Phylogenetic Tree Construction Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern phylogenetic tree construction methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Phylogenetic Tree Construction Methods: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern phylogenetic tree construction methods, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, from tree components to the essential steps of sequence alignment and model selection. The guide delves into the mechanics, pros, and cons of major methodologies—distance-based, maximum parsimony, maximum likelihood, and Bayesian inference—with a focus on their specific applications in biomedical research, including drug target identification and pathogen evolution tracking. Furthermore, it addresses critical challenges like compositional heterogeneity and long-branch attraction, and outlines best practices for tree validation and method selection to ensure robust, reproducible results in scientific and clinical contexts.

The Blueprint of Life: Understanding Phylogenetic Trees and Core Concepts

What is a Phylogenetic Tree? Defining Nodes, Branches, and Clades

A phylogenetic tree, also known as a phylogeny or evolutionary tree, is a branching diagram that represents the evolutionary history and relationships between a set of species, genes, or other taxonomic entities [1]. These trees illustrate how biological entities have diverged from common ancestors over time, forming a foundational element of modern evolutionary biology, systematics, and comparative genomics [2] [1]. The core principle underlying phylogenetic trees is that all life on Earth shares common ancestry, and thus can theoretically be represented within a single, comprehensive tree of life [1].

Phylogenetic trees serve as critical tools across multiple biological disciplines. In evolutionary biology, they help examine speciation processes; in epidemiology, they classify virus families; in host-pathogen studies, they demonstrate co-speciation patterns; and in cancer research, they explore genetic changes during disease progression [3]. The ability to correctly interpret and construct phylogenetic trees has become essential for researchers studying molecular evolution, population genetics, and drug development, where understanding evolutionary relationships can inform target identification and therapeutic design [2] [4].

Core Components of a Phylogenetic Tree

Understanding the terminology and components of phylogenetic trees is essential for their proper interpretation and construction. The table below defines the fundamental elements.

Table 1: Core Components of a Phylogenetic Tree

| Component | Description | Biological Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Nodes | Points where branches diverge, representing taxonomic units [2] [1]. | Indicate evolutionary events such as speciation or gene duplication. |

| Root Node | The most recent common ancestor of all entities in the tree [1]. | Provides directionality to evolution and establishes the starting point of the divergence process. |

| Internal Nodes | Hypothetical taxonomic units (HTUs) representing inferred ancestors [2] [1]. | Represent unsampled or extinct ancestral populations or species. |

| External Nodes (Tips/Leaves) | Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) representing the sampled species, sequences, or individuals [2]. | Correspond to real biological entities from which data were collected. |

| Branches | Lines connecting nodes, representing evolutionary lineages [2] [1]. | Depict the evolutionary path between ancestral and descendant nodes. |

| Branch Lengths | Often proportional to the amount of evolutionary change or time [1] [5]. | Provide a timescale for evolutionary divergence when calibrated. |

| Clades | Groups consisting of a node and all lineages descending from it [2]. | Represent monophyletic groups—all descendants of a common ancestor. |

Tree Types and Representations

Phylogenetic trees can be categorized based on their structural properties and the information they convey:

- Rooted vs. Unrooted Trees: Rooted trees contain a root node representing the most recent common ancestor, providing evolutionary directionality [1]. Unrooted trees only illustrate relatedness among leaf nodes without specifying ancestry [1]. Unrooted trees can be converted to rooted trees by including an outgroup or applying the molecular clock hypothesis [1].

- Bifurcating vs. Multifurcating Trees: Bifurcating trees have exactly two descendants at each internal node, forming binary trees [1]. Multifurcating trees may have more than two children at some nodes, representing unresolved evolutionary relationships [1].

- Labeled vs. Unlabeled Trees: Labeled trees have specific values assigned to their leaves, while unlabeled trees define topology only [1].

Table 2: Common Phylogenetic Tree Types and Their Characteristics

| Tree Type | Branch Lengths | Representation | Common Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cladogram | Not proportional to evolutionary change; only represents branching pattern [1] [5]. | Topology without scale | Hypothesis of relationships without evolutionary rate information. |

| Phylogram | Proportional to amount of character change [1] [5]. | Scaled branches show evolutionary change | Comparing relative rates of evolution across lineages. |

| Chronogram | Proportional to time [1]. | Scaled branches show temporal divergence | Dating evolutionary events when fossil calibrations available. |

| Dendrogram | General term for any tree-like diagram [1]. | Varies | Cluster analysis results in various biological fields. |

Phylogenetic Tree Construction Methods

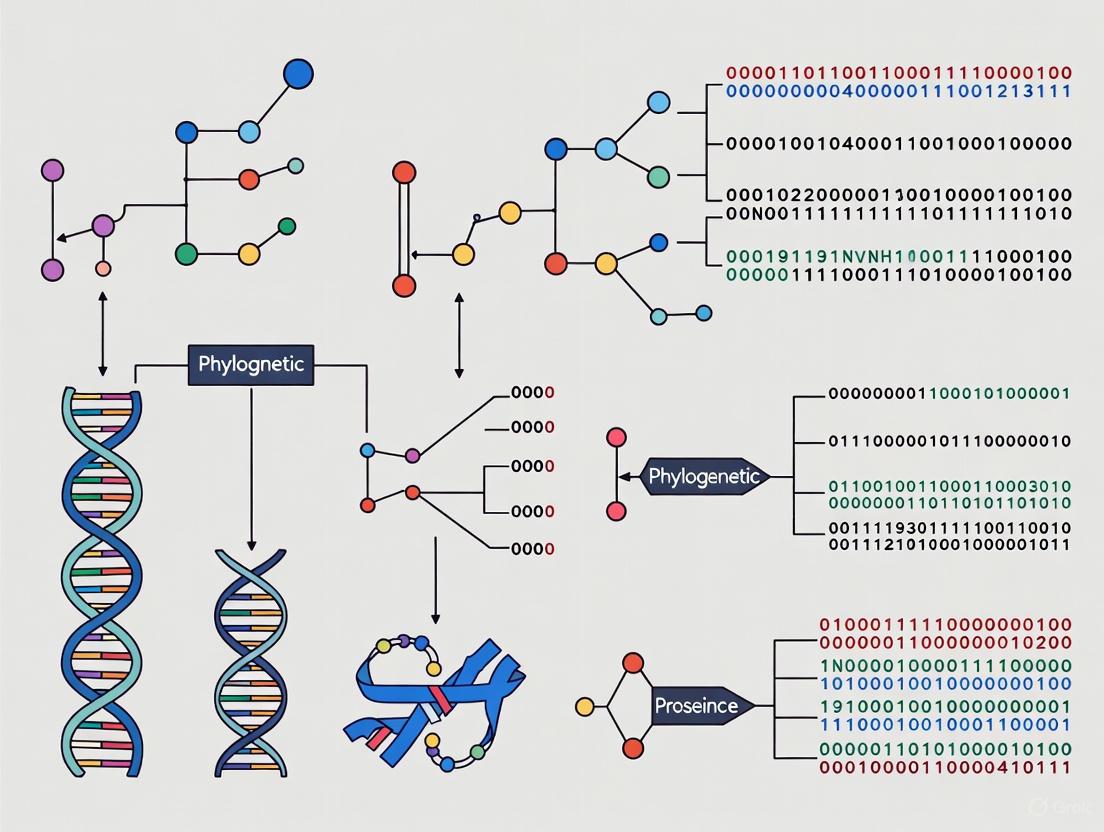

The construction of phylogenetic trees typically follows a multi-step process beginning with sequence collection and progressing through alignment, model selection, tree inference, and evaluation [2]. The general workflow and relationships between different construction methods are visualized below.

Phylogenetic Tree Construction Workflow

Distance-Based Methods

Distance-based methods represent the simplest approach to tree construction, transforming molecular feature matrices into distance matrices that represent evolutionary distances between species [2]. The Neighbor-Joining (NJ) algorithm is the most prominent example, created by Saitou and Nei in 1987 [2]. NJ is an agglomerative clustering method that constructs trees by successively merging pairs of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) that minimize the total tree length [2]. The algorithm begins with a star-like tree and iteratively finds the pair of nodes that minimizes the total branch length, updating the distance matrix after each merge until a fully resolved tree is obtained [2].

Protocol: Neighbor-Joining Tree Construction

- Calculate Distance Matrix: Compute pairwise distances between all sequences using an appropriate evolutionary model (e.g., Jukes-Cantor, Kimura 2-parameter) [2].

- Initialize Star Tree: Begin with a star-like phylogeny connecting all sequences to a central node [2].

