Multi-Omics Data Integration: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

This article provides a systematic overview of multi-omics data integration, a transformative approach in biomedical research and drug discovery.

Multi-Omics Data Integration: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Best Practices

Abstract

This article provides a systematic overview of multi-omics data integration, a transformative approach in biomedical research and drug discovery. It explores the foundational principles of integrating diverse molecular data layers—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics—to achieve a holistic understanding of biological systems and complex diseases. We detail the landscape of computational methodologies, from statistical and network-based approaches to machine learning and AI-driven techniques, highlighting their specific applications in disease subtyping, biomarker discovery, and target identification. The content addresses critical challenges including data heterogeneity, method selection, and analytical pitfalls, while offering evidence-based guidance for optimizing integration strategies. Through comparative analysis of method performance and validation frameworks, this guide equips researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to design robust, biologically-relevant multi-omics studies that accelerate translation from basic research to clinical applications.

Understanding Multi-Omics Integration: From Basic Concepts to Biological Imperative

Multi-omics integration represents a transformative approach in biological research that moves beyond single-layer analysis by combining data from multiple molecular levels to construct a comprehensive view of cellular systems. This methodology integrates diverse omics layers—including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, epigenomics, and metabolomics—to reveal how interactions across these biological scales contribute to normal development, cellular responses, and disease pathogenesis [1]. The fundamental premise of multi-omics integration rests on the understanding that biological information flows through interconnected molecular layers, with each level providing unique yet complementary insights into system-wide functionality [2] [3].

Where single-omics analyses offer valuable but limited perspectives on specific molecular components, multi-omics integration enables researchers to connect genetic blueprints with functional outcomes, bridging the critical gap between genotype and phenotype [1] [4]. This holistic approach has demonstrated significant utility across various research domains, from revealing novel cell subtypes and regulatory interactions to identifying complex biomarkers that span multiple molecular layers [5] [2]. The integrated analysis of these complex datasets has become increasingly vital for advancing precision medicine initiatives, particularly in complex diseases like cancer, where molecular interactions operate through non-linear, interconnected pathways that cannot be fully understood through isolated analyses [6] [4].

Methodological Frameworks for Integration

The integration of multi-omics data can be conceptualized through multiple frameworks, each with distinct strategic advantages and computational considerations. One primary classification system recognizes three fundamental integration types based on temporal sequencing and methodological approach.

Integration Typologies by Data Structure

Multi-omics integration strategies are frequently categorized according to the structural relationship between the input datasets, which significantly influences methodological selection and analytical outcomes.

Table 1: Multi-Omics Integration Typologies Based on Data Structure

| Integration Type | Data Relationship | Key Characteristics | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matched (Vertical) Integration | Different omics measured from the same single cell or sample | Uses the cell itself as an anchor for integration; requires simultaneous measurement technologies | Single-cell multi-omics; CITE-seq; ATAC-RNA seq |

| Unmatched (Diagonal) Integration | Different omics from different cells of the same sample or tissue | Projects cells into co-embedded space to find commonality; more technically challenging | Integrating legacy datasets; large cohort studies |

| Mosaic Integration | Various omics combinations across multiple experiments with sufficient overlap | Creates single representation across datasets with shared and unique features | Multi-study consortia; integrating published datasets |

Matched integration, also termed vertical integration, leverages technologies that profile multiple distinct modalities from within a single cell, using the cell itself as an anchor point for integration [5]. This approach has been facilitated by emerging wet-lab technologies such as CITE-seq (which simultaneously measures transcriptomics and proteomics) and multiome assays (combining ATAC-seq with RNA-seq). In contrast, unmatched or diagonal integration addresses the more complex challenge of integrating omics data drawn from distinct cell populations, requiring computational methods to project cells into co-embedded spaces to establish biological commonality [5]. Mosaic integration represents an alternative strategy for experimental designs where different samples have various omics combinations that create sufficient overlap for integration, enabled by tools such as COBOLT and MultiVI [5].

Computational Integration Strategies by Timing

The computational approaches for multi-omics integration can be further classified based on the timing of integration within the analytical workflow, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

Table 2: Multi-Omics Integration Strategies by Timing

| Integration Strategy | Timing of Integration | Key Advantages | Common Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Before analysis | Captures all cross-omics interactions; preserves raw information | Data concatenation; matrix fusion |

| Intermediate Integration | During analytical processing | Reduces complexity; incorporates biological context | Similarity Network Fusion; MOFA+; MMD-MA |

| Late Integration | After individual analysis | Handles missing data well; computationally efficient | Ensemble methods; weighted averaging; model stacking |

Early integration, also called feature-level integration, involves merging all omics features into a single combined dataset before analysis [4]. While this approach preserves the complete raw information and can capture unforeseen interactions between modalities, it creates extremely high-dimensional data spaces that present computational challenges and increase the risk of identifying spurious correlations. Intermediate integration methods first transform each omics dataset into a more manageable representation before combination, often incorporating biological context through networks or dimensionality reduction techniques [5] [4]. Late integration, alternatively known as model-level integration, builds separate predictive models for each omics type and combines their predictions at the final stage, offering computational efficiency and robustness to missing data, though potentially missing subtle cross-omics interactions [4].

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Data Generation

Robust multi-omics integration begins with rigorous experimental protocols that ensure high-quality data generation across molecular layers. The following section outlines standardized procedures for generating multi-omics data from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), a frequently used sample type in immunological and translational research.

Protocol for High-Quality Single-Cell Multi-Omics from PBMCs

This protocol provides a standardized methodology for obtaining high-viability PBMCs and generating multi-omics libraries suitable for sequencing and analysis [7].

Sample Collection and PBMC Isolation

Blood Collection: Collect human whole blood using EDTA or heparin collection tubes to prevent coagulation. Process samples within 2 hours of collection to maintain cell viability.

PBMC Isolation:

- Dilute blood 1:1 with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) in a 50mL conical tube.

- Carefully layer the diluted blood over Ficoll-Paque PLUS density gradient medium at a 2:1 blood-to-Ficoll ratio.

- Centrifuge at 400 × g for 30 minutes at room temperature with the brake disengaged.

- After centrifugation, carefully aspirate the upper plasma layer and transfer the mononuclear cell layer at the interface to a new 50mL tube.

- Wash cells with 30mL of PBS and centrifuge at 300 × g for 10 minutes.

- Resuspend cell pellet in 10mL of PBS and count cells using a hemocytometer or automated cell counter.

- Assess viability using Trypan Blue exclusion, targeting >95% viability for optimal single-cell sequencing results.

Single-Cell Multi-Omics Library Construction

Single-Cell Suspension Preparation:

- Adjust cell concentration to 700-1,200 cells/μL in PBS with 0.04% bovine serum albumin (BSA).

- Filter cell suspension through a 40μm flow cytometry mesh to remove aggregates and debris.

- Keep cells on ice until loading onto the single-cell partitioning system.

Multi-Omics Library Preparation:

- Partition single cells into nanoliter-scale droplets using the 10x Genomics Chromium Controller or similar system.

- Perform cell lysis within partitions followed by reverse transcription with barcoded oligo-dT primers for transcriptome capture.

- For simultaneous assay of transposase-accessible chromatin (ATAC), add transposase enzyme to simultaneously fragment accessible chromatin and add adapter sequences.

- For protein expression measurement, incubate cells with antibody-derived tags (ADTs) prior to partitioning.

- Recover barcoded cDNA, chromatin fragments, and protein tags through emulsion breaking and purification.

- Amplify cDNA and construct sequencing libraries following manufacturer protocols for multiome assays.

- Assess library quality using Agilent Bioanalyzer or TapeStation, and quantify using qPCR-based methods.

Sequencing and Multi-Omics Data Generation

Sequencing Configuration:

- Pool libraries appropriately based on calculated molarity to ensure balanced representation.

- Sequence on Illumina NovaSeq X Series or similar platform using appropriate read lengths (e.g., 28bp Read 1, 10bp i7 index, 10bp i5 index, 90bp Read 2 for gene expression).

- Target sequencing depth of 20,000-50,000 read pairs per cell for gene expression, 25,000 fragments per cell for ATAC-seq, and 5,000 read pairs per cell for protein expression.

