized in both, with the effect stronger in GAFF [29]. These trends highlight the direct consequence of their differing charge models: CGenFF's water-probe approach versus GAFF's gas-phase ESP fitting. OPLS-AA, with its empirical foundation in liquid properties, is inherently designed to avoid such systematic deviations for common organic functional groups, though its performance on novel drug-like molecules may require continuous reparameterization, as evidenced by recent work on sulfur- and halogen-containing APIs [31].

Performance in Reproducing Structural Data

Accuracy in reproducing experimental structures, from small-molecule crystals to complex protein folds, is another key validation metric. A 2025 study evaluating force fields on collagen triple helices provided insights into their structural performance. The study found that the CHARMM22 family of force fields, along with CHARMM36, demonstrated a good capacity to reproduce the correct backbone structure of the collagen triple helix, although some deviations in backbone dihedrals were noted [32]. In contrast, certain AMBER force fields (e.g., ff99SB) showed larger deviations from crystal structure data [32]. For small-molecule crystal structures, the latest OPLS-style parameterizations have shown excellent performance. A newly developed all-atom force field for organosulfur and organohalogen APIs, based on an OPLS-AA framework with added dihedrals and σ-hole parameters, successfully reproduced experimental single crystal X-ray diffraction data and sublimation enthalpies [31]. This demonstrates OPLS-AA's robustness for modeling intricate crystal packing interactions, a property rooted in its parameterization against condensed-phase data.

Experimental Protocols for Force Field Validation

To ensure objectivity when comparing force fields, the scientific community relies on standardized computational protocols and benchmark experimental data. The methodologies cited in the performance tables represent some of the most rigorous approaches currently in use.

Alchemical Hydration Free Energy (HFE) Calculation Protocol

The accurate calculation of absolute HFE using alchemical free energy methods is a cornerstone of force field validation for solvation properties. The protocol implemented in the CHARMM program for benchmarking CGenFF and GAFF involves several key stages [29]:

- System Setup: A single solute molecule is placed in a cubic box of explicit TIP3P water molecules, with a minimum distance of 14 Å between the solute and any box edge. Periodic boundary conditions are applied.

- Alchemical Transformation: The solute is annihilated in both the aqueous phase and in vacuo using a thermodynamic cycle. This is managed by defining multiple "BLOCKs": BLOCK 1 contains all water molecules, BLOCK 2 is a DUMMY particle (with zero charge and Lennard-Jones parameters), and BLOCK 3 is the solute.

- Lambda Coupling: The non-bonded interactions (electrostatics and Lennard-Jones) of the solute are progressively turned off by scaling with a coupling parameter λ, which ranges from 0 (fully interacting) to 1 (fully annihilated). Simultaneously, the DUMMY particle's interactions are scaled on.

- Free Energy Calculation: Molecular dynamics simulations are run at multiple intermediate λ values. The free energy change for the annihilation in both solvent (ΔGsolvent) and vacuum (ΔGvac) is computed using advanced methods like the Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR). The absolute HFE is then obtained as ΔGhydr = ΔGvac - ΔG_solvent [29].

This protocol, particularly when automated through pipelines like those built in pyCHARMM, allows for the high-throughput, reproducible benchmarking of force fields across large chemical datasets [29].

Diagram 1: HFE calculation workflow. This diagram illustrates the standard alchemical free energy protocol for calculating hydration free energies, a key method for force field validation [29].

Solid-State and Structural Validation Protocol

Validation against solid-state data ensures force fields can reproduce experimental crystal structures and thermodynamic properties like sublimation enthalpy. The protocol for validating the recent OPLS-based force for APIs is exemplary [31]:

- Target Data Selection: Experimental sublimation enthalpies are determined using Calvet microcalorimetry, providing highly accurate thermodynamic data. Structural data is obtained from single crystal X-ray diffraction.

- Force Field Refinement: Missing dihedral parameters in the base OPLS-AA database are obtained by scanning potential energy surfaces (PES) at the MP2/aug-cc-pVDZ level of theory.

- Charge Modeling: Atomic point charges are derived using methods like ChelpG. For atoms like iodine, which exhibit an anisotropic charge distribution (σ-hole), extra positive charge sites (X-sites) are explicitly included in the model to correctly capture halogen bonding.

