Molecular Dynamics Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

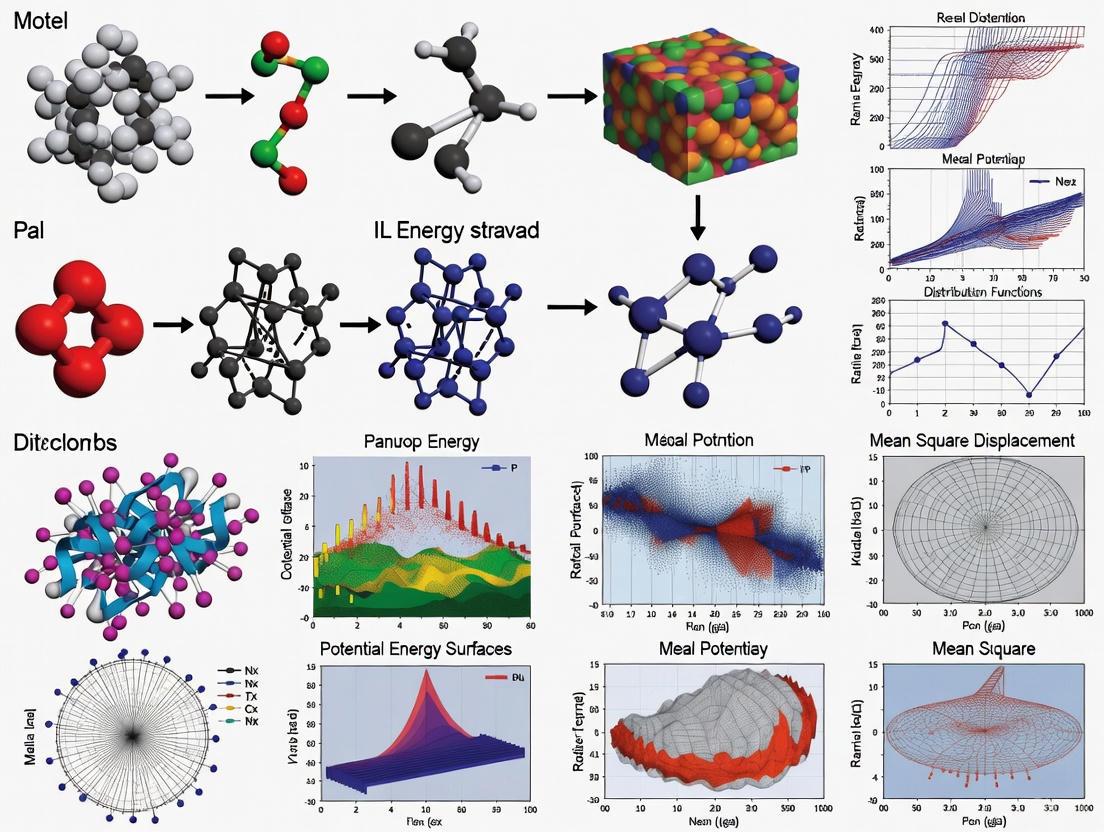

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a powerful computational tool that reveals atomic-level details of biomolecular processes critical for drug discovery.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a powerful computational tool that reveals atomic-level details of biomolecular processes critical for drug discovery. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers foundational principles from Newtonian mechanics and force fields to advanced applications in target identification, binding pose prediction, and lead optimization. The content further addresses methodological challenges, optimization strategies like enhanced sampling, and the integration of machine learning. Finally, it explores validation protocols and comparative analyses of MD with other computational techniques, synthesizing key insights to guide future research and clinical translation in biomedical sciences.

The Core Principles of Molecular Dynamics: From Atomic Forces to Biomolecular Motion

Molecular dynamics (MD) is a computational simulation technique that models the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. By applying Newton's laws of motion to a molecular system, MD provides an atomic-level view of dynamic processes, functioning as a computational microscope for researchers [1]. This capability to visualize and quantify molecular interactions that are difficult or impossible to observe experimentally has made MD an indispensable tool in modern scientific research, particularly in drug discovery and materials science [2].

Fundamental Principles and Key Components

At its core, classical molecular dynamics represents atoms as particles and bonds as springs, using an empirical potential energy function, or a force field, to calculate the forces acting on each atom [2]. The subsequent numerical integration of Newton's equations of motion generates a trajectory that describes how the positions and velocities of atoms evolve over time [1].

Core MD Algorithm and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental iterative workflow of a classical molecular dynamics simulation.

The basic MD algorithm involves several key components [1]:

- Force Field: An empirical potential energy function that defines the interactions between atoms, typically including:

- Bonded interactions (bonds, angles, dihedrals)

- Non-bonded interactions (electrostatic and Lennard-Jones forces)

- Integration Algorithms: Methods like velocity-Verlet or leap-frog that numerically solve Newton's equations of motion to update atomic positions and velocities.

- Ensemble: Conditions simulating real-world environments, such as the NPT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) or NVT ensemble (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) [3].

- Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC): A technique that emulates an infinite system by surrounding the central simulation box with replicas of itself [1].

- Thermostats and Barostats: Algorithms to maintain constant temperature and pressure, respectively, mimicking laboratory conditions.

MD Simulation in Drug Discovery: Key Applications

MD simulations provide critical insights across multiple stages of the drug development pipeline, from initial target validation to pharmaceutical formulation.

Table 1: Key Applications of MD Simulations in Drug Discovery and Development

| Application Area | Specific Use Cases | Research Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Target Validation & Characterization | Studying dynamics of drug targets (sirtuins, RAS proteins), intrinsically disordered proteins, antibody design [1]. | Provides insights into function and dynamics of identified drug targets. |

| Lead Discovery & Optimization | Evaluation of binding energetics and kinetics of ligand-receptor interactions [1]. | Guides selection of optimal candidate molecules for further development. |

| Membrane Protein Studies | Investigation of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), ion channels, and cytochrome P450 enzymes in realistic lipid bilayer environments [1]. | Enables study of pharmaceutically relevant proteins in native-like environments. |

| Solubility Prediction | Prediction of aqueous solubility using MD-derived properties (SASA, LJ energies, solvation free energy) [3]. | Machine learning models using MD properties achieve high predictive accuracy (R²=0.87) for solubility [3]. |

| Formulation Development | Studying crystalline/amorphous solids, stability of amorphous drug-polymer formulations, nanoparticle drug delivery systems [1]. | Informs development of stable and effective drug formulations. |

Experimental Protocol: Predicting Drug Solubility Using MD and Machine Learning

A recent study demonstrates a rigorous protocol for predicting aqueous solubility—a critical property in drug development—by combining MD simulations with machine learning [3].

1. System Preparation

- A dataset of 211 drugs from diverse classes was compiled from literature, with experimental solubility values (logS) ranging from -5.82 to 0.54 [3].

- Molecular dynamics simulations were conducted in the NPT ensemble using GROMACS 5.1.1 [3].

- The GROMOS 54a7 force field was employed to model molecules' neutral conformations [3].

- Each molecule was solvated in a cubic simulation box with explicit water molecules.

2. Production Simulation and Property Extraction

- Simulations were run sufficiently long to ensure proper sampling of molecular configurations.

- The following MD-derived properties were extracted from trajectories for each compound [3]:

- Solvent Accessible Surface Area (SASA)

- Coulombic interaction energy (Coulombic_t)

- Lennard-Jones interaction energy (LJ)

- Estimated Solvation Free Energy (DGSolv)

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD)

- Average number of solvents in Solvation Shell (AvgShell)

- The octanol-water partition coefficient (logP) was also incorporated as a feature due to its established relationship with solubility.

3. Machine Learning Model Training

- The seven extracted properties were used as input features for four ensemble machine learning algorithms [3]:

- Random Forest (RF)

- Extra Trees (EXT)

- eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB)

- Gradient Boosting Regression (GBR)

- The dataset was split into training and test sets for model validation.

- Model performance was evaluated using R² (coefficient of determination) and RMSE (root mean square error).

4. Results and Validation

- The Gradient Boosting algorithm achieved the best performance with a predictive R² of 0.87 and RMSE of 0.537 on the test set [3].