- Identify Neighbor Pair: Calculate the Q-matrix and identify the pair of taxa (i, j) that minimizes the branch length.

- Create New Node: Create a new internal node X that connects the selected pair.

- Update Distance Matrix: Calculate distances from the new node X to all other taxa.

- Iterate: Repeat steps 3-5 until all nodes are connected, resulting in a fully resolved tree.

- Calculate Branch Lengths: Compute final branch lengths based on the estimated distances.

The NJ method offers computational efficiency and statistical consistency under the Balanced Minimum Evolution (BME) model [2]. Its stepwise construction approach avoids exhaustive searches through tree space, making it particularly suitable for analyzing large datasets where the number of possible trees grows exponentially with taxon number [2]. However, converting sequence data to distances necessarily reduces information content, potentially limiting accuracy when sequence divergence is substantial [2].

Character-Based Methods

Character-based methods utilize the complete sequence alignment rather than reducing data to pairwise distances, potentially preserving more phylogenetic information [2]. These methods generate numerous hypothetical trees and select optimal trees according to specific criteria [2].

Maximum Parsimony (MP)

Maximum Parsimony operates on the principle of Occam's razor, seeking the tree that requires the fewest evolutionary changes to explain the observed data [2]. The method was developed by Farris and Fitch in the early 1970s and focuses on informative sites—positions in the alignment with at least two different character states, each present in at least two sequences [2].

Protocol: Maximum Parsimony Analysis

- Identify Informative Sites: Scan the aligned sequences to locate parsimony-informative sites [2].

- Generate Tree Space: Create all possible tree topologies for the dataset [2].

- Map Characters: For each topology, map character state changes across the tree [2].

- Calculate Tree Length: Count the total number of character state changes required [2].

- Select Optimal Tree(s): Identify the tree(s) with the minimum number of changes [2].

- Build Consensus Tree: If multiple equally parsimonious trees exist, create a consensus tree [2].

For datasets with many taxa, exact solutions become computationally infeasible due to the exponential growth of tree space. Heuristic search methods like Subtree Pruning and Regrafting (SPR) and Nearest Neighbor Interchange (NNI) are employed to efficiently explore tree space [2]. While MP has the advantage of not requiring explicit evolutionary models, it can produce multiple equally parsimonious trees and may perform poorly when evolutionary rates vary significantly across lineages [2].

Maximum Likelihood (ML) and Bayesian Inference (BI)

Maximum Likelihood methods, introduced by Felsenstein in the 1980s, evaluate trees based on their probability of producing the observed data under an explicit evolutionary model [2]. ML searches for the tree topology and branch lengths that maximize the likelihood function, which calculates the probability of the sequence data given the tree and model of evolution [2].

Bayesian Inference extends the likelihood framework using Bayes' theorem to estimate the posterior probability of trees, incorporating prior knowledge about parameters [2]. BI uses Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling to approximate the posterior distribution of trees, providing direct probabilistic support for phylogenetic hypotheses [2].

Protocol: Maximum Likelihood Analysis

- Select Evolutionary Model: Choose an appropriate nucleotide or amino acid substitution model (e.g., GTR, JTT) using model-testing procedures [2].

- Generate Initial Tree: Create a starting tree, often using a fast method like NJ [2].

- Optimize Branch Lengths: Calculate branch lengths that maximize the likelihood for the current topology [2].

- Evaluate Topologies: Propose topological changes and assess their impact on likelihood [2].

- Iterate: Continue proposing and evaluating topological changes until likelihood converges [2].

- Assess Support: Perform bootstrap analysis to evaluate clade confidence [2].

Table 3: Comparison of Phylogenetic Tree Construction Methods

| Method | Principle | Optimality Criterion | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighbor-Joining | Minimal evolution | Branch length estimation | Fast computation; suitable for large datasets [2]. | Information loss from distance calculation [2]. |

| Maximum Parsimony | Minimize evolutionary steps | Fewest character state changes [2]. | No explicit model required; intuitive principle [2]. | Can be inconsistent with rate variation; multiple optimal trees [2]. |

| Maximum Likelihood | Maximize probability of data | Highest likelihood score [2]. | Statistical framework; model-based; handles complex models [2]. | Computationally intensive; model misspecification risk [2]. |

| Bayesian Inference | Bayes' theorem | Highest posterior probability [2]. | Incorporates prior knowledge; provides clade probabilities [2]. | Computationally intensive; prior specification affects results [2]. |

Visualization and Annotation of Phylogenetic Trees

Effective visualization is essential for interpreting phylogenetic trees, particularly as trees grow in size and complexity [6] [5]. The ggtree package in R has emerged as a powerful tool for phylogenetic tree visualization and annotation, implementing a grammar of graphics approach to tree plotting [6] [7].

Tree Layouts and Visualizations

Phylogenetic trees can be visualized using multiple layouts, each with distinct advantages for highlighting particular aspects of evolutionary relationships:

- Rectangular Layout: The standard tree visualization with horizontal branches and vertical divisions [6] [7].

- Circular Layout: Uses space efficiently to display larger trees with the root at the center [6] [7].

- Slanted Layout: Similar to rectangular but with slanted connecting branches [6] [7].

- Unrooted Layout: Displays relationships without assuming ancestry using equal-angle or daylight algorithms [6] [7].

- Fan Layout: Circular layout with adjustable opening angle [6] [7].

Tree Visualization and Annotation Process

Annotation Protocols

ggtree enables layered annotation of phylogenetic trees, allowing researchers to integrate diverse data types including evolutionary rates, ancestral sequences, geographic information, and statistical analyses [6] [7]. The package supports numerous geometric layers for annotation:

geom_tiplab(): Adds taxon labels at tree tips [6] [7].geom_nodepoint()andgeom_tippoint(): Adds symbols to internal nodes and tips [6] [7].geom_hilight(): Highlights selected clades with colored rectangles [6] [7].geom_cladelab(): Annotates clades with bar and text labels [6] [7].geom_treescale(): Adds scale bars for branch length interpretation [6] [7].

Protocol: Basic Tree Visualization with ggtree

- Import Tree Data: Parse tree files (Newick, NEXUS, etc.) into R using treeio [6] [7].

- Create Base Tree Plot: Generate the initial tree visualization using

ggtree(tree_object)[6] [7]. - Customize Appearance: Modify tree aesthetics (color, size, linetype) using ggplot2 syntax [6] [7].

- Add Annotation Layers: Incorporate relevant data using

+ geom_layer()syntax [6] [7]. - Adjust Layout: Select appropriate layout (rectangular, circular, etc.) for the research question [6] [7].

- Export Visualization: Save the final tree figure in appropriate formats for publication.

Advanced annotation techniques include mapping tree covariates to visual properties (coloring branches by evolutionary rate), collapsing or rotating clades for emphasis, and integrating associated data from diverse sources [7]. The compatibility of ggtree with various phylogenetic data objects (phylo4, obkData, phyloseq) facilitates reproducible analysis pipelines combining tree construction, analysis, and visualization [6] [7].

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Phylogenetic Analysis

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Tree Visualization Software | ggtree [6] [7], FigTree, iTOL [6] | Visualize, annotate, and export publication-quality trees. |

| Tree Construction Packages | ape, phangorn, phytools [6] | Implement distance-based and character-based tree inference methods. |

| Sequence Alignment Tools | ClustalW, MAFFT, MUSCLE | Generate multiple sequence alignments from raw molecular data. |

| Evolutionary Models | JC69, K80, HKY85, GTR [2] | Model nucleotide substitution patterns for likelihood methods. |

| File Formats | Newick, NEXUS, phyloXML [5] [3] | Standardized formats for storing and exchanging tree data. |

| Data Integration Tools | treedata.table [8], treeio [6] [7] | Match and sync phylogenetic trees with associated data. |

Future Directions and Emerging Approaches

The field of phylogenetic tree construction continues to evolve with computational advances and new biological applications. Machine learning and deep learning approaches are emerging as promising alternatives or enhancements to traditional phylogenetic methods across the entire analysis pipeline [9]. These approaches show potential for multiple sequence alignment, model selection, and direct tree inference, sometimes bypassing traditional alignment steps entirely through embedding techniques or end-to-end learning [9].

As sequencing technologies advance and datasets grow, scalable phylogenetic methods become increasingly important [4]. Microbiome research exemplifies this challenge, where tools for constructing phylogenetic trees from 16S rRNA data are well-established, but robust methods for metagenomic and whole-genome shotgun sequencing data remain less developed [4]. This represents a significant opportunity for methodological innovation to make phylogenetic analysis more accessible to researchers integrating trees into statistical models or machine learning pipelines [4].

