Navigating the Multi-Omics Revolution: Strategies for Managing High-Dimensional Data in Biomedical Research

The surge in high-throughput technologies has generated vast amounts of multi-omics data, presenting both unprecedented opportunities and significant challenges for researchers and drug development professionals.

Navigating the Multi-Omics Revolution: Strategies for Managing High-Dimensional Data in Biomedical Research

Abstract

The surge in high-throughput technologies has generated vast amounts of multi-omics data, presenting both unprecedented opportunities and significant challenges for researchers and drug development professionals. This article provides a comprehensive guide to managing high-dimensional omics data, from foundational concepts to advanced applications. We explore the fundamental characteristics of omics data and the bottlenecks in its analysis, detail the latest computational tools and integration methodologies for various research objectives, offer practical solutions for common data pitfalls and optimization strategies, and finally, establish frameworks for rigorous validation and comparative analysis to ensure biologically meaningful and reproducible discoveries. This resource is designed to equip scientists with the knowledge to effectively harness multi-omics data for advancing personalized medicine and therapeutic development.

Understanding the Omics Landscape: From Data Generation to Analysis Bottlenecks

Core Omics Disciplines: Definitions and Technologies

High-dimensional omics technologies provide a comprehensive, system-wide view of biological molecules, enabling researchers to move beyond studying single molecules to understanding complex interactions within cells and tissues [1].

Table 1: The Four Core Omics Disciplines

| Omics Field | Definition & Scope | Key Measurement Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Genomics | The study of the complete sequence of DNA in a cell or organism, including genes, non-coding regions, and structural elements [1]. | Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) chips, DNA sequencing (Next-Generation Sequencing), whole-genome sequencing [1]. |

| Transcriptomics | The study of the complete set of RNA transcripts (mRNA, rRNA, tRNA, miRNA, and other non-coding RNAs) produced by the genome [1]. | Microarrays, RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) [1]. |

| Proteomics | The study of the complete set of proteins expressed by a cell, tissue, or organism, including post-translational modifications and protein interactions [1]. | Mass spectrometry, protein microarrays, selected reaction monitoring (SRM) [1]. |

| Metabolomics | The study of the complete set of small-molecule metabolites (e.g., sugars, lipids, amino acids) found within a biological sample [1]. | Mass spectrometry, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy [1]. |

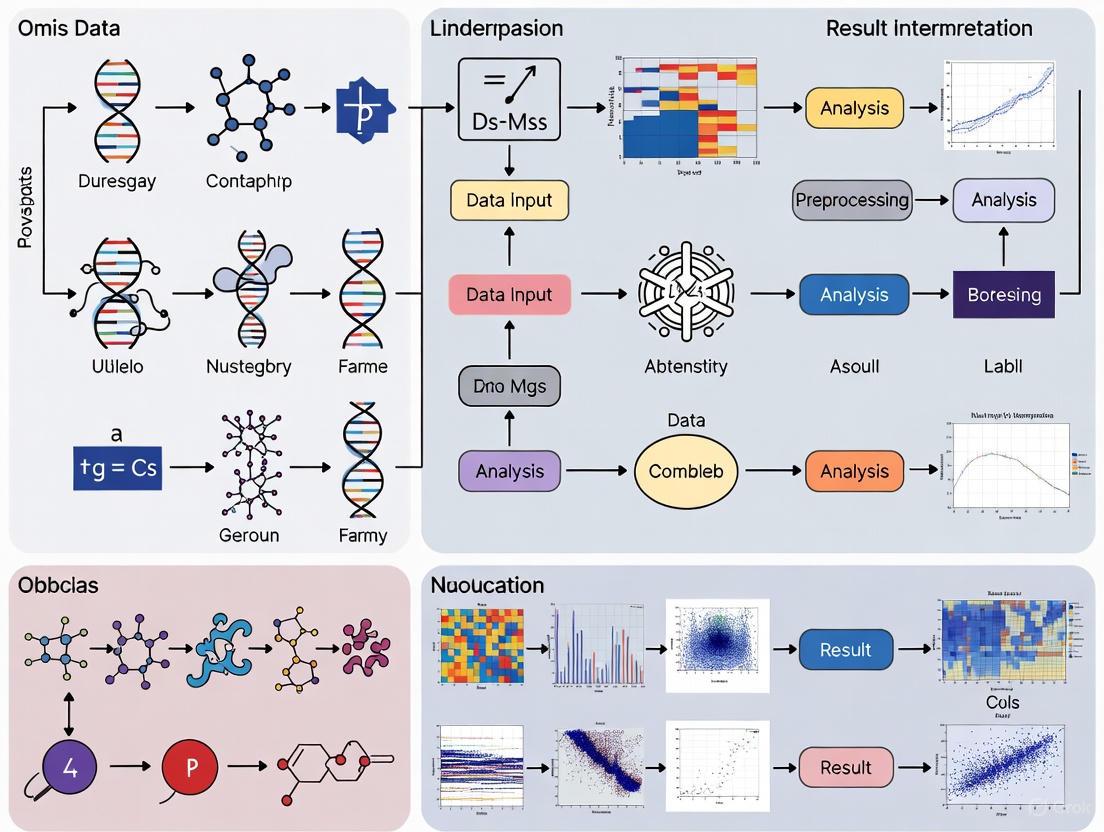

Figure 1: Omics disciplines and their primary measurement technologies.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

Q: What are the common approaches for integrating multiple omics datasets?

There are two primary approaches for multi-omics integration [2]:

1. Knowledge-Driven Integration: This approach uses prior biological knowledge from established databases (like KEGG metabolic networks, protein-protein interactions, or TF-gene-miRNA interactions) to link key features across different omics layers. This method helps identify activated biological processes but is mainly limited to model organisms and carries the bias of existing knowledge [2].

2. Data & Model-Driven Integration: This approach applies statistical models or machine learning algorithms to detect key features and patterns that co-vary across omics layers. It is not confined to existing knowledge and is more suitable for novel discovery. However, a wide variety of methods exist with no consensus approach, and each carries its own model assumptions and pitfalls [2].

Q: How should I handle missing values in my lipidomics or metabolomics data?

Missing values are common in omics data and require careful handling [3]:

- Identify the Nature of Missing Values: Determine if data are Missing Completely at Random (MCAR), Missing at Random (MAR), or Missing Not at Random (MNAR). MNAR often occurs when analyte abundance falls below the detection limit [3].

- Apply Appropriate Imputation: For MNAR data (common when concentrations are below detection limits), imputation with a percentage of the lowest concentration (half-minimum method) often works well. For MCAR/MAR data, k-nearest neighbors (kNN) or random forest imputation methods are generally recommended [3].

- Filter Before Imputation: Remove variables (lipids/metabolites) with excessive missing values (e.g., >35%) before performing imputation [3].

Q: My multi-omics data shows batch effects. How can I normalize this data effectively?

Data normalization aims to remove unwanted technical variation while preserving biological signal [3]:

- Use Quality Control (QC) Samples: Incorporate QC samples prepared from pooled aliquots of all biological samples or certified reference materials throughout your acquisition sequence [3].

- Apply Appropriate Normalization Methods:

- For scRNA-seq, scATAC-seq, and spatial transcriptomics: Log normalization is typically applied [4].

- For antibody-derived tag (ADT) data: Use centered log-ratio (CLR) transformation [4].

- For bulk RNA-seq and NanoString GeoMx data: Apply trimmed mean of M-values (TMM) normalization for dimensional reduction analysis [4].

- Leverage Visualization Tools: Use principal component analysis (PCA) and quality control trend plots to detect and correct for batch effects or systematic drift early in the preprocessing pipeline [5].

Q: Which computational tools are recommended for analyzing and visualizing omics data?

Table 2: Essential Tools for Omics Data Analysis

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| R & Python | Programming Languages | Statistical analysis and visualization of omics data | Extensive packages for specialized analyses; enable reproducible research [5] [3]. |

| OmicsAnalyst | Web Platform | Data & model-driven multi-omics integration | Interactive 3D visual analytics, correlation networks, dual-heatmap viewer [2]. |

| OmnibusX | Desktop Application | Unified multi-omics analysis platform | Code-free analysis; integrates Scanpy, Seurat; privacy-focused local processing [4]. |

| MetaboAnalyst | Web Platform | Metabolomics data analysis | Comprehensive pipeline from data upload to visualization [3]. |

| GitBook Resources | Code Repository | Lipidomics/metabolomics data processing | Step-by-step R/Python notebooks for beginners [5] [3]. |

Figure 2: Omics data processing workflow with key troubleshooting checkpoints.