- This demonstrates that MD-derived properties have predictive power comparable to models based on structural fingerprints [3].

The integration of MD simulations with machine learning creates a powerful framework for predicting pharmaceutically relevant properties, enabling more efficient drug discovery while reducing resource consumption [3].

Advanced Methodologies and Recent Advances

Enhanced Sampling and Machine Learning Integration

As molecular systems of interest grow more complex, advanced sampling methods have been developed to overcome the limitations of conventional MD.

Table 2: Advanced Sampling Methods in Molecular Dynamics

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Application |

|---|---|---|

| Rare-Event Sampling | Umbrella Sampling, Metadynamics, Weighted Ensemble Path Sampling [2]. | Enhances sampling along predefined progress coordinates or collective variables. |

| Temperature-Based Methods | Parallel Tempering (Replica Exchange), Simulated Tempering, Integrated Tempering Sampling [2]. | Improves conformational sampling by simulating multiple temperatures. |

| Machine-Learning Enhanced MD | Autoencoders, Neural Networks for collective variables, Machine-learning force fields (e.g., ANI-2x) [2]. | Captures complex rare events and enables quantum-mechanical accuracy. |

| Molecular Augmented Dynamics (MAD) | Augmenting MD with experimental forces to match experimental observables [4]. | Generates structures consistent with experimental data like XRD, PDF, and XPS. |

High-Throughput Screening of Chemical Mixtures

Advanced workflows now combine high-throughput MD simulations with machine learning to screen complex chemical systems. One recent study generated a dataset of over 30,000 solvent mixtures using high-throughput classical MD simulations to evaluate machine learning approaches for predicting formulation properties [5]. The workflow involved:

- Formulation Selection: Identifying miscible solvent combinations using experimental miscibility tables [5].

- High-Throughput MD Simulations: Running standardized simulations for thousands of formulations using consistent protocols [5].

- Property Calculation: Extracting key properties including packing density, heat of vaporization (ΔHvap), and enthalpy of mixing (ΔHm) [5].

- Machine Learning Model Development: Comparing formulation descriptor aggregation (FDA), formulation graph (FG), and Set2Set-based (FDS2S) approaches [5].

This approach demonstrated robust transferability to experimental datasets, accurately predicting properties across energy, pharmaceutical, and petroleum applications [5].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Molecular Dynamics

| Resource Type | Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Software Packages | GROMACS [3], AMBER [1], NAMD [1], CHARMM [1], TurboGAP [4]. | MD simulation engines with various force fields and analysis capabilities. |

| Force Fields | GROMOS [3], OPLS4 [5], Gaussian Approximation Potential (GAP) [4]. | Define interaction potentials between atoms; parameterized for different molecule types. |

| Specialized Hardware | GPUs [2], Anton Supercomputers [2], Application-Specific Integrated Circuits (ASICs) [2]. | Accelerate MD calculations; enable longer timescale simulations. |

| Machine Learning Tools | DeepWatsite [6], ANI-2x [2], AlphaFold [2], Formulation-Property Models [5]. | Enhance binding-mode prediction, force field accuracy, and structure prediction. |

| Visualization & Analysis | SAMSON [7] [8], Color Palettes for Molecular Visualization [9] [7] [8]. | Visualize molecular structures, trajectories, and properties with effective color coding. |

Workflow for Machine Learning-Driven Drug Design

This diagram illustrates an integrated MD and machine learning pipeline for structure-based drug design.

This workflow demonstrates how MD simulations generate dynamic structural data that machine learning models use to predict ligand binding, creating an iterative cycle for drug candidate optimization [6].

The field of molecular dynamics continues to evolve rapidly, driven by advances in several key areas. Specialized hardware like application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) and field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) promise to dramatically accelerate simulations, potentially enabling routine access to biologically relevant timescales [2]. Machine learning force fields trained on quantum mechanical calculations are bridging the accuracy gap between classical and quantum simulations while maintaining computational efficiency [2]. The integration of MD with experimental data through methods like Molecular Augmented Dynamics (MAD) ensures that simulated structures remain consistent with experimental observables [4]. Finally, the combination of high-throughput MD simulations with machine learning is creating powerful predictive models for complex chemical systems and formulations [5].

Molecular dynamics has firmly established itself as a computational microscope, providing unprecedented insights into atomic-scale phenomena across drug discovery and materials science. As hardware capabilities grow and algorithms become more sophisticated, MD simulations will access longer timescales and larger systems, further blurring the boundaries between computation and experiment. The integration of MD with machine learning represents a particularly promising direction, creating synergistic methodologies that leverage the physical rigor of simulation with the predictive power of data-driven models. For researchers in drug development and beyond, molecular dynamics offers an increasingly indispensable toolkit for probing the molecular mechanisms that underlie biological function and therapeutic intervention.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation has emerged as an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals, providing atomic-resolution insights into biomolecular recognition, protein-ligand interactions, and cellular processes. This technical guide examines the core theoretical foundations of MD simulations, focusing on the integration of Newtonian mechanics with statistical ensemble theory. The dynamic behavior of biological systems, crucial for understanding drug binding and protein function, can be precisely modeled through this framework, enabling the interpretation of experimental data and prediction of molecular behavior. By bridging microscopic particle dynamics with macroscopic thermodynamic properties, MD simulations facilitate a fundamental understanding of biochemical processes that drive modern drug discovery efforts.

Theoretical Foundations of Molecular Dynamics

Newtonian Mechanics in Molecular Systems

Molecular dynamics simulations approximate the motion of particles in a system using classical Newtonian mechanics, treating each atom as a point mass evolving under forces generated by other particles in the system [10]. The time evolution of the system is governed by Newton's second law:

[ mi \frac{d^2\mathbf{r}i}{dt^2} = \mathbf{F}i = -\nablai U(\mathbf{r}1, \mathbf{r}2, ..., \mathbf{r}_N) ]

Where (mi) is the mass of particle (i), (\mathbf{r}i) its position, (\mathbf{F}_i) the force acting on it, and (U) the potential energy function describing interparticle interactions [10]. For a system of N particles, this constitutes a complex N-body problem that must be solved numerically using finite time steps Δt [10].

The potential energy function (U) is the critical component that distinguishes different materials and molecular systems. For simple systems such as noble gases, the Lennard-Jones potential serves as an appropriate model:

[ V_{\text{LJ}}(r) = 4\varepsilon \left[ \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{12} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{r}\right)^{6} \right] ]

Where ε is the depth of the potential well, σ is the finite distance at which the interparticle potential is zero, and r is the distance between particles [11]. The r⁻¹² term describes repulsive forces at short distances due to overlapping electron orbitals, while the r⁻⁶ term describes attractive forces at moderate distances (London dispersion forces) [11]. For Argon, typical parameters are σ = 3.4 Å and ε/kB = 120 K [10].

Statistical Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics

Statistical mechanics connects the microscopic states of a system to macroscopic thermodynamic quantities through probability functions [12]. Molecular dynamics simulations can be carried out under different thermodynamic ensembles, which represent systems with varying degrees of isolation from their environment [13].

Table 1: Thermodynamic Ensembles in Molecular Dynamics Simulations

| Ensemble | Constant Parameters | Physical Interpretation | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical (NVE) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Energy (E) | Isolated system that cannot exchange heat or matter with surroundings | Basic MD simulations; studying energy conservation |

| Canonical (NVT) | Number of particles (N), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | System in thermal contact with a heat bath at constant temperature | Equilibration stages; simulating constant temperature conditions |

| Isothermal-Isobaric (NPT) | Number of particles (N), Pressure (P), Temperature (T) | System that can exchange heat and adjust volume to maintain constant pressure | Mimicking laboratory conditions; production runs |

| Grand Canonical (μVT) | Chemical potential (μ), Volume (V), Temperature (T) | Open system that can exchange heat and particles with a reservoir | Studying adsorption, phase transitions |

The microcanonical ensemble (NVE) represents a completely isolated system where the number of particles (N), volume (V), and energy (E) remain constant [12] [13]. In this ensemble, the principle of equal probability states that all accessible microstates are equally likely, with probability p_i = 1/Ω, where Ω is the number of accessible microstates [12]. Boltzmann related this to entropy through the fundamental equation S = k log Ω, where k is Boltzmann's constant [12].