Interactive tree visualization represents another frontier, with tools like PhyloPen exploring novel pen and touch interfaces for more intuitive tree navigation and annotation [3]. Such interfaces allow direct manipulation of tree layouts, clade rotation, and real-time annotation, potentially transforming how researchers interact with and interpret phylogenetic hypotheses [3]. As biological datasets continue to expand in both size and complexity, the development of efficient, user-friendly phylogenetic tools will remain essential for advancing evolutionary research and its applications across biological disciplines.

Phylogenetic trees are diagrammatic representations that model the evolutionary relationships and history among biological entities such as species, populations, or genes. These relationships are inferred from various data sources, including genetic sequences, physical characteristics, or biochemical pathways [10] [11]. The tree structure consists of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) representing the sampled data at the tips (leaves), connected by branches to hypothetical taxonomic units (HTUs) at internal nodes, which represent inferred common ancestors [11]. The branching patterns illustrate the paths of evolutionary descent, and the entire structure is underpinned by the fundamental assumption that all life shares a common origin, diverging through evolutionary time [10].

A critical distinction in this field is between rooted and unrooted trees. A rooted tree possesses a single, unique root node that signifies the most recent common ancestor of all entities represented in the tree. This root establishes a direction for evolution and provides a timeline for evolutionary events, allowing for the interpretation of ancestral and derived states [12] [10]. In contrast, an unrooted tree illustrates the relational branching structure but lacks a defined root. It shows the relatedness of the taxa without specifying the direction of evolution or the location of the common ancestor [12] [11]. This Application Note explores the conceptual, methodological, and interpretive differences between these two tree types, providing practical guidance for their application in biomedical and evolutionary research.

Conceptual and Quantitative Distinctions

Fundamental Differences and Implications

The choice between a rooted and unrooted tree has profound implications for biological interpretation. In a rooted tree, each node with descendants represents the inferred most recent common ancestor, and the lengths of the branches can often be interpreted as time estimates or measures of evolutionary change from one node to the next [12]. This makes rooted trees essential for studies of evolutionary chronology, ancestral state reconstruction, and understanding the sequence of trait evolution. The root provides a definitive point of reference from which all evolutionary pathways diverge.

Conversely, an unrooted tree depicts only the topological relationships and relative divergence among the taxa. It does not define the evolutionary path or pinpoint the origin [12]. Unrooted trees are often an intermediate step in phylogenetic analysis, as they represent the direct relationships inferred from the data before a root is designated. They are particularly useful for visualizing relationships when no reliable outgroup is available to determine the root position, or when the assumption of a universal common ancestor is not central to the research question.

Table 1: Core Conceptual Differences Between Rooted and Unrooted Trees

| Feature | Rooted Tree | Unrooted Tree |

|---|---|---|

| Root Node | Has a defined root (most recent common ancestor) [11] | No defined root [11] |

| Evolutionary Direction | Explicitly indicates evolutionary pathways and directionality [10] | Only specifies relationships, not evolutionary paths [10] |

| Interpretation of Nodes | Internal nodes represent inferred common ancestors [12] | Internal nodes represent points of divergence without ancestral inference |

| Branch Length Meaning | Can represent time or genetic change from an ancestor [12] | Represents amount of change between nodes |

| Common Use Cases | Studying evolutionary timelines, trait evolution, ancestry | Exploring pure topological relationships, initial data exploration |

Quantitative Complexity of Tree Spaces

The number of possible tree topologies increases super-exponentially with the number of taxa (n). This combinatorial explosion has significant consequences for computational phylogenetics, as searching for the optimal tree among all possibilities becomes intractable for even moderately sized datasets [10]. The number of unrooted trees for n taxa is given by the formula: (2n-5)! / [2n-3 * (n-3)!]. Meanwhile, the number of rooted trees is correspondingly larger, expressed as: (2n-3)! / [2n-2 * (n-2)!] [13]. Notably, the number of unrooted trees for n sequences is equal to the number of rooted trees for n-1 sequences [13].

Table 2: Number of Possible Rooted and Unrooted Trees for n Taxa

| Number of Taxa (n) | Number of Unrooted Trees | Number of Rooted Trees |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 4 | 3 | 15 |

| 5 | 15 | 105 |

| 6 | 105 | 945 |

| 8 | 10,395 | 135,135 |

| 10 | 2,027,025 | 34,459,425 |

| 20 | 2.22 x 1020 | 8.20 x 1021 |

| 50 | 2.84 x 1074 | 2.75 x 1076 |

This vast tree space necessitates the use of sophisticated heuristic search algorithms in methods like maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference, as an exhaustive search is only feasible for datasets with very few taxa [10] [11].

Experimental Protocols for Tree Construction

General Workflow for Phylogenetic Inference

Constructing a reliable phylogenetic tree, whether rooted or unrooted, follows a systematic workflow. The process begins with sequence collection, where homologous DNA, RNA, or protein sequences are gathered from public databases or experimental data. This is followed by multiple sequence alignment using tools like MAFFT or ClustalW to identify corresponding positions across sequences [11]. The aligned sequences must then be trimmed to remove poorly aligned or gapped regions that could introduce noise; this step requires a careful balance to avoid removing genuine phylogenetic signal [11]. Subsequently, a substitution model is selected based on the characteristics of the sequence data, using model-testing programs like jModelTest2 to find the best-fit evolutionary model [14] [11]. Finally, a tree-building algorithm is applied to infer the phylogenetic tree, followed by tree evaluation using statistical measures such as bootstrapping to assess confidence in the inferred nodes [11].

Diagram 1: Phylogenetic Tree Construction Workflow

Protocol 1: Constructing Trees with Distance-Based Methods

Distance-based methods involve a two-step process: first, calculating a matrix of pairwise evolutionary distances from the sequence alignment; second, using a clustering algorithm to build a tree from this matrix [11]. Two common algorithms are UPGMA and Neighbor-Joining.

A. UPGMA (Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Averages) UPGMA operates under the molecular clock assumption, positing a constant rate of evolution across all lineages [10]. The algorithm works as follows:

- Assign each sequence to its own cluster; define a leaf node for each at height zero.

- Calculate all pairwise distances between clusters, where the distance between two clusters is the average distance between all pairs of elements from each cluster.

- Identify the two clusters (i and j) with the smallest distance.

- Merge these two clusters into a new cluster, k.

- Define a new node k with children i and j, and place it at a height of ½ × d(i,j).

- Update the distance matrix by computing distances between the new cluster k and all other clusters using the formula: d(k,l) = [|i| × d(i,l) + |j| × d(j,l)] / (|i| + |j|), where |i| and |j| are the sizes of the original clusters.

- Repeat steps 2-6 until only one cluster remains [10]. UPGMA produces an ultrametric, rooted tree where the distances from the root to all tips are equal. However, its accuracy depends heavily on the validity of the molecular clock assumption, which is often violated in real biological data [10].

B. Neighbor-Joining (NJ) Neighbor-Joining is a minimum-evolution method that does not assume a molecular clock and produces unrooted trees [10] [11]. The algorithm proceeds as follows:

- Begin with a star-like unrooted tree.

- For each tip i, calculate its net divergence (ui) from all other tips: ui = Σ d(i,j) / (N-2), where N is the current number of nodes.

- For all pairs i, j, compute the biased distance score: D(i,j) = d(i,j) - (ui + uj).

- Select the pair (i, j) with the smallest D(i,j) value.

- Create a new node k connecting i and j. Calculate the branch lengths from k to i and k to j:

- d(k,i) = ½ [d(i,j) + (ui - uj)]

- d(k,j) = d(i,j) - d(k,i)

- Update the distance matrix by calculating the distance from the new node k to every other node m: d(k,m) = ½ [d(i,m) + d(j,m) - d(i,j)].

- Repeat steps 2-6 until only two nodes remain, then connect them with a branch of the specified distance [10]. The NJ method is fast and efficient, making it suitable for analyzing large datasets. The resulting unrooted tree can be rooted post-hoc using an outgroup or other criteria to produce a rooted tree for evolutionary interpretation [11].

Protocol 2: Rooting an Unrooted Tree

An unrooted tree obtained from algorithms like NJ requires additional steps to establish a root. The most common and reliable method is the outgroup method:

- Outgroup Selection: Identify one or more taxa known to have diverged before the most recent common ancestor of all other taxa (the ingroup) based on independent biological evidence.

- Tree Rerooting: Apply an algorithm that places the root on the branch connecting the outgroup to the rest of the tree. This positions the outgroup as the most distantly related taxon, making the ingroup monophyletic.

