Strategies to Improve Molecular Docking Accuracy: A Guide for Drug Discovery Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to enhance the accuracy and reliability of molecular docking.

Strategies to Improve Molecular Docking Accuracy: A Guide for Drug Discovery Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to enhance the accuracy and reliability of molecular docking. It explores the foundational principles of docking algorithms and scoring functions, examines advanced methodological improvements including the integration of machine learning and molecular dynamics, outlines practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing docking protocols, and presents rigorous validation and comparative analysis techniques. By synthesizing the latest advancements and best practices, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to make more confident predictions in structure-based drug design, ultimately improving the efficiency of lead compound identification and optimization.

Understanding the Core Principles and Challenges of Molecular Docking

Molecular docking is a computational technique that predicts the preferred orientation and conformation of a small molecule (ligand) when bound to a target receptor (usually a protein) to form a stable complex [1]. It is a cornerstone of modern structure-based drug discovery, enabling researchers to efficiently explore vast libraries of drug-like molecules and identify potential therapeutic candidates by predicting binding conformations and affinities [2].

The primary objectives of molecular docking are to:

- Predict the three-dimensional structure of a protein-ligand complex.

- Estimate the binding affinity between the ligand and receptor.

- Identify potential drug candidates through virtual screening [3].

At its core, the docking process involves two main steps: pose generation (sampling possible ligand orientations and conformations within the binding site) and scoring (ranking these poses based on estimated binding affinity using a scoring function) [4].

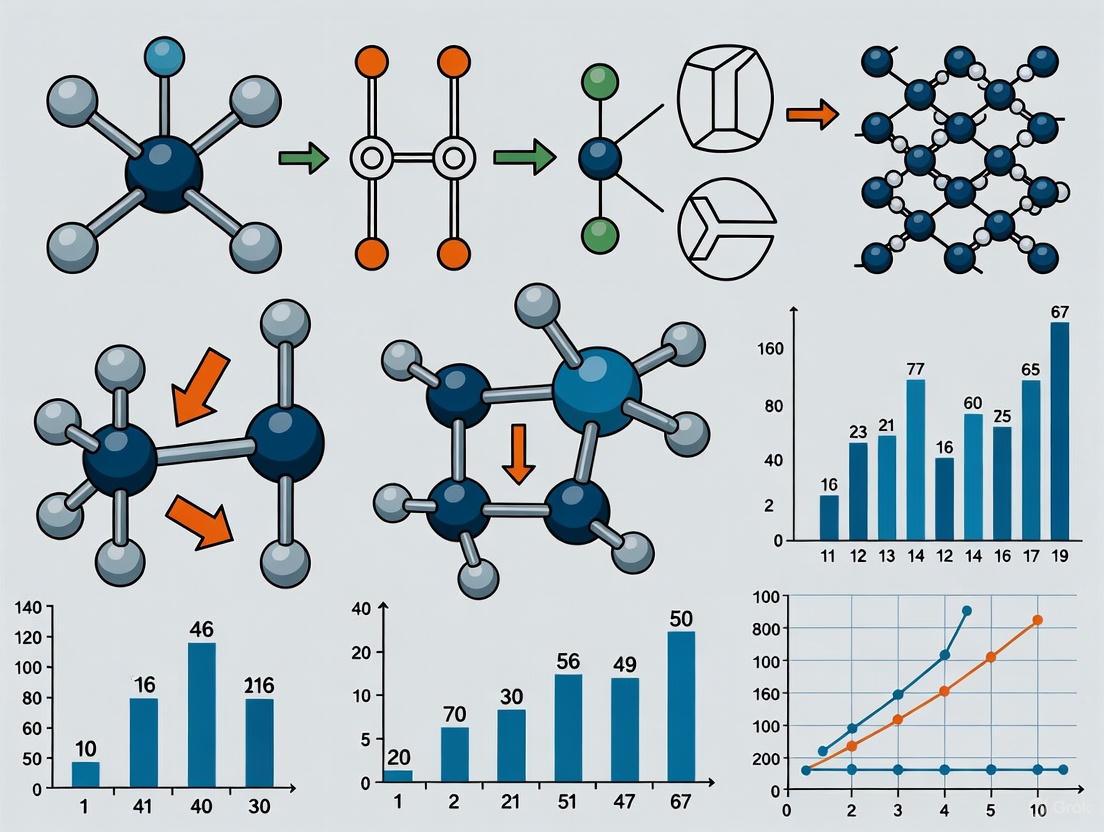

The Evolution of Docking Approaches: From Rigid Bodies to Flexible Interactions

Molecular docking methods are primarily classified based on how they treat the flexibility of the interacting molecules. The table below summarizes the key evolutionary stages.

Table: Evolution of Molecular Docking Approaches

| Docking Approach | Flexibility Handling | Key Characteristics | Example Software/Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rigid Docking | Treats both receptor and ligand as rigid bodies [1]. | - Computationally fastest- Simplifies search to six degrees of freedom (translation and rotation)- Often misses key interactions due to unrealistic assumptions | Early DOCK algorithms [2] |

| Flexible Ligand Docking | Allows ligand flexibility while keeping the protein rigid [2]. | - More realistic than rigid docking- Balances computational cost and accuracy- Becomes challenging with many rotatable bonds | AutoDock [3], GOLD [3], AutoDock Vina [4] |

| Flexible Protein-Ligand Docking | Incorporates flexibility for both ligand and receptor sidechains or backbone [2]. | - Most biologically accurate- Computationally most demanding- Essential for modeling "induced fit" | FlexPose [2], DynamicBind [2] |

The field is now being transformed by Deep Learning (DL) and Artificial Intelligence (AI). Sparked by successes like AlphaFold2, DL models such as EquiBind, TankBind, and DiffDock use advanced neural networks to predict binding poses with accuracy that rivals or surpasses traditional methods, often at a fraction of the computational cost [2] [3]. These methods are particularly effective in blind docking scenarios, where the binding site location is unknown [2].

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Docking Errors and Solutions

Table: Troubleshooting Common Molecular Docking Errors

| Error Message / Problem | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| ERROR: Can’t find or open receptor PDBQT file [5] | Incorrect file path, spaces in directory names, or file not in PDBQT format. | 1. Copy all files to a new folder with a simple name (e.g., C:\newfolder).2. Ensure files are converted to the required PDBQT format using AutoDockTools or Open Babel [5]. |

| Error 2: Cannot find the file specified. [5] | The docking program is looking for files in the wrong directory. | Set the correct startup directory in your docking software's preferences or use the cd command in the command prompt to navigate to the folder containing your files [5]. |

| Poor pose prediction accuracy | Inadequate sampling of conformational space or limitations of the scoring function. | 1. Increase the exhaustiveness of the search algorithm.2. Use a hybrid approach: run multiple docking algorithms and compare consensus poses [6]. |

| Physically implausible predictions (e.g., improper bond lengths) [2] | Common limitation of some early deep learning models, which exhibit high steric tolerance. | Use post-docking refinement with physics-based methods or Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to relax the structure and ensure physical realism [2] [3]. |

| Low correlation between docking score and experimental binding affinity | Scoring functions may not be well-generalized for your specific protein-ligand system. | Utilize machine-learning enhanced scoring functions like RefineScore or perform consensus scoring from multiple functions [7]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the key difference between a conformational search algorithm and a scoring function?

- Search Algorithm: Explores the vast space of possible ligand orientations and conformations within the binding site. Common methods include systematic search, incremental construction, Monte Carlo, and Genetic Algorithms [3].

- Scoring Function: Evaluates and ranks each generated pose by estimating the binding affinity. These can be force-field based, empirical, knowledge-based, or machine-learning based [4]. Both components are critical for successful docking.

Q2: My docking program fails to run unless I use "Run as administrator." Why? This is a permissions issue. AutoDock Tools and similar programs may require administrator privileges to access and modify necessary files and settings. Right-click the program icon and select "Run as administrator" to resolve this [5].

Q3: How can I account for protein flexibility, which is crucial for my system? Traditional docking with a rigid receptor may fail if your protein undergoes significant conformational change. To address this:

- Use ensemble docking: Dock your ligand into multiple different conformations of the same protein (e.g., from NMR or MD simulations) [3].

- Employ specialized flexible docking software like FlexPose or methods that use diffusion models to co-predict protein and ligand conformations [2].