Q: What are the FAIR data principles and why are they important for omics research?

FAIR data principles are essential for maximizing the value and longevity of omics data [6]:

- Findable: Data and metadata should be easily locatable by both humans and computers, typically through persistent identifiers and rich descriptions.

- Accessible: Data should be retrievable using standardized protocols, even if access restrictions exist.

- Interoperable: Data should integrate with other datasets and applications through use of shared languages and vocabularies.

- Reusable: Data should have rich metadata and clear usage licenses to enable future replication and combination.

These principles extend data utility beyond original research purposes and are increasingly mandated by major funders including the NIH, NSF, and Horizon Europe [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Omics Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function in Omics Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| NIST SRM 1950 | Certified reference material for metabolomics/lipidomics of plasma samples | Used for quality control and normalization; helps evaluate technical variability [3]. |

| Ensembl Annotation Files | Standardized gene annotations for genomic and transcriptomic data | Provides consistent gene symbols and IDs; version 111 is current standard [4]. |

| Hashtag Oligos (HTOs) | Sample multiplexing in single-cell experiments | Enables pooling of multiple samples; demultiplexing performed computationally [4]. |

| Curated Marker Sets | Cell type identification in single-cell genomics | Provides reference signatures for automated cell type prediction [4]. |

| Quality Control (QC) Samples | Pooled sample aliquots for monitoring technical variance | Critical for evaluating data quality across acquisition batches [3]. |

Data Management & Visualization Best Practices

Data Management Protocols:

- Implement Rich Metadata Capture: Document experimental steps thoroughly using relational database structures to link metadata from multi-step experiments. This practice is crucial for interoperability and correct data interpretation by future users [6].

- Ensure Data Privacy: For clinical or sensitive data, use locally executable software solutions like OmnibusX that process data on-premises without external data transfer [4].

- Adopt Standardized Gene Identifiers: Use current Ensembl releases (version 111) and map older identifiers to current standards to ensure accurate gene annotation across datasets [4].

Visualization Guidelines:

- Optimize Color Selection: Use shades of blue rather than yellow for quantitative node encoding in networks. For link colors, choose complementary colors rather than similar hues to enhance discriminability [7].

- Manage Data Volume: For interactive 3D visualizations, limit total data points to less than 5,000 to maintain responsive performance [2].

- Leverage Multiple Plot Types: Utilize volcano plots for differential analysis, PCA for quality control, heatmaps for pattern visualization, and lipid maps for class-specific trends [5] [3].

Effective management of high-dimensional omics data requires both technical expertise in specialized methodologies and strategic implementation of data management principles. By adopting the troubleshooting approaches, analytical tools, and visualization practices outlined above, researchers can navigate the complexities of multi-omics research while ensuring their data remains accessible, interpretable, and valuable for future scientific discovery.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary types of bottlenecks in modern multi-omics research? The bottleneck in omics research has shifted from the technical generation of data to the computational and analytical challenges of integration and interpretation [8]. The main bottlenecks now include:

- Data Integration: Combining heterogeneous data types (e.g., genomics, proteomics, metabolomics) with different scales, distributions, and levels of noise [8] [9].

- Interpretation: Translating integrated data into biologically meaningful insights, mechanistic understanding, and clinically actionable knowledge [10] [11].

- Workflow Efficiency: Delays caused by serial, ticket-driven data operations where researchers wait for data cleaning, access, and analysis, significantly slowing down research cycles [12].

FAQ 2: Why is multi-omics data integration so challenging from a technical perspective? Multi-omics data integration is complex due to several inherent technical characteristics of the data [8] [9]:

- High Dimensionality (HDLSS): The number of variables (e.g., genes, proteins) vastly exceeds the number of samples, increasing the risk of overfitting and spurious findings.

- Data Heterogeneity: Different omics layers have completely different data types, scales, and distributions.

- Technical Noise: Batch effects, missing values, and varying precision across measurement platforms can obscure biological signals.

- Biological Complexity: Regulatory relationships between different omics layers (e.g., how genomics influences transcriptomics) must be accounted for to achieve a holistic view.

FAQ 3: What are the main strategies for integrating multi-omics data? Integration strategies can be categorized based on when the data from different sources are combined during analysis [8] [13]:

Table 1: Multi-Omics Data Integration Strategies

| Strategy | Description | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Raw or pre-processed data from all omics layers are concatenated into a single matrix before analysis [8] [13]. | Simple to implement [8]. | Creates a complex, high-dimensional matrix; discounts data distribution differences and can be noisy [8]. |

| Intermediate Integration | Data are transformed into new representations, and integration happens during the modeling process, often capturing joint latent structures [8] [13]. | Can reduce noise and dimensionality; captures inter-omics interactions [8]. | Requires robust pre-processing; methods can be complex [8]. |

| Late Integration | Each omics dataset is analyzed separately, and the results (e.g., model predictions) are combined at the end [8] [13]. | Circumvents challenges of assembling different data types [8]. | Fails to capture interactions between different omics layers [8]. |

FAQ 4: How can I address the "large p, small n" problem in my omics dataset? The "large p, small n" (high dimensionality, low sample size) problem can be addressed through a combination of statistical and machine learning techniques [8] [9]:

- Dimensionality Reduction: Use techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or autoencoders to project data into a lower-dimensional space while preserving key information [13].

- Feature Selection: Apply penalized regression methods like LASSO, which shrink the coefficients of non-informative features to zero, to select the most relevant variables [9] [11].

- Regularization: Incorporate penalties into model training to prevent overfitting and improve generalizability.

- Employ Specific Frameworks: Use models designed for high-dimensional data, such as DIABLO (Data Integration Analysis for Biomarker discovery using Latent cOmponents) or MOFA (Multi-Omics Factor Analysis) [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Inconsistent or Inaccurate Results After Data Integration

Symptoms:

- Biomarker lists or pathway analysis results change drastically with slight changes in the data or model parameters.

- Models perform well on training data but poorly on validation data (overfitting).

- Different integration methods yield conflicting biological conclusions.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Check 1: Data Preprocessing

- Action: Ensure consistent and appropriate normalization has been applied to each omics dataset. For RNA-seq data, use methods like DESeq2's median-of-ratios or edgeR's TMM. For proteomics, use quantile normalization or variance-stabilizing normalization [9].

- Rationale: Technical variations like library size or ionization efficiency can confound biological signals without proper normalization.

Check 2: Batch Effect Correction

- Action: Apply batch correction algorithms such as ComBat, Limma's

removeBatchEffect(), or surrogate variable analysis (SVA) to remove non-biological technical variance [9]. - Rationale: Differences in sample processing dates, reagent batches, or sequencing lanes can introduce systematic noise that is mistaken for biological signal.

- Action: Apply batch correction algorithms such as ComBat, Limma's

Check 3: Model Validation

- Action: Implement rigorous validation using held-out test sets or resampling methods like cross-validation. Use performance metrics like AUC-ROC that are robust to class imbalance.

- Rationale: This helps identify and mitigate overfitting, a common issue in high-dimensional data, ensuring model generalizability [8] [9].

Issue 2: Poor Performance of Machine Learning Models on Integrated Omics Data

Symptoms:

- Model accuracy is no better than random chance.

- The model fails to converge during training.

- The model is unstable and produces different results on different training runs.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Check 1: Feature Quality and Selection

- Action: Perform rigorous feature selection to remove non-informative variables before integration and model training. Use domain knowledge or statistical filters to pre-select features.

- Rationale: High-dimensional data contains many irrelevant features that can "confuse" the model and increase noise [10] [13].

Check 2: Data Scaling

- Action: Standardize or normalize features within each omics dataset so that they are on a comparable scale (e.g., using Z-score normalization).

- Rationale: Machine learning algorithms can be sensitive to the scale of input variables. Dominant scales from one omics type can bias the model.

Check 3: Integration Strategy Suitability

- Action: Re-evaluate the choice of integration strategy. If using early integration leads to poor performance, consider an intermediate or late integration approach that better handles data heterogeneity [8].