- Simulation and Comparison: MD simulations of the crystal structure are performed. The predicted unit cell dimensions and the calculated sublimation enthalpy (derived from the difference between the potential energy of the crystal and the gas phase) are directly compared to the experimental X-ray and calorimetry data.

This rigorous protocol ensures the force field is simultaneously accurate for both structural and energetic properties in the condensed phase.

To conduct force field comparisons and development, researchers rely on a standardized set of computational tools, datasets, and software. The following table details key resources that constitute the essential toolkit for work in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Force Field Comparison

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Research | Relevance to Force Field Development/Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| FreeSolv Database [29] | Experimental & Computational Dataset | A curated database of experimental and calculated hydration free energies for small molecules. | Serves as a primary benchmark for testing the accuracy of force field solvation predictions. |

| CHARMM Program [29] | MD Simulation Software | A versatile package for MD simulations, particularly strong in force field development and free energy calculations. | Used to implement alchemical HFE protocols and test CGenFF parameters. Interfaces with OpenMM and BLaDE for GPU acceleration. |

| pyCHARMM [29] | Python Integration Framework | A Python framework that embeds CHARMM's functionality, enabling workflow automation and integration with Python data science tools. | Facilitates the construction of automated pipelines for high-throughput force field benchmarking. |

| GROMACS [32] | MD Simulation Software | A high-performance MD package widely used for biomolecular simulations. | Commonly used for independent validation studies comparing force field performance on proteins and other biomolecules. |

| HF/6-31G(d) & HF/6-31G* [29] | Quantum Mechanical (QM) Method | A specific level of QM theory used for calculating target electrostatic properties. | HF/6-31G(d) is the target for CGenFF charge fitting. HF/6-31G* is the reference for GAFF's AM1-BCC charge model. |

| ChelpG & RESP [31] [30] | Charge Fitting Methods | Algorithms for deriving atomic partial charges from QM-calculated electrostatic potentials. | ChelpG was used in recent OPLS refinements [31]. RESP (Restrained ESP) is a standard method in the AMBER family [30]. |

Diagram 2: Force field development logic. This diagram shows the logical relationship from a force field's core philosophy to its final performance characteristics, highlighting the roots of systematic errors and strengths.

The comparative analysis of CHARMM, AMBER, and OPLS force fields reveals a landscape defined by complementary strengths rather than absolute superiority. The CHARMM force field, with its focus on reproducing QM-derived interaction energies with an explicit water probe, offers a theoretically grounded approach for simulating solvated biomolecular systems, though it can exhibit systematic errors with specific polar functional groups like amines. The AMBER force field family prioritizes accurate gas-phase structures and electrostatic potentials, making it a superb choice for conformational analysis, but its performance on solvation properties can be less consistent, particularly for molecules with nitro or carboxyl groups. The OPLS force field, empirically optimized for liquid-state thermodynamic properties, consistently demonstrates robust performance in predicting densities, heats of vaporization, and, as recent advances show, crystal structures of complex drug-like molecules. There is no universally "best" force field; the optimal choice is dictated by the specific scientific question, the chemical system under investigation, and the target properties of interest. Future force field development is likely to increasingly leverage machine learning and extensive automated benchmarking against large experimental datasets to transcend the limitations of these classical paradigms, creating more universally accurate and transferable models for computational science.

Selecting and Applying Force Fields in Biomedical Research

Choosing a Force Field for Folded Proteins vs. Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs)

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as a computational microscope, revealing atomic-level details of protein dynamics. However, a significant challenge persists in selecting force fields that accurately simulate both structured domains and intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) within the same protein. IDRs, which lack a stable three-dimensional structure and exist as dynamic conformational ensembles, comprise approximately 30% of the human proteome and play crucial roles in cellular signaling, regulation, and molecular recognition [33] [34]. Traditional force fields parameterized using data from folded, globular proteins often fail to capture the unique biophysical properties of IDPs, frequently producing overly compact structures and overestimating secondary structure propensity [35] [36] [37]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of modern force fields, evaluating their performance across both structured and disordered protein contexts using experimental data from nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), and other biophysical techniques.

Force Field Performance: Structured Domains vs. IDRs

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of force fields commonly used for simulating proteins containing both structured and disordered regions.