- Root Validation: Assess the biological reasonableness of the rooted tree. The resulting phylogeny should be consistent with established knowledge about the evolutionary relationships.

Alternative methods for rooting include the midpoint rooting, which assumes a molecular clock and places the root at the midpoint of the longest path between two taxa, and molecular clock rooting using Bayesian or likelihood methods that incorporate rate models. However, the outgroup method is generally preferred when a suitable outgroup is available.

Visualization and Interpretation

Tree Layouts and Their Applications

Effective visualization is crucial for interpreting and communicating phylogenetic results. The ggtree package in R provides a versatile platform for visualizing and annotating phylogenetic trees with diverse associated data [7] [6]. It supports multiple tree layouts, each suited to different analytical and presentation needs.

Table 3: Phylogenetic Tree Layouts and Their Applications in ggtree

| Tree Layout | Description | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Rectangular | Classic rectangular layout with root on left and tips on right [6] | Standard publications, easy interpretation of rooted trees |

| Circular | Rooted tree displayed in a circular format [7] [6] | Visualizing large trees, aesthetic presentations |

| Fan | Similar to circular but with adjustable opening angle [7] [6] | Balancing space usage and visibility for large trees |

| Unrooted (Equal Angle) | Radial diagram with angles proportional to tip count [7] [6] | Displaying unrooted topology, can cluster tips |

| Unrooted (Daylight) | Improved unrooted layout optimizing space usage [7] [6] | Efficient space utilization for complex unrooted trees |

| Slanted | Rectangular layout with slanted edges [6] | Cladograms, emphasizing branching pattern over branch lengths |

| Time-Scaled | Axis represents real time with most recent sampling date [7] | Time-measured phylogenies, evolutionary timeline studies |

Diagram 2: Tree Layouts for Rooted vs. Unrooted Visualization

Interpreting Evolutionary Direction in Rooted Trees

In a properly rooted tree, several key evolutionary inferences become possible. The root node represents the most recent common ancestor of all taxa in the tree. The branching order indicates the sequence of divergence events, showing which lineages split off earlier or later from common ancestors. Branch lengths, when scaled, can represent the amount of genetic change or evolutionary time. Sister taxa are pairs of taxa that share an immediate common ancestor, representing each other's closest relatives. Monophyletic groups (clades) include an ancestral node and all of its descendants, representing complete evolutionary units. Directional evolutionary processes such as adaptation, convergence, and divergence can be hypothesized based on the distribution of traits across the rooted topology.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Software and Packages for Phylogenetic Analysis

| Tool/Package | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| ggtree [7] [6] | Advanced visualization and annotation of phylogenetic trees | Creating publication-quality figures; integrating tree data with associated annotations |

| ape [14] [6] | Fundamental phylogenetic analysis and evolution in R | Reading, writing, and manipulating tree structures; basic comparative analyses |

| IQ-TREE [14] [11] | Efficient phylogenomic inference by maximum likelihood | Building large-scale phylogenies with model selection and ultrafast bootstrapping |

| BEAST2 [14] | Bayesian evolutionary analysis sampling trees | Dating evolutionary events; reconstructing ancestral states using Bayesian MCMC |

| MEGA [14] [11] | Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis desktop software | User-friendly interface for multiple methods; model testing and tree inference |

| PhyML [14] | Fast and accurate maximum likelihood estimation | Rapid ML tree building with smart algorithm for hill-climbing |

| Geneious [15] | Integrated molecular biology and sequence analysis platform | End-to-end workflow from sequence alignment to tree building and visualization |

Practical Guidance for Method Selection

Choosing between rooting approaches and tree-building methods depends on the research question and data characteristics. For studies of evolutionary timelines, ancestral state reconstruction, or trait evolution, a rooted tree is essential, and methods like Bayesian dating or outgroup rooting should be employed. When analyzing large datasets with hundreds or thousands of taxa where computational efficiency is paramount, fast distance-based methods like Neighbor-Joining are advantageous, producing an unrooted tree that can be rooted subsequently. If the molecular clock assumption is reasonable for the dataset (e.g., closely related viruses), UPGMA can provide a rooted tree directly, though its assumptions should be verified. For maximum accuracy with smaller datasets where computational intensity is manageable, model-based approaches like Maximum Likelihood or Bayesian Inference are preferred, though they typically produce unrooted trees requiring post-processing rooting.

When directionality and ancestry are not the primary focus—for instance, when simply exploring evolutionary relationships or testing network hypotheses—an unrooted tree may be sufficient. Each method carries specific data requirements and assumptions; NJ requires a distance matrix, ML requires an evolutionary model, and Bayesian methods require prior distributions. Researchers should match their choice to their data type and analytical goals, using multiple methods where possible to assess robustness. Tools like ggtree are then invaluable for visualizing, comparing, and annotating the resulting phylogenetic hypotheses, enabling researchers to extract meaningful biological insights from the complex patterns of evolutionary history [7] [6].

In modern biological research, the graphical representation of evolutionary relationships is indispensable for understanding the history and relatedness of species or genes. Phylogenetic trees provide a powerful framework for visualizing these relationships, playing a critical role in fields ranging from epidemiology to drug development [11]. Among these representations, cladograms, phylograms, and chronograms serve distinct purposes and convey different types of information. Cladograms represent hypothetical relationships based on patterns of ancestral and derived traits, while phylograms incorporate branch lengths proportional to evolutionary change, and chronograms display branches proportional to time with all tips equidistant from the root [16] [17]. Understanding the differences between these tree types, their appropriate construction methods, and their specific applications is essential for researchers analyzing evolutionary pathways, tracing disease origins, or identifying new therapeutic targets. This article provides a comprehensive overview of these fundamental phylogenetic tools within the context of advanced research applications.

Tree Types: Definitions, Features, and Applications

Core Characteristics and Comparative Analysis

The three primary types of phylogenetic trees—cladograms, phylograms, and chronograms—differ in the biological information they convey through their branch lengths and overall structure. Cladograms are the simplest form, depicting only the branching order and hierarchical pattern of relationships based on shared derived characteristics (synapomorphies) [17] [18]. Their branch lengths are arbitrary and carry no phylogenetic meaning, serving only to connect nodes [16] [18]. Phylograms provide more information by scaling branch lengths to represent the amount of evolutionary change, often measured by the number of substitutions per site in sequence alignments [16] [17]. Chronograms are scaled to time, with branch lengths proportional to real time (e.g., millions of years) and all tips equidistant from the root, making them ultrametric [16] [17].

Table 1: Comparative Features of Cladograms, Phylograms, and Chronograms

| Feature | Cladogram | Phylogram | Chronogram |

|---|---|---|---|

| Branch Length Significance | Arbitrary; no meaning [18] | Proportional to amount of evolutionary change (e.g., substitutions per site) [16] [17] | Proportional to time (e.g., millions of years) [16] [17] |

| Primary Application | Hypothesis of relationships based on shared derived traits [17] | Inferring evolutionary relationships with measure of genetic divergence [17] | Dating evolutionary events and comparing node ages across lineages [17] |

| Temporal Information | None [18] | Indirect (rates vary); does not directly represent time [17] | Direct; includes explicit time scale [16] |

| Tip Alignment | Tips line up neatly in a row or column [18] | Tips are often uneven due to varying branch lengths [16] | Tips are aligned as all are equidistant from the root [17] |

| Node Representation | Change in character state (synapomorphy) [17] | Point of lineage divergence from a common ancestor [17] | Time of lineage divergence from a common ancestor [17] |

Research Applications and Selection Guidelines

Each tree type serves specific purposes in biological research. Cladograms are foundational tools for generating initial hypotheses about relationships, particularly in morphological analyses or when molecular data is limited [18]. In drug development, they can help identify groups of related organisms that may share similar biochemical pathways. Phylograms are the most common trees in molecular phylogenetics and genomics [17]. Their ability to show degrees of genetic divergence is crucial for identifying rapidly evolving regions in pathogens, understanding gene family evolution, and selecting appropriate targets for intervention. Chronograms are essential for evolutionary studies that require a time frame, such as molecular clock analyses, correlating speciation events with geological history, and studying the origin and spread of emerging infectious diseases [17].