- Apply post-docking MD simulations to refine the docked pose and incorporate induced-fit effects [3].

Q4: What are the best practices for preparing my ligand and receptor files?

- Format Conversion: Ensure your receptor and ligand files are in the correct format (e.g., PDBQT for AutoDock). Use tools like AutoDockTools or Open Babel for conversion [5].

- Addition of Hydrogens and Charges: Most docking programs require you to add hydrogens and assign partial atomic charges (e.g., Gasteiger charges) and atom types. This is typically done during the PDBQT preparation step [5] [3].

Experimental Protocols for Improving Docking Accuracy

Protocol 1: Standard Molecular Docking Workflow

This protocol outlines the foundational steps for a typical docking experiment.

Target Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structure of your target protein from the PDB or from computational predictions (e.g., AlphaFold2 models).

- Using a program like AutoDockTools, remove water molecules and extraneous co-factors (unless relevant), add hydrogens, and assign partial charges.

- Save the final prepared structure in PDBQT format [5] [3].

Ligand Preparation:

- Obtain the 3D structure of your small molecule from databases like PubChem or ZINC.

- Minimize its energy and generate plausible 3D conformations.

- Using AutoDockTools or Open Babel, add hydrogens, assign charges and atom types, and define rotatable bonds.

- Save the final prepared ligand in PDBQT format [5] [3].

Grid Box Definition:

- Define the 3D search space (grid box) where the docking will occur.

- For a known binding site, center the box on the key residues. For blind docking, the box should encompass the entire protein surface.

- Set the box size to be large enough to accommodate your ligand freely [3].

Docking Execution:

Result Analysis:

- Analyze the top-ranked output poses. Check the predicted binding energy (affinity) and the specific interactions formed (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, salt bridges).

- Visually inspect the poses in a molecular viewer to ensure they are physically plausible and biologically relevant [5] [3].

Protocol 2: A Hybrid Deep Learning and Physics-Based Refinement Protocol

This advanced protocol leverages the speed of DL for initial pose generation and the robustness of physics-based methods for refinement, addressing common DL limitations like physically unrealistic bond lengths [2] [6].

Initial Pose Generation with Deep Learning:

- Use a deep learning-based docking tool like DiffDock to generate an initial set of ligand poses.

- DL models are exceptionally fast and can provide a good starting point, especially for blind docking or when the binding site is not well-defined [2].

Pose Clustering and Selection:

- Cluster the generated poses based on their root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) to identify structurally similar families.

- Select the top representative pose from each major cluster for subsequent refinement. This ensures diversity in the poses being refined [2].

Physics-Based Refinement:

- Refine the selected DL poses using a more rigorous, physics-based method. This can be done with:

- Classical Docking Software: Re-dock the ligand using a program like AutoDock Vina, but using a very localized search box centered on the DL-predicted pose.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD): Perform a short, constrained MD simulation of the protein-ligand complex to relax the structure, remove atomic clashes, and allow for minor side-chain adjustments [3].

- Refine the selected DL poses using a more rigorous, physics-based method. This can be done with:

Rescoring with an Advanced Scoring Function:

- Score the refined poses using a modern, machine-learning-augmented scoring function (e.g., RefineScore) that incorporates physical energy terms for van der Waals and hydrogen bonding, offering improved accuracy and interpretability [7].

Validation:

- If an experimental structure of the complex is available, calculate the RMSD between your best-predicted pose and the experimental pose to validate accuracy.

- Always perform a visual inspection of the final refined model to check for sensible molecular interactions [3].

Table: Key Resources for Molecular Docking Experiments

| Category | Item / Software / Database | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Docking Software | AutoDock / AutoDock Vina [4] | Widely used, open-source package for flexible ligand docking. |

| DiffDock [2] | State-of-the-art deep learning method for high-accuracy pose prediction. | |

| Glide, GOLD [4] | Commercial docking suites known for high performance and accuracy. | |

| File Preparation & Conversion | AutoDockTools (ADT) [5] | Prepares receptor and ligand files (e.g., adds charges, defines flexibility) and generates PDBQT files. |

| Open Babel [5] | Converts chemical file formats between various standard formats. | |

| Structural Databases | Protein Data Bank (PDB) [1] | Primary repository for experimentally-determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids. |

| PDBBind [2] | Curated database of protein-ligand complexes with binding affinity data, used for training and testing. | |

| Chemical Databases | PubChem [1] | Database of chemical molecules and their activities against biological assays. |

| ZINC [1] | Free database of commercially-available compounds for virtual screening. | |

| Analysis & Visualization | PyMOL [8] | Molecular visualization system for rendering and animating 3D structures. |

| MD Simulations [3] | Used for post-docking refinement to incorporate full atomistic flexibility and dynamics. |

Molecular docking is a cornerstone computational technique in modern drug discovery, used to predict how a small molecule (ligand) binds to a target protein. The core challenge docking aims to solve is finding the optimal binding conformation and orientation of the ligand within the protein's binding site. This process is driven by sophisticated search algorithms that explore the vast conformational space available to the ligand. The accuracy of molecular docking predictions is fundamentally limited by the effectiveness of these algorithms, which must balance computational feasibility with biological realism.

Search algorithms are designed to navigate the complex energy landscape of protein-ligand interactions to identify the most stable binding pose. They can be broadly categorized into three principal families: systematic methods, stochastic methods, and simulation methods. Each approach employs distinct strategies and is implemented in various docking software packages commonly used in structural bioinformatics and computer-aided drug design. Understanding their operational principles, strengths, and limitations is essential for researchers aiming to improve docking accuracy in their experiments.

Systematic Search Methods

Core Principles and Algorithms

Systematic search methods operate on the principle of exhaustively and deterministically exploring the conformational space of a ligand. These algorithms work by systematically varying the torsional degrees of freedom of rotatable bonds in the ligand by fixed increments, thoroughly generating all possible conformations within the binding pocket [4] [9].

The main systematic approaches include:

- Conformational Search: The torsional, translational, and rotational degrees of freedom of the ligand's structural parameters are gradually changed in a stepwise manner [4].

- Incremental Construction: The ligand is fragmented into rigid components and flexible linkers. The rigid fragments are first placed in suitable sub-pockets, after which the complete ligand is reconstructed by systematically searching for optimal linker conformations [9]. This method significantly reduces computational complexity compared to a full systematic search.

Software implementations include FlexX and DOCK (incremental construction), and Glide and FRED (systematic search) [4] [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Systematic Methods

FAQ: My docking results with a systematic method show unrealistic ligand geometries. What could be wrong? This issue commonly arises from improper torsional angle sampling. If the step size for rotating bonds is too large, the algorithm may miss energetically favorable conformations. Conversely, very small step sizes exponentially increase computation time. For ligands with more than 10 rotatable bonds, systematic searches may become computationally prohibitive [9].

Solution: Reduce the rotational step size incrementally (e.g., from 15° to 10°) and monitor for improvements. For highly flexible ligands, consider switching to stochastic methods or applying conformational constraints based on known structural data.

FAQ: The docking process is taking too long for a flexible ligand. How can I speed it up? Systematic methods face the "curse of dimensionality" – computational requirements grow exponentially with each additional rotatable bond [9].

Solution:

- Pre-generate a library of low-energy ligand conformers before docking.

- Identify and fix non-essential rotatable bonds that don't affect key binding groups.

- Use a hybrid approach: perform a quick stochastic search first to identify promising regions, then apply systematic refinement.

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Systematic Docking with FlexX

Objective: To dock a flexible ligand into a known binding pocket using incremental construction.

Materials:

- Protein structure file (PDB format)

- Ligand structure file (MOL2 format)

- FlexX docking software

- High-performance computing resources

Procedure:

- System Preparation:

- Prepare the protein by removing water molecules and adding hydrogen atoms.

- Define the binding site using coordinates from a cognate crystal structure or active site prediction tools.

Ligand Preparation:

- Fragment the ligand into rigid base fragments and flexible linkers using the FlexX fragmentation algorithm.

Docking Execution:

- Dock base fragments into favorable sub-pockets using a pose-clustering algorithm.

- Reconstruct the complete ligand by incrementally adding fragments and searching torsion angles.

- Score generated poses using the FlexX scoring function.

Analysis:

- Cluster similar poses and select top-ranked conformations based on scoring function values.