Quality Control Metrics:

- Cell viability >85% post-isolation

- RNA integrity number (RIN) >8.0 if extracting RNA separately

- >1,000 genes detected per cell for transcriptomics

- >1,000 fragments in peak regions per cell for ATAC-seq

- Minimal doublet rate (<5%) as determined by doublet detection algorithms

Multi-Omics Data Visualization and Analysis

The complexity of multi-omics datasets necessitates specialized visualization tools that can simultaneously represent multiple data modalities while maintaining spatial and molecular context. Integrative visualization platforms have emerged as essential components of the multi-omics analytical workflow, enabling researchers to explore complex relationships across molecular layers.

Advanced Visualization Frameworks

Vitessce represents a state-of-the-art framework for interactive visualization of multimodal and spatially resolved single-cell data [8]. This web-based tool enables simultaneous exploration of transcriptomics, proteomics, genome-mapped, and imaging modalities through coordinated multiple views. The platform supports visualization of millions of data points, including cell-type annotations, gene expression quantities, spatially resolved transcripts, and cell segmentations across multiple linked visualizations. Vitessce's capacity to handle AnnData, MuData, SpatialData, and OME-Zarr file formats makes it particularly valuable for analyzing outputs from popular single-cell analysis packages like Scanpy and Seurat [8].

The framework addresses five key challenges in multi-omics visualization: (1) tailoring visualizations to problem-specific data and biological questions, (2) integrating and exploring multimodal data with coordinated views, (3) enabling visualization across different computational environments, (4) facilitating deployment and sharing of interactive visualizations, and (5) supporting data from multiple file formats [8]. For CITE-seq data, for example, Vitessce enables validation of cell types characterized by markers in both RNA and protein modalities through linked scatterplots and heatmaps that simultaneously visualize protein abundance and gene expression levels [8].

Analytical Workflows for Multi-Omics Integration

The analytical process for multi-omics data typically follows a structured workflow that progresses from raw data processing through integrated analysis and biological interpretation.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful multi-omics integration requires both wet-lab reagents for high-quality data generation and computational tools for integrated analysis. The following tables catalog essential resources for multi-omics research.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Multi-Omics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll-Paque PLUS | Density gradient medium for PBMC isolation | Maintains cell viability; critical for obtaining high-quality single-cell data |

| Antibody-derived Tags (ADTs) | Oligonucleotide-conjugated antibodies for protein detection | Enable simultaneous measurement of proteins and transcripts in CITE-seq |

| Chromium Single Cell Multiome ATAC + Gene Expression | Commercial kit for simultaneous ATAC and RNA sequencing | Provides optimized reagents for coordinated nuclear profiling |

| Tn5 Transposase | Enzyme for tagmentation of accessible chromatin | Critical for ATAC-seq component of multiome assays |

| Barcoded Oligo-dT Primers | Capture mRNA with cell-specific barcodes | Enable single-cell resolution in droplet-based methods |

| Nuclei Isolation Kits | Extract intact nuclei for epigenomic assays | Maintain nuclear integrity for ATAC-seq and related methods |

Computational Tools for Multi-Omics Integration

Table 4: Computational Tools for Multi-Omics Integration

| Tool | Methodology | Data Types | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat v4/v5 | Weighted nearest-neighbor; Bridge integration | mRNA, spatial, protein, chromatin | Comprehensive single-cell analysis; spatial integration |

| MOFA+ | Factor analysis | mRNA, DNA methylation, chromatin accessibility | Identifies latent factors driving variation across omics |

| GLUE | Graph variational autoencoder | Chromatin accessibility, DNA methylation, mRNA | Uses prior knowledge to guide integration |

| Flexynesis | Deep learning toolkit | Bulk multi-omics data | Modular architecture; multiple supervision heads |

| Vitessce | Interactive visualization | Transcriptomics, proteomics, imaging, genome-mapped | Coordinated multiple views; web-based |

| StabMap | Mosaic data integration | mRNA, chromatin accessibility | Robust reference mapping for mosaic integration |

| TotalVI | Deep generative model | mRNA, protein | Probabilistic modeling of CITE-seq data |

| xCMS | Statistical correlation | Metabolomics with other omics | Identifies correlated features across modalities |

The computational landscape for multi-omics integration continues to evolve, with recent advancements focusing on deep generative models (such as variational autoencoders), graph neural networks, and transfer learning approaches [5] [9] [6]. These methods increasingly address key analytical challenges including high-dimensionality, heterogeneity, missing data, and batch effects that frequently complicate multi-omics studies [9] [3]. Benchmarking studies have demonstrated that no single method consistently outperforms others across all applications, highlighting the importance of tool selection based on specific research questions and data characteristics [6].

Multi-omics integration represents a paradigm shift in biological research, moving beyond single-layer analysis to provide a holistic understanding of molecular systems. By simultaneously considering multiple biological scales—from genetic variation to metabolic output—researchers can uncover emergent properties and interactions that remain invisible in isolated analyses. The continued development of experimental protocols, computational methods, and visualization frameworks will further enhance our ability to extract meaningful biological insights from these complex datasets, ultimately advancing applications in precision medicine, biomarker discovery, and fundamental biological understanding.

Systems biology represents a fundamental shift from a reductionist to a holistic approach for understanding biological systems, requiring the integration of multiple quantitative molecular measurements with well-designed mathematical models [10]. The core premise is that the behavior of a biological system cannot be fully understood by studying its individual components in isolation [11]. Instead, systems biology aims to understand how biological components function as a network of biochemical reactions, a process that inherently requires integrating diverse data types and computational modeling to predict system behavior [11] [10].

The essential nature of integration stems from several key biological drivers. First, biological systems exhibit emergent properties that arise from complex interactions between molecular layers—genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic [10]. Second, metabolites represent the downstream products of multiple interactions between genes, transcripts, and proteins, meaning metabolomics can provide a 'common denominator' for understanding the functional output of these integrated processes [10]. Finally, mathematical models are central to systems biology, and these models depend on multiple sources of data in diverse forms to define components, biochemical reactions, and corresponding parameters [11].

Key Biological Drivers for Integration

Multi-Omic Interactions and Emergent Properties

Biological systems function through intricate cross-talk between multiple molecular layers that cannot be properly assessed by analyzing each omics layer in isolation [10]. The integration of different omics platforms creates a more holistic molecular perspective of studied biological systems compared to traditional approaches [10]. For instance, different omics layers may produce complementary but occasionally conflicting signals, as demonstrated in studies of colorectal carcinomas where methylation profiles were linked to genetic lineages defined by copy number alterations, while transcriptional programs showed inconsistent connections to subclonal genetic identities [12].

Table 1: Key Drivers Necessitating Integrated Approaches in Systems Biology

| Biological Driver | Integration Challenge | Systems Biology Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-talk between molecular layers | Isolated analysis provides incomplete picture | Simultaneous analysis of multiple omics layers reveals interconnections |

| Non-linear relationships | Simple correlations miss complex interactions | Network modeling captures dynamic relationships between components |

| Temporal dynamics | Static snapshots insufficient for understanding pathways | Time-series data integration enables modeling of system fluxes |

| Causality identification | Statistical correlations do not imply mechanism | Integrated models help distinguish causal drivers from correlative events |

Proximity to Phenotype and Functional Validation

Metabolomics occupies a unique position in multi-omics integration due to its closeness to cellular or tissue phenotypes [10]. Metabolites represent the functional outputs of the system, providing a critical link between molecular mechanisms and observable characteristics [10]. This proximity to phenotype means that metabolomic data can serve as a validation layer for hypotheses generated from other omics data, ensuring that integrated models reflect biologically relevant states rather than statistical artifacts.

The quantitative nature of metabolomics and proteomics data makes it particularly valuable for parameterizing mathematical models of biological systems [11] [10]. Unlike purely qualitative data, quantitative measurements of metabolite concentrations and reaction kinetics allow researchers to build predictive rather than merely descriptive models [11]. This capability transforms systems biology from an observational discipline to an experimental one, where models can generate testable hypotheses about system behavior under perturbation.

Multi-Omics Integration Methods and Protocols

Workflow-Driven Model Assembly and Parameterization

The Taverna workflow system has been successfully implemented for the automated assembly of quantitative parameterised metabolic networks in the Systems Biology Markup Language (SBML) [11]. This approach provides a systematic framework for model construction that begins with building a qualitative network using data from MIRIAM-compliant sources, followed by parameterization with experimental data from specialized repositories [11].