- Rationale: The simple concatenation of data in early integration can be suboptimal for capturing complex, non-linear relationships across omics layers.

Issue 3: Difficulty in Biologically Interpreting Integrated Model Outputs

Symptoms:

- Models like deep neural networks are "black boxes," providing predictions but no mechanistic insight.

- It is challenging to link key features from the model to established biological pathways or functions.

Diagnosis and Resolution:

- Check 1: Pathway and Network Analysis

- Action: Feed the list of important features (e.g., genes, proteins) identified by your model into topology-based pathway analysis tools such as Signaling Pathway Impact Analysis (SPIA) or similar methods [11].

- Rationale: These methods consider the position, interaction type, and direction of molecules within a pathway, providing a more biologically realistic assessment of pathway dysregulation than simple enrichment analysis.

- Check 2: Use of Explainable AI (XAI) Techniques

- Action: Apply XAI methods like SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) or LIME (Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations) to complex models to determine which input features were most important for a given prediction [10].

- Rationale: XAI can help crack open the "black box" by quantifying feature importance, making complex model outputs more interpretable for biologists and clinicians.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: A Workflow for Topology-Based Multi-Omics Pathway Activation and Drug Ranking

This protocol outlines a methodology for integrating multiple omics layers to calculate pathway activation levels and rank potential therapeutic drugs [11].

1. Objective: To integrate DNA methylation, coding RNA (mRNA), microRNA (miRNA), and long non-coding RNA (lncRNA) data to assess signaling pathway activation and compute a Drug Efficiency Index (DEI) for personalized drug ranking.

2. Materials and Reagents: Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Pathway Analysis

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Oncobox Pathway Databank (OncoboxPD) | A knowledge base of 51,672 uniformly processed human molecular pathways used for pathway activation calculations [11]. |

| SPIA Algorithm | A topology-based method that uses gene expression data and pathway structure to calculate pathway perturbation [11]. |

| Drug Efficiency Index (DEI) Software | Software that analyzes custom expression data to evaluate SPIA scores and statistically evaluate differentially regulated pathways for drug ranking [11]. |

| Normalization Reagents/Algorithms | Platform-specific reagents and software (e.g., DESeq2 for RNA-seq, quantile normalization for proteomics) to normalize raw data before integration [9]. |

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Data Generation and Preprocessing

- Generate profiles for DNA methylation, mRNA, miRNA, and lncRNA from case and control samples.

- Perform platform-specific normalization and quality control on each dataset individually [9].

Step 2: Data Transformation for Integration

- For mRNA data: Use expression values directly.

- For DNA methylation, miRNA, and lncRNA data: Treat these as repressive regulatory layers. Transform their data to reflect their negative regulatory impact on gene expression. The study calculated these SPIA values with a negative sign compared to mRNA-based values:

SPIA_methyl, ncRNA = -SPIA_mRNA[11].

Step 3: Pathway Activation Level (PAL) Calculation

- Use the SPIA algorithm to calculate pathway perturbation scores for each omics layer.

- The SPIA score combines a classical enrichment P-value with a perturbation factor that measures the propagation of expression changes through the pathway topology graph [11].

- The formula for the perturbation factor (PF) for a gene g is:

PF(g) = ΔE(g) + Σ β(g,u) * PF(u) / N_ds(u)whereΔE(g)is the normalized expression change,β(g,u)is the interaction type between gene g and its upstream gene u, andN_ds(u)is the number of downstream genes of u [11].

Step 4: Multi-Omics Data Aggregation

- Aggregate the pathway activation scores from all transformed omics layers (mRNA, methylation, miRNA, lncRNA) into a unified platform.

Step 5: Drug Efficiency Index (DEI) Calculation and Ranking

- Use the DEI software to analyze the integrated pathway activation profiles from your sample against a built-in set of controls.

- The DEI algorithm ranks drugs based on their predicted ability to reverse the disease-specific pathway activation signature toward a normal state [11].

4. Visualization of Workflow: The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of the multi-omics integration and analysis protocol.

Protocol 2: A Deep Learning Framework for Multi-Omics Integration (SynOmics)

This protocol describes using a graph-based deep learning model, SynOmics, to integrate multi-omics data for biomedical classification tasks [14].

1. Objective: To construct a graph convolutional network that models both within-omics and cross-omics feature dependencies for enhanced predictive performance.

2. Materials:

- Software: Python with deep learning libraries (e.g., PyTorch, TensorFlow).

- Omics Data: Matched multi-omics datasets (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) with sample labels.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Data Preprocessing

- Clean, normalize, and scale each omics dataset individually. Handle missing values through imputation or removal.

Step 2: Network Construction

- Construct two types of networks in the feature space:

- Intra-omics Networks: Capture relationships between features within the same omics layer.

- Cross-omics Bipartite Networks: Capture regulatory and interaction relationships between features from different omics layers [14].

- Construct two types of networks in the feature space:

Step 3: Model Training with Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN)

- The SynOmics framework uses a parallel learning strategy where both intra-omics and inter-omics graphs are processed simultaneously at each layer of the GCN.

- The model learns node embeddings that incorporate both the local structure of one omics type and the global structure from cross-omics interactions [14].

Step 4: Model Validation and Interpretation

- Validate the model on held-out test sets for classification accuracy.

- Use feature importance and graph analysis techniques to interpret which intra- and inter-omics interactions were most informative for the prediction.

4. Visualization of Framework: The following diagram outlines the core architecture of the SynOmics integration model.

Statistical and Data Handling Reference

Summary of Common Statistical Challenges and Solutions in Multi-Omics Research Table 3: Statistical Pitfalls and Remedial Strategies for High-Dimensional Omics Data

| Statistical Challenge | Potential Impact on Research | Recommended Solutions & Methods |

|---|---|---|

| High Dimensionality (HDLSS) | Overfitting, spurious associations, reduced model generalizability [8] [9]. | Dimensionality reduction (PCA, Autoencoders), feature selection (LASSO), penalized regression [9] [13]. |

| Batch Effects | False positives/negatives, technical variance mistaken for biological signal [9]. | Batch correction algorithms (ComBat, Limma), study design randomization, SVA [9]. |

| Data Heterogeneity | Inability to directly compare or integrate datasets, leading to biased or incomplete models [8]. | Use of integration frameworks designed for heterogeneity (e.g., MOFA, DIABLO), late or intermediate integration strategies [8] [9]. |

| Missing Values | Reduced sample size, biased parameter estimates if not handled correctly [8]. | Imputation methods (e.g., k-nearest neighbors, matrix completion), or model-based approaches that account for missingness [8]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main computational challenges when analyzing high-dimensional single-cell data, such as from CyTOF or scRNA-seq?

The primary challenges stem from the data's high dimensionality and complex nature. Traditional analysis methods like manual gating become inefficient and biased when dealing with 50+ parameters per cell [15]. Key issues include:

- Dimensionality Explosion: The number of required bivariate plots increases quadratically with the number of measured parameters, making manual analysis laborious and confounded [15].

- Noire: The presence of technical and biological noise can obscure true signals, complicating the identification of genuine cell populations and biomarkers [16].

- Cellular Heterogeneity and Complexity: High-resolution technologies reveal continuous cellular differentiation trajectories and complex subset relationships that are difficult to capture with manual, discrete gating strategies [15].

- Data Scale and Integration: Multiomics studies generate massive, disparate datasets with varying formats, scales, and biological contexts. Integrating these data requires sophisticated computational tools and harmonization efforts [17].

Q2: How can I visualize high-dimensional data to better understand cellular heterogeneity and transitions?

Non-linear dimensionality reduction techniques are essential for visualizing high-dimensional data in two or three dimensions. The table below compares common methods:

| Method | Description | Key Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| t-SNE [15] | t-stochastic neighbor embedding; maps cells to a lower-dimensional space based on pairwise similarities. | Provides intuitive clustering of similar cells; excellent for revealing local structure and distinct populations. | Can be stochastic (results vary per run); less effective at preserving global data structure; perplexity parameter requires tuning. |

| UMAP [15] | Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection; a novel manifold learning technique. | Better preservation of global data structure than t-SNE; faster and more scalable; good resolution of rare and transitional cell types [15]. | |

| PHATE [16] | Potential of Heat Diffusion for Affinity-based Transition Embedding; encodes local and global data structure using a potential distance. | Robust to noise; particularly effective for identifying patterns like branching trajectories (e.g., cell differentiation) [16]. | |

| HSNE [15] | Hierarchical Stochastic Neighbor Embedding; constructs a hierarchy of non-linear similarities. | Enables interactive exploration of large datasets from an overview down to single-cell details; effective for rare cell type identification [15]. |

Q3: Our multi-omics data comes from different cohorts and labs, leading to integration issues. How can this be addressed?