For most biological applications, the canonical (NVT) and isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensembles are more relevant as they better mimic experimental conditions [13]. The canonical ensemble describes a system with constant N, V, and T, which can be thought of as a special case of two interacting microcanonical systems where one system (the heat bath) is much larger than the other [12]. In MD simulations, temperature control is typically implemented by scaling particle velocities to adjust kinetic energy [13].

Table 2: Reduced Units in Lennard-Jones Systems

| Property | Symbol | Reduced Form |

|---|---|---|

| Length | r* | r/σ |

| Time | t* | t√(ε/mσ²) |

| Temperature | T* | kBT/ε |

| Energy | U* | U/ε |

| Pressure | p* | pσ³/ε |

| Density | ρ* | ρσ³ |

The use of reduced units, as shown in Table 2, is common in MD simulations as it provides numerical stability and simplifies equations [11]. This system requires specification of the size parameter σ and energy parameter ε, which define the characteristic length and energy scales of the system [11].

Practical Implementation Framework

Numerical Integration and Boundary Conditions

In molecular dynamics simulations, the equations of motion cannot be solved exactly and must be integrated numerically using finite time steps Δt [10]. The Euler method provides a simple approach for time evolution, where position and velocity at the next time step are calculated as:

[ \mathbf{r}i(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{r}i(t) + \mathbf{v}i(t)\Delta t ] [ \mathbf{v}i(t+\Delta t) = \mathbf{v}i(t) + \frac{\mathbf{F}i(t)}{m_i}\Delta t ]

where (\mathbf{v}_i) is the velocity of particle i [10]. More sophisticated algorithms like Verlet or Leapfrog are often used in practice for better energy conservation.

To simulate bulk systems using a manageable number of particles, MD employs periodic boundary conditions [10]. In this approach, the simulation box is replicated infinitely in all directions, creating periodic images of all particles. When a particle leaves the central box, it re-enters on the opposite side, maintaining a constant number of particles [10]. For force calculations, the minimum image convention is used, where each particle interacts only with the closest periodic image of every other particle [10].

The force on particle i is calculated from the gradient of the potential energy function. For the Lennard-Jones potential, the force calculation simplifies to:

[ \mathbf{F}i = \sum{j \neq i} 24\varepsilon \left[ 2\left(\frac{\sigma}{|\mathbf{r}{ij}|}\right)^{14} - \left(\frac{\sigma}{|\mathbf{r}{ij}|}\right)^{8} \right] \mathbf{r}_{ij} ]

where (\mathbf{r}{ij} = \mathbf{r}i - \mathbf{r}_j) [10]. The factor of 24 comes from the derivative of the Lennard-Jones potential, and the summation excludes j = i to avoid self-interaction.

Force Calculations and Potential Energy

The total potential energy in a molecular system is typically decomposed into several contributions:

[ U{\text{total}} = U{\text{bonded}} + U_{\text{nonbonded}} ]

where (U{\text{bonded}}) includes bond stretching, angle bending, and dihedral terms, while (U{\text{nonbonded}}) includes van der Waals and electrostatic interactions [11]. For non-bonded interactions, the Lennard-Jones potential serves as an archetype model for simple yet realistic intermolecular interactions [11]. The computational cost of non-bonded interactions grows as O(N²) with the number of particles N, though this is typically reduced using cutoff schemes and neighbor lists [11].

In practice, the "full" Lennard-Jones potential with its infinite range is often approximated using truncated versions to improve computational efficiency. The Lennard-Jones truncated and shifted (LJTS) potential is a common alternative:

[ V{\text{LJTS}}(r) = \begin{cases} V{\text{LJ}}(r) - V{\text{LJ}}(r{\text{end}}) & r \leq r{\text{end}} \ 0 & r > r{\text{end}} \end{cases} ]

where (r_{\text{end}}) is the cutoff distance, typically 2.5σ to 3.0σ [11]. While computationally cheaper, this modified potential yields different thermophysical properties and must be used with appropriate correction schemes for accurate simulation of bulk properties [11].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard MD Simulation Protocol

A typical molecular dynamics procedure involves multiple simulation stages performed in different ensembles, as illustrated in Figure 1. A standard protocol implemented in tools like GROMACS follows these stages [13]:

System Preparation: The initial protein structure is prepared by completing missing residues, resolving alternative residue locations, removing co-crystallized ligands and water molecules, and proper protonation at the desired pH value [14]. Special attention is paid to histidine protonation states (HIE, HID, or HIP) [14].

Solvation and Ion Addition: The prepared structure is solvated in a water box with periodic boundary conditions, with a water margin typically extending 10-20 Å from the protein surface [15]. The system is neutralized by adding counterions (e.g., Na⁺ or Cl⁻) [15].

Energy Minimization: The system undergoes energy minimization (typically 1000-5000 steps) to remove steric clashes and unfavorable contacts [15]. This step uses steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithms to find the nearest local energy minimum.

NVT Equilibration: The system is equilibrated in the NVT ensemble to stabilize the temperature, typically for 50-250 ps [13]. Temperature coupling is achieved using algorithms like Berendsen or Nosé-Hoover thermostats.

NPT Equilibration: Further equilibration in the NPT ensemble stabilizes pressure and density, typically for 50-250 ps [13]. Pressure coupling uses algorithms like Parrinello-Rahman or Berendsen barostats.

Production Run: The final simulation in the NPT ensemble collects data for analysis, with duration ranging from nanoseconds to microseconds depending on the system and research question [13].

For the EpCAM ectodomain dimer study cited in this guide, the production run was performed for 20 ns using a 2 fs time step at constant temperature (310 K) and pressure (1 atm) with periodic boundary conditions and full-system periodic electrostatics [15]. Coordinates were saved every 5 ps, resulting in a trajectory of 4000 frames for analysis [15].

Specialized Dynamics Methods

For certain applications, alternative dynamics methods may be employed. Brownian dynamics represents a simplified approach useful for studying diffusive processes [16]. In this method, inertial terms are neglected (overdamped limit), yielding the equation of motion:

[ \dot{X} = -\frac{D}{k_B T} \nabla U(X) + \sqrt{2D} R(t) ]

where D is the diffusion coefficient, U(X) is the potential energy, and R(t) is a Gaussian random force with ⟨R(t)⟩ = 0 and ⟨R(t)R(t′)⟩ = δ(t−t′) [16]. This approach is computationally efficient for studying large-scale biomolecular diffusion and association processes.

For systems requiring hydrodynamic interactions, the Ermak-McCammon algorithm extends Brownian dynamics to include these effects:

[ Xi(t+\Delta t) = Xi(t) + \sumj^N \frac{\Delta t D{ij}}{kB T} F[Xj(t)] + R_i(t) ]

where D_{ij} is the diffusion tensor accounting for hydrodynamic interactions between particles i and j [16].

Research Reagent Solutions and Computational Tools

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MD Simulations

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Software Suite | High-performance MD simulation package specializing in biomolecular systems [14] |

| NAMD | Software Suite | Parallel MD simulation package designed for large biomolecular systems [15] |

| AMBER99SB-ILDN | Force Field | Parameters for protein and nucleic acid simulations, including improved side-chain torsion angles [14] |

| CHARMM22 | Force Field | All-atom force field for proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [15] |

| TIP3P | Water Model | Three-site transferable intermolecular potential water model [14] |

| StreaMD | Automation Toolkit | Python-based tool for automating preparation, execution, and analysis of MD simulations [14] |

| VMD | Analysis/Visualization | Molecular visualization program for displaying, animating, and analyzing biomolecular systems [15] |

| UCSF Chimera | Analysis/Visualization | Interactive visualization and analysis of molecular structures and trajectories [15] |

Modern MD simulations rely on sophisticated software tools and well-parameterized force fields to accurately model biomolecular systems. As shown in Table 3, tools like GROMACS and NAMD provide the computational framework for running simulations, while force fields like AMBER99SB-ILDN and CHARMM22 supply the parameters defining interatomic interactions [15] [14]. These tools have enabled the simulation of systems comprising hundreds of thousands of atoms for hundreds of nanoseconds, with continuous improvements expanding these limits [12].

