Optimizing Parameters in Systems Biology Models: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Parameter optimization is fundamental for developing predictive mathematical models of biological systems, yet it remains a significant challenge due to non-convexity, non-identifiability, and high computational cost.

Optimizing Parameters in Systems Biology Models: From Foundational Concepts to Advanced Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

Parameter optimization is fundamental for developing predictive mathematical models of biological systems, yet it remains a significant challenge due to non-convexity, non-identifiability, and high computational cost. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, covering foundational principles, advanced methodologies including Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) and Bayesian optimization, and practical troubleshooting strategies. We systematically compare global optimization algorithms like scatter search and multi-start methods, evaluate performance under realistic biological constraints such as noise and sparse data, and highlight emerging trends like automatic differentiation and multimodel inference. By integrating recent advances in computational systems biology, this resource aims to enhance model reliability and accelerate therapeutic discovery.

The Core Challenge: Understanding Parameter Estimation in Biological Systems

Defining the Parameter Estimation Problem in Nonlinear Dynamic Models

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the fundamental challenge of parameter estimation in nonlinear dynamic models? Parameter estimation involves determining the unknown constants (parameters) within a mathematical model that make the model's behavior best match observed experimental data. In nonlinear dynamic models, this is an inverse problem where you work backward from system outputs to find the inputs (parameters) that generated them. The goal is to find a parameter set that ensures the model can accurately recapitulate real-world process dynamics, which is foundational for all subsequent model-based analysis and predictions [1].

Why is parameter estimation particularly difficult in systems biology? Parameter estimation in systems biology presents unique challenges due to the inherent characteristics of biological systems and data [1]:

- Stiff Dynamics: Biological systems often exhibit processes operating on vastly different time scales, requiring specialized numerical solvers.

- Noisy and Sparse Data: Experimental measurements are often limited and contaminated with complex, sometimes non-Gaussian, noise.

- Partial Observability: Not all molecular species in a pathway can be measured directly, restricting the identifiability of parameters.

- Wide Parameter Ranges: Kinetic parameters and species abundances can vary by orders of magnitude.

My model fits the training data well but fails to predict new experiments. What is happening? This is a classic sign of overfitting, where the model has learned the noise in the training data rather than the underlying biological mechanism. This is a significant risk when using highly flexible, data-driven components like artificial neural networks (ANNs) within hybrid models. To mitigate this [1]:

- Apply Regularization: Use techniques like weight decay (L2 penalty) on ANN parameters to discourage overly complex models that capture noise.

- Use Multi-start Optimization: Run the estimation from many different initial parameter guesses to find a globally good solution, not just a local optimum.

- Perform Cross-Validation: Validate the model on a separate dataset that was not used during parameter estimation.

How can I quantify the certainty of my estimated parameters? For models that are highly nonlinear in their parameters, certainty (or confidence) can be quantified. The classical method approximates confidence regions using a linear approximation of the objective function's Hessian matrix. However, for greater accuracy—especially with larger errors or highly nonlinear models—it is recommended to use the full Hessian matrix to compute confidence bounds, providing a more reliable measure of parametric uncertainty [2].

What should I do when multiple models can describe the same biological pathway? Instead of selecting a single "best" model, you can use Bayesian Multi-Model Inference (MMI). This approach increases predictive certainty and robustness by creating a consensus prediction from all candidate models. It systematically combines predictions, weighted by each model's probabilistic support or predictive performance, leading to more reliable insights than relying on any single model [3].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

Problem 1: Poor Convergence of Optimization Algorithms

- Symptoms: The estimation algorithm fails to find a good solution, gets stuck in a local minimum, or the results are highly sensitive to the initial parameter guesses.

- Solutions:

- Employ a Multi-start Strategy: Run the optimization from many different, randomly sampled initial parameter values. This improves the exploration of the parameter space and the chances of finding a global optimum [1].

- Reparameterize Your Model: Use log-transformation for parameters that span several orders of magnitude. This improves numerical conditioning and enforces positivity constraints naturally [1].

- Choose an Appropriate Algorithm: For certain problems, derivative-free methods like the Nelder-Mead simplex can be more robust and consistent than gradient-based methods [4].

Problem 2: Model Predictions are Sensitive to Small Parameter Changes

- Symptoms: Tiny perturbations to the parameter values lead to large, unrealistic changes in model outputs, indicating potential practical non-identifiability.

- Solutions:

- Conduct a Practical Identifiability Analysis: Use the Hessian matrix at the optimal parameter set to compute confidence intervals. Wide confidence intervals indicate that the data cannot pin down that parameter's value with high certainty [2].

- Incorporate Prior Knowledge: Use Bayesian estimation to include prior distributions on parameters, which can regularize the problem and guide the estimation when data is insufficient [3].

- Consider Multi-Model Inference: Acknowledge model uncertainty by using MMI, which provides predictions that are robust to the choice of any single model structure [3].

Problem 3: Handling Noisy and Imperfect Experimental Data

- Symptoms: Parameter estimates are unstable or biased due to outliers or non-Gaussian noise in the measurements.

- Solutions:

- Use Robust Objective Functions: For data with impulsive noise (outliers), replace the standard sum of squared errors with a more robust criterion, such as the continuous logarithmic mixed p-norm, which is less sensitive to extreme values [5].

- Employ Bayesian Filtering Methods: For dynamic time-series data, methods like the Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) can be highly effective for joint state and parameter estimation in the presence of noise [6].

- Define an Accurate Error Model: Use Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) to simultaneously estimate both the model parameters and the parameters of the noise distribution (e.g., its variance) [1].

Methodologies for Parameter Estimation

The table below summarizes the core methodologies discussed in the search results for estimating parameters in nonlinear dynamic models.

| Method Category | Key Principle | Ideal Use Case | Example Algorithms / References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Optimization | Minimizes a cost function (e.g., sum of squared errors) between model predictions and data. | Models with a well-defined mechanistic structure and good initial parameter guesses. | Nelder-Mead Simplex, Levenberg-Marquardt [4]. |

| Bayesian Inference | Treats parameters as random variables, estimating their posterior probability distribution given the data. | Quantifying uncertainty, incorporating prior knowledge, and handling noise [6] [3]. | Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), Bayesian Filtering (UKF, EnKF, PF) [6]. |

| Physics-Informed Hybrid Models | Combines mechanistic ODE/PDE models with data-driven neural networks to model unknown processes. | Systems where the model is only partially known, or processes are too complex to specify fully [7] [1]. | Universal Differential Equations (UDEs), Physics-Informed Neural Networks (PINNs) [1]. |

| Two-Stage & Recursive Methods | Derives identification models (e.g., via Laplace transforms) and uses iterative/recursive updates. | Linear Time-Invariant (LTI) continuous-time systems, or as components in larger nonlinear estimation problems [8]. | Two-Stage Recursive Least Squares, Stochastic Gradient Algorithms [8]. |

| Bayesian Optimization | A global optimization strategy for expensive black-box functions; builds a surrogate probabilistic model to guide the search. | Optimizing experimental conditions (e.g., media composition) with very few experimental cycles [9]. | Gaussian Processes (GP) with Acquisition Functions (EI, UCB, PI) [9]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Training a Universal Differential Equation (UDE)

This protocol outlines the steps for estimating parameters in a nonlinear dynamic model using the UDE framework, which integrates known mechanistic equations with neural networks to represent unknown dynamics [1].

1. Problem Formulation

- Objective: Estimate the mechanistic parameters ( \theta_M ) of your ODE model, where one or more terms are represented by an Artificial Neural Network (ANN).

- Model Structure: Define the UDE system, e.g., ( \dot{y} = f(y, \theta_M) + ANN(y) ), where ( y ) is the state vector and ( ANN(y) ) learns the unknown dynamics.

2. Implementation and Training Pipeline

- Parameter Transformation: Apply log-transformation to parameters that must remain positive or span orders of magnitude. This improves numerical stability [1].

- Regularization: Apply weight decay (L2 regularization) to the ANN parameters ( \theta{ANN} ) by adding a penalty term ( \lambda \|\theta{ANN}\|_2^2 ) to the loss function. This prevents the ANN from overfitting and overshadowing the mechanistic model [1].