Harmonizing disparate data sources is a central challenge in multi-omics. An optimal approach involves:

- Pre-Integration Harmonization: Collecting multiple omics datasets on the same set of samples where possible [17].

- Integrated Data Processing: Integrating data signals from each omics layer prior to higher-level statistical analysis, rather than analyzing datasets individually and correlating results post-hoc [17].

- Network Integration: Mapping multiple omics datasets onto shared biochemical networks (e.g., connecting transcription factors to their target transcripts or enzymes to their metabolites) to improve mechanistic understanding [17].

- AI and Machine Learning: Leveraging advanced computational tools to detect intricate patterns and interdependencies across the integrated data modalities [17].

Q4: What are the best practices for identifying cell populations in an unbiased way in high-dimensional cytometry data?

Unsupervised clustering methods are recommended to overcome the bias of manual gating [15]. The following table outlines key algorithms:

| Method | Type | Description | Key Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| FlowSOM [15] | Clustering | Uses self-organizing maps trained to detect cell populations. | Fast, scalable method for automatic cell population identification. |

| SPADE [15] | Clustering & Visualization | Creates a hierarchical branched tree representation of cell relationships. | Helps in understanding cellular hierarchy and relationships between subsets. |

| PAGA [15] | Trajectory Inference & Graph Abstraction | Reconstitutes topological information from single-cell data into a graph of cellular relationships. | Provides an interpretable graph-based map of cellular dynamics, such as differentiation trajectories. |

Q5: How can I infer dynamic processes, like cellular differentiation, from static snapshot single-cell data?

Trajectory inference algorithms can reconstruct dynamic temporal ordering from static data. Diffusion Pseudotime (DPT) is a method that investigates continuous cellular differentiation trajectories, allowing researchers to order cells along a pseudo-temporal continuum based on their expression profiles [15]. This is particularly powerful for understanding processes like immune cell differentiation or stem cell development from a single snapshot sample.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Cell Population Separation in Dimensionality Reduction Plots

Problem: Your t-SNE or UMAP plot appears as a single, unresolved blob, making it difficult to distinguish distinct cell populations.

Solution:

- Check Data Preprocessing: Ensure data has been properly transformed (e.g., arcsinh for CyTOF) and normalized. Technical noise can mask biological signals.

- Adjust Algorithm Parameters:

- For t-SNE, try increasing the

perplexityparameter (values between 5-50 are common) and the number ofiterations[15]. Run multiple times to ensure stability. - For UMAP, adjust the

n_neighborsparameter. A lower value emphasizes local structure, while a higher value captures more global structure.

- For t-SNE, try increasing the

- Consider Alternative Methods: If non-linear methods fail, try a different visualization algorithm like PHATE, which is specifically designed to capture continuous trajectories and can be more robust to noise [16].

- Re-evaluate Clustering: The clusters used to color the plot may not be optimal. Experiment with different clustering algorithms (e.g., FlowSOM) or resolution parameters.

Issue: Integrating Disparate Multi-Omics Data Types

Problem: You have genomic, transcriptomic, and proteomic data from the same biological system, but cannot effectively combine them for a unified analysis.

Solution:

- Data Harmonization: Before integration, ensure all datasets are reprocessed with standardized metadata and normalized to account for technical batch effects [17].

- Use Multi-Modal Integration Tools: Employ computational frameworks designed for multi-omics integration rather than analyzing each data type in a siloed workflow [17].

- Leverage Network-Based Integration: Map your various omics datasets (e.g., genes, transcripts, proteins) onto shared biochemical networks. This connects analytes based on known interactions, providing a mechanistic framework for integration [17].

- Apply AI/ML Models: Utilize artificial intelligence and machine learning methods, such as variational autoencoders (VAEs) or graph convolutional networks (GCNs), which are advanced for extracting features and integrating multiple data modalities into a cohesive model [18] [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key reagents and materials used in high-dimensional single-cell and multi-omics research.

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Antibodies Labeled with Metal Isotopes | For mass cytometry (CyTOF); enables simultaneous measurement of >40 protein markers per cell without spectral overlap found in fluorescence-based flow cytometry [15]. |

| Heavy Metal Isotopes | The labels for antibodies in CyTOF; their detection via time-of-flight mass spectrometry allows for high-parameter single-cell proteomic profiling [15]. |

| Single-Cell Multi-Omics Assay Kits | Commercial kits that enable correlated measurements of genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic information from the same single cells [17]. |

| Cell Hash Tagging Antibodies | Antibodies conjugated to oligonucleotides that allow sample multiplexing, reducing batch effects and reagent costs in single-cell sequencing experiments. |

| Viability Stain (e.g., Cisplatin) | A cell membrane-impermeant metal chelator used in CyTOF to identify and exclude dead cells during analysis. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Workflow for High-Dimensional CyTOF Data Analysis

This protocol outlines a standard computational pipeline for analyzing CyTOF data, from raw files to biological insights [15].

Detailed Methodology:

Data Pre-processing & Normalization:

- Load the raw data (FCS files) into your analysis platform (e.g., R, Python, or specialized software like Cytobank).

- Normalize signal intensity across samples to correct for instrument drift and variation using bead-based or standard normalization algorithms.

- Apply an arcsinh transformation with a cofactor (e.g., 5) to stabilize the variance of the measured markers and bring the data to a more Gaussian-like distribution.

Dimensionality Reduction:

- Select the parameters (markers) for analysis, typically those defining cell phenotype and function.

- Run a non-linear dimensionality reduction algorithm such as UMAP or t-SNE on the transformed data to visualize the high-dimensional data in 2D. This step helps reveal the underlying structure and heterogeneity of the cell population.

- Optional: Use PCA as an initial step to reduce computational time for subsequent analyses.

Unsupervised Clustering:

- Apply an automated clustering algorithm like FlowSOM or PhenoGraph to identify distinct cell populations in an unbiased manner. These algorithms group cells based on the similarity of their marker expression profiles.

- Overlay the cluster identities onto the UMAP/t-SNE plot to visualize the results.

Differential Analysis & Biomarker Identification:

- Compare marker expression levels (using statistical tests like t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests) between clusters to identify defining features (biomarkers) for each population.

- Compare the relative abundances of cell populations between different experimental conditions (e.g., healthy vs. diseased).

Trajectory Inference (if applicable):

- For data suggesting continuous processes (e.g., differentiation), use a trajectory inference algorithm like Diffusion Pseudotime (DPT) [15] to reconstruct the cellular progression and order cells along a pseudo-temporal trajectory.

Protocol 2: Integrated Multi-Omics Analysis for Biomarker Discovery

This protocol describes a strategy for integrating multiple omics datasets to discover robust biomarkers and therapeutic targets [17].

Detailed Methodology:

Sample & Data Collection:

- Collect multiple omics datasets (e.g., genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics) from the same set of patient samples to ensure direct comparability.

Data Harmonization & Pre-processing:

- Independently pre-process each omics dataset using established pipelines (e.g., alignment for sequencing data, normalization for proteomics data).

- Perform batch effect correction and data harmonization to account for technical variations across different processing batches or platforms.

Integrated Data Analysis:

- Early Integration: Combine the normalized data matrices from the different omics layers into a single, unified dataset prior to running statistical or machine learning models. This approach allows the model to learn from the combined signal of all modalities simultaneously [17].

- Network Integration: As an alternative or complementary approach, map the analytes from each omics dataset (e.g., differentially expressed genes, proteins) onto a shared interaction network (e.g., protein-protein interaction, metabolic pathway). This contextualizes findings within known biology and can reveal dysregulated network modules.