Automation tools like StreaMD have emerged to streamline the complex process of setting up, running, and analyzing MD simulations, making the technique more accessible to non-specialists [14]. This Python-based toolkit minimizes the required expertise for engaging in MD simulations and can efficiently operate across multiple servers within a network or cluster [14]. Such automation is particularly valuable in drug discovery applications where high-throughput screening of potential drug candidates requires consistent simulation protocols across hundreds or thousands of compounds.

The integration of Newtonian mechanics with statistical ensemble theory provides a powerful framework for understanding and implementing molecular dynamics simulations. This theoretical foundation enables researchers to connect atomic-level interactions with macroscopic thermodynamic properties, offering insights into biomolecular recognition, protein-ligand interactions, and cellular processes relevant to drug development. As computational resources continue to advance and methodologies refine, MD simulations will play an increasingly vital role in bridging theoretical predictions with experimental observations, ultimately accelerating the discovery and optimization of therapeutic compounds. The protocols and tools outlined in this guide provide both novice and experienced researchers with a comprehensive reference for designing and executing scientifically rigorous molecular dynamics investigations.

In molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a force field refers to the combination of a mathematical formula and associated parameters that describe the energy of a biological molecule as a function of its atomic coordinates [17]. Serving as the underlying engine of every MD simulation, force fields define the potential energy surface that governs atomic motions and interactions through a series of mathematical functions that approximate the complex quantum mechanical behavior of atoms and molecules [18]. The accuracy of any properly equilibrated molecular simulation is fundamentally determined by the ability of these parameters and equations to reproduce reality [19].

The general form of a classical force field energy function can be represented as:

E_total = E_bond + E_angle + E_torsion + E_non-bonded

Where the individual components correspond to bonded interactions (chemical bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded interactions (van der Waals forces, electrostatic interactions) [18]. The bonded terms maintain structural integrity through harmonic potentials for bond stretching and angle bending, along with periodic functions for torsional rotations, while the non-bonded terms describe intermolecular interactions and long-range forces using Lennard-Jones potentials for van der Waals interactions and Coulomb's law for electrostatic forces [18].

Despite this common foundation, major force field families have evolved with different philosophical approaches to parameterization—some emphasize reproduction of quantum mechanical calculations, others prioritize experimental condensed-phase properties, and some seek a balance between these approaches [20]. This review provides an in-depth technical examination of three predominant force fields—AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS—examining their theoretical foundations, parameterization strategies, comparative performance, and practical implementation in modern biomolecular research.

Methodologies for Force Field Evaluation and Comparison

Experimental Validation Protocols

Rigorous validation is essential for assessing force field performance. The methodology typically involves running MD simulations of benchmark systems and comparing the results against experimental data or high-level quantum mechanical calculations [21]. For protein force fields, common validation metrics include the ability to reproduce experimentally determined protein folding pathways, structural stability of known folds, and conformational ensembles of intrinsically disordered regions [22].

Specific experimental protocols include:

Folding and Stability Tests: Simulating small proteins and peptides with known native structures to assess whether the force field can maintain stable folded states or correctly fold from denatured states [17]. Key measurements include root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) from experimental structures, radius of gyration, and secondary structure content over multi-microsecond timescales.

Liquid Property Validation: For force fields parameterized for condensed-phase simulations, validation involves computing liquid densities, vapor-liquid coexistence curves, heats of vaporization, and solvation free energies for small organic molecules representing functional groups found in biomolecules [19].

Specialized System Testing: Evaluating performance on specific biomolecular systems such as membrane proteins, nucleic acid complexes, or non-natural peptides [21]. For example, in β-peptide simulations, researchers compare MD results with NMR-derived structures to assess structural accuracy [21].

Comparative Simulation Workflows

Impartial force field comparison requires standardized protocols to minimize algorithm-dependent effects:

Common Simulation Engine: Using a single MD engine like GROMACS that supports all force fields being compared, with rigorously validated, physically sound algorithms [21].

Identical Simulation Parameters: Applying the same integration time steps, temperature and pressure coupling schemes, cut-off distances, and long-range electrostatics treatments across all force field tests [21].

Multiple Test Systems: Evaluating performance across diverse molecular systems including proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and small molecules to identify force field strengths and limitations [17].

Statistical Robustness: Conducting multiple independent simulations with different initial conditions to account for stochastic variations and ensure reproducible results [21].

Comparative Analysis of Major Force Fields

Force Field Architectures and Parameterization Philosophies

The three major force field families—AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS—employ distinct parameterization strategies that reflect their different developmental histories and target applications.

AMBER (Assisted Model Building with Energy Refinement) force fields are developed primarily for simulations of proteins and nucleic acids with a focus on accurate description of structures and non-bonded energies [20]. The van der Waals parameters are typically obtained from crystal structures and lattice energies, while atomic partial charges are fitted to quantum mechanical electrostatic potential using the RESP (Restrained Electrostatic Potential) method without empirical adjustments [20]. This approach aims to achieve transferable parameters with strong theoretical foundations.

CHARMM (Chemistry at HARvard Macromolecular Mechanics) force fields employ a more comprehensive parameterization strategy that balances theoretical calculations with experimental validation [23]. The development philosophy emphasizes reproducing experimental data for small molecule crystals, liquid properties, and various spectroscopic measurements while maintaining compatibility with quantum mechanical calculations [18]. This empirical-theoretical hybrid approach aims to achieve balanced performance across diverse biological systems.

GROMOS (GROningen MOlecular Simulation) force fields follow a distinct philosophy focused on accurate reproduction of thermodynamic properties, particularly free energies of solvation and hydration [20]. Parameterized primarily against experimental data for heats of vaporization, liquid densities, and molecular solvation properties [20], GROMOS utilizes a united-atom approach where aliphatic hydrogens are combined with their parent carbon atoms to improve computational efficiency, though this requires careful parameterization to maintain accuracy in hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions [20].

Table 1: Force Field Parameterization Strategies and Target Applications

| Force Field | Parameterization Philosophy | Target Data for Parameterization | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER | Quantum mechanical electrostatic potential fitting with RESP method | Crystal structures, lattice energies, QM calculations | Proteins, nucleic acids, protein-ligand interactions |

| CHARMM | Balanced empirical-theoretical approach | Liquid properties, crystal data, spectroscopic measurements | Proteins, lipids, membrane systems, nucleic acids |

| GROMOS | Thermodynamic property optimization | Heats of vaporization, liquid densities, solvation free energies | Large-scale biomolecular simulations, lipid membranes |

Performance Comparison Across Biomolecular Systems

Recent comparative studies reveal distinctive performance profiles for each force field family across different biomolecular contexts.

In protein simulations, AMBER and CHARMM generally demonstrate strong performance in maintaining native protein structures and reproducing experimental folding behavior [18]. The AMBER force fields, particularly the AMBER99SB-ILDN variant, show excellent capability in simulating structured proteins, while CHARMM36m has demonstrated advantages for intrinsically disordered proteins and complex membrane systems [23] [22].

For non-natural peptides such as β-peptides, a 2023 comparative study found significantly different performance across force fields [21]. A recently developed CHARMM force field extension, based on torsional energy path matching against quantum-chemical calculations, performed best overall, accurately reproducing experimental structures in all monomeric simulations and correctly describing oligomeric examples [21]. The Amber force field could reproduce experimental secondary structures for β-peptides containing cyclic β-amino acids, while GROMOS had the lowest performance in this application [21].

In lipid and membrane systems, CHARMM36 has demonstrated particular strength, with the MacKerell lab regularly producing updated CHARMM force field files in GROMACS format optimized for lipid simulations [23]. Recommended parameters for CHARMM36 include using the Verlet cutoff scheme with force-switch modifier for van der Waals interactions, PME for electrostatics, and specific switching distance recommendations that vary depending on lipid composition [23].

