Navigating the Noise: A Comprehensive Guide to Handling Technical Variation in Single-Cell Data Analysis

Single-cell RNA sequencing has revolutionized biological research by enabling the exploration of cellular heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution.

Navigating the Noise: A Comprehensive Guide to Handling Technical Variation in Single-Cell Data Analysis

Abstract

Single-cell RNA sequencing has revolutionized biological research by enabling the exploration of cellular heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution. However, these technologies introduce substantial technical noise from multiple sources, including ambient RNA, barcode swapping, amplification biases, and dropout events, which can obscure biological signals and compromise downstream analyses. This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for understanding, mitigating, and validating noise reduction in single-cell data. Covering foundational concepts through advanced methodological applications, we examine current computational strategies from statistical models and deep learning approaches to emerging best practices for troubleshooting and benchmarking. By synthesizing the latest advancements in noise handling, this guide aims to empower more accurate cell type identification, differential expression analysis, and biological discovery across diverse single-cell modalities.

Understanding the Landscape of Single-Cell Noise: Sources, Impacts, and Fundamental Concepts

In droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), technical noise can compromise data integrity and lead to misleading biological conclusions. Two major sources of this noise are ambient RNA and barcode swapping. Ambient RNA consists of cell-free mRNA molecules released into the cell suspension from ruptured, dead, or dying cells, which can be co-encapsulated with intact cells during the droplet formation process [1] [2] [3]. Barcode swapping, conversely, is a phenomenon occurring during library preparation on patterned Illumina flow cells, where barcode sequences are misassigned between samples, leading to reads from one sample being incorrectly attributed to another [4]. Understanding the differences between these technical artifacts is crucial for selecting appropriate decontamination strategies and ensuring the reliability of your single-cell data.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between ambient RNA and barcode swapping?

Ambient RNA is a biological contamination that occurs during the wet-lab stage of single-cell experiments. It involves genuine mRNA molecules that are present in the cell suspension and get packaged into droplets alongside intact cells [2] [3]. In contrast, barcode swapping is a technical error that happens later, during the sequencing library preparation. It results from the misassignment of index reads on patterned flow-cell Illumina sequencers (e.g., HiSeq 4000, HiSeq X, NovaSeq), causing a read from one sample to be labelled with the barcode of another sample [4].

2. How can I tell if my dataset is affected by ambient RNA?

Several indicators can signal significant ambient RNA contamination:

- Web Summary Alert: Your Cell Ranger Web Summary may flag a "Low Fraction Reads in Cells" [2].

- Barcode Rank Plot: The plot may lack a clear, steep inflection point (a "knee") that distinguishes cell-containing barcodes from empty droplets [2].

- Marker Gene Mis-expression: You may observe known cell type-specific marker genes (e.g., hemoglobin genes in non-erythroid cells) appearing in unexpected cell types [5] [3].

- Mitochondrial Gene Enrichment: A cluster of cells showing significant enrichment for mitochondrial genes can indicate the presence of dead or dying cells contributing to the ambient pool [2].

3. What are the best computational tools to correct for ambient RNA?

Several community-developed tools are available, each with different approaches. The performance of these tools can vary, with studies showing differences in their precision and the improvements they yield for marker gene detection [1].

Table: Comparison of Ambient RNA Removal Tools

| Tool Name | Primary Method | Key Function | Language | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CellBender [1] [2] | Deep generative model, neural network | Cell calling & ambient RNA removal | Python | High computational cost, but precise noise estimation [1]. |

| SoupX [1] [2] | Estimates contamination fraction using empty droplets | Ambient RNA removal | R | Allows both auto-estimation and manual setting of contamination fraction. |

| DecontX [1] [3] | Bayesian mixture model | Ambient RNA removal | R | Models counts as a mixture of native and contaminating distributions. |

| EmptyNN [2] | Neural network classifier | Cell calling (removes empty droplets) | R | Performance may vary by tissue type. |

| DropletQC [2] | Nuclear fraction score | Identifies empty droplets, damaged, and intact cells | R | Does not remove ambient RNA from true cells. |

4. How prevalent is barcode swapping, and how can I prevent it?

Estimates from plate-based scRNA-seq experiments found approximately 2.5% of reads were mislabelled due to barcode swapping on a HiSeq 4000, an order of magnitude higher than on a HiSeq 2500 [4]. To mitigate barcode swapping:

- Sequencing Platform: Use non-patterned flow cell sequencers (e.g., HiSeq 2500) where possible [4].

- Experimental Design: Use unique dual indexing, where two unique barcodes are used for each sample, which prevents mixing even if one barcode swaps [4].

- Computational Correction: For 10x Genomics data, specific algorithms can be used to exclude individual molecules suspected of barcode swapping [4].

5. What is the quantitative impact of background noise on my data?

The level of background noise is highly variable. In a controlled study using mouse kidney scRNA-seq data, background noise made up an average of 3% to 35% of the total UMIs per cell across different replicates [1]. This noise level is directly proportional to the specificity and detectability of marker genes, meaning higher noise can obscure true biological signals [1].

Table: Key Characteristics of Ambient RNA and Barcode Swapping

| Characteristic | Ambient RNA | Barcode Swapping |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Biological (cell suspension) [3] | Technical (library prep/sequencing) [4] |

| Phase of Occurrence | Wet-lab (droplet encapsulation) | Dry-lab (library sequencing) |

| Primary Effect | Adds background counts from a pooled ambient profile [1] | Mislabels reads between specific samples or cells [4] |

| Typical Scope | Affects all cells in a sample to varying degrees [1] | Can create complex, artefactual cell libraries [4] |

| Effective Removal Tools | CellBender, SoupX, DecontX [1] [2] | Custom algorithms for swapping removal; unique dual indexing [4] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving High Ambient RNA

Symptoms:

- Unexplained expression of highly specific marker genes in inappropriate cell types (e.g., hemoglobin in neural cells) [5].

- Poor separation between cell clusters in UMAP/t-SNE plots.

- A low fraction of reads in cells reported in the Cell Ranger web summary [2].

Actionable Steps:

- Confirm the Source: Use

SoupXorCellBenderto estimate the ambient RNA profile from empty droplets and check if the genes causing confusion are prominent in this profile [2]. - Apply Computational Correction: Run an ambient removal tool like

CellBender,SoupX, orDecontXon your raw count matrix. Re-visualize the data to see if the spurious marker gene expression is reduced and if cluster separation improves [1] [3]. - Optimize Future Preparations: For subsequent experiments, focus on wet-lab optimizations to minimize cell death and rupture. This includes optimizing tissue dissociation protocols, considering cell fixation, using nuclei preparation (with caution, as it can also release RNA), and ensuring proper cell loading concentrations on microfluidic devices [6].

Guide 2: Addressing Suspected Barcode Swapping

Symptoms:

- Presence of "impossible" cells that co-express mutually exclusive markers from different samples in a multiplexed run [4].

- Lower-than-expected doublet rates from standard detectors, but persistent evidence of mixed identities.

Actionable Steps:

- Inspect Barcode Design: If using a plate-based method, check if "impossible" barcode combinations (those not used in the experiment) contain mappable reads, which is a tell-tale sign of swapping [4].

- Quantify the Swapping Rate: Use statistical approaches to estimate the fraction of swapped reads. This can be done by regressing the library sizes of impossible barcode combinations against the libraries that share one barcode with them [4].

- Apply Corrective Algorithms: For droplet-based data, use methods specifically designed to identify and exclude molecules that have undergone barcode swapping [4].

- Plan Your Next Experiment: Implement unique dual indexing to definitively prevent barcode swapping, or schedule your sequencing on platforms without patterned flow cells [4].

Experimental Protocols for Noise Evaluation

Protocol 1: Using a Mouse-Human Mixture to Quantify Ambient RNA

This protocol provides a ground truth for assessing ambient RNA levels by leveraging species-specific reads.

Methodology:

- Cell Mixture: Prepare a pooled sample containing cells from both human (e.g., HEK293T) and mouse (e.g., NIH3T3) cell lines [3].

- Sequencing and Alignment: Process the pool through your standard droplet-based scRNA-seq workflow (e.g., 10x Genomics). Align the sequencing reads to a combined human and mouse reference genome (e.g., hg19 + mm10). Tools like Cell Ranger can perform this step and assign reads uniquely to one genome [3].