- Multi-start Optimization: Sample numerous initial values for both ( \thetaM ) and ( \theta{ANN} ), as well as for hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, ANN size). This is crucial for finding a global solution [1].

- Solver Selection: Use specialized numerical solvers (e.g.,

Tsit5for non-stiff,KenCarp4for stiff systems) to handle the potentially stiff dynamics of biological models efficiently and accurately [1].

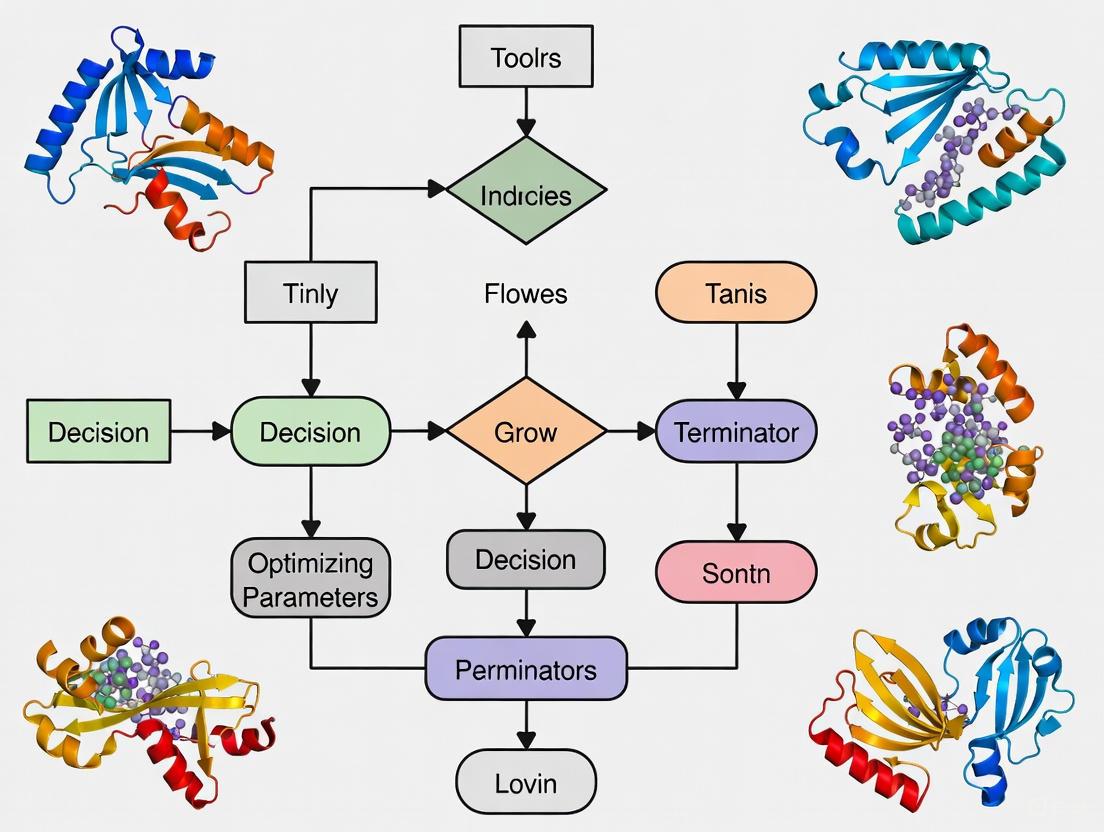

The following workflow diagram illustrates the UDE training pipeline.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Bayesian Multi-Model Inference (MMI)

This protocol describes how to create a robust consensus predictor from a set of candidate models, increasing certainty in predictions [3].

1. Problem Formulation

- Objective: Create a multimodel estimate ( p(q | d{train}, \mathfrak{M}K) ) for a Quantity of Interest (QoI) ( q ) (e.g., a dynamic trajectory or dose-response curve), using a set of models ( \mathfrak{M}K = {\mathcal{M}1, \ldots, \mathcal{M}_K} ).

2. Implementation and Workflow

- Model Calibration: For each model ( \mathcal{M}k ) in the set, use Bayesian inference to estimate its parameters and obtain its posterior predictive distribution ( p(qk | \mathcal{M}k, d{train}) ) for the QoI.

- Weight Calculation: Compute the weight ( wk ) for each model using one of the following methods:

- Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA): ( wk^{BMA} = p(\mathcal{M}k | d{train}) ), based on the model's marginal likelihood.

- Pseudo-BMA: Weights are based on the expected log pointwise predictive density (ELPD), estimating each model's performance on new data.

- Stacking: Finds the model weight combination that maximizes the predictive performance of the combined ensemble.

- Consensus Prediction: Form the final MMI prediction as a weighted average: ( p(q | d{train}, \mathfrak{M}K) = \sum{k=1}^K wk p(qk | \mathcal{M}k, d_{train}) ).

The logical flow of the Bayesian MMI process is shown below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key computational tools and methodologies essential for tackling parameter estimation problems, as identified in the search results.

| Item / Methodology | Function in Parameter Estimation | Key Reference / Context |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) | A flexible framework that combines mechanistic ODEs with artificial neural networks (ANNs) to model systems with partially unknown dynamics. | [1] |

| Physics-Informed Regression (PIR) | An efficient hybrid method using regularized ordinary least squares for models linear in their parameters. Shows superior speed/performance vs. PINNs for some models. | [7] |

| Bayesian Multi-Model Inference (MMI) | A disciplined approach to combining predictions from multiple candidate models to increase certainty and robustness. | [3] |

| Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) | A Bayesian filtering method effective for joint state and parameter estimation in nonlinear systems, often outperforming EKF and EnKF. | [6] |

| Nelder-Mead Simplex Method | A robust, derivative-free optimization algorithm that can be reliable for parameter estimation, especially in chaotic systems. | [4] |

| Hessian Matrix Calculation | Used for quantifying parameter certainty (confidence bounds) in highly nonlinear models, providing more accurate uncertainty estimates. | [2] |

| Continuous Logarithmic Mixed p-norm | A robust objective function used for parameter estimation in the presence of impulsive noise (outliers) in errors-in-variables systems. | [5] |

Troubleshooting Guide

FAQ: Model Non-identifiability

Q1: What is the difference between structural and practical non-identifiability? Structural non-identifiability is an intrinsic model property where different parameter combinations yield identical model outputs, making it impossible to distinguish between them even with perfect, noise-free data [10]. Practical non-identifiability arises from limitations in your dataset, where the available data lack the quality or quantity to precisely estimate parameters, even if the model is structurally identifiable [11] [12].

Q2: How can I diagnose non-identifiability in my model? You can diagnose it through several methods:

- Profile Likelihood: This is a reliable method where you examine the likelihood function's curvature. A flat profile indicates that a parameter is non-identifiable [12].

- Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) Sampling: Using MCMC with broad priors can reveal non-identifiability. If the posterior distributions for parameters remain very broad (resembling the priors) or show strong correlations, it suggests the data did not provide sufficient information to identify them [11] [13].

- Examine Pairs Plots: Strong linear correlations between parameters in pairs plots from MCMC samples are a clear sign of an identifiability problem [13].

Q3: What are some strategies to resolve non-identifiability?

- For Structural Non-identifiability: Use model reduction or reparameterization to create a simpler, identifiable model. This often involves combining non-identifiable parameters into a single, composite parameter [11] [14].

- For Practical Non-identifiability: The most effective strategy is to acquire more informative data [10]. This can be guided by Optimal Experiment Design to determine the most valuable data to collect [10]. Alternatively, incorporating regularization or Bayesian priors can constrain parameter values based on existing knowledge [1] [10].

FAQ: Local Minima in Optimization

Q1: How can I tell if my optimization is stuck in a local minimum? Common indicators include:

- The loss function fails to decrease after many iterations [15].

- Model parameters stop changing significantly [15].

- The model shows poor predictive performance, suggesting it has not found a good solution despite the algorithm converging.

Q2: What techniques can help escape local minima?

- Multi-start Optimization: Run the optimization algorithm many times from different, randomly chosen initial parameter values. This increases the chance of starting near the global minimum [15] [1].

- Use Specialized Algorithms: Algorithms like stochastic gradient descent (SGD), momentum, or Nesterov momentum introduce noise or inertia that can help the optimizer "jump" out of shallow local minima [15].