Table 2: Key Database Resources for Multi-Omics Integration

| Resource Name | Data Type | Role in Integration | Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| SABIO-RK | Enzyme kinetics | Provides kinetic parameters for reaction rate laws | Web service interface [11] |

| Consensus metabolic networks | Metabolic reactions | Supplies reaction topology and stoichiometry | SQLITE database web service [11] |

| Uniprot | Protein information | Annotates enzyme components with standardized identifiers | MIRIAM-compliant annotations [11] |

| ChEBI | Metabolite information | Provides chemical structure and identity standardization | MIRIAM-compliant annotations [11] |

Protocol: Workflow-Driven Model Construction

Qualitative Model Construction

- Input: Pathway term or list of gene identifiers (e.g., yeast open reading frame numbers)

- Process: Automated retrieval of reaction information from consensus metabolic networks

- Output: Qualitative SBML model containing compartments, species, and reactions [11]

Model Parameterization

- Map proteomics and metabolomics measurements from key results databases onto starting concentrations of enzymes and metabolites

- Retrieve kinetic parameters from SABIO-RK using web service interface

- Insert appropriate rate laws for each reaction, defaulting to mass action kinetics when specific parameters unavailable [11]

Model Calibration and Simulation

- Calibrate parameters using parameter estimation feature in COPASI via COPASIWS web service

- Define parameters for estimation and experimental datasets for fitting

- Execute simulations to predict system behavior under defined conditions [11]

Experimental Design for Multi-Omics Studies

Proper experimental design is critical for successful multi-omics integration. Key considerations include generating data from the same set of samples when possible, careful selection of biological matrices compatible with all omics platforms, and appropriate sample collection, processing, and storage protocols [10]. Blood, plasma, or tissues are excellent bio-matrices for generating multi-omics data because they can be quickly processed and frozen to prevent rapid degradation of RNA and metabolites [10].

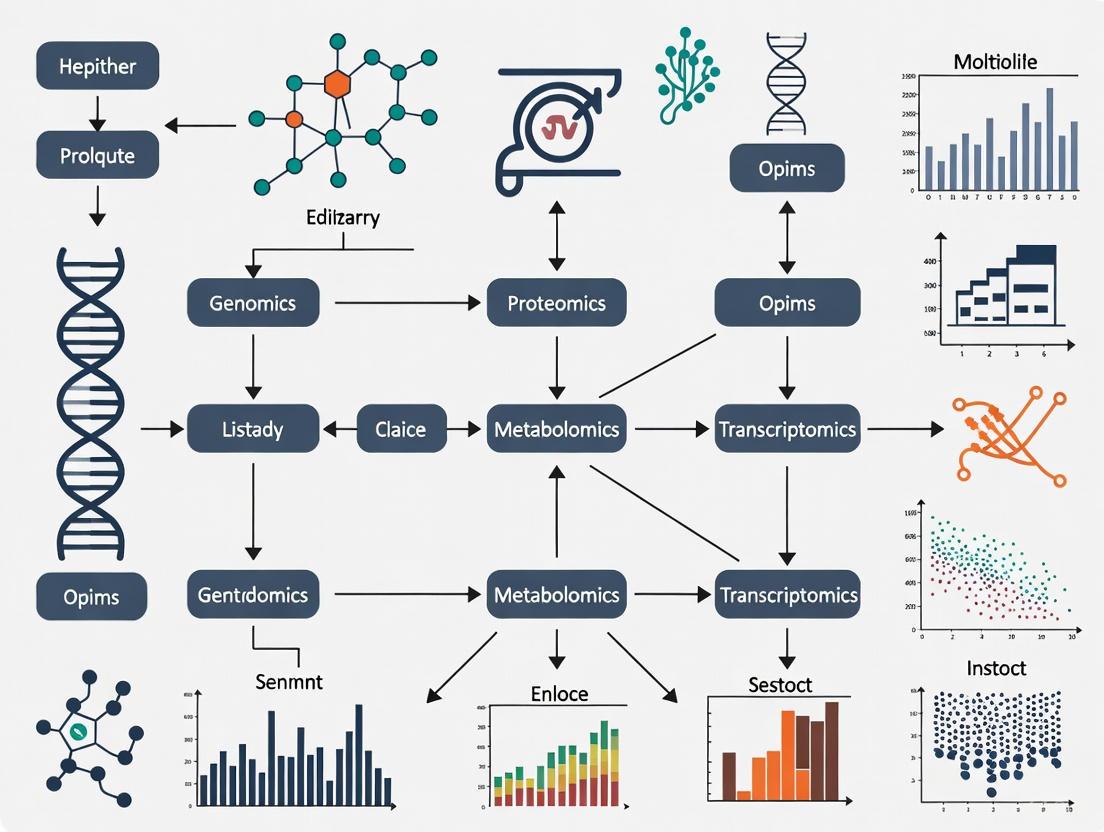

Diagram 1: Multi-Omics Experimental Workflow. This workflow outlines the systematic process for designing and executing integrated multi-omics studies.

Recent research has identified nine critical factors that fundamentally influence multi-omics integration outcomes, categorized into computational and biological aspects [12]. Computational factors include sample size, feature selection, preprocessing strategy, noise characterization, class balance, and number of classes [12]. Biological factors encompass cancer subtype combinations, multi-omics layer integration, and clinical feature correlation [12].

Protocol: Optimal Multi-Omics Study Design

Sample Size Determination

Feature Selection and Processing

Data Integration and Validation

- Choose integration method based on data types and research question

- Validate integrated models using clinical annotations and functional assays

- Perform sensitivity analysis to identify key drivers of system behavior

Computational Frameworks and AI-Driven Integration

Advanced Machine Learning Approaches

Deep generative models, particularly variational autoencoders (VAEs), have emerged as powerful tools for multi-omics integration, addressing challenges such as data imputation, augmentation, and batch effect correction [9]. These approaches can uncover complex biological patterns that improve our understanding of disease mechanisms [9]. Recent advancements incorporate regularization techniques including adversarial training, disentanglement, and contrastive learning to enhance model performance and biological interpretability [9].

The emergence of foundation models represents a promising direction for multimodal data integration, potentially enabling more robust and generalizable representations of biological systems [9]. These models can leverage transfer learning to address the common challenge of limited sample sizes in multi-omics studies, particularly for rare diseases or specific cellular contexts.

AI-Powered Multi-Scale Modeling

A new artificial intelligence-powered biology-inspired multi-scale modeling framework has been proposed to integrate multi-omics data across biological levels, organism hierarchies, and species [13]. This approach aims to predict genotype-environment-phenotype relationships under various conditions, addressing key challenges in predictive modeling including scarcity of labeled data, generalization across different domains, and disentangling causation from correlation [13].

Diagram 2: AI-Driven Multi-Omics Integration Framework. This diagram illustrates the computational architecture for artificial intelligence-powered integration of multi-omics data across scales.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Integration

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Integration |

|---|---|---|

| Database Resources | SABIO-RK, Uniprot, ChEBI, KEGG, Reactome | Provides standardized biochemical data for model parameterization [11] |

| Workflow Management Systems | Taverna Workbench | Manages flow of data between computational resources in automated model construction [11] |

| Model Simulation Tools | COPASI (via COPASIWS) | Analyzes biochemical networks through calibration and simulation [11] |

| Standardized Formats | SBML (Systems Biology Markup Language) | Represents biochemical reactions in biological models for exchange and comparison [11] |

| Annotation Standards | MIRIAM (Minimal Information Requested in Annotation of Models) | Standardizes model annotations using Uniform Resource Identifiers and controlled vocabularies [11] |

Integration is fundamentally essential to systems biology because biological systems themselves are integrated networks of molecular interactions that span multiple layers and scales. The key biological drivers—including multi-omic interactions, proximity to phenotype, and the need for predictive modeling—necessitate approaches that can synthesize diverse data types into coherent models of system behavior. Current methodologies, ranging from workflow-driven model assembly to AI-powered multi-scale integration, provide powerful frameworks for addressing these challenges. As these technologies continue to evolve, they promise to enhance our understanding of disease mechanisms, identify novel therapeutic targets, and ultimately advance the goals of precision medicine.