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison Across Biomolecular Systems

| System Type | AMBER Performance | CHARMM Performance | GROMOS Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Proteins | Excellent structural maintenance with AMBER99SB-ILDN | Strong performance with CHARMM36m, especially for membrane proteins | United-atom efficiency but potential density deviations |

| Nucleic Acids | Excellent with parmbsc1 | Very good with CHARMM36 | Limited parameters available |

| Lipid Membranes | Requires additional parameterization | Excellent with CHARMM36 | Good for large-scale membrane simulations |

| Non-natural Peptides | Good for cyclic β-amino acids | Best overall for β-peptides [21] | Lowest performance for β-peptides [21] |

| Small Molecules | GAFF provides broad coverage | CGenFF for drug-like molecules | Limited small molecule parameters |

Technical Implementation and Parameter Recommendations

Successful implementation of each force field requires attention to specific technical requirements and parameter settings.

For CHARMM36 in GROMACS, the recommended settings include:

constraints = h-bondscutoff-scheme = Verletvdwtype = cutoffwithvdw-modifier = force-switchrlist = 1.2,rvdw = 1.2,rvdw-switch = 1.0coulombtype = PMEwithrcoulomb = 1.2DispCorr = no(except for lipid monolayers) [23]

The GROMOS force fields require special attention due to their original parameterization with a physically incorrect multiple-time-stepping scheme for a twin-range cut-off [23]. When used with modern single-range cut-off schemes, physical properties such as density might differ from intended values, requiring validation for specific molecular systems [23].

AMBER force fields in GROMACS benefit from the native support for multiple variants including AMBER94, AMBER96, AMBER99, AMBER99SB, AMBER99SB-ILDN, AMBER03, and AMBERGS [23]. For small molecules, the Generalized Amber Force Field (GAFF) provides parameters compatible with AMBER protein/nucleic acid force fields, accessible through tools like ANTECHAMBER and conversion scripts such as amb2gmx.pl or ACPYPE [23].

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Force Field Applications

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | High-performance MD simulation engine | Supports AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS force fields; exceptional parallelization [21] |

| AMBER Tools | Parameter derivation and system preparation | ANTECHAMBER for GAFF parameters; RESP charge fitting [23] |

| PyMOL | Molecular visualization and model building | Structure analysis and visualization of simulation results [21] |

| pdb2gmx | Topology generation in GROMACS | Creates molecular topologies for AMBER and CHARMM force fields [21] |

| make_top/OutGromacs | GROMOS topology generation | Creates topologies and interaction parameters for GROMOS force fields [21] |

| ACPYPE | AMBER to GROMACS topology conversion | Facilitates use of AMBER parameters in GROMACS simulations [23] |

Advanced Applications and Emerging Directions

Specialized Biomolecular Systems

Force field performance varies significantly when applied to specialized biomolecular systems beyond standard proteins. For nucleic acids, both AMBER (parmbsc1) and CHARMM36 have demonstrated strong performance, though with different strengths in handling specific conformational states [18]. Membrane proteins represent a particular challenge where CHARMM36 has shown advantages due to its extensive parameterization for lipid systems [23].

The emerging field of non-natural peptidomimetics presents unique challenges for classical force fields. β-peptides, the closest homologues of natural peptides, exhibit diverse structural motifs including helical structures, sheet-like conformations, hairpins, and higher-ordered oligomers [21]. These systems test the transferability and extensibility of force field parameters beyond natural biomolecules. Recent research has developed specific extensions for CHARMM and AMBER to improve their performance for these synthetic biological polymers [21].

Machine Learning and Future Force Field Development

The landscape of biomolecular force field development is being transformed by advances in machine learning (ML) [22]. Traditional force fields face inherent limitations in their functional forms and parameterization strategies, particularly in representing complex electronic effects and charge transfer phenomena [22]. ML approaches offer promising alternatives through:

Neural Network Potentials: Replacing traditional energy functions with neural networks trained on quantum mechanical data, potentially offering quantum-level accuracy at classical force field computational cost [22].

Automated Parameterization: Using stochastic optimizers and automatic differentiation techniques to streamline and improve parameter derivation processes [22].

Hybrid Physical-ML Models: Integrating machine learning components within traditional physical frameworks to maintain interpretability while improving accuracy [22].

These developments coincide with new demands in biological simulations, including modeling post-translational modifications, capturing polarization and charge transfer effects, and describing multivalent interactions in systems such as molecular glues and PROTACs [22]. The synergy between deep learning-based and physics-based approaches represents the most promising frontier for next-generation force fields that can address these complex biological questions [22].

Molecular dynamics force fields serve as the fundamental engine driving all biomolecular simulations, with AMBER, CHARMM, and GROMOS representing three mature but evolving families with distinct philosophies and strengths. AMBER excels in protein and nucleic acid simulations with its quantum mechanically-derived parameters; CHARMM provides balanced performance across diverse systems, particularly membranes and complexes; while GROMOS offers computational efficiency for large-scale simulations. The choice of force field remains system-dependent, requiring researchers to carefully match force field capabilities to their specific biological questions. As force fields continue to evolve—increasingly incorporating machine learning and addressing emerging challenges like post-translational modifications and chemical diversity—they will expand their indispensable role in bridging molecular structure with biological function in computational drug discovery and biomolecular engineering.

Force Field Selection Workflow

Force Field Development and Validation Pipeline

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have become an indispensable tool for studying the behavior of biomolecules at an atomic level, providing insights that are often difficult to obtain experimentally. The reliability of these simulations, however, hinges on the careful preparation of key input parameters. This guide details the core inputs—initial conformations, topology, and boundary conditions—framed within the broader thesis that robust MD research requires rigorous initial setup to ensure biological relevance and computational accuracy.

Initial Conformations: The Structural Foundation

The initial conformation is the starting three-dimensional atomic structure from which the simulation begins. Its quality is paramount, as it can influence the simulation's trajectory and convergence.

The primary source for initial structures is the Protein Data Bank. The structure must be carefully prepared, which includes adding missing hydrogen atoms and resolving any missing loops or residues, potentially through homology modeling [24] [25]. For studies of protein dynamics, it is critical to acknowledge that a single starting structure may be insufficient. As demonstrated in studies of calmodulin, running multiple independent simulations from equally plausible initial conditions provides a sample of the protein's dynamic properties and helps account for the inherent sampling problem in MD [26].

Molecular Topology: The Blueprint of Interactions

The topology file contains a complete description of the molecular system within the force field. It defines the identity of all atoms, their bonds, angles, dihedrals, non-bonded interactions (both Van der Waals and electrostatic), and atom-specific charges [25]. In essence, it translates the physical structure into a set of parameters that define the potential energy of the system.

Force Fields and Topology Generation

The choice of force field is embedded in the topology. Tools like pdb2gmx in GROMACS are used to process the initial coordinate file (e.g., protein.pdb) and generate the corresponding topology file (protein.top) based on a selected force field [25]. The topology must also account for non-standard molecules. If the protein structure includes a ligand, the ligand's chemistry must be explicitly defined, a separate topology constructed, and that information integrated into the main topology file [25].

Table 1: Key Components of a Molecular Topology File

| Component | Description | Role in Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Atoms | List of all atoms with their types, charges, and masses. | Defines the basic particles in the system. |

| Bonds | List of covalent bonds between atoms. | Constrains the distances between connected atoms. |

| Angles | List of angle definitions between every three connected atoms. | Governs the bending vibrations between atoms. |

| Dihedrals | List of torsional angles for every four connected atoms. | Defines the energy barriers for rotation around bonds. |

| Non-Bonded Parameters | Parameters for Van der Waals (Lennard-Jones) and electrostatic interactions. | Calculates forces between atoms that are not directly bonded. |

Boundary Conditions and System Setup

To simulate a biological system realistically without the artifacts of a vacuum interface, the molecule is placed within a defined volume and surrounded by solvent and ions. This is achieved using Periodic Boundary Conditions.

Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC)

PBC simulate a bulk environment by treating the primary simulation box as a unit cell that is replicated infinitely in all three spatial dimensions [27] [25]. As a molecule in the central box moves, its periodic images in the surrounding boxes move identically. When a particle exits the central box, one of its images simultaneously enters from the opposite side, conserving the number of atoms [27]. This approach allows for the simulation of a small, computationally tractable system while approximating the behavior of a much larger, bulk solution.

Minimum Image Convention and Cut-off Radius

A critical implementation of PBC is the minimum image convention, which ensures that each atom interacts with only the closest image of every other atom in the system, preventing spurious interactions with multiple copies of the same atom [27]. To make the calculation of non-bonding interactions computationally feasible, a cut-off radius is introduced. Interactions beyond this distance are typically not calculated directly [27]. The cut-off radius must be chosen carefully; for a cubic box, it should not exceed half the box size to comply with the minimum image convention [27]. This truncation has different implications for different forces: while the rapidly decaying Van der Waals interactions are less affected, the slow decay of electrostatic interactions requires advanced correction methods like Ewald summation to manage the error [27].

Diagram 1: MD System Setup Workflow

A Practical Protocol for System Setup

The following protocol, adapted for GROMACS, outlines the key steps to prepare a solvated and neutralized system from an initial protein structure [25].

Obtain and Prepare Protein Coordinates: Download a structure from the PDB. Visually inspect it and remove any crystallographic water molecules or co-factors not required for the simulation. Use

pdb2gmxto generate the initial GROMACS structure and topology files, selecting an appropriate force field during the process.pdb2gmx -f protein.pdb -p protein.top -o protein.gro[25]Define the Simulation Box: Use

editconfto place the protein in the center of a simulation box (e.g., cubic, dodecahedron) with a minimum distance (e.g., 1.4 nm) between the protein and the box edge.editconf -f protein.gro -o protein_editconf.gro -bt cubic -d 1.4 -c[25]Solvate the System: Fill the box with water molecules using the

solvatecommand. This step automatically updates the topology file to include the water molecules.gmx solvate -cp protein_editconf.gro -p protein.top -o protein_water.gro[25]Neutralize the System: Add counter-ions to neutralize the system's net charge. This requires first generating a pre-processed input file (

grompp) with a parameter file (em.mdp) and then usinggenion.grompp -f em.mdp -c protein_water -p protein.top -o protein_b4em.tprgenion -s protein_b4em.tpr -o protein_genion.gro -p protein.top -nn [Number of negative ions] -nq [Total positive charge](or-npfor positive ions) [25]

Diagram 2: Periodic Boundary Conditions Principle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Software and Inputs for MD Simulations

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Format |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | A robust, open-source MD simulation suite for all stages of simulation [25]. | Software Suite |

| Force Field | An empirical set of functions and parameters describing interatomic forces [25]. | ffG53A7 [25] |

| Parameter File (.mdp) | A file specifying all run parameters for the MD simulation (e.g., integration step, temperature, pressure coupling) [25]. | Text file |

| Molecular Topology (.top) | Defines the molecule(s) in the system, including atoms, bonds, and interaction parameters [25]. | Text file |

| Molecular Geometry (.gro) | Contains the coordinates and velocities of all atoms in the system. | GROMACS format |

| Rasmol / Grace | Molecular visualization and 2D plotting tools for inspection and analysis [25]. | Software |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Computer clusters are typically required for production runs to achieve microsecond-scale simulations in a reasonable time [25]. | Hardware |

The careful preparation of initial conformations, a accurate topology, and a realistic simulation environment with periodic boundary conditions forms the foundational triad of a meaningful molecular dynamics study. Attention to these inputs, supported by robust experimental protocols, is a prerequisite for generating reliable data that can advance our understanding of biological mechanisms and aid in drug development.

Within the broader context of molecular dynamics (MD) research, the analysis of trajectories represents the crucial bridge between raw simulation data and scientifically meaningful insights. Molecular dynamics is a computer simulation technique where the time evolution of a set of interacting atoms is followed by integrating their equations of motion, generating trajectories in a 6N-dimensional phase space (3N positions and 3N momenta) [28]. While the simulation itself captures the atomic-level movements, it is through meticulous trajectory analysis that researchers can translate these molecular pathways into understanding of biological processes, material properties, and chemical interactions relevant to drug development and materials science.

The fundamental challenge in MD analysis stems from the enormous volume and complexity of data produced. A single simulation may track thousands of atoms over millions of time steps, creating a rich but potentially overwhelming dataset [29] [28]. The extraction of meaningful information from these trajectories requires specialized analytical techniques and a clear understanding of both the computational methods and the underlying physical principles. This guide provides a comprehensive technical framework for implementing these analytical approaches, with particular emphasis on methodologies applicable to pharmaceutical research and drug development pipelines.

Fundamental Trajectory Properties and Equilibrium Analysis

Before employing advanced analytical techniques, researchers must establish that their simulation has reached equilibrium and stabilized sufficiently for production analysis. The initial transient phase (typically the first few hundred time steps) should be discarded as the system approaches equilibrium [29] [28]. Several fundamental properties serve as critical indicators of system stability and data quality.

Energy and Temperature Monitoring

The conservation of total energy in the NVE (microcanonical) ensemble provides a primary validation of simulation stability. In the NVT (canonical) ensemble, where temperature is kept constant, the kinetic energy should fluctuate around the expected value corresponding to the target temperature [29] [28]. The temperature can be calculated from the velocities using the equipartition theorem, where for a system with N atoms, the temperature T is proportional to the total kinetic energy [29]. Significant drift in these fundamental properties indicates simulation instability requiring investigation before proceeding with further analysis.

Equation of State Calculations

Once equilibrium is established, researchers can compute essential thermodynamic properties that characterize the system's state. These calculations form the foundation for more specialized analyses:

- Energy and Temperature: Given the system density, compute the energy and temperature using established formulae [29]

- Pressure Calculation: Determine pressure as the diagonal component of the momentum-flux tensor, providing crucial mechanical information about the system [29]

Table 1: Fundamental Equilibrium Properties for MD Trajectory Validation

| Property | Calculation Method | Interpretation | Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Energy | Sum of kinetic and potential energy at each time step | Conservation in NVE ensemble | Drift < 1% over production period |

| Temperature | Derived from kinetic energy via equipartition theorem | Stability in NVT ensemble | Fluctuations around target ±5% |

| Pressure | Diagonal components of stress tensor | Mechanical state of system | Consistent with experimental values where available |

| Density | Mass per unit volume | System packing | Stable to within 0.5% of expected value |

Structural Analysis Techniques

Understanding the spatial organization of atoms and molecules throughout a trajectory provides critical insights into material properties and biological function. Several quantitative methods have been established for this purpose.

Radial Distribution Function Analysis

The Radial Distribution Function (RDF), denoted as g(r), measures the probability of finding particle pairs at specific distances relative to an ideal gas [29]. This function reveals the short-scale structure of fluids and determines the virial coefficients of the Equation of State [29]. The RDF is computed by binning the N(N-1)/2 distances r_ij between all atom pairs throughout the trajectory [29].

For liquid systems, g(r) exhibits characteristic peaks corresponding to solvation shells, with the first peak indicating the nearest neighbor distance. In protein simulations, specific g(r) calculations can reveal ligand-binding distances, ion coordination shells, and hydration patterns. The coordination number, obtained by integrating g(r) up to the first minimum, provides quantitative information about local molecular environments.

Table 2: Structural Analysis Methods for MD Trajectories

| Method | Physical Information | Application Examples | Computational Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radial Distribution Function | Short-range order, solvation structure | Liquid structure, ion coordination | O(N²) per frame |

| Root Mean Square Deviation | Structural deviation from reference | Protein folding, conformational changes | O(N) per frame |

| Radius of Gyration | Molecular compactness | Protein folding, polymer collapse | O(N) per frame |

| Solvent Accessible Surface | Surface exposure | Binding sites, protein-protein interactions | O(N log N) per frame |

Root Mean Square Deviation and Fluctuation

Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) quantifies the conformational drift of a structure relative to a reference frame, typically the initial coordinates. It is calculated as:

[RMSD(t) = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^{N} |\vec{r}i(t) - \vec{r}_i^{ref}|^2}]

where (\vec{r}i(t)) is the position of atom i at time t, and (\vec{r}i^{ref}) is the reference position. For protein simulations, backbone atoms are typically used for this calculation to focus on structural changes rather than side-chain motions.