- Regularization: Adding a regularization term (like L2 penalty) to the loss function penalizes overly complex parameter values, which can smooth the loss landscape and reduce the number of local minima [15] [1].

FAQ: Stiff System Dynamics

Q1: Why are stiff systems particularly challenging for systems biology models? Stiff systems are challenging because they involve processes operating on vastly different timescales (e.g., fast and slow biochemical reactions). Explicit numerical solvers require extremely small step sizes to remain stable, leading to prohibitively long computation times [16] [17].

Q2: What are the best computational methods for handling stiff dynamics?

- Use Implicit Solvers: Switch from explicit (e.g., explicit Runge-Kutta) to implicit solvers (e.g., KenCarp4) or solvers designed for stiff systems. Implicit methods remain stable with much larger step sizes [1] [17].

- Apply Logarithmic Transformation: Working with log-transformed parameters and state variables can help manage parameters that span several orders of magnitude and improve optimizer performance [16] [1].

- Specialized Neural ODEs: When using machine learning approaches like Neural ODEs, employ implicit single-step methods designed specifically for stiff systems to ensure stable training [17].

Diagnostic Tables for Common Obstacles

Table 1: Symptoms and Solutions for Non-identifiability

| Symptom | Potential Diagnosis | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Strong correlations between parameters in MCMC pairs plots [13] | Practical non-identifiability | Conduct a profile likelihood analysis; consider model reduction or collect more data [11] [12]. |

| Flat profile likelihood for one or more parameters [12] | Practical or structural non-identifiability | Perform structural identifiability analysis (e.g., with DAISY/GenSSI); use reparameterization [14] [10]. |

| Very broad posterior distributions despite sufficient sampling [11] | Practical non-identifiability | Incorporate stronger priors from literature or design new experiments for more informative data [10]. |

Table 2: Comparison of Optimization Algorithms and Their Properties

| Algorithm | Resists Local Minima? | Key Mechanism | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gradient Descent | No | Follows steepest descent | Convex problems, good baseline |

| Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) | Yes | Uses random data subsets, introducing noise [15] | Large-scale problems, deep learning |

| Momentum / Nesterov Momentum | Yes | Accumulates velocity from past gradients to pass through small bumps [15] | Loss landscapes with high curvature |

| Genetic Algorithms | Yes | Population-based global search [16] [15] | Complex, non-convex problems with many parameters |

| Multi-start Local Search | Yes | Runs many local optimizations from different starting points [1] | When good local optimizers are available |

Table 3: Solvers for Stiff and Non-Stiff ODE Systems

| Solver Type | Representative Algorithms | Stiff Systems? | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explicit | Euler, RK4, Tsit5 [1] | No | Efficient for non-stiff problems; can become unstable with stiff systems. |

| Implicit | Backward Euler, KenCarp4 [1] [17] | Yes | Stable for stiff systems; requires solving a system of equations per step (more computational overhead). |

| Adaptive | Many explicit and implicit solvers | Varies | Automatically adjusts step size to balance efficiency and accuracy; essential for practical modeling. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: An Iterative Workflow for Managing Non-identifiable Models

This protocol outlines a sequential approach to constrain model parameters and build predictive power, even when full identifiability is not immediately achievable [11].

1. Principle: Instead of reducing a model prematurely, iteratively train it on expanding datasets. Each iteration reduces the dimensionality of the plausible parameter space and enables new, testable predictions [11].

2. Procedure: a. Initial Experiment: Perform an experiment and measure a single, key model variable under a defined stimulation protocol. b. Model Training: Train the model on this limited dataset using Bayesian methods (e.g., MCMC) to obtain a set of "plausible parameters" [11]. c. Predictive Assessment: Use the trained model to predict the same variable's trajectory under a different stimulation protocol. A non-identifiable model can still make accurate predictions for the measured variable [11]. d. Iterate: Expand the training dataset to include an additional variable and repeat the training and prediction steps. This further reduces parameter space dimensionality and allows prediction of the newly measured variable [11].

3. Diagram: Iterative Modeling Workflow:

Protocol 2: A Multi-start Pipeline for Robust UDE Training

This protocol is designed for training Universal Differential Equations (UDEs), which combine mechanistic ODEs with neural networks, and is critical for avoiding local minima [1].

1. Principle: Systematically explore the hyperparameter and initial parameter space to find a high-quality, reproducible solution instead of converging on a poor local minimum.

2. Procedure: a. Joint Sampling: Sample initial values for both mechanistic parameters (θ_M) and neural network parameters (θ_ANN), alongside hyperparameters (e.g., learning rate, ANN size). b. Apply Constraints: Use log-transformation for parameters to enforce positivity and handle large value ranges. Apply regularization (e.g., L2 weight decay) to the ANN to prevent overfitting [1]. c. Multi-start Optimization: Launch a large number of independent optimization runs from the sampled starting points. d. Validation and Selection: Use early stopping on a validation set to prevent overfitting. Select the best model from all runs based on validation performance [1].

Key Signaling Pathway Diagram

The diagram below illustrates a canonical biochemical signaling cascade with a negative feedback loop, a motif common in systems biology research (e.g., MAPK pathway) [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Computational Tools for Systems Biology Modeling

| Tool / Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Profile Likelihood | A statistical method to assess practical identifiability and construct accurate confidence intervals for parameters and predictions [12]. | Diagnosing non-identifiability; Profile-Wise Analysis (PWA) workflows. |

| Implicit ODE Solvers (KenCarp4) | Numerical algorithms for stable integration of differential equations that exhibit stiffness [1]. | Simulating models of biochemical systems with fast and slow timescales. |

| Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) | A Bayesian sampling method to estimate posterior distributions of model parameters [11]. | Model calibration and uncertainty quantification; diagnosing practical identifiability. |

| Radial Basis Function Network (RBFN) | A type of artificial neural network that can approximate non-linear time-courses, sometimes used to reduce computational cost in parameter estimation [16]. | Accelerating parameter estimation for stiff biochemical models. |

| Universal Differential Equation (UDE) | A hybrid modeling framework that combines mechanistic ODEs with trainable neural networks to represent unknown processes [1]. | Building models when the underlying mechanisms are only partially known. |

| Multi-start Optimization | A simple global optimization strategy that runs a local optimizer from many random starting points [1]. | Mitigating the risk of convergence to poor local minima. |

| Structural Identifiability Software (DAISY, GenSSI) | Tools that automatically analyze a model's structural identifiability using computer algebra [12]. | Checking for fundamental identifiability issues before attempting parameter estimation. |

FAQs on Objective Functions for Parameter Estimation

What is the core difference between Least-Squares and Maximum Likelihood Estimation?

Least-Squares (LS) estimation aims to find parameter values that minimize the sum of squared differences between observed data and model predictions. It is a deterministic approach often used for its computational simplicity and does not require assumptions about the underlying data distribution, though it performs optimally when errors are normally distributed [18].

Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) seeks parameter values that maximize the likelihood function, which is the probability of observing the given data under the model. MLE is a probabilistic method that explicitly incorporates assumptions about the error distribution (e.g., Gaussian, Poisson) and provides a consistent framework for inference [19] [20]. For normally distributed errors, MLE is equivalent to least-squares [21].

When should I use a Chi-Square objective function in systems biology?

The Chi-Square objective function is particularly useful when you need to account for varying uncertainty in your measurements. It is appropriate when errors are normally distributed but the variance is not constant across data points, or when working with categorical data arranged in contingency tables [22].

In systems biology, use Chi-Square when:

- You have reliable estimates of measurement errors for different experimental conditions

- You are working with count data or categorical outcomes (e.g., cell type classifications)

- You need to test goodness-of-fit between your model and experimental data [22]

How do I choose the right objective function for my parameter estimation problem?

Consider these factors when selecting an objective function:

- Data type: Continuous measurements (LS, MLE) vs. categorical data (Chi-Square) [22]

- Error structure: Known measurement variances (Chi-Square), normally distributed errors (LS), or specific distributional assumptions (MLE) [23]

- Computational considerations: LS is often computationally simpler, while MLE may require more sophisticated optimization [19]

- Desired outputs: Parameter uncertainties (MLE), goodness-of-fit measures (Chi-Square), or simple point estimates (LS) [19]

For dynamic models in systems biology, studies have shown that the choice of objective function significantly impacts parameter identifiability and optimization performance [23].