- Cell Classification: Classify each cell barcode as human, mouse, or a multiplet based on the majority of its aligned reads [3].

- Contamination Calculation: For each cell classified as human, calculate the percentage of its UMIs that map to the mouse genome, and vice-versa. This percentage provides a direct lower-bound estimate of cross-contamination for each cell [3].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Ambient RNA Removal Tools with Genetically Distinct Pools

This advanced protocol uses SNPs from different mouse strains to profile background noise more accurately in a complex tissue context.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Generate a complex cell mixture by pooling cells or nuclei from genetically distinct mouse strains (e.g., M. m. domesticus and M. m. castaneus) [1].

- SNP-based Genotyping: Sequence the pooled sample. Leverage known homozygous SNPs to assign each cell to its strain of origin [1].

- Noise Estimation: In a cell assigned to one strain, identify UMIs that cover informative SNPs and count how many originate from the foreign genotype. This allows for a maximum likelihood estimate of the background noise fraction (( \rho_{cell} )) that includes contamination from the same species [1].

- Tool Benchmarking: Use this genotype-based noise estimate as a ground truth to benchmark the performance of ambient removal tools like

CellBender,DecontX, andSoupXin terms of their precision in estimating and removing the contamination [1].

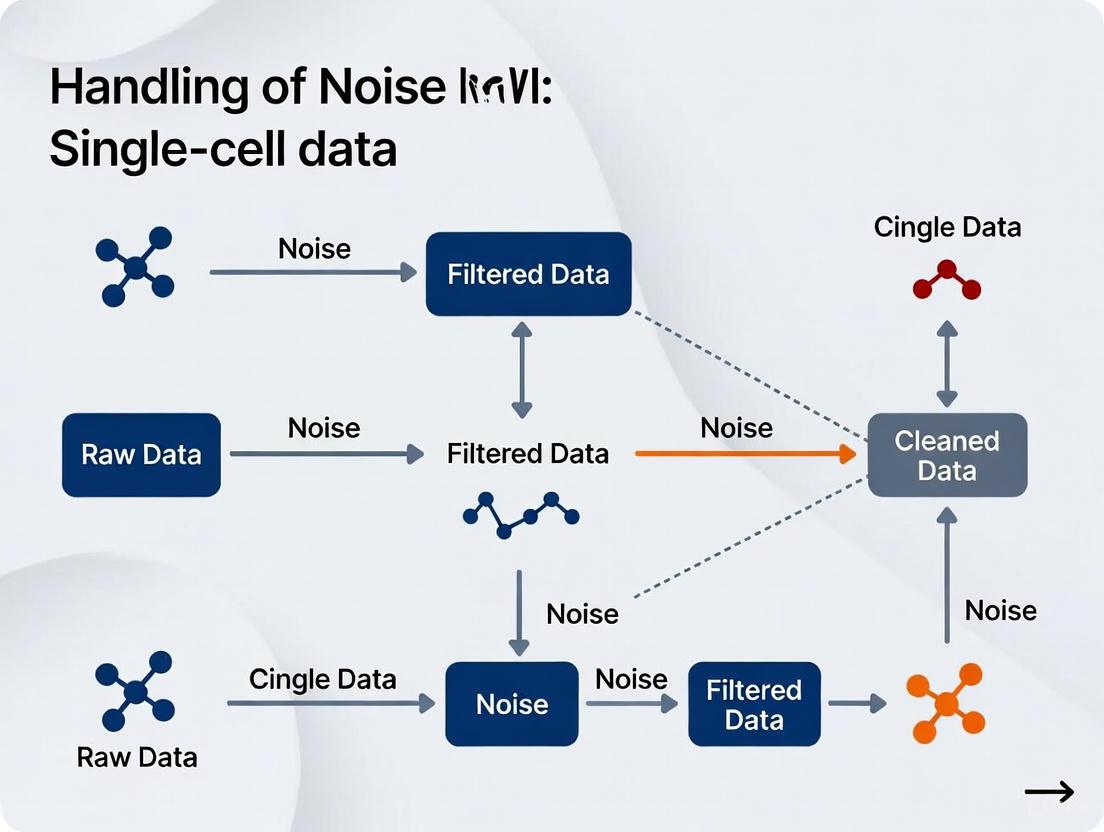

Visual Workflows

Single-Cell RNA-seq Noise Identification and Decontamination Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Essential Materials for Investigating Technical Noise

| Item | Function in Noise Investigation | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Genetically Distinct Cell Lines | Provides a ground truth for quantifying contamination. | Mixing human (HEK293T) and mouse (NIH3T3) cells to track species-specific reads [3]. |

| Inbred Mouse Strains | Allows for SNP-based tracking of contamination within the same species. | Using M. m. domesticus (BL6) and M. m. castaneus (CAST) to profile noise in complex tissues [1]. |

| Droplet-Based scRNA-seq Kit | The platform for generating single-cell data where noise is assessed. | 10x Genomics Chromium kit for single-cell partitioning and barcoding [1] [3]. |

| Cell Viability Assay | To assess the health of the cell suspension pre-encapsulation. | High viability reduces the source of ambient RNA [6]. |

| Computational Tools | Software to quantify and remove technical noise. | CellBender for ambient RNA; custom scripts for barcode swapping quantification [1] [4]. |

FAQs: Understanding Background Noise in Single-Cell Data

Background noise in droplet-based single-cell and single-nucleus RNA-seq experiments primarily originates from two sources:

- Ambient RNA: This is cell-free RNA that leaks from broken cells into the cell suspension. It is subsequently captured in droplets and sequenced along with the RNA from an intact cell [1] [7].

- Barcode Swapping: During library preparation, chimeric cDNA molecules can form. This occurs when a molecule is tagged with a barcode from a different cell, often due to incomplete removal of oligonucleotides or template jumping, causing the read to be misassigned [1].

The majority of background molecules have been shown to originate from ambient RNA [1] [7].

How significantly does background noise impact data analysis?

Background noise can have a substantial and variable impact, affecting different analyses in distinct ways [1]:

- Marker Gene Detection: This is highly susceptible to background noise. Noise levels are directly proportional to the specificity and detectability of marker genes. Spillover of marker genes into other cell types can create false-positive signals and obscure true biological signals [1] [8].

- Cell Clustering: Clustering and cell classification are fairly robust towards background noise. Only small improvements can be achieved by background removal, and aggressive correction may sometimes distort fine population structures [1].

- Noise Variability: The fraction of UMIs attributed to background noise is highly variable, ranging on average from 3% to 35% per cell across different experiments and replicates [1].

Which computational methods are effective for reducing background noise?

Several methods have been developed to quantify and remove background noise. A benchmark study using genotype-based ground truth found varying performance [1]:

| Method | Key Approach | Performance Note |

|---|---|---|

| CellBender | Uses a deep generative model and empty droplet profiles to remove ambient RNA and account for barcode swapping [1]. | Provides the most precise noise estimates and highest improvement for marker gene detection [1]. |

| SoupX | Estimates contamination fraction per cell using marker genes and employs empty droplets to define the background profile [1]. | A commonly used method for ambient RNA correction. |

| DecontX | Models the background noise fraction by fitting a mixture distribution based on cell clusters [1]. | Provides an alternative clustering-based approach. |

| RECODE | A high-dimensional statistics-based tool upgraded to reduce both technical and batch noise across various single-cell modalities [9]. | Offers a versatile solution for transcriptomic, epigenomic, and spatial data. |

| noisyR | A comprehensive noise filter that assesses signal distribution variation to achieve information-consistency across replicates [10]. | Applicable to both bulk and single-cell sequencing data. |

Does the sequencing platform influence background noise?

Yes, the sequencing platform can affect the nature and level of background contamination. A systematic comparison of 10x Chromium and BD Rhapsody platforms found that the source of ambient noise was different between plate-based and droplet-based platforms. This highlights the importance of considering platform choice and its specific noise profile during experimental design [11].

Experimental Protocols for Quantifying Noise Impact

Genotype-Based Profiling of Background Noise

This protocol uses cells from different genetic backgrounds pooled in one experiment, allowing for precise tracking of contaminating molecules [1].

1. Experimental Design and Cell Preparation

- Sample Pooling: Pool cells from genetically distinct but closely related sources. The featured experiment used kidneys from three mouse strains: one M. m. castaneus (CAST/EiJ) and two M. m. domesticus (C57BL/6J and 129S1/SvImJ) [1].