- Visually inspect hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic contacts, and steric complementarity [9].

Stochastic Search Methods

Core Principles and Algorithms

Stochastic methods employ random sampling and probabilistic approaches to explore the conformational landscape, making them particularly suitable for docking flexible ligands. Unlike systematic methods, these algorithms do not guarantee finding the global minimum but often efficiently locate near-optimal solutions [4] [9].

The primary stochastic approaches include:

Genetic Algorithms (GA): Inspired by natural selection, GA encodes ligand conformational degrees of freedom as "genes" [9]. The algorithm starts with a population of random poses, then iteratively applies selection, crossover, and mutation operations based on a "fitness" score (typically the docking scoring function) [4]. Implemented in GOLD and AutoDock.

Monte Carlo Methods: These algorithms begin with a random ligand configuration and score it. Subsequent random moves are accepted if they improve the score, or accepted with a probability based on the Boltzmann distribution if they worsen it [4] [9]. This allows escaping local minima. Implemented in Glide and MCDock.

Tabu Search: This method employs memory structures that prevent revisiting previously explored regions of the conformational space, encouraging exploration of new areas [4]. Implemented in PRO_LEADS and Molegro Virtual Docker.

Troubleshooting Guide: Stochastic Methods

FAQ: My stochastic docking results are inconsistent between repeated runs. Is this normal? Yes, this is expected behavior. Since stochastic algorithms use random sampling, different random number seeds will produce varying trajectories through conformational space [9].

Solution:

- Perform multiple independent docking runs (≥10) with different random seeds.

- Cluster the results and analyze the consensus poses.

- If using genetic algorithms, increase the population size and number of generations.

FAQ: The algorithm seems trapped in a local minimum. How can I improve exploration? This is a common challenge where the algorithm fails to escape a suboptimal region of the conformational landscape.

Solution:

- For Monte Carlo methods, increase the simulation temperature to allow more uphill moves initially, then gradually decrease it (simulated annealing).

- For genetic algorithms, increase the mutation rate to enhance diversity.

- Implement multi-start approaches with diverse initial populations [9].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing Stochastic Docking with AutoDock

Objective: To dock a flexible ligand using a genetic algorithm approach.

Materials:

- AutoDock software suite

- Prepared protein and ligand structures

- Grid parameter file defining the search space

Procedure:

- Search Space Definition:

- Create a grid map around the binding site with sufficient dimensions to accommodate ligand movement.

- Set grid point spacing to 0.375 Å for adequate resolution.

Genetic Algorithm Parameters:

- Set population size to 150-300 individuals.

- Configure maximum number of generations (27,000-50,000).

- Set mutation and crossover rates to default values (0.02 and 0.8, respectively).

Docking Execution:

- Run multiple independent docking simulations (≥10) with different random seeds.

- Use the Lamarckian Genetic Algorithm which combines global search with local minimization.

Analysis:

Simulation Methods

Core Principles and Algorithms

Simulation methods, particularly Molecular Dynamics (MD), provide a physics-based approach to sampling protein-ligand conformations by simulating atomic motions over time. Unlike search-based methods, MD simulations solve Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in the system, generating a time-evolving trajectory of molecular behavior [10].

Key characteristics:

- Explicit Solvation: MD typically includes explicit water molecules, providing a more realistic solvation model than implicit solvation in docking.

- Time Resolution: Simulations use femtosecond time steps, capturing atomic vibrations and slower conformational changes.

- Force Fields: Interactions are calculated using molecular mechanical force fields that include bonded terms (bonds, angles, dihedrals) and non-bonded terms (electrostatics, van der Waals) [11] [10].

MD can be integrated with docking in two primary ways:

- Pre-docking: To generate multiple receptor conformations for ensemble docking.

- Post-docking: To refine docked poses and account for induced fit effects [9] [10].

Troubleshooting Guide: Simulation Methods

FAQ: MD simulations are extremely computationally expensive. Are there alternatives? Traditional all-atom MD with explicit solvent is computationally demanding, limiting timescales to microseconds for most systems [10].

Solution:

- Use targeted MD that focuses on relevant degrees of freedom.

- Implement accelerated MD methods that enhance conformational sampling.

- Apply coarse-grained models that reduce system complexity by grouping atoms.

- Utilize GPU-accelerated MD software like AMBER, GROMACS, or NAMD.

FAQ: How do I determine if my simulation has converged? Lack of convergence is a fundamental challenge in MD simulations.

Solution:

- Monitor root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of protein backbone and ligand until they plateau.

- Calculate statistical uncertainties using block averaging.

- Perform multiple independent simulations from different initial conditions.

- Ensure simulation time exceeds the slowest relevant motions in your system [10].

Experimental Protocol: MD Simulation for Pose Refinement

Objective: To refine a docked protein-ligand complex using molecular dynamics.

Materials:

- MD software (AMBER, GROMACS, or NAMD)

- Force field parameters (e.g., GAFF for ligands, AMBER FF14SB for proteins)

- High-performance computing cluster with GPU acceleration

Procedure:

- System Preparation:

- Solvate the docked complex in a water box with ≥10 Å padding.

- Add ions to neutralize system charge and achieve physiological salt concentration.

Energy Minimization:

- Perform steepest descent minimization to remove steric clashes.

- Execute conjugate gradient minimization to optimize geometry.

System Equilibration:

- Gradually heat system from 0 to 300 K over 100 ps in the NVT ensemble.

- Equilibrate density at 1 atm for 1 ns in the NPT ensemble.

Production Simulation:

- Run unrestrained MD for 10-100 ns depending on system size and research question.

- Save coordinates every 10-100 ps for analysis.

Trajectory Analysis:

- Calculate ligand RMSD to assess stability.

- Compute interaction frequencies (hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts).

- Perform cluster analysis to identify representative poses [10].

Comparative Analysis of Search Algorithms

Performance Metrics Table

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Search Algorithm Performance

| Algorithm Type | Ligand Flexibility Handling | Receptor Flexibility Handling | Computational Cost | Pose Prediction Accuracy (RMSD ≤ 2Å) | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Systematic | Excellent (exhaustive) | Limited (rigid or side-chain only) | High (exponential with rotatable bonds) | Moderate to High (depends on sampling density) | Small molecules (<10 rotatable bonds), congeneric series |

| Stochastic | Good (efficient sampling) | Limited (rigid or side-chain only) | Moderate (scales with iterations) | Moderate to High (varies with run parameters) | Flexible ligands, virtual screening |

| Simulation (MD) | Excellent (explicit dynamics) | Excellent (full flexibility) | Very High (nanosecond-scale) | High (after convergence) | Binding mechanism studies, pose refinement |

Software Implementation Table

Table 2: Search Algorithms in Popular Docking Software

| Software | Primary Search Algorithm | Secondary Methods | Scoring Function | Receptor Flexibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Hybrid (GA + local search) | Monte Carlo | Empirical | Side-chain flexibility |

| GOLD | Genetic Algorithm | None | Empirical | Side-chain flexibility |

| Glide | Systematic search | Monte Carlo minimization | Force field-based | Grid-based approximation |

| FlexX | Incremental construction | None | Empirical | Limited |

| DOCK | Systematic search | Anchor-and-grow | Force field-based | Limited |

Visualization of Algorithm Selection Workflow

Diagram 1: Algorithm Selection Workflow - A decision tree for selecting appropriate search algorithms based on ligand properties and research goals.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Docking

| Tool Category | Specific Software/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Docking Suites | AutoDock Vina, GOLD, Glide, FlexX | Pose prediction and scoring | Virtual screening, binding mode prediction |

| Molecular Dynamics | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD | Dynamics simulation and conformational sampling | Pose refinement, binding mechanism studies |

| Structure Preparation | Chimera, Maestro, MOE | Protein and ligand preprocessing | System setup, parameter assignment |

| Force Fields | CHARMM, AMBER, OPLS | Energy calculation and molecular mechanics | MD simulations, physics-based scoring |

| Visualization | PyMOL, VMD, UCSF Chimera | Results analysis and visualization | Interaction analysis, figure generation |

| Specialized Methods | DiffDock, DynamicBind | Deep learning-based docking | Challenging targets, cryptic pockets |

Advanced Integration and Future Directions

Hybrid Approaches

Combining multiple search algorithms often yields superior results than any single method. Common hybrid strategies include:

- Stochastic with Local Optimization: Genetic algorithms coupled with local gradient-based minimization (e.g., Lamarckian GA in AutoDock) [9].