Multi-omics approaches integrate data from various molecular layers to provide a comprehensive understanding of biological systems and disease mechanisms. This integration allows researchers to move beyond the limitations of single-omics studies, uncovering complex interactions and causal relationships that would otherwise remain hidden. The five major omics layers—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics, and epigenomics—provide complementary read-outs that, when analyzed together, offer unprecedented insights into cellular biology, disease etiology, and potential therapeutic targets [14] [15]. The field has seen rapid growth, with multi-omics-related publications on PubMed rising from 7 to 2,195 over an 11-year period, representing a 69% compound annual growth rate [14].

Omics Layers: Technologies and Molecular Read-outs

Table 1: Multi-omics Approaches and Their Molecular Read-outs [14]

| Omics Approach | Molecule Studied | Key Information Obtained | Primary Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | Genes (DNA) | Genetic variants, gene presence/absence, genome structure | Sequencing, exome sequencing |

| Transcriptomics | RNA and/or cDNA | Gene expression levels, splice variants, RNA editing sites | RT-PCR, RT-qPCR, RNA-sequencing, gene arrays |

| Proteomics | Proteins | Abundance of peptides, post-translational modifications, protein interactions | Mass spectrometry, western blot, ELISA |

| Epigenomics | Modifications of DNA | Location, type, and degree of reversible DNA modifications | Modification-sensitive PCR/qPCR, bisulfite sequencing, ATAC-seq, ChIP-seq |

| Metabolomics | Metabolites | Abundance of small molecules (carbohydrates, amino acids, fatty acids) | Mass spectrometry, NMR spectroscopy, HPLC |

Detailed Characterization of Omics Layers

Genomics focuses on the complete set of DNA in an organism, including the 3.2 billion base pairs in the human genome. It identifies variations such as single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions/deletions (indels), copy number variations (CNVs), duplications, and inversions that may associate with disease susceptibility [15]. The field has evolved from first-generation Sanger sequencing to next-generation sequencing (NGS) methods, with the latest T2T-CHM13v2.0 genome assembly closing previous gaps in the human reference sequence [16].

Transcriptomics provides a snapshot of all RNA transcripts in a cell or organism, indicating genomic potential rather than direct phenotypic consequence. High levels of RNA transcript expression suggest that the corresponding gene is actively required for cellular functions. Modern transcriptomic applications have advanced to single-cell and spatial resolution, capturing tens of thousands of mRNA reads across hundreds of thousands of individual cells [15].

Proteomics, a term coined by Marc Wilkins in 1995, studies protein interactions, functions, structure, and composition. While proteomics alone can uncover significant functional insights, integration with other omics data provides a clearer picture of organismal or disease phenotypes [15]. Recent advancements include analysis of post-translational modifications (PTMs) such as phosphorylation through phosphoproteomics, which requires specialized handling of residue/peptide-level data [17].

Epigenomics studies heritable changes in gene expression that do not involve alterations to the underlying DNA sequence, essentially determining how accessible sections of DNA are for transcription. Key epigenetic modifications include DNA methylation status (measured via bisulfite sequencing), histone modifications (analyzed through ChIP-seq or CUT&Tag), open-chromatin profiling (via ATAC-seq), and the three-dimensional profile of DNA (determined using Hi-C methodology) [15].

Metabolomics analyzes the complete set of metabolites and low-molecular-weight molecules (sugars, fatty acids, amino acids) that constitute tissues and cell structures. This highly complex field must account for the short-lived nature of metabolites as dynamic outcomes of continuous cellular processes. Changes in metabolite levels can indicate specific diseases, such as elevated blood glucose suggesting diabetes or increased phenylalanine in newborns indicating phenylketonuria [15].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Multi-Omics Data Generation Workflow

Multi-Omics Experimental Workflow

Next-Generation Sequencing Protocol for Genomics and Transcriptomics

Library Preparation and Sequencing

- Nucleic Acid Extraction: Isolate high-quality DNA or RNA using appropriate extraction kits. For RNA studies, include DNase treatment to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- Quality Control: Assess nucleic acid quality using agarose gel electrophoresis, Nanodrop, and Bioanalyzer. RNA Integrity Number (RIN) should be >8 for transcriptomics studies.

- Library Preparation: Fragment DNA/RNA to appropriate size (200-500 bp). For RNA-seq, perform reverse transcription to cDNA using reverse transcriptases [14]. Use DNA polymerases, dNTPs, and oligonucleotide primers for amplification [14].

- Adapter Ligation: Ligate platform-specific adapters containing barcodes for multiplexing.

- Library Amplification: Perform PCR amplification using high-fidelity DNA polymerases.

- Library Quantification: Use qPCR or Bioanalyzer for accurate quantification.

- Sequencing: Load libraries onto sequencer (Illumina, PacBio, or Oxford Nanopore). For Illumina platforms, use sequencing-by-synthesis technology with 100-300 bp read lengths [16].

Data Analysis Pipeline

- Quality Control: Assess read quality using FastQC. Remove adapters and trim low-quality bases with Trimmomatic [16].

- Alignment: Map reads to reference genome using BWA (for genomics) or STAR (for transcriptomics) [16].

- Variant Calling: Identify genetic variants using GATK HaplotypeCaller or Bcftools mpileup (for genomics) [16].

- Expression Quantification: Generate count matrices (for transcriptomics) using featureCounts or HTSeq.

- Differential Expression: Identify significantly differentially expressed genes using tools like DESeq2 or limma.

Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics Protocol

Sample Preparation and Data Acquisition

- Protein Extraction: Lyse cells/tissues in appropriate buffer (e.g., RIPA buffer) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors.

- Protein Quantification: Determine protein concentration using BCA or Bradford assay.

- Protein Digestion: Reduce, alkylate, and digest proteins with trypsin (1:50 enzyme-to-protein ratio) overnight at 37°C.

- Peptide Desalting: Clean up peptides using C18 solid-phase extraction columns.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Separate peptides using nano-flow liquid chromatography with C18 column

- Analyze eluting peptides with tandem mass spectrometry (Data-Dependent Acquisition mode)

- Use collision-induced dissociation or higher-energy collisional dissociation for fragmentation

Data Processing and Analysis

- Database Search: Identify peptides by searching MS/MS spectra against protein database using search engines (MaxQuant, Proteome Discoverer).

- Quality Filtering: Apply false discovery rate (FDR) threshold of <1% at peptide and protein levels.

- Quantitative Analysis: Perform label-free or isobaric labeling-based quantification.

- Normalization: Apply appropriate normalization methods (MaxMedian, MaxSum, or Reference normalization) [17].

- Missing Value Imputation: Use algorithms like svdImpute or skip imputation based on data characteristics [17].

- Batch Effect Correction: Apply ComBat, RUV, SVA, or NPM methods if required [17].

Multi-Omics Data Integration Methods

Computational Integration Approaches

- Early Integration: Combine raw datasets before analysis, requiring extensive normalization.

- Intermediate Integration: Transform individual omics datasets into joint representations using methods like MOFA+.

- Late Integration: Analyze datasets separately and integrate results, often using pathway enrichment or network-based approaches.