- Single-Cell Sequencing: Process the pooled sample using a standard droplet-based protocol (e.g., 10x Chromium) to generate scRNA-seq or snRNA-seq data [1].

2. Data Processing and Genotype Calling

- SNP Identification: Identify known homozygous Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs) that distinguish the subspecies and strains. The referenced study used over 40,000 informative SNPs [1].

- Cell Assignment: For each cell, use the coverage of these SNPs to assign it to a specific mouse and, consequently, a genotype [1].

3. Quantification of Background Noise

- Cross-Genotype Contamination: In a cell assigned to M. m. castaneus, any UMI that contains a M. m. domesticus allele is identified as a contaminating molecule [1].

- Noise Fraction Calculation: Calculate the fraction of foreign UMIs covering informative SNPs for each cell. This observed cross-genotype contamination is a lower bound for the total noise. A maximum likelihood estimate ((\rho_{cell})) can then be derived to extrapolate and estimate the total background noise fraction, including contamination from the same genotype [1].

The workflow for this experimental approach is outlined below.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Context |

|---|---|

| Cells from Distinct Genotypes | Provides the ground truth for quantifying background noise through identifiable genetic variants (e.g., mouse subspecies CAST and BL6) [1]. |

| Spike-in ERCC RNA | Exogenous RNA controls used to model technical noise and calibrate measurements, enabling methods like the Gamma Regression Model (GRM) for explicit noise removal [12]. |

| Informative SNPs | Known genetic variants used as natural barcodes to track the origin of each transcript and distinguish true signal from contamination [1]. |

| Fixed and Permeabilized Cells | Treated cells (e.g., with PFA or glyoxal) are essential for protocols like SDR-seq that require in-situ reverse transcription while preserving gDNA and RNA targets [13]. |

| Multiplexed PCR Primers | Used in targeted single-cell assays (e.g., SDR-seq) to simultaneously amplify hundreds of genomic DNA and cDNA targets within individual cells [13]. |

Quantitative Impact of Noise and Correction

Noise Levels and Method Performance

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from the benchmark study on background noise [1].

Table 1: Measured Noise Levels and Correction Performance

| Metric | Finding | Notes / Range |

|---|---|---|

| Average Background Noise | 3-35% of total UMIs per cell | Highly variable across replicates and individual cells [1]. |

| Impact on Marker Detection | Directly proportional to noise level | Higher noise reduces specificity and detectability [1]. |

| Top-Performing Tool | CellBender | Provided most precise noise estimates and best improvement for marker gene detection [1]. |

The logical relationships between noise sources, their impacts on data, and the subsequent correction outcomes are summarized in the following workflow.

Understanding Zeros in Your Data

What are the fundamental types of zeros in scRNA-seq data?

In scRNA-seq data, zeros are categorized into two fundamental types based on their origin. Understanding this distinction is crucial for appropriate data interpretation.

Biological Zeros: These represent a true biological signal, meaning a gene's transcripts are genuinely absent or present at undetectably low levels in a cell. This can occur because the gene is not expressed in that particular cell type, or due to the stochastic, "bursty" nature of transcription, where a gene temporarily switches to an inactive state [14] [15] [16].

Non-Biological Zeros: These are technical artifacts that mask true gene expression. They are further subdivided into:

- Technical Zeros: Occur during initial library-preparation steps, such as inefficient reverse transcription, where mRNA fails to be converted into cDNA [14] [15].

- Sampling Zeros: Arise from later steps, including inefficient cDNA amplification (e.g., due to PCR biases) or due to limited sequencing depth, which causes low-abundance transcripts to be missed entirely [14] [15] [17].

Table 1: Classification of Zero Counts in scRNA-seq Data

| Category | Sub-type | Definition | Primary Cause |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biological Zero | - | True absence of a gene's mRNA in a cell. | Gene is not expressed or is in a transcriptional "off" state [14] [15]. |

| Non-Biological Zero | Technical Zero | Gene is expressed, but its mRNA is not converted to cDNA. | Inefficient reverse transcription or library preparation [14] [15]. |

| Sampling Zero | Gene is expressed and converted to cDNA, but not sequenced. | Limited sequencing depth or inefficient cDNA amplification (e.g., PCR bias) [14] [15] [17]. |

How do I know if a zero is biological or technical?

Distinguishing between biological and technical zeros is a major challenge, as they are indistinguishable in the final count matrix without additional information [14] [15]. However, you can use the following strategies to infer their nature:

- Leverage Biological Replicates: If a gene has zero counts in one cell but is consistently expressed in other cells of the same type, the zero is more likely to be technical.

- Analyze Expression Patterns: Genes that show a strong "on/off" pattern (i.e., expressed in a subset of cells and zero in others) across a presumed homogeneous population might be governed by biological bursting, but this pattern can be conflated with technical dropouts.

- Use Spike-In Controls: Adding known quantities of exogenous RNA transcripts during the experiment can help model the technical noise and dropout rate, allowing for better estimation of which zeros are technical [14].

- Employ Statistical Models: Some computational methods are designed to model the technical noise and can probabilistically assign zeros to different categories.

Diagram: A decision workflow for conceptually classifying the source of an observed zero in scRNA-seq data.

Troubleshooting Quality Control

What are the key QC metrics for identifying low-quality cells?

Rigorous quality control (QC) is the first line of defense against technical artifacts. The standard QC metrics computed from the count matrix help identify and filter out low-quality cells [18] [19].

- Count Depth (

nCount_RNA): The total number of UMIs or reads detected per cell (barcode). An unusually low count depth often indicates a poor-quality cell, empty droplet, or a dying cell from which RNA has leaked out [18] [19]. - Genes Detected (

nFeature_RNA): The number of genes with at least one count detected per cell. Low values can indicate poor-quality cells, while very high values might suggest doublets (multiple cells labeled with the same barcode) [19]. - Mitochondrial Count Fraction (

percent.mt): The percentage of counts that map to mitochondrial genes. A high fraction (e.g., >10-20%) is a hallmark of cell stress or apoptosis, as dying cells release cytoplasmic RNA while mitochondrial RNA remains trapped [18] [19].

Table 2: Standard QC Metrics for scRNA-seq Data Filtering

| QC Metric | What It Measures | Typical Threshold(s) | Indication of Low Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count Depth | Total molecules detected per cell. | Minimum ~500-1000 UMIs [19]. | Too low: Empty droplet or dead cell. |

| Genes Detected | Complexity of the transcriptome per cell. | Minimum ~250-500 genes [19]. | Too low: Poor-quality cell. Too high: Potential doublet. |

| Mitochondrial Fraction | Cell viability/stress. | Often 10-20% [18] [19]. | High percentage: Apoptotic or stressed cell. |

How do I set rational thresholds for filtering cells?

Setting thresholds is a critical step that balances the removal of technical noise with the preservation of biological heterogeneity. The following methodologies are recommended:

- Manual Thresholding with Visualization: Plot the distributions of QC metrics (e.g., violin plots, scatter plots) to visually identify outliers. For example, in a scatter plot of genes detected versus mitochondrial fraction, low-quality cells often cluster separately from the main cloud of cells [18].

- Automatic Thresholding with MAD: For large datasets, use robust statistics. A common method is the Median Absolute Deviation (MAD). Cells that deviate by more than a certain number of MADs (e.g., 5 MADs) from the median of a given metric are flagged as outliers. This is a more permissive strategy that helps avoid filtering rare cell types [18].

- Biology-Guided Adjustment: Always adjust thresholds based on biological expectations. For example, certain cell types (like neutrophils) naturally have low RNA content, and stressed cells in an experiment might require a higher mitochondrial threshold to avoid losing a entire biological condition [19].

Resolving Data Analysis Issues

Should I impute zeros in my dataset?

The decision to impute (replace zeros with estimated values) is analysis-dependent and remains a topic of debate [14] [16]. The table below summarizes the main approaches.

Table 3: Approaches for Handling Zeros in Downstream Analysis

| Approach | Description | Best Used For | Key Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use Observed Counts | Analyzing the data without modifying zeros. | Identifying cell types from highly expressed marker genes. Differential expression testing with models designed for count data (e.g., negative binomial) [14] [17]. | May underestimate correlations and miss subtle biological signals [14]. |

| Imputation | Filling in zeros with estimated non-zero values using statistical or machine learning models. | Recovering weak but coherent biological signals, such as gradient-like expression in trajectory inference [14]. | Oversmoothing: Can introduce spurious correlations and create false-positive gene-gene associations [20]. |

| Binarization | Converting counts to a 0/1 matrix (expressed/not expressed). | Focusing on the presence or absence of genes, such as in certain pathway analysis methods [14]. | Loses all information about expression level, which can be critical. |

- Recommendation: If you choose to impute, use methods that are transparent and have been benchmarked for your specific analytical task. Be cautious, as a benchmark study found that several popular imputation methods introduced substantial spurious gene-gene correlations, potentially leading to misleading biological conclusions [20].