- Multi-Stage Docking: Rapid stochastic screening followed by systematic refinement of top hits.

- MD-Relaxed Docking: Ensemble docking to multiple receptor conformations followed by short MD simulations to refine and rank poses [10].

Emerging Deep Learning Approaches

Recent advances in deep learning are transforming molecular docking:

- Diffusion Models: Methods like DiffDock apply diffusion models to molecular docking, achieving state-of-the-art accuracy by iteratively refining poses [2].

- Equivariant Networks: Models such as EquiBind use equivariant graph neural networks to predict complex structures without traditional search algorithms [2].

- Limitations: Current DL methods often struggle with physical plausibility, producing chemically unrealistic bond lengths and angles despite good RMSD scores [12]. They also face generalization challenges with novel protein binding pockets.

Addressing Key Challenges

Protein Flexibility: Traditional docking treats receptors as rigid, but incorporating flexibility remains challenging. Solutions include:

- Ensemble docking to multiple receptor conformations

- Limited side-chain flexibility in algorithms like Induced Fit Docking

- Explicit flexibility through MD simulations [2] [13]

Scoring Function Accuracy: Current scoring functions often correlate poorly with experimental binding affinities. Improvements include:

- Machine learning-based scoring functions

- Free energy perturbation methods

- Multi-objective scoring combining various terms [12]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is a scoring function in molecular docking and why is it critical? A scoring function is an algorithm that evaluates and ranks the predicted poses of a ligand bound to a protein target. It is a critical component of molecular docking programs because it differentiates between native (correct) and non-native (incorrect) binding complexes. Without accurate and efficient scoring functions, the reliability of docking tools cannot be guaranteed, directly impacting the success of virtual screening in drug discovery [14] [15]. Scoring functions aim to predict the binding affinity and identify the correct ligand binding mode and site [16].

FAQ 2: What are the main categories of scoring functions, and how do I choose? Scoring functions are broadly classified into four categories [16]:

- Physics-based: Use classical force fields to calculate binding energy from terms like van der Waals and electrostatic interactions. They are physically detailed but computationally expensive [15].

- Empirical-based: Estimate binding affinity as a weighted sum of energy terms (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) derived from known complexes. They are faster but depend on the training data [15].

- Knowledge-based: Use statistical potentials derived from the frequency of atom-pair interactions in structural databases. They offer a good balance between accuracy and speed [15].

- Machine Learning (ML)-based: Learn complex relationships between protein-ligand interaction features and binding affinity from large datasets. They show great promise but require careful validation to avoid overestimation due to data biases [17] [16].

The choice depends on your specific goal. For rapid virtual screening of large libraries, knowledge-based or empirical functions may be preferred. For a more detailed energy evaluation, physics-based functions might be suitable. For specific target classes with sufficient data, target-specific ML-based functions can offer superior performance [17] [18].

FAQ 3: My docking results show unrealistic binding poses. How can I troubleshoot this? Unrealistic poses often stem from improper ligand preparation. Key steps to address this include [19] [20]:

- Minimize the ligand: Start from a physically sensible 3D conformation. Many docking issues arise from 2D or poorly optimized structures from public libraries. Use the minimization feature in your docking software prior to the docking run.

- Manage rotatable bonds: Check and configure which bonds should be allowed to rotate during docking. Locking bonds in functional groups that should remain rigid (e.g., in aromatic rings or double bonds) ensures chemically meaningful results.

- Verify protonation states: Ensure the ligand's protonation and tautomeric states are correct for the physiological pH of interest, as this affects charge and hydrogen bonding [17] [21].

FAQ 4: What are the key challenges and future directions for scoring functions? A major challenge is the heterogeneous performance of general scoring functions across different target classes [17]. Future directions aim to overcome this through:

- Target-specific scoring functions: Developing scoring functions tailored for specific protein classes (e.g., proteases, protein-protein interactions) using machine learning, which have shown significant superiority over generic functions [17] [18].

- Improved physics-based descriptors: Incorporating more precise terms for solvation effects and entropy contributions to better represent the protein-ligand recognition process [17].

- Hybrid and Deep Learning approaches: Combining elements from different classical methods or using deep learning models to learn complex scoring functions from data, though these require rigorous benchmarking [14] [15].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Correlation Between Predicted and Experimental Binding Affinity

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect protonation/tautomeric states | Manually inspect the binding site residues and ligand. Use tools like PROPKA (for proteins) or Epik (for ligands) to estimate pKa and assign states at the relevant pH [17]. |

Reprepare the structures using a rigorous protocol with tools that optimize hydrogen bonds and assign protonation states considering the bound ligand [17]. |

| Neglect of solvation/entropy effects | Check if your scoring function explicitly includes terms for solvation/desolvation and ligand entropy. Many classical functions have limitations here [17]. | Switch to a scoring function that incorporates these terms, or use a post-processing step that estimates these contributions. Consider the use of more advanced, physics-based or ML-based functions that account for them [17]. |

| Intrinsic limitation of a general scoring function for your specific target | Check literature to see if the performance of your chosen scoring function is known to be weak for your target class. | Employ a consensus scoring approach (combining multiple scoring functions) or use a target-specific scoring function if available for your target (e.g., for proteases or protein-protein interactions) [17] [21]. |

Problem: Inability to Reproduce a Native Ligand Pose from a Co-crystal Structure

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Improperly prepared ligand structure | Visualize the prepared ligand and compare it to the co-crystalized ligand. Check for missing hydrogens, incorrect bond orders, or unrealistic geometries [19] [20]. | Ensure the ligand undergoes energy minimization before docking. Use software that provides visual feedback on rotatable bonds and allows you to lock specific bonds to preserve known geometry [19]. |

| Incorrect definition of the search space | Verify that the docking box is centered on the known binding site and that its size is large enough to accommodate the ligand's full flexibility. | Adjust the grid box coordinates and size to fully encompass the binding site. Use cavity detection algorithms like DoGSiteScorer if the site is unknown [21]. |

| Inadequate sampling of ligand conformations | Check the number of poses/output conformations generated by the docking algorithm. A low number might miss the correct conformation. | Increase the exhaustiveness of the search algorithm (or equivalent parameter in your docking software) to generate more poses for scoring [22] [23]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Developing a Target-Specific Machine Learning Scoring Function

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating a target-specific scoring function, as demonstrated in recent research [17] [18].

1. Dataset Curation

- Source: Collect high-quality protein-ligand complex structures with reliable binding affinity data (e.g., Kd, Ki, IC50) from databases like PDBbind.

- Filtering: Select complexes relevant to your target of interest. For a cGAS or kRAS-specific function, you would filter for complexes involving these proteins [18].

- Curation: Apply strict criteria: remove low-resolution structures, covalently bound ligands, and complexes with missing affinity data. Manually prepare structures, assigning correct protonation and tautomeric states [17].

2. Feature Engineering and Molecular Representation

- Physics-based descriptors: Calculate interaction energy terms (e.g., van der Waals, electrostatics, solvation, lipophilic terms, torsional entropy) to serve as features [17].

- Graph-based representation: For deep learning models (e.g., Graph Convolutional Networks), represent the protein-ligand complex as a molecular graph, where nodes are atoms and edges are bonds, to capture complex binding patterns [18].

3. Model Training and Validation

- Algorithm Selection: Train models using various algorithms:

- Training/Test Split: Randomly split the dataset (e.g., 75%/25%), ensuring a representative distribution of protein families and affinity ranges in both sets [17].

- Performance Evaluation: Validate the model on the independent test set. Assess the correlation between predicted and experimental binding affinities and the model's ability to rank active molecules above decoys in virtual screening [17] [18].

Protocol 2: Workflow for Selecting a Scoring Function in a Docking Study

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow to guide researchers in selecting an appropriate scoring function.