My parameter estimation fails to converge. What troubleshooting steps should I take?

- Check your objective function scaling: For relative data (e.g., Western blot densities), consider Data-Driven Normalization of Simulations (DNS) instead of Scaling Factors (SF), as DNS does not introduce additional parameters and can improve convergence [23]

- Examine parameter identifiability: Some parameters may be unidentifiable even with perfect data. Try fixing certain parameters or collecting additional experimental data [23]

- Try different optimization algorithms: Gradient-based methods (e.g., Levenberg-Marquardt) work well for smooth problems, while hybrid stochastic-deterministic methods (e.g., GLSDC) can better escape local minima [23]

- Verify your gradient calculations: Compare finite difference approximations with sensitivity equations if using gradient-based optimization [23]

What are the advantages and limitations of Maximum Likelihood Estimation?

Advantages:

- Provides consistent approach to parameter estimation across diverse problems [19]

- Offers desirable mathematical properties: becomes minimum variance unbiased as sample size increases [19]

- Enables calculation of confidence intervals and hypothesis tests [19]

- Framework naturally accommodates different probability distributions [20]

Limitations:

- Requires deriving specific likelihood equations for each problem [19]

- Computationally challenging for complex models [19]

- Can produce biased estimates for small sample sizes [19]

- Sensitive to choice of starting values for optimization [19]

Comparison of Objective Functions

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, requirements, and applications of the three objective functions:

| Feature | Least-Squares | Maximum Likelihood | Chi-Square |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematical Form | Minimize $\sum{i=1}^n (yi - f(x_i, \beta))^2$ [18] | Maximize $L(\theta) = \prod{i=1}^n P(yi | \theta)$ [19] | Minimize $\sum \frac{(O-E)^2}{E}$ [22] |

| Data Requirements | Continuous numerical data | Depends on specified distribution | Frequencies or counts in categories [22] |

| Error Assumptions | Errors have zero mean, constant variance | Errors follow specified probability distribution | Observations are independent; expected frequencies ≥5 [22] |

| Outputs Provided | Parameter estimates, goodness-of-fit | Parameter estimates, confidence intervals, hypothesis tests | Goodness-of-fit, tests of independence [22] |

| Computational Complexity | Low to moderate | Moderate to high (depends on likelihood) | Low |

| Common Applications in Systems Biology | Linear and nonlinear regression of continuous data | Parameter estimation in stochastic models | Analysis of categorical outcomes, model selection [24] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Parameter Estimation Using Maximum Likelihood

Purpose: Estimate kinetic parameters in ODE models of signaling pathways using experimental time-course data.

Materials:

- Experimental data (e.g., Western blot, proteomics, RT-qPCR)

- Mathematical model of the system (ODE format)

- Optimization software (e.g., COPASI, Data2Dynamics, or custom algorithms) [23]

Procedure:

- Formulate the likelihood function based on assumed error distribution (e.g., normal, log-normal)

- Select optimization algorithm (gradient-based for smooth problems, hybrid methods for complex landscapes) [23]

- Handle data scaling using either:

- Run optimization with multiple restarts to avoid local minima

- Validate estimates using profile likelihood or bootstrap methods

Troubleshooting Tips:

- For non-identifiable parameters, consider model reduction or additional experimental measurements [23]

- If using relative data, DNS approach reduces non-identifiability compared to SF [23]

- For poor convergence, try hybrid stochastic-deterministic algorithms like GLSDC [23]

Protocol 2: Model Selection Using Chi-Square Tests

Purpose: Compare competing models and select the best representation of biological system.

Materials:

- Experimental data with categorical outcomes or binned continuous data

- Multiple candidate models

- Statistical computing environment

Procedure:

- Calculate expected values for each category under model assumptions: $E = \frac{(Row\ Marginal \times Column\ Marginal)}{Total\ Sample\ Size}$ [22]

- Compute Chi-Square statistic: $\chi^2 = \sum \frac{(O-E)^2}{E}$ where O = observed values, E = expected values [22]

- Determine degrees of freedom: (number of categories - 1 - number of estimated parameters)

- Compare calculated $\chi^2$ to critical value from Chi-Square distribution

- Follow significant result with strength test (e.g., Cramer's V) to quantify relationship strength [22]

Assumption Verification:

- Check that expected frequency ≥5 in at least 80% of cells, and no cell has expected <1 [22]

- Verify observations are independent and categories are mutually exclusive [22]

Workflow Visualization

Parameter Estimation Decision Framework

Optimization Process for Systems Biology

Research Reagent Solutions

The table below outlines key computational tools and resources for implementing objective functions in systems biology research:

| Resource Type | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Optimization Software | COPASI [23], Data2Dynamics [23], PEPSSBI [23] | Parameter estimation and model simulation with support for different objective functions |

| Algorithms for MLE | Levenberg-Marquardt (LevMar) [23], Genetic Local Search (GLSDC) [23], LSQNONLIN [23] | Maximum likelihood estimation with sensitivity equations or finite differences |

| Data Scaling Methods | Scaling Factors (SF) [23], Data-Driven Normalization of Simulations (DNS) [23] | Align simulation outputs with experimental data scales |

| Model Evaluation Tools | Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) [24], Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) [24], Chi-Square goodness-of-fit [22] | Compare model performance and select optimal model complexity |

In systems biology and drug development, accurately scaling biological data is paramount for creating predictive computational models, such as condition-specific Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) [25]. The choice between using pre-defined scaling factors (like allometric principles) and employing data-driven normalization strategies (DNS) directly impacts the validity of simulations of human physiology and drug responses [26] [27]. This technical support center provides FAQs and troubleshooting guides to help researchers navigate these critical decisions in their experiments.

FAQs: Core Concepts and Definitions

1. What is the fundamental difference between a scaling factor and data-driven normalization?

- Scaling Factors: Often based on established principles like allometric scaling, these use pre-defined coefficients to relate organ size or function to body mass. They are derived from interspecies comparisons and provide a theoretical starting point for sizing components in coupled systems, like multi-organ chips [26].

- Data-Driven Normalization: These methods use the data itself to correct for technical variations. They do not rely on a priori assumptions about constitutive genes or fixed ratios. Instead, they identify stable patterns within the dataset to adjust all measurements, making them robust to experimental conditions that might affect traditional "housekeeping" genes [27].

2. When should I use allometric scaling in my systems biology model?

Allometric scaling is an excellent starting point when designing coupled in vitro systems, such as multi-organ-on-a-chip devices, where you need to define the relative functional sizes of different organs (e.g., liver, heart, brain) to replicate human physiology [26]. However, it has limitations. Simple allometric scaling can fail for certain organs (e.g., it would produce a micro-brain larger than the entire micro-human body) or for critical cellular functions that do not scale with size, such as endothelial layers that must remain one cell thick [26].

3. My RNA-seq data is for a specific human disease. Why should I avoid simple within-sample normalization methods like FPKM or TPM?

While within-sample methods like FPKM and TPM are popular, benchmark studies have shown that when their output is used to build condition-specific metabolic models (GEMs), they can produce models with high variability in the number of active reactions between samples [25]. Between-sample normalization methods like RLE (Relative Log Expression) and TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) produce more consistent and reliable models for downstream analysis, as they are better at reducing technical biases across samples [25].

4. I am working with data that contains outliers. Which scaling method is most appropriate?

For data with significant outliers, Robust Scaling is generally recommended [28] [29]. Unlike StandardScaler or MinMaxScaler, which use the mean/standard deviation and min/max respectively, RobustScaler uses the median and the interquartile range (IQR). The IQR represents the middle 50% of the data, making the scaling process resistant to the influence of marginal outliers [28].

5. What does "quantile normalization" assume about my data, and when is it used?

Quantile normalization assumes that the overall distribution of gene transcript levels is nearly constant across the different samples being compared [27]. It works by forcing the distribution of expression values to be identical across all samples. This method is particularly useful in high-throughput qPCR experiments where genes from a single sample are distributed across multiple plates, as it can effectively remove plate-to-plate technical variations [27].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: High Variability in Model Outputs

- Symptoms: When using transcriptomic data to constrain genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs), the resulting models (e.g., from iMAT or INIT algorithms) show a wide range in the number of active reactions across samples from the same condition [25].