How can I correct for batch effects without losing information?

Batch effects are technical variations between datasets processed at different times or under different conditions. Correcting them is essential for combined analysis.

- The Challenge: Traditional batch correction methods often rely on dimensionality reduction (e.g., PCA), which can be insufficient for high-dimensional single-cell data and may discard biologically relevant information [21].

- Advanced Solution: Newer tools are being developed to address this. For instance, iRECODE is an upgraded algorithm that integrates batch correction within a high-dimensional statistical framework, aiming to simultaneously reduce both technical noise and batch effects while preserving the full dimensionality of the data [21].

- Standard Practice: Tools like Harmony, Seurat, SCTransform, FastMNN, and scVI are widely used for data integration and batch correction [21] [22]. The choice depends on your dataset's size and complexity.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools & Reagents for scRNA-seq Analysis

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Reference / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Ranger | Software Pipeline | Processes FASTQ files from 10x Genomics assays into count matrices. | 10x Genomics [23] |

| Seurat / Scanpy | R/Python Package | Comprehensive toolkit for downstream QC, normalization, clustering, and visualization. | [22] [19] |

| popsicleR | R Package | Interactive wrapper package for guided pre-processing and QC of scRNA-seq data. | [23] |

| SoupX / CellBender | R/Python Tool | Removes ambient RNA contamination from droplet-based data. | [22] |

| Scrublet | Python Tool | Identifies and removes doublets from the data. | [22] |

| RECODE / iRECODE | Algorithm | Reduces technical noise (dropouts) and batch effects using high-dimensional statistics. | [21] |

| Harmony | Algorithm | Integrates data across multiple batches for combined analysis. | [21] |

| Unique Molecular Identifier (UMI) | Molecular Barcode | Attached to each mRNA molecule during library prep to correct for amplification bias and quantify absolute transcript counts. | [14] [22] |

| Spike-In RNA | External Control | Added to the sample in known quantities to calibrate technical noise and absolute expression. | [14] |

Diagram: A standard scRNA-seq data preprocessing workflow, from raw sequencing data to a matrix ready for analysis.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This technical support resource addresses common experimental and computational challenges in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq), framed within the broader thesis of handling noise in single-cell data research.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our scRNA-seq analysis shows unexpected cell-to-cell variability. How can we determine if it's biological noise or a technical artifact?

Biological noise, stemming from intrinsic stochastic fluctuations in transcription, is a genuine characteristic of isogenic cell populations [24]. However, technical artifacts from scRNA-seq protocols can also contribute to measured variability. To diagnose the source:

- Compare with smFISH: Use single-molecule RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (smFISH) as a gold standard to validate findings for a panel of representative genes. Studies show scRNA-seq algorithms can systematically underestimate true biological noise levels compared to smFISH [24].

- Utilize Noise Enhancers: Employ small-molecule perturbations like 5′-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine (IdU), which are known to orthogonally amplify transcriptional noise without altering mean expression levels. If your data shows increased variability after IdU treatment, it likely reflects a true biological signal [24].

- Check QC Metrics: High percentages of mitochondrial reads or low unique molecular identifier (UMI) counts can indicate poor cell viability or ambient RNA contamination, which are technical sources of noise [25] [26].

Q2: What is the best experimental design to correct for batch effects in scRNA-seq when all cell types are not present in every batch?

Completely randomized designs, where every batch contains all cell types, are ideal but often impractical [27]. Two flexible and valid designs are:

- Reference Panel Design: One or a few "reference" batches contain all cell types, while other batches contain subsets.

- Chain-Type Design: Each batch shares at least one cell type with at least one other batch, creating a connected chain across all batches [27]. Methods like Batch effects correction with Unknown Subtypes for scRNA-seq (BUSseq) are mathematically proven to correct batch effects under these designs, even when cell types are missing from some batches [27].

Q3: How can we mitigate the high number of dropout events (false zeros) in our scRNA-seq data, especially for lowly expressed genes?

Dropout events, where a transcript is not detected even when expressed, are a major source of technical noise [25] [27].

- Computational Imputation: Use algorithms that model the dropout process, such as ZINB-WaVE, scVI, or BUSseq, to impute missing values [27].

- Experimental Considerations: Ensure high cell viability during sample preparation to reduce RNA degradation [28]. Use protocols with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to correct for amplification bias [25].

- Leverage Data Structure: Some imputation methods use patterns in the data (e.g., genes expressed in similar cells) to predict missing values [27].

Q4: What are the critical quality control (QC) steps after generating scRNA-seq data?

Rigorous QC is essential for reliable data interpretation [26].

- Assess Cell Viability: A viability of 70-90% with intact cell morphology is ideal [28].

- Filter Low-Quality Barcodes: Remove barcodes with unusually high or low UMI counts or numbers of features, which may represent multiplets or ambient RNA [26].

- Check Mitochondrial Read Percentage: High percentages (e.g., >10% in PBMCs) can indicate broken cells. However, this threshold is cell-type-dependent [26].

- Review Sequencing Metrics: Use summary files (e.g.,

web_summary.htmlfrom Cell Ranger) to check for expected numbers of recovered cells, median genes per cell, and mapping rates [26].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Issue: Low RNA Input and Coverage

- Causes: Incomplete reverse transcription, inefficient amplification, or poor cell viability [25].

- Solutions:

Issue: Amplification Bias

- Causes: Stochastic variation during PCR amplification, leading to skewed gene representation [25].

- Solutions:

Issue: Cell Aggregation and Debris in Suspension

- Causes: Dead cells, tissue debris, or cations (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺) in the media [28].

- Solutions:

- Filter the suspension through a flow cytometry strainer or similar membrane [28].

- Use calcium/magnesium-free media (e.g., HEPES-buffered salt solution) during preparation [28].

- Optimize centrifugation speed and duration to avoid over-pelleting [28].

- Perform density gradient centrifugation (e.g., with Ficoll) to separate viable cells from debris [28].

Quantitative Data on scRNA-seq Noise

The table below summarizes key findings from a study comparing noise quantification between scRNA-seq algorithms and smFISH [24].

Table 1: Quantification of Transcriptional Noise Using IdU Perturbation

| Metric | Finding | Implication for scRNA-seq Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Genes with Amplified Noise (CV²) | ~73-88% of expressed genes showed increased noise after IdU treatment across five scRNA-seq algorithms [24]. | IdU acts as a globally penetrant noise enhancer, useful for probing noise physiology. |

| Mean Expression Change | Largely unchanged by IdU treatment across all algorithms [24]. | Confirms IdU's orthogonal action, amplifying noise without altering mean expression. |

| Noise Fold Change (vs. smFISH) | scRNA-seq algorithms systematically underestimate the fold change in noise amplification compared to smFISH [24]. | scRNA-seq is suitable for detecting noise changes, but the magnitude may be underestimated. |

| Algorithms Tested | SCTransform, scran, Linnorm, BASiCS, SCnorm, and a simple "raw" normalization [24]. | All tested algorithms are appropriate for noise quantification, though results vary. |

Methodologies for Key Experiments

Protocol: Validating scRNA-seq Noise Quantification with smFISH This protocol is used to benchmark the accuracy of scRNA-seq algorithms in quantifying transcriptional noise [24].

- Cell Culture and Perturbation: Treat isogenic cells (e.g., mouse embryonic stem cells or human Jurkat T lymphocytes) with a noise-enhancer molecule like IdU and a DMSO control.

- scRNA-seq Library Preparation: Prepare single-cell libraries for both treated and control cells using a deeply sequenced platform (>60% sequencing saturation is recommended).

- Computational Analysis: Analyze the data using multiple scRNA-seq normalization algorithms (e.g., SCTransform, BASiCS) to calculate noise metrics like the coefficient of variation (CV) or Fano factor.

- smFISH Validation: For a panel of representative genes spanning different expression levels and functions, perform smFISH on both IdU-treated and control cells.