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) measures the flexibility of individual residues or atoms throughout the simulation, highlighting regions of structural rigidity and flexibility. This is particularly valuable for identifying flexible loops, hinge regions in enzymes, and binding sites that undergo conformational changes upon ligand binding.

Diagram 1: Structural Analysis Workflow

Advanced Analytical Methods

Time-Correlation Functions and Dynamics

Time-correlation functions provide powerful mathematical frameworks for extracting dynamic properties from MD trajectories. These functions quantify how a property correlates with itself or another property at different times, revealing the timescales of molecular processes.

The velocity autocorrelation function (VACF) is defined as:

[C_{vv}(t) = \langle \vec{v}(t) \cdot \vec{v}(0) \rangle]

where the angle brackets denote an average over all particles and time origins. The Fourier transform of the VACF relates to the vibrational density of states, while its integration provides diffusion coefficients through the Green-Kubo relation:

[D = \frac{1}{3} \int_0^\infty \langle \vec{v}(t) \cdot \vec{v}(0) \rangle dt]

Other important correlation functions include the dipole-dipole correlation function for spectroscopic properties, and hydrogen bond correlation functions for quantifying stability of molecular interactions. These analyses are particularly valuable for comparing simulation results with experimental measurements from techniques such as NMR, infrared spectroscopy, and neutron scattering.

Free Energy Calculations

Determining free energy landscapes from MD trajectories enables researchers to understand thermodynamic stability and spontaneous processes. Several advanced methods have been developed for this purpose:

- Umbrella Sampling: Uses harmonic biases along a reaction coordinate to enhance sampling of high-energy regions

- Metadynamics: Systematically fills free energy minima with repulsive potentials to encourage exploration

- Adaptive Biasing Force: Directly calculates the mean force along a reaction coordinate

These methods have proven particularly valuable in drug design for calculating binding affinities, predicting protein-ligand dissociation constants, and understanding conformational transitions that are difficult to observe in standard MD timescales.

Diagram 2: Free Energy Calculation Methods

Specialized Applications in Drug Development

ADMET Property Prediction

Molecular dynamics trajectories provide atomic-level insights into Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties critical to pharmaceutical development. The OmniMol framework represents a significant advancement in this area, formulating molecules and corresponding properties as a hypergraph to extract three key relationships: among properties, molecule-to-property, and among molecules [30]. This approach addresses the challenge of imperfectly annotated data common in pharmaceutical datasets where each property is associated with only a subset of molecules [30].

The OmniMol framework integrates a task-related meta-information encoder and a task-routed mixture of experts (t-MoE) backbone to capture correlations among properties and produce task-adaptive outputs [30]. This architecture demonstrates state-of-the-art performance in 47 out of 52 ADMET-P prediction tasks, showing particular strength in chirality-aware tasks—an essential consideration for drug specificity and safety [30].

Binding Affinity and Protein-Ligand Interactions

MD simulations enable quantitative assessment of protein-ligand interactions through various analytical approaches:

- MM/PBSA Calculations: Combine molecular mechanics energies with continuum solvation models to estimate binding free energies

- Interaction Fingerprints: Binary representations of specific interactions between protein residues and ligands

- Residence Time Calculations: From multiple simulations, estimate how long a ligand remains bound to its target

These analyses help optimize lead compounds during the Hit-to-Lead stage by providing insights into structure-activity relationships that guide medicinal chemistry efforts [30].

Table 3: MD Applications in Drug Development Pipeline

| Development Stage | MD Analysis Method | Information Gained | Impact on Decision Making |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lead Identification | Virtual screening with MD refinement | Binding mode prediction, stability assessment | Prioritization of synthesis candidates |

| Lead Optimization | MM/PBSA, interaction analysis | Specific atomic interactions, affinity estimates | Guidance for structural modifications |

| Preclinical Assessment | ADMET prediction frameworks | Toxicity, metabolic stability | Go/No-go decisions for animal studies |

| Formulation | Solubility, aggregation analysis | Physicochemical properties | Delivery system design |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful analysis of molecular dynamics trajectories requires specialized software tools and computational resources. The field has developed both comprehensive suites and specialized packages optimized for different aspects of trajectory analysis.

Table 4: Essential Software Tools for MD Trajectory Analysis

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Features | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD simulation and analysis | High performance, versatile analysis tools | Biomolecular systems, materials science |

| LAMMPS | Large-scale MD simulator | Extensibility, various force fields | Nanomaterials, coarse-grained systems |

| CHARMM | Biochemistry simulation | Comprehensive force field, experimental integration | Pharmaceutical research, biomolecules |

| AMBER | Biomolecular simulation | Specialized force fields, NMR refinement | Drug discovery, nucleic acids |

| VMD | Visualization and analysis | Extensive plugin ecosystem, scripting | Communication, publication figures |

| MDTraj | Lightweight analysis | Python API, fast trajectory processing | High-throughput analysis, method development |

Specialized computational architectures have also been developed to address the significant processing requirements of extensive MD analyses. These include special-purpose computers like ANTON for ultra-long timescales, and multi-GPU workstations for accessible high-performance computation [29]. Cloud-based distributed computing approaches provide scalability according to the model Ptotal = Pnode × Nnodes, where Ptotal is the total processing power, Pnode is per-node processing power and Nnodes is the number of nodes [31].

The extraction of meaningful information from molecular dynamics trajectories represents both a technical challenge and a scientific opportunity. As MD simulations continue to grow in temporal and spatial scale, sophisticated analysis methods become increasingly critical for connecting atomic-level observations with macroscopic properties and behaviors. The framework presented in this guide provides a systematic approach to trajectory analysis, from fundamental validation through advanced thermodynamic and kinetic characterization.

For researchers in drug development and materials science, effective trajectory analysis enables deeper understanding of molecular mechanisms, more accurate property prediction, and ultimately, better-informed decisions in the design and optimization of molecular entities. As machine learning approaches continue to integrate with traditional analysis methods, the field moves toward increasingly automated and insightful extraction of knowledge from the complex molecular pathways that underlie biological function and material behavior.

Classical Molecular Dynamics (MD) is a computational technique that predicts the time-dependent behavior of a molecular system by applying the principles of classical mechanics. It operates by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for every atom in the system, calculating the forces acting on each atom based on a defined mathematical model of interatomic interactions known as a force field [32] [33]. The resulting trajectory describes the spatial position of each atom at each point in time, effectively creating a three-dimensional "movie" of the atomic-level configuration with femtosecond resolution [32].

Despite the inherent approximations of classical mechanics, MD has emerged as a powerful tool in biomedical research, materials science, and chemistry. Its impact is particularly pronounced in molecular biology and drug discovery, where it helps decipher functional mechanisms of proteins, uncover structural bases for disease, and assist in the design of small molecules, peptides, and proteins [32] [34]. The value of MD simulations lies in their ability to capture the position and motion of every atom at a temporal resolution that is very difficult to achieve with experimental techniques, all while allowing for precise control over simulation conditions such as temperature, pressure, and molecular composition [32].

Table 1: Core Components of a Classical MD Simulation

| Component | Description | Common Examples/ Algorithms |

|---|---|---|

| Equation of Motion | Newton's second law (F=ma) is solved for each atom [33]. | Verlet, Leapfrog, Velocity Verlet [33] |

| Force Field | A mathematical model describing the potential energy of the system [35] [33]. | Bonded terms (bonds, angles), Non-bonded terms (van der Waals, electrostatic) [33] |

| Thermostat | An algorithm to control the temperature of the system [33]. | Berendsen, Nose-Hoover [33] |

| Barostat | An algorithm to control the pressure of the system [33]. | Berendsen, Parrinello-Rahman [33] |

| Boundary Conditions | Used to simulate an infinite system and avoid edge effects [33]. | Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC) [33] |

The Scope: Key Success Areas for Classical MD

Classical MD simulations provide exceptional insight into a wide range of biomolecular processes and material behaviors. Their success is rooted in the capacity to deliver high-resolution, dynamic data that is often inaccessible by experimental means.