Table 2: Research Context and Tree Selection

| Research Objective | Recommended Tree Type | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Proposing initial evolutionary hypotheses based on traits | Cladogram | Simplifies relationships to pure branching pattern, focusing on shared derived characteristics [17] [18] |

| Quantifying genetic divergence between taxa | Phylogram | Branch lengths represent the amount of molecular evolutionary change [16] [17] |

| Correlating divergence events with geological time or fossil records | Chronogram | Provides a direct timeline of evolutionary history [16] [17] |

| Studying rates of evolution across lineages | Phylogram or Chronogram | Phylograms show variation in substitution rates; Chronograms allow rate calibration against time [17] |

| Analyzing recent outbreaks or transmission dynamics | Chronogram | Enables precise dating of emergence and spread events [17] |

Experimental Protocols for Tree Construction

General Workflow for Phylogenetic Analysis

The process of constructing a robust phylogenetic tree, regardless of the final type, follows a systematic workflow. The initial step involves sequence collection, where homologous DNA, RNA, or protein sequences are gathered from public databases like GenBank, EMBL, or DDBJ, or from experimental data [11]. This is followed by multiple sequence alignment using tools such as Clustal Omega, MAFFT, or MUSCLE to identify corresponding positions across sequences [16] [18]. Accurate alignment is critical, as errors here propagate through the entire analysis. The aligned sequences are then trimmed to remove unreliable regions that might introduce noise [11]. The next step is evolutionary model selection, where statistical criteria (e.g., AIC, BIC) are used to choose the best-fit nucleotide or amino acid substitution model (e.g., Jukes-Cantor, Kimura, HKY85, GTR) for the data [11]. Finally, tree inference is performed using specific algorithms, followed by tree evaluation using statistical methods like bootstrapping to assess branch support [16] [11].

Diagram 1: Phylogenetic Tree Construction Workflow (Max Width: 760px)

Method-Specific Protocols

Distance-Based Methods (e.g., Neighbor-Joining)

Distance-based methods begin by calculating a distance matrix from the multiple sequence alignment. This matrix contains pairwise estimates of evolutionary distance between all sequences, often corrected by a model like Jukes-Cantor or Kimura's two-parameter model to account for multiple substitutions [11]. The Neighbor-Joining (NJ) algorithm then starts with a star-like unrooted tree and iteratively finds the pair of taxa (or nodes) that minimizes the total branch length. These taxa are connected to a new internal node, and the distance matrix is recalculated with the new node replacing the paired taxa. This process repeats until a fully resolved tree is obtained [16] [11]. NJ is computationally efficient and suitable for large datasets, but it only produces a single tree and may lose information by reducing sequence data to pairwise distances [16].

Character-Based Methods (Maximum Parsimony and Maximum Likelihood)

Maximum Parsimony (MP) seeks the tree that requires the smallest number of evolutionary changes to explain the observed sequences. The protocol involves identifying informative sites in the alignment—positions with at least two different character states, each present in at least two sequences [11]. For each possible tree topology (searched via exhaustive, branch-and-bound, or heuristic methods like SPR and NNI), the minimum number of changes required is calculated. The tree(s) with the fewest changes are selected as the most parsimonious [11]. MP is model-free but can be misled by homoplasy and becomes computationally intense with many taxa.

Maximum Likelihood (ML) finds the tree topology, branch lengths, and model parameters that maximize the probability of observing the aligned sequences given the evolutionary model. The protocol requires selecting a specific nucleotide or amino acid substitution model (e.g., GTR for DNA) [11]. A heuristic search of tree space is conducted, and for each candidate topology, branch lengths and substitution parameters are optimized using numerical methods. The tree with the highest likelihood score is chosen. ML is statistically rigorous and accounts for various evolutionary processes but is computationally intensive [16] [11].

Constructing a Chronogram

Constructing a chronogram involves additional steps to convert evolutionary change into time. First, a standard phylogram is often estimated using a method like ML. Then, calibration is performed using known historical dates, such as fossil evidence, biogeographic events, or historically sampled sequences (e.g., for viruses) [17]. These calibration points are used with a molecular clock model (strict or relaxed) to convert branch lengths from substitutions per site to time. The result is an ultrametric tree where all tips are aligned, representing the present day, and branch lengths are proportional to time, allowing direct comparison of node ages across lineages [17].

Successful phylogenetic analysis relies on a suite of computational tools, software packages, and data resources. The following table details key solutions used in the field.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Phylogenetic Analysis

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Geneious Prime | Integrated bioinformatics software platform | Multiple sequence alignment, tree building with NJ/UPGMA, and tree visualization [16] |

| Clustal Omega | Multiple sequence alignment tool | Aligning DNA, RNA, or protein sequences prior to phylogenetic analysis [18] |

| R Phylogenetic Packages (e.g., ape, phangorn) | Statistical environment and packages for phylogenetics | Conducting ML, BI, and distance-based analyses; tree manipulation and visualization [11] |

| "chronogram" R package | Data annotation and management for temporal series | Annotating clinical and laboratory data in time-based studies, such as infection and vaccination timelines [19] |

| Calibration Points (Fossils, Historical Samples) | Reference points with known dates | Converting phylograms into chronograms by anchoring the molecular clock to real time [17] |

| Bootstrap/Jaccknife Resampling | Statistical technique for assessing tree robustness | Evaluating confidence in tree branches by sampling alignment sites with replacement [16] |

Cladograms, phylograms, and chronograms each offer unique insights into evolutionary relationships, serving as fundamental tools for researchers and drug development professionals. The selection of an appropriate tree type and construction method must be guided by the specific research question, with cladograms providing basic hypotheses of relationship, phylograms quantifying genetic divergence, and chronograms placing evolutionary events in a temporal context. As phylogenetic applications continue to expand into areas like vaccine development and pathogen surveillance, the rigorous application of these protocols and a deep understanding of the underlying assumptions of each tree type become increasingly critical for generating reliable, actionable biological insights.

A phylogenetic tree is a graphical representation that illustrates the evolutionary relationships between biological taxa, such as species or gene families, based on their physical or genetic characteristics [11]. Comprising nodes and branches, these trees use nodes to represent taxonomic units and branches to depict the evolutionary relationships and estimated time between these units [11]. Phylogenetic trees can be categorized into rooted trees, which have a root node indicating the most recent common ancestor and suggesting an evolutionary direction, and unrooted trees, which lack a root node and only illustrate relationships without evolutionary direction [11].

In modern biological research, phylogenetic trees play a critical role. They visually present evolutionary history and phylogenetic relationships, helping researchers understand the causes of morphological diversity and evolutionary patterns [11]. Furthermore, they help reveal population genetics patterns such as genetic structure, gene flow, and genetic drift, providing essential insights for evolutionary biology, epidemiology, drug development, and conservation genetics [11] [20].

Constructing a reliable phylogenetic tree involves a multi-stage process that transforms raw sequence data into an evolutionary hypothesis. The general workflow, applicable to most phylogenetic studies, begins with sequence collection and progresses through alignment, model selection, tree inference, and finally, tree evaluation and visualization [11] [20]. The following diagram summarizes this essential workflow and the key choices at each stage.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Sequence Alignment and Curation

Objective: To produce a high-quality multiple sequence alignment (MSA) from raw molecular sequences, which forms the foundation for reliable phylogenetic inference.

- Software Options: Multiple alignment tools are available, each with specific strengths. Common choices include MAFFT, MUSCLE, and Clustal Omega [20] [21]. For instance, MUSCLE is suitable for medium-sized datasets and is often used with default parameters, while MAFFT offers advanced options for complex alignments [21].

- Procedure:

- Sequence Input: Upload or input your multi-sequence file in FASTA format. Ensure sequence names do not contain special characters (only numbers, letters, and underscores are allowed) [20].

- Tool Selection: Choose an alignment algorithm based on your data characteristics. For general purposes, MAFFT is a robust default choice [20].

- Parameter Configuration: While default parameters are recommended for most datasets, adjustments may be necessary for specialized cases [20]:

- For high-complexity datasets, increase the

Max-Iteratevalue to optimize alignment iterations. - Select a pairwise alignment method:

6merfor shorter sequences,localpairfor sequences with local similarities/indels, orgenafpair/globalpairfor longer sequences requiring a global alignment [20].

- For high-complexity datasets, increase the

- Execution and Output: Run the alignment and download the resulting alignment file (typically in FASTA or PHYLIP format).

- Alignment Trimming: After alignment, inspect and trim the MSA to remove unreliably aligned regions that can introduce noise and mislead tree inference [11]. Tools like GUIDANCE2 can be used to score alignment confidence and automatically remove columns with low scores [20].

Protocol 2: Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference

Objective: To estimate a phylogenetic tree and posterior probability of its nodes using Bayesian inference, which incorporates prior knowledge and provides a robust probabilistic framework for assessing uncertainty [20].

- Software: This protocol utilizes an integrated workflow with GUIDANCE2, ProtTest/MrModeltest, and MrBayes [20].