- Comparison: Compare the fold change in noise (IdU/DMSO) measured by each scRNA-seq algorithm to the fold change measured by smFISH. Expect scRNA-seq to underestimate the true noise change validated by smFISH [24].

Workflow: An Integrated scRNA-seq Analysis Pipeline with Batch Effect Correction The following diagram outlines a robust workflow for analyzing scRNA-seq data, incorporating steps to handle technical noise and batch effects.

scRNA-seq Analysis and Noise Correction Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for scRNA-seq Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| 5′-Iodo-2′-deoxyuridine (IdU) | A small-molecule "noise enhancer" that orthogonally amplifies transcriptional noise without altering mean expression levels [24]. | Used to perturb and study the physiological impacts of genome-wide transcriptional noise [24]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short nucleotide sequences that tag individual mRNA molecules to correct for amplification bias and quantitatively count transcripts [25]. | Standard in many scRNA-seq protocols (e.g., 10x Genomics) for accurate gene expression quantification [26]. |

| Spike-in Controls (e.g., ERCC) | Exogenous RNA controls of known concentration added to the lysate to monitor technical variation and assist normalization [25]. | Used to distinguish technical noise from biological variability, particularly in specialized algorithms like BASiCS [24]. |

| Enzyme Cocktails (e.g., gentleMACS) | Mixtures of enzymes for the gentle and reproducible dissociation of solid tissues into high-quality single-cell suspensions [28]. | Essential for preparing viable single-cell suspensions from challenging tissues like brain or tumor samples [28]. |

| Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) | A calcium/magnesium-free buffer used during cell suspension preparation to prevent cell clumping and aggregation [28]. | Used to wash and resuspend cells after dissociation to minimize aggregation before loading on a scRNA-seq platform [28]. |

| Fixation Reagents (e.g., Paraformaldehyde) | Chemicals that preserve cells or nuclei at a specific moment, allowing for storage and batch processing [28]. | Enables complex experimental designs (e.g., time courses) by fixing samples for later simultaneous processing, reducing batch effects [28]. |

FAQs: Understanding Noise in Single-Cell Data

Technical noise in scRNA-seq arises from multiple steps in the experimental workflow. The primary sources include: (1) stochastic dropout events, where transcripts are lost during cell lysis, reverse transcription, and amplification; (2) amplification bias, especially for lowly expressed genes; (3) varying sequencing depths between cells; and (4) differences in capture efficiency between cells and batches. Biological noise, stemming from intrinsic stochastic fluctuations in transcription, is an important source of genuine cell-to-cell variability but can be obscured by these technical artifacts [29] [30].

How can I distinguish technical noise from genuine biological variability?

The most robust method involves using external RNA spike-in molecules. These are added in identical quantities to each cell's lysate, providing an internal standard that allows for modeling of the technical noise expected across the dynamic range of gene expression. Statistical models, such as the one described by Grün et al., can then decompose the total variance of each gene's expression across cells into biological and technical components by leveraging the spike-in data [29]. Without spike-ins, this distinction becomes significantly more challenging.

Do different scRNA-seq protocols generate different levels of noise?

Yes, the choice of protocol significantly impacts the technical noise profile. Methods are broadly categorized as full-length transcript protocols (e.g., SMART-Seq2) or 3'/5' end-counting protocols (e.g., Drop-seq, 10x Genomics). Full-length protocols excel in detecting more expressed genes and are better for isoform analysis, while droplet-based methods offer higher throughput at a lower cost per cell. Crucially, protocols that incorporate Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs), such as MARS-Seq and 10x Genomics, are highly effective at mitigating PCR amplification bias, thereby providing more quantitative data [30].

Why is biological replication more important than sequencing depth for noise assessment?

High-throughput technologies can create the illusion of a large dataset due to deep sequencing, but statistical power primarily comes from the number of independent biological replicates, not the depth of sequencing per replicate. A sample size of one plant or mouse per condition is essentially useless for population-level inference, regardless of sequencing depth, because there is no way to determine if that single observation is representative. While deeper sequencing can modestly increase power to detect differential expression, these gains plateau after a moderate depth is achieved. True replication allows researchers to estimate the within-group variance of a population, which is central to distinguishing signal from noise [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: High Technical Noise and Batch Effects Obscuring Biological Signals

Issue: Cells cluster by batch or experimental run instead of by biological condition. High dropout rates mask the detection of rare cell types and subtle biological variations.

Solutions:

- Proactive Experimental Design: Implement blocking and pooling strategies during the experimental design phase to minimize the influence of unwanted noise [31].

- Utilize Sample Multiplexing: Use technologies like CellPlex, which allows tagging of up to 12 different samples with lipid-based barcodes (CMOs) before pooling them for a single sequencing run. This inherently controls for batch effects from library preparation and sequencing [32].

- Algorithmic Noise Reduction: Apply computational tools designed for comprehensive noise reduction. For instance, the RECODE platform uses high-dimensional statistics to reduce technical noise, and its upgraded version, iRECODE, integrates batch correction directly into its workflow. This simultaneous reduction of technical and batch noise preserves the full-dimensional data, enabling more accurate downstream analysis [21].

- Include External Spike-Ins: Always add RNA spike-in controls to your experiments. They are non-negotiable for accurately modeling and quantifying the technical component of noise [29].

Validation Workflow:

Problem: scRNA-seq Algorithms Underestimate True Transcriptional Noise

Issue: Comparisons with single-molecule RNA FISH (smFISH), the gold standard for mRNA quantification, reveal that various scRNA-seq normalization algorithms systematically underestimate the fold change in noise amplification, even if they correctly identify its direction [24].

Solutions:

- Validate with smFISH: For a critical panel of genes, use smFISH imaging to obtain a gold-standard measurement of noise. This is especially important when investigating noise changes following a perturbation.

- Benchmark Algorithms: Test multiple scRNA-seq normalization algorithms (e.g., SCTransform, scran, BASiCS) on your data. Be aware that while they may confirm a global noise trend, the magnitude of change will likely be more accurately reflected in the smFISH data.

- Use Noise-Enhancer Controls: In perturbation studies, consider using small molecules like IdU (5′-iodo-2′-deoxyuridine) that are known to orthogonally amplify transcriptional noise without altering mean expression levels. This provides a positive control for your noise measurement pipeline [24].

Problem: Low-Quality Sample Suspension Leading to High Background Noise

Issue: A poor-quality single-cell suspension containing dead cells, debris, or aggregates leads to high background RNA, compromising data quality and increasing technical noise.

Solutions:

- Ensure Sample Quality: A good sample is clean (free of debris and aggregates), healthy (>90% viability), and intact (with intact cellular membranes) [33].

- Use Appropriate Buffers: Wash and resuspend your cell suspension in EDTA-, Mg²⁺- and Ca²⁺-free 1X PBS to prevent interference with reverse transcription. If using FACS, sort cells into a compatible, chemically simple buffer or directly into lysis buffer containing an RNase inhibitor [34].

- Employ Debris Removal: Use dead cell removal kits, density centrifugation, or fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) to enrich for live, intact cells before loading them onto the Chromium chip [33].

Quantitative Data on Noise and Performance

Table 1: Performance of scRNA-seq Normalization Algorithms in Quantifying Noise

| Algorithm | Underlying Model | Noise Metric Reported | Accuracy vs. smFISH | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BASiCS [24] | Hierarchical Bayesian | CV², Fano Factor | Systematic underestimation of noise fold-change | Computationally intensive |

| SCTransform [24] | Negative Binomial with regularization | CV², Fano Factor | Systematic underestimation of noise fold-change | --- |

| scran [24] | Deconvolution of pooled data | CV², Fano Factor | Systematic underestimation of noise fold-change | --- |

| Generative Model with Spike-Ins [29] | Probabilistic model using ERCCs | Biological Variance | Excellent concordance, outperforms others for lowly expressed genes | Requires spike-in controls |

Table 2: iRECODE Performance in Dual Noise Reduction

| Metric | Raw Data | RECODE (Technical Noise Reduction) | iRECODE (Dual Noise Reduction) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Relative Error in Mean Expression | 11.1% - 14.3% | --- | 2.4% - 2.5% |

| Batch Mixing (iLISI Score) | Low | --- | High, comparable to Harmony |

| Cell-type Separation (cLISI Score) | High | --- | Preserved |

| Computational Efficiency | --- | --- | ~10x faster than sequential processing |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Noise-Aware Single-Cell Experiments

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Role in Noise Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| ERCC Spike-In Mix | External RNA controls | Quantifies technical noise and enables model-based decomposition of variance [29]. |

| CellPlex Kit (10x Genomics) | Sample multiplexing (up to 12 samples) | Reduces batch-to-batch technical variability by processing multiple samples in a single run [32]. |

| Nuclei Isolation Kit | Isolates nuclei from tough-to-dissociate tissues | Provides an alternative when single-cell suspensions are not feasible, reducing dissociation-induced noise [33]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Molecular barcodes for individual mRNA molecules | Corrects for PCR amplification bias, providing more quantitative counts and reducing technical noise [30]. |

| dCas9-VP64/VPR CRISPRa System | Targeted gene activation | Used in perturbation screens (e.g., [35]) to study the sufficiency of regulatory elements, requiring low-noise baselines. |

Methodological Workflow for Noise Quantification

The following diagram outlines a robust, evidence-based workflow for quantifying and addressing noise in a single-cell experiment, from design to analysis.