AI/ML-Based Pattern Recognition:

- Apply machine learning or deep learning models (e.g., autoencoders, graph neural networks) to the integrated data. These models are adept at detecting complex, non-linear patterns that would be impossible to find by analyzing each data type individually [18] [17].

- Use these models for tasks like patient stratification, prediction of disease progression, or identification of master regulatory nodes in the integrated network.

Validation:

- Validate the discovered biomarkers or targets using an independent cohort of samples or through functional experimental studies.

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting High-Dimensional Data Analysis

Reported Issue: Model overfitting and poor generalizability on new datasets.

- Potential Cause: High-dimension low sample size (HDLSS) problem where variables significantly outnumber samples [8].

- Solution:

Reported Issue: Inability to integrate multiple omics data types.

- Potential Cause: Data heterogeneity across different omics platforms and modalities [8].

- Solution:

- Apply data transformation and normalization specific to each omics modality [8].

- Choose appropriate integration strategy (Early, Mixed, Intermediate, Late, or Hierarchical) based on research goals [8].

- Use tools like Multi-Omics Factor Analysis (MOFA) for pattern recognition across omics layers [19].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Computational Infrastructure Limitations

Reported Issue: Insufficient computing power for population-scale omics analysis.

- Potential Cause: Local computational resources cannot handle datasets with thousands of samples and millions of data points [20] [21].

- Solution:

Reported Issue: Long processing times for genome-wide association studies.

- Potential Cause: Standard workstations insufficient for datasets with 1000 individuals and 100,000 SNPs [20].

- Solution:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What strategies can help overcome the high computational costs of omics analysis? A: Several cost-management strategies can improve accessibility:

- Implement pay-as-you-go cloud computing models to avoid large capital investments [21].

- Use data compression algorithms to reduce storage requirements [19].

- Leverage public data repositories like TCGA that offer cloud-based access to minimize data transfer costs [22].

- Apply efficient imputation methods for missing values rather than repeating expensive experiments [8] [19].

Q: How can researchers with limited bioinformatics training analyze complex omics datasets? A: Multiple user-friendly solutions are available:

- Utilize graphical interfaces like EasyOmics that enable point-and-click analysis without coding [20].

- Implement platforms like Omics Playground for interactive visualization and analysis [23].

- Access pre-built workflows on cloud platforms (Terra, DNAnexus) that automate complex analyses [21].

- Employ multivariate data analysis software like SIMCA with specialized omics interfaces [24].

Q: What are the best practices for ensuring statistical rigor in high-dimensional omics studies? A: Follow these established methodologies:

- Apply multiple testing corrections (e.g., Benjamini-Hochberg) to control false discovery rates [19].

- Implement rigorous quality control measures including control samples and replicates [19].

- Use cross-validation and held-out datasets to verify predictions [25].

- Correct for batch effects using methods like quantile normalization and ComBat [19].

Q: How can we effectively integrate multi-omics data from different technological platforms? A: Successful integration requires:

- Standardization using FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles [19].

- Choosing integration methods based on data structure (horizontal vs. vertical integration) [8].

- Using specialized tools for simultaneous visualization of multiple omics types on metabolic networks [26].

- Applying novel approaches like the HYFT framework that tokenizes biological data to a common language [8].

Quantitative Data Tables

Computational Requirements for Omics Analysis

Table 1: Cloud Computing Costs for Different Omics Data Types (Approximate)

| Omics Type | Platform | Data Size | Analysis Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome [22] | DNA sequencing | >100 GB | $40-$66 per test |

| Transcriptome [22] | RNA-seq | >2000 samples | $1.30 per sample |

| Proteome [22] | Protein mass spectrometry | Standard mix dataset | >$1 per database search |

| Metabolite [22] | Metabolite mass spectrometry | ~1 GB | $11 per processing |

| Microbiome [22] | rRNA gene sequencing | >90 GB | ~$8 per GB + $400 prep |

Table 2: Computational Performance Metrics for Omics Analysis

| Analysis Type | Dataset Size | Runtime | RAM Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| GWAS [20] | 1,000 individuals, 100,000 SNPs | <2 minutes | <16 GB |

| GWAS [20] | 1,000 individuals, 10,000,000 SNPs | ~110 minutes | <16 GB |

| OmicQTL [20] | 1,000 individuals, 10M SNPs, 20K features | Hours | ≤15 GB |

| Multi-omics Visualization [26] | 3,209 reactions, 1,796 compounds, 20 timepoints | 20 seconds | Moderate |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Multi-Omics Data Integration and Analysis

Objective: To integrate and analyze datasets from multiple omics platforms (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) for comprehensive biological insight.

Methodology:

- Data Pre-processing

Data Integration Strategy Selection

- Choose based on research question:

- Early Integration: Concatenate all datasets into single matrix [8].

- Mixed Integration: Separately transform each dataset then combine [8].

- Intermediate Integration: Simultaneous integration producing common and omics-specific representations [8].

- Late Integration: Analyze each omics separately then combine predictions [8].

- Hierarchical Integration: Include prior regulatory relationships between omics layers [8].

- Choose based on research question:

Multivariate Data Analysis

Protocol 2: Population-Scale Omics Association Analysis

Objective: To identify genetic variations associated with complex traits using population-scale omics data.

Methodology:

- Data Quality Control and Preparation

Genome-Wide Association Scan

- Implement mixed linear model to detect genetic variations [20].

- Apply Bonferroni-corrected threshold for significance [20].

- Generate Manhattan plots and quantile-quantile (QQ) plots automatically [20].

- Prioritize association signals by statistical significance, physical distance, and linkage disequilibrium [20].

Validation and Interpretation

Visualizations

Multi-Omics Data Integration Workflow

Omics Data Analysis Challenges and Solutions

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Platforms for Omics Research

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Data Analysis Platforms | EasyOmics [20] | User-friendly graphical interface for association analysis without coding |

| Omics Playground [23] | Interactive visualization and analysis platform | |

| SIMCA [24] | Multivariate data analysis software with specialized omics capabilities | |

| Cloud Computing Platforms | Terra [21] | Cloud platform optimized for genomic workflows |

| AWS HealthOmics [21] | Amazon's specialized service for healthcare omics data | |

| Google Cloud Life Sciences [21] | Google's solution for life sciences data analysis | |

| Visualization Tools | Pathway Tools Cellular Overview [26] | Simultaneous visualization of up to four omics data types on metabolic networks |

| Cytoscape [26] | Network visualization and analysis | |

| Escher [26] | Manual creation of pathway diagrams with data overlay | |

| Statistical Analysis | MOFA [19] | Multi-Omics Factor Analysis for identifying patterns across omics layers |

| iCluster [19] | Tool for integrated clustering of multiple omics data types |

Computational Tools and Integration Strategies for Multi-Omics Analysis

In multi-omics research, data integration is the computational process of combining multiple layers of biological information (such as genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and epigenomics) to gain a unified and comprehensive understanding of a biological system. [27] [28]

The core challenge is that each omics layer has a unique data scale, noise ratio, and preprocessing steps, making integration a complex task without a universal one-size-fits-all solution. [27] [29] The choice of integration strategy is primarily determined by how the data was collected—specifically, whether different omics layers were measured from the same cells or from different samples. [27] This article classifies these approaches into three main types: Matched, Unmatched, and Mosaic integration, providing a troubleshooting guide to help you select and successfully apply the correct method for your research.