- Procedure:

- Robust Sequence Alignment: Perform sequence alignment using GUIDANCE2 with MAFFT as the core aligner to account for alignment uncertainty [20].

- Format Conversion: Convert the resulting alignment into NEXUS format, required by MrBayes, using tools like MEGA X and PAUP* [20].

- Evolutionary Model Selection: Identify the optimal model of sequence evolution using statistical criteria like AIC or BIC.

- Bayesian Inference in MrBayes:

- Prepare a NEXUS file containing the aligned sequences and a

mrbayesblock specifying the analysis parameters (the model selected in step 3, Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) settings, etc.) [20]. - Execute the analysis in MrBayes. The software will run MCMC chains to sample trees and parameters from their posterior distribution.

- Monitor MCMC diagnostics to ensure convergence. After discarding an appropriate number of samples as "burn-in," summarize the remaining trees to produce a consensus tree with posterior probabilities clade support [20].

- Prepare a NEXUS file containing the aligned sequences and a

Protocol 3: Alignment-Free Phylogeny with Maximum Likelihood

Objective: To construct a phylogenetic tree directly from raw sequencing reads or unassembled genomes, bypassing the computationally intensive and potentially error-prone steps of genome assembly and multiple sequence alignment [22] [23]. This is particularly useful for large datasets, low-coverage sequencing, or data with complex genomic rearrangements.

- Software: Read2Tree or Peafowl [22] [23].

- Procedure using Read2Tree:

- Read Mapping: Align raw sequencing reads (from Illumina, PacBio, or ONT) to a reference set of orthologous genes [22].

- Sequence Reconstruction: For each orthologous group, reconstruct a consensus sequence from the aligned reads [22].

- Sequence Selection: Retain the best reference-guided reconstructed sequence based on criteria like the number of reconstructed nucleotide bases [22].

- Alignment and Tree Inference: Add the selected consensus sequences to the multiple sequence alignment for each orthologous group and proceed with conventional tree inference methods (e.g., IQ-TREE) [22].

- Procedure using Peafowl:

- k-mer Generation: Process input DNA sequences to generate all possible subsequences of length k (k-mers), typically using canonical counting which treats a k-mer and its reverse complement as identical [23].

- Binary Matrix Construction: Build a binary matrix where rows represent k-mers, columns represent species, and entries indicate the presence (1) or absence (0) of that k-mer in the species' genome [23].

- k-mer Length Selection: Choose an appropriate k-mer length by selecting the value of k that maximizes the entropy of the binary matrix, thereby capturing the most informative phylogenetic signal [23].

- Tree Inference: Apply a maximum likelihood approach to the binary matrix to estimate the phylogenetic tree that best explains the observed k-mer presence/absence patterns [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 1: Key Software and Analytical Tools for Phylogenetics

| Tool Name | Function / Application | Key Features / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MAFFT [20] [21] | Multiple sequence alignment | Offers multiple strategies (e.g., FFT-NS-2, G-INS-i) for different alignment problems. |

| MUSCLE [21] | Multiple sequence alignment | Fast and accurate for medium-sized datasets; often used with default parameters. |

| GUIDANCE2 [20] | Alignment confidence assessment & trimming | Scores column reliability and removes unreliable regions; improves alignment quality. |

| IQ-TREE [11] [22] | Maximum likelihood tree inference | Efficient for large datasets; implements ModelFinder for model selection and ultrafast bootstrapping. |

| MrBayes [20] | Bayesian tree inference | Uses MCMC algorithms to estimate posterior probabilities of trees and parameters. |

| ProtTest [20] | Model selection (protein sequences) | Finds best-fit model of protein evolution using AIC/BIC criteria. |

| MrModeltest [20] | Model selection (DNA sequences) | Finds best-fit nucleotide substitution model using AIC/BIC criteria. |

| Read2Tree [22] | Alignment-free tree inference | Directly processes raw reads into orthologous gene alignments, bypassing assembly. |

| treeio & ggtree [24] | Tree data management & visualization | R packages for parsing, manipulating, and annotating phylogenetic trees with complex data. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Comparative Analysis of Tree-Building Methods

Table 2: Characteristics of Common Phylogenetic Tree Construction Methods

| Method | Category | Basic Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neighbor-Joining (NJ) [11] | Distance-based | Uses a distance matrix and clustering to build a tree by sequentially merging the closest nodes. | Fast computation; suitable for large datasets; allows different branch lengths. | Converts sequences to distances, potentially losing information; accuracy depends on distance metric. |

| Maximum Parsimony (MP) [11] | Character-based | Finds the tree that requires the smallest number of evolutionary changes. | Straightforward principle; no explicit model assumptions. | Can be inaccurate if evolutionary rates are high; often produces multiple equally optimal trees. |

| Maximum Likelihood (ML) [11] | Character-based | Finds the tree and model parameters that maximize the probability of observing the sequence data. | Uses explicit evolutionary models; generally robust and accurate; lower probability of systematic errors. | Computationally intensive; heuristic searches may not find the globally optimal tree. |

| Bayesian Inference (BI) [20] | Character-based | Estimates the posterior probability of trees and parameters by combining the likelihood with prior distributions. | Incorporates prior knowledge; quantifies uncertainty (e.g., with posterior probabilities). | Computationally very intensive; results can be sensitive to prior choice and require MCMC diagnostics. |

Advanced Visualization and Interpretation

Effective visualization is critical for interpreting and communicating phylogenetic results. The R packages treeio and ggtree provide a powerful and flexible platform for visualizing phylogenetic trees and associated data [24]. These tools allow researchers to:

- Parse and Integrate Data: Import trees, phylogenetic placement data (e.g., from jplace files), and associated metadata into the R environment [24].

- Annotate Trees: Map various data types (e.g., trait data, divergence times, support values) onto the tree structure using different colors, shapes, and sizes [24].

- Explore Uncertainty: Visualize placement uncertainty, for example, by coloring branches based on likelihood weight ratios (LWRs) or posterior probabilities, providing a clearer representation of confidence in specific placements [24].

- Handle Large Trees: Employ techniques such as collapsing or extracting subtrees to focus on specific clades of interest, enhancing the clarity of visualizations for large datasets [24].

In phylogenetic analysis, the accuracy of the final evolutionary tree is fundamentally dependent on the quality of the multiple sequence alignment (MSA) from which it is derived [25] [11]. MSA is a foundational technique in bioinformatics that compares and aligns multiple biological sequences to reveal similarities and differences, providing insights into sequence homology and evolutionary relationships [25]. However, MSAs often contain regions of low confidence and high noise, which can mislead phylogenetic inference [26]. Consequently, alignment trimming has become a critical step in phylogenomic pipelines to remove doubtfully aligned or highly saturated parts of the alignment before phylogenetic analysis [26]. This Application Note details the core principles, tools, and protocols for ensuring alignment accuracy, framed within the context of robust phylogenetic tree construction.

The Critical Link Between Alignment Quality and Phylogenetic Inference

The reliability of MSA results directly determines the credibility of downstream biological conclusions, including phylogenetic trees [25]. MSA is inherently an NP-hard problem, making it theoretically impossible to guarantee a globally optimal solution with current heuristic algorithms [25]. These challenges are compounded by the explosive growth of sequencing data, sequence variability, and potential experimental errors [25].

Inaccurate alignments can introduce systematic errors and produce misleading phylogenetic signals. Regions of an alignment with inaccurate homology assessment or high levels of saturation are expected to degrade or mislead phylogenetic inference [26]. Even when saturated change does not confuse assessments of site homology, it may still degrade the analytical outcome. Therefore, applying trimming algorithms to delete unreliable alignment regions is essential for producing robust phylogenetic hypotheses.

Core Principles of Effective Trimming

Effective trimming strategies are based on the principle that phylogenetic noise is not detectable in a single site (a single character or column in the alignment) but is instead signaled by discord among characters [26]. Methods that examine base frequencies at individual sites without comparing character patterns for discord are not designed to assess true phylogenetic noise [26]. The ideal trimming approach identifies and removes regions where a large proportion of sites have conflicting phylogenetic signal—sites that cannot agree on any possible evolutionary tree [26].