Computational Arsenal: Statistical, Machine Learning, and Hybrid Approaches for Noise Reduction

In droplet-based single-cell and single-nucleus RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq, snRNA-seq), background noise from cell-free ambient RNA represents a significant challenge for data interpretation. This contamination, which can constitute 3-35% of total counts per cell [1] [7], originates from lysed cells during tissue dissociation and can substantially distort biological interpretation by obscuring true cell-type marker genes and introducing false signals [36] [37]. For researchers investigating cellular heterogeneity, particularly in complex environments like tumor microenvironments, accurately distinguishing genuine biological signals from technical artifacts is paramount for drawing reliable conclusions in cancer research and drug development [37].

This technical support guide provides a comprehensive comparison of three established computational decontamination tools—CellBender, DecontX, and SoupX—to assist researchers in selecting and implementing appropriate background correction strategies for their single-cell genomics workflows.

Tool Performance Comparison

Independent benchmarking studies have evaluated the performance of ambient RNA removal tools across multiple datasets, revealing distinct strengths and limitations for each method.

Table 1: Overview of Background Correction Tools

| Tool | Algorithm Type | Input Requirements | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CellBender [36] [38] | Deep generative model (autoencoder) | Raw count matrix with empty droplets | - Most precise noise estimates [1]- Effective for moderately contaminated data [38]- Reduces false positives in marker genes | - Requires empty droplet data- Computationally intensive |

| SoupX [36] [39] | Statistical estimation | Raw or processed data (empty droplets optional) | - Works well with heavy contamination [38]- Manual mode allows expert curation- Straightforward implementation | - Automated mode may under-correct [39]- Manual mode requires prior knowledge- May over-correct lowly expressed genes [39] |

| DecontX [1] [39] | Bayesian mixture model | Processed count matrix (cluster info optional) | - No empty droplets required- Suitable for processed public data- Integrates with Celda pipeline | - Tends to under-correct highly contaminating genes [39]- Performance depends on clustering accuracy |

Table 2: Performance Benchmarking Results

| Performance Metric | CellBender | SoupX | DecontX |

|---|---|---|---|

| Background estimation accuracy | Most precise estimates [1] | Variable (better with manual mode) [39] | Less precise than CellBender [1] |

| Correction of highly contaminating genes | Effective [36] | Effective only in manual mode [39] | Tends to under-correct [39] |

| Impact on housekeeping genes | Preserves expression [39] | May over-correct (manual mode) [39] | Generally preserves expression [39] |

| Marker gene detection | Highest improvement [1] | Moderate improvement | Minimal improvement |

| Cell type clustering | Minor improvements [1] | Minor improvements [1] | Minor improvements [1] |

Performance Considerations

CellBender demonstrates superior performance in removing ambient contamination while preserving biological signals, particularly for moderately contaminated datasets [38]. It provides the most precise estimates of background noise levels and yields the highest improvement for marker gene detection [1].

SoupX performs well on samples with substantial contamination levels [38], though its automated mode often fails to correct contamination effectively. The manual mode, which utilizes researcher-defined background genes, achieves significantly better results but requires prior knowledge of expected cell-type markers [39].

DecontX offers convenience for analyzing processed datasets where empty droplet information is unavailable, but it under-corrects highly contaminating genes, particularly cell-type markers like Wap and Csn2 in mammary gland datasets [39].

Experimental Protocols

Standardized Workflow for Background Correction

The following workflow outlines a systematic approach for implementing background correction in single-cell RNA sequencing analysis:

Implementation Protocols

CellBender Protocol

- Input Preparation: Prepare raw gene-barcode matrix from Cell Ranger (including empty droplets) in H5 format.

- Parameter Configuration:

- Expected cells: Derive from cell calling statistics

- Total droplets included: 20,000 (typically)

- Epochs: 150-300 (use more for complex samples)

- Execution:

- Output Processing: Load the corrected matrix into Seurat or Scanpy for downstream analysis [36].

SoupX Protocol

- Input Preparation: Load raw and filtered count matrices; empty droplets are beneficial but optional.

- Contamination Estimation:

- Automated:

contaminationFraction = autoEstCont(channel)$est - Manual: Specify known marker genes that shouldn't be expressed in certain cell types

- Automated:

- Correction Execution:

- Validation: Check that marker genes specific to certain cell types are removed from inappropriate clusters [36] [39].

DecontX Protocol

- Input Preparation: Processed count matrix with optional cluster labels.

- Execution in R: Or using the standalone function:

- Output: Decontaminated counts stored in the

decontXcountsassay [39].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Issues and Solutions

Table 3: Troubleshooting Guide for Background Correction

| Problem | Potential Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Under-correction (marker genes still appear in wrong cell types) | - Low contamination estimate- Overclustered cells- Poor marker gene selection (SoupX) | - For DecontX: Use broader clustering [39]- For SoupX: Manually specify known marker genes [39]- For CellBender: Increase FPR parameter |

| Over-correction (loss of biological signal) | - Overestimation of contamination- Incorrect background profile | - For SoupX: Reduce contamination fraction [39]- For CellBender: Decrease FPR parameter- Validate with housekeeping genes [39] |

| Poor cell type separation after correction | - Overly aggressive correction- Insufficient signal remaining | - Compare with uncorrected data- Use less stringent parameters- Combine with other QC metrics |

| Computational resource issues | - Large dataset size- Memory-intensive algorithms | - For CellBender: Use GPU acceleration- Subsampling empty droplets- Increase system memory |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Which tool performs best for removing ambient RNA contamination?

- The optimal tool depends on your data and resources. CellBender generally provides the most precise noise estimates and effectively corrects highly contaminating genes [1] [39]. However, SoupX in manual mode can achieve comparable results when researchers have strong prior knowledge of cell-type-specific markers [39]. For quick analysis of processed data without empty droplets, DecontX offers a reasonable though less comprehensive solution [39].

Q2: How does background correction impact downstream analyses like differential expression?

- Effective background correction significantly improves differential expression analysis by reducing false positives. Studies demonstrate that after proper correction, biologically relevant pathways specific to cell subpopulations emerge more clearly, while ambient-related pathways are eliminated [36]. Marker gene detection shows the highest improvement after background removal [1].

Q3: Can background correction completely eliminate the need for experimental controls?

- No. Computational methods are complementary to, but not replacements for, good experimental practices. Methods like spike-in controls, careful tissue dissociation to minimize cell lysis, and FACS sorting remain important for reducing ambient RNA at the source [37] [39]. Computational correction works best when combined with optimized wet-lab protocols.

Q4: How do I validate the success of background correction in my dataset?

- Several validation approaches include:

- Check that known cell-type-specific markers (e.g., Wap and Csn2 in alveolar cells) are restricted to appropriate cell types [39]

- Monitor housekeeping genes (e.g., Rps14, Rpl37) to ensure they aren't over-corrected [39]

- Verify that biological interpretation improves with clearer separation of cell types

- Use cross-species or genotype-mixing experiments as ground truth when available [1]

Q5: Why might my cell type annotations change after background correction?