Comparison of Multi-Omics Integration Types

The following table summarizes the key characteristics, typical use cases, and popular tools for the three primary integration types.

| Integration Type | Data Source & Anchors | Primary Challenge | Example Tools & Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Matched (Vertical) [27] [28] | Data from different omics layers profiled from the same cell or sample. The cell itself is the anchor. [27] | Managing different data scales and noise profiles from multiple modalities measured on the same cell. [27] [29] | Seurat v4 [27], MOFA+ [27] [28], totalVI [27], DCCA [27] |

| Unmatched (Diagonal) [27] [28] | Data from different omics layers profiled from different cells or samples. Requires a computational anchor. [27] | Finding commonality between cells without a biological anchor; often requires projecting cells into a co-embedded space. [27] | GLUE [27], LIGER [27] [30], Pamona [27], Seurat v3 (CCA) [27] [30] |

| Mosaic [31] | Multiple datasets with varying combinations of omics layers. Requires sufficient overlapping features or datasets to connect them. [31] | Integrating datasets where some pairs do not share any direct features ("multi-hop" integration). [31] | StabMap [27] [31], Cobolt [27] [31], MultiVI [27] [31], Bridge Integration [27] [30] |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs and Solutions

Matched (Vertical) Integration

Q: My matched RNA and protein data show poor correlation for key markers. What could be wrong? A: This is a common occurrence, not necessarily an error. A weak correlation can reflect real biology, such as post-transcriptional regulation. Before concluding, troubleshoot the following:

- Check for Sample Misalignment: Ensure the RNA and protein data are truly from the same set of cells and that no sample mix-up occurred. [29]

- Verify Normalization: Confirm that each modality has been properly and independently normalized (e.g., RNA by library size, protein counts by CLR) before integration. Naively concatenating raw counts will skew results. [29]

- Investigate Biology: Use the discordance as a discovery tool. A highly expressed gene with low protein abundance may be subject to rapid degradation or strong microRNA regulation. [29]

Q: When I integrate my matched scRNA-seq and scATAC-seq data, the chromatin accessibility signal dominates the clustering. Why? A: This is often a normalization or scaling issue.

- Cause: The integration method may not be weighting the modalities equally. If one dataset has higher overall variance or was not scaled to a comparable range, it can dominate the shared low-dimensional space. [29]

- Solution: Use integration-aware tools like MOFA+ or Seurat v4 that are designed to handle the distinct statistical properties of each modality. [27] [19] Ensure you follow the tool-specific guidelines for normalizing each data type individually before running the integration workflow. [29]

Unmatched (Diagonal) Integration

Q: I am trying to integrate scRNA-seq from one experiment with scATAC-seq from another, but the cell types won't align. What anchors should I use? A: With unmatched data, the "anchor" is not biological but computational.

- Cause: The algorithm may be failing to find a valid common latent space, often due to strong batch effects or insufficient overlapping biological signal. [27]

- Solution:

- Leverage Manifold Alignment: Use methods like GLUE or Pamona, which project cells from both modalities onto a non-linear manifold to find commonality. [27]

- Incorporate Prior Knowledge: Tools like GLUE can use prior biological knowledge (e.g., gene-to-peak links) to guide the alignment and create a more accurate anchor. [27]

- Apply Batch Correction: Perform batch effect correction within each modality before attempting cross-modal integration to ensure technical differences are minimized. [29]

Q: How can I validate an unmatched integration result if I don't have ground truth? A: While challenging, you can assess integration quality using:

- Label Transfer Accuracy: If you have cell type labels for both datasets, train a classifier on one dataset and see how well it predicts labels in the other, using the integrated space. [31]

- Conservation of Structure: Check if the local neighborhood structure of cells from the same cell type is preserved in the integrated embedding. Good integration should group similar cell types together, regardless of their omics source. [31]

Mosaic Integration

Q: What is "multi-hop" integration, and when is it necessary? A: Multi-hop integration is a specific capability of mosaic integration tools.

- Scenario: You have three datasets: Dataset A (RNA+Protein), Dataset B (RNA+ATAC), and Dataset C (ATAC+Protein). There is no single feature shared by all three, but each pair has an overlap.

- Solution: Mosaic tools like StabMap or Bridge Integration can use Dataset B (RNA+ATAC) as a "bridge" to connect Dataset A and Dataset C. The method traverses the shortest path along this "mosaic data topology" to integrate all datasets into a common space, even without a globally shared feature. [31]

Q: My mosaic integration produces a fragmented embedding where datasets don't mix well. How can I improve stability? A: Fragmentation often occurs when the connections (shared features) between datasets are too weak or few.

- Cause: The mosaic data topology is unstable. If the shared feature set between two key datasets is small or non-informative, the mapping between them becomes unreliable. [31]

- Solution: Use a method like StabMap, which is explicitly designed to stabilize mapping by exploiting both shared and non-overlapping features across the entire topology of datasets, leading to a more robust and coherent integration. [31]

Workflow Diagrams for Integration Strategies

The following diagrams illustrate the logical decision process and core mechanisms for each integration type.

Decision Workflow for Multi-Omics Integration Types

Mechanisms of Matched, Unmatched, and Mosaic Integration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Computational Solutions

The following table lists essential computational tools and conceptual "reagents" crucial for successful multi-omics integration.

| Tool / Solution | Function | Primary Integration Type |

|---|---|---|

| Seurat (v4/v5) [27] [30] | A comprehensive toolkit for single-cell analysis. Provides weighted nearest neighbors (WNN) for matched integration and bridge integration for complex mosaic scenarios. [27] | Matched, Mosaic |

| MOFA+ [27] [28] | A factor analysis model that infers a small number of latent factors that capture the shared and unique sources of variation across multiple omics layers. [27] [28] | Matched |

| StabMap [27] [31] | A mosaic data integration method that projects cells onto a reference by traversing shortest paths along a dataset topology, enabling "multi-hop" integration. [31] | Mosaic |

| GLUE (Graph-Linked Unified Embedding) [27] | A variational autoencoder-based method that uses a prior knowledge graph to link different omics layers, guiding the integration of unmatched data. [27] | Unmatched |

| LIGER (Linked Inference of Genomic Experimental Relationships) [27] [30] | Uses integrative non-negative matrix factorization (iNMF) to identify shared and dataset-specific factors, effective for aligning datasets from different modalities or technologies. [27] [30] | Unmatched |

| Integration Anchors (Conceptual) [27] [29] | The shared features or cells used to align datasets. Correctly identifying and using anchors is critical. These can be biological (the cell) or computational (shared features/latent space). [27] [29] | All Types |

| Cross-Modality Normalization (Conceptual) [32] [29] | The process of scaling different omics data types (e.g., RNA counts, protein counts, ATAC peaks) to a comparable range to prevent one modality from dominating the integrated analysis. [29] | All Types |

The advancement of high-throughput technologies has moved biomedical research into the age of omics, enabling scientists to track molecules such as DNAs, RNAs, proteins, and metabolites for a better understanding of human diseases [33]. However, translating large volumes of omics data into knowledge presents significant challenges, including missing observations, batch effects, and the complexity of choosing appropriate statistical models [33]. Multi-omics characterization of individual cells offers remarkable potential for analyzing the dynamics and relationships of gene regulatory states across millions of cells, but how to effectively integrate multimodal data remains an open problem [34]. This technical support center addresses specific issues researchers encounter when working with state-of-the-art tools for managing high-dimensional omics data, providing practical troubleshooting guides and FAQs framed within the broader context of omics data research management.

MOFA+ Troubleshooting Guide

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: I get the following error when running run_mofa in R: AttributeError: 'module' object has no attribute 'core.entry_point' or ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'mofapy2'

A: This error typically indicates a Python configuration issue. First, restart R and try again. If the error persists, either the mofapy2 Python package is not installed, or R is detecting the wrong Python installation. Specify the correct Python interpreter at the beginning of your R script:

Alternatively, use use_conda() if you work with conda environments. You must install the mofapy2 Python package following the official installation instructions [35].

Q: I encounter installation errors for the MOFA2 R package with messages about unavailable dependencies

A: This occurs when trying to install Bioconductor dependencies using install.packages(). Instead, install these packages directly from Bioconductor:

Replace "DEPENDENCY_NAME" with the specific missing dependencies mentioned in the error message [35].

Q: My R version is older than 4.0. Can I still use MOFA2?

A: Yes, MOFA2 works with R versions 3 and above. You need to clone the repository and edit the DESCRIPTION file:

Edit the Depends option in the DESCRIPTION file to match your R version, then install using:

MOFA-FLEX Experimental Protocol

MOFA-FLEX represents a framework for factor analysis of multimodal data, with a focus on single-cell omics, modeling an observed data matrix as a product of low-rank factor and weight matrices [36]. Below is a detailed methodology for analyzing PBMC multiome data:

1. Data Import and Setup

2. Preprocessing for RNA Modality

3. Preprocessing for ATAC Modality

4. Model Fitting MOFA-FLEX automatically fits the model upon object creation. For normalized data, use a Normal (Gaussian) likelihood, while negative binomial likelihood is more appropriate for unnormalized count data [36].