- Possible Cause: The use of within-sample normalization methods (e.g., TPM, FPKM) on RNA-seq data.

- Solution:

- Re-normalize your RNA-seq data using a between-sample method such as RLE (from DESeq2), TMM (from edgeR), or GeTMM [25].

- Rebuild your condition-specific GEMs. Benchmarking shows that between-sample methods significantly reduce inter-sample variability in the number of active reactions [25].

- Protocol - Applying RLE Normalization:

- Use the

DESeq2package in R. - The RLE method calculates a scaling factor for each sample as the median of the ratios of a gene's count to its geometric mean across all samples.

- These factors are applied to the raw read counts to normalize the data [25].

- Use the

Problem 2: Poor Performance in Machine Learning Algorithms

- Symptoms: A model (e.g., SVM, K-Nearest Neighbors) fails to converge, converges slowly, or has poor predictive performance [30] [28] [29].

- Possible Causes:

- Solution:

- Apply feature scaling to all numeric features.

- Choose the right scaler based on your data and algorithm (see Table 1).

- Protocol - StandardScaler:

Problem 3: Scaling Failure in Multi-Organ Systems

- Symptoms: A coupled organ-on-chip system does not exhibit physiologically realistic interactions, even when individual organs are correctly sized [26].

- Possible Cause: Using strict allometric scaling for all organs, which can break down for functionally critical components that cannot be scaled down physically (e.g., a heart must be at least one cardiomyocyte thick).

- Solution:

- Shift from pure allometric scaling to functional scaling.

- Design each organ to make a suitable physiological contribution to the coupled system, even if this deviates from mass-based scaling predictions [26].

- Consider the system as a set of "interconnected histological sections" rather than a perfectly scaled-down human [26].

Table 1: Comparison of Common Data Scaling and Normalization Techniques

| Method | Type | Key Formula | Sensitivity to Outliers | Ideal Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allometric Scaling | Scaling Factor | ( M = A \times M_b^B ) (Organ Mass) [26] | N/A | Multi-organ system design, initial PK/PD model setup [26] |

| StandardScaler | Feature Scaling | ( X{scaled} = \frac{Xi - \mu}{\sigma} ) [28] | Moderate | Many ML algorithms (e.g., SVM, linear regression), assumes ~normal data [28] [29] |

| MinMaxScaler | Feature Scaling | ( X{scaled} = \frac{Xi - X{min}}{X{max} - X_{min}} ) [28] | High | Neural networks, data bounded in an interval (e.g., [0, 1]) [30] [28] |

| RobustScaler | Feature Scaling | ( X{scaled} = \frac{Xi - X_{median}}{IQR} ) [28] | Low | Data with outliers, skewed distributions [28] [29] |

| Quantile Normalization | Data-Driven (DNS) | Makes distributions identical by enforcing average quantiles [27] | Low | High-throughput qPCR, removing plate-effects, cross-sample normalization [27] |

| Rank-Invariant Normalization | Data-Driven (DNS) | Uses genes with stable rank order across samples for scaling [27] | Low | Situations where housekeeping genes are not stable; requires large gene sets [27] |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a decision workflow for selecting an appropriate scaling or normalization strategy, integrating both biological scaling factors and data-driven methods for systems biology research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Featured Experiments

| Item / Resource | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Cell Culture Medium | A chemically defined medium to support multiple cell types in a coupled system; typically without red blood cells to avoid viscosity issues at small scales [26]. | Perfusing multi-organ-on-a-chip systems (e.g., milliHuman or microHuman platforms) [26]. |

| DESeq2 (R package) | Provides the RLE (Relative Log Expression) normalization method for RNA-seq count data [25]. | Normalizing transcriptomic data before mapping to Genome-Scale Metabolic Models (GEMs) to reduce model variability [25]. |

| edgeR (R package) | Provides the TMM (Trimmed Mean of M-values) normalization method for RNA-seq data [25]. | An alternative between-sample normalization method for robust differential expression analysis and GEM construction [25]. |

| scikit-learn (Python library) | Provides a comprehensive suite of scalers (StandardScaler, MinMaxScaler, RobustScaler, etc.) for machine learning preprocessing [28] [29]. |

Preparing numerical feature data for training classifiers or regression models in drug discovery pipelines [28]. |

| ColorBrewer / Coblis | Tools for selecting accessible color schemes and simulating color-deficient vision, respectively [31]. | Creating clear, accessible data visualizations for publications and presentations that accurately represent scaled data [31]. |

The Critical Role of Constraints and Prior Knowledge in Biological Systems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the main types of constraints used in parameter optimization for systems biology models?

Constraints are mathematical expressions that incorporate prior knowledge into the model fitting process. The table below summarizes the primary types used in systems biology.

| Constraint Type | Description | Primary Use in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Differential Elimination (DE) Constraints [32] | Derived algebraically from the model's differential equations; represent relationships between parameters and variables that must hold true. | Introduced directly into the objective function to drastically improve parameter estimation accuracy, especially with unmeasured variables. |

| Profile Likelihood Constraints [33] | Used to define confidence intervals for parameters by exploring the likelihood function as a single parameter of interest is varied. | Estimates practical identifiability of parameters and produces reliable confidence intervals for model parameters. |

| Maximal Knowledge-Driven Information Prior (MKDIP) [34] | A formal prior probability distribution constructed from biological knowledge (e.g., pathway information) via a constrained optimization framework. | Provides a rigorous method to incorporate prior biological knowledge into Bayesian classifier design, improving performance with small samples. |

FAQ 2: My model parameters are not practically identifiable, leading to infinite confidence intervals. What should I do?

This is a common issue where the available data is insufficient to precisely determine parameter values. The Profile Likelihood approach is a reliable method to diagnose and address this [33].

- Solution: Implement the Confidence Intervals by Constraint Optimization (CICO) algorithm.

- Methodology:

- The algorithm calculates a profile likelihood for each parameter.

- It explores the likelihood function by varying one parameter and re-optimizing all others.

- Parameters with finite confidence intervals that fall below a critical threshold (based on the χ² distribution) are considered practically identifiable. Those with infinite intervals are non-identifiable [33].

- Software Package: You can implement this using the freely available

LikelihoodProfilerpackage in Julia or Python [33].

FAQ 3: How can I incorporate existing biological pathway knowledge into a Bayesian model?

When you have knowledge about gene regulatory relationships, you can formalize it into a prior distribution using the Maximal Knowledge-Driven Information Prior (MKDIP) framework [34].

- Procedure:

- Formulate Constraints: Translate known pathway information into probabilistic constraints. For example, "the probability that Gene A is up-regulated, given that its activator Gene B is up-regulated, is high."

- Prior Construction: Use these constraints to construct the MKDIP prior by solving a constrained optimization problem that maximizes entropy (or another information-theoretic criterion) subject to your knowledge-based constraints [34].

- Classifier Design: Use this informed prior to design an Optimal Bayesian Classifier (OBC), which is guaranteed to outperform classical methods when dealing with model uncertainty and small sample sizes [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Parameter Estimation Accuracy in Models with Unmeasured Variables

It is often difficult to estimate kinetic parameters when you lack time-series data for all molecular species in the model [32].

Step 1: Repeat the Optimization

- Unless computationally prohibitive, repeat the optimization with different initial values to check for consistency in the results [32].

Step 2: Apply Differential Elimination

- Use differential algebra to rewrite your system of differential equations into an equivalent set of equations. This process eliminates the unmeasured variables and reveals implicit relationships between the parameters and the measured variables [32].

Step 3: Introduce DE Constraints into the Objective Function

- Modify your standard objective function (e.g., sum of squared errors) to include the new constraints derived from differential elimination.

- A common approach is to use a weighted sum:

New Objective = (Total Relative Error) + α * (DE Constraint Value), whereαis a weighting factor [32].

Step 4: Re-run Parameter Estimation

- Optimize the new objective function using your preferred method (e.g., Genetic Algorithm, Particle Swarm Optimization). The DE constraints will guide the optimization toward more accurate and biologically feasible parameter sets [32].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this troubleshooting process:

Problem: Model Predictions are Inconsistent with Established Biological Knowledge

A model that fits data well but violates known biological principles lacks explanatory power and may have poor predictive value.