Biomolecular Conformational Changes and Function

MD simulations excel at capturing the structural flexibility of proteins and other biomolecules, which is critical for understanding their function. Simulations can reveal functionally important conformational changes, such as the opening and closing of ion channels, the allosteric regulation of enzymes, and the large-scale motions of motor proteins [32]. By comparing simulations under different conditions, researchers can identify the atomic-level effects of perturbations like mutations, ligand binding, or post-translational modifications [32].

Molecular Interactions and Binding

A principal application of MD is the characterization of intermolecular interactions, particularly in structure-based drug design. Simulations can model how a small molecule or therapeutic candidate binds to its protein target, providing detailed information on binding modes, affinity, and the stability of the complex [34] [33]. This goes beyond rigid "lock-and-key" docking by capturing the induced-fit effects where both the ligand and the protein's binding site adapt to form a stable complex [33].

Studies of Membrane Proteins and Lipid Systems

MD is exceptionally well-suited for investigating membrane-embedded systems, such as G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and ion channels—targets of immense importance in neuroscience and pharmacology [32]. Simulations can model these proteins within realistic lipid bilayers to study their dynamics, lipid-protein interactions, and mechanisms of action [36]. Furthermore, MD is instrumental in studying self-assembling systems like lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), used for delivering genetic medicines, providing molecular insights into their structure, stability, and interactions with encapsulated RNA [36].

Guiding and Interpreting Experimental Data

MD simulations are increasingly used in synergy with experimental structural biology techniques. They can help interpret and validate data from cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), X-ray crystallography, NMR, and ion mobility-mass spectrometry [32] [37]. For instance, MD can be used to refine structural models, test the feasibility of proposed conformational pathways, or provide a dynamic context for a static experimental snapshot [32].

Fundamental Limitations and Challenges

Despite its broad applicability, classical MD faces several intrinsic limitations that constrain its predictive power and determine the types of questions it can reliably answer.

Timescale and Sampling Limitations

The most significant challenge in MD is the disparity between computationally accessible timescales and those of many biologically relevant events. Due to the need for femtosecond time steps to ensure numerical stability, a typical simulation involves millions or billions of steps [32]. While specialized hardware can push simulations to the millisecond scale, many critical processes—such as protein folding, large-scale conformational changes in proteins, and some drug unbinding events—can occur on timescales of milliseconds to seconds or longer, making them prohibitively expensive for straightforward "brute-force" simulation [32] [36]. This can lead to incomplete sampling, where the simulation fails to explore all relevant conformational states of the system.

Force Field Approximations and Accuracy

The forces in a classical MD simulation are calculated using a molecular mechanics force field, which is an approximate mathematical model fit to quantum mechanical calculations and experimental data [32]. While force fields have improved substantially, they remain imperfect [32]. Key limitations include:

- Fixed Bonding Topology: Classical force fields cannot model chemical reactions where covalent bonds form or break [32].

- Approximate Electrostatics: The treatment of electronic polarization is often limited, which can affect the accuracy of simulating interactions in heterogeneous environments like membrane interfaces [36].

- Parameterization Challenges: Accurately modeling non-standard molecules, such as novel drug-like compounds or ionizable lipids in LNPs, requires careful parameterization, and inaccuracies can propagate into the simulation results [36].

System Size Constraints

Although coarse-grained models allow the simulation of large complexes, all-atom MD of very large systems remains computationally demanding. This can limit the ability to study large molecular assemblies, such as ribosomes or entire viral capsids, with full atomic detail over biologically relevant timescales. Furthermore, simulating a system that is large enough to be biologically representative without introducing artifacts from finite size effects is a constant consideration [37].

Table 2: Summary of Key Limitations in Classical MD

| Limitation | Impact on Simulation | Potential Mitigations |

|---|---|---|

| Timescale Barrier | Inability to directly simulate slow biological processes (e.g., protein folding) [32]. | Enhanced sampling techniques, specialized hardware (e.g., GPUs, Anton) [32] [36]. |

| Force Field Inaccuracy | Potential for unrealistic dynamics or incorrect conformational preferences [32]. | Use of validated, modern force fields; QM/MM hybrid methods for reactions [32] [38]. |

| System Size Limit | Inability to model very large complexes at full atomic detail [37]. | Coarse-grained (CG) models; reduced system size with periodic boundaries [36] [33]. |

| Incomplete Sampling | Failure to observe a rare but critical event or to fully define the equilibrium state [36]. | Replica exchange MD, metadynamics, longer simulation times [36]. |

| Environmental Simplification | Simulations may not fully capture the complexity of the cellular environment [34]. | Constant pH MD (CpHMD), addition of crowders, complex membrane models [36]. |

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

The reliability of an MD study hinges on a rigorous methodological workflow, from system preparation to trajectory analysis.

Standard MD Protocol

A typical MD simulation follows a structured pipeline to ensure the stability and physical meaningfulness of the resulting trajectory.

Diagram 1: Classical MD workflow.

- Initial Structure Preparation: The simulation begins with an atomic-resolution structure, typically from the Protein Data Bank (PDB), or a computationally modeled structure. Hydrogen atoms are added, and protonation states of ionizable residues are assigned, sometimes requiring advanced techniques like constant-pH MD (CpHMD) for environment-dependent states [36].

- System Solvation and Neutralization: The biomolecule is placed in a box of explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P model). Ions are added to neutralize the system's net charge and to mimic a physiological ion concentration [33].

- Energy Minimization: The system undergoes energy minimization to remove any steric clashes or unphysical geometry introduced during setup. This step finds the nearest local energy minimum [35].

- Equilibration: The system is gradually heated to the target temperature (e.g., 310 K) and the density is adjusted to the target pressure (e.g., 1 bar) through short simulations with temperature and pressure couplers (thermostats and barostats). This ensures the system is stable and has the correct thermodynamic properties before data collection [33].

- Production Simulation: The equilibrated system is simulated for an extended period (nanoseconds to microseconds) with saved trajectory frames. This is the primary data-generating phase [35] [33].

- Trajectory Analysis: The saved trajectory is analyzed to extract biologically or physically relevant information, such as root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), radius of gyration, distances between residues, or interaction energies [32].

Enhanced Sampling Techniques

To overcome timescale limitations, advanced sampling methods are employed to accelerate the exploration of conformational space.

- Umbrella Sampling: Used to calculate the free energy profile along a pre-defined reaction coordinate by applying a biasing potential [36].

- Metadynamics: Enhances sampling by adding a history-dependent bias potential that discourages the system from revisiting already explored states [36].

- Replica Exchange MD (REMD): Runs multiple parallel simulations of the same system at different temperatures or with different Hamiltonians, allowing exchanges between them to escape local energy minima [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Successful MD research relies on a suite of software tools, force fields, and computational resources.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Classical MD

| Tool Category | Specific Tool / Reagent | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| MD Software Packages | GROMACS [35] [33] | Highly efficient, open-source package optimized for biomolecular simulation. |

| AMBER [34] [33] | Suite of programs with highly accurate force fields for proteins and nucleic acids. | |

| CHARMM [33] | Powerful software with extensive force fields for biological macromolecules. | |

| LAMMPS [33] | Flexible, open-source simulator for materials modeling and solid-state physics. | |

| Force Fields | CHARMM36 [33], AMBER ff14SB [33], GROMOS [33] | Parameter sets defining bonded and non-bonded interactions for proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. |

| Specialized Methods | ReaxFF [38] | A reactive force field capable of simulating bond formation and breaking. |

| CpHMD [36] | Constant-pH MD methods to model environment-dependent protonation states. | |

| Visualization & Analysis | VMD, PyMOL, MDAnalysis | Software for visualizing trajectories, analyzing structural properties, and preparing figures. |

Decision Framework: Classical vs. Alternative Methods

The choice between classical MD and a more advanced simulation technique depends on the specific scientific question. The following decision framework aids in selecting the appropriate method.

Diagram 2: Method selection guide.