Table 1: Comparison of Force Fields for Folded Proteins and IDRs

| Force Field | Water Model | Performance with Folded Domains | Performance with IDRs | Key Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM36m [35] [14] | TIP3P/mTIP3P | Good structural stability | Good for global dimensions; variable with local propensity [38] [37] | NMR (chemical shifts, PRE, relaxation), SAXS, Rg |

| a99SB-disp [39] [38] | a99SB-disp | High accuracy | Excellent for multiple IDPs; good agreement with NMR/SAXS [39] | NMR, SAXS, ensemble reweighting |

| DES-amber [37] | TIP4P-D | Good structural stability | Best for subtle conformational changes and dynamics [37] | NMR relaxation, SAXS, helicity quantification |

| ff99SBws [37] | TIP4P/TIP4P/2005s | Good structural stability | Captures helicity trends but may overestimate them [37] | NMR, SAXS |

| CHARMM22* [35] [36] | TIP3P/TIP4P | May show instability in long simulations | Tends to produce overly compact conformations [35] | NMR chemical shifts, Rg, PRE |

| Martini3-IDP [40] | Martini Water | Good for large-scale dynamics | Improved Rg vs. experiment; good for condensates & membrane binding [40] | SAXS, Rg, phase separation |

Experimental Benchmarks and Key Methodologies

Rigorous validation against experimental data is crucial for assessing force field accuracy. The following experimental observables and protocols are central to benchmarking.

Primary Experimental Observables

- Radius of Gyration (Rg): A key metric of global compactness measured by SAXS. Force fields that over-stabilize intramolecular interactions yield underestimated Rg values [35] [40] [14].

- NMR Chemical Shifts: Sensitive reporters of local secondary structure propensity. Discrepancies between calculated and experimental shifts indicate inaccuracies in backbone dihedral sampling [35] [36].

- NMR Relaxation Rates: Probe picosecond-to-nanosecond dynamics, highly sensitive to force field and water model choice. Poor performance here indicates issues capturing conformational entropy and dynamics [35] [37].

- Residual Dipolar Couplings (RDCs) and Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement (PRE): Provide long-range structural restraints, validating transient intramolecular contacts in IDPs and domain positioning [35].

- Secondary Structure Propensity: Quantified from NMR data or MD trajectories using tools like DSSP, assessing a force field's ability to model transient helices, β-sheets, or polyproline II (PPII) structures [38] [14].

Integrative Structural Biology Protocols

A powerful approach involves using experimental data to refine computational models. A recent robust protocol uses maximum entropy reweighting to integrate atomistic MD simulations with extensive NMR and SAXS data [39].

Figure 1: Workflow for determining accurate conformational ensembles of IDPs by integrating molecular dynamics simulations with experimental data using a maximum entropy reweighting procedure [39].

Table 2: Essential Research Tools for Force Field Benchmarking

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Example Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| NMR Spectrometer | Experimental Instrument | Measures chemical shifts, RDCs, PREs, and relaxation rates | Validating local structure and dynamics from MD trajectories [35] [37] |

| SAXS Instrument | Experimental Instrument | Measures solution scattering profiles to determine Rg and molecular shape | Benchmarking global dimensions and compactness of simulated ensembles [39] [40] |

| ALBATROSS [34] | Computational Tool | Predicts IDR conformational properties directly from sequence | Rapid proteome-wide analysis of Rg and asphericity without simulations |

| MaxEnt Reweighting [39] | Computational Algorithm | Integrates MD simulations with experimental data | Determining force-field independent conformational ensembles |

| GOOSE [34] | Computational Tool | Designs synthetic IDR sequences with tailored chemistry | Systematically exploring sequence-ensemble relationships for force field training |

Selecting an appropriate force field requires considering the specific system and properties of interest. The following decision logic can guide researchers.

Figure 2: A practical decision tree for selecting a force field for hybrid protein systems containing both folded and disordered regions.

No single force field currently excels across all protein types and all experimental observables. CHARMM36m and a99SB-disp consistently rank highly for balanced performance across folded and disordered domains [39] [35] [14]. For simulations sensitive to conformational dynamics and subtle structural changes, such as folding-prone IDPs, DES-amber demonstrates superior performance [37]. When simulating large-scale assemblies or biomolecular condensates involving IDPs, the coarse-grained Martini3-IDP offers a computationally efficient alternative while maintaining reasonable accuracy [40].

Future force field development will likely focus on integrating more diverse experimental data, including from single-molecule techniques, and leveraging machine-learning approaches to better capture the complex energy landscapes of proteins that contain both structured and disordered elements [39] [34].