Table 2: Multi-Omics Data Integration Methods by Research Objective [18]

| Research Objective | Recommended Integration Methods | Example Tools | Common Omics Combinations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subtype Identification | Clustering, Matrix Factorization, Deep Learning | iCluster, MOFA+, SNF | Genomics + Transcriptomics + Proteomics |

| Detection of Disease-Associated Molecular Patterns | Statistical Association, Network-Based Approaches | PWEA, MELD | Genomics + Transcriptomics + Metabolomics |

| Understanding Regulatory Processes | Bayesian Networks, Causal Inference | PARADIGM, CERNO | Epigenomics + Transcriptomics + Proteomics |

| Diagnosis/Prognosis | Classification Models, Feature Selection | Random Forests, SVM | Genomics + Transcriptomics |

| Drug Response Prediction | Regression Models, Multi-Task Learning | MOLI, tCNNS | Transcriptomics + Proteomics + Metabolomics |

The Central Dogma and Multi-Omics Interrelationships

Multi-Omics Relationships in Central Dogma

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Multi-Omics Studies [14]

| Reagent/Material | Application Area | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Polymerases | Genomics, Epigenomics, Transcriptomics | Amplification of DNA fragments for sequencing and analysis | High-fidelity enzymes for PCR, PCR kits and master mixes |

| Reverse Transcriptases | Transcriptomics | Conversion of RNA to cDNA for downstream analysis | RT-PCR kits, cDNA synthesis kits and master mixes |

| Oligonucleotide Primers | All nucleic acid-based omics | Target-specific amplification and sequencing | Custom-designed primers for specific genes or regions |

| dNTPs | Genomics, Epigenomics, Transcriptomics | Building blocks for DNA synthesis and amplification | Purified dNTP mixtures for PCR and sequencing |

| Methylation-Sensitive Enzymes | Epigenomics | Detection and analysis of DNA methylation patterns | Restriction enzymes, FastDigest enzymes, methyltransferases |

| Restriction Enzymes | Genomics, Epigenomics | DNA fragmentation and methylation analysis | Conventional restriction enzymes with appropriate buffers |

| Proteinase K | Genomics, Transcriptomics | Digestion of proteins during nucleic acid extraction | Molecular biology grade for clean nucleic acid isolation |

| RNase Inhibitors | Transcriptomics, Epigenomics | Protection of RNA from degradation during processing | Recombinant RNase inhibitors for maintaining RNA integrity |

| Magnetic Beads | All omics areas | Nucleic acid and protein purification | Size-selective purification for libraries and extractions |

| Mass Spectrometry Grade Solvents | Proteomics, Metabolomics | Sample preparation and LC-MS/MS analysis | High-purity solvents (acetonitrile, methanol, water) |

| Trypsin | Proteomics | Protein digestion for mass spectrometry analysis | Sequencing grade, modified trypsin for efficient digestion |

Applications in Translational Medicine and Disease Research

Multi-omics approaches have demonstrated significant value across various areas of biomedical research:

Oncology: Integration of proteomic, genomic, and transcriptomic data has uncovered genes that are significant contributors to colon and rectal cancer, and revealed potential therapeutic targets [14]. Multi-omics subtyping of serous ovarian cancer, non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer, and triple-negative breast cancer has identified prognostic molecular subtypes and therapeutic vulnerabilities [9].

Neurodegenerative Diseases: Combining transcriptomic, epigenomic, and genomic data has helped researchers propose distinct differences between genetic predisposition and environmental contributions to Alzheimer's disease [14]. Large-scale resources like Answer ALS provide whole-genome sequencing, RNA transcriptomics, ATAC-sequencing, proteomics, and deep clinical data for comprehensive analysis [18].

Drug Discovery: Multi-omics approaches have proven crucial for identifying and verifying drug targets and defining mechanisms of action [14]. Integration methods help predict drug response by combining multiple molecular layers [18].

Infectious Diseases: During the COVID-19 pandemic, integration of transcriptomics, proteomics, and antigen receptor analyses provided insights into immune responses and potential therapeutic targets [14].

Basic Cellular Biology: Multi-omics has led to fundamental discoveries in cellular biology, including the identification of novel cell types through techniques like REAP-seq that simultaneously measure RNA and protein expression at single-cell resolution [14].

Several publicly available resources support multi-omics research:

- The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA): Provides comprehensive genomics, epigenomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics data for various cancer types [18].

- Answer ALS: Repository containing whole-genome sequencing, RNA transcriptomics, ATAC-sequencing, proteomics, and deep clinical data [18].

- jMorp: Database with genomics, methylomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics data [18].

- Omics Playground: Analysis platform supporting RNA-Seq, proteomics, and upcoming metabolomics and single-cell RNA-seq data with user-friendly tools for data normalization, batch correction, and visualization [17].

- DevOmics: Database with normalized gene expression, DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin accessibility and 3D chromatin architecture profiles of human and mouse early embryos [18].

These resources enable researchers to access pre-processed multi-omics datasets and utilize specialized analysis tools without requiring extensive computational infrastructure, thereby accelerating discoveries across various biological and medical research domains.

The integration of multi-omics data is fundamental to advancing precision oncology, enabling a comprehensive understanding of the complex molecular mechanisms driving cancer. Large-scale consortium-led data repositories provide systematically generated genomic, transcriptomic, epigenomic, and proteomic datasets that serve as critical resources for the research community. Within the context of multi-omics data integration techniques, this application note details four pivotal resources: The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC), International Cancer Genome Consortium (ICGC), and the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE). These repositories provide complementary data types that, when integrated, facilitate the discovery of novel biomarkers, therapeutic targets, and molecular classification systems across cancer types [12] [19]. The strategic utilization of these resources requires an understanding of their respective strengths, data structures, and access protocols, which are detailed herein to empower researchers in designing robust multi-omics studies.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major Cancer Data Repositories

| Repository | Primary Focus | Sample Types | Key Data Types | Data Access |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA | Molecular characterization of primary tumors | Over 20,000 primary cancer and matched normal samples across 33 cancer types [20] | Genomic, epigenomic, transcriptomic [20] | Public via Genomic Data Commons (GDC) Portal [20] |

| CPTAC | Proteogenomic analysis | Tumor samples previously analyzed by TCGA [21] | Proteomic, phosphoproteomic, genomic [21] [22] | GDC (genomic) & CPTAC Data Portal (proteomic) [22] |

| ICGC ARGO | Translational genomics with clinical outcomes | Target: 100,000 cancer patients with high-quality clinical data [23] | Genomic, transcriptomic, clinical [23] | Controlled via ARGO Data Platform [23] |

| CCLE | Preclinical cancer models | ~1,000 cancer cell lines [24] | Genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, metabolic [24] | Publicly available through Broad Institute [24] |

Table 2: Multi-Omics Data Types Available Across Repositories

| Repository | Genomics | Transcriptomics | Epigenomics | Proteomics | Metabolomics | Clinical Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TCGA | WES, WGS, CNV, SNV [12] [25] | RNA-seq, miRNA-seq [12] [25] | DNA methylation [12] | Limited | Not available | Extensive [12] |

| CPTAC | WES, WGS [22] | RNA-seq [22] | DNA methylation [22] | Global proteomics, phosphoproteomics [21] | Not available | Linked to TCGA clinical data [21] |

| ICGC ARGO | WGS, WES [23] | RNA-seq [23] | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | High-quality, curated [23] |

| CCLE | Exome sequencing, CNV [24] | RNA-seq, microarray [24] | Histone modifications [24] | TMT mass spectrometry [24] | Metabolite abundance [24] | Drug response data [24] |

Data Access Protocols and Integration Methodologies

TCGA Data Download and Preprocessing Protocol

The following protocol provides a streamlined methodology for accessing and processing TCGA data, addressing common challenges researchers face with file organization and multi-omics data integration.

Materials and Reagents

- Computing system with minimum 8GB RAM and 100GB storage capacity

- Stable internet connection for data transfer

- Python (version 3.11.8 or higher) with pandas library

- GDC Data Transfer Tool (v2.3 or higher)

- Jupyter Notebook environment or Snakemake workflow manager (v7.32.4 or higher)

Experimental Procedure

Data Selection and Manifest Preparation

- Access the GDC Data Portal (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/)

- Select cases and files of interest using the repository's filter system

- Add selected files to the cart and download the manifest file

- Download the corresponding sample sheet for metadata

Environment Configuration

- Create a conda environment using the provided YAML file

- Activate the environment:

conda activate TCGAHelper - Configure the directory structure with subfolders for clinicaldata, manifests, and samplesheets

Data Download Execution

- For restricted access data: download and configure the GDC access token

- Modify the

config.yamlfile to specify directories and file names - Execute the download pipeline using the command:

snakemake --cores all --use-conda - The pipeline will automatically:

- Download files using the GDC Data Transfer Tool

- Map opaque file IDs to human-readable case IDs using the sample sheet

- Reorganize the file structure with case IDs as prefixes for intuitive organization [25]

Data Integration for Multi-Omics Analysis

- Utilize the reorganized files for integrated analysis

- For transcriptomic data: process RNA-seq count files using appropriate normalization methods

- For genomic data: extract CNV and mutation data from VCF files

- For epigenomic data: process DNA methylation beta values

- Implement quality control measures as outlined in Section 4.1

Troubleshooting

- If download fails: verify manifest file integrity and network connectivity

- If file mapping fails: ensure sample sheet version matches data release

- For multi-omics integration: verify sample matching using case IDs [25]