Quantitative Comparison of Alignment and Trimming Methods

Multiple Sequence Alignment Post-Processing Methods

Table 1: Classification and characteristics of MSA post-processing methods.

| Method Category | Representative Tool | Core Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-Alignment | M-Coffee [25] | Integrates multiple initial MSAs into a consensus alignment using a consistency library. | Integrates strengths of different aligners; produces more consistent alignments. | Final accuracy depends on input alignment quality; rarely surpasses the best input. |

| Meta-Alignment | AQUA [25] | Automatically runs multiple aligners (MUSCLE3, MAFFT) and RASCAL realigner; selects best output using NorMD score. | Encapsulated workflow; automated selection of the best alignment. | Limited user customization; constrained candidate alignment range. |

| Meta-Alignment | TPMA [25] | Integrates nucleic acid MSAs by sequentially merging alignment blocks with higher Sum-of-Pairs scores. | High efficiency on large datasets; low computational and memory requirements. | Performance highly dependent on input alignment quality. |

| Realigner (Horizontal Partitioning) | ReAligner [25] | Iteratively realigns sequences (single-type partitioning) or sequence groups (double-type, tree-dependent partitioning). | Directly improves local alignment accuracy; maintains computational efficiency. | High computational demand for some strategies. |

Alignment Trimming Tools and Their Performance

Table 2: Overview and application guidance for phylogenetic trimming tools.

| Tool | Underlying Principle | Data Type | Key Metric | Impact on Phylogeny |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PhyIN [26] | Phylogenetic incompatibility among neighboring sites. | DNA/Protein (UCE data tested). | Conflict between adjacent sites. | Preserves discord between gene trees and species trees; works on single loci. |

| trimAl [26] | Comparison of character signals to a bulk-data phylogeny or distance matrix. | DNA/Protein. | Automated reliability score. | Improves signal-to-noise ratio; model can be heuristic. |

| Gblocks [26] | Individual site conservation based on state frequencies. | DNA/Protein. | Base frequency per column. | May remove true phylogenetic signal; not targeted at phylogenetic noise. |

| ClipKIT [26] | Retention of parsimony-informative sites. | DNA/Protein. | Base frequency per column. | May retain highly homoplasious and misleading sites. |

Experimental Protocols for Alignment and Trimming

Protocol 1: MSA Construction and Refinement Using Meta-Alignment

Purpose: To generate a high-confidence Multiple Sequence Alignment by leveraging multiple alignment tools and achieving consensus.

Materials:

- Software: M-Coffee [25], T-Coffee [25], MUSCLE [25], MAFFT [25] [27].

- Input Data: File containing unaligned sequences (FASTA format).

Procedure:

- Generate Initial Alignments: Use at least two different aligners (e.g., MUSCLE and MAFFT) with default parameters to produce independent MSAs from the same unaligned sequence dataset [25].

- Construct Consistency Library: Input the initial alignments into M-Coffee. The tool will match all pairs of characters (bases or amino acids) across the different alignments [25].

- Weight Character Pairs: M-Coffee assigns weights to character pairs based on their consistency across the initial alignments, strengthening signals supported by a consensus [25].

- Generate Final MSA: The weighted library is processed by the T-Coffee algorithm to produce a global MSA that maximally reflects the consensus among the input alignments [25].

Protocol 2: Alignment Trimming Using PhyIN Based on Phylogenetic Incompatibility

Purpose: To trim unreliable regions from an MSA by identifying and removing sites with high local phylogenetic conflict, without inferring a tree.

Materials:

- Software: PhyIN [26].

- Input Data: A single multiple sequence alignment (FASTA or other common alignment format).

Procedure:

- Prepare Input Alignment: Load your MSA file into PhyIN.

- Assess Neighboring Site Compatibility: The algorithm scans the alignment and assesses pairs of adjacent sites (characters) for phylogenetic compatibility [26].

- Identify Incompatible Sites: Two sites are deemed incompatible if no tree exists on which both could have evolved without homoplasy (convergence or reversal). For example, for binary characters, if all four state combination patterns (0-0, 0-1, 1-0, 1-1) are present, the sites are incompatible [26].

- Trim Chaotic Regions: PhyIN deletes regions of the alignment where a high proportion of neighboring characters are in phylogenetic conflict with one another [26].

- Output Trimmed Alignment: The result is a new, shorter alignment file with chaotic regions removed, preserving areas of strong, consistent phylogenetic signal [26].

Protocol 3: Windowed MSA for Chimeric Protein Structure Prediction

Purpose: To improve the prediction accuracy of chimeric protein structures by independently aligning constituent domains.

Materials:

- Software: MMseqs2 (via ColabFold API), AlphaFold-2 or AlphaFold-3 [28].

- Input Data: Sequences of the scaffold protein and the peptide tag(s) to be fused.

Procedure:

- Generate Independent MSAs: Use MMseqs2 to search UniRef30 and generate separate MSAs for the scaffold protein and the peptide tag. The scaffold sub-alignment should include the linker region [28].

- Merge Sub-alignments: Programmatically merge the two MSAs by concatenating them. Insert gap characters ('-') in the peptide-derived sequences across the scaffold region, and vice-versa, to preserve original alignment lengths and prevent spurious residue pairing [28].

- Predict Structure: Use the merged, windowed MSA as direct input to AlphaFold-2 or AlphaFold-3 for structure prediction [28].

- Validate: Compare the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) of the predicted structure against an experimentally determined reference structure, if available. This approach has been shown to yield lower (better) RMSD values in 65% of test cases [28].

Workflow Visualization and Reagent Solutions

Phylogenetic Analysis Workflow from Sequences to Trees

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 3: Key reagents, software, and materials for phylogenetic analysis.

| Item / Solution | Function / Application | Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| MAFFT [25] [29] [27] | Software for generating the initial Multiple Sequence Alignment. | Critical for creating the foundational alignment; often used as one input for meta-aligners [25]. |

| MUSCLE [25] [27] | Alternative software for generating the initial Multiple Sequence Alignment. | Provides a different heuristic approach; used to create diversity in meta-alignment inputs [25]. |

| M-Coffee [25] | Meta-alignment tool that combines results from multiple aligners. | Integrates alignments from tools like MUSCLE and MAFFT to produce a consensus MSA [25]. |

| PhyIN [26] | Alignment trimming tool based on phylogenetic incompatibility. | Used to remove noisy regions from an MSA before tree building, improving signal [26]. |

| Consistent DNA Polymerase & Kits | For PCR amplification of target loci during sequence data generation. | Using the same supplier and kit batch minimizes technical variation in upstream data [11] [30]. |

| Standardized Buffers | For reaction consistency in sequencing library preparation. | Ensures reproducibility across sample preparation and sequencing runs [30]. |

| AlphaFold-3 [28] | Protein structure prediction software. | Used for validating alignment strategies on chimeric proteins via Windowed MSA protocol [28]. |

| High-Fidelity Sequencing Kit | For generating accurate raw sequence data. | High-fidelity reduces base-calling errors, improving initial alignment quality [25]. |

A Deep Dive into Tree-Building Algorithms and Their Real-World Applications

Distance-based methods represent a foundational approach in computational phylogenetics, enabling researchers to infer evolutionary relationships from molecular data. These methods transform sequence alignments into pairwise distance matrices, which subsequently guide the construction of phylogenetic trees. Within this domain, the Neighbor-Joining (NJ) and Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA) algorithms stand as two widely utilized techniques, each with distinct philosophical underpinnings and operational characteristics. This application note provides a detailed examination of both methods, offering structured protocols, performance comparisons, and practical implementation guidance tailored for researchers and bioinformatics professionals engaged in evolutionary analysis, comparative genomics, and drug discovery workflows.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of NJ and UPGMA Methods

| Feature | Neighbor-Joining (NJ) | Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean (UPGMA) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Minimum evolution; iterative selection of pairs minimizing total tree length [31] | Hierarchical clustering; sequential amalgamation of most similar clusters [32] |

| Tree Type | Unrooted (can be rooted with an outgroup) | Rooted (assumes ultrametricity) [33] |

| Molecular Clock Assumption | Does not assume a constant rate [31] | Assumes a constant rate (molecular clock) [33] |

| Computational Complexity | O(n³) for the canonical algorithm [34] | O(n³) for the canonical algorithm [35] |

| Primary Output | Branch lengths and topology [36] | Dendrogram with equal root-to-tip distances [32] |

Methodological Foundations

The Neighbor-Joining Algorithm

The Neighbor-Joining method, introduced by Saitou and Nei in 1987, is a bottom-up clustering algorithm designed to recover phylogenetic trees from evolutionary distance data [36]. Its objective is to find pairs of operational taxonomic units (OTUs) that minimize the total branch length at each stage of clustering, ultimately producing a parsimonious tree [36]. The algorithm proceeds iteratively, starting with a star-like tree and progressively identifying neighbor pairs to join until a fully resolved tree is obtained.