Water models are fundamental components in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, serving as the computational representation of solvent water that surrounds the biomolecules or materials being studied. The accuracy of these models directly influences the fidelity of simulations predicting the structural, dynamic, and thermodynamic properties of biological systems, ranging from intrinsically disordered proteins to nucleic acids and polysaccharides. Among the plethora of available models, TIP3P, TIP4P, TIP4P-D, and OPC represent some of the most widely used and actively developed explicit water models in contemporary research [41] [42]. The choice among them is not merely a technical detail but a critical determinant of simulation outcome, as each embodies different trade-offs between computational cost, physical accuracy, and transferability across diverse systems. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these four models, framing the discussion within the broader context of force field validation and offering practical protocols for researchers in drug development and related fields.

Model Specifications and Theoretical Foundations

The TIP3P, TIP4P, TIP4P-D, and OPC models belong to a class of rigid, non-polarizable models that use fixed point charges to represent water's electrostatic distribution. Their core differences lie in their geometric design and parameterization philosophy.

- TIP3P: A three-site model with charges located directly on the hydrogen and oxygen atoms. Its simplicity makes it computationally efficient, explaining its historical popularity in biomolecular simulations [42].

- TIP4P: A four-site model that relocates the negative charge from the oxygen atom to a dummy atom (the "M" site) located along the H-O-H bisector. This provides a more accurate representation of water's electrostatic potential, particularly its quadrupole moment [41].

- TIP4P-D: A reparameterization of the TIP4P model specifically designed to improve the description of dispersion interactions. It features modified Lennard-Jones parameters to correct for the overly attractive solute-solute interactions observed in earlier force fields, a crucial advancement for simulating disordered biomolecules [43].

- OPC (Optimal Point Charges): A modern four-site model parameterized using a force-matching procedure to reproduce a comprehensive set of liquid water properties, including the correct liquid density maximum at 4°C. It is renowned for its high accuracy across multiple thermodynamic properties [41] [42].

Table 1: Fundamental Specifications of the Water Models

| Model | Number of Sites | Charge Placement | Parameterization Goal | Computational Cost |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIP3P | 3 | Charges on atoms (O, H, H) | Simplicity and speed | Lowest |

| TIP4P | 4 | Negative charge on "M" site | Improved electrostatic distribution | Moderate |

| TIP4P-D | 4 | Negative charge on "M" site | Corrected dispersion interactions | Moderate |

| OPC | 4 | Negative charge on "M" site | Reproduce comprehensive liquid water properties | Moderate |

Performance Benchmarking Across Key Properties

The performance of a water model is not absolute but must be evaluated against specific experimental observables. The following quantitative comparisons highlight the strengths and weaknesses of each model across a range of critical properties.

Bulk Water Properties

Benchmarking against the fundamental physical properties of pure water provides a baseline assessment of a model's accuracy.

Table 2: Comparison of Bulk Water Properties at 298 K

| Property | Experimental Value | TIP3P | TIP4P | TIP4P-D | OPC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density (g/cm³) | ~0.997 | Underestimates | Slightly underestimates | Accurate | Highly accurate |

| Dielectric Constant | ~78 | Underestimates (~90-100) [41] | Varies by variant | Data needed | Closest to experiment [41] |

| Self-Diffusion Coefficient (10⁻⁹ m²/s) | ~2.3 | Overestimates [41] [42] | Overestimates | Data needed | Accurate [41] |

| Viscosity (cP) | ~0.89 | Underestimates | Underestimates | Data needed | Accurate |

Biomolecular Simulation Performance

The ultimate test for a water model in biomedical research is its performance in biologically relevant simulations.

Table 3: Performance in Biomolecular Systems

| System Type | TIP3P | TIP4P | TIP4P-D | OPC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) | Leads to overly compact ensembles [43] | TIP4P-Ew: overly compact; TIP4P-D & OPC: consistent with experiment [43] | Excellent agreement with NMR diffusion data [43] | Excellent agreement with NMR diffusion data [43] |

| Glycosaminoglycans (e.g., Heparin) | Widely used, benchmarked [42] | Comparable performance [42] | Data needed | Comparable performance [42] |

| RNA Duplexes | Common default | Sensitive to associated force field [44] | Data needed | Minor influence on A-RNA shape [44] |

Experimental Validation and Case Studies

Validating IDP Conformational Ensembles with NMR Diffusion