Step 1: Check for Appropriate Controls

- Ensure your model and data have proper controls. A negative result could mean a problem with the protocol or that the biological effect is genuinely absent [35].

Step 2: Use Knowledge as a Filter or Integrator

- Filter: Use prior knowledge to cull impossible or highly improbable model outcomes or parameter ranges from consideration. This directly reduces false discovery rates [36].

- Integrator: Aggregate weak signals from multiple, functionally related entities (e.g., genes in a pathway) into a stronger, combined signal. This increases statistical power and ensures consistency with known modules [36].

Step 3: Formulate Knowledge as Soft Constraints in the Objective Function

- When building a machine learning model, incorporate biological knowledge as "soft constraints" during the optimization of the objective function. This technique improves the model's robustness, predictive power, and interpretability by ensuring it aligns with known mechanisms [37].

Step 4: Prune the Model

- Apply concepts like the "lottery ticket hypothesis" to prune large, complex models (e.g., neural networks). This process reduces complexity, often improves predictive performance, and can reveal a core set of predictors that are consistent with biological understanding [37].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key software tools and algorithms that function as essential "reagents" for implementing constraint-based methods in systems biology.

| Tool / Algorithm | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| CICO Algorithm [33] | Estimates practical identifiability and accurate confidence intervals for model parameters via profile likelihood and constrained optimization. | Determining which parameters in a systems biology model can be reliably estimated from available data. |

| Differential Elimination [32] | Algebraically rewrites a system of ODEs to eliminate unmeasured variables and derive parameter constraints. | Improving parameter estimation accuracy in models where not all species can be experimentally measured. |

| MKDIP Prior [34] | Constructs an informative prior probability distribution from biological pathway knowledge for Bayesian analysis. | Incorporating existing knowledge of gene regulatory networks or signaling pathways into classifier design, especially with small datasets. |

| Optimal Bayesian Classifier (OBC) [34] | A classifier that minimizes the expected error by treating uncertainty directly on the feature-label distribution, often using an MKDIP prior. | Building predictive models for phenotypes (e.g., disease states) that fully utilize prior biological knowledge. |

Advanced Computational Strategies for Robust Parameter Inference

Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) represent a powerful hybrid modeling framework that integrates partially known mechanistic models with data-driven artificial neural networks (ANNs) [1]. This approach is particularly valuable in systems biology, where mechanistic models are often based on established biological knowledge but may have gaps or missing processes [1]. UDEs address the fundamental challenge of identifying model structures that can accurately recapitulate process dynamics solely based on experimental measurements [1].

The UDE framework enables researchers to leverage prior knowledge through mechanistic components while using ANNs to learn unknown dynamics directly from data [1]. This balances interpretability with predictive accuracy, making UDEs especially suitable for biological applications where datasets are often limited and interpretability is crucial for decision-making, particularly in medical applications [1]. By embedding flexible function approximators within structured dynamical systems, UDEs enable models that are simultaneously data-adaptive and theory-constrained [38].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Fundamental Concepts

What are Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) and how do they differ from purely mechanistic or data-driven models?

Universal Differential Equations (UDEs) are differential equations that combine mechanistic terms with data-driven components, typically artificial neural networks [1]. Unlike purely mechanistic models that rely exclusively on prior knowledge, or completely black-box models like standard neural differential equations, UDEs incorporate both elements in a single framework [38] [1]. This hybrid approach allows researchers to specify known biological mechanisms while using neural networks to approximate unknown or overly complex processes [1]. The resulting models maintain the interpretability of mechanistic modeling where knowledge exists while leveraging the flexibility of machine learning to capture complex, unmodeled dynamics [38].

In what scenarios should I consider using UDEs in systems biology research?

UDEs are particularly valuable in several scenarios: (1) when you have partial mechanistic knowledge of a biological system but certain processes remain poorly characterized; (2) when working with limited datasets that are insufficient for fully data-driven approaches but can constrain a hybrid model; (3) when modeling stiff dynamical systems common in biological processes [1]; and (4) when interpretability of certain model parameters is essential for biological insight [1]. UDEs have been successfully applied to various biological problems including metabolic pathways like glycolysis, where known enzymatic reactions can be combined with learned representations of complex regulatory processes [1].

Implementation and Training

What are the most common challenges when training UDE models, and how can I address them?

Training UDEs presents several domain-specific challenges that require specialized approaches [1]:

Table: Common UDE Training Challenges and Solutions

| Challenge | Description | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Stiff Dynamics | Biological systems often exhibit processes with vastly different timescales [1] | Use specialized numerical solvers (Tsit5, KenCarp4) [1] |

| Measurement Noise | Complex, often non-constant noise distributions in biological data [1] | Implement appropriate error models and maximum likelihood techniques [1] |

| Parameter Scaling | Species abundances and kinetic rates span orders of magnitude [1] | Apply log-transformation to parameters [1] |

| Overfitting | ANN flexibility can capture noise rather than true dynamics [1] | Apply regularization (weight decay) and use early stopping [1] |

How can I improve training stability and convergence for my UDE model?

Implement a multi-start optimization pipeline that samples initial values for both mechanistic parameters (θM) and ANN parameters (θANN) [1]. This approach should include: (1) parameter transformations (log-transformation or tanh-based transformation for bounded parameters) to handle parameters spanning multiple orders of magnitude; (2) input normalization to improve numerical conditioning; (3) regularization (L2 penalty on ANN weights) to prevent overfitting and maintain mechanistic interpretability; and (4) early stopping based on out-of-sample performance [1]. The pipeline should jointly sample hyperparameters including ANN architecture, activation functions, and optimizer learning rates to thoroughly explore the hyperparameter space [1].

Biological Applications

How do I determine which parts of my model should be mechanistic versus learned?

The choice between mechanistic and learned components depends on the certainty of biological knowledge and the complexity of the process. Known biochemical reactions with established kinetics should typically be represented mechanistically, while complex regulatory interactions or poorly characterized cellular processes are good candidates for learned representations [1]. In the glycolysis model example, the core enzymatic steps are represented mechanistically while ATP usage and degradation are handled by the neural network [1]. This division allows the model to leverage established biochemistry while learning the more complex regulatory aspects.

Can UDEs handle the typical experimental constraints in systems biology, such as sparse and noisy data?

Yes, UDEs are particularly valuable for working with realistic biological data constraints, though performance deteriorates with increasing noise levels or decreasing data availability [1]. Regularization becomes increasingly important in these scenarios to maintain accuracy and interpretability [1]. For sparse data, incorporating Bayesian multimodel inference (MMI) can help account for model uncertainty by combining predictions from multiple UDE structures, increasing robustness to data limitations [3]. MMI constructs a consensus estimator that weights predictions from different models based on their evidence or predictive performance [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Training Instability

Problem: Training fails to converge or produces NaNs during optimization.

This commonly occurs with stiff biological systems or poorly scaled parameters [1].

Solution 1: Implement parameter transformations

Solution 2: Switch to specialized ODE solvers

Solution 3: Adjust network architecture and training

- Simplify the neural network architecture (reduce layers or units)

- Apply weight decay regularization (L2 penalty) to stabilize training [1]

- Reduce learning rate or implement learning rate scheduling

Problem: Model overfits to training data and generalizes poorly.

Solution 1: Enhance regularization strategy

Solution 2: Improve training data quality and representation

- Ensure training data adequately covers the dynamic range of interest

- Incorporate Bayesian multimodel inference to account for structural uncertainty [3]

- Use data augmentation techniques to artificially expand training dataset

Interpretation Difficulties

Problem: Mechanistic parameters become biologically implausible after training.