CPTAC Data Access and Proteogenomic Integration

Materials and Reagents

- dbGaP authorization for controlled data access (phs001287 for CPTAC 3; phs000892 for CPTAC 2)

- Proteomics data analysis software (MaxQuant, Spectronaut, or similar)

- Genomic Data Commons (GDC) account for genomic data access

Experimental Procedure

Data Access Authorization

- Apply for dbGaP approval for the appropriate CPTAC study

- Once approved, access genomic data via the GDC Data Portal

- Access proteomic data via the CPTAC Data Portal or Proteomic Data Commons (PDC)

Proteomic Data Processing

- Download the Common Data Analysis Pipeline (CDAP) processed data

- Data includes peptide-spectrum-match (PSM) reports and gene-level protein reports

- For raw data processing, note that CDAP includes:

- Peak picking and quantitative data extraction

- Database searching using MS-GF+

- Gene-based protein parsimony

- False discovery rate (FDR)-based filtering

- Phosphosite localization using PhosphoRS [21]

Proteogenomic Integration

- Map proteomic data to genomic features using gene identifiers

- Integrate protein abundance with mutation and copy number data

- Perform correlation analysis between transcriptomic and proteomic profiles

- Identify post-translational modifications associated with genomic alterations

Applications in Multi-Omics Research The CPTAC resource enables proteogenomic analyses that directly link genomic alterations to protein-level functional consequences. This is particularly valuable for identifying:

- Protein biomarkers associated with specific genomic subtypes

- Signaling pathways activated at the protein level but not apparent at the transcript level

- Therapeutic targets amenable to protein-directed therapies [21] [22]

Multi-Omics Study Design and Quality Control

Guidelines for Robust Multi-Omics Integration

Recent research has established evidence-based guidelines for multi-omics study design (MOSD) to ensure robust and reproducible results. Based on comprehensive benchmarking across multiple TCGA cancer datasets, the following criteria are recommended:

Computational Factors

- Sample Size: Minimum of 26 samples per class to ensure statistical power [12]

- Feature Selection: Select less than 10% of omics features to reduce dimensionality and improve performance by up to 34% [12]

- Class Balance: Maintain sample balance under a 3:1 ratio between classes [12]

- Noise Characterization: Keep noise level below 30% for reliable clustering results [12]

Biological Factors

- Cancer Subtype Combinations: Carefully consider biological relevance when combining subtypes

- Omics Combinations: Select complementary omics layers that address specific research questions

- Clinical Correlation: Integrate molecular subtypes, pathological stage, and other clinical features [12]

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Data Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| GDC Data Transfer Tool | Bulk download of TCGA data | Efficient retrieval of large genomic datasets [25] |

| TCGAutils | Mapping file IDs to case IDs | Data organization and patient-level integration [25] |

| Common Data Analysis Pipeline (CDAP) | Standardized proteomic data processing | Uniform analysis of CPTAC mass spectrometry data [21] |

| MOVICS Package | Multi-omics clustering integration | Identification of molecular subtypes using 10 algorithms [26] |

| MS-GF+ | Database search for mass spectrometry data | Peptide identification in proteomic studies [21] |

| PhosphoRS | Phosphosite localization | Mapping phosphorylation sites in phosphoproteomic data [21] |

Quality Assessment and Validation Framework

Technical Validation

- For genomic data: assess sequencing depth, alignment rates, and coverage uniformity

- For proteomic data: evaluate spectrum quality, identification FDR, and quantification precision

- For transcriptomic data: examine read distribution, mapping rates, and batch effects

Biological Validation

- Cross-validate findings across multiple repositories (e.g., TCGA and ICGC)

- Confirm protein-level expression for transcriptomic discoveries using CPTAC data

- Validate mechanistic insights using CCLE models for functional studies

Visualization of Multi-Omics Data Integration Workflow

Diagram 1: Multi-Omics Data Integration Workflow. This workflow illustrates the systematic process for integrating data from multiple cancer repositories, highlighting key computational integration methods and the flow from data acquisition to biological application.

The strategic integration of data from TCGA, CPTAC, ICGC, and CCLE provides unprecedented opportunities for advancing cancer research through multi-omics approaches. By leveraging the complementary strengths of these resources—from TCGA's comprehensive molecular profiling of primary tumors to CPTAC's deep proteomic coverage, ICGC's clinically annotated cohorts, and CCLE's experimentally tractable models—researchers can overcome the limitations of single-omics studies. The protocols and guidelines presented here provide a framework for robust data access, processing, and integration, enabling the identification of molecular subtypes, biomarkers, and therapeutic targets with greater confidence. As these repositories continue to expand and evolve, they will remain indispensable resources for translating genomic discoveries into clinical applications in precision oncology.

The advancement of single-cell technologies has revolutionized biology, enabling the simultaneous measurement of multiple molecular modalities—such as the genome, epigenome, transcriptome, and proteome—from the same cell [27]. This progress has necessitated the development of sophisticated computational integration methods to jointly analyze these complex datasets and extract comprehensive biological insights. Multi-omics data integration describes a suite of computational methods used to harmonize information from multiple "omes" to jointly analyze biological phenomena [28]. The integration approach is fundamentally determined by how the data is collected, leading to two primary classification frameworks: the experimental design framework (Matched vs. Unmatched data) and the computational strategy framework (Vertical vs. Diagonal vs. Horizontal Integration) [5] [29].

Understanding these classifications is crucial for researchers, as the choice of integration methodology directly impacts the biological questions that can be addressed. Matched and vertical integrations leverage the same cell as an anchor, enabling the study of direct molecular relationships within a cell. In contrast, unmatched and diagonal integrations require more complex computational strategies to align different cell populations, expanding the scope of integration to larger datasets but introducing specific challenges [5] [29] [30]. This article provides a detailed overview of these classification schemes, their interrelationships, supported computational tools, and practical protocols for implementation.

Core Classification Frameworks

Classification by Experimental Design: Matched vs. Unmatched Data

The nature of the experimental data collection defines the first layer of classification, determining which integration strategies can be applied.

Matched Multi-Omics Data refers to experimental designs where multiple omics modalities are measured simultaneously from the same individual cell [5] [28]. Technologies such as CITE-seq (measuring RNA and protein) and SHARE-seq (measuring RNA and chromatin accessibility) generate this type of data [31] [27]. The key advantage of matched data is that the cell itself serves as a natural anchor for integration, allowing for direct investigation of causal relationships between different molecular layers within the same cellular context [5] [30].

Unmatched Multi-Omics Data arises when different omics modalities are profiled from different sets of cells [5]. These cells may originate from the same sample type but are processed in separate, modality-specific experiments. While technically easier to perform, as each cell can be treated optimally for its specific omic assay, unmatched data presents a greater computational challenge because there is no direct cell-to-cell correspondence to use as an anchor for integration [5].

Classification by Computational Strategy: Vertical, Diagonal, and Horizontal Integration

The computational approach used to combine the data forms the second classification layer, which often correlates with the experimental design.

Vertical Integration is the computational strategy used for matched multi-omics data [5]. It merges data from different omics modalities within the same set of samples, using the cell as the anchor to bring these omics together. This approach is equivalent to matched integration and is ideal for studying direct regulatory relationships, such as how chromatin accessibility influences gene expression in a specific cell type [5] [31].

Diagonal Integration is the computational strategy for unmatched multi-omics data [5] [29]. It involves integrating different omics modalities measured from different cells or different studies. Since the cell cannot be used as an anchor, diagonal methods must project cells from each modality into a co-embedded space to find commonalities, such as shared cell type or state structures [5] [29]. This approach greatly expands the scope of possible data integration but is considered the most technically challenging.

Horizontal Integration, while not the focus of this article, is mentioned for completeness. It refers to the merging of the same omic type across multiple datasets (e.g., integrating two scRNA-seq datasets from different studies) and is not considered true multi-omics integration [5].

Table 1: Relationship Between Experimental Design and Computational Strategy

| Experimental Design | Computational Strategy | Data Anchor | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matched (Same cell) | Vertical Integration | The cell itself | Studying direct molecular relationships within a cell |

| Unmatched (Different cells) | Diagonal Integration | Co-embedded latent space | Integrating large-scale datasets from different experiments |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between these core classifications and their defining characteristics.