Research Reagent Solutions: Key Software & Databases

The following table details essential computational tools and databases for developing and applying scoring functions.

| Category | Item Name | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Software & Algorithms | DockTScore | A set of empirical scoring functions that incorporate physics-based terms (MMFF94S, solvation, entropy) and machine learning (MLR, SVM, RF) for general use or specific targets like PPIs [17]. |

| CCharPPI | A server that allows for the assessment of scoring functions for protein-protein complexes independently of the docking process, enabling direct comparison [15]. | |

| jMetalCpp | A C++ framework that provides implementations of multi-objective optimization algorithms (e.g., NSGA-II, SMPSO) that can be integrated with docking software to optimize multiple energy objectives [22]. | |

| Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN) | A deep learning architecture that uses molecular graphs to improve the extrapolation ability and accuracy of target-specific scoring functions [18]. | |

| Databases & Benchmarks | PDBbind | A comprehensive, manually curated database of protein-ligand complex structures and binding affinities, widely used for training and benchmarking scoring functions [17]. |

| DUD-E | A database of useful decoys: enhanced, containing known binders and computer-generated non-binders for various targets, used to evaluate virtual screening performance [17]. | |

| CAPRI | The Critical Assessment of PRedicted Interactions, a community-wide experiment to assess the performance of protein-protein docking and scoring methods [15]. |

Molecular docking is a cornerstone of computational drug design, enabling researchers to predict how small molecules interact with target proteins. Despite its widespread use, achieving high accuracy is hampered by several persistent challenges. The inherently dynamic nature of proteins, the critical role of water in binding, and the thermodynamic consequences of entropy present major hurdles. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs to help researchers navigate these specific issues, with the goal of improving the accuracy and reliability of molecular docking experiments.

FAQ: Addressing Common Docking Challenges

1. Why does my docking simulation fail to predict the correct binding pose, even when I use a high-resolution protein structure?

This failure is often due to receptor flexibility. Traditional rigid docking assumes a static "lock-and-key" model, but proteins are dynamic. State-of-the-art docking algorithms predict an incorrect binding pose for about 50 to 70% of all ligands when only a single fixed receptor conformation is used [24]. Even when the correct pose is found, the binding score can be meaningless without accounting for protein movement [24].

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Use Multiple Receptor Conformations (MRC): Dock your ligands against an ensemble of protein structures instead of just one. This ensemble can be built from:

- Consider Side-Chain Flexibility: For many systems, conformational variability is well-described by the movement of several side-chains [24]. Tools like SLIDE attempt to resolve steric clashes with a minimal number of side-chain rotations [24].

- Explore Advanced Algorithms: For larger movements, consider docking algorithms like FlexE, which can combinatorially join dissimilar parts from an input set of conformations to generate new receptor structures during the search [24].

2. How do solvation and entropy effects influence binding affinity predictions, and why are they often overlooked?

Solvation and entropy are critical for determining the binding free energy but are challenging to model explicitly [25]. Ligand binding is a desolvation process, where water molecules are displaced from the binding pocket. This process involves a delicate balance of energy: breaking favorable ligand-water and protein-water interactions must be compensated by the formation of new protein-ligand interactions [25] [26]. Entropic effects include the loss of conformational freedom of the ligand upon binding and changes in the solvent's degrees of freedom.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Include Explicit Solvation Terms: Use scoring functions that incorporate solvation. For example, the knowledge-based scoring function ITScore/SE includes a solvent-accessible surface area (SASA)-based energy term to account for hydrophobic and hydrophilic effects [25].

- Use Methods that Model Water explicitly: Computational methods like WATsite can be used to calculate high-resolution solvation maps and thermodynamic profiles of water molecules in binding sites, providing a quantitative estimate of their contribution to binding free energy [26].

3. What is the difference between re-docking, cross-docking, and apo-docking, and why does my method perform well in one but poorly in another?

These terms describe different docking tasks that test a method's robustness and its ability to handle protein flexibility [2].

- Re-docking: Docking a ligand back into the bound (holo) conformation of the receptor from which it was extracted. This is the easiest task, and most methods perform well here [2].

- Cross-docking: Docking a ligand to a receptor conformation taken from a different ligand complex. This tests a model's ability to handle conformational changes induced by different ligands [2].

- Apo-docking: Docking to an unbound (apo) receptor structure. This is a highly realistic and challenging setting, as it requires the model to infer the "induced fit" where the protein adapts to the ligand [2].

Performance drops in cross-docking and apo-docking because they require the method to account for protein flexibility, which many traditional and deep learning methods do not handle well [2].

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Know Your Docking Task: Always validate your chosen method on a task that matches your real-world scenario (e.g., use apo- or cross-docking benchmarks if your target's structure is unbound).

- Choose a Flexible Docking Method: For cross-docking and apo-docking, prioritize methods designed for flexibility. Recent deep learning models like FlexPose aim to enable end-to-end flexible modeling of protein-ligand complexes irrespective of the input protein conformation [2].

Quantitative Data: Performance Comparison of Docking Methods

The following table summarizes the performance of various docking approaches across different benchmarks, highlighting the trade-offs between pose accuracy and physical validity. A "successful" docking case is typically defined as a predicted pose with a Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) ≤ 2.0 Å from the experimental structure and that is "PB-valid" (passes checks for physical plausibility like proper bond lengths and steric clashes) [12].

Table 1: Docking Performance Across Different Method Types and Benchmarks (Success Rates %) [12]

| Method Type | Representative Method | Astex Diverse Set (Known Complexes) | PoseBusters Benchmark (Unseen Complexes) | DockGen (Novel Pockets) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD ≤2Å | PB-Valid | Combined | RMSD ≤2Å | PB-Valid | Combined | RMSD ≤2Å | PB-Valid | Combined | ||

| Traditional | Glide SP | 81.18% | 97.65% | 79.41% | 66.82% | 97.20% | 65.42% | 50.96% | 94.44% | 48.15% |

| Hybrid AI | Interformer | 82.35% | 89.41% | 75.29% | 64.49% | 82.24% | 55.14% | 45.75% | 76.47% | 37.25% |

| Generative Diffusion | SurfDock | 91.76% | 63.53% | 61.18% | 77.34% | 45.79% | 39.25% | 75.66% | 40.21% | 33.33% |

| Regression-Based | KarmaDock | 52.94% | 44.71% | 28.24% | 38.32% | 32.71% | 17.76% | 20.75% | 28.76% | 10.46% |

Key Insight: Traditional and hybrid methods consistently yield a higher proportion of physically valid structures, which is critical for reliable drug discovery. While some deep learning methods (e.g., SurfDock) show superior pose accuracy (RMSD), they often lag in physical plausibility, which can limit their practical utility [12].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ensemble Docking to Account for Receptor Flexibility

This protocol uses multiple receptor conformations (MRC) to improve docking accuracy by accounting for protein flexibility [24].

- Collect Receptor Conformations: Gather an ensemble of structures for your target protein. Sources include:

- The Protein Data Bank (PDB): Look for multiple crystal structures, especially with different ligands bound.

- NMR ensembles.

- Computational generation using molecular dynamics (MD) simulations or normal mode analysis.

- Prepare Structures: Use a molecular visualization/preparation software (e.g., Chimera, Maestro) to prepare all structures. This involves adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and removing crystallographic water molecules (unless they are known to be important for binding).

- Define the Binding Site: Identify the centroid of the binding site from a known holo structure and use the same coordinates for all conformations in the ensemble.

- Run Docking Simulations: Dock each ligand from your library against every conformation in the receptor ensemble. This can be done sequentially or using software with built-in ensemble docking capabilities.

- Analyze Results: Consolidate the results from all docking runs. Common strategies for selecting the final pose include:

- Choosing the pose with the most favorable (lowest) docking score across the entire ensemble.

- Selecting the most frequent pose cluster across all ensembles.

Protocol 2: Incorporating Solvation and Entropy Effects Iteratively

This protocol is based on the methodology developed for the ITScore/SE knowledge-based scoring function, which explicitly includes solvation and configurational entropy [25].

- Initialization: Begin with initial guesses for the pairwise potentials ( u{ij}^{(0)}(r) ) and atomic solvation parameters ( \sigmai^{(0)} ). These can be set using a combination of potential of mean force and Lennard-Jones potentials, with solvation parameters starting at zero [25].

- Generate Decoy Structures: For each protein-ligand complex in the training set, generate a large ensemble (L) of ligand orientations and conformations (decoys), including the native crystal structure [25].