MOFA+ Integration Workflow

Seurat Troubleshooting Guide

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: After merging multiple samples using the merge() function in Seurat v5.0, I get an error with GetAssayData()

A: In Seurat v5.0, the merge() function creates separate count layers for each sample by default, which prevents GetAssayData() from extracting the matrix. Resolve this by joining the layers before using GetAssayData():

After joining the layers, you can use GetAssayData() without errors. Note that this issue does not occur in Seurat v4 and earlier versions [37].

Q: I experience crashes when running Python-based functions like scVelo or Palantir on macOS

A: This issue differs between Intel and Apple Silicon Macs:

Intel Macs: When using R Markdown in RStudio with Python tools, the R session may crash unexpectedly. Use regular .R script files instead of R Markdown files.

Apple Silicon (M1/M2/M3/M4): If you load R objects before calling Python functions, the R session may crash due to memory management issues. Always initialize the Python environment BEFORE loading any R objects:

Q: I get a GLIBCXX version error when running scVelo-related functions in RStudio on Linux

A: This error occurs because RStudio cannot find the correct shared library 'libstdc++'. Check the library paths with Sys.getenv("LD_LIBRARY_PATH"). Copy the following files from your conda environment lib directory to one of the paths in LD_LIBRARY_PATH:

- libR.so

- libstdc++.so

- libstdc++.so.6

- libstdc++.so.6.0.32

After copying these files, restart your R session [37].

Seurat Data Preprocessing Protocol

1. Data Loading and Initialization

2. Quality Control Metrics

3. Quality Control Understanding

- nFeature_RNA: Number of genes detected per cell (low counts indicate dying cells)

- nCount_RNA: Total molecules detected per cell (high counts may indicate doublets/multiplets)

- percent.mt: Percentage of mitochondrial reads (high percentage indicates poor-quality cells or contamination) [38]

4. Data Filtering and Normalization

Seurat Analysis Workflow

Multi-omics Integration Tools Comparison

Performance Benchmarking of Integration Methods

Recent benchmarking studies evaluate multi-omics integration methods across multiple datasets and performance metrics. The following tables summarize quantitative comparisons based on studies of paired and unpaired single-cell multi-omics data.

Table 1: Performance Comparison on Paired 10x Multiome Data

| Method | Cell-type ASW | Batch ASW | FOSCTTM | Seurat Alignment Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scHyper | High | High | Lowest | Better |

| scJoint | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

| Seurat | Low | Low | High | Low |

| Liger | Low | Low | High | Low |

| Harmony | Low | Moderate | High | Low |

| GLUE | Low | Low | High | Low |

Table 2: Performance on Unpaired Mouse Atlas Data

| Method | Label Transfer Accuracy | Cell-type Silhouette | Batch ASW | FOSCTTM |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| scHyper | 85% | High | High | Lowest |

| GLUE | 77% | Moderate | Moderate | Low |

| scJoint | 72% | High | Moderate | Moderate |

| Conos | 67% | Low | Low | High |

| Harmony | 68% | Low | Moderate | High |

| Seurat | 56% | Low | Low | High |

Table 3: Performance on Multimodal PBMC Data (CITE-seq + ASAP-seq)

| Method | Label Transfer Accuracy | Cell-type Silhouette | Integration Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| scHyper | 86% | High | High |

| scJoint | 84% | Moderate | Moderate |

| GLUE | 80% | Moderate | Moderate |

| Seurat | 75% | Low | Low |

Performance metrics explanation:

- ASW (Average Silhouette Width): Measures separation between cell types (higher is better)

- FOSCTTM (Fraction Of Samples Closer Than The True Match): Measures preservation of biological variation (lower is better)

- Seurat Alignment Score: Measures dataset integration (higher indicates better alignment) [34]

scHyper Integration Protocol

scHyper is a deep transfer learning model for paired and unpaired multimodal single-cell data integration that uses hypergraph convolutional encoders to capture high-order data associations across multi-omics data [34].

Experimental Workflow:

Hypergraph Construction: Create a hypergraph for each modality individually, forming multi-omics hypergraph topology by combining modality-specific hyperedges.

Feature Encoding: Use hypergraph convolutional encoder to capture high-order data associations across multi-omics data.

Transfer Learning: Apply efficient transfer learning strategy for large-scale atlas data integration.

Integration Evaluation: Assess using cell-type silhouette coefficient, ASW for cell types and omics layers, Seurat Alignment Score, and FOSCTTM values.

Key Advantages:

- Effectively handles both paired and unpaired multimodal data

- Achieves high accuracy in label transfer (85% on mouse atlas data)

- Maintains balance between reducing technical variations and preserving cell-type signals

- Demonstrates scalability to large atlas-level datasets [34]

Multi-omics Integration Decision Framework

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Computational Tools for Multi-omics Analysis

| Tool/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| MOFA2/MOFA-FLEX | Factor analysis for multimodal data | Multi-omics integration, dimensionality reduction |

| Seurat | Single-cell RNA-seq analysis | Clustering, visualization, differential expression |

| scHyper | Deep transfer learning for multi-omics | Paired and unpaired data integration |

| GLUE | Graph-linked unified embedding | Multi-omics integration, regulatory inference |

| Scanpy | Single-cell analysis in Python | Preprocessing, visualization, clustering |

| MuData | Multimodal data container | Standardized format for multi-omics data |

| AnnData | Annotated data matrix | Single-cell data representation |

| scVelo | RNA velocity analysis | Cell fate determination, dynamics |

The integration of multi-omics data remains a complex challenge in single-cell research, with various tools offering different strengths and limitations. As demonstrated by the benchmarking results, newer methods like scHyper show promising performance in both paired and unpaired data integration scenarios, particularly for large-scale atlas data [34]. The field continues to evolve with emerging approaches that better balance the reduction of technical variations with the preservation of biological signals.

Successful management of high-dimensional omics data requires not only selecting appropriate tools but also understanding their specific troubleshooting requirements, configuration dependencies, and optimal application contexts. The protocols and troubleshooting guides provided here offer researchers practical solutions for common challenges encountered when working with state-of-the-art multi-omics analysis tools.

As the volume and complexity of omics data continue to grow, developing robust, scalable, and user-friendly integration methods will remain crucial for extracting meaningful biological insights and advancing biomedical research.

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches for Data Fusion

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Scenario 1: Handling Missing or Noisy Multi-Omics Data

- Problem: Your deep learning model for cancer subtyping fails to converge or shows poor performance. Diagnostics reveal your multi-omics dataset (e.g., from TCGA) has missing values in the methylation data and noisy segments in the transcriptomic data.

- Background: High-dimensional omics data is often sparse and heterogeneous. Missing values can arise from experimental limitations, while noise can stem from technical artifacts [39] [40].

- Solution:

- Data Audit: Use summary statistics and visualization (e.g., heatmaps of missingness) to identify patterns. Determine if data is Missing Completely at Random (MCAR) or not.

- Imputation: Apply advanced imputation techniques.

- Robust Modeling: If missingness is significant, employ modeling strategies that are inherently robust, such as:

Troubleshooting Scenario 2: Model Interpretability in a Translational Study

- Problem: You have developed a high-accuracy deep learning model using

Flexynesisto predict drug response from genomic and proteomic data. However, for a publication on precision oncology, reviewers demand insights into the biological mechanisms and features driving the predictions. - Background: A key challenge of deep learning models is their "black box" nature, which limits clinical adoption as professionals require understandable rationale for decisions [43] [41].

- Solution:

- Attention Mechanisms: If your model uses an attention layer, visualize the attention weights to see which features (e.g., specific genes or proteins) the model "attendsto" for each prediction [43] [40].

- Post-hoc Interpretation:

- SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations): Use this method on your trained model to compute the contribution of each input feature to the final prediction for a specific sample.

- Marker Discovery: Utilize built-in functions in frameworks like

Flexynesisthat aid in biomarker discovery from the trained model's weights or through permutation feature importance [41].

- Pathway Enrichment Analysis: Take the top features identified as important for your model's predictions and perform over-representation analysis using databases like KEGG or GO. This translates a list of genes/proteins into biologically meaningful pathways.

Troubleshooting Scenario 3: Inconsistent Multi-Omics Integration in a Single-Cell Study

- Problem: When integrating single-cell RNA-seq and ATAC-seq data to study cellular heterogeneity, the integrated latent space shows poor alignment of modalities, and clusters do not correspond to known cell types.