Solution 1: Apply constraints to mechanistic parameters

Solution 2: Balance mechanistic and neural components

- Adjust regularization strength to prevent ANN from overshadowing mechanistic terms [1]

- Gradually increase model complexity, starting with simpler ANN architectures

- Implement sensitivity analysis to identify parameters with high uncertainty

Experimental Protocols

UDE Development Workflow for Biological Systems

The following diagram illustrates the complete UDE development pipeline for systems biology applications:

Multi-Start Optimization Protocol

For reliable UDE training, implement this detailed multi-start optimization protocol:

Parameter Space Definition

- Define plausible ranges for mechanistic parameters based on biological knowledge

- Specify neural network architecture search space (layer sizes, activation functions)

- Set learning rate ranges (typically 1e-4 to 1e-2) and regularization strengths

Initialization Strategy

- Sample mechanistic parameters from log-uniform distributions across their plausible ranges

- Initialize neural network weights using standard strategies (Xavier/Glorot)

- For each optimization run, independently sample hyperparameters and initial values [1]

Optimization Execution

- Run multiple independent optimizations (typically 50-100 runs)

- Use a combination of gradient-based optimizers (Adam followed by L-BFGS)

- Implement early stopping when validation loss fails to improve for specified iterations

Result Consolidation

- Select top-performing models based on validation loss

- Assess consistency of mechanistic parameters across top runs

- Apply Bayesian multimodel inference if multiple model structures are viable [3]

UDE Training Protocol for Glycolysis Modeling

This protocol adapts the glycolysis modeling case study from the literature [1]:

Data Preparation

- Collect time-course measurements of metabolic intermediates (glucose, G6P, F6P, etc.)

- Normalize measurements to account for concentration scale differences

- Split data into training (70%), validation (15%), and test (15%) sets

Model Specification

- Implement known enzymatic steps of glycolysis using Michaelis-Menten kinetics

- Replace poorly characterized ATP usage and degradation terms with neural network

- Use a feedforward network with 3 hidden layers (5-10 units each) and radial basis activation

Training Configuration

- Apply log-transformation to kinetic parameters

- Use KenCarp4 solver for stiff dynamics with relative tolerance 1e-6

- Implement weight decay regularization (λ = 0.001) on neural network parameters

Validation Assessment

- Check predictive performance on test set

- Verify biological plausibility of kinetic parameters

- Assess whether neural network has learned biologically interpretable dependencies

Performance Data

UDE Performance Under Different Data Conditions

Table: UDE Performance with Varying Data Quality and Quantity

| Data Scenario | Noise Level | Data Points | Parameter RMSE | State Prediction RMSE | Recommended Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Quality | Low (1-5% CV) | Dense (>50 points) | 0.05-0.15 | 0.02-0.08 | Standard UDE with moderate regularization |

| Moderate Quality | Medium (10-20% CV) | Sparse (15-30 points) | 0.15-0.30 | 0.08-0.15 | Strong regularization + multi-start |

| Low Quality | High (>25% CV) | Very sparse (<15 points) | 0.30-0.50 | 0.15-0.25 | Bayesian MMI + strong constraints |

Regularization Impact on UDE Performance

Table: Effect of Regularization on UDE Training and Interpretability

| Regularization Strength | Mechanistic Parameter Accuracy | ANN Dominance | Training Stability | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (λ = 0) | Low | High | Poor | Not recommended |

| Low (λ = 1e-4) | Medium | Medium | Moderate | High-quality, dense data |

| Medium (λ = 1e-3) | High | Low | Good | Typical biological data |

| High (λ = 1e-2) | High | Very Low | Excellent | Very noisy or sparse data |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Computational Tools for UDE Development

Table: Key Software Tools and Libraries for UDE Implementation

| Tool/Library | Purpose | Key Features | Application in UDE Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| SciML Ecosystem (Julia) | Numerical solving and machine learning | Specialized solvers for stiff ODEs, adjoint sensitivity methods [39] [1] | Core infrastructure for UDE implementation and training |

| OrdinaryDiffEq.jl | Differential equation solving | Stiff-aware solvers (Tsit5, KenCarp4) [39] [1] | Numerical integration of UDE systems |

| SciMLSensitivity.jl | Gradient calculation | Adjoint methods for ODE-constrained optimization [39] | Efficient gradient computation for training |

| Optimization.jl | Parameter estimation | Unified interface for optimization algorithms [39] | Finding optimal parameters for UDEs |

| Lux.jl/Flux.jl | Neural network implementation | Differentiable network components [39] | Creating learnable components of UDEs |

| ModelingToolkit.jl | Symbolic modeling | Symbolic transformations and simplifications [39] | Defining mechanistic components of UDEs |

| DataDrivenDiffEq.jl | Symbolic regression | Sparse identification of model structures [39] | Extracting interpretable equations from trained UDEs |

Advanced Methodologies

Bayesian Multimodel Inference with UDEs

For cases where multiple UDE structures are plausible, implement Bayesian Multimodel Inference (MMI) to account for structural uncertainty [3]:

The MMI workflow combines predictions from multiple UDE structures using:

- Bayesian Model Averaging (BMA): Weights based on model evidence [3]

- Pseudo-BMA: Weights based on expected predictive performance [3]

- Stacking: Direct optimization of weights for predictive performance [3]

This approach increases prediction certainty and robustness when dealing with structural uncertainty in biological models [3].

Global optimization algorithms are indispensable in systems biology for tackling the high-dimensional, nonlinear, and often non-convex parameter estimation problems inherent in modeling biological networks. When calibrating models to experimental data, such as time-course measurements of signaling species, researchers frequently encounter complex objective functions with multiple local minima. This technical support document provides a focused guide on three prominent global optimization strategies—Multi-start, Genetic Algorithms, and Scatter Search (conceptually related to modern surrogate-based methods)—framed within the context of optimizing parameters for systems biology models. You will find detailed troubleshooting guides, frequently asked questions (FAQs), and standardized protocols to address common challenges encountered during computational experiments.

Algorithm Deep Dive and Comparative Analysis

Multi-start Optimization

Overview and Workflow: Multi-start optimization is a meta-strategy designed to increase the probability of finding a global optimum by launching multiple local optimization runs from different initial points in the parameter space [40] [41]. It is particularly valuable when the objective function is suspected to be multimodal. In systems biology, this is crucial for robustly estimating kinetic parameters in ordinary differential equation (ODE) models of signaling pathways [42].

The workflow, inspired by the TikTak algorithm, follows these key steps [40] [41]:

- Exploration Sampling: A large sample of parameter vectors is drawn using a low-discrepancy sequence (e.g., Sobol) or randomly within user-specified finite bounds [40] [41].

- Parallel Evaluation: The objective function is evaluated in parallel for all parameter vectors in the initial sample [40].

- Sorting and Local Optimization: The parameter vectors are sorted from best to worst. Local optimizations are then initiated iteratively. The first run starts from the best sample point. Subsequent runs start from a convex combination of the current best-known parameter vector and the next promising sample point [40] [41].

- Convergence: The process stops when a specified number of local optimizations (

convergence_max_discoveries) converge to the same point, or when a maximum number of optimizations is reached [40].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow of a Multi-start optimization:

Key "Research Reagent Solutions" (Software & Configuration):

| Item | Function in Multi-start Optimization |

|---|---|

| Finite Parameter Bounds | Essential for defining the search space from which initial samples are drawn [40]. |

| Low-Discrepancy Sequences (Sobol, Halton) | Generate a space-filling exploration sample for better coverage of the parameter space than random sampling [41]. |

| Local Optimization Algorithm (e.g., L-BFGS-B, Nelder-Mead) | The "workhorse" algorithm used for each local search from a starting point [40]. |

Parallel Computing Cores (n_cores) |

Significantly speeds up the initial exploration phase and multiple local searches [40] [41]. |

Genetic Algorithms (GAs)

Overview and Workflow: Genetic Algorithms are population-based metaheuristics inspired by the process of natural selection [43]. They are gradient-free and particularly effective for problems where derivative information is unavailable or the objective function is noisy. GAs have been successfully applied to problems like hyperparameter optimization and, relevantly, parameter estimation in S-system models of biological networks [44] [45].

The algorithm proceeds through the following biologically inspired steps [44] [43]:

- Initialization: A population of candidate solutions (individuals) is generated, often randomly.

- Evaluation: Each candidate's fitness is evaluated using the objective function.

- Selection: Individuals are selected to become parents based on their fitness, with better solutions having a higher chance of being selected.

- Crossover (Reproduction): Pairs of parents are combined to create offspring, inheriting "genetic material" from both.

- Mutation: A random subset of offspring undergoes small random changes to introduce genetic diversity and explore new areas of the search space.

- Termination: Steps 2-5 are repeated for multiple generations until a termination condition (e.g., max generations, fitness plateau) is met [43].