- Calculate Distribution Functions: For the current iteration (n), compute the predicted pair distribution functions ( g{ij}^{(n)}(r) ) and the SASA change term ( f{\Delta SAi}^{(n)} ) using a Boltzmann-weighted average over all decoy structures [25]. ( f{\Delta SAi}^{(n)} = \frac{\sum{m}^{M} \sum{l}^{L} \Delta SA{iml} e^{-\beta U{ml}^{(n)}}}{\sum{m}^{M} \sum{l}^{L} \sum{i} \Delta SA{iml} e^{-\beta U{ml}^{(n)}}} ) Where M is the number of complexes, L is the number of decoys, and ( U_{ml}^{(n)} ) is the binding energy score from Eq. (2) in the original text [25].

- Iterate Potentials: Update the potentials by comparing the predicted distributions with the experimentally observed ones [25]. ( u{ij}^{(n+1)}(r) = u{ij}^{(n)}(r) + \lambda kB T \left[ g{ij}^{(n)}(r) - g{ij}^{obs}(r) \right] ) ( \sigmai^{(n+1)} = \sigmai^{(n)} + \lambda kB T \left( f{\Delta SAi}^{(n)} - f{\Delta SAi}^{obs} \right) )

- Check for Convergence: Repeat steps 3 and 4 until the convergence criterion is met (e.g., the change in potentials between iterations falls below a defined threshold) [25].

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Iterative Scoring Function Development

This diagram illustrates the iterative process of developing a scoring function that incorporates solvation and entropy effects [25].

Diagram 2: Flexible Receptor Docking Strategies

This workflow compares two primary computational strategies for handling receptor flexibility in docking.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Computational Tools for Advanced Docking

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in Addressing Docking Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| AutoDock/Vina [4] | Docking Software | Widely used traditional docking programs that support flexible ligand docking. AutoDock Vina is noted for its speed and good performance [4]. |

| Glide [12] [4] | Docking Software | A traditional physics-based docking tool known for high physical validity and success rates in virtual screening [12]. |

| FlexE [24] | Docking Software | An extension of FlexX that uses multiple receptor structures and can combinatorially join distinct parts to generate new conformations during docking [24]. |

| WATsite [26] | Solvation Modeling | A computational method that uses MD simulations to model solvation effects, providing high-resolution solvation maps and thermodynamic profiles of water in binding sites [26]. |

| DiffDock [2] | Deep Learning Docking | A generative diffusion model that has shown state-of-the-art pose prediction accuracy, though it may produce physically implausible structures [2] [12]. |

| FlexPose [2] | Deep Learning Docking | A deep learning model designed for end-to-end flexible modeling of protein-ligand complexes, aiming to handle both apo and holo input conformations [2]. |

| PoseBusters [12] | Validation Tool | A toolkit to systematically evaluate docking predictions against chemical and geometric consistency criteria, ensuring physical plausibility [12]. |

The Trade-Off Between Computational Speed and Predictive Accuracy

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental trade-off in molecular docking? The core trade-off lies between the computational cost of a docking simulation and the accuracy of its predictions. Higher accuracy typically requires more complex scoring functions and extensive sampling of ligand and protein conformations, which demands greater computational resources and time. Simplifying the model—for example, by treating the protein as rigid—speeds up the calculation but can reduce reliability, especially for targets that undergo significant conformational change upon ligand binding [2] [27].

FAQ 2: How do traditional and deep learning docking methods compare in this trade-off? Traditional and deep learning (DL) methods represent different approaches to managing this trade-off:

- Traditional methods (e.g., AutoDock Vina) use search-and-score algorithms and physical/empirical scoring functions. They are computationally demanding for exhaustive sampling but are generally faster than early DL methods for single complexes [28] [2].

- Deep learning methods often have a high initial computational cost during training. However, once trained, they can predict binding poses orders of magnitude faster than traditional methods, making them ideal for high-throughput tasks. The challenge for DL is ensuring the physical plausibility of predictions and generalizing to novel protein targets beyond their training data [2] [6].

FAQ 3: What is the impact of protein flexibility on docking speed and accuracy? Accounting for protein flexibility is crucial for predictive accuracy, as proteins are dynamic molecules that can change shape upon ligand binding (induced fit). However, incorporating flexibility exponentially increases the number of degrees of freedom and the computational cost of the docking search [2] [27]. Ignoring protein flexibility (treating the receptor as rigid) speeds up the process but can lead to major failures in accuracy, particularly in real-world scenarios like cross-docking or using computationally predicted protein structures [2].

FAQ 4: How can I improve docking speed for virtual screening without sacrificing too much accuracy? For large-scale virtual screening, consider these strategies:

- Use Knowledge-Distilled Models: Tools like GNINA 1.3 offer smaller, faster "student" models that retain much of the accuracy of larger, slower "teacher" ensembles [29].

- Leverage Deep Learning: DL-based docking methods like DiffDock offer very fast inference times after training, making them suitable for screening ultra-large libraries [2] [29].

- Employ Hybrid Approaches: Use fast DL methods for initial, coarse-grained screening of large libraries, then apply more accurate but slower traditional or hybrid methods to a shortlist of top candidates [6].

FAQ 5: Why does my docking tool produce physically implausible ligand poses? This is a common challenge, particularly with some deep learning models. It can occur because:

- The model's scoring function or training data does not adequately penalize unrealistic steric clashes, improper bond lengths, or incorrect bond angles [2] [6].

- The sampling algorithm may not sufficiently explore the conformational space or get trapped in unrealistic local minima. To mitigate this, use docking software known for producing physically valid structures and always visually inspect top-ranked poses for plausibility [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Pose Prediction Accuracy

Symptoms: The predicted ligand binding mode (pose) has a high Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) from the experimentally determined structure. Low enrichment of known active compounds in virtual screening.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate conformational sampling | Check docking logs for number of poses generated. Compare results with different sampling algorithms (e.g., MC vs. GA). | Increase the number of runs/exhaustiveness in the docking parameters. Use a more robust sampling algorithm like the Iterated Local Search in AutoDock Vina [28]. |

| Insufficient protein flexibility | Perform re-docking (ligand into its native structure); if accurate, but cross-docking fails, flexibility is likely the issue. | If possible, use an ensemble of protein structures. For side-chain flexibility, consider tools with flexible residue handling. For major flexibility, use DL methods like FlexPose designed for flexible docking [2]. |

| Limitations of the scoring function | Check if the scoring function performs poorly on known benchmarks for your target class. | Switch to a different scoring function. Use consensus scoring from multiple functions. Employ a deep learning-based scoring function like CNNs in GNINA or other graph neural networks [29] [30]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Pose Prediction Accuracy

- Prepare Structures: Obtain a dataset of protein-ligand complexes with known experimental structures (e.g., from PDBbind [30]).

- Prepare Ligands and Proteins: Separate the ligand from the protein structure. Prepare the files for docking (adding hydrogens, assigning charges).

- Run Docking: Dock each ligand back into its corresponding protein binding site using your chosen protocol.

- Calculate RMSD: Superimpose the protein from the experimental structure with the docking output protein. Calculate the RMSD between the heavy atoms of the experimental ligand pose and the docked ligand pose.

- Analyze Results: A pose with RMSD < 2.0 Å is typically considered successful. Calculate the success rate across your test set [29].

Problem 2: Inaccurate Binding Affinity Prediction

Symptoms: The predicted binding energy (ΔG) does not correlate with experimental binding constants (Ki, IC50). Inability to correctly rank a series of similar ligands by affinity.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Systematic bias in the scoring function | Test the scoring function on a benchmark set like CASF [30]. Check for trends of over/under-estimating affinity for certain chemical groups. | Use a machine-learning scoring function trained on diverse data (e.g., AEV-PLIG [30]). For lead optimization, consider more rigorous methods like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) for critical compounds [30]. |

| Lack of generalizability (Overfitting) | The model works on training/benchmark data but fails on your novel target. | Use models trained with data augmentation (e.g., with docked poses [30]). Ensure your target is not too distant from the training data distribution. |

| Ignoring key physical interactions | Visually inspect the pose to see if crucial interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts) are formed and scored correctly. | Use a scoring function that incorporates important interaction terms. Consider solvation effects and entropy penalties, which are sometimes handled crudely in fast scoring functions [28]. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating Affinity Prediction (Scoring) Power

- Obtain a Benchmark Set: Use a curated set like the PDBbind core set or CASF benchmark, which contains diverse protein-ligand complexes with reliable experimental affinity data [30].