The mathematical core of NJ relies on the calculation of a Q-matrix, which guides the selection of nodes to join at each iteration. For a pair of distinct taxa i and j, the Q-value is calculated as [31]:

Q(i,j) = (r - 2) d(i,j) - R(i) - R(j) (1)

where:

- d(i,j) is the distance between taxa i and j

- r is the current number of nodes in the distance matrix

- R(i) and R(j) are the sums of distances from taxon i and j to all other taxa, respectively

The pair with the minimum Q-value is selected for joining. This criterion effectively identifies pairs that minimize the total tree length when connected through a new internal node.

Upon joining taxa i and j into a new composite node u, the branch lengths from i and j to u are calculated as follows [31]:

δ(i,u) = ½ d(i,j) + [R(i) - R(j)] / [2(r - 2)] (2)

δ(j,u) = d(i,j) - δ(i,u) (3)

The distance matrix is then updated with distances between the new node u and each remaining taxon k using the formula [31]:

d(u,k) = ½ [d(i,k) + d(j,k) - d(i,j)] (4)

This process repeats until only three nodes remain, at which point the final branch lengths are calculated.

The UPGMA Algorithm

The Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean is a simpler agglomerative hierarchical clustering method that constructs rooted trees (dendrograms) under the assumption of a constant molecular clock [32]. This assumption implies that evolutionary rates are constant across all lineages, resulting in an ultrametric tree where the distance from the root to every leaf is equal [33].

At each step, UPGMA identifies the two clusters (initially single taxa) with the smallest distance in the current matrix and merges them into a new, higher-level cluster. The distance between any two clusters A and B is defined as the arithmetic mean of all pairwise distances between members of A and members of B [32]:

d(AB) = (1/|A||B|) Σ d(x,y) for x in A, y in B (5)

When clusters A and B are merged to form a new cluster (AB), the distance between (AB) and any other cluster X is calculated as a weighted average [33]:

d((AB),X) = (|A|/(|A|+|B|)) · d(A,X) + (|B|/(|A|+|B|)) · d(B,X) (6)

This averaging process gives equal weight to all original taxa in the clusters, ensuring that the resulting tree is ultrametric. The algorithm continues until all taxa have been merged into a single cluster.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Constructing a Neighbor-Joining Tree

This protocol provides a step-by-step procedure for implementing the Neighbor-Joining algorithm using a distance matrix as input.

Input Requirements: A symmetric distance matrix where elements represent evolutionary distances (e.g., p-distances, Jukes-Cantor distances, Kimura 2-parameter distances) between all pairs of taxa.

Table 2: Workflow for Manual NJ Tree Construction

| Step | Procedure | Key Calculations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Initialization | Begin with a star tree of n taxa and the corresponding n×n distance matrix, D. | Set the current number of clusters r = n. |

| 2. Q-matrix Calculation | For the current r×r matrix, compute the Q-matrix. | For all i,j: Q(i,j) = (r-2)×d(i,j) - R(i) - R(j), where R(i) = Σ d(i,k) for k=1 to r. |

| 3. Pair Selection | Identify the pair i,j with the minimum Q(i,j). | If multiple pairs share the same minimum value, selection can be arbitrary. |

| 4. Branch Length Estimation | Calculate branch lengths from i and j to their new parent node u. | δ(i,u) = ½ d(i,j) + [R(i)-R(j)]/[2(r-2)]δ(j,u) = d(i,j) - δ(i,u) |

| 5. Matrix Update | Create a new distance matrix with i and j replaced by u. | For each remaining taxon k: d(u,k) = ½ [d(i,k) + d(j,k) - d(i,j)] |

| 6. Iteration | Repeat steps 2-5 until r = 2. | With each iteration, r decreases by 1. |

| 7. Termination | Connect the final two nodes with a branch of length d(i,j). | The tree is now complete. |

Example Implementation: Consider a distance matrix for five taxa (a-e) with the following values [31]:

- First Q-calculation identifies a and b as neighbors (Q(a,b) = -50).

- Branch lengths: δ(a,u) = 2, δ(b,u) = 3.

- New node u replaces a and b in the updated matrix with d(u,c) = 7, d(u,d) = 7, d(u,e) = 6.

- The process continues until all nodes are joined.

Protocol 2: Constructing a UPGMA Tree

This protocol details the steps for constructing a phylogenetic tree using the UPGMA method.

Input Requirements: A symmetric distance matrix representing dissimilarities between taxa. The method assumes a molecular clock.

Table 3: Workflow for Manual UPGMA Tree Construction

| Step | Procedure | Key Calculations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Initialization | Begin with n clusters, each containing one taxon. Initialize the distance matrix D. | Set the current number of clusters r = n. |

| 2. Pair Selection | Find the two clusters A and B with the smallest distance in the current matrix. | For the initial step, this is simply the smallest d(i,j). |

| 3. Branch Length Estimation | Create a new node U parent to A and B. | δ(A,U) = δ(B,U) = d(A,B)/2 |

| 4. Cluster Merging | Merge clusters A and B to form a new cluster (AB). | The size of the new cluster: |AB| = |A| + |B| |

| 5. Matrix Update | Update the distance matrix by removing A and B, and adding (AB). | For any other cluster X: d((AB),X) = (|A|·d(A,X) + |B|·d(B,X)) / (|A|+|B|) |

| 6. Iteration | Repeat steps 2-5 until only one cluster remains. | With each iteration, r decreases by 1. |

Example Implementation: Using the 5S ribosomal RNA sequence alignment of five bacteria [32]:

- Smallest distance: d(a,b) = 17. Merge a and b to form cluster (ab).

- Branch lengths: δ(a,u) = δ(b,u) = 8.5.

- Calculate new distances: d((ab),c) = (21+30)/2 = 25.5, d((ab),d) = (31+34)/2 = 32.5, d((ab),e) = (23+21)/2 = 22.

- Continue until all clusters are merged.

Visualization of Method Workflows

Figure 1: Comparative Workflow of NJ and UPGMA Algorithms. NJ (red path) iteratively minimizes total tree length via Q-matrix calculations, producing unrooted trees. UPGMA (green path) sequentially merges the closest clusters using arithmetic averaging, producing rooted ultrametric trees under a molecular clock assumption.

Performance Analysis and Optimization

Computational Considerations

The canonical implementations of both NJ and UPGMA algorithms exhibit O(n³) time complexity, which becomes a significant constraint with large datasets [34] [35]. However, optimized implementations can achieve O(n²) performance in practice [34].

Table 4: Performance Comparison and Optimization Strategies

| Aspect | Neighbor-Joining | UPGMA |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Complexity | O(n³) for canonical algorithm [34] | O(n³) for canonical algorithm [35] |

| Optimized Complexity | O(n²) with quad-tree structures [34] | O(n²) with optimal implementations [35] |

| Memory Requirements | O(n²) for distance matrix [34] | O(n²) for distance matrix [35] |

| Parallelization Approaches | GPU implementation achieves 26× speedup [35] | Multi-GPU implementation achieves 3-7× speedup [35] |

| Scalability | Suitable for medium to large datasets (100-10,000 taxa) | Suitable for small to medium datasets (<1000 taxa) |

Empirical evaluations on protein sequence alignments from the Pfam database demonstrate that optimized NJ implementations (e.g., QuickJoin) can achieve significant speedups compared to canonical implementations (e.g., QuickTree), with performance evolving as Θ(n²) rather than Θ(n³) on empirical data [34].

Method Selection Guidelines

The choice between NJ and UPGMA depends on research objectives, data characteristics, and computational resources:

Use Neighbor-Joining when:

Use UPGMA when:

Table 5: Key Computational Tools and Resources for Distance-Based Phylogenetics

| Resource | Type | Function | Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|

| QuickJoin | Software Tool | Optimized NJ implementation with quad-tree structures for faster tree reconstruction [34] | Standalone application |

| GPU-UPGMA | Software Tool | Parallel UPGMA implementation leveraging GPU architecture for large datasets [35] | CUDA-based implementation |

| Distance Matrix | Data Structure | Stores pairwise evolutionary distances between all taxa; foundational input for both methods [31] | Typically symmetric n×n matrix |

| Q-Matrix | Data Structure | Guides neighbor selection in NJ by combining direct distances and net divergence [31] | Calculated iteratively from distance matrix |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment | Data Preparation | Generates input for distance calculation; critical preliminary step for accurate tree inference | Tools: ClustalW, MAFFT, MUSCLE |

Advanced Applications and Current Research

Distance-based methods continue to evolve, with recent research focusing on performance optimization and addressing methodological limitations. Parallel computing approaches, particularly GPU implementations, have demonstrated substantial improvements in processing time for large datasets. MGUPGMA, a novel parallel UPGMA implementation on multiple GPUs, achieves 3-7× speedup over implementations on modern CPUs and single GPUs [35].