The iterative process of a Genetic Algorithm is visualized below:

Key "Research Reagent Solutions" (Algorithm Components):

| Item | Function in Genetic Algorithms |

|---|---|

| Fitness Function | The objective function that quantifies the quality of a candidate solution [43]. |

| Population | The set of all candidate solutions being evolved in a generation [43]. |

| Selection Operator | The mechanism (e.g., tournament, roulette wheel) for choosing parents based on fitness [44]. |

| Crossover Operator | The method (e.g., single-point, blend) for recombining two parents to form offspring [43]. |

| Mutation Operator | A random perturbation applied to an offspring's parameters to maintain diversity [44] [43]. |

Scatter Search and Surrogate-Based Global Optimization

Overview and Workflow: While classic Scatter Search was not explicitly detailed in the search results, the principles of maintaining a diverse set of solutions and combining them are central to modern Surrogate-Based Global Optimization (SBGO) [46]. SBGO is an efficient strategy for problems where the objective function is computationally very expensive to evaluate, such as running a complex simulation of a biological network. The core idea is to replace the expensive "black-box" function with a cheaper-to-evaluate approximation model, known as a surrogate or metamodel [46].

The typical SBGO workflow involves [46]:

- Design of Experiments (DoE): Select an initial set of sample points in the parameter space (e.g., via Latin Hypercube Sampling).

- Surrogate Modeling: Evaluate the true expensive function at these points and use the data to build an initial surrogate model (e.g., Radial Basis Functions (RBF), Kriging).

- Infill and Iteration: Use an infill criterion (e.g., Expected Improvement) to select the most promising new point(s) for evaluation with the true function. The surrogate model is updated with each new data point.

- Termination: The process repeats until a computational budget is exhausted or convergence is achieved.

Key "Research Reagent Solutions" (SBGO Components):

| Item | Function in Surrogate-Based Optimization |

|---|---|

| Design of Experiments (DoE) | Strategy for selecting initial sample points to build the first surrogate model [46]. |

| Surrogate Model (e.g., RBF, Kriging) | A fast, approximate model of the expensive objective function [46]. |

| Infill Criterion | The strategy (balancing exploration vs. exploitation) for selecting new points to evaluate [46]. |

Algorithm Comparison Table

The choice of algorithm depends heavily on the problem characteristics and computational constraints. The table below provides a structured comparison based on the gathered information.

Table: Comparative Analysis of Global Optimization Algorithms

| Feature | Multi-start [40] [42] [41] | Genetic Algorithms (GAs) [44] [43] [45] | Scatter Search / Surrogate-Based [46] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Multiple local searches from strategically chosen start points. | Population evolution via selection, crossover, and mutation. | Iterative refinement using an approximate surrogate model. |

| Problem Scalability | Good for medium-scale problems; efficacy can diminish in very high dimensions (>100 variables) [47]. | Can struggle with high-dimensionality due to exponential growth of the search space [43]. | Designed for expensive problems, but model construction can become costly in high dimensions. |

| Handling of Expensive Functions | Moderate. Parallelization reduces wall-clock time, but total function evaluations can be high [40]. | Can be high due to the large number of function evaluations required per generation [43]. | Excellent. The primary use case is to minimize calls to the expensive true function [46]. |

| Typical Applications in Systems Biology | Point estimation of parameters in ODE models; uncertainty quantification via sampling [42]. | Parameter estimation for non-differentiable or complex model structures (e.g., S-systems) [45]. | Optimization of models relying on slow, high-fidelity simulations (e.g., CFD in biomedical device design) [46]. |

| Key Strength | Conceptual simplicity, ease of implementation, and strong parallel scaling. | Gradient-free; good for non-smooth, discontinuous, or discrete spaces. | High sample efficiency for very expensive black-box functions. |

| Primary Limitation | No guarantee of finding a global optimum; performance depends on the quality of the local optimizer [40]. | Requires careful tuning of parameters (mutation rate, etc.); can converge prematurely [43]. | Overhead of building and updating the surrogate; performance depends on model choice and infill criterion. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Multi-start Optimization

Q1: My multi-start optimization runs for too long. How can I make it more efficient?

- A: This is a common issue. Implement the following checks:

- Limit Local Evaluations: Set a strict limit on the number of function evaluations or iterations for each local optimization (

stopping_maxfun). This prevents a single bad start point from consuming excessive time [40]. - Use Efficient Sampling: Prefer low-discrepancy sequences (e.g.,

sampling_method="sobol") over pure random sampling for the exploration phase, as they provide better space-filling properties with fewer samples [41]. - Leverage Parallelization: Configure the

n_coresoption to run the exploration and local optimizations in parallel, drastically reducing wall-clock time [40] [41]. - Tighten Convergence: Reduce the

n_samplesor lower theconvergence.max_discoveriesthreshold to stop the process after fewer successful rediscoveries of the same optimum [40] [41].

- Limit Local Evaluations: Set a strict limit on the number of function evaluations or iterations for each local optimization (

Q2: The algorithm stops after just a few optimizations and I'm not confident in the result.

- A: This occurs when the

convergence_max_discoveriescondition is met too quickly.- Force More Runs: Explicitly set the

stopping_maxoptoption to run a specific number of local optimizations. Ensureconvergence_max_discoveriesis set to a value at least as large asstopping_maxoptto prevent early stopping [40]. - Check Parameter Tolerance: Increase the

convergence.relative_params_toleranceto make the criterion for declaring two solutions "the same" more stringent [41]. - Review Bounds: Ensure your parameter bounds are not overly restrictive, artificially forcing different starts to converge to the same boundary point.

- Force More Runs: Explicitly set the

Q3: I don't have strict bounds for all my parameters. Can I still use multi-start?

- A: Yes. Use "soft bounds" which are only used to draw the initial exploration sample and do not constrain the local optimizations. This allows the local solver to explore outside these bounds if necessary [40] [41].

Genetic Algorithms

Q1: My GA converges to a sub-optimal solution too quickly (premature convergence).

- A:

- Increase Mutation Rate: Temporarily increase the mutation probability to reintroduce genetic diversity and help the population escape local optima [43].

- Review Selection Pressure: If your selection operator is too greedy (always picking the very best), it can reduce diversity. Consider using less aggressive selection strategies.

- Use Elitism: Ensure you are using elitism to preserve the best solution(s) from each generation, preventing loss of good solutions from a highly disruptive mutation [43].

- Check Population Diversity: Monitor the diversity of your population. If it collapses, you may need to increase the population size or implement diversity-preserving mechanisms like "speciation" [43].

Q2: The optimization is very slow, and each generation takes a long time.

- A:

- Vectorize Evaluations: If possible, vectorize the fitness function evaluation to process the entire population at once, rather than in a loop.

- Use Parallel Evaluation: Evaluate the fitness of individuals in the population in parallel across multiple CPU cores [44].

- Simplify the Model/Function: For initial testing and tuning, run the GA on a simplified version of your model to speed up iteration.

- Surrogate-Assisted GA: For extremely expensive functions, consider using a surrogate model (e.g., RBF network) to approximate the fitness of most individuals, only using the true function for the most promising candidates [46].

General Optimization Issues

Q1: How do I know if I've found the global optimum and not just a good local one?

- A: There is no absolute guarantee, but you can increase your confidence.

- Multiple Runs: Run any global optimizer multiple times with different random seeds. Convergence to the same or a very similar objective function value from diverse starting points is a good indicator [40] [42].

- Multimodel Inference: In systems biology, consider using Bayesian multimodel inference (MMI). This technique averages predictions from multiple models that fit the data well, which can be more robust than relying on parameters from a single "best" optimization run [3].

- Visualization: Tools like

optimagiccan generate criterion plots showing the history of all local optimizations, allowing you to see if multiple starts converged to the same basin [40].

Q2: For large-scale models (hundreds of parameters), which algorithm is most suitable?

- A: The scale of the problem is a significant challenge.

- Caution with Global Methods: Studies have shown that particle swarm optimization (a global method) can be outperformed by gradient-based algorithms like Levenberg-Marquardt for large-scale (e.g., 660 variables) biomechanical optimization problems, as the solution might lie in a narrow "channel" in design space that is hard to find without gradient information [47].