- Ambient RNA contamination can cause misannotation by making cells appear to express markers of multiple cell types. After correction, previously masked cell populations may emerge, and ambiguous cells can resolve into distinct types [36] [37]. This is particularly evident in neuronal cell types where contamination previously obscured rare populations like oligodendrocyte progenitor cells [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for scRNA-seq Decontamination Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium | Droplet-based single-cell partitioning | Platform generating data requiring ambient RNA correction [36] |

| External RNA Controls (ERCC) | Technical noise quantification | Distinguishing biological from technical variation [29] |

| Cell Hashing Antibodies | Multiplexing sample identification | Reduces batch effects and enables background estimation [37] |

| Mouse-Human Cell Mixtures | Method benchmarking | Ground truth for cross-species contamination assessment [1] |

| CAST/EiJ & C57BL/6J Mice | Genotype-based contamination tracking | SNP-based background quantification in complex tissues [1] |

| Nuclei Isolation Kits | Single-nucleus RNA preparation | snRNA-seq applications with potentially higher ambient RNA [39] |

The systematic comparison of CellBender, DecontX, and SoupX reveals that tool selection should be guided by specific experimental contexts and data characteristics. CellBender generally outperforms others for comprehensive contamination removal, particularly when empty droplet data is available, while SoupX's manual mode offers a viable alternative when researchers possess strong prior knowledge of expected cell-type markers [1] [39].

Background correction is not merely a technical preprocessing step but a critical determinant of biological insight in single-cell research. Proper implementation of these tools significantly enhances the accuracy of differential expression analysis, pathway enrichment findings, and cell type identification—ultimately strengthening conclusions in cancer research, drug development, and fundamental biology [36] [37]. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve, integrating robust computational correction with optimized experimental design will remain essential for distinguishing genuine biological signals from technical artifacts in increasingly complex research applications.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the exploration of cellular heterogeneity at unprecedented resolution. However, these datasets are frequently obscured by substantial technical noise and variability, particularly the prevalence of zero counts arising from both biological variation and technical dropout events [40]. These artifacts pose significant challenges for downstream analyses, including cell type identification, differential expression analysis, and rare cell population discovery. The field has witnessed a fundamental trade-off: statistical approaches maintain interpretability but exhibit limited capacity for capturing complex relationships, while deep learning methods demonstrate superior flexibility but are prone to overfitting and lack mechanistic interpretability [40]. To address these limitations, the ZILLNB (Zero-Inflated Latent factors Learning-based Negative Binomial) framework emerges as a novel computational approach that integrates statistical rigor with deep learning flexibility.

Understanding ZILLNB: Architecture and Core Components

Theoretical Foundation

ZILLNB represents a sophisticated computational framework that integrates zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) regression with deep generative modeling. This integration creates a unified approach for simultaneously addressing various sources of technical variability in scRNA-seq data while preserving biologically meaningful variation [40]. The model specifically addresses cell-specific measurement errors (e.g., library size variability), gene-specific errors, and experiment-specific variability through its structured architecture.

Core Components and Workflow

ZILLNB operates through three interconnected computational phases that systematically transform noisy input data into denoised output:

- Ensemble Deep Generative Modeling: employs an Information Variational Autoencoder (InfoVAE) combined with a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) to learn latent representations at both cellular and gene levels [40].

- ZINB Regression with Dynamic Covariates: utilizes the derived latent factors as dynamic covariates within a ZINB regression framework, with parameters iteratively optimized through an Expectation-Maximization algorithm [40].

- Systematic Variance Decomposition: explicitly separates technical variability from intrinsic biological heterogeneity, enabling precise data imputation [40].

The following diagram illustrates the complete ZILLNB workflow and the relationship between its core components:

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential computational components and their functions within the ZILLNB framework:

| Component | Type | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| InfoVAE (Information Variational Autoencoder) | Deep Learning Architecture | Learns latent manifold structures while mitigating overfitting through Maximum Mean Discrepancy regularization [40]. |

| GAN (Generative Adversarial Network) | Deep Learning Architecture | Enhances generative accuracy and refines latent space structure through adversarial training [40]. |

| ZINB (Zero-Inflated Negative Binomial) | Statistical Model | Explicitly models technical dropouts and count distribution, handling over-dispersion and excess zeros [40] [41]. |

| Expectation-Maximization (EM) Algorithm | Optimization Method | Iteratively refines latent representations and regression coefficients for precise parameter estimation [40]. |

| Mouse Cortex & Human PBMC Datasets | Benchmarking Data | Standardized biological datasets used for performance validation in comparative evaluations [40]. |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Validation

Standard Implementation Methodology

Data Preparation and Preprocessing

- Begin with raw UMI count matrices from scRNA-seq experiments

- Perform basic quality control: remove cells with exceptionally low gene counts or high mitochondrial content

- Retain the raw count structure without normalization to preserve statistical properties of the ZINB distribution

Latent Factor Learning Phase

- Initialize the ensemble InfoVAE-GAN architecture with adaptive weighting parameters (γ1, γ2) balancing reconstruction loss, prior alignment, and generative accuracy [40]

- Train the network to extract latent factors from both cell-wise and gene-wise perspectives

- Configure network dimensions based on dataset size (typical latent dimensions: 10-50 for cellular structure, 20-100 for gene structure)

ZINB Model Fitting

- Incorporate latent factors as dynamic covariates in the ZINB regression framework

- Implement iterative EM algorithm for parameter optimization until convergence (typically 5-15 iterations) [40]

- Regularize parameters to prevent overfitting, particularly for the latent factor matrix U and intercept terms

Validation and Benchmarking

- Compare against established methods: VIPER, scImpute, DCA, DeepImpute, SAVER, scMultiGAN, ALRA [40]

- Evaluate using multiple metrics: Adjusted Rand Index (ARI), Adjusted Mutual Information (AMI), AUC-ROC, AUC-PR [40]

- Validate biological discoveries through marker gene expression and pathway enrichment analyses

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

The following table summarizes ZILLNB's performance across standardized evaluation metrics compared to established methods:

| Evaluation Metric | ZILLNB Performance | Comparison Range vs. Other Methods | Key Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Type Classification (ARI) | Highest achieved ARI | +0.05 to +0.20 improvements | Mouse Cortex & Human PBMC [40] |

| Cell Type Classification (AMI) | Highest achieved AMI | +0.05 to +0.20 improvements | Mouse Cortex & Human PBMC [40] |

| Differential Expression (AUC-ROC) | Significantly improved | +0.05 to +0.30 improvements | Bulk RNA-seq validated [40] |

| Differential Expression (AUC-PR) | Significantly improved | +0.05 to +0.30 improvements | Bulk RNA-seq validated [40] |

| False Discovery Rate | Consistently lower | Notable reduction | Multiple scRNA-seq datasets [40] |

| Biological Discovery | Distinct fibroblast subpopulations identified | Validated transition states | Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis datasets [40] |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: How does ZILLNB fundamentally differ from other single-cell denoising methods like RECODE or standard ZINB regression?

A: ZILLNB represents a hybrid approach that integrates deep generative modeling with statistical frameworks. Unlike traditional ZINB regression that uses fixed covariates, ZILLNB employs deep learning-derived latent factors as dynamic covariates within the ZINB framework [40]. Compared to RECODE, which focuses on high-dimensional statistical approaches for technical noise reduction, ZILLNB simultaneously addresses multiple noise sources through its ensemble architecture and provides enhanced performance in cell type classification and differential expression analysis [40] [21].

Q2: What are the computational requirements for implementing ZILLNB, and how does it scale to large datasets?

A: ZILLNB utilizes an ensemble deep learning architecture that requires GPU acceleration for efficient training. The computational complexity scales with both the number of cells and genes, though the implementation includes optimizations such as MMD regularization instead of KL divergence to improve training stability [40]. For very large datasets (>$10^6$ cells), consider appropriate batch processing strategies and dimension adjustment of the latent spaces.

Q3: Can ZILLNB incorporate external covariates like batch information or experimental conditions?

A: Yes, the model architecture explicitly supports the inclusion of external covariates by extending the mean parameter equation with an additional term $γ{S×M}^\top W{S×N}$, where W represents covariate data and γ are corresponding regression coefficients [40]. During optimization, these can be concatenated with the latent factor matrix V without algorithm modifications.

Q4: How does ZILLNB ensure it doesn't overfit to technical noise, especially with limited sample sizes?

A: The framework incorporates multiple regularization strategies: (1) MMD regularization in the InfoVAE component replaces KL divergence for better prior alignment, (2) explicit regularization terms on the latent factor matrix U and intercept parameters during ZINB fitting, and (3) the iterative EM algorithm typically converges within few iterations, reducing overfitting risk [40].