Diagram 1: Multi-omics integration classifications and relationships. (Clickable nodes)

Computational Tools and Methodologies

A wide array of computational tools has been developed to handle the distinct challenges of vertical and diagonal integration. These tools employ diverse algorithmic approaches, from matrix factorization to deep learning.

Tools for Matched/Vertical Integration

Vertical integration methods are designed to analyze multiple modalities from the same cell. They can be broadly categorized by their underlying algorithmic approach [5] [31].

Table 2: Selected Tools for Matched/Vertical Integration

| Tool | Methodology | Supported Modalities | Key Features | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOFA+ | Matrix Factorization (Factor analysis) | mRNA, DNA methylation, Chromatin accessibility | Infers latent factors capturing variance across modalities; Bayesian framework. | [5] |

| Seurat v4/v5 | Weighted Nearest Neighbours (WNN) | mRNA, Protein, Chromatin accessibility, spatial | Learns modality-specific weights; integrates with spatial data. | [5] [31] |

| totalVI | Deep Generative (Variational autoencoder) | mRNA, Protein | Models RNA and protein count data; scalable and flexible. | [5] [31] |

| scMVAE | Variational Autoencoder | mRNA, Chromatin accessibility | Flexible framework for diverse joint-learning strategies. | [5] [31] |

| BREM-SC | Bayesian Mixture Model | mRNA, Protein | Quantifies clustering uncertainty; addresses between-modality correlation. | [5] [31] |

| citeFUSE | Network-based Method | mRNA, Protein | Enables doublet detection; computationally scalable. | [5] [31] |

Tools for Unmatched/Diagonal Integration

Diagonal integration methods project cells from different modalities into a common latent space, often using manifold alignment or other machine learning techniques [5] [29].

Table 3: Selected Tools for Unmatched/Diagonal Integration

| Tool | Methodology | Supported Modalities | Key Features | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLUE | Variational Autoencoders | Chromatin accessibility, DNA methylation, mRNA | Uses prior biological knowledge (e.g., regulatory graph) to guide integration. | [5] |

| Pamona | Manifold Alignment | mRNA, Chromatin accessibility | Aligns data in a low-dimensional manifold; can incorporate partial prior knowledge. | [5] [29] |

| Seurat v3/v5 | Canonical Correlation Analysis (CCA) / Bridge Integration | mRNA, Chromatin accessibility, Protein, DNA methylation | Identifies linear relationships between datasets; bridge integration for complex designs. | [5] |

| LIGER | Integrative Non-negative Matrix Factorization (NMF) | mRNA, DNA methylation, Chromatin accessibility | Identifies both shared and dataset-specific factors. | [5] |

| UnionCom | Manifold Alignment | mRNA, DNA methylation, Chromatin accessibility | Projects datasets onto a common low-dimensional space. | [5] |

| StabMap | Mosaic Data Integration | mRNA, Chromatin accessibility | For mosaic integration designs with sufficient dataset overlap. | [5] |

Practical Protocols for Multi-Omics Integration

This section outlines detailed, step-by-step protocols for performing vertical and diagonal integration, providing a practical guide for researchers.

Protocol 1: Vertical Integration for Matched Single-Cell Multi-Omics Data

Objective: To integrate two matched omics layers (e.g., scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq from the same cells) to define a unified representation of cellular states [5] [31].

Reagent Solutions:

- Computational Environment: R (v4.0+) or Python (v3.8+).

- Software/Tools: Seurat (R) or SCIM (Python).

- Input Data: A count matrix for each modality (e.g., RNA and ATAC), from the same set of cells. Cell barcodes must match across matrices.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing & Normalization: Independently preprocess each modality.

- For scRNA-seq: Normalize data (e.g., using log normalization), and identify highly variable features.

- For scATAC-seq: Term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) normalization is typically used. Reduce dimensionality via singular value decomposition (SVD) on the TF-IDF matrix.

- Dimension Reduction: Perform linear dimension reduction on each modality (e.g., PCA for RNA, SVD for ATAC).

- Identify Integration Anchors: Identify "anchors" or pairs of cells from the same cell across the two modalities. Seurat v4, for instance, uses a weighted nearest neighbours (WNN) approach to find these anchors and learn a function that defines a cell's state based on a weighted combination of both modalities [5] [31].

- Data Integration: Use the anchors to integrate the two datasets. This step filters the data and creates an integrated matrix where the two modalities are represented in a shared space.

- Downstream Analysis: Perform unified downstream analysis on the integrated embedding.

- Clustering: Use graph-based clustering methods (e.g., Louvain) on the integrated space to identify cell populations.

- Visualization: Generate a unified UMAP or t-SNE plot visualizing cells based on the integrated data from both modalities.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

Diagram 2: Vertical integration workflow for matched data.

Protocol 2: Diagonal Integration for Unmatched Single-Cell Multi-Omics Data

Objective: To integrate two unmatched omics layers (e.g., scRNA-seq from one set of cells and scATAC-seq from another) by projecting them into a common latent space to identify shared cell states [5] [29].

Reagent Solutions:

- Computational Environment: Python (v3.8+).

- Software/Tools: GLUE or Pamona.

- Input Data: A feature-by-cell matrix for each modality, from different sets of cells. No shared cell barcodes are required.

Procedure:

- Independent Feature Selection & Preprocessing: Process each dataset independently.

- Select biologically relevant features (e.g., highly variable genes for RNA, accessible peaks for ATAC).

- Normalize each dataset according to its specific standards.

- Manifold Learning / Representation Learning: Project each modality into its own lower-dimensional manifold to preserve the intrinsic cell-state structure within each dataset. This can be done using methods like PCA, autoencoders, or diffusion maps [29].

- Manifold Alignment / Co-Embedding: This is the core step of diagonal integration. Use an algorithm (e.g., GLUE, Pamona) to align the two independent manifolds into a single, common latent space. The alignment is guided by the principle that cells of the same type should be close in this new space, even if they originated from different modalities [5] [29].

- Note: Some methods, like GLUE, can incorporate prior biological knowledge (e.g., known gene-regulatory links) to guide and improve the alignment [5].

- Cell State Correspondence & Validation: Analyze the co-embedded space.

- Identify clusters containing cells from both modalities, which represent shared cell types or states.

- Crucially, validate the results. Due to the risk of artificial alignments, use prior knowledge (e.g., known cell-type markers) or, if available, a small set of jointly profiled cells as a "ground truth" benchmark to assess the biological accuracy of the alignment [29].

- Biological Inference: Once a valid integration is achieved, transfer information across modalities. For example, impute chromatin accessibility patterns for the RNA-seq cells, or predict gene expression for the ATAC-seq cells, to generate hypotheses about gene regulation.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

Diagram 3: Diagonal integration workflow for unmatched data.

Challenges, Pitfalls, and Future Directions

Despite rapid methodological advances, several significant challenges remain in multi-omics integration.

A critical pitfall for diagonal integration is the risk of artificial alignment [29]. Since these methods rely on mathematical optimization to find a common space, they can sometimes produce alignments that are mathematically optimal but biologically incorrect. For instance, a method might incorrectly align excitatory neurons from a transcriptomic dataset with inhibitory neurons from an epigenomic dataset if the mathematical structures are similar [29]. Therefore, incorporating prior knowledge is essential for reliable results. This can be achieved by:

- Using Partially Shared Features: Leveraging a minimal set of features known to be related across modalities (e.g., linking a gene to its regulatory regions) [29].

- Using Cell Anchors or Labels: Utilizing a small set of jointly profiled cells or known cell-type labels to guide the integration in a semi-supervised manner [29].

Other pervasive challenges include [5] [32] [28]:

- Technical Noise and Batch Effects: Each omics modality has unique technical noise, batch effects, and data distributions that complicate integration.

- Data Sparsity and Missing Values: Single-cell data is inherently sparse, with "dropout" events where molecules are not detected. This problem is compounded when integrating multiple sparse modalities.

- Dimensionality and Scalability: The high dimensionality of omics data and the increasing scale of datasets (millions of cells) demand computationally efficient algorithms.

- Interpretability: The "black box" nature of some complex models, like deep neural networks, can make it difficult to extract biologically meaningful insights from the integrated output.