- Background: Single-cell multi-omics data presents unique challenges in correlating genomic, transcriptomic, and/or epigenomic changes within the same cells. Effective integration requires specialized algorithms to determine which changes co-occur [17].

- Solution:

- Check Data Preprocessing: Ensure proper normalization for each modality and that features are scaled appropriately.

- Algorithm Selection: Move beyond simple correlation-based methods.

- Employ methods designed for unpaired or mosaic data integration, such as UINMF, which can handle features present in only a subset of omics datasets [39].

- Leverage neural network architectures with contrastive learning objectives. These are powerful for creating integrated embeddings by pulling together data points from the same cell while pushing apart those from different cells [39] [40].

- Benchmarking: Use a toolkit that allows for flexible architecture swapping. Benchmark deep learning approaches against classical methods like Random Forests or Survival Models, as they can sometimes outperform more complex models on specific tasks [41].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between early, intermediate, and late fusion strategies, and when should I use each?

The choice of fusion strategy is critical and depends on your data alignment and the goal of your analysis [42] [40].

Table: Comparison of Data Fusion Strategies

| Fusion Strategy | Description | Best Use Cases | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Early Fusion | Raw or pre-processed data from different modalities are combined into a single input vector before being fed into the model [42] [40]. | Modalities are perfectly aligned and have the same dimensionalities (e.g., multi-omics data from the same set of patient samples). | Allows the model to learn complex, low-level interactions between modalities directly from the data. | Requires precise data alignment; highly sensitive to noise and missing data in any single modality. |

| Intermediate Fusion | Features are extracted separately for each modality and then combined in an intermediate layer of the model (e.g., via concatenation or attention) [42] [40]. | The most common and flexible approach. Suitable when modalities have different representations but are related. | Balances modality-specific processing with joint representation learning; can capture complex cross-modal interactions. | Model architecture becomes more complex; requires careful tuning to balance learning across modalities. |

| Late Fusion | Each modality is processed by a separate model, and the final predictions (or decisions) are combined, for example, by averaging or voting [42] [40]. | Modalities are asynchronous, have different sampling rates, or are prone to missing data. | Highly flexible and robust to missing modalities; allows use of best model for each data type. | Cannot model cross-modal interactions at the feature level; may miss synergistic information. |

FAQ 2: Which deep learning architecture is best for integrating bulk multi-omics data for a classification task like cancer subtyping?

There is no single "best" architecture, as performance is highly task-dependent [41]. However, several architectures have proven effective:

- Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) with Encoders: A common approach involves using separate MLP encoders for each omics type to create a lower-dimensional representation, which is then fused and fed into a classifier [41]. This is a core component of toolkits like

Flexynesis. - Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): If your biological question can be framed as a network (e.g., a protein-protein interaction network), GNNs are powerful for capturing topological information and integrating node features from multiple omics [43].

- Transformers with Attention: Transformer models excel at weighing the importance of different features. They can be adapted for omics data to model long-range dependencies and identify key biomarkers across different data types [43] [40].

Recommendation: Start with a flexible toolkit like Flexynesis [41], which allows you to benchmark multiple deep learning architectures (and classical machine learning models) on your specific dataset to determine the best performer.

FAQ 3: How can I handle the computational complexity and resource demands of deep learning for large-scale multi-omics studies?

This is a common challenge given the high-dimensional nature of omics data.

- Utilize Cloud Computing: Platforms like Google Cloud, AWS, and Azure offer scalable computing resources, including GPUs, which are essential for training deep learning models efficiently.

- Dimensionality Reduction: Perform an initial feature selection step to reduce the dimensionality of your omics data before model training. This can be done using domain knowledge (e.g., selecting pathway genes) or algorithmic methods (e.g., variational autoencoders) [39].

- Transfer Learning: Consider using pre-trained models on large, public multi-omics datasets (like TCGA) and fine-tune them on your specific, smaller dataset. This can significantly reduce training time and data requirements.

- Optimized Toolkits: Use tools that are designed with efficiency in mind. For example,

Flexynesisstreamlines data processing, feature selection, and hyperparameter tuning, reducing unnecessary computational overhead [41].

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Implementing a Multi-Task Learning Experiment with Flexynesis

This protocol outlines how to use the Flexynesis toolkit to build a model that predicts multiple clinical outcomes simultaneously from multi-omics data [41].

- Input Data Preparation: Format your multi-omics data (e.g., gene expression, methylation) into matrices where rows are samples and columns are features. Prepare corresponding outcome variables (e.g., drug response as a continuous value, cancer subtype as a class label, and survival data).

- Toolkit Configuration: Install

Flexynesis(available via PyPi, Bioconda, or Galaxy Server). Choose a multi-task architecture where separate Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) for regression, classification, and survival are attached to the encoder network. - Model Training:

- The encoder network (e.g., a fully connected or graph-convolutional encoder) learns a joint latent representation from the input omics data.

- Each supervisor MLP uses this joint representation to learn its specific task (e.g., Cox Proportional Hazards loss for survival, cross-entropy for classification).

- The training process jointly optimizes the weights of the encoder and all supervisors, allowing the latent space to be informed by all tasks.

- Output and Analysis: The model outputs predictions for each task. Analyze the latent space embeddings to see if samples cluster by known biological groups and use the model's interpretability features to identify key cross-omics features driving the predictions.

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Fusion Strategies for Physiological Time Series Data

This protocol describes a methodology for comparing early, intermediate, and late fusion when integrating heterogeneous biomedical time series (e.g., EEG, ECG) with clinical records [40].

- Data Preprocessing & Alignment:

- Time Series: Filter noise, extract features (e.g., heart rate variability from ECG), or use raw signals. Segment data into uniform time windows.

- Clinical Data: Normalize numerical values and encode categorical variables.

- Temporal Alignment: Ensure all data streams are synchronized to a common timeline.

- Model Architecture Design:

- Early Fusion: Concatenate the raw/preprocessed time-series features and clinical data into a single input vector. Feed into a classifier (e.g., an MLP).

- Intermediate Fusion: Use a hybrid model (e.g., CNN-RNN) to extract features from the time series. At an intermediate layer, concatenate these features with the encoded clinical data, then pass through a final classifier.

- Late Fusion: Train a separate model (e.g., a 1D-CNN) on the time-series data and another model (e.g., an MLP) on the clinical data. Combine their final prediction probabilities via a meta-classifier (e.g., a logistic regressor) or weighted averaging.

- Evaluation: Evaluate all models on a held-out test set using metrics like Accuracy, F1-Score, and AUC-ROC. The best-performing strategy will depend on the specific interdependence of the modalities in your dataset.

Data Presentation

Quantitative Performance of Multi-Omics Integration Methods

Table: A summary of model performances on common tasks, as demonstrated in the reviewed literature. Performance is task-specific and these values are for illustrative comparison.

| Model/Tool | Data Types | Task | Reported Performance | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexynesis [41] | Gene Expression, Copy Number Variation | Drug Response (Lapatinib) Prediction | High correlation on external test set (GDSC2) | Flexible, multi-task; supports regression, classification, survival. |

| Flexynesis [41] | Gene Expression, Promoter Methylation | Microsatellite Instability (MSI) Classification | AUC = 0.981 | Demonstrates high accuracy without using mutation data. |

| Adaptive Multimodal Fusion Network (AMFN) [40] | Physiological Signals, EHRs | Biomedical Time Series Prediction | Outperformed state-of-the-art baselines | Uses attention-based alignment and graph-based learning. |

| DIABLO [39] | Multiple Omics | Supervised Classification & Biomarker Discovery | Effective for selecting co-varying modules | A supervised extension of sGCCA; good interpretability. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram: Multi-Omics Data Fusion Workflow

This diagram illustrates a generalized computational workflow for integrating multi-omics data using deep learning, from raw data to biological insight.

Diagram: Multimodal Fusion Strategies

This diagram provides a visual comparison of the three core data fusion strategies: Early, Intermediate, and Late Fusion.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Multi-Omics

Table: A list of key software tools, libraries, and data resources essential for conducting machine learning and deep learning-based data fusion research.

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in Data Fusion |

|---|---|---|---|