- Generate Binding Poses: For each complex, use the experimentally determined ligand pose (to isolate scoring function performance from sampling errors).

- Calculate Predicted Affinity: Score each complex using your docking program's scoring function to obtain a predicted binding score.

- Perform Correlation Analysis: Calculate the correlation (e.g., Pearson Correlation Coefficient - PCC) between the predicted scores and the experimental binding affinities. A higher PCC indicates better scoring power [30].

Problem 3: Prohibitively Long Docking Times

Symptoms: Docking a single compound takes hours or days. Virtual screening of a library of millions is computationally infeasible.

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Overly large search space | Check the dimensions of the defined binding box. Too many rotatable bonds in the ligand. | Define a tighter binding box around the known active site. Use a faster, less exhaustive search algorithm for initial screening. |

| Computationally expensive scoring function | Profile the docking run to see if scoring is the bottleneck. Compare runtime with different scoring functions (e.g., Vina vs. CNN scoring). | For high-throughput screening, use a faster scoring function. Employ knowledge-distilled models (e.g., in GNINA 1.3) for a good speed/accuracy balance [29]. |

| Lack of hardware optimization | Check if the software is using GPU acceleration. | Use docking software that supports GPU computing (e.g., GNINA for CNN scoring [29]). Leverage multi-threading capabilities (e.g., AutoDock Vina's CPU multithreading [28]) on multi-core machines. |

The tables below consolidate key performance metrics from recent studies to aid in tool selection and expectation management.

| Docking Paradigm | Pose Accuracy | Virtual Screening Efficacy | Physical Plausibility | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Generative Diffusion (e.g., DiffDock) | High | Good | Medium-High | High-accuracy pose prediction for specific complexes. |

| Hybrid Methods | Medium-High | High | High | Balanced performance for lead optimization. |

| Regression-based DL | Variable | Medium | Low (High steric tolerance) | Fast screening where visual validation is possible. |

| Traditional (Vina, GNINA) | Medium | Medium-High | High | General-purpose docking; reliable baseline. |

Table 2: Speed vs. Accuracy in Selected Tools

| Tool / Method | Key Feature | Computational Speed | Key Accuracy Metric | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Iterated Local Search & BFGS optimization | ~2 orders faster than AutoDock 4; benefits from multithreading. | Significantly improved pose prediction on training set. | [28] |

| GNINA (CNN Scoring) | Deep learning on 3D density grids | Slower than Vina, but accelerated on GPU. | Outperforms Vina; similar to commercial tools. | [29] |

| GNINA (Distilled Model) | Knowledge distillation from ensemble | Faster than full CNN ensemble (72s vs 458s on CPU). | Retains most of the ensemble's performance. | [29] |

| DiffDock | Diffusion model for pose generation | High inference speed post-training; fraction of traditional cost. | State-of-the-art pose accuracy on PDBBind test set. | [2] |

| AEV-PLIG (Scoring) | Attention-based graph neural network | ~400,000x faster than FEP calculations. | Competitive PCC (0.59) on FEP benchmark sets. | [30] |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Docking Strategy Selection

Scoring Function Trade-Offs

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Datasets for Docking Research

| Item Name | Type | Function/Purpose | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| AutoDock Vina | Docking Software | Widely-used open-source tool offering a good balance of speed and accuracy using a search-and-score approach. | [28] |

| GNINA | Docking Software | Open-source framework using CNN scoring functions on 3D grids; supports flexible docking and covalent docking. | [29] |

| DiffDock | Docking Software | Deep learning method using diffusion models for high-accuracy pose prediction with fast inference times. | [2] |

| PDBbind | Curated Dataset | A comprehensive, curated database of protein-ligand complexes with experimental binding affinities for training and benchmarking. | [28] [30] |

| CrossDocked2020 | Curated Dataset | A large, aligned dataset of protein-ligand structures used for training and evaluating machine learning-based docking models. | [29] |

| CASF Benchmark | Benchmarking Set | The "Critical Assessment of Scoring Functions" benchmark used to rigorously evaluate scoring power, docking power, etc. | [30] |

| AEV-PLIG | Scoring Function | An attention-based graph neural network scoring function for fast and accurate binding affinity prediction. | [30] |

Advanced Techniques and Best Practices for Enhanced Docking Protocols

Leveraging AI and Machine Learning for Improved Scoring and Pose Prediction

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My AI-predicted docking pose has a good RMSD value but fails to reproduce key protein-ligand interactions like hydrogen bonds. What could be wrong?

This is a common limitation identified in several recent benchmarking studies. Many deep learning docking methods, particularly diffusion models like DiffDock-L, are optimized to produce poses with low Root-Mean-Square Deviation (RMSD) but may overlook specific chemical interactions critical for biological activity [31] [12]. The scoring functions may not adequately prioritize these interactions. For critical drug design projects, it is recommended to validate AI-generated poses by checking interaction recovery using tools like PoseBusters and consider using classical docking programs (e.g., GOLD) or hybrid methods for final verification, as they often outperform pure AI methods in recovering specific interactions like hydrogen bonds [31] [12].

Q2: When docking into a novel protein pocket not in my training data, the AI model performance drops significantly. How can I improve accuracy?

This is a generalization challenge common to many deep learning docking methods [12] [32]. Models trained on specific datasets (e.g., PDBBind) may not transfer well to novel protein sequences or binding pocket geometries [2] [33]. To address this:

- Use Ensemble Docking: If available, dock against an ensemble of multiple receptor conformations, which can be generated using molecular dynamics simulations prior to docking [9].

- Leverage Flexible DL Models: Consider emerging models specifically designed for flexibility and cross-docking, such as FlexPose or DynamicBind, which better handle conformational changes between apo (unbound) and holo (bound) protein states [2].

- Hybrid Approach: Use a AI method for initial, rapid pose generation and a physics-based method (e.g., Glide SP, AutoDock Vina) for pose refinement and scoring, as traditional methods often show more robust generalization to novel pockets [12] [32].

Q3: The ligand poses generated by my deep learning model are not physically plausible, with odd bond lengths or atomic clashes. How can I fix this?

Many deep learning models, especially regression-based architectures, struggle with producing physically valid structures despite good RMSD [12] [32]. This is because their loss functions may not explicitly enforce physical constraints.

- Post-Prediction Checks: Always run your top-ranked predicted poses through a validation tool like PoseBusters, which checks for geometric and chemical consistency (e.g., bond lengths, angles, steric clashes, and proper stereochemistry) [12] [32].

- Model Selection: Prefer generative diffusion models (e.g., SurfDock) or hybrid methods (e.g., Interformer) over regression-based models, as they generally produce more physically plausible outputs [12].

- Energy Minimization: As a post-processing step, perform a brief energy minimization of the predicted protein-ligand complex using a molecular mechanics force field to relax any unrealistic atomic overlaps or bond geometries [9].

Q4: For a large-scale virtual screening campaign, should I use a traditional physics-based method or a new deep learning approach?

The choice depends on your priorities of speed versus accuracy and generalization [12] [33].

- Choose Deep Learning for Speed and Blind Docking: For rapidly screening ultra-large libraries (billions of compounds) or when the binding site is unknown (blind docking), deep learning methods like DiffDock are significantly faster and well-suited [2] [33].

- Choose Traditional/Hybrid for Accuracy and Known Pockets: For screening against a known binding site, especially when accuracy and physical realism of the poses are paramount, traditional physics-based methods (e.g., Glide SP, AutoDock Vina) or hybrid methods (e.g., Interformer) currently demonstrate superior performance and reliability in virtual screening benchmarks [12] [33]. They consistently achieve better enrichment of true active compounds [33].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Pose Accuracy in Cross-Docking or Apo-Docking Scenarios

Problem: Your model performs well in re-docking (ligand docked back into its original protein structure) but fails when docking to an alternative protein conformation (cross-docking) or an unbound (apo) structure [2].

Diagnosis: This typically indicates an inability to handle protein flexibility and induced fit effects, where the binding pocket changes shape upon ligand binding [2]. Most DL models are trained on holo (ligand-bound) structures and treat the protein as largely rigid.