Future directions point towards the increased use of deep generative models, more sophisticated ways of incorporating prior biological knowledge directly into integration models, and the development of robust benchmarking standards to guide method selection and evaluation [29] [31].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Computational Reagents for Multi-Omics Integration

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function | Ideal Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seurat Suite (v3-v5) | Comprehensive Toolkit | Provides functions for both vertical (WNN) and diagonal (CCA, Bridge) integration. | General-purpose integration for RNA, ATAC, and protein data; widely supported. |

| MOFA+ | Unsupervised Model | Discovers latent factors driving variation across multiple omics datasets. | Exploratory analysis to identify key sources of technical and biological variation. |

| GLUE | Diagonal Integration | Guides integration using a prior graph of known inter-omic relationships (e.g., TF-gene links). | Integrating epigenomic and transcriptomic data with regulatory biology focus. |

| totalVI | Deep Generative Model | End-to-end probabilistic modeling of CITE-seq (RNA+Protein) data. | Analysis of matched single-cell RNA and protein data. |

| Pamona | Manifold Alignment | Aligns datasets by preserving both global and local structures in the data. | Integrating unmatched datasets where complex, non-linear relationships are expected. |

| StabMap / COBOLT | Mosaic Integration | Integrates datasets with only partial overlap in measured modalities across samples. | Complex experimental designs where not all omics are profiled on all samples. |

The fundamental challenge in modern biology is bridging the gap between an organism's genetic blueprint (genotype) and its observable characteristics (phenotype). This relationship is rarely straightforward, being mediated by complex, dynamic interactions across multiple molecular layers. Multi-omics data integration represents the concerted effort to measure and analyze these different biological layers—genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics—on the same set of samples to create a unified model of biological function [4] [33]. The primary objective is to move beyond the limitations of single-data-type analyses, which provide only fragmented insights, toward a holistic systems biology perspective that can capture the full complexity of living organisms [34].

This approach is transformative for precision medicine, where matching patients to therapies based on their complete molecular profile can significantly improve treatment outcomes [4]. The central hypothesis is that phenotypes, especially complex diseases, emerge from interactions across multiple molecular levels, and therefore, understanding these phenotypes requires integrating data from all these levels simultaneously [35]. This protocol details the methods and analytical frameworks required to overcome the substantial technical and computational barriers in connecting genotype to phenotype through multi-omics integration.

Quantitative Challenges in Multi-Omics Data

The integration of multi-omics data presents significant quantitative challenges primarily stemming from the enormous scale, heterogeneity, and technical variability inherent in each data type [4]. The table below summarizes the key characteristics and challenges associated with each major omics layer.

Table 1: Characteristics and Challenges of Major Omics Data Types

| Omics Layer | Measured Entities | Data Scale & Characteristics | Primary Technical Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomics | DNA sequence, genetic variants (SNPs, CNVs) | Static blueprint; ~3 billion base pairs (WGS); identifies risk variants [4] | Data volume (~100 GB per genome); variant annotation and prioritization [4] |

| Epigenomics | DNA methylation, histone modifications, chromatin structure | Dynamic regulation; influences gene accessibility without changing DNA sequence [36] | Capturing tissue-specific patterns; connecting modifications to gene regulation [36] |

| Transcriptomics | RNA sequences, gene expression levels | Dynamic activity; measures mRNA levels reflecting real-time cellular responses [4] | Normalization (e.g., TPM, FPKM); distinguishing isoforms; short read limitations [4] [34] |

| Proteomics | Proteins, post-translational modifications | Functional effectors; reflects actual physiological state [4] | Coverage limitations; dynamic range; quantifying modifications [4] |

| Metabolomics | Small molecules, metabolic intermediates | Downstream outputs; closest link to observable phenotype [4] | Chemical diversity; rapid turnover; database completeness [4] |

The data heterogeneity problem is particularly daunting—each biological layer tells a different part of the story in its own "language" with distinct formats, scales, and biases [4]. Furthermore, missing data is a constant issue in biomedical research, where a patient might have genomic data but lack proteomic measurements, potentially creating serious biases if not handled with robust imputation methods [4]. Batch effects introduced by different technicians, reagents, or sequencing machines create systematic noise that can obscure true biological variation without proper statistical correction [4].

Protocol for Multi-Omics Integration: A Step-by-Step Guide

Experimental Design and Sample Preparation

Proper experimental design is foundational to successful multi-omics integration. The following workflow outlines the critical steps from sample collection to data generation:

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Multi-Omics Sample Preparation

- Sample Collection and Preservation: Collect biological samples (tissues, blood, cells) from the same source under standardized conditions. Immediately stabilize nucleic acids, proteins, and metabolites using appropriate preservatives or flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen [33].

- Simultaneous Biomolecule Extraction: Whenever possible, use integrated extraction kits that partition a single sample aliquot into nucleic acid, protein, and metabolite fractions to minimize technical variability [33].

- Multi-Omics Data Generation: Process each fraction through appropriate technologies:

- Genomics/Epigenomics: Whole genome sequencing (WGS) using Illumina or PacBio platforms; chromatin conformation capture (Hi-C) for 3D genome structure; bisulfite sequencing for methylation [36].

- Transcriptomics: RNA sequencing (RNA-seq); single-cell RNA-seq for cellular heterogeneity; spatial transcriptomics for tissue context [34].

- Proteomics: Mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) with isobaric tagging (TMT) for multiplexing; antibody-based arrays for targeted quantification [4].

- Metabolomics: Liquid or gas chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS/GC-MS) for broad coverage of small molecules [4].

Data Preprocessing and Harmonization

Before integration, each omics dataset requires specialized preprocessing to ensure quality and comparability:

Quality Control: Apply technology-specific quality metrics:

- Sequencing Data: FastQC for read quality; Picard for duplication rates; verify expected insert sizes.

- Proteomics/MS Data: Monitor ion chromatogram quality; peptide identification confidence scores; protein false discovery rates.

- Metabolomics: Evaluate peak shapes; internal standard recovery; signal drift.

Normalization and Batch Correction:

- RNA-seq: Apply normalization methods (e.g., TPM, FPKM) to enable cross-sample comparison [4].

- Proteomics: Perform intensity normalization and correct for batch effects using variance-stabilizing normalization.

- Batch Effect Removal: Apply statistical correction methods like ComBat or remove unwanted variation (RUV) to eliminate technical artifacts [4].

Data Harmonization: Transform diverse datasets into compatible formats for integration. This includes gene annotation unification, missing value imputation using k-nearest neighbors (k-NN) or matrix factorization, and feature alignment across platforms [4].

Integration Methodologies

Three primary computational strategies exist for integrating preprocessed multi-omics data, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

Table 2: Multi-Omics Data Integration Strategies

| Integration Strategy | Timing of Integration | Key Advantages | Common Algorithms & Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration (Concatenation-based) | Before analysis | Captures all potential cross-omics interactions; preserves raw information | Simple feature concatenation; Regularized Canonical Correlation Analysis (rCCA) [33] |

| Intermediate Integration (Transformation-based) | During analysis | Reduces complexity; incorporates biological context through networks | Similarity Network Fusion (SNF); Multi-Omics Factor Analysis (MOFA) [4] [33] |

| Late Integration (Model-based) | After individual analysis | Handles missing data well; computationally efficient; robust | Ensemble machine learning; stacking; majority voting [4] |

Figure 2: Multi-Omics Data Integration Strategies

AI-Driven Integration and Analysis

Artificial intelligence and machine learning provide essential tools for tackling the complexity of multi-omics data, acting as powerful detectors of subtle patterns across millions of data points that are invisible to conventional analysis [4] [35].

Machine Learning Approaches

- Autoencoders (AEs) and Variational Autoencoders (VAEs): These unsupervised neural networks compress high-dimensional omics data into a dense, lower-dimensional "latent space," making integration computationally feasible while preserving key biological patterns [4].

- Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs): Designed for network-structured data, GCNs represent genes and proteins as nodes and their interactions as edges, learning from this structure to make predictions about biological function and disease association [4].

- Similarity Network Fusion (SNF): This method creates a patient-similarity network from each omics layer and then iteratively fuses them into a single comprehensive network, enabling more accurate disease subtyping and prognosis prediction [4].