Troubleshooting Common Implementation Challenges

Problem 1: Model Convergence Issues or Unstable Training

Symptoms: Fluctuating loss values, failure of the EM algorithm to converge within reasonable iterations, or parameter estimates diverging to extreme values.

Solutions:

- Scale continuous predictor variables to mean 0 and standard deviation 1 to improve numerical stability [42]

- Apply weakly informative priors (e.g., Normal(0,10)) on regression coefficients to stabilize estimates, particularly for the zero-inflation components [43]

- Adjust the adaptive weighting parameters (γ1, γ2) in the InfoVAE-GAN objective function to balance reconstruction accuracy and latent space regularization [40]

- For complete separation issues (often indicated by NA standard errors), consider relaxing priors on dispersion parameters or collecting more balanced data [42] [43]

Problem 2: Poor Denoising Performance or Biological Signal Loss

Symptoms: Inability to distinguish cell populations in denoised data, loss of rare cell types, or degradation of differential expression signals.

Solutions:

- Verify the latent dimension settings match the biological complexity (increase dimensions for heterogeneous populations)

- Examine the variance decomposition output to ensure technical variability is appropriately separated from biological heterogeneity

- Compare with ground truth datasets where available, and adjust the regularization strength if over-smoothing is observed

- Ensure the ZINB model adequately captures both the count distribution (negative binomial component) and dropout mechanism (Bernoulli component) [40]

Problem 3: Computational Performance and Memory Limitations

Symptoms: Excessive runtime for moderate-sized datasets, memory allocation errors, or inability to process full expression matrices.

Solutions:

- Implement data chunking strategies for large matrices

- Consider feature selection to reduce gene dimensionality before latent factor learning

- Utilize GPU acceleration which significantly speeds up the deep learning components

- Monitor convergence closely; the model typically requires few EM iterations (5-15) [40]

The following troubleshooting flowchart provides a systematic approach to diagnosing and resolving common ZILLNB implementation issues:

ZILLNB represents a significant advancement in single-cell data analysis by successfully integrating the interpretability of statistical modeling with the flexibility of deep learning. The framework provides a principled approach for addressing technical artifacts in scRNA-seq data while preserving biological variation, demonstrating robust performance across diverse analytical tasks including cell type identification, differential expression analysis, and rare cell population discovery [40]. As single-cell technologies continue to evolve, extending to epigenomic profiling through scHi-C and spatial transcriptomics [21], methodologies like ZILLNB will play an increasingly crucial role in extracting meaningful biological insights from complex, high-dimensional data. Future developments will likely focus on enhancing computational efficiency for massive-scale datasets, improving integration capabilities for multi-omic applications, and developing more sophisticated approaches for distinguishing subtle biological signals from technical artifacts in increasingly complex experimental designs.

In single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data analysis, the presence of technical noise and batch effects can obscure true biological signals, complicating the identification of cell types and the study of subtle biological phenomena. A critical preprocessing step involves transforming the raw, heteroskedastic count data into a more tractable form for downstream statistical analyses. This guide evaluates three core transformation approaches—the Delta method, Pearson residuals, and latent expression—within the broader context of mitigating noise in single-cell research. The following sections provide a detailed comparison, troubleshooting guide, and practical protocols for researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Concepts and Definitions

To effectively troubleshoot transformation methods, it is essential to understand the key concepts and terminology.

- Heteroskedasticity: In scRNA-seq data, the variance of gene counts depends on their mean expression level. Highly expressed genes show more variability than lowly expressed genes, violating the assumption of uniform variance required by many standard statistical methods [44].

- Dropouts: These are zero or near-zero counts in the data that arise from the low capture efficiency of mRNA molecules during the scRNA-seq protocol. They represent a major source of technical noise that can mask biological signals [21] [45].

- Latent Space: A lower-dimensional, compressed representation of the original high-dimensional data that aims to preserve only the essential biological features. It is a computational construct where similar cells are located near each other, and it is often learned by models like autoencoders [46].

- Size Factors: Cell-specific scaling factors that account for differences in total sequencing depth or library size between cells, enabling meaningful comparisons of expression levels across cells [44].

Comparison of Transformation Methods

The table below summarizes the three primary transformation strategies, their underlying principles, and key performance characteristics.

| Method | Core Principle | Key Formula / Approach | Strengths | Weaknesses / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delta Method & Shifted Logarithm [44] | Applies a non-linear function to stabilize variance based on a assumed mean-variance relationship. | - Variance-stabilizing transformation: g(y) = (1/√α) * acosh(2αy + 1)- Shifted logarithm: g(y) = log(y/s + y0) where y0 is a pseudo-count. |

- Simple and computationally efficient.- Performs well in benchmarks, often matching more complex methods. | - Choice of pseudo-count (y0) is unintuitive and critical.- Struggles to fully account for variations in cell size/sampling efficiency (size factors). |

| Pearson Residuals [44] [47] | Models counts with a Gamma-Poisson (Negative Binomial) GLM and calculates residuals normalized by expected variance. | r_gc = (y_gc - μ̂_gc) / √(μ̂_gc + α̂_g * μ̂_gc²) |

- Effectively stabilizes variance across genes.- Simultaneously accounts for sequencing depth and overdispersion.- Helps identify biologically variable genes. | - Model misspecification can lead to poor performance.- Can be computationally more intensive than the delta method. |

| Latent Expression (Sanity, Dino) [44] | Infers a latent, "true" expression state by fitting a probabilistic model to the observed counts and returning the posterior. | Fits models like log-normal Poisson or Gamma-Poisson mixtures to estimate the posterior distribution of latent expression. | - Provides a principled probabilistic framework.- Directly addresses the problem of technical noise and dropouts. | - Computationally expensive.- Theoretical properties do not always translate to superior benchmark performance. |

| Count-Based Factor Analysis (GLM-PCA, NewWave) [44] | Not a direct transformation; instead, it performs dimensionality reduction directly on the count data using a (Gamma-)Poisson model. | Fits a factor analysis model to the raw counts without a prior transformation step. | - Models the count nature of the data directly.- Avoids potential distortions from transformation. | - Output is a low-dimensional embedding, not a transformed feature matrix for all genes. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

1. My cell clusters are still separated by batch effects even after using the shifted logarithm transformation. What can I do?

- Problem: The delta method-based transformations, including the shifted log, may not adequately remove technical variations like batch effects or differences in sampling efficiency (size factors) [44].

- Solution:

- Consider Pearson Residuals or Latent Expression Methods: These approaches are designed to better handle such technical variations. For instance, the analytic Pearson residuals implemented in Scanpy simultaneously account for sequencing depth and stabilize variance [47].

- Use a Dedicated Batch Correction Tool: For severe batch effects, apply a method like Harmony, MNN-correct, or Scanorama after transformation. The iRECODE framework integrates technical noise reduction (like RECODE) with batch correction in a low-dimensional essential space, which can be more effective than separate steps [21].

2. How do I choose the right pseudo-count (y0) for the shifted logarithm transformation?

- Problem: The choice of pseudo-count is unintuitive and significantly impacts results. Using a fixed value like in CPM normalization (equivalent to

y0=0.005) or Seurat's method (y0=0.5) may not match your data's characteristics [44]. - Solution: Parameterize the transformation based on the typical overdispersion (

α) of your dataset. The relationy0 = 1 / (4α)provides a data-driven way to set the pseudo-count. You can estimateαfrom a preliminary model fit to your data [44].

3. I am concerned that imputation or latent expression methods might introduce false signals into my data. Is this a valid concern?

- Problem: Yes, this is a well-documented challenge. Some imputation and latent expression methods can distort the underlying biology, leading to over-smoothed data or false-positive findings in downstream analyses [48].

- Solution:

- Benchmark Performance: Evaluate the method's impact on your specific biological question. Use simulated data or known marker genes to check if the method enhances or obscures biological signals [48].

- Be Cautious with Downstream Analysis: When performing differential expression analysis after certain transformations (especially those that perform implicit imputation), use methods robust to potential over-smoothing.

- Consider Simpler Methods: A benchmark study found that a rather simple approach—the logarithm with a pseudo-count followed by PCA—can perform as well as or better than more sophisticated alternatives [44].

4. What should I do if my single-cell data type is not standard RNA-seq (e.g., epigenomic data like scHi-C)?

- Problem: Standard transformation methods developed for scRNA-seq may not be directly applicable to other single-cell modalities.