Solutions:

- Utilize Flexible Docking Models: Employ next-generation DL models that incorporate protein flexibility. For example, FlexPose enables end-to-end flexible modeling of the complex, while DynamicBind uses equivariant geometric diffusion networks to model backbone and sidechain movements [2].

- Incorporate an Ensemble of Structures: If a fully flexible model is not available, perform docking against an ensemble of protein conformations. This ensemble can be sourced from:

- Multiple experimental structures (e.g., from the PDB).

- Computational simulations like Molecular Dynamics (MD) to generate diverse conformations [9].

- Conformational sampling from normal mode analysis.

- Apply a Hybrid Refinement: Generate initial poses with a fast DL method, then refine the top poses using a method that allows for side-chain or limited backbone flexibility, such as the RosettaVS VSH (Virtual Screening High-precision) mode [33].

Issue 2: Ineffective Virtual Screening and Poor Hit Enrichment

Problem: The docking method fails to prioritize true active compounds over inactive ones in a virtual screen, leading to a low hit rate upon experimental validation.

Diagnosis: The scoring function may not accurately distinguish binders from non-binders, often due to a lack of generalizability or an over-reliance on pose-based metrics like RMSD instead of interaction energy [12] [33].

Solutions:

- Benchmark Your Scoring Function: Before running a large screen, test the scoring function's "screening power" on a known benchmark like the Directory of Useful Decoys (DUD). Evaluate metrics like Enrichment Factor (EF) and Area Under the Curve (AUC) to ensure it performs well for your target class [33] [34].

- Use a Hybrid or Physics-Based Scoring Function: Integrate AI with physics-based methods. For instance, the RosettaGenFF-VS force field combines enthalpy calculations with entropy estimates, showing top-tier performance in enrichment factors [33]. Alternatively, use a hybrid method like Interformer that uses AI to rescore poses generated by a traditional conformational search [12].

- Leverage Active Learning Platforms: For screening billion-compound libraries, use platforms like OpenVS that employ active learning. These platforms train a target-specific neural network on-the-fly to intelligently select promising compounds for more expensive, high-fidelity docking calculations, greatly improving efficiency and focus [33].

Issue 3: Physically Implausible Ligand Conformations

Problem: The predicted ligand poses contain incorrect bond lengths, angles, stereochemistry, or severe steric clashes with the protein [12] [32].

Diagnosis: The deep learning model's architecture or training data may not adequately incorporate physical constraints and molecular mechanics principles.

Solutions:

- Integrate Physical Checks into the Workflow: Incorporate a validation step using the PoseBusters toolkit immediately after pose prediction to filter out invalid structures [12].

- Select Physically-Robust Models: Refer to benchmarking studies and choose methods known for high physical validity. Recent evaluations show that traditional methods (Glide SP, AutoDock Vina) and hybrid methods (Interformer) consistently achieve high PB-valid rates (often >90% and >70%, respectively) [12].

- Refine with Molecular Mechanics: Subject the top AI-generated poses to a brief, constrained molecular mechanics minimization within the protein's binding site. This relaxes the structure into a more physically realistic conformation without significantly altering the overall binding mode [9].

Performance Data for Method Selection

The table below summarizes a multidimensional evaluation of docking methods to guide your selection. It is based on a 2025 systematic benchmark assessing performance across pose accuracy, physical validity, and success on novel pockets [12] [32].

Table 1: Multidimensional Performance Comparison of Docking Method Types

| Method Type | Example Methods | Pose Accuracy (RMSD ≤ 2Å) | Physical Validity (PB-Valid Rate) | Generalization to Novel Pockets | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional | Glide SP, AutoDock Vina | Moderate to High | Very High (≥94%) [12] | Robust | High-accuracy docking to known sites; ensuring physical realism [12] [33] |

| Generative Diffusion | SurfDock, DiffDock | Very High (≥75%) [12] | Moderate to Low | Moderate | Fast, high-accuracy pose prediction when binding site is known or for blind docking [2] [12] |

| Regression-Based | KarmaDock, QuickBind | Variable, often Lower | Low (High steric tolerance) [12] | Poor | Rapid preliminary screening; less recommended for final predictions |

| Hybrid | Interformer | High | High (≈70%) [12] | Good | Balanced approach for virtual screening; combining accuracy and physical plausibility [12] |

Table 2: Key Metrics for Virtual Screening Performance

| Method | Screening Power (Top 1% Enrichment Factor on CASF2016) | Key Advantage for Screening |

|---|---|---|

| RosettaGenFF-VS | 16.7 [33] | Combines improved enthalpy calculations with an entropy model |

| Other Physics-Based SFs | ≤11.9 [33] | Proven reliability and generalizability |

| Deep Learning SFs | Variable, can be high but generalizability concerns exist [33] | Speed and ability to learn from large data |

Table 3: Essential Software and Data Resources for AI-Enhanced Docking

| Resource Name | Type | Function and Application | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| PoseBusters | Validation Tool | Checks predicted protein-ligand complexes for physical and chemical plausibility (bonds, angles, clashes, etc.) [12]. | Open Source |

| PDBBind | Dataset | Curated database of protein-ligand complex structures and binding data, used for training and benchmarking [2]. | Commercial / Academic |

| DUD/DUD-E | Dataset | Directory of Useful Decoys; benchmark dataset for evaluating virtual screening enrichment [33] [34]. | Open Source |

| CASF Benchmark | Dataset | Comparative Assessment of Scoring Functions; standard benchmark for scoring function evaluation [33]. | Open Source |

| OpenVS Platform | Screening Platform | An open-source, AI-accelerated platform that uses active learning for efficient ultra-large library screening [33]. | Open Source |

| RosettaVS | Docking Software | A physics-based docking protocol with high-precision modes that allow for receptor flexibility [33]. | Commercial / Academic |

| AlphaFold DB | Database | Repository of highly accurate predicted protein structures from AlphaFold, useful when experimental structures are unavailable [9]. | Open Source |

Experimental Protocol: Benchmarking Docking Pose Quality and Interaction Recovery

This protocol provides a standardized method to evaluate the performance of a docking method, focusing not just on pose placement (RMSD) but also on physical quality and biological relevance, as emphasized in recent literature [31] [12].

Objective: To comprehensively assess a docking method's accuracy by measuring ligand pose RMSD, physical plausibility, and recovery of key protein-ligand interactions.

Materials:

- A set of known protein-ligand complex structures (e.g., from the PDBBind or Astex diverse set [12]).

- The docking software to be evaluated.

- Validation software: PoseBusters [12].

- A molecular visualization program (e.g., PyMOL, ChimeraX).

Procedure:

- Dataset Curation:

- Separate your dataset of known complexes into a training set (if retraining a model is needed) and a held-out test set. Ensure no significant similarity between training and test proteins/ligands to properly test generalization [12] [33].

- Prepare the input files: the protein structure without the ligand (apo) and the ligand's 3D structure in a separate file.

Pose Prediction:

- For each complex in the test set, run the docking software to generate a set of predicted ligand poses (e.g., top 10 ranked poses).

Pose Accuracy Calculation (RMSD):

- For each predicted pose, calculate the RMSD between the predicted ligand heavy atoms and the experimentally determined (native) ligand structure after optimal superposition of the protein receptor.

- A pose is typically considered "successful" if its RMSD is ≤ 2.0 Å [12].

Physical Plausibility Check:

- Run the top-ranked predicted pose through PoseBusters.

- Record whether the pose is "PB-Valid," meaning it passes all checks for bond lengths, angles, planarity, stereochemistry, and absence of steric clashes [12].

Interaction Recovery Analysis:

- Using a molecular visualization tool or an automated script, identify key non-covalent interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, pi-stacking) in the native experimental structure.

- In the top-ranked predicted pose, check for the presence of these same key interactions.

- Calculate the percentage recovery of these critical interactions.

Interpretation: A robust docking method should achieve a high success rate in both RMSD ≤ 2.0 Å and PB-Valid metrics. Be cautious of methods that score high on RMSD but low on physical validity or interaction recovery, as this indicates a risk of predicting unrealistic poses that are not useful for drug design [31] [12].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a recommended troubleshooting and refinement workflow for AI-driven molecular docking, integrating the FAQs and guides above.

The following diagram helps select an appropriate docking strategy based on your research goals and the target protein.

Incorporating Receptor Flexibility with Induced Fit Docking and Side-Chain Sampling

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)